Abstract

Large household water storage containers are among the most productive habitats for Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762), the primary mosquito vector for dengue and other arboviral pathogens. Increasing concerns for insecticide resistance and larvicide safety are limiting the successful treatment of large household water storage containers, which are among the most productive habitats for Aedes juveniles. The recent development of species-specific RNAi-based yeast larvicides could help overcome these problems, particularly if shelf stable ready-to-use formulations with significant residual activity in water can be developed. Here we examine the hypothesis that development of a shelf-stable controlled-release RNAi yeast formulation can facilitate lasting control of A. aegypti juveniles in large water storage containers. In this study, a dried inactivated yeast was incorporated into a biodegradable matrix containing a mixture of polylactic acid, a preservative, and UV protectants. The formulation was prepared using food-grade level components to prevent toxicity to humans or other organisms. Both floating and sinking versions of the tablets were prepared for treatment of various sized water containers, including household water storage tank-sized containers. The tablets passed accelerated storage tests of shelf life stability and demonstrated up to six months residual activity in water. The yeast performed well in both small and large containers, including water barrels containing 20-1000 larvae each, and in outdoor barrel trials. Future studies will include the evaluation of the yeast larvicide in larger operational field trials that will further assess the potential for incorporating this new technology into integrated mosquito control programs worldwide.

Subject terms: Genetic techniques, Genetics, Infectious diseases

Introduction

Aedes aegypti is the principal mosquito vector of viruses that cause dengue, Zika, yellow fever, and chikungunya. Dengue, the most widespread and significant arboviral disease in the world, is a threat to roughly four billion people worldwide and has an annual incidence of approximately 400 million cases resulting in ~ 40,000 deaths from severe dengue annually across the globe1. The Pan-American Health Organization warned that 2024 may be the worst year for dengue ever recorded, with > 3.5 million cases confirmed by Latin American governments in the first quarter of 20242. Although a dengue vaccine is now available in some parts of the world1, the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that it be used only in children ages 9–16 living in dengue endemic countries who have had a confirmed case of dengue, and mosquito control is therefore vital for disease control. Yellow fever is endemic in 33 African countries and 11 South American countries, and several recent outbreaks have occurred despite the availability of a highly effective vaccine1. Furthermore, in 2015-2016, large outbreaks of Zika, which has been linked to severe birth defects and neurological disorders, occurred in many countries in the Americas, and chikungunya outbreaks have occurred in more than 100 countries in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Europe1. No human vaccines for Zika or chikungunya are yet available, underscoring the importance of Aedes mosquito control. Unfortunately, the emergence of insecticide resistance, concerns for the negative impacts of pesticides on the environment, and a lack of support for mosquito control programs compromise mosquito management strategies and efforts to control arboviral illnesses1.

Aedes mosquitoes lay eggs in water-holding containers, including a variety of both natural and artificial containers that collect rainwater or that are filled with water by humans. Larvae hatch from the eggs and remain in the water-filled containers through the end of the pupal stage. During this aquatic phase, the immature mosquitoes are concentrated within defined water boundaries and therefore susceptible to control efforts. Larviciding is the application of microbial or chemical agents to kill mosquito larvae, before they are reproducing adults that vector human disease pathogens, and is a key component of integrated Aedes control strategies1. Temephos attached to silica (sand) granules, the active ingredient in Abate®, had historically been used to treat water containers that are too large to empty3. Studies in Trinidad demonstrated that large water storage containers are the most productive Aedes larval habitats4. After decades of heavy temephos usage, temephos resistant A. aegypti strains were identified in many countries5,6. Moreover, in a recent re-registration eligibility decision, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) called for labeling changes to address risks that temephos poses to human and environmental health and prohibited drinking water source treatment7. This compromised larval control in large water storage containers in the U.S. and many other countries, which stopped using the insecticide. Due to the loss of this pesticide option, as well as the frequent development of pesticide resistance and growing concerns regarding the non-target effects of pesticides in the environment, the development of new environmentally-friendly larvicides that have minimal impact on the environment is therefore essential and urgent8.

RNA interference (RNAi) has been used extensively for functional genetic studies in a wide variety of organisms, including insects9,10. The RNAi pathway is initiated by Dicer, an enzyme that cleaves long double stranded RNA (dsRNA) into short 20-25 nucleotide-long small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that function as sequence-specific interfering RNA, which may offer a species-specific means of targeting insect pests. siRNAs silence genes that are complementary in sequence by promoting transcript turnover, cleavage, and disruption of translation10,11, and numerous studies have demonstrated that target gene silencing through RNAi can promote insect death9,10. For example, Baum et al.12 engineered transgenic corn plants expressing dsRNA targeting the western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte. dsRNA insecticidal corn targeting this species was registered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency7. An RNAi insecticide targeting the Colorado potato beetle was also registered by the EPA in December 20237. These and other findings suggest that RNAi can be exploited to control insect agricultural pests. This study aimed to apply RNAi technology for the control of insect vectors of human disease pathogens. Here, we evaluate the impact of deploying yeast RNAi larvicides, a new species-specific eco-friendly class of insecticides, for the treatment of large water storage containers.

Our recent studies have demonstrated that short hairpin RNA (shRNA) designed to specifically target mosquito larval genes can be expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast), a model organism that is genetically tractable, inexpensive to culture, and which can facilitate shRNA production during yeast propagation13,14. The yeast, which can be heat killed prior to deployment, is highly attractive to mosquito larvae15 and readily consumed, even when placed in containers bearing other food sources. Yeast RNAi systems promote high levels of gene silencing during the larval stages and, when used to target larval genes that are required for survival, can generate high levels of larval mortality upon consumption14. The yeast has demonstrated high levels of efficacy in semi-field trials14,16. Here, we describe the formulation of dried heat-killed yeast tablets and briquettes that were developed as long-lasting controlled-release larvicides for the treatment of large water storage containers.

Results and discussion

Evaluation of yeast prepared through spray drying and lyophilization

Previous studies described development of the syt.42717 and sema.46018 yeast strains, which express short hairpin RNA (shRNAs) targeting conserved sites in the mosquito synaptotagmin (syt) and semaphorin (sema) genes, respectively. These RNAi yeast insecticides effectively kill Aedes spp., Anopheles spp., and Culex spp. mosquito larvae, yet were not found to impact the survival of several non-target arthropods17,18 that consumed the yeast. In initial experiments with RNAi yeast, the yeast was heat killed and then dried in a food dehydrator14. This drying procedure19 was suitable for initial proof of concept experiments but is not sufficient for scaled yeast production and could permit the growth of other microbes during the extended drying procedure. To address these concerns, cultures of syt.427 and sema.460 yeast were heat-killed and subjected to spray drying. Initial attempts to spray dry the yeast resulted in inclusion of dried media in the samples, an issue that could make it difficult to determine how much yeast is present in the resulting product, and which may not be desired in treated water containers. This was resolved through the addition of a water washing step prior to drying. The larvicidal activity of syt.427 and sema.460 yeast was retained following spray drying, as demonstrated in laboratory larvicide trials conducted on 20 A. aegypti larvae placed in 3.5 L of water in 7.5 L containers (Fig. 1A, P < 0.001 vs. control spray dried yeast; 3 ± 4% mortality in control containers vs 88 ± 2% and 89 ± 2% for syt.427 and sema.460 respectively) which corresponded roughly to the size of ovitrap containers used in recent field studies in Trinidad20. Significant syt.427 and sema.460 larvicidal activity was observed after two, three, and four weeks of storage of the dried yeast in the dark at room temperature (P < 0.001 vs. control; Fig. 1B; 28 ± 40% vs 85 ± 9% and 90 ± 5%; 13 ± 10% vs 88 ± 3% and 88 ± 8%; 0 ± 0% vs 80 ± 0% and 90 ± 0% at 2, 3 & 4 weeks for the control vs. syt.427 and sema.460 respectively). Although the shelf life of the dried insecticidal yeast was retained over a four-week period, microbial growth was noted in the yeast-treated larvicide trial containers. Furthermore, a higher than normal incidence of control larval death (28 ± 40% and 13 ± 10% at 2 and 3 weeks in Fig. 1B), which is typically close to 0%14, was observed in these experiments. The high rate of control larval death complicated interpretation of these data and would likely hamper longer term storage of the yeast.

Fig. 1.

Larvicidal activity is retained in spray-dried and lyophilized RNAi yeast formulations. Yeast preparations were produced by spray drying a yeast-water mixture (A–C). A wet formulation (WF) consisting of heat-inactivated yeast that was pelleted but not dried served as a control (A, C), as did a control yeast strain (Control) that produces shRNA with no known target in mosquitoes (all panels). WF and spray-dried (SD) formulations of the syt.427 and sema.460 larvicides induced comparable levels of significant larval death (A). The mean results from three replicate trials per treatment conducted on A. aegypti larvae are shown, and errors denote SEM (A-C, *** P < 0.001 vs. controls). Significant syt.427 and sema.460 larvicide activity was also observed (B) after storage of the yeast at room temperature for two (2W), three (3W), and four weeks (4W). Results were combined from three replicate containers per treatment (B; *** = P < 0.001 vs. control). The RNAi larvicides were prepared through spray drying of a yeast-water mixture containing ascorbic acid (AA), benzoic acid (BA), citric acid (CA), potassium sorbate (PS), or no additive (WP). Significant syt.427 activity was observed in comparison to any of these spray dried preparations, as well as to wet formulation control yeast (C) from the same preparations (*** = P < 0.001 vs. any of the WF or spray dried controls). Formulated spray dried larvicide activity was comparable to that of WF syt.427. Larvicides were also prepared through lyophilization of yeast that had been rinsed with water to remove residual culture media (D, E). Significant syt.427 and sema.460 larvicide activity was observed in comparison to control yeast following one (1W), two (2W), three (3W), and four weeks (4W) of storage in the dark at room temperature (D; mean results from three replicate trials per treatment conducted on A. aegypti larvae are shown; *** = P < 0.001 vs. treatments with the control yeast). With respect to control interfering RNA yeast, lyophilized powder syt.427 yeast prepared with benzoic acid preservative induced significant A. aegypti larval mortality following 20 °C frozen or 54 °C accelerated storage (E, *** = P < 0.001; mean results from eight replicate containers per treatment are shown). Data were analyzed with ANOVA/Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Error bars throughout the figure represent SEMs.

In addition to spray drying, preparations of syt.427 and sema.460 yeast were also heat-inactivated and dried through lyophilization. The lyophilized samples were evaluated after one, two, three, and four weeks of storage in the dark at room temperature. In laboratory trials conducted on A. aegypti larvae, both the syt.427 and sema.460 larvicides induced significant larval death with respect to the control samples throughout this time period (P < 0.001; Fig. 1D; 0 ± 0% vs 90 ± 5% and 88 ± 3%; 0 ± 0% vs 93 ± 3% and 92 ± 3%; 0 ± 0% vs 85 ± 5% and 85 ± 5% and 0 ± 0% vs 75 ± 9% and 83 ± 3% at 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks for syt.427 and sema.460 respectively). No larval death was observed in control yeast-treated containers (Fig. 1D). However, similar to trials conducted with spray dried yeast, the growth of microbes was again noted in containers treated with lyophilized yeast. Although the microbes did not kill control larvae in this trial (Fig. 1D), this observation indicated that the addition of preservatives to the yeast larvicide samples could prove useful.

Analysis of larvicides prepared with added preservatives

It was hypothesized that the use of commercial drying procedures, in combination with the addition of antimicrobials, would improve the shelf life of the yeast larvicides and prevent microbial growth on the yeast during larvicide trials. To evaluate this, ascorbic acid (AA), benzoic acid (BA), citric acid (CA), and potassium sorbate (PS), all of which are food-grade level preservatives21 were added to the yeast prior to spray drying, and the activities of these larvicides were assessed. The levels of larval mortality observed following treatments with syt.427 yeast prepared with any of the preservatives is not statistically different from those of non-dried wet formulations of yeast, which induced 88 ± 2% mortality, or to that of spray dried yeast lacking preservatives, which induced 85 ± 2% mortality (Fig. 1C). No significant differences (P > 0.05) were detected in the activities of syt.427 yeast prepared with the different preservatives (Fig. 1C). Moreover, none of the preservatives impacted control yeast-treated larval survival levels (Fig. 1C). The additives themselves do not, therefore, appear to be toxic to larvae or to impact activity of the larvicides. Moreover, microbial growth was not detected in any of the containers treated with larvicides containing preservatives during the trials. These data suggest that any of the four preservatives are suitable for prevention of microbial growth in the yeast larvicides and treated containers. Moreover, given that all the preservatives are food grade additives, it is anticipated that they would be considered safe to use in potable water and would not pose substantial risks to non-target organisms.

While all four anti-microbials preserved the activity of the dried yeast larvicides (Fig. 1C), benzoic acid has low solubility in water22. Given that the larvicides will be used in aquatic habitats, this preservative was selected for all future studies. Moreover, due to the availability of a lyophilizer on site and the relative technical ease of lyophilizing yeast preparations, lyophilized samples were used throughout the remainder of this investigation. It should be noted, however, that industrial scale production operations might opt to use spray drying, which is more cost-efficient at a commercial scale23–26. syt.427 strain yeast, which was used for the remainder of these studies, was lyophilized with benzoic acid and induced significant (88 ± 3% mortality in treated vs. 3 ± 6% mortality in the control) larval death (P ≤ 0.005). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) uses accelerated storage tests27 to assess chemical shelf lives27. In these tests, the insecticides are subjected to accelerated storage at 54 °C for two weeks. A portion of the freshly prepared syt.427 + benzoic acid lyophilized yeast was subjected to these storage conditions, while the other portion was stored at -20 °C. Lyophilized syt.427 yeast powder stored at -20 °C or subjected to accelerated storage conditions induced significant larval mortality with respect to control yeast (Fig. 1E; P ≤ 0.005; 83 ± 5% treatment vs. 3 ± 4% control for WHO accelerated storage and 92 ± 3% treatment vs 1 ± 2% control for -20 °C freezer storage). These results suggest that lyophilized yeast prepared with benzoic acid has an excellent shelf life, and it was anticipated that tableting and encapsulation of this yeast, would further improve its shelf life.

Identification of bulking agents and UV protectant additives that maintain the positive impacts of yeast on A. aegypti oviposition

Bulking agents are used in the preparation of large tablet and briquette formulations. In initial experiments, two starches, maltodextrin and HI-CAP 100, were evaluated as potential bulking agents. Each starch was mixed 1:1 with control and syt.427 dried yeast. However, water in the treated containers was cloudy, and it was anticipated that use of these tablets in the tropics would likely present problems resulting from overgrowth of unwanted microbes in the water containers. Work with these starches was therefore discontinued. β-D-lactose and microcrystalline cellulose were then assessed as potential bulking agents. 400 mg tablets containing 10% control interfering RNA yeast with 90% β-D-lactose or microcrystalline cellulose filler were prepared and evaluated. In both cases, significant control larval death was observed (not shown), and the β-D-lactose also resulted in clouding of the water. The amount of yeast included in each tablet was therefore increased, as there was concern that insufficient nutrition was a potential cause of larval death in these assays. These formulations were further modified through the addition of chitosan, a polysaccharide used in several mosquito larval RNAi studies15,28. These modifications did not improve the outcome for yeast containing β-D-lactose, which still generated cloudy water and control larval death (not shown) and was therefore eliminated from further consideration. The addition of microcrystalline cellulose resulted in negligible (1%) control larval death, with 91 ± 2.5% (P < 0.001 vs. control) larval death resulting from treatments with tablets containing microcrystalline cellulose and chitosan (Fig. 2A), which were subsequently selected as bulking agents.

Fig. 2.

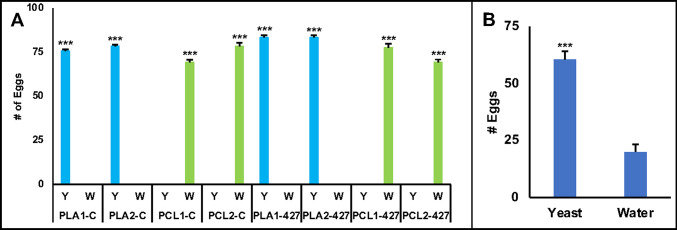

Formulating a controlled-release tablet. A. aegypti larval mortality was observed following larval treatments with tablets containing 20% syt.427 yeast, 20% chitosan, and 60% microcrystalline cellulose (A, *** = P < 0.001 vs. tablets prepared with control yeast, paired two-tailed t-test). The syt.427 tablets containing PLA or PCL induced significant larval mortality (B, *** = P < 0.001 with respect to the control counterpart, ANOVA/Tukey’s multiple comparison test; refer to Table 1 for the compositions of each tablet). The mean results from two replicate trials per treatment are shown in (B), and error bars represent SEMs. The syt.427 tablets containing the UV protectants zinc oxide (ZO) or titanium dioxide (TiO2) induced significant larval mortality (C, *** = P < 0.001 with respect to the control counterpart, ANOVA/Tukey’s multiple comparison test). No significant larvicidal activity was observed in control tablets containing the UV protectants. Tablets contained UV protectants in either 20:20:5:45:10 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:PLA:UV protectant (ZO1 and TiO2-1) or 20:20:5:45:20 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:PLA:UV protectant (ZO2 and TiO2-2). The mean results from three replicate trials per treatment are shown in (C), and error bars represent SEMs. Tablets stored at 54 °C for two weeks in accelerated storage (2W-AS, D) did not have significantly different activity compared to fresh tablets (OW, D). Both the OW and 2W-AS tablets killed significantly more larvae than their control counterparts (D, P < 0.001 is denoted by ***, ANOVA/Tukey’s multiple comparison test; mean results from two replicate trials per treatment are shown, and error bars correspond to SDs).

The microcrystalline cellulose tablets were then evaluated in combination with polylactic acid (PLA) or polycaprolactone (PCL), which were provided in a variety of proportions as noted in Table 1. The conditions of the tablets after five days in water was noted for each formulation (Table 1), and the larvicidal activity of each tablet is shown in Fig. 2B. While all the syt.427 tablets induced significant larval mortality with respect to their relevant control counterparts, some of the tablets resulted in > 5% control mortality (Fig. 2B). This was presumably due to poor growth resulting from insufficient yeast release and occasional films forming at the surface of the water upon release of particulate matter. The potential for these formulations to impact the ability of yeast to promote oviposition in treated containers was also assessed. Although yeast typically promotes oviposition in containers bearing water and yeast (vs. water alone)20, the addition of PCL to the tablets reversed this behavior, with mosquitoes choosing to lay eggs in containers bearing water alone during insectary trials (Fig. 3A). Based on the combined analysis of tablet stability in water (Table 1), the performance of each formulation in larvicide trials (Fig. 2B), and the ability of tablets with PLA, but not PCL, to attract mosquitoes (Fig. 3A), tablet formulations with microcrystalline cellulose, chitosan, and PLA were selected for subsequent work.

Table 1.

Composition of PLA and PCL tablets evaluated.

| Treatments | Description | Tablet condition |

|---|---|---|

| PLA-1 (Control)-T | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Tablet) | Almost Intact |

| PLA-1 (Control)-P | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| PCL-1 (Control)-T | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Tablet) | Almost Intact |

| PCL-1 (Control)-P | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| PLA-2 (Control)-T | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Tablet) | Slightly broken and dispersed |

| PLA-2 (Control)-P | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| PCL-2 (Control)-T | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Tablet) | Broken into small mounds |

| PCL-2 (Control)-P | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| PLA-1 (427b)-T | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Tablet) | Almost Intact |

| PLA-1 (427b)-P | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Powder) | Some component is floating (more than in other containers) |

| PCL-1 (427b)-T | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Tablet) | Almost Intact |

| PCL-1 (427b)-P | 20:20:5:55 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Powder) | Some component is floating (more than in other buckets) |

| PLA-2 (427b)-T | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Tablet) | Has formed a mound |

| PLA-2 (427b)-P | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Lactic Acid (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| PCL-2 (427b)-T | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Tablet) | Formed a mound |

| PCL-2 (427b)-P | 20:20:30:30 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:Poly Caprolactone (Powder) | Floating components observed |

| WP-Control | Wet pellet control for above yeast preparations | Yeast has dispersed and settled on the bottom |

| WP-427b |

The name of the tablet, the composition of the tablet, and the state of the tablet following submersion in water are noted. Results from the larvicide trials performed with each tablet are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Evaluating the impacts of the tablet formulation on A. aegypti oviposition choice. (A) Gravid adult female A. aegypti are not attracted to water treated with tablets containing PCL. The mean number of eggs laid by a gravid female mosquito in three replicate trials per treatment are shown. Although gravid A. aegypti females were attracted to lay eggs in containers treated with tablets containing PLA, the mosquitoes preferred to lay eggs in untreated water vs. water containing tablets with PCL (A, Error bars correspond to SEM; *** = P < 0.001 with respect to the alternative container in each two-point assay, ANOVA/Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Gravid adult female A. aegypti laid significantly more eggs in containers treated with tablets composed of 20:20:5:45:10 yeast:chitosan:microcrystalline cellulose:PLA:titanium dioxide (B; assays were pursued after the tablets had been subjected to accelerated storage conditions; results were compiled from 12 replicate trials/treatment, and error bars correspond to SEM; *** = P < 0.001 with respect to the untreated water container in each two point assay, Mann Whitney U Test).

The addition of titanium dioxide or zinc oxide as UV protectants was also assessed. Both UV protectants are approved as food grade materials in the United States21, and neither had a significant impact on larvicide activity or control survival (Fig. 2C). Although the addition of UV protectants did not impact the performance of the yeast larvicide, these tablets, particularly those containing zinc oxide, disintegrated quickly in water. It was noted that baking the tablets during accelerated storage experiments improved tablet stability, and so this step was included during subsequent tablet preparations. 400 mg tablets composed of 20% syt.427 yeast, 20% chitosan, 5% microcrystalline cellulose, 45% PLA and 10% titanium dioxide (percentages by weight) were prepared and will now be referred to as controlled-release sinking syt.427 tablets. These tablets performed well in accelerated storage assays (Fig. 2D), maintaining an average of 75 ± 5% larvicidal activity through two releases of first instar larvae into 7.5 L containers in the insectary (Fig. 2D, P < 0.001). Moreover, larval attraction to this formulation of yeast tablets was maintained in two-point oviposition assays conducted in the insectary, in which 83% of gravid females preferred to lay eggs in yeast-larvicide treated water vs. water alone (Fig. 3B, P < 0.001).

Controlled-release RNA larvicides display significant residual activity in water

Given the results obtained with the controlled-release tablets, the next goal was to prepare and test a larger sized 5 g briquette (20 yeast: 20 chitosan: 5 microcrystalline cellulose: 45 PLA: 10 titanium dioxide formulation). These briquettes were designed for use in longer assays conducted over several months, during which time the residual activity of the controlled-release formulations could be better assessed. The mean results from two such trials performed in 7.5 L containers in the insectary, the first conducted from July through December 2020, and the second conducted from November 2020 through May 2021, are shown in Fig. 4A. These results demonstrate that the activity of the larvicides was retained over the 5-6 month duration of the experiments, in which an average of 84 ± 5% mortality was observed during each of five releases of 100 larvae in treated containers (P < 0.001 with respect to control containers, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Controlled release syt.427 tablets or briquettes retain larvicidal activity conducted for several months in indoor and outdoor trials. Controlled-release 5 g sinking briquettes killed A. aegypti larvae in simulated field trials conducted in the insectary over the course of 5–6 months (A). The mean larvicidal results from two separate (five and six month) trials, each in which five releases of 100 larvae into 7.5 L containers with 3.5 L of water are shown in A (error bars correspond to SD). The mean mortality of all 10 replicate releases per treatment is shown in (B), and error bars correspond to SEM). A floating version of the syt.427 tablets performed well in semi-field trials conducted in Indiana during the summer of 2021, resulting in significant mortality of A. aegypti larvae in 200 L barrels (C; the mean results from replicate trials for each treatment conducted on 20 larvae are shown, and error bars correspond to SD). Sustained four-month larvicidal activity of sinking syt.427 tablets was observed in semi-field outdoor roof trials conducted in a 220 L barrel in St. Augustine, Trinidad (D, E). Larvicidal activity was maintained through three releases of 150 field strain larvae into the barrels (E); the mean mortality of larvae from the three releases is shown (D); error bars represent SEM. Throughout the figure, *** corresponds to P < 0.001 with respect to control, t-test, two-sample equal variance).

Assessment of controlled-release yeast larvicides in large water storage containers with varying densities of larvae and under semi-field conditions

The next goal was to assess the activity of the larvicide in larger 37.9 L (10 gallon) barrel-sized containers. These assays were conducted outdoors under semi-field conditions in Notre Dame, IN. In preparation for these experiments, we first attempted to rear larvae on a control yeast sinking 400 mg tablet placed in these barrel-sized containers. However, when control larvae were released in the containers, all the larvae died within several days, presumably because they could not swim to the bottom and eat the yeast that had been placed in these large-sized containers with a greater depth than the smaller 7.5 L containers. To address this, a 400 mg floating tablet formulation consisting of tablets prepared with a 9 yeast: 9 PLA: 2 titanium dioxide: 20 beeswax ratio was prepared and used in trials that were completed in the large 37.9 L containers maintained outdoors under semi-field conditions. When floating tablets were used, although the control yeast-treated larvae survived, 93 ± 4% larval mortality was observed in the syt.427-treated barrel (Fig. 4C; P < 0.001).

To account for water containers with higher larval densities, the number of larvae added to the barrels was increased to 1000. This required development of larger 5 g floating briquettes, which were prepared in ratios of 1 yeast: 1PLA: 0.22 titanium dioxide: 0.444 milled beeswax, layered with 1 g milled beeswax then again layered with 5 ml 3:1 melted milled beeswax: hollow glass microspheres to add buoyancy after annealing. The tablets were assessed in barrel assays conducted within the insectary. This floating syt.427 tablet formulation induced significant (P < 0.001) larval death in replicate trials conducted on 1000 A. aegypti larvae (96 ± 3% mortality observed in treatment vs. 13 ± 1% in control), indicating that the yeast formulation was suitable for treatment of large water storage containers with high densities of larvae.

Sustained A. aegypti larval control in large water storage containers in Trinidad

To better simulate natural containers, 220 L barrels were set outdoors for nine months prior to the initiation of larvicide trials in St. Augustine, Trinidad. This permitted deposition and growth of algae and other organic matter, which could be accessed by first instar larvae, permitting the use of sinking yeast briquettes. The barrels were treated with either 5 g control or syt.427 sinking briquettes (80 yeast: 80 chitosan: 20 microcrystalline cellulose: 180 PLA: 40 titanium dioxide). During the four-month trials, three separate batches of 150 A. aegypti larvae were added to each container after the previous batch of larvae in the control-treated barrel matured. Although survival rates were lower in the control barrels (Fig. 4D; 47 ± 3% mortality in the control) than what had been observed in trials conducted outdoors in Indiana (Fig. 4C, 3 ± 4% mortality in the control), survival rates in the syt.427 barrels were significantly lower (P < 0.001) than the control barrels (Fig. 4D; 97 ± 2% mortality in the treatment vs. 47 ± 3% mortality in the control). These results confirmed the ability of sinking controlled release syt.427 briquettes to provide sustained A. aegypti control in large outdoor barrels in the tropics.

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, a heat-inactivated dried yeast was incorporated into a biodegradable matrix containing a mixture of polylactic acid, benzoic acid, and titanium dioxide. The formulation was prepared using food-grade level components to prevent toxicity to humans or other organisms. Both floating (with beeswax and glass microsphere) and sinking (with chitosan) versions of the tablets were prepared for treatment of various sized water containers, including 200 L household water storage tank-sized containers. The tablets passed accelerated storage tests of shelf-life stability and demonstrated up to six months residual activity in water. The yeast performed well in a variety of containers, including water barrels containing 20-1000 larvae each, and in outdoor barrel trials in the tropics. Future studies should include evaluation of the yeast larvicide in larger operational field trials in which the potential for incorporating this new class of larvicides into integrated mosquito control programs can be further assessed. Moreover, once commercial formulations are finalized, registry of the larvicides will likely require further toxicity studies.

As discussed above, the loss of temephos left a gap in the existing larvicide repertoire. It is therefore timely that controlled-release formulations of RNAi yeast were successfully developed and performed well in semi-field trials conducted at two study sites. Although the toxin Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti) is used for larvicidal treatment29 of large water storage containers and potable water, it is not specific to mosquitoes. Moreover, Bt resistance has begun to emerge in a number of crop pests30, highlighting the importance of developing new classes of mosquito-specific larvicides such as RNAi yeast. Likewise, Spinosad31, which is derived from a soil bacterium, is approved for treatment of drinking water, but resistance has begun to emerge to this broad-spectrum insecticide32. The insect growth regulators pyriproxyfen and methoprene are approved for drinking water treatment. Pyriproxyfen, which can be dispersed by mosquitoes during skip oviposition, is relatively safe for vertebrate organisms, but is not specific to mosquitoes and can kill other insects33. Although methoprene does not pose unreasonable risks to human health, it is extremely toxic to other invertebrate species34, and reduced susceptibility has begun to emerge35,36. The potential for introducing RNAi yeast to Aedes mosquito control programs, which could be rotated with the use of these other larvicides, may prove beneficial for reducing the incidence of larvicide resistance, while also offering an alternative that is designed to be specific to mosquitoes, allowing non-targets to survive. Large-scaled larvicide trials should be conducted in support of potential future registry applications to the U.S. EPA and the WHO.

In addition to Aedes mosquitoes, the syt.427 larvicide, as well as a number of other existing RNAi yeast larvicide strains that have been developed, including a robust commercial-ready strain that silences the Shaker gene37, target conserved sites in Anopheles spp. and Culex spp. mosquitoes17. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a vector alert noting that the spread of Anopheles stephensi (Liston, 1901) is a major threat to malaria control and elimination in Africa and southern Asia and urging for immediate action to control the spread of this insect38. A. stephensi, which has adapted to developing in a wide variety of human-made containers, is susceptible to larvicides39,40. The WHO recommends that larviciding be considered for malaria control in areas where breeding sites are few, fixed, and findable39, suggesting that RNAi yeast larvicides may prove invaluable in the fight to control this invasive malaria mosquito. Moreover, larvicides are also used for control of Culex spp. mosquitoes. For example, the North Shore Mosquito Abatement District has applied a variety of larvicides to catch basins in Chicago since the mid-1990s, and it will be interesting to ascertain whether these controlled-release tablets, or perhaps other yeast formulations, will be useful for treatment of catch basins41,42. Past studies suggest that selection of the proper formulation will be critical for catch basin treatments, where loss of larvicides over time can be an issue43. Evaluation of yeast larvicides in catch basins will inform the best strategies for RNAi yeast larvicide formulation and deployment for control of Culex spp. mosquitoes. RNAi yeast larvicides, which can readily be incorporated into useful controlled-release formulations, may prove invaluable for the control of Aedes spp., Anopheles spp., and Culex spp. mosquitoes.

Materials and methods

Materials

Materials used for tablet preparation: The following materials were acquired and used for tablet preparation: beeswax (yellow, Strahl & Pitsch SP66G, 0911/15), chitosan (Sigma-Aldrich C3646), hollow glass microspheres (System Three, 646697002783), microcrystalline cellulose (MCC, Alfa Aesar A17730.36), polylactide acid resin (PLA; Natureworks Ingeo Biopolymer 6362D, CK0528B131), and titanium dioxide (TiO2, Spectrum Chemical T1083). Additional materials evaluated during the formulation studies included: β-D-lactose (Acros Organics), maltodextrin (Maltrin M180, Grain Processing Corporation, modified food starch (HI-CAP 100, Ingredion), zinc oxide, poly(caprolactone) (PCL Resomer C209, Evonik).

Milling of beeswax: Beeswax was milled using a laboratory scale hammer mill (Fitzpatrick Hammer Mill, model L1A). The mill was operated with liquid nitrogen and a 3.96 mm screen. The beeswax was submerged in liquid nitrogen prior to milling, which was required to reduce the particle size and to prepare a uniform blend of powder for tableting. Particle size analysis (Malvern Mastersizer 3000) was used to quantify the particle size of the cryomilled beeswax, which was 60.4 Dx (10) (μm), 241 Dx (50) (μm), 490 Dx (90) (μm) with a 1.785 span.

Preparation of PLA: Spray drying was used to micronize the PLA, which was required to reduce the particle size and to prepare a uniform blend of powder for tableting. 40 g of PLA was dissolved into 1560 g of acetone. The solution was spray dried with a Pro-C-epT 4M8 laboratory scale spray dryer under the following configuration and conditions: 0.4 mm nozzle bifluid nozzle, 3.0 bar atomizing air pressure, 80 °C inlet air temperature, 6 g/min feed rate, and 0.3 mw/min air speed. Particle size analysis (Malvern Mastersizer 3000) was used to verify the particle size of the spray dried PLA, which was 1.30 Dx (10) (μm), 12.1 Dx (50) (μm), 155 Dx (90) (μm) with a 12.669 span.

Yeast preparation, drying, transport, and storage

Yeast strains: Stable transformants expressing syt.42717, sema.46018, or control14 shRNA were used in this investigation.

Yeast cultivation: Culturing and galactose induction was performed as described14. Yeast was then heat-killed and pelleted as described19.

Transport and storage of yeast: Spray dried or lyophilized yeast was shipped to the Scheel laboratory on ice packs via overnight courier service. Prior to shipment and upon arrival at the final destination, yeast was stored at − 20 °C unless specified otherwise. Pelleted yeast that had not been dried was stored in glass vials, packaged on ice, and shipped overnight. Such samples served as wet formulation (WF) controls.

Spray drying: Spray drying was performed with a Pro-C-epT 4M8 laboratory scale spray dryer. Yeast media was pumped into the spray dryer at 5–6 g/min. The fluid was atomized with a 0.6 mm diameter air atomized nozzle with an atomizing pressure of 3.0 bar. The spray dryer inlet temperature was set to 180 °C, resulting in an outlet temperature of 45-55 °C, depending upon the formulation. Air flow through the spray dryer was set to 0.3 m3/min. For initial spray dry preparations, media was used as the carrier during the spray drying process. However roughly half of the spray dried material, which had a powder-like consistency, was composed of dried media. Therefore, in all subsequent preparations, and for the experiments described herein, the yeast was pelleted through centrifugation, and excess media was removed. The yeast was then resuspended in e-pure water and spray dried. The resulting preparations contained only dried yeast and lacked dried media.

Lyophilization: Following pelleting, the yeast was rinsed by resuspending it in 10 ml of e-pure water prior to heat killing at 70 °C for 25 min. Following the addition of preservative, the centrifuge tube was submerged in liquid nitrogen until frozen then placed on a Labconco FreeZone 6 L Console Freeze Dryer (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) for 48-72 h until dry.

To assess preservatives, the following food-grade preservatives were added to yeast cultures after pelleting and resuspension in water prior to drying of the yeast: 0.1% ascorbic acid, 0.1% benzoic acid, 0.1% citric acid, or 0.1% potassium sorbate. After evaluation of these preservatives, 0.1% benzoic acid was selected as the preservative of choice and used in the remainder of the experiments.

Assessment of shelf life: For evaluation of shelf life, yeast was stored in the dark at room temperature (~ 22 °C on average). Samples were stored for 0-4 weeks after shipment and then evaluated in larvicide trials. Accelerated storage tests were also pursued through storage of yeast at 54 °C for two weeks per the protocol described by the EPA27.

Preparation of controlled release sinking briquettes

The following procedure produced fourteen 5.0 g briquettes of control or syt.427 yeast per production: 17 g of control or syt.427 yeast, 17 g of chitosan, 4.25 g of MCC, 38.25 g of spray dried PLA, and 8.5 g of TiO2 were combined and blended using a FlackTek DAC 150.1 FV Speed Mixer for 1 min at 2000 rpms. Each tablet was then produced using a 5.0 g portion from the master mix that was transferred to a 25 mm diameter die set (Pellet Press Die Sets, Traverse City, MI). The die plunger was inserted, and the tablet was formed using a Model C Carver Laboratory Press at 12 tons for 15 s. Tablets were then removed from the die, covered with aluminum foil, then heat treated at 57 °C for 72 h. No additional materials were needed to promote sinking of the tablets.

β-D-lactose, maltodextrin, and HI-CAP 100 were also assessed as bulking agents in place of the MCC, though not selected for use in the final tablet formulation. PCL and PLA were initially assessed at a variety of concentrations (see Table 1) prior to development of the above sinking tablet formulation. Zinc oxide was also evaluated but not selected as a U.V. protectant.

Preparation of controlled release floating tablets and briquettes

The following materials, which yielded eight 5 g briquettes of control or syt.427 yeast, were blended at 200 rpms for 1 min with a FlackTek DAC 150.1 FV Speedmixer: 10 g yeast, 10 g spray dried PLA, 2.2 g TiO2, and 4.44 g beeswax. For each briquette, 1 g of milled beeswax followed by 2.66 g of the above mixture were layered into a 25 mm diameter die set (Pellet Press Die Sets, Traverse City, MI) then pressed using a Model C Carver Press at 12 tons for 15 s. The tablets were then placed into a weight boat wax side up, covered with aluminum foil, and heat treated at 57 °C for 72 h. Separately, > 10 g of a 3:1 ratio of beeswax to hollow glass microspheres were prepared and heated using a hot plate while stirring manually with a metal spatula until the wax was melted and the mixture was evenly dispersed. Immediately upon removing the tablet from the oven, it was placed back into the die, beeswax side up. Using a serological pipette, ~ 5 ml of molten wax/beads mixture was placed into the die and gently pressed, letting the plunger fall naturally. Six 400 mg tablets of control and syt. 427 were also prepared by combing these materials in the following ratio: 90 control or syt.427,90 spray dried PLA, and 20 TiO2. The materials were speed mixed at 2000 rpms for 1 min. Each tablet was prepared with 200 mg of the master mix that was transferred to a 12 mm diameter die set (Pellet Press Die Sets, Traverse City, MI). 200 mg of hand cut beeswax was then layered on top of the master mix layer and pressed 3.5 tons for 15 s. The tablets were then placed in a weigh boat, wax side up, covered with aluminum foil, and heat treated at 57 °C for 72 h.

Mosquito rearing

Indiana insectary: A. aegypti Liverpool-IB12 (LVP-IB12) mosquitoes were reared as described according to established protocols44 within an insectary maintained at a temperature of 26.5 °C, an approximate relative humidity of 80%, and with a 12-h light and dark cycle featuring 1-h crepuscular periods at the beginning and end of each cycle. Larvae were fed with liver powder (900396, MP Biologicals, Solon, OH, USA); male and female adult mosquitoes were supplied a 10% sucrose solution, while adult females were provided with defibrinated sheep blood meals (HemoStat Laboratories located in Dixon, CA, USA) using an artificial membrane feeding system (Hemotek Limited, Blackburn, UK).

Trinidad insectary: A. aegypti that had been collected in Trinidad (Diego Martin, Maraval and St. Augustine) were used to establish laboratory colonies; the larvae used in the larvicide trial were approximately fifth generation. The insectary in Trinidad was maintained at ambient temperature and humidity conditions, and adult female mosquitoes were blood fed as described above but using fresh sheep’s blood provided by the School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Mt. Hope, UWI.

Larvicide assays

Small container assays: With the exception of the residual studies, large container assays, and semi-field trials (see below), larvicide assays were performed in the insectary as described (Mysore et al. 2018) and conducted in 7.5 L containers bearing 3.5 L of water (which was approximately the container size/water volume of containers used in recent ovitrap trials conducted in Trinidad20). These assays conformed to the guidelines of the World Health Organization45. Each replicate assay was performed using 20 first instar A. aegypti Liverpool-IB12 (LVP-IB12) strain mosquitoes per treatment. Depending on the amount of materials available at each step in the tablet design process, one or more replicate container trials were performed.

Residual activity assays in 7.5 L containers: 100 first instar A. aegypti larvae were added to each of two 7.5 L containers bearing 3.5 L of water. One container was treated with a 5 g syt.427 larvicide tablet and the other with a 5 g control interfering RNA tablet. Control- and syt.427-treated larval mortality was recorded. Upon emergence of any surviving animals as adult mosquitoes, a new set of 100 first instar larvae was added to each container (termed release 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 herein). This occurred approximately once per month.

Large container trials in Indiana: Large water container trials were conducted in a similar manner, except that 200 L of water was placed in Rubbermaid Commercial 37.2 L (10 gallon) Round Plastic Brute Container (Rubbermaid, Atlanta, GA). These trials were initially performed in the insectary.

Semi-field trials in large containers: The large container trials were also performed under semi-field conditions in Indiana and Trinidad and were conducted in accordance with the World Health Organization larvicide testing guidelines45. The trials performed in Notre Dame, Indiana were conducted in June and August 2021 on 20 first instar larvae placed in 200 L of water contained in a Rubbermaid Commercial 37.2 L (10 gallon) Round Plastic Brute Container (Rubbermaid, Atlanta, GA). Each container was treated with one sinking and one floating 0.4 g tablet and covered with mesh to prevent the entry or exit of any organisms.

The trials performed in Trinidad were conducted from October 2023 through January 2024 and performed in 220 L barrels that had been filled with tap water. The barrels were placed outdoors (uncovered) for nine months prior to the start of the trials, then covered with 1 mm mesh for one month prior to the start of the experiment to ensure that no natural mosquito activity remained, then topped off with water to bring the volume to 140 L. 5 g sinking yeast briquettes (control or syt.427) were added to the barrels. 150 first instar larvae were then added to the barrels, which were then covered with 1 mm mesh, preventing the entry or exit of any other organisms during the trial. A new set of 150 first instar larvae was added to each container after the prior set had died or emerged (referred to as releases 1, 2, and 3 herein).

Analysis of larvicide data: The percentages of larval mortality for replicates of each treatment were transformed using the arcsine transformation prior to analyzing the data using ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc test), Student’s t-test, or Mann Whitney U test as indicated in the figure legends.

Ethics statement: No vertebrate animals were used directly in these studies, as mosquitoes were blood fed with a membrane feeding system as described above. The semi-field trials were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of the West Indies (Study CEC403/12/17), the chair of the UWI St. Augustine Department of Life Sciences, and the Southwest Regional Health Authority, a division of the Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our labs for their advice, as well as Longhua Sun, Britton Sofhauser, Joi Misenti, Joe Roethele, and Diana Cervera for technical support.

Author contributions

K.M., J.D.O, C.D., D.W.S. and M.D.S. designed and conceived the study; J.D.O., C.D., and C.C-G designed and prepared the yeast tablets with input from K.M., D.W.S., and M.D.S; K.M. performed the Indiana larvicide trials, and A.T.M.S., N.W., R.S.F, L.D.J., and S.S. carried out the trials in Trinidad; K.M., D.W.S., and M.D.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, which was edited by all the authors; D.W.S. and M.D.S. obtained funding; J.D.O., C.D., A.M., D.W.S. and M.D.S. supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Innovative Vector Control Consortium funded the formulation and barrel studies. The ovitrap container studies were supported by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program under Award No. W81XWH-17-1-0294 and W81XWH-17-1-0295 (to M.D.S. and D.W.S., respectively).

Data availability

All data are available within the text of this article.

Competing interests

The funders of this work did not play a role in the design of this study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to publish the results of this investigation. The opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the manuscript’s authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity. In the conduction of research utilizing recombinant DNA, the investigator adhered to NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules. Although MDS and DWS are inventors on U.S. patent No: 62/361,704, European Application No. 17828458.4, which was filed by Indiana University, this did not affect their interpretations of the data presented in this manuscript and does not impact their adherence to journal policies on sharing data and materials. The research findings presented herein are not related to any products or services currently provided by any third parties. Although MDS is serving as a guest editor for the Vector Control for Neglected Diseases Collection, she had no involvement with the review of this manuscript at Scientific Reports. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.CDC. Mosquitoes. https://www.cdc.gov (2024).

- 2.PAHO. PAHO calls for collective action in response to record increase in dengue cases in the Americas. https://www.paho.org/en/news/28-3-2024-paho-calls-collective-action-response-record-increase-dengue-cases-americas (2024).

- 3.BASF. Abate® Larvicides—Stop disease-causing insects before they hatch. https://agriculture.basf.com/global/en/business-areas/public-health/products/abate.html (2014).

- 4.Chadee, D. D., Doon, R. & Severson, D. W. Surveillance of dengue fever cases using a novel Aedes aegypti population sampling method in Trinidad, West Indies: The cardinal points approach. Acta Trop.104, 1–7. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.06.006 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzarri, M. B. & Georghiou, G. P. Characterization of resistance to organophoshate, carbamate, and pyrethroid insecticides in field population of Aedes aegypti from Venezuela. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc.11(3), 315–322 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saavedra-Rodriguez, K. et al. Differential transcription profiles in Aedes aegypti detoxification genes after temephos selection. Insect Mol. Biol.23, 199–215. 10.1111/imb.12073 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EPA. Signed temephos registration review. https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0444-0019 (2011).

- 8.Airs, P. M. & Bartholomay, L. C. RNA Interference for mosquito and mosquito-borne disease control. Insects8 (2017). 10.3390/insects8010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Yu, N. et al. Delivery of dsRNA for RNAi in insects: an overview and future directions. Insect Sci.20, 4–14. 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01534.x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, H., Li, H. C. & Miao, X. X. Feasibility, limitation and possible solutions of RNAi-based technology for insect pest control. Insect Sci.20, 15–30. 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01513.x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, J., Wang, X. P., Wang, M. Q., Ma, W. H. & Hua, H. X. Advances in the use of the RNA interference technique in Hemiptera. Insect Sci.20, 31–39. 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01550.x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum, J. A. et al. Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol.25, 1322–1326. 10.1038/nbt1359 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duman-Scheel, M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) as an interfering RNA expression and delivery system. Curr. Drug Targets20, 942–952. 10.2174/1389450120666181126123538 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hapairai, L. K. et al. Lure-and-kill yeast interfering RNA larvicides targeting neural genes in the human disease vector mosquito Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep.7, 13223. 10.1038/s41598-017-13566-y (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mysore, K., Flannery, E. M., Tomchaney, M., Severson, D. W. & Duman-Scheel, M. Disruption of Aedes aegypti olfactory system development through chitosan/siRNA nanoparticle targeting of semaphorin-1a. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.7, e2215. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002215 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mysore, K. et al. Characterization of a dual-action adulticidal and larvicidal interfering RNA pesticide targeting the Shaker gene of multiple disease vector mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.14, e0008479. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008479 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mysore, K. et al. Characterization of a yeast interfering RNA larvicide with a target site conserved in the synaptotagmin gene of multiple disease vector mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.13, e0007422. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007422 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mysore, K. et al. Characterization of a broad-based mosquito yeast interfering RNA larvicide with a conserved target site in mosquito semaphorin-1a genes. Parasit. Vectors12, 256. 10.1186/s13071-019-3504-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mysore, K. et al. Preparation and use of a yeast shRNA delivery system for gene silencing in mosquitol larvae. Methods Mol. Biol.1858, 213–231. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8775-7_15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hapairai, L. K. et al. Evaluation of large volume yeast interfering RNA lure-and-kill ovitraps for attraction and control of Aedes mosquitoes. Med. Vet. Entomol.35, 361–370. 10.1111/mve.12504 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FDA. Food additive status list. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/food-additive-status-list (2024).

- 22.National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary Benzoic Acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Benzoic-Acid (2024).

- 23.Acar, C., Dincer, I. & Mujumdar, A. A comprehensive review of recent advances in renewable-based drying technologies for a sustainable future. Dry Technol.40, 1029–1050. 10.1080/07373937.2020.1848858 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fathi, F., Ebrahimi, S. N., Matos, L. C., Oliveira, M. B. P. P. & Alves, R. C. Emerging drying techniques for food safety and quality: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.21, 1125–1160. 10.1111/1541-4337.12898 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peighambardoust, S. H., Tafti, A. G. & Hesari, J. Application of spray drying for preservation of lactic acid starter cultures: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol.22, 215–224. 10.1016/j.tifs.2011.01.009 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khuenpet, K. C. N., Jaijit, S., Arayapoonpong, S. & Jittanit, W. Investigation of suitable spray drying conditions for sugarcane juice powder production with an energy consumption study. Agric. Nat. Resour.50(2), 149–145 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.EPA. Accelerated storage stability and corrosion characteristics study protocol. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/accelerated-storage-stability-and-corrosion-characteristics-study-protocol (2024).

- 28.Zhang, X. et al. Chitosan/interfering RNA nanoparticle mediated gene silencing in disease vector mosquito larvae. J. Vis. Exp.10.3791/52523 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.EPA. Bti for Mosquito Control (2023).

- 30.Alam, I. et al. Role of lectin in the response of Aedes aegypti against Bt Toxin. Front Immunol13, 898198. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.898198 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bunch, T. R., Bond, C., Buhl, K. & Stone, D. Spinosad General Fact Sheet. http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/spinosadgen.html (2014).

- 32.Lan, J. et al. Identification of the Aedes aegypti nAChR gene family and molecular target of spinosad. Pest. Manag. Sci.77, 1633–1641. 10.1002/ps.6183 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGregor, B. L. & Connelly, C. R. A review of the control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the continental United States. J. Med. Entomol.58, 10–25. 10.1093/jme/tjaa157 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EPA. Methoprene. https://archive.epa.gov/pesticides/reregistration/web/pdf/0030fact.pdf (1991).

- 35.Marcombe, S., Farajollahi, A., Healy, S. P., Clark, G. G. & Fonseca, D. M. Insecticide resistance status of United States populations of Aedes albopictus and mechanisms involved. PLoS One9, e101992. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101992 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau, K. W., Chen, C. D., Lee, H. L., Norma-Rashid, Y. & Sofian-Azirun, M. Evaluation of insect growth regulators against field-collected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Malaysia. J. Med. Entomol.52, 199–206. 10.1093/jme/tju019 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brizzee, C. et al. Targeting mosquitoes through generation of an insecticidal RNAi yeast strain using Cas-CLOVER and super piggyBac engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Fungi9 (2023). 10.3390/jof9111056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.WHO. Vector alert: Anopheles stephensi invasion and spread (2019).

- 39.WHO. Larval source management: A supplementary measure for malaria vector control. An operational manual.https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/85379/9789241505604_eng.pdf (2012).

- 40.Mnzava, A., Monroe, A. C. & Okumu, F. Anopheles stephensi in Africa requires a more integrated response. Malar J21, 156. 10.1186/s12936-022-04197-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harbison, J. E., Henry, M., Xamplas, C. & Dugas, L. R. Evaluation of Culex pipiens populations in a residential area with a high density of catch basins in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc.30, 228–230. 10.2987/14-6414R.1 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harbison, J. E. et al. Variable Efficacy of extended-release mosquito larvicides observed in catch basins in the northeast Chicago metropolitan area. Environ. Health Insights10, 65–68. 10.4137/EHI.S38096 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harbison, J. E. et al. Observed loss and ineffectiveness of mosquito larvicides applied to catch basins in the northern suburbs of Chicago IL, 2014. Environ. Health Insights9, 1–5. 10.4137/EHI.S24311 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clemons, A., Mori, A., Haugen, M., Severson, D. W. & Duman-Scheel, M. Culturing and egg collection of Aedes aegypti. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc.2010, pdb prot5507. 10.1101/pdb.prot5507 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO. Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-WHOPES-GCDPP-2005.13 (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within the text of this article.