Introduction

Over 62 million Latino individuals resided in the United States (U.S.) in 2020, accounting for half of the U.S. total population growth from 2010 to 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau). In addition to being the largest ethnic minority group in the country, Latinos comprise the youngest segment of the population, with one-third being under the age of 18 years1,2. Despite their demographic significance, Latino youth, like other racial/ethnic minority groups in the U.S., are more apt to suffer from mental health disparities than their non-Latino White peers. For example, Latino youth report higher rates of anxiety3,4, depression5, suicidal ideation and attempts6,7, and higher rates of comorbidity when compared to their non-Latino peers8. Anxiety disorder diagnoses have tripled among Latino youth since 2017, with factors such as racial discrimination, parental separation, deportation fears, and specifically, chronic levels of stress implicated in this surge3,9,10.

Within the realm of stress, acculturative stress—the psychosocial strain experienced by immigrants in response to challenging events when adapting to a new culture – is a significant predictor of anxiety and depressive symptoms among immigrant populations, including Latinos11–14. Berry conceptually linked acculturative stress to other stress models (e.g.,15) and posited it as a psychological response to environmental stressors such as language barriers, difficulties with assimilating beliefs and norms of the host culture, and lack of social support11. While research on acculturative stress has gained traction in the clinical16,17 and research literatures18,19, it has primarily centered on adults within the Latino community, leaving gaps in understanding its phenomenology on children.

In line with bioecological models of child development20, this chapter reviews the literature on acculturative stress among Latino youth, focusing on individual, family/social, and societal factors that influence or mitigate acculturative stress. Examining individual factors, we review research on sex and age effects, temperament, cognitive factors, emotion dysregulation, and language acquisition21–28. Shifting to family/social factors, we focus on family functioning, social support, and parental emotion socialization, given their direct and indirect associations with acculturative stress among Latino youth29–35. Finally, drawing from prior research36–39, we summarize findings regarding societal processes linked to acculturative stress, including racial discrimination, socioeconomic status and economic instability, sociopolitical context, and immigration-related fears. The chapter concludes by presenting a bioecological framework for understanding acculturative stress among Latino youth and offering recommendations for providers working with this population.

Individual Factors

Child Sex and Age

Research shows that Latina girls, compared to boys, experience higher acculturative stress, leading to elevated anxiety, depression, and risky behaviors40–43. This vulnerability may be partially attributed to gendered socialization, as Latina girls are expected to adhere to familismo values (which emphasize family cohesion above individual needs), potentially resulting in increased interfamilial stress44,45. Separate work suggests that Latina girls, given social freedoms in U.S (vs. Latino) culture, may acculturate faster, leading to parent-child acculturative gaps and family conflict46.

Moreover, traditional gender role beliefs (e.g., “men don’t cry”) may lead Latino young men to suppress emotions and avoid seeking mental health support, contributing to acculturative stress and mental health problems47. For example, one study found that after accounting for U.S. culture acquisition, heritage-culture retention, and acculturative stress, Latino men (vs. women) exhibited higher depression symptoms, while stronger affiliations with U.S. cultural practices were associated with greater acculturative stress and depressive symptoms among Latinas, possibly due to mismatches with gender role expectations47. Notably, parental support, especially for boys, may help Latino youth cope with acculturative stress. In one study, parental support mitigated the negative effects of acculturative stress and family conflict on the prosocial behaviors of boys48, whereas among girls, it buffered only the negative effect of family conflict, not acculturative stress48.

The effects of child age on acculturative stress have also been examined. Sirin and colleagues prospectively examined the influence of gender, age, generation status, and acculturative stress on depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms trajectories among immigrant adolescents in 10th, 11th, and 12th grade. Consistent with past work49, mental health problems decreased over time for all age groups50. Acculturative stress had a moderating effect, with internalizing symptoms increasing as acculturative stress increased50. The age of immigration, in particular, may be especially relevant to acculturative stress, as younger arrivals experience less immigration stress, while discrimination stress affects Latino youth across all age groups24.

Collectively, these findings suggest that girls may be at increased risk for acculturative stress, parental support may be key in mitigating acculturative stress (especially in boys), and the age of arrival may influence facets of acculturative stress. Further research is warranted to understand the mechanisms linking child sex and age to acculturative stress and emotional health among Latino youth.

Temperament

Temperament plays an important role in shaping how children respond to environmental stress51,52, with individual differences potentially accounting for diverse reactions to acculturative stress. For example, in the context of school-based racial discrimination, children may exhibit distinct abilities to cope with stress. While one child may effectively regulate their emotions and pursue goal-oriented actions despite distress, another may experience heightened physiological dysregulation, anxiety, and avoidance. Consequently, acculturative stress could potentially intensify maladaptive behavioral and emotional responses in Latino children with sensitive temperaments.

Although research in this area is highly limited, behavioral inhibition stands out as a temperamental trait explored in relation to Latino youth’s acculturative stress23,27. Behavioral inhibition is characterized by high levels of restraint, avoidance, and social withdrawal in novel situations, and is a well-established risk factor for childhood internalizing and externalizing problems53–57. Cultural factors among Latino youth, such as higher familismo and respeto (respect towards elders and authority figures;58, and more traditional gender roles59, are linked to higher behavioral inhibition. Theoretically, high acculturative stress among Latino youth with high levels of behavioral inhibition might lead to further social withdrawal and isolation, heightening risk for anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns. However, Gomez and Gudiño did not find support for an association between behavioral inhibition and acculturative stress in a sample of Latino adolescents. Additionally, and contrary to prediction, behavioral inhibition did not moderate the relationship between acculturative stress and internalizing symptoms23. Clearly, more research is needed to understand how children’s temperamental responses may influence the acculturation process.

Cognitive Factors

Stress and negative life events can activate maladaptive coping methods, such as negative automatic thoughts, which are reinforced through repeated exposure to stressors60,61. Consequently, acculturative stress among Latino youth may be linked to higher frequency of negative automatic thoughts. In this vein, Schlaudt and colleagues found that acculturative stress was associated with greater negative automatic thoughts in a sample of first- and second-generation immigrant Latino youth. Notably, this association was only found among those with low and average (but not high) levels of mindfulness25, suggesting a potentially protective effect of mindfulness.

Anxiety sensitivity (AS), defined as the fear of anxiety-related sensations and the misinterpretation of such sensations as dangerous62, is another relevant cognitive risk factor that may hinder Latino youth’s ability to cope with acculturative stress. Although no research focusing on youth has explored associations between acculturative stress and AS, findings in the adult literature suggest clinically relevant associations63–65. For example, Jardin and colleagues found that AS explained the associations between acculturative stress and symptoms of social anxiety, depression, anxious arousal, and suicidality among Latino college students63. The experience of acculturative stress may be accompanied by physiological hyperarousal25,66, potentially exacerbated by a tendency to catastrophize interoceptive sensations (i.e., high AS67). Therefore, it is theoretically possible that AS may amplify acculturative stress and internalizing symptom associations among Latino youth. Future research examining the role of AS in Latino youth’s acculturative stress is warranted.

Emotion Dysregulation

Latino youth report higher levels of discrimination and stress68,69, feelings of rejection, a sense of limited future, and devalued Latino identity70. These acculturation-related stressors may contribute to emotion dysregulation (i.e., a pattern of emotional expressions and increased physiological arousal leading to long-term maladaptation71 and greater psychopathology68,69,72 among Latino youth28). Zhang and Gonzales-Backen found that greater acculturative stress was associated with higher levels of rule-breaking behaviors through elevated depressive symptoms, particularly among Latino adolescents with low levels of emotion regulation28. Additionally, Archuleta found that first-generation Latino youth exhibiting greater acculturation to White American culture reported greater emotion dysregulation. Conversely, positive relationships with others, a sense of purpose in life, and environmental mastery were associated with better emotion regulation and lower levels of psychopathology73. These findings collectively suggest that emotion regulation significantly influences Latino youth’s ability to cope with acculturative stress, highlighting the potential disruption in regulatory capacities by greater acculturative stress. Considering the malleability of emotion regulation skills, these findings emphasize emotion regulation as a potential intervention target in this population.

Language Acquisition

Learning a new language is a robust risk factor for acculturative stress21,22,26. Spanish-speaking Latino youth who are learning English report feelings of hopelessness and insecurity, describing the process as stressful22. Learning a new language and being bilingual may also require youth to frequently alternate between languages and cultural contexts. This cognitive process of switching between different cultural frames as a response to social demand may lead to increased stress74. Booth and colleagues found that bilingualism, and the associated difficulties with expressing ideas and knowledge when switching between English and Spanish at school, were key stressors in the acculturation process of Latino youth21.

Likewise, the pressure of language brokering, defined as acting as a linguistic and cultural intermediary for two or more parties from different cultural backgrounds with little to no formal training75, is a common source of acculturative stress among Latino youth. Latino youth may be required to act as a translator for their parents, reading documents, translating during social interactions, or functioning as the main source of communication in medical emergencies. Acculturative stress in response to brokering is linked with the youth’s comfort with the language, frequency of brokering, and their perceptions surrounding brokering75–78. Kam and colleagues identified three brokering profiles among immigrant youth: (1) infrequent-ambivalent, (2) occasional-moderates, and (3) parentified-endorsers. The largest profile, occasional-moderates, reported occasional brokering demands, low levels of family-based acculturation stress and parentification, and a moderate endorsement of positive brokering beliefs76. The authors concluded that most adolescents who identify in the occasional-moderate profile view their brokering as a normal family role and typically demonstrate strong links with their ethnic identity76.

Yet, when youth have a higher demand of brokering or perceive brokering negatively, acculturative stress may increase. Using longitudinal survey data from 234 Latino early adolescents in 6th–8th grades, Kam and Lazarevic found that brokering for parents indirectly affected alcohol and marijuana use through family-based acculturative stress75. Specifically, brokering functioned as a stressor when Latino early adolescents perceived brokering as a burden, which indirectly increased acculturative stress in the family and adolescent alcohol and marijuana use75.

While learning a new language can be mentally demanding, being bilingual offers various advantages. Bilingualism helps youth establish connections with peers, navigate social interactions, strengthen their ethnic identity, and foster a sense of pride21. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that bilingualism acts as a protective factor, enabling youth to function effectively in diverse settings79,80. In sum, even though the process of learning a new language can be highly stressful for Latino youth, achieving proficiency in a new language may serve as a protective factor against psychopathology.

Family/Social Factors

Family Functioning

Supportive family relationships can serve as a protective factor against acculturative stress in Latino youth34. For example, Latino youth who felt supported by their parents and community, or had a strong family obligation, developed coping strategies, exhibited socioeconomic mobility, and achieved higher academic success29. Conversely, youth who reported feeling isolated from their parents and families exhibited “escaping strategies,” such as moving out of their parents’ home, dropping out of school, and spending time with delinquent peers29, which were linked with delinquent behaviors and increased drug use29.

Family cohesion also serves as a protective factor against facets of acculturative stress, including discrimination and adaptation stress, among Latino youth30,33. Although not specifically focused on acculturative stress, research has found that within Latino families, family support is also linked with better emotional regulation, parent-child relationship quality, and youth’s overall functioning across settings30–33,35. Positive family functioning also predicted higher self-esteem, lower symptoms of depression, lower aggressive and rule-breaking behavior, lower alcohol use, and lower cigarette use among recent-immigrant Latino adolescents32.

While family functioning and cohesion are integral for Latinos’ adaptation to a new culture, immigrant families, including parents and extended family, may face an increased risk of developing maladaptive strategies due to heightened acculturative stress. Therefore, future research should focus not only on the impact of acculturative stress on Latino youth’s psychological outcomes but also examine its direct and indirect effects on parents and the family as a whole. Indeed, parental acculturative stress is associated with Latino youth’s conduct problems, anxiety, and depressive symptoms81,82. A recent study by Wu and colleagues also found that Latino youth exhibited more severe depressive symptomology when both parent and child reported higher acculturative stress82. Therefore, in efforts to enhance Latino youth’s psychological well-being, it is essential to provide support not only to the youth but also their parents.

Social Support

The importance of social support, particularly peer support, in children’s psychosocial development is well-established83–85. Children generally consider their peers as equal, providing companionship, entertainment, and support83–85. Peers also provide emotional support and model emotion regulation skills, as over time children begin to lean less on parental figures for their emotional needs. Peer social support may protect mental health and foster resilience in Latino youth—even more so than family support18,86. In the context of acculturative stress, healthy peer relationships and social support may buffer against anxiety and internalizing symptoms4,18,87. One study found that youth report of social support, addressing both academic and emotional needs, mediated the relation between acculturative stress and internalizing symptoms among first-generation Latino immigrants87. Consistent with these findings, Wasserman and colleagues found that levels of peer support (but not parent support) mitigated the effects of acculturative stress on Latino adolescents’ depression and anxiety symptoms4. Peer support may therefore play a critical role in Latino youths’ ability to adjust to a new culture.

Emotion Socialization

Emotion socialization is defined as the ways in which parents directly and indirectly teach their children about the meaning of emotions and how to respond to their own and others’ emotions88,89. Healthy parent-child interactions are therefore central to adequate emotion socialization, with chronic dysregulation in these interactions posing an increased risk of socioemotional problems in children90,91.

Three coping strategies have been identified as essential during stressful experiences: problem-focused coping (i.e., solving the problem), emotion-focused coping (i.e., regulating emotions), and avoidance-oriented coping (i.e., avoiding the problem92,93). Acculturative stress may be linked to more frequent use of problematic parental coping strategies94. Latina mothers who experience increased acculturative stress may experience difficulties activating positive emotion-focused coping strategies, leading them to rely on unsupportive emotional socialization practices. For example, a Latina mother who repeatedly experiences discrimination at work for speaking Spanish during her break may be more likely to react negatively to an anxious or depressed child at home (e.g., by minimizing or dismissing their distress), potentially exacerbating the child’s symptoms95,96. In contrast, a mother who does not experience this type of stress may be more likely to use supportive emotion socialization strategies (e.g., encouraging expression of emotions), thereby modeling adaptive ways of coping with difficult emotions. Although no study to date has examined direct or indirect links between acculturative stress, parental emotion socialization strategies, and emotional and mental wellbeing among Latino youth, indirect evidence from a Latino sample suggests that greater Latino enculturation—the preservation or cultural socialization of one’s culture of origin97—is linked with stronger beliefs about emotional guidance of children and lower youth emotional understanding98. These findings hint at potential differences in emotion socialization practices of Latino families that may be linked with emotional difficulties in youth. Further research is needed to examine the direct and indirect links between acculturative stress, parental emotion socialization strategies, and childhood mental health outcomes.

Societal Factors

Racism and Discrimination

Racial discrimination, a source of acculturative stress, has been extensively studied among Latino families9,38,99. Racial discrimination is related with higher perceived stress, leading to greater depressive symptoms and smoking behaviors among Latino adolescents38. Similarly, Sirin and colleagues found that discrimination stress was significantly and prospectively associated with internalizing symptoms across middle-to-late adolescence100. Furthermore, among Latino adolescents, perceived ethnic discrimination and bicultural stress was associated with higher acculturative stress, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, aggressive behaviors, and rule-breaking behaviors101. In a qualitative study, Cervantes and Cordova found that the most frequently endorsed stressor among Latino youth was perceived discrimination, with one youth expressing that “overcoming discrimination based on nationality” is the hardest part of adapting to a new country22. Multiple Latino youth reported frustration with being stereotyped as “an under achiever” and “not hardworking.” Finally, various youth reported experiencing frequent discrimination from law enforcement, with one participant noting, “cops are so racist to you.” Overall, these studies emphasize the contributions of racism and discrimination to acculturative stress and psychopathology among Latino youth.

Socioeconomic Status and Economic Instability

Socioeconomic status (SES) and economic instability (e.g., experiences of poverty, food insecurity, homelessness, and lack of access to healthcare) are associated with acculturative stress and mental health problems among Latino youth39,102. Potonchnick and colleagues found that 42% of Latino youth reported household food insecurity, which in turn was associated with higher acculturative stress, economic stress, and increased family conflict39. Similarly, a recent systemic review of acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the U.S. reported that economic constraints significantly influenced acculturative stress14,103,104, with higher SES consistently functioning as a protective factor18.

Political Context and Immigration-Related Fears

Recent political debates in the U.S. have placed Latinos at the forefront of discussions regarding the legal rights and acceptance of immigrant populations into the country. The U.S. government’s implementation of strict immigration enforcement policies has led to increased stress in the Latino community105. Fears of deportation, within a highly politicized context, impact the mental health of Latino immigrants, irrespective of their legal status36,105,106. Research with adult samples has found that acculturative stress stemming from fears of deportation has a greater effect on immigrants’ stress levels than other challenges such as learning a new language or adjusting to a new culture.

A recent literature review found that increased risk, fear, and experiences of deportation were associated with greater behavioral changes (i.e., isolation from peers, angry outbursts, difficulties connecting with peers and family members), depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder among Latino youth105. Family deportation vulnerability and fears are also associated with school-related stress among Latino youth107–109. Greater legal vulnerability among Latino families was associated with difficulties in parent-child relationships, the child’s emotional well-being, and overall academic performance107. Similarly, Cardoso and colleagues examined the effect of immigration fear on anxiety among 306 Latino high school students from two study locations (i.e., Harris County, TX and Rhode Island) with distinct political climates surrounding immigration. Immigration enforcement fear emerged as a primary predictor of anxiety and somatic complaints among both groups110, even after accounting for various risk factors (i.e., perceived discrimination, trauma exposure, economic status, and demographic characteristics). Collectively, these findings suggest that fears of deportation and the politicized context surrounding immigration taxes the psychological resources of Latino youth, contributing to increased acculturative stress.

Discussion

This chapter reviewed findings on acculturative stress among Latino youth, concentrating on individual, family/social, and societal factors and their association with acculturative stress and its consequences. Notably, individual factors suggest that girls may be more susceptible to acculturative stress, while the significance of parental support—especially in boys—and age of arrival should be considered24,48–50. Cognitive-affective factors, such as anxiety sensitivity and emotion dysregulation, have shown robust associations with acculturative stress in the adult literature111–114, yet research among children remains unexplored and is an important future avenue63–65,68,69,72,73.

Bilingualism and language brokering may increase acculturative stress in specific situations21,75, but not consistently across all contexts76,79,80. Family/social factors, such as cohesive family functioning (e.g., shared affection, bonding experiences, and feelings of connectedness115) and positive peer relationships, were identified as significant buffers against the adverse effects of acculturative stress18,34. Additionally, societal processes like racial discrimination, economic instability, the sociopolitical context surrounding immigration, and deportation fears were associated with increased acculturative stress severity among Latino youth36,100,102, regardless of the degree of immigration-related tension that exists in different regions of the country110.

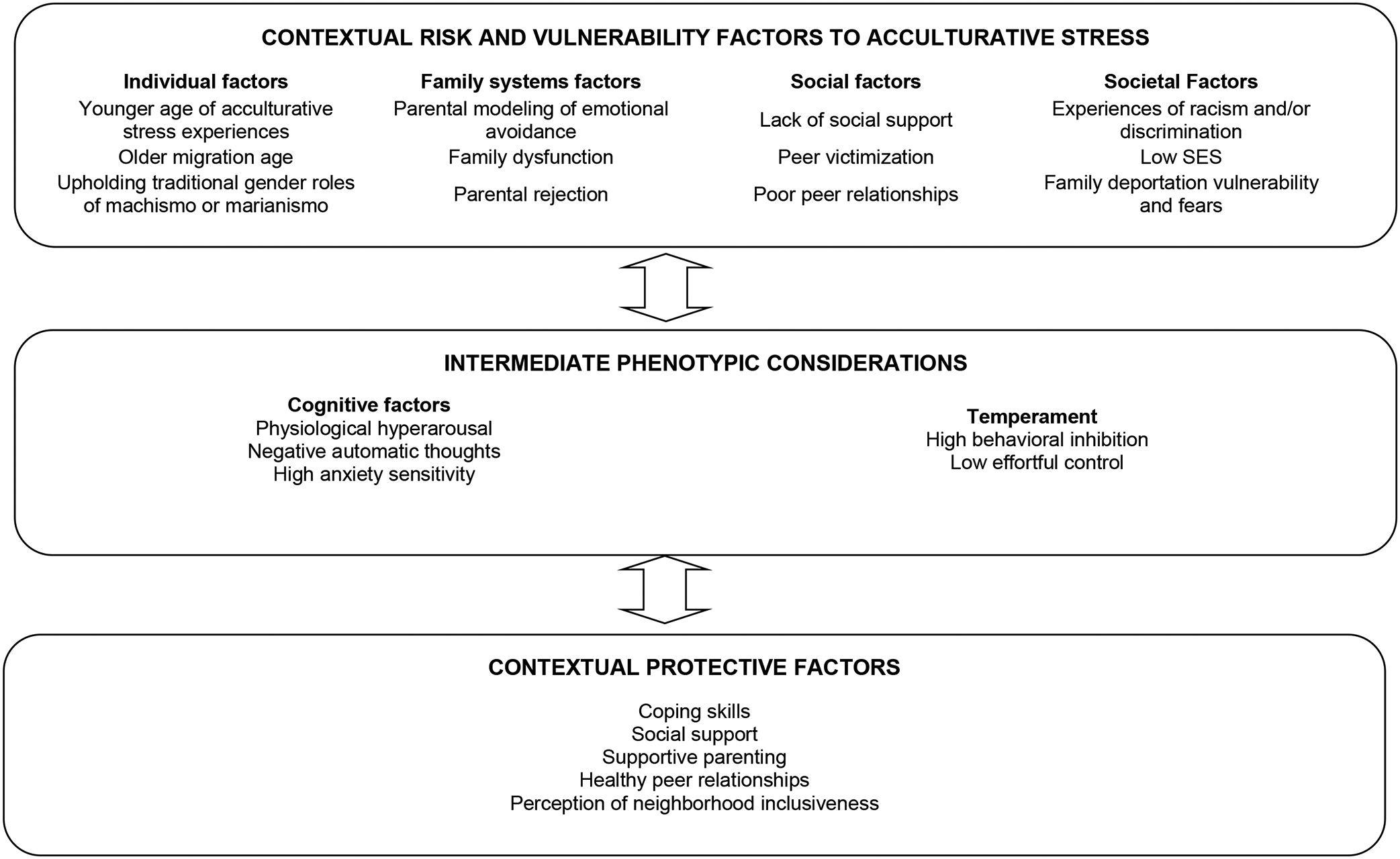

In line with Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of child development20, we propose that acculturative stress is a multilevel process, emerging from the interaction of risk and protective factors across individual, family, social, and societal levels over time. Utilizing this framework enhances the discernment of risks and protective factors associated with acculturative stress among Latino immigrant youth, facilitating the development of personalized approaches and targeted interventions. Illustrated in Figure 1, our proposed bioecological model of acculturative stress for Latino youth functions as a guiding framework, not a universal prescription, recognizing that individual differences in personal experiences, level of acculturation, and family support can make some factors (e.g., language acquisition; deportation fears) more relevant than others for some children. Yet, we believe that a bioecological view of acculturative stress can aid practitioners in gaining a fuller understanding of the stressors impacting Latino youth, informing a well-rounded treatment plan.

Figure 1.

A bioecological model of acculturative stress among Latinos

When working with Latino families, clinicians are encouraged to adopt a culturally sensitive approach for a nuanced understanding of the factors contributing to youths’ acculturative stress and well-being. Utilizing a bioecological framework (Figure 1) to assess acculturative stress in Latino families is recommended. Inquiring about factors such as age of arrival in the U.S., youth preferred language, household language, family SES, and parental involvement can inform where potential risks (or protective factors) may lie. Using a multi-informant approach, clinicians can create a space for open conversations about their cultural values, acculturative experiences, and the youth’s identification with the family’s culture of origin, which can then inform treatment choices. For instance, clinicians can collaborate with Latino families to raise awareness of the acculturation gaps that commonly emerge between foreign-born Latino parents and their U.S.-born children, thereby mitigating the risk of parent-child conflict.

Clinicians are further encouraged to assess Latino youths’ level of acculturative stress at various times throughout the intervention period and use appropriate intervention protocols flexibly, as environmental factors (e.g., deportation fears, discriminatory experiences) may impact treatment adherence. The Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) can aid in assessing and understanding Latino youth’s functioning through a cultural lens. Various questionnaires also can aid acculturation and acculturative stress assessment among Latino youth and families116. For example, the Acculturative Stress Inventory for Children (ASIC117) assesses perceived discrimination and immigration-related stress and only takes approximately 10 minutes to complete. Questionnaires like the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Acculturative Stress Scale (SAFE118) or the Abbreviated Hispanic Stress Inventory-Immigrant Version (Abbreviated HSI-I119) offers a parent’s perspective, while the Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS120) is a self-report measure of overall acculturation experiences. Collectively, these strategies and assessment tools can potentially help clinicians gain a broader and evidence-based understanding of acculturative stress among Latino youth and its role in their mental health.

Conclusion

This chapter synthesized research on acculturative stress among Latino youth, emphasizing relevant factors at individual, family, social, and societal levels. A bioecological model for acculturative stress in Latino youth was offered that considers risk and protective factors across these levels, providing a structured framework for research and clinical endeavors in this area. This framework can improve our efforts to better address the role of acculturative stress in Latino youth’s mental health, aiming to minimize risks and leverage the resilience and protective factors present in Latino youth and their families.

KEY POINTS.

Acculturative stress contributes significantly to mental health problems among Latino youth.

Latino youth may be more susceptible to mental health disparities than their non-Latino White peers due, in part, to acculturative stress.

There are individual, family/social, and societal processes that contribute to or mitigate acculturative stress in Latino youth.

A bioecological model can serve as a useful framework for understanding acculturative stress in Latino youth and help clinicians and providers working with this population.

SYNOPSIS.

Acculturative stress—the psychosocial strain experienced by immigrants in response to challenging events when adapting to a new culture – is a significant predictor of mental health outcomes among immigrant populations. This chapter synthesizes research on acculturative stress among Latino youth, emphasizing relevant factors at individual, family, social, and societal levels. A bioecological model for acculturative stress in Latino youth is proposed that considers risk and protective factors across these levels, providing a structured framework for research and clinical endeavors in this area. This framework can potentially improve our efforts to better address the role of acculturative stress in Latino youths’ mental health, aiming to minimize risks and leverage the resilience and protective factors present in Latino youths and their families. The chapter concludes with recommendations to providers on how to assess acculturative stress in Latino families from a bioecological perspective and how to integrate this information into the formulation of an informed treatment plan.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This chapter was supported in part by grant 1K23AA025920-01A1 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bureau UC. Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. Census.gov. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html

- 2.Patten E The Nation’s Latino Population Is Defined by Its Youth. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. Published April 20, 2016. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110:104699. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasserman AM, Crockett LJ, Temmen CD, Carlo G. Bicultural stress and internalizing symptoms among U.S. Latinx youth: The moderating role of peer and parent support. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2021;27(4):769–780. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutrick K, Clark R, Nuño VL, Bauman S, Carvajal S. Latinx bullying and depression in children and youth: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01383-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzmán A, Koons A, Postolache TT. Suicidal behavior in Latinos: focus on the youth. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2009;21(4):431–439. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2009.21.4.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas SM, Calderon V, Beam CR, Cespedes-Knadle Y, Huey SJ. Worse for girls?: Gender differences in discrimination as a predictor of suicidality among Latinx youth. J Adolesc. 2021;88:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(5):801–816. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9128-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer MA, Velez MG, Rhodes SD, Linton JM. Discrimination against Mixed-Status Families and its Health Impact on Latino Children. J Appl Res Child Informing Policy Child Risk. 2018;10(1):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargas ED, Ybarra VD. U.S. Citizen Children of Undocumented Parents: The Link Between State Immigration Policy and the Health of Latino Children. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(4):913–920. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0463-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 1997;46(1):5–34. doi: 10.1080/026999497378467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bui Q, Doescher M, Takeuchi D, Taylor V. Immigration, acculturation and chronic back and neck problems among Latino-Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(2):194–201. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9371-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cano MÁ, Sánchez M, De La Rosa M, et al. Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the roles of bicultural self-efficacy and acculturation. Addict Behav. 2020;108:106442. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2000;6(2):134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus RS. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. McGraw-Hill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell M, Doucette DW. Latino Acculturative Stress Implications, Psychotherapeutic Processes, and Group Therapy. Published online 2012.

- 17.Torres CA, Crowther MR, Brodsky S. Addressing acculturative stress in psychotherapy: A case study of a latino man overcoming cultural conflicts and stress related to language use. Clin Case Stud. 2017;16(3):187–199. doi: 10.1177/1534650116686180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekteshi V, Kang SW. Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Ethn Health. 2020;25(6):897–914. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1469733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constructs Rudmin F., measurements and models of acculturation and acculturative stress. Int J Intercult Relat. 2009;33(2):106–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, Volume 1, 5th Ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998:993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth J, Huerta C, Thomas B. The role of bilingualism in Latino youth experiences of acculturation stress when living in an emerging Latino community. Qual Soc Work. 2021;20(4):1059–1077. doi: 10.1177/1473325020923012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cervantes RC, Cordova D. Life experiences of Hispanic adolescents: Developmental and language considerations in acculturation stress. J Community Psychol. 2011;39(3):336–352. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez C, Gudiño OG. Acculturative Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Latinx Youth: The Role of Behavioral Inhibition, Cultural Values, and Active Coping. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2023;54(4):1178–1189. doi: 10.1007/s10578-022-01326-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roche C, Kuperminc GP. Acculturative Stress and School Belonging Among Latino Youth. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2012;34(1):61–76. doi: 10.1177/0739986311430084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlaudt V, Suarez-Morales L, Black R. Exploring the Relationship of Acculturative Stress and Anxiety Symptoms in Latino Youth. Child Youth Care Forum. 2021;50. doi: 10.1007/s10566-020-09575-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez-Orozco C Afterword: Understanding and Serving the Children of Immigrants. Harv Educ Rev. 2009;71(3):579–590. doi: 10.17763/haer.71.3.x40q180654123382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor ZE, Jones BL, Anaya LY, Evich CD. Effortful control as a mediator between contextual stressors and adjustment in Midwestern Latino youth. J Lat Psychol. 2018;6(3):248–257. doi: 10.1037/lat0000091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Gonzales-Backen MA. The association between acculturative stress and rule-breaking behaviors among Latinx adolescents in rural areas: A moderated mediation analysis. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. Published online 2023:No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brietzke M, Perreira K. Stress and Coping: Latino Youth Coming of Age in a New Latino Destination. J Adolesc Res. 2017;32(4):407–432. doi: 10.1177/0743558416637915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buehler C Family processes and children’s and adolescents’ well-being. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):145–174. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fosco GM, Caruthers AS, Dishion TJ. A Six-Year Predictive Test of Adolescent Family Relationship Quality and Effortful Control Pathways to Emerging Adult Social and Emotional Health. J Fam Psychol JFP J Div Fam Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 43. 2012;26(4):565–575. doi: 10.1037/a0028873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, et al. Latino Parent Acculturation Stress: Longitudinal Effects on Family Functioning and Youth Emotional and Behavioral Health. J Fam Psychol JFP J Div Fam Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 43. 2016;30(8):966–976. doi: 10.1037/fam0000223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pimentel EC, Delbasso CA, Kuperminc GP. Acculturative Stress and Psychological Distress Among Latinx Youth: Moderating Role of Family Cohesion and Conflict. J Early Adolesc. 2023;43(8):1071–1096. doi: 10.1177/02724316221142243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potochnick SR, Perreira KM. Depression and Anxiety among First-Generation Immigrant Latino Youth: Key Correlates and Implications for Future Research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(7):470. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4ce24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umaña-Taylor AJ, Hill NE. Ethnic–racial socialization in the family: A decade’s advance on precursors and outcomes. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):244–271. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, Wiesner M. Acculturative Stress Among Documented and Undocumented Latino Immigrants in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32(3):362–384. doi: 10.1177/0739986310373210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coll CG, Patton F, Marks AK, et al. Understanding the immigrant paradox in youth: Developmental and contextual considerations. In: Realizing the Potential of Immigrant Youth. The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence. Cambridge University Press; 2012:159–180. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139094696.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB. Ethnic Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Family Conflict as Predictors of Depressive Symptoms and Cigarette Smoking Among Latina/o Youth: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(10):1984–1997. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0339-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potochnick S, Perreira KM, Bravin JI, et al. Food Insecurity Among Hispanic/Latino Youth: Who Is at Risk and What Are the Health Correlates? J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2019;64(5):631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia C, Zhang L, Holt K, Hardeman R, Peterson B. Latina Adolescent Sleep and Mood: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Pilot Study. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs Off Publ Assoc Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurses Inc. 2014;27(3):132–141. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D. Acculturation, Enculturation, and Symptoms of Depression in Hispanic Youth: The Roles of Gender, Hispanic Cultural Values, and Family Functioning. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(10):1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varela RE, Niditch LA, Hensley-Maloney L, Moore KW, Creveling CC, Jones KM. Culture specific influences on anxiety in Latino youth. Child Youth Care Forum. 2019;48(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10566-018-9476-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varela RE, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Biggs BK, Luis TM. Parenting strategies and socio-cultural influences in childhood anxiety: Mexican, Latin American descent, and European American families. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(5):609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cahill KM, Updegraff KA, Causadias JM, Korous KM. Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(9):947–985. doi: 10.1037/bul0000336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdivieso-Mora E, Peet CL, Garnier-Villarreal M, Salazar-Villanea M, Johnson DK. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Familism and Mental Health Outcomes in Latino Population. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1632. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gill RM, Vasquez CI. The Maria Paradox. Putnam Adult; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castillo LG, Walker JEOY, Zamboanga BL, et al. Gender Matters: The Influence of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress on Latino College Student Depressive Symptomatology. J Lat Psychol. 2015;3(1):40–55. doi: 10.1037/lat0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Streit C, Davis AN, Carlo G. Gender-Specific Patterns of Relations among Acculturative Stress, Family Processes, and Prosocial Behaviors in Latinx Youth. J Genet Psychol. 2024;185(1):50–64. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2023.2254812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smokowski PR, Rose RA, Bacallao M. Influence of risk factors and cultural assets on Latino adolescents’ trajectories of self-esteem and internalizing symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2010;41(2):133–155. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0157-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sirin SR, Ryce P, Gupta T, Rogers-Sirin L. The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(4):736–748. doi: 10.1037/a0028398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, Vol. 3, 5th Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998:105–176. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slagt M, Dubas JS, Deković M, van Aken MAG. Differences in sensitivity to parenting depending on child temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2016;142(10):1068–1110. doi: 10.1037/bul0000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Domènech JM. Developmental trajectories of callous-unemotional traits, anxiety and oppositionality in 3–7 year-old children in the general population. Personal Individ Differ. 2017;111:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim-Spoon J, Deater-Deckard K, Holmes C, Lee J, Chiu P, King-Casas B. Behavioral and Neural Inhibitory Control Moderates the Effects of Reward Sensitivity on Adolescent Substance Use. Neuropsychologia. 2016;91:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan SM, Ollendick TH. The Interaction Between Child Behavioral Inhibition and Parenting Behaviors: Effects on Internalizing and Externalizing Symptomology. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2018;21(3):320–339. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0254-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevens J, Quittner AL, Zuckerman JB, Moore S. Behavioral inhibition, self-regulation of motivation, and working memory in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Dev Neuropsychol. 2002;21(2):117–139. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2102_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang FL, Galán CA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Wilson MN, Shaw DS. Evidence for two genetically-distinct pathways to co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence characterized by negative affectivity or behavioral inhibition. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129(6):633–645. doi: 10.1037/abn0000525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harwood RL, Miller JG, Irizarry NL. Culture and Attachment: Perceptions of the Child in Context. Culture and Human Development: A Guilford Series Guilford Press, 72 Spring Street, New York, NY 10012; phone: 212-431-9800; fax: 212-966-6708 (hardcover: ISBN-0-80862-877–6, $39; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider A, Gudiño OG. Predicting Avoidance Symptoms in U.S. Latino Youth Exposed to Community Violence: The Role of Cultural Values and Behavioral Inhibition. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(4):509–517. doi: 10.1002/jts.22313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press; 1976:356. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beck AT, Haigh EAP. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jardin C, Mayorga NA, Bakhshaie J, et al. Clarifying the relation of acculturative stress and anxiety/depressive symptoms: The role of anxiety sensitivity among Hispanic college students. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2018;24(2):221–230. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mayorga NA, Garey L, Viana A, Cardoso JB, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Psychological Distress and Physical Health Symptoms in the Latinx Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Role of Anxiety Sensitivity. Cogn Ther Res. 2022;46(1):20–30. doi: 10.1007/s10608-021-10243-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Viana AG, Bakhshaie J, Raines EM, et al. Anxiety sensitivity and acculturative stress facets among Latinx in primary care. Stigma Health. 2020;5(1):22–28. doi: 10.1037/sah0000171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuohy K, Suarez-Morales L. The Effects of Acculturation Stress, Life Events, and Daily Hassles on Automatic Thoughts in Latinx Children. Fac Proc Present Speeches Lect. Published online November 19, 2020. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cps_facpresentations/4741 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sandin B, Sánchez-Arribas C, Chorot P, Valiente RM. Anxiety sensitivity, catastrophic misinterpretations and panic self-efficacy in the prediction of panic disorder severity: Towards a tripartite cognitive model of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2015;67:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ponting C, Lee SS, Escovar EL, et al. Family factors mediate discrimination related stress and externalizing symptoms in rural Latino adolescents. J Adolesc. 2018;69:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smokowski PR, Cotter KL, Robertson CIB, Guo S. Anxiety and aggression in rural youth: baseline results from the rural adaptation project. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44(4):479–492. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0342-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, Phipps S. Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(4):403–415. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paulus FW, Ohmann S, Möhler E, Plener P, Popow C. Emotional Dysregulation in Children and Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders. A Narrative Review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:628252. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Archuleta AJ. Newcomers: The contribution of social and psychological well-being on emotion regulation among first-generation acculturating Latino youth in the Southern United States. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2015;32(3):281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10560-014-0370-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hong YY, Morris MW, Chiu CY, Benet-Martínez V. Multicultural minds. A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. Am Psychol. 2000;55(7):709–720. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.7.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kam JA, Lazarevic V. The stressful (and not so stressful) nature of language brokering: identifying when brokering functions as a cultural stressor for Latino immigrant children in early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(12):1994–2011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0061-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kam JA, Guntzviller LM, Pines R. Language brokering, prosocial capacities, and intercultural communication apprehension among Latina mothers and their adolescent children. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2017;48(2):168–183. doi: 10.1177/0022022116680480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen Y, Seo E, Jiles AI, Zheng Y, Wang Y. Language brokering and immigrant-origin youth’s well-being: A meta-analytic review. Am Psychol. 2022;77(8):921–939. doi: 10.1037/amp0001035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weisskirch RS, Alva SA. Language brokering and the acculturation of Latino children. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2002;24(3):369–378. doi: 10.1177/0739986302024003007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marsiglia FF, Booth JM, Baldwin A, Ayers S. Acculturation and Life Satisfaction Among Immigrant Mexican Adults. Adv Soc Work. 2013;14(1):49–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30(2):135–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1010389607319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hurwich-Reiss E, Gudiño OG. Acculturation stress and conduct problems among Latino adolescents: The impact of family factors. J Lat Psychol. 2016;4(4):218–231. doi: 10.1037/lat0000052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu S, Marsiglia FF, Ayers S, Cutrín O, Vega-López S. Familial Acculturative Stress and Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors in Latinx Immigrant Families of the Southwest. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(6):1193–1199. doi: 10.1007/s10903-020-01084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bierman KL. Peer Rejection: Developmental Processes and Intervention Strategies. Guilford Press; 2004:xx, 299. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brumariu LE, Obsuth I, Lyons-Ruth K. Quality of attachment relationships and peer relationship dysfunction among late adolescents with and without anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hartup WW. Peer relationships. In: Hetheringtong EM, ed. Handbook of Child Psychology. Wiley; 1983:103–196. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Myers HF, Morris JK, Cardoza D. Family or friends: Who plays a greater supportive role for Latino college students? Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9(3):236–250. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Katsiaficas D, Suárez-Orozco C, Sirin SR, Gupta T. Mediators of the relationship between acculturative stress and internalization symptoms for immigrant origin youth. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(1):27–37. doi: 10.1037/a0031094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental Socialization of Emotion. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(4):241–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Dev. 1996;67(5):2227–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keenan K Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2000;7(4):418–434. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.7.4.418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. Emotion regulation and understanding: implications for child psychopathology and therapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22(2):189–222. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00087-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Endler NS, Parker JD. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(5):844–854. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation across National Contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006:xxxl, 308. doi: 10.4324/9780415963619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Driscoll MW, Torres L. Acculturative Stress and Latino Depression: The Mediating Role of Behavioral and Cognitive Resources. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(4):373. doi: 10.1037/a0032821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pintar Breen AI, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Kahana-Kalman R. Latina mothers’ emotion socialization and their children’s emotion knowledge. Infant Child Dev. 2018;27(3):e2077. doi: 10.1002/icd.2077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yoon E, Chang CT, Kim S, et al. A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60(1):15–30. doi: 10.1037/a0030652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Perez Rivera MB, Dunsmore JC. Mothers’ acculturation and beliefs about emotions, mother-child emotion discourse, and children’s emotion understanding in Latino families. Early Educ Dev. 2011;22(2):324–354. doi: 10.1080/10409281003702000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ayón C Talking to Latino children about race, inequality, and discrimination: Raising families in an anti-immigrant political environment. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2016;7(3):449–477. doi: 10.1086/686929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sirin SR, Rogers-Sirin L, Cressen J, Gupta T, Ahmed SF, Novoa AD. Discrimination-related stress effects on the development of internalizing symptoms among Latino adolescents. Child Dev. 2015;86(3):709–725. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, et al. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. J Adolesc. 2015;42:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ríos-Salas V, Larson A. Perceived discrimination, socioeconomic status, and mental health among Latino adolescents in US immigrant families. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;56:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Negy C, Schwartz S, Reig-Ferrer A. Violated expectations and acculturative stress among U.S. Hispanic immigrants. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2009;15(3):255–264. doi: 10.1037/a0015109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vidal de Haymes M, Martone J, Muñoz L, Grossman S. Family Cohesion and Social Support: Protective Factors for Acculturation Stress Among Low-Acculturated Mexican Migrants. J Poverty. 2011;15(4):403–426. doi: 10.1080/10875549.2011.615608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lovato K, Lopez C, Karimli L, Abrams L. The impact of deportation-related family separations on the well-being of Latinx children and youth: A review of the literature. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;95. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alegría M, Álvarez K, DiMarzio K. Immigration and Mental Health. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4(2):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s40471-017-0111-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brabeck K, Xu Q. The impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children and families: A quantitative exploration. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32(3):341–361. doi: 10.1177/0739986310374053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dreby J The Burden of Deportation on Children in Mexican Immigrant Families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74(4):829–845. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dreby J U.S. immigration policy and family separation: The consequences for children’s well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cardoso JB, Brabeck K, Capps R, et al. Immigration enforcement fear and anxiety in Latinx high school students: The indirect effect of perceived discrimination. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(5):961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bakhshaie J, Hanna AE, Viana AG, et al. Acculturative stress and mental health among economically disadvantaged Spanish-speaking Latinos in primary care: The role of anxiety sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Davis AN, Carlo G, Zamboanga BL, et al. The Roles of Familism and Emotion Reappraisal in the Relations Between Acculturative Stress and Prosocial Behaviors in Latino/a College Students. J Lat Psychol. 2018;6(3):175–189. doi: 10.1037/lat0000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lugo-Candelas CI, Harvey EA, Breaux RP, Herbert SD. Ethnic differences in the relation between parental emotion socialization and mental health in emerging adults. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(3):922–938. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0266-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zvolensky MJ, Jardin C, Rogers AH, et al. Anxiety sensitivity and acculturative stress among trauma exposed Latinx young adults. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2018;24(4):470–476. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Olson DH, Waldvogel L, Schlieff M. Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems: An Update. J Fam Theory Rev. 2019;11(2):199–211. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Aggarwal NK, Lewis-Fernández R. An Introduction to the Cultural Formulation Interview. Focus Am Psychiatr Publ. 2020;18(1):77–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.18103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Suarez-Morales L, Dillon FR, Szapocznik J. Validation of the Acculturative Stress Inventory for Children. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13(3):216–224. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mena FJ, Padilla AM, Maldonado M. Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):207–225. doi: 10.1177/07399863870092006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Walker MS, Fisher EB. Evaluating an Abbreviated Version of the Hispanic Stress Inventory for Immigrants. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28(4):498–515. doi: 10.1177/0739986306291740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zea MC, Asner-Self KK, Birman D, Buki LP. The Abbreviated Multidimentional Acculturation Scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9(2):107–126. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]