Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with different subtypes of pathogenesis. Insufficient research on the subtypes of ADHD has limited the effectiveness of therapeutic methods.

Methods

This study used resting-state functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to record hemodynamic signals in 34 children with ADHD-combined subtype (ADHD-C), 52 children with ADHD-inattentive subtype (ADHD-I), and 24 healthy controls (HCs). The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) and the functional connectivity (FC) analysis were conducted for all subjects.

Results

Compared with HCs, the ADHD group exhibited significantly increased ALFF and decreased FC. The ADHD-C group showed significantly higher ALFF in partial brain regions and significantly lower FC between multiple brain regions than participants with ADHD-I. The male group displayed a significant increase in ALFF in some brain regions, while no significant difference was found in FC when compared to the female group.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence to support the subtype classification of ADHD-I and ADHD-C, and the combined analysis of ALFF and FC has the potential to be a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of ADHD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-024-06350-6.

Keywords: Subtypes of ADHD, Functional near-infrared spectroscopy, Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation, Functional connectivity

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that affects approximately 5% of children and adolescents worldwide [1, 2]. It is characterized by persistent difficulty maintaining attention, hyperactivity, and impulsive behavior [3], which will further increase the risk of other psychiatric disorders, educational and occupational failure, accidents, criminality, social disability, and addictions [4, 5]. The diagnosis of ADHD is usually executed by the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) and clinical observation [6]. Therefore, research exploring proper and effective biomarkers for the diagnosis of ADHD is of great significance.

Noninvasive functional neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [7] and Electroencephalogram (EEG) [8], provide an idea to solve this difficulty. These techniques can quantify the differences in functional brain signals between ADHD patients and healthy controls (HCs) [9–12]. However, fMRI is confined by the large size of instruments, prohibiting users from moving freely. EEG is confined by the sensitivity to motion, making the raw data complicated to process. Both of these factors influence the accuracy and reliability of studies on ADHD for the symptoms of uncontrolled hyperactivity. In contrast, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a noninvasive optical imaging technique that measures cerebral hemodynamic changes associated with functional brain activity [13]. It can tolerate head movements [14–17] and is particularly more suitable for ADHD research [18–20].

fNIRS studies can be divided into task-state and resting-state experiments [18–21]. Task-state studies have used tasks related to response inhibition [22], working memory [23], attention [24], and emotion regulation [25] to explore the neural abnormalities underlying different cognitive demands in ADHD patients [26]. Monden et al.. demonstrated that the spatial distribution and amplitude of the hemodynamic response were associated with inhibition-related right prefrontal dysfunction [27]. Ehlis et al.. found that compared to the HC group, ADHD patients showed reduced task-related increases in the concentration of oxyhemoglobin (HbO) in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VPC) [23]. Ichikawa et al.. found that ADHD children showed an increased concentration of HbO for happy faces but not for angry faces, while HCs showed increased HbO for both faces [28]. These task-state fNIRS studies indicated the difference between ADHD patients and HCs in various aspects.

The results of task-state studies are often influenced by experimental paradigms and control conditions. In contrast, resting-state studies are easier to conduct and more participant-friendly. Moreover, resting-state studies more closely approximate the brain’s natural working state [26]. Although the reliability and reproducibility of resting-state fNIRS (rs-fNIRS) have been confirmed in a variety of application scenarios, there are relatively few rs-fNIRS studies on spontaneous and intrinsic neural activity in ADHD patients [29–35]. Most rs-fNIRS studies extracted functional connectivity (FC) as the primary feature to distinguish patients from HCs. FC can reveal the abnormal correlation between two brain regions but cannot detect functional alternation of a specific brain region. The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) characterizes the strength of spontaneous activity in specific brain regions. It has been applied to many other functional neuroimaging techniques [36–39]. For ADHD, rs-fNIRS research is inadequate, and whether FC and ALFF analysis can be applied to ADHD patients needs further verification.

Therefore, this study aims to use fNIRS to present the difference in ALFF and FC between ADHD patients and HCs during the resting state. Meanwhile, ADHD can be categorized into three groups: the predominantly inattentive subtype (ADHD-I), the hyperactive-impulsive subtype (ADHD-HI), and the combined subtype (ADHD-C). Considering that few studies have considered sex and different subtypes of ADHD [22, 40–42], different subtypes (ADHD-C, ADHD-I) and sexes were also taken into account to obtain full insight into the difference between ADHD patients and HCs. ADHD-HI was neglected in this study due to its low prevalence.

Materials and methods

Participants

Patients with ADHD (n = 90) were recruited from the clinics of Peking University Sixth Hospital. The diagnosis of ADHD and subtypes was preliminarily determined by a child psychiatrist with the title of attending physician or above using the Clinical Diagnostic Interview Scale (CDIS) [43] according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV) and further verified through semistructured clinical interviews with children and parents. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meeting the diagnostic criteria for ADHD in DSM-IV; (2) intelligence quotient (IQ) ≥ 80, using the Chinese-Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (C-WISC); (3) aged 6 to 13 years old; and (4) not taking any central stimulants, atomoxetine, antipsychotic drugs, or antidepressants. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with child and adolescent schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, mental retardation, substance use disorder, depressive disorder, and anxiety disorder. (2) Patients with obvious physical and neurologic abnormalities. This exclusion criterion is implemented to minimize the impact of other psychiatric disorders on the brain function imaging associated with ADHD. Among all recruited patients, 34 were diagnosed with ADHD-C, and 52 were diagnosed with ADHD-I.

The HCs (n = 24) were recruited from ordinary primary and secondary schools nearby. The normality was preliminarily screened with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) [44] and further determined by a child psychiatrist with the title of attending physician or above.

Data acquisition

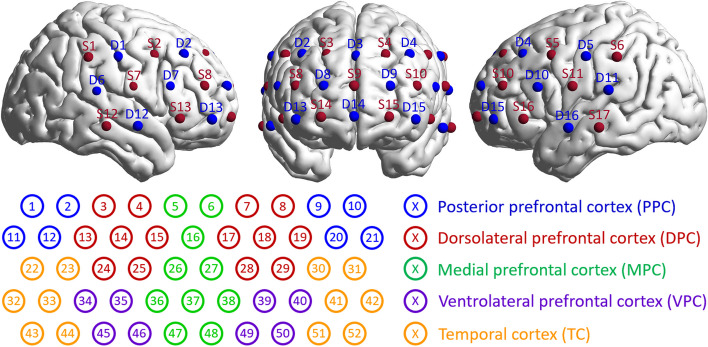

In this study, a multichannel fNIRS system (ETG-4000; Hitachi, Japan) was used to determine the hemodynamic changes in the prefrontal and temporal lobes of the brain during the resting state of the subjects. This equipment adopted two wavelengths of near-infrared light, namely, 695 and 830 nm, and a sampling rate of 10 Hz. Seventeen light sources and 16 detectors were arranged on the subject’s head with adjacent source and detector pairs being 2 cm apart, forming 52 different measurement channels. The probes were positioned on the head according to the international EEG 10–20 system. The middle inferior probe was placed over Frontopolar-prefrontal (Fpz), and the inferior row of probes was oriented in the direction of T3 or T4. The arrangement of fNIRS channels on a brain model is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The arrangement of 17 light sources and 16 detectors on the brain model and the correspondence between 52 channels and regions of interest (ROIs)

During the test, subjects were asked to sit quietly in the chair, keep their head still and their mind blank as much as possible, and avoid changing body posture. The measurement lasted for 8 min, during which the experimenter observed the performance of the subjects and the signal changes in real time and marked the artificial interference signals for data preprocessing.

Data preprocessing

This work exploited the NIRS_KIT, a MATLAB toolbox [45], to preprocess the raw data. NIRS_KIT was applied to convert the original light intensity data to the concentration of HbO based on the modified Beer-Lambert law [46]. Note that the HbO data were chosen for subsequent analyses considering their better signal-to-noise ratio. The polynomial regression model and the temporal derivative distribution (TDDR) method were used to remove the baseline drift and motion artifacts [47]. To remove the low-frequency drift and high-frequency neurophysiological noise, the bandpass filter adopted a frequency of 0.01–0.08 Hz. Data preprocessing was conducted in MATLAB Version R2022a.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

We adopted the ALFF and the FC matrix for every subject. ALFF was obtained by summing and averaging the square root of the signal power spectrum, revealing the strength of spontaneous activity in certain brain areas [39]. FC strength was evaluated by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between two signals from two channels, with a larger FC absolute value representing stronger synchronization of brain activity between two brain regions (both positive correlation and negative correlation). A symmetrical FC matrix was formed by executing the Pearson correlation analysis for all channels.

The averages of ALFFs and FC matrixes from different groups (ADHD, ADHD-C, ADHD-I, male, female, and HCs) were calculated to characterize the average level of each group. A one-sample T-test was performed to examine the consistency of the data in each group. To reveal the significant differences between groups, a two-sample T-test was executed. For channels with significant differences, the average value of their Fourier spectra was calculated to show these differences. By perceiving several channels as one node, as Fig. 1 shows, and averaging their FC values, the 52*52 FC matrix was switched to a 9*9 matrix to analyze the FC between certain brain regions further.

Results

Brain activation performance

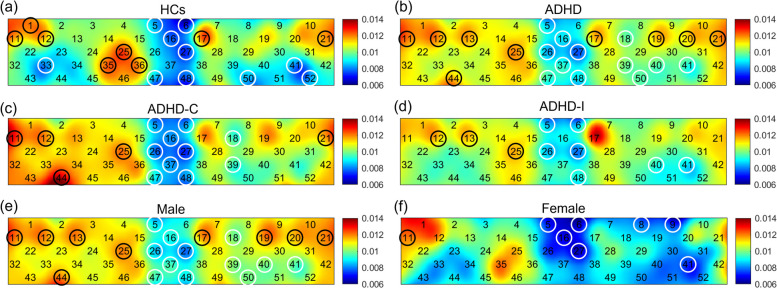

Brain activation performance was analyzed among the subject groups. Figure 2 shows the average ALFF value of all channels in the HC, ADHD, ADHD-C, ADHD-I, male, and female groups. A one-sample T-test indicated the significance and consistency of each circled channel and nine ROIs. The results are summarized in appendix A. It was found from the map that in the HCs (Fig. 2a), the medial prefrontal cortex (MPC) and the left and right temporal cortex (TC) exhibited significantly lower ALFF values. The left and right posterior prefrontal cortex (PPC) exhibited significantly higher ALFF values. In contrast, for all ADHD patients (Fig. 2b), the average ALFF value of the left and right TC lost the significance of the lower ALFF value, and the left VPC exhibited a significantly lower ALFF value. The right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DPC) had a significantly higher ALFF value. In the ADHD-C patients (Fig. 2c), the MPC and the left VPC exhibited significantly lower ALFF values. The right PPC and the right TC exhibited significantly higher ALFF values. In contrast, in the ADHD-I patients (Fig. 2d), the ALFF value of the right TC lost the significance of the higher ALFF value, and the right DPC gained significance. In the male patients (Fig. 2e), the MPC and the left VPC exhibited significantly lower ALFF values. The left and right PPC exhibited significantly higher ALFF values. In contrast, in the female patients (Fig. 2f), the left TC also exhibited significantly lower ALFF values, and the left PPC lost the significance of higher ALFF values.

Fig. 2.

The activation pattern of 52 channels in HCs (a), all ADHD patients (b), the ADHD-C subtype (c), the ADHD-I subtype (d), male patients (e), and female patients (f). The color bar indicates different ALFF values. The circles highlight the channels with significantly higher (black) and lower ALFF values (white), respectively, in the one-sample T-test (p < 0.05)

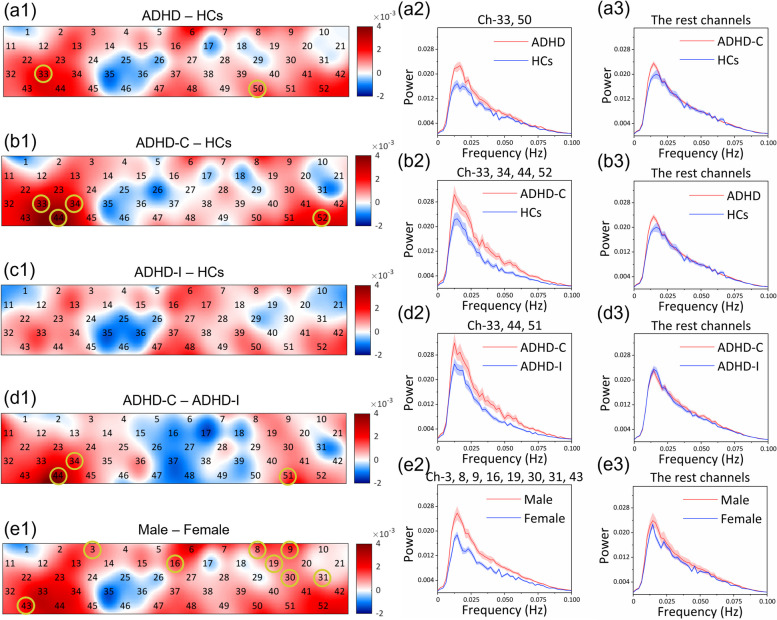

To better demonstrate the differences, the subtraction of ALFF values between groups and the average Fourier spectra of hemodynamic signals are visualized in Fig. 3. Channels indicating significant differences in the two-sample T-test are circled. It was found that all ADHD patients had increased ALFF values compared with HCs in most brain areas, and the difference in the right TC (Ch-33: p = 0.021) and the left VPC (Ch-50: p = 0.048) was significant (Fig. 3(a1)). The average Fourier spectra were separated Ch-33, 50 (Fig. 3(a2)) and fitted in the remaining channels (Fig. 3(a3)). In ADHD-C patients (Fig. 3(b1)), the left and right TC (Ch-33: p = 0.009, Ch-44: p = 0.008, and Ch-52: p = 0.039) and the right VPC (Ch-34: p = 0.023) were significantly increased in ALFF value in comparison to HCs. The average Fourier spectra were separated Ch-33, 34, 44, 52 (Fig. 3(b2)) and fitted in the remaining channels (Fig. 3(b3)). No brain region in ADHD-I patients (Fig. 3(c1)) exhibited significance when compared with HCs. The left and right TC (Ch-44: p = 0.001, and Ch-51: p = 0.043) and the right VPC (Ch-34: p = 0.042) in ADHD-C patients had significantly higher ALFF values than those in ADHD-I patients (Fig. 3(d1)). The average Fourier spectra were separated Ch-34, 44, 51 (Fig. 3(d2)) and fitted in the remaining channels (Fig. 3(d3)). Compared with female patients, the left and right DPC (Ch-3: p = 0.024, Ch-8: p = 0.018, and Ch-19: p = 0.005), the MPC (Ch-16: p = 0.030), and the left and right TC (Ch-30: p = 0.020, Ch-31: p = 0.024, and Ch-43: p = 0.024) in male patients were significantly increased in the ALFF value (Fig. 3(e1)). The average Fourier spectra were separated Ch-3, 8, 16, 19, 30, 31, 43 (Fig. 3(e2)) and fitted in the remaining channels (Fig. 3(e3)).

Fig. 3.

(a1-e1) The subtraction of ALFF values in each channel between groups. The color bar indicates different ALFF subtractions. The circles highlight the channels with significant differences in the two-sample T-test between groups (p < 0.05). (a2, b2, d2, e2) The average Fourier spectra of the channels with significant differences; the large spectrum value indicates strong activation. (a3, b3, d3, e3) The average Fourier spectra of the channels with no significant differences. The error bars were generated from the standard error of each group

FC performance

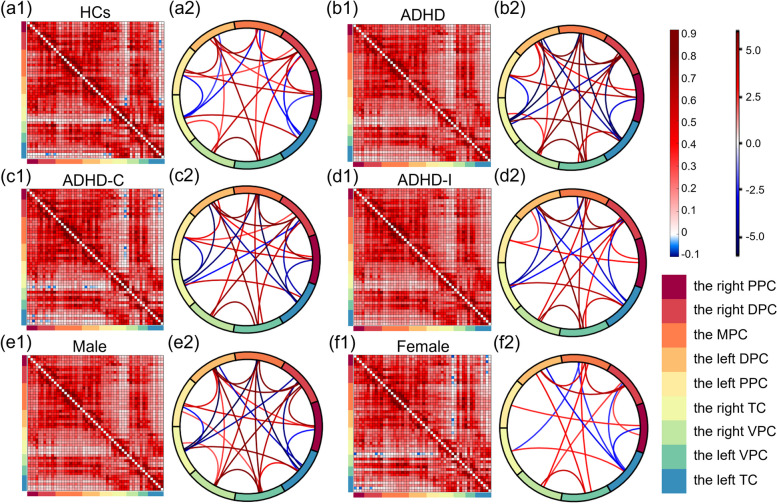

Figure 4 shows the FC distribution of HCs, ADHD patients, the ADHD-C subtype, the ADHD-I subtype, male patients, and female patients in the six square diagrams, with T values visualized in six circle diagrams to show the significance of each FC value. In HCs (Fig. 4(a1-a2)), the FC values between the right DPC and the left TC and between the left PPC and the right TC were negative and significantly lower. Significantly higher FC values were mainly found in the left and right DPC with other brain regions, and all homotopic FC values were significantly higher. In contrast, in ADHD patients (Fig. 4(b1-b2)), no significant negative FC was found. In ADHD-C patients (Fig. 4(c1-c2)), the strong FC between the right TC and the right VPC and between the left VPC and the left TC lost significance, while the FC distribution for other brain regions was similar to that of ADHD patients. The left PPC had significant negative FC with the right TC, and the left TC had significant negative FC with the right PPC and the right DPC. In ADHD-I patients (Fig. 4(d1-d2)), the higher FC values between the left VPC and the left TC and between the right PPC and the left DPC were not significant compared with ADHD-C patients. The FC distribution of male patients (Fig. 4(e1-e2)) was similar to that of ADHD patients. In female patients (Fig. 4(f1-f2)), the numbers of significant FC values were much lower. The left TC had significant negative FC with the right PPC and the right DPC.

Fig. 4.

The FC distribution of each group. Nine ROIs were visualized with nine different colors. (a1-f1) The square diagrams show the average FC matrixes of each group. Their horizontal and vertical coordinates referred to the fifty-two channels, the order of which was consistent with the ROIs shown in Fig. 1(b). Pixels with different colors indicate different FC values between two channels, as shown in the first color bar. (a2-f2) The circle diagrams visualized the T values in the one-sample T-test, which was executed in each group to analyze the significance of each FC value. Wires with different colors indicate different T values, as the second color bar shows. Only partial T values that indicated significance in the one-sample T-test (p < 0.05) were visualized

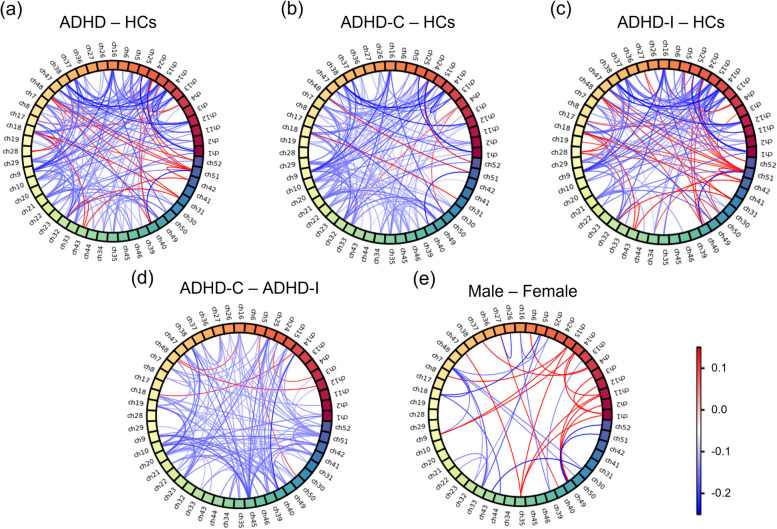

To better demonstrate the differences, the subtraction of FC values with significant differences between brain areas is visualized in Fig. 5. People with ADHD had significantly decreased FC values between most channels, such as the PPC (Ch-1, Ch-2, Ch-11, and Ch-12) and the DPC (Ch-13, Ch-14, Ch-15, Ch-24, and Ch-25), compared with HCs. Nevertheless, the FC values between a few channels, such as the TC (Ch-32, Ch-43, Ch-31, Ch-42, Ch-51, and Ch-52) and the DPC (Ch-15, Ch-24, Ch-25, Ch-18, and Ch-28), were significantly larger than those of HCs (Fig. 5(a)). Compared with HCs, ADHD-C patients (Fig. 5(b)) had significantly decreased FC values in most channels, while in ADHD-I patients (Fig. 5(c)), some FC values between the left TC (Ch-42, Ch-51) and the DPC and the MPC were significantly increased, and some FC values between the right DPC (Ch-13, Ch-14, Ch-15, Ch-24, and Ch-25) and the MPC and the right PPC were significantly decreased. Most FC values in ADHD-C patients were significantly lower than those in ADHD-I patients (Fig. 5(d)). There were few channels with significant differences between male and female patients (Fig. 6(e)).

Fig. 5.

The subtraction of FC values between groups. Fifty-two channels were visualized with fifty-two different colors, and the order was consistent with the ROIs, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Each wire indicates the subtraction of the FC value between two channels. Only partial subtractions of FC values that indicated a significant difference in the two-sample T-test (p < 0.05) would be visualized

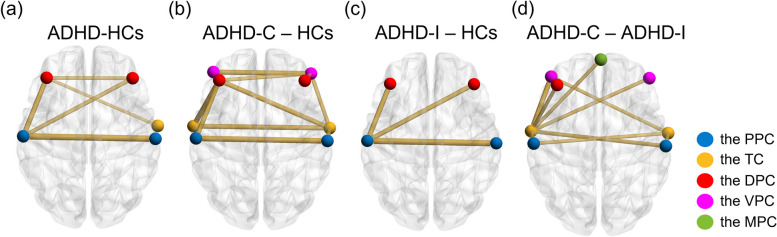

Fig. 6.

The subtraction of FC values between groups. The spheres with different colors indicate different brain regions. The lines with different thicknesses indicate the subtractions of FC values between two brain regions. Thicker and thinner lines indicate higher and lower absolute subtraction of FC values, respectively. Only partial subtractions of FC values that indicated significant differences in the two-sample T-test (p < 0.05) would be visualized. There is no map showing the subtraction between the Male and Female group because no significant difference was found between the two groups. The subtraction of FC values visualized in these diagrams were all negative

Figure 6 visualizes the subtraction of FC values that indicated significant differences in the two-sample T-test (p < 0.05) between groups. Notably, the FC values in Fig. 6 were all negative. In ADHD patients (Fig. 6(a)), the FC values between the left and right PPC, between the left and right DPC, between the left PPC and the left and right DPC, and between the left DPC and the right TC were significantly decreased in comparison with HCs. In ADHD-C patients (Fig. 6(b)), the left and right TC and the left and right DPC had significantly decreased FC values with the other three brain regions. The significant decreases in homotopic FC were located in the VPC, TC, and PPC. In ADHD-I patients (Fig. 6(c)), the FC values between the left PPC and the left and right DPCs were significantly decreased. The significant decrease in homotopic FC was only located in the PPC. Comparing ADHD-C and ADHD-I patients (Fig. 6(d)), the FC values between the TC and the PPC, the VPC, the left DPC, and the MPC were significantly decreased. No significantly decreased homotopic FC value was found. In addition, there was no significant difference between the male and female patients.

Discussion

Through ALFF analysis, we explored the ALFF patterns of ADHD patients and HCs. It was found that people with ADHD had significantly stronger spontaneous neural activity than the HCs in the right TC and the left VPC. This alteration was consistent with numerous fMRI results [48, 49]. Considering subtypes, several task-state studies have demonstrated differences in subtypes [22, 42] and sexes [50], while few resting-state studies have focused on subtypes and sexes. Our study filled the gap in this field. With respect to subtypes, we found that the TC in the ADHD-C group was significantly activated compared to HCs, while no brain region in the ADHD-I group exhibited significance. Compared with the ADHD-I group, the TC in the ADHD-C group was significantly activated. Concerning sex, the DPC, the MPC, and the TC in the male group were significantly activated compared with those in the female group. These results indicated that the spontaneous neural activity of ADHD patients during the resting state varied with subtype and sex.

We also found that people with ADHD had significantly decreased FC values between most channels compared with HCs. The decreases mainly existed between the left and right PPC, between the left and right DPC, between the left PPC and the DPC, and between the left DPC and the right TC. These FC decreases in the prefrontal cortex and the TC during the resting state were consistent with previous fMRI results [51, 52]. Considering subtypes and genders, the FC values in the ADHD-C group were significantly lower than those in the ADHD-I group, while there were few significant differences between the male and female groups. Zhang et al.. discovered that the ADHD-C group showed decreased functional connectivity in the superior temporal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and the dorsolateral superior frontal gyrus in comparison with the ADHD-I group [53], which was consistent with our results above. However, Rosch et al. [54]. and DuPont et al. [55]. found significant gender-related differences in ADHD patients. In our results, the FCs between partial channels were significantly different between the male and female groups, but these differences lost significance when analyzing the scale of brain regions. The inconsistency may be attributed to the lower spatial resolution of fNIRS than fMRI. We also speculated that both subtypes and sexes had an influence on the FC during the resting state, and the inconsistency of results was due to the uneven distribution of different subtypes in the male and female groups. Consequently, researchers need to carefully control the other factor when conducting a comparison of subtypes or genders.

Generally, we found significantly increased ALFF and decreased FC in ADHD children in comparison to HCs. These results indicated the potential that people with ADHD could be distinguished from normal people through resting-state ALFF and FC analysis. Liu, G. et al.. used ALFF and other features for machine learning, achieving a diagnostic accuracy of 77.0% [56]. Fateh, A. et al.. found that patients with ADHD exhibited decreased FC between specific brain regions compared with HCs [57]. Eloyan, A. et al.. created a prediction model using the landmark ADHD 200 data set focusing on resting-state FC and structural brain imaging, combined several prediction algorithms, and achieved an external test set specificity of 94% with a sensitivity of 21% [58]. These studies demonstrated the potential of ALFF and FC to be neuroimaging biomarkers for ADHD. In our study, significantly decreased FC existed in both all ADHD and the subtypes compared with HCs, and the two subtypes, ADHD-C and ADHD-I, also had significant differences. However, no significant difference was found in ALFF analysis between the ADHD-I and HC groups, which may be attributed to the weaker signal strength of rs-fNIRS detecting spontaneous brain activity than fMRI. Consequently, we supposed that ALFF and FC analysis could aid in differentiating ADHD patients from HCs and be used for the subtype diagnosis of ADHD.

Despite the intriguing discoveries, several issues and limitations should be discussed in this study. First, the sample size of the female group was relatively small, which may have affected the accuracy to some extent. In addition, only child patients were recruited, and the generality of our results was thus limited. The participation of adult patients would help better understand the neural development of people with ADHD. Additionally, the recruited children in this study were all simple without comorbidities, and the influence on ADHD studies remains unknown and needs further research. Future studies are expected to solve the issues above and conduct more approaches to analyze fNIRS data.

The strength of this study lies in its innovation and completeness. Through a literature review, it can be concluded that the effectiveness and reliability of rs-fNIRS have been established, while research using rs-fNIRS on ADHD is relatively scarce. This study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of using rs-fNIRS to diagnose ADHD subtypes, with the potential to provide more personalized treatment plans for patients through neurofeedback. Moreover, we are currently collecting rs-fNIRS data from a variety of psychiatric disorders, hoping that in the future, early diagnosis of multiple mental disorders can be achieved through a single data collection.

Conclusion

This study used rs-fNIRS to record spontaneous brain activity in children with different subtypes of ADHD and HCs. The ALFF and FC distributions for the PPC, TC, DPC, VPC, and MPC were determined. Compared with HCs, the right TC and the left VPC in ADHD patients were significantly more strongly activated, and FC was significantly decreased among the PPC, the TC, and the DPC. In ADHD-C patients, the left and right TC and the right VPC were significantly more strongly activated. The left and right TC and the left and right DPC had significantly decreased FC values with the other three brain regions, and the VPC, TC, and PPC had significantly decreased homotopic FC. In ADHD-I patients, no brain region exhibited significant activation. The FC between the left PPC and the left and right DPCs was significantly decreased, and the PPC had significantly decreased homotopic FC. Comparing subtypes, ADHD-C patients had significantly higher ALFF in the left and right TC and the right VPC and significantly lower FC between the TC and the PPC, the VPC, the left DPC, and the MPC than ADHD-I patients. In male patients, the left and right DPC, the MPC, and the left and right TC were significantly more strongly activated, and no significant difference in FC was found in comparison with female patients. This study demonstrated the combined analysis of resting-state ALFF and FC to be a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of ADHD. It also offered a biological basis for the classification of ADHD subtypes and might provide important guidance for the cognitive training of specific brain regions to achieve personalized neurofeedback therapy. The diagnosis of multiple psychiatric disorders using rs-fNIRS will make it possible to screen for brain functional abnormalities through a single data collection, facilitating early detection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ADHD-C

ADHD-combined subtype

- ADHD-I

ADHD-inattentive subtype

- HCs

Healthy controls

- fNIRS

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy

- fMRI

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- ALFF

Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation

- FC

Functional connectivity

- HbO

Oxyhemoglobin

- DSM

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- CDIS

Clinical Diagnostic Interview Scale

- IQ

Intelligence quotient

- C-WISC

Chinese-Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

- K-SADS-PL

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version

- Fpz

Frontopolar-prefrontal

- TDDR

Temporal derivative distribution

- VPC

Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex

- MPC

Medial prefrontal cortex

- TC

Temporal cortex

- PPC

Posterior prefrontal cortex

- DPC

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

Authors’ contributions

XX and HW designed the study; QL and WL wrote the manuscript; LC, NL and SW collected the brain functional imaging data; LY and YG analyzed the fNIRS data. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

Medical and Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2020361674).

Data availability

Data are available from the first and the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital (IRB number: 2016-15), in accordance with the "Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Beings". Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all participants before the experiment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qinwei Liu and Wenjing Liao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaobin Xu, Email: xuxiaobin@zju.edu.cn.

Huafen Wang, Email: 2185015@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sibley MH, Bruton AM, Zhao X, Johnstone JM, Mitchell J, Hatsu I, Arnold LE, Basu HH, Levy L, Vyas P, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(6):415–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salari N, Ghasemi H, Abdoli N, Rahmani A, Shiri MH, Hashemian AH, Akbari H, Mohammadi M. The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Baggio S, Billieux J, Dirkzwager A, Iglesias K, Moschetti K, Perroud N, Schneider M, Vernaz N, Wolff H, Heller P. Protocol of a monocentric, double-blind, randomized, superiority, controlled trial evaluating the effect of in-prison OROS-methylphenidate vs. placebo treatment in detained people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (BATIR). Trials. 2024;25(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barra S, Turner D, Müller M, Hertz PG, Retz-Junginger P, Tüscher O, Huss M, Retz W. ADHD symptom profiles, intermittent explosive disorder, adverse childhood experiences, and internalizing/externalizing problems in young offenders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin NeuroSci. 2022;272(2):257–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coxe S, Sibley MH. Harmonizing DSM-IV and DSM-5 versions of ADHD A criteria: an item response theory analysis. Assessment. 2023;30(3):606–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Zhou X, Gui Y, Liu M, Lu H. Multiple measurement analysis of resting-state fMRI for ADHD classification in adolescent brain from the ABCD study. Translational Psychiatry. 2023;13(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelini G, Lenartowicz A, Vera JD, Bilder RM, McGough JJ, McCracken JT, Loo SK. Electrophysiological and clinical predictors of Methylphenidate, Guanfacine, and Combined Treatment outcomes in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(4):415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal A, Parkes L, Aquino K, Kia SM, Wolfers T, Franke B, Hoogman M, Beckmann CF, Westlye LT, Andreassen OA, et al. Regional, circuit and network heterogeneity of brain abnormalities in psychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(9):1613–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu R, Huang ZA, Hu Y, Zhu Z, Wong KC, Tan KC. Spatial-Temporal Co-Attention Learning for Diagnosis of Mental Disorders From Resting-State fMRI Data. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems. 2024;35(8):10591-605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wang P, Wang J, Jiang Y, Wang Z, Meng C, Castellanos FX, Biswal BB. Cerebro-cerebellar dysconnectivity in children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(11):1372–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandewouw MM, Brian J, Crosbie J, Schachar RJ, Iaboni A, Georgiades S, Nicolson R, Kelley E, Ayub M, Jones J, et al. Identifying replicable subgroups in neurodevelopmental conditions using resting-state functional magnetic resonance Imaging Data. JAMA Netw open. 2023;6(3):e232066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharini H, Fooladi M, Masjoodi S, Jalalvandi M, Yousef Pour M. Identification of the Pain process by Cold Stimulation: using Dynamic Causal modeling of effective connectivity in Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). IRBM. 2019;40(2):86–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turk-Browne NB, Aslin RN. Infant neuroscience: how to measure brain activity in the youngest minds. Trends in neurosciences. 2024;47(5):338-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Karunakaran KD, Kussman BD, Peng K, Becerra L, Labadie R, Bernier R, Berry D, Green S, Zurakowski D, Alexander ME, et al. Brain-based measures of nociception during general anesthesia with remifentanil: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalalvandi M, Sharini H, Naderi Y, Alam NRJFBT. Assessment of Brain cortical activation in Passive Movement during wrist Task using functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). Frontiers in Biomedical Technologies. 2019;6(2):99-105.

- 17.Jalalvandi M, Riyahi Alam N, Sharini H, Hashemi H, Nadimi M. Brain cortical activation during Imagining of the wrist Movement using functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). J Biomedical Phys Eng. 2021;11(5):583–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuo L, Zhao X, Zhai Y, Zhao B, Tian L, Zhang Y, Wang X, Zhang T, Gan X, Yang C, et al. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Translational Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr-German A, White SF, Santosa H, Buss AT, Doucet GE. Assessing the relationship between maternal risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and functional connectivity in their biological toddlers. Eur Psychiatry: J Association Eur Psychiatrists. 2022;65(1):e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Y, Miao S, Zhang Y, Yang J, Li X. Compressibility Analysis of Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Signals in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. IEEE J Biomedical Health Inf. 2023;27(11):5449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu N, Jia G, Li H, Zhang S, Wang Y, Niu H, Liu L, Qian Q. The potential shared brain functional alterations between adults with ADHD and children with ADHD co-occurred with disruptive behaviors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health. 2022;16(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y, Liu S, Zhang F, Ren Y, Zhang T, Sun J, Wang X, Wang L, Yang J. Response inhibition in children with different subtypes/presentations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Front NeuroSci. 2023;17:1119289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehlis AC, Bähne CG, Jacob CP, Herrmann MJ, Fallgatter AJ. Reduced lateral prefrontal activation in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) during a working memory task: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) study. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(13):1060–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabio RA, Andricciola F, Caprì T. Visual-motor attention in children with ADHD: the role of automatic and controlled processes. Res Dev Disabil. 2022;123:104193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, Chen W, Preece DA, Xu D, Li H, Liu N, Fu G, Wang Y, Qian Q, Gross JJ, et al. Emotion dysregulation in adults with ADHD: the role of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. J Affect Disord. 2022;319:267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faraone SV, Bellgrove MA, Brikell I, Cortese S, Hartman CA, Hollis C, Newcorn JH, Philipsen A, Polanczyk GV, Rubia K, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2024;10(1):11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monden Y, Dan I, Nagashima M, Dan H, Uga M, Ikeda T, Tsuzuki D, Kyutoku Y, Gunji Y, Hirano D, et al. Individual classification of ADHD children by right prefrontal hemodynamic responses during a go/no-go task as assessed by fNIRS. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;9:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichikawa H, Nakato E, Kanazawa S, Shimamura K, Sakuta Y, Sakuta R, Yamaguchi MK, Kakigi R. Hemodynamic response of children with attention-deficit and hyperactive disorder (ADHD) to emotional facial expressions. Neuropsychologia. 2014;63:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Zhang YJ, Duan L, Ma SY, Lu CM, Zhu CZ. Is resting-state functional connectivity revealed by functional near-infrared spectroscopy test-retest reliable? J Biomed Opt. 2011;16(6):067008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu H, He Y. Resting-state functional brain connectivity: lessons from functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuroscientist: Rev J Bringing Neurobiol Neurol Psychiatry. 2014;20(2):173–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Duan L, Zhang YJ, Lu CM, Liu H, Zhu CZ. Test-retest assessment of independent component analysis-derived resting-state functional connectivity based on functional near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage. 2011;55(2):607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia G, Hubbard CS, Hu Z, Xu J, Dong Q, Niu H, Liu H. Intrinsic brain activity is increasingly complex and develops asymmetrically during childhood and early adolescence. NeuroImage. 2023;277:120225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang HY, Ren L, Li T, Pu L, Huang X, Wang S, Song C, Liang Z. The impact of anxiety on the cognitive function of informal Parkinson’s disease caregiver: evidence from task-based and resting-state fNIRS. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:960953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Sun N, Xiong J, Zhou Y, Ye X, Jiang H, Guo H, Zhi N, Lu J, He P, et al. Modulation of cerebral cortex activity by acupuncture in patients with prolonged disorder of consciousness: an fNIRS study. Front NeuroSci. 2022;16:1043133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang M, Qu Y, Li Q, Gu C, Zhang L, Chen H, Ding M, Zhang T, Zhen R, An H. Correlation between Prefrontal Functional Connectivity and the degree of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease: a functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. J Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 2024;98(4):1287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomasi D, Manza P, Yan W, Shokri-Kojori E, Demiral ŞB, Yonga MV, McPherson K, Biesecker C, Dennis E, Johnson A, et al. Examining the role of dopamine in methylphenidate’s effects on resting brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120(52):e2314596120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang X, Guo Z, Chen G, Sun S, Xiao S, Chen P, Tang G, Huang L, Wang Y. A Multimodal Meta-Analytical evidence of functional and structural brain abnormalities across Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;95:102240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo Y, Dong D, Huang H, Zhou J, Zuo X, Hu J, He H, Jiang S, Duan M, Yao D, et al. Associating Multimodal Neuroimaging Abnormalities with the Transcriptome and Neurotransmitter Signatures in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49(6):1554–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Wang W, Bai X, Mei Y, Tang H, Yuan Z, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang P, Hu Z, et al. Alterations in regional homogeneity and multiple frequency amplitudes of low-frequency fluctuation in patients with new daily persistent headache: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slater J, Joober R, Koborsy BL, Mitchell S, Sahlas E, Palmer C. Can electroencephalography (EEG) identify ADHD subtypes? A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;139:104752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayano G, Demelash S, Gizachew Y, Tsegay L, Alati R. The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo N, Luo X, Zheng S, Yao D, Zhao M, Cui Y, Zhu Y, Calhoun VD, Sun L, Sui J. Aberrant brain dynamics and spectral power in children with ADHD and its subtypes. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(11):2223–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghanizadeh A. Agreement between Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, Fourth Edition, and the proposed DSM-V attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnostic criteria: an exploratory study. Compr Psychiatr. 2013;54(1):7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishiyama T, Sumi S, Watanabe H, Suzuki F, Kuru Y, Shiino T, Kimura T, Wang C, Lin Y, Ichiyanagi M, et al. The Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) for DSM-5: a validation for neurodevelopmental disorders in Japanese outpatients. Compr Psychiatr. 2020;96:152148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou X, Zhang Z, Zhao C, Duan L, Gong Y, Li Z, Zhu C. NIRS-KIT: a MATLAB toolbox for both resting-state and task fNIRS data analysis. Neurophotonics. 2021;8(1):010802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oshina I, Spigulis J. Beer-Lambert law for optical tissue diagnostics: current state of the art and the main limitations. J Biomed Opt. 2021;26(10):100901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Fishburn FA, Ludlum RS, Vaidya CJ, Medvedev AV. Temporal derivative distribution repair (TDDR): a motion correction method for fNIRS. NeuroImage. 2019;184:171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pereira-Sanchez V, Castellanos FX. Neuroimaging in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(2):105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubia K, Westwood S, Aggensteiner PM, Brandeis D. Neurotherapeutics for attention Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review. Cells. 2021;10(8):2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Lee SH, Chia S, Chou TL, Gau SS. Sex differences in medication-naïve adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a counting Stroop functional MRI study. Biol Psychol. 2023;179:108552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmadi M, Kazemi K, Kuc K, Cybulska-Klosowicz A, Helfroush MS, Aarabi A. Resting state dynamic functional connectivity in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Neural Eng. 2021;18(4):0460d1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Cortese S, Aoki YY, Itahashi T, Castellanos FX, Eickhoff SB. Systematic review and Meta-analysis: resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(1):61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H, Zhao Y, Cao W, Cui D, Jiao Q, Lu W, Li H, Qiu J. Aberrant functional connectivity in resting state networks of ADHD patients revealed by independent component analysis. BMC Neurosci. 2020;21(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosch KS, Mostofsky SH, Nebel MB. ADHD-related sex differences in fronto-subcortical intrinsic functional connectivity and associations with delay discounting. J Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2018;10(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dupont G, van Rooij D, Buitelaar JK, Reif A, Grimm O. Sex-related differences in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder patients - an analysis of external Globus Pallidus functional connectivity in resting-state functional MRI. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:962911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu G, Lu W, Qiu J, Shi L. Identifying individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on multisite resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging: a radiomics analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2023;44(8):3433–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fateh AA, Huang W, Mo T, Wang X, Luo Y, Yang B, Smahi A, Fang D, Zhang L, Meng X, et al. Abnormal insular dynamic functional connectivity and its relation to Social Dysfunctioning in Children with attention Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. Front NeuroSci. 2022;16:890596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eloyan A, Muschelli J, Nebel MB, Liu H, Han F, Zhao T, Barber AD, Joel S, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH, et al. Automated diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactive disorder using magnetic resonance imaging. Front Syst Neurosci. 2012;6:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the first and the corresponding authors.