Abstract

Background

Previous studies indicate an increasing prevalence of depression among university students worldwide. Besides, university students are more likely to excessively use smartphones, making them more susceptible to smartphone addiction. Pandemic conditions can also have negative effects on mental health. Thus, this study aims to investigate the frequency of depression among university students during COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The study population for this mixed-method research, which includes both qualitative and quantitative components, consists of students studying health sciences at a state university in Istanbul, Türkiye. No sample was selected for the quantitative data collection; instead, it was aimed to reach the entire population. Sociodemographic characteristics, the 10-item Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV), and the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were used. In the qualitative part of our study, semi-structured online interviews were conducted with 12 students. Statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The study, involving 819 students, found that 25.2% had moderate depression and 5.7% had severe depression. A statistically significant relationship was found between self-perceived smartphone addiction and the presence of moderate-severe depression (p < 0.001). Participants who spent more than 4 h a day on their smartphones, those who checked their smartphones more than 30 times a day, those who perceived themselves as smartphone addicts, and those who experienced smartphone-related sleep problems obtained statistically significantly higher scores from BDI compared to others (p < 0.05). According to our qualitative results, some participants thought that smartphone use could cause a depressive mood by isolating people, while others believed it could do so through the negative effects of social media. All participants reported that the quarantine period increased their smartphone usage.

Conclusion

Our results suggest a potential interaction between smartphone addiction and depression. This indicates the potential benefit of assessing and addressing both conditions simultaneously.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-21075-7.

Keywords: Depression, University students, Smartphone, Addiction, Mental health

Background

Technology addiction is defined as a non-substance-related behavioral addiction involving human-machine interaction, which extends beyond substance addiction to encompass behavioral addictions such as gambling, internet gaming, and excessive smartphone use [1]. While there is not yet sufficient evidence-based research to include smartphone addiction in the DSM-5, a growing body of studies suggests that smartphone use is associated with addiction features such as preoccupation, developing tolerance, inability to control cravings, impairment of daily life functions, overlooking harmful consequences, and withdrawal symptoms [2].

Despite the advantages associated with advanced social networking, improved work methods, and increased productivity through smartphone use, previous research indicates that excessive smartphone use negatively impacts individuals’ daily lives and physical health [3–5]. Furthermore, excessive smartphone use has been associated with mental and behavioral issues, such as changes in attitude towards school or work, reduced and disrupted real-life social interactions, and potential mental health problems . Studies have also linked smartphone addiction to a predisposition to depression, loneliness, anxiety, and sleep disorders [6, 7].

University students, undergoing a critical transition from adolescence to adulthood, represent a special group facing one of the most stressful times in their lives. Struggling to adapt, aiming for good grades, planning for the future, and being away from home can create anxiety for many students [8]. Previous studies indicate an increasing prevalence of depression among university students worldwide [9–11]. More than two-thirds of young people do not talk about or seek help for mental health issues [12]. Due to this introverted behavior, university students are more likely to excessively use smartphones, making them more susceptible to smartphone addiction [13].

This study aims to investigate the frequency of depression and the relationship between smartphone addiction and depression among university students in the field of health sciences. The results of this study may contribute to a better understanding of the impact of smartphone use and addiction on mental health in young adults and provide valuable insights for the development of relevant intervention strategies.

Methods

Research type, population, and sample

The research is a mixed-method study with qualitative and quantitative components. The population of the study consists of undergraduate students studying in health sciences at a state university on the Anatolian side of Istanbul. The Faculty of Health Sciences has 688 students, the Faculty of Dentistry has 775, the Faculty of Medicine has 1523, and the Faculty of Pharmacy has 773 students. The population was determined to be 3729 undergraduate students. The data collection for quantitative variables took place between September and December 2020. An online survey link was sent to all students via WhatsApp through the student affairs offices of the faculties. No specific sampling method was used, and the response rate for the survey was 21.96%, with 819 participants.

Measurements and data collection

A literature-reviewed 20-item information form assessing sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors was used in addition to the 10-item Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV) and the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

SAS-SV

Developed by Kwon et al., the scale aims to measure smartphone addiction. It consists of 10 items evaluated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree [14]. The scale is unidimensional and does not have sub-dimensions. As the score increases, the risk for addiction also increases. The cutoff scores were specified as 31 for males and 33 for females [14].

BDI: Developed by Beck and colleagues, this scale aims to measure the level and severity of depression in individuals, including emotional, cognitive, somatic, and motivational components [15]. The scale comprises 21 items, each identifying a specific behavioral pattern related to depression, with 4 response options on a scale from 0 to 3. Scores on the scale can range from 0 to 63. Severity is interpreted as follows: 0–9 = Minimal or none, 10–16 = Mild, 17–29 = Moderate, 30–63 = Severe [16]. In this study, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) was used, which is widely used in both clinical practices and researches.

For the qualitative part of the study, in-depth interviews were conducted with 12 students using a semi-structured questionnaire via the “Zoom Meetings” application. This questionnaire was created by participants to gain an in-depth understanding of factors that may be associated with smartphone addiction and depression. The questionnaire is presented as supplementary material (Supp. 1).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including number (n) and percentage (%), were used to summarize the categorical data, while means and standard deviations (SD) were employed for normally distributed continuous variables. For non-normally distributed continuous variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used. The chi-square test was applied to analyze categorical variables. Normality was assessed using both visual methods (histograms and Q-Q plots) and analytical methods (Kolmogorov–Smirnov/Shapiro–Wilk tests). For comparisons of two independent groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used if the data did not follow a normal distribution. For comparisons involving three or more independent groups with non-normal distributions, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. Spearman correlation test was employed to evaluate the relationships between non-normally distributed variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine the strength and direction of consistent relationships between variables, with values ranging from − 1 to + 1. SPSS version 25 program was used for data recording and analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

During in-depth interviews, with participants’ consent, recordings were made and later transcribed into written form. A total of 65 pages of content were obtained. For the analysis of qualitative data, codes, subthemes and themes were identified for the interviews related to the study. Direct quotations were used in presenting the findings.

Ethical approval

The research obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Marmara University Faculty of Medicine under protocol code 09.2020.300 on March 6, 2020. Additionally, permissions were obtained from the deaneries of the relevant faculties. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants.

Results

Descriptive findings

The participants had an mean age of 21.17 ± 1.95. Three-fourths of the participants were female students (76.5%, n = 625). The majority of participants were from the Faculty of Medicine (36.5%, n = 299), and one-fifth were first-year students (21.6%, n = 177).

Approximately half of the participants reported that they find it easy to make friends (47.5%, n = 389), while three-quarters evaluated their friendship relationships as good (74.1%, n = 607).

About 38.9% of the participants mentioned spending more time on their phones due to loneliness. Additionally, 6.8% stated that they had no one to confide in, and 91.9% reported not having any psychiatric illnesses. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| n:819 | n | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 625 | 76.3 |

| Male | 194 | 23.7 | |

| Faculty | Medicine | 299 | 36.5 |

| Dentistry | 215 | 26.3 | |

| Pharmacy | 175 | 21.4 | |

| Health Sciences | 130 | 15.9 | |

| Academic Year | 1st | 177 | 21.6 |

| 2nd | 137 | 16.7 | |

| 3rd | 143 | 17.5 | |

| 4th | 149 | 18.2 | |

| 5th | 158 | 19.3 | |

| 6th | 55 | 6.7 | |

| Ease of Making Friends | Yes | 389 | 47.5 |

| Sometimes | 315 | 38.5 | |

| No | 115 | 14.0 | |

| Friendship Relationships | Good | 607 | 74.1 |

| Moderate | 202 | 24.7 | |

| Poor | 10 | 1.2 | |

| Phone Use Due to Loneliness | Yes | 319 | 38.9 |

| Sometimes | 297 | 36.3 | |

| No | 203 | 24.8 | |

| Someone to confide in | Yes | 763 | 93.2 |

| No | 56 | 6.8 | |

| Presence of Any Psychiatric Illness | Yes | 66 | 8.1 |

| No | 753 | 91.9 | |

Participants’ features regarding smartphone usage

Approximately one-fourth of the participants reported using smartphones for more than 5 h per day (24.2%, n = 198), feeling the need to check their phones more than 40 times a day on average (25.3%, n = 207), and considering themselves addicted to smartphones (26.1%, n = 214). About half of the participants reported not experiencing smartphone-related sleep problems (49.0%, n = 401). The mean duration of smartphone use among participants was 7.37 ± 2.01 years, with an mean age of 14.03 ± 2.20 when they first started using smartphones. Table 2 displays the features of participants’ smartphone usage.

Table 2.

Participants’ features regarding smartphone usage

| n: 819 | n | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Engagement Time with Smartphone | Less than 1 h | 11 | 1.3 |

| 1–2 h | 101 | 12.3 | |

| 2–4 h | 299 | 36.5 | |

| 4–5 h | 210 | 25.6 | |

| Over 5 h | 198 | 24.2 | |

| Average Daily Smartphone Checks | Less than 10 times | 47 | 5.7 |

| 11–20 times | 196 | 23.9 | |

| 21–30 times | 229 | 28.0 | |

| 31–40 times | 140 | 17.1 | |

| Over 40 times | 207 | 25.3 | |

| Perception of Smartphone Addiction | Yes | 214 | 26.1 |

| Maybe | 326 | 39.8 | |

| No | 279 | 34.1 | |

| Presence of Smartphone-Related Sleep Problems | Yes | 135 | 16.5 |

| Sometimes | 283 | 34.5 | |

| No | 401 | 49.0 | |

| Mean | (± SD) | ||

| Duration of Smartphone Usage (Years) | 7.37 | 2.01 | |

| Age When Started Using Smartphone | 14.03 | 2.20 | |

Univariate analyses for smartphone addiction scale-short version

The average score obtained from the SAS-SV by the students participating in the research was 27.85 ± 9.99. When the cutoff scores were set at 31 for males and 33 for females, the prevalence of smartphone addiction was found to be 29.8% (n = 244).

Female students had a statistically significantly higher SAS-SV score compared to males (p < 0.001). When the scores obtained from the SAS-SV were compared according to the participants’ faculty and class level, no statistically significant difference was found (p > 0.05). Participants who reported being able to make friends easily had significantly lower SAS-SV scores compared to others (p = 0.006, p = 0.018). Those who reported that their friendships were poor had statistically significantly higher SAS-SV scores than those who reported that their friendships were good (p = 0.008). Participants who reported spending more time on their smartphones due to feelings of loneliness had statistically significantly higher scores on the SAS-SV compared to others (p < 0.001). Conversely, those who reported not spending more time on their smartphones due to feelings of loneliness had statistically significantly lower SAS-SV scores compared to others (p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in the SAS-SV scores between participants based on whether they had someone to confide in and the presence of any psychiatric illness (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

SAS-SV scores according to sociodemographic characteristics

| Median | IQR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 27.00 | 14.00 | < 0.001 a |

| Male | 25.00 | 13.00 | ||

| Faculty | Medicine | 27.00 | 15.00 | 0.555 a |

| Dentistry | 27.00 | 13.00 | ||

| Pharmacy | 26.00 | 16.00 | ||

| Health Sciences | 26.00 | 12.50 | ||

| Academic Year | 1st | 28.00 | 14.00 | 0.158 a |

| 2nd | 28.00 | 15.00 | ||

| 3rd | 29.00 | 16.00 | ||

| 4th | 25.00 | 10.50 | ||

| 5th | 26.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 6th | 26.00 | 16.00 | ||

| Ease of Making Friends | Yes | 25.00 | 13.00 | 0.007 a |

| Sometimes | 28.00 | 14.00 | ||

| No | 28.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Friendship Relationships | Good | 26.00 | 13.00 | 0.010 a |

| Moderate | 28.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Poor | 31.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Phone Use Due to Loneliness | Yes | 31.00 | 16.00 | < 0.001 a |

| Sometimes | 26.00 | 11.00 | ||

| No | 22.00 | 13.00 | ||

| Someone to confide in | Yes | 27.00 | 13.00 | 0.514 b |

| No | 26.50 | 17.25 | ||

| Presence of Any Psychiatric Illness | Yes | 28.50 | 11.25 | 0.372 b |

| No | 27.00 | 15.00 | ||

a Kruskal Wallis Test. b Mann Whitney U Test

The level of addiction was found to increase significantly as participants’ smartphone engagement time increased and the average number of smartphone checks per day rose to 40 (p < 0.001). Participants who perceived themselves as smartphone addicts and those experiencing smartphone-related sleep problems had significantly higher scores on the SAS-SV compared to others (p < 0.001). No significant correlation was observed between participants’ age, smartphone usage time, and age of starting smartphone use with the scores obtained from the SAS-SV (p > 0. 05).

Univariate analyses for Beck Depression Inventory

The average score on the BDI obtained by the participating students is 13.25 ± 8.75. In all participating students, the frequency of none/minimal depression was 40.8% (n = 334), mild depression frequency was 28.3% (n = 232), moderate depression frequency was 25.2% (n = 206), and severe depression frequency was 5.7% (n = 47).

When the scores from the BDI are compared based on the participants’ class levels, it was found that students in the 2nd year statistically significantly scored higher than other students (p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in the BDI scores based on participants’ gender and faculty variables (p > 0.05). Participants who reported being able to easily make friends and those who reported having good friendships had statistically significantly lower scores on the BDI compared to others (p < 0.001). Participants who reported spending more time with their smartphones due to loneliness, those who reported having no one to confide in, and those who reported having any psychiatric illness statistically significantly scored higher on the BDI compared to others (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Beck Depression Inventory scores according to sociodemographic characteristics

| Median | IQR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 12.00 | 11.00 | 0.160a |

| Male | 11.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Faculty | Medicine | 12.00 | 12.00 | 0.062a |

| Dentistry | 11.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Pharmacy | 11.00 | 9.00 | ||

| Health Sciences | 14.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Academic Year | 1st | 13.00 | 11.00 | < 0.001a |

| 2nd | 15.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 3rd | 12.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 4th | 11.00 | 11.00 | ||

| 5th | 10.00 | 10.00 | ||

| 6th | 9.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Ease of Making Friends | Yes | 9.00 | 10.50 | < 0.001 a |

| Sometimes | 13.00 | 12.00 | ||

| No | 16.00 | 12.00 | ||

| Friendship Relationships | Good | 10.00 | 11.00 | < 0.001 a |

| Moderate | 16.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Poor | 16.50 | 9.25 | ||

| Phone Use Due to Loneliness | Yes | 16.00 | 11.00 | < 0.001 a |

| Sometimes | 10.00 | 10.00 | ||

| No | 8.00 | 9.00 | ||

| Someone to confide in | Yes | 11.00 | 11.00 | < 0.001 b |

| No | 22.00 | 13.75 | ||

| Presence of Any Psychiatric Illness | Yes | 18.00 | 15.75 | < 0.001 b |

| No | 11.00 | 11.00 | ||

a Kruskal Wallis Test. b Mann Whitney U Test

Smartphone usage characteristics and depression

Participants who spent more than an average of 4 h a day on their smartphones, those who checked their smartphones more than 30 times a day, those who perceived themselves as smartphone addicts, and those who experienced smartphone-related sleep problems obtained statistically significantly higher scores from BDI compared to others (p < 0.05). (Table 5).

Table 5.

Beck Depression Inventory scores according to smartphone usage characteristics

| Median | IQR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Engagement Time with Smartphone | Less than 1 h | 8.00 | 10.00 | 0.001a |

| 1–2 h | 9.00 | 10.50 | ||

| 2–4 h | 11.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 4–5 h | 13.00 | 12.00 | ||

| Over 5 h | 13.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Average Daily Smartphone Checks | Less than 10 times | 10.00 | 11.00 | 0.001a |

| 11–20 times | 10.00 | 11.00 | ||

| 21–30 times | 11.00 | 12.00 | ||

| 31–40 times | 14.00 | 13.50 | ||

| Over 40 times | 13.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Perception of Smartphone Addiction | Yes | 12.00 | 10.50 | < 0.001a |

| Maybe | 12.00 | 12.00 | ||

| No | 11.00 | 12.00 | ||

| Presence of Smartphone-Related Sleep Problems | Yes | 18.00 | 14.00 | < 0.001a |

| Sometimes | 13.00 | 11.00 | ||

| No | 9.00 | 10.00 | ||

aKruskal Wallis Test

Correlation between depression and smartphone addiction

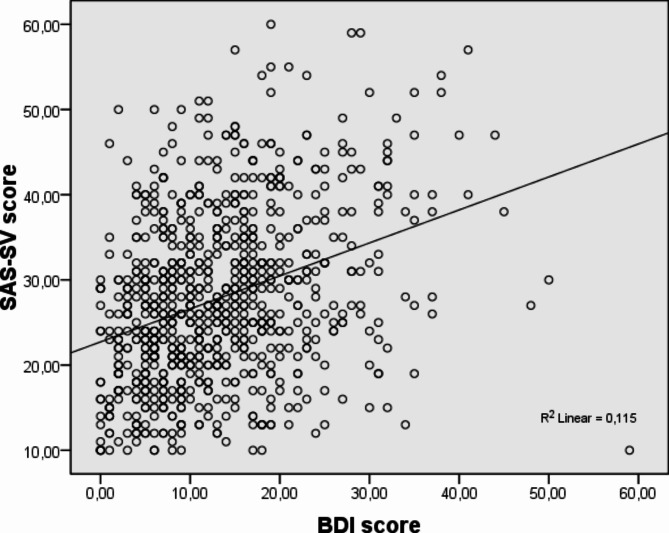

When evaluating the relationship between smartphone addiction and depression, a positively moderate correlation was found between the scores students obtained from SAS-SV and BDI (r = 0.338, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The correlation between depression and smartphone addiction

Qualitative findings

The socio-demographic characteristics of participants involved in in-depth interviews are summarized in supplementary Table (Supp. 2).

The analyses resulted in four themes: Orientation towards Smartphone Usage, Effects of Smartphone Usage, Smartphone Addiction, and Depression. Sixteen subthemes related to themes were determined. The themes and subthemes are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Themes and subthemes

| THEMES | SUBTHEMES |

|---|---|

| Orientation to Smartphone Usage | Meaning attributed to the smartphone |

| Smartphone usage purposes | |

| Periods spent most time with smartphone | |

| Pandemic effect | |

| Effects of Smartphone Usage | The impact of smartphone usage on mental well-being |

| The physical effects of smartphone usage | |

| The impact of smartphone usage on studies | |

| Feelings when not with the smartphone | |

| The relationship between smartphone usage and family and friend relationships | |

| The impact of smartphone usage on sociability and loneliness | |

| Smartphone Addiction | Definition of smartphone addiction |

| Symptoms of smartphone addiction | |

| Reasons for being addicted to smartphones | |

| Behavior of smartphone use | |

| Depression | The meaning of depression |

| The relationship between smartphone use and depression |

Theme 1: orientation to smartphone usage

The sub-themes related to orientation to smartphone usage are ‘Meaning attributed to the smartphone,’ ‘Purposes of smartphone usage,’ ‘Periods when the smartphone is used the most,’ and ‘Effect of the pandemic’.

Meaning attributed to the smartphone

Below are the codes and participant expressions related to the meanings attributed to the smartphone, listed in order of frequency:

• Convenience.

“Smartphone is a device I use in my daily life, making my tasks easier. Essentially, under the phone category, it’s a condensed version of many technological devices into one. So, it’s essentially a tiny computer. It’s a device that makes life easier.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

• Indispensable in life.

“For me, it means a lot. It’s like breathing right now. It has a lot of importance in our lives; we use it in every field. So, sometimes it feels like we can’t live without it right now.” (Age: 21, Faculty of Pharmacy).

• Communication tool.

“Communication. I see it more as a means of communication.” (Age: 22, Faculty of Pharmacy).

Smartphone usage purposes

Almost all participants indicated social media as one of the purposes of smartphone use. Other purposes of smartphone use, in order of frequency, include communication, assisting in lessons, and watching series and movies.

Here are some statements from participants regarding the purposes of smartphone use:

“For help in my lessons, to video chat and chat with my friends, to use social media tools, I use it in most aspects of my life.” (Age: 19, Faculty of Pharmacy).

Periods spent most time with smartphone

The periods during which participants spent the most time with their smartphones, in order of frequency, are when they are alone, constantly, during exam periods, in the evening, and during free time.

Pandemic effect

All participants reported that the quarantine period and online education during the pandemic had negative effects on their smartphone usage and increased smartphone usage.

• Quarantine Effect.

“Before the pandemic, I didn’t use my phone this much. Because, normally, when our social life continued, we could socialize by going out for meals and spending time together during our free time. But that completely disappeared, and smartphones stepped in to fill the gap, I think.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

• Online Education Effect.

“I think smartphone usage increased more during online classes because during online lessons, classes are seen online, and using the phone while looking into the teacher’s eyes during live lessons wouldn’t be nice.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

Theme 2: effects of smartphone usage

Sub-themes related to the effects of smartphone usage are “The impact of smartphone usage on mental well-being,” “The physical effects of smartphone usage,” “The impact of smartphone usage on studies,” “Feelings when not with the smartphone,” “The relationship between smartphone usage and family and friend relationships,” and “The impact of smartphone usage on sociability and loneliness.”

The impact of smartphone usage on mental well-being

Participants have mostly mentioned that smartphone use has the most impact on their mental state in terms of regret and feeling bad. Other effects mentioned include self-doubt, feeling good, feeling unproductive, and feeling accomplished.

“When you feel the need to use it constantly, you experience a mental breakdown. It’s like feeling dependent, as if you have to use it all the time. I personally think it affects you mentally.” (Age: 21, Faculty of Health Sciences).

“People who work hard to create content there and work as a team make me feel inadequate. For example, the models there, the lives of the people there make me feel inadequate. It’s like I can’t do things perfectly.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

“It gives a short-term happiness, then it gives me regret. Because wasting my life, wasting my time, especially during the best years of my life, this makes me a bit sad.” (Age: 21, Faculty of Pharmacy).

The physical effects of smartphone usage

Participants have reported physical effects of smartphone use, including vision problems, headaches, and a decrease in sleep quality.

“It affects sleep quality, in my opinion. When the eyes are exposed to the light of the phone for a long time, it somehow affects and I think what you see on the phone also affects our subconscious. It’s not a pure sleep.” (Age: 21, Faculty of Pharmacy).

The impact of smartphone usage on studies

Participants have reported that smartphone use has both positive and negative effects on their studies.

“It affects in two ways. The negative impact is when I lose focus during classes, I start looking at my phone. Even if it’s not next to me, I go and get it to check during class. This distracts me from the lesson. The positive impact is the access to information. Because access to information is very easy, I see a lot of positive effects of the smartphone.” (Age: 18, Faculty of Dentistry).

Feelings when not with the smartphone

Most participants have stated that they feel restless and anxious when their phones are not with them.

“I get very restless. When my phone is charging, when the battery is dead, or when it’s somewhere else, my mind is on my phone.” (Age: 18, Faculty of Dentistry).

The relationship between smartphone usage and family and friend relationships

Most participants have indicated that smartphone use negatively affects family and friend relationships. They believe that individuals with poor family relationships may use their phones more as a way of avoiding communication with their families. Similarly, many participants think that phone use affects friendships; those with poor friend relationships might use smartphones more, or individuals with a wide circle of friends might use smartphones more.

“People who are not very happy in their friend circle or don’t have many friends try to make friends or fulfill their need for conversation through social media.” (Age: 18, Faculty of Dentistry).

“I think it negatively affects family relationships because when you spend time on your phone, it’s not spent with the family. For example, in the past, when we watched TV, we all focused on the same thing, but it’s not like that now. Everyone started watching what they wanted on their smartphones. This way, there’s no conversation. I think it negatively affects family relationships in this way.” (Age: 22, Faculty of Health Sciences).

The impact of smartphone usage on sociability and loneliness

Some participants think that using a smartphone makes people more social, while others believe it leads to loneliness. Some participants also mentioned that it depends on how a person uses their smartphone.

“For me, it isolated everyone in a very, very, very intense way. I can never see any positive side of it… It seems like it’s socializing, but it isolates. In my opinion, it makes lonely people even more lonely…” (Age: 21, Faculty of Dentistry).

“I think we socialize in this way; when you talk to friends, make plans, it becomes a means, after all. For example, on WhatsApp, a group is created, for instance, a Saturday theater group. So, in that sense, it contributes to socializing.” (Age: 25, Faculty of Medicine).

Theme 3: smartphone addiction

Subthemes related to smartphone addiction include ‘Definition of smartphone addiction,’ ‘Symptoms of smartphone addiction,’ ‘Reasons for being addicted to smartphones,’ and ‘Behavior of smartphone use.’

Definition of smartphone addiction

Participants generally defined smartphone addiction as spending too much time on the phone, developing a habit of holding it, and feeling unable to live without it.

“Smartphone addiction can be defined as spending too much time on the phone to the extent that it hinders daily activities.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

Symptoms of smartphone addiction

Statements regarding smartphone addiction symptoms reported by participants include being unable to stay away from the phone to the extent that it disrupts daily activities, the need to check it constantly, eating disorders, and experiencing withdrawal symptoms.

Reasons for being addicted to smartphones

Reasons for smartphone addiction reported by participants include boredom, social isolation, escapism from daily life, social media, and the opportunities it provides.

“For me, people don’t have beautiful lives economically. Mine is like that too. Seeing those contents makes us feel like we are part of them. But it’s not like that. … For example, when I look while on the bus, everything is in chaos and poverty, but the content on social media is not like that. Wealth, beauty, health, everything is there, and seeing these things, I think, makes people happy and takes them away from the pains of real life.” (Age: 24, Faculty of Medicine).

Behavior of smartphone use

All participants discussed their smartphone usage durations, and some also mentioned their efforts to reduce usage.

“If we’re awake for 12–14 hours, I think it’s normal to use it for 8–10 hours of that time.” (Age: 22, Faculty of Health Sciences).

Theme 4: depression

Sub-themes related to depression are “The meaning of depression” and “The relationship between smartphone use and depression.”

The meaning of depression

Participants’ expressions regarding the meaning of depression include feelings of reluctance, inability to enjoy, feeling unhappy, lack of communication, and a state of fatigue.

“Truly, a period where a person withdraws into themselves, doesn’t want to do anything, can’t do anything, can’t even get out of bed, I think.” (Age: 20, Faculty of Health Sciences).

“A person feeling unhappy for no reason during times when they should feel happy. I can define constantly feeling unhappy as depression.” (Age: 19, Faculty of Pharmacy).

The relationship between smartphone use and depression

Some participants believe that smartphone use can lead to loneliness, while others think that the negative effects of social media can contribute to depressive feelings. It has been expressed by many participants that a person in depression might turn to smartphones, seeking refuge in social media or other entertainment content offered by the phone, in order to escape from real-world difficulties, leading to an increase in smartphone use.

• The impact of smartphone usage on depression:

“I believe that smartphones can become highly addictive. I think they contribute to social isolation, which, in turn, affects depression and depressive states. I also believe that social media has a significant impact on depression.” (Age: 18, Faculty of Dentistry).

• The impact of depression on smartphone usage:

“Perhaps individuals entering depression use smartphones more. Because why were they depressed? Family life might be challenging, and to escape from that, they would want to turn to social media, friends, or entertaining content, which they can find on smartphones. Therefore, if they become depressed, I believe they would immediately turn to smartphones as an outlet.” (Age: 22, Faculty of Health Sciences).

Discussion

In the study, factors related to smartphone addiction and depression were evaluated among university students in the health field. The prevalence of smartphone addiction was found to be 29.8%. Similarly, in a study conducted among medical faculty students, the prevalence of smartphone addiction was also found to be 29.8% [17].

Studies in the literature also report that the prevalence of smartphone addiction is higher in female participants than males [18]. Similarly, in this study, smartphone addiction differed between genders, and the level of smartphone addiction was found to be higher in females compared to males. Understanding the relationship between gender and smartphone addiction requires further investigation. A study conducted in South Korea suggested that female participants may be more aware of their addictions based on higher self-report scores [19]. In our study, it was found that as participants’ interest in smartphones increased in terms of time spent and frequency of interaction, the level of smartphone addiction also increased. A study by Aljomaa et al. similarly found significant differences, with higher smartphone addiction levels in participants who used their smartphones for more than 4 h a day [20]. In other words, the longer individuals spend on their smartphones, the higher the likelihood of smartphone addiction. Other studies in the literature have similarly reported that individuals who use smartphones for extended periods are more likely to develop smartphone addiction [21]. Additionally, in our study, it was found that as the number of times participants checked their smartphones increased throughout the day, the level of smartphone addiction also increased. Similarly, Noyan et al. found in their study that most students checked their smartphones more than 40 times a day, and as the frequency of checking smartphones increased, the level of smartphone addiction also increased [22]. Frequent and prolonged use may lead to habitual behavior among students.

In our study, it was observed that the level of smartphone addiction was higher among participants who identified themselves as smartphone addicts, as expected. Similarly, in a study conducted by Noyan et al., students who self-identified as smartphone addicts were found to have higher levels of addiction [22]. In a study in South Korea, a significant relationship was also found between self-identification as a smartphone addict and the level of addiction [23]. It can be said that those who identify themselves as smartphone addicts are aware of being at risk for addiction.

Some studies in the literature indicate that excessive smartphone use can lead to consequences such as social withdrawal, depression, and a decrease in social relationships [24, 25]. In our study, interviews with students revealed opinions suggesting that excessive smartphone use could lead to loneliness and depression in individuals. However, there were also students who expressed the opinion that smartphone use could contribute to socialization.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, home quarantine and social distancing measures have increased anxiety levels and the prevalence of negative emotions in society [26]. To cope with these negative emotions, individuals may have engaged in potentially addictive behaviors, such as excessive smartphone use, social media browsing, and playing video games, as a way to alleviate stress [27].

In our study, all participants reported that the pandemic and online education process increased smartphone and social media use. This increased usage, which could reach addictive levels, was associated with negative mood states. Lepp et al. found that students perceive their smartphones as entertainment devices, and over time, smartphone use becomes a habit [28]. Similarly, in our study, students mentioned reasons such as the opportunities provided by smartphones, boredom, social isolation, and escapism from daily life as causes of smartphone addiction. They described smartphone addiction as a habit, an inability to live without their phones, and spending excessive amounts of time on them.

The excessive use of smartphones, especially during classes, due to various entertainment content such as social media applications, negatively affects students’ academic performance [29]. Similarly, in our study, during qualitative interviews, some students mentioned that smartphones, by distracting them and causing them to waste time, had a negative impact on their studies. However, there are also studies that report no relationship between academic success and smartphone addiction [2].

Studies have indicated that men primarily use the internet for online gaming, while women use it for sending messages, chatting, and blogging [30, 31]. In our study, the most commonly expressed purpose of smartphone use, according to interviews with students, was for social media and communication. Following this, the use for academic purposes and watching TV series and movies was mentioned.

A study in Saudi Arabia found that approximately 33.8% of participants complained of physical pain in the wrist, back, or neck [32]. Thomée et al. reported in their study that prolonged smartphone use could negatively affect sleep and cause headaches [33]. Another study suggested that excessive smartphone use could cause pain in the thumb and impair hand function [34]. In our study, students reported negative physical effects of smartphone use, such as a decrease in sleep quality, visual impairment, and headaches.

A systematic review showed that university students have higher depression rates than the general population [35]. The prevalence of depression in university students was reported as 27.1% in the study by Bayram et al. [36], 26.2% in the study by Bostancı et al. [37] conducted with all university students in Denizli, and 33.0% in the study by Sarokhani et al. [38]. In our study, the prevalence of depression in university students was found to be 30.9%, which is consistent with the literature.

Smartphone use can function as an experiential avoidance strategy to escape from negative mental states [39]. Depressive individuals have been found to use their smartphones as a coping strategy to deal with their negative emotions [5]. When smartphone use is moderate, it can contribute to the improvement of emotional and psychological health and reduce stress levels [40]. In our study, participants expressed that individuals in depression may turn to smartphones to escape from real-world problems and increase smartphone use, contributing to the development of addiction.

Smartphone addiction shares many characteristics with substance abuse disorders and behavioral addictions, and individuals at risk of smartphone addiction are thought to have similar characteristics to those at risk of other addictions [41]. Additionally, smartphones facilitate not only work and education but also leisure time. Therefore, smartphone addiction poses a greater public health problem than substance use and internet gaming disorders. Sohn et al. found that approximately 1 in 4 children and adolescents in their study exhibited problematic smartphone use behavior, reflecting a behavioral pattern indicative of behavioral addiction. The younger population is more vulnerable to psychopathological developments, and harmful behaviors and mental health conditions formed at a young age can shape later life stages [42].

In addition, excessive use of smartphones may negatively impact individuals’ social support networks and increase susceptibility to depression [43]. In our study, some participants reported that smartphone use could lead to loneliness, while others believed that the negative effects of social media could contribute to depressive feelings. Similarly, there are studies indicating that levels of smartphone addiction are associated with increased levels of depression [44–46]. It can be suggested that, due to situations such as withdrawing into oneself and avoiding socialization in the case of depression, dependence on virtual environments and smartphones may increase. An individual in a depressive state may seek relief and become dependent on the smartphone, even if they overcome the depressive state, leading to continued dependency [47]. The findings of this study are consistent with previous research on the relationship between excessive smartphone use and depression. The results indicate that as smartphone addiction levels and the time spent on smartphones increase, depression levels also increase, revealing a relationship between depression and smartphone addiction. In our study, participants who perceived themselves as smartphone addicts had higher levels of depression than others. According to these findings, individuals at risk for smartphone addiction may also need to be evaluated for depression. Considering that smartphone use is now a societal norm, preventing addiction is challenging; however, awareness of the risks of smartphone addiction among parents, teachers, and healthcare providers can help limit exposure. Finally, more research is needed to clarify the magnitude of the contribution of smartphone addiction to the increasing burden of mental health problems among young people and to prevent its potential long-term, widespread, and harmful effects on the mental health and well-being of current and future generations.

Limitations and strengths

The results of the study rely on self-reported data. This may cause some response biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias, which could affect the accuracy of the results. The quantitative section of the study has a cross-sectional design, limiting its ability to draw causal inferences about the relationship between smartphone addiction and depression. There is a need for longitudinal studies to explore these variables over time. The data, obtained through student self-reports without clinical examination, may not be generalized to all students, as participants are exclusively from the health sciences field. Moreover, a gender imbalance with a female majority exists in our study. Future studies could include university students from non-health-related fields and aim for a more balanced gender distribution. Finally, although the questionnaires used to evaluate depression and smartphone addiction are valid scales, they may not fully reflect all the aspects of these problems in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While exploring the relationship between depression and smartphone addiction, the study’s strength lies in presenting data from a broad perspective, including sociodemographic, friendship, and smartphone-related variables. Additionally, the study findings, obtained using valid and reliable scales in the university student population, contribute to its robustness.

Conclusion

The prevalence of smartphone addiction among the participating students in the study was found to be 29.8%, while the prevalence of depression was 30.9%. Instances where self-perceived smartphone addiction, high scores on the SAS-SV, and elevated scores on the BDI coincided suggest a potential interaction between smartphone addiction and depression. This indicates the potential benefit of assessing and addressing both conditions simultaneously. Qualitative interviews with 12 participants revealed unanimous reports of the negative impact of the pandemic and online education on smartphone usage during the quarantine period. Some participants expressed concerns that smartphone use could lead to social isolation, while others attributed depressive feelings to the adverse effects of social media. Interestingly, some participants emphasized that the impact depends on how individuals use their phones.

This study provides critical findings for planning target-specific university policies to reduce smartphone addiction among students. For example, implementing awareness campaigns and workshops about smartphone use at universities or at non-university events accessible to students may help students develop healthier habits. Furthermore, the results of this study emphasize the need for mental health interventions that take into account the effects of behavioral addictions on academic performance and general well-being. Adding digital awareness programs to university curricula can create a more efficient and effective learning environment by improving students’ digital literacy and providing digital detox initiatives.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants in this study.

Abbreviations

- SAS-SV

Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

Author contributions

In this study, the authors’ roles and contributions were as follows: MKA and AT were responsible for conceptualizing the study and developing the methodology. MKA carried out the data collection. MKA, AT and ZMA were involved in the initial drafting of the paper and the final manuscript. MKA and ZMA conducted the data analysis. All authors thoroughly reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organization.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The research obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Marmara University Faculty of Medicine under protocol code 09.2020.300 on March 6, 2020. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Griffiths M. Gambling on the internet: A brief note. J Gambl Stud. 1996;12(4):471–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matar Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students- A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton RB, Leshner G, Almond A. The extended iSelf: The impact of iPhone separation on cognition, emotion, and physiology. J Computer-Mediated Communication. 2015;20(2):119–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(2):85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J-H, Seo M, David P. Alleviating depression only to become problematic mobile phone users: Can face-to-face communication be the antidote? Comput Hum Behav. 2015;51:440–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Karila L, Billieux J. Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4026–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Li A, Zhu T, Liu X, Liu X. How smartphone usage correlates with social anxiety and loneliness. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan JL. Prevention of depression in the college student population: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;26(1):21–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eller T, Aluoja A, Vasar V, Veldi M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in Estonian medical students with sleep problems. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(4):250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Glazebrook C. Reliability of a shortened version of the Zagazig Depression Scale and prevalence of depression in an Egyptian university student sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(5):638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmoud JS, Staten R, Hall LA, Lennie TA. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(3):149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castaldelli-Maia JM, Martins SS, Bhugra D, et al. Does ragging play a role in medical student depression - cause or effect? J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smetaniuk P. A preliminary investigation into the prevalence and prediction of problematic cell phone use. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(1):41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon M, Lee JY, Won WY, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hisli N. Beck Depresyon Envanterinin gecerliligi uzerine bit calisma (A study on the validity of Beck Depression Inventory). Psikoloji Dergisi. 1988;6:118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen B, Liu F, Ding S, Ying X, Wang L, Wen Y. Gender differences in factors associated with smartphone addiction: a cross-sectional study among medical college students. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De-Sola Gutiérrez J, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Rubio G. Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KE, Kim SH, Ha TY, et al. Dependency on Smartphone Use and Its Association with Anxiety in Korea. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(3):411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aljomaa SS, Qudah MFA, Albursan IS, Bakhiet SF, Abduljabbar AS. Smartphone addiction among university students in the light of some variables. Computers Hum Behav. 2016;61:155–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii K. Examining the adverse effects of mobile phone use among Japanese adolescents. Keio Communication Rev. 2011;33(33):69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noyan CO, Darçin AE, Nurmedov S, Yilmaz O, Dilbaz N. Akilli Telefon Bagimliligi Ölçeginin Kisa Formunun üniversite ögrencilerindeTürkçe geçerlilik ve güvenilirlik çalismasi/Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version among university students. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2015;16:73. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon M, Kim D-J, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83558. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiscock D. Cell phones in class: This, too, shall pass. Community Coll Week. 2004;16(16):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.James D, Drennan J, editors. Exploring addictive consumption of mobile phone technology. Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy conference, Perth, Australia; 2005.

- 26.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnaire C, Baptista D. Internet gaming disorder in male and female young adults: The role of alexithymia, depression, anxiety and gaming type. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lepp A, Barkley JE, Karpinski AC. The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers Hum Behav. 2014;31:343–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Attamimi A, editor. The reasons for the prevalence of BlackBerry cellphones and the resulting educational effects from the perspective of secondary school students in Abo-Dhabi. Conference on the negative effects of cellphones on secondary school students, UAE; 2011.

- 30.Choi SW, Kim DJ, Choi JS, et al. Comparison of risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and Internet addiction. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(4):308–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heo J, Oh J, Subramanian SV, Kim Y, Kawachi I. Addictive internet use among Korean adolescents: a national survey. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alhassan AA, Alqadhib EM, Taha NW, Alahmari RA, Salam M, Almutairi AF. The relationship between addiction to smartphone usage and depression among adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomée S. Mobile Phone Use and Mental Health. A Review of the Research That Takes a Psychological Perspective on Exposure. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.İnal EE, Demİrcİ k, Çetİntürk A, Akgönül M, Savaş S. Effects of smartphone overuse on hand function, pinch strength, and the median nerve. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(2):183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(8):667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bostanci M, Ozdel O, Oguzhanoglu NK, et al. Depressive symptomatology among university students in Denizli, Turkey: prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Croat Med J. 2005;46(1):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarokhani D, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sarokhani MT, Manesh RE, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of Depression among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Depress Res Treat. 2013; 2013:373857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Machell KA, Goodman FR, Kashdan TB. Experiential avoidance and well-being: a daily diary analysis. Cogn Emot. 2015;29(2):351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park N, Lee H. Social implications of smartphone use: Korean college students’ smartphone use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(9):491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YH, Chiang CL, Lin PH, Chang LR, Ko CH, Lee YH, Lin SH. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Smartphone Addiction. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0163010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sohn SY, Rees P, Wildridge B, Kalk NJ, Carter B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daysal B, Yılmazel G, editors. Kırsaldakı Adolesanlarda Akıllı Telefon Bağımlılığı Ve Psikososyal Faktörler. 3 International 21 National Public Health Congress; 2019.

- 44.Haug S, Castro RP, Kwon M, Filler A, Kowatsch T, Schaub MP. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(4):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Eijnden RJ, Meerkerk GJ, Vermulst AA, Spijkerman R, Engels RC. Online communication, compulsive Internet use, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents: a longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(3):655–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yen JY, Cheng-Fang Y, Chen CS, Chang YH, Yeh YC, Ko CH. The bidirectional interactions between addiction, behaviour approach and behaviour inhibition systems among adolescents in a prospective study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):588–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karahancı P. Üniversite öğrencilerinde akıllı telefon bağımlılığı ile kişilik özellikleri arasındaki ilişki. İstanbul Gelişim Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü; 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.