Abstract

We report a stereo-differentiating dynamic kinetic asymmetric Rh(I)-catalyzed Pauson–Khand reaction, which provides access to an array of thapsigargin stereoisomers. Using catalyst-control, a consistent stereochemical outcome is achieved at C2—for both matched and mismatched cases—regardless of the allene-yne C8 stereochemistry. The stereochemical configuration for all stereoisomers was assigned by comparing experimental vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) and 13C NMR to DFT-computed spectra. DFT calculations of the transition-state structures corroborate experimentally observed stereoselectivity and identify key stabilizing and destabilizing interactions between the chiral ligand and allene-yne PKR substrates. The robust nature of our catalyst-ligand system places the total synthesis of thapsigargin and its stereoisomeric analogues within reach.

Introduction

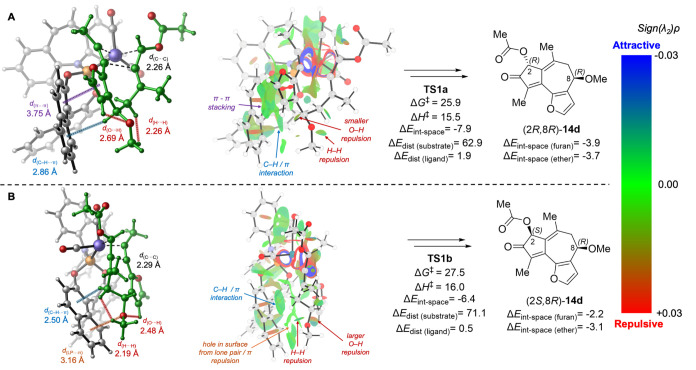

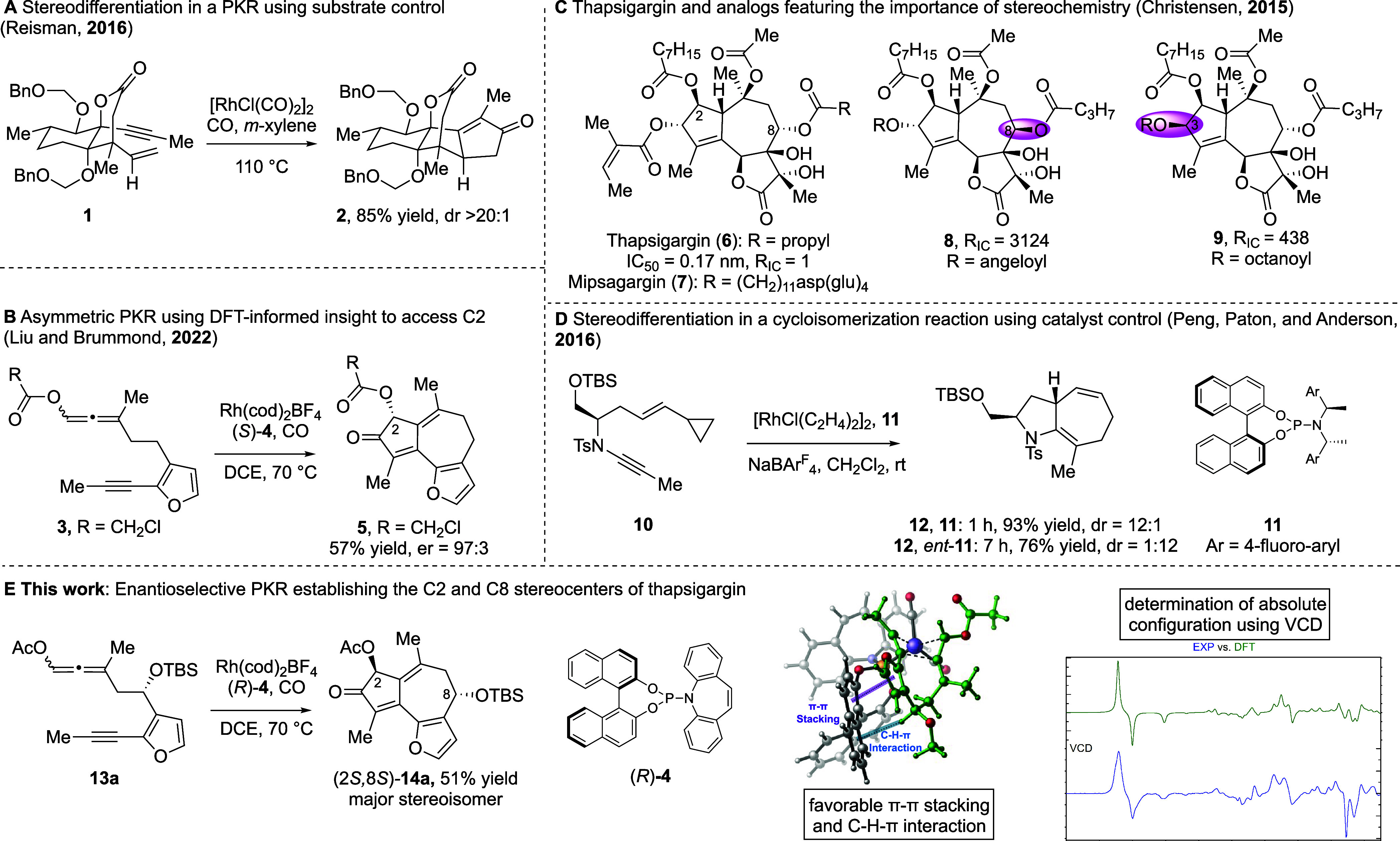

The transition metal-catalyzed Pauson–Khand reaction (PKR) is a powerful method for synthesizing ring-fused cyclopentenones—an unsaturated motif found in complex molecular targets and which often bears stereogenic centers.1−4 For substrates with at least one preset stereocenter, high diastereoselectivity is often observed in the PKR.5−8 Reisman and coworkers recently reported an elegant example of this type of substrate-controlled stereodifferentiation of enyne 1 via a Rh(I)-catalyzed PKR to give cyclopentenone 2 in 20:1 dr; product 2 was then utilized to complete the total synthesis of (+)-ryanodol (Figure 1A).9 Yet, asymmetric catalyst-controlled PKRs have rarely been applied to natural product synthesis,10 despite the prevalence of chiral nonracemic 5,5-, 5,6-, and 5,7-ring systems in these targets. Further, the PKR is a mechanistically complex reaction, with both precursor structure and the steric and electronic properties of the catalyst impacting reactivity and selectivity. Still, the absence of a catalyst-controlled asymmetric PKR represents a serious omission in the synthetic chemist’s toolbox.

Figure 1.

(A) Stereodifferentiation using substrate control; (B) DFT-informed asymmetric PKR; (C) thapsigargin and analogues, highlighting key stereochemical sites; (D) stereodifferentiation using catalyst control; (E) this work: stereodifferentiation in a DyKAT-based asymmetric PKR and access to stereoisomeric analogues of thapsigargin.

In 2017, we utilized a combination of experiment and computational modeling to establish that racemic allene-ynes could be converted into bicyclo[5.3.0]decadienone products in high yield and good enantiomeric ratios (ers) through an enantioselective Rh(I)-catalyzed PKR.11 This stereoconvergent transformation relies on the rapid scrambling of the allenyl carboxy group’s axial chirality under the reaction conditions, facilitating the selective PKR of one enantiomer of the substrate. By utilizing the computed reaction energy profile to establish the oxidative cyclization step as stereodetermining, an effective chiral catalyst was identified in which the corresponding transition state contained a low-energy five-coordinate rhodium complex. The computationally derived mechanistic insights into ligand effects on reactivity and selectivity (e.g., ΔG‡ and ΔΔG‡) were iteratively correlated with experimental data (e.g., yield and enantioselectivity) to inform further reaction design.

Recently, we extended this chiral-catalyzed method to more complex furan-containing allene-ynes to afford 5,7,5-ring systems—an ever-present substructure in natural products (Figure 1B).12 Application to the total synthesis of thapsigargin (6) offers a high-impact and exciting target for asymmetric PKR technology. Thapsigargin (6) is one of the most stereochemically complex members of the 6,12-guaianolide sesquiterpene family. Further, thapsigargin is a potent inhibitor of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) and has recently shown antiviral activity against the replication of human coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2.13−16 Mipsagargin (7), a prodrug of thapsigargin, has been used in several phase II clinical studies.17,18 While over a hundred thapsigargin analogues have been reported, and a pharmacophore model for SERCA inhibition postulated, previous studies utilized only two thapsigargin stereoisomers, the C8-inverted isomer 8 and C3-inverted isomer 9, each of which is less bioactive than thapsigargin itself (RIC = 3124 and 438, respectively) [RIC = IC50(analogue)/IC50(thapsigargin)] (Figure 1C).19−21

To date, total syntheses of thapsigargin have used a chiral pool starting material.22−24 While chiral pool materials are readily available in known stereochemical configuration, they can be expensive and often require significant modification to reach the desired target.25−28 Chiral catalysis offers a more direct synthetic route; yet, there are only three reported asymmetric syntheses of any guaianolide natural product that do not depend on a chiral pool starting material. Of these, two involved asymmetric C–C bond forming processes ([4 + 3]29 or [2 + 1]-cycloaddition30), and the other utilizes a sharpless asymmetric epoxidation.31

Herein, we report our asymmetric PKR approach to thapsigargin, which establishes the absolute stereochemistry of C8 early. While C8 is four bonds away from the stereogenic carbon introduced by the PKR, DFT-computed transition-state (TS) structures place the chiral biaryl backbone of the phosphoramidite ligand in the proximity of the C8 substituent. As such, the absolute configuration of the C8 stereogenic center interacts noncovalently with the phosphoramidite ligand, impacting the overall transition state stability and stereochemical outcome of the PKR (Figure 1E).

Inspired by Peng, Paton, and Anderson who used insights from their DFT calculations to achieve a double stereo-differentiating Rh(I)-catalyzed [5 + 2] carbocyclization for both matched and mismatched cases (Figure 1D),32 we asked whether the chiral catalyst, optimized previously for a model system, could be used in a stereoconvergent, stereo-differentiating PKR aimed at thapsigargin. Herein, we report a rare example of a DFT-informed, enantioselective dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DyKAT) that utilizes the existing C8 stereocenter of the allene-yne 13 to initiate an asymmetric catalyst-controlled PKR. This approach provides access to the full stereochemical array of chiral nonracemic thapsigargin isomers, none of which are available from chiral pool starting materials or semisynthesis (Figure 1E).33 Access to these thapsigargin stereoisomers will enable important structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies and a broader understanding of thapsigargin’s biological mode of action.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Racemic and Nonracemic C8-Substituted Chiral Allene-yne Precursors

Installation of the C8 Stereogenic Center of Thapsigargin (6)

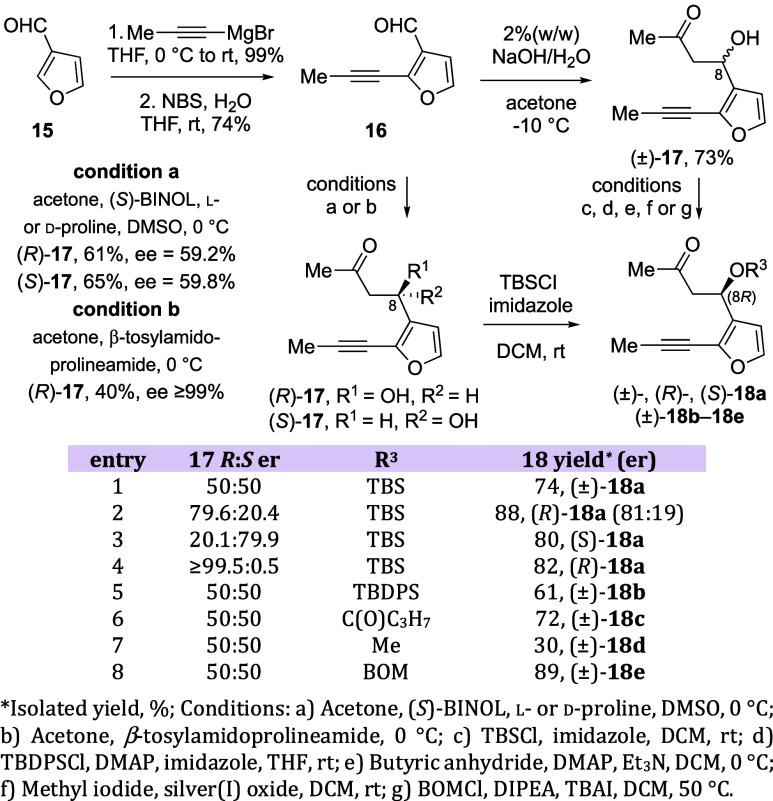

Reacting 3-furfural (15) with propynyl magnesium bromide, followed by treatment with N-bromosuccinimide and water, yielded oxidative rearrangement product 16 in 74% yield over two steps (Scheme 1).12 Subsequent three-carbon homologation of aldehyde 16 with concomitant installation of the C8 stereocenter was then accomplished using either an asymmetric aldol reaction (only a few examples use heteroaryl aldehydes, but there are no reports with 3-furaldehyde34−47) or a nonstereoselective reaction (acetone and 2% (w/w) aqueous sodium hydroxide).48

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Aldol Adducts 18a–18e.

To prepare enantioenriched ketone 17, aldehyde 16 was reacted with acetone in the presence of (S)-BINOL and either l- or d-proline (Scheme 1). Reaction with l-proline produced product (R)-17 in 61% yield and 59.2% enantiomeric excess (ee), while d-proline gave ketone (S)-17 in 65% yield and 59.8% ee, as determined by 1H NMR using Eu(hfc)3 as a chiral shift reagent (see Supporting Information for asymmetric aldol reaction optimization studies).49 Both chiral shift reagents and chiral HPLC analysis showed the same % ee for enantioenriched ketone 17.

Given the mixture of stereoisomers formed during this process, we wondered whether epimerization of the C8 stereocenter could occurr under the (S)-BINOL/proline conditions. As such, aliquots were obtained at two time points (early in the reaction and at completion of the reaction) and analyzed by 1H NMR using Eu(hfc)3 as a chiral shift reagent. These studies found no significant change in the enantiomeric ratio of product 17 over time (see Supporting Information), suggesting that the observed enantioselectivity resulted from the reaction itself rather than a subsequent epimerization.

Interestingly, when β-tosylamidoprolineamide, a 1,2-diamine-based bifunctional prolineamide catalyst, was used instead of the (S)-BINOL/proline system,50 ketone (R)-17 was obtained in ≥99% ee. The easy accessibility of the proline catalyst and scalability of the reaction provided adequate material to be tested for stereoselectivity in the PKR in our early investigations.

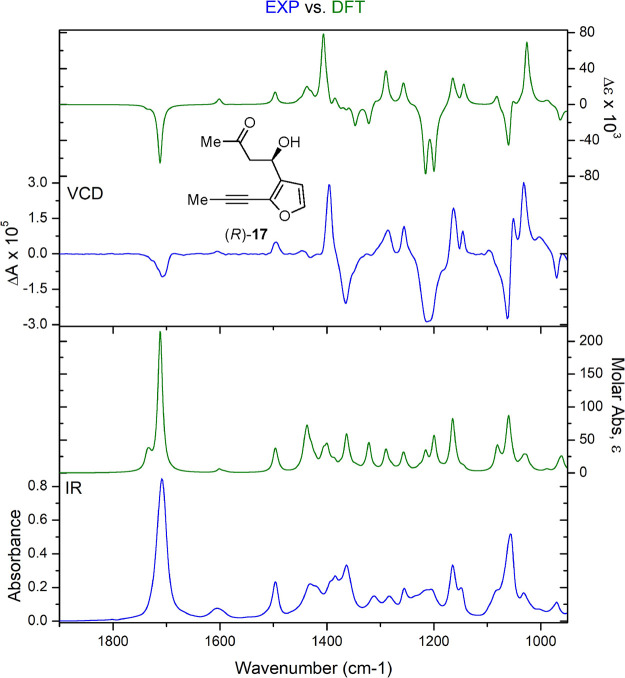

Establishing the Absolute Configuration of Both Enantiomers of Ketone 17

Vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) was used to determine the absolute configuration of the ketone 17 enantiomers, given that product 17 is an oil and VCD can be performed on solutions.51−56 Moreover, VCD has been established as a reliable tool for assigning the absolute configuration of more than 300 natural products.57 In the process, we noted that ketone 17 is sensitive to dehydration, and care needed to be taken to remove all acid from the CDCl3 solvent before dissolution. In acid-free CDCl3, no changes were observed in the IR or VCD spectra over time.

The experimental VCD data for enantiomers (R)-17 and (S)-17 were compared to DFT-calculated IR and VCD spectra using CompareVOA software (BioTools, Jupiter FL) to quantify the results. In both cases, a high Sfg (overlap) value was observed for IR and VCD (confidence level = 99%, Figures 2 and S9, S10).58,59 The analysis included an initial search with MMFF94 yielding 28 conformers (within a 7.0 kcal/mol energy window), which were further optimized using two different basis sets (6-31G(d) and cc-pVTZ) each with two functionals (B3LYP and B3PW91). While the absolute configuration could be determined using any of the calculation methods, the larger cc-pVTZ basis set represented the data most accurately. In that case, the lowest energy conformer (B3LYP/cc-pVTZ—used in plots) represented 73% of the Boltzmann weighted average and showed an intramolecular H-bond between the hydroxyl group and the carbonyl oxygen, suggesting that a H-bond is present in CDCl3 solution. Using Goodman’s metric, a Cai•factor (configuration: absolute information) of 61 was measured for (R)-17, a high score indicating confident assignment of absolute stereochemistry (Figure S11).60 Importantly, the assigned absolute configuration aligns well with the predictive model for the organocatalyzed aldol reaction, with the enamine intermediate of l-proline showing a re-facial approach of acetone to aldehyde 16 through a half-chair transition state that leads to ketone (R)-17 as the major enantiomer.61−63

Figure 2.

DFT-calculated (green) and experimental (blue) VCD and IR spectra of ketone (R)-17.

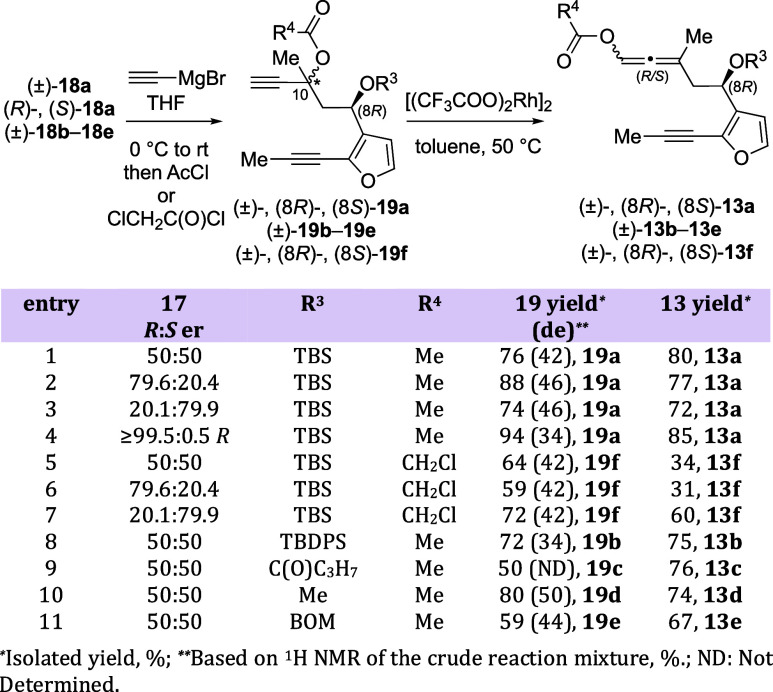

Synthesis of Allene-yne Precursors 13a–f

As we knew that the steric nature of the pre-existing C8 stereocenter of the allene-yne would be important for the DyKAT PKR process, the C8 hydroxyl group was protected as a tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether (R1 = TBS), a tert-butyldiphenylsilyl ether (R1 = TBDPS), a butanoyl ester (R1 = C(O)C3H7), a methyl ether, or a benzyloxymethyl ether (Scheme 1). In the racemic case, protected hydroxy ketones (±)-18a–18e were formed in 30–89% yield. Enantioenriched/pure (R)- and (S)-18a were obtained in 80–88% yield. The enantioenriched (R)-18a was obtained with 62% ee as determined by 1H NMR using Eu(hfc)3 as a chiral shift reagent.

Conversion of methyl ketones 18a–18e into the required allene was accomplished using a 3-step/2-pot protocol (Scheme 2). The initial reaction of each ketone 18a–18e with ethynylmagnesium bromide provided propargyl alcohols that were trapped in situ with either acetyl chloride or chloroacetyl chloride to afford diynes (±)-19a–19f in 50–80% yield. Enantioenriched/pure (R)- and (S)-19a and 19f were obtained under similar reaction conditions in 59–94% yield and 34–46% diastereomeric excess (de). Finally, treatment of diynes 19a–19f with 5 mol % Rh(II) trifluoroacetate dimer at 50 °C gave racemic allene-ynes (±)-13a–13f in 34–80% yield and 0% de. Enantioenriched/pure (R)- and (S)-13a and 13f were obtained in 31–85% yield and 0% de.12 The mixture of diastereomers is inconsequential at this point, as the axial chirality of the allenyl carboxy group is rapidly scrambled in the asymmetric PKR.11 If an Rh scavenger (SiliaMetS Thiourea) was added to the mixture upon completion of the reaction, improved yields could be achieved (Scheme 2, compare entries 5 and 6 with entry 7). Because the ees for compounds 17a and 18a (59.2% vs 62%) are nearly identical, we assume that the ees for 19a, 19f, 13a, and 13f are unchanged from 17. This rationalization is further supported by the kinetic resolution studies shown below (Figure 6).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Allene-yne Precursors 13a–13f.

Figure 6.

Absence of kinetic resolution in PKR of allene-yne 13a.

Rh(I)-Catalyzed Racemic PKR of (±)-13a–13e

With racemic allene-ynes 13a–13e in hand, we sought to determine the effect of the C8 group on the yield and diastereoselectivity of the PKR in the presence of an achiral or racemic Rh(I)-catalyst.12 Reaction of OTBS-substituted (±)-13a with cationic [Rh(cod)2BF4] and triphenyl phosphine in DCE (0.02 M) under a carbon monoxide atmosphere at 70 °C for 112 h afforded the PKR product (±)-14a in 42% yield and −26% de in favor of the cis diastereomer, as determined by 13C NMR (Table 1, entry 1). Attempts to increase the reaction concentration from 0.02 to 0.1 M gave complete consumption of (±)-13a in 20 h, but a 26% yield of (±)-14a due to the competing formation of aldehyde side product S8 (entry 2). Subjecting OTBDPS-substituted allene-yne (±)-13b to the reaction conditions provided (±)-14b in 60% yield and −42% de (entry 3), while butanoyl (±)-13c gave (±)-14c in 53% yield and −34% de (entry 4).64 The methoxy-substituted allene-yne (±)-13d gave a 15% yield of (±)-14d in −16% de (entry 5). We hypothesized that having a BOM ether at the C8 position would improve the selectivity of the PKR due to π–π interactions between the substrate and the ligand in the oxidative cyclization transition state. However, (±)-13e gave (±)-14e in 33% yield and −20% de, which was similar to that observed for the OMe group (compare entries 5 and 6). Although the effect of the C8 group on diastereoselectivity is subtle (16–42% de), the larger groups show increasing cis:trans ratios (entries 1–6). The diastereoselectivity corresponds to the size of the silyloxy group, rather than its A-value (A values: OTBS = 1.06–1.77; OTBDPS = 0.56–0.62 kcal/mol).65 Interestingly, the size of the C8 group had a greater impact on the reaction yield, with (±)-14b (R = OTBDPS) provided in 60% yield and (±)-14d (R = OMe) in 15% yield. Lower yields for the products having smaller groups may be due to the C8 oxygen coordinating to the cationic Rh(III) of the catalyst reaction center, facilitating hydrolysis of the allenyl carboxy group and leading to an increase in the level of side product S10.

Table 1. Influence of the C8-Substituent on the Yield and Diastereoselectivity of Rh(I)-Catalyzed PKR Using Achiral or Racemic Catalysts and Allene-ynes (±)-13a–e.

| entry | allene-yne | R3 | deviation fromstandard condition | timein h | isolated combined yield14 (NMR yield) % | trans: cis14a(de %) | 14: aldehydea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (±)-13a | TBS | - | 112 | 42 (36) | 37:63 (−26) | 91:9 |

| 2 | (±)-13a | TBS | 0.1 M | 20 | 26 (38) | 33:66 (−33) | 56:44 |

| 3 | (±)-13b | TBDPS | no internal standard | 51 | 60 | 29:71 (−42) | 94:6 |

| 4 | (±)-13c | C(O)C3H7 | no internal standard | 168 | 53 | 33:67 (−34) | b |

| 5 | (±)-13d | CH3 | - | 45 | 15 (22) | 42:58 (−16) | 67:33 |

| 6 | (±)-13e | BOM | no internal standard | 140 | 33 | 40:60 (−20) | 81:19 |

| 7 | (±)-13a | TBS | (±)-4 (30 mol %), 0.01 M | 165 | 40 (26) | 60:40 (20) | 83:17 |

| 8 | (±)-13a | TBS | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (10 mol %), CO:Ar (10:90, 1 atm), toluene (0.02 M) 110 °C, no internal standard | 48 | c | 50:50 (0) | b |

| 9 | (±)-13a | TBS | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (40 mol %), CO:Ar (10:90, 1 atm), toluene-d8 (0.02 M), 110 °C, mesitylene (1 equiv) | 73 | d(7) | 58:42 (16) | b |

Ratio based on 1H NMR of crude reaction mixture, all reactions were stopped when no SM remained.

Trace aldehyde.

The percent conversion is 9% based on the ratio of 13a:14a (91:9) determined by the integration of the 1H NMR peaks at 6.59 and 6.39 ppm.

The percent conversion is 17% based on the ratio of 13a:14a (83:17).

While these results suggest that both the substrate and catalyst affect the diastereoselectivity of the PKR, the catalyst dictates which diastereomer is formed as the major product. For example, when triphenylphosphine was used as the ligand, the major product was (±)-cis-14a (entry 1), whereas with (±)-MonoPhos-alkene 4, the trans isomer of product 14a was favored (entry 7). Interestingly, when allene-yne 13a is treated with neutral rhodium biscarbonyl chloride dimer [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (0.05 equiv) and only CO is available as the ligand, the reaction stalls at 9% conversion, and no diastereoselectivity is observed (entry 8). However, when the catalyst loading was increased to 0.2 equiv under the same conditions, the reaction favored the formation of the trans isomer, if only slightly, yet still gave a low % conversion (entry 9). Thus, the dr values for the CO and (±)-MonoPhos-alkene ligands are similar, and the stereoselectivity for triphenylphosphine is the opposite of that of the (±)-MonoPhos-alkene ligand, with neither showing a strong preference for either the cis or trans product.

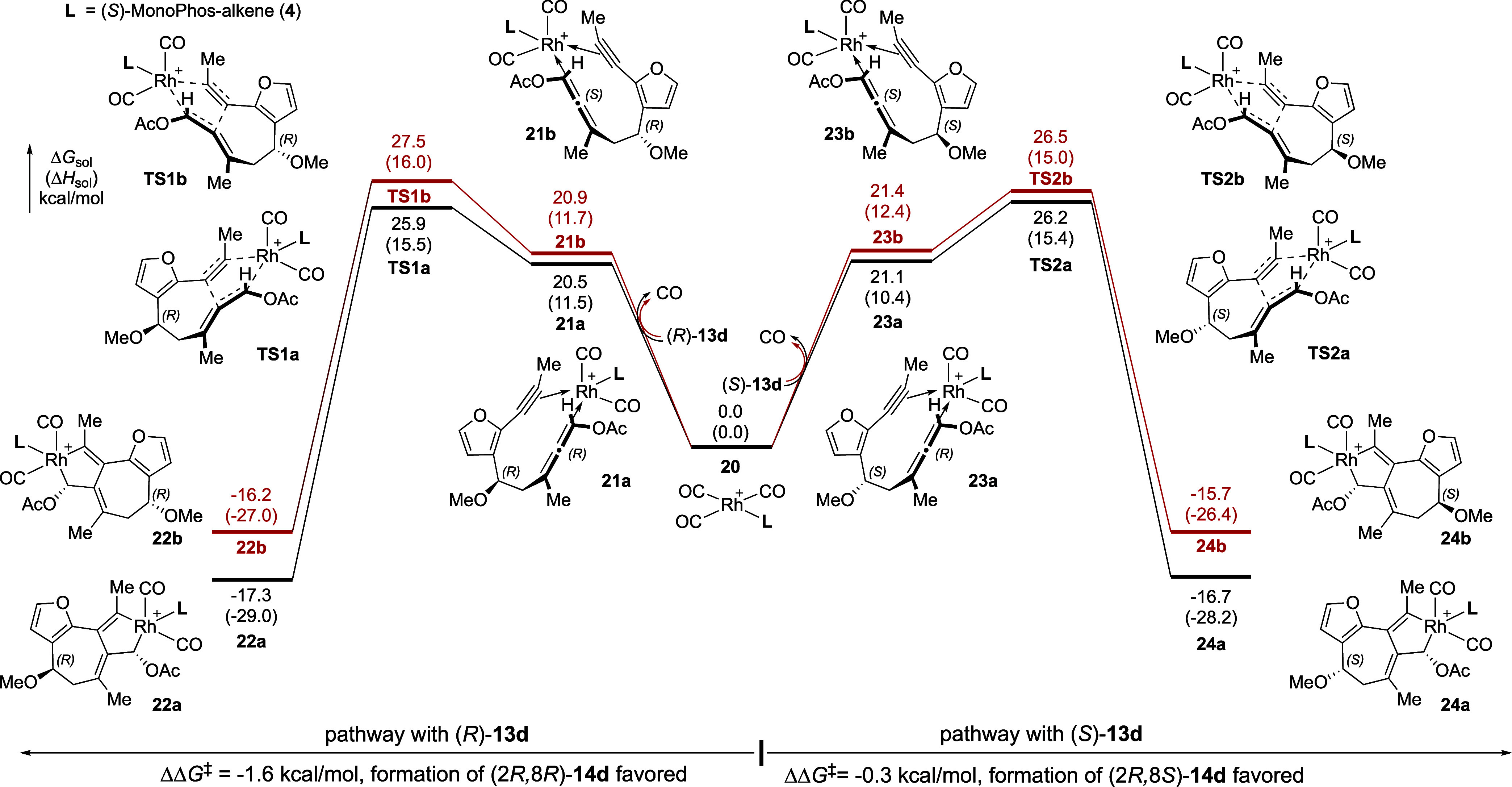

Computed Transition States for the Stereo-Determining Oxidative Cyclization Step of PKR with 13d

As we have previously established oxidative cyclization as an irreversible and enantioselectivity-determining step in Rh(I)-catalyzed PKR of allene-ynes,11,12 we evaluated this step computationally (see computational SI for details of the DFT calculations) for the methoxy-substituted model compound 13d to determine how the relative transition-state energies of this step might impact the overall reaction diastereoselectivity. Beginning with the phosphoramidite (S)-MonoPhos-alkene (4)-supported Rh(I) tricarbonyl complex (20), ligand exchange with either allene-yne (8R)-13d (left pathway, Figure 3) or (8S)-13d (right pathway) forms four different five-coordinate Rh complexes (21a–b, 23a–b), each exhibiting a different prochiral π-face of the allene and the alkyne chelating to the Rh center. Although the substrate binding process is endergonic by 20–22 kcal/mol for both (8R)- and (8S)-13d, the equilibration to form allene-yne–rhodium complexes is promoted by the low concentration of dissolved CO.11,12 Subsequent oxidative cyclization (TS1a/b and TS2a/b) occurs via these five-coordinate complexes, as the alternative oxidative cyclization pathways (i.e., those involving four-coordinate allene-yne–rhodium complexes with ligand (S)-4 and one CO ligand) are ∼10 kcal/mol less favorable (see Figure S7).11,66 Additionally, the oxidative cyclization of allene-yne 13d with a rhodium tricarbonyl complex, in the absence of a phosphoramidite ligand, was found to be less favorable by ∼17 kcal/mol computationally (see Figure S8). For reactions with both (8R)- and (8S)-13d, oxidative cyclization favors Rh–C bond formation at the (Si)-face of the OAc-substituted allene terminus (TS1a and TS2a). This suggests that the PKR product 14d should exhibit catalyst-controlled (R)-stereochemistry at C2, as the pathways leading to product (S)-14d are predicted to be 1.6 and 0.3 kcal/mol higher in energy (TS1b and TS2b, respectively). Formation of the Rh(III) metallocycles 22a–b and 24a–b are exergonic by 15–18 kcal/mol relative to complex 20, consistent with previous findings that the oxidative cyclization is irreversible and stereo-determining.

Figure 3.

Computed reaction energy profiles for the oxidative cyclization of (R)- and (S)-13d with a (S)-MonoPhos-alkene (4)-supported Rh catalyst. DFT calculations were performed at the ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP/SMD(DCE)//B3LYP-D3/LANL2DZ-6-31G(d) level of theory.

Rh(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric PKR

We then sought to extend these predictions to the asymmetric PKR, focusing specifically on the impact of differing C8 functionality.12 Reaction of allene-yne (±)-13a with Rh(cod)2BF4 and ligand (S)-4 in DCE under a CO atmosphere (100%)67 at 70 °C afforded PKR product 14a in 33% yield and 20% de. High stereoselectivity was observed at C2 for the (8R)-14a isomers (91.5:8.5), and moderate selectivity was observed for the (8S)-14a isomers (82.4:17.6), as determined by chiral HPLC (Table 2, entry 1). Reaction of TBDPS-substituted allene-yne (±)-13b with ligand (S)-4 mirrored these results, providing product 14b in 44% yield (de = 24%) and ers of 92:8 and 76:24 (entry 6). The reaction of methoxy allene-yne 14d with ligand (S)-4 gave 14d in 28% yield (de = 4%) and er values of 86.2:13.8 and 82.5:17.5. Similarly, the reaction of BOM-substituted allene-yne 14e gave access to 14e in 26% yield (de = 8%) and ers of 86:14 and 79:21. While the des for 14d and 14e were lower than those for the larger silyloxy groups, the ers were similar across the series (compare entries 1 and 6–8).

Table 2. Asymmetric PKR on Allene-ynes 13: Influence of the C8-Substituent and Chirality on the dr and er.

In all cases, the (R) configuration was favored at C2 when using (S)-4, regardless of the C8 configuration, confirming our computational predications. In accord with these studies, (2R,8R)-14a, -14b, -14d, and -14e and (2R,8S)-14a, -14b, -14d, and -14e, arising from TS1a and TS2a, respectively, were observed as the major stereoisomers.

In order to obtain a reliable isolated yield, we next performed the reaction on a larger scale (0.3 mmol vs 0.05 mmol) using 13a enriched in the (8R) isomer (59.2% ee). By treating the crude reaction mixture with polymer-bound PPh3 to remove the Rh catalyst prior to workup and purification, product 14a could be isolated in 49% yield and 64% de (entry 2). Allene-yne (8R)-13a provided (8R)-14a in 92.1:7.9 er, as determined by chiral HPLC, while (8S)-13a gave the isomer (8S)-14a in 83.9:16.1 er (entry 2). Similarly, the reaction of enantioenriched (S)-13a (59.8% ee) with (R)-4 afforded 14a in 51% yield, 54% de, and ers of 12.2:87.8 and 7.8:92.2, favoring the (2S,8S) stereoisomer (entry 3). As thapsigargin possesses the same (2S,8S)-stereochemical pattern at C2 and C8, this stereoisomer is of particular interest. We attribute the differences in stereoselectivity to matched/mismatched interactions between the catalyst and substrate commensurate with the higher computed ΔΔG‡ value for (8R)-13d (1.6 kcal/mol) compared with that for (8S)-13d (0.3 kcal/mol), see the discussion below.

When enantiopure allene-yne (8R)-13a was treated with matched ligand (S)-4 under otherwise standard reaction conditions, product 14a was formed in 41% yield, 80% de, and 94.8:5.2 er (entry 4). In the mismatched case, enantiopure (8R)-13a was reacted with ligand (R)-4 to afford 14a in a lower yield and selectivity (29% yield, −48% de, and 22.1:77.9 er, entry 5). Under mismatched conditions, small amounts of the enantiomeric products were observed, possibly due to C8 epimerization under the Rh(I) reaction conditions, along with larger amounts of the aldehyde side product (14a:S8, 67:33 (entry 4) vs 50:50 (entry 5).

While this asymmetric dynamic kinetic PKR is operating under the predominantly catalyst control, we do observe the weak substrate control as evidenced by increased diastereomeric excess, in favor of the trans isomer, as the C8 group increases in size (OMe < OBOM < OTBS < OTBDPS) (Table 2, entries 1 and 6–8). As transition-state structures TS1b and TS2a place the C8-substituent proximal to the chiral ligand, we surmise that these transition states leading to the cis-products would be increasingly destabilized as the substituent at C8 becomes larger.

Matched and Mismatched Pairs

The higher C2 stereocontrol observed for (8R) over (8S) in the PKR of 13a, 13b, 13e, and 13f with (S)-4 suggests the presence of a matched and mismatched case between the substrate and the ligand (Table 2, entries 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 and Table S3, entries 2 and 4). Similarly, when ligand (R)-4 is utilized, the situation inverts, providing higher C2 stereoselectivity for (8S). Again, the more moderate C2 stereocontrol for (8R) suggests a mismatched case (entries 3 and 5). Therefore, (8R)-13/(S)-4 and (8S)-13/(R)-4 are matched pairs, and (8S)-13/(S)-4 and (8R)-13/(R)-4 are mismatched pairs. In the case of methyl-substituted allene-yne 13d, moderate stereoselectivity was observed for both matched and mismatched pairs, with slightly higher stereoselectivity being observed for the matched pairs (entry 7). In this way, the matched and mismatched cases can provide access to all four stereoisomers of product 14 in synthetically useful selectivity (for additional examples see Table S3, Entries 1–5 and Figure S1).

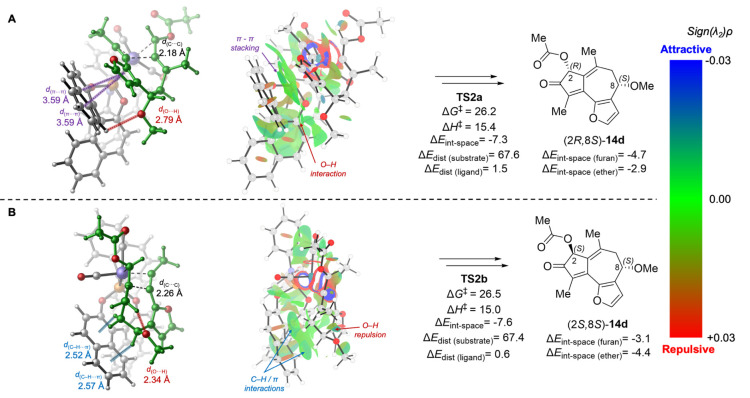

From the computed energy profiles of the oxidative cyclization with the (S)-4-supported Rh catalyst (Figure 3), the diastereoselectivity with allene-yne (8R)-13d (ΔΔG‡ = 1.6 kcal/mol) is higher than that with (8S)-13d (ΔΔG‡ = 0.3 kcal/mol), which agrees with the experimentally observed higher stereoselectivity with enantioenriched (8R)-allene starting materials (Table 2, entries 4 and 5). To better understand the origins of stereoselectivity and the matched and mismatched pairs in the asymmetric PKR, we calculated distortion and through-space interaction energies and then used NCIPlot to visualize the noncovalent interactions between the phosphoramidite ligand and allene-yne in the oxidative cyclization transition states (Figures S5 and S6, see computational Supporting Information for details). In particular, we sought to reveal what factors favor the formation of the (2R) stereocenter with both (8R)- and (8S)-13d and the higher diastereoselectivity with (8R)-13d. We calculated the overall through-space interactions between the MonoPhos-alkene ligand (S)-4 with the full allene-yne substrate (ΔEint-space) at the transition states, as well as with the furan and ether fragments of the substrate (ΔEint-space(furan) and ΔEint-space(ether), see computational Supporting Information for details). In addition, we calculated the distortion energies of the allene-yne substrate (ΔEdist(substrate)) and the phosphoramidite ligand (ΔEdist(ligand)) at the transition states with respect to their ground-state geometries (i.e., free substrate and free ligand).

Between the two oxidative cyclization transition states with (8R)-13d (TS1a and TS1b, Figure 4), the major difference is the orientation of the C8-OMe and furanyl substituents of the allene-yne substrate. In the lower energy transition state TS1a, the furanyl group points toward the phosphoramidite ligand, whereas C8-OMe is pointing away from the ligand. By contrast, in the less stable TS1b, where the Rh catalyst approaches from the opposite face of the allene-yne substrate, C8-OMe is pointing toward the phosphoramidite ligand and the furanyl group is pointing further away. This causes major differences in the ligand–substrate noncovalent interactions as well as the distortion of the allene-yne substrate itself. The overall through-space interaction energies (ΔEint-space = −7.9 and −6.4 kcal/mol for TS1a and TS1b, respectively) indicate that the noncovalent ligand–substrate interaction in TS1a is 1.5 kcal/mol more favorable than that in TS1b. TS1a is stabilized by a π–π stacking interaction between the furanyl group and the biaryl group of the phosphoramidite ligand (ΔEint-space(furan) = −3.9 kcal/mol) as well as a C–H/π interaction between the inductively polarized C8–H and the ligand (ΔEint-space(ether) = −3.7 kcal/mol). On the other hand, in TS1b, the furanyl group has a weaker noncovalent interaction with the ligand due to the longer distance (ΔEint-space(furan) = −2.2 kcal/mol). In addition, because the C8-OMe group is pointing toward the biaryl group on the ligand, a lone pair/π repulsion is observed, leading to overall weaker noncovalent interaction between the ligand and the ether fragment on the substrate (ΔEint-space(ether) = −3.1 kcal/mol in TS1b compared with −3.7 kcal/mol in TS1a). This lone pair/π repulsion with C8-OMe also leads to greater substrate distortion (ΔEdist(substrate)) in TS1b, which is evidenced by eclipsing repulsions of C8-OMe with both furanyl C–H (d(O···H) = 2.48 Å) and C9–H (d(H···H) = 2.19 Å). It should be noted that the relative energies between TS1a and TS1b are also affected, likely to a lesser degree, by several other factors, including a stronger stabilizing through-bond interaction between the Rh and the allene moiety in TS1b and pseudo-1,3-diaxial interactions between C8-OMe and C10-Me groups in the half-chair-like transition state TS1a. More detailed analyses of these interactions are provided in Supporting Information.

Figure 4.

Lowest energy oxidative cyclization transition-state isomers with (R)-13d (matched pairs). All energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 20. See Supporting Information for computational details, including distortion and through-space interaction energy calculations.

Next, we analyzed the lowest energy transition states in the mismatched reactions of (S)-13d with the (S)-4 ligand (Figure 5). In TS2a that leads to the slightly favored (2R) stereocenter, both the furanyl and the C8-OMe groups on (S)-13d point toward the biaryl group of the phosphoramidite ligand, whereas in TS2b, both furanyl and C8-OMe are further away from the ligand. Therefore, TS2a is stabilized by π–π stacking and C–H/π interaction of the furanyl group with the ligand (ΔEint-space(furan) = −4.7 kcal/mol), while also destabilized by the steric repulsion between the C8-OMe group and the ligand (d(O···H) = 2.79 Å), resulting in a weaker through-space interaction with the ether moiety (ΔEint-space(ether) = −2.9 kcal/mol). On the other hand, in TS2b, although the noncovalent interaction with the furanyl group is weaker (ΔEint-space(furan) = −3.1 kcal/mol), the interaction with the ether moiety is stronger (ΔEint-space(ether) = −4.4 kcal/mol) due to the favorable C–H/π interaction with C8–H. As a result, the overall through-space ligand–substrate interactions in TS2a and TS2b are comparable (ΔEint-space = −7.3 and −7.6 kcal/mol, respectively). The relatively small activation free energy difference in this mismatched case (ΔΔG‡ = 0.3 kcal/mol) can be mostly attributed to the pseudo-1,3-diaxial interaction between C8-OMe and C10-Me in the half-chair-like transition state TS2b. This is evidenced by a short O···H distance (2.34 Å) between the methoxy oxygen and C10-Me.

Figure 5.

Lowest energy oxidative cyclization transition-state isomers with (S)-13d (mismatched pairs). All energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 20. See Supporting Information for computational details, including distortion and through-space interaction energy calculations.

Taken together, the DFT calculations demonstrate that the orientations of the furanyl and C8-OMe groups in the oxidative cyclization transition states both affect the transition-state energies. While the former is affected by the π-facial selectivity of the allene when coordinating to the Rh catalyst, the latter is affected by the absolute configuration of the C8 stereogenic center. The calculations suggest that the dominant factor determining the stereoselectivity (ΔΔG‡) is the catalyst-controlled π-facial selectivity that always prefers to produce (2R)-PKR products with the (S)-4 ligand, regardless of the absolute configuration of C8 in the allene-yne substrate. On the other hand, the stereochemistry at C8 alters the magnitudes of the product diastereomeric ratio by affecting both noncovalent interactions between the C8-substituent and the chiral phosphoramidite ligand and intramolecular substrate distortions (Figures 4 and 5).

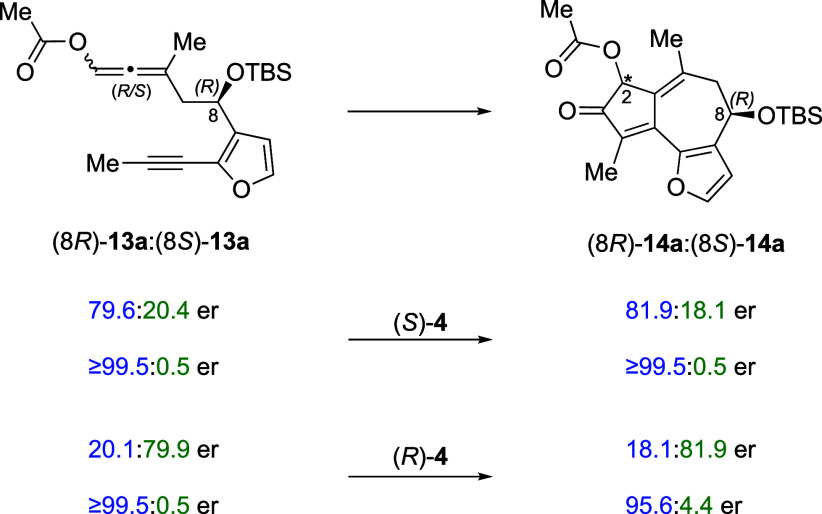

Absence of Kinetic Resolution

Monitoring the PKR reaction by chiral HPLC shows that there is no significant change in either de or er of the product throughout the reaction (5 h and 21 H). These data demonstrate that (8R)- and (8S)-13a react at the same rate (Table 2, entry 3). Moreover, comparison of the er of allene-yne 13a to that of 14a showed negligible or no change in the C8 er, providing further support that the observed asymmetric PKR is not a kinetic resolution process (Figure 6). For example, in the matched cases, enantioenriched 13a with C8 ers of 79.6:20.4 and ≥99.5:0.5 yielded 14a with C8 ers of 81.9:18.1 and ≥99.5:0.5. In the mismatched cases, enantioenriched 13a with C8 ers of 20.1:79.9 and ≥99.5:0.5 yielded 14a with C8 ers of 18.1:81.9 and 95.6:4.4.

Assignment of the Relative Configuration in Product 14a

To assign the relative stereochemistry of product 14a, the cis and trans diastereomers were analyzed together by 13C NMR, assigning the peaks via peak intensity differences. 13C NMR chemical shifts for each were computed using a protocol for calculating Boltzmann-weighted chemical shifts for conformationally flexible natural products with Spartan’24 (ωB97X-D/6-31G*).68 Comparison of calculated chemical shifts of the trans diastereomer to authentic spectral data for the major isomer showed a good match, with a Boltzmann average DP4 score of 100% and an RMS of 1.72. The minor cis diastereomer matched equally well, exhibiting a Boltzmann average DP4 score of 100% and an RMS of 1.35 (see SI for 13C NMR analysis).69

Assignment of the Absolute and Relative Configuration of 14g

To assign the absolute configuration of 14a, the silyl group was removed upon treatment with TBAF/AcOH at −10 °C (condition a).70 The cis and trans isomers of 14g were then separated by preparative TLC71 to afford (2S,8S)-14g (er = 94.7:5.3) and (2R,8S)-14g (er = 47.7:52.3) (Table 3, entry 1). TBS deprotection of (2R,8R)-14a gave the cis and trans isomers of 14g, which could be separated by preparative TLC ((2R,8R)-14g: er = 91.0:9.0; (2S,8R)-14g: er = 70.5:29.5) (entry 2). C2 epimerization was observed when deprotection was conducted with TBAF in the absence of AcOH (condition b),72 leading to an er switch for cis-14 (entry 3).

Table 3. Separation of Product 14a Diastereomersa.

| entry | SS:RRtrans-14a | SR:RScis-14a | condition,% yield | SS:RRtrans-14f | SR:RScis-14f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 96.8:3.2 | 65.9:34.1 | a, 44 | 94.7:5.3 | 47.7:52.3 |

| 2 | 3.7:96.3 | 30.1:69.9 | a, 56 | 9.0:91.0 | 70.5:29.5 |

| 3 | 96.7:3.3 | 63.4:36.6 | b, 29 | 83.2:16.8 | 16.4:83.6 |

Conditions a: TBAF/AcOH, THF, −10 °C; b: TBAF, THF, 0 °C to rt.

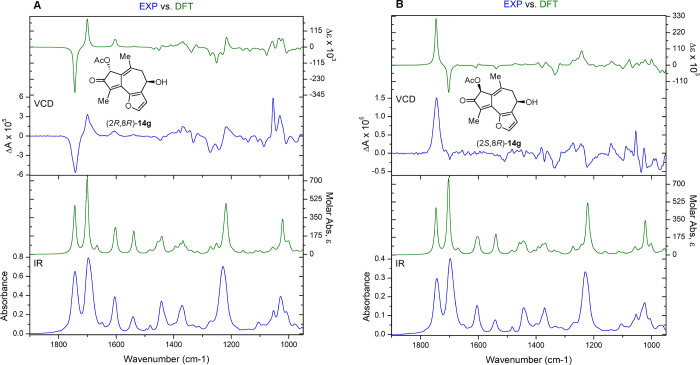

With three of the four stereoisomers in hand, we turned to VCD to assign the relative and absolute stereochemistry. The experimental IR and VCD data (blue) for (2S,8S)-14g and (2R,8R)-14g were independently measured, compared to DFT (B3LYP/cc-pVTZ)-calculated IR and VCD spectra (green), and quantified using CompareVOA software (BioTools, Jupiter FL). In all cases, high Sfg (overlap) values were observed, providing configuration assignments with a 100% confidence level (Figures 7A, S12–S15, S18, and S19). The VCD spectra for (2R,8S)-14g exhibit a low signal-to-noise ratio, due to a small amount of material (2 mg); however, computed VCD (B3LYP/cc-pVTZ) showed an excellent correlation to the experiment (Figures 7B, S16, S17, and S20). A Cai•factor of 68 was measured for (2R,8R)-14g showing a very confident assignment (Figure S21).60

Figure 7.

DFT-calculated (green) and experimental (blue) VCD and IR spectra of (A) (2R,8R)-14g; and (B) (2S,8R)-14g.

Conclusion

We report the first example of a catalyst-controlled dynamic kinetic asymmetric PKR, which yields the full stereochemical array of C2 and C8 thapsigargin analogues via a nonchiral pool starting material. This approach utilizes a preset stereocenter to influence catalyst binding in a way that can be predicted by a DFT transition-state analysis. The high stereoselectivity observed for both matched and mismatched cases was critical to our success. Further, VCD and 13C NMR strategies, supported by DFT calculations, allowed for the assignment of absolute configuration for all four stereoisomers. Our computational studies show that the catalyst-controlled stereoselectivity results from differences in substrate–ligand noncovalent interactions in the oxidative cyclization transition state, whereas the substrate C8 stereochemistry alters the magnitude of the diastereoselectivity by affecting substrate distortion as well as substrate–ligand noncovalent interactions. Together, these efforts have allowed us to expand the scope of dynamic kinetic asymmetric PKR to allene-ynes with a preset stereocenter. With this advance, we have solidified the robust nature of our catalyst-ligand system and placed the total synthesis of thapsigargin and its stereoisomeric analogs within reach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Damodaran Krishnan Achary for 2D-NMR collection and carbon assignments and Yifan Qi for the synthesis of the (S)-MonoPhos-alkene ligand. We thank the National Institute of Health (R35 GM128779) and the University of Pittsburgh for their financial support. DFT calculations were conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services and Support (ACCESS) program, supported by NSF award numbers OAC-2117681, OAC-1928147, and OAC-1928224.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c11661.

Detailed experimental protocols, characterization data, 1H/13C/2D NMR spectra, 1H NMR with chiral shift reagent spectra, 13C NMR data (experimental and computational), HPLC traces, VCD data (experimental and computational), supplementary figures (PDF)

Computational details and optimized geometries (PDF)

SI ZIP file (ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Heravi M. M.; Mohammadi L. Application of Pauson–Khand reaction in the total synthesis of terpenes. RSC Adv. 2021, 11 (61), 38325–38373. 10.1039/D1RA05673E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Navigating the Pauson–Khand reaction in total syntheses of complex natural products. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54 (3), 556–568. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Jiang C.; Zheng N.; Yang Z.; Shi L. Evolution of Pauson-Khand reaction: Strategic applications in total syntheses of architecturally complex natural products (2016–2020). Catalysts 2020, 10 (10), 1199. 10.3390/catal10101199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K.; Martin B. S.; Yin X.; Dai M. Natural product syntheses via carbonylative cyclizations. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36 (1), 174–219. 10.1039/C8NP00033F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum L. C.; Häfner M.; Gaich T. Total synthesis of the diterpene waihoensene. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133 (6), 2975–2978. 10.1002/ange.202011298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y.; Wang Z.; Zhang Z.; Zhang W.; Huang J.; Yang Z. Asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-waihoensene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (14), 6511–6515. 10.1021/jacs.0c02143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C.; Arya P.; Zhou Z.; Snyder S. A. A Concise total synthesis of (+)-waihoensene guided by quaternary center analysis. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132 (32), 13623–13627. 10.1002/ange.202004177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X.-T.; Chen J.-H.; Yang Z. Asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-spirochensilide A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (18), 8116–8121. 10.1021/jacs.0c02522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang K. V.; Xu C.; Reisman S. E. A 15-step synthesis of (+)-ryanodol. Science 2016, 353 (6302), 912–915. 10.1126/science.aag1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. S.; Xu C. Total synthesis of (−)-nakadomarin A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (13), 4332–4335. 10.1002/anie.201600990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows L. C.; Jesikiewicz L. T.; Lu G.; Geib S. J.; Liu P.; Brummond K. M. Computationally guided catalyst design in the type I dynamic kinetic asymmetric Pauson–Khand reaction of allenyl acetates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (42), 15022–15032. 10.1021/jacs.7b07121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deihl E. D.; Jesikiewicz L. T.; Newman L. J.; Liu P.; Brummond K. M. Rh(I)-catalyzed allenic Pauson–Khand reaction to access the thapsigargin core: Influence of furan and allenyl chloroacetate groups on enantioselectivity. Org. Lett. 2022, 24 (4), 995–999. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R.; Tamura T.; Watanabe Y.; Sakamoto A.; Yasuhara N.; Ito H.; Nakano M.; Fuse H.; Ohta A.; Noda T.; et al. Evaluation of broad anti-coronavirus activity of autophagy-related compounds using human airway organoids. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2023, 20 (4), 2276–2287. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.3c00114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban M. S.; Müller C.; Mayr-Buro C.; Weiser H.; Meier-Soelch J.; Albert B. V.; Weber A.; Linne U.; Hain T.; Babayev I.; et al. Multi-level inhibition of coronavirus replication by chemical ER stress. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 5536. 10.1038/s41467-021-25551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Beltagi S.; Preda C. A.; Goulding L. V.; James J.; Pu J.; Skinner P.; Jiang Z.; Wang B. L.; Yang J.; Banyard A. C.; et al. Thapsigargin is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of major human respiratory viruses: Coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A virus. Viruses 2021, 13 (2), 234. 10.3390/v13020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban M. S.; Müller C.; Mayr-Buro C.; Weiser H.; Albert B. V.; Weber A.; Linne U.; Hain T.; Babayev I.; Karl N.. Inhibiting coronavirus replication in cultured cells by chemical ER stress. bioRxiv, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam D.; Peguero J.; Cen P.; Arora S. P.; Sarantopoulos J.; Rowe J.; Allgood V.; Tubb B.; Campos L. A phase II, multicenter, single-arm study of mipsagargin (G-202) as a second-line therapy following sorafenib for adult patients with progressive advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11 (6), 833. 10.3390/cancers11060833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccioni D.; Juarez T.; Brown B.; Rose L.; Allgood V.; Kesari S. Atct-18 phase II study of mipsagargin (G-202), a psma-activated prodrug targeting the tumor endothelium, in adult patients with recurrent or progressive glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 17 (Suppl 5), v5. 10.1093/neuonc/nov206.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskulska A.; Janecka A. E.; Gach-Janczak K. Thapsigargin—from traditional medicine to anticancer drug. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (1), 4. 10.3390/ijms22010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thi Quynh Doan N.; Brogger Christensen S. Thapsigargin, origin, chemistry, structure-activity relationships and prodrug development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21 (38), 5501–5517. 10.2174/1381612821666151002112824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S. B.; Andersen A.; Poulsen J.-C. J.; Treiman M. Derivatives of thapsigargin as probes of its binding site on endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase: Stereoselectivity and important functional groups. FEBS Lett. 1993, 335 (3), 345–348. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80416-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Evans P. A. A concise, efficient and scalable total synthesis of thapsigargin and nortrilobolide from (R)-(−)-carvone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (17), 6046–6049. 10.1021/jacs.7b01734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H.; Smith J. M.; Felding J.; Baran P. S. Scalable synthesis of (−)-thapsigargin. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3 (1), 47–51. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M.; Andrews S. P.; Wierschem F.; Cleator E.; Smith M. D.; Ley S. V. Total synthesis of thapsigargin, a potent SERCA pump inhibitor. Org. Lett. 2007, 9 (4), 663–666. 10.1021/ol062947x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R. A.; Moharana S.; Khatun G. N. Recent advances in the syntheses of guaianolides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 6652–6670. 10.1039/D3OB01019H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana A.; Molinillo J. M.; Macías F. A. Trends in the synthesis and functionalization of guaianolides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015 (10), 2093–2110. 10.1002/ejoc.201403244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drew D. P.; Krichau N.; Reichwald K.; Simonsen H. T. Guaianolides in apiaceae: Perspectives on pharmacology and biosynthesis. Phytochem. Rev. 2009, 8, 581–599. 10.1007/s11101-009-9130-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schall A.; Reiser O. Synthesis of biologically active guaianolides with a trans-annulated lactone moiety. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008 (14), 2353–2364. 10.1002/ejoc.200700880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.-B.; Wang X.; Sun B.-F.; Zou J.-P.; Lin G.-Q. Catalytic asymmetric total synthesis of hedyosumins A, B, and C. Org. Lett. 2016, 18 (6), 1219–1221. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalidindi S.; Jeong W. B.; Schall A.; Bandichhor R.; Nosse B.; Reiser O. Enantioselective synthesis of arglabin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46 (33), 6361–6363. 10.1002/anie.200701584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tap A.; Jouanneau M.; Galvani G.; Sorin G.; Lannou M.-I.; Férézou J.-P.; Ardisson J. Asymmetric synthesis of a highly functionalized enantioenriched system close to thapsigargin framework. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10 (40), 8140–8146. 10.1039/c2ob26194d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straker R.; Peng Q.; Mekareeya A.; Paton R.; Anderson E. Computational ligand design in enantio-and diastereoselective ynamide [5 + 2] cycloisomerization. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7 (1), 10109. 10.1038/ncomms10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat V.; Welin E. R.; Guo X.; Stoltz B. M. Advances in stereoconvergent catalysis from 2005 to 2015: Transition-metal-mediated stereoablative reactions, dynamic kinetic resolutions, and dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117 (5), 4528–4561. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y.; Yasukawa T.; Yoo W.-J.; Kitanosono T.; Kobayashi S. Catalytic enantioselective aldol reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47 (12), 4388–4480. 10.1039/C7CS00824D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; Brindle C. S. The direct catalytic asymmetric aldol reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39 (5), 1600–1632. 10.1039/b923537j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc H. N.; Ozgun U.; Sirit A. Chiral tetraoxacalix[2]arene 2]triazine-based organocatalysts for enantioselective aldol reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60 (27), 1763–1768. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.05.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashokkumar V.; Chithiraikumar C.; Siva A. Binaphthyl-based chiral bifunctional organocatalysts for water mediated asymmetric List–Lerner–Barbas aldol reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14 (38), 9021–9032. 10.1039/C6OB01558A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N.; Han S.; Yu H. The 4, 5-methano-l-proline as a chiral organocatalysts in direct asymmetric aldol reactions. Tetrahedron 2015, 71 (28), 4665–4669. 10.1016/j.tet.2015.04.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paladhi S.; Das J.; Samanta M.; Dash J. Asymmetric aldol reaction of thiazole-carbaldehydes: Regio-and stereoselective synthesis of tubuvalin analogues. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014, 356 (16), 3370–3376. 10.1002/adsc.201400640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Secci F.; Cadoni E.; Fattuoni C.; Frongia A.; Bruno G.; Nicolo F. Enantioselective organocatalyzed functionalization of benzothiophene and thiophenecarbaldehyde derivatives. Tetrahedron 2012, 68 (24), 4773–4781. 10.1016/j.tet.2012.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.; Ge Z. M.; Cheng T. M.; Li R. T. L-Proline-based phosphamides as a new kind of organocatalyst for asymmetric direct aldol reactions. Chin. J. Chem. 2008, 26 (5), 911–915. 10.1002/cjoc.200890167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kucherenko A.; Syutkin D.; Zlotin S. Asymmetric aldol condensation in an ionic liquid-water system catalyzed by (S)-prolinamide derivatives. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2008, 57, 591–594. 10.1007/s11172-008-0092-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meciarova M.; Toma S.; Berkessel A.; Koch B. Enantioselective aldol reactions catalysed by N-toluenesulfonyl-L-proline amide in ionic liquids. Lett. Org. Chem. 2006, 3 (6), 437–441. 10.2174/157017806777828402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kano T.; Tokuda O.; Maruoka K. Synthesis of a biphenyl-based axially chiral amino acid as a highly efficient catalyst for the direct asymmetric aldol reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47 (42), 7423–7426. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.08.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi N.; Bisht S. S.; Tripathi R. P. Asymmetric organocatalysis with glycosyl-β-amino acids: Direct asymmetric aldol reaction of acetone with aldehydes. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341 (16), 2737–2743. 10.1016/j.carres.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano T.; Takai J.; Tokuda O.; Maruoka K. Design of an axially chiral amino acid with a binaphthyl backbone as an organocatalyst for a direct asymmetric aldol reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44 (20), 3055–3057. 10.1002/anie.200500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R.; Kofoed J.; Machuqueiro M.; Darbre T. A selective direct aldol reaction in aqueous media catalyzed by zinc–proline. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 5268–5276. 10.1002/ejoc.200500352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lingham A. R.; Hügel H. M.; Rook T. J. Studies towards the synthesis of salvinorin A. Aust. J. Chem. 2006, 59 (5), 340–348. 10.1071/CH05338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Shan Z. (R)-or (S)-Bi-2-naphthol assisted, l-proline catalyzed direct aldol reaction. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17 (11), 1671–1677. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodda R.; Samanta S.; Su M.; Zhao J. C. G. Synthesis of 1,2-diamine bifunctional catalysts for the direct aldol reaction through probing the remote amide hydrogen. Curr. Organocatal. 2019, 6 (2), 171–176. 10.2174/2213337206666190301155247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGown A.; Nafie J.; Otayfah M.; Hassell-Hart S.; Tizzard G. J.; Coles S. J.; Banks R.; Marsh G. P.; Maple H. J.; Kostakis G. E.; et al. Chirality: A key parameter in chemical probes. RSC Chem. Biol. 2023, 4 (10), 716–721. 10.1039/D3CB00082F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts J.; Aerts R.; Vermeyen T.; Johannessen C.; Herrebout W.; Batista Jr J. M. Tackling stereochemistry in drug molecules with vibrational optical activity. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14 (9), 877. 10.3390/ph14090877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten C.; Golub T. P.; Kreienborg N. M. Absolute configurations of synthetic molecular scaffolds from vibrational CD spectroscopy. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84 (14), 8797–8814. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Bo W.; Dukor R. K.; Nafie L. A. Determination of absolute configuration of chiral molecules using vibrational optical activity: A review. Appl. Spectrosc. 2011, 65 (7), 699–723. 10.1366/11-06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman T. B.; Cao X.; Dukor R. K.; Nafie L. A. Absolute configuration determination of chiral molecules in the solution state using vibrational circular dichroism. Chirality 2003, 15 (9), 743–758. 10.1002/chir.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J. M.; Griffiths P. R.. Handbook of vibrational spectroscopy; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Del Río R. E.; Joseph-Nathan P. Vibrational circular dichroism absolute configuration of natural products from 2015 to 2019. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16 (3), 1934578×21996166. 10.1177/1934578X21996166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polavarapu P. L.; Covington C. L. Comparison of experimental and calculated chiroptical spectra for chiral molecular structure determination. Chirality 2014, 26 (9), 539–552. 10.1002/chir.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debie E.; De Gussem E.; Dukor R. K.; Herrebout W.; Nafie L. A.; Bultinck P. A confidence level algorithm for the determination of absolute configuration using vibrational circular dichroism or Raman optical activity. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12 (8), 1542–1549. 10.1002/cphc.201100050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J.; Lewis R. J.; Goodman J. M. Interpreting vibrational circular dichroism spectra: The Cai•factor for absolute configuration with confidence. J. Cheminf. 2023, 15 (1), 36. 10.1186/s13321-023-00706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong A.; Boto R. A.; Dingwall P.; Contreras-Garcia J.; Harvey M. J.; Mason N. J.; Rzepa H. S. The Houk–List transition states for organocatalytic mechanisms revisited. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5 (5), 2057–2071. 10.1039/C3SC53416B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S.; Houk K. N.; Martin H. J.; List B. Quantum mechanical predictions of the stereoselectivities of proline-catalyzed asymmetric intermolecular aldol reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (9), 2475–2479. 10.1021/ja028812d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We used VCD to determine the absolute configuration of 17 because of our inability to convert oil 17 to a compound that may afford a crystalline solid (transformation of the hydroxyl group of 17 to the bromobenzoate S11 or S12 to the diol S13 was unsuccessful) (see SI page S128).

- Deihl E. D.Expanding the scope of the asymmetric allenic Pauson–Khand reaction towards the synthesis of thapsigargin and analogues. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eliel E. L.; Satici H. Conformational analysis of cyclohexyl silyl ethers. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59 (3), 688–689. 10.1021/jo00082a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows L. C.; Jesikiewicz L. T.; Liu P.; Brummond K. M. Mechanism and origins of enantioselectivity in the Rh(I)-catalyzed Pauson–Khand reaction: Comparison of bidentate and monodentate chiral ligands. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (1), 323–336. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Different concentrations of CO were tested, and the best result was obtained with CO (100%) (see SI page S66).

- Hehre W.; Klunzinger P.; Deppmeier B.; Driessen A.; Uchida N.; Hashimoto M.; Fukushi E.; Takata Y. Efficient protocol for accurately calculating 13C chemical shifts of conformationally flexible natural products: Scope, assessment, and limitations. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82 (8), 2299–2306. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. G.; Goodman J. M. Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: The DP4 probability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (37), 12946–12959. 10.1021/ja105035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit M. K.; Cao H. H.; Wu Y.-D.; Yip T. C.; Bendel L. E.; Zhang W.; Dai W.-M. Synthesis of the macrolactone cores of maltepolides via a diene–ene ring-closing metathesis strategy. Org. Lett. 2023, 25 (10), 1633–1637. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondack D. L. TLC separation and identification of diastereomers of D-ergonovine maleate. J. Pharm. Sci. 1974, 63 (7), 1141–1143. 10.1002/jps.2600630726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dachavaram S. S.; Kalyankar K. B.; Das S. First stereoselective total synthesis of neocosmosin A: A facile approach. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55 (41), 5629–5631. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.08.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.