Abstract

Objective

To analyze the various dental management strategies adopted to manage patients with hemophilia in a dental clinical setup.

Methods

An electronic database search was carried out using MEDLINE by PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases from January 2000 to August 2023 for case reports and case series published in English language. Case reports addressing the dental treatments for people with hemophilia A/hemophilia B were included. Cases of acquired hemophilia and cases of hemophilia who are inhibitor positive were excluded.

Results

There was a total of 286 articles that were identified of which 24 reports were included for the review. This included 20 case reports and four case series which addressed various dental treatment procedures performed on people with mild/moderate/severe hemophilia A or hemophilia B. A total of 28 patients were presented with a mean age of 20.4 years. The pre‐treatment factor ranged from 200 to 2500 IU and the post‐treatment factor range was 1000–3000 IU.

Conclusions

There was a wide range of variation in the utilization of prophylactic factors for dental treatment procedures among people with hemophilia. This variation highlights the need for larger prospective clinical studies that address the rationale for using clotting factor concentrate and its impact on dental treatment outcomes for individuals with mild, moderate, or severe hemophilia.

Keywords: comprehensive dental care, hemophilia A, hemophilia B, oral health

1. INTRODUCTION

Congenital hemophilia is the most common serious bleeding disorder that is inherited in an X‐linked recessive manner. It is caused by absence or reduced activity of factor VIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B). 1 Bleeding is the most common complication that could arise even after minor episodes of trauma. Bleeding from gums is a common sign of gingivitis even in healthy individuals but in these individuals even activities like toothbrushing can trigger prolonged bleeding. People with hemophilia (PwH) may experience major bleeding event following exfoliation of deciduous teeth or even minor trauma. Maintaining a good overall oral health for these individuals is imperative in order to minimize the risk of bleeding arising from the inflammation of the gingiva, compromised periodontal status and other dental causes. Moreover, poor oral hygiene practices and the fear of inducing bleeding on brushing, fear of dentists and dental procedures that may induce bleeding all lead to a compromise in the oral health of these individuals. It has been reported that patients with bleeding disorders often neglect dental care either due to fear of disease‐specific risks or patient‐related barriers, both potentially contributing to deteriorating oral health and consequently increasing the need for more invasive dental treatments. 2 , 3

Prophylactic factor therapy refers to the intravenous replacement of factor VIII or IX, with either purified plasma derived concentrates or recombinant factor concentrates to prevent bleeding. The dose, duration and frequency of this therapy depends on the severity of disease. The circulating levels of factor determine the extent of severity of the disorder which may be mild hemophilia: 5%–40% factor VIII/IX activity, moderate hemophilia:1%–5% and severe hemophilia where the circulating factor VIII/IX levels are <1%. 4 Bleeding from the oral tissues may be spontaneous or may be triggered due to oral or dental pathology or dental treatment procedures. Moreover, depending on the severity of hemophilia (mild, moderate or severe factor deficiency) control of the bleeding may even require hospitalization. Also, due to the limited guidelines available in literature regarding the protocols to be followed for these patients, dentists lack confidence while dealing with these special group of patients. 1 , 5

This systematic review was conducted to summarize the current evidence available on the various management strategies and dental treatment modifications adopted by dental specialists across the globe while treating people with hemophilia. The objective was to analyze the various dental treatment procedures, and the prophylactic clotting factor concentrate used for PwH from clinical case reports. Various clinical parameters namely the severity of hemophilia, dosage of clotting factor concentrates used, post‐procedural complications, and outcomes along with special dental treatment considerations adopted were analyzed from various case reports and case series across the globe. The review serves a dual purpose: it offers insights into current practices while also serving as a guide for evidence‐based practices for clinicians. This suggests that the review not only analyses and summarizes existing practices but also aims to provide practical guidance for healthcare professionals, emphasizing the importance of evidence‐based decision‐making in their clinical work.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study selection

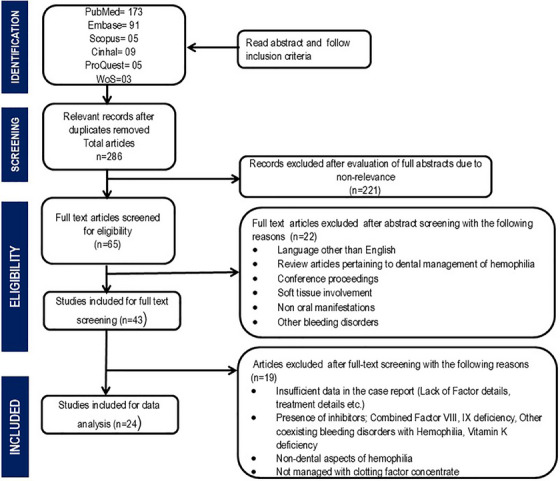

This systematic review of case reports and case series was conducted as per the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1). The research question was “what are the various dental treatment strategies adopted for dental procedures in people with mild/moderate and severe hemophilia?” (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart depicting the selection of published articles.

FIGURE 2.

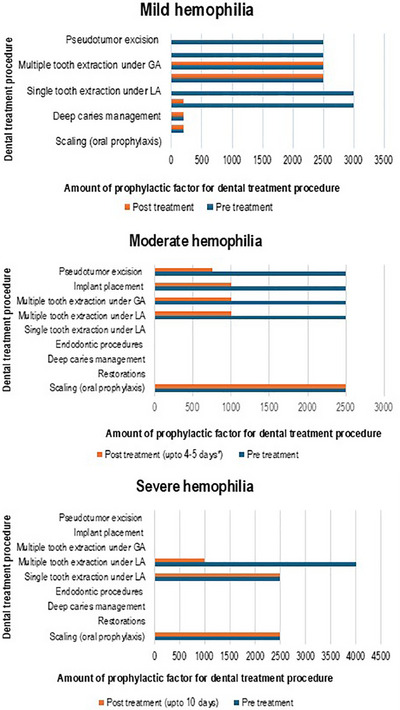

Graphs showing the amount of factor utilized for various dental treatment procedures for people with mild, moderate and severe hemophilia.

The search strategy was discussed among the authors and consensus was arrived. Following this, one reviewer (author MK) evaluated the included reports and excluded the unrelated reports and duplicate articles. Of the 286 case reports/series that were identified, 43 articles were screened for the title, abstract as well as the full text by two reviewers (MK, SB) systematically. For final data analysis, 24 articles were included. The details were entered in the Microsoft Excel data sheet. The included articles were then screened for the full text and the data were summarized into tabular format. The PICO (population, intervention, context, and outcome) employed for this review is as follows:

2.1.1. Population

The inclusion criteria comprised all case reports and case series with reported cases of dental treatment management in people with hemophilia. Reports on other inherited bleeding disorders (von Willebrand disease, Factor XIII deficiency, thrombocytopenia), inhibitor positive cases of hemophilia, acquired hemophilia and reports in language other than English, conference abstracts, and posters were excluded. Review articles pertaining to dental management of hemophilia, conference proceedings, case reports addressing the non‐oral manifestations were also excluded.

2.1.2. Intervention

Reports addressing the dental procedures that were performed in people with hemophilia A/hemophilia B were included. Reports documenting patient demographic details, severity of the disease (mild/moderate/severe hemophilia A/B), dental treatment procedure performed (restorations, root canal treatment, surgical extractions, dental implant procedures, removal of the pseudotumor of the jaws), management strategies to control oral bleed were included.

2.1.3. Context

Reports addressing dental treatment modifications used during dental treatment for people with mild/moderate/severe hemophilia A/hemophilia B were included.

2.1.4. Outcome

The reported prophylactic clotting factor concentrates used for dental treatment procedures, the use of anti‐fibrinolytic drugs employed with the dosages utilized for dental procedures, post‐procedural measures to control bleeding, use of local hemostatic agents, special dental treatment procedural modifications adopted, outcomes and complications of the dental treatment procedures were reviewed.

2.2. Search strategy and data extraction

An electronic search was performed using MEDLINE by PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases from January 2000 to August 2023 in English language. The keywords were selected from the National Library of Medicine's Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term. Title and abstract screening were performed with Boolean operators (AND, OR). The search strategy terms included were “hemophilia A”, “hemophilia A”, “hemophilia B”, “hemophilia B”, “dental care”, “case reports”, “case series”.

2.3. Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for case reports and case series was used for quality assessment of the included literature. 6 Two reviewers (MK, SB) performed this task. Case series were restricted to the dental management of hemophilia. Quality assessment was performed to note the details regarding the pre‐dental treatment factor coverage and relevant systemic anti‐fibrinolytic regimen that was employed along with the takeaway lessons from the included reports.

3. RESULTS

With the search strategy and criteria, a total of 24 reports were included for the review of which 20 were case reports 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 and four were case series. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 A case series that described two cases of mild hemophilia A and B who underwent extraction of third molar tooth was considered as two separate entities since one case was of an adult and other was a pediatric case. 27 A total of 28 patients were presented in the included reports. The mean age of people with hemophilia in these reports was 20.4 years. There were 14 pediatric (<14 years of age) and 13 adults with hemophilia, one in report age not mentioned. The results cannot be combined and hence described as separate reports. The list of included case reports and case series along with the various clinical parameters and dental treatment outcomes are depicted in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Table depicting the list of included case reports and case series along with the various clinical parameters and dental treatment outcomes.

| S. No | Author | Year | Country | Type of report | Population (adult/pediatric) | Type of hemophilia (hemophilia A/B) | Severity of hemophilia | Invasiveness of dental procedure (mild/moderate/highly invasive) | Complications | Use of oral anti‐fibrinolytic therapy | Use of prophylactic factor concentrate therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Shreya Desai et al. 7 | 2023 | USA | Case report | Pediatric | Hem B | Mild | Highly | None | Yes | None |

| 2. | Omolehinwa et al. 8 | 2023 | USA | Case report | Adult | Hem A | Moderate | Moderately | None | Yes | Yes |

| 3. | Rayen et al. 9 | 2011 | India | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | Slim bleeding | None | Yes |

| 4. | Peisker et al. 30 | 2014 | Europe | Case report | Adult a | Hem B | Severe | Highly | None | Yes | Yes |

| 5. | Liras et al. 11 | 2019 | Europe | Case report | Adult | Hem A | Severe | Highly | None | None | Yes |

| 6. | Abramowicz et al. 12 | 2008 | USA | Case report | Adult a | Hem A | Mild | Highly | Post‐op bleeding | None | Yes |

| 7. | Chattopadhyay et al. 13 | 2017 | India | Case report | Pediatric | Hem B | Moderate | Highly | None | None | Yes |

| 8. | Gornitsky et al. 14 | 2005 | Canada | Case report | Adult | Hem A | Moderate | Highly | None | None | Yes |

| 9. | Fan et al. 26 | 2022 | China | Case series: 2 patients | Adult | Hem A | Mild | Highly | Persistent post op bleeding | None | Yes |

| 10. | Ngoc et al. 15 | 2018 | Vietnam | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Severe | Moderately | None | None | Yes |

| 11. | Throndson et al. 16 | 2012 | USA | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | None | Yes | Yes |

| 12. | Jayaraman 17 | 2023 | USA | Case report | Pediatric a | Hem A | Mild | Moderately | None | None | Yes |

| 13. | Kinalski et al. 31 | 2021 | Brazil | Case report | Adult | Hem B | Not mentioned | Highly | Delayed bleeding | None | Yes |

| 14. | Guirado et al. 19 | 2019 | USA | Case report | Adult | Hem B | Severe | Highly | Delayed bleeding | Yes | Yes |

| 15. | Bacci et al. 20 | 2021 | Europe | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | None | None | Yes |

| 16a. | Farrkh et al. 27 | 2016 | USA | Case series: 1 case | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | Delayed bleeding | None | Yes |

| 16b. | Farrkh et al. 27 | 2016 | USA | Case series: 1 case | Adult | Hem B | Mild | Highly | Buccal space infection | Yes | Yes |

| 17. | Lima et al. 25 | 2008 | South America | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | None | Yes | Yes |

| 18. | Bajkin et al. 32 | 2012 | Europe | Case Report | Adult | Hem A | Mild | Highly | None | Yes | No |

| 19. | Otsuka et al. 21 | 2015 | Japan | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Moderate | Highly | Delayed bleeding | No | Yes |

| 20. | Madan et al. 22 | 2011 | India | Case report | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Moderately | None | Yes | Yes |

| 21. | Srinivasan et al. 23 | 2011 | India | Case report | Pediatric | Hem B | Mild | Highly | None | No | Yes |

| 22. | Lee et al. 24 | 2009 | Korea | Case report | Adult | Hem B | Severe | Highly | None | No | Yes |

| 23. | Rey et al. 28 | 2007 | South America | Case series: 3 cases | Pediatric | Hem A | Mild | Highly | None | No | Yes |

| 24. | Haghpanah et al. 29 | 2011 | Iran | Case series: only 1 case with hemophilia A is included | Adult | Hem A | Severe | Highly | None | No | Yes |

Female.

The reported severity of hemophilia in these reports were 16 mild hemophilia, four with moderate hemophilia and seven with severe hemophilia and the severity was not mentioned in one report. 33 Six patients had a positive family history of hemophilia and five patients did not have a positive family history. 17 reports did not mention any details about the bleeding disorder in the family.

Twenty‐two patients had a previous history of hemophilia of which four patients were diagnosed with hemophilia due to oro‐dental cause and the incident that led to the diagnosis of hemophilia were not mentioned in one report. 32 The various presenting symptoms to the dental clinic are summarized in Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

Table depicting the various presenting symptoms to the dental clinic by people with mild/moderate and severe hemophilia.

| Presenting complaint | No of patients |

|---|---|

| Routine oral checkup | 1 |

| Dental (tooth‐related) complaints | 9 |

| Oral bleeding | 4 |

| Oral soft tissue swelling | 5 |

| Uncontrolled oral bleed post extraction | 3 |

| Jaw‐size discrepancy | 4 |

| Avulsion | 1 |

The reported special treatment modifications adopted by various authors for invasive dental procedures are as follows:

3.1. Dental extractions

Use of nontraumatic needles for administering local anesthesia. 9

Preferring infiltration technique for anesthesia (articaine) and lidocaine block (inferior alveolar nerve) 26 , 32 for mild cases.

Sockets were packed with local hemostatic agents (surgical), resorbable 4‐0 vicryl sutures. 9

Use of fibrin glue; resorbable figure‐of‐eight sutures (4‐0) of the extraction site. 32

Sockets were packed with gelatin foam sponges covered with topical thrombin and sutured with slowly resorbing sutures. 27

3.2. Implant procedures 19

Use of tranexamic acid oral tablets (1000 mg) and a local para‐periostal anesthesia for implant placement

Endosteal implant with flapless technique was placed after a single infusion of recombinant factor VIII (2000 IU)

The local hemostatic agents used for the management of bleeding from the dental extraction site in a pediatric patient with mild hemophilia B were topical thrombin on gauze for an hour, use of Gelfoam (gelatine sponge) and Avitene (micro filler collagen) or the extraction site was sutured with 4‐0 chromic gut suture, with continued gauze compression following the procedure. 7 Also, 1 mL glubran fibrin glue 29 and no factor was used in one case with mild hemophilia 32 .

The dose of factor that is to be given for each case is calculated using the following standardized formula as follows 34 :

Dose (IU) of Factor VIII = body surface (kg) x level of desired factor VIII increase (IU/dL) x 0.5

Dose (IU) of Factor IX = body surface (kg) x level of desired factor IX increase (IU/dL)

3.3. The amount of factor administered prior to and following various dental treatment procedures

Pseudotumor was observed in three patients with Hem B and one patient with Hem A (two mild, one moderate, and one severe). 13 , 23 , 24 , 28

The reported complications following the dental extraction procedures were slim bleeding from surgical site, 9 significant post‐op bleeding (200–400 mL), 12 , 13 constant post op bleeding at day 9, 27 buccal space infection at day 4 27 and residual bleeding following excision of pseudotumor of the mandible. 21

The amount of factor administered prior to and following various dental treatment procedures gathered from the included reports are summarised in Table 3 and depicted in Figure 2.

TABLE 3.

Table depicting the amount of factor administered prior to and following various dental treatment procedures from the included reports.

| Invasiveness of dental procedure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild hemophilia | Moderate hemophilia | Severe hemophilia | |||||

| Procedure | Number of patients with severity of hemophilia | Pre‐dental treatment Factor dose | Post dental treatment Factor dose | Pre‐dental treatment Factor dose | Post dental treatment Factor dose | Pre‐dental treatment Factor dose | Post dental treatment Factor dose |

| Mildly invasive | |||||||

| Scaling 8 , 11 , 15 | 3 cases: 1 moderate; 2 severe | Not performed | Not performed | 2500 IU | 2500 IU | 2500 IU | 2500 IU for 2 days |

| Restoration 9 , 15 | 2 cases: 1 mild; 1 severe | 200 IU | 200 IU 12th hourly | Not performed | Not performed | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Moderately invasive | |||||||

| Deep caries management 9 , 15 , 32 | 3 cases: 2 mild; 1 severe | 200 IU | 200 IU 12th hourly | Not performed | Not performed | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Endodontics 9 , 15 , 20 | 3 cases: 2 mild; 1 severe | 200 IU 3000 IU | 200 IU | Not performed | Not performed | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Highly invasive | |||||||

| Single tooth extraction under local anaesthesia 11 , 18 , 20 | 3 cases: 1 mild; 1 severe and 1 not mentioned | 3000 IU | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | 2500 IU | 2500 IU twice a day for two days |

| Multiple tooth extraction under local anaesthesia 14 , 26 , 30 , 35 | 4 cases: 3 mild; 1 moderate | 2500 IU | 2500 for 4–5 days | 2500 IU | 1000 IU for one day | Not performed | Not performed |

| Multiple tooth extraction under general anaesthesia 9 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 27 | 5 cases: 4 mild; 1 moderate | 2500 IU | 2500 for 4–5 days | 2500 IU | 1000 IU for 4 to 5 days | Not performed | Not performed |

| Implant placement 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 | 4 cases: 1 mild; 1 moderate; 1 severe, 1 not mentioned | 2500 IU | Not performed | 2500 IU | 1000 IU for one day | 3000 IU | 3000 IU for two days |

| Pseudotumor excision 13 , 23 , 24 , 28 | 4 cases: 2 mild; 1 moderate, 1 severe | 2500 IU | Not performed | 2500 IU | 750 IU for 4 to 5 days | 8060 IU for every 12 hours | 3710‐3310 IU tapering dose over 2 weeks |

4. DISCUSSION

Congenital hemophilia is the most common bleeding disorder with hemophilia A (reduced circulating factor VIII) being more common than hemophilia B (reduced circulating factor IX). The extent of bleeding and complications that occur in PwH depends on the severity of hemophilia. 34 Various countries across the globe follow treatment protocols for PwH as per their respective clinical setting. 34 , 36 , 37 The concept of “on‐demand factor therapy” versus “prophylactic” factor replacement therapy determines the amount of factor required for dental treatment procedures. In the present work, majority of the reports were from Asian countries and USA. The concept of “prophylactic” factor replacement therapy in the western world differs from the “on‐demand factor therapy” mostly adopted by the Asian countries. 38 It was noted that people with mild hemophilia more frequently underwent dental treatment procedures compared to the moderate and severe hemophilia.

Bleeding from the oral cavity can lead to even life‐threatening hemorrhage in these individuals. People with hemophilia often tend to ignore oral health due to the fear of inducing oral bleeding and fear of dentists and dental treatment procedures among PwH. 2 Uncontrolled bleeding arising from the oral cavity was the primary presenting symptom of hemophilia. 7 , 23 , 26 A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis by Silva et al. and Kinalski et al. showed there was no significant differences in the oral health status of children and adolescents with hemophilia compared to their healthy counterparts. 39 , 40

Dental treatment procedures may be noninvasive, mildly invasive, slightly invasive or highly invasive based on which the risk of bleeding may vary. Consequently, there will be a variation in the amount of factor concentrate required for the control of bleeding arising due to the procedures performed in the oral cavity. 4 Patients on prophylactic factor therapy usually experience uneventful dental treatment procedures due to the factor cover that render them “risk‐free” from prolonged posttreatment bleeding. There were two cases in this report in which the patient was on prophylactic factor replacement therapy. 17 , 27 Jayaram J reported a case of successful reimplantation of avulsed maxillary incisor teeth where the patient was on prophylactic factor replacement therapy. 17

It was observed from the analysis of the included reports that irrespective of the severity of hemophilia and invasiveness of dental procedures, even mild cases planned for multiple dental treatments (restoration, extractions etc.) were administered factor replacement prior to procedure. 9 For oral prophylaxis (2 cases) performed in moderate and severe cases; tranexamic acid 1300 mg orally thrice a day before procedure, Recombinant factor VIII 50 units/kg prior to treatment and oral tranexamic acid 1300 mg three times a day for 7 days, factor VIII was given for 5 days after the scaling procedure at the dosage of 50 units/kg (IV) every 24 h. 8 , 11 Also, irrespective of the severity of hemophilia, highly invasive procedures like endosteal implant placement warranted the need for pre and post implant procedural factor replacement therapy (Dose range from 2500 to 3000 IU as long as ten days). 18 , 19 , 41

Atraumatic technique while performing dental treatment procedures and special considerations may be warranted for people with hemophilia. During scaling procedure, minimum power ultrasonic scaler (No 1 Satelac tip) may be preferred for these patients. Similarly, atraumatic technique with careful forceps‐handling with adequate clearance from the gingival soft tissue while performing dental extraction procedure with palatal–buccal and circular movements can be adopted. 11 In a case of mild Factor IX deficiency, invasive procedure like mandibular third molar impaction surgery was managed with factor replacement as high as 10000 IU prior to the procedure under general anesthesia and 5000 IU up to three days post‐operatively. 27

Bajkin et al. reported a case of a 34‐year old male with mild hemophilia who underwent extraction of maxillary premolar tooth without factor replacement therapy and adequate hemostasis was achieved with the fibrin sealant and suturing. 32 Shreya Desai et reported a case of a seven year old child who was diagnosed with mild hemophilia B due to excessive bleeding from dental extraction site after four days and the patient and was managed with local measures and oral antifibrinolytic therapy without the need for factor replacement. 7

The results of the JBI critical appraisal checklist for case reports and case series showed that the quality of reports included for this review were moderate to good. Most of the case reports scored six or above out of eight quality criteria. All the five included case series scored 8 or higher out of the ten criteria.

The limitations highlighted in this review are crucial for understanding the context and potential implications of the findings. A breakdown of the identified limitations are as follows:

Incomplete Details on Pre‐procedural Factor Infusion: Lack of comprehensive information about pre‐procedural factor infusion could impact the thoroughness of the review. This missing data may hinder the ability to assess the effectiveness of factor infusion in different cases.

Limited Information on Factor Duration: The absence of details regarding the duration of factor infusion is a notable limitation. Knowing the duration is crucial for understanding the sustainability and effectiveness of the treatment.

Incomplete or Missing Data on Patient Weight: The absence of information regarding patient weight, essential for calculating factor doses, is a significant gap. This limitation could affect the accuracy of dosing, potentially impacting the outcomes of the treatment.

Von Willebrand Factor Assay Details for Mild Cases: Incomplete details on the von Willebrand Factor assay for mild cases raise concerns about potential overlaps between von Willebrand disease and hemophilia. This lack of clarity could impact the precision of the review's conclusions.

Lack of Details on Referral Protocols: The absence of information on referral protocols for treating patients with different severity levels of hemophilia is a substantial limitation. This could affect the generalizability and applicability of the findings to different patient populations.

4.1. Recommendations for patient‐centered care

The conclusion emphasizes the need for a patient‐centered care approach with a multidisciplinary team. This implies that the identified limitations should prompt healthcare providers to adopt a holistic and collaborative approach when offering dental treatment services for patients with hemophilia. The treatment strategies are custom made for each patient and consultation needs to be sought with the patient's hematologist for patient specific protocols whenever dental treatment procedures are planned. It is to be noted that the circulating factor levels vary in mild, moderate and severe hemophilia and the replacement therapy depends on the severity of hemophilia and the type of dental procedure that is scheduled for the patient.

Addressing these limitations in future research can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing dental treatment outcomes for patients with hemophilia.

5. CONCLUSION

There was wide range of variation in the utilization of clotting factor concentrate employed for patients with hemophilia who underwent dental treatment procedures. This global variation can be attributed to the nature of health care models offered to these patients. A comprehensive care model with dental care as an integral part needs to be advocated in order to avoid advanced dental disease and invasive dental treatment procedures. Prompt dental treatment minimizes the amount of quantity of clotting factor replacement therapy necessary for dental treatment procedures. Preventive oral health care measures eliminate the need for invasive and expensive treatment procedures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors hereby declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There were no grants, patent licensing arrangements, consultancies, stock or other equity ownership, advisory board memberships, or payments for conducting or publicizing this work. This project did not receive any financial aid.

Kumar M, Badagabettu S, Pai KM, Nayak BS. Dental management of people with congenital hemophilia: An integrative review of case reports and case series from a global scenario. Spec Care Dentist. 2025;45:1–10. 10.1111/scd.13099

REFERENCES

- 1. Srivastava A, Santagostino E, Dougall A, et al. WFH guidelines for the management of hemophilia, 3rd edition. Haemophilia. 2020;26:1‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar M, Pai KM, Kurien A, Vineetha R. Oral hygiene and dentition status in children and adults with hemophilia: a case–control study. Spec Care Dent. 2018;38:391‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zaliuniene R, Aleksejuniene J, Peciuliene V, Brukiene V. Dental health and disease in patients with haemophilia—a case‐control study. Haemophilia. 2014;20:194‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Römer P, Heimes D, Pabst A, Becker P, Thiem DGE. Bleeding disorders in implant dentistry : a narrative review and a treatment guide. Int J Implant Dent. 2022. doi: 10.1186/s40729-022-00418-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freedman M, Dougall A, White B. An audit of a protocol for the management of patients with hereditary bleeding disorders undergoing dental treatment. J Disabil Oral Heal. 2009;10:151‐155. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munn Z, Barker TH, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2127‐2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desai S, Berry EJ, Unkel JH, Reinhartz J, Reinhartz D. A case report of haemophilia: a review of haemophilia and oral health implications. Br Dent J. 2023;234:92‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Omolehinwa TT, Dayo A. Patient with hemophilia a presenting for extractions and implants. Dent Clin NA. 2023;67:465‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rayen R, Hariharan VS, Elavazhagan N, Kamalendran N, Varadarajan R. Dental management of hemophiliac child under general anesthesia. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2011;29:74‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peisker A, Kentouche K, Raschke GF, Schultze‐Mosgau S. Management of third molar removal with doses of native plasma‐derived factor IX (Octanine) and local measures in a female patient with severe hemophilia B: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2014;45:239‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liras A, Romeu L. Dental management of patients with haemophilia in the era of recombinant treatments: increased efficacy and decreased clinical risk. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abramowicz S, Staba SL, Dolwick MF, Chen DR. Orthognathic surgery in a patient with hemophilia A: report of a case. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontology. 2008;105:437‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chattopadhyay PK, Nagori SA, Menon RP, Balasundaram T. Hemophilic pseudotumor of the mandible in a patient with hemophilia B. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;21:467‐469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gornitsky M, Hammouda W, Rosen H. Rehabilitation of a hemophiliac with implants: a medical perspective and case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:592‐597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ngoc VTN, Van Nga TDo, Chu DT, Anh LQ. Pulpotomy management using laser diode in pediatric patient with severe hemophilia A under general anesthesia—A case report. Spec Care Dent. 2018;38:155‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Throndson RR, Baker D, Kennedy P, McDaniel K. Pseudotumor of hemophilia in the mandible of a patient with hemophilia A. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:229‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jayaraman J. Young hemophilia patient presenting with avulsed maxillary permanent incisor. Dent Clin NA. 2023;67:473‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Azevedo M, Brondani LP, de Mattos ALM, Santos MBF. Delayed bleeding in a hemophilic patient after sinus floor elevation and multiple implant placements. J Oral Implantol. 2022(2):133‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calvo‐guirado JL, Romanos GE, Delgado‐ruiz RA. Infected tooth extraction, bone grafting, immediate implant placement and immediate temporary crown insertion in a patient with severe type‐B hemophilia. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(3):e229204. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bacci C, Cerrato A, Zanette G, Pasca S, Zanon E. Regenerative surgery with dental implant rehabilitation in a haemophiliac patient. TH Open. 2021;5(1):e104‐e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Otsuka H, Ozeki M, Kanda K, et al. Complete bone regeneration in hemophilic pseudotumor of the mandible. Pediatr Int. 2016;58(5). doi: 10.1111/ped.12820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Madan N, Rathnam A, Bajaj N. Treatment of an intraoral bleeding in hemophilic patient with a thermoplastic palatal stent—a novel approach. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1(1):79‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Srinivasan K, Gadodia A, Bhalla AS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of mandibular hemophilic pseudotumor associated with factor IX deficiency: report of case with review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(6):1683‐1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee DW, Jee YJ, Ryu DM, Kwon YD. Changes in a hemophilic pseudotumor of the mandible that developed over a 20‐year period. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(7):1516‐1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lima GS, Robaina TF, Lourenço SDeQC, Dias EP. Maxillary hemophilic pseudotumor in a patient. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30(8):605‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fan G, Shen Y, Cai Y, Zhao JH, Wu Y. Uncontrollable bleeding after tooth extraction from asymptomatic mild hemophilia patients: two case reports. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farrkh A, Garrison E, Closmann, JJ. the patient with hemophilia. Gen Dent. 2016;64(4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rey EA, Puia S, Bianco RP, Pinto MT. Haemophilic pseudotumour of the mandible: report of three cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:552‐555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haghpanah S, Vafafar A, Golzadeh MH, Ardeshiri R, Karimi M. Use of Glubran 2 and Glubran tissue skin adhesive in patients with hereditary bleeding disorders undergoing circumcision and dental extraction. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:463‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peisker A, Raschke GF, Schultze‐Mosgau S. Management of dental extraction in patients with haemophilia A and B: a report of 58 extractions. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19:55‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Azevedo Kinalski M, Brondani LP, De Mattos Carpena ALM, Dos Santos MBF. Delayed bleeding in a hemophilic patient after sinus floor elevation and multiple implant placements: a case report. J Oral Implantol. 2022;48:133‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bajkin BV, Rajic NV, Vujkov SB. Dental extraction in a hemophilia patient without factor replacement therapy : a case report. YJOMS. 2012;70:2276‐2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kinalski MDA, Sarkis‐onofre R, Inherited bleeding disorders in oral procedures. Assessment of prophylactic and therapeutic protocols: a scoping review. 150‐158 (2021) doi: 10.1111/adj.12813 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser‐Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19:1‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bajkin B, Dougall A. Current state of play regarding dental extractions in patients with haemophilia: consensus or evidence‐based practice? A review of the literature. Haemophilia. 2020;26:183‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hewson Id, Daly J, Hallett Kb, et al. Consensus statement by hospital based dentists providing dental treatment for patients with inherited bleeding disorders. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:221‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brewer A, Correa ME, Guidelines for dental treatment of patients with inherited bleeding disorders. 2006.

- 38. Fischer K, Van Der Bom JG, Molho P, et al. Prophylactic versus on‐demand treatment strategies for severe haemophilia: a comparison of costs and long‐term outcome. Haemophilia. 2002;8:745‐752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kinalski MDeA, De Araujo LP, Dos Santos MBF. Is there a difference in the oral health status of healthy patients and those with inherited bleeding disorders? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of case‐control studies. Dent Rev. 2022;2:100046. [Google Scholar]

- 40. da Silva LT. Can hemophilia impact on the oral health conditions of children and adolescents? A systematic review and metanalysis. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2022;22:1‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bacci C, Schiazzano C, Zanon E, Stellini E, Sbricoli L, Bleeding disorders and dental implants: review and clinical indications. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]