Abstract

Background

This study investigated socio-demographic, psychiatric, and psychological characteristics of patients with high versus low utilization of psychiatric inpatient services. Our objective was to better understand the utilization pattern and to contribute to improving psychiatric care.

Methods

One-hundred and twenty inpatients of the University Psychiatric Clinics (UPK) Basel, Switzerland, participated in this cross-sectional study. All patients were interviewed using different clinical scales. As target variables we investigated the number of days of psychiatric inpatient treatment within a 30-month period.

Results

Despite including multiple relevant patient variables and using elaborate statistical models (classic univariate und multiple regression, LASSO regression, and non-linear random forest models), the selected variables explained only a small percentage of variance in the number of days of psychiatric inpatient treatment with cross-validated R 2 values ranging from 0.16 to 0.22. The number of unmet needs of patients turned out to be a meaningful and hence potentially clinically relevant correlate of the number of days of psychiatric inpatient treatment in each of the applied statistical models.

Conclusions

High utilization behavior remains a complex phenomenon, which can only partly be explained by psychiatric, psychological, or social/demographic characteristics. Self-reported unmet patient needs seems to be a promising variable which may be targeted by further research in order to potentially reduce unnecessary hospitalizations or develop better tailored psychiatric treatments.

Keywords: High utilization, Psychiatric inpatient services, Re-hospitalisation, Revolving door, Severe mental illness

Background

In a perfect world, people with mental health problems can turn to health professionals in their local communities to receive help and support whenever indicated. If the situation is more severe, outpatient support may not suffice and inpatient psychiatric treatment could be required (cf., stepped care and collaborative care models; e.g., [1–3]). The simplified objective of a stay in a psychiatric hospital is the provision of effective multidisciplinary treatment that supports patients in their recovery and allows reaching the highest quality of life. Depending on the respective guidelines, such a treatment may entail psychotherapy, medication, psychiatric nursing care, and many other options that the respective hospital has to offer and the patients like and need. Once the individual objective is reached, the patients leave the inpatient setting and may receive further support within their local communities. Ideally, the main part of mental health care takes place in the outpatient setting (cf., the outpatient before inpatient policy in Switzerland, [4], see also [5], and a perspective on associated stigma by [6]). Inpatient stays would tend to be short and a more exceptional case (e.g., starting with least restrictive and intensive care and reserve more intensive treatment for “people who do not benefit from first-line treatments”, as described in the stepped care approach by [1, 7], see also “balanced care” as described in [8]). This, however, is not always the case. Many patients need to be readmitted to psychiatric hospitals and experience multiple stays throughout a certain period or their lifetime [9]. On the one hand, this may indicate that a specific group of patients rely on comparatively frequent inpatient treatment to obtain a sufficient treatment outcome in certain life periods. On the other hand, this may also point to the possibility that adequate treatment and care by multidisciplinary teams outside of the hospital are not accessible in mental health crises or are not sufficiently tailored to this patient group’s specific characteristics and needs.

(High) utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment

To better understand the utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment, previous research systematically focused on the number of days specific patients spent in the hospital and relevant correlates which might be associated with the amount of time spent there. Researchers identified that a small percentage of patients utilize a large number of inpatient treatment days provided by hospitals. This pattern has been described as high utilization (HU) of psychiatric care and the group of patients that require proportionally larger numbers inpatient treatment days as high utilizers [9–11]. Other terms used in the literature are heavy or frequent user (see, e.g., [12]) or revolving door patients [13].

Previous research investigated the high utilization phenomenon and highlighted differences between patients with a high versus low utilization profile (see, e.g., [14]). Regarding gender, previous studies reported inconclusive results, as some studies indicate a higher proportion of male patients (e.g., [15]), whereas others point to a higher proportion of female patients with a high utilization profile (e.g., [16]). Patients with high utilization tend to be younger [17, 18]. Other work indicated that high versus low utilization was more likely associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder [9, 16, 19–21] as well as comorbid substance use/abuse or personality disorder [14, 16, 20–22]. Symptomatic burden as well as lower integration into the local social and health services network were associated with a higher utilization pattern [11].

The use of varying definitions of high-utilization, however, – which could result in the same behavior only sometimes being classified as high utilization – limits the current knowledge in this research field and consequently the development of standardized targeted interventions for patients with a high utilization profile of psychiatric inpatient treatment (e.g., [14]).

While the number of studies examining the high utilizer phenomenon in psychiatry has increased in recent decades [23], there are comparatively few such studies in Switzerland (but see, e.g., [9, 10, 24]). This is a research gap, as the underlying correlates of high utilization may vary across health care systems (depending on, e.g., the number of inpatient beds, number of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychologists or social workers in relation to the population requiring mental health care; cf., [25, 26]) and may not be generalizable to other patient groups. Describing high utilizer patients in a respective health care systems is important to tailor evidence-based interventions to their specific characteristics and needs as well as to identify incentives and methods to change this.

In this cross-sectional study, we therefore report data from a hospital with a catchment area in a German-speaking part of Northern Switzerland, thereby focusing on the health care system of Switzerland. The aim was to provide a detailed picture of the characteristics and needs of patients retrospectively classified with a high versus low utilization pattern of psychiatric inpatient treatment. We explore socio-demographic (e.g., gender, age, living situation), psychiatric (e.g., the current primary diagnosis, comorbidities) and psychological (e.g., attitudes towards medication, the extent of (un)fulfilment regarding patients’ needs) variables, which have been associated with higher utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment in previous international studies. First, we describe patients with and without a high utilization profile ([10], cf., [11]). Secondly, we examine potential correlates of utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment with inferential statistics – including machine-learning approaches. This study therefore provides a precise description of the respective patient sample as well as an analysis of correlates of high utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment in Northern Switzerland. We intended to contribute to a broader understanding of the complex nature of this health care phenomenon in Switzerland and explore possible starting points for future research and practice in order to meet the needs of patients with multiple or long inpatient stays.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Clinic for Adults of the University Psychiatric Clinics (UPK) Basel, University of Basel, Switzerland. The clinic is a large psychiatric university hospital that provides both inpatient and outpatient mental health services to a population of approximately 200 000 individuals in the surrounding area (cf., [27]). At the time of the study, the clinic had approximately 211 beds available for inpatient treatment. Additionally, the clinic offers day clinic services and outpatient care for all patient groups. Outpatient mental health care, however, is also provided by other institution’s outpatient clinics and by an independent network of psychiatrists and psychologists working in practices (see also [28]).

Participating patients were treated in four acute psychiatric inpatient wards of the former centre for diagnostics and crisis intervention. At the time of the study, the wards specialized in the treatment of patients with acute psychoses, depressions and/or personality disorders, with or without compulsory admissions. Ethics approval was obtained from the Approval Committee “Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (EKNZ)” under protocol number EKNZ BASEC 2016–00407 (Clinical trial number: not applicable). All participants provided informed consent and the study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were recruited between August 2016 and May 2017.

Participants

Patients who had been admitted to inpatient psychiatric treatment in one of the four psychiatric wards, who were between 18–65 years old, and had a current primary diagnosis of a mental or behavioral disorder according to ICD-10 in the domains F2X (schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders), F3X (mood / affective disorders), F4X (neurotic, stress related, and somatoform disorders), or F6X (disorders of personality and behavior in adult persons) were included in the study. Patients within psychiatric day hospital treatment, patients of forensic facilities, patients with dementia or organic mental disorders (F0X) or a primary diagnosis of substance abuse (F1X), homeless patients, and/or patients with insufficient language skills or who were not able to provide informed consent were not included.

Procedure

Within one week of admission to psychiatric inpatient treatment, all eligible patients were contacted via the physician in charge. Patients were then invited to participate in the study. In the case of patients with acute psychotic symptoms, the possibility of study participation was regularly evaluated over the course of the inpatient stay and patients were invited to participate in the study at a later time, if indicated. If patients were willing to participate, a psychologist arranged a meeting in the ward and informed them about the study. The psychologist interviewed patients who provided informed consent using a semi-structured psychiatric interview that lasted between 45 and 60 min; the interview could also be divided into two sessions if the patient preferred a break. Before the interview was conducted, background information on socio-demographic details (age, gender, nationality, marital status, occupational and educational status), psychiatric (current diagnosis of mental disorder, comorbid mental disorders, somatic disorders) and treatment-related variables (frequency and duration of hospital inpatient admissions) were collected via the electronic patient files, if available, and inserted into the questionnaire. This procedure allowed us to collect data on the frequency or duration of hospital inpatient admissions during the last 30 months that might have been difficult to recall in a personal interview. However, if patients reported having utilized inpatient treatment outside of UPK Basel during the interview, this information was complemented and integrated for analyses. Furthermore, additional information was assessed (see below). Patients assigned to the four psychiatric wards several times during the recruitment period of the study were eligible to participate only once.

Materials

The assessments were done by a psychologist (trained rater) using a semi-structured interview containing the following scales on the utilization of treatment, socio-demographic, psychiatric, and psychological information. The reliability coefficients reported below refer to the sample studied in this manuscript.

Client sociodemographic and service receipt inventory (CSSRI, [29, 30])

The respondents’ use of inpatient and community-based care was recorded with the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory. The CSSRI is a questionnaire developed by Chisholm and colleagues [29], translated to German by Roick and colleagues [30], and adapted to Swiss conditions by the research and development department of the psychiatric hospital of the University of Basel. The inventory collects retrospective information on the interviewee’s utilization of health and social care services, accommodation and living situations, income, employment, and receipt of benefits, with a focus on the 6-month period preceding the assessment. Exemplary items regarding utilization of health care services focus on inpatient stays in psychiatric clinics, day clinics, and outpatient appointments.

Within this inventory we assessed utilization of inpatient treatment during the last 30 months prior to study participation. We used information from electronic patient files for inpatient stays at UPK Basel and self-reports for stays in other hospitals. For descriptive analyses, we categorized utilization into high and non-high utilization of inpatient psychiatric treatment. Based on previous research, utilization was categorized as high (HU) if a patient spent ≥ 180 days and/or at least 3 stays of at least 3 days in psychiatric inpatient treatment during the last 30 months ([10], cf., [11]). If this threshold was not met, utilization was categorized as non-high (NHU). For inferential analyses, we created the continuous target variable number of treatment days by summarizing the total number of days spent in psychiatric inpatient clinics during the last 30 months (assessed in retrospect, meaning up to the current inpatient stay).

Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS, [31])

The interviewer used the BPRS-18 to rate the current mental health status of the patients. The BPRS-scale is a general psychiatric rating scale containing 18 ordered categories of symptoms of mental illness, which are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not present, 7 = extremely severe). An overall pathology score is obtained by summing the ratings across the 18 items. The scale is widely used in clinical research [32]. It was developed in its original English version as a 16-item version [33] and has subsequently been replaced by an 18-item version [31]. We used the German version of the scale [34]. Cronbach’s alpha for the BPRS scale is 0.69. For analysis, we focused on five subscales (ECDEU, cf., [32]), namely anxiety depression (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.62), anergia (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.58), thought disturbance (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65), hostile suspiciousness (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.52), and activation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63).

Global assessment of functioning scale (GAF, [35])

Current global functioning was rated using the GAF scale. The scale serves as a clinician-rated, reliable, and valid instrument to measure axis V symptom severity or psychological, social, and occupational functioning ( [36], cf., [37]). Ratings are located on a continuum ranging from 1 to 100, with 100 indicating the highest functioning level. We used the German translation of the GAF scale by Saß and colleagues [38].

Camberwell assessment of need short appraisal (CANSAS, [39, 40])

Participants completed the CANSAS to assess the current status of their needs across 22 domains (e.g., living situation, diet, and other) within the last four weeks. For each area of need a self-reported rating is provided to indicate whether this topic is perceived as 0 = not problematic, 1 = not or only somewhat problematic as support is provided, 2 = a serious problem, or 9 = unknown. A count score can then be calculated for each patient to indicate the number of met, unmet, and total needs. CANSAS has been recognized as a valid and reliable instrument for assessing the needs of people with severe mental illness [39, 41]. We used the German translation provided by Kilian and colleagues [41].

Drug attitude inventory (DAI-10, [42, 43])

Participants also completed a self-report questionnaire consisting of 10 statements measuring the perceived effects and benefits of psychopharmacologic medication in general. Patients could indicate agreement or disagreement with each item. Higher scores indicate a more positive attitude towards and a more positive experience regarding medication. A German translation of the inventory was used in this study. Cronbach’s alpha for the DAI-10 scale is 0.69. In line with the work by Kim and colleagues [44], we computed scores for the three subscales, indicating a subjective positive response (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68), subjective negative response (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.59), and attitude to medication (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.43).

Sociodemographic questions

We interviewed participants in regards to their basic sociodemographic information using a short self-developed questionnaire. An English translation of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix A.

Additional information on the study materials and the data collection can be found in Appendix B.

Design, data preparation and statistical analyses

In this cross-sectional study, we analyzed associations between two sets of variables: patients’ utilization behavior during the last 30 months operationalized by the number of treatment days, on the one hand, and their current socio-demographic, psychiatric, and psychological variables on the other hand. For the descriptive part of the study, we report an account of the overall characteristics of the study participants and separately for patients with a treatment history categorized as HU or NHU. Categorization based on continuous outcomes is, however, associated with a loss of information. For inferential statistics, we therefore look at the continuous target variable number of treatment days. Based on the existing literature and research while keeping power and feasibility concerns in mind, we selected a priori 23 potential correlates for the regression analyses. As socio-demographic correlates, we selected gender (coded as 0 = male and 1 = female participant), age, nationality (0 = Swiss, 1 = other), family status (0 = no relationship, 1 = in a relationship), educational level (0 = low, 1 = medium, 2 = high), working situation (0 = regular labour market, 1 = protected labour market, 2 = no job), living situation (0 = assisted living, 1 = other), and receipt of disability pension (0 = no, 1 = yes). As psychiatric correlates, we selected the presence of an F2X diagnosis (0 = other, 1 = F2X diagnosis), F30/F31 diagnosis (0 = no, 1 = yes), F32/F33 diagnosis (0 = no, 1 = yes), the presence of a diagnosis of a psychiatric comorbidity (0 = no, 1 = yes), the presence of addiction as a diagnosed comorbidity (0 = no, 1 = yes), the BRPS subscales anxiety-depression, anergia, thought disturbance, activation, and hostile suspiciousness, as well as the GAF-score. As psychological and need-related correlates, we selected the three DAI subscales subjective positive response, subjective negative response, and attitude to medication. Furthermore, we computed a count score of the needs that have been identified as unmet (2 = a serious problem).

For the inferential analyses, we chose a four-step approach. First, we investigated associations between each of the 23 correlates and the target variable number of treatment days using separate univariate linear regression models to test the strength of the individual associations. Outcomes are univariate regression coefficients (βs) that can be interpreted as effect sizes as variables have been standardized. Second, to test the associations between variables when controlling for all other variables, we computed a multiple linear regression analysis. Outcomes are multivariate regression coefficients (βs) that can be interpreted as effect sizes. As classic regression models tend to result in overfitting (especially when the number of predictors is high relative to the number of cases, [45]) and thereby overestimate both the associations between correlates and target variable and the amount of variance that can be explained, we used tenfold cross validation to provide a better estimate in regards to the explanatory power of the regression model. Third, we computed a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression model (using an α-value of 0.95 and fitting the model with λ = 0.065) to provide an alternative machine learning approach to control for overfitting. LASSO regression introduces a penalization term to the estimation procedure, in which model coefficients are shrunk towards zero [45] – the method thereby allows us to determine a smaller subset of correlates that exhibit the strongest effects or associations [46]. We again estimate the model’s predictive accuracy using tenfold cross validation. Outcomes are regression coefficients (bs), controlling for all other correlates in the model. Coefficients that are not shrunk to 0 can thereby be considered to be the most relevant in explaining the variation in the outcome variable. Fourth, we applied a tree-based machine learning algorithm and used random forest models [45] to estimate the relative importance of each correlate in a non-linear setting. Outcomes are variable importance values that can be ranked according to their height (for more information on the four statistical methods, see [45]). The higher the variable importance value of a correlate, the higher its predictive power in the model.

All correlate variables were standardized before computing the statistical models. As the target variable (number of treatment days) is a count variable and therefore may not best be described by a normal distribution, we applied a log-transformation and checked for the distribution of residuals. For descriptive statistics we used IBM SPSS Statistics 27 [47], for all other analyses we used R [48] with the packages glmnet [49], caret [50], grpreg [51], and pROC [52].

Results

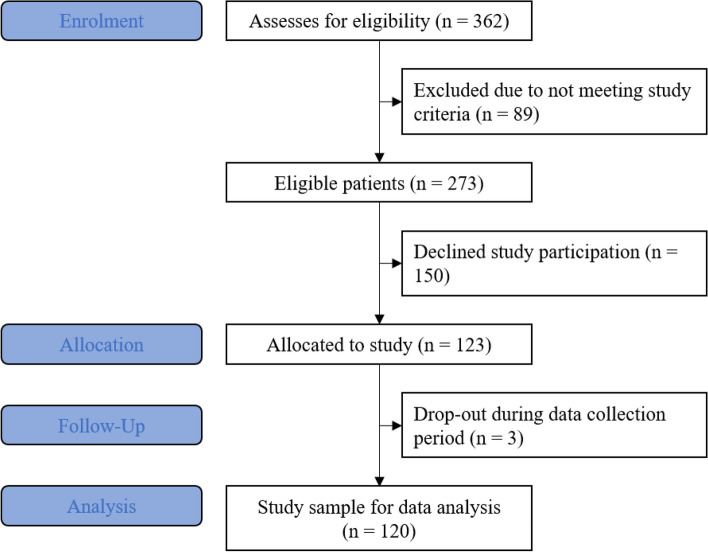

The sample of this survey consisted of 120 participants (69 male, 51 female, M age = 39.72, SD = 13.03, Range = 18–64), 30 from each of the four different psychiatric wards (see Fig. 1 for more details on the enrolment process).

Fig. 1.

Summary of enrolment process and sample formation using an adapted CONSORT flowchart for survey setups

Descriptive results

The median number of inpatient treatment days within the last 30 months (excluding the stay during this study) was 6.00. The median number of stays in inpatient psychiatric clinics including the current stay was 2. We further assessed treatment days in day clinics within the last 6 months (Md = 0) and the number of outpatient sessions in the last 6 months with a psychiatrist (Md = 4) and with a clinical psychologist (Md = 0). A detailed overview of the utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment and related services can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Utilization of psychiatric treatment and related services of the study sample (n = 120)

| Utilization of services | 10% P | 25% P | Md | 75% P | 90% P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment days in inpatient psychiatric clinics (excl. stay during study) within the last 30 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 87.00 | 178.20 |

| Number of stays in inpatient psychiatric clinics (incl. the current stay) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 6.90 |

| Treatment days in day clinics within the last 6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.80 |

| Number of outpatient contacts outside of the local clinic context within the last 6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 13.00 | 24.00 |

| Number of outpatient contacts within the local clinic context within the last 6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 |

| Number of outpatient contacts within the last 6 months provided by psychiatrists | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 13.00 | 24.00 |

| Number of outpatient contacts within the last 6 months provided by psychologists | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.80 |

| Number of complementary treatments/support within the last 6 monthsa | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.75 | 83.10 |

| Number of outpatient somatic treatments within the last 6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 7.90 |

| Number of complementary nursing home care contacts within the last 6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.70 |

Stays in forensic clinics, somatic hospitals and other support (e.g., guardianship) as well as the receipt of psychotherapy in the previous 5 years were assessed, but were outside of the focus of this manuscript and the results are therefore not presented here

Md Median, P Percentile

aComplementary treatment/support may include protected workshops, occupational therapy, contact/advice centres, social psychiatric services, self-help groups

According to the high utilization criteria, 31 participants (25.8%) showed a HU pattern and 89 (74.2%) a NHU pattern. Table 2 summarizes information on the socio-demographic characteristics of participants in general and on participants with a pattern categorized as HU or NHU.

Table 2.

Summary of sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

|

Overall

( n = 120) |

High Utilization pattern

( n = 31) |

Non-high Utilization pattern

( n = 89) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 69 (57.5%) | 17 (54.8%) | 52 (58.4%) |

| Female | 51 (42.5%) | 14 (45.2%) | 37 (41.6%) | |

| Agea |

39.72 (13.03) |

39.48 (13.50) |

39.80 (12.94) |

|

| Nationality | Swiss | 83 (69.2%) | 25 (80.6%) | 58 (65.2%) |

| Other | 37 (30.8%) | 6 (19.4%) | 31 (34.8%) | |

| Educational level | Low level (max. mandatory school) | 45 (37.5%) | 14 (45.2%) | 31 (34.8%) |

| Medium level (up to A-levels) | 64 (53.3%) | 17 (54.8%) | 47 (52.8%) | |

| High level (University degree) | 11 (9.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (12.4%) | |

| Family status | Not in a relationship | 99 (82.5%) | 26 (83.9%) | 73 (82.0%) |

| In a relationship | 21 (17.5%) | 5 (16.1%) | 16 (18.0%) | |

| Living situation | Private living situation | 87 (72.5%) | 16 (51.6%) | 71 (79.8%) |

| Assisted living situation | 29 (24.2%) | 14 (45.2%) | 15 (16.9%) | |

| Other | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (3.2%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| Working situation | Regular labour market | 25 (20.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 24 (27.0%) |

| Protected labour market | 26 (21.7%) | 11 (35.5%) | 15 (16.9%) | |

| No job | 69 (57.5%) | 19 (61.3%) | 50 (56.2%) | |

| Receipt of supportb | Yes | 91 (75.8%) | 27 (87.1%) | 64 (71.9%) |

| No | 29 (24.2%) | 4 (12.9%) | 25 (28.1%) | |

| Receipt of disability pension | Yes | 65 (54.2%) | 22 (71.0%) | 43 (48.3%) |

| No | 55 (45.8%) | 9 (29.0%) | 46 (51.7%) | |

| Contact with the police within last 6 months | Yes | 53 (44.2%) | 14 (45.2%) | 39 (43.8%) |

| No | 67 (55.8%) | 17 (54.8%) | 50 (56.2%) |

aFor this variable the statistical mean value (and standard deviation) is reported

bReceipt of support may include, e.g., unemployment benefits, social care, disability pension, or care allowances

Table 3 summarizes the psychiatric characteristics of the study participants. In general, 62 (51.7%) patients had at least one somatic disease (the average number of somatic diagnoses was 1.18, SD = 1.73), and 71 (59.2%) had an additional comorbid mental health disorder. Fifty-five (45.8%) had an F2X diagnosis and the average duration of the mental health illness was 44.92 months (SD = 74.97).

Table 3.

Summary of psychiatric characteristics of study participants

|

Overall

( n = 120) |

High Utilization pattern

( n = 31) |

Non-High Utilization pattern

( n = 89) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic diagnosis | Yes | 62 (51.7%) | 17 (54.8%) | 45 (50.6%) |

| No | 58 (48.3%) | 14 (45.2%) | 44 (49.4%) | |

| Number of somatic diagnosesa |

1.18, (1.73) |

1.26, (2.05) |

1.15, (1.61) |

|

| Psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-10) | F2X | 55 (45.8%) | 19 (61.3%) | 36 (40.4%) |

| F3X | 40 (33.3%) | 8 (25.8%) | 32 (36.0%) | |

| F4X | 8 (6.7%) | 1 (3.2%) | 7 (7.9%) | |

| F6X | 6 (5.0%) | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| F8X | 2 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

| F9X | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Missing | 8 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (9.0%) | |

| Psych. Comorbidity | Yes | 71 (59.2%) | 20 (64.5%) | 51 (57.3%) |

| No | 49 (40.8%) | 11 (35.5%) | 38 (42.7%) | |

| Addiction as comorbidity | Yes | 48 (40.0%) | 12 (38.7%) | 36 (40.4%) |

| No | 72 (60.0%) | 19 (61.3%) | 53 (59.6%) | |

| Duration of psychiatric illness in monthsa |

44.92, (74.97) (n = 79) |

71.40, (68.91) (n = 20) |

35.95, (75.36) (n = 59) |

|

| Attempts of suicide in medical history | Yes | 26 (21.7%) | 10 (32.3%) | 16 (18.0%) |

| No | 94 (78.3%) | 21 (67.7%) | 73 (82.0%) | |

| BPRS Sum-Scorea | Totala |

44.11, (11.25) |

47.16, (12.31) |

43.04, (10.73) |

| Anxiety depressiona |

14.77, (4.92) |

16.06, (5.10) |

14.31, (4.80) |

|

| Anergiaa |

6.31, (2.69) |

7.06, (2.87) |

6.04, (2.59) |

|

| Thought disturbancea |

9.15, (4.89) |

10.58, (5.82) |

8.65, (4.46) |

|

| Activationa |

6.42, (2.82) |

6.45, (2.89) |

6.40, (2.82) |

|

| Hostile suspiciousnessa |

7.47, (4.06) |

7.00, (3.99) |

7.63, (4.10) |

|

| GAF-Scorea |

30.37, (11.34) |

25.94, (10.32) |

31.91, (11.32) |

|

| Assignment to clinic | involuntary | 23 (19.2%) | 4 (12.9%) | 19 (21.3%) |

| voluntary | 95 (79.2%) | 25 (80.6%) | 70 (78.7%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

BPRS Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, GAF Global Assessment of Functioning

aFor these variables the statistical mean values (and standard deviation) are reported

Table 4 summarizes the psychological characteristics and unmet needs of the study participants. Overall, participants reported M = 3.41 unmet needs (SD = 2.69). Participants with a pattern categorized as HU reported on average 4.29 unmet needs. When looking at the different needs assessed in the study, differences of ≥ 10% points were found between participants with a pattern categorized as HU versus NHU for needs regarding the household (25.8% vs. 5.6%), daily activities (38.7% vs. 28.1%), psychotic symptoms (29.0% vs. 10.1%), social contacts (48.4% vs. 37.1%) and sexuality (45.2% vs. 27.0%; see Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of psychological characteristics and unmet needs of study participants

|

Overall

( n = 120) |

High Utilization pattern

( n = 31) |

Non-high Utilization pattern

( n = 89) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAI-Scorea | Totala |

1.23, (4.83) |

0.13, (4.95) |

1.62, (4.76) |

| Subjective positive responsea |

0.34, (2.23) |

0.23, (2.17) |

0.38, (2.26) |

|

| Subjective negative responsea |

−0.05, (2.17) |

−0.87, (2.06) |

0.24, (2.14) |

|

| Attitude to medicationa |

0.94, (2.21) |

0.77, (2.17) |

1.00, (2.24) |

|

| CANSASa | Number of unmet needsa |

3.41, (2.69) |

4.29, (3.27) |

3.10, (2.41) |

| Needs present and not met in regards to | Living situation | 7 (5.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 6 (6.7%) |

| Diet | 8 (6.7%) | 4 (12.9%) | 4 (4.5%) | |

| Household | 13 (10.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | 5 (5.6%) | |

| Personal hygiene | 10 (8.3%) | 4 (12.9%) | 6 (6.7%) | |

| Daily activities | 37 (30.8%) | 12 (38.7%) | 25 (28.1%) | |

| Physical health | 20 (16.7%) | 6 (19.4%) | 14 (15.7%) | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 18 (15.0%) | 9 (29.0%) | 9 (10.1%) | |

| Info. about illness/treatment | 9 (7.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | 8 (9.0%) | |

| Mental pressure | 62 (51.7%) | 16 (51.6%) | 46 (51.7%) | |

| Self-endangerment | 30 (25.0%) | 10 (32.3%) | 20 (22.5%) | |

| External danger | 7 (5.8%) | 3 (9.7%) | 4 (4.5%) | |

| Alcohol | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (3.2%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| Illegal drugs | 7 (5.8%) | 4 (12.9%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| Social contacts | 48 (40.0%) | 15 (48.4%) | 33 (37.1%) | |

| Relationships | 42 (35.0%) | 10 (32.3%) | 32 (36.0%) | |

| Sexuality | 38 (31.7%) | 14 (45.2%) | 24 (27.0%) | |

| Care of children | 6 (5.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 4 (4.5%) | |

| Knowledge in reading, writing, calculating | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Phone | 3 (2.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

| Transportation | 6 (5.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 4 (4.5%) | |

| Money | 22 (18.3%) | 6 (19.4%) | 16 (18.0%) | |

| Social support/benefits | 11 (9.2%) | 4 (12.9%) | 7 (7.9%) |

CANSAS Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal, DAI Drug Attitude Inventory

aFor these variables the statistical mean values (and standard deviation) are reported

Inferential statistics

Results of all models regarding correlates of the number of treatment days are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of results from various inferential analyses examining at psychiatric inpatient treatment utilization as continuous outcome variable

| Characteristic | Coding | Univariate Regression Outcomes | Multivariate Regression Outcomes | LASSO Regression Outcomes | Random Forest Outcomes a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept |

β = −0.00 (0.08), t = 0.00, p = 1.000 |

||||

| Gender |

0 = male 1 = female |

β = 0.18 (0.09), t = 1.94, p = .055 |

β = 0.24 (0.10), t = 2.33, p = .022 |

b = 0.11 | 2.85 |

| Age |

β = −0.01 (0.09), t = −0.14, p = .886 |

β = −0.04 (0.10), t = −0.39, p = .701 |

b = 0.00 | 6.80 | |

| Nationality |

0 = Swiss 1 = other |

β = −0.16 (0.09), t = −1.75, p = .084 |

β = −0.05 (0.10), t = −0.49, p = .623 |

b = −0.02 | 1.94 |

| Family status |

0 = no relat 1 = in a relat |

β = −0.12 (0.09), t = −1.36, p = .177 |

β = −0.07 (0.09), t = −0.76, p = .451 |

b = −0.02 | 1.46 |

| Educational level |

0 = low 1 = medium 2 = high |

β = −0.15 (0.09), t = −1.60, p = .112 |

β = 0.06 (0.10), t = −0.57, p = .570 |

b = −0.02 | 2.98 |

| Working situation |

0 = no job 1 = prot. lab. market 2 = reg. lab. market |

β = −0.13 (0.09), t = −1.46, p = .147 |

β = 0.04 (0.10), t = 0.37, p = .714 |

b = 0.00 | 4.01 |

| Living situation |

0 = other 1 = supported living |

β = 0.27 (0.09), t = 3.10, p = .002 |

β = 0.16 (0.09), t = 1.68, p = .097 |

b = 0.14 | 3.88 |

| Receipt of disability pension |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = 0.20 (0.09), t = 2.22, p = .028 |

β = 0.13 (0.12), t = 1.10, p = .274 |

b = 0.05 | 2.75 |

| F2X-Diagnosis |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = 0.23 (0.09), t = 2.56, p = .012 |

β = 0.09 (0.16), t = 0.55, p = .585 |

b = 0.05 | 2.62 |

| F30/F31-Diagnosis |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = −0.01 (0.09), t = −0.07, p = .943 |

β = −0.00 (0.14), t = −0.03, p = .979 |

b = 0.00 | 1.41 |

| F32/F33-Diagnosis |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = −0.24 (0.09), t = −2.71, p = .008 |

β = −0.07 (0.13), t = −0.52, p = .606 |

b = −0.08 | 2.57 |

| Mental health comorbidity |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = 0.18 (0.09), t = 2.04, p = .044 |

β = 0.09 (0.13), t = 0.70, p = .487 |

b = 0.06 | 2.43 |

| Addiction as comorbidity |

0 = no 1 = yes |

β = 0.17 (0.09), t = 1.87, p = .064 |

β = 0.10 (0.13), t = 0.83, p = .411 |

b = 0.07 | 2.36 |

| BPRS—Anxiety depression |

β = 0.07 (0.09), t = 0.74, p = .458 |

β = −0.11 (0.12), t = −0.93, p = .356 |

b = 0.00 | 6.31 | |

| BPRS—Anergia |

β = 0.16 (0.09), t = 1.75, p = .083 |

β = 0.04 (0.11), t = 0.42, p = .675 |

b = 0.00 | 5.71 | |

| BPRS—Thought disturbance |

β = 0.22 (0.09), t = 2.46, p = .016 |

β = 0.06 (0.14), t = 0.41, p = .682 |

b = 0.01 | 6.38 | |

| BPRS—Activation |

β = 0.09 (0.09), t = 1.00, p = .318 |

β = 0.02 (0.11), t = 0.21, p = .834 |

b = 0.00 | 5.11 | |

| BPRS—Hostile suspiciousness |

β = −0.00 (0.09), t = −0.01, p = .988 |

β = −0.20 (0.11), t = −1.78, p = .078 |

b = −0.06 | 6.02 | |

| GAF Score |

β = −0.29 (0.09), t = −3.23, p = .002 |

β = −0.16 (0.13), t = −1.24, p = .219 |

b = −0.13 | 8.20 | |

| DAI: Subjective positive response |

β = −0.02 (0.09), t = −0.16, p = .870 |

β = −0.11 (0.11), t = −1.01, p = .316 |

b = 0.00 | 3.23 | |

| DAI: Subjective negative response |

β = −0.19 (0.09), t = −2.16, p = .033 |

β = −0.14 (0.10), t = −1.44, p = .154 |

b = −0.08 | 4.70 | |

| DAI: Attitude to medication |

β = −0.01 (0.09), t = −0.15, p = .883 |

β = 0.08 (0.11), t = 0.70, p = .484 |

b = 0.00 | 3.64 | |

| Unmet needs |

β = 0.22 (0.09), t = 2.39, p = .018 |

β = 0.24 (0.11), t = 2.14, p = .035 |

b = 0.12 | 7.14 | |

| Overall Model Fit | - |

R 2 = .34 Adj. R 2 = .18 |

|||

| Fit after Cross-Validation | - |

R 2 = .16 RMSE = 1.02 |

R 2 = .16 RMSE = 0.97 |

R 2 = .22 RMSE = 0.94 |

Data from all participants was included in these analyses

aVariable importance values are reported

For the demographic variables, the results from the univariate regression indicated a positive association between the number of treatment days during the last 30 months and both the living situation (an assisted living situation compared to a private or other living situation), β = 0.27, as well as being the recipient of a disability pension (the receipt being positively associated with more treatment days), β = 0.20, respectively. Furthermore, significant positive associations were found between the number of treatment days, a current F2X diagnosis (β = 0.23), and the current presence of mental health comorbidities (β = 0.18). Further associations were found between the number of treatment days and a current F32/F33 diagnosis (β = −0.24), the amount of thought disturbance on the specific subscale of the BPRS (β = 0.22, with higher values being associated with more treatment days), and the GAF-score (β = −0.29, with a higher functioning level being associated with fewer treatment days). On the level of psychological attributes, we found negative associations between the number of treatment days and current subjective negative responses to medication (β = −0.19, higher values on this scale indicate less negative attitudes) and positive associations between number of treatment days and the current number of unmet needs (β = 0.22).

Applying a multiple regression model and testing associations in the context of all other correlates, our results demonstrate that only age and number of unmet needs remained correlates for the number of treatment days. This result was complemented by the LASSO regression model. The LASSO model identified living situation, the GAF-score and the number of unmet needs as three relevant correlates. The weights for the predictors age, working situation, anxiety-depression (BPRS), activation (BPRS), subjective positive responses to medication, attitude to mediation, and presence of a current F30/F31 diagnosis were all shrunk to 0.00 by the model. The Random Forest model, in turn, identified the GAF-score, unmet needs, and age as the three most important statistical correlates of number of treatment days.

The multiple regression model explained 34% of variance (R 2 = 0.34, f 2 = 0.52, cf., Table 5). Looking at values after cross validation, the models explained a range of 16 to 22% of variance (R 2 max = 0.22 for the Random Forest model).

Discussion

This study gives detailed information on inpatient utilization of patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital in a catchment area of Northern Switzerland. It provides an analysis of potential correlates of this utilization by applying different statistical models including machine learning analyses. Although our analyses explain a moderate part of the variation in the number of treatment days, the only variable that turned out to be a meaningful correlate of the number of treatment days across all statistical models applied was the number of unmet needs. Unmet needs may therefore represent a promising variable for future research designs that aim to understand and investigate strategies to prevent or reduce unnecessary psychiatric hospitalizations.

In our study, many of the unmet needs reported by participants point to social factors: Whereas only 3–7% of participants reported unmet needs in the domains of living situation, diet, phone and transportation, 40% reported unmet needs with regard to social contacts (48% HU; 37% NHU), 35% with insufficient relationships (HU 32%; NHU 36%) and 32% with regard to sexuality (HU 45%; NHU 27%). Furthermore, 31% (HU 39%; NHU 28%) of participants described unmet needs when it comes to daily activities. These findings are corroborated by an investigation of Freeman and colleagues [53], who asked patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis to choose intervention targets from a list but also allowed them to name additional targets. Almost 60% of their participants chose increasing activities as an intervention target from the list and among the additionally named targets, social connectedness and practical support was dominant [53]. Other work also highlights that social isolation and feeling lonely were the most highly endorsed unmet needs people with severe mental illness report [54]. Among the potential reasons for unmet social needs are impaired social skills, lack of opportunities to participate in social activities, and social stigma linked to mental illness.

The importance of unmet needs is in line with previous research looking at quality of life in general [55, 56] but also specifically when it comes to mental health treatment [57, 58]. While diagnoses and previous hospitalizations are linked to future hospitalizations (see [59]), self-reported ongoing struggles with symptoms [59] and the patient’s view on unmet needs could be important facets when aiming to understand the search for and utilization of psychiatric care.

The type of self-reported unmet needs are a potentially clinically relevant factor as they are modifiable and can be addressed and targeted through need-centred clinical interventions [60]. Pathare and colleagues [61] also describe this idea when introducing the term care gap (in contrast to a treatment gap which covers mostly medical treatment). The care gap highlights psychosocial interventions as important key component [62].

Psychosocial interventions, in turn, might be better implemented in community mental health services outside of hospitals [63], which could focus more on the specific unmet needs in the (social) context in which they occur (which is outside of the hospital). Tailored treatment programmes that may better target unmet needs of patients in their communities (versus traditional care based on low intensive outpatient or, in case of any crisis, high intensive hospital-centred interventions) are outreach programmes such as home treatment during a mental health crisis [64–66] or assertive community treatment [67]. The implementation of these outreach services is evidence-based and recommended in a variety of treatment guidelines (see, e.g., [68]). In Switzerland, however, home treatment and other outreach programs are not (yet) widely available in routine care settings due to the absence of a legal framework and established funding through basic health insurance [69]. This causes implementation challenges. Some programs have been implemented and others are currently being introduced, but they are primarily being offered as pilot projects [70] with different financial models.

If our study findings are replicated, future research could use randomized controlled trials within specific health systems such as the Swiss one to assess whether specific measures addressing self-reported unmet needs can reduce hospital use. First studies have shown that mental health outreach programmes such as assertive community treatment (cf., [67]) may have the potential to reduce patients’ unmet needs while providing the support within patients’ communities [60].

As a secondary finding, our descriptive analyses indicate that the patients included in this study only rarely utilized outpatient psychotherapy by a clinical psychologist in the last 6 months. This may indicate an undersupply of outpatient psychotherapy for people with severe mental illness and is in line with prior findings in the same catchment area [71].

Limitations

Given the retrospective design of the study, some limitations apply. For the inferential statistical analysis, we labeled the utilization behavior as the target variable and the psychiatric, psychological, and sociodemographic variables as correlates. This, however, is an application of statistical terms and does not reflect any causal inferences that can be derived from the results. All variables were assessed at the same time during our study, and utilization behavior over 30 months was investigated in retrospect. This may limit the amount of variance that can be explained with statistical predictor variables that might have changed during the timeframe when the behavior of seeking inpatient treatment occurred (e.g., attitudes towards medication, living situation). Longitudinal research may be conducted to examine if the correlates chosen in the study might also be predictive for future utilization of inpatient treatment.

While electronic patient records allowed us to assess precise data on inpatient treatment within our clinic, information on additional treatment outside of our clinic could not be drawn from our clinical information system. Twenty-two patients reported having additional inpatient treatment episodes in other clinics in the interview and provided estimates for dates and duration, which were integrated into the data on utilization behavior. Self-report bias with potentially missing data may, in turn, introduce additional error variance into the statistical models. Moreover, psychiatric inpatient care is a complex phenomenon that may involve many different patient and environmental factors that would need to be considered. While we offer an investigation of 23 variables, many others could still be of interest, which may explain the rather low number of explained variance. One example could be patients’ subjective perceptions about their illness. Previous work has shown that illness perceptions are associated with patients’ needs and with their health outcomes [72]. Another example could be self-stigmatization and anticipated or experiences stigmatization of mental health care personnel (e.g., [73]). Future studies could include such variables in the research and analysis plan to potentially increase the variance that can be explained in inpatient use.

We, further, cannot rule out the possibility of selection biases, as we were unable to compare study participants with non-participants treated in the relevant wards during the study period. If present, such a bias would pose a limitation in regards to the external validity of our findings [74]. Future research may aim to replicate our findings, ideally with larger sample sizes, different scales, and potentially in a different health setting. While we believe a precise description of a sample of 120 patients with severe illnesses is important to learn more about potential target groups in acute psychiatric settings, a larger sample size would be desirable to increase statistical power. Furthermore, we found that the reliability of the DAI-subscales was low, which means that given measurement uncertainty, results should be interpreted with caution and future research may identify other suitable scales to assess attitudes towards medication.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study joins a body of research examining the utilization of inpatient psychiatric treatment with the goal of better understanding high utilization patterns and tailoring treatments to the specific needs of the affected people. Results should feed into efforts to improve mental health care services for this vulnerable patient population. Given further replication, this study identifies unmet patient needs as a potential variable of interest that needs to be addressed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients who participated in this research.

Clinital trial number

Not applicable.

Appendix

Appendix A: English translation of self-developed questionnaire used for sociodemographic information

Appendix B: Additional information on study materials and procedure

The patients and interviewer completed the BPRS and GAF scale, and the CSSRI questions. The CSSRI was complemented by two questions inquiring about outpatient treatment provided by a psychologist and about outpatient psychotherapy during the last 5 years. Both questions are part of a different research project and are not the focus of this manuscript. Participants completed the CANSAS questions (CANSAS-P as it focused on the patients’ perspective) and provided answers on the DAI-10 scale. Patients were then asked three open questions about their opinion on reasons for their current stay in the psychiatric hospital, which reasons were most impactful, and what could have prevented the current stay. Participants could then ask questions and were thanked for their participation in the study.

Next to the interview itself, participants were also asked whether the researchers could contact a close family member or friend by phone for a few follow-up questions [40]. Sixty participants agreed to this procedure, however, only 41 contact persons could be reached via phone. We also conducted additional qualitative interviews with 23 participants whose behavioral pattern regarding clinic stays could be described as high utilization. Both follow-up projects were, however, not the main focus of the study and are therefore not reported in this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: JM, SW, CGH, R Luethi, SB Investigation: HS Formal analysis: MEJ, AHM, JM Resources: UEL, R Lieb, CGH, SB Supervision: R Lieb, AHM, UEL, CGH Writing – original draft: MEJ, JM Writing – review & editing: MEJ, SW, AHM, HS, R Luethi, SB, R Lieb, UEL, CGH, JM.

Funding

The research was supported by the research fund of the UPK Basel (awarded to JM and SW). The funding body had no role in the study design, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

The data is not publicly available but an anonymized version of the here presented variables can be shared upon request to any qualified researcher.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Approval Committee “Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (EKNZ)” under protocol number EKNZ BASEC 2016–00407 (Clinical trial number: not applicable). All participants provided informed consent and the study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bower P, Gilbody S. Stepped care in psychological therapies: Access, effectiveness and efficiency. Narrative literature review Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(JAN):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards DA. Stepped care: a method to deliver increased access to psychological therapies. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(4):210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wabnitz P, Schulz M, Löhr M, Nienaber A. Low-Intensity Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Psychiatr Pfl. 2017Jan 1;2(1):31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. Ambulant for Stationär. [cited 2024 Nov 12]. Ambulant vor Stationär. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/Aerztliche-Leistungen-in-der-Krankenversicherung/ambulant-vor-stationaer.html

- 5.Baumann A, Wyss K. The shift from inpatient care to outpatient care in Switzerland since 2017: Policy processes and the role of evidence. Health Policy (New York) [Internet]. 2021;125(4):512–9. Available from: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mathison LA, Seidman AJ, Brenner RE, Wade NG, Heath PJ, Vogel DL. A heavier burden of stigma? Comparing outpatient and inpatient help-seeking stigma. Stigma Heal. 2024;9(1):94–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Community mental health care in the future: Nine proposals. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(6):507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornicroft, G & Tansella M. What are the arguments for community-based mental health care ? World Heal Organ Reg Off Eur (Health Evid Netw report) [Internet]. 2003;(August):1–25. Available from: https://www.ddsp.univr.it/documenti/ArticoloRivista/allegato/allegato404733.pdf

- 9.Golay P, Morandi S, Conus P, Bonsack C. Identifying patterns in psychiatric hospital stays with statistical methods: towards a typology of post-deinstitutionalization hospitalization trajectories. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(11):1411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo SB, Huber CG, Meyer A, Weinmann S, Luethi R, Dechent F, et al. The relationship between psychological characteristics of patients and their utilization of psychiatric inpatient treatment: A cross-sectional study, using machine learning. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roick C, Gärtner A, Heider D, Dietrich S, Angermeyer MC. Heavy use of psychiatric inpatient care from the perspective of the patients affected. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006;52(5):432–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frick U, Frick H. Basisdaten stationärer psychiatrischer Behandlungen: Vertiefungsstudie “Heavy User” – Literaturanalyse (Obsan Forschungsprotokoll 5). Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium. 2008:1-131. Available from: https://www.obsan.admin.ch/sites/default/files/2021-08/forschungsprotokoll-05-heavyuser.pdf

- 13.Kastrup M. Who became revolving door patients? Findings from a nation-wide cohort of first time admitted psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76(1):80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roick C, Gärtner A, Heider D, Angermeyer MC. Heavy user psychiatrischer Versorgungsdienste. Psychiatr Prax. 2002;29(7):334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casper ES, Pastva G. Admission histories, patterns, and subgroups of the heavy users of a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Q. 1990;61(2):121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindamer LA, Liu L, Sommerfeld DH, Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Garcia P, et al. Predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with high service use in a public mental health system. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2012;39(3):200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadley TR, Culhane DP, McGurrin MC. Identifying and tracking “heavy users” of acute psychiatric inpatient services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 1992;19(4):279–90. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junghan UM, Brenner HD. Heavy use of acute in-patient psychiatric services: The challenge to translate a utilization pattern into service provision. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(SUPPL. 429):24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baillargeon J, Thomas CR, Williams B, Begley CE, Sharma S, Pollock MPHBH, et al. Medical Emergency Department Utilization Patterns Among Uninsured Patients With Psychiatric Disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):808–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rask KJ, Williams MV, McNagny SE, Parker RM, Baker DW. Ambulatory health care use by patients in a public hospital emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(9):614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kromka W, Simpson S. A Narrative Review of Predictors of Adult Mental Health Emergency Department Return Visits and Interventions to Reduce Repeated Use. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(5):671–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kne T, Young R, Spillane L. Frequent ED users: Patterns of use over time. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16(7):648–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbosa JF, Marques JG. The revolving door phenomenon in severe psychiatric disorders : A systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;69(5):1075-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Vogel S, Huguelet P. Factors associated with multiple admissions to a public psychiatric hospital. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(3):244–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker T, Kilian R. Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: What can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(SUPPL. 429):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020 [Internet]. WHO Publication. 2021. 1–136 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703

- 27.Krückl JS, Moeller J, Imfeld L, Schädelin S, Hochstrasser L, Lieb R, et al. The association between the admission to wards with open- vs. closed-door policy and the use of coercive measures. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14(October):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Tuch A, Jörg R, Stulz N, Heim E, Hepp U. Angebotsstrukturen in der psychiatrischen Versorgung: Regionale Unterschiede im Versorgungsmix. Obs Bull. 2024;03:1–8.

- 29.Chisholm D, Knapp MRJ, Knudsen HC, Amaddeo A, Gaite L, Van Wijngaarden B. Client socio-demographic and service receipt inventory - European version: Development of an instrument for international research EPSILON study 5. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(SUPPL. 39):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roick C, Kilian R, Matschinger H, Bernert S, Mory C, Angermeyer MC. Die deutsche Version des Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory. Psychiatr Prax. 2001;28(2):84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overall JE. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in psychopharmacology research. In: Pichot P, Olivier-Martin R, editors. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology. Basel: S. Karger; 1974. p. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafer A. Meta-analysis of the brief psychiatric rating scale factor structure. Psychol Assess. 2005;17(3):324–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10(3):799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maß R, Burmeister J, Krausz M. Dimensionale Struktur der deutschen Version der Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Nervenarzt. 1997;68(3):239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, Dunn G. A brief mental health outcome scale. Reliability and validity of the global assessment of functioning (GAF). Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(MAY):654–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Startup M, Jackson MC, Bendix S. The concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41(4):417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lange C, Heuft G. Die Beeinträchtigungsschwere in der psychosomatischen und psychiatrischen Qualitätssicherung: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) vs. Beeinträchtigungs-Schwere-Score (BSS). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2002;48(3):256–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saß H, Wittchen HU, Zaudig M. Diagnostisches und Statistisches Manual Psychischer Störungen DSM-IV. 2nd ed. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCrone P, Leese M, Thornicroft G, Schene AH, Knudsen HC, Vázquez-Barquero JL, et al. Reliability of the Camberwell Assessment of Need - European Version EPSILON study 6. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(SUPPL. 39):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phelan M, Slade M, Thornicroft G, Dunn G, Holloway F, Wykes T, et al. The Camberwell Assessment of Need The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(NOV):589–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kilian R, Bernert S, Matschinger H, Mory C, Roick C, Angermeyer MC. Die standardisierte Erfassung des Behandlungs- und Unterstützungsbedarfs bei schweren psychischen Erkrankungen - Entwicklung und Erprobung der deutschsprachigen Version des Camberwell Assessment of Need-EU. Psychiatr Prax. 2001;28(2):79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Awad AG. Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(3):609–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: Reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13(1):177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JH, Kim SY, Ahn YM, Kim YS. Subjective response to clozapine and risperidone treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(2):301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tibshiranit R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso [Internet]. Vol. 58, J. R. Statist. Soc. B. 1996. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jrsssb/article/58/1/267/7027929

- 47.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY; 2020.

- 48.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria.: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

- 49.Friedman, J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Narasimhan B, Tay, K, Simon, N, Qian, J, Yang, J. Package “glmnet.” 2022. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/glmnet.pdf

- 50.Kuhn M, Wing J, Weston S, Williams A, Keefer C, Engelhardt A, et al. Package “caret.” 2022. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/caret/caret.pdf

- 51.Breheny P, Zeng Y, Kurth R. Package “grpreg.” 2021. Availa from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/grpreg/grpreg.pdf

- 52.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. Package “pROC.” 2021. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/grpreg/grpreg.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Freeman D, Taylor KM, Molodynski A, Waite F. Treatable clinical intervention targets for patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2019Sep;1(211):44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fortuna KL, Ferron J, Pratt SI, Muralidharan A, Aschbrenner KA, Williams AM, et al. Unmet Needs of People with Serious Mental Illness: Perspectives from Certified Peer Specialists. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(3):579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slade M, Leese M, Taylor R, Thornicroft G. The association between needs and quality of life in an epidemiologically representative sample of people with psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(2):149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slade M, Leese M, Ruggeri M, Kuipers E, Tansella M, Thornicroft G. Does meeting needs improve quality of life? Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(3):183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiersma D, van Busschbach J. Are needs and satisfaction of care associated with quality of life? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Migliorini C, Fossey E, Harvey C. Self-reported needs of people living with psychotic disorders: Results from the Australian national psychosis survey. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1013919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernardo AC, Forchuk C. Factors associated with readmission to a psychiatric facility. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(8):1100–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kortrijk HE, Kamperman AM, Mulder CL. Changes in individual needs for care and quality of life in Assertive Community Treatment patients: An observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pathare S, Brazinova A, Levav I. Care gap: A comprehensive measure to quantify unmet needs in mental health. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018Oct 1;27(5):463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Pinho Zanardo GL, Moro LM, Ferreira GS, Rocha KB. Factors associated with psychiatric readmissions: A systematic review. Paideia. 2018;28:e2814.

- 63.Murray V, Walker HW, Mitchell C, Pelosi AJ. Needs For Care From A Demand Led Community Psychiatric Service: A Study Of Patients With Major Mental Illness. British Medical Journal. 1996;312(7046):1582-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Stulz N, Wyder L, Maeck L, Hilpert M, Lerzer H, Zander E, et al. Home treatment for acute mental healthcare: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2020Jun 1;216(6):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glover G, Arts G, Babu KS. Crisis resolution/home treatment teams and psychiatric admission rates in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189(NOV):441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murphy S, Irving CB, Adams CE, Driver R. Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5(5):01087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to Mental Hospital Treatment I. Conceptual Model, Treatment Program, and Clinical Evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG178 [PubMed]

- 69.Jäger M. Home Treatment - Krisenintervention zu Hause. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung [Internet]. 2023;(10):75–6. Available from: https://saez.swisshealthweb.ch/de/article/doi/saez.2023.21445/

- 70.Gavrilovic Haustein N, Jäger M. Home-Treatment-Modelle in der Schweiz. Lead Opin Neurol Psychiatr. 2024;04:52. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jaffé ME, Loew SB, Meyer AH, Lieb R, Dechent F, Lang UE, et al. Just Not Enough: Utilization of Outpatient Psychotherapy Provided by Clinical Psychologists for Patients With Psychosis and Bipolar Disorder in Switzerland. Heal Serv Insights. 2024;17:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Broadbent E, Kydd R, Sanders D, Vanderpyl J. Unmet needs and treatment seeking in high users of mental health services: role of illness perceptions. Vol. 42, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Chukwuma O V, Ezeani EI, Fatoye EO, Benjamin J, Okobi OE, Nwume CG, et al. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Stigmatization on Psychiatric Illness Outcomes. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.McEwan B. Sampling and validity. Ann Int Commun Assoc [Internet]. 2020;44(3):235–47. Available from: 10.1080/23808985.2020.1792793

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not publicly available but an anonymized version of the here presented variables can be shared upon request to any qualified researcher.