ABSTRACT

Background

Lymph node metastasis is closely associated with the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study aimed to evaluate the role of preoperative 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) parameters in mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC.

Methods

One hundred patients with NSCLC who underwent surgery, systematic lymph node dissection, who had undergone 18FFDG PET/CT for initial staging were divided into two groups: lymph node metastasis and non-metastasis. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), average standardized uptake value (SUVmean), SUV in the liver (SURliver), mediastinal blood pool (SURblood), metabolic tumor volume (MTV), and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) were detected in both groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the parameters for predicting the diagnostic efficacy.

Results

The SUVmax, SUVmean, SURblood, SURliver, MTV, and TLG were higher in the group with lymph node metastasis than in the group without lymph node metastasis. The ROC analysis showed that 18F-FDG PET/CT demonstrated acceptable predictive ability with AUC of 0.964 (95% CI, 0.930–0.998).

Conclusions

The relative 18F-FDG PET/CT primary uptake and substitution parameters showed acceptable predictive efficacy for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in patients with NSCLC. Additional, SURblood has potential for clinical application.

KEYWORDS: Non-small cell lung cancer, 18F-FDG PET/CT, SUVmax, SUVmean, SURblood, SURliver

1. Introduction

Lung cancer, including non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is a malignant tumor originating in the bronchial mucosa or glands [1]. Despite advances in its diagnosis, staging, and treatment, NSCLC remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths [2]. Studies have shown that lymph node metastasis is closely related to the prognosis of patients with NSCLC, and that the 5-year survival rate of patients with mediastinal lymph node metastasis is only 12.4% [3]. For patients with NSCLC without distant metastasis, surgery is the best treatment, and lymph node metastasis before surgery, lymph node dissection, and postoperative chemotherapy can improve patient prognosis [4]. Therefore, timely and accurate preoperative diagnosis of patients with lymph node metastasis is very important.

Medical imaging plays a key role in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC [5]. Imaging parameters such as biomarkers are noninvasive, simple, and reproducible, which is conducive to guiding clinical decision-making [6]. Positron emission tomography – computed tomography (PET/CT) has been used to evaluate the progression of most malignant tumors by integrating the anatomical location data with molecular functional metabolic data. This method can detect metabolic changes in the tumor tissue before the anatomical changes become evident in conventional imaging [7, 8]. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography – computed tomography (PET/CT), as a noninvasive imaging method, can simultaneously provide the metabolic level and anatomical information of patients at the same time to achieve semi-quantitative analysis of lesions and has been widely used in the staging and prognostic assessment of lung cancer, breast cancer, osteosarcoma, and other tumor diseases [9–12]. 18F-FDG, a glucose analog, is a common clinical metabolic tracer. The increase in glycolysis in most malignant tumors is due to the upregulation of the glucosaccharide transporter and the increase in hexokinase activity on the tumor cell membrane, which mediates FDG to form L8F-F-G-6-phosphate by hexokinase phosphorylation in tumor cells [13–15]. 18F-FDG cannot be transferred to the next metabolic process by fructose phosphate; therefore, it is trapped in tumor cells [16]. Due to cell proliferation, microvascular density, hypoxia, necrosis, tumor microenvironment, cell migration, and intercell interactions in tumor tissues, cytokines can alter glucose metabolism in tumors [17]. PET/CT can detect the radiation distribution and concentration of 18 F-FDG in the human body and reveal the spatial heteroplasms of glucose taken in tumors [18].

Studies of 18 F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters for the diagnosis of lung cancer have also been reported [19, 20]. In addition, the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), average standardized uptake value (SUVmean) has been shown to be a useful predictor of lymph node metastasis [21]. However, few studies have assessed mediastinal lymph node metastasis using the standardized uptake ratio (SUR) between focal SUV and SUV in the liver (SURliver) or mediastinal blood pool (SURblood). In the present study, we measured SUVmax, SUVmean, SURblood, and SURliver using 18 F-FDG PET/CT. This study investigated the predictive value of preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Between January 2023 and May 2024, a total of 100 patients (73 men and 27 women; mean age, 66.24 ± 9.62 years) with NSCLC who underwent PET/CT examination and underwent surgery, systemic lymph node dissection and pathological diagnosis within 2–4 weeks were diagnosed in The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, and were identified and enrolled in the concurrent group. In addition, the enrolled patients were further categorized into metastatic (n = 32) and non-metastatic (n = 68) groups. Patients who met the following criteria were included in the study: (1) those with clinically diagnosed NSCLC according to the Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of NSCLC by the Chinese Medical Association, and (2) those who did not undergo chemoradiotherapy before examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of other primary tumors, (2) N3 lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis, and (3) mental or speech communication disorders (Figure 1). This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (approval code: 2022–147) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all patients or their family members.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flowchart.

2.2. 18F-FDG PET/CT

All patients underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT after 6–8 h of fasting. Patients’ blood sugar levels were less than 180 mg/dL prior to imaging. After intravenous injection of 18 F⁃FDG (3.7–4.4 MBq/kg), imaging was performed after resting for 45–60 min. Plain CT images (140 kVp, 129 mA, slice thickness: 1.25 mm) were collected. PET images were collected (2–3 min per bed position) and the images were finally fused. Two professional reviewers evaluated 18F-FDG PET/CT images. Two professional reviewers carried out multi-directional recombination of the images, set the lung window and selected the largest layer to measure the maximum diameter of the primary lesion. The relative threshold method (40% as the threshold value) was adopted to outline the primary lesion. Based on previous studies, the SUVmax, SUVmean, and MTV of the primary tumors were calculated [22]. The SUVmax, SUVmean, and MTV of the primary tumors were calculated. MTV (cm3) was defined as the total volume of the tumor used to calculate the outline of the tumor. The ratios of blood pool SUVmean, liver SUVmean, SUVmax to mediastinal blood pool SUVmean (SURblood), and primary SUVmax to liver SUVmean (SURliver) were calculated. TLG values (g) were calculated by multiplying the SUVmean by the MTV.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For the numeric variables that were normally distributed, comparison between two groups was made by independent sample t test, and the Chi-square test was used to analyze the categorical data, and descriptive statistics were presented as frequency (%). Risk factors for mediastinal lymph node metastasis were analyzed using univariate logistic regression. The diagnostic value of these metabolic parameters were evaluated respectively using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves according to the area under the ROC curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate analysis of clinical data related with lymph node metastasis

We analyzed the clinical data of the two groups of patients, and the results showed no significant correlation between lymph node metastasis and patient age, sex, smoking history, or pathological pattern (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of clinical data related factors and lymph node metastasis.

| Group | Subgroup | Metastasis (n = 32) | non-metastasis (n = 68) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 66.10 ± 10.21 | 65.01 ± 10.34 | 0.965 | |

| Gender (%) | male | 24 (75.0) | 53 (77.9) | 0.744 |

| female | 8 (25.0) | 15 (22.1) | ||

| Smoking history (%) | Yes | 16 (50.0) | 36 (52.9) | 0.784 |

| No | 16 (50.0) | 32 (47.1) | ||

| Pathological pattern (%) | Adenocarcinoma | 13 (40.6) | 40 (59.6) | 0.089 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 19 (59.4) | 28 (40.4) |

3.2. Univariate analysis of PET/CT parameters related with lymph node metastasis

We then compared the PET/CT parameters of the primary lesion between the two groups and found that the maximum diameter, SUVmax, SUVmean, SURblood, and SURliver in patients with lymph node metastasis were significantly larger than those in the non-metastatic group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of PET/CT parameters and lymph node metastasis.

| Index | Metastasis (n = 32) |

non-metastasis (n = 68) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter max | 3.66 (2.19, 5.05) | 2.73 (2.06, 3.39) | <0.01 |

| SUVmax | 10.16 (6.68, 14.28) | 5.95 (2.08, 9.97) | <0.01 |

| SUVmean | 4.86 (2.73, 6.84) | 3.29 (1.70, 4.94) | <0.01 |

| SURblood | 8.23 (4.58, 10.84) | 3.29 (1.78, 4.96) | <0.01 |

| SURliver | 5.21 (3.13, 7.43) | 3.34 (1.60, 4.73) | <0.01 |

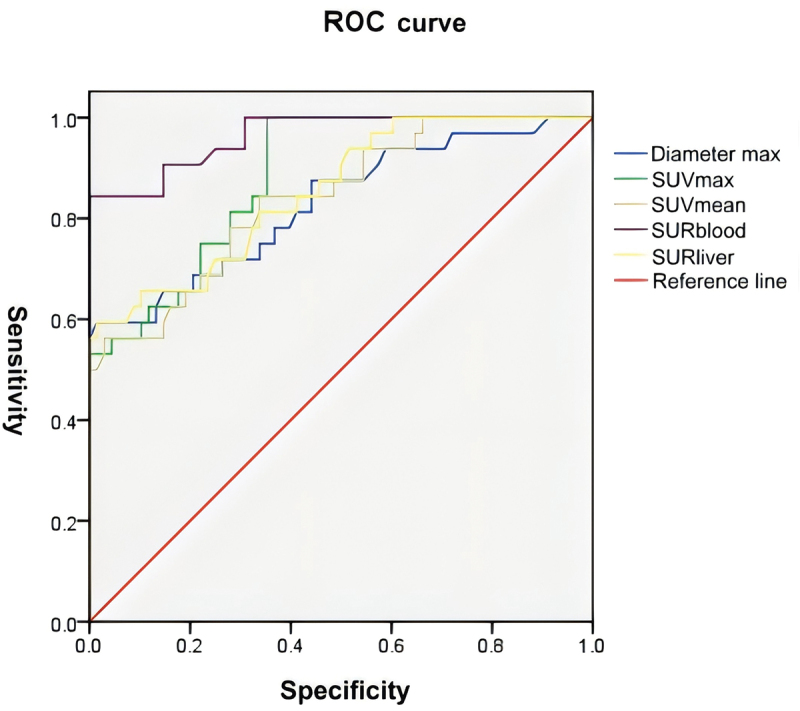

3.3. Evaluation of clinical value of PET/CT parameters in mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC

To evaluate the diagnostic value of the PET/CT parameters, ROC curves were generated for patients with and without lymph node metastasis. The results showed that the diameter, SUVmax, SUVmean, SURblood and SURliver all had high diagnostic accuracies, with AUC of 0.828 ((95% CI, 0.735–0.921); sensitivity, 71.9%; specificity, 66.2%) and cutoff value of 2.88, 0.883 ((95% CI, 0.818–0.947); sensitivity, 84.4%; specificity, 67.6%) and cutoff value of 7.15, 0.839 ((95% CI, 0.756–0.923); sensitivity, 84.4%; specificity, 66.2%) and cutoff value of 3.85, 0.964 ((95% CI, 0.930–0.998); sensitivity, 100.0%; specificity, 70.6%) and cutoff value of 4.02, and 0.854 ((95% CI, 0.774–0.933); sensitivity, 78.1%; specificity, 66.2%) and cutoff value of 4.05, respectively (Figure 2). Among them, the AUC of SURblood was the largest, with an optimal cutoff value of 4.02.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of clinical value of PET/CT parameters in mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC. ROC curve based on PET/CT parameters.

4. Discussion

According to statistics, lung cancer ranks second in the incidence of malignant tumors, and the fatality rate ranks first [23]. It is the leading cause of cancer incidence and death in men and ranks third in cancer incidence (behind breast and colorectal cancer) and second in mortality (behind breast cancer) in women [23]. In China, lung cancer still has the highest incidence and mortality of all cancers, and men are also higher than women [24]. About 85% of lung cancers are NSCLC. After surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and other treatment, the 5-year survival rate of most patients with advanced NSCLC is still low [25]. Despite advances in diagnosis, staging, and treatment, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death.

The gold standard for diagnosing the histological subtype of lung cancer tissue is through fine needle aspiration, biopsy, or surgery [26]. However, these methods are invasive and traumatic, and when surgery is not indicated, relying solely on small samples of tumor tissue for biopsy and cytological examination cannot fully represent the entire tumor histological properties, making it difficult to accurately characterize the spatial heterogeneity of the tumor [26]. Additionally, when the tumor is located deep within the lungs or near the bronchi or blood vessels, or when the patient’s condition is poor, biopsy is not suitable, and it is not practical to evaluate treatment outcomes through repeated biopsy [27]. Furthermore, histological examination of hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stained sections is not always accurate, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) as an auxiliary diagnostic method for HE staining, although effective in 60%-100% of lung cancer tissues, also has disadvantages such as a long detection time, difficulty in interpreting the results, and high tissue consumption for individual markers [28]. Therefore, a noninvasive, convenient method is needed to accurately distinguish NSCLC histological subtypes to meet clinical treatment requirements.

Thin-section CT (TSC CT) can better display the fine structural and morphological features of lung nodules, and has a higher sensitivity for detecting small lung nodules, which is helpful for distinguishing the nature of nodules [29]. Image-based phenotypic analysis is a promising noninvasive method for predicting the histological subtype of NSCLC [30]. It has been reported that cavitation is more closely related to NSCLC, and the air branch air duct sign is the main CT feature of Lung adenocarcinoma [31]. However, these CT signs, based on the observer’s visual assessment, are mixed or overlapping in different histological types and do not provide functional information about the tumor.

PET/CT is a technology that quantifies the high-throughput data of PET and CT visual images, which can analyze the characteristics and biological information of lesions that cannot be identified by the naked eye, and has been gradually applied to the identification of benign and malignant lesions, tumor progression and type analysis and other fields [32]. Its process mainly includes image acquisition, image segmentation, feature extraction, feature processing, model establishment and verification. Common feature types include histogram feature, texture feature, change feature and shape feature [32]. 18F-FDG PET/CT has the advantages of noninvasive, dynamic and whole-body, which can make up for the limitations of pathology, CT, magnetic resonance imaging and other conventional techniques, and has a good application prospect in the prediction of immunotherapy efficacy of NSCLC [33].

18F-FDG PET/CT has certain application value in NSCLC patients’ post-treatment status, long-term survival, prediction and micro-environment assessment of disease immunity, which can make up for the shortcomings of pathology and traditional CT, magnetic resonance imaging and other imaging methods [34]. The clinicopathologic multimodal imaging model is used to promote the accurate direction of NSCLC immunotherapy [34]. Although the predictive value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in immunotherapy of NSCLC has been confirmed in many studies, it still faces many difficulties and challenges. First of all, 18F-FDG PET/CT images are acquired by PET/CT scanners with different parameters and models, which may affect the parameter characteristics of images. However, it is precisely this heterogeneity that reduces the overfitting of the model and ensures its stability and universality [35]. Additional, most of the images use manual outline of the area of interest and manual image segmentation, which has high technical requirements for operators and poor reproducibility. The development of automatic segmentation technology and machine learning in recent years may better solve this problem [36]. Moreover, clinical follow-up outcomes are often used as the gold standard for predicting outcomes. However, due to the fact that most of the studies were retrospective and some patients stopped immunotherapy due to early treatment failure, the follow-up time was insufficient, and the delayed tumor response could not be evaluated. There are also studies using 18F-FDG PET/CT follow-up as the baseline prediction criterion, but it is not commonly used in clinical practice and there is patient selection bias [37].

At present, for patients with early NSCLC, anatomical lobectomy combined with systematic lymph node dissection is the standard treatment strategy, which has been widely recognized by thoracic surgeons [38]. However, some patients may have difficulty tolerating lobectomy due to advanced age or underlying medical conditions, and others may refuse invasive surgery [39]. In these cases, limited surgery (cuneiform resection or segmentectomy) or SBRT may become treatment options for such patients. Sublobectomy can effectively preserve more lung tissue, significantly shorten the postoperative recovery time, and improve the quality of life. There were significant differences in the incidence of cardiovascular events and surgery-related complications such as chylothorax/lymphorrhagia and perioperative mortality between patients undergoing lobectomy and sublobectomy [40]. SBRT is a noninvasive treatment method and a new treatment method for patients who are not suitable for invasive treatment, which has been widely accepted in clinic and its efficacy is also guaranteed [41]. However, an important prerequisite for receiving SBRT or restricted surgery is that the mediastinal lymph nodes are pathologically negative [41]. If preoperative imaging can identify mediastinal lymph node metastasis, then patients may benefit from aggressive tailored treatment such as lobectomy, intensive lymph node dissection, and postoperative chemotherapy to improve clinical outcomes and reduce recurrence and death [42]. In summary, for patients with early NSCLC, the accurate judgment of pathological lymph node staging before surgery is very important.

Radiomics can extract quantitative imaging features from medical images to characterize tumor pathology or heterogeneity, which is becoming increasingly popular in medical image analysis [43]. Machine learning models based on radiomics features have the potential to distinguish ADC, however, most radiomics studies typically use a single modeling approach, which may affect prediction results. Furthermore, relying solely on radiomics is one-sided [44]. Therefore, extracts radiomics features from PET-combined TSC CT dual-modality images and combines four machine learning algorithms to establish multiple models with the aim of improving the accuracy of radiomics prediction of histological subtypes. Then, it further integrates PET/CT radiomics, clinical, and radiological features to construct a nomogram for personalized prediction.

The imaging diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC patients mainly refers to the parameters of lymph node metabolism, size, morphology and density, which mainly depends on the clinical experience of the diagnostic physician [45]. In other words, traditional imaging diagnostic practice is essentially the visual evaluation, analysis and interpretation of images. 18F-FDG PET/CT, as a nonspecific functional molecular imaging, can provide glucose metabolism information for the display of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with NSCLC [34]. However, abnormal uptake of false positivity caused by infectious lesions, nonspecific inflammation, granulomatous hyperplasia and other diseases is not uncommon, and often brings great interference to clinical diagnosis. The main molecular and pathological mechanisms of abnormal uptake of 18F-FDG in benign mediastinal lymph nodes are lymphoid follicular hyperplasia and histiocytic infiltration associated with Glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) overexpression [46]. When benign mediastinal lymph nodes present with false positive uptake on PET imaging, and the morphological information provided by low-dose CT is insufficient to support the judgment, the risk of misdiagnosis will be significantly increased [46]. When mediastinal lymph node metastases are too small to exceed the resolution of PET/CT, they may not be recognized by the naked eye, which is called occulted lymph node metastases. In addition, some mediastinal lymph node metastases can be shown on CT, but there may be no obvious abnormal 18F-FDG uptake, which may also lead to diagnostic errors [21]. Occult lymph node metastasis and the presence of abnormal uptake of benign lymph nodes can present a challenge for mediastinal lymph node staging of NSCLC based on an empathetic assessment of 18F-FDG PET/CT, and this challenge is repeated almost every working day [47].

The 18 F-FDG PET/CT as molecular imaging has been widely used for diagnosis, staging and rescheduling of NSCLC patients, mapping of radiotherapy targets, and evaluating therapeutic efficacy and prognosis. Several related semi-fixed metabolic parameters, such as SUVmax, SUVme an, TLG, and MTV, have been shown to be promising ET/CT indicators of metabolic activity and/or tumor load [48]. As a advantageous imaging technology, the 18 F-FDG PET/CT can not only provide the size, shape, and density parameters of the lesion, but also provide the activity of the lesion [49]. For patients diagnosed with NSCLC, accurate staging of lymph nodes is a key guide in the selection of an optimal and precise treatment regimen [49]. Studies have shown that CT has been used for patients with NSCLC and lymph node metastasis [50]. However, CT is mainly based on the size of the lymph nodes for morphological evaluation, and there are certain limitations to the identification of occult lymph nodes. Tumors with a high degree of displacement are often accompanied by the formation of peripheral and basilar ducts, which increase tumor aggressiveness [51]. In this study, we found that all PET/CT metabolic parameters had good predictive efficacy for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in patients with NSCLC and that univariate analysis was a risk factor for mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

SUV-based parameters are susceptible to many factors, such as individual patient factors, injection dose, scanner characteristics, and recombination algorithms [52]. Therefore, more stable and reproducible methods are required. The present study found that SURblood was an independent predictor of mediastinal lymph node metastasis, and its diagnostic efficacy was the highest (AUC = 0.964; sensitivity, 100.0%; specificity, 70.6%), indicating the potential clinical value of SURblood for lymph node metastasis in NSCLC patients.

This study had some limitations. First, the sample size was limited and may not be representative of all patients. Second, this study used single-center data with no external validation, which may have lowered the general suitability of the diagnostic model. Furthermore, this study should be followed by stratified studies based on the maximum diameter of the primary lesion and pathological type.

5. Conclusions

The 18 F-FDG PET/CT parameters have acceptable predictive values for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in patients with NSCLC. Among them, SURblood is an independent predictor of mediastinal lymph node metastasis, and its predictive ability is better than that of other parameters, with potential clinical application potential.

Article highlights

There were no significant correlation between lymph node metastasis and patient general.

There was no significant correlation between lymph node metastasis and pathological type.

The 18 F-FDG PET/CT parameters had acceptable predictive values for mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

SURblood had ideal predictive efficacy and potential clinical application value.

Author contribution

Yingrui Su and Xiaopeng Yu led analysis and writing of the manuscript. Jianlin Wang, Liqun Huang and Long Xie performed experimental operations. Yingrui Su supervised the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval (Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (approval code: 2022–147)) and/or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Jonna S, Subramaniam DS.. Molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an update. Discov Med. 2019;27(148):167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Herbst RS, Boshoff C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1345–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song H, Yoon SH, Kim J, et al. Application of N descriptors proposed by the international association for the study of lung cancer in clinical staging. Radiology. 2021;300(2):450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun J, Wu S, Jin Z, et al. Lymph node micrometastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;149:112817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madani MH, Riess JW, Brown LM, et al. Imaging of lung cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2023;47(2):100966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele KE, Tan TH, Korn R, et al. Measuring multiple parameters of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human cancers by image analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eze C, Schmidt-Hegemann NS, Sawicki LM, et al. PET/CT imaging for evaluation of multimodal treatment efficacy and toxicity in advanced NSCLC-current state and future directions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(12):3975–3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flechsig P, Lindner T, Loktev A, et al. PET/CT imaging of NSCLC with a α(v)β(6) integrin-targeting peptide. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21(5):973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cengiz A, Yersal Ö, Ömürlü İK, et al. Prognostic role of metabolic 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters and hematological prognostic indicators in patients with colorectal cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2023;60(2):224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The reason for the interesting reference is that it describes how 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters can be used to predict prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. It is helpful for the diagnosis and treatment of other cancers.

- 10.Paydary K, Seraj SM, Zadeh MZ, et al. The evolving role of FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of breast cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh C, Bishop MW, Cho SY, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the management of osteosarcoma. J Nucl Med. 2023;64(6):842–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grambozov B, Kalantari F, Beheshti M, et al. Pretreatment 18-FDG-PET/CT parameters can serve as prognostic imaging biomarkers in recurrent NSCLC patients treated with reirradiation-chemoimmunotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2023;185:109728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The reference is of considerable interest because 18F-FDG-PET/CT parameters can predict lymph node metastasis in NSCLC patients. This study laid the theoretical foundation.

- 13.Kaanders J, Bussink J, Aarntzen E, et al. [18F] FDG-PET-Based personalized radiotherapy dose prescription. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2023;33(3):287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abouzied MM, Crawford ES, Nabi HA. 18F-FDG imaging: pitfalls and artifacts. J Nucl Med Technol. 2005;33(3):145–155; quiz 162–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosales JJ, Toledano C, Riverol M, et al. [18F]-FDG PET imaging in autoimmune GFAP meningoencephalomyelitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(3):947–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crimì F, Valeggia S, Baffoni L, et al. [18F]FDG PET/MRI in rectal cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2021;35(3):281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seban RD, Synn S, Muneer I, et al. Spleen Glucose Metabolism on [18F]-FDG PET/CT for cancer drug discovery and development cannot be overlooked. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2021;21(11):944–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iqbal R, Yaqub M, Bektas HO, et al. [18F]FDG and [18F]FES PET/CT imaging as a biomarker for therapy effect in patients with metastatic ER+ breast cancer undergoing treatment with Rintodestrant. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(11):2075–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castello A, Rossi S, Lopci E. 18F-FDG PET/CT in restaging and evaluation of response to therapy in lung cancer: state of the art. Curr Radiopharm. 2020;13(3):228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This reference is of interest because the 18F-FDG parameter appears to be a promising factor for assessing lung cancer treatment response and detecting recurrence. These provide a theoretical basis for this study.

- 20.Hockmann J, Hautzel H, Darwiche K, et al. Accuracy of nodal staging by 18F-FDG-PET/CT in limited disease small-cell lung cancer. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2023;31(6):506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hua J, Li L, Liu L, et al. The diagnostic value of metabolic, morphological and heterogeneous parameters of 18F-FDG PET/CT in mediastinal lymph node metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2021;42(11):1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This reference is of interest because it reveals that the 18F-FDG PET/CT parameter helps to accurately distinguish mediastinal lymph node metastases in non-small cell lung cancer, which can improve diagnostic accuracy. This is of reference value to our research.

- 22.Park GC, Kim JS, Roh JL, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic tumor volume measured by 18F-FDG PET/CT in advanced-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2024;4(1):47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung cancer 2020: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasim F, Sabath BF, Eapen GA. Lung cancer. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Wu X, Yang P, et al. Machine learning for lung cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2022;20(5):850–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Salvia A, Meyer ML, Hirsch FR, et al. Rediscovering immunohistochemistry in lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;200:104401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwamoto R, Tanoue S, Nagata S, et al. T1 invasive lung adenocarcinoma: thin-section CT solid score and histological periostin expression predict tumor recurrence. Mol Clin Oncol. 2021;15(5):228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hattori A, Suzuki K, Takamochi K, et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer with radiologically pure-solid appearance in Japan (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a post-hoc supplemental analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(2):105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi W, Liu CJ, Alam SR, et al. Preoperative (18)F-FDG PET/CT and CT radiomics for identifying aggressive histopathological subtypes in early stage lung adenocarcinoma. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:5601–5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evangelista L, Sepulcri M, Pasello G. PET/CT and the Response to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer. Curr Radiopharm. 2020;13(3):177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farsad M. FDG PET/CT in the staging of lung cancer. Curr Radiopharm. 2020;13(3):195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owens C, Hindocha S, Lee R, et al. The lung cancers: staging and response, CT, (18)F-FDG PET/CT, MRI, DWI: review and new perspectives. Br J Radiol. 2023;96(1148):20220339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma R, Zhao Q, Zhao R, et al. Integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT parameter defines metabolic oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2022;43(9):1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang F, Wu X, Zhu J, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT and circulating tumor cells in treatment-naive patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(10):3250–3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This reference is of particular interest because it confirms that 18F-FDG PET/CT is superior to CTC in diagnosing NSCLC patients. This lays the foundation for the correctness of our research direction.

- 37.Simsek FS, Comak A, Asik M, et al. Is FDG-PET/CT used correctly in the combined approach for nodal staging in NSCLC patients? Niger J Clin Pract. 2020;23(6):842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eren G, Kupik O. Necrosis onstaging 18F FDG PET/CT is associated with worse progression-free survival in patients with stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022;18(4):971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, Dong S, Li X, et al. Clinical utility of dual-energy CT used as an add-on to 18F FDG PET/CT in the preoperative staging of resectable NSCLC with suspected single osteolytic metastases. Lung Cancer. 2020;140:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin X, Li J, Chen B, et al. The predictive value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT combined with inflammatory index for major pathological reactions in resectable NSCLC receiving neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2023;186:107389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeda A, Kunieda E, Fujii H, et al. Evaluation for local failure by 18F-FDG PET/CT in comparison with CT findings after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for localized non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;79(3):248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Infante JR, Cabrera J, Rayo JI, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT quantitative parameters as prognostic factor in localized and inoperable lung cancer. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol (Engl Ed). 2020;39(6):353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mu W, Tunali I, Gray JE, et al. Radiomics of (18)F-FDG PET/CT images predicts clinical benefit of advanced NSCLC patients to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47(5):1168–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monaco L, De Bernardi E, Bono F, et al. The “digital biopsy” in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a pilot study to predict the PD-L1 status from radiomics features of [18F]FDG PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49(10):3401–3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown S, Banfill K, Aznar MC, et al. The evolving role of radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1104):20190524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzawa N, Ito M, Qiao S, et al. Assessment of factors influencing FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer on PET/CT by investigating histological differences in expression of glucose transporters 1 and 3 and tumour size. Lung Cancer. 2011;72(2):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt-Hansen M, Baldwin DR, Hasler E, et al. PET-CT for assessing mediastinal lymph node involvement in patients with suspected resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):Cd009519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Dong M, Sun X, et al. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in surgical non-Small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0146195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kandemir O, Demir F. An investigation of the relationship between 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters of primary tumors and lymph node metastasis in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Radiopharm. 2024;17(1):111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng X, Shao J, Zhou L, et al. A comprehensive nomogram combining CT imaging with clinical features for prediction of lymph node metastasis in Stage I-IIIB non-small cell lung cancer. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022;56(1):155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakanishi K, Nakamura S, Sugiyama T, et al. Diagnostic utility of metabolic parameters on FDG PET/CT for lymph node metastasis in patients with cN2 non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liao X, Liu M, Li S, et al. The value on suv-derived parameters assessed on (18)F-FDG PET/CT for predicting mediastinal lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Med Imaging. 2023;23(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]