ABSTRACT

Background

Pediatric kidney transplant recipients experience creeping creatinine, which is a slow increase in serum creatinine over time. Distinguishing between normal growth‐related changes and possible allograft dysfunction becomes challenging when interpreting the increase in serum creatinine. We hypothesized that changes in BSA‐indexed measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) or creatinine‐estimated GFR (eGFR) might not be a true reflection of the renal function post‐transplant and that for longitudinal follow‐up a stable absolute mGFR is better.

Methods

In total, 115 pediatric kidney transplant recipients transplanted between 2000 and 2021, with 319 measured GFR values (each subject had at least 2 values) were enrolled in this retrospective study. We analyzed after stratifying based on the height and BSA changes (< 5% change, 5%–14.9% change, and > 15% change in height and BSA) between measured GFR tests. The agreement between absolute mGFR and both BSA‐indexed mGFR or eGFR was analyzed by Bland and Altman analysis and nonparametric Spearman's rank order correlation analysis.

Results

The bias between absolute mGFR and either BSA‐indexed mGFR or eGFR increased as the % change in height and the BSA increased. Spearman's rank order correlation showed a strong correlation when the BSA and height changes were < 5% and the correlation weakened as the % changes increased.

Conclusions

In children who grew more, the BSA‐indexed mGFR dropped more than the absolute mGFR. We propose that a stable absolute mGFR can be used to infer stable allograft function in the presence of height growth.

Keywords: glomerular filtration rate, growth, pediatrics, renal transplant

This study highlights that in pediatric kidney transplant recipients, absolute measured GFR is a more reliable indicator of stable allograft function than BSA‐indexed GFR or eGFR, especially during periods of significant growth. This approach helps distinguish between normal growth‐related changes and potential graft dysfunction.

Abbreviations

- BSA

Body Surface Area

- eGFR

creatinine‐estimated GFR

- ESKD

End Stage Kidney Disease

- GFR

Glomerular Filtration Rate

- mGFR

measured glomerular filtration rate

1. Introduction

Creeping creatinine is a progressive increase in the serum creatinine level over time following kidney transplantation. It is a prominent characteristic of chronic allograft dysfunction but can have multiple causes. Calcineurin inhibitor toxicity, nephrotoxicity, and advanced donor age are recognized risk factors [1].

Growth retardation is common in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. Growth retardation is greatest in kidney recipients and occurs to a lesser extent in other solid organ recipients [2]. Although kidney transplantation improves most of the metabolic and endocrine disorders that contribute to growth failure in end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD), growth retardation persists post‐transplant and is influenced by the age at transplantation, allograft function, race, and steroid exposure [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. The gender of the recipient, the source of the donor graft, or the number of grafts did not influence the growth patterns post‐kidney transplant [8].

Corticosteroids inhibit growth by abnormal spontaneous GH secretion and decreased local production of IGF‐I [9]. Children with ESKD have disproportionate stunting, and post‐transplant there is an increase in leg length resulting in restoring body proportions [10]. These patterns of growth will lead to an increase in serum creatinine as it co‐varies closely with the skeletal muscle mass.

Creatinine is produced in muscle by the non‐enzymatic conversion of creatinine and phosphocreatinine. The amount of creatinine produced is proportional to muscle mass. Skeletal muscle mass gain is associated with height gain in children and adolescents [11]. Therefore, creeping serum creatinine in pediatric transplant recipients can be due to either an increase in muscle mass and growth or a chronic decline in allograft function. Serial kidney transplant biopsies to differentiate between these two causes would be invasive and expensive.

True glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is the amount of blood filtered by the kidneys each minute. It is a physiological property that cannot be measured directly in humans. Instead, it is estimated using two methods:

Measured GFR (mGFR) is calculated from the clearance of exogenous filtration markers, which are substances that are filtered by the kidneys but are not produced by the body.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) is calculated from the serum concentrations of endogenous filtration markers like creatinine and cystatin C.

In pediatric kidney transplant recipients, gradual elevation of the creatinine due to linear growth and increased muscle mass is not representative of a true reduction in GFR.

Since the essential function of kidneys is to clear the metabolic waste, it is important to index GFR for a proportion of body size to facilitate comparison between individuals. McIntosh et al. proposed indexing kidney function to body surface area (BSA) and proposed 1.73 m2 as the indexing factor. The choice of BSA for indexing GFR was based on the assertion that it is the nearest available parallel to functional kidney mass [12]. This assertion poses significant clinical challenges and whether the value of 1.73 m2 reflects a normal BSA, is arguable [13, 14]. Poor correlation between BSA and absolute GFR also makes BSA as a normalizing index prone to errors [15].

All recognized BSA formulae are based on body variables, such as height and weight [16]. Accelerated linear growth and weight gain post renal transplant both increase the BSA and thereby underestimation of the GFR. In the absence of acute rejection episodes and without a biopsy, judging in a less invasive way whether this decline in GFR is due to linear body growth or progressive chronic allograft dysfunction is impossible.

In measured glomerular filtration rate assays, GFR can be expressed as an absolute value (mL/min) or a BSA‐indexed value (mL/min per 1.73 m2). Estimated GFR (e‐GFR) is nearly always expressed as a BSA‐indexed value (mL/min per 1.73 m2).

In the present study, we hypothesized that children who had rising serum creatinine predominantly due to linear growth and muscle mass would show a minimal change in absolute mGFR, with greater change in BSA‐indexed mGFR and creatinine‐based eGFR.

2. Methods

Between January 2000 and December 2021, 115 patients under the age of 18 years received renal transplantation at St. Louis Children's Hospital are included in the study. According to our institution's protocol, children post‐transplant undergo GFR measurement 1 year after the procedure. If their GFR is greater than 40 mL/min per 1.73 m2, the measurement is repeated every 2 years. However, if their GFR is less than 40 mL/min per 1.73 m2, the measurement is conducted annually.

To analyze the effect of linear growth on measured GFR and estimated GFR, the analysis presented here was restricted to those 115 children who had more than one measured GFR. We compared 319 measurements of absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed GFR and absolute measured GFR to estimated GFR obtained during I‐125 Iothalamate‐measured GFR studies. At the time of the patient's measured GFR study, additional data collected on the same day included serum creatinine and anthropometrics. The institutional review board of Washington University in St. Louis approved this study (IRB ID # 201706113).

2.1. Measured Glomerular Filtration Rate

The reference measured GFR in the present study was determined by the I‐125 Iothalamate clearance method. The reference measured GFR was calculated by a radiologist from the plasma activity of I‐125 Iothalamate from the time activity curve at multiple points over 4 h after a single intravenous bolus of I‐125 Iothalamate. The measured GFR was reported as both absolute GFR (mL/min) and BSA‐indexed GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2). Body surface area (BSA) was calculated from the DuBois & DuBois formula with height in centimeters, as BSA (m2) = 0.007184 × height (cm)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425 [17]. In general, length contributes more towards BSA than weight in this formula.

2.2. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

We compared 319 measured GFR values to estimated GFR results calculated from CKiDSCr equation 0.413 × height (cm)/Scr [18]. This equation was previously validated in multiple studies in estimating GFR in pediatric kidney transplant recipients [19, 20, 21].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the entire cohort are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. We conducted analyses after stratifying based on the BSA changes and height changes (< 5% change, 5.0%–14.9% change, and ≥ 15% change in BSA or height) between measured GFR tests.

Bland–Altman analyses were conducted to determine the agreement between the average difference of Absolute measured GFR minus BSA‐indexed GFR (plotted on the y‐axis) and the average of absolute GFR and BSA‐indexed GFR ((absolute‐GFR + BSA‐indexed GFR)/2) plotted on the x‐axis, where limits of agreement are calculated as the mean difference ± 2 standard deviations (SD). A similar statistical analysis was used to determine the agreement between absolute measured GFR and estimated GFR.

We also performed correlation analysis with nonparametric Spearman's rank order correlation coefficient of absolute measured GFR and BSA‐indexed values stratified by BSA and height change.

3. Results

The baseline characteristics of the study participants included for analysis are shown in Table 1. The median age at the time of transplant was 11.2 (IQR 6.1–15.7) years, with a male: female ratio of 64:51. The study population consisted predominantly of first kidney transplant recipients 95% and deceased donor grafts 65.2%. The median serum creatinine was 1.0 mg/dL (IQR 0.7–1.4 mg/dL). Between January 2000 and December 2021, these pediatric kidney transplant recipients had 319 mGFR measurements with a corresponding serum creatinine and height on the same day. The median absolute mGFR was 51 mL/min (IQR 35–70), the median BSA‐indexed mGFR was 68 mL/min/1.732 m2 (IQR 51–84 mL/min/1.732m2), and the eGFR was 64 mL/min/1.732 m2 (IQR 49–82). The median BSA in this study was 1.42 m2 (IQR 1.05–1.65), less than the standard BSA of 1.73 m2.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics at the time of the transplant.

| Variable | Categories | N (%) | Median (25–75 IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 115 | — | |

| Gender | Male | 64 (55.7) | |

| Female | 51 (44.3) | ||

| Age (years) at the time of transplant | < 5 Years | 23 (20) | |

| 5.1–10 Years | 25 (21.7) | ||

| 10.1–15 Years | 28 (24.4) | ||

| > 15 years | 39 (33.9) | ||

| Age Median | — | — | 11.2 (6.1–15.7) |

| Race | White/Caucasian | 89 (77.4) | |

| Black/African American | 23 (20) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.6) | ||

| BSA kg/m2 | — | — | 1.42m2 (1.05–1.65) |

| Donor type | Living | 40 (34.8) | |

| Deceased | 75 (65.2) | ||

| Kidney transplant | First allograft | 110 (95.7) | |

| Second allograft | 4 (3.4) | ||

| Third allograft | 1 (0.9) | ||

| Primary kidney disease | Glomerular disease | 68 (59.2) | |

| Non‐glomerular disease | 40 (34.8) | ||

| Unknown | 7 (6) | ||

| Median absolute measured GFR | — | — | 51 mL/min (IQR 35–70) |

| Median BSA‐indexed measured GFR | — | — | 68 mL/min/1.732 m2 (51–84) |

| Median CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR | — | — | 64 mL/min/1.732 m2 (49–82) |

3.1. Changes in Height: Impact of Changes in Height by Comparing Absolute Measured GFR to BSA‐Indexed GFR and Absolute Measured GFR to Estimated GFR

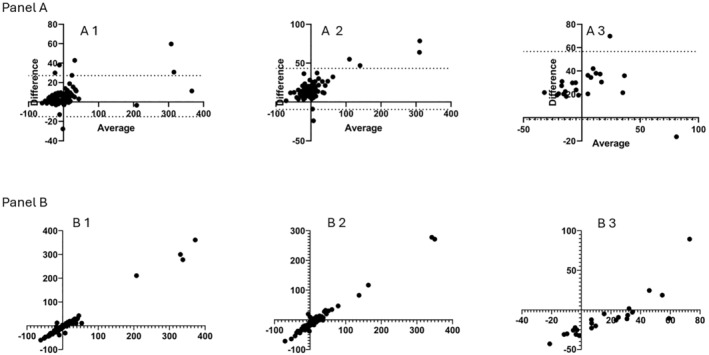

The bias introduced in the GFR when indexing for BSA, calculated with the Bland–Altman method comparison, was small (6.0 mL/min; 95% confidence interval (−15–27 mL/min)) when there is < 5% change in length between subsequent measures. The bias between absolute and BSA‐indexed mGFR increased to 17 mL/min; 95% confidence interval (−9.7–43 mL/min) when there is a 5.0%–14.9% change in length. The bias further increased (28 mL/min; 95% confidence interval (−1.6–57 mL/min)) when there is a > 15% increase in length (Figure 1 Panel A and Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Panel (A) Bland–Altman plots of absolute measured GFR and BSA‐indexed measured GFR when the height difference between subsequent GFR measurements is A1 < 5%, A2 5%–14.9%, A3 > 15%. The mean bias and the standard deviation (SD) bias are represented below the graphs. Panel (B) correlation analysis between absolute measured GFR and BSA‐indexed measured GFR when the height difference between subsequent GFR measurements is B1 < 5%, B2 5%–14.9%, B3 > 15%.

TABLE 2.

Bland–Altman agreement analysis and Spearman correlation analysis: Impact of changes in height by comparing absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR and absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation based on estimated GFR.

| Bias | SD | 95% limits of agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland‐Altman agreement analysis: absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR | |||

| < 5% Height change | 6.0 | 11 | −15–27 |

| 5%–14.9% Height change | 17.0 | 14 | −9.7–43 |

| > 15% Height change | 28.0 | 15 | −1.6–57 |

| r | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman Correlation analysis absolute: absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR | ||

| < 5% Height change | 0.94 | 0.91–0.96 |

| 5%–14.9% Height change | 0.92 | 0.88–0.95 |

| > 15% Height change | 0.91 | 0.79–0.96 |

| Bias | SD | 95% limits of agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland–Altman agreement analysis: absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR | |||

| < 5% Height change | 6.6 | 32 | −56–69 |

| 5%–14.9% Height Change | 12 | 34 | −53–78 |

| > 15% Height change | 26 | 27 | −26–78 |

| r | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman correlation analysis absolute: absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR | ||

| < 5% Height change | 0.57 | 0.40–0.70 |

| 5%–14.9% Height change | 0.52 | 0.34–0.66 |

| > 15% Height change | 0.28 | −0.16–0.63 |

There was a strong positive correlation between the absolute mGFR and BSA‐indexed mGFR when the change in length is < 5% (r = 0.94) in the consecutive measurements when compared to the other two groups (r = 0.92 for 5.0%–14.9% increase in length r = 0.91 for > 15% increase in length) (Figure 1 Panel B and Table 2).

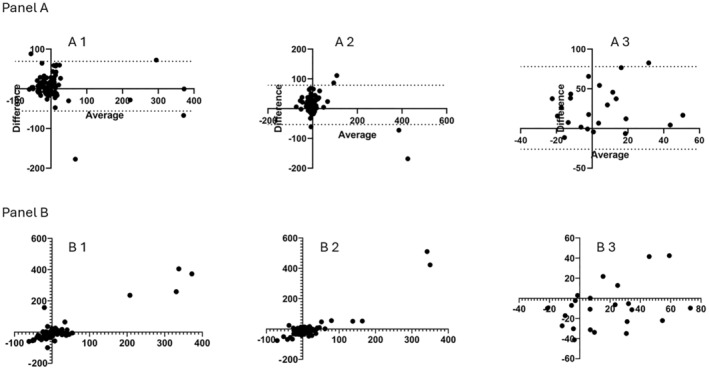

The bias introduced in the GFR for eGFR was 6.6 mL/min (95% confidence interval (−5.6–27 mL/min) when there is < 5% change in length between subsequent measures. The bias between absolute mGFR and estimated GFR increased to 12 mL/min; 95% confidence interval (−53–78 mL/min)) when there is a 5.0%–14.9% change in length. The bias further increased (26 mL/min; 95% confidence interval (−26–78 mL/min)) when there was a > 15% increase in length (Figure 2 Panel A and Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Panel (A) Bland–Altman plots of absolute measured GFR and CKiDSCr equation based on estimated GFR when the height difference between subsequent GFR measurements is A1 < 5%, A2 5%–14.9%, A3 > 15%. The mean bias and the standard deviation (SD) bias are represented below the graphs. Panel (B) correlation analysis between absolute measured GFR and CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR when the height difference between subsequent GFR measurements is B1 < 5%, B2 5%–14.9%, B3 > 15%.

The correlation between absolute mGFR and estimated GFR was not as robust as the correlation between absolute GFR and BSA‐indexed GFR. When the change in length is less than 5% in consecutive measurements, a positive correlation of only 0.57 existed between the absolute GFR and the estimated GFR, in comparison with the other two groups, dropping to 0.52 and 0.28 in the groups with bigger % BSA change (Figure 2 Panel B and Table 2).

3.2. Changes in Body Surface Area: Impact of Changes in Body Surface Area by Comparing Absolute mGFR to BSA‐Indexed mGFR and Absolute mGFR to eGFR

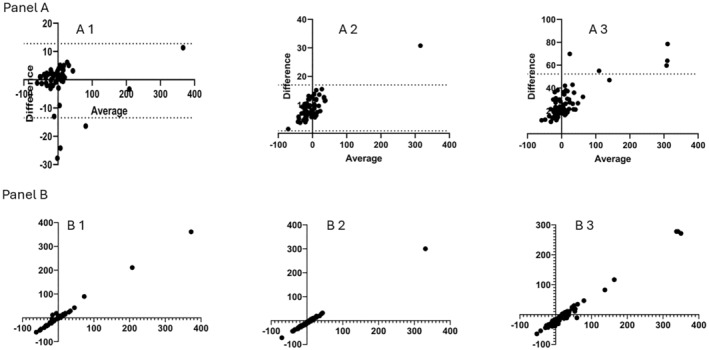

Results followed the length trend when using BSA as the stratifying variable. Utilizing the Bland–Altman method for comparison, the introduction of bias in GFR due to BSA indexing was found to be minimal (−0.35 mL/min; SD 6.7) in cases where there was less than a 5% change in BSA between subsequent measurements. However, the bias between absolute m and BSA‐indexed mGFR increased to 8.9 mL/min (SD 4.1) when the change in BSA ranged from 5% to 14.9%. Furthermore, the bias further escalated to 26 mL/min (SD 13) when there was a BSA increase of over 15% (Figure 3 Panel A and Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Panel (A) Bland–Altman plots of absolute measured GFR and BSA‐indexed measured GFR when the body surface area difference between subsequent GFR measurements is A1 < 5%, A2 5%–14.9%, A3 > 15%. The mean bias and the standard deviation (SD) bias are represented below the graphs. Panel (B) correlation analysis between absolute measured GFR and BSA‐indexed measured GFR when the body surface area difference between subsequent GFR measurements is B1 < 5%, B2 5%–14.9%, B3 > 15%.

TABLE 3.

Bland–Altman agreement analysis and Spearman correlation analysis: Impact of changes in body surface area by comparing absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR and absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR.

| Bias | SD | 95% limits of Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland and Altman agreement analysis absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR | |||

| < 5% BSA change | −0.35 | 6.7 | −13–13 |

| 5%–14.9% BSA change | 8.9 | 4.1 | 0.89–17 |

| > 15% BSA change | 26 | 13 | 0.11–52 |

| r | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman correlation analysis absolute measured GFR to BSA‐indexed measured GFR | ||

| < 5% BSA change | 0.95 | 0.92–0.97 |

| 5%–14.9% BSA change | 0.94 | 0.91–0.96 |

| > 15% BSA change | 0.92 | 0.90–0.95 |

| Bias | SD | 95% limits of agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland and Altman agreement analysis absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR | |||

| < 5% BSA change | 5.8 | 22 | −36–48 |

| 5%–14.9% BSA change | 6.9 | 33 | −58–71 |

| > 15% BSA change | 19 | 37 | −53–92 |

| r | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman correlation analysis absolute measured GFR to CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR | ||

| < 5% BSA change | 0.70 | 0.53–0.82 |

| 5%–14.9% BSA change | 0.41 | 0.18–0.60 |

| > 15% BSA change | 0.30 | 0.2–0.53 |

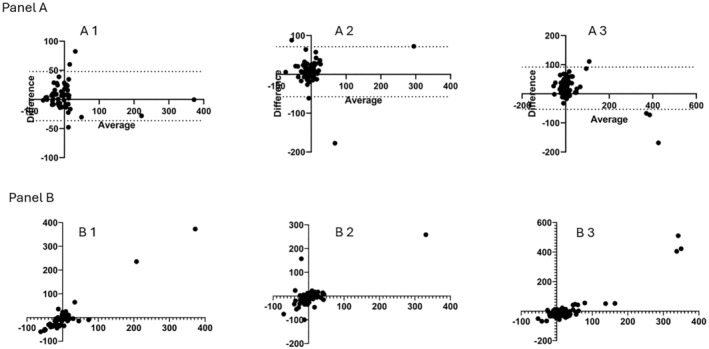

The estimation of GFR by CKiDSCr equation introduces a bias of 5.8 mL/min (SD 22) when there is less than a 5% change in BSA between subsequent measurements. The bias between absolute and estimated GFR increases to 6.9 mL/min (SD 33) when there is a 5.0%–14.9% change in BSA. Moreover, the bias further increases to 19 mL/min; (SD 37) when there is a BSA increase of more than 15% (Figure 4 Panel A).

FIGURE 4.

Panel (A) Bland–Altman plots of absolute measured GFR and CKiDSCr equation based on estimated GFR when the body surface area difference between subsequent GFR measurements is A1 < 5%, A2 5%–14.9%, A3 > 15%. The mean bias and the standard deviation (SD) bias are represented below the graphs. Panel (B) correlation analysis between absolute measured GFR and CKiDSCr equation‐based estimated GFR when the body surface area difference between subsequent GFR measurements is B1 < 5%, B2 5%–14.9%, B3 > 15%.

Strong Spearman correlations were seen between the absolute mGFR and BSA‐indexed mGFR, > 0.90 in each of the three groups of BSA change. However, the correlations were much lower when comparing absolute mGFR to eGFR, ranging from 0.70 down to 0.30 in the 3%BSA change groups (Figure 4 Panel B and Table 3). These results were parallel to our results with length change, suggesting that height change is more impactful than weight change.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study using the I‐125 Iothalamate clearance method as a reference method in pediatric kidney transplant recipients to differentiate progressive graft dysfunction from the apparent decrease in the glomerular filtration rate due to an increase in body surface area. We are not aware of any studies that have compared absolute measured GFR with BSA‐indexed GFR (or any other measure of body size) and estimated GFR in serially allograft function in pediatric renal transplant recipients.

Serum creatinine is the most widely available and frequently used marker for allograft function. The primary determinant for creatinine production is skeletal muscle mass where the final metabolic catabolite is creatinine [22]. In contrast to adult patients, the choice of the body variable for indexing GFR is crucial in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. In children, the evolving shape of their bodies and the inherent property that smaller objects have proportionately larger surface areas present challenges when using BSA as an indexing factor.

Post‐transplant increase in body weight and muscle mass in particular—changes over time and leads to changes in serum creatinine. The alteration in body proportion, weight, and height gain may lead to an underestimation of BSA‐indexed GFR and estimated GFR without actual changes in absolute measured GFR.

The study reaffirms the existing understanding that there is a tendency to underestimate GFR as BSA increases when using BSA‐indexed GFR values [23]. In our study, the bias of the GFR introduced when indexing for BSA was small (6.0 mL/min) when there was < 5% change in length, the bias increased to (17 mL/min) when there was a 5%–14.9% change in length and the bias further increased (28 mL/min) when there is a > 15% increase in length between subsequent measurements of length. The bias of the GFR introduced when indexing for BSA increases with the amount of change in length between subsequent measures. This suggests that the use of BSA as an indexing factor may be less accurate in patients with significant changes in length.

The introduction of bias in estimating GFR was minimal (6.6 mL/min) when there was less than a 5% change in length between subsequent measures. However, this bias increased to 12 mL/min when there was a 5%–14.9% change in length and further escalated to 26 mL/min when the change in length exceeded 15%. The observed increase in bias can be attributed to the rise in creatinine levels that commonly occur post‐transplant, mainly due to increased muscle mass. These findings underscore the potential for reduced accuracy in estimating GFR in patients experiencing significant changes in length, particularly after transplantation.

It is clinically important to differentiate a true decline in graft function from an apparent decrease due to an increase in BSA, as GFR values are used to adjust the level of immune suppression and it also defines long‐term graft survival. This differentiation is also very important to avoid unnecessary biopsies. Several previous studies noted that BSA‐indexed GFR can be inaccurate in those with extreme body sizes and other studies have documented that obese patients have higher absolute GFR values than lean patients [24, 25, 26]. Previous studies questioned indexing GFR to BSA Indexing GFR in longitudinal studies when the measured GFR of the same patient is followed up [27, 28].

Bohle and coworkers showed detrimental effects of tubulointerstitial changes even in inflammatory and non‐inflammatory glomerular diseases, on renal excretory function [29]. Measured GFR strongly correlated with structural tubulointerstitial changes. BSA per se does not affect tubulointerstitial integrity, so indexing GFR to body surface area might not reflect the true changes in GFR.

This retrospective study demonstrates clinically significant differences between BSA‐indexed GFR, serum creatinine‐based estimated GFR, and absolute measured GFR. The results indicate a bias in both BSA‐indexed GFR and estimated GFR when there is a significant increase in BSA and length, despite the absolute measured GFR remaining relatively stable. These findings highlight the importance of considering these factors when assessing renal function accurately in post‐kidney transplant pediatric patients.

This study has several strengths; there is a distribution of patients across the pediatric age groups followed for several years with directly measured GFR assessed at several time points. Our study also has limitations. We are unable to determine whether weight changes reflect changes in fat mass, fat‐free mass, or total body water, and no information regarding protein intake. We have not attempted to correlate mGFR values with tissue estimates of chronic scarring. Another limitation of our study is that we did not evaluate the results based on age groups. The children in our study transitioned through the age group classifications over the course of our longitudinal follow‐up, which spanned several years. Additionally, we had a limited number of adolescents with more than 15% growth and very few younger children with less than 5% growth. As a result, any potential differences between age groups were not a primary focus of our analysis.

5. Conclusions

Even though indexing glomerular filtration rate to body surface area allows direct comparison among the patients and defines normal values we propose that in longitudinal follow‐up (when the values are compared within the same patient), it is important to use the absolute GFR to avoid bias with the indexed GFR and estimated GFR. A stable absolute mGFR can be used to infer stable allograft function such that decreased BSA‐indexed GFR is from height or BSA increase does not lead to clinical decisions.

Author Contributions

Raja S. Dandamudi: designed the study, collected data, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Neil Vyas: collected data and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. Stanley P. Hmiel: designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. Vikas R. Dharnidharka: designed the study, interpreted the data, and reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

The institutional review board of Washington University in St. Louis approved this study (IRB ID # 201706113).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

While this manuscript is part of the Festschrift to honor Dr. Richard Fine, we also wish to acknowledge and honor our late colleague Dr. S. Paul Hmiel, a co‐author of this manuscript. He was the original proponent of the concept of using the change in absolute mGFR to differentiate between height growth versus progressive allograft dysfunction when the serum creatinine was creeping up. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting 2020 and ASN Kidney week 2020.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Paul L. C., “Chronic Allograft Nephropathy: An Update,” Kidney International 56, no. 3 (1999): 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fine R. N., “Growth Following Solid‐Organ Transplantation,” Pediatric Transplantation 6, no. 1 (2002): 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tejani A., Fine R., Alexander S., Harmon W., and Stablein D., “Factors Predictive of Sustained Growth in Children After Renal Transplantation. The North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study,” Journal of Pediatrics 122, no. 3 (1993): 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fine R. N., “Growth Following Solid Organ Transplantation in Childhood,” Clinics 69, no. Suppl 1 (2014): 3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fine R. N., “Commentary on Long‐Term Growth Following Renal Transplantation in Children,” Transplantation 104, no. 1 (2020): 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fine R. N. and Tejani A., “Growth Following Renal Transplantation in Children,” Transplantation Proceedings 30, no. 5 (1998): 1959–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harambat J. and Cochat P., “Growth After Renal Transplantation,” Pediatric Nephrology 24, no. 7 (2009): 1297–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fine R. N., Martz K., and Stablein D., “What Have 20 Years of Data From the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study Taught Us About Growth Following Renal Transplantation in Infants, Children, and Adolescents With End‐Stage Renal Disease?,” Pediatric Nephrology 25, no. 4 (2010): 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fine R. N., “Corticosteroids and Growth,” Kidney International. Supplement 43 (1993): S59–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Franke D., Thomas L., Steffens R., et al., “Patterns of Growth After Kidney Transplantation Among Children With ESRD,” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 10, no. 1 (2015): 127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu D., Shi L., Xu Q., et al., “The Different Effects of Skeletal Muscle and Fat Mass on Height Increment in Children and Adolescents Aged 6–11 Years: A Cohort Study From China,” Frontiers in Endocrinology 13 (2022): 915490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McIntosh J. F., Moller E., and Van Slyke D. D., “Studies of Urea Excretion III: The Influence of Body Size on Urea Output,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 6, no. 3 (1928): 467–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heaf J. G., “The Origin of the 1 × 73‐m2 Body Surface Area Normalization: Problems and Implications,” Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging 27, no. 3 (2007): 135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geddes C. C., Woo Y. M., and Brady S., “Glomerular Filtration Rate What Is the Rationale and Justification of Normalizing GFR for Body Surface Area?,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 23, no. 1 (2008): 4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dooley M. J. and Poole S. G., “Poor Correlation Between Body Surface Area and Glomerular Filtration Rate,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 46, no. 6 (2000): 523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Redlarski G., Palkowski A., and Krawczuk M., “Body Surface Area Formulae: An Alarming Ambiguity,” Scientific Reports 6 (2016): 27966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Du Bois D. and Du Bois E. F., “A Formula to Estimate the Approximate Surface Area if Height and Weight Be Known. 1916,” Nutrition 5, no. 5 (1989): 303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz G. J., Munoz A., Schneider M. F., et al., “New Equations to Estimate GFR in Children With CKD,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 20, no. 3 (2009): 629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Souza V., Cochat P., Rabilloud M., et al., “Accuracy of Different Equations in Estimating GFR in Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients,” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 10, no. 3 (2015): 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dandamudi R., Vyas N., Hmiel S. P., and Dharnidharka V. R., “Performance of the Various Serum Creatinine‐Based GFR Estimating Equations in Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients, Stratified by Age and CKD Staging,” Pediatric Nephrology 36, no. 10 (2021): 3221–3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alkandari O., Hebert D., Langlois V., Robinson L. A., and Parekh R. S., “Validation of Serum Creatinine‐Based Formulae in Pediatric Renal Transplant Recipients,” Pediatric Research 82, no. 6 (2017): 1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wyss M. and Kaddurah‐Daouk R., “Creatine and Creatinine Metabolism,” Physiological Reviews 80, no. 3 (2000): 1107–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Redal‐Baigorri B., Rasmussen K., and Heaf J. G., “The Use of Absolute Values Improves Performance of Estimation Formulae: A Retrospective Cross Sectional Study,” BMC Nephrology 14 (2013): 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delanaye P., Radermecker R. P., Rorive M., Depas G., and Krzesinski J. M., “Indexing Glomerular Filtration Rate for Body Surface Area in Obese Patients Is Misleading: Concept and Example,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 20, no. 10 (2005): 2024–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chagnac A., Weinstein T., Korzets A., Ramadan E., Hirsch J., and Gafter U., “Glomerular Hemodynamics in Severe Obesity,” American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 278, no. 5 (2000): F817–F822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levey A. S. and Kramer H., “Obesity, Glomerular Hyperfiltration, and the Surface Area Correction,” American Journal of Kidney Diseases 56, no. 2 (2010): 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Delanaye P. and Krzesinski J. M., “Indexing of Renal Function Parameters by Body Surface Area: Intelligence or Folly?,” Nephron. Clinical Practice 119, no. 4 (2011): c289–c292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Delanaye P., Mariat C., Cavalier E., and Krzesinski J. M., “Errors Induced by Indexing Glomerular Filtration Rate for Body Surface Area: Reductio Ad Absurdum,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 24, no. 12 (2009): 3593–3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bohle A., Mackensen‐Haen S., and von Gise H., “Significance of Tubulointerstitial Changes in the Renal Cortex for the Excretory Function and Concentration Ability of the Kidney: A Morphometric Contribution,” American Journal of Nephrology 7, no. 6 (1987): 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.