This subgroup analysis of data from a cross-sectional online survey evaluated the prevalence and impact of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and related treatment patterns among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in Canada. Moderate to severe VMS were reported by 14.7% of postmenopausal women and were associated with impairments in quality of life, work productivity, daily activities, and sleep in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Key Words: Hot flashes, Postmenopause, Productivity, Quality of life, Sleep, Work

Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the impact of VMS and related treatment patterns among perimenopausal and postmenopausal Canadian women.

Methods

A subgroup analysis of data from a cross-sectional online survey of women aged 40-65 years conducted November 4, 2021, through January 17, 2022, evaluated the prevalence of moderate/severe VMS among postmenopausal Canadian women. The analysis also assessed survey responses from perimenopausal and postmenopausal Canadian women with moderate/severe VMS who completed the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sleep Disturbances-Short Form 8b and answered questions about treatment patterns and attitudes toward treatments.

Results

Of 2,456 Canadian postmenopausal women, 360 (14.7%; primary analysis) reported moderate/severe VMS in the previous month. Perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with moderate/severe VMS (n = 400; secondary analysis) reported negative impact on overall quality of life (mean total Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire score: 4.3/8). VMS impaired overall work and daily activities by 30.2% and 35.7%, respectively. Overall mean (SD) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sleep Disturbance-Short Form 8b score (scale 8-40) was 28.5 (6.9), confirming sleep disturbances in this population. The majority of women (88% of the total cohort) sought advice, but about half were never treated. Most women had positive or neutral attitudes toward menopause.

Conclusions

In a survey conducted in Canada, moderate/severe VMS were reported by 14.7% of postmenopausal women and were associated with impairment in quality of life, work productivity, daily activities, and sleep in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

The prevalence, severity, and level of bother of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) due to menopause vary around the world.1,2 Prevalence of VMS is estimated to range from 41% to 77% in North America.1 For many of these women, VMS (including hot flashes and/or night sweats) decrease quality of life, interfere with work productivity and daily activities, and disrupt sleep.3-6 The median age of natural menopause in Canada is 51 years.7 In 2018, approximately 4.4 million of 6.3 million Canadian women aged 40-64 years were employed,8 suggesting a large population of employed women in perimenopause/postmenopause are potentially affected by VMS.

Most women are not currently treating their VMS,9 maybe because of a lack of knowledge about treatment options, the belief that menopause is a natural process of aging, or concerns about the side effects and safety of existing pharmaceutical treatments.10-12 Both The Menopause Society and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada in collaboration with the Canadian Menopause Society guidelines recommend hormone therapy (HT) with estrogen alone (for women who had a hysterectomy) or combined with a progestogen (for women with a uterus) as the most effective option for relief of VMS in women who are younger than 60 years or less than 10 years after their final menstrual period and do not have HT contraindications.13-15 Nonhormone therapies, including antidepressants (ie, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), gabapentinoids, oxybutynin, clonidine, and neurokinin 3 inhibitors, are recommended when HT is contraindicated or the patient prefers other treatment options; however, many of these treatments may not be as effective as HT.11,14 The benefits should be balanced with the potential risks associated with long-term use of HT (eg, breast cancer, stroke, venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease) and HT should be individualized based on symptoms, risk factors, and patient preferences.13-15 Although use of supplements, such as natural health products, is not recommended because of limited evidence for effectiveness, many women seeking treatment prefer more natural approaches to their VMS.14 Fezolinetant is an oral, nonhormone, NK3 receptor antagonist treatment option for moderate to severe VMS and is approved in many countries, including the United States, Europe, and Australia, and in Europe, at a dose of 45 mg once daily.16-20

Several secondary analyses have included data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), which examines the effects of menopause on Canadian women.7,21,22 HT use for VMS was generally lower among women who were current smokers, obese, currently employed, and of a non-White ethnic background.22 However, data on the prevalence, burden, and treatment of VMS among Canadian women have been limited.

The multinational Women with Vasomotor Symptoms Associated with Menopause (WARM) study used a cross-sectional, online survey that investigated the prevalence and impact of moderate to severe VMS among women aged 40-65 years from Brazil, Canada, Mexico, or four Nordic European countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden). The WARM international study found that 16% of postmenopausal women experienced moderate to severe VMS and that VMS negatively affected quality of life, work, and sleep in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.23 We report a subgroup analysis of the WARM study evaluating the prevalence and impact of moderate to severe VMS, treatment patterns, and attitudes toward treatment in Canadian women aged 40-65 years.

METHODS

Study design

Between November 4, 2021, and January 17, 2022, we conducted a cross-sectional, online survey with 49 fixed-order, adaptive questions. Three validated, standardized questionnaires were included: the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQoL), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) Specific Health Problem, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Sleep Disturbance-Short Form (SF) 8b. Additional survey questions asked about sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, smoking status, healthcare providers (HCP) consulted about VMS or reasons for not seeking medical advice, sources of information about VMS, and VMS treatment use patterns and perspectives. The survey was developed and conducted by IQVIA (London, United Kingdom), and the data were analyzed by IQVIA in collaboration with Astellas Pharma (Addlestone, United Kingdom). Most of the questions were informed by findings from a previous survey designed from expert discussions.2 Primary results from the WARM international study have been published.23

Analysis population

Dynata (Plano, TX) recruited a convenience sample of women aged 40-65 years from a national panel in Canada via direct email that included a link to the closed survey. Websites, social media, and email corporate brand loyalty lists were used for recruiting purposes. Participation was compensated with rewards points that could be exchanged for cash or prizes. The Canadian panel was representative of the population's demographics that included residential setting (ie, urban vs rural).

The primary analysis populations included women aged 40-65 years in postmenopause (defined as at least 12 consecutive months without a menstrual period) who answered the screening questions. The secondary analysis population included women aged 40-65 years in perimenopause or postmenopause with ≥1 hot flash per day in the past month, most of which were moderate or severe. Perimenopause was defined as changes in menstrual periods or frequency of periods with fewer than 12 consecutive months without a period. Women were excluded if they had never menstruated or were menstruating regularly, were being treated for breast cancer, or had taken antiestrogens, aromatase inhibitors, and/or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists in the past 12 months.

To determine VMS severity, self-rated responses to questions that used United States Food and Drug Administration definitions of severity were assessed.24 VMS severity was categorized as mild (without sweating), moderate (with sweating and able to continue an activity), and severe (with sweating but unable to continue an activity).

Study outcomes

The primary study outcome was overall prevalence of moderate to severe VMS (ie, ≥1 hot flash per day in the past month, mostly moderate or severe) among postmenopausal women during the screening portion of the survey. Five secondary outcomes were assessed in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women meeting the eligibility criteria: MENQoL, WPAI, PROMIS Sleep Disturbance-SF 8b, healthcare resource utilization and treatments for VMS, and opinions regarding VMS treatments.

Respondents were asked whether they had experienced any of 29 menopausal symptoms in the past week and to rate how much they were bothered by these symptoms when responding to the MENQoL.25,26 Symptom ratings were converted to a scale of 1 (not experienced in the past week) or 2 (experienced but not bothered) through 8 (extremely bothered).25,26 A mean score was calculated for each of four domains (vasomotor, physical, psychosocial, and sexual functioning), and the mean of all domain scores served as the total score.25,26

Six questions in the WPAI asked about current employment, absenteeism (hours missed from work), presenteeism (hours at work with impaired productivity), and impairment in daily activities outside of work related to VMS. Levels of impairment were reported on a scale from 0 (no effect on work/activities) to 10 (complete prevention of work/activities),27 and then these ratings were converted to percentages of impairment (scale of 0%-100%).28

Self-perceived sleep quality in the past 7 days was assessed with the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance-SF 8b. Eight items were rated on a scale of 1 to 5,29 and the sum of the 8 scores was calculated for the total score (range: 8-40), with higher scores representing greater sleep impairment.30

The percentage of women who sought advice (from medical specialists or other sources) and treatment for VMS (ie, healthcare resource utilization) was assessed for up to nine survey questions, with some questions asked conditionally based on prior responses. Current or past use of HT and nonhormone prescription and nonprescription treatments for VMS were reported; former users of these treatments could indicate reasons for discontinuing.

Positive and negative statements regarding treatments for VMS were rated based on women's level of agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores of 3-5 indicated moderate agreement, and 6-7 indicated strong agreement. As an exploratory analysis, postmenopausal women with moderate to severe VMS were classified based on eligibility for and interest in HT (Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MENO/B319).

Data collection and quality control

Participants were advised that the survey would take approximately 30 minutes; however, there was no time limit. To ensure that the questions were correctly interpreted, the survey was pilot tested and revised, and underwent linguistic confirmation to ensure correct translation from English to French. Quality control checks identified missing, incomplete, or inconsistent responses. Participants were prevented from skipping questions, except for some on the MENQoL, WPAI, and PROMIS Sleep Disturbance-SF 8b questionnaires, as required by the questionnaire licenses. To maintain anonymity and ensure a single entry per participant, each participant had a unique identification number.

Ethical considerations

Study materials were approved by The Advarra institutional review board (Aurora, Ontario, Canada), and participants provided informed consent to the survey. Responding to the survey questions was voluntary, and participants could discontinue at any time. The sponsor was not disclosed until the survey was completed.

Statistical Methods

Because the expected prevalence of VMS was uncertain, the most conservative assumption of 50% prevalence was used for calculating the sample size. To provide a precision of 4%-5% for estimating moderate to severe VMS prevalence among postmenopausal women, the sample size was selected and adjusted for feasibility based on estimation of the patient population available for that country, as previously reported.23 The final target sample size for Canada was 400, including 10% perimenopausal women and providing an estimated 4.9% precision. The survey was closed, when this target sample was achieved.

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM SPSS Statistics; Chicago, IL) was used to conduct analyses. Demographics, baseline characteristics, and secondary outcome measures were described as summary statistics. No statistical testing was performed; all analyses were descriptive and exploratory to avoid any interpretation beyond the scope of observational purposes. The data are reported as received, without imputation (ie, because it was possible to skip some items on questionnaires, some surveys had incomplete data collection). The number of women who responded to each survey item functioned as the denominator for that item.

RESULTS

Prevalence of VMS among postmenopausal women

Of the 2,456 Canadian women in postmenopause in the primary analysis population, 360 (14.7%) reported moderate to severe VMS (Supplemental Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/MENO/B320)

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

In total, 6,355 Canadian women accessed the survey, of whom 400 completed the screener and main survey. Of the 5,955 women not included in the survey, 3,851 did not pass screening, 1,223 dropped out, and 881 were excluded because the 10% quota for perimenopausal women had been met. The completion rate was 25%.

Of the 400 women, 40 (10%) were in perimenopause and 360 (90%) were in postmenopause, and of these, 262 (65.5%) reported moderate symptoms and 138 (34.5%) reported severe symptoms. Women who reported moderate to severe VMS with ≥1 hot flash per day in the past month were included in the secondary analysis (Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/MENO/B319). The proportion of women was numerically highest in the 56- to 60-year age group (34.0% [136/400]). A mean (SD) of 4.6 (5.4) VMS per day was reported, with a mean (SD) duration of 22.3 (56.9) minutes per episode.

VMS impact on quality of life, work, and sleep among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women

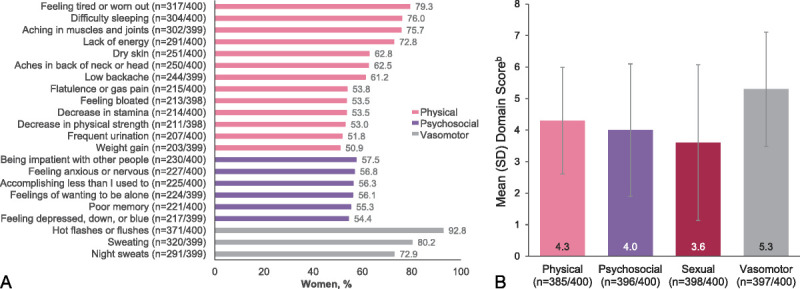

The most frequently reported menopausal symptoms, occurring in ≥50% of women, were hot flashes, sweating, and feeling tired or worn out (Fig. 1A). There was some level of bother (scores >3) based on mean MENQoL scores in all domains (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Menopause symptoms were bothersome across all MENQoL domains. Data are from the 400 women in perimenopause or postmenopause and experiencing moderate to severe VMS. (A) Individual menopause symptoms reported by ≥50% of women,a as reported on the MENQoL. (B) Impact of VMS on physical, psychosocial, sexual, and vasomotor domains, as indicated by mean MENQoL scores. aSexual symptoms are not shown here because no sexual symptoms occurred in ≥50% of women. Physical, psychosocial, and vasomotor symptoms are shown if they occurred in ≥50% of women. bScale is from 1 to 8, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. MENQoL, Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire; SD, standard deviation; VMS vasomotor symptoms.

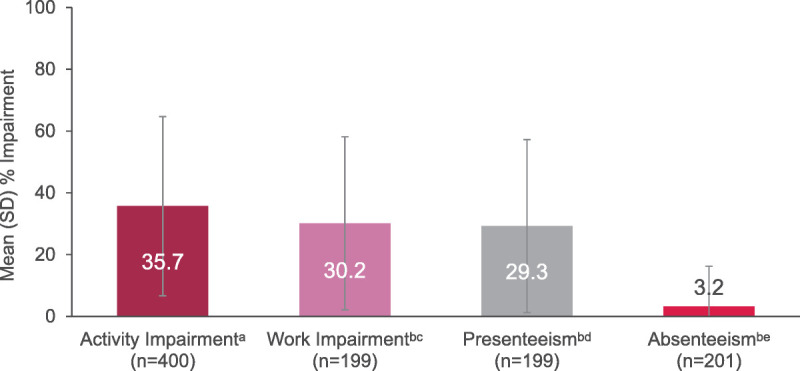

Work and daily activities were impacted by VMS as shown by WPAI scores. Work impairment was primarily driven by the impact of VMS on presenteeism (Fig. 2). A majority of employed women (205/400) who completed the WPAI questionnaire did not miss any work because of VMS (184/205 [89.8%]).

FIG. 2.

WPAI: work productivity and daily activities impaired by VMS. aAssessed in all 400 women in perimenopause or postmenopause and experiencing moderate to severe VMS. bData are out of 205 women who were employed and responded to work-related questions. cWork impairment includes presenteeism and absenteeism. dPresenteeism is the percentage of impairment/ineffectiveness at work. eAbsenteeism is the percentage of missed work due to VMS. SD, standard deviation; VMS, vasomotor symptoms; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire.

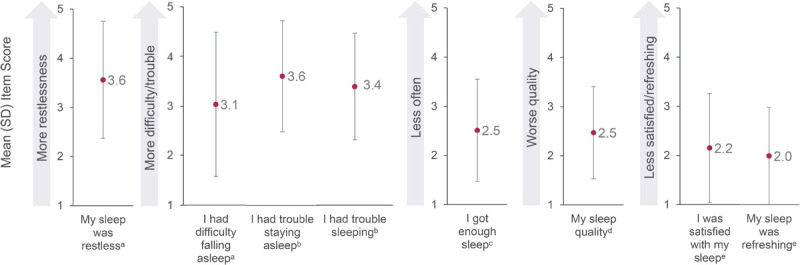

The mean (SD) overall PROMIS Sleep Disturbance SF 8b score was 28.5 (6.9) out of 40. Restless sleep, trouble staying asleep, and trouble sleeping were most highly impacted by VMS (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2, http://links.lww.com/MENO/B319). Among the Canadian women in the WARM study population, 39.5% reported that they were very much refreshed after sleep, 23.5% indicated that they had very much difficulty in falling asleep, and 32% reported often having had trouble staying asleep.

FIG. 3.

Sleep disrupted by VMS in the past 7 days based on the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance-Short Form 8b. Data are from the 400 women in perimenopause or postmenopause and experiencing moderate to severe VMS. aScale: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = very much. bScale: 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always. cScale: 5 = never, 4 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 2 = often, 1 = always. dScale: 5 = very poor, 4 = poor, 3 = fair, 2 = good, 1 = very good. eScale: 5 = not at all, 4 = a little bit, 3 = somewhat, 2 = quite a bit, 1 = very much. PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SD, standard deviation; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

Healthcare resource utilization and VMS treatments among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women

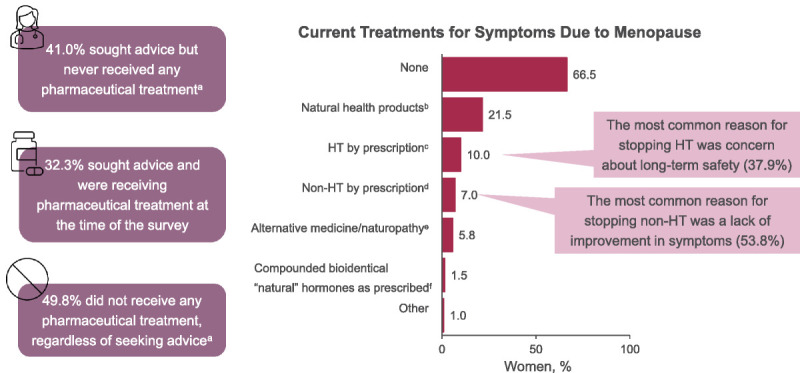

Of the 400 women who responded, over half (239 [59.8%]) had visited an HCP about VMS in the past 12 months, whereas 161 (40.3%) women had not. The most common reason for not seeking HCP advice was not wanting to take any drug to treat hot flashes/night sweats (65/161 [40.4%]). The HCP consulted comprised general practitioners (51.0%), pharmacists (8.8%), gynecologists (7.0%), nurses (3.8%), alternative medicine practitioners (3.5%), endocrinologists (2.5%), gynecologists who specialized in menopause (2.3%), and psychologists (1.5%). A total of 205 women sought advice from nonmedical sources, such as Internet/websites (153 [74.6%]), family and friends (142 [69.3%]), and other women with menopausal symptoms (eg, celebrities, influencers, role models) (48 [23.4%]).

Most women were not currently receiving VMS treatment (266/400 [66.5%]; Figure 4). Those who were previously on or currently using HT reported moderate agreement (mean [SD]: 3.43 [2.21], based on a scale of 1-7, with 7 = I strongly agree) that treatment caused side effects and that treatment improved symptoms, but they worried about long-term risks (mean [SD]: 4.25 [2.07]). Notably, the main reason for women to stop HT was concern over the long-term risks (37.9% [22/58]), and the main reason for stopping nonhormone prescription treatments was that menopause symptoms did not improve (53.8% [7/13]).

FIG. 4.

VMS treatments. Data are from the 400 women in perimenopause or postmenopause and experiencing moderate to severe VMS. aCurrently or in the past. bExamples include vitamins, calcium, and soy. cExamples include estrogen therapy and progestogen therapy. dExamples include SSRIs, SNRIs, antidepressants, or gabapentin for hot flashes. eExamples include herbs, Kampo, Chinese medicine, acupuncture, acupressure, and aromatherapy. fThe term “natural” was included to reflect language exactly as it was presented in the survey. HT, hormone therapy; SNRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

In Supplementary Table 3 (http://links.lww.com/MENO/B319), data categorizing the postmenopausal women based on HT eligibility and interest are shown for the exploratory endpoint. The highest proportions of HT-cautious and HT-averse women were in the 56- to 60-year age group; the highest for HT-stoppers was in the 61- to 65-year age group.

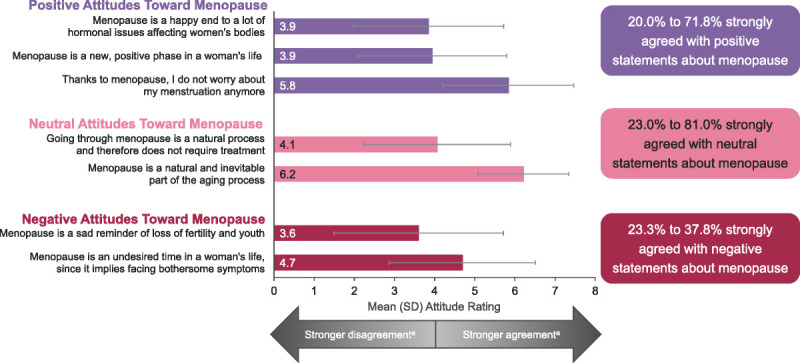

Menopause attitudes among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women

As many as 81% of Canadian women included in the survey strongly agreed with positive or neutral statements about menopause, whereas up to 38% strongly agreed with negative statements (Fig. 5). The most strongly agreed upon positive, neutral, and negative attitudes were, respectively, “Thanks to menopause, I do not worry about my menstruation anymore,” “Menopause is a natural and inevitable part of the aging process,” and “Menopause is an undesired time in a woman's life, since it implies facing bothersome symptoms” (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Attitudes toward menopause. Data are from the 400 women in perimenopause or postmenopause and experiencing moderate to severe VMS. aScale is from 1 to 7, where 1 = I strongly disagree and 7 = I strongly agree. Scores of 3 to 5 were considered moderate agreement; scores ≥6 were considered strong agreement. The X axis is from 0 to 8 to accommodate SD. SD standard deviation; VMS, vasomotor symptoms.

DISCUSSION

This subgroup analysis of Canadian women who took an online, cross-sectional survey in the WARM study highlights the effect of menopause symptoms on quality of life, work performance, daily activities, and sleep. The survey also provides insight into the prevalence of moderate to severe VMS among a sample of postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years in Canada and whether those women sought treatment and advice on managing VMS. The prevalence of moderate to severe VMS in these women was moderate (14.7%). The majority of respondents (66.5%) did not currently receive treatment even though they reported menopausal symptoms on the MENQoL and that they were most bothered by VMS.

The rate of current HT use reported in this survey (10%) is very similar to that reported by Costanian et al (9.5%)22 in an analysis of the Tracking cohort of CLSA; notably, the cohort included women aged 45-85 years, whereas this study included women aged 40-65 years. This suggests that the rate of HT use has not changed much in Canada in recent years and that HCPs could provide more information to women experiencing VMS who might be eligible for HT.

Results from our survey were similar to those highlighted in a report from a recent survey of 1,023 Canadian women aged 40-60 using Leger's online panel conducted by The Menopause Foundation of Canada (MFC).10 A majority of respondents in both surveys reported experiencing more than three menopause-related symptoms, most commonly hot flashes, sleep disturbances, and night sweats.10 Approximately 40% of women in the MFC survey felt that their symptoms were undertreated,10 whereas 31.5% of women in the WARM survey sought advice but did not receive any pharmacologic treatment, and 43.7% did not receive any pharmacologic treatment regardless of seeking advice or care.23 Similarly, the MFC survey found that women preferred their physician as the primary source of advice for perimenopause/menopause followed by the Internet and friends and family.10 A potential opportunity highlighted by the MFC is to expand educational opportunities and awareness about menopause, as many respondents felt unprepared; this is further supported by a study that assessed the quality and readability of the top 24 websites for HT and found that many of these resources are not easily understood by members of the public.10,31

This Canadian subgroup had a prevalence rate of moderate to severe VMS similar to that of Mexico and Nordic Europe (14.7% vs 16.5% and 11.6%, respectively) and less than half the prevalence rate for the Brazilian subgroup (36.2%) found in the WARM study.23 In addition, the Canadian subgroup had a high proportion of women who did not miss any hours from work due to VMS (89.8%). Additional research is needed to understand why these Canadian women did not miss work despite experiencing considerable impairments in work productivity and daily activities.

Women in the Canadian subgroup had the highest mean [SD] score on the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance SF 8b survey compared with the overall mean score across the four countries analyzed (28.5 [6.86] vs 26.6 [6.64] in Brazil, Canada, Denmark, and Mexico combined), experiencing particular difficulty with falling asleep and staying asleep.23 This is consistent with an analysis from the CLSA, which found that 20.4% of postmenopausal women required more than 30 minutes to fall asleep at least 3 times per week (insomnia onset) and that 28.4% woke up and had difficulty falling back to sleep (insomnia maintenance).21 Further, postmenopausal women were more likely to meet criteria for sleep-onset insomnia disorder for about 2 years before and 6 years after menopause onset.21 Thus, finding treatments for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women to improve sleep quality could be beneficial.

Limitations

This cross-sectional study has several weaknesses. The data collection occurred at a single point in time per woman during a 2.5-month window, while published longitudinal analyses have followed a group of women for between 6 and 16 years.32,33 Strict inclusion criteria were used for assessing the prevalence of VMS (≥1 symptom/day in the prior month), which could have limited the study population. Because the study used menstrual period recency and frequency to define perimenopause or postmenopause, women who were not truly in perimenopause or postmenopause but experienced menstrual variations for other reasons (eg, surgery, including hysterectomy without oophorectomy, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, other medications, medical conditions that prevent bleeding) may have been included. Further, this convenience sample of predominantly White women may not represent all Canadian women experiencing menopause because of possible selection bias; therefore, results may not be generalizable.

CONCLUSIONS

In the Canadian subgroup of the WARM study, 14.7% of postmenopausal women reported moderate to severe VMS. Among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in this subgroup, the symptoms of menopause were bothersome across all four domains of the MENQoL (physical, psychosocial, vasomotor, and sexual). Although VMS led to impairment in work productivity, daily activities, and sleep, most women were not currently receiving VMS treatment. The most common reasons for stopping treatment were safety concerns and a lack of efficacy. Overall, these women would benefit from greater access to menopause management and effective therapies to relieve VMS and to reduce the impact of moderate to severe VMS due to menopause.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Kim, of Astellas Pharma Inc., who contributed to study design and data assembly. We also thank the women who participated in the survey.

Footnotes

Funds/support: The WARM study was sponsored by Astellas Pharma (Northbrook, IL, USA). Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Mia DeFino, MS, ELS, CMPP, and Dawn Thiselton, PhD, of Echelon Brand Communications, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Astellas Pharma.

Financial disclosures/conflicts of interest: N.Y.: advisory board participant and/or speaker for BioSyent, Bayer, Astellas, Eisai, Organon, and Duchesnay and recipient of an unrestricted research grant from Bayer. L.T.: employee of Astellas Pharma. L.S.: employee of Astellas Pharma Inc. at the time of the study. C.R.: employee of IQVIA, which developed and conducted the survey and analyzed the data in collaboration with Astellas Pharma. C.B.: advisory board participant and/or speaker for Astellas Pharma, Bayer Canada, BioSyent, Lupin Pharma, and Pfizer Canada and recipient of research grants from Astellas.

Prior presentation: Presented at The Menopause Society (formerly The North American Menopause Society) Annual Meeting, September 27-30, 2023, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Inclusive language: In our report, we use gender-specific language, as reflected in the referenced publications and protocols. However, we recognize that some individuals who experience vasomotor symptoms due to menopause may identify differently from the gender and pronouns used here.

Data sharing statement: Researchers may request access to anonymized participant-level data, survey-level data, and protocols from Astellas-sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing, see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website (www.menopause.org).

Contributor Information

Lora Todorova, Email: lora.todorova@astellas.com.

Ludmila Scrine, Email: ludmila.scrine@hotmail.co.uk.

Carol Rea, Email: carol.rea@iqvia.com.

Céline Bouchard, Email: celinebouchard2@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Makara-Studzinska MT, Krys-Noszczyk KM, Jakiel G. Epidemiology of the symptoms of menopause - an intercontinental review. Prz Menopauzalny 2014;13:203–211. doi: 10.5114/pm.2014.43827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nappi RE Kroll R Siddiqui E, et al. Global cross-sectional survey of women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: prevalence and quality of life burden. Menopause 2021;28:875–882. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumel JE Chedraui P Baron G, et al. A large multinational study of vasomotor symptom prevalence, duration, and impact on quality of life in middle-aged women. Menopause 2011;18:778–785. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318207851d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteley J, Wagner JS, Bushmakin A, Kopenhafer L, Dibonaventura M, Racketa J. Impact of the severity of vasomotor symptoms on health status, resource use, and productivity. Menopause 2013;20:518–524. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31827d38a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.English M Stoykova B Slota C, et al. Qualitative study: burden of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and validation of PROMIS sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment measures for assessment of VMS impact on sleep. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2021;5:37. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00289-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Komm BS. Relationship between changes in vasomotor symptoms and changes in menopause-specific quality of life and sleep parameters. Menopause 2016;23:1060–1066. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costanian C, McCague H, Tamim H. Age at natural menopause and its associated factors in Canada: cross-sectional analyses from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Menopause 2018;25:265–272. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics Canada . Table 14-10-0018-01 Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group, annual, inactive (x 1,000). Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410001801. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://doi.org/10.25318/1410001801-eng

- 9.Ameye L, Antoine C, Paesmans M, de Azambuja E, Rozenberg S. Menopausal hormone therapy use in 17 European countries during the last decade. Maturitas 2014;79:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The silence and the stigma: menopause in Canada. Available at: https://menopausefoundationcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MFC-Report_The-Silence-and-the-Stigma_Menopause-in-Canada_October-2022.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 11.The 2023 Nonhormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society . The 2023 nonhormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2023;30:573–590. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000002200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePree B Houghton K DiBenedetti DB, et al. Practice patterns and perspectives regarding treatment for symptoms of menopause: qualitative interviews with US healthcare providers. Menopause 2023;30:128–135. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.“The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society” Advisory Panel . The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022;29:767–794. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000002028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuksel N Evaniuk D Huang L, et al. Guideline No. 422a: menopause: vasomotor symptoms, prescription therapeutic agents, complementary and alternative medicine, nutrition, and lifestyle. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2021;43:1188–1204.e1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramson BL, Black DR, Christakis MK, Fortier M, Wolfman W. Guideline No. 422e: menopause and cardiovascular disease. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2021;43:1438–1443.e1431. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astellas Pharma US, Inc. VEOZAH® (fezolinetant) [prescribing information]. Northbrook, IL; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astellas Pharma AG. VEOZA™ [summary of product characteristics]. Wallisellen, Switzerland; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astellas Pharma Australia. Australian Product information - VEOZA™ (fezolinetant). Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astellas Pharma Europe B.V. VEOZA [summary of product characteristics]. Leiden, Netherlands; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astellas Pharma Ltd. VEOZA [summary of product characteristics]. Addlestone, United Kingdom; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zolfaghari S Yao C Thompson C, et al. Effects of menopause on sleep quality and sleep disorders: Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Menopause 2020;27:295–304. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costanian C, Edgell H, Ardern CI, Tamim H. Hormone therapy use in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging: a cross-sectional analysis. Menopause 2018;25:46–53. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todorova L Bonassi R Guerrero Carreño FJ, et al. Prevalence and impact of vasomotor symptoms due to menopause among women in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, and Nordic Europe: a cross-sectional survey. Menopause 2023;30:1179–1189. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000002265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry - estrogen and estrogen/progestin drug products to treat vasomotor symptoms and vulvar and vaginal atrophy symptoms: recommendations for clinical evaluation. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/71359/download. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 25.Hilditch JR Lewis J Peter A, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas 1996;24:161–175. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis JE, Hilditch JR, Wong CJ. Further psychometric property development of the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire and development of a modified version, MENQOL-Intervention questionnaire. Maturitas 2005;50:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem V2.0 (WPAI:SHP). Available at: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_SHP.html. Accessed October 25, 2024. [PubMed]

- 28.Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Scoring. Available at: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Scoring.html. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 29.Yu L Buysse DJ Germain A, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System Short Form v1.0 Sleep Disturbance 8b. Available at: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/patient-reported-outcomes-information-system-short-form-v1.0-sleep-disturbance-8b. Accessed October 25, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sleep Disturbance: A brief guide to the PROMIS® Sleep Disturbance instruments. Available at: https://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Sleep_Disturbance_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 31.Murtaza F, Shirreff L, Huang L, Jacobson M, Jarcevic R, Christakis M. Quality and readability of publicly accessible information on menopausal hormone replacement therapy in Canada: what are our patients reading? [abstract]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2021;43:664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold EB Colvin A Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause 2014;21:924–932. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]