Abstract

The management of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) concurrent with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) lacks standardized guidelines, especially concerning surgical strategies. This study aimed to compare unilateral thyroidectomy (UT) with total thyroidectomy (TT) in PTC-HT patients to optimize clinical management and improve postoperative outcomes. This retrospective study included PTC-HT patients undergoing thyroid surgery at a tertiary academic medical institution from January 2018 to August 2023. The patients were grouped according to the quartiles of preoperative thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAB) levels at the last follow-up. Additionally, patients were divided into UT and TT groups, with propensity score matching (PSM) to ensure comparability. Patients were also stratified by TPOAB levels (L: 100–400, M: 400–1000, H: >1000). Patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), including quality of life and fatigue, were compared between UT and TT groups within each TPOAB subgroup (ΔPROMs = UT-TT). 246 patients were included. Those with higher TPOAB levels at the last follow-up reported increased physical fatigue scores. After PSM, there were no significant demographic differences between UT and TT groups. During a median follow-up of 16 months for UT and 20 months for TT, no recurrence or metastasis occurred. Compared to the UT group, the TT group exhibited lower TPOAB levels at the last follow-up (65.7 ± 78 vs. 374.6 ± 331.9, p < 0.001), and lower physical fatigue scores (3.6 ± 2.5 vs. 4.5 ± 2.8, p = 0.039). However, TT was associated with a higher incidence of transient hypoparathyroidism (7.8% vs. 1.1%, p = 0.030). Stratified analysis by preoperative TPOAB levels revealed significant differences in ΔPROMs (Physical fatigue) between L and H groups (0.2 ± 3.5 vs. 4.6 ± 2, p = 0.004) and between M and H groups (0.6 ± 4.5 vs. 4.6 ± 2, p = 0.037). ΔPROMs (Mental fatigue) also significantly differed between L and H groups (0 ± 1.8 vs. 1.6 ± 0.9, p = 0.026). For PTC-HT patients, particularly those with high preoperative TPOAB levels, TT offers advantages in alleviating fatigue symptoms but carries a higher risk of complications. Therefore, clinical decision-making should consider patient-specific factors, particularly preoperative TPOAB levels, to determine the optimal surgical approach.

Trial registration: Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. ID ChiCTR2300069240.

Keywords: Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Unilateral thyroidectomy, Total thyroidectomy, Preoperative thyroid peroxidase antibody, Fatigue, Quality of life

Subject terms: Quality of life, Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Cancer, Immunological disorders

Introduction

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most common malignant tumor of the thyroid gland, accounting for over 90% of all thyroid cancer cases1,2. Concurrently, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT), an autoimmune thyroid disorder, has seen a rising incidence and is now one of the most prevalent autoimmune diseases3,4. Recent epidemiological studies indicate that the coexistence rate of PTC and HT ranges from 10–85%5.

The impact of HT on PTC is complex and dualistic. On one hand, HT is considered a significant risk factor for the development of PTC6,7. Chronic inflammation and immune reactions in HT patients make the thyroid tissue more susceptible to damage, creating a fertile ground for carcinogenesis8. Furthermore, HT patients often have elevated levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which stimulates the proliferation of thyroid follicular epithelium, thereby increasing the risk of PTC development. On the other hand, compared to patients with PTC alone, those with PTC coexisting with HT typically exhibit less extrathyroidal extension and lymph node metastasis, as well as a lower rate of BRAFV600E mutations9. Additionally, patients with concurrent HT have a lower recurrence rate of PTC, which positively influences their long-term prognosis10.

Currently, surgery remains the primary treatment for PTC, but the surgical treatment strategy for patients with concurrent PTC and HT remains unclear. Studies have shown that HT dose not affect the pathological malignant features of PTC11. Therefore, in clinical practice, the extent of surgery is often selected based on standard treatment protocols for PTC12, potentially overlooking the comprehensive impact of HT on patients’ thyroid function and overall health. While PTC treatment guidelines provide general recommendations, they do not fully address the unique circumstances of patients with coexisting HT. Research indicates that HT patients often exhibit elevated serum preoperative thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAB) levels, and severe cases may experience adverse symptoms such as fatigue, decreased sleep quality, and muscle and joint pain. However, these symptoms typically improve after TT, thereby enhancing the quality of life for these patients13,14.

Therefore, further in-depth research is needed to develop more precise and personalized treatment strategies for this patient population, with the goal of improving both their quality of life and long-term prognosis. This study aims to evaluate the differences in postoperative outcomes between UT and TT in PTC-HT patients. By thoroughly understanding the impact of different surgical approaches on these patients, we hope to provide scientific evidence to further optimize clinical management, ultimately enhancing their quality of life and long-term prognosis.

Method

Study cohort

This study was a cross-sectional, retrospective study conducted at a tertiary academic medical institution. We retrospectively collected data on all patients who underwent thyroid surgery between January 2018 and August 2023. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion criteria1: Age > 18 years old2, diagnosis of PTC confirmed by postoperative histology reports3, preoperative TPOAB levels > 100 IU/ml (highly elevated)4,15, preoperative thyroid ultrasound indicating diffuse thyroid parenchymal changes, and5 preoperative laryngoscopy showed no abnormalities.

Exclusion criteria1: Conversion from endoscopic to open surgery2, significant hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism3, history of neck surgery or radiotherapy4, tumor invasion of adjacent structures such as the trachea, esophagus, and nerves5, patients with severe intraoperative adhesions that could prevent the surgery from being completed successfully6, anomalies in recurrent laryngeal nerve anatomy discovered during surgery, such as absence of the recurrent laryngeal nerve7, lateral neck lymph nodes metastasis or distant metastasis8, and loss to follow-up.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Hunan Cancer Hospital. In addition, this study was registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (UIN: ChiCTR2300069240) in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, 2013. All patients agreed that their personal statistics for clinical research and signed informed consent. This study has been reported in line with the STROCSS guideline16.

All the surgeries were performed by the same surgeon. Firstly, the patients were grouped according to the quartiles of TPOAB levels at the last follow-up.

Secondly, according to the extent of surgery, patients were divided into unilateral thyroidectomy (UT) group and total thyroidectomy (TT) group. The Guidelines of the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer17 served as the basis for determining the extent of surgery(UT or TT) in our study. This decision was made through multidisciplinary team(MDT) discussions at our institution, following a comprehensive evaluation of tumor characteristics and other relevant factors. Additionally, preoperative discussions were held with patients to ensure they fully understood the benefits, risks, and implications of each surgical option. The final decision regarding the extent of surgery was made after thorough communication and consideration of the patient’s preferences. The surgical approach (conventional open surgery or transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach) was decided upon through thorough communication between the chief surgeon and the patient.

Finally, patients were stratified by preoperative TPOAB levels (L: 100–400, M: 400–1000, H: >1000). Patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), including quality of life and fatigue, were compared between UT and TT groups within each TPOAB subgroup (ΔPROMs = UT-TT).

Intraoperative neuromonitoring was performed for all patients. Vocal fold function was assessed by laryngoscopy before discharge. According to the CSCO guidelines, all PTC patients are recommended to undergo TSH suppression therapy postoperatively, ensuring that their TSH levels were maintained within the recommended range. Outpatient follow-up was performed at 1-month, 3-months, 6-months, 9- months and 1-year postoperatively. Thereafter, the patients were followed up every 6 months.

Observation indexes and evaluation criteria

The observation indexes were as follows1: Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and preoperative TPOAB levels2. Surgical data, including the extent of surgery (UT or TT), surgical method (open or endoscopic)3. Complications, including transient and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy, transient and permanent hypoparathyroidism, infection, subcutaneous emphysema, seroma, chylous fistula and bleeding. Transient hypoparathyroidism and RLN palsy were defined as occurring for less than six months after surgery. Permanent hypoparathyroidism was defined as subnormal intact parathyroid hormone serum concentrations more than six months after the operation, requiring calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Permanent RLN palsy was defined as failure to recover vocal cord function more than six months184. Postoperative follow-up was conducted in the outpatient clinic, where patients underwent regular evaluations, including thyroid function tests, plasmic electrolytes, parathyroid hormone, and imaging studies (ultrasound or CT). A significant rise in thyroglobulin and a significant mass or enlarged lymph nodes on ultrasonography/CT were used as indicators of recurrence19,20. PROMs were consisted of validated questionnaires, all of which were assessed using online electronic questionnaires to ensure convenience and accessibility. The “Chinese version of Thyroid Cancer-specific Quality of Life (THYCA-Qol) questionnaire” was used to assess the postoperative quality of life (QOL)21. The higher THYCA-QoL scores represent the worse quality of life22,23. Fatigue degree was assessed by fatigue scale-14 (FS-14) questionnaire24–26. These items reflect the severity of fatigue from different aspects and can be divided into two categories, representing physical fatigue and mental fatigue respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were analyzed by the SPSS 26.0. Independent sample t test was used to analyze whether there were differences in PROMs between groups with different TPOAB levels (≤ P50, > P50) at the last follow-up. Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to further investigate the correlation between them. Then propensity score-matched (PSM) analysis was done using a multivariable logistic regression model. According to clinical experience, six factors that may affect postoperative health-related quality of life and fatigue degree, including age, sex, BMI, preoperative TPOAB levels, follow-up time and surgical method were selected as covariables. Pairs of patients receiving UT or TT were derive using 1:1 greedy nearest neighbor matching within propensity score of 0.02. Quantitative data are expressed as mean (SD), classification data are expressed as n (%). Before PSM, independent sample t test was used for quantitative data, Chi-square test for classification data. After PSM, paired t test was used for quantitative data, McNemar test for classification data. Statistical significance was accepted at a p value < 0.05.

Results

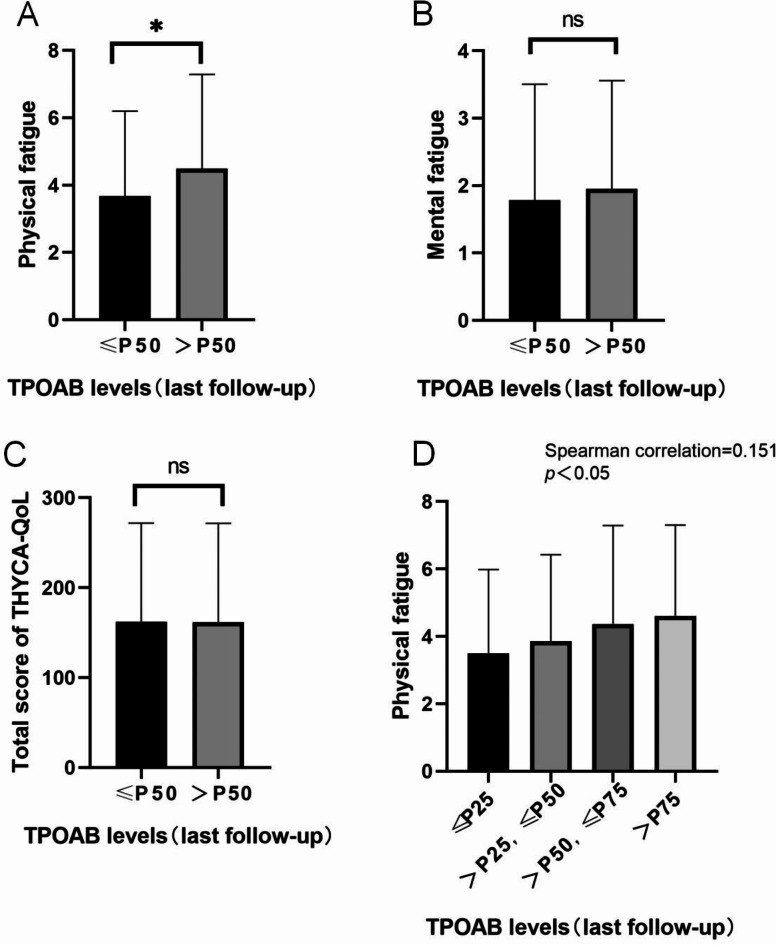

A total of 246 patients were included in this study. The UT group consisted of 125 patients, while the TT group consisted of 121 patients (Fig. 1). At the last follow-up, there was a significant difference in physical fatigue scores between the groups with different TPOAB levels (≤ P50, > P50), while there were no statistically significant differences in mental fatigue scores and THYCA-Qol scores. Further Spearman correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between physical fatigue scores and TPOAB levels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of inclusion, exclusion and propensity score matching.

Fig. 2.

The relationship between PROMs and TPOAB levels. A, Physical fatigue between groups with different TPOAB levels (≤ P50, > P50) at the last follow-up. B, Mental fatigue Figure between groups with different TPOAB levels (≤ P50, > P50) at the last follow-up. C, Total score of THYCA-QOL between groups with different TPOAB levels (≤ P50, > P50) at the last follow-up.D: Spearman correlation analysis showed that physical fatigue scores were positively correlated with the TPOAB levels.

After PSM, 90 pairs of patients remained in the study population. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, BMI, preoperative TPOAB levels, follow-up duration, and surgical approach (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data in UT and TT before and after propensity score matching.

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UT (n = 125) | TT (n = 121) |

P

value |

UT (n = 90) |

TT (n = 90) |

P

value |

|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.352 | > 0.999 | ||||

| Male | 16 (12.8) | 11 (9.1) | 11(12.2) | 11(12.2) | ||

| Female | 109(87.2) | 110 (90.9) | 79(87.8) | 79(87.8) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 37.0 ± 10.0 | 38.4.±11.6 | 0.310 | 37.9 ± 10.2 | 37.8 ± 11.3 | 0.951 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.8 ± 3.5 | 22.6 ± 2.7 | 0.552 | 22.8 ± 3.5 | 22.6 ± 2.6 | 0.700 |

| Surgical method, n (%) | 0.332 | > 0.999 | ||||

| Open | 18 (14.4) | 23 (19) | 13(14.4) | 14(15.6) | ||

| Endoscopic | 107(85.6) | 98(81) | 77(85.6) | 76(84.4) | ||

| Preoperative TPOAB levels, mean (SD), IU/ml | 386.4 ± 291.0 | 539.8 ± 357.7 | < 0.001 | 438.1 ± 317.4 | 456.1 ± 332.7 | 0.472 |

| Follow-up time, median[Q25,Q75], month | 23[11,35] | 19[8.5,30] | 0.008 | 16[8,30.3] | 20[10,30] | 0.344 |

Compared to the UT group, the TT group had lower TPOAB levels at the last follow-up (65.7 ± 78 vs. 374.6 ± 331.9, p < 0.001), as well as lower physical fatigue scores (3.6 ± 2.5 vs. 4.5 ± 2.8, p = 0.039). However, the incidence of transient hypoparathyroidism was higher in the TT group (7.8% vs. 1.1%, p = 0.03). Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the incidence of other complications, THYCA-QoL total scores, and mental fatigue scores. The total number of retrieved lymph nodes was higher in the TT group (15.5 ± 6.7 vs. 12.7 ± 7.4, p = 0.001), along with the multifocality (37% vs. 15%, p = 0.001). Tumor diameters, the number of positive lymph nodes, and the proportion of extrathyroidal extension showed no significant differences between the two groups. No cases of recurrence were observed in either group during the follow-up period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative and follow-up data in UT and TT before and after PSM.

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UT (n = 125) |

TT (n = 121) |

P

value |

UT (n = 90) |

TT (n = 90) |

P

value |

|

| Complications, n (%) | ||||||

| Transient Hypoparathyroidism, n (%) | 1(0.8) | 8(6.6) | 0.015 | 1(1.1) | 7(7.8) | 0.030 |

| Permanent Hypoparathyroidism, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Transient RLN injury, n (%) | 3(2.4) | 6(5) | 0.285 | 3(3.3) | 5(5.6) | 0.469 |

| Permanent RLN injury, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Chylous fistula, n (%) | 1(0.8) | 1(0.8) | 0.982 | 0 | 1(1.1) | NA |

| Seroma, n (%) | 0 | 1(0.8) | 0.308 | 0 | 1(1.1) | NA |

| Infection, n (%) | 0 | 1(0.8) | 0.308 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Histology features | ||||||

| Diameters, mean ± SD, cm | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.579 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.808 |

| Multifocality, n(%) | 16(12.8) | 48(39.7) | < 0.001 | 15(16.7) | 37(41.1) | 0.001 |

| Retrieved lymph nodes, mean ± SD | 10.7 ± 6.3 | 16.7 ± 6.8 | < 0.001 | 12.1 ± 7.4 | 15.5 ± 6.7 | 0.001 |

| Positive lymph nodes, mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 2.3 | 0.205 | 1.1 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 2.5 | 0.405 |

| Extrathyroidal extension | 6(4.8) | 5(4.1) | 0.800 | 6(6.7) | 3(3.3) | 0.508 |

| Follow-up data | ||||||

| TPOAB levels (last follow-up), mean ± SD, IU/ml | 348.4 ± 316.2 | 74.4 ± 101.6 | < 0.001 | 374.6 ± 331.9 | 65.7 ± 78 | < 0.001 |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| PROMs | ||||||

| THYCA-QoL | 152.4 ± 102.5 | 172.2 ± 115.8 | 0.157 | 155.9 ± 105.6 | 165.1 ± 114.7 | 0.583 |

| Fatigue Score-14 | ||||||

| Physical fatigue | 4.3 ± 2.8 | 3.9 ± 2.6 | 0.326 | 4.5 ± 2.8 | 3.6 ± 2.5 | 0.039 |

| Mental fatigue | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.889 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 0.530 |

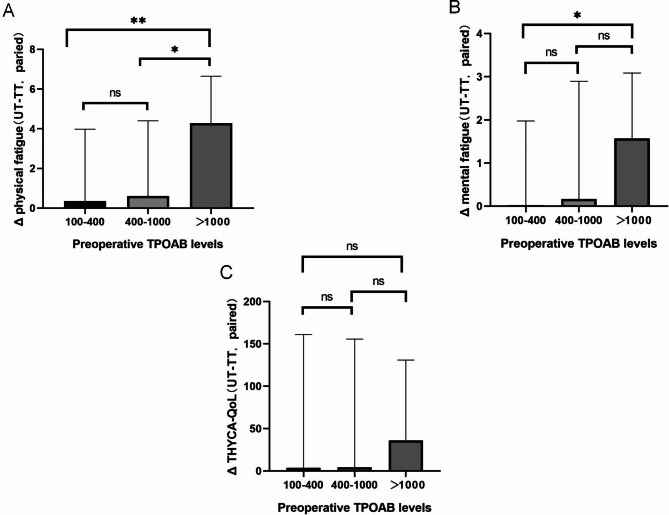

After grouping by preoperative TPOAB levels and performing PSM, the ΔPROMs (UT-TT, paired) were compared between the three groups (L: 100–400, M: 400–1000, H: >1000). The results showed that the difference in Δphysical fatigue scores between the L group and the H group was statistically significant (0.2 ± 3.5 vs. 4.6 ± 2, p = 0.004), and between the M group and the H group was also statistically significant (0.6 ± 4.5 vs. 4.6 ± 2, p = 0.037). The difference in Δmental fatigue scores between the L group and the H group was statistically significant (0 ± 1.8 vs. 1.6 ± 0.9, p = 0.026). There were no significant differences in ΔTHYCA-QoL scores among the three groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The PROMs differences are related to different preoperative TPOAB levels. (A), Physical fatigue. (B), Mental fatigue. (C), Total score of THYCA-QOL.

Discussion

As is well known, PTC, being one of the least malignant tumor types, the optimal surgical extent has always been a topic of controversy. TT provides a lower recurrence rate and facilitates I131treatment, while UT offers patients a better postoperative quality of life27–29. Despite various guidelines detailing factors influencing surgical decisions, HT, frequently coexisting with PTC, has been overlooked1,30. While HT is considered an important risk factor for PTC development, it seems to play a beneficial role in inhibiting the malignant characteristics of PTC and preventing recurrence after surgery10. However, the impact of surgical extent selection on prognosis remains unstudied in PTC-HT patients. Interestingly, in our study, although the TT group underwent more extensive CND and retrieved a higher number of lymph nodes than the UT group, there was no significant difference in the number of metastatic lymph nodes between the two groups. Additionally, following clinical guidelines, patients with multifocal tumors were more likely to undergo TT, which explains the higher proportion of multifocality observed in the TT group. Despite these differences, we found that neither group experienced postoperative recurrence or metastasis, which may be attributed to the favorable impact of HT on the prognosis of PTC. Therefore, in terms of recurrence prevention, the benefits of TT for PTC-HT patients may be less pronounced.

However, it is important to note that as the severity of HT increases, indicated by elevated TPOAB levels31, patients may experience a range of clinical symptoms, including severe fatigue, decreased sleep quality, muscle and joint pain, among others. Research indicates that high TPOAB levels often signal a strong immune system attack on thyroid tissue32. Although elevated TPOAB levels primarily damage thyroid cells, leading to impaired hormone secretion and potentially hypothyroidism, studies suggest that the symptoms associated with HT are not solely due to changes in thyroid hormone levels but are closely related to ongoing autoimmune processes33,34. Elevated serum TPOAB levels correlate with reported fatigue and its severity. This persistent autoimmune reaction may cause the immune system to cross-react with other tissues, resulting in inflammation and non-thyroidal symptoms35. Research indicates that the production of serum TPOAB may not be confined to thyroid tissue alone36,37. Activated lymphocytes may leave the thyroid and invade other distant tissues, spreading immune reactions and inflammation38. Particularly in HT patients with high serum TPOAB levels (greater than 1,000 IU/mL), levels of inflammation-related cytokines such as interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are significantly elevated39. Similarly, in this study, we found a positive correlation between physical fatigue scores and TPOAB levels at the last follow-up. This suggests that higher TPOAB levels may lead to more severe physical fatigue. If alleviating fatigue in HT patients is a priority, targeted treatments addressing TPOAB might be more effective.

Unfortunately, there are currently no effective methods to significantly reduce TPOAB levels. The primary treatment for HT involves replacement therapy to restore thyroid function when hypothyroidism occurs, but this does not lower TPOAB levels13. Studies have shown that selenium intake can partially inhibit the increase in TPOAB levels in HT patients40. Nonetheless, selenium has a narrow therapeutic-toxic-range and it can interact with several commonly used medications41–43. As a result, there are currently no definitive clinical guidelines for its use. Presently, for HT patients with severe symptoms that are difficult to control with medication, TT appears to be an effective option13. This may be because TT can physically remove antigens, thereby suppressing the autoimmune process44. However, whether UT can significantly or partially reduce TPOAB levels has not yet been reported in studies.

Our study indicates that postoperative TPOAB levels significantly decreased in the TT group, whereas the reduction in TPOAB levels was less pronounced in the UT group. In some UT patients, TPOAB levels even continued to rise postoperatively. This phenomenon may be due to the residual thyroid tissue being recognized and attacked by the immune system, thereby maintaining elevated TPOAB levels. Additionally, we observed that postoperative physical fatigue scores were lower in the TT group compared to the UT group. This suggests that TT, by thoroughly removing thyroid tissue and reducing the presence of antigens, effectively suppresses the autoimmune response, resulting in significant improvement in patients’ physical fatigue symptoms44. Conversely, in the UT group, the residual thyroid tissue continued to produce antigens, sustaining the immune system’s attack and failing to significantly alleviate the patients’ physical fatigue symptoms.

Research indicates that UT is more beneficial than TT in improving short-term postoperative quality of life for patients45. However, in our study, there was no significant difference between the two groups. We speculate that this may be due to the persistent autoimmune reaction caused by the residual thyroid tissue in the UT group, which offsets the potential benefits of preserving the thyroid tissue. This suggests that for PTC-HT patient, UT does not significantly improve quality of life. In certain cases, TT might be a more favorable option.

To identify the patient population most likely to benefit from TT, we categorized patients into three groups based on their preoperative TPOAB levels according to various definitions of HT in the literature: L (100–400 IU/mL), M (400–1000 IU/mL), and H (> 1000 IU/mL). We then calculated matched ΔPROMs (UT-TT, paired) for each group. The results indicated that patients with preoperative TPOAB levels > 1000 IU/mL had significantly higher Δphysical fatigue and Δmental fatigue scores compared to patients with lower preoperative TPOAB levels. Although not statistically significant, ΔTHYCA-QoL in the group with preoperative TPOAB levels > 1000 IU/mL was also higher than in the other two groups. This finding is consistent with another study, which demonstrated that in HT patients with significant symptoms (TPOAB levels > 1000 IU/mL), TT significantly improved health-related quality of life and reduced fatigue compared to medical therapy13. Therefore, from the perspective of reducing fatigue, TT may be a better choice for PTC patients with higher preoperative TPOAB levels and more severe clinical symptoms.

However, it is important to note that TT carries a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to UT. In our study, the incidence of transient hypoparathyroidism was significantly higher in the TT group than in the UT group. This finding is consistent with numerous other studies indicating that the extent of surgery correlates with an increased risk of complications46,47. Additionally, HT disrupts normal thyroid tissue and increases the likelihood of intraoperative bleeding, which can complicate surgical procedures and prolong operative time48. Therefore, for PTC-HT patients, surgeons must consider not only the efficacy of recurrence prevention and the surgical risks but also the impact of HT on the quality of life when determining the extent of surgery. This holistic approach will help devise the optimal individualized treatment plan.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, being retrospective, it was unable to assess patients’ preoperative PROMs, which limits the accuracy of evaluating the impact of surgery on these parameters. Moreover, this cross-sectional design prevented us from analyzing the time-dependent pattern of TPOAB changes and its impact on PROMs. Additionally, we did not systematically collect data on other metabolic disorders (e.g., dyslipidemia, elevated glucose levels) that could have impacted postoperative fatigue.

Secondly, the relatively small sample size and the retrospective design of the study limits our ability to control for individual variations in thyroid function parameters, such as TSH, FT3, and FT4 levels, between the two groups. Despite adhering to the CSCO guideline recommendations for TSH suppression therapy, individual differences in hormone levels may have influenced postoperative outcomes, including fatigue.

Lastly, due to the study’s design, only short-term postoperative effects could be observed. The lack of long-term follow-up data may limit a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of surgical choices. Therefore, in future prospective studies, we plan to address these limitations by incorporating a longitudinal design, implementing stricter control measures for thyroid hormone levels, and systematically collecting data on metabolic impacts to provide a more rigorous and comprehensive assessment of the factors influencing postoperative fatigue and overall outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, the choice of surgical extent for patients with PTC coexisting with HT requires comprehensive consideration of multiple factors. Despite the higher risk associated with TT, it significantly mitigates postoperative fatigue, particularly in patients with elevated preoperative TPOAB levels, where the benefits of TT are more pronounced. Therefore, in clinical decision-making, it is crucial to assess the patient’s specific circumstances, particularly focusing on preoperative TPOAB levels, and carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages of TT versus UT to determine the most appropriate surgical approach.

Abbreviations

- PTC

Papillary thyroid carcinoma

- HT

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

- UT

Unilateral thyroidectomy

- TT

Total thyroidectomy

- TPOAB

Thyroid peroxidase antibody

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- BMI

Body mass index

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcomes

- TSH

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- UT

Unilateral thyroidectomy

- TT

Total thyroidectomy

- RLN

Recurrent laryngeal nerve

- QOL

Quality of life

- FS-14

Fatigue scale-14

Author contributions

WXY. ZSW. PXW. and WP wrote the main manuscript text. WXY and ZSW prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3; Table 1, and 2.LW. LH. and SXH participated in the postoperative follow-up.MY. LZY. and CGJ participated in data collection.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2023JJ40419 and 2023JJ60331), Hunan Cancer Hospital Climb Plan (Grant No. ZX2020002 and ZX2021004), Health Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (Grant No. W20243236 and R2023115) and Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. kq2208153, 2023).

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hunan Cancer Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in this study.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study, which included consent to publish anonymous quotes from individual participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoyong Wen and Shiwei Zhou contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Xiaowei Peng, Email: pengxiaowei@hnca.org.cn.

Peng Wu, Email: wupeng@hnca.org.cn.

References

- 1.Haugen, B. R. et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid Cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid Cancer. Thyroid26 (1), 1–133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzmaurice, C. et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer incidence, mortality, years of Life Lost, Years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 Cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol.3 (4), 524–548 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizzo, M. et al. Increased annual frequency of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis between years 1988 and 2007 at a cytological unit of Sicily. Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris). 71 (6), 525–534 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caturegli, P., De Remigis, A. & Rose, N. R. Hashimoto thyroiditis: clinical and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun. Rev.13 (4–5), 391–397 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu, Y., Lv, H., Zhang, S., Shi, B. & Sun, Y. The impact of Coexistent Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis on Central Compartment Lymph Node Metastasis in Papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 772071 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldt-Rasmussen, U. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as a risk factor for thyroid cancer. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes.27 (5), 364–371 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boi, F., Pani, F., Calò, P. G., Lai, M. L. & Mariotti, S. High prevalence of papillary thyroid carcinoma in nodular Hashimoto’s thyroiditis at the first diagnosis and during the follow-up. J. Endocrinol. Investig.41 (4), 395–402 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo, Y. et al. Immunological changes of T helper cells in flow cytometer-sorted CD4(+) T cells from patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Exp. Ther. Med.15 (4), 3596–3602 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu, J. et al. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: a double-edged Sword in thyroid carcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 801925 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu, S. et al. Prevalence of Hashimoto Thyroiditis in adults with papillary thyroid Cancer and its Association with Cancer recurrence and outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open.4 (7), e2118526 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamouri, S. et al. Implications of a background of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis on the current conservative surgical trend towards papillary thyroid carcinoma. Updates Surg.73 (5), 1931–1935 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrinja, C. et al. Hemithyroidectomy versus total thyroidectomy in the intermediate-risk differentiated thyroid cancer: the Italian societies of Endocrine surgeons and Surgical Oncology Multicentric Study. Updates Surg.73 (5), 1909–1921 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guldvog, I. et al. Thyroidectomy Versus Medical Management for Euthyroid patients with Hashimoto Disease and persisting symptoms: a Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med.170 (7), 453–464 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff, G. et al. Thyroidectomy for Euthyroid patients with Hashimoto Disease and persisting symptoms. Ann. Intern. Med.177 (1), 101–103 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn, L. G. et al. Blood lead concentration and thyroid function during pregnancy: results from the Yugoslavia prospective study of environmental lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect.122 (10), 1134–1140 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashid, R. et al. The STROCSS 2024 guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg.110 (6), 3151–3165 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guidelines Working Committee of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology. Guidelines of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) differentiated thyroid Cancer[J]. J. Cancer Control Treat.34 (12), 1164–1201 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayward, N. J., Grodski, S., Yeung, M., Johnson, W. R. & Serpell, J. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in thyroid surgery: a review. ANZ J. Surg.83 (1–2), 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho, J. S. & Kim, H. K. Thyroglobulin levels as a predictor of Papillary Cancer recurrence after thyroid lobectomy. Anticancer Res.42 (11), 5619–5627 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peiris, A. N., Medlock, D. & Gavin, M. Thyroglobulin for monitoring for thyroid Cancer recurrence. Jama321 (12), 1228 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husson, O. et al. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QoL) for thyroid cancer survivors. Acta Oncol.52 (2), 447–454 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldfarb, M. & Casillas, J. Thyroid Cancer-specific quality of life and Health-Related Quality of Life in young adult thyroid Cancer survivors. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 26 (7), 923–932 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura, T. et al. Quality of life in patients with low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: active surveillance Versus Immediate surgery. Endocr. Pract.26 (12), 1451–1457 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, H. et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome treated by the traditional Chinese procedure abdominal tuina: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Tradit Chin. Med.37 (6), 819–826 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, H. et al. Dose-effect of long-snake-like moxibustion for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J. Transl Med.21 (1), 430 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nho, J. H. & Kim, E. J. Relationships among type-D personality, fatigue, and quality of life in infertile women. Asian Nurs. Res. (Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci) (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ryu, C. H. et al. Development and evaluation of a Korean version of a thyroid-specific quality-of-life questionnaire scale in thyroid Cancer patients. Cancer Res. Treat.50 (2), 405–415 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aboelnaga, E. M. & Ahmed, R. A. Difference between papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma outcomes: an experience from Egyptian institution. Cancer Biol. Med.12 (1), 53–59 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrillo, J. F. et al. Prognostic impact of Direct (131)I therapy after detection of biochemical recurrence in Intermediate or High-Risk differentiated thyroid Cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 10, 737 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filetti, S. et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol.30 (12), 1856–1883 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan, H. et al. Discordance of serological and sonographic markers for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with gold standard histopathology. Eur. J. Endocrinol.181 (5), 539–544 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak, S. H. et al. A genome-wide association study on thyroid function and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies in koreans. Hum. Mol. Genet.23 (16), 4433–4442 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bektas Uysal, H. & Ayhan, M. Autoimmunity affects health-related quality of life in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci.32 (8), 427–433 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barić, A. et al. Thyroglobulin Antibodies Are Associated with Symptom Burden in patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: a cross-sectional study. Immunol. Investig.48 (2), 198–209 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punzi, L. & Betterle, C. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and rheumatic manifestations. Joint Bone Spine. 71 (4), 275–283 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Punzi, L. et al. Anti-thyroid microsomal antibody in synovial fluid as a revealing feature of seronegative autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin. Rheumatol.10 (2), 181–183 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blake, D. R., McGregor, A. M., Stansfield, E. & Smith, B. R. Antithyroid-antibody activity in the snyovial fluid of patients with various arthritides. Lancet2 (8136), 224–226 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weetman, A. P., McGregor, A. M., Lazarus, J. H. & Hall, R. Thyroid antibodies are produced by thyroid-derived lymphocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol.48 (1), 196–200 (1982). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karanikas, G. et al. Relation of anti-TPO autoantibody titre and T-lymphocyte cytokine production patterns in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 63 (2), 191–196 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huwiler, V. V. et al. Selenium supplementation in patients with Hashimoto Thyroiditis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of Randomized clinical trials. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 34 (3), 295–313 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duntas, L. H. Reassessing selenium for the management of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: the Selini shines Bright for Autoimmune Thyroiditis patients. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 34 (3), 292–294 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe, L. M., Navarro, A. M. & Seale, L. A. Intersection between obesity, Dietary Selenium, and statin therapy in Brazil. Nutrients ;13(6). (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Basciani, S. & Porcaro, G. Counteracting side effects of combined oral contraceptives through the administration of specific micronutrients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.26 (13), 4846–4862 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weetman, A. P. An update on the pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J. Endocrinol. Investig.44 (5), 883–890 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, W. et al. Association of total thyroidectomy or thyroid lobectomy with the quality of life in patients with differentiated thyroid Cancer with Low to Intermediate Risk of Recurrence. JAMA Surg.157 (3), 200–209 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuba, S. et al. Total thyroidectomy versus thyroid lobectomy for papillary thyroid cancer: comparative analysis after propensity score matching: a multicenter study. Int. J. Surg.38, 143–148 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hauch, A., Al-Qurayshi, Z., Randolph, G. & Kandil, E. Total thyroidectomy is associated with increased risk of complications for low- and high-volume surgeons. Ann. Surg. Oncol.21 (12), 3844–3852 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duffis, E. J. et al. Head, neck, and brain tumor embolization guidelines. J. Neurointerv Surg.4 (4), 251–255 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.