Abstract

Manganese (Mn) is a known toxicant and an essential trace element, and it plays an important role in various mechanisms in relation to cardiovascular health. However, epidemiological studies of the association between blood Mn and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) among U.S. adults are rare. A cross-sectional study of 12,061 participants aged ≥ 20 was conducted using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018. Logistic regression and restricted cubic spline were used to examine the relationship between blood Mn levels and total CVD risk and specific CVD subtypes. Bayesian kernel-machine regression (BKMR) and weighted quantile sum (WQS) analyses were performed to explore the joint effects of Mn with other metals on CVD. The results showed that individuals with the third quartile group of blood Mn levels had significantly lower risks of CVD, displaying a non-linear U-shaped dose-response relationship. A significant interaction of age on this association was observed. No significant associations were found between Mn levels and specific CVD subtypes. BKMR and WQS analyses showed a positive association between heavy metal mixtures and CVD risks, with no interaction between Mn and other metals. In conclusion, blood Mn levels were significantly associated with CVD risks with a U-shaped relationship in U.S. adults, with possible age-specific differences. Future larger prospective studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82673-4.

Keywords: Blood manganese, Cardiovascular diseases, Adults, Cross-sectional study

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Cardiology, Diseases

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide with increased morbidity and mortality, and the high incidence of CVD is becoming an important public health problem1. Between 1990 and 2019, the number of individuals affected by CVD rose from 271 million to 523 million across 204 countries and regions, while CVD-related deaths increased from 12.1 million to 18.6 million2. The prevalence of CVD is estimated at 48.6% in the U.S. general population and increases with age in both males and females3. The development of CVD results from the long-term and complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors. Given the increasing exposure to environmental pollutants, including metals, extensive previous studies have been devoted to elucidating the association between environmental metals and CVD along with their underlying mechanisms. Based on epidemiological and experimental studies, lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) are recognized metals that can cause atherosclerosis and are positively associated with CVD risks4. However, studies concerning the health effects of other heavy metals in the general population, including manganese (Mn), on CVD are scarce.

Mn is a known toxic metal, and excessive exposure to Mn in occupational settings through polluted air and water can result in impaired cognitive function and Parkinson’s disease5,6. However, Mn is also an essential trace element for human beings, necessary for the metabolism of glucose, carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins7. Exposure to Mn occurs primarily through food but can also happen through air, drinking water, or skin contact. Moreover, Mn plays a role in immune functions, bone growth, and cellular energy regulation, and acts as a key cofactor for manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), a major antioxidant for the degradation of superoxide radicals8,9. Given the role of Mn in alleviating oxidative stress, it may have potential benefits on cardiovascular health with its anti-oxidative effect. Previous studies primarily used dietary assessments to estimate levels of Mn exposure and observed an inverse association between dietary Mn with pre-diabetes, diabetes mellitus (DM), metabolic syndrome, and its components10,11, while dietary assessment may be subject to recall bias due to its self-reported nature. Furthermore, some studies assessed Mn levels in urine or blood samples. A previous study reported a negative correlation between urinary Mn and blood pressure, suggesting that it may offer protection against hypertension, a major risk factor for CVD12. Another cross-sectional study in the U.S. found that serum Mn was inversely associated with CVD among older adults aged ≥ 60 years13. Given that the physiological half-life of blood Mn is longer than that of urine Mn, measuring blood Mn may provide a more reliable assessment of Mn body burden exposure14. However, there is still insufficient research on the health effects of Mn on CVD, particularly in the general adult population. Additionally, multiple heavy metals usually have simultaneous exposure in the environment and their interactions might be additive, synergistic, or antagonistic. Therefore, it is also worthwhile to explore the association between Mn and CVD in the context of exposure to mixtures of heavy metals.

Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to investigate (1) the associations and dose-response relationships between blood Mn levels and both total CVD and specific subtypes in the general adult population; (2) the interaction and joint effects of blood Mn and other heavy metals on the risks of total CVD, utilizing nationally representative and large-scale U.S. population-based data.

Methods

Study population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative cross-sectional study to evaluate the health and nutritional status of the general U.S. population through comprehensive interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory measurements. The protocols of NHANES were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). All participants provided written informed consent. All methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki). As this study uses de-identified and publicly available data from the NHANES, it is exempt from institutional review board approval. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

This study includes participants from the NHANES 2011–2018 survey, as blood Mn concentrations were initially measured in 2011. Among the 39,156 participants in the total sample, participants aged < 20 years (n = 16539), those with missing data on blood heavy metals including Pb, Cd, mercury (Hg), and selenium (Se) (n = 7262) or CVD outcomes (n = 148) were excluded. Participants with missing data for covariates (n = 3146), including poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) (n = 1498), educational level (n = 14), physical activity (n = 13), body mass index (BMI) (n = 167), smoking status (n = 6), alcohol use (n = 1426), hypertension (n = 16), and DM (n = 6) were further excluded to ensure the accuracy of the results. Finally, 12,061 participants were included in this analysis (Fig. S1).

Assessment of blood Mn

The blood samples of participants were collected, stored, and transported to the National Center for Environmental Health for analysis. Blood Mn concentrations were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) based on quadrupole technology15. More information regarding the experimental details is available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2011–2012/labmethods/pbcd_g_met_blood-metals.pdf. Typically, the normal range for blood Mn levels is between 4 and 15 µg/L12. The lower detection limit for blood Mn was 1.06 µg/L. If the concentration was below this detection limit, the value was replaced with the detection limit divided by the square root of two.

Assessment of total and specific CVD subtypes

The diagnosis of CVD was established based on self-reported physician diagnoses obtained through individual interviews using a standardized medical condition questionnaire. Participants were asked, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have heart failure (HF)/ coronary heart disease (CHD)/ angina/ heart attack/ stroke?” If a participant replied “yes” to any of the above questions, the participant was regarded as having total CVD16. Furthermore, specific-CVD subtypes information, including HF, CHD, angina, heart attack, and stroke, was extracted to further analyze specific-CVD association with blood Mn. Additional details about the questionnaire are available at (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2011–2012/questionnaires/mcq.pdf).

Covariates

Based on previous literature and the directed acyclic graph (Fig. S2)17,18, the following confounding factors were selected as covariates: demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, PIR), lifestyle factors (smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, BMI), medical history (hypertension and DM). Those covariates were collected through standardized questionnaires and physical examinations. The age subgroup was categorized as < 65 or ≥ 65 years. Race/ethnicity was classified as Mexican American, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or other races. Educational level was divided into less than high school or high school and above. PIR was grouped into < 1.0, 1.0–3.0, or > 3.0. Smoking status was categorized into three groups: current smokers (≥ 100 cigarettes lifetime and continue to smoke), former smokers (≥ 100 cigarettes lifetime but have quit smoking), or never-smokers (< 100 cigarettes lifetime). Alcohol use (yes or no) was defined on the label as whether participants had at least 12 alcoholic drinks/year. Physical activity was assessed based on minutes of moderate-intensity or greater physical activity per week and categorized as either meeting or meeting the recommended minimum of 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week (yes/no). BMI is the weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2) and divided into ≤ 25, 25.1–29.9, ≥ 30 kg/m2. Hypertension and DM were determined according to self-reported history of physician-diagnosed hypertension and DM (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

Data statistical analyses were conducted using survey test weights to ensure nationally representative estimates. Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), while categorical variables were presented as counts (percentages). Participant characteristics with and without total CVD were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. All metal levels were normalized by Log10 conversion and divided into quartiles. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to assess the correlations among Mn and other heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Hg, and Se).

First, the associations between Mn and total CVD and specific CVD subtypes were examined using unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression models. Blood Mn levels were treated as categorical variables, with the third quartile (Q3) as the reference. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for all covariates including age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, PIR, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, BMI, hypertension, and DM. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for other heavy metals based on Model 2. Restricted cubic splines (RCS) with 3 knots (25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles) were employed to detect the dose-response relationships of blood Mn levels with the odds of total CVD and specific CVD subtypes risks, using the median of blood Mn as the reference point. Additionally, subgroup analyses were performed by covariates to explore potential heterogeneities across different subgroups. Several sensitivity analyses were also performed to evaluate the robustness of results: (1) exclusion of participants with Mn levels outside the range of mean ±3*SD to mitigate the impact of extreme values; (2) additional adjusted for diet represented by the Healthy Eating Index-2015 using model 2, considering that Mn is primarily obtained from food as a trace element; (3) Ln-transformed heavy metals levels.

±3*SD to mitigate the impact of extreme values; (2) additional adjusted for diet represented by the Healthy Eating Index-2015 using model 2, considering that Mn is primarily obtained from food as a trace element; (3) Ln-transformed heavy metals levels.

Second, the joint effects of co-exposure to Mn and other heavy metals on the risk of CVD were analyzed by the Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model and the weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression models19,20. The models were adjusted for covariates as mentioned above. In the WQS model, WQS indexes ranging from 0 to 1 represented mixed exposure level of metals, with components identified by corresponding weights. Corresponding weights were examined to identify each metal’s relative contribution within the index to the CVD risk. Samples underwent 1000 iterations of the bootstrap procedures in a training set (40%) and validation set (60%) using the logit link. However, since WQS regression cannot evaluate nonlinearity and interactions of mixtures, BKMR was used to further analyze mixed effects of metals on CVD. The relative importance of each metal in the association with CVD was measured by calculating posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs). Higher PIP indicates greater relative importance. Both univariate and bivariate exposure-response functions assessed single effects and interactions of heavy metals while fixing other included metals at their 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile levels or fixing each included metals at its 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile levels simultaneously. Joint impacts of combined blood metal mixtures on CVD were also summarized compared to their 50th percentile. BKMR models involved 10,000 iterations using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm.

No missing data for variables were observed in the study. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4.1) and SAS (version 9.4), with a two-sided P-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Weighted analysis and mixed exposure analysis were performed utilizing the R packages ‘survey’, ‘gWQS’, and ‘bkmr’.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Among the 12,061 participants included (mean age: 49.6 years, 50.2% female), the prevalence of CVD was 10.6% (n = 1280). The median (IQR) blood Mn concentration was 9.2 ug/L (7.4–11.6 ug/L). Compared to the non-CVD group, participants with CVD tended to be older, male, non-Hispanic white, less educated, physical inactive, current smokers, hypertension, and DM and had lower poverty levels and higher BMI (Table 1). The median value of blood Mn in the CVD group (8.7 ug/L) was lower than that in the non-CVD group (9.3 ug/L). Moreover, individuals with higher concentrations of Log10 blood Mn were younger, more likely to be female, Mexican American, never-smokers, never-drinkers, and had a lower prevalence of hypertension (Table S1). The characteristics of participants included and excluded from the current analysis are presented in Table S2. Those excluded tended to be younger and have higher blood Mn levels, but had a lower proportion of patients with CVD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Variables | Overall (n = 12061) |

Non-CVD (n = 10781) |

CVD (n = 1280) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 49.6 (17.6) | 47.7 (17.1) | 65.8 (12.6) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 6006 (49.8) | 5275 (48.9) | 731 (57.1) | |

| Female | 6055 (50.2) | 5506 (51.1) | 549 (42.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Mexican American | 1487 (12.3) | 1397 (13.0) | 90 (7.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4835 (40.1) | 4179 (38.8) | 656 (51.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2719 (22.5) | 2409 (22.3) | 310 (24.2) | |

| Other Races | 3020 (25.0) | 3795 (25.9) | 224 (17.5) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Less than high school | 2366 (19.6) | 2009 (18.6) | 357 (27.9) | |

| High school and above | 9695 (80.4) | 8772 (81.4) | 923 (72.1) | |

| PIR, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| < 1.0 | 2526 (20.9) | 2215 (20.5) | 311 (24.3) | |

| 1.0–3.0 | 5111 (42.4) | 4464 (41.4) | 647 (50.5) | |

| > 3.0 | 4424 (36.7) | 4102 (38.0) | 322 (25.2) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Never | 6737 (55.9) | 6234 (57.8) | 503 (39.3) | |

| Former | 2960 (24.5) | 2470 (22.9) | 490 (38.3) | |

| Current | 2364 (19.6) | 2077 (19.3) | 287 (22.4) | |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 8942 (74.1) | 8077 (74.9) | 865 (67.6) | |

| No | 3119 (25.9) | 2704 (25.1) | 415 (32.4) | |

| Moderate-intensity physical activity, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 3363 (27.9) | 3162 (29.3) | 201 (15.7) | |

| No | 8698 (72.1) | 7619 (70.7) | 1079 (84.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.5 (7.2) | 29.3 (7.2) | 30.7 (7.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 4474 (37.1) | 3526 (32.7) | 948 (74.1) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2567 (19.2) | 1221 (11.3) | 462 (36.1) | < 0.001 |

| Blood Mn, ug/L, median (IQR) | 9.2 (7.4–11.6) | 9.3 (7.5–11.6) | 8.7 (6.8–10.9) | < 0.001 |

| Log10 blood Mn, ug/L, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CVD: cardiovascular diseases; SD: standard deviation; PIR: poverty-to-income ratio; TC: total cholesterol; BMI: body mass index; Mn: manganese; IQR: interquartile range.

Associations of blood Mn with total CVD and specific CVD subtypes

Table 2 presents the logistic regression results for total and specific CVD subtypes with the blood Mn concentrations categorized into quartiles. After adjustment for all covariates, compared to the third quartile (Q3), the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for total CVD of the first quartile (Q1), second quartile (Q2), and fourth quartile (Q4) were 1.16 (95%CI: 1.02–1.37), 1.08 (95%CI: 0.90–1,29), and 1.08 (95%CI: 0.90–1.30), respectively. The results remained robust even after additional adjustments for other metals in Model 3 (Table 2). The RCS plot showed a significant nonlinear U-shaped dose-response relationship between blood Mn and CVD (P for nonlinearity = 0.009), with the lowest odds of CVD at the blood Log10 Mn concentration of 0.96 ug/L corresponding to the 9.2 ug/L blood Mn concentration (Fig. 1A). Sensitivity analyses of removing extreme values of Mn, further adjusting diet, or Ln-transformed Mn concentrations showed that the associations between Mn and total and specific CVD subtypes remained robust to the main results (Table S3-Table S5). In subgroup analyses by covariates, the U-shaped association was consistently observed only in age subgroups, and a significant interaction was found only between Mn and age (P for interaction < 0.05) (Table S6). Specifically, among individuals ≥ 65 years, blood Mn in the Q1 group was associated with an increased risk of total CVD (OR: 1.25; 95%CI: 1.01–0.59) compared to the Q3 group, and a nonlinear dose-response relationship was also observed (P for nonlinearity = 0.011) (Fig. S3). In addition, for the specific subtypes of CVD, there were 394 (3.3%) HF, 473 (3.9%) CHD, 288 (2.4%) angina, 487 (4.0%) heart attack, and 474 (3.9%) stroke events documented. Both logistic regression and spline analyses showed no significant associations between blood Mn and these specific CVD subtypes (Table 2; Fig. 1B-Fig. 1F).

Table 2.

Associations between blood manganese and total and specific cardiovascular diseases.

| Outcomes | Events/subjects (%) | OR (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Q1 | 414/3016 (13.7%) | 1.51 (1.29–1.78) | 1.16 (1.02–1.37) | 1.18 (1.01–1.40) |

| Q2 | 322/3016 (10.7%) | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 1.08 (0.90–1.29) | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) |

| Q3 | 286/3009 (9.5%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 258/3020 (8.5%) | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||

| Q1 | 130/3016 (4.3%) | 1.41 (1.08–1.85) | 1.05 (0.80–1.39) | 1.06 (0.81–1.40) |

| Q2 | 89/3016 (3.0%) | 0.95 (0.71–1.28) | 0.89 (0.86–1.19) | 0.88 (0.65–1.17) |

| Q3 | 93/3009 (3.1%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 82/3020 (2.7%) | 0.88 (0.65–1.18) | 1.05 (0.78–1.42) | 0.97 (0.72–1.31) |

| Coronary heart disease | ||||

| Q1 | 159/3016 (5.3%) | 1.45 (1.13–1.86) | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 1.08 (0.83–1.39) |

| Q2 | 107/3016 (3.6%) | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) | 0.86 (0.66–1.13) | 0.87 (0.66–1.14) |

| Q3 | 111/3009 (3.7%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 96/3020 (3.2%) | 0.86 (0.65–1.13) | 1.04 (0.79–1.38) | 1.00 (0.75–1.32) |

| Angina | ||||

| Q1 | 85/3016 (2.8%) | 1.25 (0.91–1.73) | 1.06 (0.77–1.46) | 1.08 (0.79–1.49) |

| Q2 | 71/3016 (2.4%) | 1.04 (0.74–1.46) | 1.01 (0.73–1.41) | 1.02 (0.74–1.41) |

| Q3 | 68/3009 (2.3%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 64/3020 (2.1%) | 0.94 (0.66–1.32) | 1.08 (0.77–1.51) | 1.07 (0.76–1.49) |

| Heart attack | ||||

| Q1 | 137/3016 (4.9%) | 1.28 (1.00–1.64) | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 0.93 (0.73–1.19) |

| Q2 | 126/3016 (4.2%) | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) | 1.01 (0.79–1.29) | 1.00 (0.78–1.29) |

| Q3 | 116/3009 (3.9%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 98/3020 (3.3%) | 0.84 (0.64–1.10) | 1.02 (0.78–1.33) | 0.97 (0.75–1.27) |

| Stroke | ||||

| Q1 | 160/3016 (5.3%) | 1.63 (1.26–2.10) | 1.23 (1.00–1.60) | 1.24 (0.96–1.61) |

| Q2 | 118/3016 (3.9%) | 1.18 (0.90–1.55) | 1.12 (0.86–1.48) | 1.12 (0.85–1.47) |

| Q3 | 100/3009 (3.3%) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q4 | 96/3020 (3.2%) | 0.96 (0.72–1.27) | 1.12 (0.84–1.49) | 1.08 (0.81–1.44) |

Quartiles: Q1, Log10 blood Mn < 0.87 ug/L; Q2, 0.87 ≤ Log10 blood Mn < 0.96 ug/L; Q3, 0.96 ≤ Log10blood Mn < 1.06 ug/L; Q4, Log10 blood Mn ≥ 1.06 ug/L. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, poverty-to-income ratio, smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and physical activity. Model 3 was further adjusted for other metals (lead, mercury, cadmium, selenium) based on model 2. Abbreviations: Mn, manganese; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Dose-response relationships between blood manganese and total cardiovascular diseases and specific subtypes. The restricted cubic spline plots showed the dose-response relationships between blood manganese and total cardiovascular diseases (A); and specific cardiovascular disease including congestive heart failure (B); coronary heart disease (C); angina (D); heart attack (E); stroke (F). Model was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, poverty-to-income ratio, smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and physical activity. The solid red lines represent the odds ratios and the red region represents the 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: CVD: cardiovascular diseases; Mn: manganese; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Associations of blood Mn and other heavy metals with total CVD

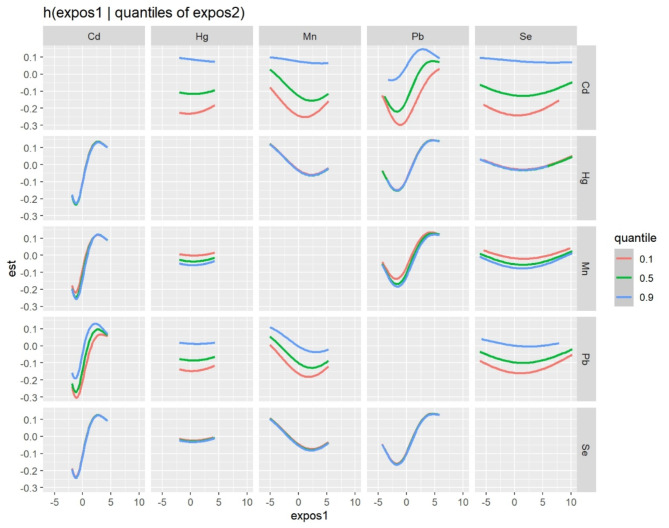

Pearson’s coefficient between Log10-transformed blood metals revealed moderate correlations between Pb and Cd (r = 0.34), while the remaining correlations were relatively poor (Fig. S4). In the BKMR model, after accounting for inter-metal interaction, the relative importance of each metal on the risk of total CVD was quantified using PIPs. The PIP values were 0.77 for Mn, 1.00 for Cd and Pb, 0.46 for Hg, and 0.14 for Se (Table S7). As demonstrated in the exposure-outcome function plot when fixing the other metals at their 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile levels (Fig. S5), or fixing each heavy metal at its 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile levels (Fig. 2), any potential interactions were not observed between blood Mn and other heavy metals in relation to the risk of total CVD. Figure S6 showed a non-linear dose-response relationship between blood Mn levels and total CVD risk when the levels of other heavy metals were fixed at the median. In the overall risk diagram, the joint effect of the blood metal mixture had a positive relationship with CVD (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the WQS model was applied to examine the joint effects of five blood heavy metals on total CVD. As shown in Table S8, the WQS index indicated that heavy metal mixtures were significantly associated with increased risks of CVD (Crude model: OR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.51–1.79; Model 2: OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.19–1.51). Figure S7 showed that Mn had a lower weight (0.01) for CVD risk compared to Pb and Cd, which had weights of 0.51 and 0.48, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Interactive effects between blood metal-metal pairs on cardiovascular diseases by fixing each included metal to its 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile levels. Data were estimated by Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression, while adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, poverty-to-income ratio, smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and physical activity.

Fig. 3.

The joint effects of blood heavy metal mixtures on cardiovascular diseases. All heavy metals at specific percentiles were compared to their 50th percentile levels. Data were estimated by Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression, while adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, poverty-to-income ratio, smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and physical activity.

Discussion

The present study investigated the associations between blood Mn levels and the risks of total CVD and specific CVD subtypes among U.S. general adults in a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Individuals in the third quartile of blood Mn exhibited a significantly lower risk of total CVD among all participants, and those aged ≥ 65 years. The dose-response relationship between Mn and total CVD followed a non-linear U-shaped pattern, consistent with the results from regression analysis. However, no significant associations were observed between Mn and risks of specific CVD subtypes. Further, the joint effects of Mn and other heavy metals on CVD risk were investigated by BMKR and WQS analyses, which revealed that co-exposure to heavy metal mixtures increased the risk of CVD; however, there was no interaction between Mn and other metals. Blood Mn had a lower contributor to the risk of CVD compared to Pb and Cd. These findings provided new evidence of the potential roles of Mn in cardiovascular health and further explore the joint impacts of Mn with multiple metals on CVD.

The association between Mn and CVD is likely complex because Mn is both an essential nutrient and a potential toxicant, depending on the amount of Mn exposure. Similarly, the present study found a non-linear U-shaped association between blood Mn concentrations and total CVD outcomes. Few studies have reported similar results regarding the dose-response relationship between Mn and CVD. A recent study in the U.S. revealed an inverse linear association between Mn and CVD, with 25-hydroxyvitamin D mediating this association21. Another study demonstrated a nonlinear negative relationship between Mn and CVD among older adults ≥ 60 years13. Furthermore, previous research has indicated that Mn plays a significant role in multiple risk factors associated with CVD, such as DM, hypertension, lipid metabolism, and cardiometabolic dysfunction. A case-control study involving 3228 participants in China indicated a U-shaped association between Mn and type 2 DM22. Another study suggested that urinary Mn may contribute to controlling blood pressure and protecting against hypertension12. Two cross-sectional studies among Chinese and Korean populations reported an inverse relationship between dietary Mn and metabolic syndrome risk10,23. The findings of the current study agree with previous studies indicating the protective effect of Mn on cardiovascular health, although not in a linear dose-response relationship. The blood Mn levels (median: 9.2 ug/L) observed in this study were comparable to those reported in prior studies on Mn levels among U.S. adults during the same time period. For instance, a study of 16,572 adults reported a median of 9.1 µg/L and another study among 3080 adults reported a median of 9.4 µg/L24,25. Further, this study expands upon previous research by investigating the associations between Mn and specific subtypes of CVD, such as HF, CHD, stroke, heart attack, and angina. However, no significant relationships were observed between these subtypes and Mn levels possibly due to low event rates and inadequate statistical power resulting from insufficient sample size for each specific subtype examined. Therefore, further studies with larger samples, in particular prospective studies, are needed to explore the association between Mn and various CVD events.

The non-linear association between blood Mn concentrations and total CVD outcomes is biologically plausible. Although the underlying biological mechanisms remain incompletely understood, they may be mainly related to oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are shared pathogenesis associated with Mn exposure and CVD development. On the one hand, Mn acts as a potential antioxidant and co-factor of the enzyme MnSOD. MnSOD serves as the primary antioxidant that eliminates superoxide from mitochondria. Its activity is regulated by MnSOD gene and blood Mn status26. Insufficient levels of Mn leading to suboptimal functioning of MnSOD could result in increased formation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may directly cause macromolecular damage or indirectly induce oxidative stress and inflammation by activating stress-sensitive pathways such as NFkB and p38 MAPK22,27. Activation of these pathways has been demonstrated to contribute to the mitochondrial dysfunction, hormone secretion dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction. On the other hand, Mn is a potential toxicant and oxidant at high levels. Research has shown that excessive Mn levels can result in higher oxidative stress and inflammation by disrupting the antioxidant activity of MnSOD complex within mitochondria while promoting ROS production28. Thus, future studies are warranted to elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between Mn and CVD.

Interestingly, a significant effect modification of age on the association between Mn and CVD was observed. Specifically, the Q3 of blood Mn had a decreased risk of CVD, and a U-shaped relationship was also observed among individuals aged ≥ 65 years but not those < 65 years, which is consistent with a previous study. Xiao et al. investigated the association between Mn and CVD in older adults aged ≥ 60 years and found a nonlinear relationship between blood Mn and CVD13. This finding may be attributed to age-related differences in blood Mn levels and risk of CVD. With increasing age, blood Mn levels decrease while the risk of CVD increases29. Jain et al. reported that among a general U.S. population, blood Mn levels were higher in adults aged 20–64 years compared to seniors aged ≥ 65 years30. The effects on Mn metabolism of age might also explain the interaction of age with the Mn and CVD association31. Future studies should take the age differences into consideration.

By investigating the independent association between blood Mn and CVD, this study has implications for monitoring blood Mn levels for primary prevention of CVD and may provide additional clinical value in identifying individuals at high risk of CVD. A nonlinear Mn-CVD relationship suggested that maintaining appropriate modest levels of blood Mn could exert beneficial effects on CVD. Noteworthy, humans are usually exposed to multiple metals in their daily lives, and research focusing solely on a single metal may cause some degree of bias. Thus, the current study conducted a comprehensive analysis using WQS and BKMR models to further explore the combined impacts of heavy metals exposure on CVD. Both models consistently indicated that combined metal mixtures exposure was positively associated with CVD risk, suggesting that metal exposure may promote CVD progress. Additionally, identifying key metal compounds has important implications for promoting cardiovascular health. In the PIPs and WQS index, Pb and Cd were found to be major contributors to the adverse effects of heavy metals on CVD risk, whereas Mn had a relatively minor role and no interaction with other metals. Pb and Cd are recognized metals with dose-response toxicity towards cardiovascular health32; however, Mn can act as both an essential trace element or toxin depending on its concentration. The variation in the shape of relationship may weaken its role in the overall association of heavy metal mixtures with CVD.

Strengths of the study include a large nationally representative sample of general U.S. adults, standardized data collection methods, and adjustment for multiple covariates. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, given the cross-sectional study design, causality could not be inferred. Second, since CVD was self-reported, recall bias or misclassification may have been introduced. Third, the different characteristics of the included and excluded participants may introduce selection bias. Fourth, residual confounding effects could not be fully addressed, such as genetic factors or medication information. Fifth, blood Mn was measured only once at baseline which limited the possibility of capturing dynamic changes in Mn over time. Future studies with repeated measurements are preferred. Sixth, the relatively small number of specific CVD subtypes may have compromised the statistical power to detect differences in risks. Seventh, in the mixture analysis, due to the limitations of the R packages of BKMR and WQS models, the weights are not well considered, which may introduce bias, resulting in insufficient national representativeness and increasing the risk of false-positive. Finally, the study participants were limited to U.S. adults with complete data for blood Mn and CVD outcomes, thus generalizing these results to other populations remains unclear. Given these limitations, these findings need to be interpreted with caution, and larger prospective cohort studies with long-term follow-up are warranted to verification.

Conclusion

This study suggested that blood Mn levels were significantly associated with the prevalence of CVD with a U-shaped relationship in the general U.S. adult population, and might have age-specific differences. Moreover, joint exposures of blood Mn with other heavy metals increased the CVD risk. More prospective cohort studies and mechanistic studies are warranted to elucidate the roles of Mn in cardiovascular health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the team members and participants in the NHANES for providing the publicly available data.

Author contributions

Data analysis and the first draft of the manuscript were written by BXP. BXP revised the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data used in the present study were obtained from publicly accessible sources. NHANES data described in this study could be available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical declarations

The protocols of NHANES were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). NHANES has obtained written informed consent from all participants. All methods were carried out by the principle embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.76, 2982–3021 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet396, 1204–1222 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin, S. S. et al. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation149, e347–e913 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chowdhury, R. et al. Environmental toxic metal contaminants and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj362, k3310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfalzer, A. C. & Bowman, A. B. Relationships between essential manganese biology and manganese toxicity in neurological disease. Curr. Environ. Health Rep.4, 223–228 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neal, S. L. & Zheng, W. Manganese toxicity upon overexposure: a decade in review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep.2, 315–328 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aschner, J. L. & Aschner, M. Nutritional aspects of manganese homeostasis. Mol. Aspects Med.26, 353–362 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balachandran, R. C. et al. Brain manganese and the balance between essential roles and neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem.295, 6312–6329 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horning, K. J., Caito, S. W., Tipps, K. G., Bowman, A. B. & Aschner, M. Manganese is essential for neuronal health. Annu. Rev. Nutr.35, 71–108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou, B. et al. Dietary intake of manganese and the risk of the metabolic syndrome in a Chinese population. Br. J. Nutr.116, 853–863 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du, S. et al. Dietary manganese and type 2 diabetes mellitus: two prospective cohort studies in China. Diabetologia61, 1985–1995 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu, C., Woo, J. G. & Zhang, N. Association between urinary manganese and blood pressure: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2011–2014. PLoS One. 12, e0188145 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao, S. et al. The association between manganese exposure with cardiovascular disease in older adults: NHANES 2011–2018. J. Environ. Sci. Health Tox Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng.56, 1221–1227 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson, K., Golnick, J., Korn, T. & Angle, C. Manganese encephalopathy: utility of early magnetic resonance imaging. Br. J. Ind. Med.50, 510–513 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou, J., Meng, X., Deng, L. & Liu, N. Non-linear associations between metabolic syndrome and four typical heavy metals: data from NHANES 2011–2018. Chemosphere291, 132953 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, S. et al. Association between urinary thallium exposure and cardiovascular disease in U.S. adult population. Chemosphere294, 133669 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, Q. et al. Association between manganese exposure in heavy metals mixtures and the prevalence of Sarcopenia in US adults from NHANES 2011–2018. J. Hazard. Mater.464, 133005 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo, K. et al. Associations between blood and urinary manganese with metabolic syndrome and its components: cross-sectional analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2016. Sci. Total Environ.780, 146527 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobb, J. F. et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics16, 493–508 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrico, C., Gennings, C., Wheeler, D. C. & Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of weighted quantile sum regression for highly correlated data in a risk analysis setting. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat.20, 100–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, Y. et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D mediates the association between heavy metal exposure and cardiovascular disease. BMC Public. Health. 24, 542 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan, Z. et al. U-Shaped association between plasma manganese levels and type 2 diabetes. Environ. Health Perspect.124, 1876–1881 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi, M. K. & Bae, Y. J. Relationship between dietary magnesium, manganese, and copper and metabolic syndrome risk in Korean adults: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007–2008). Biol. Trace Elem. Res.156, 56–66 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi, X. et al. Associations of mixed metal exposure with chronic kidney disease from NHANES 2011–2018. Sci. Rep.14, 13062 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang, S. et al. Association between blood manganese levels and depressive symptoms among US adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 333, 65–71 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, M. et al. Insights into Manganese Superoxide Dismutase and Human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 15893 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, L. & Yang, X. The Essential Element Manganese, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Diseases: Links and Interactions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 7580707 (2018). (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kaur, G. et al. Affected energy metabolism under manganese stress governs cellular toxicity. Sci. Rep.7, 11645 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oulhote, Y., Mergler, D. & Bouchard, M. F. Sex- and age-differences in blood manganese levels in the U.S. general population: national health and nutrition examination survey 2011–2012. Environ. Health. 13, 87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain, R. B. & Choi, Y. S. Normal reference ranges for and variability in the levels of blood manganese and selenium by gender, age, and race/ethnicity for general U.S. population. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol.30, 142–152 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen, P., Bornhorst, J. & Aschner, M. Manganese metabolism in humans. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 23, 1655–1679 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solenkova, N. V. et al. Metal pollutants and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms and consequences of exposure. Am. Heart J.168, 812–822 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the present study were obtained from publicly accessible sources. NHANES data described in this study could be available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.