Abstract

Individuals afflicted with heart failure complicated by sepsis often experience a surge in blood glucose levels, a phenomenon known as stress hyperglycemia. However, the correlation between this condition and overall mortality remains unclear. 869 individuals with heart failure complicated by sepsis were identified from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database and categorized into five cohorts based on their stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR). The primary endpoints evaluated were mortality within the intensive care unit (ICU), all-cause mortality within 28 days, and all-cause mortality during hospitalization. Cox proportional hazards regression and restricted cubic spline analyses were employed to unravel the association between SHR and mortality. The ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, and 28-day all-cause mortality were 10.01%, 13.69%, and 16.46%, respectively. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed a significant association between elevated SHR and all-cause mortality. After adjusting for confounding variables, elevated SHR was significantly associated with increased risk of ICU mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–2.70)), in-hospital mortality (HR = 1.53; 95% CI, 1.00-2.33)), and 28-day all-cause mortality (HR = 1.49; 95% CI, 1.02–2.17)). Restricted cubic spline analysis demonstrated a significant U-shaped relationship between SHR and the risk of all-cause mortality. This study revealed that stress hyperglycemia ratio is an independent prognostic factor in patients with heart failure complicated by sepsis. Notably, both very high and very low SHR values were associated with increased mortality risk.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82890-x.

Keywords: Stress hyperglycemia ratio, Heart failure, Sepsis, Mortality, MIMIC-IV

Subject terms: Heart failure, Risk factors, Pre-diabetes, Bacterial infection

Introduction

Heart failure stands as a pivotal global health challenge, impacting millions and bearing significant morbidity and mortality1–3. When sepsis complicates heart failure, it engenders sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction and a systemic inflammatory response, amplifying heart failure symptoms and heightening the risk of adverse outcomes4,5. Patients enduring this intersection often find themselves under considerable physiological strain, triggering the release of copious stress hormones, notably epinephrine and cortisol6, aimed at combating the infection. These hormones prompt the liver to unleash glucose, culminating in elevated blood glucose levels and the onset of stress hyperglycemia7. Nevertheless, stress hyperglycemia has the potential to trigger negative consequences by activating mechanisms like oxidative stress7–9.

The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) provides a crucial gauge to assess the relationship between stress-related high blood sugar and disease severity, and it is proposed as a possible marker for predicting negative outcomes in critically ill patients10–14. However, insights into the correlation between SHR and patients suffering from heart failure complicated by sepsis remain scant. Elucidating the effects of SHR on the prognosis of this susceptible cohort could wield profound implications for both clinical management and patient outcomes. Hence, this study sought to explore the link between SHR and all-cause mortality among patients suffering from heart failure complicated by sepsis.

Methods

Data source

Data for this retrospective analysis was extracted from the MIMIC-IV database, an extensive repository administered and curated by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology15. The dataset encompasses 76,943 health records detailing admissions at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center spanning the years 2008 to 2019, encapsulating the healthcare experiences of 53,150 different individuals. Access to the database was provided to author LJS, who was assigned a designated record ID of 59,010,484.

Cohort selection

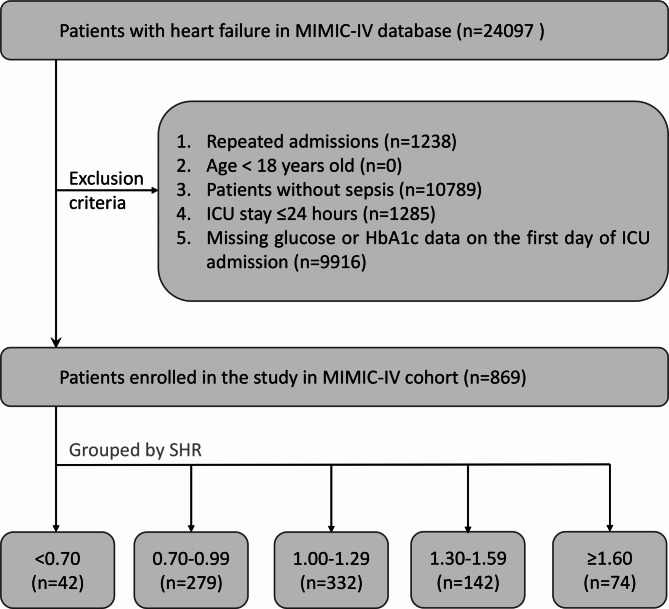

Critically ill patients diagnosed with both heart failure and sepsis were included in this study. Patients diagnosed with heart failure according to the 9th and 10th revisions of the International Classification of Diseases were eligible for inclusion. Sepsis was defined in accordance with the Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock, with suspected infection and an increase in Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of at least 2 points16. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Admission to the hospital occurred when they were under 18 years old; (2) ICU stays lasted fewer than 24 h; (3) Data for blood glucose (BG) and glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were missing. Additionally, data exclusively from the first hospital admission were included for patients with multiple admissions to the ICU. Finally, the study included 869 patients, categorized into five distinct groups according to the SHR levels at intervals of 0.3, ranging from < 0.7 to ≥ 1.6, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating the process of patient selection in MIMIC-IV. MIMIC-IV, the Medical Information Mart in Intensive Care-IV. ICU, intensive care unit; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c. SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of this study was ICU mortality, with secondary endpoints including 28-day all-cause mortality and in-hospital mortality.

Data collection

Utilizing PostgresSQL and NavicatePremium, data extraction was performed through the execution of structured query language (SQL) commands. The variables gathered in this research, which were selected based on a thorough literature review and clinical expertise to identify a set of potential confounding variables, can be classified into six major categories: (1) Demographics, including age, gender, race, weight, and height. (2) Comorbidities, such as cerebrovascular disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, renal disease, mild liver disease, severe liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease, uncomplicated diabetes, complicated diabetes, and malignant cancer. (3) Laboratory tests, including blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, hemoglobin, platelet, red blood cells, sodium, potassium, calcium and creatinine. (4) Severity scores, including acute physiology score III (APS III), SOFA score17, charlson comorbidity index, simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II), and logistic organ dysfunction system (LODS). (5) Vital signs: systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and urine output. (6) Medications and interventions: vasopressors, antibiotics, renal replacement therapy (RRT), and mechanical ventilation. The formula for SHR is as follows18: SHR = BG / (28.7 × HbA1c (%)- 46.7).

To avoid potential bias, variables with more than 20% missing values were excluded (Additional file 1: Table S1). Variables with less than 20% missing data were subjected to multiple imputation using the ‘mice’ package in R19. Multicollinearity between variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor, and variables with variance inflation factor exceeding 5 were excluded from the analysis. (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous parameters was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were reported as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) based on their distribution normality. If continuous variables followed a normal distribution, we employed t-tests or analysis of variance. Conversely, for non-normally distributed continuous variables, we utilized Mann-Whitney U tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Categorical variables were depicted as counts and percentages, and analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests.

Additionally, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed, and inter-group differences were examined using log-rank tests. To elucidate the factors contributing to overall mortality risk, a binary logistic regression analysis was undertaken. Furthermore, Cox proportional hazards models were employed to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) between SHR and outcomes, with select models incorporating adjustments for potential confounding variables. Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 (including variables with P ˂ 0.05 in Table 1): adjusted for cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, platelet count, creatinine, sodium level, urine output, heart rate, SBP, vasoactive medication use, ventilation, uncomplicated diabetes, complicated diabetes, SOFA, SAPS II, APS III, LODS. Model 3 (including variables based on univariate analysis): adjusted for age, temperature, SpO2, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, renal disease, mild liver disease, urine output, antibiotic use, SOFA score, SAPS II, APS III, LODS.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of participants categorized by SHR.

| Categories | Groups (group 1–5) divided by SHR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.70 | 0.70–0.99 | 1.00-1.29 | 1.30–1.59 | ≥ 1.60 | P-value | |

| Number of patients | 42 | 279 | 332 | 142 | 74 | |

| Age, years | 71.2 [63.9, 79.5] | 72.4 [62.6, 81.0] | 72.0 [62.5, 80.1] | 70.8 [62.0, 81.8] | 67.3 [60.8, 78.0] | 0.640 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 13 (31.0) | 114 (40.9) | 131 (39.5) | 59 (41.5) | 34 (45.9) | 0.604 |

| Male | 29 (69.0) | 165 (59.1) | 201 (60.5) | 83 (58.5) | 40 (54.1) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 24 (57.1) | 178 (63.8) | 225 (67.8) | 95 (66.9) | 42 (56.8) | 0.39 |

| Black | 6 (14.3) | 35 (12.5) | 23 (6.9) | 11 (7.7) | 7 (9.5) | |

| Other | 2 (4.8) | 23 (8.2) | 26 (7.8) | 12 (8.5) | 9 (12.2) | |

| Unknow | 10 (23.8) | 43 (15.4) | 58 (17.5) | 24 (16.9) | 16 (21.6) | |

| Weight, cm | 90.0 [67.0, 112.7] | 81.2 [66.9, 99.6] | 81.5 [69.0, 96.5] | 80.0 [64.9, 92.8] | 84.2 [65.0, 102.4] | 0.309 |

| SOFA | 6 [5, 8] | 5 [3.0, 7] | 6 [4, 8] | 6 [4, 9] | 7 [4, 10] | < 0.001 |

| SAPS II | 40 [33, 48] | 37 [31, 45] | 37 [31, 46] | 41 [35, 49] | 41 [34, 49] | 0.001 |

| APS III | 49 [38, 64] | 42 [33, 56] | 41 [31, 54] | 50 [39, 62] | 54 [46, 70] | < 0.001 |

| LODS | 5 [4, 7] | 5 [4, 7] | 5 [4, 7] | 6 [4, 8] | 6 [3, 8] | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 16 (38.1) | 84 (30.1) | 78 (23.5) | 29 (20.4) | 9 (12.2) | 0.003 |

| Dementia | 2 (4.8) | 9 (3.2) | 7 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.7) | 0.669 |

| Rheumatic disease | 1 (2.4) | 8 (2.9) | 14 (4.2) | 8 (5.6) | 3 (4.1) | 0.685 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 20 (47.6) | 88 (31.5) | 111 (33.4) | 45 (31.7) | 28 (37.8) | 0.281 |

| Diabetes with cc | 15 (35.7) | 66 (23.7) | 44 (13.3) | 27 (19.0) | 21 (28.4) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes without cc | 27 (64.3) | 101 (36.2) | 76 (22.9) | 41 (28.9) | 33 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| Renal disease | 22 (52.4) | 111 (39.8) | 107 (32.2) | 58 (40.8) | 38 (51.4) | 0.006 |

| Mild liver disease | 2 (4.8) | 18 (6.5) | 22 (6.6) | 7 (4.9) | 5 (6.8) | 0.949 |

| Severe liver disease | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.327 |

| Malignant cancer | 1 (2.4) | 14 (5.0) | 16 (4.8) | 8 (5.6) | 2 (2.7) | 0.825 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Vasoactive | 21 (50.0) | 132 (47.3) | 212 (63.9) | 81 (57.0) | 43 (58.1) | 0.001 |

| Antibiotic | 35 (83.3) | 223 (79.9) | 278 (83.7) | 117 (82.4) | 65 (87.8) | 0.538 |

| RRT | 1 (2.4) | 6 (2.2) | 14 (4.2) | 10 (7.0) | 5 (6.8) | 0.116 |

| Ventilation | 22 (52.4) | 143 (51.3) | 210 (63.3) | 75 (52.8) | 31 (41.9) | 0.003 |

| Vital signs | ||||||

| SBP, mmHg | 112 [105, 122] | 116 [109, 126] | 111 [104, 120] | 113 [105, 124] | 113[104, 124] | 0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 86 [77, 91] | 81 [74, 89] | 83 [76, 92] | 84 [76, 95] | 85 [75, 102] | 0.028 |

| SpO2, % | 97 [96, 98] | 97 [96, 98] | 98 [96, 99] | 97 [96, 99] | 97 [95, 98] | 0.222 |

| Temperature, ℃ | 36.8 [36.6, 37.1] | 36.8 [36.5, 37.1] | 36.8 [36.6, 37.1] | 36.8 [36.6, 37.1] | 36.8 [36.5, 37.1] | 0.971 |

| Urine output, ml | 1257.5 [841.3, 2244.3] | 1495.0 [1001.0, 2303.5] | 1732.5 [1203.8, 2556.3] | 1405.0[680.0, 2175.0] | 1387.5[663.8, 2183.8] | 0.001 |

| Laboratory test | ||||||

| Platelet, 109/L | 193 [130, 256] | 176 [134, 234] | 162[127, 210] | 172 [130, 237] | 192[146, 275] | 0.012 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.3 [1.0, 2.4] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.6] | 1.6 [0.9, 1.5] | 1.4 [0.9, 2.1] | 1.6 [1.0, 2.6] | < 0.001 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.2 [3.9, 4.7] | 4.3 [4.1, 4.7] | 4.3 [4.0, 4.6] | 4.3 [3.9, 4.8] | 4.3 [4.0, 4.7] | 0.461 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 8.3 [8.0, 8.8] | 8.5 [8.1, 8.8] | 8.3 [8.0, 8.7] | 8.5 [8.1, 9.0] | 8.4 [7.9, 8.9] | 0.053 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 140 [137, 141] | 139 [137, 141] | 138 [136, 141] | 138 [136, 140] | 137[134, 141] | 0.002 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| ICU mortality | 8 (19.0) | 21 (7.5) | 27 (8.1) | 15 (10.6) | 16 (21.6) | 0.001 |

| 28-day mortality | 10 (23.8) | 42 (15.1) | 48 (14.5) | 21 (14.8) | 22 (29.7) | 0.012 |

| Hospital mortality | 10 (23.8) | 34 (12.2) | 35 (10.5) | 20 (14.1) | 20 (27.0) | 0.001 |

SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; APS III, acute physiology score III; SAPS II, simplified acute physiology score II; LODS, logistic organ dysfunction system; Diabetes with cc, diabetes mellitus with complications; Diabetes without cc, diabetes without complications; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SBP systolic blood pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Furthermore, we employed a restricted cubic spline regression model to investigate the nonlinear relationship between SHR and outcomes. We determined the threshold value of SHR by analyzing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. To evaluate the consistency of SHR’s prognostic value for the primary outcome, we performed stratified analyses based on age (dichotomized at 65 years), cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, SOFA score, and antibiotic use. We assessed interactions between SHR and the stratification variables using likelihood ratio tests. Statistical analyses were executed exclusively via R software (version 4.3.1). Significance was attributed to two-sided P-values below 0.05.

Results

This study included 869 patients who presented with heart failure and a concurrent diagnosis of sepsis. ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality and 28-day all-cause mortality were 10.01%, 13.693% and 16.455%, respectively. The median SHR for all participants was 1.08, with an IQR of 0.92 to 1.30. Participants were categorized into 5 different groups based on the SHR levels: <0.70, 0.70–0.99, 1.00-1.29, 1.30–1.59 and ≥ 1.60. Table 1 provides a summary of the baseline characteristics for each of the five groups. Notably, patients in the highest SHR subgroup showed higher severity scores and elevated blood creatinine levels.

Primary outcomes

Compared with other groups, patients in SHR groups 1 and 5 showed higher ICU mortality rates (19.0% vs. 7.5% vs. 8.1% vs. 10.6% vs. 21.6%, P = 0.001), in-hospital mortality rates (23.8% vs. 12.2% vs. 10.5% vs. 14.1% vs. 27%, P = 0.001), and 28-day all-cause mortality rates (23.8% vs. 15.1% vs. 14.5% vs. 14.8% vs. 29.7%, P = 0.012). Further comparisons between group 5 and groups 1–4 were conducted to explore the observed association with mortality. The analysis revealed similar results with different grouping methods (Additional file 1: Table S3). Table 2 presents the baseline characteristic differences between survivors and non-survivors during hospitalization. Non-survivors tended to be older, with higher severity scores, higher incidences of cerebrovascular disease, liver and kidney diseases, elevated platelets and creatinine levels, and were more prone to decreased urine output. Table S4 (Additional file 1: Table S4) illustrates the variables of binary logistic regression analysis for ICU mortality risk in patients with heart failure complicated by sepsis. The results showed that SHR, age, temperature, SpO2, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, renal disease, mild liver disease, urine output, antibiotic, SOFA, APS III, SAPS II and LODS were significant predictive factors.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the survivors and non-survivors groups.

| Categories | Survivors | Non-survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 596 | 273 | |

| Age, years | 70.1 [61.1, 77.8] | 76.2 [66.9, 84.8] | < 0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 219 (36.7) | 132 (48.4) | 0.002 |

| Male | 377 (63.3) | 141 (51.6) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 397 (66.6) | 167 (61.2) | 0.060 |

| Black | 48 (8.1) | 34 (12.5) | |

| Other | 54 (9.1) | 18 (6.6) | |

| Unknow | 97 (16.3) | 54 (19.8) | |

| Weight, cm | 84.0 [70.0, 99.0] | 75.00 [62.0, 96.2] | < 0.001 |

| SOFA | 6 [4, 8] | 6 [4, 9] | 0.078 |

| SAPS II | 37 [30, 45] | 42 [36, 51] | < 0.001 |

| APS III | 40 [31, 53] | 54 [42, 67] | < 0.001 |

| LODS | 5 [4, 7] | 6.00 [4, 8] | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 99 (16.6) | 117 (42.9) | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 9 (1.5) | 13 (4.8) | 0.009 |

| Rheumatic disease | 26 (4.4) | 8 (2.9) | 0.411 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 195 (32.7) | 97 (35.5) | 0.461 |

| Diabetes with cc | 107 (18.0) | 66 (24.2) | 0.041 |

| Diabetes without cc | 183 (30.7) | 95 (34.8) | 0.262 |

| Renal disease | 199 (33.4) | 137 (50.2) | < 0.001 |

| Mild liver disease | 27 (4.5) | 27 (9.9) | 0.004 |

| Severe liver disease | 6 (1.0) | 3 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| Malignant cancer | 24 (4.0) | 17 (6.2) | 0.212 |

| Treatment | |||

| Vasoactive | 367 (61.6) | 122 (44.7) | < 0.001 |

| Antibiotic | 519 (87.1) | 199 (72.9) | < 0.001 |

| RRT | 19 (3.2) | 17 (6.2) | 0.057 |

| Ventilation | 367 (61.6) | 114 (41.8) | < 0.001 |

| Vital signs | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 113 [106, 121] | 114 [105, 127] | 0.409 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 82 [75, 90] | 85 [75, 98] | 0.011 |

| SpO2, % | 97 [96, 99] | 97 [96, 99] | 0.271 |

| Temperature, ℃ | 36.8 [36.6, 37.1] | 36.8 [36.6, 37.1] | 0.633 |

| Urine output, ml |

1692.5 [1118.0, 2600.0] |

1250.0 [675.0, 1965.0] | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory test | |||

| Platelet, 109/L | 167.00 [128.46, 217.25] | 185.50 [140.00, 258.00] | 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 [0.9, 1.5] | 1.5 [1.0, 2.5] | < 0.001 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.3 [4.0, 4.6] | 4.3 [3.9, 4.8] | 0.572 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 8.4 [8.0, 8.8] | 8.5 [8.1, 8.9] | 0.024 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 138 [136, 140] | 139 [136, 142] | 0.149 |

SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; APS III, acute physiology score III; SAPS II, simplified acute physiology score II; LODS, logistic organ dysfunction system; Diabetes with cc, diabetes mellitus with complications; Diabetes without cc, diabetes without complications; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SBP systolic blood pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Table 3 presents the results of a Cox proportional hazards analysis examining the relationship between SHR and ICU mortality rates. Notably, when SHR was examined as a continuous variable, it emerged as a significant risk factor across model 1 [HR, 1.78 (95% CI 1.11–2.85), P = 0.017], model 2 [HR, 1.65 (95% CI 1.19–2.67), P = 0.042], and model 3 [HR, 1.67 (95% CI 1.03–2.70), P = 0.037]. Furthermore, the nominal analysis of SHR demonstrated a strong association between higher SHR groups and increased ICU mortality risk across the three established models: Model 1 [HR, 3.30 (95% CI 1.72–6.33), P < 0.001], model 2 [HR, 3.04 (95% CI 1.51–6.13), P = 0.002], and model 3 [HR, 2.97 (95% CI 1.51–5.83), P = 0.002]. The multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses revealed consistent trends between SHR and both in-hospital mortality rates and 28-day all-cause mortality rates (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard ratios for ICU mortality.

| Categories | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | HR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | HR (95% CI) | P-value | P for trend | |

| ICU mortality | |||||||||

| Continuous variable | 1.78 (1.11–2.85) | 0.017 | 1.65 (1.02–2.67) | 0.042 | 1.67 (1.03–2.70) | 0.037 | |||

| Nominal variable | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.023 | ||||||

| G1 | 2.61 (1.15–5.89) | 0.021 | 1.43 (0.60–3.42) | 0.423 | 1.65 (0.70–3.86) | 0.249 | |||

| G2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| G3 | 1.09 (0.62–1.93) | 0.771 | 1.14 (0.64–2.05) | 0.656 | 1.09 (0.61–1.95) | 0.772 | |||

| G4 | 1.45 (0.74–2.80) | 0.276 | 1.30 (0.65–2.57) | 0.457 | 1.32 (0.67–2.60) | 0.416 | |||

| G5 | 3.30 (1.72–6.33) | ˂0.001 | 3.04 (1.51–6.12) | 0.002 | 2.97 (1.51–5.83) | 0.002 | |||

Model 1 was unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for cerebrovascular disease, diabetes without complications, diabetes with complications, renal disease, platelet count, creatinine, sodium level, urine output, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, vasoactive medication use, ventilation, SOFA, SAPS II, APS III, LODS.

Model 3: adjusted for age, temperature, oxygen saturation, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, renal disease, mild liver disease, urine output, antibiotic use, SOFA score, SAPS II, APACHE III, LODS.

SHR groups: <0.70 (G1), 0.70–0.99 (G2), 1.00-1.29 (G3), 1.30–1.59 (G4) and ≥ 1.60 (G5).

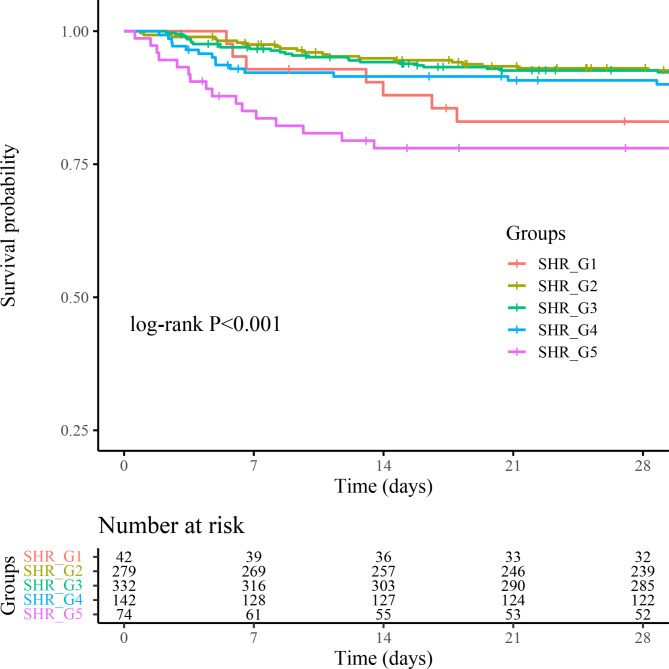

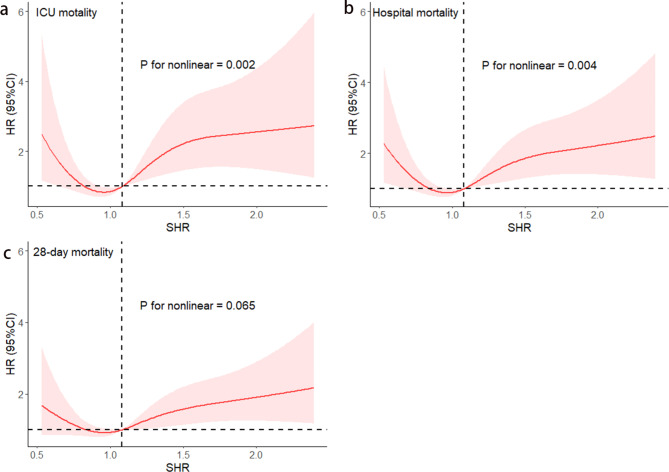

Figure 2 presents Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curves plotted according to SHR grouping to examine the relationship between 28-day mortality rates across distinct groups. Patients with the highest and lowest SHRs show a heightened risk of 28-day mortality. We assessed the clinical efficacy of SHR using ROC analysis. However, the area under curve (AUC) for SHR was less than optimal (ICU mortality AUC: 0.57; in-hospital mortality AUC: 0.55; 28-day all-cause mortality AUC: 0.55). The SHR thresholds for ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, and 28-day all-cause mortality were 1.13, 1.42, and 1.13, respectively. Additionally, the restricted cubic spline regression models reveal a significant U-shaped relationship between SHR and ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, and 28-day mortality (non-linear P = 0.002, non-linear P = 0.004, non-linear P = 0.065) (Fig. 3a, b, c).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves for 28-day all-cause mortality based on distinct groups. Footnote SHR groups: SHR_G1 (< 0.70), SHR_G2 (0.70–0.99), SHR_G3 (1.00-1.29), SHR_G4 (1.30–1.59), SHR_G5 (≥ 1.60).

Fig. 3.

Restricted cubic spline curve for the SHR hazard ratio. Red central lines represent the estimated hazard ratios, with shaded ribbons denoting 95% confidence intervals. SHR 1.08 was selected as the reference level represented by the vertical dotted lines. The horizontal dotted lines represent the hazard ratio of 1.0. (a) Restricted cubic spline for ICU mortality. (b) Restricted cubic spline for hospital mortality. (c) Restricted cubic spline for 28-day mortality. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio.

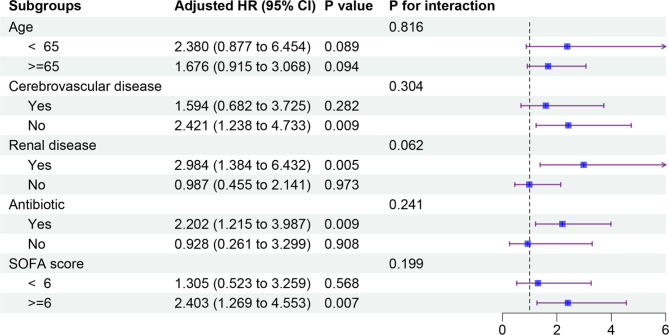

Subgroup analysis

To explore potential effect modifiers, subgroup analyses were performed, stratifying patients based on age, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, antibiotic use, and SOFA score (Fig. 4). A significant association between SHR and ICU mortality risk was observed in several subgroups, including patients without cerebrovascular disease (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.38–4.73), those with renal disease (HR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.38–6.43), those receiving antibiotics (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.22–3.99), and those with a SOFA score ≥ 6 (HR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.27–4.55).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of hazard ratios for the ICU mortality in different subgroups. Adjusted for age, temperature, oxygen saturation, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, renal disease, mild liver disease, urine output, antibiotic use, SOFA score, SAPS II, APACHE III, LODS. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; APS III, acute physiology score III; SAPS II, simplified acute physiology score II; LODS, logistic organ dysfunction system; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

This study investigated the association between SHR and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis complicated by heart failure. Analyzing 869 patients in this group, it was observed that both the high and low SHR groups exhibited higher mortality rates in the ICU, in-hospital, and at 28-day all-cause mortality. Notably, a U-shaped relationship was observed between SHR and mortality rates. These results highlight the importance of SHR as an independent risk factor and its potential clinical utility as a simple and effective prognostic indicator of mortality.

Blood glucose levels at admission do not fully represent a patient’s overall health status20. The SHR, derived by comparing the patient’s blood glucose value with the glycated hemoglobin value, reflects the relationship between blood glucose level and long-term glycemic control under stress and provides a more comprehensive assessment of the metabolic state of blood glucose in patients18. Studies on SHR have been increasing in recent years. A large-scale meta-analysis with a total of 87,974 patients indicated that among acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients, those with higher stress hyperglycemia ratios experienced risks of higher mortality during hospitalization. Subgroup analysis revealed that the outcome was not significantly influenced by diabetic status21. A large-scale database study conducted in China between 2011 and 2019 revealed a U-shaped correlation between stress hyperglycemia ratio and the incidence of severe systemic infections in hospitalized patients with concomitant heart failure and diabetes22. A prospective observational cohort study conducted by Zhou and colleagues revealed that, in patients with acute decompensated heart failure co-occurring with diabetes mellitus, both elevations and reductions in SHR were associated with adverse long-term mortality outcomes10. In line with these observations, our study similarly identified a U-shaped relationship between SHR and mortality outcomes in patients with sepsis complicated by heart failure, including ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, and 28-day all-cause mortality.

Our study provides evidence that SHR can be a valuable prognostic factor in patients with sepsis and heart failure, aiding in the identification of patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes. Compared to other prognostic tools, the advantage of SHR lies in its ease of calculation and its ability to be obtained using routine laboratory data upon patient admission. This makes SHR a practical tool for rapidly and economically assessing patient prognosis in clinical practice. Additionally, our study found that higher or lower levels of SHR resulted in increased short-term mortality in patients with heart failure combined with sepsis. Elevated SHR levels have been linked to an increased risk of death, and this association may be partially attributed to the potential involvement of various pathological pathways, including immune dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress23–25. However, why lower SHR levels also lead to increased mortality rates remains a question. Some literature suggests that low SHR is associated with hypoglycemia10. However, according to our data, the probability of hypoglycemia in patients with SHR less than 0.70 is under 10%. The reason for a low SHR is not due to low blood glucose levels but rather due to elevated HbA1c levels. This indicates that patients with poorly controlled blood glucose prior to admission have a higher mortality rate when presenting with heart failure complicated by sepsis.

The underlying mechanisms of stress hyperglycemia and short-term prognosis in patients with heart failure combined with sepsis are unknown. Immunothrombosis may be a contributing factor to adverse outcomes. Some studies suggest that elevated plasma glucose levels can increase the production of reactive oxygen species26,27, which can damage endothelial cells and activate the coagulation system28,29. During sepsis, systemic immune dysfunction leads to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The mutual activation of immune factors and the coagulation system may result in immune thrombosis, potentially leading to impaired cardiac microcirculation30, compromised myocardial contractility, and exacerbation of heart failure symptoms31.

Critical care medicine emphasizes glycemic control as a cornerstone of patient management. However, current guidelines predominantly focus on glucose levels themselves, neglecting the complex interplay with other metabolic factors. This singular perspective may inadequately capture the metabolic derangements, particularly in patients with heart failure and sepsis. Therefore, we propose a holistic approach to assessing and intervening in the metabolic status of critically ill patients, incorporating the SHR. This approach allows for more precise identification and management of patients requiring personalized glycemic control, potentially improving clinical outcomes. We encourage the clinical application of these findings and further research into the role of SHR in critically ill patient management.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this was a retrospective study and therefore there is an inherent risk of bias. Secondly, it was conducted at a single medical center, limiting the generalizability of the results to other populations. Thirdly, we did not collect data on patients’ glycemic control, thus preventing the assessment of the relationship between SHR and long-term glycemic control. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that SHR serves as a valuable prognostic indicator for patients with heart failure combined with sepsis. As a retrospective observational study, we cannot confirm causality between SHR and mortality; our findings only indicate associations. Further research is required to validate these associations and explore causal pathways.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that SHR may be a valuable predictor of prognosis in patients with heart failure combined with sepsis. Both high and low SHR values are associated with poorer outcomes. However, as this is an observational study, we cannot infer causality from these associations. Further research, including well-designed clinical trials, is warranted to validate our findings and to explore the relationship between SHR and other clinical variables. This research may in the future provide evidence for clinicians to use in the early identification of high-risk patients, thereby enabling proactive interventions and effectively mitigating severe disease consequences.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MIMIC-IV database for providing publicly available data.

Abbreviations

- SHR

Stress hyperglycemia ratio

- MIMIC-IV

Medical Information Mart in Intensive Care-IV

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- APS III

Acute Physiology Score III

- SAPS II

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- LODS

Logistic Organ Dysfunction System

- SQL

Structured query language

- BMI

Body mass index

- RRT

Renal Replacement Therapy

- BG

Blood glucose

- HbA1c

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SpO2

Oxygen saturation

- IQR

Interquartile range

- SD

Standard deviation

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under curve

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

Author contributions

Study design and conception: L.J.S.; data collection and analysis: L.J.S. and J.J.Y.; manuscript drafting: C.X.W. and M.L.; data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript: Z.Y.L., L.Y. and S.W.J . All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Yiwu Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 20-3-111, Grant No. 23-3-74).

Data availability

The data utilized in this study are publicly accessible via the MIMIC-IV database.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The utilization of the MIMIC-IV database was sanctioned by the review boards of both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre. Given the public availability of the data within the MIMIC-IV database, the study was exempt from the need for an ethics approval statement and informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mohebi, R. et al. Cardiovascular disease projections in the United States based on the 2020 census estimates. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.80(6), 565–578 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savarese, G. & Lund, L. H. Global public health burden of heart failure. Cardiac Fail. Rev.3(1), 7–11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziaeian, B. & Fonarow, G. C. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat. Rev Cardiol.13(6), 368–378 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin, H., Wang, W., Lee, M., Meng, Q. & Ren, H. Current status of septic cardiomyopathy: Basic science and clinical progress. Front. Pharmacol.11, 210 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone, F., Liberale, L., Preda, A., Schindler, T. H. & Montecucco, F. Septic cardiomyopathy: From pathophysiology to the clinical setting. Cells11(18), 2833 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hart, B. B., Stanford, G. G., Ziegler, M. G., Lake, C. R. & Chernow, B. Catecholamines: Study of interspecies variation. Crit. Care Med.17(11), 1203–1222 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet (London England)373(9677), 1798–1807 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clement, S. et al. Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals. Diabetes Care27(2), 553–591 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, J. L., Goldfine, I. D., Maddux, B. A. & Grodsky, G. M. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: A unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev.23(5), 599–622 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou, Q. et al. The impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality and rehospitalization rate in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.22(1), 189 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, L. et al. Prognostic significance of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in critically ill patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.22(1), 275 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He, H. M. et al. Simultaneous assessment of stress hyperglycemia ratio and glycemic variability to predict mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: A retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.23(1), 61 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, L. et al. Relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and acute kidney injury in patients with congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.23(1), 29 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, C. et al. Relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and allcause mortality in critically ill patients: Results from the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Endocrinol.14, 1111026 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data10(1), 1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). Jama J Am. Med. Assoc.315(8), 801–810 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent, J. L. et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med.22 (7), 707–710 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts, G. W. et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: Introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.100(12), 4490–4497 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blazek, K., van Zwieten, A., Saglimbene, V. & Teixeira-Pinto, A. A practical guide to multiple imputation of missing data in nephrology. Kidney Int.99(1), 68–74 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding, L. et al. The prognostic value of the stress hyperglycemia ratio for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes: Insights from NHANES 2005–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.23(1), 84 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karakasis, P. et al. Prognostic value of stress hyperglycemia ratio in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review with bayesian and frequentist meta-analysis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med.34(7), 453–65 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhou, Y. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital prognosis in non-surgical patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.21(1), 290 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang, L. et al. AMPK-Dependent YAP Inhibition mediates the protective effect of metformin against obesity-associated endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland)12(9) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Patel, H., Chen, J., Das, K. C. & Kavdia, M. Hyperglycemia induces differential change in oxidative stress at gene expression and functional levels in HUVEC and HMVEC. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.12, 142 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, L. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and mortality in patients with sepsis: Results from 13,199 patients. Infection52(5), 1973–1982 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volpe, C. M. O., Villar-Delfino, P. H., Dos Anjos, P. M. F. & Nogueira-Machado, J. A. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis.9(2), 119 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An, Y. et al. The role of oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol.22(1), 237 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemkes, B. A. et al. Hyperglycemia: A prothrombotic factor? J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH8(8), 1663–1669 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegenga, M. E. et al. Hyperglycemia enhances coagulation and reduces neutrophil degranulation, whereas hyperinsulinemia inhibits fibrinolysis during human endotoxemia. Blood112(1), 82–89 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sörensen, B. M. et al. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes are Associated with generalized microvascular dysfunction: The Maastricht study. Circulation134(18), 1339–1352 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stark, K. & Massberg, S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.18(9), 666–682 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study are publicly accessible via the MIMIC-IV database.