Abstract

The cell painting assay is useful for understanding cellular phenotypic changes and drug effects. To identify other aspects of well-known chemicals, we screened 258 compounds with the cell painting assay and focused on a mitochondrial punctate phenotype seen with disulfiram. To elucidate the reason for this punctate phenotype, we looked for clues by examining staining steps and gene knockdown as well as examining protein solubility and comparing cell lines. From these results, we found that the punctate phenotype was caused by protein insolubility in the mitochondrial matrix. Interestingly, the punctate phenotype of disulfiram was sensitive to the relative expression of LonP1, a protease in the mitochondrial matrix that regulates proteostasis, suggesting that the punctate phenotype manifests when the protein quality control capacity in the mitochondrial matrix is exceeded. Moreover, we discovered that disulfiram and its derivatives, which have all been reported to increase acetaldehyde in the blood after the in vivo intake of alcohol, induced a punctate phenotype as well. The investigated punctate phenotype not only provides a novel clue for elucidating the common mechanism of action among disulfiram derivatives but is also a novel example of chemical perturbation of proteostasis in the mitochondrial matrix.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82939-x.

Keywords: Disulfiram, Cell painting assay, LonP1, Oligomycin A, Protein insolubility, Proteostasis

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Mechanism of action, Screening, Small molecules

Introduction

The cell painting assay is a popular, generalized and broadly applicable method for assessing valuable biological information and the cellular state from morphological changes of fluorescence images1. The images obtained with the cell painting assay can be analyzed to provide data on numerous parameters, including morphology, intensity, localization, and texture. In addition, this approach is a very powerful way to understand biological processes from cell images and show a link with genetics2,3. The advantage of cell painting is not only that we can evaluate the parameters of interest in images, but also that the huge set of parameters obtained from the images enables an unbiased understanding of the mechanisms underlying the perturbations of interest (e.g., small molecules, RNA interference)4,5. Cell morphological profiling using a cell painting assay can help to uncover new aspects of pharmacology6,7 and aid in the identification of novel chemicals8,9. Because most of in vitro assay for pharmacology focuses on short term event for simplicity, we consider that the cell painting assay, in which 48 h exposure is standard, is suitable for exploring new aspects of pharmacology and chemical biology for longer event.

In this study, we performed a cell painting assay to screen for known drugs and bioactive chemicals, with the aim of uncovering novel mechanistic aspects and elucidating biological processes. Based on the results of our screening, we focused on the mitochondrial punctate phenotype, using a known compound, specifically, disulfiram.

Disulfiram is a well-known drug for alcoholism that acts by increasing the aldehyde concentration in the blood after alcohol intake via inhibition of acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs), particularly the low Km ALDH in mitochondria, ALDH210. Historically, the negative impact of disulfiram on alcohol consumption was observed in rubber industry workers exposed to disulfiram, which was used to enhance rubber vulcanization, and these workers became ill after drinking alcohol11. After disulfiram was approved by FDA as an anti-alcoholic treatment in 1951, several reports determined that liver mitochondria were the most critical subcellular component for the oxidation of the acetaldehyde produced by ethanol oxidation in the cytosol12–14. In fact, disulfiram was reported to inhibit oxidation reaction of acetaldehyde in the mitochondrial matrix15. The mode of inhibition for ALDH2 is reported to be irreversible due to covalent bonds at active cysteine residues, and its in vivo efficacy lasts for 1–2 weeks due to the general turnover rate of proteins in the liver10. Because the promiscuous reactivity of disulfiram causes some discrepancies between the in vivo efficacy for anti-alcoholic treatment and the in vitro inhibition for aldehyde oxidation, the exact mechanism by which disulfiram and its metabolites inhibit ALDH2 remains to be elucidated16. In the line with this fact, a variety of in vitro pharmacological mechanisms for disulfiram have been reported due to its reactivity, for example, enzymatic inhibition17, inhibition of pyroptosis18, anti-viral properties19, and many other potential mechanisms of action have been reported. Moreover, a derivative of disulfiram, copper diethyldithiocarbamate complex (CuET), is a well-known anti-cancer agent via interacting with NPLOC4, and disulfiram administration lowered the risks of various cancers in a Danish cohort analysis20.

Results

Mitochondrial punctate phenotype with disulfiram

First, we used a cell painting assay to screen U2OS cells exposed for 48 h to 258 known compounds and then used Cell Profiler to analyze the obtained images. After extracting more than 1000 parameters from the image data, we selected “hit” compounds found to exhibit considerable changes against the standard deviation of blank wells for any parameters and at any dose (Supplementary Table S1). Then, we decided to focus on a signature mitochondrial punctate phenotype associated with disulfiram exposure because disulfiram was known to inhibit mitochondrial function.

We observed that some parts of the cells had some clearly brighter MitoTracker Deep Red punctate signals compared with mitochondria at the cell periphery, indicating that the puncta were distributed mostly around the nucleus (Fig. 1A). Our indicated punctate image in following figures, the peripheral mitochondria looks very pale because the image contrast has been adjusted to brighter punctate. The strength of the punctate phenotype was evaluated by calculating the total puncta area with bright MitoTracker-stained objects for each cell. The dose response of disulfiram on the mitochondrial punctate phenotype was not observed in the typical sigmoidal curves but appeared in a very narrow concentration range (from sub micromolar to about 1–2 µM) (Fig. 1B; refer to following discussion). The calculated EC50 from the data was 127 nM (except for > 1 µM). Regarding the heterogeneity of the cell population, not all of the cells exhibited puncta (Fig. 1C), and those with puncta rarely appeared in the blank condition (0.5% DMSO only). In subsequent time-course experiments with disulfiram, the numbers of puncta increased and saturated with time, and the accumulated puncta did not instantly disappear with washing at 48 h and after 24-h incubation without compounds (Fig. 1D). To explore the cause of the punctate phenotype induced by disulfiram, we continue investigation focusing on only mitochondrial functions because the parameters significantly changed by disulfiram with Cell Profiler analysis were only among mitochondrial staining channel (Supplementary Table S2). At beginning, we observed little change in the mitochondrial membrane potential by tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) staining (Supplementary Fig. S1A) and no major change in the metabolic phenotype with Seahorse XF technology (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Additionally, we attempted to investigate the details and outlines of puncta with super-resolution microscopy, but they were simply too bright to determine the outlines compared with normal peripheral mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Furthermore, when we also tested another mitochondrial staining with anti-TOMM20 antibody, it didn’t make much difference between Blank and disulfiram-treatment in terms of mitochondrial shape and networks, and we also did not observe punctate phenotype like Mitotracker staining (Supplementary Fig. S1D). And because the punctate phenotype was not affected by siRNA treatment of potential responsible genes of disulfiram, ALDH2 and NPLOC4 (via CuET), we considered the phenotype could imply novel mechanism of disulfiram on mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. S1E).

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial punctate phenotype with disulfiram. (A) Representative images of U2OS cells treated with disulfiram for 48 h, obtained by an ArrayScan XTi. Blue pseudocolor shows nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 while red pseudocolor shows mitochondrial staining with MitoTracker Deep Red. To enhance the visualization of puncta in mitochondria, the image contrast was adjusted to reveal only puncta, and not the pale peripheral mitochondria. Scale bar is 100 μm. (B) Dose–response curve for the strength of the punctate phenotype and cell numbers. The total area of puncta per cell as the strength of the punctate phenotype is plotted with lines, and the residual percentage of cell numbers from nuclear staining is plotted with bars, from the well images (9 fields). Data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments testing three replicate wells. The highest concentration was 8 µM with a 1 in 2 dilution. (C) Dose responses of the cell population with puncta on mitochondria staining were plotted as means ± SD at each concentration from triplicate experiments. Exposure time was 48 h. (D) Time dependencies of punctate accumulation were plotted as means from duplicated experiments. Treatment with 0.5 µM disulfiram was stained at 24–72 h exposure time. Solid lines indicate co-incubations, and dotted lines are the results from replacing the medium condition, which was washed with media twice at 48 h exposure, followed by further incubation for 24-h without compounds.

We further investigated the cause and underlying mechanism with that of the punctate phenotype.

Testing siRNA perturbation for a similar punctate phenotype

To ascertain the origin of the puncta in mitochondria with disulfiram, we had to consider other insights in order to understand this punctate phenotype. Because we had realized that the puncta were much brighter than any other normal/peripheral mitochondria with super-resolution microscopy and that the outline of the puncta was vague even with super-resolution imaging, we assumed the possible presence of protein aggregation. We compared images before and after permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100, with a different exposure time for the MitoTracker Deep Red staining channel (Fig. 2A). There were evenly stained mitochondria and fewer puncta before permeabilization. However, the overall MitoTracker signal decreased after permeabilization and puncta appeared. Because puncta staining appeared after stain-off by washing with the detergent, we assumed that the puncta would be detergent-resistant objects that remained after permeabilization with Triton X-100.

Fig. 2.

Image comparison of the punctate phenotype during staining steps and a similar phenotype from mitochondrial gene knockdown. (A) Representative image in grayscale with only MitoTracker channel from treatment with 0.5 µM disulfiram comparing before and after fixation and washing steps. The image on the left was taken just after MitoTracker Deep Red staining following HBSS wash. The image in the middle was taken from the same field but after permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 and the second staining incubation with Hoechst and 0.1% BSA; identical exposure time and contrast as in the left image. The image on the right was taken from the same field after the fixation steps as in the middle image; the contrast is identical, but the exposure time is longer. Scale bar is 100 μm. (B) Evaluation of the punctate phenotype by siRNA knockdown of some genes located in mitochondrial matrix. After preculture for 24-h, cells were transfected with 5 nM of various siRNAs using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX. The blank condition is no treatment, and the positive control was cultured for 48 h with 0.5 µM disulfiram without any transfection. Bars are the mean ± SD of the total mitochondrial puncta area per cell from triplicate experiments testing 12 replicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test versus control groups. * means an adjusted p-value < 0.01. (C) Representative images of siRNA conditions with puncta. Blue shows nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 while red shows mitochondrial staining with MitoTracker Deep Red. Scale bar is 100 μm. (D) Representative image of cells treated with CDDO (LonP1 inhibitor), which perturbs mitochondrial proteostasis.

To investigate the aggregation of mitochondrial protein, we had to consider the role of mitochondrial proteostasis. As is well established, mitochondria play an important role in a range of biological processes, including energy generation, metabolism, cell death, and heat generation. The correct folding and assembly of mitochondrial proteins are essential for these native functions and mitochondria have their own systems and quality control processes for proteostasis21,22, which are affected by pH, ATP concentration, temperature, and protein density23,24. For example, in the event of misfolding or failure in the pre-processing of polypeptides, the proteins will be degraded by an ATP-dependent protease, for example LonP1 (Lon protease-like protein) or ClpxP complex (a family of AAA ATPase) in the mitochondrial matrix, to maintain proper proteostasis and mitochondrial function25. Knockdown of LONP1 is reported to result in mitochondrial protein aggregation, based on mass spectrometry and western blotting, and LONP1 also supports its chaperone function26. We performed MitoTracker imaging with some siRNAs related to protein homeostasis in the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 2B). The changes of cell numbers and the knockdown efficiency by siRNAs treatment were shown in Supplementary Fig. S1F. Cells with knockdown of LONP1 and DNAJA3 (also known as Tid-1, a cofactor of the chaperone mtHSP70) showed an obvious punctate phenotype (representative images and reference compound images are shown in Fig. 2C). The average punctate area per cell was the strongest with LONP1 knockdown and was significantly induced by DNAJA3 knockdown. DNAJA3 knockdown showed an intermediate level, similar to 0.5 µM disulfiram. Although we had assumed that knockdown of HSPA9 (mtHSP-70 protein) would considerably disturb mitochondrial protein homeostasis, mitochondria with HSPA9 knockdown looked very pale and no puncta were observed, which was consistent with a previous report27. As further confirmation, we tested another chemical linked to mitochondrial proteostasis, the LonP1 inhibitor, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) (Fig. 2D). CDDO also resulted in puncta images in the µM range. Both LonP1 and Tid-1 proteins are known to be located in the mitochondrial matrix28,29. Therefore, we hypothesized that the puncta observed with MitoTracker were likely protein aggregates in the mitochondrial matrix.

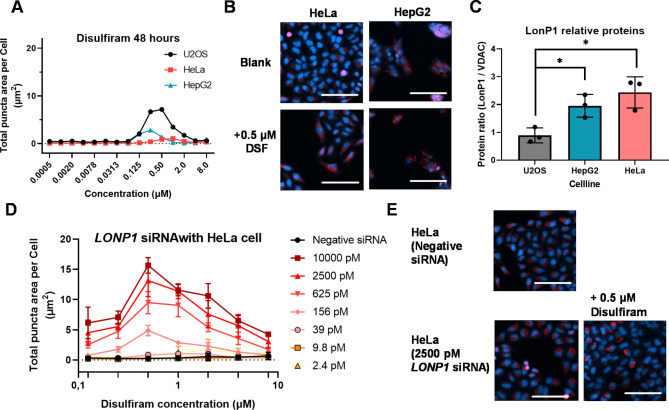

Comparison of the mitochondrial punctate phenotype among cell lines

The most popular cell line for the cell painting assay is the human osteoblastoma cell line U2OS because it has a fairly flat, epithelial-like morphology, which is the most suitable for high-content imaging. Because we wondered if the mitochondrial punctate phenotype would be observed with other cell lines, we also performed the MitoTracker imaging assay with HeLa and HepG2 cell lines. As shown in Fig. 3A, we observed few puncta in HeLa cells with disulfiram. HepG2 cells had some slight puncta, but they were weaker than in U2OS cells. Representative images are shown in Fig. 3B. Because LonP1 is known to be a master regulator of protein homeostasis in the matrix, not only for protease activity but also for supporting chaperone function, we checked the relative expression level of LonP1 protein among the cell lines (Fig. 3C and representative gel image in Supplementary Fig. S2). The amount of LonP1 was lowest in U2OS cells of all three cell lines in terms of the ratio comparing voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) protein in a soluble fraction because VDAC is a marker for total mitochondria. Moreover, we tested the impact of LONP1 knockdown on disulfiram puncta in HeLa cells. Various concentrations of LONP1 siRNA were tested with dose-response experiments of disulfiram (Fig. 3D). Depending on the concentration, LONP1 siRNA caused puncta even in the blank condition, without additional treatment (representative images are shown in Fig. 3E). However, at the same time, a higher concentration of LONP1 siRNA interestingly produced more puncta with disulfiram.

Fig. 3.

Cell line comparison of the mitochondrial punctate phenotype. (A) U2OS, HeLa, and HepG2 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of disulfiram for 48 h after 24-h preculture. The total puncta area per cell with MitoTracker Deep Red stain is plotted with lines, and the percentage of cell numbers from well images is plotted with bars. Data are the mean ± SD from duplicate experiments testing 3 replicate wells. (B) Representative images with the HeLa or HepG2 cell line, with or without disulfiram. Scale bar is 100 μm. (C) Estimation of the relative LonP1 protein expression in these cell mitochondria from western blotting. Ratios are calculated from the total signal of LonP1 and VDAC for each sample and are plotted as the mean ± SD from independent triplicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with t test versus U2OS cells. * means an adjusted p-value < 0.05. (D) Summarized data of HeLa cells under various LONP1 knockdown conditions. Representative results of duplicate experiments are plotted as the mean ± SD from 4 replicate wells. Cells were precultured for 12 h and then transfected with the indicated concentration of LONP1-1 siRNA. After 12 h incubation with siRNA, the cells were replaced with fresh media and further treated with disulfiram for another 48 h. (E) Representative images of HeLa cells with mitochondrial punctate phenotypes. Scale bar is 100 μm.

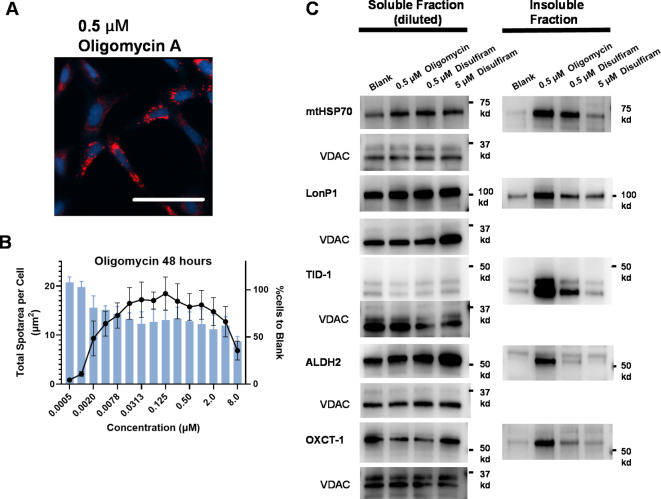

Similar phenotype with oligomycin A and confirmation of protein insolubility from cell lysate

In our screening of known compounds, oligomycin A showed a very similar phenotype to disulfiram (Fig. 4A). Oligomycin A is well-known as an ATP synthase inhibitor that binds to the c subunit of F0 as well as to the F1 region at higher concentrations. The inhibition of ATP synthesis also blocks mitochondrial respiration. Oligomycin A has recently been reported to suppress the growth of cancer cells by itself or combination treatment30. Oligomycin A induced the punctate phenotype across a wide range of concentrations (µM to nM) and showed a stronger and more frequent punctate phenotype than with disulfiram (Fig. 4B). The EC50 was 1.9 nM (except for > 1 µM).

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial punctate phenotype with oligomycin A and protein insolubility by disulfiram and oligomycin A. (A) Representative images obtained using U2OS cells with 0.5 µM oligomycin A. Pseudocolor and contrast are the same as in Fig. 1A. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments testing three replicate wells. Scale bar is 100 μm. (B) Dose–response punctate phenotype of oligomycin A. Plotted in the same way as in Fig. 1B. (C) Evaluation of insolubilization in U2OS cells by treatment with disulfiram and oligomycin. U2OS cells treated with disulfiram in the indicated concentrations were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 and then fractionated into soluble and insoluble fractions. Note that the soluble factions were 1 in 5 dilutions of the original samples. VDAC in the soluble fraction is a reference marker for mitochondrial abundance. ALDH2, TID-1, and OXCT-1 were first blotted and imaged without VDAC antibody and then blotted with the addition of VDAC antibody.

To confirm protein aggregation, we lysed the cells, extracted proteins by fractionation with Triton X-100, and evaluated the presence of several mitochondrial matrix proteins with western blotting (Fig. 4C and original gel images and charts are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3). Testing proteins had been selected from the list of insolubilized mitochondrial proteins by LONP1 knockdown on previous report26. We assessed the insolubility of representative matrix proteins. The matrix protein in the insoluble fraction was well correlated with the MitoTracker image analysis: 5 µM disulfiram did not show many proteins in insoluble fractions, unlike 0.5 µM disulfiram and oligomycin A. The degree to which protein was present in the insoluble fraction varied among proteins but nonetheless confirmed the insolubility of matrix proteins at the concentration range of the punctate phenotype. We have to note that, because the soluble fraction was diluted by one-fifth in this experiment, the amount of protein in the soluble fraction was much larger, except for TID-1. Based on the results of this western blotting analysis, we concluded that disulfiram caused the Triton X-100-resistant insolubility of various proteins in the mitochondrial matrix.

Inhibitory agents for mitochondrial punctate phenotype

When we investigated the relationship between the punctate phenotype and the plating cell density with disulfiram and oligomycin A (Fig. 5A), the total puncta area with disulfiram was greatly impacted by cell density, but this was not the case with oligomycin A. Given this difference in dependency of cell density between disulfiram and oligomycin A, we assumed these compounds had similar punctate phenotype but through different mechanisms.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of the mitochondrial punctate phenotype. (A) Relation between total puncta area and seeding cell density. Treatment with 1 µM disulfiram and 1 µM oligomycin A was obtained at 48 h exposure with various cell densities. The standardized normal condition is 1500 cells/well at seeding. Data are plotted as means from duplicate experiments. (B) U2OS cells were treated with 0.5 µM oligomycin A or 0.5 µM disulfiram for 48 h and co-treated with 5 µM CCCP, 0.1 µM rotenone, or 10 mM NAC. Data are plotted as means ± SD of the total mitochondrial puncta area per cell from triplicate experiments with testing 10 replicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed with t-test versus no combination wells. * means an adjusted p-value < 0.05 while ** means an adjusted p-value < 0.01. (C) Representative images of the inhibitory effect shown in (B). Blue pseudocolor shows nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 while red pseudocolor shows mitochondrial staining with MitoTracker Deep Red. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Therefore, we further investigated combination treatments of specific agents with either disulfiram or oligomycin A and found some agents that blocked the punctate phenotype. These agents, which are known to modify mitochondrial functions, were carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP; a de-coupler), rotenone (a mitochondrial electron transport chain complex I inhibitor), and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; a radical scavenger and an antioxidant or antidote for glutathione deficiency) (Fig. 5B). In particular, 5 µM CCCP and 0.1 µM rotenone inhibited the generation of puncta with 0.5 µM oligomycin A, unlike 10 mM NAC. On the other hand, 10 mM NAC blocked the punctate phenotype with 0.5 µM of disulfiram, unlike CCCP or rotenone. Representative images of the blocking of the punctate phenotype are shown in Fig. 5C. These results suggest that the mechanisms underlying the effects of oligomycin A and disulfiram are different.

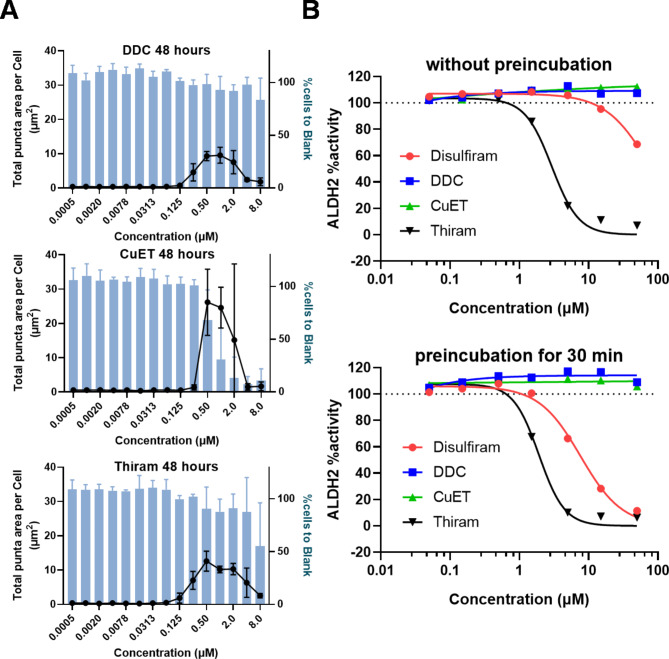

Investigation with disulfiram derivatives

Because our mitochondrial punctate phenotype could be related to the in vivo pharmacology underlying the anti-alcohol effects of disulfiram, we also tested some derivatives of disulfiram. Disulfiram is first rapidly reduced to its metabolite, diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC), in the blood and plasma. Furthermore, one of the derivative compounds of disulfiram that has had a known anti-alcohol effect for more than 50 years is tetramethylthiuram disulfide (named thiram, which is also used as a vulcanization accelerator in rubber factories and as a pesticide). DDC and thiram, which are reported to inhibit the oxidation of acetaldehyde in vivo, induced a punctate phenotype in U2OS cells as well (Fig. 6A). The EC50 values for DDC and thiram were 260 nM and 220 nM, respectively (except for > 1 µM data). CuET, a copper–DDC complex, exhibited the strongest effect but was very cytotoxic at > 1 µM. These results indicated that the range of DDC concentrations for puncta had shifted 2-fold compared with disulfiram, which is consistent with the fact that one molecule of disulfiram produces two molecules of DDC, suggest that DDC might be the active agent. We also tested these compounds with purified recombinant hALDH2 enzyme and found that only disulfiram and thiram inhibited ALDH2 activity both with and without pre-incubation (Fig. 6B). The IC50s of disulfiram and thiram were respectively 4.9 µM and 1.6 µM with pre-incubation and 40 µM and 2.6 µM without pre-incubation. However, DDC did not inhibit purified ALDH2 at all.

Fig. 6.

Investigation of disulfiram derivatives. (A)Total puncta area per cell with MitoTracker staining and the percentage of total cell numbers from nuclei are plotted for DDC, CuET, and thiram. Data are presented as means ± SD from triplicate experiments with 3 replicate wells. (B) Inhibition of ALDH2 enzyme with disulfiram and its derivatives. Because disulfiram is an irreversible and active cysteine attacker, ALDH2 activity was calculated by the change of fluorescence with and without pre-incubation for 30 min with disulfirams. The 100% of ALDH2 activity was calculated from wells with no compound and 0% was calculated from wells without enzyme. Data are presented as the means from duplicate experiments testing 3 replicate wells.

Discussion

In this study, we revealed a novel pharmacological aspect of disulfiram, in which protein insolubility is induced in the mitochondrial matrix, through our investigations of a mitochondrial punctate phenotype based on cell painting assay.

We elucidated the meaning of the punctate phenotype from two perspectives. First, using an imaging approach, we found the puncta images were clearer after treatments such as stain-off by washing with detergent. As a similar phenomenon, staining with Triton X-100 has been reported to reveal tau protein aggregation31. Darker images with a higher contrast after detergent treatment are useful for understanding the aggregation and insolubility of proteins. Some differences between live cell imaging and imaging after permeabilization with fixation is somewhat debatable. Although live imaging more closely reflects physiological conditions, we can also tell that fixation and staining can bring the underlying phenomenon to the surface and that both could be in effect. Moreover, we also presented good examples in which only an image-based cellular phenotype could reveal heterogenous pharmacology.

Second, the presumed protein insolubility with disulfiram was confirmed by western blotting with insoluble fractions, and the insolubility of matrix proteins was correlated with the punctate phenotype. There were two western blot bands in the insoluble fractions for Tid-1 and ALDH2 which supported our hypothesis of insolubility or protein aggregation in the mitochondrial matrix. The shorter Tid-1 (Tid-1 S) translocate into the mitochondrial matrix faster than the longer Tid-1 do32, and the smaller ALDH2 band is reported to be a mature isoform formed by peptidase processing after being imported into the matrix33. Therefore, we concluded that the mitochondrial puncta are the result of perturbed protein homeostasis in the mitochondrial matrix. This protein insolubility effect induced by disulfiram is new knowledge that was obtained because we were able to observe this punctate when the exposure time was longer (6 h did not induce, data not shown) and with a specific cell line.

Next, while attempting to elucidate disulfiram’s punctate phenotype, we observed two phenomena of disulfiram: the dependency of the punctate phenotype on LonP1 expression and the inhibition of the punctate phenotype by NAC. The dependency of LonP1 is consistent with the fact that LonP1 is a critical regulator of protein homeostasis in the mitochondrial matrix and a crucial player in peptide importing, protein folding, and proteolysis in the matrix. Moreover, the inhibition of the punctate phenotype by NAC appears to be consistent with previous reports that cellular pharmacological actions with disulfiram were blocked by NAC34. Considering NAC scavenging as well as the requirement for low LonP1 expression, disulfiram is likely to induce the accumulation of damaged proteins, and the punctate phenotype would result from the capacity of mitochondrial proteostasis being exceeded. The potential reason for this protein insolubility is the extensive cysteine reactivity of disulfiram. Interestingly, disulfiram has been reported to induce the aggregation of betaine ALDH in Pseudomonas aeruginoa35. It has also been reported that another protein thiolate compound similar to disulfiram, methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS), inactivates betaine ALDH in a pH-dependent manner36. Based on the fact that thiolate anion is more reactive at a higher pH37, and taking into account the fact that the mitochondrial matrix exhibits a high pH and protein concentration38, disulfiram is likely more reactive with cysteines of proteins in the mitochondrial matrix compared with any other cytosolic protein. However, the dose dependency of disulfiram’s punctate phenotype is not typical in pharmacology and recovery from the punctate phenotype at higher concentrations was observed. Based on the above, there are two possible mechanisms for this recovery. One is the unfolded protein response, which is reported to be activated by disulfiram39. This cellular response, which aims to maintain protein homeostasis, would have benefits for mitochondria as well. The other hypothesis is related to metallothionein, as previously reported with disulfiram40. We confirmed that MT1X could be upregulated over a 24-h period in the µM range (data not shown). Because metallothionein has cysteine residues in one-third of all amino acids as well as antioxidant properties, an increase in metallothionein proteins would weaken the accumulation of damaged proteins.

We also observed a similar punctate phenotype with oligomycin A, which is reported to inhibit ATP synthase and to have IC50 values of 0.92 µM with a short exposure, and about 5 nM with a > 24-h exposure41,42. The EC50 of mitochondrial puncta was about 2 nM and nearly overlapped with the ATP synthase inhibition range. Accordingly, inhibition of ATP synthase might disturb protein homeostasis via ATP depletion, which has been reported with longer exposures43,44. ATP is essential for most importers (TIM/TOM complexes), major chaperones (mtHSP70, HSP60), and the protease in matrix, and thus the depletion (or reduced concentration) of ATP in the matrix might severely disturb the matrix protein homeostasis. In addition, ATP has itself been reported to support the solubility of proteins as a hydrotrope45 as well as to prevent macromolecular aggregations based on liquid–liquid phase-separated droplet experiments46. CCCP and rotenone, both of which were used in our inhibitory experiments, have been found to prevent the import of polypeptides as well as their further processing in the mitochondrial matrix47,48. This explanation is in line with the ability of CCCP and rotenone to inhibit the oligomycin-induced punctate phenotype because they prevent the excessive import of new peptides into the matrix.

Furthermore, it is quite interesting that all of the disulfiram derivatives led to the punctate phenotype as well. Disulfiram, DDC, and thiram are reported to be effective in vivo for increasing acetaldehyde in blood10,49. This consistency is the first novel knowledge obtained since disulfiram was approved more than 70 years ago. The enzymatic inhibition of ALDHs with disulfiram or its derivatives is controversial due to the nature of its reactivity16. For instance, the commonly accepted responsible enzyme for disulfiram’s efficacy is ALDH2, but the IC50 of disulfiram against ALDH2 in a purified enzyme assay is 10-fold weaker than against cytosolic ALDH1, which has a high Km50, and the inhibition of ALDH2 is not consistent with disulfiram derivatives50,51. In addition, the inhibition of purified ALDH2 is much weaker with glutathione, which is abundant under physiological conditions52. Research on metabolites of disulfiram and ALDH2 conjugates from the liver suggested that S-methyl-N, N-diethylthiocarbamate (MeDTC) sulfone was responsible and a stronger inhibitor for the anti-alcohol efficacy of disulfiram because it increases blood aldehyde levels52. However, this finding based on conjugated proteins is unclear because MeDTC sulfone is too reactive to confirm in blood53. The punctate phenotype obtained with disulfiram and its derivatives in the present study might offer a more consistent in vitro explanation for their in vivo pharmacology than does purified enzymatic inhibition, given that the EC50 of inducing punctate phenotype is 134 nM, which is less than the physiologically achievable concentration, for example about 0.34 µM with 500 mg of disulfiram per day16. In addition, disulfiram is reported to show a slow onset, reaching the maximal inhibitory effect in rat liver acetaldehyde oxidation 18 h to 2 days after oral intake54, despite reports that tmax in plasma was 8–10 h and t1/2 in plasma was 7 h in people55. Furthermore, the in vivo efficacy of disulfiram and DDC has been reported to last for almost a week10. This durability has been explained by irreversible inhibition of the ALDH2 activity core site, but our new observation of the accumulation of damaged protein in the matrix could be another explanation. Interestingly, based on the human protein atlas, LonP1 protein expression is expected to be low in the liver56. However, further in vivo and in vitro investigations are required, particularly concerning the molecular mechanism underlying the acute alcohol digestion response and its specialized mechanism in the liver, known as swift increase in alcohol metabolism (SIAM)57, which stimulates ADP import into mitochondria, fast reoxidation of NADH, and oxygen consumption58. Based on recent progress in enzymology research, it is thought that metabolic inhibition by disulfiram might be related to enzyme dynamics, including substrate channeling, metabolon formation, and the local assembly of protein complexes, either in or with mitochondria59,60. The mitochondrial impairment suggested from the punctate phenotype does not directly explain the in vivo efficacy of disulfiram, but the fact that disulfiram and DDC selectively inhibit CYP2E1 in vivo61 as well as the fact that CYP2E1 is reported to be localized to the mitochondrial matrix, particularly in the liver, are highly suggestive62.

In regarding the morphological changes with the inner component of mitochondrion, the less complexed cristae structures in mitochondria were reported with both of colon enterocyte from LONP1 deficient mouse and synaptic region of a neuron in the hippocampus of disulfiram-treated rat63,64. These commonality, impaired dynamics of cristae structures, might be related with punctate phenotype and protein insolubility although further research will be needed.

In this study, we explored cellular imaging phenotypes and revealed that the mitochondrial punctate phenotype is caused by disturbed protein homeostasis in the mitochondrial matrix by disulfiram and its derivatives as well as oligomycin A. These findings provide some useful clues and a novel perspective for understanding the pharmacological action of disulfiram from cell painting images and also present a novel example of chemical-induced disturbance of proteostasis in the mitochondrial matrix.

Methods

Materials

DMEM (11965-092), MEM (11095-080), HBSS (14065-056), Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Alexa Fluor 594 Conjugate (W11262), Alexa Fluor 594-Phalloidin (A12381), Hoechst 33342 (H3570), Concanavalin A-Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate (C11252), SYTO-13 (S7575), MitoTracker Deep Red (M22426), and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (13778-075) were purchased from Invitrogen. BSA (A8806), 10% Triton X-100 (93443), oligomycin A (75351), sodium DDC (228680), NAC (A9165), CCCP (C2759), rotenone (R8875), and tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate (87917) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Other items were purchased from the following manufacturers: FBS (Nichirei; 174012), accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies; AT-104), PBS (Nacalai; 14249-24), 16% paraformaldehyde (Alfa Aesar; 43368), Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 78438), Tris buffer (Nippon Gene; 318-90225), disulfiram (Tocris; 3807, purity checked), copper (II) diethyldithiocarbamate (TCI; D0487, CuET), tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TCI; B0486), CDDO (Cayman Chemical; 81035), Opti-MEM (Gibco; 31985062), XF Cell Energy Phenotype Test (Agilent Technologies; 103325-100), SuperPrep II Cell Lysis & RT Kit for qPCR (TOYOBO; SCQ-401), and THUNDERBIRD Probe One-step qRT-PCR Kit (TOYOBO; QRZ-101).

The following siRNA was used: Silencer Select Negative Control No. 1 siRNA (Thermo Fischer Scientific; 4390843), NPLOC4 siRNA([AssayID] s31209), LONP1 siRNA ([AssayID] s17902, s17903), CLPX siRNA ([AssayID] s21287, s21288), DNAJA3 siRNA ([AssayID] s17346, s17347), HSPA9 siRNA ([AssayID] s6989, s6990), PMPCB siRNA ([AssayID] s18239, s18240), and ALDH2 siRNA ([AssayID] s1239, s1240). TaqMan Gene Expression Assay probes were purchased from Thermo Fisher, as 18 S (VIC; Hs99999901_s1), ALDH2(FAM; Hs01007998_m1), NPLOC4 (FAM; Hs00215606_m1), MT1X(FAM; Hs00745167_sH), LONP1(FAM; Hs00998404_m1), CLXP(FAM; Hs01101010_m1), DNAJA3(FAM; Hs00170600_m1), HSPA9(FAM; Hs00269818_m1), PMPCB(FAM; Hs00188704_m1). Another mitochondrial staining for mitochondrial shapes and networks, we utilized AlexaFluo594 anti-TOMM20 antibody (Abcam; ab210665, 1/1000). The following western blotting antibodies were used: anti-GRP75 antibody (Proteintech; 67563-1-lg, diluted 1:5000), anti-VDAC1/Porin + VDAC3 antibody (Abcam; ab14734, 1:1000), anti-LONP1 (Cell Signaling Technology; 28020, 1:1000), anti- TID-1 L/S antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-18819, 1:1000), anti-ALDH2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 18818, 1:1000), anti-OXCT1 antibody (Proteintech; 67836-1-Ig, 1:5000), anti-rabbit IgG/HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 7074, 1:2000), and peroxidase-conjugated Affinipure goat anti-mouse IgG (Proteintech; SA00001-1, 1:10000). The antibodies were detected using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 34095). This study did not generate any new unique reagents.

Cell culture

U2OS and HepG2 cells were obtained from ATCC (USA) and HeLa cells were obtained from the JCRB Cell Bank (Japan). U2OS cells were grown to subconfluence in normal growth media comprising DMEM plus 10% FBS at 37 °C in a water-saturated atmosphere of 5% CO2 with splitting every 2–4 days. HeLa and HepG2 cells were grown to subconfluence in MEM with 10% FBS at 37 °C in a water-saturated atmosphere of 5% CO2 with splitting every 2–4 days. For the cell painting assay and other tests, cells under subconfluent conditions were harvested by accutase and seeded onto poly-D-lysine (for U2OS) or collagen I (for HeLa and HepG2)-coated 384-well clear-bottom black plates (Corning, BioCoat series) at a density of 1500 cells/well (U2OS and HeLa) or 3000 cells/well (HepG2 only). All cell lines were mycoplasma negative and used for assay under 30 passages.

Chemical treatment and other perturbations

For the screening of imaging phenotypes with various compounds, 258 compounds were diluted from 10 mM stock solution in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Of these, most of bioactive compounds were purchased from Selleck (USA), and the rest was provided by the Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Compound Library. For the assay, stock solution of compounds was diluted with 1 × Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) buffer to a final concentration of 0.5% DMSO. Compounds were tested with 8 doses in duplicate and the highest concentration was 25 µM (dilution factor, 2) for primary screening.

Cell painting assay

We used a modified version of the original cell painting assay protocol2,65. Briefly, we replaced SYTO-14 with SYTO-13 in accordance with our imager and reduced the channels to increase the throughput. The staining targets were the same: Hoechst for nuclei, WGA for membranes and Golgi, phalloidin for F-actin, concanavalin A for the endoplasmic reticulum, SYTO-13 for nucleoli, and MitoTracker Deep Red for mitochondria). All washing, loading, and replacing steps were conducted with an EL406 plate washer to leave 10 µl/well in wells, followed by the dispensing of 30 µl/well of loading dye buffer or 80 µl/well of 1 × HBSS buffer for washes.

As a 24-h pre-incubation after cell plating and dilution of the compound in DMSO with DMEM (dilution, 1:20), we transferred the compound solution to the cell plate using a Biomek FX dispenser and incubated the cells for another 48 h at 37 °C (final DMSO concentration, 0.5%). After 48 h treatment, the medium was replaced with culture medium containing a loading solution of 500 nM MitoTracker Deep Red and 33 µg/ml Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Alexa Fluor 594 Conjugate in DMEM with serum (10 µl residual + 30 µl of loading reagent. Same hereafter). After 30 min loading at 37 °C and 5% CO2, a one-fifth volume of 16% paraformaldehyde was added. After a 12-min incubation at room temperature, the cells were washed four times with HBSS buffer by the plate washer. The buffer was then removed and replaced with HBSS buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for permeabilization for 12 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed twice with HBSS buffer and were incubated with 8.1 µM Hoechst 33342 Solution, 66 nM Phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 594, 50 µg/ml Concanavalin A-Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate, and 1.5 µM SYTO-13 in HBSS buffer with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After 30 min incubation at room temperature, the cells were washed four times with HBSS buffer and then each plate was heat-sealed by PlateLoc.

MitoTracker imaging assay

To explore the mitochondrial phenotype and based on the above modified protocol for the cell painting assay, we conducted staining with MitoTracker Deep Red and Hoechst 33342 alone using the same steps, but without WGA, concanavalin A, and SYTO-13 staining. The total cell numbers and the strength of the punctate phenotype were estimated from the total area of puncta per cell in the image field, using the analysis protocol (Spot Detector V4) on Array Scan HCS Studio ver. 6.5. For washing experiment, the cells were incubated with disulfiram for 48 h, and then the cultured medium was discarded with washing and replaced by fresh medium for further 24-h incubation.

Image acquisition and analysis

Stained cell plates were measured with an ArrayScan XTi. The four detection channels for our modified cell painting assay were emission wavelengths of 386, 485, 560, and 650 nm while the channels for the MitoTracker imaging assay were emission wavelengths of just 386 and 650 nm. A 20× dry objective was used and the image size was 1104 × 1104 (2 × 2 binning). All images were analyzed with Cell Profiler v1.1 MATLAB software (Broad Institute). By using Cell Profiler, images were converted to 1188 parameter values for various image features. For compound selection, the Z-score for each parameter was calculated from the standard deviation of each parameter in blank wells. Any compounds that showed a parameter Z-score > 8.0 in duplicate was regarded as a “hit” (69 compounds). These compounds (and the concentrations) were further analyzed by hierarchal clustering with all 1188 parameters using TIBCO Spotfire software. The clustering method was that of UPGMA with cosine correlation as the distance after normalization by means, and the ordering weight was the input average rank.

siRNA perturbation test

The siRNA experiments were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The culture conditions of knockdown experiments are described as below.

We tested changes of mitochondrial punctate phenotype by the knockdown of putative and responsible genes of disulfiram, ALDH2 and NPLOC4 (final 6 nM siRNA). Cells were plated at 1500 cells/well and pre-incubated by 24-h. The transfection condition was pre 24-h transfection with siRNA and treated with disulfiram, replaced by fresh medium and then following 24-h with disulfiram. We estimated the knockdown efficiency by qPCR compared with Mock condition.

To explore similar mitochondrial punctate phenotype by siRNAs, we selected and screened the following siRNA targeting genes involved in mitochondrial matrix proteostasis: LONP1, an ATP-dependent serine protease; CLPX, an ATP-dependent protease and compartment of the ClpxP complex; DNAJA3, a co-factor of the mtHSP70 chaperone; HSPA9, a mtHSP70 chaperone; and PMPCB, a component of a mitochondrial-processing peptidase. The culture condition to screen responsible gene causing punctate phenotype was like those of the cell painting assay, with 384-well plates, 1500 cells/well. After the cells were preincubated for 8 h, transfection reagent was added (final 5 nM siRNA). After 24-h incubation at 37 °C, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium. After a further 24-h incubation, the cells were stained with MitoTracker as above.

For the LONP1 knockdown assay in HeLa cells, pre-incubation was 12 h and the cells were further cultured with transfection reagent and various concentrations of siRNA for 12 h before the transfection medium was replaced with fresh culture medium. After the transfection, the cells were treated with various concentrations of disulfiram for 48 h and then stained with MitoTracker before image analysis.

Soluble/insoluble fractionation with Triton X-100

Cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes and treated with compounds for 48 h. The cells were detached with accutase and collected at 1.5 × 106 cells for each treatment. The pellet was washed with PBS once and then lysed on ice for 30 min with 250 µl of Triton X-100 buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) containing Halt protease inhibitor. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain supernatant (soluble) and pellet (insoluble) fractions. The pellet fractions were washed and centrifuged with Triton X-100 buffer twice, and the insoluble pellets were reconstituted in 250 µl of Triton X-100 lysis buffer. Soluble fractions were diluted 1 in 5 with lysis buffer and mixed with sample buffer. For insoluble fractions, the pellet was pipetted well, sonicated for 2 min, and mixed with sample buffer. After being boiled at 95 °C for 5 min, the pellet was pipetted and sonicated again for 2 min. Finally, the tubes were vortexed for 10 s. After preparation, the fractions were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, and the antibodies are listed in method.

Recombinant ALDH2 enzyme assay

To evaluate inhibition of ALDH2 enzyme, we performed an assay using commercial recombinant ALDH2. The final concentration of recombinant ALDH2 was 2 µg/mL in all experiments. The assay buffer comprised 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) with 0.01% BSA.

Briefly, recombinant ALDH2 enzyme was preincubated with or without compounds for 30 min in 384-well black plates. The reaction was started by the addition of a final concentration of 2.5 mM NAD and 300 µM propionaldehyde. NADH production was monitored by fluorescence intensity (excitation, 340 nm; emission, 450 nm) with an Infinite 200 Pro plate reader (Tecan) every 2 min at room temperature. Changes in fluorescence intensity after 30 min were normalized to wells without compounds as 100% activity and without enzyme as 0% activity.

Data and analysis

Data are presented as mean and SD calculated from triplicates except for the average data of duplicate in Figs. 1D and 5A. Samples were tested for equal variance and the appropriate unpaired Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA was used to calculate statistical significance. Significant p values are described in each figure. Data analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.1) software. Statistical analysis was undertaken only for studies with a group size of at least n = 3.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Toshihiro Araki, Masaaki Sakurai, Mari Takamiya, Tsutomu Kamiyama, Yuki Inoue, and Yuki Watanabe for helpful advice and discussions. The authors thank Kazuaki Tokunaga (Nikon) and Miwako Iwai in Imaging Core Laboratory, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo for excellent technical assistance.

Author contributions

Ken Ohno: Methodology, Validation, Data analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, VisualizationHisashi Murakami: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Review & EditingNaohisa Ogo: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & EditingAkira Asai: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray, M. A. et al. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nat. Protoc.11, 1757 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.States, C. et al. Multiplex cytological profiling assay to measure diverse. PLoS One8, e8099 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohban, M. H. et al. Systematic morphological profiling of human gene and allele function via cell painting. Elife6, 24060 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray, M. A. et al. A dataset of images and morphological profiles of 30,000 small-molecule treatments using the Cell Painting assay. GigaScience6, 85. 10.1093/gigascience/giw014 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Singh, S. et al. Morphological profiles of RNAi-induced gene knockdown are highly reproducible but dominated by seed effects. PLoS One10, e131370 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbarzadeh, M. et al. Morphological profiling by means of the cell painting assay enables identification of tubulin-targeting compounds. Cell. Chem. Biol.29, 1053 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laraia, L. et al. Image-based morphological profiling identifies a lysosomotropic, iron-sequestering autophagy inhibitor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 5721 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schölermann, B. et al. Identification of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors using the cell painting assay. ChemBioChem23, e2022027 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohban, M. H. et al. Virtual screening for small-molecule pathway regulators by image-profile matching. Cell. Syst.13, 724 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deitrich, R. A. & Erwin, V. G. Mechanism of the inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase in vivo by disulfiram and diethyldithiocarbamate. Mol. Pharmacol.7, 301 (1971). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanz, J. et al. Disulfiram: mechanisms, applications, and challenges. Antibiotics12, 524. 10.3390/antibiotics12030524 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunnet, N. Oxidation of acetaldehyde by rat-liver mitochondria in relation to ethanol oxidation and the transport of reducing equivalents across the mitochondrial membrane. Eur. J. Biochem.35, 236 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marjanen, L. Intracellular localization of aldehyde dehydrogenase in rat liver. Biochem. J. 127(4), 633–639. 10.1042/bj1270633 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Eriksson, C. J., Marselos, M., & Koivula, T. Role of cytosolic rat liver aldehyde dehydrogenase in the oxidation of acetaldehyde during ethanol metabolism in vivo. Biochem. J. 152(3), 709–712. 10.1042/bj1520709 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hellström-Lindahl, E. & Weiner, H. Effects of disulfiram on the oxidation of benzaldehyde and acetaldehyde in rat liver. Biochem. Pharmacol. 34(9), 1529–1535. 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90695-1 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Cvek, B. The promiscuity of disulfiram in medicinal research. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00450 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spillier, Q. et al. Anti-alcohol abuse drug disulfiram inhibits human PHGDH via disruption of its active tetrameric form through a specific cysteine oxidation. Sci. Rep.9, 1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu, J. J. et al. FDA-approved disulfiram inhibits pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D pore formation. Nat. Immunol.21, 736 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, M. H. et al. Disulfiram can inhibit MERS and SARS coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antiviral Res.150, 155 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skrott, Z. et al. Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregase adaptor NPL4. Nature552, 7682 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song, J., Herrmann, J. M. & Becker, T. Quality control of the mitochondrial proteome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.22, 54. 10.1038/s41580-020-00300-2 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voos, W., Jaworek, W., Wilkening, A. & Bruderek, M. Protein quality control at the mitochondrion. Essays Biochem.60, 213 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scalettar, B. A., Abney, J. R. & Hackenbrock, C. R. Dynamics, structure, and function are coupled in the mitochondrial matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A88, 8057 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chrétien, D. et al. Mitochondria are physiologically maintained at close to 50°C. PLoS Biol.16, e2003962 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szczepanowska, K. & Trifunovic, A. Mitochondrial matrix proteases: quality control and beyond. FEBS J.289, 7128. 10.1111/febs.15964 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin, C. S. et al. LONP1 and mtHSP70 cooperate to promote mitochondrial protein folding. Nat. Commun.12, 1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng, A. C. H., Baird, S. D. & Screaton, R. A. Essential role of TID1 in maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential homogeneity and mitochondrial DNA integrity. Mol. Cell. Biol.34, 1427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, N., Maurizi, M. R., Emmert-Buck, L. & Gottesman, M. M. Synthesis, processing, and localization of human Lon protease. J. Biol. Chem.269, 29308 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havalová, H. et al. Mitochondrial HSP70 chaperone system-the influence of post-translational modifications and involvement in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 563. 10.3390/ijms22158077 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gale, M. et al. Acquired resistance to HER2-targeted therapies creates vulnerability to ATP synthase inhibition. Cancer Res.80, 524 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo, J. L. et al. The dynamics and turnover of tau aggregates in cultured cells: insights into therapies for tauopathies. J. Biol. Chem.291, 13175 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee, S., Chaturvedi, R., Singh, A. & Kushwaha, H. R. Putting human Tid-1 in context: an insight into its role in the cell and in different disease states. Cell. Commun. Signal.20, 1. 10.1186/s12964-022-00912-5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay, A., Yang, C. S., Wei, B. & Weiner, H. Precursor protein is readily degraded in mitochondrial matrix space if the leader is not processed by mitochondrial processing peptidase. J. Biol. Chem.282, 37266 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kita, Y. et al. Systematic chemical screening identifies disulfiram as a repurposed drug that enhances sensitivity to cisplatin in bladder cancer: a summary of preclinical studies. Br. J. Cancer121, 1027 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velasco-García, R., Zaldívar-Machorro, V. J., Mújica-Jiménez, C., González-Segura, L. & Muñoz-Clares, R. A. Disulfiram irreversibly aggregates betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase—a potential target for antimicrobial agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.341, 577 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González-Segura, L., Velasco-García, R. & Muñoz-Clares, R. A. Modulation of the reactivity of the essential cysteine residue of betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase fromPseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. J.361, 408 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall, S. B., Oh, J. Y., Diers, A. R. & Landar, A. Oxidative modification of proteins: an emerging mechanism of cell signaling. Front. Physiol.3, 53 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casey, J. R., Grinstein, S. & Orlowski, J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.11, 50. 10.1038/nrm2820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien, P. S. et al. Disulfiram (Antabuse) activates ROS-dependent ER stress and apoptosis in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Med.8, 611 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson, A. C. et al. Identification of novel activators of the metal responsive transcription factor (MTF-1) using a gene expression biomarker in a microarray compendium. Metallomics12, 1400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nadanaciva, S. et al. Assessment of drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction via altered cellular respiration and acidification measured in a 96-well platform. J. Bioenerg Biomembr.44, 421 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marroquin, L. D., Hynes, J., Dykens, J. A., Jamieson, J. D. & Will, Y. Circumventing the crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of hepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol. Sci.97, 539 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kioka, H. et al. Evaluation of intramitochondrial ATP levels identifies G0/G1 switch gene 2 as a positive regulator of oxidative phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.111, 273 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Depaoli, M. R. et al. Real-time imaging of mitochondrial ATP dynamics reveals the metabolic setting of single cells. Cell. Rep.25, 501 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel, A. et al. Biochemistry: ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356, 753 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rice, A. M. & Rosen, M. K. Cell biology: ATP controls the crowd. Science356, 701. 10.1126/science.aan4223 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schleyer, M., Schmidt, B. & Neupert, W. Requirement of a membrane potential for the posttranslational transfer of proteins into mitochondsria. Eur. J. Biochem.125, 109–116 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lister, R. et al. A Transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of the arabidopsis mitochondrial protein import apparatus and its response to mitochondrial dysfunction. Plant. Physiol.134, 777 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freundt, K. J. & Netz, H. Behavior of blood acetaldehyde in alcohol-treated rats following administration of thiurams. Arzneimittelforschung27, 105–108 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mays, D. C. et al. Inhibition of recombinant human mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase by two intermediate metabolites of disulfiram. Biochem. Pharmacol.55, 1099 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terashima, Y. et al. Targeting FROUNT with disulfiram suppresses macrophage accumulation and its tumor-promoting properties. Nat. Commun.11, 1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inoue, K., Fukunaga, M. & Yamasawa, K. Effects of disulfiram and its reduced metabolite, diethyl-dithiocarbamate on aldehyde dehydrogenase of human erythrocytes. Life Sci.30, 419–424 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johansson, B. A review of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of disulfiram and its metabolites. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.86, 15 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsubara, T. et al. A Comparative study on the effects of disulfiram and β-lactam antibiotics on the acetaldehyde-metabolizing system in rats. Jpn J. Pharmacol.42, 333 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faiman, M. D., Jensen, J. C. & Lacoursiere, R. B. Elimination kinetics of disulfiram in alcoholics after single and repeated doses. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.36, 520 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uhlen, M. et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1456 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bradford, B. U. & Rusyn, I. Swift increase in alcohol metabolism (SIAM): understanding the phenomenon of hypermetabolism in liver. Alcohol35, 133. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.12.001 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuki, T., Israel, Y. & Thurman, R. G. The swift increase in alcohol metabolism: inhibition by propylthiouracil. Biochem. Pharmacol.31, 2403–2407 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, Y. & Fernie, A. R. Metabolons, enzyme–enzyme assemblies that mediate substrate channeling, and their roles in plant metabolism. Plant. Commun.2, 100081. 10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100081 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piel, R. B., Dailey, H. A. & Medlock, A. E. The mitochondrial heme metabolon: insights into the complex(ity) of heme synthesis and distribution. Mol. Genet. Metabol. 128, 198. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.01.006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kharasch, E. D., Hankins, D. C., Jubert, C., Thummel, K. E. & Taraday, J. K. Lack of single-dose disulfiram effects on cytochrome P-450 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 activities: evidence for specificity toward P-450 2E1. Drug Metabol. Disposit.27, 198 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knockaert, L., Fromenty, B. & Robin, M. A. Mechanisms of mitochondrial targeting of cytochrome P450 2E1: physiopathological role in liver injury and obesity. FEBS J.278, 4252. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08357.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Gaetano, A. et al. Impaired mitochondrial morphology and functionality in LONP1WT/– mice. J. Clin. Med.9, 1763 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simonian, J., Haldar, D., Delmaestro, E. & Trombetta, L. D. Effect of disulfiram (DS) on mitochondria from rat hippocampus: metabolic compartmentation of DS neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Res.17, 1092 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wawer, M. J. et al. Toward performance-diverse small-molecule libraries for cell-based phenotypic screening using multiplexed high-dimensional profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.111, 569 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.