Abstract

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide with heterogeneous histopathological phenotypes. Although IgAN with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN)-like features has been reported in children and adults, treatment strategies for this rare IgAN subtype have not been established. Here, we present the case of a 56-year-old man with no history of kidney disease who initially presented with nephrotic syndrome. Renal biopsy revealed MPGN-like features with a negative serological workup for secondary causes. Immunofluorescent staining was predominantly positive for IgA in the glomerular mesangial and capillary walls. Galactose-deficient IgA1 staining showed a distribution pattern similar to IgA staining. Electron microscopy revealed disorganized structural deposits in the mesangial and subendothelial regions. Based on clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary IgAN. The nephrotic syndrome resolved completely after six months of combined corticosteroids and cyclosporine A (CsA) therapy. Although corticosteroids and CsA were tapered off, hematuria and proteinuria remained in complete remission for years of follow-up. This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing IgAN with MPGN-like features as a histopathological subtype that may benefit from intensive immunosuppressive therapy.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, Nephrotic syndrome, Corticosteroids, Cyclosporine A, Galactose-deficient IgA1

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerular disease characterized by focal and diffuse mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with deposition of IgA in the glomerular mesangium [1]. Although the typical histopathological appearance of IgAN observed using light microscopy is mesangial expansion and/or proliferation, IgAN is a histologically heterogeneous disease that can present with variable features ranging from mesangial proliferation to endocapillary and extracapillary hypercellularities [2, 3].

In IgAN, focal double contour or mesangial interposition of the glomerular capillary wall is occasionally identified on kidney biopsies [4, 5]. In some cases with IgAN, electron-dense deposits (EDDs) are observed in the subendothelium and/or subepithelium of the peripheral capillary walls of the glomeruli, accompanied by segmental duplication of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), showing membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN)-like features without prior exposure to infections, or other presumed causes of MPGN [6–10]. Currently, knowledge regarding the etiology and pathogenesis of the histopathological subtypes of IgAN with MPGN-like features, especially concerning treatment strategies, is limited.

Here, we describe a case of IgAN with MPGN-like features presenting with nephrotic syndrome without underlying diseases associated with MPGN. The patient responded well to combination therapy with corticosteroids and cyclosporine A (CsA) and achieved long-term clinical remission.

Case report

A 56-year-old Japanese man was referred to our hospital with edema of both lower extremities, accompanied by moderate hematuria and severe proteinuria. The patient gained 4.0 kg within one month. The patient had no recent history of infection, arthralgia, or medication use. No urinary abnormalities were noted during an annual physical examination 2 years earlier. He had a medical history of Meniere’s disease, hyperlipidemia, and tonsillectomy for recurrent childhood tonsillitis. He had no significant family history.

On admission, physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 134/67 mmHg, pulse of 70/min, temperature of 36.7 °C, and lower leg edema without palpable purpura. Examination of the lungs, heart, abdomen, and nervous system revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 10,300/μL (neutrophils 7,300/μL, lymphocytes 2,500/μL, monocytes 500/μL, eosinophils 100/μL, and basophils 100/μL), a hemoglobin level of 15.4 g/dL, and a platelet count of 318,000/μL. Blood chemistry and serology were as follows: total protein, 4.8 g/dL; albumin, 2.2 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 15 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.00 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, 213 mg/dL; IgG, 327 mg/dL; IgA, 353 mg/dL; IgM, 92 mg/dL; complement 3 (C3), 122 mg/dL; complement 4 (C4), 34 mg/dL; total hemolytic complement, 67.9 U/mL; antistreptolysin (ASO), 272 U/ml; antistreptokinase (ASK), 320 U/mL; C-reactive protein, 0.19 mg/dL; and hemoglobin A1c, 5.8%. Antinuclear antibody, myeloperoxidase or proteinase 3, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and anti-GBM antibody tests were negative. The patient tested negative for the hepatitis B virus surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies. Serum cryoglobulin levels were negative. Immunoelectrophoresis of the serum and urine samples showed no monoclonal bands. Spot urinalysis revealed a protein-to-creatinine ratio of 8.08 g/gCr. Urine sediment showed 20–29 red cells/high-power field and > 80% dysmorphic erythrocytes. The selectivity index was 0.20. The 24 h creatinine clearance was 67 mL/min, and urinary protein excretion was 7.36 g/24 h. Computed tomography revealed normal kidney size and no evidence of pleural effusion or ascites.

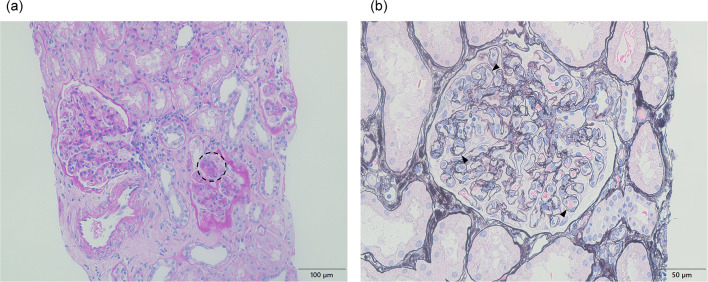

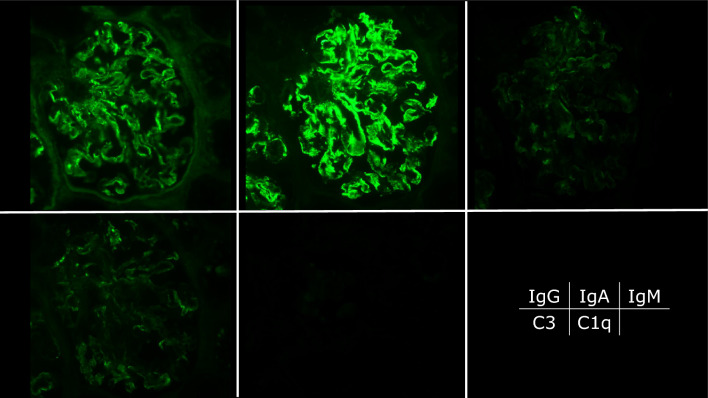

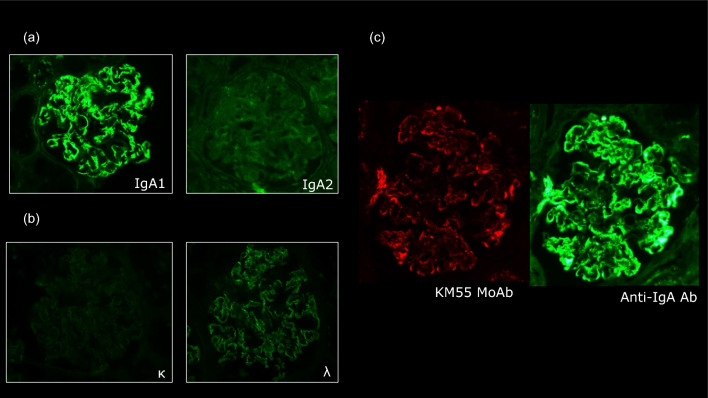

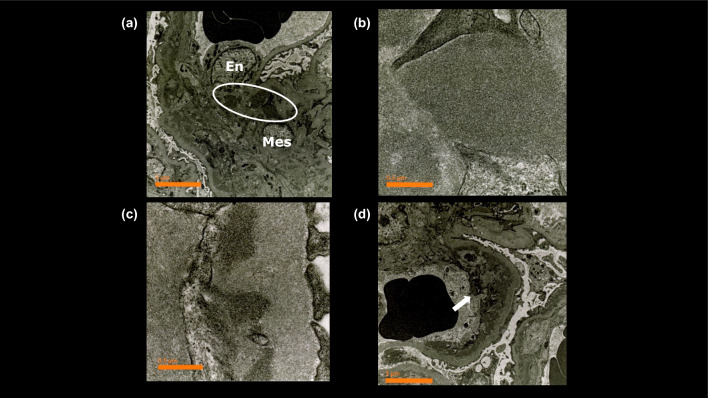

A renal biopsy was performed 2 days after admission to evaluate the cause of nephrotic syndrome. The light microscopic section revealed 29 glomeruli, with four showing global glomerulosclerosis (14%). The remainder showed mesangial and endocapillary proliferation with occasional lobular structures (Fig. 1a). The glomerular capillary walls were thickened, forming double contour features (Fig. 1b). These findings were consistent with those of MPGN. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy with lymphocytic infiltration were observed in approximately 10% of the renal biopsy specimens. The interlobular arteries showed only mild atherosclerosis, with no hyalinosis of the periglomerular arterioles. Immunofluorescence revealed focal and segmental IgA deposits predominantly in the glomerular mesangial and capillary walls. IgG, IgM, and C3 staining were identified mainly in the glomerular capillary walls, whereas glomerular C1q staining was negative (Fig. 2). The IgA deposited in the glomeruli predominantly belonged to the IgA1 subclass (Fig. 3a). The intensity of immunostaining for lambda light chains exceeded that for kappa light chains (Fig. 3b). Galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) using KM55 staining [11] was observed mainly in the capillary regions, with a staining intensity and distribution similar to those of IgA (Fig. 3c). Electron microscopy revealed disorganized mesangial and subendothelial deposits (Fig. 4a-b) with mesangial interposition in the GBM (Fig. 4c). Podocyte foot process effacement was observed in 20% of all areas identified in the specimen. No subepithelial deposits or electric humps were observed. Based on these histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with IgAN, presenting with MPGN-like features and subendothelial deposits. The Oxford International Classification score was M1S0E1T0C0. According to the risk classification in the 3rd edition of the IgA Nephropathy Treatment Guideline in Japan, the clinical severity was C grade II, the histological severity was H-Grade I, and the risk of introducing dialysis was medium [12].

Fig. 1.

Histopathological findings of renal biopsy. a Light microscopy showed moderate diffuse mesangial and endocapillary proliferation with occasional lobular structures (circle) (periodic acid-Schiff stain, × 200). b The capillary walls showed thickness forming features of double contour (arrow heads) (periodic acid methenamine silver stain, × 400)

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence study. Immunofluorescence staining was positive for immunoglobulin (IgA), predominantly in the mesangium and capillary walls. IgG was positive and C3 was weakly positive in the capillary walls (fluorescein isothiocyanate anti-human IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q × 400)

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence study. a An immunofluorescence study of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) subtype (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] anti-human IgA1, IgA2, × 400). IgA1 was predominantly positive in the mesangium and capillary walls. b An immunofluorescence study of the light chain (FITC anti-human kappa, lambda, × 400). Lambda was predominantly positive in the mesangium and capillary walls. c An immunofluorescence study using KM55, specifically recognizing galactose-deficient IgA (Gd-IgA). Gd-IgA1, detected by the KM55 mAb, exhibited localization patterns similar to IgA

Fig. 4.

Electron microscopy findings. a Electron microscopic examination shows localization of immune-type electron-dense deposits (circle) in the mesangial region (× 6,000). b The electron-dense deposits were disorganized structures (× 60,000). c Ultrastructural examination of this capillary wall showed subendothelial deposits (× 60,000). d The white arrow indicated circumferential mesangial interposition in the glomerular basement membrane (× 6,000). En endothelial cell, Mes mesangial cell

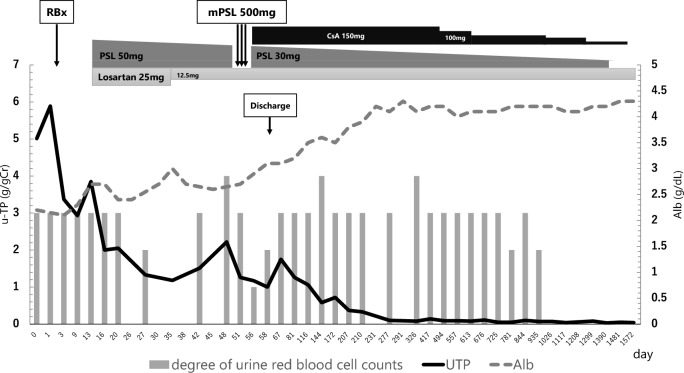

The clinical course of the patient is shown in Fig. 5. Oral corticosteroid therapy was started at a dose of 0.8 mg/kg/day on day 13, along with losartan potassium at a dose of 25 mg, according to both the nephrotic syndrome and IgAN treatment guidelines in Japan [12, 13]. After corticosteroid administration, urinary protein excretion decreased from 7.36 to 3.43 g/24 h within 4 weeks. On day 51 after admission, methylprednisolone pulse therapy was administered, followed by a combination of oral corticosteroids and CsA because of persistent heavy proteinuria suggestive of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. CsA was administered once daily before breakfast, with blood levels monitored at 2 h post-dose (C2 levels) and maintained within the range of 500–700 ng/mL [14, 15]. After these treatments, urinary protein excretion gradually decreased. Upon discharge from the hospital, the corticosteroid and CsA doses were tapered without a recurrence of nephrotic syndrome in our outpatient department. Complete remission was achieved 9 months after treatment initiation. The patient was followed up for 50 months after discharge and is currently off medication. He has remained healthy with normal kidney function and complete remission of hematuria and proteinuria.

Fig. 5.

Patient’s clinical course. The figure shows a comprehensive picture of the patient’s clinical course, tracking urinary total protein (UTP) (g/gCr), serum albumin (Alb) level (g/dL), urine red blood cell count (gray column, scale; 0–4), and treatment regimen. At the initial presentation, the patient presented with marked proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia. Simultaneously, microscopic hematuria was intermittently positive. A renal biopsy (RBx) was performed 2 days after admission. High-dose prednisolone (PSL) was started, including pulse therapy, and the UTP levels gradually decreased. Cyclosporine A (CsA) therapy was subsequently initiated, leading to a gradual reduction in PSL dosage and further improvement in UTP levels. Nine months after admission, complete remission was observed

Discussion

Here, we report a case of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis with histopathological features of MPGN presenting with nephrotic syndrome. In this case, no clinical or serological evidence of infection or systemic disease was detected. Thus, the patient received a diagnosis of primary IgAN with MPGN-like features based on a comprehensive evaluation of clinical and histopathological findings, including immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. Treatment with a combination of corticosteroids and CsA resulted in complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome and a favorable long-term clinical course.

MPGN is a pattern of glomerular injury characterized by diffuse global endocapillary proliferation with an increased mesangial matrix and thickened capillary walls. In general, MPGN presents as a chronic, slowly progressive disease in most patients, sometimes as acute nephritic syndrome and/or nephrotic syndrome with hypocomplementemia [16]. MPGN without a background disease is more common in children, whereas adult MPGN is more commonly associated with chronic infections, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and bacterial endocarditis. Approximately 80% of adult MPGN cases are secondary to hepatitis C and may be associated with circulating cryoglobulins [17]. Recent insights into the dysregulation of the alternative pathway of the complement system have identified novel pathogenesis of MPGN subtypes, such as dense deposition disease and C3 glomerulonephritis [18]. Recently, IgA-dominant MPGN without any background disease has been described, and a multicenter study proposed that IgA-dominant MPGN is clinically and histopathologically distinct from primary IgAN with MPGN-like features [19, 20]. This IgA-dominant “idiopathic” MPGN is morphologically different from primary IgAN or IgA-dominant acute post-infectious glomerulonephritis in that IgA-dominant MPGN refers to diffuse MPGN features with prominent subendothelial deposits, with no mesangial deposits.

The characteristic finding of primary IgAN that may distinguish this case from IgA-dominant MPGN is the positive staining of Gd-IgA1 with KM55 in the glomerular mesangium and capillary walls [21]. KM55 has been shown to specifically recognize Gd-IgA1-associated immune complexes [22]. Gd-IgA1 is characterized by an abnormal glycosylation pattern, in which the hinge region of the IgA1 molecule lacks specific galactose residues. This under-galactosylation leads to the formation of autoantibodies against Gd-IgA1, facilitating the deposition of immune complexes in the glomerular mesangium. Thus, the finding of positive Gd-IgA1 immunostaining additionally confirmed that the present case was primary IgAN with MPGN-like features.

Primary IgAN with MPGN-like features has been reported in children [9, 23, 24]. Kurosu et al. hypothesized that the presumed histological immaturity of GBM in children may cause mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis to easily progress to mesangial interposition and endocapillary hypercellularity, manifesting as MPGN-like lesions [23]. However, solely attributing the heightened susceptibility to adult-onset IgAN with MPGN-like features to GBM immaturity is challenging to justify. Recent studies have reported that Gd-IgA1-containing immune complexes have a high affinity for glomerular endothelial cells and simultaneously promote the expression of adhesion molecules in glomerular mesangial cells [25, 26]. These findings suggest that exposure of Gd-IgA1-containing immuno-complex to the glomerular endothelium may be a key factor in establishing IgAN. Conversely, another IgAN subtype with predominant subepithelial IgA deposits with MPGN-like features has been reported [27, 28]; however, in our case, subepithelial deposits, including electric humps, were not evident. Considering the histopathological subtypes of IgAN represented by different distributions of IgA deposits, further studies on the factors that define differences in the affinity and kinetics of Gd-IgA1 deposits within the glomerulus are required.

A treatment strategy for IgAN with MPGN-like features has not yet been established, as only a few studies have discussed the treatment options for patients presenting with this subtype. Several studies have advocated the administration of high-dose corticosteroids for treating IgAN associated with severe proteinuria [29, 30]. Alternative approaches include monthly intravenous pulse doses of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide (CTX) for 6 months [31]. Furthermore, although IgAN presenting with nephrotic syndrome often shows resistance to corticosteroid therapy, treatment with CsA is effective in several cases, including pediatric patients with IgAN and MPGN-like features [32, 33]. A recent study compared the efficacy and safety of corticosteroids combined with CTX versus corticosteroids alone for treating IgAN in patients with nephrotic syndrome. The study concluded that the combination of corticosteroids and CTX is more effective in reducing urinary protein levels than corticosteroids alone [34]. In our case, adding CsA to corticosteroids resulted in rapid proteinuria reduction, complete remission without side effects or relapse, and a good clinical course allowing medication discontinuation. Our case of successful additional CsA treatment provides additional clues for treating patients with IgAN with nephrotic syndrome.

In summary, we encountered a rare case of primary IgAN histopathologically showing MPGN-like features without evidence of background diseases associated with MPGN. Notably, the patient was initially refractory to corticosteroid therapy; however, additional therapy with CsA was successful, suggesting the efficacy of multidisciplinary induction therapy in achieving clinical remission. Further studies are required to elucidate the pathogenesis and establish effective therapeutic strategies for IgAN showing MPGN-like features.

Acknowledgements

We thank our patient for allowing us to publish this case report.

Author contributions

GK, KK, NM, and YM treated patients. SH, GK, KK, HU, and NT performed histopathological analyses of the kidney biopsies. SH, GK, and NT wrote the manuscript. KK, HU, NM, and YM corrected the manuscript. TY supervised the study. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent to use all personal data and images from the renal biopsy. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this report and associated images.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berger J, Hinglais N. Les ddpôts intercapillaires d’IgA-IgG [Intercapillary deposits of IgA-IgG]. J Urol Nephrol (Paris). 1968;74:694–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas M. Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: a clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:829–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, Alpers CE. AJKD Atlas of Renal Pathology: IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:e33–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda Y, Yamanaka N, Ishikawa A, Kataoka M, Arai T, Wakamatsu K, Kuwahara N, Nagahama K, Ichikawa K, Shimizu A. Glomerular basement membrane injuries in IgA nephropathy evaluated by double immunostaining for α5(IV) and α2(IV) chains of type IV collagen and low-vacuum scanning electron microscopy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamoto Y, Yasuda T, Imai H, Miura AB. Circumferential mesangial interposition: a form of mesangiolysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1992;7:373–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hara M, Endo Y, Nihei H, Hara S, Fukushima O, Mimura N. IgA nephropathy with subendothelial deposits. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;386:249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshikawa N, Ito H, Nakahara C, Yoshiara S, Yoshiya K, Matsuo T, Hasegawa O, Hazikano H, Okada S. Glomerular electron-dense deposits in childhood IgA nephropathy. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1985;406:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emancipator SN. IgA nephropathy: morphologic expression and pathogenesis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:451–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iitaka K, Yamamoto A, Ogawa N, Sekine T, Tamai S, Motoyama O. IgA-associated glomerulonephritis with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis-like pattern in two children. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2003;7:284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Wang H, Yang D. IgA Nephropathy with Pathologic Features of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis following Burn Injury. Case Rep Nephrol Urol. 2014;4:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H, Yasutake J, Makita Y, Tanbo Y, Yamasaki K, Sofue T, Kano T, Suzuki Y. IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis with nephritis have a shared feature involving galactose-deficient IgA1-oriented pathogenesis. Kidney Int. 2018;93:700–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuzaki K, Suzuki H, Kikuchi M, Koike K, Komatsu H, Takahashi K, Narita I, Okada H, Committee of Clinical Practical Guideline for IgA Nephropathy. Current treatment status of IgA nephropathy in Japan: a questionnaire survey. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;2023(27):1032–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada T, Ishimoto T, Nakaya I, Kawaguchi T, Sofue T, Shimizu S, Kurita N, Sasaki S, Nishiwaki H, Koizumi M, Saito S, Nishibori N, Oe Y, Yoshida M, Miyaoka Y, Akiyama S, Itano Y, Okazaki M, Ozeki T, Ichikawa D, Oguchi H, Kohsaka S, Kosaka S, Kataoka Y, Shima H, Shirai S, Sugiyama K, Suzuki T, Son D, Tanaka T, Nango E, Niihata K, Nishijima Y, Nozu K, Hasegawa M, Miyata R, Yazawa M, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto R, Shibagaki Y, Furuichi K, Okada H, Narita I. A digest of the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for nephrotic syndrome 2020. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2021;25:1277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattran DC, Alexopoulos E, Heering P, Hoyer PF, Johnston A, Meyrier A, Ponticelli C, Saito T, Choukroun G, Nachman P, Praga M, Yoshikawa N. Cyclosporin in idiopathic glomerular disease associated with the nephrotic syndrome : workshop recommendations. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1429–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iijima K, Sako M, Oba MS, Ito S, Hataya H, Tanaka R, Ohwada Y, Kamei K, Ishikura K, Yata N, Nozu K, Honda M, Nakamura H, Nagata M, Ohashi Y, Nakanishi K, Yoshikawa N; Japanese Study Group of Kidney Disease in Children. Cyclosporine C2 monitoring for the treatment of frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome in children: a multicenter randomized phase II trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakopoulou L. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(Suppl 6):71–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Yamabe H, Hart J, Bacchi CE, Hartwell P, Couser WG, Corey L, Wener MH, Alpers CE. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis–a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrario G, Palazzi P, Torri Tarelli L, Volpi A, Meroni M, Giordano F, Sessa A. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with IgA deposits in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Pathologica. 1986;78:469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andeen NK, Jefferson JA, Akilesh S, Alpers CE, Bissonnette ML, Finn LS, Higgins J, Houghton DC, Kambham N, Magil A, Najafian B, Nicosia RF, Troxell ML, Smith KD. IgA-dominant glomerulonephritis with a membranoproliferative pattern of injury. Hum Pathol. 2018;81:272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada Y, Matsumoto K, Suzuki T, Saito T, Kanazawa N, Tachibana S, Iseri K, Sugiyama M, Iyoda M, Shibata T. Clinical significance of serum and mesangial galactose-deficient IgA1 in patients with IgA nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0206865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishiko S, Horinouchi T, Fujimaru R, Shima Y, Kaito H, Tanaka R, Ishimori S, Kondo A, Nagai S, Aoto Y, Sakakibara N, Nagano C, Yamamura T, Yoshimura M, Nakanishi K, Fujimura J, Kamiyoshi N, Nagase H, Yoshikawa N, Iijima K, Nozu K. Glomerular galactose-deficient IgA1 expression analysis in pediatric patients with glomerular diseases. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurosu A, Oka N, Hamaguchi T, Yoshikawa N, Joh K. Infantile immunoglobulin A nephropathy showing features of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:253–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Utsunomiya Y, Kado T, Koda T, Okada S, Hayashi A, Fukawaza A, Nakagawa T, Kanzaki S, Kasagi T. Features of IgA nephropathy in preschool children. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54:443–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaji K, Suzuki Y, Suzuki H, Satake K, Horikoshi S, Novak J, Tomino Y. The kinetics of glomerular deposition of nephritogenic IgA. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e113005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makita Y, Suzuki H, Nakano D, Yanagawa H, Kano T, Novak J, Nishiyama A, Suzuki Y. Glomerular deposition of galactose-deficient IgA1-containing immune complexes via glomerular endothelial cell injuries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:1629–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura M, Kida H, Abe T, Takeda S, Katagiri M, Hattori N. Significance of IgA deposits on the glomerular capillary walls in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9:404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamura M, Obata Y, Ota Y, Muta K, Yamashita H, Harada T, Mukae H, Nishino T. Significance of subepithelial deposits in patients diagnosed with IgA nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0211812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katafuchi R, Ikeda K, Mizumasa T, Tanaka H, Ando T, Yanase T, Masutani K, Kubo M, Fujimi S. Controlled, prospective trial of steroid treatment in IgA nephropathy: a limitation of low-dose prednisolone therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:972–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagasawa Y, Yamamoto R, Shinzawa M, Shoji T, Hasuike Y, Nagatoya K, Yamauchi A, Hayashi T, Kuragano T, Moriyama T, Isaka Y. Efficacy of corticosteroid therapy for IgA nephropathy patients stratified by kidney function and proteinuria. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24:927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coppo R, Amore A. New perspectives in treatment of glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Xu X, Fang Y, Ji J, Zhang X, Yuan M, Liu C, Ding X. Comparison of glucocorticoids alone and combined with cyclosporine A in patients with IgA nephropathy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Intern Med. 2014;53:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ihm HS, Lee JY, Hwang HS, Kim YG, Moon JY, Lee SH, Jeong KH, Lee TW, Ihm CG. Combination therapy of low-dose cyclosporine and steroid in adults with IgA nephropathy. Clin Nephrol. 2019;92:131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du W, Chen Z, Fang Z, Li J, Weng Q, Zheng Q, Xie L, Yu H, Gu X, Shi H, Wang Z, Ren H, Wang W, Ouyang Y, Xie J. Oral glucocorticoids with intravenous cyclophosphamide or oral glucocorticoids alone in the treatment of IgA nephropathy present with nephrotic syndrome and mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16:2567–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

None.