Abstract

Astrocytes, characterized by complex spongiform morphology, participate in various physiological processes, and abnormal changes in their calcium (Ca2+) signaling are implicated in central nervous system disorders. However, medications targeting the control of Ca2+ have fallen short of the anticipated therapeutic outcomes in clinical applications. This underscores the fact that our comprehension of this intricate regulation of calcium ions remains considerably incomplete. In recent years, with the advancement of Ca2+ labeling, imaging, and analysis techniques, Ca2+ signals have been found to exhibit high specificity at different spatial locations within the intricate structure of astrocytes. This has ushered the study of Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes into a new phase, leading to several groundbreaking research achievements. Despite this, the comprehensive understanding of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and their implications remains challenging area for future research.

Keywords: Astrocyte, Ca2+ signaling, Central nervous system, Synapse, Ion channel

Deciphering Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes is crucial for understanding the functional roles of the glial cells. A growing body of evidence suggests that astrocytic Ca2+ signaling contributes to a variety of astrocytic functions, including modulation of cerebral blood flow, synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and gliotransmitter release [1]. In this context, our attention is dedicated to advancing our understanding of astrocytic Ca2+ events. Collectively, these advancements promise to yield fresh insights into the mechanisms through which astrocytes regulate the brain function and how changes in astrocytic Ca2+ signals influence physiological and pathological processes.

1. Astrocyte morphology

The types of glial cells in the central nervous system (CNS) include microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocyte precursors [2], [3], [4]. Astrocytes were first described by Rudolf Virchow in the 19th century. Decades later, researchers used the silver chromate staining technique to visualize the morphology of astrocytes, advancing the view that astrocytes act as a “glue” in the CNS [5]. These abundant and morphologically complex cells in mammalian brain are distributed in a lattice-like pattern [6,7], forming a dense network in which other glial cells, blood vessels, and neurons are embedded [6], [7], [8], [9], [10].

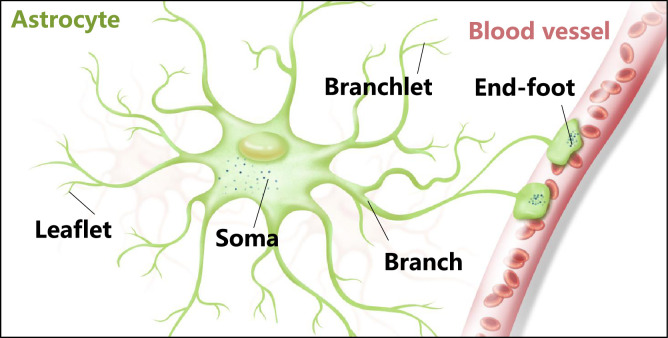

Astrocytes exhibit complex spongiform shapes, with volumes of approximately ∼6.6 × 104 µm and diameters ranging from ∼40 to 60 µm [11], [12], [13], [14]. The fine structure of astrocytes, particularly protoplasmic astrocytes in the gray matter, consists of a soma, several major branches, numerous branchlets, leaflets, and end-feet (Fig. 1) [15]. Branches, the major processes emanating from the soma, have diameters in the micrometer range. Secondary to tertiary processes, branchlets have diameters in the sub-micrometer range. Leaflets, the terminal extensions of branchlets, show close contacts with synapses, while end-feet are distal extensions that contact blood vessels. Perisynaptic astrocyte processes (PAPs), a morphologically distinct leaflets adjacent to a synapse, affect information processing by the nerve circuits and the behaviours which rely on it [16,17]. However, emerging evidence has suggested that the morphology of astrocytes varies under different conditions. For instance, the phenotypes of reactive astrocytes show an increased number of processes and a denser morphology with altered soma volume compared to resting astrocytes [18].

Fig. 1.

Astrocytes present a complex morphological appearance. Schematic representation of the astrocyte structure.

As a heterogeneous population of cells, astrocytes vary in morphological appearance [19]. Generally, protoplasmic astrocytes are one of the major types found in grey matter, whereas fibrous astrocytes are found in white matter [20], [21], [22]. An increasing number of studies have shown that astrocytes exhibit morphological deficits that may contribute to the progression of CNS disease [7,14]. For instance, at the onset of Alzheimer's disease (AD), progressive atrophy of astrocytes with decreased GFAP expression was observed in the hippocampus and cortex [23], [24], [25]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that the morphological changes of astrocytes in the substantia nigra pars compacta exhibited GFAP-astrogliosis in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD). These findings imply that astrogloiosis dysfunction is likely to be fundamental to dissecting the cellular mechanisms underlying CNS disease [26], [27], [28]. In summary, the study of astrocytes with varying morphologies has garnered increased attention due to their important contribution to the CNS.

2. Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes

Calcium (Ca2+) is a crucial intracellular second messenger for the survival and fate of organisms [29,30]. The Ca2+ signaling system comprises numerous types of proteins, including channels, pumps, receptors, exchangers, and sensors, several of which are altered in expression or mutated in various diseases [31]. For example, excessive inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3)/Ca2+ signaling contribute to the excitatory-inhibitory imbalance of neurons in bipolar disorder [32,33]. Notably, researchers have studied Ca2+ signaling in various cell types and model organisms to understand its physiological and pathological roles [34]. In the CNS, Ca2+ serves as a pivotal component in intracellular signaling, facilitating communication within both glial cells and neurons. Its role is integral to the maintenance of brain homeostasis [35].

It is well known that astrocytes are electrically non-excitable glial cells and Ca2+ fluctuations have been detected in astrocytes under physiological and pathological conditions [36], [37], [38]. Spatially, Ca2+ signaling potentially propagates to neighbouring cells via astrocytic gap junctions [39,40]. This Ca2+ wave propagation has been thoroughly proven in vitro systems. Instead of wave propagation, synchronized Ca2+ activities of many astrocytes have been detected in awake and naturally sleeping animals in response to different behavioral stimuli [41]. Within a single astrocyte, Ca2+ events in different cellular compartments also have different functional roles, and several studies have provided evidence for the diversity of Ca2+ signals [15,42].

Analyzing Ca2+ in the astrocytic soma is relatively straightforward due to its distinct identification in the soma region. Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes is frequent and short in the distal processes, but relatively rare and large in the soma [43]. Furthermore, Ca2+ signaling induced by the hypoosmotic test was detected in most compartments of astrocytes except the soma, indicating that the astrocytic soma does not respond to the hypoosmotic test. Interestingly, under selected experimental conditions, Ca2+ signals can still be detected in astrocytes at the soma. Thrane et al. reported that the astrocytic soma responded to osmotic swelling, in terms of Ca2+ spikes both in vivo and in vitro [44]. The mouse pups used in this study may explain why the somatic Ca2+ response occurred, demonstrating that Ca2+ signaling at the soma relied on developmentally regulated autocrine signaling pathways. Age is likely to be an important factor regulating somatic Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes. Moreover, Duffy et al. showed that osmotically induced Ca2+ responses at the soma occur in the late phase of brain swelling [44]. Furthermore, another study supported the idea that astrocytes exhibited an increase in Ca2+, mediated by voltage-dependent influx and released from internal stores in response to ischemia [45].

Notably, most Ca2+ activity in astrocytes is spatially restricted to microdomains, occurring in fine processes that form a complex meshwork [46]. These localized Ca2+ signals were observed to occur more frequently than somatic Ca2+ elevations and were firstly described as microdomains in the processes of Bergmann glia [47]. Researchers demonstrated that these astrocyte Ca2+ signals were frequently far removed from the soma, such as in branches, branchlets, and end-feet [9,[48], [49], [50]]. Ca2+ released from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) store in an inositol triphosphate receptor 2 (IP3R2)-dependent manner is one of the important sources of Ca2+ microdomain signals [50]. Microdomain activity, which occurs in the absence of IP3-dependent release from the endoplasmic reticulum, is mediated by Ca2+ efflux from the mitochondria during brief openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [9]. The Ca2+ influx-dependent events are also detected in the fine processes of adult hippocampal astrocytes [51]. Many studies have focused on understanding the Ca2+ events at microdomains [1,52,53]. For instance, a fraction of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling is caused by spontaneous and action potential–dependent synaptic activity [54]. Microdomain Ca2+ signal has been detected in end-feet, mediated by Ca2+ entry via TRPV4 channels and Ca2+ release from IP3R2-dependent stores [55,56]. Finally, another type of Ca2+ signaling occurs during startle responses and locomotion, and is driven by the volumetric release of neuromodulators [57,58].

3. Genesis of astrocytic Ca2+ events

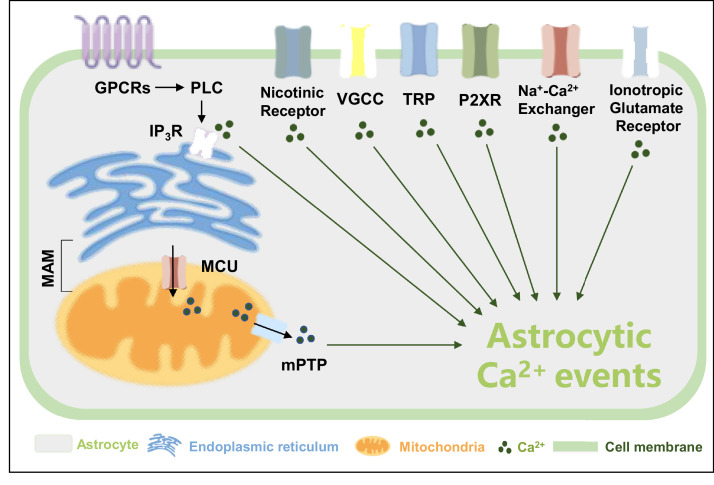

Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling is regulated by multiple mechanisms, although these remain to be fully elucidated [59]. To date, numerous studies have shown that astrocytic Ca2+ signaling depended not only on intracellular Ca2+resources, but also on extracellular transmembrane Ca2+ influxes, as shown in Fig. 2. The sources of Ca2+ also show spatio-temporal characteristics. For instance, transients in the soma of astrocytes rely on the coordination between the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores and extracellular influxes. However, some of the events in fine processes can be solely generated by Ca2+ influxes [51].

Fig. 2.

Different Ca2+ channels exist in the cell and organelle membranes. Ca2+ channels are expressed on both the plasma membrane and the membrane of organelles, as discussed in this review. GPCRs: G-protein coupled metabotropic receptors, PLC: phospholipase C, IP3R: inositol triphosphate receptor, MAM: mitochondria-associated ER membranes, MCU: mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, mPTP: mitochondrial permeability transition pore, VGCC: voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, TRP: transient receptor potential channels, P2XR: P2X receptors.

3.1. Intracellular Ca2+ source

The regulated release of Ca2+ from the internal stores of the ER or mitochondria is one of the major mechanisms contributing to astrocytic Ca2+ events. Among them, astrocytic Gq-G protein-coupled metabotropic receptor (GPCR)-linked IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signaling is the most extensively studied molecular mechanism of Ca2+ signals, which has been investigated in an IP3R2 knockout mouse [19,50,[60], [61], [62], [63], [64]]. Nagai et al. reported that mice lacking intracellular IP3R2s showed downregulation of spontaneous and GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling [64]. Notably, astrocytic Ca2+ events in the soma are reduced by silencing IP3R2 in the ER. However, both the proportion of fast-onset microdomain Ca2+ events evoked by nearby synaptic activity and the Ca2+ responses in fine processes to sensory stimulation are unaffected [50,60,65]. Nevertheless, IP3R2 is unlikely to be the only type of receptor mediating Ca2+ release from the ER in astrocytes. Okubo et al. recently re-evaluated the assumption that Ca2+ release from the ER was abolished in IP3R2-KO astrocytes using a highly sensitive imaging technique and demonstrated that IP3R2-independent Ca2+ release induced small cytosolic Ca2+ elevations but robust Ca2+ transients in the mitochondria [66]. Accordingly, in IP3R2-KO mice, ryanodine and IP3R1/3 receptors may facilitate IP3R2-independent Ca2+ release [67,68].

Mitochondria are another key player in the astrocytic Ca2+ microdomain, acting as a single electrically coupled continuum or as multiple separate organelles to modulate Ca2+ signals [69]. Recently, the Bergles laboratory demonstrated that mitochondria were critical for the Ca2+ activities in astrocytic microdomains and were used to store Ca2+, which can influence signals by buffering receptor-induced Ca2+ transients. In this study, scientists have shown that spatially restricted Ca2+ events in astrocytic processes, which occurred independently of ER Ca2+ release, were caused by Ca2+ efflux from mitochondria in response to the transient opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [9]. Moreover, studies indicated that opening of the mPTP maintained the levels of mitochondrial Ca2+. Reversible mPTP opening-dependent ROS release is an adaptive housekeeping function of mitochondria to avoid potentially toxic levels of ROS (and Ca2+) [70]. Agarwal et al. showed that inhibiting the function of astrocytic mPTP or disrupting the mitochondrial membrane potential markedly reduced Ca2+ events in the microdomain, whereas increasing mPTP opening increased Ca2+ transients [9]. Collectively, these studies showed that opening of mPTP was the cause of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in astrocytes lacking IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis is also achieved by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), mitochondrial H+-Ca2+ exchangers, and Na+-Ca2+ exchangers [71].

Interestingly, functional coupling also exists between mitochondria and ER Ca2+ stores in astrocytes. The ER and mitochondria are frequently in close proximity and have been shown to form mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) that promote the exchange of metabolites and ions [72]. This specialized junction may synergistically promote Ca2+ release. In PD, the interface of the ER–mitochondria was disrupted, leading to abnormal ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfers in patients with PD and Parkin knockout mice with Parkin mutations [73]. Parkinson's disease protein 7 (Park7/DJ-1) which is another PD-related protein closely related to MAMs has also been implicated in Ca2+ events and upregulating DJ-1 prevents these alterations by re-establishing the ER-mitochondria tethering [74,75]. Liu et al. identified DJ-1 as a key component of the IP3R–Grp75–VDAC1 complex, the loss of which resulted in decrease in mitochondrial Ca2+ upon IP3R stimulation [75]. In AD, exposure of neurons to Aβ triggered the upregulation of MAM-associated proteins and increased ER–mitochondrial contact sites [76]. Moreover, MAM-localized Ca2+ signals have been implicated in the pathogenesis of other diseases and warrants further investigation [72].

3.2. Extracellular Ca2+ influx

Numerous studies have suggested that Ca2+ activity in astrocytes also depended on extracellular Ca2+ sources. In particular, astrocytes exhibited Ca2+ events close to the membrane [49,77]. Genetic and pharmacological evaluations have shown that extracellular Ca2+ influx in astrocytes occurred through transient receptor potential cation channel A1 (TRPA1) and others (e.g., TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPV1, TRPV4 and TRPC1) [55,[77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84]]. Importantly, the studies conducted by Freeman's group on TPR channels contributing to microdomain Ca2+ signals deserve attention. They demonstrated that astrocytic Ca2+ events mediated by different TRP channels were indispensable for multiple sensory-driven behaviors as well as the regulation of CNS gas exchange [85,86]. However, despite the dedication of numerous scientists to the investigation of these receptors, the molecular basis of this process has not been systematically elucidated. Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes in different brain regions may be mediated by different sources.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) are ligand-gated ion channels that can be divided into three types (NMDA receptor, AMPA receptor, and Kainate receptor). iGluRs are also essential mediators of astrocytic Ca2+ influx [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. Porter et al. demonstrated that hippocampal astrocytes responded to the neuronal release of the neurotransmitter glutamate by increasing in Ca2+ through iGluRs [92]. Similarly, NMDA triggered local increases in astrocytic Ca2+ in the mouse neocortex via functional NMDA receptors [93].

The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, also known as “NCX,” exchanges the Ca2+ and Na+in the astrocytes. Multitudinous researches have attempted to model the function of NCX in astrocytic Ca2+ microdomain events, which revealed a novel form of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling [94], [95], [96].

P2X receptors, which are thought to contain seven subunits, are ion channels that open in response to the binding of extracellular ATP in astrocytes from the hippocampus, cortex, spinal cord, cerebellum, brain stem, and retina [19,[97], [98], [99]]. P2×1/5 and P2×7 are the major subunits associated with Ca2+ signals. Rat cortical astrocytes have been reported to express ligand-gated P2X (i.e., P2×1-P2×5 and P2×7) for all clones except the P2×6 receptor [88,100]. In addition to the cortex, P2×7 receptors were found to be expressed in the hippocampus and retina [101,102].

Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels (VGCC), documented at the molecular level, are classified as Cav1.1–1.4 or L-type Ca2+ channels, Cav2.1–2.3 or P/Q/N/R-type channels, and Cav3.1–3.3 or T-type Ca2+ channels [19,103]. Previous studies have found Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels in rodent cortical astrocytes, while VGCCs subtypes of α1B (N-type), α1C (L-type), α1D (L-type), α1E (R-type), and α1G (T-type) have been found in neonatal cultured cortical astrocytes [104], [105], [106], [107]. Additionally, the primary pituicytes express immunoreactivity for the Cav1.2 L-type, Cav2.1 P/Q-type, Cav2.2 N-type, Cav2.3 R-type, and Cav3.1 T-type subunits [108].

The homomeric α-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) are expressed in astrocytes, and activation of α7nAChRs in hippocampal slices or in culture has been shown to induce intracellular Ca2+ transients [109,110]. Other Ca2+ channels, such as Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels and plasmalemmal Ca2+-ATPase, also contribute to the astrocyte microdomain Ca2+ signals and other astrocytic functions [111]. While astrocytic Ca2+ events can originate from either pure intracellular or extracellular Ca2+ resources, they may also arise from the collaborative action of different sources [112,113].

4. Function of astrocytic Ca2+ signals

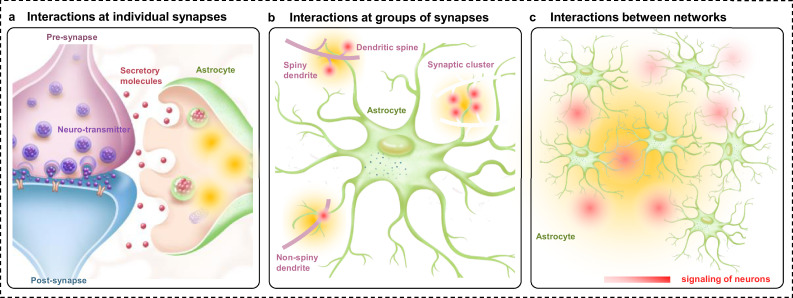

Ca2+ signaling assumes a fundamental role in diverse astrocytic functions, including the modulation of cerebral blood flow, synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, release of gliotransmitters, and neuronal spiking [1]. Additionally, the ability to generate Ca2+ events promotes ATP production by enhancing glycogenolysis [114]. Significantly, the complex morphology and wide distribution of astrocytes makes them well placed to exert local control over synapses and provide global support to neural circuits [9,115]. Astrocytes express numerous neurotransmitter receptors, particularly metabotropic receptors, which sense the microenvironment and induce intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Therefore, there exists a significant relationship between astrocytes and neurons that is mediated by Ca2+ signals. From the perspective of astrocytic Ca2+, the interaction between astrocytes and neurons can be divided into three models, interactions at individual synapses, interactions at groups of synapses, and interactions between networks (Fig. 3). Delving deeper into the intricacies of these interactions can contribute to a better understanding of synapse-astrocyte interactions.

Fig. 3.

Three modes of interaction between neurons and astrocytes. (a) Ca2+ events in perisynaptic astrocytic leaflets induce the release of signaling molecules that affect neuronal excitability, synaptic plasticity, and transmission. (b) Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling involves the territories of multiple synapses, which affect their plasticity/ activity. (c) Ca2+ events propagate through the astrocytic network and control information processing throughout the network of neurons.

4.1. Synaptic transmission

It is known that some astrocytic Ca2+ signals are intrinsic, while others are driven by ATP or neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine (NA), acetylcholine, and dopamine. Indeed, NA regulates Ca2+ events in astrocytes [53,57,58,116]. Paukert et al. showed that the NA released after light stimulation greatly enhanced astrocytic Ca2+ signals and shifted the gain of astrocytic networks according to the behavioral state, enabling astrocytes to respond to local changes in activity of neuron [57]. Similarly, Chen et al. characterized a previously undescribed glial type in zebrafish that resembles mammalian astrocytes and demonstrated that zebrafish astrocytes exhibit microdomain Ca2+ transients and respond to NA [117]. Another study further confirmed that Ca2+ levels in radial astrocytes of zebrafish increased with the number of failed swimming attempts [118]. Recently, Poskanzer's group reported that NA-driven astrocytic Ca2+ events acted as a distinct neuromodulatory signal to regulate state of cortex and linking arousal-associated desynchrony to cortical circuit resynchronization [119]. Moreover, Ca2+ transients were induced by acetylcholine in hippocampal and cortical astrocytes and modulate synaptic transmission [120,121]. Dopamine, which is produced in dopaminergic neurons, induced Ca2+ responses in astrocytes in the nucleus accumbens or hippocampus [122,123]. In the nucleus accumbens, dopamine increased Ca2+ in astrocytes, stimulated adenosine/ATP release and inhibited excitatory synaptic transmission by activating presynaptic A1 receptors [122]. In the hippocampus, dopamine triggered changes in the concentration of intracellular astrocytic calcium with enhanced associated effects on local synaptic function [123].

4.2. Synaptic plasticity

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is the most researched form of synaptic plasticity and is thought to be achieved by Ca2+ signals in astrocytes and neurons [124], [125], [126], [127], [128]. Interestingly, different Ca2+ signaling pathways in astrocytes are involved in different forms of LTP [52]. The classical form of LTP relies on NMDA receptors and Goshen's group reported that astrocytic activation induced de novo NMDA-dependent LTP in CA1 to further confirm this concept [129,130]. D-serine is an endogenous ligand for NMDA receptors and it has been reported that astrocytes regulated activation of LTP through Ca2+-dependent release of D-serine [131], [132], [133]. Additionally, Shigetomi et al. indicated that astrocytes contributed to NMDA receptor-dependent LTP, the activation of which caused Ca2+ influx, possibly through plasma membrane TRPA1 channels [78]. Navarrete et al. showed that cholinergic activity in vivo evoked by electrical or sensory stimulation increased astrocytic Ca²⁺ events and induced LTP in the hippocampus. Similarly, in hippocampal slices, stimulation of cholinergic pathways evoked astrocytic Ca²⁺ signals and induced LTP at single CA3-CA1 synapses [134]. Recently, Liu et al. demonstrated that through the integration of synaptic inputs, astrocyte inositol IP3R2-dependent Ca2+ signaling was crucial for late-phase LTP, which was mediated by astrocyte- and brain-derived neurotrophic factor [135].

4.3. Other functions of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes

Previous research has shown that changes in Ca2+ signals of astrocytes altered hemodynamics, increase glucose mobilization and influence cell activity by releasing neuroactive substances (e.g., glutamate, D-serine, and ATP) [136]. Moreover, Ca²+ signals in astrocytes stimulate the Na+- and K+-dependent adenosine triphosphatase, leading to a decrease in the extracellular concentration of K+ [36]. Furthermore, researchers have discovered widespread astrocytic Ca2+ events in the cortex, showing that 11% of astrocytes exhibited Ca2+ signaling closely correlated with the behavior of running [137]. Interestingly, some substances can also affect the function of Ca2+ events to mediate responses in astrocytes. Nagai et al. reported that a 122-residue inhibitory peptide of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 attenuated astrocyte Gq-GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signals and contributed to behavioral adaptation and spatial memory [64].

Notably, astrocytic Ca2+ signaling has been proposed to be involved in disease progression [59,138]. In AD mice, Kuchibhotla et al. reported that astrocytic Ca2+ events were more frequent after CNS damage and were enhanced in the amyloid deposition regions [139]. P2Y1 receptors, highly expressed by reactive astrocytes surrounding plaques, are reported to mediate astrocyte hyperactivity, and blockade of P2Y1 receptors significantly reduced astrocytic Ca2+ activity and normalized astrocytic dysfunction. In addition to P2Y1 receptor-mediated Ca2+ signals, Bosson et al. demonstrated that astrocytes contributed to early Aβo toxicity by exhibiting a global and local Ca2+ hyperactivity involving TRPA1 channels [140,141]. Additionally, Lee et al. demonstrated that picomolar amounts of Aβ peptides was detected via an astrocytic α7-nAChR-dependent mechanism, which responded with increased Ca2+ transients [142]. However, astrocytic Ca2+ signals were reduced during the early stages of Aβ deposition, while neurons were hyperactive and specific tactile memory loss occurred. Restoration of deficient Ca2+ signals attenuated neuronal hyperactivity and alleviated the clinical phenotypes [143,144]. In an HD mouse model, the amplitude, duration, and frequency of astrocyte Ca2+ events significantly reduced, but astrocytes responded vigorously to cortical stimulation with evoked action potential-dependent Ca2+ signaling [145].

In short, astrocytic Ca2+ events are vital for optimal physiological and pathological function. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms and the physiological and pathophysiological significance of Ca2+ in astrocytes remain poorly understood. Therefore, the study of Ca2+ events in astrocytes remains elusive and is envisioned as the focus of future biological research after the development of more advanced detection methods.

5. Analysis tools of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling

Compared to the easy identification of somas, astrocytic Ca2+ microdomain signaling is difficult to define. The processes of astrocytes extend thin lamellar sheets that contain minimal cytoplasm, posing a challenge to the detection of Ca2+ changes with cytosolic indicators. Due to technical difficulties in accessing the small spatial area of calcium microdomains, the role of astrocytic Ca2+ microdomain activity remains poorly understood. As a result, many experiments and analysis methods are constantly being updated, to better dissect the characteristics of Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes.

5.1. Indicators for detecting Ca2+ signals

Observing changes and timelines in intracellular Ca2+ signaling is essential for exploring the physiological and pathological states in the CNS. Ca2+ activity is varied in a single astrocyte and in astrocytic networks at different locations and times. Various indicators are used to determine the number, size, and position of detected Ca2+ signals, which are powerful tools for visualizing the activity of Ca2+ signals. Visualization and quantification of intracellular Ca2+ signals can be achieved using chemical Ca2+ indicators (e.g., Fura-2, Fluo-4, and Mag-Fura-Red) or genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECI) (e.g., GCaMPs, Pericams, and TN-XXL).

5.1.1. Chemical Ca2+ indicators

Beginning with the studies of Cornell-Bell et al., chemical Ca2+ indicators have been introduced into the study of astrocytic Ca2+ signal functions. These indicators have been widely used and the resulting data have significantly advanced the understanding of astrocyte function [42,146]. Importantly, the concentrations of the indicators should not exceed the buffering capacity of the cells [147,148]. Additionally, the selection of the most appropriate chemical Ca2+ indicator requires multiple considerations, including Ca2+ affinities, spectral properties, and the forms of different indicators [149].

Compared to GECIs, chemical Ca2+ indicators offer a notable advantage in that they are readily accessible commercially and can be easily employed without the need for cellular transfection. Moreover, cell-loading protocols have been well-established [150]. Thus, traditional chemical synthesis indicators have been widely used to investigate intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Selecting an appropriate chemical Ca2+ indicator requires various considerations, including Ca2+ affinities and spectral properties. However, these indicators have many limitations and problems, such as leakage, uneven dye loading photobleaching, and cytotoxicity. In particular, the cellular localization of the indicators cannot be specifically targeted to a particular organelle [149]. Therefore, they may be inappropriate indicators for the precise study of Ca2+ signaling [149].

5.1.2. Genetically-encoded Ca2+ indicators

Imaging of Ca2+ with protein-based indicators has been extensively used to follow neural activity in intact nervous systems. In recent years, GECIs have become one of the most comprehensive calcium indicators and have made outstanding contributions to the study of physiological functions and developmental mechanisms of different tissues and organisms [151]. GECIs have been particularly valuable in studying Ca2+ signals in branches and branchlets of astrocytes [59,152]. According to the luminescence principle, GECIs can be divided into two categories: single-fluorescent protein-based GECIs and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based GECIs [153]. The most commonly used single-fluorescent protein-based GECIs include GCaMPs, Camgaroos, and Pericams, while FRET-based GECIs include TN-XXL, D3cpV, and Cameleons [151,154].

Notably, GCaMP indicators are the most broadly used GECIs for monitoring Ca2+ in astrocytes. GCaMP indicators consist of a circularly permuted enhanced GFP moiety linked to the calcium-binding protein calmodulin (CaM) and the CaM-binding peptide M13pep [155]. The first GCaMP indicator was terribly dim and poorly folded at 37 °C, limiting its effectiveness for imaging. Improvement by grafting of GFP-stabilizing mutations and random mutagenesis led to the generation of GCaMP2, which showed significant improvements in the characteristics of fluorescence and folding [156], [157], [158]. Since then, groups at the Janelia Research Campus have continued to develop and optimize several rapid and sensitive GCaMP-type indicators by using structure-guided mutagenesis and large-scale screening. The main approaches to the introduction of single wavelength GECIs for the detection of Ca2+ signals are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the single wavelength GECIs for detecting astrocytic Ca2+signaling.

| Name | Wavelength (nm) |

Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation | Emission | PMID | ||

| GCaMP | GCaMP3 | 485 | 510 | 23868258 |

| GCaMP5G | 485 | 510 | 23868258 | |

| GCaMP5K | 485 | 510 | 23868258 | |

| GCaMP6f | 485 | 510 | 23868258 | |

| GCaMP6s | 485 | 510 | 23868258 | |

| GCaMP6m | 485 | 510 | 23868258 | |

| jGCaMP7s | 485 | 510 | 31209382 | |

| jGCaMP7f | 485 | 510 | 31209382 | |

| jGCaMP7b | 485 | 510 | 31209382 | |

| jGCaMP7c | 485 | 510 | 31209382 | |

| jGCaMP8s | 485 | 510 | 36922596 | |

| jGCaMP8m | 485 | 510 | 36922596 | |

| jGCaMP8f | 485 | 510 | 36922596 | |

| Lck-GCaMP6f | 488 | 510 | 27939582 | |

| jRCaMP1 | jRCaMP1a | 575 | 595 | 27011354 |

| jRCaMP1b | 570 | 595 | 27011354 | |

| jRGECO1a | 565 | 590 | 27011354 | |

| XCaMP-B | XCaMP-B | 405 | 446 | 31080068 |

| XCaMP-G | 488 | 514 | 31080068 | |

| XCaMP-Gf | 488 | 514 | 31080068 | |

| XCaMP-Gf0 | 488 | 514 | 31080068 | |

| XCaMP-Y | 488 | 527 | 31080068 | |

| XCaMP-R | 561 | 593 | 31080068 | |

Crucially, given the swift advancement of new techniques, there is a growing need for more precise localization of astrocytic Ca2+ signals. Scientists have developed membrane and organelle-targeted indicators that have been used in various studies [159], [160], [161]. In 2013, Khakh and his colleagues compared two types of GECIs, cyto-GCaMP3 and Lck-GCaMP3, and provided detailed descriptions to facilitate the systematic research on astrocytic Ca2+ signaling [48]. A few years later, O'Donnell et al. observed mitochondrially centered and extramitochondrial Ca2+ signals using Lck-GCaMP6s [162]. Mitochondria, as key organelles regulating Ca2+ signals, have been considered in the construction of DNA plasmids encoding GECIs. Chen et al. constructed a mito-GCaMP2 by genetic manipulation and demonstrated that the response of mitochondrial Ca2+ signals was diverse in different cell lines [163]. Similarly, Zhang et al. observed mitochondrial Ca2+ imaging of cultured astrocytes by transfecting with mito-GCaMP5G/6s in astrocytes [164]. The ER acts as a store that maintains Ca2+ homeostasis [165]. Aryal et al. developed ER-GCaMP6f and indicated that ER-GCaMP6f was expressed in vivo and used to measure Ca2+ activity in brain slices [160]. With the development of technology and the need for ongoing research, numerous membrane- and organelle-targeted indicators are being developed and applied.

5.2. Software

In order to investigate astrocytic Ca2+ signals in depth, various software tools that employ an event-based perspective to accurately quantify Ca2+ in fluorescence imaging datasets have been developed. Here, we discussed the most commonly used image analysis toolboxes tailored for astrocytic Ca2+ image data.

5.2.1. GECIquant

In 2015, Khakh et al. developed GECIquant, which allows for rapid semi-automated detection of regions of interest (ROIs) for Ca2+ signaling [50]. As the first software used to specifically analyze Ca2+ in GCaMP expressing astrocytes, GECIquant was able to automatically detect the microdomain and expand wave ROIs based on the provided area criteria. The GECIquant software focuses on the single cell level, with the ability to provide raw fluorescence data from different regions. Moreover, traces can be processed by the software to obtain additional features [166].

5.2.2. Ca2+ signal classification and decoding (CaSCaDe)

Subsequently, in 2017, CaSCaDe was developed, which was similar to GECIquant and used a machine learning-based algorithm to identify Ca2+ signaling. Significantly, the CaSCaDe software can represent the regions that exhibit dynamic fluorescence changes and provide information on frequency, number, time course, and amplitude [9].

5.2.3. Astrocyte quantitative analysis (AQuA)

Both GECIquant and CaSCaDe rely on ROIs and measure along time. Nevertheless, their shortcoming lies in the defined boundaries of microdomains, which would lead to inaccurate signals. Accordingly, Wang et al. presented a new analytical framework that releases researchers from the limitations of ROI-based tools. The AQuA software accurately quantifies complex Ca2+ signaling and neurotransmitter activity in fluorescence imaging datasets [167]. In this study, researchers demonstrated that the AQuA software outperformed other analysis methods on simulated datasets and described event detection using multiple GECIs. Further, it applies not only to fluorescent indicators, but also to others tested here, especially those with complex dynamics.

5.2.4. Cellular and hemodynamic image processing suite (CHIPS)

CHIPS is an open source toolbox developed to analyze the cells and blood vessels, primarily from two-photon microscopy [168]. Significantly, it can integrate a range of algorithms and streamline image analysis pipelines. In detail, CHIPS is best suited to examine a dataset using multiple approaches simultaneously. For instance, it can simultaneously analyze cell volume or vascular diameter [169].

5.2.5. Begonia

Begonia is a MATLAB-based two-photon imaging analysis toolbox developed for astrocytic Ca2+ signals [170]. The analysis suite includes an automatic, event-based algorithm with few input parameters that can capture a high level of spatio-temporal complexity of astrocytic Ca2+ signals. Furthermore, begonia enables the experimentalist to accurately quantify astrocytic Ca2+ signals and examine Ca2+ transients in conjunction with other time series data [169].

5.2.6. Deconvolution of Ca2+ fluorescent patterns (deCLUTTER)

Recently, Grochowska et al. developed a new pipeline for calcium imaging data analysis called deCLUTTER2+, which can be used to discover spontaneous or cue-dependent patterns of Ca2+ transients [171]. In their study, to better integrate the data from the different cell lines, deCLUTTER was used to analyze the variability of Ca2+ at different time points, with older astrocytes contributing to the clusters of more responsive cells.

6. Conclusion and perspectives

This review focuses on the recent advances in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, contributing to more comprehensive understanding of Ca2+ events in astrocytes. In particular, we describe the main characteristics of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, exploring its genesis and functions in the CNS. Finally, we provide an overview of the analytical tools used to study astrocytic Ca2+ signaling.

Despite these advances, research in this field is still in its infancy, leaving several fundamental questions unanswered. Firstly, the heterogeneity of astrocytes may be reflected in various types of Ca2+ signaling [172,173]. Supporting this perspective, given the demonstrated astrocytic heterogeneity across different brain regions, Khakh et al. identified distinct astrocytic Ca2+ signals in the CA3 region compared to other regions of the hippocampus [54,[174], [175], [176], [177], [178]]. Secondly, in vivo changes in astrocytic Ca2+ signals are diverse and complex over both short and long time periods. Therefore, a pressing need exists for enhanced experiments that can comprehensively investigate astrocyte responses across different temporal scales, building on the refined comprehension of Ca2+ signals in vivo. When scientists can consistently and accurately observe and measure specific astrocyte Ca2+ microdomain signaling with spatial and temporal resolution, the field will be well-positioned to delve into the functions of astrocytes in the CNS. Thirdly, the investigation of the properties and biophysics of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in processes deserves further attention. Notably, anesthesia, a critical confounding factor, has been confirmed to affect Ca2+ responses within astrocytes. Therefore, maintaining mice in an awake state is imperative when researchers investigate Ca2+ signals [172,179,180]. Selection of sensitive critical indicators, in particular GECIs, allows in vivo monitoring of astrocytic Ca2+ activity in precise regions. Fourth, the present studies may not systematically reflect the functions of astrocytic Ca2+ events throughout the entire brain. More attention should be directed towards understanding the synergistic effect between astrocytic Ca2+ events and other components of the neurovascular unit. Takano et al. reported that astrocytic Ca2+ signals mediated vasodilation in response to increased neural activity [181]. In essence, the study highlights the necessity for more systematic research on astrocytic Ca2+ signals in the future. Consequently, it is crucial to adopt more comprehensive strategies and develop new technologies to enhance our understanding of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in vivo.

Numerous challenges in this field warrant in-depth exploration. Key questions that require addressing include: (1) What is the precise molecular mechanism by which astrocytes control Ca2+? (2) Can novel methods be developed to regulate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in specific brain regions? (3) Do altered astrocyte Ca2+ signals contribute to specific CNS diseases via different pathways?

In consideration of the aforementioned points, despite clear progress, further in-depth studies are needed to explore the molecular mechanisms of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes. Hence, the next stage of research into astrocytic Ca2+ signals should persistently emphasize investigations into astrocyte-related physiology, pathology, and animal behaviors. This strategic focus will undoubtedly contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the pivotal roles of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in both normal and pathological conditions, paving the way for significant advancements in the foreseeable future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (82025033), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82230115, 82273914), the Science and Technology innovation 2030-Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021ZD0202904/2021ZD0202900), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2242022R40059), the Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Critical Care Medicine (JSKLCCM-2022-02-008), and the Open Project Program of the Key Laboratory of Developmental Genes and Human Diseases, Ministry of Education, China (LDGHD202304).

Biographies

Ying Bai(BRID: 06882.00.86191) is an associate professor at Southeast University. She obtained her Ph.D. degree from Southeast University in 2018. Her current research interests focus on the regulation of glial cells in neuroinflammation and related central nervous system diseases, such as ischemic stroke and depression.

Honghong Yao(BRID: 09227.00.02257) is a professor at Southeast University. Her research interests focus on major neurological diseases, such as stroke and depression. Concentrating on the shared pathological mechanism underlying these diseases, specifically the neuroinflammatory response, she dedicates her efforts to addressing pivotal scientific challenges related to diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets using the field of non-coding RNA molecular biology. The research findings illuminate the pathological mechanisms of major nervous system diseases from a fresh perspective, introducing innovative concepts and potential pharmaceuticals for both diagnosis and treatment.

References

- 1.Bazargani N., Attwell D. Astrocyte calcium signaling: The third wave. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19(2):182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen N.J., Lyons D.A. Glia as architects of central nervous system formation and function. Science. 2018;362(6411):181–185. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer L., Schafer D.P., Bartels T., et al. Diversity and function of glial cell types in multiple sclerosis. Trends. Immunol. 2021;42(3):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Q., Scheller A., Huang W. Progenies of NG2 glia: What do we learn from transgenic mouse models ? Neural Regen. Res. 2021;16(1):43–48. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.286950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H.G., Wheeler M.A., Quintana F.J. Function and therapeutic value of astrocytes in neurological diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022;21(5):339–358. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman M.R. Specification and morphogenesis of astrocytes. Science. 2010;330(6005):774–778. doi: 10.1126/science.1190928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endo F., Kasai A., Soto J.S., et al. Molecular basis of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and disease. Science. 2022;378(6619):eadc9020. doi: 10.1126/science.adc9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosaka T., Hama K. Three-dimensional structure of astrocytes in the rat dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1986;249(2):242–260. doi: 10.1002/cne.902490209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal A., Wu P.H., Hughes E.G., et al. Transient opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore induces microdomain calcium transients in astrocyte processes. Neuron. 2017;93(3):587–605.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X., Nagai J., Khakh B.S. Improved tools to study astrocytes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020;21(3):121–138. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogata K., Kosaka T. Structural and quantitative analysis of astrocytes in the mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2002;113(1):221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai H., Diaz-Castro B., Shigetomi E., et al. Neural circuit-specialized astrocytes: Transcriptomic, proteomic, morphological, and functional evidence. Neuron. 2017;95(3):531–549.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushong E.A., Martone M.E., Jones Y.Z., et al. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J. Neurosci. 2002;22(1):183–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou B., Zuo Y.X., Jiang R.T. Astrocyte morphology: Diversity, plasticity, and role in neurological diseases. CNS. Neurosci. Ther. 2019;25(6):665–673. doi: 10.1111/cns.13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khakh B.S., Sofroniew M.V. Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18(7):942–952. doi: 10.1038/nn.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takano T., Wallace J.T., Baldwin K.T., et al. Chemico-genetic discovery of astrocytic control of inhibition in vivo. Nature. 2020;588(7837):296–302. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2926-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saint-Martin M., Goda Y. Astrocyte-synapse interactions and cell adhesion molecules. FEBS. J. 2023;290(14):3512–3526. doi: 10.1111/febs.16540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aryal S.P., Neupane K.R., Masud A.A., et al. Characterization of astrocyte morphology and function using a fast and reliable tissue clearing technique. Curr. Protoc. 2021;1(10):e279. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verkhratsky A., Nedergaard M. Physiology of astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98(1):239–389. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallo V., Deneen B. Glial development: The crossroads of regeneration and repair in the CNS. Neuron. 2014;83(2):283–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodnight R.B., Gottfried C. Morphological plasticity of rodent astroglia. J. Neurochem. 2013;124(3):263–275. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundgaard I., Osorio M.J., Kress B.T., et al. White matter astrocytes in health and disease. Neuroscience. 2014;276:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson J.E., Ince P.G., Lace G., et al. Astrocyte phenotype in relation to Alzheimer-type pathology in the ageing brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010;31(4):578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beauquis J., Pavia P., Pomilio C., et al. Environmental enrichment prevents astroglial pathological changes in the hippocampus of APP transgenic mice, model of Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Neurol. 2013;239:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh C.Y., Vadhwana B., Verkhratsky A., et al. Early astrocytic atrophy in the entorhinal cortex of a triple transgenic animal model of Alzheimer's disease. ASN Neuro. 2011;3(5):271–279. doi: 10.1042/AN20110025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Booth H.D.E., Hirst W.D., Wade-Martins R. The role of astrocyte dysfunction in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Trends. Neurosci. 2017;40(6):358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong J., Ang L.C., Williams B., et al. Low levels of astroglial markers in Parkinson's disease: Relationship to alpha-synuclein accumulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;82:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lastres-Becker I., Ulusoy A., Innamorato N.G., et al. alpha-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21(14):3173–3192. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clapham D.E. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131(6):1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patergnani S., Danese A., Bouhamida E., et al. Various aspects of calcium signaling in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, cell proliferation, and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(21):8323. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izquierdo-Torres E., Hernandez-Oliveras A., Fuentes-Garcia G., et al. Calcium signaling and epigenetics: A key point to understand carcinogenesis. Cell Calcium. 2020;91 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2020.102285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlecker C., Boehmerle W., Jeromin A., et al. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 enhancement of InsP3 receptor activity is inhibited by therapeutic levels of lithium. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116(6):1668–1674. doi: 10.1172/JCI22466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eickholt B.J., Towers G.J., Ryves W.J., et al. Effects of valproic acid derivatives on inositol trisphosphate depletion, teratogenicity, glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibition, and viral replication: A screening approach for new bipolar disorder drugs derived from the valproic acid core structure. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67(5):1426–1433. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam M.S. Calcium signaling: From basic to bedside. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1131:1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-12457-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alves V.S., Alves-Silva H.S., Orts D.J.B., et al. Calcium signaling in neurons and glial cells: Role of cav1 channels. Neuroscience. 2019;421:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang F., Smith N.A., Xu Q., et al. Astrocytes modulate neural network activity by Ca(2)+-dependent uptake of extracellular K+ Sci. Signal. 2012;5(218):ra26. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borrachero-Conejo A.I., Saracino E., Natali M., et al. Electrical stimulation by an organic transistor architecture induces calcium signaling in nonexcitable brain cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019;8(3) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang J., Kang N., Lovatt D., et al. Connexin 43 hemichannels are permeable to ATP. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(18):4702–4711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verkhratsky A., Kettenmann H. Calcium signalling in glial cells. Trends. Neurosci. 1996;19(8):346–352. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowser D.N., Khakh B.S. Two forms of single-vesicle astrocyte exocytosis imaged with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(10):4212–4217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bojarskaite L., Bjornstad D.M., Pettersen K.H., et al. Astrocytic Ca(2+) signaling is reduced during sleep and is involved in the regulation of slow wave sleep. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):3240. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17062-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khakh B.S., McCarthy K.D. Astrocyte calcium signaling: From observations to functions and the challenges therein. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015;7(4) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim D., Semyanov A., Genazzani A., et al. Calcium signaling in neuroglia. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021;362:1–53. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thrane A.S., Rappold P.M., Fujita T., et al. Critical role of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling events elicited by cerebral edema. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108(2):846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015217108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duffy S., MacVicar B.A. In vitro ischemia promotes calcium influx and intracellular calcium release in hippocampal astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1996;16(1):71–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00071.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denizot A., Arizono M., Nagerl U.V., et al. Control of Ca(2+) signals by astrocyte nanoscale morphology at tripartite synapses. Glia. 2022;70(12):2378–2391. doi: 10.1002/glia.24258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosche J., Matyash V., Moller T., et al. Microdomains for neuron-glia interaction: Parallel fiber signaling to Bergmann glial cells. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2(2):139–143. doi: 10.1038/5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shigetomi E., Bushong E.A., Haustein M.D., et al. Imaging calcium microdomains within entire astrocyte territories and endfeet with GCaMPs expressed using adeno-associated viruses. J. Gen. Physiol. 2013;141(5):633–647. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shigetomi E., Kracun S., Sofroniew M.V., et al. A genetically targeted optical sensor to monitor calcium signals in astrocyte processes. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13(6):759–766. doi: 10.1038/nn.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srinivasan R., Huang B.S., Venugopal S., et al. Ca(2+) signaling in astrocytes from Ip3r2(-/-) mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18(5):708–717. doi: 10.1038/nn.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rungta R.L., Bernier L.P., Dissing-Olesen L., et al. Ca(2+) transients in astrocyte fine processes occur via Ca(2+) influx in the adult mouse hippocampus. Glia. 2016;64(12):2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/glia.23042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volterra A., Liaudet N., Savtchouk I. Astrocyte Ca(2)(+) signalling: An unexpected complexity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15(5):327–335. doi: 10.1038/nrn3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semyanov A., Henneberger C., Agarwal A. Making sense of astrocytic calcium signals - from acquisition to interpretation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020;21(10):551–564. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Castro M.A., Chuquet J., Liaudet N., et al. Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14(10):1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunn K.M., Hill-Eubanks D.C., Liedtke W.B., et al. TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(15):6157–6162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216514110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Straub S.V., Bonev A.D., Wilkerson M.K., et al. Dynamic inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium signals within astrocytic endfeet underlie vasodilation of cerebral arterioles. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;128(6):659–669. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paukert M., Agarwal A., Cha J., et al. Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron. 2014;82(6):1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding F., O'Donnell J., Thrane A.S., et al. alpha1-Adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice. Cell Calcium. 2013;54(6):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shigetomi E., Patel S., Khakh B.S. Probing the complexities of astrocyte calcium signaling. Trends. Cell Biol. 2016;26(4):300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stobart J.L., Ferrari K.D., Barrett M.J.P., et al. Cortical circuit activity evokes rapid astrocyte calcium signals on a similar timescale to neurons. Neuron. 2018;98(4):726–735.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nizar K., Uhlirova H., Tian P., et al. In vivo stimulus-induced vasodilation occurs without IP3 receptor activation and may precede astrocytic calcium increase. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(19):8411–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3285-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q., Kong Y., Wu D.Y., et al. Impaired calcium signaling in astrocytes modulates autism spectrum disorder-like behaviors in mice. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):3321. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23843-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agulhon C., Fiacco T.A., McCarthy K.D. Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Science. 2010;327(5970):1250–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.1184821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagai J., Bellafard A., Qu Z., et al. Specific and behaviorally consequential astrocyte G(q) GPCR signaling attenuation in vivo with ibetaARK. Neuron. 2021;109(14):2256–2274.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stobart J.L., Ferrari K.D., Barrett M.J.P., et al. Long-term in vivo calcium imaging of astrocytes reveals distinct cellular compartment responses to sensory stimulation. Cereb. Cortex. 2018;28(1):184–198. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okubo Y., Kanemaru K., Suzuki J., et al. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 2-independent Ca(2+) release from the endoplasmic reticulum in astrocytes. Glia. 2019;67(1):113–124. doi: 10.1002/glia.23531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parpura V., Grubisic V., Verkhratsky A. Ca(2+) sources for the exocytotic release of glutamate from astrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1813(5):984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sherwood M.W., Arizono M., Hisatsune C., et al. Astrocytic IP(3) Rs: Contribution to Ca(2+) signalling and hippocampal LTP. Glia. 2017;65(3):502–513. doi: 10.1002/glia.23107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olson M.L., Chalmers S., McCarron J.G. Mitochondrial organization and Ca2+ uptake. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40(1):158–167. doi: 10.1042/BST20110705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zorov D.B., Juhaszova M., Sollott S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94(3):909–950. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernardi P., Petronilli V. The permeability transition pore as a mitochondrial calcium release channel: A critical appraisal. J. Bioenergy Biomembr. 1996;28(2):131–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02110643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loncke J., Kaasik A., Bezprozvanny I., et al. Balancing ER-mitochondrial Ca(2+) fluxes in health and disease. Trends. Cell Biol. 2021;31(7):598–612. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gautier C.A., Erpapazoglou Z., Mouton-Liger F., et al. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interface is perturbed in PARK2 knockout mice and patients with PARK2 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25(14):2972–2984. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ottolini D., Cali T., Negro A., et al. The Parkinson disease-related protein DJ-1 counteracts mitochondrial impairment induced by the tumour suppressor protein p53 by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22(11):2152–2168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu Y., Ma X., Fujioka H., et al. DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116(50):25322–25328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906565116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hedskog L., Pinho C.M., Filadi R., et al. Modulation of the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interface in Alzheimer's disease and related models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(19):7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shigetomi E., Tong X., Kwan K.Y., et al. TRPA1 channels regulate astrocyte resting calcium and inhibitory synapse efficacy through GAT-3. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;15(1):70–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shigetomi E., Jackson-Weaver O., Huckstepp R.T., et al. TRPA1 channels are regulators of astrocyte basal calcium levels and long-term potentiation via constitutive d-serine release. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(24):10143–10153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5779-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malarkey E.B., Ni Y., Parpura V. Ca2+ entry through TRPC1 channels contributes to intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and consequent glutamate release from rat astrocytes. Glia. 2008;56(8):821–835. doi: 10.1002/glia.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Benfenati V., Amiry-Moghaddam M., Caprini M., et al. Expression and functional characterization of transient receptor potential vanilloid-related channel 4 (TRPV4) in rat cortical astrocytes. Neuroscience. 2007;148(4):876–892. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pizzo P., Burgo A., Pozzan T., et al. Role of capacitative calcium entry on glutamate-induced calcium influx in type-I rat cortical astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2001;79(1):98–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grimaldi M., Maratos M., Verma A. Transient receptor potential channel activation causes a novel form of [Ca2+]I oscillations and is not involved in capacitative Ca2+ entry in glial cells. J. Neurosci. 2003;23(11):4737–4745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04737.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oh S.J., Lee J.M., Kim H.B., et al. Ultrasonic neuromodulation via astrocytic TRPA1. Curr. Biol. 2019;29(20):3386–3401.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Uchiyama M., Nakao A., Kurita Y., et al. O(2)-dependent protein internalization underlies astrocytic sensing of acute hypoxia by restricting multimodal TRPA1 channel responses. Curr. Biol. 2020;30(17):3378–3396.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ma Z., Stork T., Bergles D.E., et al. Neuromodulators signal through astrocytes to alter neural circuit activity and behaviour. Nature. 2016;539(7629):428–432. doi: 10.1038/nature20145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ma Z., Freeman M.R. TrpML-mediated astrocyte microdomain Ca2+ transients regulate astrocyte-tracheal interactions. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.58952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shelton M.K., McCarthy K.D. Mature hippocampal astrocytes exhibit functional metabotropic and ionotropic glutamate receptors in situ. Glia. 1999;26(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199903)26:1<1::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palygin O., Lalo U., Verkhratsky A., et al. Ionotropic NMDA and P2×1/5 receptors mediate synaptically induced Ca2+ signalling in cortical astrocytes. Cell Calcium. 2010;48(4):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lalo U., Palygin O., Rasooli-Nejad S., et al. Exocytosis of ATP from astrocytes modulates phasic and tonic inhibition in the neocortex. PLOS Biol. 2014;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dzamba D., Honsa P., Valny M., et al. Quantitative analysis of glutamate receptors in glial cells from the cortex of GFAP/EGFP mice following ischemic injury: Focus on NMDA receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;35(8):1187–1202. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mehina E.M.F., Murphy-Royal C., Gordon G.R. Steady-state free Ca(2+) in astrocytes is decreased by experience and impacts arteriole tone. J. Neurosci. 2017;37(34):8150–8165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0239-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Porter J.T., McCarthy K.D. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J. Neurosci. 1996;16(16):5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schipke C.G., Ohlemeyer C., Matyash M., et al. Astrocytes of the mouse neocortex express functional N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. FASEB J. 2001;15(7):1270–1272. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0439fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brazhe A.R., Verisokin A.Y., Verveyko D.V., et al. Sodium-calcium exchanger can account for regenerative Ca(2+) entry in thin astrocyte processes. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:250. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heja L., Kardos J. NCX activity generates spontaneous Ca(2+) oscillations in the astrocytic leaflet microdomain. Cell Calcium. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2019.102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wade J.J., Breslin K., Wong-Lin K., et al. Calcium microdomain formation at the perisynaptic cradle due to NCX reversal: A computational study. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:185. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.North R.A. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82(4):1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dixon S.J., Yu R., Panupinthu N., et al. Activation of P2 nucleotide receptors stimulates acid efflux from astrocytes. Glia. 2004;47(4):367–376. doi: 10.1002/glia.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Franke H., Grosche J., Schadlich H., et al. P2X receptor expression on astrocytes in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Neuroscience. 2001;108(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fumagalli M., Brambilla R., D'Ambrosi N., et al. Nucleotide-mediated calcium signaling in rat cortical astrocytes: Role of P2X and P2Y receptors. Glia. 2003;43(3):218. doi: 10.1002/glia.10248. -03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen L.Q., Lv X.J., Guo Q.H., et al. Asymmetric activation of microglia in the hippocampus drives anxiodepressive consequences of trigeminal neuralgia in rodents. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023;180(8):1090–1113. doi: 10.1111/bph.15994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pannicke T., Fischer W., Biedermann B., et al. P2×7 receptors in Muller glial cells from the human retina. J. Neurosci. 2000;20(16):5965–5972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-05965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Catterall W.A. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3(8) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cahoy J.D., Emery B., Kaushal A., et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: A new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(1):264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Y., Chen K., Sloan S.A., et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014;34(36):11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Latour I., Hamid J., Beedle A.M., et al. Expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subtypes in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2003;41(4):347–353. doi: 10.1002/glia.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.D'Ascenzo M., Vairano M., Andreassi C., et al. Electrophysiological and molecular evidence of l-(Cav1), N- (Cav2.2), and R- (Cav2.3) type Ca2+ channels in rat cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2004;45(4):354–363. doi: 10.1002/glia.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang D., Yan B., Rajapaksha W.R., et al. The expression of voltage-gated ca2+ channels in pituicytes and the up-regulation of L-type ca2+ channels during water deprivation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(10):858–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shen J.X., Yakel J.L. Functional alpha7 nicotinic ACh receptors on astrocytes in rat hippocampal CA1 slices. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2012;48(1):14–21. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9719-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Corradi J., Bouzat C. Understanding the bases of function and modulation of alpha7 nicotinic receptors: Implications for drug discovery. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016;90(3):288–299. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.104240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moreau B., Straube S., Fisher R.J., et al. Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent facilitation and Ca2+ inactivation of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(10):8776–8783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lia A., Henriques V.J., Zonta M., et al. Calcium signals in astrocyte microdomains, a decade of great advances. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.673433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Toth A.B., Hori K., Novakovic M.M., et al. CRAC channels regulate astrocyte Ca(2+) signaling and gliotransmitter release to modulate hippocampal GABAergic transmission. Sci. Signal. 2019;(582):12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaw5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ververken D., Van Veldhoven P., Proost C., et al. On the role of calcium ions in the regulation of glycogenolysis in mouse brain cortical slices. J. Neurochem. 1982;38(5):1286–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb07903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Araque A., Carmignoto G., Haydon P.G., et al. Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron. 2014;81(4):728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Slezak M., Kandler S., Van Veldhoven P.P., et al. Distinct mechanisms for visual and motor-related astrocyte responses in mouse visual cortex. Curr. Biol. 2019;29(18):3120–3127.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen J., Poskanzer K.E., Freeman M.R., et al. Live-imaging of astrocyte morphogenesis and function in zebrafish neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2020;23(10):1297–1306. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mu Y., Bennett D.V., Rubinov M., et al. Glia accumulate evidence that actions are futile and suppress unsuccessful behavior. Cell. 2019;178(1):27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.050. e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Reitman M.E., Tse V., Mi X., et al. Norepinephrine links astrocytic activity to regulation of cortical state. Nat. Neurosci. 2023;26(4):579–593. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01284-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Papouin T., Dunphy J.M., Tolman M., et al. Septal cholinergic neuromodulation tunes the astrocyte-dependent gating of hippocampal NMDA receptors to wakefulness. Neuron. 2017;94(4):840–854.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Takata N., Mishima T., Hisatsune C., et al. Astrocyte calcium signaling transforms cholinergic modulation to cortical plasticity in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2011;31(49):18155–18165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Corkrum M., Covelo A., Lines J., et al. Dopamine-evoked synaptic regulation in the nucleus accumbens requires astrocyte activity. Neuron. 2020;105(6):1036–1047.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jennings A., Tyurikova O., Bard L., et al. Dopamine elevates and lowers astroglial Ca(2+) through distinct pathways depending on local synaptic circuitry. Glia. 2017;65(3):447–459. doi: 10.1002/glia.23103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Vints W.A.J., Levin O., Fujiyama H., et al. Exerkines and long-term synaptic potentiation: Mechanisms of exercise-induced neuroplasticity. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2022;66 doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2022.100993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kauer J.A., Malenka R.C. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8(11):844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chindemi G., Abdellah M., Amsalem O., et al. A calcium-based plasticity model for predicting long-term potentiation and depression in the neocortex. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):3038. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30214-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Saw G., Krishna K., Gupta N., et al. Epigenetic regulation of microglial phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway involved in long-term potentiation and synaptic plasticity in rats. Glia. 2020;68(3):656–669. doi: 10.1002/glia.23748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jorntell H. Cerebellar synaptic plasticity and the credit assignment problem. Cerebellum. 2016;15(2):104–111. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0623-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Henneberger C., Papouin T., Oliet S.H., et al. Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463(7278):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Adamsky A., Kol A., Kreisel T., et al. Astrocytic activation generates de novo neuronal potentiation and memory enhancement. Cell. 2018;174(1):59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.002. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schell M.J., Molliver M.E., Snyder S.H. d-serine, an endogenous synaptic modulator: Localization to astrocytes and glutamate-stimulated release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 1995;92(9):3948–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mothet J.P., Parent A.T., Wolosker H., et al. D-serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97(9):4926–4931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Panatier A., Theodosis D.T., Mothet J.P., et al. Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell. 2006;125(4):775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Navarrete M., Perea G., Fernandez de Sevilla D., et al. Astrocytes mediate in vivo cholinergic-induced synaptic plasticity. PLOS Biol. 2012;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu J.H., Zhang M., Wang Q., et al. Distinct roles of astroglia and neurons in synaptic plasticity and memory. Mol. Psychiatry. 2022;27(2):873–885. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Haydon P.G. GLIA: Listening and talking to the synapse. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2(3):185–193. doi: 10.1038/35058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dombeck D.A., Khabbaz A.N., Collman F., et al. Imaging large-scale neural activity with cellular resolution in awake, mobile mice. Neuron. 2007;56(1):43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Nedergaard M., Rodriguez J.J., Verkhratsky A. Glial calcium and diseases of the nervous system. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(2):140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kuchibhotla K.V., Lattarulo C.R., Hyman B.T., et al. Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science. 2009;323(5918):1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1169096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bosson A., Paumier A., Boisseau S., et al. TRPA1 channels promote astrocytic Ca(2+) hyperactivity and synaptic dysfunction mediated by oligomeric forms of amyloid-beta peptide. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0194-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Paumier A., Boisseau S., Jacquier-Sarlin M., et al. Astrocyte-neuron interplay is critical for Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis and is rescued by TRPA1 channel blockade. Brain. 2022;145(1):388–405. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lee L., Kosuri P., Arancio O. Picomolar amyloid-beta peptides enhance spontaneous astrocyte calcium transients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(1):49–62. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Shah D., Gsell W., Wahis J., et al. Astrocyte calcium dysfunction causes early network hyperactivity in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Rep. 2022;40(8) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lia A., Sansevero G., Chiavegato A., et al. Rescue of astrocyte activity by the calcium sensor STIM1 restores long-term synaptic plasticity in female mice modelling Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):1590. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Jiang R., Diaz-Castro B., Looger L.L., et al. Dysfunctional calcium and glutamate signaling in striatal astrocytes from Huntington's disease model mice. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(12):3453–3470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3693-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Cornell-Bell A.H., Finkbeiner S.M., Cooper M.S., et al. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: Long-range glial signaling. Science. 1990;247(4941):470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1967852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Tsien R.Y. Fluorescence measurement and photochemical manipulation of cytosolic free calcium. Trends. Neurosci. 1988;11(10):419–424. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Neher E. Quantitative aspects of calcium fluorimetry. Cold. Spring. Harb. Protoc. 2013;2013(10):918–924. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top078204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Paredes R.M., Etzler J.C., Watts L.T., et al. Chemical calcium indicators. Methods. 2008;46(3):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]