Abstract

Modern pharmacological studies have elucidated the presence of aconitine (AC) alkaloids, polysaccharides, and saponins as the primary bioactive constituents of Fuzi. Among these, benzoylaconine, a pivotal active compound, demonstrates notable pharmacological properties including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and cardiovascular protective effects. In recent years, benzoylaconine has garnered significant attention in basic research on heart diseases, emerging as a focal point of investigation. This paper presents a comprehensive review of the pharmacological effects of benzoylaconine, alongside an overview of advancements in metabolic characterization. The objective is to furnish valuable insights that can serve as a cornerstone for further exploration, utilization, and advancement of benzoylaconine in pharmacological research.

Keywords: anti-inflammation, benzoylaconine, cardiac diseases, pharmacokinetics, pharmacological effects

1. Introduction

Radix Aconiti lateralis praeparata, known as “Fuzi” in Chinese, is the processed cotyledon root of Aconitum carmichaeli. It is traditionally valued and used for dispelling cold, relieving pain effects, and treating shock [1, 2]. It has been documented in the ancient Chinese pharmacopeia, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing, and is predominantly cultivated in several Chinese provinces, including Sichuan, Shanxi, Hubei, Hunan, and Yunnan. In traditional Chinese herbal medicine, Fuzi occupies an important position and is highly regarded for its significant pharmacological effects on the cardiovascular system. Specifically, it is frequently used in the treatment of hypotension, coronary artery disease, and shock resulting from acute myocardial infarction, particularly in cases of heart failure [3–5].

This medicinal plant contains a plethora of structurally distinct active ingredients, including aconitine (AC) alkaloids, polysaccharides, saponins, flavonoids, fatty acids, and sterols, which contribute to its pharmacological properties. Research has demonstrated that Fuzi exhibits a range of beneficial effects, including cardiomyocyte protection, antiarrhythmic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties [6]. Additionally, it has shown promising antitumor properties [7, 8], leading to its widespread utilization in clinical practice [9, 10].

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the use of Fuzi comes with inherent risks of toxic side effects. While Fuzi holds therapeutic potential in treating cardiac diseases, rheumatic diseases, tumors, and more at low doses, high doses may lead to adverse effects such as ventricular tachyarrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and even lethality [11]. Therefore, there is a pressing need for the development of safe, effective, and low-toxicity compounds derived from Fuzi to maximize its therapeutic benefits while minimizing potential risks.

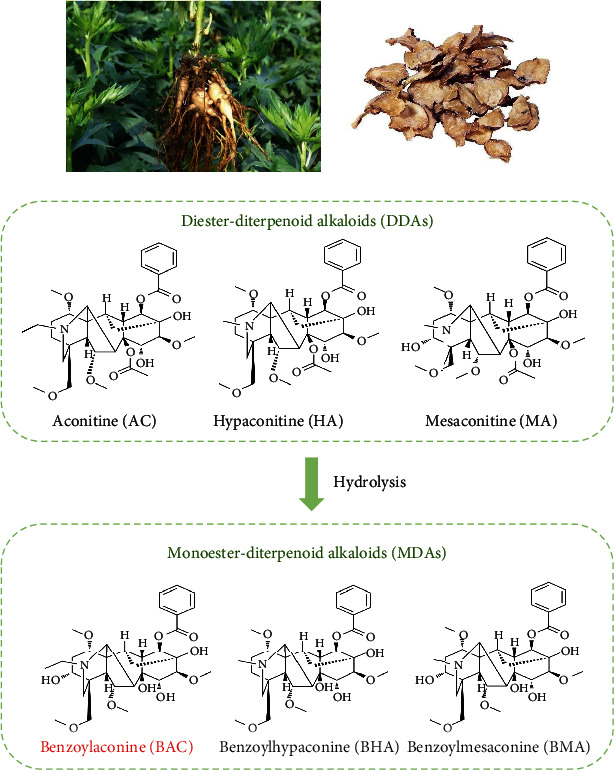

The alkaloids present in Fuzi predominantly consist of monoesteric diterpene alkaloids (MDAs) and diester-type diterpenoid alkaloids (DDAs) [12], as depicted in Figure 1. These diterpenoid alkaloids not only serve as the essential active compounds responsible for Fuzi's medicinal effects but also constitute its toxic components [13].

Figure 1.

Relationships between the studied MDAs and DDAs of Fuzi.

Benzoylaconitine (BAC) is a monoester alkaloid and a characteristic constituent of Fuzi, but it is present in low levels. It is mainly produced by hydrolyzing the diester alkaloids during the decoction of Fuzi [14, 15]. This hydrolysis process effectively diminishes the toxicity of Fuzi, suggesting that BAC holds promise as a cardioprotective agent.

Based on an extensive review of existing literature, this paper focuses on consolidating, structuring, and presenting the most recent advancements regarding BAC in the realms of cardiovascular diseases, anti-inflammatory effects, and analgesic properties. The objective of this endeavor is to aid scientists and clinicians in comprehending the significance of BAC, thereby providing valuable insights to guide future research, development, and clinical utilization of this compound.

2. Literature Search Strategies on BAC

The EMBASE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and PubMed databases were searched (up to Jan 2024) using the following terms: “Benzoylaconine” AND (“Isaconitine” OR “Pikraconitin” OR “pharmacokinetic” OR “Toxicity” OR “Pharmacological” OR “Cardiovascular”). The reference lists from the relevant studies were analyzed for additional literature.

3. Basic Properties and Information

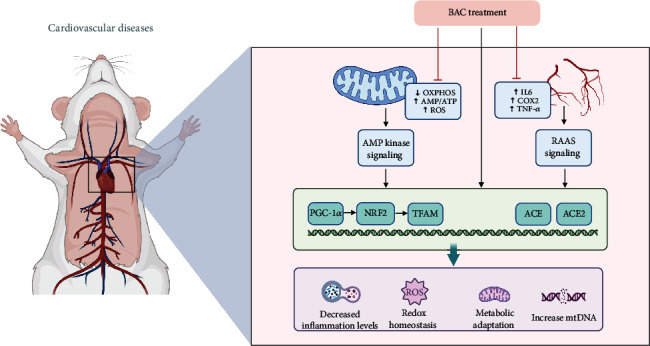

BAC, a principal monoester alkaloid present in Fuzi, holds significance in traditional Chinese medicine. The 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia stipulates that the combined content of BAC, benzoylhypaconine (BHA), and benzoylmesaconine (BMA) in Fuzi should not fall below 0.010%. Known by various names including BAC, Isaconitine, and Pikraconitin, BAC appears as white crystals and exhibits solubility in methanol (8 mg/mL), ethanol, isopropanol, and trichloromethane (approximately 25 mg/mL), with slight solubility in water. Its molecular formula is C32H45NO10. BAC, characterized by its white crystalline form, displays notable properties. It demonstrates anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects, contributes to safeguarding cardiovascular function, and enhances glycoprotein transporter activity. Particularly in the context of cardiovascular function protection, BAC has shown significant therapeutic efficacy, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of BAC on cardiovascular diseases.

4. Pharmacological Effects of BAC and Its Mechanisms

4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Effect and Mechanism

The anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of BAC constitute its primary action, demonstrating efficacy in suppressing arthritic inflammation and various types of pain, as evidenced in ex vivo models [16]. In a study utilizing rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes (HFLS-RA) [17] (refer to Table 1), BAC inhibited the proliferation of HFLS-RA cells, showcasing in vitro antirheumatic activity. The underlying mechanism may be linked to the inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production and the downregulation of expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, and TLR4. Additionally, BAC exhibited significant anti-inflammatory effects on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages, with the lowest effective anti-inflammatory dose compared to other MDAs [18]. Aconiti Radix Cocta, comprising the aforementioned MDAs, alleviated foot-plantar swelling, mitigated joint tissue inflammation and bone destruction, reduced serum levels of IL-1β and IL-17A, and downregulated the expression of COX-1 and COX-2 in synovial tissue in adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA) rats [19]. Further molecular mechanism involves the regulation of arachidonic acid metabolism pathways. In another study, Gai et al. [20] encapsulated BAC into highly biocompatible copolymers to form NP/BAC for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. The NP/BAC group exhibited a 70% reduction in TNF-α and a 66% reduction in IL-1β compared to activated macrophages. This effect was attributed to the diminished overexpression of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65 and the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. It is widely acknowledged that the content of toxic alkaloids (AC, hypaconitine (HA), and mesaconitine (MA)) decreases, while the content of nontoxic alkaloids (BAC, BHA, and BMA) increases with the prolonged decoction time of the compound formula [21]. Zhang et al. [22] demonstrated that BAC is among the constituents in the compound dHsp (derived Hei-shun-pian) that play a therapeutic role in osteoarthritis (OA).

Table 1.

Basic information on experiments related to the pharmacological effects of BAC and its mechanisms.

| Refs | Research model | Phenotype/pathways | BAC dose (way) | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism | ||||

| [17] | HFLS-RA cell | Inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production | 1000 μg/mL | TLR4, HIF-1α, and VEGF↓ |

| [20] | Rheumatoid arthritis mice LPS-induced RAW264.7 |

Inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production | Mice 10 mg/kg, iv injection Cell: 5, 18, and 40 μg/mL |

NF-κB p65↓ IL-1β, and TNF-α↓ |

| [22] | Osteoarthritis rat | Inhibits chondrocyte hypertrophy | 14 g/kg dHSP, orally administered for 28 days | Col2↑ Col10, Mmp2, and Sox5↓ |

| [42] | LPS-activated RAW264.7 macrophage cell | MAPK and NF-κB pathways | 500 μM | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS, NO, and PGE2↓ iNOS, COX-2↓ |

| Analgesic effect and mechanism | ||||

| [23] | Spinal L5/L6 nerve-ligated neuropathic rats | Attenuated mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia | 2.2 μg, intrathecal injection | Dynorphin A↑ |

| [24] | Acetate pain mouse model | Decreased the writhing number significantly | 350 μg/cm2; 5.0 cm2 | Pain inhibition ratio > 50% |

| Cardiomyocyte protective effect | ||||

| [33] | HepG2 cell Balb/c mice |

AMPK signaling | 25, 50, and 75 μM 10 mg/kg per day, for 7 days, ip |

OXPHOS, mtDNA, ATP, and mitochondrial mass↑ |

| [34] | OGD/R-induced cardiomyocyte injury | AMPK/PGC-1 axis | 25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 μM | p-AMPK, PGC-1α↑ |

| Alleviates the effects of hypertension | ||||

| [38] | Spontaneously hypertension rats | ACE/ACE2; Akt/eNOS | 0.6, 2, and 6 mg/kg; iv injection | NO↑ Ang II, TNF-α, IL 6, COX-2, and IKBα↓ |

| Skin protective effect | ||||

| [41] | TNF-α/LPS-induced HaCaT keratinocytes | STAT3 pathway | 10, 20, and 40 μM | TNF-α, IL-17, and p-STAT3↓ |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AMPK, adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; HFLS-RA, rheumatoid arthritis; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; OGD/R, oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

In brief, the anti-inflammatory mechanism of BAC primarily operates by regulating the activity of inflammatory signaling pathways and diminishing the production and release of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-1β. The specific pathways involved are mostly associated with NF-κB.

4.2. Analgesic Effect and Mechanism

In the realm of analgesia, Li, Gong, and Wang [23] observed that intrathecal administration of BAC not only effectively attenuated mechanical and thermal pain in rats afflicted with neuropathic pain but also significantly upregulated the gene expression of dynorphin in primary cultured microglia. This implies that BAC may induce analgesic effects by triggering the expression of dynorphin in spinal microglia. Despite the commendable analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties exhibited by BAC [17], its brief half-life and rapid metabolism prompted Liu et al. [24] to devise patches employing BAC as the primary ingredient. These patches, by regulating plasma drug concentrations, demonstrated efficacy in sustaining stable anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. However, the stratum corneum's barrier function poses constraints on the transdermal penetration of BAC, ensuring the safety of drug delivery while positioning BAC as a promising candidate for inflammatory pain management [25, 26].

The analgesic mechanism of action of this substance may be linked to the modulation of central opioid receptors. Experiments have indicated that its analgesic effect can be diminished by knocking out the opioid receptor gene and administering naloxone. Furthermore, research has illustrated that the activity of the C-5's position on the aromatic ring of Fuzi alkaloids significantly impacts its analgesic efficacy [27].

4.3. Cardiomyocyte Protective Effect

Fuzi, with its rich history in Chinese herbal medicine and widespread usage, has garnered attention in modern pharmacological studies. Research has unveiled that numerous components within Fuzi possess the ability to enhance sinus node autoregulation, improve atrioventricular conduction, bolster cardiac pumping function, and offer protection and repair for cardiomyocytes [28, 29]. Among these components, BAC stands out as a major active ingredient in Fuzi, attracting significant attention in basic research concerning cardiovascular diseases [30, 31].

Wang et al. [32] used bioinformatics screening to explore the key molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic agents in dilated cardiomyopathy combined with heart failure and found that BAC is a potential candidate that may exert its therapeutic effects by targeting the regulation of myocardial energy metabolism through NRK (nicotinamide riboside kinase) and NT5. Deng et al. [33] demonstrated, both ex vivo and in vivo, that BAC significantly boosts mitochondrial mass, ATP production, and the expression of proteins linked with oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes in HepG2 cells in a dose-dependent manner (25, 50, 75 μM). Mechanistically, this enhancement is associated with the upregulation of proteins in the AMPK signaling cascade, leading to AMPK signaling activation in the heart, liver, and muscle, consequently improving cardiac function. Furthermore, Chen, Yan, and Zhang [34] (Figure 2) corroborated the modulation of the AMPK signaling pathway by BAC in their study, which simulated H9C2 cell injury in heart failure through oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R). BAC intervention activated the AMPK/PGC-1 axis, thereby regulating mitochondrial function improvement in OGD/R-treated H9C2 cells and suppressing oxidative stress [35]. Moreover, BAC has shown promise as a potent inhibitor of erastin-induced iron death in cardiomyocytes [36]. Other studies [37] have indicated that diterpenoid alkaloids like BAC may manifest varying degrees of inhibitory effects on distinct classes of voltage-dependent potassium channel currents. These compounds have been observed to modulate the time course of cardiomyocyte action potentials, thereby potentially exerting antiarrhythmic effects.

In summary, BAC is characterized by multiple pathways and targets and is a potential protective agent for the cardiovascular system. However, most of the existing studies were conducted only at the cellular level to simulate the relevant diseases and lack of studies on primary cardiomyocytes and advanced animal models. The protective effect of BAC on cardiomyocytes may involve multiple disease intervention mechanisms at the same time, and the intrinsic connection of the pathogenesis of these several diseases may broaden the ideas for further research. On the other hand, data mining and molecular docking can be used to screen the pharmacologically active targets of BAC in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases and synergize with related pharmacodynamic studies to elucidate its pharmacological mechanism of action.

4.4. Alleviates the Effects of Hypertension

In another study [38], it was demonstrated that BAC exhibits the most potent blood pressure-lowering effect among several monoester alkaloids. Its administration in spontaneously hypertensive rats revealed its capability to bind to ACE/ACE2 receptors and other targets, thereby augmenting endothelium-dependent vasodilation while inhibiting ACE activity and related protein expression (Figure 2). Furthermore, BAC was found to suppress COX-2 expression and IKB-α phosphorylation, thereby mitigating vascular inflammation and alleviating hypertension. In summary, BAC exerts multifaceted regulatory effects on cardiovascular diseases, serving as a potential modulator of the renin–angiotensin system and a promising therapeutic agent for hypertension [39].

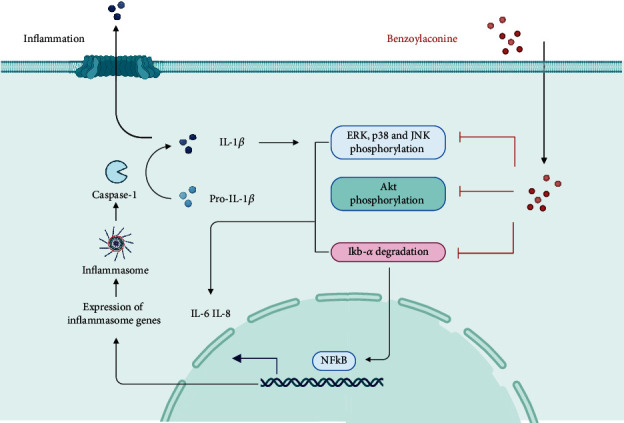

4.5. Skin Protective Effect

Psoriasis, a chronic and multifactorial skin disease, is distinguished by inflammatory infiltration, proliferation of keratinized cells, and accumulation of immune cells [40]. In a study by Li et al., BAC was utilized to intervene in TNF-α/LPS-induced HaCat keratinized cells. BAC demonstrated significant efficacy in inhibiting cell proliferation and the release of inflammatory factors associated with psoriasis, without any discernible adverse effects on cell viability and safety as evidenced by ex vivo experiments. The specific mechanism of action was attributed to the suppression of the STAT3 pathway [41]. Moreover, BAC not only curtails the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-8 and IL-6 [42] but also diminishes the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphorylation of Akt. BAC predominantly exerts its protective effects on the skin by stifling the release of inflammatory factors. These actions manifest anti-inflammatory effects in IL-1β-stimulated human synoviocytes, and their efficacy hinges upon the MAPK, Akt, and NF-κB pathways, as delineated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Main anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action of BAC.

4.6. Other Effects

Moreover, alkaloids like BAC notably stimulate the expression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and enhance exocytosis activity [43, 44]. This attribute may be attributed to its relatively mild toxicity profile. Furthermore, BAC demonstrates antidiarrheal properties by impeding spontaneous intestinal activity in mice, primarily by affecting isolated small intestinal smooth muscle [45].

5. Progress in Toxicological Studies

Fuzi contains a substantial amount of DDAs, with the sodium channel 2 site being the cardiotoxic target of these compounds [46]. The mechanism underlying their cardiotoxicity involves a significant influx of Na+ ions, leading to the development of persistent malignant arrhythmias. DDAs are predominantly cardiotoxic and neurotoxic, and their mechanisms of toxicity are related to their actions on voltage-dependent Na+ channels, modulation of neurotransmitter release and related receptors, promotion of lipid peroxidation, and induction of apoptosis in the heart, liver, or other organs [47, 48]. Through appropriate processing, these DDAs undergo hydrolysis at the C-8 position, resulting in their conversion to less toxic MDAs, namely, BAC, BMA, and BHA [35, 49]. When both the C-8 and C-14 groups are hydrolyzed, their derivatives become virtually devoid of toxicity, yielding nontoxic nonester alkaloids (NDAs) [50–52], as illustrated in Figure 1.

The toxicity of MDAs is significantly lower than that of DDAs, with a human lethal dose ranging from 1 to 4 mg. In mice, the toxicity of BAC is notably lower than that of DDAs, with an LD50 of 1500 mg/kg [53, 54], approximately 1/700 to 1/100 of that of DDAs. Consequently, the hydrolysis of DDAs in Fuzi produces active compounds with reduced toxicity. This process suggests the potential to discover less toxic drugs from the metabolites of DDAs, offering alternatives to the more toxic alkaloids.

In addition to this, compatibility has often been utilized to mitigate toxicity and enhance efficacy, as outlined in Table 2. When compounding Fuzi, two herbs are typically combined to achieve the dual purpose of reducing toxicity and augmenting efficacy [55]. These combinations serve as the fundamental units commonly employed in Chinese herbal formulations, offering a simpler approach compared to more intricate mixtures while preserving the basic therapeutic characteristics of Fuzi. Different combinations yield varying effects on the dissolution of Fuzi's active ingredients and metabolic enzymes within the body. Fuzi is frequently coadministered with liquorice, Ganjiang, ginseng, or paeoniae [56] to expedite the metabolism of its toxic constituents and unleash its therapeutic effects. This concurrent administration not only diminishes toxicity but also amplifies efficacy in clinical applications. The rationale behind these combinations can be elucidated by considering the drug-metabolizing enzymes of Fuzi's active ingredients and the mechanism of toxicity reduction in the combined therapy. Many of the active components in the herbs paired with Fuzi can modulate the activities of various CYP450 isoforms, countering any abnormalities in drug metabolism induced by Fuzi. For instance, Li et al. [57] observed that Fuzi exerted an inhibitory effect on hepatic microsomal CYP450 enzyme activity through hepatic microsomal CYP450 enzyme systematic assay. However, when combined with Fangfeng, a significant increase in CYP450 expression was noted. It can be inferred that the combination of Fuzi and Fangfeng induces and enhances the activity of the CYP3A4 enzyme, consequently accelerating the metabolism of DDAs, the toxic components of Fuzi.

Table 2.

Classical Chinese herbal medicine compound of Fuzi.

| Year Refs | Herbal combination | Ratio of compounds | Coadministration effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 [58] | Fuzi-Ganjiang | 1 : 1 | Ganjiang could promote the elimination of AC and HA and enhance the absorption of BAC. |

| 2017 [61] | Fuzi and Beimu | 1 : 1 | Fuzi in combination with Beimu was favorable for absorption of BMA and BHA. |

| 2017 [60] | Fuzi-Mahuang | 11 : 6 | Decreased cumulative excretion of monoester alkaloids (BAC and BHA) |

| 2022 [59] | Fuzi and ginseng | 1 : 1 | Could significantly increase the bioavailability and efficiency of active components in vivo |

| 2015 [28] | Shenfu decoction | 1 : 1 | Shenfu decoction could significantly improve hepatic injury in CHF patients. |

| 2018 [29] | Shenfu formula | 1 : 1 | Shenfu granule can effectively improve cardiac function in heart failure rats. |

Peng et al. conducted a study where rats were administered Fuzi and Fuzi-Ganjiang aqueous extracts, and the concentrations of MDAs and DDAs in rat plasma were determined at specified time points postadministration [58]. Compared to the Fuzi-alone group, the Fuzi-Ganjiang group exhibited reduced T1/2 and AUC0-t of DDAs, alongside increased T1/2, AUC0-t, and Cmax of MDAs. These findings suggest that Ganjiang facilitates the clearance of DDAs while enhancing the uptake of MDAs, such as BAC. This supports the theory that the combination of Fuzi-Ganjiang reduces toxicity and enhances efficacy, providing a rationale for the Fuzi-Ganjiang combination.

In a nutshell, BAC serves as a less toxic active compound resulting from the hydrolysis of DDAs, significantly mitigating its original toxicity while maintaining its primary efficacy.

6. Pharmacokinetic Study of BAC

BAC is moderately soluble in water, approximately 1 mg/mL. Special solvents have also been used to aid solubilization followed by intraperitoneal administration [31, 53]. Consequently, the choice of solvents by different researchers can influence the absorption process to a certain extent. Additionally, variations in the compound's extraction processes, the percentage of Fuzi [58, 59], and the content of BAC in the final solution contribute to inconsistencies in pharmacokinetic parameters across various studies [60]. However, despite these variations, the general trends observed in the drug-time curves did not exhibit significant differences, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

BAC main pharmacokinetic parameters.

| Year Refs | Subjects | Dose | BAC parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1/2 (min) | Tmax (min) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC 0−t (ng/min/mL) | |||

| 2013 [58] | Rats (n = 6) | 5.4 g crude drug of Fuzi/kg | 186.62 ± 14.12 | 35.18 ± 5.88 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 355.67 ± 19.43 |

| 2016 [53] | Rats (n = 6) | 1 mg/kg BAC | 9.49 ± 0.49 h | 0.31 ± 0.17 h | 3.99 ± 1.20 | 13.54 ± 2.29 (ng/h/mL) |

| 2017 [61] | Rats (n = 6) | Fuzi aqueous, 20 g/kg | 5.67 ± 1.49 h | 1.93 ± 1.26 h | 2.83 ± 0.73 | 18.96 ± 5.82 (μg·h/L) |

| 2019 [63] | Rats (n = 6) | 18.95 mg/kg BAC | 12.38 ± 4.02 h | 0.71 ± 0.13 h | 12.82 ± 5.80 | 40.44 ± 13.61 (ng/h/mL) |

| 2022 [59] | Rats (n = 6) | 2 g/kg of Fuzi | 9.28 ± 0.18 h | 1.00 ± 0.07 h | 0.39 ± 0.22 | 4.47 ± 0.54 |

| 2014 [78] | Rats (n = 6) | 18.75 μg/mL–1.5 mL/100 g | 9.40 ± 2.30 h | 0.60 ± 0.30 h | 151.60 ± 129.30 | 323.80 ± 190.80 (ng/h/mL) |

BAC demonstrates a rapid absorption rate, with blood concentration peaking within 1 h postinjection. In healthy SD rats administered 1 mg/kg of BAC via gavage, the mean maximum plasma concentration was 3.99 ± 1.20 ng/mL, and plasma concentration remained detectable within 1 h postadministration [53, 61]. BAC permeated all tissues, with concentrations peaking at 4 h. Primary accumulations were observed in the heart and kidneys, while a small fraction of BAC crossed the blood-brain barrier and was absorbed into the brain. The distribution order was as follows: heart > kidney > liver > lung > spleen > brain [53]. Similarly, Xiaojun et al. investigated the distribution of several key alkaloids in various tissues and organs of rabbits after administering a high dose of aqueous aconite extract (0.20 ± 0.05 mg/g) via gavage. Their study revealed that BAC was highly concentrated in the spleen, liver, and kidney tissues of the rabbits [62].

The cardioprotective effect of BAC is currently its most recognized efficacy. Zhou et al. [63] introduced a novel method employing ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) and applied it to the pharmacokinetic study of three MDAs in normal and myocardial infarcted rats after the oral administration of SND (Sini decoction). The study revealed that following the oral administration of SND, myocardial infarction rats exhibited lower blood concentrations of the MDAs compared to normal rats. Additionally, the elimination and distribution of these alkaloids were slower in myocardial infarction rats, resulting in less systemic exposure, nontoxicity, and evident cardioprotective effects. In vivo distribution studies of BAC also indicated a higher concentration of the drug in the heart, providing supportive evidence for its pharmacodynamic effects.

Plasma proteins serve a pivotal role in enhancing the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs by aiding in their transport and distribution throughout the body via the bloodstream. Thus, Zhou et al. [64] employed multispectroscopy, molecular docking, and kinetic simulation to explore the interaction mechanism between human serum albumin (HSA) and BAC. The study revealed that residues such as TRP-214, LEU-219, LEU-238, and ALA-291 played crucial roles in the binding of BAC to HSA, thereby shedding light on the distribution and metabolic pattern of BAC.

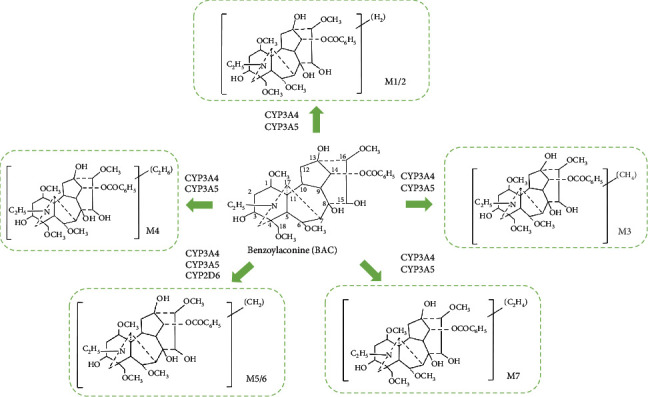

BAC is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 and CP3A5 [65], and the metabolic pathways include demethylation, dehydrogenation, hydroxylation, and dimethylation. Regarding the determination of metabolic composition, the unique structural features of BAC result in a greater number of metabolites but with lower concentrations, posing challenges for structural identification. Seven known metabolites include dehydrogen-BAC, dehydrogen-BAC, demethyl-dehydrogen-BAC, didemethyl-dehydrogen-BAC/deethyl-dehydrogen-BAC, Demethyl-BAC, demethyl-BAC, and deethyl-BAC/didemethyl-BAC, and the metabolic process is shown in Figure 4. It is evident that the metabolic pathway of BAC is largely mediated by CYP3A, implying that caution should be exercised in the clinical use of Fuzi in combination with drugs metabolized by CYP3A4, as there is a potential for drug-drug interactions. BAC is predominantly excreted through feces, with the fecal concentration of BAC being considerably higher than that in urine.

Figure 4.

Major metabolites of benzoylaconitine.

Noteworthy is a pharmacokinetic study conducted in humans [66]. Three dosages at low (10.0 mg/kg), medium (13.3 mg/kg), and high (16.7 mg/kg) levels of “SHEN-FU” injectable powder were applied on 18 healthy volunteers by intravenous drop infusion. Every 10 mg “SHEN-FU” injectable powder contained 1103.5 ng BAC. Six volunteers were involved in each experiment. The results indicated that the half-life of BAC at all three administered doses was approximately 1 h. They all achieved the maximum concentration at 30 min in medium dosage, however, 45 min in low and high dosages.

7. Discussion and Future Perspectives

This review represents the first comprehensive summary of the research progress regarding the pharmacological effects of BAC, a less studied and less toxic component of Fuzi. BAC demonstrates promising potential for development into an effective clinical formulation. Recent studies on BAC have emphasized chemical spectrum analysis, pharmacological investigations, conventional toxicological studies, and its potential therapeutic value [67, 68]. BAC exhibits diverse effects in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, and the regulation of immune function, showcasing its involvement in disease treatment through multiple targets and pathways. In relation to cardiovascular disease, there is a burgeoning body of research indicating the significant involvement of inflammatory factors [69]. Oxidative stress and inflammation stand out as major contributors to cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia. Therefore, mitigating systemic inflammation holds promise for decreasing the likelihood of cardiovascular events. A study demonstrated that decreased levels of IL-6 led to a 32% reduction in the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events [70]. The potent anti-inflammatory properties of BAC underscore its potential as a cardioprotective agent.

Regarding the mode of BAC administration and dosage, which may be responsible for its lower bioavailability and faster elimination, frequent intravenous injections of about 2–10 mg/kg (Table 1) were used in most of the animal experiments, and there was a clear dose dependence of BAC in the safe range (LD50 of 1500 mg/kg) [53].

Nevertheless, there remain several aspects of BAC research that warrant further exploration. Firstly, the safety, tolerance, and efficacy of BAC are not yet fully understood, and its clinical value, particularly regarding potential toxic side effects [71], necessitates further verification based on current studies to facilitate its clinical application. Secondly, the specific mechanism of BAC's action remains elusive. Hence, it is imperative to investigate the multitarget, multipathway pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interactions of BAC to uncover the intrinsic science behind its therapeutic effects. Given that BAC is rapidly absorbed in the body, understanding its metabolic processes is crucial. For example, the pharmacokinetic parameters Cmax, Tmax, and T1/2 of BAC were found to be 39.85 ± 12.02 ng/mL, 0.31 ± 0.17 h, and 9.49 ± 0.49 h, respectively. These values suggest that BAC is quickly absorbed but not easily metabolized or excreted. However, the lower Cmax indicates that the bioavailability of BAC is not high, potentially due to inhibition by some transport proteins [68]. Future research on BAC should explore its metabolites, their related ratios, and comprehensively study the pharmacological effects and toxicities of BAC to provide a reliable foundation for its clinical application.

Additionally, DDAs significantly restrict the utilization of Fuzi [72]. While BAC's pharmacological action as an active ingredient holds promise in alleviating this limitation, its extraction technology poses challenges, and the extraction cost is high [73, 74]. Addressing these issues requires further basic research and technical support.

Another aspect worth noting is the low bioavailability of BAC, which has significantly restricted the development and clinical application of BAC-related formulations. Therefore, exploring new delivery systems to enhance the bioavailability of BAC presents an intriguing research direction. Overall, research on the pharmacological mechanism of action of BAC and Fuzi is gradually deepening, particularly in the field of cardioprotection [75], which is of significant interest. However, there remains a lack of clinical trials to confirm the safety and efficacy of BAC. The complex extraction process and expensive production cost of BAC, combined with the limited number of current studies on its pharmacological effects, have posed barriers to its clinical application. Some researchers have incorporated Fuzi as the main ingredient into injections and conducted clinical studies on its efficacy [76, 77], yielding positive results. It is anticipated that the mechanism of action of BAC will become clearer with further deepening of research.

Acknowledgments

Figures 2 and 3 are created with http://BioRender.com. We did not use third-party services or artificial intelligence software.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this review are from previously reported studies and datasets, which have been cited. The processed data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C. X., L. T., and J. T. prepared the original draft. Y. H., L. H., and X. W. contributed in reviewing and editing. F. W. designed the project. C. X. and L. T. contributed equally.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Committee for the pharmacopoeia of China. Pharmacopoeia of China, Part I . Beijing: China Medical Science and Technology Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou G., Tang L., Zhou X., Wang T., Kou Z., Wang Z. A review on phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the processed lateral root of Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;160:173–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z., Yang S., Lin X., et al. Metabolomics of Spleen-Yang deficiency syndrome and the therapeutic effect of Fuzi Lizhong pill on regulating endogenous metabolism. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2021;278, article 114281 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park J., Bak S., Chu H., et al. Current research status and implication for further study of real-world data on East Asian traditional medicine for heart failure: a scoping review. Healthcare . 2024;12(1) doi: 10.3390/healthcare12010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X., Xie X., Luo M., et al. The synergistic compatibility mechanisms of fuzi against chronic heart failure in animals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2022;13, article 954253 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.954253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X., Yi Y., Jiang C., et al. Gancao Fuzi decoction regulates the Th17/Treg cell imbalance in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting Foxp3 via miR-34a. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2023;301, article 115837 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Q., Liu Y., Yu J., et al. The protective effect and antitumor activity of Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata (Fuzi) polysaccharide on cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression in H22 tumor-bearing mice. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2023;14, article 1151092 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1151092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao X., Han B., Jiang X., Li F., He M., Liu F. Effects of benzoyl aconitine on autophagy and apoptosis of human lung cancer cell line A 549. China Pharmacy . 2019;12:2782–2788. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao T., Zhang H., Li Q., et al. Fuzi decoction treats chronic heart failure by regulating the gut microbiota, increasing the short-chain fatty acid levels and improving metabolic disorders. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis . 2023;236, article 115693 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Y., Pang H., Zhao L., et al. Ginseng total saponins and Fuzi total alkaloids exert antidepressant-like effects in ovariectomized mice through BDNF-mTORC1, autophagy and peripheral metabolic pathways. Phytomedicine . 2022;107, article 154425 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z., Lin Y., Gao L., et al. Circadian clock regulates metabolism and toxicity of Fuzi(lateral root of Aconitum carmichaeli Debx) in mice. Phytomedicine . 2020;67, article 153161 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y., Sun H., Li C., et al. Comparative HPLC-MS/MS-based pharmacokinetic studies of multiple diterpenoid alkaloids following the administration of Zhenwu Tang and Radix Aconiti Lateralis Praeparata extracts to rats. Xenobiotica . 2021;51(3):345–354. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2020.1866229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S., Lai C., Long Y., et al. The global profiling of alkaloids in Aconitum stapfianum and analysis of detoxification material basis against Fuzi. Journal of Chromatography A . 2021;1652, article 462362 doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C., Liang D., Liu Y., et al. Evaluation of the influence of Zhenwu Tang on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin in rats using HPLC-MS/MS. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021, article 2673183:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2021/2673183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M., Hu W. J., Zhou X., et al. Ethnopharmacological use, pharmacology, toxicology, phytochemistry, and progress in Chinese crude drug processing of the lateral root of Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux. (Fuzi): A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2023;301, article 115838 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C., Gao J., Ji H., et al. Benzoylaconine modulates LPS-induced responses through inhibition of toll-like receptor-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling in RAW264. 7 cells. Inflammation . 2021;44(5):2018–2032. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01478-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L., Siyiti M., Zhang J., Yao M., Zhao F. Anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic activities in vitro of alkaloids separated from Aconitum soongoricum Stapf. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine . 2021;21(5):p. 493. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou C., Gao J., Qu H., et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of action of benzoylmesaconine in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2022;2022, article 7008907:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2022/7008907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S., Li R., Xu Y. X., et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Aconiti Radix Cocta improves rheumatoid arthritis via suppressing COX-1 and COX-2. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021, article 5523870:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2021/5523870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gai W., Hao X., Zhao J., et al. Delivery of benzoylaconitine using biodegradable nanoparticles to suppress inflammation via regulating NF-κB signaling. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces . 2020;191, article 110980 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z., Yuan J., Dai Y., Xia Y. Integration of serum pharmacochemistry and metabolomics to reveal the underlying mechanism of shaoyao-gancao-fuzi decoction to ameliorate rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2024;326, article 117910 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Li T., Wang R., et al. Evaluation of long-time decoction-detoxicated Hei-shun-pian (processed Aconitum carmichaeli Debeaux lateral root with peel) for its acute toxicity and therapeutic effect on mono-iodoacetate induced osteoarthritis. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2020;11:p. 1053. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T. F., Gong N., Wang Y. X. Ester hydrolysis differentially reduces aconitine-induced anti-hypersensitivity and acute neurotoxicity: involvement of spinal microglial dynorphin expression and implications for Aconitum processing. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2016;7:p. 367. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C., Farah N., Weng W., Jiao B., Shen M., Fang L. Investigation of the permeation enhancer strategy on benzoylaconitine transdermal patch: the relationship between transdermal enhancement strength and physicochemical properties of permeation enhancer. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2019;138, article 105009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.105009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J.-L., Shen X.-L., Chen Q.-H., Qi G., Wang W., Wang F.-P. Structure–analgesic activity relationship studies on the C18-and C19-diterpenoid alkaloids. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin . 2009;57(8):801–807. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanimura Y., Yoshida M., Ishiuchi K., Ohsawa M., Makino T. Neoline is the active ingredient of processed aconite root against murine peripheral neuropathic pain model, and its pharmacokinetics in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2019;241, article 111859 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bello-Ramírez A. M., Buendía-Orozco J., Nava-Ocampo A. A. A QSAR analysis to explain the analgesic properties of Aconitum alkaloids. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology . 2003;17(5):575–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei H., Wu H., Yu W., Yan X., Zhang X. Shenfu decoction as adjuvant therapy for improving quality of life and hepatic dysfunction in patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;169:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan X., Wu H., Ren J., et al. Shenfu formula reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis in heart failure rats by regulating microRNAs. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2018;227:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing Z., Yang C., He J., et al. Cardioprotective effects of aconite in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2022;2022:16. doi: 10.1155/2022/1090893.1090893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Q. Q., Chen Q. S., Feng F., Cao X., Chen X. F., Zhang H. Benzoylaconitine: a promising ACE2-targeted agonist for enhancing cardiac function in heart failure. Free Radical Biology & Medicine . 2024;214:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H., Cai P., Yu X., et al. Bioinformatics identifies key genes and potential drugs for energy metabolism disorders in heart failure with dilated cardiomyopathy. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2024;15, article 1367848 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1367848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng X. H., Liu J. J., Sun X. J., Dong J. C., Huang J. H. Benzoylaconine induces mitochondrial biogenesis in mice via activating AMPK signaling cascade. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica . 2019;40(5):658–665. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L., Yan L., Zhang W. Benzoylaconine improves mitochondrial function in oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte injury by activation of the AMPK/PGC-1 axis. Korean Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology . 2022;26(5):325–333. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.5.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H. G., Sun Y., Duan M. Y., Chen Y. J., Zhong D. F., Zhang H. Q. Separation and identification of Aconitum alkaloids and their metabolites in human urine. Toxicon . 2005;46(5):500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kajarabille N., Latunde-Dada G. O. Programmed cell-death by ferroptosis: antioxidants as mitigators. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2019;20(19):p. 4968. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiss T., Borcsa B., Orvos P., Tálosi L., Hohmann J., Csupor D. Diterpene lipo-alkaloids with selective activities on cardiac K+ channels. Planta Medica . 2017;83(17):1321–1328. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-109556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Q. Q., Chen F. H., Wang F., Di X. M., Li W., Zhang H. A novel modulator of the renin-angiotensin system, benzoylaconitine, attenuates hypertension by targeting ACE/ACE2 in enhancing vasodilation and alleviating vascular inflammation. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2022;13, article 841435 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.841435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin J.-S., Chan C.-Y., Yang C., Wang Y.-H., Chiou H.-Y., Su Y.-C. Zhi-fuzi, a cardiotonic Chinese herb, a new medical treatment choice for portal hypertension? Experimental Biology and Medicine . 2007;232(4):557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C., Cao X., Zhao L., et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Shi-Bi-Man ameliorates psoriasis via inhibiting IL-23/Th17 axis and CXCL16-mediated endothelial activation. Chinese Medicine . 2024;19(1):p. 38. doi: 10.1186/s13020-024-00907-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Guo D., Wang Q., et al. Benzoylaconitine alleviates progression of psoriasis via suppressing STAT3 phosphorylation in keratinocytes. Molecules . 2023;28(11):p. 4473. doi: 10.3390/molecules28114473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu H.-H., Li M., Li Y.-B., et al. Benzoylaconitine inhibits production of IL-6 and IL-8 via MAPK, Akt, NF-κB signaling in IL-1β-induced human synovial cells. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin . 2020;43(2):334–339. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b19-00719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J. J., Zhu Y. F., Guo Z. Z., et al. Aconitum alkaloids, the major components of Aconitum species, affect expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 and breast cancer resistance protein by activating the Nrf2-mediated signalling pathway. Phytomedicine . 2018;44:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye L., Yang X., Yang Z., et al. The role of efflux transporters on the transport of highly toxic aconitine, mesaconitine, hypaconitine, and their hydrolysates, as determined in cultured Caco-2 and transfected MDCKII cells. Toxicology Letters . 2013;216(2-3):86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J., Lin N., Li F., et al. Induction of P-glycoprotein expression and activity by Aconitum alkaloids: implication for clinical drug-drug interactions. Scientific Reports . 2016;6(1, article 25343) doi: 10.1038/srep25343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu M., Wu M., Qiao Y., Wang Z. Toxicological mechanisms of Aconitum alkaloids. Die Pharmazie-An International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2006;61(9):735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y. J., Tao P., Wang Y. Attenuated structural transformation of aconitine during sand frying process and antiarrhythmic effect of its converted products. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021, article 7243052:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2021/7243052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friese J., Gleitz J., Gutser U. T., et al. Aconitum sp. alkaloids: the modulation of voltage-dependent Na+ channels, toxicity and antinociceptive properties. European Journal of Pharmacology . 1997;337(2-3):165–174. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye L., Wang T., Yang C., et al. Microsomal cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of hypaconitine, an active and highly toxic constituent derived from Aconitum species. Toxicology Letters . 2011;204(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tong P., Wu C., Wang X., et al. Development and assessment of a complete-detoxication strategy for Fuzi (lateral root of Aconitum carmichaeli) and its application in rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;146(2):562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singhuber J., Zhu M., Prinz S., Kopp B. Aconitum in traditional Chinese medicine: a valuable drug or an unpredictable risk? Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2009;126(1):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H. G., Shi X. G., Sun Y., Duan M. Y., Zhong D. F. New metabolites of aconitine in rabbit urine. Chinese Chemical Letters . 2002;13(8):758–760. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H., Sun S., Zhang W., et al. Biological activities and pharmacokinetics of aconitine, benzoylaconine, and aconine after oral administration in rats. Drug Testing and Analysis . 2016;8(8):839–846. doi: 10.1002/dta.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wada K., Nihira M., Hayakawa H., Tomita Y., Hayashida M., Ohno Y. Effects of long-term administrations of aconitine on electrocardiogram and tissue concentrations of aconitine and its metabolites in mice. Forensic Science International . 2005;148(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei X., Ding M., Liang X., Zhang B., Tan X., Zheng Z. Mahuang Fuzi Xixin decoction ameliorates allergic rhinitis and repairs the airway epithelial barrier by modulating the lung microbiota dysbiosis. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2023;14, article 1206454 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1206454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen X., Chen Y., Xie S., et al. The mechanism of Renshen-Fuzi herb pair for treating heart failure-Integrating a cardiovascular pharmacological assessment with serum metabolomics. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2022;13, article 995796 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.995796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Q., Qie Q., Shang E., Aixia J., Jiao Z., Hu Y. Detoxification mechanism of Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata combined with Saposhnikovia divaricata based on metabolic enzymes in liver. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research . 2022;33(5):1086–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng W.-W., Li W., Li J.-S., et al. The effects of Rhizoma Zingiberis on pharmacokinetics of six Aconitum alkaloids in herb couple of Radix Aconiti Lateralis−Rhizoma Zingiberis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;148(2):579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Z. Y., Wei X. Y., Qiu Z. D., et al. Compatibility of Fuzi and ginseng significantly increase the exposure of aconitines. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2022;13, article 883898 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.883898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ren M., Song S., Liang D., Hou W., Tan X., Luo J. Comparative tissue distribution and excretion study of alkaloids from Herba Ephedrae-Radix Aconiti Lateralis extracts in rats. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis . 2017;134:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y., Li Y., Zhang P., et al. Sensitive UHPLC-MS/MS quantitation and pharmacokinetic comparisons of multiple alkaloids from Fuzi- Beimu and single herb aqueous extracts following oral delivery in rats. Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences . 2017;1058:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiaojun L., Qinglin G., Jiahao L., et al. Postmortem redistribution of aconitine, mesaconitine, hypaconitine and their metabolites in poisoned rabbits. Forensic Science and Technology . 2023;48(3):235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Q., Meng P., Wang H., Dong X., Tan G. Pharmacokinetics of monoester-diterpenoid alkaloids in myocardial infarction and normal rats after oral administration of Sini decoction by microdialysis combined with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Biomedical Chromatography . 2019;33(1, article e4406) doi: 10.1002/bmc.4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou J., Cheng C., Ma L., et al. Investigating the interactions of benzoylaconine and benzoylhypacoitine with human serum albumin: experimental studies and computer calculations. Journal of Molecular Structure . 2023;1294, article 136497 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.136497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ye L., Yang X. S., Lu L. L., et al. Monoester-diterpene Aconitum alkaloid metabolism in human liver microsomes: predominant role of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5. Monoester-DiterpeneAconitumAlkaloid Metabolism in Human Liver Microsomes: Predominant Role of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2013;2013:24. doi: 10.1155/2013/941093.941093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang F., Tang M. H., Chen L. J., et al. Simultaneous quantitation of aconitine, mesaconitine, hypaconitine, benzoylaconine, benzoylmesaconine and benzoylhypaconine in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and pharmacokinetics evaluation of "SHEN-FU" injectable powder. Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences . 2008;873(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J., Li Q., Liu R., Yin Y., Chen X., Bi K. Enrichment and purification of six Aconitum alkaloids from Aconiti kusnezoffii radix by macroporous resins and quantification by HPLC-MS. Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences . 2014;960:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang H., Wu Q., Li W., et al. Absorption and metabolism of three monoester-diterpenoid alkaloids in Aconitum carmichaeli after oral administration to rats by HPLC-MS. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;154(3):645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bazoukis G., Stavrakis S., Armoundas A. A. Vagus nerve stimulation and inflammation in cardiovascular disease: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American Heart Association . 2023;12(19, article e030539) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.030539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ridker P. M., Libby P., MacFadyen J. G., et al. Modulation of the interleukin-6 signalling pathway and incidence rates of atherosclerotic events and all-cause mortality: analyses from the Canakinumab anti-inflammatory thrombosis outcomes study (CANTOS) European Heart Journal . 2018;39(38):3499–3507. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang Y.-F., He F., Cui H., et al. Systematic investigation on the distribution of four hidden toxic Aconitum alkaloids in commonly used Aconitum herbs and their acute toxicity. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis . 2022;208, article 114471 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang K., Liu Y., Lin X., Yang J., Wu C. Assessment of reproductive toxicity and genotoxicity of Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata and its processed products in male mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2021;275, article 114102 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin L., Wang Y., Shao S., et al. Herb-drug interaction between Shaoyao-Gancao-Fuzi decoction and tofacitinib via CYP450 enzymes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2022;295 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xue Z., Zhuo L., Zhang B., et al. Untargeted metabolomics reveals the combination effects and mechanisms of Huangqi-fuzi herb-pair against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2023;305, article 116109 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.116109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xian S., Yang Z., Lee J., et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical study on the efficacy and safety of Shenmai injection in patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;186:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang C., Zheng Y., Chen T., Wang S., Xu M. The utility of traditional Chinese medicine (Shenmai) in the cardiac rehabilitation after coronary artery bypass grafting: a single-center randomized clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine . 2019;47, article 102203 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma R. G., Wang C. X., Shen Y. H., Wang Z. Q., Ma J. H., Huang L. S. Effect of Shenmai injection (参麦注射液) on ventricular diastolic function in patients with chronic heart failure: an assessment by tissue Doppler imaging. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine . 2010;16(2):173–175. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu X., Li H., Song X., et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics studies of benzoylhypaconine, benzoylmesaconine, benzoylaconine and hypaconitine in rats by LC-MS method after administration of Radix Aconiti Lateralis Praeparata extract and Dahuang Fuzi Decoction. Biomedical Chromatography . 2014;28(7):966–973. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this review are from previously reported studies and datasets, which have been cited. The processed data are available from the corresponding author upon request.