Summary

Introduction

Ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia enhances pain control, patient outcomes and lowers healthcare costs. However, teaching this skill effectively presents challenges with current training methods. Simulation‐based medical education offers advantages over traditional methods. However, the use of instructional design features in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training has not been defined. This systematic review aimed to identify and evaluate the prevalence of various instructional design features in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training and their correlation with learning outcomes using a modified Kirkpatrick model.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted including studies from inception to August 2024. Eligibility criteria included randomised controlled trials; controlled before‐and‐after studies; and other experimental designs focusing on ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training. Data extraction included study characteristics; simulation modalities; instructional design features; and outcomes.

Results

Of the 2023 articles identified, 62 met inclusion criteria. Common simulation modalities included live‐model scanning and gel phantom models. Instructional design features such as the presence of expert instructors, repetitive practice and multiple learning strategies were prevalent, showing significant improvements across multiple outcome levels. However, fewer studies assessed behaviour (Kirkpatrick level 3) and patient outcomes (Kirkpatrick level 4).

Discussion

Ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training incorporating specific instructional design features enhances educational outcome; this was particularly evident at lower Kirkpatrick levels. Optimal combinations of instructional design features for higher‐level outcomes (Kirkpatrick levels 3 and 4) remain unclear. Future research should standardise outcome measurements and isolate individual instructional design features to better understand their impact on clinical practice and patient safety.

Keywords: instructional design features, simulation, systematic review, ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia

Introduction

Ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia is a technique used to enhance pain control, improve postoperative morbidity and mortality, and lower healthcare expenditures [1]. It requires thorough understanding of sono‐anatomy, excellent hand‐eye co‐ordination and recognition of proper local anaesthetic deposition at the target structure [1]. Lack of effective education and training interventions are common barriers to the consistent provision of ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia [2, 3, 4, 5]. Previous systematic reviews on ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia show that simulation‐based training improves knowledge, behaviour and patient outcomes compared with traditional methods (e.g. didactic teaching and shadowing) [6, 7, 8]. Despite the benefits of simulation‐based training in this field, there is a knowledge gap regarding the relative merits of various instructional design features and limited use of design feature guidelines in current simulation training curricula [9].

Instructional design features are components and principles, based on learning theories and models that are used to create effective and engaging educational experiences [9]. Educational interventions guided by these features have been applied and evaluated successfully for both technical and non‐technical skills in multiple specialties [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Cook et al. reviewed instructional design features in technology‐enhanced simulation training and found that different features can influence learning outcomes [15]. Given the growing prominence of competency‐based medical education and the expanding application of simulation in anaesthesia, synthesising the current instructional design features within the current ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation literature can help guide future evidence‐based educational interventions.

We aimed to identify and evaluate various instructional design features (adapted from Cook et al. [15] and Barry Issenberg et al. [16]) for ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation‐based training. We expanded the instructional design features in these studies to include: simulator‐type (e.g. virtual reality, augmented reality, manikin models, cadaver models, meat models, etc.); use of cognitive task analysis; presence of an expert instructor; and presence of technology augmentation (e.g. haptic feedback and eye‐tracking) [15, 17]. Based on the framework of a modified Kirkpatrick model, we aimed to ascertain which instructional design features were present when a simulated ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia learning outcome was achieved.

Methods

This review was conducted and reported in accordance with AMSTAR 2 standards and the PRISMA 2020 checklist [18, 19].

An experienced information specialist performed the literature search, which included electronic databases of MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and CINAHL (online Supporting Information Appendix S1). We included studies published in English from database inception until August 2024. We also searched references cited in the final selected studies for eligibility. Covidence data management software (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Deerfield, IL, USA) was used for screening and data extraction.

We included randomised controlled trials (cluster, parallel, factorial and crossover); controlled before‐and‐after studies; interrupted time series; and studies with historical controls. Our focus was on studies using simulated education for training healthcare providers in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia. A simulator was defined as an educational tool or modality that allows learners to interact with and mimic certain components of clinical care without direct patient exposure for educational purposes [20]. The studies could include the following types of simulation: part‐task trainers; meat phantom models; gel phantom models; cadaver models; extended reality (augmented reality, virtual reality, mixed reality); screen‐based educational modules; or high‐fidelity manikins.

All interventions involved ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training with one or more of 15 instructional design features (available in online Supporting Information Table S1). Studies assessed in either simulated or clinical settings were included. Studies involving other disciplines, such as dentistry or veterinary medicine and those that did not involve ultrasound, simulated education or which focused solely on the technical development of the simulators were not reviewed. We included healthcare providers from various disciplines and training stages, including staff physicians; postgraduate trainees (residents and fellows); and medical students.

The included studies all investigated an outcome based on a modified Kirkpatrick model at four levels. Level 1 (reaction) assesses learners' perceptions of the educational intervention, including their satisfaction and confidence in performing skills. Level 2 (learning) evaluates knowledge acquisition, skills and attitudes (includes knowledge assessments; time required to complete tasks; process skills measured by checklists and rating scales; and the quality of the learners' performance). Level 3 (behaviour) examines behavioural changes in the professional setting, such as the transfer of skills to clinical practice (includes the time to complete procedures and procedural proficiency, involving patients or volunteers). Level 4 (results) measures the outcomes of learners' actions, such as patient outcomes and the success of nerve blocks.

To ensure consistency and reliability among assessors, we performed a pilot test of the eligibility criteria involving all reviewers, using 20 studies from the identified titles. This pilot exercise allowed us to refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria and promote consistency and reliability among assessors. Following this, reviewers conducted duplicate screenings of the remaining titles and abstracts independently. Three reviewers (PS, TW and IM) evaluated the identified studies' titles and abstracts independently to determine their inclusion eligibility. In cases of disagreement, these discrepancies were resolved through consensus or by a third author. Full‐text articles meeting inclusion criteria were reviewed independently in duplicate by the same three reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through consensus or consultation with a third author.

Data extraction was carried out using a predefined, standardised template (online Supporting Information Appendix S2) encompassing the following elements: identification details; study particulars; study design; description of the intervention and control; instructional design features; outcomes; and study quality. Data extraction was performed independently and in duplicate by three reviewers (PS, TW and IM). Disagreements were resolved by consensus and with a third reviewer if needed.

A risk of bias assessment was performed in duplicate by the three reviewers using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 [21] and ROBINS‐I [22] tools for randomised and non‐randomised trials, respectively. The quality of the medical education component was assessed using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument [23]. Disagreements at each stage were resolved through consensus and, if necessary, with a third reviewer.

Data were summarised and synthesised using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation Inc, Redmond, WA, USA). A meta‐analysis was not performed due to the heterogeneity of study design and outcome measures. Instead, a narrative summary was conducted.

Results

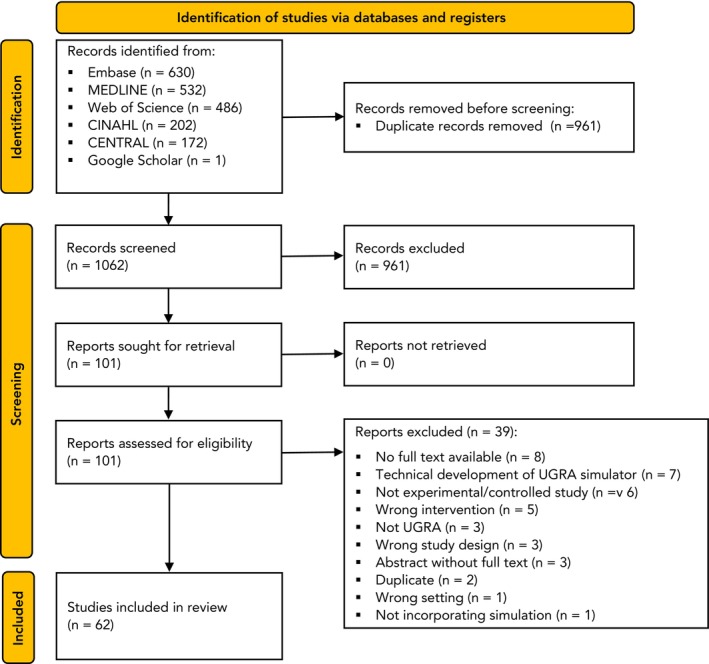

The initial literature search identified 2023 articles. After conducting title screening and removing duplicates, 1062 articles remained for abstract review, of which 101 were relevant for full‐text screening. Following a thorough full‐text assessment, 62 articles met our inclusion criteria and were subjected to further analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. USGA, ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia.

The included articles were published between November 2004 and June 2024. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 30), followed by the European Union (n = 8) and Canada (n = 7) All but one of the studies were single‐centre [24], and the most common setting was in simulation centres or similar environments (n = 45), followed by classrooms and operating theatres (n = 2 each). Table 1 provides a summary of the study participants, study designs, simulation modalities and type of ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Identifier | No. of studies (participants) | |

|---|---|---|

| Study participants* | Physicians in postgraduate training specialty (anaesthesia) | 34 (883) |

| Physicians in practice (anaesthesia) | 20 (603) | |

| Physicians in postgraduate training specialty (emergency medicine) | 8 (117) | |

| Physicians in practice (emergency medicine) | 5 (121) | |

| Physicians in postgraduate training specialty (other) | 2 (42) | |

| Physicians in practice (other) | 4 (82) | |

| Medical student | 14 (526) | |

| Other/unclear | 6 (212) | |

| Study type | Randomised controlled trial | 24 (744) |

| Crossover randomised controlled trials | 6 (154) | |

| Non‐randomised controlled trial (controlled before‐and‐after) | 26 (711) | |

| Non‐randomised controlled trial (interrupted time series) | 4 (94) | |

| Non‐randomised controlled trial (other) | 2 (59) | |

| Type of ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia † | Peripheral nerve block (single shot) | 43 (1272) |

| Ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia training (basic ultrasound and needling) | 17 (517) | |

| Ultrasound‐assisted neuraxial (landmark) | 2 (66) | |

| Peripheral nerve block (continuous) | 2 (77) | |

| Ultrasound‐guided spinal | 1 (30) | |

| Ultrasound‐guided epidural | 1 (26) | |

| Total time learning; h | ≤ 4 | 44 (1280) |

| 4–24 | 8 (247) | |

| > 24 | 10 (235) |

Studies may have multiple types of participants.

Multiple types of ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia may be investigated per study.

The modalities utilised most commonly were screen‐based educational teaching modules (n = 23); live‐model scanning (n = 22); gel phantom (n = 22); and meat phantom models (n = 17). As per our modified Kirkpatrick model, most studies evaluated skill outcomes (Kirkpatrick level 2). Two studies investigated behavioural outcomes (Kirkpatrick level 3) and 13 studies evaluated patient outcomes (Kirkpatrick level 4) with seven showing statistically significant improvement following simulation teaching. Table 2 provides a summary of simulation modalities utilised and the Kirkpatrick outcome levels evaluated across studies.

Table 2.

Summary of simulator modalities and outcomes.

| Identifier | No. of studies (participants) | No. of studies showing improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulator modality* | Part‐task trainers | 10 (229) | ‐ |

| Screen‐based educational teaching modules | 23 (698) | ||

| Gel phantom models | 22 (663) | ‐ | |

| Live‐model scanning | 22 (651) | ‐ | |

| Meat phantom models | 17 (558) | ||

| Cadaver models | 14 (419) | ‐ | |

| High‐fidelity manikins | 7 (177) | ‐ | |

| Virtual reality | 3 (77) | ‐ | |

| Other | 3 (78) | ‐ | |

| Outcomes † | |||

| Kirkpatrick level 1 | Satisfaction | 20 (572) | ‐ |

| Confidence | 16 (494) | ‐ | |

| Kirkpatrick level 2 | Knowledge | 14 (450) | 13 |

| Skill: time | 24 (669) | 18 | |

| Skill: process | 29 (733) | 23 | |

| Skill: product | 20 (641) | 16 | |

| Kirkpatrick level 3 | Behaviour: time | 1 (50) | 1 |

| Behaviour: process | 2 (58) | 1 | |

| Kirkpatrick level 4 | Patient effects | 13 (344) | 7 |

Multiple instructional design features could be used in each study.

Multiple outcomes may have been investigated in each study.

The presence of an expert instructor during simulation training, repetitive practice and multiple learning strategies were the instructional design features used most commonly across all Kirkpatrick levels, with many studies showing statistically significant improvements when these features were utilised. Table 3 provides a summary of instructional design features found across different Kirkpatrick level outcomes.

Table 3.

Summary of instructional design features across Kirkpatrick level outcomes.

| Instructional design † | Total no. of studies (no. of studies with statistically significant improvement p < 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirkpatrick level 1 | Kirkpatrick level 2 | Kirkpatrick level 3 | Kirkpatrick level 4 | All studies | |

| Satisfaction and confidence* | Knowledge and skills | Behaviours | Patient effects | ||

| Multiple learning strategies | 21 | 40 (32) | 2 (1) | 10 (6) | 49 |

| Expert instructor present | 24 | 39 (32) | 2 (1) | 10 (5) | 47 |

| Repetitive practice | 23 | 44 (33) | 2 (1) | 10 (5) | 47 |

| Feedback | 14 | 22 (17) | 2 (1) | 5 (4) | 28 |

| Group practice | 10 | 15 (12) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | 17 |

| Clinical diversity | 13 | 13 (12) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 17 |

| Technology‐augmented | 6 | 16 (13) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 16 |

| Curricular integration | 7 | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 10 |

| Distributed practice | 6 | 9 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 10 |

| Mastery learning | 4 | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 7 |

| Individualised learning | 2 | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 5 |

| Cognitive task analysis | 1 | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 |

| Range of task difficulty | 3 | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 |

Not compared with a control.

Multiple instructional designs may have been incorporated in each study.

Two randomised controlled trials isolated specific instructional design features. Niazi et al. compared the effectiveness of a 1‐hour simulation that utilised multiple learning strategies (didactics plus simulation) and repetitive practice to didactics alone on a part‐task trainer, and showed a significant increase in self‐reported block success [25]. Cai et al. showed that an artificial intelligence‐assisted nerve identification system for simulated education decreased patient complication rates compared with traditional teaching on part‐task trainers [26].

Several studies controlled for technology augmentation. Among these, needle tip tracking was examined as an education tool, with all studies finding significant improvement in skill outcomes [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Various other forms of technology augmentation were also explored in enhancing skill acquisition. These included a screen‐based system for ultrasound probe and hand viewing [34]; head‐mounted ultrasound display [35]; virtual reality devices like the Oculus® Rift S (Lenovo, Beijing, China) [36]; piezoelectric buzzer feedback system [37]; an onboard electronic tutorial [38]; and artificial intelligence‐assisted nerve identification system [26].

Only two studies evaluated Kirkpatrick level 3 outcomes. One used a combined checklist and global rating scale to assess process behaviours; however, it was discontinued due to technological issues and trainees reported that the virtual reality simulator differentiated upper extremity surface anatomy poorly [39]. Dang et al. assessed both time and process behaviours during real clinical encounters to compare training on human cadavers vs. a part‐task trainer [40].

Of the 13 studies measuring Kirkpatrick level 4 outcomes, seven assessed the number of blocks practitioners performed in post‐intervention practice through surveys and chart reviews [41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Three of the thirteen studies were randomised controlled trials, of which two saw significant improvements in various patient outcomes including error rate in real clinical scenarios [40], patient complications such as pain during injection [26] and self‐reported success rate [25]. Summaries of studies investigating Kirkpatrick levels 1–2 and 3–4 outcomes are available in online Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

For randomised controlled trials, one study was judged to be at high risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions and missing outcome data [39], while all other randomised controlled trials were judged as being low to medium risk (online Supporting Information Table S4). For non‐randomised controlled trials, one study [41] was judged to be at critical risk due to missing data, while five [48, 49, 50, 51, 52] were judged to be at serious risk due to a variety of reasons including missing information (online Supporting Information Table S5).

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument assesses the methodological quality of medical education studies, and consists of 10 items in six domains, with total scores ranging from 5 to 18. The mean (SD) score for the studies included here is 12.8 (1.7). A summary of the number of studies evaluated within each category of this scoring instrument is provided in online Supporting Information Table S6.

Discussion

Our comprehensive review found that many instructional design features and simulation modalities were utilised for ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia education and training to improve various outcomes. Our findings may help to inform future research or curriculum design by choosing the optimal combination of simulation modalities and design features for achieving specific outcomes.

When similar methods were applied in a review of simulated laparoscopic surgery education, all simulations had a positive effect on skills time and skills process [14]. Similarly, in our investigation, most studies showed statistically significant improvements in Kirkpatrick level 2 outcomes. However, fewer studies assessing Kirkpatrick level 3 and 4 outcomes showed a statistically significant improvement, consistent with a previous systematic review [53]. This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that lower Kirkpatrick outcome levels can be assessed without patient safety risks as they involve simulators only, while higher Kirkpatrick outcome levels carry logistical difficulties, such as observing clinical performance and quantifying and tracking patient outcomes. We found a limited number of studies in which a single instructional design feature was isolated between groups. This limitation restricted our ability to aggregate similar studies or draw definitive conclusions about any specific instructional design features.

Our review and existing literature highlight the prevalence of certain instructional design features in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation‐based medical education. The most common instructional design features identified included expert instructor presence; repetitive practice; multiple learning strategies; and feedback; this is consistent with previous work [15, 16]. These instructional design features are simple to implement and consistent with the current teaching practices in medicine. Consequently, more resource‐intensive instructional design features, such as individualised learning plans, mastery of learning, cognitive task analysis and range of task difficulty were utilised less commonly.

Most studies incorporated multiple learning strategies in the form of didactic and screen‐based educational modules along with simulation training. Literature suggests that procedural‐based medical teaching encompasses both cognitive and psychomotor phases, progressing through learning, seeing, practising and proving stages [54]. Didactic instruction or direct shadowing can help address the learning and seeing objectives, while simulators may offer a platform to practice and show competency in skills. Further supporting the effectiveness of multiple learning strategies, Cook et al. found that multiple learning strategies was the only instructional design feature with a significantly positive pooled effect on Kirkpatrick level 4 patient outcomes (0.53, p < 0.001) [15]. We identified several studies that assessed patient effects while incorporating multiple learning strategies with significant improvement following simulation use [25, 26, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 52, 55, 56]. However, unlike Niazi et al. [34], these studies did not isolate for multiple learning strategies [25, 26, 43, 44, 46, 56].

Some studies controlled for different forms of feedback. Farjad Sultan et al. found that for skill acquisition, providing feedback on the procedural skill (involving identification and correction of errors and advice on how to avoid them) was superior to feedback on the results (involving imaging, needling, performance time and number of needle passes) [57]. Lerman et al. found that LED light and piezoelectric buzzer feedback were superior to voice feedback and no feedback in visualising and reaching the simulated target nerve [37]. These controlled studies suggest that feedback is a valuable instructional design feature, as it focuses on error identification, which can be enhanced by technology and expert recommendations.

Very few studies evaluated Kirkpatrick level 3 outcomes, with only Dang et al. completed as originally designed [40]. A notable limitation of this study was that a combined checklist and global rating scale was not used in the assessment of process behaviours. It is unclear why studies investigating Kirkpatrick level 3 outcomes were even less common than Kirkpatrick level 4 outcomes involving patient effects. One possible reason could be the restrictive definition of Kirkpatrick level outcomes, which limits the identification of outcomes specifically investigating the process or time required to perform a skill on a patient, rather than the patient outcomes directly. Studies involving patients carry logistical difficulties and are resource‐intensive, leading authors to prioritise investigating the higher Kirkpatrick level 4 outcomes as opposed to behavioural process or skill.

The findings of our review may help inform future curriculum development in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation training. When developing training modules with simulators, it is beneficial for instructors to actively and deliberately determine which instructional design features to include. This marks the transition from a trial‐and‐error approach to evidence‐based educational practices. An evidence‐based approach to instructional design feature selection can optimise and streamline the training process; contribute to creating targeted training programmes; ensure that the educational interventions are grounded in proven methodologies; and potentially contribute to better clinical performance and patient care.

Conducting a meta‐analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of study design (randomised and non‐randomised controlled trials); outcomes; simulation modalities; instructional design features; and methods of assessment. Additionally, most studies did not control for individual instructional design features, confounding any inferences about the incorporation or effect of any single feature in simulation‐based medical education. With the increasing number of randomised controlled trials published in ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia simulation, a meta‐analysis may become feasible to address common questions for educators (e.g. the use of high vs. low fidelity simulators, structured feedback vs. no/unstructured feedback and the usefulness of technology augmentation) and to inform the incorporation of instructional design features in future studies and simulation curricula.

Future research should incorporate standardised outcome measurements to enable between study comparisons and directly isolate and compare instructional design features to help better understand their impact. Addressing these gaps and standardising methodologies will advance ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia training, offer future recommendations and improve clinical practice and patient safety.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Literature search strategy.

Appendix S2. Extraction template.

Table S1. Instructional design features.

Table S2. Studies with Kirkpatrick level 1 and 2 outcomes.

Table S3. Studies investigating Kirkpatrick level 3 and 4 outcomes.

Table S4. Risk of Bias summary randomised controlled trials.

Table S5. Risk of Bias summary non‐randomised controlled trials.

Table S6. Breakdown of ‘A Modified Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument’ scores.

Acknowledgements

Study protocol CRD42023473306 was registered on PROSPERO. SB and YG were supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anaesthesia Alternate Funds Association and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa. No data or statistical code is available. No external funding or competing interests declared.

1 Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

2 Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada

4 Diving and Hyperbaric Unit, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Anaesthesiology, Clinical Pharmacology, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

5 Library Services, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada

References

- 1. Wolmarans M, Albrecht E. Regional anesthesia in the emergency department outside the operating theatre. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 2023; 36: 447–451. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green M, Tariq R, Green P. Improving patient safety through simulation training in anesthesiology: where are we? Anesthesiol Res Pract 2016; 2016. Epub 1 February: 4237523. 10.1155/2016/4237523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai TY, Yeh HT, Liu YC, et al. Trends of regional anesthesia studies in emergency medicine: an observational study of published articles. West J Emerg Med 2023; 22: 57552. 10.5811/2022/57552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hammond M, Law V, de Launay KQ, et al. Using implementation science to promote the use of the fascia iliaca blocks in hip fracture care. Can J Anesth 2024; 71: 741–750. 10.1007/s12630-023-02665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sekhavati P, Ramlogan R, Bailey JG, Busse JW, Boet S, Gu Y. Simulation‐based ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia education: a national survey of Canadian anesthesiology residency training programs. Can J Anesth 2024. Epub 6 August. 10.1007/s12630-024-02818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim H‐Y, Kim E‐Y. Effects of medical education program using virtual reality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 3895. 10.3390/ijerph20053895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Curran VR, Xu X, Aydin MY, Meruvia‐Pastor O. Use of extended reality in medical education: an integrative review. Med Sci Educ 2023; 33: 275–286. 10.1007/s40670-022-01698-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dhar E, Upadhyay U, Huang Y, et al. A scoping review to assess the effects of virtual reality in medical education and clinical care. Digit Health 2023; 9: 20552076231158022. 10.1177/20552076231158022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Melo BCP, Falbo AR, Souza ES, Muijtjens AMM, van Merriënboer JJG, van der Vleuten CPM. The limited use of instructional design guidelines in healthcare simulation scenarios: an expert appraisal. Adv Simul 2022; 7: 30. 10.1186/s41077-022-00228-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Melo BCP, Van Der Vleuten CPM, Muijtjens AMM, et al. Effects of an in situ instructional design based postpartum hemorrhage simulation training on patient outcomes: an uncontrolled before‐and‐after study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021; 34: 245–252. 10.1080/14767058.2019.1606195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frithioff A, Frendø M, Mikkelsen PT, Sørensen MS, Andersen SAW. Cochlear implantation: exploring the effects of 3D stereovision in a digital microscope for virtual reality simulation training – a randomized controlled trial. Cochlear Implants Int 2022; 23: 80–86. 10.1080/14670100.2021.1997026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roth M, Daas L, MacKenzie CR, et al. Development and assessment of a simulator for in vivo confocal microscopy in fungal and acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Eye Res 2020; 45: 1484–1489. 10.1080/02713683.2020.1772830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alhazmi MS, Butler CW, Junghans BM. Does the virtual refractor patient‐simulator improve student competency when refracting in the consulting room? Clin Exp Optom 2018; 101: 771–777. 10.1111/cxo.12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zendejas B, Brydges R, Hamstra SJ, Cook DA. State of the evidence on simulation‐based training for laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 586–593. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cook DA, Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation‐based education: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Med Teach 2013; 35: e867–e898. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barry Issenberg S, Mcgaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high‐fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005; 27: 10–28. 10.1080/01421590500046924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Edwards TC, Coombs AW, Szyszka B, Logishetty K, Cobb JP. Cognitive task analysis‐based training in surgery: a meta‐analysis. BJS Open 2021; 5: zrab122. 10.1093/bjsopen/zrab122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non‐randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017; 358: j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, et al. Technology‐enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA 2011; 306: 978–988. 10.1001/jama.2011.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019; 366: l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al Asmri M, Haque MS, Parle J. A Modified Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MMERSQI) developed by Delphi consensus. BMC Med Educ 2023; 23: 63. 10.1186/s12909-023-04033-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burckett‐St Laurent DA, Cunningham MS, Abbas S, et al. Teaching ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia remotely: a feasibility study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016; 60: 995–1002. 10.1111/aas.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niazi AU, Haldipur N, Prasad AG, Chan VW. Ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia performance in the early learning period: effect of simulation training. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012; 37: 51–54. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31823dc340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cai N, Wang G, Xu L, et al. Examining the impact perceptual learning artificial‐intelligence‐based on the incidence of paresthesia when performing the ultrasound‐guided popliteal sciatic block: simulation‐based randomized study. BMC Anesthesiol 2022; 22: 392. 10.1186/s12871-022-01937-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gupta RK, Lane J, Allen B, et al. Improving needle visualization by novice residents during an in‐plane ultrasound nerve block simulation using an in‐plane multiangle needle guide. Pain Med 2013; 14: 1600–1607. 10.1111/pme.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kasine T, Romundstad L, Rosseland LA, et al. Needle tip tracking for ultrasound‐guided peripheral nerve block procedures – an observer blinded, randomised, controlled, crossover study on a phantom model. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2019; 63: 1055–1062. 10.1111/aas.13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKendrick M, Sadler A, Taylor A, et al. The effect of an ultrasound‐activated needle tip tracker needle on the performance of sciatic nerve block on a soft embalmed Thiel cadaver. Anaesthesia 2021; 76: 209–217. 10.1111/anae.15211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McLeod GA, McKendrick M, Taylor A, et al. An initial evaluation of the effect of a novel regional block needle with tip‐tracking technology on the novice performance of cadaveric ultrasound‐guided sciatic nerve block. Anaesthesia 2020; 75: 80–88. 10.1111/anae.14851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McVicar J, Niazi AU, Murgatroyd H, Chin KJ, Chan VW. Novice performance of ultrasound‐guided needling skills: effect of a needle guidance system. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40: 150–153. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Geffen G‐J, Mulder J, Gielen M, van Egmond J, Scheffer GJ, Bruhn J. A needle guidance device compared to free hand technique in an ultrasound‐guided interventional task using a phantom. Anaesthesia 2008; 63: 986–990. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Whittaker S, Lethbridge G, Kim C, Keon Cohen Z, Ng I. An ultrasound needle insertion guide in a porcine phantom model. Anaesthesia 2013; 68: 826–829. 10.1111/anae.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Das Adhikary S, Karanzalis D, Liu W‐MR, et al. A prospective randomized study to evaluate a new learning tool for ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia. Pain Med 2017; 18: 856–865. 10.1093/pm/pnw287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Przkora R, McGrady W, Vasilopoulos T, et al. Evaluation of the head‐mounted display for ultrasound‐guided peripheral nerve blocks in simulated regional anesthesia. Pain Med 2015; 16: 2192–2194. 10.1111/pme.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chuan A, Bogdanovych A, Moran B, et al. Using virtual reality to teach ultrasound‐guided needling skills for regional anaesthesia: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Anesth 2024; 97: 111535. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2024.111535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lerman IR, Souzdalnitski D, Halaszynski T, Dai F, Guirguis M, Narouze SN. Ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia simulation and trainee performance. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag 2014; 18: 110–117. 10.1053/j.trap.2015.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wegener JT, van Doorn CT, Eshuis JH, Hollmann MW, Preckel B, Stevens MF. Value of an electronic tutorial for image interpretation in ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013; 38: 44–49. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31827910fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Sullivan O, Iohom G, O'Donnell BD, Shorten GD. The effect of simulation‐based training on initial performance of ultrasound‐guided axillary brachial plexus blockade in a clinical setting – a pilot study. BMC Anesthesiol 2014; 14: 110. 10.1186/1471-2253-14-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dang D, Kamal M, Kumar M, Paliwal B, Nayyar A, Bhatia P, Singariya G. Comparison of human cadaver and blue phantom for teaching ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia to novice postgraduate students of anesthesiology: a randomized controlled trial. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2024; 40: 276–282. 10.4103/joacp.joacp_234_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walsh CD, Ma IWY, Eyre AJ, et al. Implementing ultrasound‐guided nerve blocks in the emergency department: a low‐cost, low‐fidelity training approach. AEM Educ Train 2023; 7: e10912. 10.1002/aet2.10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hocking G, McIntyre O. Achieving change in practice by using unembalmed cadavers to teach ultrasound‐guided regional anaesthesia. Ultrasound 2011; 19: 31–35. 10.1258/ult.2010.010040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim TE, Ganaway T, Harrison TK, Howard SK, Shum C, Kuo A, Mariano ER. Implementation of clinical practice changes by experienced anesthesiologists after simulation‐based ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia training. Korean J Anesthesiol 2017; 70: 318–326. 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.3.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O'Driscoll L. Implementation of an education program for an ultrasound‐guided liposomal bupivacaine transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block protocol for open abdominal procedures. AANA J 2018; 86: 479–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Udani AD, Harrison TK, Mariano ER, et al. Comparative‐effectiveness of simulation‐based deliberate practice versus self‐guided practice on resident anesthesiologists' acquisition of ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia skills. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41: 151–157. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mariano ER, Harrison TK, Kim TE, et al. Evaluation of a standardized program for training practicing anesthesiologists in ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia skills. J Ultrasound Med 2015; 34: 1883–1893. 10.7863/ultra.14.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brouillette MA, Aidoo AJ, Hondras MA, et al. Regional anesthesia training model for resource‐limited settings: a prospective single‐center observational study with pre‐post evaluations. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2020; 45: 528–535. 10.1136/rapm-2020-101550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lim MW, Burt G, Rutter SV. Use of three‐dimensional animation for regional anaesthesia teaching: application to interscalene brachial plexus blockade. Br J Anaesth 2005; 94: 372–377. 10.1093/bja/aei060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amini R, Camacho LD, Valenzuela J, et al. Cadaver models in residency training for uncommonly encountered ultrasound‐guided procedures. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2019; 6: 2382120519885638. 10.1177/2382120519885638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Paulson CL, Schultz KL, Kim D, Roth KR, Warren HR. Rapid education event: a streamlined approach to ultrasound guided nerve block procedural training. Cureus 2023; 15: e34080. 10.7759/cureus.34080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sites BD, Gallagher JD, Cravero J, et al. The learning curve associated with a simulated ultrasound‐guided interventional task by inexperienced anesthesia residents. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004; 29: 544–548. 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kong B, Zabadayev S, Perese J, et al. Ultrasound‐guided fascia iliaca compartment block simulation training in an emergency medicine residency program. Cureus 2024. Epub 16 January. 10.7759/cureus.52411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen XX, Trivedi V, AlSaflan AA, Todd SC, Tricco AC, McCartney C, Boet S. Ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia simulation training: a systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013; 2017: 741–750. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sawyer T, White M, Zaveri P, et al. Learn, see, practice, prove, do, maintain: an evidence‐based pedagogical framework for procedural skill training in medicine. Acad Med 2015; 90: 1025–1033. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ramachandran A, Montenegro M, Singh M, et al. “Diffusion of innovations”: a feasibility study on the pericapsular nerve group block in the emergency department for hip fractures. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2022; 9: 198–206. 10.15441/ceem.22.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bortman J, Baribeau Y, Jeganathan J, et al. Improving clinical proficiency using a 3‐dimensionally printed and patient‐specific thoracic spine model as a haptic task trainer. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43: 819–824. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Farjad Sultan S, Iohom G, Shorten G. Effect of feedback content on novices' learning ultrasound guided interventional procedures. Minerva Anestesiol 2013; 79: 1269–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Literature search strategy.

Appendix S2. Extraction template.

Table S1. Instructional design features.

Table S2. Studies with Kirkpatrick level 1 and 2 outcomes.

Table S3. Studies investigating Kirkpatrick level 3 and 4 outcomes.

Table S4. Risk of Bias summary randomised controlled trials.

Table S5. Risk of Bias summary non‐randomised controlled trials.

Table S6. Breakdown of ‘A Modified Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument’ scores.