Abstract

Introduction

Randomized phase III trials showed that using trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) in patients with pre-treated metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) conferred survival benefit versus placebo. Here, we investigated the effectiveness and safety of FTD/TPI and sought to identify prognostic factors among the mCRC population in Hong Kong.

Methods

A non-interventional, retrospective, multicenter cohort study enrolled patients with mCRC who received FTD/TPI in seven public hospitals in Hong Kong between 2016 and 2020. Overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint; treatment duration and occurrence of neutropenia were secondary endpoints. We also performed a post hoc analysis to identify factors influencing OS and treatment duration.

Results

Overall, 456 patients were included (median age, 64.0 years; 57.5% men). Approximately half (225/456; 49.3%) had RAS wild-type tumors; the median treatment duration was 12.4 weeks (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.1–13.1). Median OS was 7.59 months (95% CI 7.00–8.21). Overall, 289 (63.4%) patients developed neutropenia of any grade and 159 (34.9%) developed grade ≥ 3 neutropenia. Neutropenia at 1 month occurred in 193 (43.1%) patients. The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia was reported for 42 (9.2%) patients. The development of neutropenia, absolute neutrophil count decrease of ≥ 2 grades in 1 month, absence of liver metastasis, and RAS wild-type status were associated with significantly longer OS and, except for RAS wild-type status (not analyzed), longer treatment duration (p < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Conclusion

Our data show that treatment with FTD/TPI offers survival benefits in patients with refractory mCRC in Hong Kong consistent with randomized controlled trials and other real-world studies. Furthermore, the prognosis in patients receiving FTD/TPI appears to be significantly better in those who develop neutropenia, with RAS wild-type status, or those without liver metastases, despite a higher rate of dose reduction in the real-world setting.

Keywords: FTD/TPI, Metastatic colorectal cancer, Neutropenia, Prognostic factor, Real-world, TAS-102, Trifluridine/tipiracil

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? | |

| Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer in Hong Kong; however, treatment options for metastatic CRC (mCRC) in the third line and beyond are relatively limited. | |

| In randomized controlled trials, trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) has been shown to confer survival benefit versus placebo when administered in patients with pre-treated mCRC. | |

| This was a non-interventional, retrospective, multicenter cohort study in Hong Kong that evaluated the real-world efficacy of FTD/TPI in mCRC and sought to identify prognostic characteristics. | |

| What was learned from the study? | |

| Our study confirmed the effectiveness of FTD/TPI in a real-world setting, with a median overall survival (OS) of 7.59 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 7.00–8.21), consistent with that reported in two landmark randomized phase III trials, and identified RAS wild-type status, the development of neutropenia, and the absence of liver metastases as useful prognostic factors influencing response to FTD/TPI. | |

| Our data show that treatment with FTD/TPI offers survival benefits in patients with refractory mCRC in a real-world setting in Hong Kong, consistent with randomized controlled trials and other real-world studies. |

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is on the rise in Asia, including Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore [1]. In 2020, Asia had the highest proportions of both incidence (52.3%) and mortality (54.2%) of CRC cases worldwide [2]. In Hong Kong, CRC ranks as the second most common cancer with 5087 new cases and 2287 deaths reported in 2020 [3].

Despite the widespread implementation of CRC screening programs, many patients are still diagnosed at an advanced stage. Among Asians and Pacific Islanders diagnosed with CRC, 19.4% present with metastatic disease, which is associated with a dismal 5-year survival rate of only 15.9% [4]. Furthermore, 25–30% of patients with resectable CRC may experience disease recurrence even after receiving adjuvant treatment [5]. Therefore, effective treatment options for metastatic CRC (mCRC), particularly in the later lines of therapy, are crucial.

Treatment choices for mCRC are influenced by several factors, including patient characteristics (e.g., age, performance status, and comorbidities), tumor characteristics (e.g., tumor sidedness and predictive biomarkers), and treatment-related factors (e.g., toxicity and quality of life). Chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment, except in mCRC which is deficient in DNA mismatch repair. Typically, patients receive fluorouracil-based chemotherapy alongside irinotecan or oxaliplatin in the first- and second-line settings. Additionally, biologics such as anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can be integrated with chemotherapy regimens.

Anti-EGFR therapy has shown effectiveness in clinical trials specifically for RAS wild-type mCRC [6]. Treatment options for mCRC in the third line and beyond are relatively less efficacious, with a response rate of 1–31% and progression-free survival (PFS) of 2–5 months [6]. These include trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI; TAS-102; Lonsurf®, Taiho Oncology, Inc.) with or without bevacizumab, regorafenib, fruquintinib, or re-challenge with previously utilized classes of agents. Other treatment options for mCRC with oncologic drivers include encorafenib–cetuximab for BRAF V600E-mutated disease, dual human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) blockade for HER2 amplified disease, sotorasib or adagrasib as monotherapy or in combination with cetuximab or panitumumab for KRAS G12C mutation-positive disease, and immune checkpoint inhibitors for DNA mismatch repair deficient/high microsatellite instability (dMMR/MSI-H) mCRC.

FTD/TPI was approved by health authorities in the USA (2015), Japan (2014), and Europe (2016) as a late-line oral chemotherapy for mCRC [7–9]. FTD, a thymidine-based nucleoside analogue, exerts its cytotoxic effect by its incorporation into DNA, thereby resulting in DNA dysfunction and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation [10]. TPI, a thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor, increases the exposure of FTD when used in combination, which is thought to contribute to the therapeutic efficacy [7]. FTD/TPI also offers a therapeutic avenue for overcoming acquired resistance to fluorouracil, which is susceptible to degradation by DNA glycosylase [10–12].

The approvals for FTD/TPI were based on the results of a phase II trial in Japan, which demonstrated that FTD/TPI was associated with a significantly longer overall survival (OS) than placebo (median, 9.0 vs 6.6 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.56 [95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–0.81]; p = 0.0011) in pre-treated patients with mCRC [13]. Similarly, the international phase III RECOURSE trial reported superior OS results for FTD/TPI over placebo in 800 patients with refractory mCRC who had received ≥ 2 prior standard chemotherapy regimens (median OS, 7.1 vs 5.3 months; HR, 0.68 [95% CI 0.58–0.81]; p < 0.001) [14]. A subgroup analysis of the RECOURSE trial further showed a favorable safety and efficacy profile for FTD/TPI irrespective of age, geographic origin, or RAS status [15]. Specifically targeting an Asian population, the phase III TERRA study conducted in China, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand reported survival benefit with FTD/TPI over placebo (median OS, 7.8 vs 7.1 months; HR, 0.79 [95% CI 0.62–0.99]; p = 0.035) in patients with mCRC refractory or intolerant to standard chemotherapies, regardless of exposure to biologic therapy [16]. Several international guidelines used in Hong Kong, including the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), Pan-Asian adapted ESMO, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, have included FTD/TPI in their recommendations as a late-line treatment option for patients with pre-treated mCRC [6, 17–20]. More recently, the SUNLIGHT study demonstrated improvement in OS of FTD/TPI plus bevacizumab over FTD/TPI alone (median OS, 10.8 vs 7.5 months; HR, 0.61 [95% CI 0.49–0.77]; p < 0.001) without new safety signals [21].

FTD/TPI is generally well tolerated—the most frequently reported adverse event in both RECOURSE and TERRA was neutropenia (grade ≥ 3 neutropenia, 38% and 33%, respectively) [14, 16]. Interestingly, the development of neutropenia was associated with improved OS [22–25]; however, these findings were observed in a clinical trial setting. Given that ethnic diversity exists in response to anticancer therapies [26], it would be pertinent to investigate if these observations hold true in a real-world setting, particularly among patients in Hong Kong.

In this retrospective study, we analyzed patients with mCRC treated with FTD/TPI in Hong Kong. Our objectives were to evaluate the real-world efficacy of FTD/TPI and identify prognostic factors for treatment outcomes. Additionally, we examined the incidence of neutropenia and its potential role as a prognostic indicator.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a retrospective, multicenter cohort study of adult patients with advanced or metastatic CRC who started FTD/TPI between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2020 in seven public hospitals under the Hospital Authority in Hong Kong.

Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years at the initiation of FTD/TPI with a diagnosis of CRC as a primary tumor based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 diagnosis codes of 153 (malignant neoplasm of colon) or 154 (malignant neoplasm of rectum, rectosigmoid junction and anus); or the ICD-10 cause of death codes—C18 (malignant neoplasm of colon), C19 (malignant neoplasm of rectosigmoid junction), or C20 (malignant neoplasm of rectum)—or both.

Patients received FTD/TPI 35 mg/m2 twice daily on days 1–5 and 8–12 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, or decision by the patient or physician [7].

Data Retrieval and Measurement

Clinical data were extracted from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority, which covers 90% of all secondary and tertiary care in the territory [27]. The current report included data from drug dispensation records up to 31 October 2021; survival data were collected to 7 November 2021.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster before any data collection (IRB reference number UW 19-460). In addition, the requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the anonymous nature of the data.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics extracted included age, sex, RAS mutation status, sites of metastases (based on the ICD-9 diagnosis codes of 196–198), absolute neutrophil count (ANC) during treatment, and use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and other antineoplastic drugs prescribed (per British National Formulary Sect. 8.1), if any, during treatment. As RAS mutation status information was not available, the use of cetuximab or panitumumab was used as a proxy to identify RAS wild-type status.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the length of time from the date FTD/TPI was first dispensed (index date) to death from any cause. Secondary endpoints included the occurrence of neutropenia (any occurrence during treatment and ANC grade change at 1 month) and treatment duration (as a surrogate for PFS; defined as [last prescription day] − [index day] + [number of days of supply at last prescription day]). Neutropenia and febrile neutropenia were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03. A post hoc analysis was undertaken to identify factors influencing OS and treatment duration in patient subgroups by RAS status, occurrence of neutropenia, and liver metastasis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Median OS and treatment duration were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between subgroups were evaluated using the log-rank test. Patients lost to follow-up were censored on the basis of the last known contact/visit date within the data period. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R software (version 4.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [28].

Results

Patients

Records from 490 patients treated at seven public hospitals under the Hospital Authority in Hong Kong—Queen Mary Hospital, Prince of Wales Hospital, Princess Margaret Hospital, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital, and United Christian Hospital—between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2020 were screened; 456 patients with mCRC met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age at the initiation of FTD/TPI was 64.0 years, with male patients representing 57.5% of the cohort (262/456). RAS wild-type tumors were present in 49.3% of the patients (225/456). Moreover, 383 patients (84%) had confirmed metastatic disease, with the liver being the most commonly affected site (262/383 patients; 68.4%), followed by the lung (184/383 patients; 48.0%). The majority of patients received FTD/TPI at the third line or beyond (429/456 patients; 94.1%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Trifluridine/tipiracil N = 456 |

|

|---|---|

| Age at index date, median (range), years | 64.0 (34.5–92.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 262 (57.5) |

| Female | 194 (42.5) |

| RAS mutation status, n (%)a | |

| Wild-type | 225 (49.3) |

| Mutation-positive | 231 (50.7) |

| Other concurrent cancer, n (%)b | 20 (4.4) |

| Metastatic sites, n (%) | (n = 383) |

| Liver | 262 (68.4) |

| Lung | 184 (48.0) |

| Peritoneum | 106 (27.7) |

| Bone | 51 (13.3) |

| Brain | 29 (7.6) |

| Other sites | 137 (35.8) |

| Treatment received, n (%) | |

| Trifluridine/tipiracil monotherapy | 428 (93.9) |

| Trifluridine/tipiracil in combination with another therapy | 28 (6.1) |

| Anti-VEGF targeted therapy | 25 |

| Bevacizumab only | 21 |

| Aflibercept only | 2 |

| Bevacizumab followed by aflibercept | 2 |

| Anti-EGFR targeted therapy | 7 |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor | 6 |

| Chemotherapy | 5 |

| Other targeted therapy | 2 |

| Starting dose of trifluridine/tipiracil, median (IQR), mg twice daily | 50 (45–60) |

| Final dose of trifluridine/tipiracil, median (IQR), mg twice daily | 50 (40–55) |

| Number of prior regimens, n (%) | |

| 1 | 27 (5.9) |

| 2 | 125 (27.4) |

| 3 | 130 (28.5) |

| ≥ 4 | 174 (38.2) |

EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, IQR interquartile range, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

aWhere information on RAS mutation status was not available, a history of usage of cetuximab and panitumumab was used as a proxy for RAS wild type

bThere were 20 cases with known or suspected concurrent cancer and 53 cases were excluded because the information was missing or metastatic status was uncertain

FTD/TPI monotherapy was the regimen used for the majority of the cohort (428/456 patients; 93.9%). Combination therapy was provided to 28 patients (6.1%), with anti-VEGF therapy being the predominant addition (25/28 patients; 89.3%). The majority received bevacizumab as the anti-VEGF therapy (23/25 patients; 92%). The median starting dose of FTD/TPI was 50 mg twice daily (IQR, 45–60 mg twice daily).

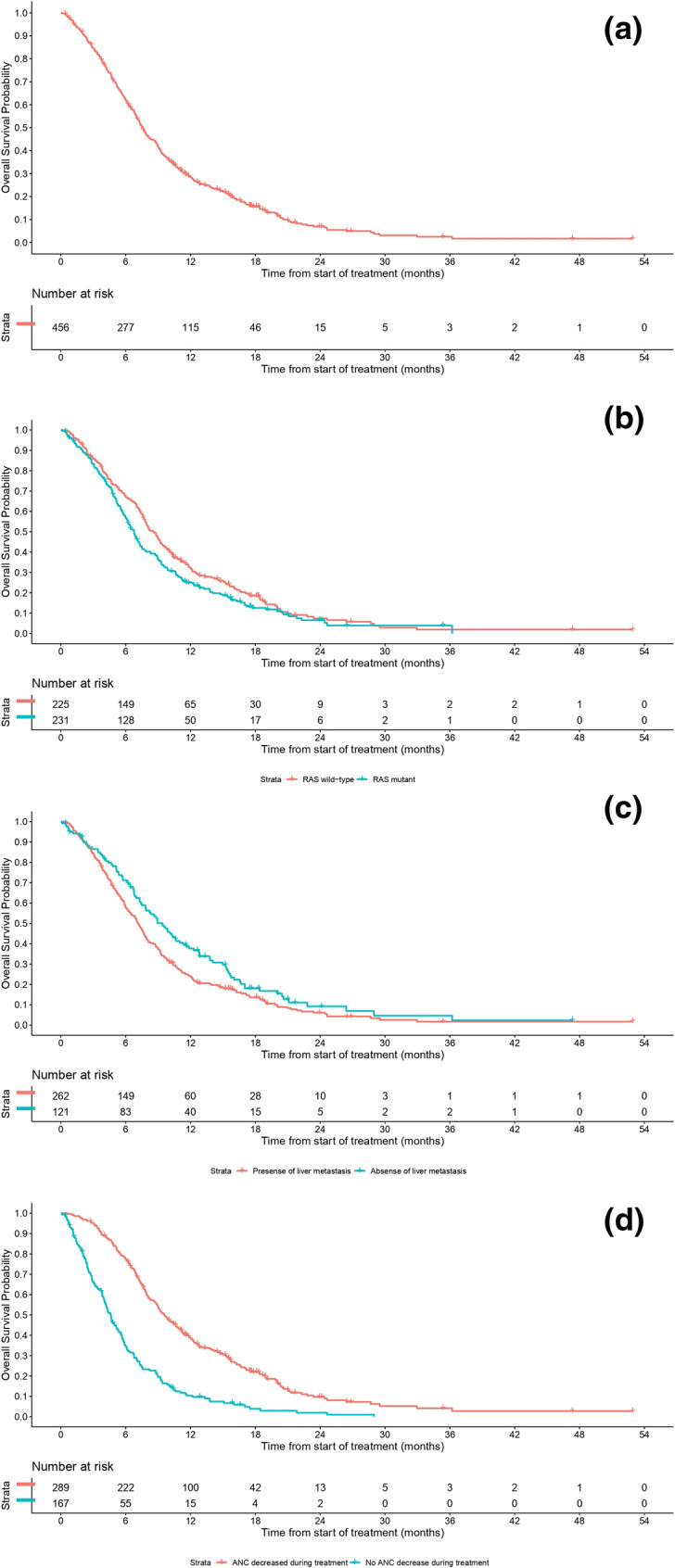

Efficacy

The median OS for the study population was 7.59 months (95% CI 7.00–8.21; Fig. 2a; Table 2). Patients with RAS wild-type tumors had a significantly longer OS compared with those who had RAS mutant-type: median OS of 8.61 months (95% CI 7.69–9.40) versus 6.77 months (95% CI 6.05–7.33) (p = 0.04; Fig. 2b; Table 2). Patients without liver metastases had a longer OS than those with liver metastases: median OS of 9.40 months (95% CI 7.49–11.01) versus 7.13 months (95% CI 6.21–7.79) (p = 0.02; Fig. 2c; Table 2). Patients who experienced neutropenia had a more than two-fold longer OS compared with patients without neutropenia: median OS of 9.56 months (95% CI 8.80–10.74) versus 4.63 months (95% CI 3.98–5.32) (p < 0.001; Fig. 2d; Table 2). In addition, among patients who experienced neutropenia, OS benefit was enhanced in those who had a ≥ 2-grade change versus those who had a < 2-grade change at 1 month: median OS of 10.38 months (95% CI 8.08–11.86) versus 6.77 months (95% CI 5.98–7.59) (p < 0.001; Table 2). Patients who received FTD/TPI in combination with anti-VEGR monoclonal antibody (mAb) had a longer OS than those who received FTD/TPI monotherapy: median OS of 12.02 months (95% CI 4.57–20.01) versus 7.46 months (95% CI 6.90–8.08) (p = 0.06). The sequence of treatment with FTD/TPI and regorafenib also influenced OS; patients who received FTD/TPI followed by regorafenib had a substantially longer median OS versus the reverse sequence: median OS of 15.2 months (95% CI 12.3–17.4) (p < 0.001) versus 7.5 months (95% CI 6.2–8.7) (p = 0.700).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival a in the total population; b by RAS mutation status; c in patients with or without liver metastasis; and d in patients with a ≥ 2-grade change from baseline ANC versus those who had a < 2-grade change at 1 month. Overall survival data were cut off on 7 November 2021. ANC absolute neutrophil count

Table 2.

Analysis of overall survival

| Trifluridine/tipiracil (N = 456) | ||

|---|---|---|

| OS months, median (95% CI) | 7.59 (7.00–8.21) | |

| RAS wild type (n = 225) | RAS mutant (n = 231) | |

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | 8.61 (7.69–9.40) | 6.77 (6.05–7.33) |

| p = 0.04 | ||

| Liver metastasis (n = 262) | No liver metastasis (n = 121) | |

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | 7.13 (6.21–7.79) | 9.40 (7.49–11.01) |

| p = 0.02 | ||

| ANC ≥ 2-grade decrease at 1 month (n = 145) | ANC < 2-grade decrease at 1 month (n = 303) | |

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | 10.38 (8.08–11.86) | 6.77 (5.98–7.59) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

| ANC decrease during treatment (n = 289) | No ANC decrease during treatment (n = 167) | |

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | 9.56 (8.80–10.74) | 4.63 (3.98–5.32) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | In combination with anti-VEGF mAb (n = 25) | Monotherapy (n = 428) |

| 12.02 (4.57–20.01) | 7.46 (6.90–8.08) | |

| p = 0.06 | ||

| With prior regorafenib exposure (n = 114) | With subsequent regorafenib exposure (n = 70) | |

| OS, months, median (95% CI) | 7.5 (6.2–8.7) | 15.2 (12.3–17.4) |

| p = 0.700 | p < 0.001 | |

ANC absolute neutrophil count, CI confidence interval, mAB monoclonal antibody, OS overall survival, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

Treatment-Associated Hematological Toxicities

In total, 63.4% (289/456) of patients reported neutropenia of any grade and 34.9% (159/456) reported neutropenia of grades ≥ 3. Most of the patients who reported neutropenia (219/289; 75.8%) experienced grade 2 or 3 severity, and most experienced a 3-grade (109/289; 37.7%) or a 2-grade (104/289; 36.0%) shift from their baseline ANC (Table 3). A total of 42 (9.2%) patients received ≥ 1 dose of G-CSF as management for neutropenia. Ten patients (2.2%) experienced febrile neutropenia.

Table 3.

Treatment-associated neutropenia

| Trifluridine/tipiracil (N = 456) | |

|---|---|

| Use of G-CSF, n (%) | 42 (9.2) |

| Neutropenia (worst reported grade), n (%) | |

| All gradesa | 289 (63.4) |

| Grade 1 | 29 (10.0)b |

| Grade 2 | 101 (34.9)b |

| Grade 3 | 118 (40.8)b |

| Grade 4 | 41 (14.2)b |

| Change from baselineb | |

| 1-grade | 36 (12.5) |

| 2-grade | 104 (36.0) |

| 3-grade | 109 (37.7) |

| 4-grade | 40 (13.8) |

| Neutropenia at 1 monthc | (N = 448) |

| All grades | 193 (43.1) |

| Grade 1 | 41 (21.2)d |

| Grade 2 | 81 (42.0)d |

| Grade 3 | 55 (28.5)d |

| Grade 4 | 16 (8.3)d |

| Change from baselined | |

| 1-grade | 47 (24.4) |

| 2-grade | 82 (42.5) |

| 3-grade | 49 (25.4) |

| 4-grade | 15 (7.8) |

ANC absolute neutrophil count, G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

aAn absence of decreased ANC readings within 14 days before the start of treatment was treated as baseline grade 0 neutropenia (i.e., no neutropenia)

bCalculated as a proportion of patients who experienced neutropenia (n = 289)

cFor analyses of neutropenia at 1 month, cases of neutropenia within 35 days post treatment initiation were evaluated; cases with a follow-up time of < 21 days were excluded

dCalculated as a proportion of patients who experienced neutropenia at 1 month (n = 193)

Of the 448 evaluable patients, 193 (43.1%) developed neutropenia at 1 month. Eight patients with < 21 days’ follow-up were excluded from the analysis. Of those patients who developed neutropenia at 1 month, the majority (136/193; 70.5%) of cases were grade 2 or 3 severity and most patients experienced a 2-grade (42.5%) or 3-grade (25.4%) shift from their baseline ANC.

A total of 147 (32.2%) patients developed thrombocytopenia, of which 18 (3.9%) patients developed grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia. Anemia occurred in 361 (79.2%) patients, of which 113 (24.8%) patients had grade ≥ 3 anemia.

Treatment Duration

The median duration of treatment was 12.4 weeks (95% CI 11.1–13.1; Table 4); 129 (28.3%) patients required ≥ 1 dose reduction. By the data cutoff date, 98.0% (447/456) of patients had discontinued treatment. Patients experiencing neutropenia during treatment had a significantly longer median treatment duration (16.1 weeks; 95% CI 14.1–17.7) compared with those without neutropenia (8.0 weeks; 95% CI 6.4–8.0) (p < 0.001). Additionally, the severity of neutropenia, indicated by a grade decrease in ANC, further delineates this association, with patients showing ≥ 2-grade decrease in ANC at 1 month experiencing longer treatment durations compared with those with < 2-grade decreases: 17.0 weeks (95% CI 13.9–18.9) versus 10.9 weeks (95% CI 10.0–12.1) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the absence of liver metastasis emerged as a positive indicator for prolonged treatment duration, 14.7 weeks (95% CI 13.0–17.7) versus 11.2 weeks (95% CI 10.3–12.4) (p < 0.001; Table 4). Contrastingly, tumor burden did not present a significant impact on the length of treatment, with low and high metastatic sites showing comparable median treatment durations: 12.6 weeks (95% CI 11.6–13.6) versus 11.2 weeks (95% CI 8.7–13.1) (p = 0.30). The combination of FTD/TPI with an anti-VEGR mAb resulted in a notably longer median treatment duration as opposed to FTD/TPI monotherapy (24.3 weeks; 95% CI 10.0–35.7 versus 12.1 weeks; 95% CI 11.0–13.0) (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Analysis of treatment duration

| Trifluridine/tipiracil (N = 456) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI)a | 12.4 (11.1–13.1) | |

| Patients requiring ≥ 1 dose reduction, n (%) | 129 (28.3) | |

| Presence of liver metastases (n = 262) | Absence of liver metastases (n = 121) | |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI) | 11.2 (10.3–12.4) | 14.7 (13.0–17.7) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

| “High” disease burden (n = 108) | “Low” disease burden (n = 275) | |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI) | 11.2 (8.7–13.1) | 12.6 (11.6–13.6) |

| p = 0.30 | ||

| ANC ≥ 2-grade decrease at 1 month (n = 145) | ANC < 2-grade decrease at 1 month (n = 303) | |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI) | 17.0 (13.9–18.9) | 10.9 (10.0–12.1) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

| ANC decreasedb during treatment (n = 289) | No ANC decreaseb during treatment (n = 167) | |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI) | 16.1 (14.1–17.7) | 8.0 (6.4–8.0) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

| In combination with anti-VEGF mAb (n = 25) | Monotherapy (n = 428) | |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (95% CI) | 24.3 (10.0, 35.7) | 12.1 (11.0, 13.0) |

| p < 0.001 | ||

p-values were calculated by log-rank test

ANC absolute neutrophil count, CI confidence interval, mAb monoclonal antibody, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

aFor the analysis on treatment duration, cases who had died or whose last drug dispensation occurred before 31 July 2021 were regarded as treatment being discontinued

bAny numerical decrease in ANC resulting in a grade shift

Discussion

This retrospective, multicenter cohort study provides real-world, population-based data on the effectiveness and safety of FTD/TPI in patients with refractory mCRC in Hong Kong. Our study confirmed the effectiveness of FTD/TPI in a real-world setting, with a median OS of 7.59 months, confirming that FTD/TPI offers an OS benefit in a difficult-to-treat, refractory mCRC population in Hong Kong.

The survival of patients with mCRC has improved substantially over the past decade, a change believed to be primarily driven by the availability of treatments after the first line [29]. One of these is FTD/TPI, which has a growing body of evidence supporting its use in patients with mCRC previously treated with, or not considered candidates for, other available therapies including fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-based chemotherapies; anti-VEGF agents; and anti-EGFR agents. Our findings further build on previous studies [13, 14, 16]—the survival outcome reported here is consistent with those reported in two pivotal phase III trials, RECOURSE (median OS, 7.1 months; 95% CI 6.5–7.8) and TERRA (median OS, 7.8 months; 95% CI 7.1–8.8) [14, 16]; a UK-based, multicenter, real-world analysis (median OS, 7.6 months) [30]; and real-world data from the non-interventional TACTIC study in Germany (median OS, 7.4 months) [31]. While the OS is similar, the median treatment duration of our study is 12.4 weeks, relatively longer than the 6.7 weeks reported in the FTD/TPI arm in the RECOURSE study. This may be attributed to a more heterogeneous population in the real-world setting with variable reassessment protocols among different centers. The median treatment duration of our study is broadly similar to other real-world studies, including PRECONNECT (median treatment duration, 11.2 weeks) [32] and a real-world study in Canada (median treatment duration, 11 weeks) [33]. Our results suggest that FTD/TPI’s benefits observed in clinical trials can be replicated in the real world in Hong Kong, despite possible existence of interethnic variances in pharmacogenetics.

As expected, neutropenia was a common adverse event in our study, with 63.4% of patients reporting neutropenia of any grade and 34.9% reporting neutropenia of grades ≥ 3. These rates were within the ranges observed in the RECOURSE and TERRA trials [14, 16]. Although chemotherapy-induced neutropenia poses a risk to patients, it is generally manageable with dose adjustments or, in severe cases, with G-CSF. In our study, patients who reported neutropenia typically experienced a 2- or 3-grade shift in their ANC levels from baseline; however, despite this and the generally high incidence of neutropenia observed overall, the use of G-CSF to manage neutropenia was low (9.2%). Conversely, the proportion of patients in the present study who required ≥ 1 dose reduction (28%) was higher than in both RECOURSE (14%) and TERRA (8.5%) but comparable to a UK real-world study (27%), suggesting that dose reduction may be the preferred method used to manage adverse events in patients receiving FTD/TPI in the real world compared with the clinical trial setting [14, 16, 30]. Despite the higher rate of dose reduction in our cohort compared with previous clinical trials, we observed similar clinical benefits in terms of treatment duration and OS achieved, suggesting that the dose reductions did not affect outcomes in general.

Prognostic factors (development of neutropenia, presence of liver metastases, and RAS mutation status) affecting treatment outcomes of FTD/TPI in mCRC have been assessed previously [14, 22–25, 34–36]. In particular, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia has been associated with favorable survival outcomes with FTD/TPI in mCRC [22–25], as well as in other cancers such as non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and gastric cancer [37–39]. Confirming this finding, we also found that the development of neutropenia at any time during treatment and a ≥ 2-grade change from baseline ANC at 1 month were associated with significant OS benefit and a longer duration of treatment (a real-world surrogate marker for PFS) in the real world among Hong Kong patients with mCRC [22–25].

The exact mechanism of the association between neutropenia and OS is unknown. There are several hypotheses, one of which suggests that a high tumor burden is associated with a high baseline ANC, thus reducing the likelihood of neutropenia developing during treatment. Moreover, because FTD is incorporated into the DNA of both CRC and white blood cells [40], the standard FTD/TPI dose may be insufficient to induce myelotoxicity in those patients with high tumor burden, necessitating higher doses in this patient group. Furthermore, the extent of neutropenia experienced by patients may reflect interpatient differences in the pharmacokinetics of FTD/TPI and its metabolites. Rapid metabolizers of FTD/TPI are speculated to be less likely to have neutropenia [24]; and in the RECOURSE trial, higher FTD exposure was associated with increased risk of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia [23]. Thus, the extent of neutropenia might be regarded as a proxy for individualized drug exposure in the tumor.

The RAS oncogene, which is typically mutated in over 50% of mCRC cases, is a known marker of resistance to several anticancer therapies, including anti-EGFR treatments [41]. Here, we found that FTD/TPI-treated patients with RAS wild-type tumors had a modest but statistically significant survival benefit compared with those with RAS-mutated tumors. However, in the RECOURSE study, FTD/TPI was found to be effective regardless of RAS status, while OS was longer for patients with RAS wild-type than RAS-mutant tumors [14]. Therefore, and given the fact that RAS-mutated disease has been associated with poorer outcomes, it is likely that the difference in OS observed in our study is attributable to the disease course rather than the effectiveness of FTD/TPI. We also found, as expected from previous real-world and clinical studies [34–36], that the absence of liver metastases was associated with longer survival and treatment duration than the presence of liver metastases. Analysis of OS for a combination of FTD/TPI with anti-VEGF mAb was limited by the small number of patients. Although the difference in OS is statistically insignificant, it is hypothesis-generating and numerically in line with a previously reported study [21]. The real-world comparison of sequencing of FTD/TPI and regorafenib is crucial as there have not been randomized controlled trials comparing the optimal sequence of FTD/TPI and regorafenib. The sequence of treatment should be tailored according to the patient’s needs, and toxicity should be taken into account. Together, our data showed that FTD/TPI is effective in prolonging survival in patients with mCRC in Hong Kong; neutropenia, RAS wild-type tumors, or no liver metastases may be associated with longer survival.

Our study has some limitations: its non-randomized retrospective nature, limited data availability from medical records, and a relatively small sample size. Additionally, heterogeneity in patients’ disease activity and demographics necessitates caution when interpreting and comparing our findings with those from previous clinical trials. Overall survival may potentially be confounded by the subsequent anticancer therapies used after progression on FTD/TPI, but our access to patients’ records on subsequent therapies was limited. Nonetheless, the CDARS that we utilized for data capture contains robust patient data and reliable follow-up data covering around 90% of patients with cancer in Hong Kong [27]. Data from the CDARS have been used in several earlier studies and thus are reliable and reflective of the real-world practice in Hong Kong [42, 43].

We anticipate that the findings outlined in this paper will lay the foundation for future research endeavors, such as investigations into the long-term quality of life for patients on FTD/TPI or comparative studies with other emerging combinations with FTD/TPI in Hong Kong and beyond.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that FTD/TPI provides a consistent clinical benefit, indicated by improved survival outcomes, in patients with mCRC refractory to standard therapies in Hong Kong, despite the higher rate of dose reduction observed in the real-world setting. Development of neutropenia, RAS wild-type status, and the absence of liver metastases are prognostic factors that appear to positively influence the response to FTD/TPI, suggesting that these patient groups may achieve optimal benefits from this therapy. Given these findings, incorporating FTD/TPI into treatment regimens for mCRC should be considered, especially for those fitting the identified prognostic profiles.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Emma Donadieu and Magdalene Chu of MIMS (Hong Kong) Ltd., which was funded by Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. and complied with Good Publication Practice 2022 ethical guidelines (DeTora LM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1298–304).

Author Contributions

Ka-On Lam and Karen Hoi-Lam Li share first authorship. Ka-On Lam, Karen Hoi-Lam Li, Roland Ching-Yu Leung, Vikki Tang and Thomas Chung-Cheung Yau contributed to the study conception and design. Vikki Tang contributed to material preparation and data collection. The analysis was performed by all authors. All authors contributed to the development of the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study and medical writing were partly supported by an education grant from Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. Publication costs, including the Rapid Service and Open Access Fees, were covered by Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. This manuscript has no associated data, or the data will not be deposited.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Karen Hoi-Lam Li has received support for meeting attendance and travel from Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. Ka-On Lam has received speaking honoraria from Amgen Inc., Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca PLC, Bayer AG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Eli Lilly and Co., GSK PLC, Merck & Co. Inc., Novartis AG, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Sanofi, and Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. Ka-On Lam has also received meeting and travel support from Merck & Co. Inc. and Taiho Pharma Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. and advisory board honoraria from Amgen Inc., Astellas Pharma Inc., and GSK PLC. Roland Ching-Yu Leung, Vikki Tang and Thomas Chung-Cheung Yau have no conflicts of interest to disclose. No payment or honoraria have been received by any author for this article.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was reviewed for ethics, science and compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH GCP guidelines, local regulations, Hospital Authority and university policies. The protocol, encompassing the use of CDARS data from all participating centers, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster before any data collection occurred (IRB reference number UW 19-460). The requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the anonymous nature of the data.

References

- 1.Onyoh EF, Hsu WF, Chang LC, Lee YC, Wu MS, Chiu HM. The rise of colorectal cancer in Asia: epidemiology, screening, and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Colorectal Cancer: Globocan. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/10_8_9-Colorectum-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

- 3.Hong Kong Cancer Registry. 10 most common cancers in Hong Kong in 2019. https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/. Accessed 6 May 2023.

- 4.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Colon and Rectum Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/application.html. Accessed 16 Mar 2022.

- 5.Osterman E, Hammarstrom K, Imam I, Osterlund E, Sjoblom T, Glimelius B. Recurrence risk after radical colorectal cancer surgery-less than before, but how high is it? Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modest DP, Pant S, Sartore-Bianchi A. Treatment sequencing in metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2019;109:70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drugs Administration. LONSURF (trifluridine and tipiracil) prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/207981s008lbl.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- 8.Japan Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Lonsurf licensing. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000207987.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- 9.European Medicines Agency. Lonsurf summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lonsurf-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- 10.Lenz HJ, Stintzing S, Loupakis F. TAS-102, a novel antitumor agent: a review of the mechanism of action. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:777–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price T, Burge M, Chantrill L, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil: a practical guide to its use in the management of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer in Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(Suppl 1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberg BA, Marshall JL, Salem ME. Trifluridine/tipiracil and regorafenib: new weapons in the war against metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14:630–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshino T, Mizunuma N, Yamazaki K, et al. TAS-102 monotherapy for pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Cutsem E, Mayer RJ, Laurent S, et al. The subgroups of the phase III RECOURSE trial of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) versus placebo with best supportive care in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2018;90:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Kim TW, Shen L, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) monotherapy in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: the TERRA study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:10–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshino T, Cervantes A, Bando H, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. ESMO Open. 2023;8:101558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson AB, Venook AP, Adam M, et al. Colon cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22:e240029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prager GW, Taieb J, Fakih M, et al. Trifluridine-tipiracil and bevacizumab in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1657–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ohtsu A, Yoshino T, Falcone A, et al. Onset of neutropenia as an indicator of treatment in the phase 3 RECOURSE trial of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) versus placebo in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl 4):775. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshino T, Cleary JM, Van Cutsem E, et al. Neutropenia and survival outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with trifluridine/tipiracil in the RECOURSE and J003 trials. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasi PM, Kotani D, Cecchini M, et al. Chemotherapy induced neutropenia at 1-month mark is a predictor of overall survival in patients receiving TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamauchi S, Yamazaki K, Masuishi T, et al. Neutropenia as a predictive factor in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with TAS-102. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donnell PH, Dolan ME. Cancer pharmacoethnicity: ethnic differences in susceptibility to the effects of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Statistical Report 2020-2021. https://www3.ha.org.hk/data/HAStatistics/DownloadReport/8?isPreview=False. Accessed 23 Apr 2024.

- 28.The R Project. The R project for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 7 February 2022.

- 29.Byrne M, Saif MW. Selecting treatment options in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stavraka C, Pouptsis A, Synowiec A, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil in metastatic colorectal cancer: a UK multicenter real-world analysis on efficacy, safety, predictive and prognostic factors. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2021;20:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kröning H, Göhler T, Decker T, et al. Effectiveness, safety and quality of life of trifluridine/tipiracil in pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: real-world data from the noninterventional TACTIC study in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2023;153:1227–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachet JB, Wyrwicz L, Price T, et al. Safety, efficacy and patient-reported outcomes with trifluridine/tipiracil in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the PRECONNECT study. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samawi HH, Brezden-Masley C, Afzal AR, Cheung WY, Dolley A. Real-world use of trifluridine/tipiracil for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:319–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabernero J, Argiles G, Sobrero AF, et al. Effect of trifluridine/tipiracil in patients treated in RECOURSE by prognostic factors at baseline: an exploratory analysis. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sousa MJ, Gomes I, Pereira TC, et al. The effect of prognostic factors at baseline on the efficacy of trifluridine/tipiracil in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a Portuguese exploratory analysis. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;31:100531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alchawaf A, Dawod M, Al-Ani M, et al. P-339 real-world data (RWD) of the use of trifluridine/tipiracil hydrochloride (TFT) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: the Greater Manchester experience. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shitara K, Matsuo K, Takahari D, et al. Neutropenia as a prognostic factor in advanced gastric cancer patients undergoing second-line chemotherapy with weekly paclitaxel. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gargiulo P, Arenare L, Gridelli C, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and treatment efficacy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of 6 randomized trials. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tewari KS, Java JJ, Gatcliffe TA, Bookman MA, Monk BJ. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as a biomarker of survival in advanced ovarian carcinoma: an exploratory study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamashita F, Komoto I, Oka H, et al. Exposure-dependent incorporation of trifluridine into DNA of tumors and white blood cells in tumor-bearing mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76:325–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martini G, Dienstmann R, Ros J, et al. Molecular subtypes and the evolution of treatment management in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920936089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AYS, Chen L, Wong ICK, Leung WK. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong JS, Dong Y, Tang V, et al. The use of cabozantinib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong-a territory-wide cohort study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. This manuscript has no associated data, or the data will not be deposited.