Abstract

The present study investigates the supplemental effects of chia seed oil (CSO) on the growth performance and modulation of intestinal microbiota in Labeo rohita fingerlings. Four diets were formulated with graded levels of CSO: 1.0%, 2.0%, and 3.0% represented as CSO (1), CSO (2), and, CSO (3) groups alongside a control group without CSO. L. rohita fingerlings (n = 180) (mean weight = 19.74 ± 0.33 g) were randomly distributed in triplicates for 60 days to these treatment groups. The results depicted significant improvements (p < 0.05) in weight gain (WG) %, specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and feed conversion efficiency (FCE) in the group supplemented with the lowest level of CSO. Gut microbial analysis evidenced the ability of CSO at 1.0% to augment the relative abundance of bacterial phyla such as Verrucomicrobiota, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidota, Fusobacteria and Firmicutes, as well as genera Luteolibacter and Cetobacterium, indicating higher alpha diversity compared to the control. Principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) demonstrated a distinct composition of microbial communities in CSO-supplemented groups relative to the control (p < 0.001). Correlation analysis further revealed a significant (p < 0.05) association of specific microbial taxa with growth performance parameters. The predictions of metabolic pathways suggested the involvement of carbohydrate and amino acid metabolic pathways in the CSO (1) group, indicating improved nutrient transport and metabolism. Overall, the findings highlight the beneficial effects of 1.0% CSO supplementation on growth performance and modulation of gut microbiota in L. rohita fingerlings.

Keywords: Chia seed oil, growth performance, intestinal microbiota, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, Labeo rohita

Subject terms: Ichthyology, Metagenomics

Introduction

The sustainability of the aquaculture sector is closely linked to the efficient formulation of aquafeeds by using feed ingredients that are renewable sources of nutrition1. Fish oil is the residual product derived from the processing of fish meal, involving steps such as steaming, pressing and separating wild fish from their remnants2. However, increasing demand and limited production of fish oil (FO) from nearly 30% of food-grade marine fish resources have rendered it as a ‘bottleneck’ in the formulation of aquafeed and ultimately, the development of the aquafeed industry3. In recent years, breakthrough discoveries have been made in emerging sources that are sustainable and nutritionally enriched4. Efforts have thus been directed toward the search for prospective vegan options, particularly plant-originated vegetable oils (VOs) that could balance the environmental repercussions of the aquafeed industry5. In this direction, numerous VOs such as soybean oil, rapeseed oil, camelina oil, palm oil and sunflower oil etc. have been examined for their inclusion levels in the diets of various farmed fish species as a potential replacement of fish oil with varying degree of success6–10.

The Chia plant, Salvia hispanica L. is an annual herbaceous oilseed plant popularly recognized as a miracle VO, rich in omega-3 (ω3) fatty acids, proteins, fibers, vitamins, minerals, and natural antioxidants11. The oil derived from the chia seeds is a rich source of polyphenols, tocopherols, phytosterols, carotenoids and other antioxidant compounds such as myricetin, quercetin, and kaempferol12. These compounds possess a tremendous ability to scavenge harmful free radicals as well as chelate ions13. Parallel to this, the supplementation of chia seed oil (CSO) is particularly encouraged, pertaining to its remarkable nutritional profile, comprising of surplus n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) content and α-linoleic acid (ALA) as well as the ability to stimulate growth and immunity in animals14,15. Besides, n-3 PUFA are important for fish immunity in addition to their nutritional importance. They are significant precursors of eicosanoids, which are important mediators of inflammatory reactions and, to some extent, immune response modulation16. An appropriate supply of n-3 fatty acids has also been discovered to be critical in maintaining alternative complement function17. Cell membranes richer with n-3 PUFA are related to reduced inflammatory response, enhanced growth rate, and either increased or no change in specific immunity18. The improvement of immune function by n-3 PUFAs is frequently dose-dependent. Moreover, CSO is also employed for its feasibility, price stability and nutritional quality19,20.

Dietary vegetable oil supplementation in fish diet particularly influences the structure and composition of inhabiting microbial communities within the gut of farmed fish21. This is because the intestinal microbiota functions as a complex ecosystem with intricate interactions with the host. These microorganisms have the potential to influence the host’s physiological development and immune function through the regulation of immune factors, intestinal barrier function and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis22. Therefore, the modulation of intestinal microbiota largely governs immunonutrition in fishes. The alteration is generally reflected in the abundance of complex and dynamic bacterial communities involved in maintaining homeostasis23. Under normal conditions, the dynamic equilibrium of the pathogenic and saprophytic bacteria within the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of fish mediates optimum growth in the host by impacting nutrient utilization and digestibility24,25. The inclusion of dietary VOs also stimulates a healthy manipulation of the ratio of pathogenic and beneficial microflora as well as induces favorable changes in intestinal mucosa24,26. The maintenance of a healthy equilibrium of beneficial and harmful bacteria brings about marked changes in nutrient digestion and absorption to finally reflect on fish growth performance by enhancing protein synthesis and development of musculature27,28.

Careful assessment of modulation of gut microbiota thus becomes essential, particularly in the processing of dietary VOs, including the CSO, in the intestinal lumen of the host fish29. Numerous classical techniques have been employed to isolate, enumerate, identify and characterize these microorganisms residing within the gut of fish30. High-throughput omics-enabled techniques, however, have replaced the traditional microbiological methods with accuracy, in recent times. Approaches such as the 16 S rRNA and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) techniques have emerged to effectively investigate bacterial communities in different species and environments31–33. These in silico approaches greatly facilitate the understanding of the influence of gut microbiota on fish physiology by analyzing their diversity and abundance, predicting functional categories of bacterial groups residing in the gut, and identifying their corresponding genes10. The profiling of the relative abundance of microbial groups occurs in terms of diversity indices that represent both alpha and beta diversity. Principal coordinate analysis are used to visualize beta diversity patterns through ordination in a distance matrix. The assessment of the functional aspect of the gut microbiota is supported by the anticipated metabolic pathways34.

Dietary incorporation of oil alters bacterial communities within the treatment groups as well as scores metabolic pathways. Although reports delineating the effects of dietary VOs on the modulation of intestinal microflora to influence growth performance are scarce, a few VOs have been reported to increase the productive performance and modulate the composition of gut microbiota in aquatic animals35–39.

Labeo rohita (Hamilton, 1822) (rohu) ranks as the 11th top species among the total 622 global aquaculture species, predominating the South and Southeast Asian countries40. A thorough understanding of the gut microbiome in L. rohita, an economically significant fish species, is essential for enhancing desirable traits such as improved growth and stronger immune responses41. Altogether, 36 phyla, 326 families and 985 genera of microbes have been reported in the gut of L. rohita using 16 S rRNA variable region-specific primers (V3 and V4)42. In addition, studies have been attempted to comparatively analyze the gut microbiomes of Indian Major carps (IMCs)41,43 as well as delineate the impact of different rearing environments on the structure, assembly and annotated functions of gut microbial communities in L. rohita44. However, the assessment of dietary VOs on the growth and gut microbiota of L. rohita has not been previously addressed, to the best of our knowledge.

The present study is thus aimed to gain deeper insights into the alteration of intestinal bacterial communities and their role in modulating growth on supplementation with CSO in the diet of L. rohita fingerlings. To investigate the mechanisms underlying growth enhancement resulting from the supplementation of CSO in L. rohita diet, 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing was undertaken in the present study.

Results

Growth performance

The growth variables representing the productive performance of the L. rohita fingerlings were significantly changed on supplementation of chia seed oil as exhibited in Table 1. Among the CSO-supplemented groups, the highest (p < 0.05) final weight was recorded in the treatment group fed with 1.0% CSO. The weight gain % and SGR were also recorded to be maximum (p < 0.05) in the treatment group fed with 1.0% CSO supplementation, compared to the other treatment groups (Table 1). The group CSO (1) also exhibited a remarkable increase (p < 0.05) in the FCE values relative to other treatment groups. The lower FCR was observed in the group fed with the lowest supplementation of CSO, which was comparable to the group fed with 2% CSO. No mortality was observed in the 1.0% CSO-supplemented group, as compared to the other treatment groups. However, relatively higher mortality was recorded in the highest supplemented group of 3.0% CSO. Other productive performance indices, such as HSI and ISI were found to be similar among all the treatment groups.

Table 1.

Growth performance of Labeo rohita fingerlings fed diets containing graded level of chia seed oil (CSO) for 60 days.

| Variables | Treatment groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CSO (1) | CSO (2) | CSO (3) | |

| Initial wt. | 19.77 ± 0.23 | 19.42 ± 0.25 | 19.40 ± 0.37 | 19.82 ± 0.31 |

| Final wt. | 42.16 ± 0.58c | 47.15 ± 0.54a | 44.24 ± 0.46b | 41.82 ± 0.24c |

| Wt. gain percentage | 113.29 ± 1.89c | 142.91 ± 4.79a | 128.24 ± 2.46b | 111.15 ± 3.47c |

| SGR | 1.24 ± 0.01c | 1.40 ± 0.03a | 1.29 ± 0.01b | 1.22 ± 0.02c |

| FCR | 1.82 ± 0.02a | 1.53 ± 0.04b | 1.65 ± 0.01b | 1.86 ± 0.03a |

| FCE | 0.54 ± 0.01c | 0.65 ± 0.01a | 0.60 ± 0.02b | 0.53 ± 0.01c |

| Survival % | 95.55 ± 2.22 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 95.55 ± 2.22 | 93.33 ± 3.85 |

| HSI | 1.66 ± 0.01 | 1.75 ± 0.04 | 1.68 ± 0.02 | 1.67 ± 0.02 |

| ISI | 1.80 ± 0.02 | 1.84 ± 0.03 | 1.86 ± 0.04 | 1.81 ± 0.07 |

Values in the same row with different superscripts (a, and b) differ significantly (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3).

Gut microbiome analysis

Abundance of gut bacteria

Profiling of gut bacterial communities from 12 fecal samples of L. rohita fingerlings, supplemented with different doses of CSO (representing 4 treatments, each replicated three times), yielded a total of 2,922,680 raw reads, ranging from 189,052 to 299,468 reads. After quality filtering of sequences, 2,328,785 reads were processed and used for identification purposes. Non-chimeric filtered amplicon sequences contained a total of 1526 OTUs.

Analysis of OTUs of bacterial communities displayed a total of 52 phyla among differentially formulated CSO feeds. Variations in the number and composition of bacterial communities among the treatment groups signify the impact of different dosages of CSO in altering the gut microbiome of L. rohita (Fig. 1A). Among the total top 10 bacterial phyla, six namely Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobiota, Actinobacteriota, Bacteriodota, Fusobacteriota and Firmicutes were represented by ~ 65% of the community in all samples (Fig. 1A). The bacterial phyla in all the treatment groups were mainly Proteobacteria (ranging from 32.54% in control to 22.21% in CSO (1), Verrucomicrobiota (ranging from 27.95% in CSO (1) to 18.77% in CSO (2), Actinobacteria (ranging from 9.74% in control to 4.66% in CSO (2), Bacteriodota (ranging from 9.4% in CSO (1) to 5.06% in control, Fusobacteriota (ranging from 8.97% in CSO (1) to 2.89% in CSO (3) and Firmicutes (ranging from 6.89% in CSO (1) to 3.12% in CSO (2). The comparative abundance of Proteobacteria was higher in CSO (2) among the groups, comparable to the control. Similarly, Verrucomicrobiota, Bacteroidota, and Fusobacteria (~ 9%) were comparatively increased in the CSO (1) group. The comparative richness of Actinobacteriota was markedly enhanced (p ≤ 0.05) in the lowest supplemented CSO (1) group, however, its abundance in the group was statistically similar to the control. It was also noted that the abundance of Firmicutes was found to be less than 5% among the bacterial phyla in all the treatment groups except CSO (1) wherein its comparative richness was statistically higher (~ 7%). Differential analysis of the relative abundance of Proteobacteria, Bacteriodota, Firmicutes and Fusobacteria (Fig. 1A) showed a significant difference between the CSO-supplemented groups and the control. Next, at the genus level, Luteolibacter (Verrucomicrobia) and Cetobacterium (Fusobacteria) were significantly abundant taxonomic groups among the total top (n = 15) genera, and the various treatment groups (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Relative abundance of top ‘n’ gut microbial communities in CSO supplemented L. rohita. phylum level (n = 10) b) genus level (n = 15), respectively. Taxa below 1% relative abundance were clubbed together as “others.” Taxa with asterisk (*) mark were statistically different among the treatment groups (Kruskal–Wallis test). (*: p ≤ 0.05; **: p ≤ 0.01; ***: p ≤ 0.001).

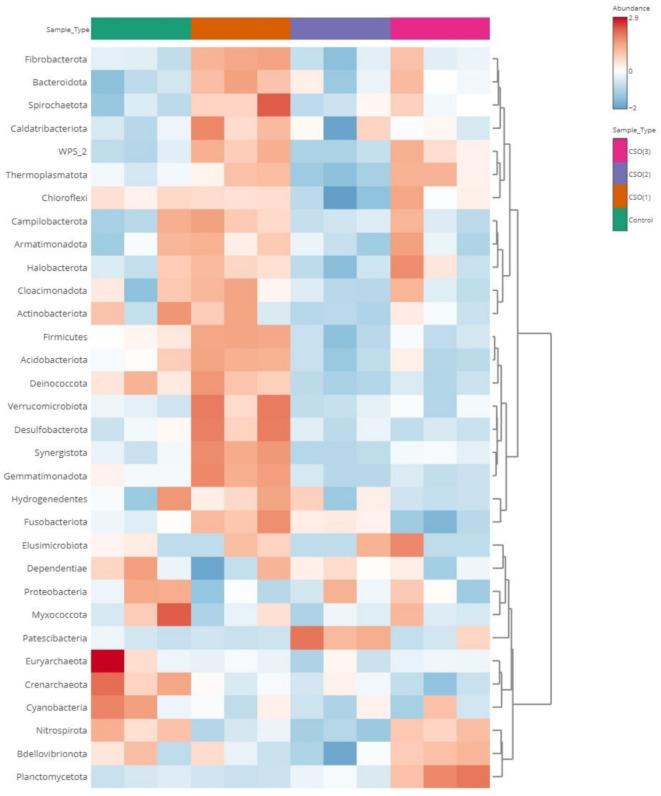

The clustering patterns and comparative richness of bacterial phyla among different experimental groups were further represented by the clustering heatmap of OTUs from diverse CSO treatments (Fig. 2). It can be noted that the major phyla, namely Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota, Fusobacteriota and a few others showed greater abundance in the CSO (1) group than the other groups as represented by the corresponding values denoting the average of 16 S rRNA gene OTUs within the annotation bar of the respective heatmap (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Heatmap showing average of 16 S rRNA gene OTUs between different experimental groups of L. rohita supplemented with CSO. The colour of the heatmap indicates the relative abundance ranging from dark red (higher) to dark blue (lower abundances), as represented by the values in the annotation bar.

Diversity of bacterial community

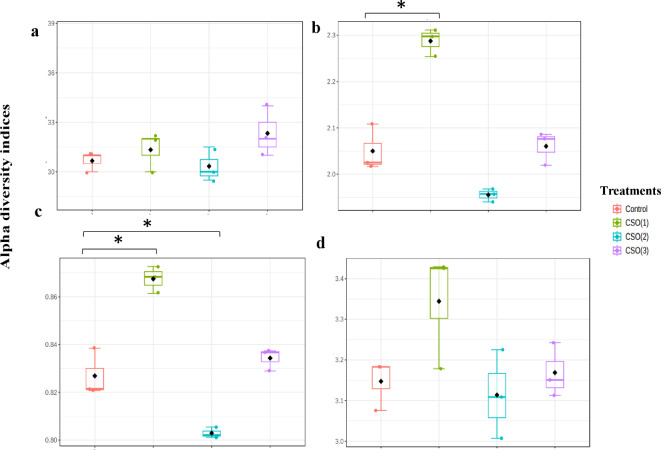

The analysis of alpha diversity within the gut microbial communities of L. rohita fingerlings was based on the measured values of 4 different indices, namely the Chao1 index, Shannon index, Simpson index and Fisher index. At the phylum level, all the indices’ values were higher in the CSO (1) group in comparison to the control, except the Chao1 index. The Shannon and Simpson indices indicated a significantly higher diversity of the gut microbial groups in the lowest supplemented 1% CSO group. No significant differences could be stated for Chao1 richness and the Fisher index, among the groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3). Clustering of groups at the phylum level, as estimated by the PCoA cluster analysis, revealed the formation of distinct clusters in the PCoA space and a clear separation of CSO (1) and CSO (2) groups relative to the control. However, the CSO (3) group was found to be clustered together with the control at the taxonomic phylum level (Fig. 4). This suggests that the enrichment/abundance and diversity of the gut microbial communities were affected by varying inclusion of CSO relative to the control. Further, the analysis denoted significant variations in the beta diversity of gut microbial composition among different treatment groups with a p value ≤ 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Alpha diversity of gut microbiome from experimental treatment groups of chia seed oil (CSO) supplemented L. rohita fingerlings represented by (a) Chao1 index (b) Shannon index (c) Simpson index and (d) Fisher index at the phylum level. Groups with asterisk (*) mark are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Principle Coordinate analysis (PCoA) of intestinal microbiota of different CSO treatment groups at phylum level.

Interactions of bacterial communities with treatments

The relationship between the OTUs of different treatment groups as represented by the Venn diagram revealed a total of 350 OTUs shared among all of them at 97% similarity cut-off. The respective number of unique OTUs for the control, CSO (1), CSO (2) and CSO (3) groups were 54, 72, 19, and 32, respectively (Fig. 5). PCA was generated using different growth parameters and the top 15 bacterial phyla. Eigenvalues > 0.9 which represented 100% of the total variance, were extracted into three principal components. Total addressed variance (100%) was decomposed in PC1 for 60.8% and PC2 for 27.2%, and 11.97% for PC3, respectively (Fig. 6; Table 2). WG, SGR, FCR, FCE, Survival, HSI, Bacteroidota, Euryarchaeota, Firmicutes, and Fusobacteriota were observed with higher loading in PC1 (Table 2). Based on component loading, the attributes WG, SGR, FCR, FCE, Survival, HSI, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Cyanobacteria, Euryarchaeota, Fusobacteriota, Patescibacteria and Proteobacteria were revealed as the most important parameters among 17 variables as affected by CSO supplementation in L. rohita fingerlings (Table 2). Pearson’s correlation analysis was then performed among ten bacterial phyla, CSO-supplemented groups and the growth indices to prevent redundancy in PCA (Table 3). Verrucomicrobiota was significantly (p < 0.05) correlated, positively with WG% (r = 0.95), SGR (r = 0.96), survival (r = 0.96) and HSI (r = 0.98), and negatively to FCR (r = -0.96, p < 0.05). Similarly, Fusobacteriota was seen to be significantly associated with FCE (r = 0.96) and FCR (r = -0.95) in a positive and negative correlation respectively.

Fig. 5.

Venn Diagram representing the unique and shared OTUs among the experimental groups.

Fig. 6.

Principle Component analysis (PCA) of growth indices (indicated in green) with major bacterial phyla (indicated in blue) within different CSO supplemented treatment groups (highlighted in yellow).

Table 2.

Principal components (PC) and factor loadings extracted from major bacterial phyla and different growth indices; bold loading extracts were used to explain PC.

| Principal components | PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 10.4294 | 4.6089 | 1.9617 |

| Variability (%) | 61.3495 | 27.1114 | 11.5391 |

| Cumulative % | 61.3495 | 88.4609 | 100.0000 |

| Factor loading / Eigen vector | |||

| WG | 0.9998 | -0.0029 | -0.0207 |

| SGR | 0.9976 | 0.0017 | -0.0009 |

| FCR | -0.9939 | -0.0901 | 0.0642 |

| FCE | 0.9934 | 0.0487 | -0.1043 |

| Survival | 0.9613 | 0.2587 | -0.0953 |

| HSI | 0.9629 | 0.0333 | 0.2678 |

| ISI | 0.5982 | -0.7484 | -0.2864 |

| Actinobacteriota | -0.3230 | 0.8724 | -0.3668 |

| Bacteroidota | 0.8466 | 0.5219 | 0.1043 |

| Cyanobacteria | -0.0965 | -0.8467 | -0.5233 |

| Euryarchaeota | -0.7736 | 0.6285 | 0.0803 |

| Firmicutes | 0.6480 | -0.4903 | 0.5828 |

| Fusobacteriota | 0.9371 | 0.0082 | -0.3490 |

| Patescibacteria | -0.1106 | 0.9276 | -0.3569 |

| Planctomycetota | -0.6378 | -0.2712 | 0.7209 |

| Proteobacteria | -0.4152 | -0.7821 | -0.4648 |

| Verrucomicrobiota | 0.9633 | 0.1971 | 0.1823 |

Table 3.

Relationship between growth indices and major bacterial phyla in different CSO treatments based on Pearson correlation matrix.

| Bacterial phyla | WG% | SGR | FCR | FCE | Survival % | HSI | ISI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteriota | -0.3178 | -0.3212 | 0.2189 | -0.2401 | -0.0499 | -0.3802 | -0.7411 |

| Bacteroidota | 0.8428 | 0.8474 | -0.8817 | 0.8555 | 0.9389 | 0.8605 | 0.0860 |

| Cyanobacteria | -0.0832 | -0.0975 | 0.1386 | -0.0825 | -0.2619 | -0.2612 | 0.7258 |

| Euryarchaeota | -0.7769 | -0.7727 | 0.7174 | -0.7463 | -0.5887 | -0.7025 | -0.9562 |

| Firmicutes | 0.6372 | 0.6467 | -0.5624 | 0.5591 | 0.4406 | 0.7637 | 0.5877 |

| Fusobacteriota | 0.9441 | 0.9374 | -0.9545 | 0.9677 | 0.9361 | 0.8091 | 0.6544 |

| Patescibacteria | -0.1058 | -0.1087 | 0.0034 | -0.0275 | 0.1676 | -0.1712 | -0.6582 |

| Planctomycetota | -0.6518 | -0.6389 | 0.7046 | -0.7220 | -0.7519 | -0.4301 | -0.3850 |

| Proteobacteria | -0.4032 | -0.4161 | 0.4532 | -0.4020 | -0.5571 | -0.5502 | 0.4701 |

| Verrucomicrobiota | 0.9587 | 0.9635 | -0.9634 | 0.9475 | 0.9596 | 0.9829 | 0.3765 |

The correlation network portrayed the interaction of different bacterial phyla within the CSO-supplemented groups. The network demonstrated a positive or negative relationship among the major bacterial phyla based on dietary supplementation level (Fig. 7). The presence of Firmicutes was observed to positively correlate with Fusobacteriota, Halobacterota, Desulfobacterota and Thermoplasmatota. Simultaneously, it was seen to negatively correlate with Myxococota and Nitrospirota.

Fig. 7.

Correlation network among the major bacterial phyla (> 1% relative abundance) of CSO supplemented treatment groups.

The predictions of metabolic pathways among different treatment groups are depicted in Fig. 8. The results suggested that the predictive pathways would have been involved in the transport and metabolism of nutrients such as the carbohydrate and amino acid metabolic pathways, within the CSO (1) group. Similarly, the beta-alanine pathway might have been involved in the increased biological functions in the CSO (2) group, while pathways for antibiotic resistance, bisphenol degradation and metabolism of phenolic compounds might have played a role in mediating the responses were found in the highest supplemented CSO (3) group.

Fig. 8.

Differentially expressed metabolic pathways predicted across CSO supplemented treatment groups. https://www.genome.jp/kegg/ko.html.

Discussion

A recent trend within the aquaculture industry has highlighted the predominance of vegetable oils as major feed fish ingredients in the diet formulation of a number of commercial fishes27. The enrichment of diets with plant-based vegetable oils as sustainable constituents of fish feed has gained profound significance owing to their distinctive biological properties. The present study can thus be regarded as an extended study on this current usage of VOs, featuring the implementation of CSO as a promising VO supplement and a prospective vegan source in aqua-diets. The study is thus focused on the impact of CSO supplementation on the growth, microbial composition and bacterial diversity residing in the gut of L. rohita fingerlings.

Significantly higher growth performance in terms of improved WG %, SGR, FCR and survival percentage of fish fed with the lowest supplemented dose of 1% CSO has been observed in this study. The findings are supported by a parallel study dealing with the supplementation of emodin at an equivalent feeding rate of 10 g kg− 1 feed in Cyprinus carpio45. Consistent with our findings, substituting fish oil with vegetable oil sources demonstrated increased growth in O. niloticus46, O. mossambicus47 and Mylopharyngodon piceus48. Similar effects of improved growth indices have also been achieved with the replacement of fish oil with canola oil or a mixture of canola oil, linseed oil and sunflower oil in rainbow trout fingerlings49. Significantly higher weight gain has been reported with the supplementation of palm oil in O. niloticus50. Next, the phenomenon of lower FCR implies the increase in feed palatability, feed utilization and feed intake by means of exerting a favorable effect of multiple bio-active phenolic constituents of CSO on digestive processes, nutrient absorption and subsequently growth of the fish51. On the other hand, no significant effect on the productive performance parameters including final weight, WG%, SGR, FCR and survival has been reported in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) on the replacement of cod liver oil with sunflower oil52. In addition, another study reported an unaffected HSI and ISI in Labeo rohita, which might be associated with an insignificant impact of the sunflower oil on lipid assimilation efficacy or the size of the liver and intestine relative to whole body weight of the fish53. Apart from its usage as a dietary supplement, CSO has also shown promising results with respect to major growth indices such as WG %, SGR and FCR of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L.)54. Further, the supplementation of 1% CSO altered gut microbial composition and led to a significant increase in growth performance in rohu fingerlings than those fed with 2% and 3% chia seed oil. Similar studies revealed that higher levels of n-3 fatty acid led to immunosuppression of Catla catla fingerlings55. It has been reported that the feed utilization of fish tends to decline when dietary n-3 HUFA levels become excessive. High protein digestibility and lipid utilization might be key factors for better growth performance of rohu in the 1% CSO group. In agreement with our results, the negative effects on the growth performance of fish at higher CSO levels might be correlated to the disturbance in membrane polar lipids56,57.

Microbiome profiling provides a holistic overview of dietary alterations and their induced impact on fish health and immunity5. The alterations in gut microbial composition, structure or functionality and their consequential influence on the health of host fishes post-dietary manipulation, represent a pivotal research domain within the field of aquaculture science58. The incorporation of CSO similar to any other supplemented nutrient or feed additive tends to influence the composition of gut microbial communities that govern the processing of these dietary lipids by means of their metabolic processes in the host59. The effect was particularly evident in the occurrence of dominant bacterial phyla within the gut of the supplemented groups. These dominant bacterial taxa observed in the gut of rohu fingerlings might be involved in maintaining the intestinal homeostasis which play an important role in the development and maturation of the host immune system60. These are also the predominant components of gut microbiota in fishes which are associated with the repair of the intestinal epithelium thereby, resulting in improved immune responses61. In our study, the highest relative abundance of dominant bacterial phyla namely Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteriota, Fusobacteria, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes were identified in the lowest supplemented CSO (1) group. Actinobacteria play a crucial role in the decomposition of organic matter in the fish gut62. Besides, the abundance of Firmicutes is extremely relevant in the detection of inflammatory markers such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and immunoglobulin M (IgM), which are known to reduce enteritis and gut microbial perturbations and ultimately leading to sub-acute intestinal damage63. Fusobacteriota, with its ability to generate butyrate, offers a plethora of advantages to its host fish gut health64. The increase in the abundance of Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes in the lowest CSO fed group, can also be corroborated with the similar findings in in black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii)65. Presence of similar taxonomic groups, as found in our study, has been reported on the incorporation of rape seed oil rainbow trout66. These differential taxonomic biomarkers namely, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes that varied in response to the additive dose of CSO and increased substantially in the CSO(1) group, correlate to the highest weight gain in the group. This further relates to the role of these microbes in metabolizing nutrients contributing significantly to the host’s energy supply67. It can be additionally noted that the Firmicutes: Proteobacteria ratio increased in the CSO (1) group in comparison to the control. i.e., specifically, the presence of Proteobacteria displayed a negative correlation with Firmicutes, with variations in their composition observed among different treatment groups (Fig. 1A). A similar increase has been reported in rainbow trout on addition of a plant-based diet68. The decreased prevalence of Proteobacteria is also a marker for relatively lesser unstable microbial community (dysbiosis) in the lowest CSO-supplemented CSO(1) group67. Further, the respective decrease and increase in Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria groups observed in our study also aligns with the similar trend obtained with the incorporation of emodin in the diets of common carp45.

At the genus level, Luteolibacter was found to be maximally represented as the dominant community in CSO (1) group. Luteolibacter, a member of Verrucomicrobiota is known for mucus degradation within the intestine. It is chiefly involved in repairing the damage to intestinal barrier integrity69. Besides, it has been noted to play a supportive role in facilitating the colonization of Lactobacillus, an important probiotic in the fish gut70. It likely contributes to physiological activities such as nutrient absorption as well as glucose and respiratory metabolism71. Together with Luteolibacter, the prevalence of Cetobacterium in the gut of L. rohita, observed in our investigation, corresponds to its chief abundance in several freshwater fish species72. This symbiotic bacterium facilitates the fermentation of dietary fibres present in the feed to generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that lower the intestinal pH73. The acidic environment supports the growth of intestinal villi and enhances the activity of various digestive enzymes such as lipase, protease and amylase produced by the bacterium74,75. Further, this genus is metabolically important in synthesizing vitamin B12 and volatile fatty acids along with other metabolites with antimicrobial properties, thereby contributing in the interaction between gut microbiota and intestinal barrier-tight junctions76. Moreover, it has also been reported in the correlation analysis that the abundance of the probiotic Cetobacterium was related to the down regulation of NF-κB gene responsible for the activation of inflammatory cytokines75. Based on these reports, Cetobacterium could thus be suggested towards promoting growth in L. rohita by stimulating intestinal health and possibly inhibiting the NF-κB pathway. Thus, the favourable modulation of gut microbiota explains the improvement of growth performance in L. rohita on supplementation with CSO at 1.0%. Next, the heatmap clustering of OTUs among different groups revealed that, each treatment group was associated differently with diverse gut microbial communities.

To assess the diversity of gut microbial communities for community profiling, alpha and beta diversity indices were measured. The alpha diversity serves as a measure of within-sample diversity and provides a summary of diversity between individual samples. On the other hand, beta diversity quantifies between-sample diversity between ecological communities and captures dissimilarity scores between pairs of samples through clustering or dimensionality reduction techniques. Various statistical tests were employed to assess the significance of observed differences within the indices. The PCoA analysis is used to visualize beta diversity patterns through ordination in a distance matrix. It maximizes the linear correlation between samples and signifies more similarity in the microbial community profiles of samples that lie close to each other. Our findings of significant changes in the Shannon and Simpson indices were also consistent with the results in a similar study dealing with the incorporation of emodin at an equivalent supplementation level of 10 g kg− 145. A higher Shannon index was also exhibited in gilthead sea bream on incorporation of camelina oil10. Contrary to this, the above indices were not significantly affected in rainbow trout on supplementation of rapeseed oil66 and camelina oil77 which may be due to the complete replacement of fish oil by rapeseed oil or due to incorporation of camelina oil in the fish diets. Further, the results of PCoA analysis confirmed marked impacts of CSO supplementation on microbial community composition in CSO-fed treatment groups, particularly the CSO (1) group. PCoA revealed that control and CSO (3) group were relatively coherent i.e., with least difference between the taxonomic richness of their microbial communities78. On the other hand, the other two groups were observed to be clustered separately. This indicated the profound effect of CSO supplementation at both 1% and 2% levels on the composition of gut microbial communities in the two groups, in comparison to the control. Next, it appears from the results of PCA analysis that CSO supplementation at 1.0% had a positive impact on the growth indices as well as the composition and structures of the bacterial communities. In fact, the differential effect among the various supplemented groups was reflected in either the replacement of one species/taxon by another, i.e., turnover or the assemblage of species with each other, depicted as nestedness79 (Fig. 6).

The predictions of metabolic pathways exhibited remarkable functional involvement of amino acid metabolic pathways in the CSO (1) group, compared to the group fed with a control diet in the present study (Fig. 8). This prediction may be correlated to the favourable influence of CSO supplementation on the abundance of genes associated with the regulation of protein and energy homeostasis by amino acids, that play a crucial role in the growth of corresponding bacterial communities in the gut80. KEGG analysis is the primary method used for the evaluation of the predictive functions of the gut microbiome and the determination of metabolic capabilities of non-human microbiomes. Following the analysis, the differential intestinal microbiota identified in the study may potentially serve as biomarkers associated with amino acid synthesis. For instance- an increase in the abundance of Actinobacteria may be correlated to the possible enrichment of amino-acid metabolic pathway81. CSO-induced changes in the intestinal microbiota composition may be linked to the synthesis and utilization and accumulation of amino acids82. Moreover, the involvement of the predictive carbohydrate metabolic pathway along with amino acid metabolism, was also observed in our study which suggests an aided nutrient digestion, absorption and utilization by the gut microbiota in the CSO (1) group83. Together, the functional role of these pathways might have mediated the potential enhancement and improvement of the overall growth performance of L. rohita fingerlings of the CSO (1) group. Thus, it can be inferred that CSO intervention adjusted the intestinal microbiota function according to the changes in its structure.

To summarize the overall findings, the results of this study suggested that the fish fed with 1% CSO had favorably altered the microbial composition and diversity which potentially led to augmented growth performance in L. rohita fingerlings. In addition, improvement in the highest taxonomical richness of major bacterial phyla in the group supplemented with 1.0% CSO, was also observed. Thus, it can be speculated that the usage of CSO at 1.0% can improve intestinal immunity by reshaping the composition of intestinal microbiota in a way that promotes the growth of beneficial communities such as Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes. More elaborate metagenomic studies are, however, warranted to overcome the limitation of the 16 S rRNA technique in identifying the actual abundance and composition of the gut microbiota at the species level as well as to reveal the exact mechanism of modulation of intestinal microbiota in favoring immunity. The sequences generated by the next-gen sequencing platform in the present study cannot be assigned to specific bacterial species levels, which should be addressed in future studies using high-resolution profiling of gut bacteria using more sophisticated bioinformatics and sequencing platforms such as PacBio SMRT sequencing systems.

Methods

Experimental setup

L. rohita fingerlings were procured from a commercial fish farm at the State Fisheries Department, Doranda, Ranchi and then transported to the wet laboratory of the School of Molecular Diagnostics, Prophylactics and Nanobiotechnology (SMDPN), ICAR-Indian Institute of Agricultural Biotechnology (IIAB), Garhkhatanga, Ranchi, India for experimental setup and further feeding trial. Post acclimatization to experimental conditions, a total of 180 fingerlings, with an initial average weight of 19.74 ± 0.33 g, were distributed in 12 randomly assigned and properly aerated independent rectangular FRP tanks of 300 L capacity at a stocking density of 15 fish in each tank. The experimental tanks in the rearing facility were designed as three tanks per treatment diet to allow triplicate measurements. All the water quality parameters, namely water temperature (25.8–28.8ºC), pH (7.36–7.72), and dissolved oxygen (6.36–6.82 mg L− 1) were maintained in the optimum range to suit the rearing environment.

Formulation of experimental diets

Four diets were formulated with different concentrations (0.0%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 3.0%) of pure and natural, golden bright colored and cold pressed CSO, procured from the local market (Salvia cosmeceuticals, Pvt. Ltd; New Delhi, India) (Table 4). The incorporation of CSO was made by replacing cod liver oil at graded levels to fit the gross lipid percentage to 6.00 g 100 g− 1 in accordance with the nutritional requirements of L. rohita84. The constituent ingredients in individual diets were measured and mixed proportionately with a sufficient amount of distilled water to result in a moderately stiff dough. The dough was steam pressed in an autoclave (Equitron® Autoclave SLEFA) at 15 psi for 20 min, cooled at room temperature and finally recovered as 1 mm pellets through an automated pelletizer (Motiwala Enterprises, Mumbai). The obtained pellets were dried in a hot air oven at 60ºC for 36 h and then cooled at room temperature before being carefully bagged and stored in labeled airtight containers at -20 °C. The fish were hand-fed twice a day at 10:00 am and 5:00 pm up to apparent satiation. The residual feed and the fecal matter were removed by siphoning after the last feeding of the day and by alternate exchange of 20% of the culture water. On every fortnight, adjustments were made to the feeding rates as per the change in the total biomass.

Table 4.

Composition of the experimental diets (g kg− 1 on dry matter basis) fed to L. rohita fingerlings during the experimental period of 60 days.

| Ingredients | Control | CSO (1) | CSO (2) | CSO (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean meala | 310 | 310 | 310 | 310 |

| Fish meala | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Groundnut meala | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| Wheat floura | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| Corn floura | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| Cod liver oila | 60 | 50 | 40 | 30 |

| Chia seed oila | 00 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| Vitamin + mineral mixb* | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| BHTd | 05 | 05 | 05 | 05 |

| Vitamin Cc | 05 | 05 | 05 | 05 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Proximate analysis (g kg− 1) | ||||

| Crude protein | 352.3 | 351.4 | 350.8 | 349.8 |

| Crude lipid | 71.3 | 71.4 | 71.6 | 71.5 |

| Ash | 96.1 | 95.7 | 95.5 | 95.8 |

All the quantities given in the table were measured in grams.

a Procured from a local market,

b Prepared manually and all components from Himedia Ltd,

c SD Fine Chemicals Ltd., India.

dHimedia laboratories, Mumbai, India.

b*Composition of vitamin mineral mix (quantity/250 g starch powder): vitamin A 55,00,00 IU; vitamin D3 11,00,00 IU; vitamin B1 20 mg; vitamin B2 2,00 mg; vitamin E 75 mg; vitamin K 1,00 mg; vitamin B12 0.6 µg; calcium pantothenate 2,50 mg; nicotinamide 1000 mg; pyridoxine 1,00 mg; Mn 2700 mg; I 1,00 mg; Fe 7,50 mg; Cu 2,00 mg; Co 45 mg; Ca 50 g; P 30 g.

CSO- Cold pressed chia seed oil was procured from Alvia comeceuticals, Pvt. Ltd; New Delhi, India.

Fatty acid analysis of experimental diets

Saponification and lipid esterification were used to prepare fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) from feed samples according to the standard IUPAC procedure. Thermo Scientific ITQ 900 Gas Chromatography-Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry (GC/IT-MS) was used to determine the fatty acid contents of the feed samples. To put it briefly, 1 L (30: 1 split ratio) was injected into GC-MS to examine the FAME. A GC (Trace GC Ultra, Thermo Scientific) with a capillary column (TR-FAME, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 m film thickness) and an MS (ITQ 900, Thermo Scientific) connected to it were used to identify and quantify the fatty acids. The oven temperature protocol was established in accordance with the outlined approach85 for the separation of fatty acids. With a column flow rate of 1.0 mL per minute, helium was employed as the carrier gas. The temperatures of the ion source and transfer line were 220 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The MS condition employed were as follows : ionization voltage 70 eV, range 40–500 m/z, and the scan time was the same as the GC run time. By using the NIST Library (version 2.0, 2008) and comparing the retention times and peak areas to those of standards (ME-14-KT and ME-19-KT, SUPELCO Analytical), the individual constituents displayed by GC were recognized and calculated and presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Fatty acid profile (% total fatty acids) of experimental diets.

| Fatty acids (%) | Control | CSO (1) | CSO (2) | CSO (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12:0 | 1.15 | 1.45 | 1.8 | 2.08 |

| C13:0 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| C14:0 | 5.86 | 4.34 | 3.64 | 2.72 |

| C15:0 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.48 |

| C16:0 | 16.63 | 16.26 | 15.04 | 14.81 |

| C17:0 | 3.22 | 3.16 | 2.59 | 2.11 |

| C18:0 | 3.42 | 3.51 | 3.65 | 3.83 |

| C20:0 | 0.8 | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.31 |

| C21:0 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| C23:0 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

| C16:1 | 5.73 | 5.03 | 4.33 | 2.71 |

| C18:1 | 11.72 | 12.80 | 15.73 | 17.38 |

| C20:1 n-9 | 2.94 | 3.01 | 3.37 | 3.73 |

| C22:1 n-9 | 3.03 | 3.45 | 4.23 | 4.59 |

| C18:2 n-6 (LA) | 5.86 | 7.93 | 10.49 | 12.65 |

| C18:3 n-3 (ALA) | 2.47 | 6.49 | 13.46 | 19.87 |

| C20:3 n-3 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| C20:5 n-3 (EPA) | 7.61 | 6.09 | 4.33 | 2.69 |

| C22:6 n-3 (DHA) | 10.84 | 8.56 | 6.43 | 3.19 |

| ∑ SFA | 32.85 | 30.76 | 28.31 | 26.82 |

| ∑ MUFA | 23.42 | 24.29 | 27.66 | 28.41 |

| ∑ n-3 PUFA | 22.01 | 22.08 | 24.93 | 26.26 |

| ∑ n-6 PUFA | 5.86 | 7.93 | 10.49 | 12.65 |

| ∑ PUFA | 27.86 | 30.01 | 35.42 | 38.91 |

| EPA + DHA | 18.45 | 14.65 | 10.76 | 5.88 |

CSO-Chia Seed Oil.

SFA- Saturated fatty acid; MUFA- Monounsaturated fatty acid;

PUFA- Polyunsaturated fatty acids; LA-Linoleic acid; ALA-Alpha linolenic acid; EPA- Eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA-Docosahexaenoic acid; EPA + DHA- (C20:5 n-3 + C22:6 n-3).

Growth performance

At the termination of the feeding trial, 15 fish per treatment (5 fish per replicate) were anesthetized using (Merck, Germany) (50 µl L− 1 water). Morphometric measurements of the weight (g) of the individual fish were noted fortnightly. Fish were weighed using an electronic balance (Aczet CG 30), prior to and after the feeding trial. Both their initial and final weights were individually recorded. The total weight of the liver and the intestine were additionally noted for each fish. Growth performance was then evaluated in terms of weight gain (WG) percentage, specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), feed efficiency ratio (FCE), survival percentage, hepatosomatic index (HSI) and intestinal-somatic index (ISI), based on the following standard formulae:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sampling and assessment of gut microbiome

Genomic DNA extraction

Fecal samples were collected after pooling the content from the aseptically removed distal gut of two euthanized fish from each tank (n = 6). Clove oil (Merck, Germany) at the rate of 200 µl L− 1 was used to euthanize fish. Total 12 fecal samples (3 samples/group) were prepared and immediately transferred to a 1.5mL Eppendorf tube for storage in refrigerated condition at -20 °C for DNA extraction and 16 S rRNA sequencing. The DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). The extracted DNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water at 80 ng µL− 1. The primary quality of the isolated DNA was checked by measuring the concentration in a Nanodrop ND-100 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific – IN). Further quality of DNA was assessed with agarose gel electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel and observed on Syngene Gel Documentation System G: BOX F3.

Library preparation and amplicon sequencing

Genomic DNA libraries were constructed using the protocol provided by Illumina for 16S rRNA library preparation (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). About 25 ng of DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification using KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix (Roche, Basel, CHE). Gene-specific V3-V4F (forward primer) (5’CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG3’ (reverse primer) (5’GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC3’) were hybridized to the specific ends flanking the hypervariable V3-V4 region of 16 S rRNA gene amplicon. The conditions were optimized to an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30s, 55 °C for 45s and 72 °C for 30s and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplicons were purified using AMPure XP beads (Backman Coulter, USA) to clean DNA and remove unused primers. The false positive PCR result was eliminated by using nuclease free water. Indexing was performed with an additional 8 cycles of PCR using the Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The sequence data was generated using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The libraries were sequenced in a 300-bp paired-end run for the V3-V4 region in over 600 cycles, using theMiSeq v3 Reagent Kit. The SRA (sequence read archive) of present study was deposited in the NCBI SRA database under bioproject accession ID PRJ NA979959 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ PRJNA 979959).

Sequenced data analysis

The analysis of the 16 S rRNA amplicon data was conducted using the Mothur v.1.30.0 pipeline as described86. Initial assessment of raw sequence reads involved evaluating base call quality distribution, % GC, and sequencing adapter contamination using Fast QC v0.11.8 and MultiQC tools87. TrimGalore v0.4.088 was then employed to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the reads. The processed reads were subsequently imported into Mothur, where overlapping paired-end reads were merged at a mismatch rate of 0.02. Chimeric regions were identified using the UCHIME algorithm and the corresponding sequences were processed and eradicated by referencing a known sequence database89. Non-chimeric reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). The generated OTU table was filtered further at the lowest non-zero frequency (4) to remove singletons. The feature OTU table was classified taxonomically using the SILVA_v138 database at a 97% similarity threshold and 80% confidence interval90. Non-bacterial sequences such as Chloroplast, mitochondria, unknown, and ambiguous taxa were filtered out following taxonomic classification.

Diversity analysis

The output files and the raw OTU table from Mothur were further proceeded to downstream analyses using the online Microbiome Analyst platform (http://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca)72,91. The analysis of bacterial composition and diversity indices (alpha and beta) was conducted by uploading the generated OTU table to Microbiome Analyst with default parameters92. The OTU table containing taxonomy was rarefied at an even minimumdefault depth. The final dataset was tested for normality and homogeneity of distribution. The effect of various treatments on bacterial communities was ascertained using the analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) at a 5% level of significance in SPSS Windows v22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A heatmap was generated based on the relative abundance of the taxonomic affiliation at the phylum level, using the Euclidean distance approach93. Group-wise comparative analyses were performed to measure Chao1, Shannon, Simpson and Fisher alpha diversity indices. The significant differences in alpha diversity were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test performed in SPSS (version 22.0). Beta-diversity was analyzed by Principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) for the profiling of beta diversity of the gut microbial communities in L. rohita and to assess the degree of similarity between them, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index and Analysis of Group Similarities (ANOSIM). A Venn diagram was further drawn using the “VennDiagram” tool in the R environment to illustrate the relationships between distinct and shared OTUs among different treatment groups94. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was performed using Microsoft Excel (XLStat 7.5, Addinsoft) to determine the explanatory effects of growth indices and CSO supplementation level on gut bacterial communities of L. rohita. The principal component variables with eigenvalues > 0.9 that explained at least 5% of the variance in data were considered the best representatives of system attributes95. Additionally, a correlation network was created based on the established relationship between the major bacterial phyla (> 1% relative abundance) using the Gephi software (Version 0.10.1) (10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937)96. The standard error of the mean with respect to each parameter was calculated. Finally, to predict the metabolic pathways based on 16 S rRNA sequences, the Piphillin pipeline (http://secondgenome.com/Piphillin) was utilized, leveraging the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database, BioCyc 21.0 databases, supported by the LEfSe algorithm97–100.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of the acquired data were conducted utilizing SPSS version 22.0 to assess significant variances between means. The standard error (SE) within the data was determined and presented as the mean ± standard error and checked for normality and homogeneity of variances employing Shapiro–Wilk’s and Levene’s tests. After validation of these two tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparision test was performed and confidence limits based on p ≤ 0.05 was employed among the treatment groups to compare significant differences.

Animal ethics declaration

The fish were finally sacrificed following the rules and regulations of the Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Ministry of Environment & Forests, Animal Welfare Division, Government of India, to collect the liver, distal gut and fecal matter from the intestine. The experimental design, husbandry protocol and fish sampling methods accomplished in this study were followed as per the applicable international and national, guidelines for the care and use of animals in research. The study protocols were approved by the research authorities of the ICAR-Indian Institute of Agricultural Biotechnology, Ranchi, India. It is also confirmed that the study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their heartfelt gratitude to the active support of the staff members of School of Molecular Diagnostics, Prophylactics and Nanobiotechnology (SMDPN), and the Director and Joint Director (Research) of ICAR-Indian Institute of Agricultural Biotechnology (IIAB), Ranchi for their cooperation and assistance in carrying out the research work. First author sincerely acknowledges the support and assistance of Dr. Manisha Priyam (DBT-RA) in laboratory work.

Abbreviations

- CSO

Chia seed oil

- FO

Fish oil

- FCE

Feed conversion efficiency

- FCR

Feed conversion ratio

- HSI

Hepatosomatic index

- ISI

Intestinal somatic index

- OTU

Operational taxonomic unit

- PCA

Principle component analysis

- PCoA

Principle coordinate analysis

- PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- SGR

Specific growth rate

- VO

Vegetable oil

- WG

Weight gain

Author contributions

SKG and AG contributed to the study conception, design, first draft preparation, methodology, validation, final revision and editing. JSC and MJF contributed to microbiome analysis and reviewed the first draft. RG performed formal analysis and growth calculation. BS and KKK contributed to final review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Raw 16 S rRNA sequencing data generated in the study has been deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject ID PRJNA1066701. All other data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sanjay Kumar Gupta and Akruti Gupta have contributed equally to the study and share the first authorship.

References

- 1.Tacon, A. G. J., Metian, M. & McNevin, A. A. Future feeds: Suggested guidelines for sustainable development. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 30, 271–279. 10.1080/23308249.2021.1898539 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeoti, I. A. & Hawboldt, K. A review of lipid extraction from fish processing by-product for use as a biofuel. Biomass Bioenerg.63, 330–340. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.02.011 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alhazzaa, R., Nichols, P. D. & Carter, C. G. Sustainable alternatives to dietary fish oil in tropical fish aquaculture. Rev. Aquac.11, 1195–1218. 10.1111/raq.12287 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollingsworth, A. Sustainable diets: The gulf between management strategies and the nutritional demand for fish. World Sustain. Ser. 711–725. 10.1007/978-3-319-63007-6_44 (2018).

- 5.Martin, S. A. M. & Król, E. Nutrigenomics and immune function in fish: New insights from omics technologies. Dev. Comp. Immunol.75, 86–98. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.024 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turchini, G. M., Torstensen, B. E. & Ng, W. K. Fish oil replacement in finfish nutrition. Rev. Aquac.1(1), 10–57. 10.1111/j.1753-5131.2008.01001.x (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turchini, G. M., Trushenski, J. T. & Glencross, B. D. Thoughts for the future of aquaculture nutrition: Realigning perspectives to reflect contemporary issues related to judicious use of marine resources in aquafeeds. North. Am. J. Aquac.81(1), 13–39. 10.1002/naaq.10067 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwasek, K., Thorne-Lyman, A. L. & Phillips, M. Can human nutrition be improved through better fish feeding practices? A review paper. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.60(22), 3822–3835. 10.1080/10408398.2019.1708698 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cottrell, R. S., Blanchard, J. L., Halpern, B. S., Metian, M. & Froehlich, H. E. Global adoption of novel aquaculture feeds could substantially reduce forage fish demand by 2030. Nat. Food1(5), 301–308. 10.1038/s43016-020-0078-x (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huyben, D. et al. Effect of dietary oil from Camelina sativa on the growth performance, fillet fatty acid profile and gut microbiome of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). PeerJ8, e10430. 10.7717/peerj.10430 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulczy´nski, B., Kobus-Cisowska, J., Taczanowski, M., Kmiecik, D. & Gramza-Michalowska, A. The chemical composition and nutritional value of chia seeds – current state of knowledge. Nutrients11, 1242–1258. 10.3390/nu11061242 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodoira, R. M., Penci, M. C., Ribotta, P. D. & Martínez, M. L. Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) oil stability: Study of the effect of natural antioxidants. Lwt75, 107–113. 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.08.031 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Álvarez-Chávez, L. M., Valdivia-López, M. D. L. A., Aburto-Juárez, M. D. L. & Tecante, A. Chemical characterization of the lipid fraction of Mexican chia seed (Salvia hispanica L). Int. J. Food Prop.11, 687–697. 10.1080/10942910701622656 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva, L. T. et al. Hemato-immunological and zootechnical parameters of Nile tilapia fed essential oil of Mentha piperita after challenge with Streptococcus agalactiae. Aquaculture506, 205–211. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.03.035 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tocher, D. R., Betancor, M. B., Sprague, M., Olsen, R. E. & Napier, J. A. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA and DHA: Bridging the gap between supply and demand. Nutrients11, 1–20. 10.3390/nu11010089 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calder, C. P. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell. Biology Lipids1851(4), 469–484. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.010 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magalhães, R. et al. Effect of different dietary arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic, and docosahexaenoic acid content on selected immune parameters in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. Rep.2. 10.1016/j.fsirep.2021.100014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Parolini, C. Effects of fish n-3 PUFAs on intestinal microbiota and immune system. Mar. Drugs. 17(6), 374. 10.3390/md17060374 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasopoulou, C. & Zabetakis, I. Benefits of fish oil replacement by plant originated oils in compounded fish feeds. Rev. Lwt.47, 217–224. 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.01.018 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yıldız, M., Eroldoğan, T. O., Ofori-Mensah, S., Engin, K. & Baltacı, M. A. The effects of fish oil replacement by vegetable oils on growth performance and fatty acid profile of rainbow trout: Re-feeding with fish oil finishing diet improved the fatty acid composition. Aquaculture488, 123–133. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.12.030 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parata, L., Sammut, J. & Egan, S. Opportunities for microbiome research to enhance farmed freshwater fish quality and production. Rev. Aquac.13, 2027–2037. 10.1111/raq.12556 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, J., Piao, X., Mahfuz, S., Long, S. & Wang, J. The interaction among gut microbes, the intestinal barrier and short chain fatty acids. Anim. Nutr.9, 159–174. 10.1016/j.aninu.2021.09.012 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng, Y. et al. Gut–liver immune response and gut microbiota profiling reveal the pathogenic mechanisms of vibrio harveyi in pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ × E. fuscoguttatus ♀). Front. Immunol.11, 1–13. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.607754 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, H. et al. The gut microbiome and degradation enzyme activity of wild freshwater fishes influenced by their trophic levels. Sci. Rep.6(1), 24340. 10.1038/srep24340 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingerslev, H. C. et al. The development of the gut microbiota in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) is affected by first feeding and diet type. Aquaculture424, 24–34. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.12.032 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrecillas, S. et al. Effects of dietary concentrated mannan oligosaccharides supplementation on growth, gut mucosal immune system and liver lipid metabolism of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles. Fish Shellfish Immunol.42(2), 508–516. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.772570 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, F. J., Lin, X., Lin, S. M., Chen, W. Y. & Guan, Y. Effects of dietary fish oil substitution with linseed oil on growth, muscle fatty acid and metabolism of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquacult. Nutr.22(3), 499–508. 10.1111/anu.12270 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, X. et al. Synbiotic dietary supplement affects growth, immune responses and intestinal microbiota of Apostichopus japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol.68, 232–242. 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.07.027 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye, Z., Xu, Y. J. & Liu, Y. Influences of dietary oils and fats, and the accompanied minor content of components on the gut microbiota and gut inflammation: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol.113, 255–276. 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.05.001 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johny, T. K., Puthusseri, R. M. & Bhat, S. G. A primer on metagenomics and next-generation sequencing in fish gut microbiome research. Aquac. Res.52, 4574–4600. 10.1111/are.15373 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whiteside, S. A., Razvi, H., Dave, S., Reid, G. & Burton, J. P. The microbiome of the urinary tract - A role beyond infection. Nat. Rev. Urol.12, 81–90. 10.1038/nrurol.2014.361 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choudhary, J. S. et al. High taxonomic and functional diversity of bacterial communities associated with melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Curr. Microbiol.78, 611–623. 10.1007/s00284-020-02327-2 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banra, S. et al. Bacterial communities and their predicted function change with the life stages of invasive C–strain Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. 1797) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Invasions. 10.1007/s10530-024-03288-4 (2024)

- 34.Xia, Y., Yu, E. M., Lu, M. & Xie, J. J. A. Effects of probiotic supplementation on gut microbiota as well as metabolite profiles within Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture527, 735428. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735428 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou, Z., Ringø, E., Olsen, R. E. & Song, S. K. Dietary effects of soybean products on gut microbiota and immunity of aquatic animals: A review. Aquacult. Nutr.24 (1), 644–665. 10.1111/anu.12532 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salem, M. O. A., Taştan, Y., Bilen, S., Terzi, E. & Sönmez, A. Y. Dietary flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) oil supplementation affects growth, oxidative stress, immune response, and diseases resistance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Shellfish Immunol.138, 108798. 10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108798 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elkaradawy, A., Abdel-Rahim, M. M. & Mohamed, R. A. Quillaja saponaria and/or linseed oil improved growth performance, water quality, welfare profile and immune‐oxidative status of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus fingerlings. Aquac. Res.53(2), 576–589. 10.1111/are.15602 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.You, C. et al. Effects of dietary lipid sources on the intestinal microbiome and health of golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Fish Shellfish Immunol.89, 187–197. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.060 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Castro, C. et al. Vegetable oil and carbohydrate-rich diets marginally affected intestine histomorphology, digestive enzymes activities, and gut microbiota of gilthead sea bream juveniles. Fish Physiol. Biochem.45, 681–695. 10.1007/s10695-018-0579-9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.FAO Sustainability in Action. State World Fisheries Aquaculture, Rome. 10.5860/choice.50-5350 (2020).

- 41.Foysal, M. J. et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals significant variations in bacterial compositions across the gastrointestinal tracts of the Indian major carps, rohu (Labeo rohita), catla (Catla catla) and mrigal (Cirrhinus cirrhosis). Lett. Appl. Microbiol.70, 173–180. 10.1111/lam.13256 (2020b). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyagi, A., Singh, B., Thammegowda, B., Singh, N. K. & N.K Shotgun metagenomics offers novel insights into taxonomic compositions, metabolic pathways and antibiotic resistance genes in fish gut microbiome. Arch. Microbiol.201, 295–303. 10.1007/s00203-018-1615-y (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukherjee, A., Rodiles, A., Merrifield, D. L., Chandra, G. & Ghosh, K. Exploring intestinal microbiome composition in three Indian major carps under polyculture system: A high-throughput sequencing based approach. Aquaculture524. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735206 (2020).

- 44.Maji, U. J. et al. Exploring the gut microbiota composition of Indian major carp, rohu (Labeo rohita), under diverse culture conditions. Genomics114. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110354 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Feng, H. et al. Dietary supplementation with emodin affects growth and gut health by modulating the gut microbiota of common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquac Rep.35, 101962. 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101962 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochang, S. N., Fagbenro, O. A. & Adebayo, O. T. Influence of dietary palm oil on growth response, carcasscomposition, haematology and organoleptic properties of juvenile Nile tilapia. Oreochromis Niloticus Pak J. Nutr.6(5), 424–429. 10.3923/pjn.2007.424.429 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demir, O., Türker, A., Acar, Ü. & Kesbiç, O. S. Effects of dietary fish oil replacement by unrefined peanutoil on the growth, serum biochemical and hematological parameters of Mozambique tilapia juveniles (Oreochromis mossambicus). Turk. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci.14, 887–892. 10.4194/1303-2712-v14_4_06 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun, S., Ye, J., Chen, J., Wang, Y. & Chen, L. Effect of dietary fish oil replacement by rapeseed oil on the growth, fatty acid composition and serum non-specific immunity response of fingerling black carp. Mylopharyngodon Piceus Aquac. Nutr.17(4), 441–450. 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2010.00822.x (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahrooz, R. et al. Effects of fish oil replacement with vegetable oils in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fingerlings diet on growth performance and foregut histology. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.18(6), 825–832. 10.4194/1303-2712-v18_6_09 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ayisi, C. L., Zhao, J. & Wu, J. W. Replacement of fish oil with palm oil: Effects on growth performance, innate immune response, antioxidant capacity and disease resistance in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). PLoS One13, 1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196100 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abd El-Naby, A. S., El Asely, A. M., Hussein, M. N., Fawzy, R. M. & Abdel-Tawwab, M. Stimulatory effects of dietary chia (Salvia hispanica) seeds on performance, antioxidant-immune indices, histopathological architecture, and disease resistance of Nile tilapia. Aquaculture563, 738889. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738889 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen, T. M. et al. Growth performance and immune status in common carp Cyprinus carpio as affected by plant oil-based diets complemented with β-glucan. Fish Shellfish Immunol.92, 288–299. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asghar, M. et al. Feasibility of replacing fish oil with sunflower oil on the growth, body composition, fatty acid profile, antioxidant activity, stress response, and blood biomarkers of Labeo rohita. PLoS One19, 1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0299195 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ofori-Mensah, S., Yıldız, M., Arslan, M., Eldem, V. & Gelibolu, S. Substitution of fish oil with camelina or chia oils in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L.) diets: Effect on growth performance, fatty acid composition, haematology and gene expression. Aquac Nutr.26, 1943–1957. 10.1111/anu.13136 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jha, A. K., Pal, A. K., Sahu, N. P., Kumar, S. & Mukherjee, S. C. Haemato-immunological responses to dietary yeast RNA, ω-3 fatty acid and β-carotene in Catla catla juveniles. Fish Shellfish Immunol.23(5), 917–927. 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.01.011 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim, K. D. & Lee, S. M. Requirement of dietary n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids for juvenile flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture229(1–4), 315–323. 10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00356 (2004).

- 57.Lochmann, R. T. & Gatlin, D. M. 3rd. Essential fatty acid requirement of juvenile red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus). Fish Physiol. Biochem.12(3), 221 – 35. 10.1007/BF00004370 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Siddik, M. A. B. et al. Influence of fish protein hydrolysate produced from industrial residues on antioxidant activity, cytokine expression and gut microbial communities in juvenile barramundi Lates calcarifer. Fish. Shellfish Immunol.97, 465–473. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.12.057 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khalid, W. et al. Chia seeds (Salvia hispanica L.): A therapeutic weapon in metabolic disorders. Food Sci. Nutr.11, 3–16. 10.1002/fsn3.3035 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guangxin, G. et al. Improvements of immune genes and intestinal microbiota composition of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) with dietary oregano oil and probiotics. Aquaculture547, 737442. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737442 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reveco, F. E., Øverland, M., Romarheim, O. H. & Mydland, L. T. Intestinal bacterial community structure differs between healthy and inflamed intestines in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L). Aquaculture420–421, 262–269. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.11.007 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiu, Z. et al. Effects of soybean oligosaccharides instead of glucose on growth, digestion, antioxidant capacity and intestinal flora of crucian carp cultured in biofloc system. Aquac. Rep.29, 101512. 10.1016/j.aqrep.2023.101512 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ceppa, F. et al. Influence of essential oils in diet and life-stage on gut microbiota and fillet quality of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr.69, 318–333. 10.1080/09637486.2017.1370699 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan, M. F. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of bacterial pathogens isolated from poultry in Jiangxi Province, China from 2020 to 2022. Poult. Sci.102, 1–8. 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102830 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ullah, S. et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of lauric acid on growth performance, antioxidative capacity, intestinal development and gut microbiota on black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). PLoS ONE17(1), e0262427. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262427 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, C. et al. Effects of plant-derived protein and rapeseed oil on growth performance and gut microbiomes in rainbow trout. BMC Microbiol.23, 1–14. 10.1186/s12866-023-02998-4 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin, N. R., Whon, T. W. & Bae, J. W. Proteobacteria: Microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol.33(9), 496–503. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Desai, A. R. et al. Effects of plant-based diets on the distal gut microbiome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 350–353. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.04.005 (2012).

- 69.Choi, J. S., Yoon, H., Heo, Y., Kim, T. H. & Park, J. W. Comparison of gut toxicity and microbiome effects in zebrafish exposed to polypropylene microplastics: Interesting effects of UV-weathering on microbiome. J. Hazard. Mater.470, 134209. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134209 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foysal, M. et al. Meta-omics technologies reveals beneficiary effects of Lactobacillus plantarum as dietary supplements on gut microbiota, immune response and disease resistance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture520, 734974. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.734974 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cai, X. et al. Altered diversity and composition of gut microbiota in Wilson’s disease. Sci. Rep.10, 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-020-78988-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zaminhan-Hassemer, M. et al. Adding an essential oil blend to the diet of juvenile Nile tilapia improves growth and alters the gut microbiota. Aquaculture560, 738581. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738581 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang, A. et al. Intestinal Cetobacterium and acetate modify glucose homeostasis via parasympathetic activation in zebrafish. Gut Microbes. 13, 1–15. 10.1080/19490976.2021.1900996 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, R., Wang, X. W., Liu, L. L., Cao, Y. C. & Zhu, H. Dietary oregano essential oil improved the immune response, activity of digestive enzymes, and intestinal microbiota of the koi carp, Cyprinus carpio. Aquaculture518, 734781. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734781 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao, Y., Li, S., Lessing, D. J., Guo, L. & Chu, W. Characterization of Cetobacterium somerae CPU-CS01 isolated from the intestine of healthy crucian carp (Carassius auratus) as potential probiotics against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Microb. Pathog. 180, 106148. 10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106148 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qi, X. et al. Vitamin B12 produced by Cetobacterium somerae improves host resistance against pathogen infection through strengthening the interactions within gut microbiota. Microbiome11, 1–25. 10.1186/s40168-023-01574-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Idenyi, J. N. et al. Genome-wide insights into whole gut microbiota of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, fed plant proteins and camelina oil at different temperature regimens. J. World Aquac. Soc.55(2), e13028. 10.1111/jwas.13028 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 78.You, C. et al. Effects of dietary lipid sources on the intestinal microbiome and health of golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Fish. Shellfish Immunol.89, 187–197. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.060 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob Ecol. Biogeogr.19, 134–143. 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00490.x (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morowitz, M. J., Carlisle, E. M. & Alverdy, J. C. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg. Clin. North. Am.91, 771–785. 10.1016/j.suc.2011.05.001 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dang, Y. et al. Effects of dietary oregano essential oil-mediated intestinal microbiota and transcription on amino acid metabolism and Aeromonas salmonicida resistance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquacult. Int.32(2), 1835–1855. 10.1007/s10499-023-01246-w (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu, Y., Liu, X., Liu, W. & Ye, B. Identification and characterization of two types of amino acid-regulated acetyltransferases in actinobacteria. Biosci. Rep.37(4), BSR20170157. 10.1042/BSR20170157 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rimoldi, S., Antonini, M., Gasco, L., Moroni, F. & Terova, G. Intestinal microbial communities of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) may be improved by feeding a Hermetia illucens meal/low-fishmeal diet. Fish. Physiol. Biochem.47, 365–380. 10.1007/s10695-020-00918-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Fish and Shrimp(National Academies, 2011).

- 85.Mohanty, B. P. et al. DHA and EPA content and fatty acid profile of 39 food fishes from India. BioMed. Res. Int.2016, 4027437. 10.1155/2016/4027437 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Kozich, J. J., Westcott, S. L., Baxter, N. T., Highlander, S. K. & Schloss, P. D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the miseq illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.79, 5112–5120. 10.1128/AEM.01043-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics32, 3047–3048. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krueger, F., James, F., Ewels, P., Afyounian, E. & Schuster-Boeckler, B. FelixKrueger/TrimGalore: v0.6.7 - DOI via Zenodo (0.6.7). Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.5127899 (2021).

- 89.Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open-source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ2016, 1–22. 10.7717/peerj.2584 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res.41, 590–596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu, Y. et al. MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0: Comprehensive statistical, functional and integrative analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res.51, W310–W318. 10.1093/nar/gkad407 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feng, H. et al. Ocular bacterial signatures of exophthalmic disease in farmed turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Aquac. Res.51, 2303–2313. 10.1111/are.14574 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dhariwal, A. et al. MicrobiomeAnalyst: A web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res.45, W180–W188. 10.1093/nar/gkx295 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: A package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform.12, 35–41. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kumar, R. et al. Influence of conservation agriculture-based production systems on bacterial diversity and soil quality in rice-wheat-greengram cropping system in eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Front. Microbiol.14, 1–17. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1181317 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]