ABSTRACT

Aims

To discuss the role of screening and treatment of affective symptoms, like anxiety and depression in patients with LUTD. A review of the literature regarding the bidirectional association and multidisciplinary approaches integrating psychometric assessments with personalized treatment plans to improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes of LUTD.

Methods

This review summarizes discussions and a narrative review of (recent) literature during an International Consultation on Incontinence‐Research Society 2024 research proposal with respect to the role of screening for anxiety and depression, effect of mental health symptoms on treatment outcomes and future implications.

Results

Consensus recognized the importance to incorporate attention to anxiety and depression in relation to LUTD. The awareness of this association can lead to better outcomes. Future research projects are proposed to evaluate the bidirectional relationship.

Conclusion

The relationship between affective symptoms and LUTD underscores the need for integrated treatment approaches that address both psychological and urological dimensions. Further research is required to identify specific patient subgroups that would benefit most from these interventions, to develop standardized screening tools, and to refine treatment protocols. Multidisciplinary care, incorporating psychological assessment and personalized treatment strategies, could enhance outcomes for LUTD patients.

1. Introduction

The relationship between affective symptoms (AS) such as anxiety and depression and lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), particularly in patients with overactive bladder (OAB), has garnered significant attention in recent research [1]. LUTD is not only prevalent but can also pose substantial challenges due to the sometimes chronic nature and resistance to conventional treatments for LUTD. Emerging evidence suggests that untreated psychological and psychiatric conditions may underpin these poor treatment outcomes, indicating a vital intersection between AS and LUTD [2, 3].

Epidemiological data underscore the prevalence and co‐occurrence of AS and LUTD. For instance, a study conducted in a tertiary referral center found that 30.9% of patients with pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFDs), including OAB, reported anxiety while 20.3% reported depression [4]. Furthermore, longitudinal studies indicate that not only are individuals with OAB at an increased risk of developing depression and anxiety, but those with pre‐existing affective disorders are also more likely to develop OAB [1].

Multiple pathways provide plausible explanations for this relationship, suggesting new assessment methods for these patients, such as psychological assessment. The interplay between anxiety, depression and OAB can be understood through the bladder‐gut‐brain axis (BGBA), a theoretical framework that elucidates how emotional and bodily distress manifest as functional disorders. This model proposes that early‐life stressors, such as childhood adversity and traumatic events, can sensitize individuals to perceive greater emotional and physical threats, contributing to the onset of functional urological symptoms. This sensitization may be mediated by neurobiological pathways involving serotonin, stress response mechanisms and inflammation, which are all common denominators in both affective disorders and OAB [2]. Serotonin as a key neurotransmitter implicated in mood regulation has also been associated with bladder function. Dysregulation of serotonin pathways can lead to both mood disorders and LUTD, suggesting a shared pathophysiological basis. Additionally, chronic stress and inflammation, known contributors to anxiety and depression, can exacerbate OAB symptoms through neurogenic inflammation and altered bladder signaling [5]. Life events that heighten stress, such as sexual abuse, can trigger or worsen both AS and OAB, further illustrating the interdependence of these conditions [6].

In summary, the bidirectional relationship between AS and LUTD suggests that comprehensive management should encompass both psychological and urological dimensions. A proposal at the 11th International Consultation on Incontinence—Research Society (ICI‐RS 2024) meeting reviewed current literature on this topic and discussed multidisciplinary approaches integrating psychological assessment using psychometrically validated instruments with personalized treatment plans, essential to improving diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes of LUTD. A comprehensive summary and discussion are presented in this article.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Anxiety and Depression on Treatment Seeking and Outcomes

The literature addressing both treatment seeking and treatment outcomes in patients with LUTD is notably scarce.

A single study focusing on women with OAB revealed that symptoms of depression, anger, isolation and hopelessness were more prevalent in those seeking treatment for the condition. However, multivariate analysis indicated that affective disorders were not significant predictors of treatment seeking [7, 8]. Additionally, a short report on health behaviours in patients with and without neurological disease and UUI (mostly UUI, but also stress urinary incontinence [SUI], or MUI) suggested an association with higher levels of embarrassment and fear associated with doctor's visits in those patients using psychotropic medication. These patients also demonstrated poorer decision‐making regarding treatment‐seeking and were less likely to adhere to treatment programs compared to those not on psychotropic medication [9].

Large, longitudinal studies using validated health‐behavior questionnaires are necessary to investigate patients' attitudes toward seeking, initiating and adhering to treatment for LUTD. Comparing the incidence of depression, stress and anxiety in individuals with LUTD who seek treatment versus those who do not, as well as assessing psychometric and quality of life measures before and after treatment, would be valuable. These findings could also determine if screening for subclinical cases of increased stress, anxiety, and depression could enhance our clinical practice.

In contrast, there is extensive research available concerning the impact of affective disorders on treatment outcomes for LUTD. Almost all published studies support this, independently from biological sex and LUTD condition [10, 11]. In male patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), depression, anxiety and somatization were found to negatively affect treatment response, while pre‐diagnostic levels of psychological distress were correlated with adverse events after radical prostatectomy [12, 13]. Furthermore, depression and lower rating of shared decision making were associated with decisional regret regarding treatment of SUI in males [14]. Among women seeking treatment for SUI, OAB or bladder outlet obstruction symptoms, an increase in baseline depression levels was found to be associated with increases in LUTS and Pelvic Floor distress severity in validated questionnaires [15]. Conversely, in women undergoing pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), higher pre‐treatment depression levels were associated with greater severity of bladder symptoms and worse treatment response at the end of the PFMT program [8]. Lastly, the absence of baseline anxiety or depression was one of the factors associated with greater improvement in stress, urgency or mixed UI outcomes when comparing interventions administered by nurse specialists to standard care in a cohort of patients with UUI, SUI, or MUI [16].

2.2. Treatment of Anxiety and Depression and the Effect on LUTD

Given the bidirectional association between LUTS and affective disorders, it is hypothesized that treating affective disorders with psychological therapy or medical therapy, including antidepressants or anxiolytics, may alleviate troublesome LUTD. However, research on this topic is sparse and examples in current literature are presented.

In the context of psychological therapy, Stanton et al. conducted a randomized study involving 50 patients with detrusor overactivity or increased bladder sensation. Participants were assigned to either eclectic psychotherapy, a multi‐modal individualised psychotherapy approach, (n = 19), bladder retraining (n = 16), or propantheline 15 mg three times daily (n = 15). Patients in the “eclectic psychotherapy” group were seen by a psychiatrist for eight to 12 weekly sessions of 50 min, designed to offer the non‐symptom oriented measures of support, counselling, and anxiety reducing techniques. The psychotherapy group reported a statistically significant improvement in nocturia, urinary urgency scores, and episodes of UUI, compared to the other two treatment groups [17].

A randomized controlled trial involving 192 men with prostate cancer were randomized to either a cognitive‐behavioral stress management (CBSM) module delivered on an electronic table or a health promotion condition and followed for 1 year. Those in the CBSM arm showed a statistically significant decrease in urinary incontinence episodes as well as urinary bother and bowel dysfunction on the Extended Prostate Cancer Index Composite‐26 (EPIC‐26) questionnaire at 6 and 12 month follow up [18].

Van Knippenberg et al conducted a retrospective cohort study on 77 patients with refractory OAB, bladder pain syndrome and chronic pelvic pain syndrome, suspected psychiatric co‐morbidities, and no organic cause of their symptoms. The value of multidisciplinary team (MDT) care was assessed, including a psychiatrist providing pharmacological treatment and/or psychotherapy (cognitive brain therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy etc.). Patients treated with the MDT approach showed a statistically significant reduction in depression scores, reduced medication usage, and improved quality of life and functional bladder symptoms on PGI‐I questionnaires [19]

In a small open‐label, single‐arm pilot study, 10 patients (median age: 72 years) with drug‐resistant OAB underwent a face‐to‐face intervention consisting of six 30‐min sessions over 6−12 weeks. Outcomes were assessed using self‐reported questionnaires and frequency voiding charts (FVC) at baseline, during, post‐intervention, and follow‐up. Two participants dropped out, but among the remaining eight, OAB Questionnaire subscale scores improved (effect size: 0.75–1.73), and mean urinary frequency decreased from 9.0 (SD: 2.1) to 6.2 (SD: 1.2) voids per day. Participants reported satisfaction with no adverse events observed [20].

In a study on medical therapy for affective disorders, 306 women with OAB symptoms, were treated with either duloxetine (an SNRI) or a placebo. Those on duloxetine, starting at 40 mg and increasing to 60 mg twice daily after 4 weeks, demonstrated a significant reduction in voiding episodes, increased daytime voiding intervals and reduced urgency incontinence from baseline to 12 weeks. Additionally, duloxetine significantly improved “avoidance and limiting behaviour” and “psychosocial impact” scores in the Incontinence Quality of Life (IQOL) questionnaire [21]. Duloxetine, which is licensed for treatment of affective disorders, has been shown to improve symptoms of both depression and anxiety in adults [22, 23].

Current literature suggests that treating affective disorders with psychological therapy or antidepressants may improve LUTD, particularly in patients with refractory symptoms with significant psychological comorbidities. Further research is necessary to identify which patients warrant psychiatric evaluation, which subgroups would benefit from treating affective disorders to improve their LUTD, and whether combined medical therapy is effective for managing both LUTD and affective disorders.

2.3. Screening and Which Instrument to Use

Although numerous screening measures for affective disorders have been developed, there is no clear expert consensus on the implementation of these tools for assessing AS, such as anxiety and depression, in patients with LUTD. Patients who score at or above a pre‐determined cut‐off on the screening scale should be interviewed more thoroughly and a risk assessment undertaken [24].

When selecting a tool, researchers should consider the psychometric properties of the scale for example, validity, reliability, sensitivity and specificity. Various screening questionnaires have been used to assess AS in patients with LUTS, detailed in the review by Vrijens [1]. The literature suggests several questionnaires to generally screen for affective disorders such as “Hospital anxiety (and depression) scale (HADS)” and the “Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM‐5 (PC‐PTSD‐5)” [1, 6].

There is a need for a uniform screening tool to address potential symptoms of underlying affective disorders in new LUTD patients. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) is a self‐administered version of the PRIME‐MD diagnostic instrument for common mental disorders and consists of 9 depression module items [25]. A recent systematic review found it to be the most extensively psychometrically tested screening tool for depression among adults in primary health care [26] The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) questionnaire is a 7‐item anxiety scale [27]. While the PHQ‐9 and the GAD‐7 are widely used in combination in the UK, they might be considered time‐consuming for routine screening in LUTD patients.

Briefer screening scales such as the two‐item GAD‐2 and the two‐item PHQ‐2 are suitable primary screening tools for anxiety and depressive symptoms [28, 29, 30]. The PHQ‐4 scale, which combines the GAD‐2 and the PHQ‐2 has been shown to be reliable with normative data reported [31]. Although these scales have been validated, (i.e., their psychometric properties such as reliability and validity have been assessed) for use in a number of contexts [28] there is little published evidence of their use in patients with LUTD. The PHQ‐4 scale is likely to be brief enough for routine use. However, if screening is needed for “Bladder symptoms causing anxiety or depression,” a new LUTD‐specific anxiety/depression scale could be developed. Future research needs to clarify these possible modifications.

3. Discussion

3.1. OAB Subgroups and AS

It is widely recognized that there is an association between various subgroups of LUTD patients and their susceptibility to AS. Identifying these subgroups is essential before developing a structured assessment protocol, which may include a systematic screening program for AS.

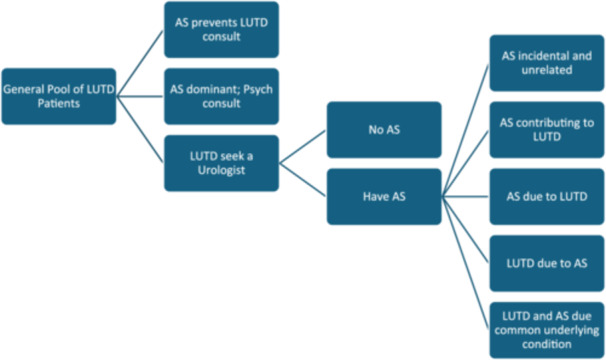

OAB and AS are prevalent in the general population [32]. The term OAB is used without regard to the underlying pathophysiology of the condition. The potential co‐existence of OAB and AS in a given patient can be explored through a theoretical model with hypothesis for clinical presentation (Figure 1). Such a model can help envisage this potential interaction and its implications for clinical care. Although OAB is often described as an idiopathic condition, this may reflect our current inability to understand the underlying pathophysiology rather than indicating a genuine absence of underlying disease. Significant progress has been made in demonstrating that various abnormalities could involve different levels of the afferent pathways, ranging from the bladder to cortical pathways in the brain [33] AS could potentially influence several points in these pathways. There is evidence suggesting that AS can either contribute to the development of OAB, result from OAB, or that both conditions might arise from a common underlying abnormality at the brain level [32, 34, 35].

Figure 1.

Theoretical model with hypothesis for clinical presentation of LUTD patients with coexisting affective symptoms (AS).

3.1.1. Different Etiologies of LUTD

Further research is needed to verify other predisposing factors that contribute to the presence of affective or depressive symptoms in patients with LUTS. Identifying these factors could help differentiate between various etiologies and subgroups of LUTD, each uniquely related to AS. Longitudinal studies have shown that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including sexual and emotional abuse, are associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal intentions during puberty and adulthood, as well as an increased likelihood of urinary incontinence. Disrupted stress responses and impaired neurodevelopment from childhood can predispose individuals to both LUTD and affective disorders [36, 37].

The urinary and gut microbiomes also differ among patients. Although not yet substantiated in prospective studies, different coping mechanisms and pathogeneses for LUTD related to the urothelium and urinary microbiota can be hypothesized [38, 39].

These factors collectively influence the severity, persistence, and treatment response in OAB patients. The concept of individual vulnerability and resilience to adversities in functional urological disorders has been described by Leue et al., who proposed a three‐hit model encompassing genetic predisposition, early‐life environment, and later‐life environment [2]. Negative health beliefs, cognitive coping strategies and personality traits contribute to stress sensitivity and the severity of functional disorders, thereby increasing stress‐related vulnerability. Early adversities are also considered mediators for genetic, emotional and behavioural adaptations to threats later in life, shaping an individual's resilience to adversity.

3.2. Future Research

Future research questions and possible study methods are elaborated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Future research questions on present inconsistencies and gaps in assessment of affective symptoms in LUTD patients with proposed future study methods.

| Future research questions | Study methods |

|---|---|

| How do serotonin dysregulation, chronic stress, and inflammation interact to influence both mood disorders and lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD)? | Longitudinal Cohort Studies with biomarker analysis |

| Basic science animal studies | |

| What is the role of chronic stress in the development and progression of LUTD and how does it intersect with mood disorders at a neurobiological level? | Cohort studies with stress assessments and urinary function tests |

| How effective are psychological therapies such as cognitive‐behavioral stress management and eclectic psychotherapy in alleviating LUTD symptoms? | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| Meta‐analyses | |

| How does treatment seeking for LUTD impact levels of depression, stress, anxiety and quality of life, compared to individuals with LUTD who do not seek treatment? | Cross‐Sectional Study |

| Prospective Cohort Studies | |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | |

| Qualitative Interviews | |

| What methodological improvements can be implemented in future randomized controlled trials to address inconsistent results on psychological interventions for LUTD? | Systematic Reviews |

| Meta‐Analyses | |

| RCTs with larger sample sizes, longer follow‐up periods and standardized protocols | |

| What consensus can be reached among experts in urology, urogynecology, psychology, and psychiatry on the assessment of LUTD and associated affective symptoms? | Delphi Study |

| How can AI‐driven tools, such as chatbots and digital platforms, be designed and implemented to improve self‐management and mental health screening in patients with LUTD? | Systematic Reviews |

| Mixed Methods studies | |

| Cohort Feasibility Studies | |

| RCTs |

While theoretical models such as the BGBA provide plausible explanations for the interplay between AS and OAB, the exact neurobiological pathways and mechanisms remain inadequately understood. Further research is needed to elucidate how serotonin dysregulation, chronic stress, and inflammation specifically contribute to both mood disorders and LUTD.

Existing studies on the effect of psychological therapies, such as CBSM and eclectic psychotherapy, on LUTD are limited and often yield inconsistent results. More rigorous randomized controlled trials are required to establish the efficacy and mechanisms by which psychological interventions can alleviate LUTD symptoms.

Artificial intelligence could offer promising future prospects in the management of LUTD and associated AS by facilitating a homogeneous, holistic assessment of patients’ symptoms. AI applications—such as chatbots for pre‐consultation support, machine learning models that analyze extensive health datasets to uncover non‐obvious patterns, and predictive modeling for personalized treatment plans—can help identify patients who will benefit most from targeted screening and interventions, potentially improving adherence to treatments and reducing long‐term healthcare costs. Effective implementation of these tools will require careful consideration of patient feasibility, especially among the elderly with cognitive or motor impairments, and providing education to support their use of digital technologies.

To provide practical guidance and evidence‐based management, a possible future research project could be to set up a Delphi process among experts in the field of urology, urogynecology, psychology and psychiatrists.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the bidirectional relationship between AS and LUTD in patients with LUTD highlights the necessity of addressing both psychological and urological aspects in treatment. The combination of anxiety, depression, and OAB symptoms, possibly mediated by the BGBA, suggests that early psychological interventions and tailored medical therapies could significantly improve patient outcomes. Current research indicates that treating affective disorders with psychological therapy or antidepressants may improve LUTD symptoms, especially in patients with refractory symptoms or significant psychological comorbidities. The most challenging part is to determine which subgroup of patients with LUTD would benefit the most. Therefore, further large‐scale, longitudinal studies are essential to specify the specific patient subgroups that would benefit most from these interventions and to develop comprehensive screening and treatment protocols. Embracing a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating AS screening, and potentially utilizing AI for personalized treatment plans could alter the management of LUTD. Clinicians should be aware of the interaction of AS and LUTD.

Author Contributions

Mauro Van den Ende: This author collected data, wrote the first draft, revised the manuscript, finalized the manuscript and contributed as first author. Apostolos Apostolidis: This author collected data, wrote down results and revised the manuscript. Sanjay Sinha: This author collected data, wrote down results and revised the manuscript. George Bou Kheir: This author collected data, wrote down results and revised the manuscript. Rayan Mohamed‐Ahmed: This author collected data, wrote down results and revised the manuscript. Caroline Selai: This author collected data, wrote down results and revised the manuscript. Paul Abrams: This author revised the manuscript and contributed as last author. Desiree Vrijens: This author collected data, wrote the first draft, revised the manuscript, finalized the manuscript and contributed as last author.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This paper is an expert consensus paper of current literature after a meeting with expert presentations the ICI‐RS 2024 in Bristol. Therefore this paper did not require a clinical trial registration.

No permission to reproduce material from other sources was needed as we did not copy, reproduce, distribute, publish, display, perform, modify, create derivative works, transmit or in any way exploit any such content without proper referencing.

This is no systematic review and therefore does not need a PRISMA checklist.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1. Vrijens D., Drossaerts J., van Koeveringe G., Van Kerrebroeck P., van Os J., and Leue C., “Affective Symptoms and the Overactive Bladder—A Systematic Review,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 78, no. 2 (2015): 95–108, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leue C., Kruimel J., Vrijens D., Masclee A., van Os J., and van Koeveringe G., “Functional Urological Disorders: A Sensitized Defence Response in the Bladder–Gut–Brain Axis,” Nature Reviews Urology 14, no. 3 (2017): 153–163, 10.1038/nrurol.2016.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson D. J., Aucoin A., Toups C. R., et al., “Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Depression: A Review,” Health Psychology Research 11 (2023), 10.52965/001c.81040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vrijens D., Berghmans B., Nieman F., van Os J., van Koeveringe G., and Leue C., “Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms and Their Association With Pelvic Floor Dysfunctions‐A Cross Sectional Cohort Study at a Pelvic Care Centre,” Neurourology and Urodynamics 36, no. 7 (2017): 1816–1823, 10.1002/nau.23186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hughes F. M., Odom M. R., Cervantes A., Livingston A. J., and Purves J. T., “Why Are Some People With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) Depressed? New Evidence That Peripheral Inflammation in the Bladder Causes Central Inflammation and Mood Disorders,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 3 (2023): 2821, 10.3390/ijms24032821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selai C., Elmalem M. S., Chartier‐Kastler E., et al., “Systematic Review Exploring the Relationship Between Sexual Abuse and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms,” International Urogynecology Journal 34, no. 3 (2023): 635–653, 10.1007/s00192-022-05277-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. LaPier Z., Jericevic D., Lang D., Gregg S., Brucker B., and Escobar C., “Predictors of Care‐Seeking Behavior for Treatment of Urinary Incontinence in Women,” Urogynecology 30, no. 3 (2024): 352–362, 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Osborne L. A., Mair Whittall C., Emery S., and Reed P., “Change in Depression Predicts Change in Bladder Symptoms for Women With Urinary Incontinence Undergoing Pelvic‐Floor Muscle Training,” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 280 (2023): 54–59, 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michailidou S., Holeva V., Damianidou K., Samarinas M., Delithanasi A., and Apostolidis A., “Health Behaviours, Quality of Life and Treatment Adherence in Neurogenic Versus Non‐Neurogenic Urinary Incontinence,” ICS 2019 Gothenburg (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goode P. S., “Predictors of Treatment Response to Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Urinary Incontinence,” Gastroenterology 126 (2004): S141–S145, 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tadic S. D., Zdaniuk B., Griffiths D., Rosenberg L., Schäfer W., and Resnick N. M., “Effect of Biofeedback on Psychological Burden and Symptoms in Older Women With Urge Urinary Incontinence,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55, no. 12 (2007): 2010–2015, 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang Y. J., Koh J. S., Ko H. J., et al., “The Influence of Depression, Anxiety and Somatization on the Clinical Symptoms and Treatment Response in Patients With Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Suggestive of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” Journal of Korean Medical Science 29, no. 8 (2014): 1145, 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.8.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nilsson R., Næss‐Andresen T., Myklebust T. Å., Bernklev T., Kersten H., and Haug E. S., “The Association Between Pre‐Diagnostic Levels of Psychological Distress and Adverse Effects After Radical Prostatectomy,” BJUI Compass 5, no. 5 (2024): 616–625, 10.1002/bco2.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hampson L. A., Suskind A. M., Breyer B. N., et al., “Predictors of Regret Among Older Men After Stress Urinary Incontinence Treatment Decisions,” Journal of Urology 207, no. 4 (2022): 885–892, 10.1097/JU.0000000000002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith A. R., Mansfield S. A., Bradley C. S., et al., “Relationships Between Urinary and Nonurinary Symptoms in Treatment‐Seeking Women in LURN,” Urogynecology 30, no. 2 (2024): 123–131, 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albers‐Heitner C. P., Lagro‐Janssen A. L. M., Joore M. A., et al., “Effectiveness of Involving a Nurse Specialist for Patients With Urinary Incontinence in Primary Care: Results of a Pragmatic Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial,” International Journal of Clinical Practice 65, no. 6 (2011): 705–712, 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macaulay A. J., Stern R. S., Holmes D. M., and Stanton S. L., “Micturition and the Mind: Psychological Factors in the Aetiology and Treatment of Urinary Symptoms in Women,” BMJ 294, no. 6571 (1987): 540–543, 10.1136/bmj.294.6571.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benzo R. M., Moreno P. I., Noriega‐Esquives B., Otto A. K., and Penedo F. J., “Who Benefits from an Ehealth‐Based Stress Management Intervention in Advanced Prostate Cancer? Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial,” Psycho‐Oncology 31, no. 12 (2022): 2063–2073, 10.1002/pon.6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Knippenberg V., Leue C., Vrijens D., and van Koeveringe G., “Multidisciplinary Treatment for Functional Urological Disorders With Psychosomatic Comorbidity in a Tertiary Pelvic Care Center—A Retrospective Cohort Study,” Neurourology and Urodynamics 41, no. 4 (2022): 1012–1024, 10.1002/nau.24917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Funada S., Watanabe N., Goto T., et al., “Clinical Feasibility and Acceptability of Adding Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Pharmacotherapy for Drug‐Resistant Overactive Bladder in Women: A Single‐Arm Pilot Study,” LUTS: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms 13, no. 1 (2021): 69–78, 10.1111/luts.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steers W. D., Herschorn S., Kreder K. J., et al., “Duloxetine Compared With Placebo for Treating Women With Symptoms of Overactive Bladder,” BJU International 100, no. 2 (2007): 337–345, 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Detke M. J., Wiltse C. G., Mallinckrodt C. H., McNamara R. K., Demitrack M. A., and Bitter I., “Duloxetine in the Acute and Long‐Term Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: A Placebo‐ and Paroxetine‐Controlled Trial,” European Neuropsychopharmacology 14, no. 6 (2004): 457–470, 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li X., Zhu L., Zhou C., et al., “Efficacy and Tolerability of Short‐Term Duloxetine Treatment in Adults With Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Meta‐Analysis,” PLoS One 13, no. 3 (2018): e0194501, 10.1371/journal.pone.0194501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Connor E., Henninger M., Perdue L. A., Coppola E. L., Thomas R., and Gaynes B. N., “Screening for Depression, Anxiety, and Suicide Risk in Adults: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S,” Preventive Services Task Force (2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., and Williams J. B. W., “The PHQ‐9,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 16, no. 9 (2001): 606–613, 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El‐Den S., Chen T. F., Gan Y. L., Wong E., and O'Reilly C. L., “The Psychometric Properties of Depression Screening Tools in Primary Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Affective Disorders 225 (2018): 503–522, 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spitzer R. L., Kroenke K., Williams J. B. W., and Löwe B., “A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder,” Archives of Internal Medicine 166, no. 10 (2006): 1092, 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lakkis N. A. and Mahmassani D. M., “Screening Instruments for Depression in Primary Care: A Concise Review for Clinicians,” Postgraduate Medicine 127, no. 1 (2015): 99–106, 10.1080/00325481.2015.992721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Plummer F., Manea L., Trepel D., and McMillan D., “Screening for Anxiety Disorders With the GAD‐7 and GAD‐2: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Metaanalysis,” General Hospital Psychiatry 39 (2016): 24–31, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Whooley M. A., Avins A. L., Miranda J., and Browner W. S., “Case‐Finding Instruments for Depression,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 12, no. 7 (1997): 439–445, 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B., and Löwe B., “An Ultra‐Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ‐4,” Psychosomatics 50, no. 6 (2009): 613–621, 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y., Wu X., Liu G., Feng X., Jiang H., and Zhang X., “Association Between Overactive Bladder and Depression in American Adults: A Cross‐Sectional Study From Nhanes 2005–2018,” Journal of Affective Disorders 356 (2024): 545–553, 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peyronnet B., Mironska E., Chapple C., et al., “A Comprehensive Review of Overactive Bladder Pathophysiology: On the Way to Tailored Treatment,” European Urology 75, no. 6 (2019): 988–1000, 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Batavia J. P., Butler S., Lewis E., et al., “Corticotropin‐Releasing Hormone From the Pontine Micturition Center Plays an Inhibitory Role in Micturition,” The Journal of Neuroscience 41, no. 34 (2021): 7314–7325, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0684-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tarcan T., Selai C., Herve F., et al., “Should We Routinely Assess Psychological Morbidities in Idiopathic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: ICI‐RS 2019?,” Neurourology and Urodynamics 39, no. S3 (2020): S70–S79, 10.1002/nau.24361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Russell A. E., Joinson C., Roberts E., et al., “Childhood Adversity, Pubertal Timing and Self‐Harm: A Longitudinal Cohort Study,” Psychological Medicine 52, no. 16 (2022): 3807–3815, 10.1017/S0033291721000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burrows K., Heron J., Hammerton G., Goncalves Soares A. L., and Joinson C., Adverse Childhood Experiences and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Adolescence: The Mediating Effect of Inflammation.

- 38. Drake M. J., Morris N., Apostolidis A., Rahnama'i M. S., and Marchesi J. R., “The Urinary Microbiome and Its Contribution to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; ICI‐RS 2015,” Neurourology and Urodynamics 36, no. 4 (2017): 850–853, 10.1002/nau.23006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lombardo R., Tema G., Cornu J. N., et al., “The Urothelium, the Urinary Microbioma and Men Luts: A Systematic Review,” Minerva Urologica E Nefrologica 72, no. 6 (2020): 712–722, 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.