Abstract

Next‐generation sequencing has revealed the disruptive reality that advanced/metastatic cancers have complex and individually distinct genomic landscapes, necessitating a rethinking of treatment strategies and clinical trial designs. Indeed, the molecular reclassification of cancer suggests that it is the molecular underpinnings of the disease, rather than the tissue of origin, that mostly drives outcomes. Consequently, oncology clinical trials have evolved from standard phase 1, 2, and 3 tissue‐specific studies; to tissue‐specific, biomarker‐driven trials; to tissue‐agnostic trials untethered from histology (all drug‐centered designs); and, ultimately, to patient‐centered, N‐of‐1 precision medicine studies in which each patient receives a personalized, biomarker‐matched therapy/combination of drugs. Innovative technologies beyond genomics, including those that address transcriptomics, immunomics, proteomics, functional impact, epigenetic changes, and metabolomics, are enabling further refinement and customization of therapy. Decentralized studies have the potential to improve access to trials and precision medicine approaches for underserved minorities. Evaluation of real‐world data, assessment of patient‐reported outcomes, use of registry protocols, interrogation of exceptional responders, and exploitation of synthetic arms have all contributed to personalized therapeutic approaches. With greater than 1 × 1012 potential patterns of genomic alterations and greater than 4.5 million possible three‐drug combinations, the deployment of artificial intelligence/machine learning may be necessary for the optimization of individual therapy and, in the near future, also may permit the discovery of new treatments in real time.

Keywords: cancer, N‐of‐1, personalized medicine, precision medicine, tissue agnostic

INTRODUCTION

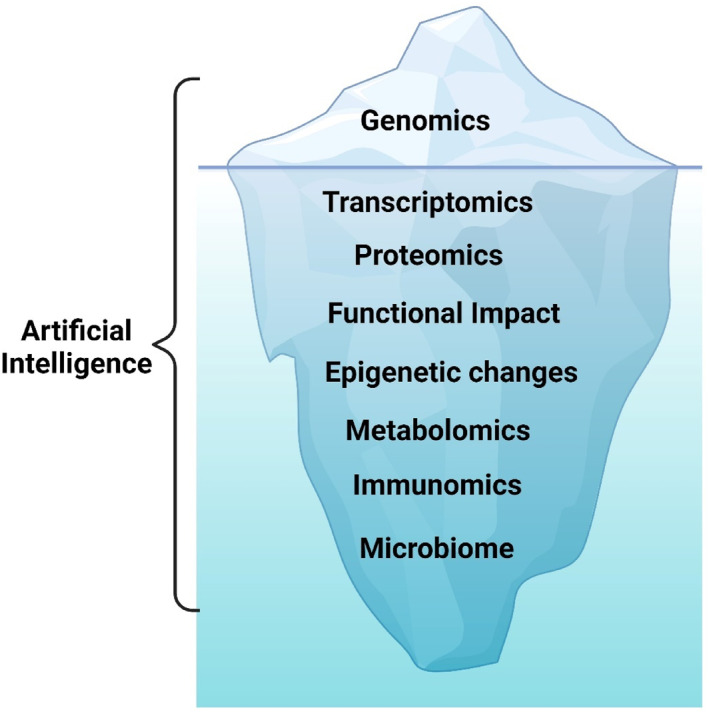

There is a rapidly growing body of knowledge in cancer genomics and a more recent explosion of multiomic and functional technologies (Figure 1) that have revealed a complicated and heterogeneous molecular landscape in advanced and metastatic cancers. 1 Biologic heterogeneity exists between histologies, within the same diagnostic group, and even within individual patients. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Indeed, most advanced malignancies have a complex portfolio of molecular alterations. 3 Immune‐targeted and gene‐targeted therapies based on molecular biomarkers are emerging as critical modalities for treating cancer, although a strategy using monotherapy that addresses a single mutation is not likely curative for people with metastatic disease. Therefore, personalized combination therapies are needed to more effectively treat advanced and metastatic cancers. Moreover, moving biomarker‐driven therapy to the earliest stages of cancer treatment, when the disease is less complex at the molecular level, needs to be more widely explored.

FIGURE 1.

New era of multiomics. Genomics is the tip of the iceberg. The transcriptome, proteomics, functional impact, epigenetic changes, metabolomics, immunomics, and the microbiome are all tools that will be integrated into future precision medicine therapeutic approaches. Artificial intelligence can help guide interpretation and integration of multi‐omics data to optimize therapy. Created with biorender.com.

Traditional clinical trials in the oncology drug‐development process evaluated promising therapeutics in sequential phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical studies. However, this canonical trial sequence can take years to complete and may not be best suited to the molecular era, given the potential for very high response rates with remarkable durability using molecularly based therapies. Indeed, innovative clinical trials designs as well as novel end points are needed to facilitate the rapid development of novel therapies. Determining the genomic landscape of cancer tissue, as well as blood circulating tumor DNA/cell‐free DNA, and circulating tumor cells, has provided the initial basis for personalized medicine approaches, but novel technologies are being explored to further refine therapeutic choices and better understand mechanisms of resistance.

Clinical trials have undergone considerable evolution in recent years, from traditional drug‐centered, tissue‐specific trials; to tissue‐specific, genomically driven trials; to tumor‐agnostic, biomarker‐based trials; and, most recently, to patient‐centered, N‐of‐1 combination therapy trials, in which each patient receives a unique therapy based on their tumor landscape. In the latter types of trials, the robustness of the algorithm defining the match between tumors and drugs and its impact on outcome are evaluated, rather than the impact of any one drug or combination of drugs on a specific cancer type defined by its organ of origin (or, more recently, by its underlying genomic aberration). 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Determining safe, personalized doses is also critical in the era of individualized, novel combination therapy. 12

In the current review, we explore clinical trial designs and technologies that are enabling the development of molecularly targeted therapies and the advancement in precision medicine, patient‐centered approaches (Table 1). 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 We also delve into crucial issues, such as addressing disparities and underserved populations, and we provide a patient's unique and moving perspective on novel precision medicine clinical trial approaches.

TABLE 1.

Examples of precision medicine clinical trials with reported results.

| Reference(s) | Trial name | Institute | Type of trial | Type of cancer | Total no. screened | Percentage of patients matched | Type of biomarker | Outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Von Hoff 2010 13 | Bisgrove (NCT00530192) | US (nine sites) | Prospective navigation | Metastatic refractory cancer | 106 | 62.0 | IHC, FISH, microarray | 27% of matched patients had a PFS ratio ≥1.3 (p = .007) | |

| Kim 2011 14 | BATTLE (NCT00409968, NCT00410059, NCT00410189, NCT00411632, NCT00411671) | MD Anderson | Prospective, adaptive randomized | Lung cancer | 341 | NA | PCR‐based genomic, IHC, FISH | 46% 8‐week DCR | Randomized assignments to therapy (adaptive and nonadaptive) |

| Tsimberidou 2012 6 | MD Anderson Personalized Cancer Therapy Initiative (IMPACT, first cohort; NCT00851032) | MD Anderson | Registry style, navigational | Advanced cancer | 1283 | 16 | PCR‐based | Response rate, 27% in matched vs. 5% unmatched (p < .05); longer TTF (p < .001), OS (p < .001), and PFS (p = .017) in matched group | |

| Esserman 2012 15 | I‐SPY 1 (NCT01042379) | US sites (multiple) | Prospective, neoadjuvant | Neoadjuvant treatment for breast cancer | 237 | NA | IHC | pCR differs by receptor subset | Aim was to develop biomarkers of response to conventional therapy |

| Kris 2014 16 | Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium Protocol (NCT01014286) | United States (14 sites) | Prospective | Lung adenocarcinoma | 1537 | 18 | Multiplex genotyping | Improved survival with matched therapy (p = .006) | |

| Jameson 2014 17 | NA | US sites | Prospective | Breast cancer | 28 | 89 | RRPA, cDNA MA, IHC, FISH | Time to progression with multiomic‐based treatment improved in 44% | |

| Tsimberidou 2014 18 | MD Anderson Personalized Cancer Therapy Initiative validation (IMPACT, second cohort) | MD Anderson | Registry style, navigational | Advanced cancers | 1542 | 9 | PCR‐based | Higher response rate (p < .0001), PFS (p = .001), OS (p = .04) in matched group | |

| Andre 2014 19 | SAFIR01/UNICANCER (NCT01414933) | Gustave Roussey (18 French sites) | Prospective | Metastatic breast cancer | 423 | 13 | aCGH/Sanger sequencing | 9% response, 21% SD >16 weeks (matched group) | |

| Le Tourneau 2015 20 | SHIVA (NCT01771458) | Institut Curie (eight French sites) | Prospective, randomized | Refractory cancer | 741 | 13 | NGS | PFS not improved with matched therapy (p = .41) | ∼80% of patients received single‐agent hormone modulators or everolimus |

| Sohal 2015 21 | Cleveland Clinic Study | Cleveland Clinic | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 250 | 10 | NGS | NA | Outcomes not provided |

| Schwaederle 2016 22 | PREDICT (NCT02478931) | UCSD | Registry‐type | Advanced cancers | 347 | 25 | NGS | Higher rates of SD ≥6 months/PR/CR (p ≤ .02), PFS (p = .039), OS (p = .04) in matched group | |

| Wheler 2016 23 | Genomic Profiling Assay in Phase 1 (MD Anderson Personalized Cancer Therapy Initiative; NCT02437617) | MD Anderson | Prospective, navigational | Advanced cancers | 500 | 24 | CGP/NGS | Higher rates of SD ≥6 months/PR/CR (p = .024), TTF (p = .0003), OS (p = .05) with better matching score | |

| Stockley 2016 24 | IMPACT/COMPACT (NCT01505400) | Princess Margaret Cancer Center(Canadian centers) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 1893 | 5 | NGS | Higher overall response rate with matched therapy (p < .026) | |

| Aisner 2016 25 | LCMC2 | Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (16 sites) | Prospective | Lung adenocarcinoma | 980 | 13 | NGS | Improved survival with matched therapy (p = .039) | |

| Papadimitrakopoulou 2016 26 | BATTLE‐2 (NCT01248247) | MD Anderson, Yale | Prospective | Nonsmall cell lung cancer | 334 | NA | FISH | KRAS‐positive with longer PFS without erlotinib (p = .04); KRAS wild‐type tumors with better OS on erlotinib (p = .03) | |

| Park 2016 | I‐SPY 2 (NCT01042379) | Quantum‐Leap Healthcare (US sites) | Prospective randomized | Neoadjuvant breast cancer | NA | NA | IHC, MammaPrint | Improved pCR rates with drug addition: HER2‐positive, HR‐negative; neratinib with standard therapy, 56% (N = 115 treated) vs. 33% (N = 78 treated) | Results are one arm of a multiple arm study |

| Massard 2017 28 | MOSCATO (NCT01566019) | Gustave Roussey | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 1035 | 19 | aCGH, NGS, RNAseq | 33% on matched therapy had improved outcome vs. previous baseline (p = .004) | |

| Tsimberidou 2017 29 | MD Anderson Personalized Cancer Therapy Initiative (IMPACT, third cohort; NCT00851032) | MD Anderson | Registry‐style, navigational | Advanced cancers | 1436 | 27 | PCR‐based | Matched therapy with higher response rates (p = .0099), longer failure‐free survival (p = .0015), longer OS (p = .04) | |

| Kim 2017 | NEXT (NCT02141152) | Samsung Medical Center, Korea | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 654 | 9 | IHC/DNA sequencing | Improved clinical trial enrollment | Outcomes of matched therapy not provided |

| Hainsworth 2018 31 | MyPathway (NCT02091141) | Genentech (US sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 251 (total screened unknown) | 92 | Genomic testing | 23% response rate; 38% HER2 group, 43% BRAF group | No comparison between matched therapy and prior therapy provided; study has multiple other cohorts |

| Slosberg 2018 | Signature (NCT01833169, NCT01831726, NCT1885195, NCT01981187, NCT02002689, NCT02160041, NCT02186821, NCT02187783) | Novartis (multiple sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 1568 | 38 | Variable | 17% clinical benefit rate (SD/PR/CR) | No unmatched comparator |

| Aisner 2019 33 | LCMC2 | Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (16 sites) | Prospective | Lung | 1367 | 12 | NGS, minimum of 14 genes | Improved survival with matched therapy (p < .001) | |

| Sicklick 2019 9 | I‐PREDICT (previously treated cohort; NCT02534675) | UCSD, Avera Cancer Institute (South Dakota | Prospective navigational | Advanced cancers | 149 | 49 | CGP | Higher matching score led to longer PFS (p = .0004), and OS (0.038) | |

| Rodon 2019 11 | WINTHER (NCT01856296) | WIN Consortium for Personalized Cancer Therapy; international (five countries: Spain, United States, Israel, France, Canada) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 303 | 35 | NGS/transcriptomics | High matching scores correlated with longer PFS (p = .005) and OS (p = .03) | |

| Tredan 2019 34 | ProfiLER (NCT01774409) | Centre Leon Berard (four French sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 2579 | 6 | NGS/aCGH | 13% partial responses with molecular‐based recommended therapies | No comparison with unmatched therapies provided |

| Tuxen 2019 35 | CoPPO (NCT02290522) | University of Copenhagen | Prospective | Advanced solid tumors | 591 | 17 | CGP | ORR, 15%; median PFS, 12 weeks (matched patients) | No comparison provided with unmatched |

| Lee 2019 36 | VIKTORY (NCT02299648) | Republic of Korea | Prospective | Gastric | 772 | 14 | NGS, IHC, PD‐L1, MMR, and EBV status | Improved PFS and OS with matched vs. unmatched therapy (p < .0001) | |

| Turner 2020 37 | PlasmaMATCH (NCT03182634) | United Kingdom | Prospective | Breast | 1051 | 12 | ctDNA | Cohorts B (25%; HER2‐positive) and C (22%; AKT1/HR‐positive) met or exceeded target response | ctDNA testing used to match patients to targeted therapies; no comparison with unmatched provided |

| Burd 2020 38 | Beat AML (NCT03013998) | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society | Prospective | AML | 487 | 46 | Cytogenetic/NGS | OS significantly improved (12.8 vs. 3.9 months) in matched substudies | Matched to a substudy based on molecular profile/cytogenetic results |

| Redman 2020 39 | Lung‐MAP (NCT02154490) | NCI (US sites) | Prospective | Advanced squamous cell lung cancer | 1864 | 12 | NGS | Targeted therapy, 7% response rate vs. 5% docetaxel; 17% for anti‐PD‐L1; median OS, 5.9 months (targeted) vs. 7.7 months (docetaxel) vs. 10.8 months anti–PD‐L1 | Data combined from substudies; low activity in investigated targeted therapies (several were non‐FDA–approved therapies) |

| Flaherty 2020, 40 Zhou 2024 41 | NCI‐MATCH (NCT02465060) | NCI (US sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | NA | NA | NGS | ORR: 38% dabrafenib/trametinib BRAF V600E; 29% capivasertib for AKT1 | Analysis of 10 subprotocols (n = 435 matched patients) |

| Sicklick 2021 10 | I‐PREDICT (treatment naive cohort; NCT02534675) | UCSD, Avera Cancer Institute (South Dakota) | Prospective navigational | First‐line therapy in advanced cancers | 145 | 37 | CGP | Matching score correlated linearly with PFS (p = .01); high matching score had improved DCR (p = .048), PFS (p = .08), and OS (p = .02) | |

| Chen 2021 42 | MPACT (NCT01827384) | NCI (US sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancer | 198 | 32 | NGS | PFS improved for everolimus (p = .045) and trametinib (p = .01) but not for adavosertib with carboplatin (p = .32) | |

| Catenacci 2021 43 | Pangea (NCT02213289) | University of Chicago | Prospective | Gastroesophageal cancers | 80 | 74 | Tumor biomarker profiling/cell‐free DNA | First‐line response rate of 74%, DCR 99%, and PFS 8.2 months were superior to historical controls | Chemotherapy with matched antibodies; no comparison with unmatched provided |

| Hoes 2022 | DRUP (NCT02925234) | Netherlands | Prospective | Advanced cancers | 1145 | 44 | NGS | 33% CBR for rare and nonrare cancers | Comparisons between matched therapy for rare and nonrare tumors |

| Yang 2023, 45 Meric‐Bernstam 2023, 46 Gupta 2022 47 | TAPUR (NCT02693535) | ASCO (US sites) | Prospective | Advanced cancers | Genomic analysis or IHC |

Olaparib: 58% ORR (mCRPC) for BRCA1/2 Cobimetinib/vemurafenib: 68% DCR for BRAF V600E Trastuzumab/pertuzumab: 58% DCR (colorectal) for ERBB2 amp |

Study is ongoing; patients matched to cohorts based on matched therapy; multiple other cohorts with results; no comparison with unmatched | ||

| Eckstein 2022, 48 Lee 2023 49 | Pediatric MATCH (NCT03155620) | NCI‐COG (US sites) | Prospective | Pediatric advanced cancers | NA | NA | CLIA‐certified molecular testing | Arm B, erdafinibib with 54% (PR/SD); arm E, selumetinib with no objective responses | No unmatched comparison; nationwide histology‐agnostic molecular screening, which matched patients into multiple cohorts; study is ongoing |

Abbreviations: aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CBR, clinical benefit rate; cDNA MA, complementary DNA microarray; CGP, comprehensive genomic profiling; CLIA, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; COG, Children's Oncology Group; CR, complete response; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; DCR, disease control rate; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; mCRPC, metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer; MD Anderson, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; MMR, mismatch repair; NA, not available; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NGS, next‐generation sequencing; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; pCR, pathologic complete response; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PFS, progression‐free survival PR, partial response; RNAseq, RNA sequencing; RRPA, reverse‐phase protein array; SD, stable disease; TTF, time to treatment failure; UCSD, University of California San Diego; WIN, Worldwide Innovative Networking in Personalized Cancer Medicine.

MOLECULAR TECHNOLOGY FOR PRECISION CANCER MEDICINE

Genomics has been the key to precision medicine studies. The sequencing of the human genome, its dramatic drop in cost, and the availability of clinical‐grade next‐generation sequencing (NGS) have transformed oncology. Although genomics is a cornerstone for precision oncology, it is only the tip of the iceberg (Figure 1). Additional methodologies are available and may provide further refinement of precision medicine approaches. Transcriptomic, proteomic, functional impact, epigenomic, metabolomic, immunomic, and microbiome technologies are already exploitable or under development with a goal of providing a full multiomic approach to precision medicine therapies and clinical trials (Table 2). Molecular testing can be done on tumor tissue or on liquid (usually blood‐based) biopsies or from other body fluids as well. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning can help integrate the large amount of data generated by these technologies to optimize therapy for precision medicine approaches.

TABLE 2.

Technologies enabling precision medicine approaches.

| Technology | Description |

|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA of tumor obtained by next‐generation sequencing of tumor or liquid biopsy (circulating tumor DNA), cell‐free DNA, circulating tumor cells |

| Transcriptomics | RNA transcripts (obtained from RNA sequencing of tumor tissue) |

| Proteomics | Protein expression in tumors (obtained by immunohistochemistry) |

| Function impact | Studying therapeutic effects on organoids (multicellular clusters of tumor cells) |

| Epigenomics | Modification of DNA or histones without alterations in DNA |

| Metabolomics | Metabolic products of human body |

| Immunomics | Host–tumor interaction and immune microenvironment |

| Microbiome | Diverse microorganism communities with the human body and on body surfaces |

| Artificial intelligence | Computerized artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches |

Genomics

Genomics has been foundational for precision cancer medicine. NGS is available from many Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments‐certified laboratories in the United States. It has allowed for accurate, reproducible, and standardized methods, which provide information critical to determine which patients will benefit the most from experimental and approved molecularly targeted therapies. Most NGS panels probe for several hundred genes commonly seen in advanced and metastatic cancer and are used on tumor tissue samples. Whole‐genome sequencing is becoming more available. Although most genomic sequencing involves tissue, important information to guide precision medicine therapies can be obtained from blood‐derived circulating tumor DNA, cell‐free DNA, and circulating tumor cells. 50

Transcriptomics

Transcriptomics relates to measuring RNA transcripts and understanding their function. Genomic alterations may reflect unique changes in gene expression, and this technology can provide key information on gene expression patterns. The transcriptome may also be critical to accurately identifying gene fusions, which are critical cancer drivers. Microarrays and RNA sequencing are generally used to quantify RNA transcription; however, degradation and fragmentation of RNA in stored tissue, along with the complexity of the analysis, must be taken into account for this technology to be reliable. 51 , 52 , 53

Proteomics

Proteomics involves immunohistochemistry (IHC) and other protein assessment technologies to quantify protein‐level expression from tumors. Emerging technologies include high‐throughput proteomics approaches, such as mass spectrometry, protein pathway arrays, next‐generation tissue microarrays, single‐cell proteomics, single‐molecule proteomics, and others. 54 There is a weaker correlation between first‐generation proteomic markers (mostly IHC) versus genomic markers with regard to responses or resistance to therapy, perhaps because of tissue heterogeneity at the protein level. 51 , 55 , 56

Functional impact

In vitro systems have the potential to predict cancer therapeutic effectiveness. Traditional two‐dimensional cell cultures often were limited by the genetic changes that occur with long‐term culture. Organoids are multicellular clusters that can proliferate and self‐renew while maintaining physiologic structure, mutation patterns, and function of the tissue from which they were derived. 57 , 58 They have been developed for multiple cancer types and can be used to screen large numbers of cancer therapeutics to determine optimal therapy for an individual patient. The challenges to the implementation of functional assays remain assay success rates, turnaround times, the need for standardized conditions, and the definition of in vitro responders. 59

Epigenomics

Epigenomics is the study of modification to the DNA or histones without altering the DNA sequence itself. Modifications such as DNA methylation and histone modification can alter gene expression. 60 Modulating the epigenome has long been considered a potential opportunity for therapeutic intervention in numerous disease areas with several approved therapies marketed, primarily for cancer. Despite the overall promise of early approaches for drugging the epigenome, studies of these drugs have been plagued by poor pharmacokinetic and safety/tolerability profiles in large part because of off‐target effects and a lack of specificity. 61

Metabolomics

Metabolomics is the study of metabolic products of the human body. Metabolites of therapeutics may also have salutary or toxic effects. Cancer cells may have altered metabolism and produce products that can aid in growth or alter therapeutic efficacy. Metabolomic technology can be used to identify treatment options or predict response to oncology therapies. 62

Immunomics

Immunomics aims to understand the host–tumor interaction and to profile the tumor immune microenvironment. Novel bioinformatic tools have been used in conjunction with genomics and transcriptomic data to evaluate such immune entities as neoantigens and T‐cell and B‐cell clonotype expansion. This information can help establish biomarkers for immune checkpoint efficacy (e.g., tumor mutational burden) and may help develop novel immune‐mediated therapies as well as match patients with the best type of immune modulators for their malignancy using a precision immunotherapy paradigm. 63

Microbiome

The microbiome consists of diverse microorganism communities in the human body. It includes viruses, bacteria, fungi, and eukaryotes that colonize human body surfaces. 64 It can play a role in carcinogenesis, activating aberrant signaling pathways, and eliciting immunosuppressive effects. Gut microorganisms can affect anticancer treatment efficacy for both chemotherapy and immunotherapy. 65 Modulation of the microbiome may improve immunotherapy efficacy. 66 , 67 Thus an understanding of each individual microbiome can help with further personalization of therapy.

Artificial intelligence

With the vast amount of data generated by multiomic approaches, it can be difficult to integrate all of the information to optimize anticancer therapy for each individual. AI and machine learning can be exploited to analyze multimodal‐omics data and optimize clinical integration. 68 , 69 , 70

Therefore, although our understanding of cancer remains incomplete, additional technologies beyond genomics may provide further insight into cancer biology. A better understanding of the drivers of tumor growth and which molecular alterations should be prioritized as therapeutic targets may be revealed by such methodologies as transcriptomics, proteomics, functional impact, epigenomics, metabolomics, immunomics, and the microbiome. Future precision medicine oncology clinical trials and studies should combine these methodologies with genomic testing to better evaluate their role in optimizing cancer therapy.

DRUG‐CENTERED TRIALS

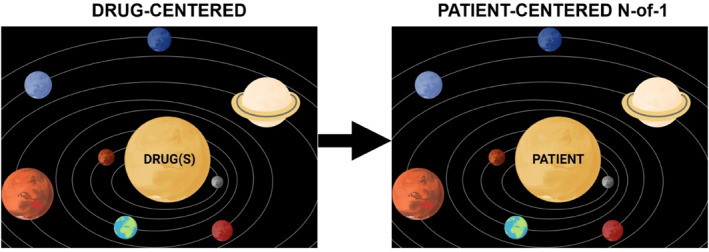

Until the recent advent of N‐of‐1 patient‐centered trials in oncology, all trials were drug centered, meaning that the trial was centered on the drugs, and patients were found to fit the drugs. These trials include traditional phase 1, 2, and 3 trials and trials that are for specific tissue types of cancers (e.g., lung or breast or colon cancer, etc.) or genomic subsets of those cancers (e.g., lung cancers with ALK fusions) and the most recent basket tumor‐agnostic trials based on a genomic alteration (e.g., an NTRK fusion basket trial). 7 , 8 More recently, patient centered/N‐of‐1 oncology clinical trials have been conducted. 9 , 10 , 11 These trials place the patient at the center, and drugs are found for patients rather than patients found for drugs (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Transition from drug‐centered therapeutic strategies (the drugs are the center of the universe, and patients are found to fit the drugs based on their diagnostic category; hence, all patients within a diagnostic category receive the same drugs, and the efficacy of the drug regimen in that subgroup of patients is evaluated) to a patient‐centered (N‐of‐1) focus (patients are the center of the universe, and drugs are found to fit the patient's tumor's unique portfolio of molecular aberrations; hence, every patient receives a personalized set of drugs) for precision medicine trials. In the patient‐centered (N‐of‐1) trials, the efficacy of the algorithm that matches patients to drugs, rather than the efficacy of individual drug regimens, is evaluated. Created in biorender.com.

Traditional drug‐centered clinical trial design

Traditional oncology clinical trials evaluate the safety, efficacy, and benefit of novel therapeutics in three phases—phase 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Clinical trial designs.

| Trial | Description |

|---|---|

| Drug‐centric trials (Patients are given the same set of drugs per the trial) | |

| Traditional trial designs | |

| Phase 1 | First in human to determine the maximum tolerable dose or the recommended phase 2 dose; evaluates safety, pharmacokinetics, and early activity |

| Phase 2 | Larger study (often 25–40 patients) to establish efficacy signal |

| Phase 3 | Randomized controlled study to evaluate efficacy of a therapy compared with standard of care |

| Innovative trial designs | |

| Broad phase 2 | Evaluate efficacy in a wide variety of solid tumors and/or hematologic malignancies within a single trial |

| Bayesian adaptive trial | Adaptive trial design that can be modified after interim analysis including in small numbers of patients |

| Umbrella trial | Enrolls patients with a common tumor type, tests multiple molecular markers, and then assigns patients to an arm of the study based on the molecular markers |

| Octopus trial | Multiple arms that test different drugs or drug combinations in a single trial |

| Platform trial | Includes multiple histologies and genomic or other biomarkers and is based on a single technological platform |

| Master protocol | Overarching protocol designed to answer multiple questions; can include one or more interventions in multiple diseases or a single disease, with multiple interventions; may include umbrella, basket, and/or platform trials |

| Telescope trial (seamless) | Combine all three phases of trials (phase 1, 2, and 3) into one sequential trial |

| Basket trial | Evaluate groups of patients who are pooled based on biomarker characteristics rather than tumor of origin |

| Patient‐centric trials (different drugs are chosen for each patient) | |

| N‐of‐1 trial | Provides a unique therapy to each patient based on the molecular, immune, and other biologic characteristics of their tumor; treatment regimen is specific to each patient’s tumor landscape |

Phase 1 trials

Phase 1 trials provide first‐in‐human assessments of a therapy. These trials are designed to evaluate safety and side effects along with early activity signals. The trial may investigate experimental drugs after animal studies are complete or may be the first trial to combine approved drugs. These trials determine the maximum tolerable dose (MTD) and recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D). A traditional 3 + 3 study design enrolls three patients in a given dose cohort to assess dose‐limiting toxicity, generally defined as a grade ≥3, clinically relevant toxicity in the first cycle of therapy. In an expanded cohort of six patients, the MTD is achieved at the highest dose level, in which one or fewer patients experience dose‐limiting toxitiess. 71 If there are low‐grade toxicities that are tolerable over the usual 4‐week MTD evaluation period but are intolerable over a longer time, an RP2D lower than the MTD may be reported from the trial. New approaches for phase 1 trials use accelerated designs, but these designs have sometimes proved disadvantageous because, with fewer patients enrolled, there is less experience with the spectrum of drug activity and toxicity. In general, phase 1 studies enroll a small number of participants and recruit patients with advanced cancers. However, expansions of phase 1 studies to larger cohorts have now become common and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals have occurred after phase 1 studies. 72

Phase 2 trials

Phase 2 trials take the MTD and/or the RP2D from the phase 1 study to evaluate efficacy in a larger cohort of patients generally with a specific tumor type, although, more recently, this may be a biomarker‐selected subgroup of a specific tumor type or even a tumor‐agnostic group of patients with a common biomarker. Phase 2 studies often provide evidence that an efficacy signal exists and warrants evaluation in a larger phase 3 study.

Phase 3 trials (randomized)

Phase 3 randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of a therapy and obtaining regulatory approvals for novel therapies. 73 In general, these studies compare novel therapies versus standard of care to confirm efficacy, safety, and advantages over existing therapies in a specific tumor type. Double‐blinded randomized controlled studies blind both the patient and the investigator to the therapy and minimize confounding factors. The studies can be designed either as superiority trials (i.e., novel therapy is better than the standard of care) or noninferiority trials (i.e., novel therapy is no worse than the standard of care). All parameters in the trial are locked down at their inception. Randomized controlled trials are by far the best way to eliminate confounders. However, the downsides of these trials include the difficulty in accruing rare or ultrarare cancers; their expense and long timeline, during which new discoveries may be made but cannot be incorporated; and the problem that, if the treatment arm is particularly active beyond a certain threshold, the control arm may be undesirable or even unethical.

Innovative, drug‐centered trial designs beyond traditional phase 1, 2, and 3

Innovative, drug‐centered trial designs include broad phase 2, Bayesian adaptive, umbrella, octopus, platform, and telescope trials, along with master protocols (Table 3).

Broad phase 2 studies

During the 1970s and 1980s, when a novel compound emerged from animal and phase 1 studies, it was quite common to initiate a broad phase 2 trial of that agent. In broad phase 2 studies, patients with a wide variety of both solid tumor and hematologic malignancies were treated. 74 One notable example of such a study was a trial of the anthracycline doxorubicin conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group. 75 A single trial of 472 patients defined the encouraging activity of doxorubicin for patients with advanced breast, prostate, bladder, and uterine cancers, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and small cell lung cancer; established the standard intermittent dosing schedule for the drug; and characterized the major toxicities of the agent (on the heart, mucosa, and bone marrow). The study was submitted for publication within 24 months of trial initiation. Despite the efficiency of the broad phase 2 trials, the cancer clinical trials field shifted in the early 1980s. It became standard dogma that the biologic activity of cancer therapeutics was substantively controlled by histologic context; therefore, investigators concluded that phase 2 trials should be conducted in a tumor‐specific manner. The demise of the broad phase 2 trial led to a growth industry of single‐drug/single‐disease trials. Phase 2 trials conformed to specific two‐stage designs. Looking back, these tumor‐specific phase 2 trials have proved far less efficient than the broad phase 2 trials.

Bayesian adaptive trials

The greatest advantage of phase 3 randomized controlled trials is their extreme rigor, but a side effect of this advantage is inflexibility. Adaptive trial designs allow for modification of the trial after interim data analysis. The continuous learning that is possible in this approach (termed Bayesian) enables investigators to stop the trial early, assign patients to therapies that are performing better, and add or drop therapy arms. Adaptive trials also provide randomization as an option, if indicated by preliminary analysis, and decisions on efficacy requiring a very small number of patients. This is also known as Bayesian randomization. 76 , 77 The disadvantage of this strategy is that tolerability and drug toxicities may not be fully explored. Also, given the small number of patients enrolled, patients with less common biomarkers may not be included in the trial.

Umbrella trial

Umbrella trials enroll patients with a common tumor type, test multiple molecular markers, and then assign patients to an arm of the study based on the molecular markers. Each arm represents a potentially effective treatment for the molecular marker. This design can allow for modification over time as new targets and therapies are discovered. Certain arms can be opened or closed rapidly, depending on the success of the target and therapeutic. 76 , 78

An example of an umbrella trial is Lung‐MAP (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02154490). 79 The Lung Master Protocol (Lung‐MAP; S1400) is a clinical trial that was designed to advance the efficient development of targeted therapies for squamous cell cancer of the lung. The Cancer Genome Atlas project and similar studies had discerned a significant number of somatic gene abnormalities in this type of lung cancer, some of which are potentially druggable by investigational agents. However, the frequency of these aberrations is low (5%–20%), making recruitment and study conduct challenging in the conventional clinical trial setting. Hence, Lung‐MAP was born as a clinical trial umbrella strategy; Lung‐MAP uses a biomarker‐driven, phase 2/3, multi‐substudy master protocol and a common NGS platform to identify actionable molecular abnormalities, followed by randomization to the relevant targeted therapy versus standard of care.

Octopus trial

The octopus study design denotes multiple arms that test different drugs or drug combinations in a single trial. When performed in the phase 1 setting, these studies were considered complete phase 1 trials (a terminology coined by Dan Von Hoff). 76 , 78 , 80

Platform trial

A traditional platform trial includes multiple histologies and genomic or other biomarkers and is based on a single technological platform (i.e., NGS) to interrogate the tumor. There can be a fixed number of patients in each arm. All treatments are compared with the same control. Interim monitoring for success and futility at equally spaced intervals has been added to some platform designs; and, if a treatment is dropped because of futility, the accrual on the remaining active arms is greater.

An open platform uses an adaptive design in which treatments can be dropped or added during the course of the trial. New treatments can be added to replace ineffective treatments during the trial. These trials can find effective treatments more efficiently and with fewer resources than investigating one treatment per trial. 76 , 78

Master protocol

A master protocol is an overarching protocol designed to answer multiple questions. Master protocols can include one or more interventions in multiple diseases or a single disease, with multiple interventions. Master protocols may include umbrella, basket, and/or platform trials. 76 , 78 A master protocol uses either a single, multiplex diagnostic assay to assign individuals to different candidate drugs or arms of the trial within the same trial or network of trials; or it may use multiple, discrete biomarker assays alone or in combination. Master protocols offer more options for patients and can also make screening and recruitment more efficient.

One example of a master protocol is the DART study (Dual Anti–CTLA‐4 and Anti–PD‐1 blockade in Rare Tumors) sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG1609; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02834013). This trial included 53 cohorts: 52 of these cohorts reflected phase 2 studies for different rare or ultrarare tumor types in which each patient received nivolumab and ipilimumab; one cohort was for programed death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1)–amplified tumors (hence based on a molecular biomarker), and patients were treated with nivolumab monotherapy. Multiple cohorts have had positive read outs, with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines modified based on two cohorts (angiosarcoma and high‐grade neuroendocrine) to date. 81 , 82 Data are analyzed for each individual cohort. In addition, data also are pooled across cohorts for analyses of overall outcomes as well as for extensive molecular correlates. 83 In many ways, the DART master protocol is similar to the broad phase 2 studies described above and was routinely used in drug development during the 1970s and 1980s. 74

Telescope (seamless design)

Telescoped clinical trials combine all three phases of trials—phase 1, 2, and 3—and thereby seamlessly move from preliminary to confirmatory data in one trial. The participants enrolled in the learning and confirmatory stages are all included in the final analysis but can also be analyzed separately. This design can reduce costs and shorten the drug‐development timeline. Promising agents are moved through the study, whereas agents that fail early are dropped. These studies are complex to design because the later phases are designed before phase 1 and 2 portions have occurred. During the time it takes to complete the study, changes in practice may occur because of approvals of other drugs, which can make the interpretation of results difficult. 76 Conversely, avoiding the long activation timelines for separate phase 1, 2, and 3 trials by incorporating all phases into a single trial is an important advantage.

Innovative trial designs facilitating precision medicine biomarker‐based approaches

Molecularly targeted therapies and precision medicine approaches require moving beyond standard phase 1, 2, and 3 trial designs. For instance, traditional phase 2 and 3 oncology clinical trials establish a particular therapeutic for a specific tumor type, whereas newer trial designs may base eligibility on biomarkers and may offer a treatment for a single gene alteration or a complex portfolio of alterations across multiple cancer types.

Basket trials

Basket trials address various cancers based on genomic characteristics (e.g., NTRK fusions) rather than the tumor of origin. Patients are pooled independent of cancer type. These trials assume that response to targeted therapy can be evaluated independently from cancer type; therefore, these studies evaluate multiple cancer types within the same study. Basket studies can have multiple arms that can open and close quickly, depending on success of the therapy, and simultaneously can test many potentially active therapies. 7 , 8 , 31 , 76 , 78 Examples of multiarm basket studies include the MyPathway study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02091141), NCI‐Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI‐MATCH; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02465060) and the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02693535). 31 , 84 , 85 Basket trials have now led to multiple tissue‐agnostic FDA approvals (Table 4) 86 , 87 , 88 and are the basis for the initial reclassification of cancer, in which tumors are classified based on a specific molecular alteration (e.g., NTRK fusions or BRAF mutations) rather than a specific cancer type (e.g., colorectal or lung cancer). Because many driver alterations occur in only a small subset of patients, finding the group of patients with the biomarker requires screening large numbers of patients. For instance, NTRK fusions occur in only about one in 300 solid tumors. 89 Even so, because molecular alterations drive cancer development, these types of trials often show high response rates, with long duration of response. Therefore, FDA tissue‐agnostic approvals are often based on small numbers of highly selected patients (approximately 30–100 patients; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

US Food and Drug Administration tissue‐agnostic approvals.

| Approval year | Therapeutic | Mechanism | Indication | Approval | Comment/references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Pembrolizumab | PD‐1 inhibitor | MSI‐H or dMMR | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2018 | Larotrectinib | NTRK inhibitor | NTRK fusion | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2019 | Entrectinib | NTRK inhibitor | NTRK fusion | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2020 | Pembrolizumab | PD‐1 inhibitor | TMB‐H (≥10 muts/Mb) | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2020 | Pemigatinib | FGFR inhibitor | FGFR1‐rearranged MLNs | Hematologic approval for MLN | Hematologic approval only; Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2021 | Belzutifan a | HIF inhibitor | VHL germline mutations | RCC, hemangioblastoma, PNET | Partial tissue‐agnostic approval; Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2021 | Dostarlimab | PD‐1 inhibitor | dMMR | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2022 | Dabrafenib/trametinib | BRAF/MEK inhibition | BRAF V600E mutation | All solid tumors (except colorectal) | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2022 | Selpercatinib | RET inhibitor | RET fusion | All solid tumors | Fountzilas 2024 86 |

| 2024 | Trastuzumab deruxtecan‐nxki | HER2‐antibody–drug conjugate | HER2‐positive (IHC HER2 3+) | All solid tumors | FDA 2024 87 |

| 2024 | Repotrectinib | ROS‐1, TRKA, TRKB, TRKC inhibitor | NTRK fusion | All solid tumors | FDA 2024 88 |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; dMMR, mismatch‐repair deficiency; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HIF, hypoxia‐inducible factor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MLN, myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm, MSI‐H, microsatellite instability‐high; muts/Mb, mutations per megabase; PD‐1, programmed death 1; PNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; TMB‐H, tumor mutational burden ≥10 mutations per megabase.

Belzutifan is not generally considered a tissue‐agnostic approval, but we included it here because the approval is biomarker‐based and was for four different types of cancers at the same time.

Patient‐centered trials (N‐of‐1)

The molecular reclassification of cancer has led to several transformative observations. Most importantly, it appears that tumors have multiple molecular alterations that differ from patient to patient both between and within histologies. 90 Therefore, the classic drug‐centered, one‐size‐fits‐all clinical trials are a mismatch for the reality that molecular testing has revealed. That reality suggests that personalized patient‐centered, biomarker‐based approaches to management are necessary (Figure 2).

N‐of‐1 clinical trial design

The N‐of‐1, patient‐centered trial design attempts to provide a unique therapy to each patient based on the molecular, immune, and other biologic characteristics of their tumor. Genomic and immune information is obtained before the start of therapy and is used to select a treatment regimen specific to each patient's inimitable tumor landscape. Each patient on the trial may be on a unique therapy or combination of drugs. The drugs given may be on‐label or off‐label approved drugs, or the patient may be navigated to a secondary clinical trial with an experimental drug/drugs. Patients with identical cancer types may have dramatically different therapies selected because the molecular alterations in their tumors vary. Indeed, most tumors have multiple genomic alterations that differ from patient to patient—akin to malignant snowflakes. 1 Determining efficacy requires assessing the strategy of/algorithm for matching patients to therapeutics rather than the efficacy of an individual treatment for a specific cancer. 51 Several N‐of‐1 trials have been performed, including Investigation of Profile‐Related Evidence Determining Individualized Cancer Therapy (I‐PREDICT; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02534675) and WINTHER (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01856296). These trials demonstrate that higher degrees of matching of drugs with each patient's tumors is correlated with higher response rates and longer progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). 9 , 10 , 11 , 91 Such trials require excellent decision support, such as that provided by molecular tumor boards, and access to a variety of drugs, which may be aided by medication‐acquisition specialists, as well as access to clinical trials, which requires working closely with a clinical trial coordinator/navigator. 92

The N‐of‐1 trials described above should be differentiated from N‐of‐1 crossover trials, which are multiple crossover trials done over time within a single person; these trials can also be performed within a series of individuals and are frequently randomized and can be masked; in these trials, the same patient receives different therapies at different times. 93 Despite the similarity in name, N‐of‐1 crossover trials are completely distinct from N‐of‐1 precision cancer medicine trials; moreover, the former are not well suited to oncology because the patient's tumor may progress quickly during periods with the less active drug.

The (r)evolution of precision cancer medicine trials

There have been many advances in the design of clinical trials for molecularly targeted therapies and precision medicine. Table 1 provides examples of precision medicine clinical trials with results. Before the molecular era, clinical trials after phase 1 had almost universally been tissue‐specific and genomically agnostic; a single cancer type was evaluated regardless of patient‐to‐patient variation in genomic milieu. These traditional trials assessed a treatment regimen in, for instance, patients afflicted with lung cancer or breast cancer or sarcoma. More recently, tissue‐specific, genomically driven trials have explored a single biomarker subset of one cancer type, e.g., patients with EGFR‐mutant lung cancer who received EGFR inhibitors. Biomarker‐based, tissue‐agnostic trials and approvals are newer and increasingly are being deployed, with the goal of obtaining regulatory approval of a drug for all patients whose tumors harbor a specific biomarker if the trial is successful (Table 4). 86 , 87 , 88

Today, with the increasing use of NGS, there is a realization that the same molecular alterations can drive tumor growth for multiple tumor types. 94 , 95 , 96 The first example of a tissue‐agnostic FDA approval was for the anti–programmed death 1 (anti–PD‐1) immunotherapy pembrolizumab for solid tumors with high microsatellite instability (MSI‐H). 97 There are now rapidly increasing numbers of tissue‐agnostic FDA approvals (Table 4). Tumor‐agnostic solid tumor approvals include: pembrolizumab (MSI‐H or MSI‐deficient mismatch repair as well as tumor mutational burden [≥10 mutations per megabase), larotrectinib (NTRK fusion), entrectinib (NTRK fusion), dostarlimab (deficient mismatch repair), dabrafenib/trametinib (BRAF V600E mutation), selpercatinib (RET fusion), trastuzumab deruxtecan‐nxki (HER2‐positive; HER2 with an IHC status of 3+), and repotrectinib (NTRK fusion). Pemigatinib is the only hematologic tissue‐agnostic approval and is approved for FGFR1‐rearranged myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms. A partial tissue‐agnostic approval is for belzutifan (VHL germline mutation in renal cell cancer, central nervous system hemangioblastoma, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors). As the focus of oncology trials and therapies shifts to treating based on molecular profile, drug discovery and approvals will likely shift increasingly to biomarker‐based development. An attractive, but as yet scantily explored, concept is to place chemical design and production under AI/digital control.

Another evolution in cancer clinical trials came on the heels of the realization that advanced cancers are complex, and targeting a single alteration leads to only limited responses; therefore, the exploration of novel combinations is important. Traditionally, such combinations were explored one by one. More recently, they may be explored in a platform study, such as ComboMATCH (Combination Therapy Platform Trial with Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT05564377), which is a combination precision medicine clinical trial conducted by the NCI. The basic raison d'etre for ComboMATCH is that most NCI‐MATCH arms did not meet their clinical end points. This observation has reinforced the concept that suppression of the product of a single driver gene alone is not an adequate approach for advanced malignancies, presumably because cancers often recruit parallel or compensatory pathways to overcome the inhibition of a single node. ComboMATCH has been designed to test specific molecularly targeted combinations aimed at overcoming primary and adaptive resistance pathways. Designing a precision medicine trial using drug combinations rather than single agents presents numerous complexities. In NCI‐MATCH, the evidence threshold for testing a single drug against a single target was relatively straightforward; in ComboMATCH, the number of potential drug combinations is exponentially greater. In ComboMATCH, at least one biomarker will be matched to at least one drug, but each drug in the combination will not necessarily be matched to tumor molecular alterations. Subtrials of ComboMATCH will use drug combinations with known phase 2 dosing or will have run‐in phase 1 safety testing followed by phase 2 evaluation of the combination. Outcomes between combination therapy and single‐agent therapy may be compared in the trial in a randomized fashion. The combinations will either be two targeted drugs or a targeted drug plus a cytotoxic chemotherapy agent or, potentially, other combinations. Some trials will be tissue‐agnostic, whereas others will enroll for specific cancer types. 98

Importantly, if each cancer is distinct and molecularly complex, as has been demonstrated by multiple investigations, and the average advanced tumor has five molecular alterations (with approximately 700 cancer‐causing genes), there are greater than 1 × 1012 (more than 1 trillion) patterns. Moreover, layered on top of the genomic complexity, is the finding that, if there are approximately 300 cancer drugs, there are approximately 45,000 two‐drug combinations and approximately 4.5 million three‐drug combinations. Performing individual phase 1 and 2 trials for customized combinations of agents is not feasible. Therefore, the I‐PREDICT and WINTHER trials took a different tack, allowing individualized combinations of drugs matched to each patient in an N‐of‐1, tailored approach, all within one trial, with intrapatient dose modifications for safety and tolerance (thus incorporating not only personalized drugs but also personalized dosing, including combinations of drugs not previously tested in the phase 1 setting). 9 , 10 , 11 Thus N‐of‐1 trials provide each patient with a unique combination of therapies based on their molecular profiles. A scoring system is used for each patient to calculate how well the patient was matched to combination therapy. Higher matching scores were associated with significantly improved disease control (included partial and complete remission as well as stable disease for at least 6 months), PFS, and OS for both treatment‐refractory and treatment‐naive patients. 9 , 10 The I‐PREDICT N‐of‐1 trial is a rather striking departure from classic cancer clinical trials. It transforms oncology clinical trials and therapies from a drug‐centric approach to a patient‐centric approach (Figure 2). Importantly, dosing of novel combination therapies is critical to providing safe and effective N‐of‐1 treatments without prior phase 1 studies. This can be accomplished by lowering the dose initially and modifying the dose by intrapatient dose escalation; thus not only are the drugs individualized to the patient, but so is the dosing. 12

SPECIAL ISSUES FOR PRECISION MEDICINE CLINICAL TRIALS

Precision immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibition has enabled dramatic improvement in outcomes in many solid tumors. Determining biomarkers that will best predict the subset of patients who will benefit from immunotherapy is important for a precision medicine approach, especially for tumor types that are considered immunologically cold. A subset of tumors that are immunologically active also will not respond, and a better understanding of primary and secondary resistance pathways or lack of immunologically active disease is required for to improve therapy selection. Precision genomics has provided the critical lesson—mostly still not applied to the immunotherapy field—that each cancer has a distinct molecular landscape; and, if biomarkers are not sought and unselected patients are treated, the chance of success for targeted therapies is low. 99 As an example, ALK fusions are present in only approximately 5% of nonsmall cell lung cancers; thus, if ALK inhibitors had been tested in unselected patients with lung cancer, the response rates would have been negligible. 100 Biomarkers such as PD‐L1 expression, microsatellite status, and tumor mutational burden have been used to predict which individuals have a greater probability of responding to PD‐1/PD‐L1 immune checkpoint inhibition. 101 , 102 , 103 , 104

Although traditional immune checkpoint inhibitor–based therapies have been directed at the PD‐1/PD‐L1 axis, there are several other immune checkpoints as well as an enormous array of other immunomodulatory mediators that may contribute to resistance to these therapies. Determining expression patterns of other immune checkpoints may provide benefit in predicting primary or later resistance after an initial response. 105 , 106 Taken together, the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors may be influenced by multiple factors, including, but not limited to: the number of mutanome‐derived neoantigens, probably roughly reflected by high tumor mutational burden and MSI‐H; immunogenicity of the neoantigens; ability of the patient's major histocompatibility complex to present those neoantigens; ability of the patient's T‐cell receptor repertoire to recognize those neoantigens; and which checkpoint the tumor is using to evade the immune system. 107 , 108 , 109 Even so, studies of immunotherapy are mostly devoid of interrogation of any of the above factors; this needs to change.

Precision dosing

A precision medicine personalized approach necessitates novel dosing strategies given the large number of potential therapeutic combinations. With a goal of each patient receiving a personalized, novel combination therapy, the majority of combination regimens will not have clinical trials data to guide safe and tolerable starting doses. Evidence for combination therapy dosing from approximately 100,000 patients has been reported in several large analyses of phase 1–3 clinical trials of two or more drugs for immunotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy, and chemotherapy. 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 These studies from the literature suggested that antibodies were better tolerated than small molecular inhibitors or cytotoxic chemotherapy in combination therapy. The literature and our experience suggest that a starting dose approximately 50% of the single‐agent FDA‐approved dose should be considered for most previously unstudied combination therapies. Combinations that include antibodies can be started at higher doses, whereas certain therapeutics (e.g., mTOR inhibitors, poly[adenosine diphosphate ribose]polymerase inhibitors, histone deacetylase inhibitors, cytotoxic drugs, and ipilimumab) have increased toxicity, requiring more significant dose reductions and increased monitoring. These observations provided a general guideline for starting doses of novel combination therapy and were used in the I‐PREDICT clinical trial to determine starting doses of therapies. 9 , 10 Frequent (at least weekly) laboratory evaluations of liver, kidney, and hematologic function as well as physician visits were obtained for all individuals on the study. Intrapatient dose escalation or reduction was used to titrate therapies to efficacious and tolerable doses. Additional considerations for precision dosing include patient frailty, comorbidities, organ compromise, co‐administered drugs, gender, age, race, and pharmacologic metabolism, which may require additional dose reductions. 12 Importantly, this strategy—starting with lowered doses and intrapatient dose modification, as used in the I‐PREDICT trial—proved safe and effective. 9

The FDA has now initiated Project Optimus as an initiative to reform the dose‐optimization and dose‐selection model in oncology drug development. Too often, according to the FDA, the current paradigm for dose selection—based on cytotoxic chemotherapeutics in which more drug has always been assumed to be better—leads to doses and schedules of targeted therapies that are inadequately characterized before initiating registration trials. 115 This is not surprising because dose selection after phase 1 can be in as few as six patients and determined based on the first cycle (usually about 4 weeks) of therapy. Yet patients may be on targeted drugs for long periods of time. Still, the basic difference between Project Optimus and the I‐PREDICT methodology is that Project Optimus aims to find a more refined dose to apply to all patients, and I‐PREDICT looked for the best‐tolerated dose for each patient and used intrapatient, rather than interpatient, dose modification. 9 , 12 Taken together, the precision paradigm for dosing may require recognition that one size does not fit all and that more is not always better. 116

Timing of precision medicine approaches

Many precision medicine trials have been used in later lines of therapy for solid malignancies. Yet the greatest advances have occurred when precision therapies are applied at diagnosis. Tyrosine kinase BCR‐ABL inhibitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia are extremely effective in the chronic phase of the disease but are ineffective in late‐stage blast crisis. In fact, chronic myelogenous leukemia has been transformed from a uniformly lethal disease to one with a near‐normal life expectancy by applying drugs targeted against the aberrant BCR‐ABL kinase enzyme that drives the disease. However, these drugs must be applied at diagnosis. Waiting until end‐stage disease results in almost negligible impact. 117 , 118

A similar approach—moving these therapies earlier—may lead to better outcomes in solid tumors. Advanced and metastatic cancers tend to acquire more heterogeneity and molecular alterations as disease progresses and as a result of prior lines of therapy; thus it would likely be beneficial to move precision medicine approaches to earlier or even frontline therapy to provide the best chance of success. This is especially true for many rare or extremely aggressive tumors in which the standard‐of‐care options yield limited responses and short OS or tumors in which the standard of care requires mutilating surgery or other therapies with debilitating side effects. A prime example of this strategy was reported in a study published by Cercek and colleagues, in which 12 patients with MSI‐H rectal cancer received the anti–PD‐1 agent dostarlimab at diagnosis, and all 12 had prolonged complete remissions, obviating the need for surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. 119

Discovery in real time

With continued technological advancements, one could envision a future of personalized drug discovery and development in real time. Bioinformatics can be used to determine an optimal therapeutic match for each patient, and a new drug could be developed in real time specific for a patient's tumor and mutational drivers. The therapy could be designed using AI and machine learning and manufactured using three‐dimensional drug printing. 120 , 121 Rather than seeking a regulatory approval for a specific indication, the technology and algorithm for producing an individualized a therapy would be reviewed.

Novel data‐collection methods

New data‐collection methodologies are being explored. Real‐world data can provide a more accurate picture of how a typical patient outside a highly structured, canonical clinical trial with multiple inclusion and exclusion criteria will fare on therapy. Patient‐reported outcomes (PROMs) provide additional perspective on adverse events. Exploring exceptional responders and registry‐based protocols can deliver a deeper understanding of therapeutic benefit. Synthetic arms use data outside of a trial as a comparator arm and thus can offer additional control data.

Real‐world data

The amount of data available today through electronic health and other records is on a scale almost unimaginable a few decades ago. Hence, real‐world data have been explored to determine the efficacy and toxicity of oncology treatments. 122 Clinical trial participants often do not represent the standard oncology patient because trials attempt to cherry pick the ideal oncology patient through the use of numerous selection criteria. These requirements aim to provide optimal patient safety and provide the highest probability of obtaining a response to therapy. A real‐world patient with cancer may have worse performance status, impaired organ dysfunction, major comorbidities, and be receiving potentially interacting therapies. These patients tend to be older and frailer than the clinical trial population. Thus information on the success of approved therapies in the community is critical to determining whether therapies are beneficial and safe.

Real‐world data can be collected from electronic health records, disease registries, medical claims, billing data, and patient‐based applications. Because data collection is much less controlled than a clinical trial, there is a risk of inaccurate reporting and discrepancies in the data. These data have been used to support the approval of new indications, new patient populations, and dose modifications. The FDA supports a Real‐World Evidence Program under the Cures Act to evaluate drug efficacy, support the approval of new indications, and assess the need for dose modification. 123 Real‐world data can also be used as a comparator arm for studies without a control to assess for preliminary efficacy signals, especially in early phase studies.

Registry protocols

Registry protocols provide a rich source of structured data on cancer incidence, demographics, outcomes, treatment, and molecular profiling data. The Master Registry of Oncology Outcomes Associated with Testing and Treatment (ROOT) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04028479), for instance, is collecting comprehensive molecular profile, treatment, outcome, and clinical information on diverse tumor types. 124 , 125 This study is a national master observational trial and aims to assemble real‐world data on innovative treatments and biomarkers using machine learning and AI tools. The difference between real‐world data collection from health records versus registry protocols is that, in registry protocols, although the data are real‐world, the protocol collects the data in a structured manner.

Exceptional responders

Randomized clinical trials data provide a summary of clinical outcomes to determine whether a therapy is safe and effective. If any patients have exceptional responses, this information may not be reported or evaluated in detail. 76 , 126 Additional evaluation and molecular profiling may provide a mechanism for determining the drug benefit and help select the patient population that would derive the most benefit. In the case of a therapeutic that was not believed to be effective in the original population tested, benefit may be identified in a subpopulation. Trials to interrogate exceptional responders may identify novel biomarkers of response and can provide novel insight into the underlying mechanisms of targeted therapies. 127 Given the rarity of exceptional responders, it may be difficult to determine the etiology of the benefit.

Patient‐reported outcomes

PROMs include symptoms, toxicity, and quality of life, which originate directly from the patient. 128 They can be collected from web‐based platforms, phone calls, and downloaded applications. Questionnaires increasingly are being used to detect and monitor symptoms and adverse events. PROMs can improve clinical outcomes and decrease hospitalizations; however, despite recommendations by the FDA to implement them in clinical trials, they rarely contribute to drug approval. 76

Synthetic arms

Synthetic arms use data from outside of the clinical trial to create a comparator arm to compare with the experimental arm of the study. In particular, synthetic control methods represent statistical methodology, which can evaluate the effectiveness of a novel therapy using external control data. 129 These arms can be beneficial for rare tumor studies in which it is hard to accrue patients to both an experimental arm and a control arm. 130 Synthetic control arms are also beneficial for very aggressive tumors in which the standard of care is minimally effective. Given the rapid advancement in oncology therapies and the long duration of trials, the standard of care may also be updated during a trial, which can make it difficult to assess the benefit of the new therapy.

The FDA has recognized the importance of synthetic control arms and has several initiatives to allow for the use of external control data. It is critical to evaluate how closely the experimental group matches the synthetic arm with regard to disease and other patient characteristics to have an accurate assessment of the benefit of the novel therapy.

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING PRECISION MEDICINE APPROACHES

There are several challenges involved in implementing precision medicine approaches and clinical trials. Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in the molecular reclassification of cancer. Clinical trials and practice as well as training and departments in academia are built around disease‐specific expertise. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that cancer is driven by its molecular alterations.

There are also practical issues that challenge precision medicine trials and practice. Although the turnaround in NGS for tissue and liquid biopsies has improved, finding and releasing tissue from pathology to be sent to the laboratory that conducts the testing can lead to delays. Some of these challenges can be overcome by instituting reflex and universal genomic testing. 131 , 132

Because tumors tend to acquire new alterations over time, tissue from several years prior may not provide an accurate picture of the current molecular landscape of the tumor, and obtaining a new biopsy may delay treatment. Liquid biopsies (derived from a simple blood test), however, can provide current NGS data.

Another challenge is medication acquisition. In platform precision medicine trials, patients may be navigated to secondary clinical trials with investigational agents based on their biomarkers. However, the numerous inclusion and exclusion criteria often make patients ineligible. Drugs can also be used off label. For instance, in the I‐PREDICT trial, 9 , 10 , 91 off‐label, targeted therapies were obtained through patient‐assistance programs. Despite an experienced team of medication‐acquisition specialists, medication acquisition often took several weeks because of delays from insurance and patient‐assistance program reviews. Not all patients were eligible for patient‐assistance programs, especially those with higher incomes. For combination therapy trials, coordination with multiple pharmaceutical companies can also present a challenge during study start‐up. Moreover, methodologies using medication‐acquisition specialists for clinical trials are not scalable. Eventually, algorithms governing which combinations of drugs are best for each patient should be approvable based on the robustness of the outcome seen in clinical trials, and that would or should make the suggested medications covered by payors.

Precision medicine trials often assume that response to a targeted therapy can be evaluated independent from the tissue of origin and independent of other molecular aberrations in a tumor. As an example, whereas dabrafenib/trametinib has a tissue‐agnostic approval for solid tumors with BRAF V600E alterations, this excludes colorectal cancers, which have very poor response rates. Conversely, BRAF inhibition in BRAF V600E colorectal cancer was greatly improved with the addition of cetuximab. 133 The combination of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib and the EGFR antibody cetuximab is now FDA‐approved for this indication.

Many currently enrolling precision medicine trials have a limited number of therapies and targetable alterations assessed, which can lead to a low rate of matching patients to therapies. Trials assessing a single, rare alteration will need to screen a large number of patients to a find match. A prior review noted that the majority of studies matched about 15%–20% of patients to drugs. 51 The I‐PREDICT study 9 , 10 administered matched therapy at a rate of close to 50% by using a broad NGS panel and all available FDA‐approved therapies to match the alterations.

Appropriate outcome measures should be considered for precision medicine trials. Rate and duration of response are often used but may not be adequate surrogates for survival. The ratio of PFS with the targeted therapy compared with PFS after previous lines of therapy (PFS2/PFS1) within the same individual has been used in some studies to assess the benefit of the matched therapy. However, this parameter has proven problematic because the PFS on the prior therapy, often given in the community, may be determined based on imaging every 3 months, whereas protocols mandate imaging every 2 months; this difference can attenuate the ability to find improvements.

ADDRESSING DISPARITIES AND UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Although precision medicine trials and approaches offer great promise to improve outcomes and revolutionize oncology therapy, providing broad access to all patients remains challenging. Patients who do not live close to large academic medical centers, especially those in rural communities or underserved minorities, may have difficulty enrolling on trials given the frequent visits required along with the time and cost of travel. Trials that are open in large numbers of sites or have remote enrollment can help bridge this gap.

Home run trials

Patients with advanced and metastatic cancer face challenges in navigating the clinical trials process. Most trials are only open in limited locations; thus patients may have to travel long distances or even move to a new location for a period of time to have the option of participating in a trial to receive novel therapies. Travel is expensive and can be challenging for patients who have symptoms from disease or therapy. The concept of a home run trial, in which a patient can receive therapy from home, can occur either by opening the study at a large number of sites or making the study fully remote. 134

The DART study was designed as an immunotherapy platform for rare cancers. It included 53 cohorts of rare cancers with a primary end point of RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) response and included a not otherwise categorized tumor cohort. The study aimed to allow patients with rare tumors access to immunotherapy through clinical trials. A single site activation was equivalent to opening 53 trials in one protocol; and, at the peak of the study, it was open at more than 1000 sites across the NCI SWOG National Cooperative Trials Network, allowing access to patients across the United States. Multiple cohorts have been published in peer‐reviewed literature 81 , 82 , 135 , 136 or presented at national meetings. 134

The NCI‐MATCH trial was a national platform trial for genomically matched tumor groups. It had centralized diagnostic testing with multiple treatment options in parallel. NCI‐MATCH enrolled a total of 1201 patients in 38 cohorts at 1117 sites between 2017 and 2022. It demonstrated the feasibility of nationwide accrual of patients on a platform with multiple, rare, genomic basket subgroups across numerous tumor types. 40 Several matched therapies met the study response end points and included PIK3CA with copanlisib 137 and AKT1 E17K targeting with capivasertib. 138

The TAPUR study is being conducted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. It is a nonrandomized study that provides FDA‐approved, targeted oncology therapeutics for potentially actionable genomic alterations to identify potential signals of drug activity. TAPUR can rapidly generate clinical efficacy and safety data on diverse treatment agents for specific cohorts based on molecular profiling, which may enable opening larger studies. It also allows for various Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments‐certified laboratories and molecular profiling platforms. The study is open and enrolling at 267 sites across the United States. 139 Results have been published from several cohorts, 45 , 46 , 47 and the study is still ongoing.

The TRACK (Target Rare Cancer Knowledge) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04504604) is a national precision medicine (N‐of‐1), decentralized study for rare tumors run by the TargetCancer Foundation. The study is fully remote and aims to establish whether patients with rare tumors will benefit from individually matched molecular therapies. The trial staff obtain remote consent, arrange for mobile phlebotomy, obtain medical records, and contact both the patient and the physician. NGS testing from liquid and tissue biopsy are used by a virtual molecular tumor board (MTB) to provide matched therapy recommendations of FDA‐approved therapies or recommendations for clinical trials. The MTB includes expert oncologists, pathologists, molecular genomics specialists, a pharmacist, a genetic counselor, and a medication‐acquisition specialist. The MTB provides written recommendations to the home oncologist who selects and delivers the therapy. The study opened October 2020 and the goal accrual is 400 patients. 134 , 140

Community networks

Large community networks can offer care, including clinical trials, to patients in local communities. For instance, the US Oncology Network has offered >2000 cancer clinical trials to their patients, enrolled >88,000 patients in oncology clinical trials in communities across the country, and contributed to approximately 100 FDA‐approved cancer therapies. At any one time, >500 oncology clinical trials are in progress in the network. Finally, more than 2500 physicians at over 600 treatment locations across the country participate in this network.

Equity/diversity/inclusion in precision medicine trials

Strategies that research teams can adopt to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) need to span the totality of the research path, from the initial design to the shepherding of clinical data through a potential regulatory process. These strategies include, but are not limited to: (1) more intentionality and DEI‐based goal‐setting, (2) more diverse research and leadership teams, (3) better community engagement to set study goals and approaches, (4) tailored outreach interventions, (5) decentralization of study procedures and incorporation of innovative technology for more flexible data collection, (6) self‐surveillance to identify and prevent biases as well as focus on eligibility, (7) participant/patient engagement, (8) feedback through patient advocacy organizations and community interactions, (9) supporting efforts to recruit diverse and underrepresented trial populations, and (10) establishing relationships and demographic target‐goal tracking, which should be maintained throughout trial management. 141 , 142 All these are implementable tools that can make study participation more palatable to diverse communities and ultimately generate evidence that is more generalizable and a conduit for better outcomes.

As oncology trials and treatments shift toward molecularly based approaches, we anticipate that molecular testing will become standard of care for patients with cancer; and a defined methodology for matching therapies to molecular alterations, including which therapeutic targets to prioritize, will be included in cancer treatment guidelines. The methodology for matching therapies to molecular alterations should be taught as part of oncology training and continuing medical education, which will allow access to expertise in these approaches, including in community and rural practices. Moreover, high‐standard diagnostic NGS technologies, including those that are FDA approved and hence covered by payors, are already available from several vendors, easing access and potentially democratizing their uptake.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE