Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects more than 6.2 million Americans aged 65 and older, particularly women. Along with AD’s main hallmarks (formation of β-amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles), there are vascular alterations that occurs in AD pathology. Adenosine A2 receptor (A2AR) is one of the key factors of brain vascular autoregulation and is overexpressed in AD patients. Our previous findings suggest that protein arginine methyltransferase 4 (PRMT4) is overexpressed in AD, which leads to decrease in cerebral blood flow in aged female 3xTg mice. We aimed to investigate the mechanism behind A2AR signaling in the regulation of brain perfusion and blood–brain barrier integrity in age and sex-dependent 3xTg mice, and if it is related to PRMT4. Istradefylline, a highly selective A2AR antagonist, was used to modulate A2AR signaling. Aged female 3xTg and C57BL/6 J mice were evaluated for brain perfusion (via laser speckle) and cognitive function (via open field, T-maze and novel object recognition). Our results suggest that modulation of A2AR signaling in aged female 3xTg increased cerebral perfusion by decreasing PRMT4 expression, restored the levels of APP and tau, maintained blood–brain barrier integrity by maintaining the expression of tight junction proteins, and preserved functional learning/memory.

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Adenosine A2 Receptor, Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 4, Brain Perfusion

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia that affects more than 6.2 million Americans aged 65 and older [1]. Women are more likely to develop a rapid progression of AD [2] compared to men when predictive factors, such as obesity, lifespan, and enhanced stroke severity are considered [3–7]. Derangements in cerebral perfusion have been observed alongside AD’s main hallmarks, including the formation of β-amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles [8]. In fact, considering that hypoperfusion is observed in the early pre-clinical phases of AD [9] and the co-occurrence with other hallmarks of AD (in addition to plaques and tangles), such as vascular amyloid deposits, atrophy, and stenosis; it is difficult to set the chronology of events in the development of AD pathology [10].

The multi-factorial aspects of AD pathology pose various treatment challenges [11], therefore targeting novel pathways that contribute to AD progression is crucial due to limited treatment modalities. Adenosine A2 receptor (A2AR), a G-protein-coupled receptor that is important for brain vascular autoregulation [12], was observed to be overexpressed in postmortem brain and platelets of AD patients [13]. Interestingly, A2AR has been shown to be the primary receptor responsible for the vasodilatory effects of adenosine [14]. In addition, previous work has shown that blockade of A2AR is able to prevent amyloid-beta-induced synaptotoxicity in some animal and cell culture models [15].

We previously established an important role for protein arginine methyltransferase 4 (PRMT4) in AD. PRMT4 is an enzyme that methylates arginine residues leading to posttranslational modification such as mRNA splicing, DNA repair, and modification of protein expression. Overexpression of PRMT4 has been correlated with age-related neurodegenerative diseases [16]. We also found a sex specific phenotype where only aged female 3xTg mice (a triple-transgenic mouse model of AD) had overexpressed PRMT4 and decreased brain perfusion, which was reversed by treatment with TP-064, a potent and selective PRMT4 inhibitor [17].

Considering that PRMT4 and A2AR protein levels are both elevated in the blood of female AD patients and in the brain of aged female 3xTg mice, we aimed to investigate the involvement of PRMT4 and A2AR signaling in the regulation of brain perfusion and receptor signaling in age and sex-dependent AD. Thus, we modulated A2AR signaling in the aged female 3xTg mice to evaluate brain perfusion and receptor signaling. Here, we show that blockade of A2AR signaling result in an increased brain perfusion, decreased PRMT4 signaling, restored tight junction proteins, and improved functional learning/memory in aged 3xTg female mice.

Material and methods

Animals

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth) at Houston, TX (protocol AWC-24–0006). This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and followed ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) [18]. Young (3-month-old) and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg and C57BL/6 J (C57) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Farmington, CT), acclimatized for a minimum of 1 week before use. All mice were housed in a controlled environment (20° ± 2° C, humidity 50 ± 5%) under a 12:12-h light–dark cycle (lights on from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.) with unrestricted access to standard rodent chow and filtered water.

Experimental design

Young and aged 3xTg male mice were used only for cortical brain perfusion as a parameter for sex differentiation in Alzheimer’s disease. After acclimation, aged female mice were weighed and randomly distributed into groups (control v. drug treatment). All female animals were evaluated for behavior baseline performance via open field and T-maze test. Subsequently, animals were subjected to brain perfusion analysis (via laser speckle) followed by treatments with saline (0.9%, 1 mL/Kg – control) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg—TOCRIS, #5147) for 7 consecutive days (i.p.). 12 h after the last dose, mice were evaluated for behavior performance on open field, T-maze, and novel object recognition. After behavior analysis, brain perfusion was evaluated again, and mice were submitted to euthanasia for tissue collection.

Anesthesia

General anesthesia was induced in a plexiglass chamber with 5% isoflurane (cat. No. 21295098, Patterson Veterinary, Greeley, CO) mixed with O2 and N2O (30:70) until loss of responsiveness to sensory stimuli. During experimental procedures, anesthesia was maintained with 1.5%—2% isoflurane. Body temperature was monitored via a rectal probe and maintained at 37 °C with a heating pad system (RWD ThermoStar®, San Diego, CA).

In vivo laser speckle contrast imaging

Cortical microvasculature was captured using RFLSI III Speckle Contrast Imaging System (RWD ThermoStar®, San Diego, CA). The anesthetized mouse was placed in a stereotaxic frame to stabilize the head; an incision in the scalp gave access to the skull that was thinned using a high-speed drill irrigated with saline to avoid overheating. Each mouse was imaged for 5 min (laser intensity: 80 mW). LCSI software (RWD ThermoStar®, San Diego, CA) was used to calculate relative brain perfusion by pixel intensity.

Protein quantification

All protein quantifications were analyzed through capillary electrophoresis (ProteinSimple®, Bio-techne, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, proteins were extracted with T-PER® Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, cat. No 78510) with 1 × Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific, cat. No. 78440) (50 mg of tissue per mL) and centrifuged 10,000 × g for 15 min (4 ⁰C). The supernatant was diluted with sample buffer (ProteinSimple®—1 mg protein/mL) and mixed with a reducing agent (DTT) containing fluorescent standards. Samples were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min. Primary antibodies used in this manuscript were: ZO-1 (Abcam, ab96587, 1:100), occludin (ProteinTech, 13,409–1-AP, 1:100), ADORA2A (Novus Biologicals, NBP1-39,474, 1:50), PRMT4 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4438S, 1:50), eNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, 5880S, 1:200), iNOS (Novus Biologicals, NB300-605, 1:100), and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) (Cell Signaling Technology, 13,522, 1:100). Antibody targets were detected with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody (Bio-techne®, cat. No. DM-001 and DM-002, respectively). Protein levels were evaluated by the area under the curve (AUC) obtained via the Compass for SW software (version 4.0.0, Protein Simple®, Bio-techne, Minneapolis, MN). Relative protein expression was calculated by protein peak intensity normalized by total protein as per the manufacturer’s instruction. Representative computer-generated pseudo-bands (by Compass for SW software) were presented throughout the figures where applicable.

Animal behavior tests

All behavior tests were performed from 9 a.m. up to 1 p.m., after 10 min of room habituation, as previous established by Couto e Silva [19]. All behavior apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol between each animal to avoid bias of smell traces. Behavior parameters were analyzed via ANY-maze software (version 7.0, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL).

Open-field test

The open field apparatus consisted of a cube arena measuring 24 × 24 × 24 cm (L x W x H), made of matte white high-density acrylic panels. The arena floor was divided into 36 squares to obtain corners and central zones of similar size (4 cm2 each). The total distance traveled was analyzed. Each test was recorded for 10 min.

T-maze

The T-maze apparatus is a T-shaped maze made of matte white high-density acrylic panels featuring a stem (start arm) and two lateral goal arms (left and right arms).

The test consists in a total of 10 trials, with a 10 min interval after the first 5 trials. The procedure is based on the natural tendency of rodents to prefer exploring a novel arm over a familiar one, performing a spontaneous alternation behavior between the goal arms across repeated trials. This test evaluates spatial working memory. The animal that did not choose an arm in 3 min returned to their home cage and was scored as 0 for all 5 trials. After 10 min intervals, the animal was tested again. If the animal still refused to walk or to choose an arm it was excluded from the test. Spontaneous alternation was calculated as percentage of alternation.

Novel object recognition

This behavior paradigm consists of 3 consecutive days: Day 1—5 min habituation in an empty square arena (24 × 24 × 24 cm) made from matte white high-density acrylic panels. Day 2—two similar objects were placed on apart from each other, and mice were placed in the center, facing an empty corner; Day 3—one object from the day 2 (familiar object) was replace by a new object and mice were placed in the center, facing an empty corner. Mice were allowed to freely explore the objects and the arena for 10 min. The exploration of the new object was evaluated regarding frequency of interaction.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software for Windows, version 10.3 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). We used analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s post-hoc tests, and unpaired Student’s T-test. Bartlett's test was used to determine data homogeneity. The difference was considered statistically relevant when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Cerebral hypoperfusion of aged 3xTg female mice was restored by adenosine 2A receptor (A2AR) antagonist

Cerebral blood flow impairments have been observed alongside AD proteinopathies in several AD models. Our results from 3xTg mice (AD mouse model) showed no sex difference in young mice (3-old-months) of brain perfusion in the cortex (300.3 ± 13.1 A.U., p > 0.05 for females and 303.5 ± 26.8 A.U., p > 0.05 for males). However, at 12–15 months of age, we observed a severe reduction of cortical brain perfusion in aged females v. aged males (195.7 ± 8.4 A.U., p < 0.01 for females versus 234.4 ± 12.3 A.U., p < 0.05 for males) (Fig. 1A). After treatment with istradefylline, a highly specific A2AR antagonist, (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, i.p.), aged 3xTg female mice (12 to 15-month-old) had similar cortical brain perfusion v. aged C57 and young 3xTg female mice (296.4 ± 16.6 A.U., 321.5 ± 18.6 A.U., and 300.3 ± 13.09 A.U., respectively, p > 0.05—Fig. 1B) to suggest that blockade of A2AR restored cerebral cortical perfusion in aged female AD mice.

Fig. 1.

Cerebral hypoperfusion of aged 3xTg female mice was restored by A2AR antagonist. A Brain perfusion was measured via laser speckle imaging in the brain of male/female of young (3-month-old)/aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg mice (no treatment). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 comparing young vs aged mice; #p < 0.05 comparing male vs female mice, via two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. B Inhibition of A2AR with istradefylline (a specific A2AR antagonist—2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP) restored cerebral perfusion in aged 3xTg female mice. @p < 0.01 v. aged C57BL/6 J (C57—gray bar), young (white bar) and aged 3xTg female mice treated with istradefylline (green bar) via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. C-D Representative mice cortical images of brain perfusion. (n = 7–10/group)

A2AR protein levels were elevated in aged 3xTg female mice

We sought to investigate if inhibition of A2AR could also reduce the overall levels of this receptor. Our results suggest that aged 3xTg female mice have higher levels of A2AR in the cortex (0.153 ± 0.005 A.U., p < 0.01) and hippocampus (0.176 ± 0.024 A.U., p < 0.01) as compared to similar sex, aged C57BL/6 J mice (0.093 ± 0.002 A.U. and 0.088 ± 0.005 A.U., respectively) and the antagonism of A2AR (via istradefylline) did not change receptor levels (0.137 ± 0.018 A.U. and 0.149 ± 0.011 A.U., respectively, p > 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A2AR protein levels are elevated in aged 3xTg female mice. Proteins were quantified by capillary electrophoresis (ProteinSimple) in the cortex (A) and hippocampus (B) of aged (12 to 15-month-old) C57 female mice with saline treatment (gray bars), and aged 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red bars) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg, 7 days, IP—green bars). Representative pseudoblots are presented below each bar graph. Protein levels were quantified via capillary electrophoresis and normalized to total protein. *p < 0.01 via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (n = 6–8/group)

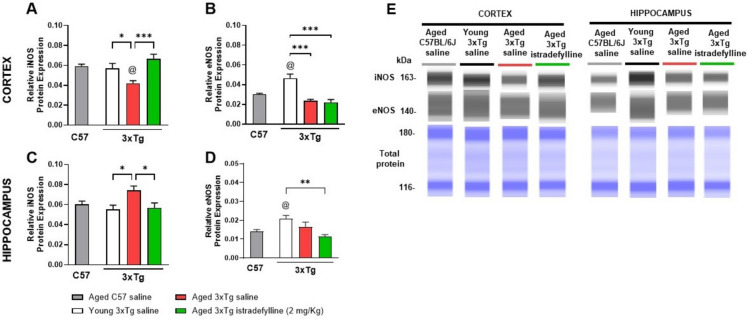

Blockade of A2AR restored iNOS in aged 3xTg female mice

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) produces nitric oxide (NO) when induced by various stimuli (hypoxia, stress, etc.) [20]. Our results suggest that young 3xTg female mice presented similar cortical (Fig. 3A) and hippocampal (Fig. 3C) iNOS levels (0.059 ± 0.002 A.U., p > 0.05 and 0.055 ± 0.004 A.U., p > 0.05, respectively) v. aged C57 mice (0.057 ± 0.05 A.U. and 0.060 ± 0.003 A.U., respectively). Aged 3xTg mice presented with lower levels in the cortex (0.0042 ± 0.003 A.U., p < 0.05), but higher in the hippocampus (0.074 ± 0.004 A.U., p = 0.11). In the presence of istradefylline, iNOS in the cortical (0.066 ± 0.005 A.U., p < 0.001) and hippocampal (0.061 ± 0.006 A.U., p < 0.05) levels were similar to young 3xTg mice. Young 3xTg mice were the only group with high eNOS levels in both cortex (0.047 ± 0.004 A.U., p < 0.001) and hippocampus (0.021 ± 0.002 A.U., p < 0.01) (Figs. 3B and 3D). Aged C57 and aged saline-treated 3xTg mice presented similar eNOS levels in the cortex (0.030 ± 0.001 A.U. and 0.024 ± 0.001 A.U., respectively, p > 0.05) and hippocampus (0.014 ± 0.001 A.U. and 0.017 ± 0.003 A.U., respectively, p > 0.05), as well as aged istradefylline-treated 3xTg mice (cortex: 0.022 ± 0.003 A.U., p > 0.05; hippocampus: 0.011 ± 0.001 A.U., p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Blockade of A2AR restored cortical iNOS levels in aged 3xTg female mice. Protein levels were quantified via capillary electrophoresis and normalized to total protein (ProteinSimple) in the cortex (A-B) and hippocampus (C-D) of aged (12 to 15-month-old) C57 female mice (gray bars), young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (white bars), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red bars) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP—green bars). Representative pseudoblots are presented (E). @p < 0.05 vs aged C57BL/6 J mice; *p < 0.05 between 3xTg mice, via one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (n = 7–8/group)

Blockade A2AR reduced APP and Tau levels in aged 3xTg female mice brain

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and microtubule-associated protein tau are central to AD pathology [21]. Our results suggest that aged 12 to 15-month-old 3xTg mice have elevated levels of APP in the cortex (0.099 ± 0.005 A.U., p < 0.001 – Fig. 4A) and hippocampus (0.069 ± 0.01 A.U., p < 0.001 – Fig. 4D) v. 3-month-old mice (0.053 ± 0.004 A.U. in the cortex and 0.031 ± 0.003 A.U. in the hippocampus). Similarly, tau levels were significantly higher in aged mice in both brain regions (3.183 ± 0.1110 A.U., p < 0.001 in the cortex and 4.856 ± 0.3488 A.U., p < 0.001 in the hippocampus), with approximately 1.7-fold more tau in aged than in young mice (Figs. 4B and 4E). Blocking A2AR via istradefylline reduced the levels of both APP (0.041 ± 0.003 A.U., p < 0.001 in the cortex and 0.035 ± 0.002 A.U., p < 0.001 in the hippocampus) and tau (2.702 ± 0.04 A.U., p < 001 in the cortex and 3.607 ± 0.26 A.U., p < 0.001 in the hippocampus) comparable to young mice. No significant differences were observed between groups in the cortex (Fig. 4C) of phosphorylated tau (pTau). However, in the hippocampus (Fig. 4F), aged 3xTg female mice exhibited higher levels of pTau v. young mice (0.3572 ± 0.01265 A.U., p < 0.01), and blockade of A2AR did not prevent tau hyperphosphorylation.

Fig. 4.

Blockade of A2AR reduced APP and Tau levels in aged 3xTg female mice brain. Protein levels were quantified via capillary electrophoresis and normalized to total protein (ProteinSimple) in the cortex (A-C) and hippocampus (D-F) of young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (white bars), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red bars) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP – green bars). G Representative pseudoblots are presented. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (n = 6/group)

Blockade of A2AR reduced PRMT4 and ADMA in aged 3xTg female mice

Protein arginine methyltransferase 4 (PRMT4), also known as CARM1, modulates several protein functions by asymmetrically adding two methyl groups to arginine residues on proteins, resulting in the production of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) on proteins. It is important to note that PRMT4 and ADMA plays an important role in NO-mediated control of vascular tone. Our results suggest that young 3xTg mice have similar cortical PRMT4 (0.042 ± 0.003 A.U., p > 0.05) and ADMA (0.048 ± 0.009 A.U., p > 0.05) levels v. aged C57 mice (PRMT4: 0.038 ± 0.001 A.U.; ADMA: 0.040 ± 0.006 A.U.). These levels were significantly elevated in aged 3xTg mice, with cortical PRMT4 at 0.047 ± 0.002 A.U. (p < 0.05) and ADMA at 0.155 ± 0.01 A.U. (p < 0.001), both reduced in the presence of istradefylline treatment (PRMT4: 0.032 ± 0.001 A.U.; ADMA: 0.079 ± 0.008 A.U., both p < 0.001) (Fig. 5A and 5B) with similar results in the hippocampus (Fig. 5C and 5D). Aged 3xTg mice exhibited increased levels of PRMT4 (0.063 ± 0.004 A.U., p < 0.001) and ADMA (0.142 ± 0.01 A.U., p < 0.001) as compared to aged C57 mice (PRMT4: 0.045 ± 0.003 A.U.; ADMA: 0.050 ± 0.01 A.U.). Blockade of A2AR with istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP) decreased PRMT4 (0.041 ± 0.003 A.U.; p < 0.001) and ADMA (0.088 ± 0.006 A.U.; p < 0.01) in aged 3xTg mice to similar levels in aged C57 mice.

Fig. 5.

Blockade of A2AR reduced PRMT4 and ADMA in aged 3xTg female mice. Protein levels were quantified via capillary electrophoresis and normalized to total protein (ProteinSimple) in the cortex (A-B) and hippocampus (C-D) of aged (12 to 15-month-old) C57 female mice (gray bars), young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (white bars), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red bars) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP – green bars). Representative pseudoblots are presented in E. @p < 0.05 vs aged C57BL/6 J female mice; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 comparison between 3xTg female mice via one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (n = 6–8/group)

Blockade of A2AR restored cortical blood–brain barrier-related proteins

To test if blockade of A2AR could improve BBB integrity, we evaluated occludin (transmembrane) and ZO-1 (scaffold) proteins. Our results suggest that (Figs. 6A and 6B) cortex of aged saline-treated 3xTg have lower occludin levels (1.12 ± 0.198 A.U., p < 0.01) v. aged C57 mice (3.10 ± 0.12 A.U.) and lower levels of ZO-1 (0.49 ± 0.04 A.U., p < 0.05) than young 3xTg mice (0.77 ± 0.08 A.U.). In the hippocampus (Figs. 6C and 6D), occludin levels were unchanged between groups, but ZO-1 was reduced in aged 3xTg (0.69 ± 0.06 A.U., p < 0.01) compared to aged C57 (0.99 ± 0.05 A.U.), and blockade of A2AR increased ZO-1 levels (0.81 ± 0.07 A.U., p = 0.40).

Fig. 6.

Blockade of A2AR restored cortical tight junction proteins. Occludin and ZO-1 protein levels were quantified via capillary electrophoresis and normalized to total protein (ProteinSimple) in the cortex A-B and hippocampus C-D of aged (12 to 15-month-old) C57 female mice (gray bars), young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (white bars), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red bars) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP – green bars). Representative pseudoblots are presented in E. @p < 0.0001 vs aged C57BL/6 J female mice; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 between 3xTg female mice, via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. (n = 8/group)

Blockade of A2AR improved exploratory behavior in aged 3xTg female mice

We evaluated the animals’ general exploratory behavior in an open field arena as a measure of anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 7). Compared to baseline measures, young 3xTg mice had a reduction in arena exploration from 5.46 ± 1.58 m to 1.12 ± 0.28 m (p < 0.05—Fig. 7A). Aged saline-treated 3xTg mice did not show differences between basal (3.35 ± 0.66 m) and saline treatment (3.25 ± 0.63 m, p > 0.05—Fig. 7B), but aged istradefylline-treated 3xTg mice had an increase in distance walked in the open-field from 1.31 ± 0.20 m to 4.59 ± 0.63 m (p < 0.01, Fig. 7C), to suggest decreased anxiety-like behaviors.

Fig. 7.

Blockade of A2AR improved exploratory behavior in aged 3xTg-AD female mice. Exploratory behavior was measured via open field before (basal) and after 7 days of treatment, in young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (A), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (B) or istradefylline (C); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 via paired t-student test (n = 6/group). D Representative tracking of distance traveled in open-field arena, tracked by ANY-maze software. (n = 6–7/group)

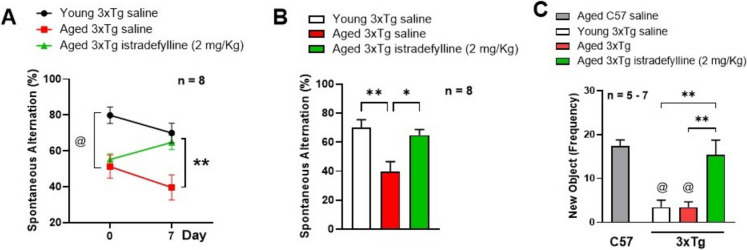

Blockade of A2AR prevented age-related memory decline in 3xTg female mice

We investigated working memory via T-maze before and after treatment with saline or istradefylline (Figs. 8A and 8B) and long-term memory after treatments via novel object recognition (Fig. 8C) in 3xTg female mice. Our results suggest a higher spontaneous alternation percentage in young (80%) v. aged mice (50%) at baseline (p < 0.01), and both groups declined by 10% after saline treatment. However, blockade of A2AR with istradefylline increased the spontaneous alternation percentage by 10%, from 55 to 65% (Fig. 8A). In summary, 7 days treatment with istradefylline improved working/acute memory in aged 3xTg female mice (p < 0.05), similar to the levels of young female mice (Fig. 8B). Regarding long-term memory, both young and aged saline-treated 3xTg female mice had reduced exploration of the new object (3.4 ± 1.6, p < 0.01 and 3.5 ± 1.2, p < 0.001, respectively) v. aged C57 (17.4 ± 1.4), which was enhanced by A2AR antagonism (15.3 ± 3.4, p < 0.01) (Fig. 8C), to suggest that A2AR antagonism improved short- and long-term memory in aged 3xTg female mice.

Fig. 8.

Blockade of A2AR prevented age-related memory decline in 3xTg-AD female mice. Working memory was evaluated via T-maze test before (basal) and after 7 days of treatment (A) on young (3-month-old) 3xTg female mice (black line), and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice treated with saline (red line) or istradefylline (2 mg/Kg/day, 7 days, IP—green line); **p < 0.01 via two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. B Percentage of spontaneous alternation of young (white bar) and aged (12 to 15-month-old) 3xTg female mice after 7 days of treatment with saline (red) or istradefylline (green); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. C Long-term memory was evaluated via novel object recognition on young (white bar), on aged (12 to 15-month-old) C57 female (gray bars), and on aged 3xTg female mice after 7 days of treatment with saline (red) or istradefylline (green). @p < 0.01 compared to aged C57BL/6 J female mice, **p < 0.01 compared to aged 3xTg female mice treated with istradefylline via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. (n = 5–8/group)

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathophysiology is characterized by the production and aggregation of Aβ oligomers, which turn into plaques, and hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein Tau [21]. Besides the classic well-known amyloid cascade hypothesis as a key component of AD, exacerbated age-related vascular changes are observed across the brain [22, 23]. Vascular insufficiencies are present in at least 50% of all AD cases [24], and other risk factors such as hypertension and atherosclerosis increase vascular-related damage leading to progressive cerebral hypoperfusion [25].

We previously showed that 3xTg mice, a triple-transgenic mouse model of AD, had brain perfusion impairments similar to human AD patients [8, 26]; here, we observed that young 3xTg mice (3-month-old) had about 1.5-fold higher brain perfusion than aged animals (12 to 15-month-old) (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, we observed that aged female mice possessed even lower brain perfusion than aged male mice. In fact, women are more prone to the development AD, with a 70% female-to-male prevalence [27, 28], and with more severe decrease in cerebral blood flow (CBF) than males [29, 30]. Although mice are generally considered elderly after 24 month of age [31], we choose to work with 12 to 15-month-old mice to mimic the beginning of reproductive senescence and hormonal characteristics associated with human menopause [32].

The 3xTg mouse model carries three mutations associated with familial AD: they are a PS1M146V knock-in mouse, with human APPSwe, and tauP301L mutations [33]. At 4 months of age, the animals exhibit deficits in information retention, accompanied by decreased hippocampal long-term potentiation, suggesting early synaptic dysfunction [34]. By 6 months, they show spatial memory impairments similar to the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage observed in humans [35]. Female mice develop both plaques and tangles by 12 months of age, while male mice develop these alterations at 18 months [36]. The unique age-dependent development of both plaques and tangles, along with disease progression over time, makes the 3xTg-AD a comprehensive model to represent AD pathology.

Brain vascular control is based on vessel capacity to dilate or constrict depending on peripheral blood pressure and to meet the neurons high glucose and oxygen demands, as major adenosine triphosphate (ATP) consumers. A key player in brain vascular reactivity is the adenosine system. Adenosine is an endogenous nucleoside found in all cells; in the brain it plays important role in the regulation of synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability [37], and in the cerebral vasculature it plays a vital role by dilating blood vessels and regulating blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability [38]. All four adenosine receptors, named A1, A2A, A2B, and A3, are membrane-bound G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that transduce external stimuli into signaling cascades within the cells [39]. Some studies suggest that aged animals have exacerbated levels and activity of A2AR [40–42], that is even more elevated in AD [43–45]. Furthermore, a study in AD patients showed that A2AR density was significantly higher than control postmortem brains in frontal white matter and hippocampus [13]. This led us to investigate the potential mechanisms and consequences of high A2AR in the brain. Interestingly, we observed that our aged 3xTg mice, treated with istradefylline, a specific A2AR antagonist, for 7 days (2 mg/kg/day, I.P.) improved the overall cerebral perfusion (Fig. 1B) without interfering with A2AR levels in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 2A and 2B); although the receptor levels were significantly higher in aged 3xTg mice than in healthy aged C57 mice. It is important to note that brain perfusion is directly linked to blood pressure, which is determined by vascular tone. Narrowing of the vessels increases vascular resistance, thereby raising blood pressure and reducing blood flow. Conversely, decreasing resistance increases blood flow [46, 47]. Impaired vascular autoregulation, defined as the vessel’s ability to dilate or contract in response to hemodynamic changes, is directly associated with reduced cerebral blood flow and cognitive impairment [48]. In fact, in AD rat model (TgF344-AD), cerebral hypoperfusion was linked to hemodynamic dysfunction, characterized by a loss of vascular smooth muscle cell contractility and poor vascular autoregulation, which was exacerbated with age [49].

Vessel resistance decreases with vasodilation, which can be attributed to increased release of nitric oxide (NO), synthetized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [20]. In fact, endothelial NOS (eNOS) levels were higher in young 3xTg than in aged mice, including the aged healthy C57 mice (Fig. 3B and 3D); this is likely attributed to aging process since eNOS levels decrease as a result of aging itself [50–53]. Although blockade of A2AR did not change eNOS levels in aged 3xTg mice, it elevated the levels of inducible NOS (iNOS) in the cortex (Fig. 3A), and decreased it in the hippocampus (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that cortical hypoperfusion was restored by blockade of A2AR through activation of iNOS (Fig. 3A), and in the hippocampus iNOS may be elevated due to inflammatory cytokines from the high levels of pTau [54–56] (Fig. 4F). Moreover, some researchers have also suggested a compensatory role of iNOS in the absence of eNOS [57].

During the brain perfusion measurement, we anesthetized the animal using 5% isoflurane in a mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide (N2O) (30:70). The percentage of isoflurane was then reduced to 1.5 – 2% to maintain optimal anesthesia depth without interfering with the cardiovascular physiological state, ensuring stable vascular resistance, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration rate [58]. Although isoflurane is known to cause dose-dependent cerebral vasodilation through increased NO production [59], it has also been reported to cause vasoconstriction in vessels with preexisting low tone [60]; therefore, it was important to maintain isoflurane levels at a concentration that allowed meaningful observations of in vivo cerebral blood perfusion without introducing excessive variability, in both control and experimental groups. The limitation of our study is that blood pressure was not measured in tandem with blood flow via laser speckle flowmetry. Despite this, we measured overall brain NOS as an indirect indicator of vascular tonicity.

As expected, our 3-month-old 3xTg mice did not express alterations in amyloid precursor protein (APP) nor Tau levels, because such AD characteristics are developed after 6-month-old [61], thus the aged mice have both APP and Tau elevated in their cortex (Fig. 4A and 4B) and hippocampus (Fig. 4D and 4E), which were reduced by blockade of A2AR. Elevated levels of Tau and APP are associated with the formation of plaques and tangles [62], which are related to brain blood flow reduction [8], and so hypoxia-mediated iNOS activation [63, 64]. Since blockade of A2AR reduced Tau and APP levels; this also may explain the decrease in iNOS levels.

Our previous studies [17] suggest that 9-month-old female mice have increased levels of PRMT4 and ADMA in the hippocampus. Here, our results suggest that 12 to 15-month-old 3xTg mice have high levels of PRMT4 and ADMA in both cortex and hippocampus, suggesting that AD can progress with age from deeper structures from the hippocampus to the cortex, together with elevated PRMT4 levels. 3xTg mice have decreased NOS. This may be due to enhanced ADMA, an endogenous NOS inhibitor [17], through the PRMT4 pathway.

Interestingly, we also observed that young 3xTg mice exhibit overexpression of PRMT4 and ADMA proteins in the hippocampus, but not in the cortex, and blockade of A2AR restored similar to healthy aged C57 mice (Fig. 5C and 5D, respectively). Although blockade of A2AR resulted in a decrease of ADMA in the hippocampus, but not cortex of aged 3xTg (Fig. 5B). It is important to note that ADMA is a product of methylation of all type 1 PRMTs. This includes PRMT 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 [65] to suggest that other PRMT isoforms may need to be accounted for or due to other compensatory mechanisms that are currently unrealized [66].

We also investigated tight junction proteins that are important in the regulation of the blood–brain barrier, such as zonula occludin (ZO-1). Occludin is a protein that stretches across cellular membranes, forming extracellular and intracellular loops [67]. ZO-1 is a scaffold cytosolic protein that contain domains specific for protein interaction [67, 68]. It is already established that AD pathology is strongly associated with BBB leakage [69, 70]. In a study by Biron et al. [71], a link was established between the decreased expression of tight junction proteins (specifically ZO-1 and occludin), and BBB disruption in an AD mouse model. Our results suggest that cortical occludin is reduced in the young and aged 3xTg v. aged C57 (both p < 0.0001), but blockade of A2AR significantly increased its levels to aged C57-like levels (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, cortical and hippocampal ZO-1 was also reduced in aged 3xTg (p < 0.05) and blockade of A2AR restored ZO-1 protein levels similar to the C57 group (Fig. 6B and 6D). Our results suggest that cortical BBB is impaired in aged 3xTg female mice and blockade of A2AR can increase BBB-related proteins.

Improvement in brain perfusion and restoration of BBB may also restore functional outcomes, since behavioral outcome can be related to cerebral blood flow profile [72]. The open field is a good behavior test for general exploratory behavior where we can observe overall motor skills, animal’s body balance, and anxiety-like behavior [73]. It has been reported that AD patients have a tendency to decrease mobility due to deficits in balance and loss of muscle mass, as well as mental confusion regarding spatial localization, and memory impairment [74, 75]. The T-maze test is a good behavior test to evaluate short-term, and spatial working memory, through assessing the percentage of spontaneous alternation between the maze’s arms [76]. Therefore, we evaluated the animals’ baseline behavioral profile in the open field and the T-maze behavior. Rodents are curious animals and when placed in a new environment (i.e., open field apparatus), they tend to explore this area to familiarize themselves, expressing behaviors such as rearing and sniffing [77]. However, when exposed again to this environment, they lose interest due to the lack of novelty [78]. We observed this exact pattern on young 3xTg mice in the open field, where they decreased the distance walked in the apparatus seven days after the first exposure, while aged saline mice walked similar distances as if they did not recognize the environment (Fig. 7A and 7B). Regarding those animals treated with istradefylline, they walked longer distances, suggesting increase in exploratory behavior (Fig. 7C).

In the T-maze, it is expected that mice remember which arm they previously visited, so on the next trial they would visit the other one. The spontaneous alternation allows animals with hippocampal-dependent cognitive decline to score below 50%, which is the chance level score [79]. Before treatment, young 3xTg mice presented around 80% of spontaneous alternation, while aged animals presented around 50%. Interestingly, seven days after preselection was enough to decrease the percentage of spontaneous alternation of young animals by 10% and of aged saline by 12%, while blockage of A2AR in aged animals improved it by 9% (Fig. 8A and 8B). Memory improvement was also observed regarding long-term memory in the novel object recognition test, where young and aged saline 3xTg animals explored the new object significantly less than aged C57 mice and, again, blockade of A2AR made the AD animals perform as a healthy aged C57 mice (Fig. 8C).

The adenosine system plays a key role in modulation of cognitive processes. Studies with caffeine, a well described adenosine antagonist, showed that blockade of A2AR can decrease cognitive deficits in AD patients and animal models [80–83]. Moreover, others suggest that overexpression of A2AR causing cognitive impairment related to vascular dementia and AD [84, 85]. Interestingly, the specific A2AR antagonist, istradefylline, is currently approved by the FDA as a complimentary treatment to levodopa in Parkinson’s disease [86]. We observed improvement in brain blood flow, BBB integrity, reduction of AD-related proteins (APP and Tau), and improvement in cognitive tasks for short- and long-term memory, suggesting that A2AR is an important target in AD. Our studies suggest that blockade of A2AR is beneficial for brain perfusion and cognitive recovery; shown by decreasing levels of AD-related proteins as well as PRMT4, ADMA, and restoring the NO pathway. However, the molecular mechanism(s) and why this receptor is pathologically elevated in AD is not yet clear and worthy of further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We authors would like to acknowledge William Chandler Carr for behavioral testing and protein processing assistance.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MSBU, JZM, GAC, CTC, JL, DJS, LHM, and VT. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MSBU, JZM, CTC, and HWL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants 1R01AG081258-01A1 (HWL), 1RF1NS132291-01 (HWL), 1R01AG081874-01 (HWL), and the American Heart Association grants 22TPA970253 (HWL), 23POST1018945 (MU), and 23CDA1051814 (VT).

Data availability

All data used in this study will be available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth) at Houston, TX (protocol AWC-24–0006).

Consent to participate

This research did not involve human participants.

Consent to publish

All authors agreed with the content of this research and approved the publication of this work.

Competing interests

Authors MSBU, JZM, GAC, CTC, JL, DJS, LHM, and VT have no competing interests to declare. Author HWL is a consultant for Neurelis Inc, however none of the work presented was supported by Neurelis Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.2021 alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:327-406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Vina J, Lloret A. Why women have more alzheimer’s disease than men: Gender and mitochondrial toxicity of amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S527-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelros P, Stegmayr B, Terent A. Sex differences in stroke epidemiology: A systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40:1082–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dufouil C, Seshadri S, Chene G. Cardiovascular risk profile in women and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl 4):S353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glader EL, Stegmayr B, Norrving B, Terent A, Hulter-Asberg K, Wester PO, et al. Sex differences in management and outcome after stroke: A swedish national perspective. Stroke. 2003;34:1970–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nebel RA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Gallagher A, Goldstein JM, Kantarci K, et al. Understanding the impact of sex and gender in alzheimer’s disease: a call to action. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince M, Ali GC, Guerchet M, Prina AM, Albanese E, Wu YT. Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korte N, Nortley R, Attwell D. Cerebral blood flow decrease as an early pathological mechanism in alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140:793–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding B, Ling HW, Zhang Y, Huang J, Zhang H, Wang T, et al. Pattern of cerebral hyperperfusion in alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment using voxel-based analysis of 3d arterial spin-labeling imaging: Initial experience. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin BP, Nair VA, Meier TB, Xu G, Rowley HA, Carlsson CM, et al. Effects of hypoperfusion in alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(Suppl 3):123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breijyeh Z, Karaman R. Comprehensive review on alzheimer’s disease: Causes and treatment. Molecules. 2020;25:5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusano Y, Echeverry G, Miekisiak G, Kulik TB, Aronhime SN, Chen JF, et al. Role of adenosine a2 receptors in regulation of cerebral blood flow during induced hypotension. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:808–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merighi S, Battistello E, Casetta I, Gragnaniello D, Poloni TE, Medici V, et al. Upregulation of cortical a2a adenosine receptors is reflected in platelets of patients with alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;80:1105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khayat MT, Nayeem MA. The role of adenosine a(2a) receptor, cyp450s, and ppars in the regulation of vascular tone. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1720920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canas PM, Porciuncula LO, Cunha GM, Silva CG, Machado NJ, Oliveira JM, et al. Adenosine a2a receptor blockade prevents synaptotoxicity and memory dysfunction caused by beta-amyloid peptides via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14741–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, An S, Lee SJ, Kang JS. Protein arginine methyltransferases in neuromuscular function and diseases. Cells. 2022;11:364364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clemons GA, Silva ACE, Acosta CH, Udo MSB, Tesic V, Rodgers KM, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 4 modulates nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and cerebral blood flow in alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Physiol. 2024;239:e30858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, et al. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the arrive guidelines 2.0. PLOS Biology. 2020;18:3000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couto ESA, Wu CY, Clemons GA, Acosta CH, Chen CT, Possoit HE, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 8 modulates mitochondrial bioenergetics and neuroinflammation after hypoxic stress. J Neurochem. 2021;159:742–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Gallagher K, Puledda F, O’Daly O, Ryan M, Dancy L, Chowienczyk PJ, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase regulates regional brain perfusion in healthy humans. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118:1321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Harten AC, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Mielke MM, Kremers WK, Eichenlaub U, et al. Detection of alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta 1–42, p-tau, and t-tau assays. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:635–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hays CC, Zlatar ZZ, Wierenga CE. The utility of cerebral blood flow as a biomarker of preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36:167–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher RA, Miners JS, Love S. Pathological changes within the cerebral vasculature in alzheimer’s disease: new perspectives. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 2022;32:e13061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, Brettschneider J, Xie SX, Grossman M, et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the national alzheimer’s coordinating centre. Brain. 2013;136:2697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eglit GML, Weigand AJ, Nation DA, Bondi MW, Bangen KJ. Hypertension and alzheimer’s disease: Indirect effects through circle of willis atherosclerosis. Brain Commun. 2020;2:fcaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan W, Zhou GD, Balachandrasekaran A, Bhumkar AB, Boraste PB, Becker JT, et al. Cerebral blood flow predicts conversion of mild cognitive impairment into alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline: An arterial spin labeling follow-up study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neal MA. Women and the risk of alzheimer’s disease. Front Glob Womens Health. 2023;4:1324522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustavsson A, Norton N, Fast T, Frolich L, Georges J, Holzapfel D, et al. Global estimates on the number of persons across the alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:658–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanyu H, Shimizu S, Tanaka Y, Takasaki M, Koizumi K, Abe K. Differences in regional cerebral blood flow patterns in male versus female patients with alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1199–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuda H. Role of neuroimaging in alzheimer’s disease, with emphasis on brain perfusion spect. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang YK, Min B, Eom J, Park JS. Different phases of aging in mouse old skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY). 2022;14:143–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koebele SV, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Modeling menopause: The utility of rodents in translational behavioral endocrinology research. Maturitas. 2016;87:5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, et al. Triple-transgenic model of alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: Intracellular abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal abeta causes the onset of early alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stover KR, Campbell MA, Van Winssen CM, Brown RE. Early detection of cognitive deficits in the 3xtg-ad mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2015;289:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Javonillo DI, Tran KM, Phan J, Hingco E, Kramár EA, da Cunha C, et al. Systematic phenotyping and characterization of the 3xtg-ad mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:785276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shigetomi E, Sakai K, Koizumi S. Extracellular atp/adenosine dynamics in the brain and its role in health and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1343653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji Q, Yang Y, Xiong Y, Zhang YJ, Jiang J, Zhou LP, et al. Blockade of adenosine a(2a) receptors reverses early spatial memory defects in the app/ps1 mouse model of alzheimer’s disease by promoting synaptic plasticity of adult-born granule cells. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ij AP, Jacobson KA, Muller CE, Cronstein BN, Cunha RA. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. Cxii: Adenosine receptors: a further update. Pharmacol Rev. 2022;74:340–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes LV, Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA. Cross talk between a(1) and a(2a) adenosine receptors in the hippocampus and cortex of young adult and old rats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costenla AR, Diogenes MJ, Canas PM, Rodrigues RJ, Nogueira C, Maroco J, et al. Enhanced role of adenosine a(2a) receptors in the modulation of ltp in the rat hippocampus upon ageing. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canas PM, Duarte JM, Rodrigues RJ, Kofalvi A, Cunha RA. Modification upon aging of the density of presynaptic modulation systems in the hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1877–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viana da Silva S, Haberl MG, Zhang P, Bethge P, Lemos C, Goncalves N, et al. Early synaptic deficits in the app/ps1 mouse model of alzheimer’s disease involve neuronal adenosine a2a receptors. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurent C, Burnouf S, Ferry B, Batalha VL, Coelho JE, Baqi Y, et al. A2a adenosine receptor deletion is protective in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goncalves FQ, Lopes JP, Silva HB, Lemos C, Silva AC, Goncalves N, et al. Synaptic and memory dysfunction in a beta-amyloid model of early alzheimer’s disease depends on increased formation of atp-derived extracellular adenosine. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;132:104570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michael SK, Surks HK, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Blanton R, Jamnongjit M, et al. High blood pressure arising from a defect in vascular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6702–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Touyz RM, Alves-Lopes R, Rios FJ, Camargo LL, Anagnostopoulou A, Arner A, et al. Vascular smooth muscle contraction in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:529–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S, Tang C, Liu Y, Border JJ, Roman RJ, Fan F. Impact of impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation on cognitive impairment. Front Aging. 2022;3:1077302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang X, Tang C, Zhang H, Border JJ, Liu Y, Shin SM, et al. Longitudinal characterization of cerebral hemodynamics in the tgf344-ad rat model of alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience. 2023;45:1471–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cau SB, Carneiro FS, Tostes RC. Differential modulation of nitric oxide synthases in aging: therapeutic opportunities. Front Physiol. 2012;3:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cernadas MR, Sanchez de Miguel L, Garcia-Duran M, Gonzalez-Fernandez F, Millas I, Monton M, et al. Expression of constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthases in the vascular wall of young and aging rats. Circ Res. 1998;83:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou TC, Yen MH, Li CY, Ding YA. Alterations of nitric oxide synthase expression with aging and hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:643–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith AR, Visioli F, Frei B, Hagen TM. Age-related changes in endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and nitric oxide dependent vasodilation: Evidence for a novel mechanism involving sphingomyelinase and ceramide-activated phosphatase 2a. Aging Cell. 2006;5:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chou CH, Hsu KC, Lin TE, Yang CR. Anti-inflammatory and tau phosphorylation-inhibitory effects of eupatin. Molecules. 2020;25:5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang WY, Tan MS, Yu JT, Tan L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suschek CV, Schnorr O, Kolb-Bachofen V. The role of inos in chronic inflammatory processes in vivo: Is it damage-promoting, protective, or active at all? Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:763–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lind M, Hayes A, Caprnda M, Petrovic D, Rodrigo L, Kruzliak P, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Good or bad?. Biomed Pharmacother= Biomed Pharmacother 2017;93:370–375. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Constantinides C, Mean R, Janssen BJ. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the cardiovascular function of the c57bl/6 mouse. ILAR J. 2011;52:e21-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loeb AL, Raj NR, Longnecker DE. Cerebellar nitric oxide is increased during isoflurane anesthesia compared to halothane anesthesia: A microdialysis study in rats. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park KW, Dai HB, Lowenstein E, Stambler A, Sellke FW. Effect of isoflurane on the beta-adrenergic and endothelium-dependent relaxation of pig cerebral microvessels after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;7:168–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drummond E, Wisniewski T. Alzheimer’s disease: Experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:155–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rajmohan R, Reddy PH. Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tau accumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of alzheimer’s disease neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:975–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang F, Zhong R, Li S, Fu Z, Cheng C, Cai H, et al. Acute hypoxia induced an imbalanced m1/m2 activation of microglia through nf-kappab signaling in alzheimer’s disease mice and wild-type littermates. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Justo AFO, Suemoto CK. The modulation of neuroinflammation by inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Cell Commun Signal. 2022;16:155–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Y, Bedford MT. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Couto ESA, Wu CY, Citadin CT, Clemons GA, Possoit HE, Grames MS, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferases in cardiovascular and neuronal function. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:1716–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuo WT, Odenwald MA, Turner JR, Zuo L. Tight junction proteins occludin and zo-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2022;1514:21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fanning AS, Anderson JM. Zonula occludens-1 and -2 are cytosolic scaffolds that regulate the assembly of cellular junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nehra G, Bauer B, Hartz AMS. Blood-brain barrier leakage in alzheimer’s disease: From discovery to clinical relevance. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;234:108119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sousa JA, Bernardes C, Bernardo-Castro S, Lino M, Albino I, Ferreira L, et al. Reconsidering the role of blood-brain barrier in alzheimer’s disease: From delivery to target. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1102809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Biron KE, Dickstein DL, Gopaul R, Jefferies WA. Amyloid triggers extensive cerebral angiogenesis causing blood brain barrier permeability and hypervascularity in alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kondashevskaya MV, Downey HF, Tseilikman VE, Alexandrin VV, Artem’yeva KA, Aleksankina VV, et al. Cerebral blood flow in predator stress-resilient and -susceptible rats and mechanisms of resilience. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:14729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seibenhener ML, Wooten MC. Use of the open field maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp. 2015;38:e52434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gras LZ, Kanaan SF, McDowd JM, Colgrove YM, Burns J, Pohl PS. Balance and gait of adults with very mild alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zenaro E, Piacentino G, Constantin G. The blood-brain barrier in alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;107:41–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.d’Isa R, Comi G, Leocani L. Apparatus design and behavioural testing protocol for the evaluation of spatial working memory in mice through the spontaneous alternation t-maze. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson SM, Berkowitz LE, Clark BJ. Behavioral and neural subsystems of rodent exploration. Learn Motiv. 2018;61:3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leussis MP, Bolivar VJ. Habituation in rodents: A review of behavior, neurobiology, and genetics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1045–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deacon RM, Rawlins JN. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eskelinen MH, Ngandu T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: A population-based caide study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cao C, Loewenstein DA, Lin X, Zhang C, Wang L, Duara R, et al. High blood caffeine levels in mci linked to lack of progression to dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:559–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Laurent C, Eddarkaoui S, Derisbourg M, Leboucher A, Demeyer D, Carrier S, et al. Beneficial effects of caffeine in a transgenic model of alzheimer’s disease-like tau pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pagnussat N, Almeida AS, Marques DM, Nunes F, Chenet GC, Botton PH, et al. Adenosine a(2a) receptors are necessary and sufficient to trigger memory impairment in adult mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:3831–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gessi S, Poloni TE, Negro G, Varani K, Pasquini S, Vincenzi F, et al. A(2a) adenosine receptor as a potential biomarker and a possible therapeutic target in alzheimer’s disease. Cells. 2021;10:2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Launay A, Nebie O, VijayaShankara J, Lebouvier T, Buee L, Faivre E, et al. The role of adenosine a(2a) receptors in alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. Neuropharmacology. 2023;226:109379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen JF, Cunha RA. The belated us fda approval of the adenosine a(2a) receptor antagonist istradefylline for treatment of parkinson’s disease. Purinergic Signal. 2020;16:167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study will be available upon reasonable request.