Abstract

Background

Management of patients with food allergies is complex, especially in cases of patients with multiple and potentially severe food allergies. Although international guidelines exist for food allergy management, the role of the allergist in the decision-making process is key.

Objective

Our aim was to investigate the management patterns and educational needs of practicing allergists treating patients with food allergies.

Methods

An online survey was e-mailed to United States–based practicing allergists (N = 2833) in November-December 2021. The allergists were screened for managing 1 or more patients (including ≥25% pediatric patients) with food allergies per month. The allergists responded to questions regarding food allergy management in response to 2 hypothetical pediatric case studies, their familiarity with available guidelines and emerging treatments, and their future educational preferences. A descriptive analysis of outcomes was conducted.

Results

A total of 125 responding allergists (4.4%) met the eligibility criteria and completed the survey. The allergists prioritized written exposure action plans, patient-caregiver communication, prevention of serious reactions, and consideration of both food allergy severity and allergic comorbidities in the management of patients with food allergies. With regard to recommending biologics in the future, the allergists identified patient history of anaphylaxis and hospitalizations, food allergy severity, and allergic comorbidities as all being important factors to consider when deciding on appropriate treatment options. The allergists noted their ongoing educational needs, especially for current and emerging treatments for food allergies.

Conclusion

With the treatment landscape for food allergies evolving rapidly, the decision-making priorities and continuing educational needs of allergists will be important in optimizing the management of patients with food allergies.

Key words: Allergists, anaphylaxis, children, education, medical, continuing, food allergy, food hypersensitivity, pediatric

Management of patients with food allergies is complex because of the multiple factors that need to be considered, including allergen type and severity of food allergies, clinical symptoms, challenges with diagnosis, age, comorbidities, allergen avoidance and nutritional requirements, psychosocial impact, and social determinants of health.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Many international guidelines on food allergy management are available, offering evidence-based recommendations for a broad range of health care professionals.7, 8, 9, 10 Allergists are key in the decision-making process for determining an optimal management strategy for patients with food allergies, especially for patients with multiple and potentially severe food allergies.

Allergists are instrumental in educating patients, caregivers, and other key stakeholders in best practices for managing food allergies, both in the home and in the community, by helping to prevent severe reactions (including anaphylaxis) and monitoring food intake and avoidance.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Previous studies have shown that pediatric patients seen by allergists were more likely than those seen by pediatricians to have had diagnostic testing and an epinephrine prescription16 and also that allergist care of patients with food allergies (compared to those without allergist care) may be linked to lower health care costs,17 suggesting that allergists play a key role in optimal management of patients with food allergies.

Because of the multifactorial nature of food allergies, allergists may face challenges in decision making for their patients with food allergies. We evaluated the management patterns and educational needs of allergists who care for patients with food allergies, using responses from a nationwide survey of United States-based practicing allergists regarding 2 hypothetical pediatric case studies.

Methods

The survey was developed by CE Outcomes, LLC, in collaboration with a clinical expert, and it was pilot-tested and reviewed before launch. The survey was designed to assess management patterns of practicing allergists treating patients with food allergies and determine their educational needs related to management of food allergies. Institutional review board approval was not sought owing to the nature of the survey.

The online survey (provided in the Supplementary Methods in the Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org) was e-mailed to practicing allergists (N = 2833) across the United States in November-December 2021. It should be noted that as the survey was conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic, it included a question regarding whether management of pediatric patients has changed; in response, the allergists noted an increase in use of telemedicine and a decrease in oral food challenge (for details, see the Supplementary Methods). Allergists were identified by degree (MD, DO, MD/PhD, or DO/PhD) and allergy/immunology specialty. Contact information was obtained through either a purchased list or a database of physicians who opted in to receive surveys. After survey entry, the allergists were screened for the following eligibility criteria: managing at least 1 patient with food allergy per month and having pediatric patients (patients younger than 18 years) account for at least 25% of their patients. Only those meeting these 2 criteria were invited to complete the survey. The allergists were asked questions on various topics related to the management of 2 hypothetical pediatric case studies (a patient with a new food allergy [Fig 1, A] and a patient with known food allergies [Fig 1, B]), their general familiarity with available guidelines and emerging treatments (at the time of the survey), and their future educational preferences. The survey closed and responses were collated on February 1, 2022. A descriptive analysis of outcomes was conducted; no formal statistical hypothesis testing was performed. For survey questions in which the physicians were asked to choose from responses of “not at all,” “slightly,” “moderately,” “very,” or “extremely” (see the Supplementary Methods), we have combined the responses “very” and “extremely.”

Fig 1.

The case studies of pediatric patients with food allergies. The allergists were presented with 2 case studies: the case of a 3-year-old male patient with a new food allergy (A) and the case of a 12-year-old female patient with known food allergies (B).

Results

The survey was e-mailed to practicing allergists (N = 2833) across the United States, of whom 216 (7.6%) entered the survey. A total of 125 (4.4%) allergists met the eligibility criteria and completed the survey. The responding allergists were located largely in suburban (62%) or urban (35%) areas, most (81%) practiced in a community (nonacademic) setting, and the majority (89%) had at least 10 years in practice, with a median of 22 years in practice. The responding allergists reported managing a median of 60 patients with food allergies per month, of whom a median of 50% were pediatric patients.

Case 1: A pediatric patient with a new food allergy

The allergists were presented with a hypothetical case study of a 3-year-old male patient without a previous history of food allergy who was referred after an episode of urticaria, tongue swelling, and difficulty breathing following peanut butter ingestion (Fig 1, A). The patient was diagnosed with a peanut allergy and prescribed an epinephrine autoinjector. The allergists responded to questions about the management of this patient.

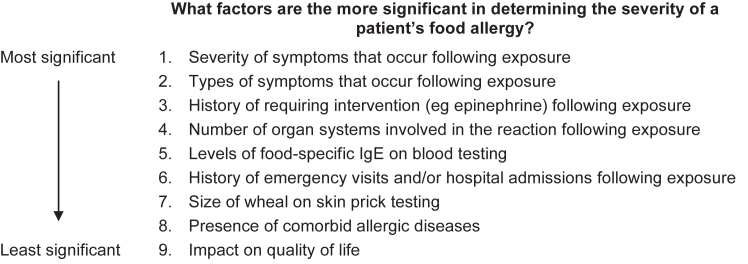

Most of the allergists (87%) stated that they would prepare a written exposure action plan for the patient and caregiver as part of the management strategy (also referred to as an allergy and anaphylaxis emergency plan). When providing initial counseling to the patient and caregiver, nearly all of the allergists (96%) would discuss correct use of an epinephrine autoinjector. Other aspects of patient care that may be discussed included impact on quality of life and possible treatments, including oral immunotherapy (OIT) and investigational biologic treatments (Fig 2). Only 40% of the allergists responded that they would rate the severity of food allergy in this patient. The factors that the allergists considered most significant in determining the severity of a patient’s food allergy were the severity of symptoms and types of symptoms occurring subsequent to allergen exposure (Fig 3).

Fig 2.

Initial counseling provided to a pediatric patient with a new food allergy and the patient’s caregiver (case 1). The allergists were asked how likely (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all) they were to discuss each aspect of patient care with this patient and the patient’s caregiver. aThe response less likely includes responses of moderately likely, slightly likely, and not at all likely.

Fig 3.

Factors determining severity of food allergy in a pediatric patient with a new food allergy (case 1). The allergists were asked whether they would rate severity of food allergy in this patient. If they answered yes, they were asked to select and rank 4 of the 9 factors provided, with 1 being the most significant and 4 being the least significant.

The most significant factors identified by the allergists as affecting effective management of pediatric patients with food allergies were the widespread presence of causative foods (40% of allergists) and diet modification and/or procurement of allergen-free foods (34%). However, few of the allergists (13%) would provide a referral to a dietitian for this patient, and this did not change if the patient was diagnosed with additional food allergies after testing (55% of the allergists would request additional testing at the time of initial diagnosis).

After 2 years of regular follow-ups, the patient was reported to have no additional peanut reactions, and a smaller wheal size was noted on skin prick testing (Fig 1, A). At that time, almost half of the responding allergists (46%) would offer a supervised oral food challenge to peanuts for this patient. The majority of the allergists (60%) estimated a low (≤30%) likelihood for accidental peanut exposure in the patient within the next 5 years. Although the majority of the allergists (77%) agreed that the patient’s peanut allergy was unlikely to resolve over time, 85% of them would still plan to evaluate this patient for resolution of food allergies in the future.

Case 2: A pediatric patient with known food allergies

The allergists were presented with a hypothetical case study of a 12-year-old female patient previously diagnosed with multiple food allergies (peanut and tree nut), environmental allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis (Fig 1, B). The patient reported poor control of asthma and atopic dermatitis despite treatment with inhaled and topical steroids, respectively. Within the past 2 years, this patient had 1 accidental exposure to peanuts that required administration of an epinephrine autoinjector dose. The allergists were also presented with a hypothetical future scenario for this patient in which biologics would be approved for treatment of food allergies in pediatric patients (note that no biologics were approved for food allergies at the time of the survey). The allergists responded to questions about the management of this patient.

Overall, the top management goals of the allergists in treating this pediatric patient were to prevent serious allergic reactions, maximize quality of life, and provide effective education on allergen avoidance. Increasing food tolerance and allowing for a normal diet were lower priorities. When considering OIT as part of the management strategy for this patient, only 16% of the allergists would recommend commercial peanut OIT, and only 9% of them would recommend unregulated peanut OIT at this time. However, the majority of the allergists (64%) indicated that the presence of comorbidities would affect the management of food allergies, with some allergic comorbidities (eg, asthma, atopic dermatitis, multiple food allergies, and chronic urticaria) more likely to prompt the allergists to recommend biologic treatments if they were available.

With regard to recommending biologics in the future, the allergists stated that the most important treatment-related factors would be efficacy in reducing anaphylaxis and hospitalizations, drug safety and tolerability, cost and insurance coverage, and efficacy in controlling comorbid allergic conditions (Fig 4, A). The most important patient-related factors would be history of anaphylactic reactions and/or emergency department visits in connection with allergen exposures and severity of food allergies (Fig 4, B). More than half (56%) of the allergists would recommend at-home self-administration with a prefilled syringe if the biologic was available as a monthly injection.

Fig 4.

Biologics as potential treatments for a pediatric patient with known food allergies (case 2). The allergists were asked to consider a scenario in which biologics were approved for the treatment of food allergies in pediatric patients and state how significant (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all) each treatment-related factor was in determining whether to recommend treatment with biologics (A) and how significant each patient-related factor was in determining whether to treat a patient’s food allergies with biologics (B). aThe response less significant includes the responses moderately significant, slightly significant, and not at all significant.

Education

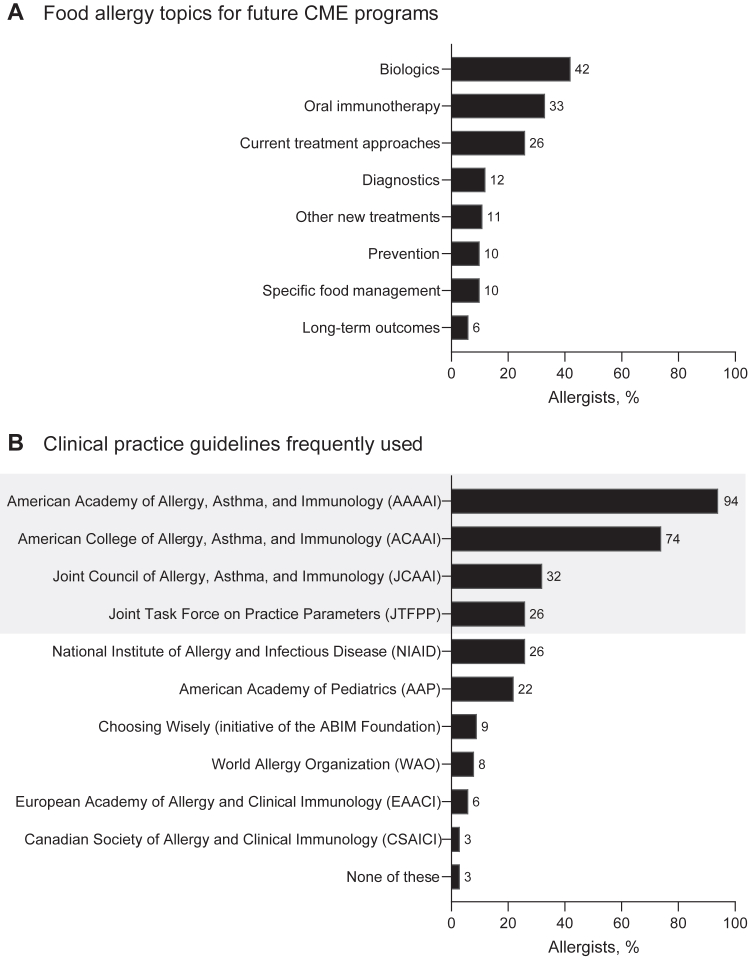

Over the past year, most of the allergists (86%) had participated in continuing medical education (CME) covering food allergies; 87% of them indicated that this education was likely to continue in the year after the survey. In future CME programs, the allergists would most like to learn about biologics (42%), OIT (33%), and current treatment options (26%) (Fig 5, A), mostly through online text and/or journal articles (63%) and live in-person presentations (60%). The allergists mostly preferred to learn on their own (62%) versus in group settings for CME.

Fig 5.

Food allergy education and guideline use. A, Food allergy topics for future CME programs. The allergists were asked which topics (list 1 or list 2) they would be most interested in learning about in future CME programs. B, Clinical practice guidelines frequently used by allergists to manage pediatric patients with food allergies. The allergists were asked to select all responses that apply from a list of guidelines that they find useful or, alternatively, indicate “none of these.” Gray box indicates organizations and guidelines affiliated with the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (JTFPP), which was formed to develop guidelines for the diagnosis and management of allergic and immunologic diseases.18ABIM, American Board of Internal Medicine.

The most frequently used clinical practice guidelines among the allergists in this United States-based study were those accessed from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (94% of the allergists) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (74% of the allergists) (Fig 5, B). In addition, most of the allergists (79%) would provide or recommend educational materials for pediatric patients and their caregivers (in response to case 1). Most of the allergists (61%) would use materials available from Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), which was created as the result of a merger between the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network and Food Allergy Initiative, or from American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (10% of the allergists).19,20

Discussion

This study highlights the complex decisions and multitude of considerations that allergists face when managing patients with food allergies. In response to the 2 pediatric cases, the responding allergists highlighted written exposure action plans, patient-caregiver communication, prevention of serious allergic reactions, and consideration of both food allergy severity and allergic comorbidities as key priorities of food allergy management. In addition, the allergists noted that the most important factors influencing a theoretic decision regarding treatment with biologics included patient history of anaphylaxis and hospitalizations, food allergy severity, and allergic comorbidities (note that no biologics were approved for food allergies at the time of the survey). In addition, this study emphasizes the ongoing educational needs of practicing allergists. With the treatment landscape for food allergies evolving rapidly, including the recent approval of the first biologic for food allergy,21,22 the need for up-to-date, evidence-based education for allergists is a priority.

Prevention of serious allergic reactions and anaphylaxis in patients was generally considered the top priority of allergists in our survey and in previous work,11,23 which is largely in line with international guidelines7,24 and reviews on managing food allergies.25,26 Although assessing food allergy severity was not considered a priority by about half of the allergists in our survey, there is now an international system for definition and classification of severity (developed by the World Allergy Organization, the system is called Definition of Food Allergy Severity [DEFASE] and is currently pending validation),4 which may aid categorization of disease severity during patient evaluation. Another consideration for allergists is the impact of allergic comorbidities, particularly asthma and atopic dermatitis, which may increase the burden in patients and complicate management and treatment3,27 (eg, uncontrolled asthma is contraindicated for OIT28). In patients with comorbid asthma and food allergies, lower quality of life29 and poorer prognosis for food allergies30 may add to the management burden in these patients. In addition, the allergists in this survey prioritized patient-caregiver communication and education (eg, by developing a written exposure action plan, offering counseling on correct epinephrine use, and providing educational resources). This is an important component of shared decision making, which is being increasingly utilized in food allergy management.31, 32, 33

In this survey, the allergists indicated a need for further education about treatment options for food allergies. No biologics were approved for food allergies at the time of the survey; however, in February 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab for treatment of IgE-mediated food allergies,21,22 and this approval may affect the treatment landscape. As was recently discussed by Sampson et al,34 identifying the most suitable patients for omalizumab treatment is an important point to consider, as it will assist allergists in the clinic. Factors contributing to the identification of suitable patients may include presence of comorbid asthma (which may also be treated with omalizumab22,35), patient preference for nonoral therapies,35 and patient preference for self-administration (which many allergists would recommend and is available for omalizumab, with many benefits for appropriate patients36).

The main limitation of our study is a possible selection bias, with approximately 8% of the allergists responding to the e-mail and less than 5% of them completing the survey. Therefore, the results may not be representative of all allergists in the United States. In addition, the allergists responded on the basis of 2 specific hypothetical pediatric case studies, so these findings may not be generalizable for all patients with food allergies, and not all patients would be considered for biologics (any treatment should be FDA-approved). No formal statistical hypothesis testing was performed, thus limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Further, this survey has not been validated, although it was developed in collaboration with a clinical expert and pilot-tested with allergists practicing in the United States.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the management priorities of United States–based allergists. Given the complexities of food allergies, patient-allergist conversations and shared decision-making approaches may be valuable in ensuring personalized treatment for patients. Our study was conducted before recent changes in the landscape of biologics for treatment of food allergies,20,21 and this only strengthens the sentiment that CME on treatment options and best practice will help allergists optimize management of patients with food allergies.

Clinical implications.

Given the complex decisions and multitude of considerations that allergists face when managing patients with food allergies, patient-allergist conversations and shared decision-making approaches may be valuable in optimizing treatment.

Disclosure Statement

Conducted by CE Outcomes, LLC, with support from Genentech, Inc, a member of the Roche Group.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: A. Anagnostou reports receiving institutional funding from Aimmune, Mike Hogg Foundation and Novartis; serving as an advisory board member for DBV Technologies and Novartis; receiving consultation and/or speaker fees from Adelphi, Aimmune, ALK, and Genentech, Inc. M. Greenhawt reports being a consultant for Aquestive; serving as an advisory board member for Aquestive, ALK-Abelló, Allergy Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bryn Pharma, DBV Technologies, Novartis, Nutricia, and Prota; serving as an unpaid member of the scientific advisory council for the National Peanut Board; sitting on the medical advisory board of the International Food Protein–Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Association; serving as a member of the Brighton Collaboration Criteria Vaccine Anaphylaxis 2.0 working group; acting as senior associate editor for the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and serving as a member of the Joint Task Force on Allergy Practice Parameters. J. A. Lieberman reports serving as an advisory board member for Aquestive; sitting on the data and safety and monitoring board and/or adjudication committee for AbbVie and Siolta; acting as a consultant for ALK, Bayer, DBV, and Novartis; and serving as a board member for the American Board of Allergy and Immunology and Joint Task Force for Practice Parameters. C. E. Ciaccio reports providing research support from the Duchossois Foundation, Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE), National Institutes of Health, and Paul and Mary Yovovich; and serving as an advisory board member for Clostrabio, Genentech, Inc, and Siolta. S. B. Sindher reports receiving grants from Aimmune, Consortium for Food Allergy Research (CoFAR), DBV, the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Novartis, Regeneron, and Sanofi and serving as an advisory board member for Genentech, Inc. B. Creasy, K. Baran, and S. Gupta are employees of Genentech, Inc, and stockholders in Roche. A. Nowak-Wegrzyn reports receiving research support from Astellas, Danone, DBV, the NIAID, and Nestlé; receiving consultancy fees from Gerber Institute, Novartis, and Regeneron; acting as deputy editor for Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and serving as chair of the medical advisory board of the International Food Protein–Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Association.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Greg Salinas, PhD, Morgan Leafe, MD, and Samantha Scalici, MBA, of CE Outcomes, LLC, for conducting the survey and analyzing the survey data. Medical writing assistance was provided by Nilisha Fernando, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group, and funded by Genentech, Inc, a member of the Roche Group.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Waserman S., Bégin P., Watson W. IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:55. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0284-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J. Management of the patient with multiple food allergies. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010;10:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0116-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J., Sampson H.A., Fiocchi A., Sicherer S., WAO . In: Asthma: comorbidities, coexisting conditions, and differential diagnosis. Lockey R.F., Ledford D.K., editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2014. Atopic dermatitis, food allergy, and anaphylaxis: comorbid and coexisting; pp. 455–466. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arasi S., Nurmatov U., Dunn-Galvin A., Roberts G., Turner P.J., Shinder S.B., et al. WAO consensus on DEfinition of Food Allergy SEverity (DEFASE) World Allergy Organ J. 2023;16 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2023.100753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren C., Dyer A., Lombard L., Dunn-Galvin A., Gupta R. The psychosocial burden of food allergy among adults: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2452–2460.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren C., Bartell T., Nimmagadda S.R., Bilaver L.A., Koplin J., Gupta R.S. Socioeconomic determinants of food allergy burden: a clinical introduction. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce J.A., Assa'ad A., Burks A.W., Jones S.M., Sampson H.A., Wood R.A., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halken S., Muraro A., de Silva D., Khaleva E., Angier E., Arasi S., et al. EAACI guideline: preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32:843–858. doi: 10.1111/pai.13496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraro A., de Silva D., Halken S., Worm M., Khaleva E., Arasi S., et al. Managing food allergy: GA2LEN guideline 2022. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampson H.A., Aceves S., Bock S.A., James J., Jones S., Lang D., et al. Food allergy: a practice parameter update-2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1016–1025.e43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J., Bingemann T., Russell A.F., Young M.C., Sicherer S.H. The allergist's role in anaphylaxis and food allergy management in the school and childcare setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Academies of Sciences . In: Finding a path to safety in food allergy: assessment of the global burden, causes, prevention, management, and public policy. Oria M.P., Stallings V.A., editors. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2016. Engineering, and Medicine. Management in the health care setting. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young M.C., Muñoz-Furlong A., Sicherer S.H. Management of food allergies in schools: a perspective for allergists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.004. 82.e1-4; quiz 83-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venter C., Meyer R., Bauer M., Bird J.A., Fleischer D.M., Nowak-Wegrzyn A., et al. Identifying children at risk of growth and nutrient deficiencies in the food allergy clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2024.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leone L., Mazzocchi A., Maffeis L., De Cosmi V., Agostoni C. Nutritional management of food allergies: prevention and treatment. Front Allergy. 2022;3 doi: 10.3389/falgy.2022.1083669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manious M., Atalla J., Erwin E., Stukus D., Mikhail I. Differences in management of peanut allergy between allergists and pediatricians. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124:512–513. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenhawt M., Abrams E.M., Chalil J.M., Tran O., Green T.D., Shaker M.S. The impact of allergy specialty care on health care utilization among peanut allergy children in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:3276–3283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welcome to the JTFPP Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. https://www.allergyparameters.org/ Available at:

- 19.FARE: Food Allergy Research & Education. https://www.foodallergy.org/ Available at: Accessed May 16, 2024.

- 20.Tools for the public American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. https://www.aaaai.org/tools-for-the-public Available at: Accessed May 16, 2024.

- 21.Wood R.A., Togias A., Sicherer S.H., Shreffler W.G., Kim E.H., Jones S.M., et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of multiple food allergies. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:889–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2312382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xolair (omalizumab) Genentech, Inc; 2024. Prescribing information. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung A.S.Y., Pawankar R., Pacharn P., Wong L.S.Y., Le Pham D., Chan G., et al. Perspectives and gaps in the management of food allergy and anaphylaxis in the Asia-Pacific Region. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob. 2024;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jacig.2023.100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muraro A., Werfel T., Hoffmann-Sommergruber K., Roberts G., Beyer K., Bindslev-Jensen C., et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy. 2014;69:1008–1025. doi: 10.1111/all.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cafarotti A., Giovannini M., Begìn P., Brough H.A., Arasi S. Management of IgE-mediated food allergy in the 21st century. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023;53:25–38. doi: 10.1111/cea.14241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowling P.J. Food allergy: practical considerations for primary care. Mo Med. 2011;108:344–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warren C., Gupta R., Seetasith A., Schuldt R., Wang R., Iqbal A., et al. The clinical burden of food allergies: insights from the Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) patient registry. World Allergy Organ J. 2024;17 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2024.100889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bégin P., Chan E.S., Kim H., Wagner M., Cellier M.S., Favron-Godbout C., et al. CSACI guidelines for the ethical, evidence-based and patient-oriented clinical practice of oral immunotherapy in IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2020;16:20. doi: 10.1186/s13223-020-0413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson J., Borres M.P., Nordvall L., Lidholm J., Janson C., Alving K., et al. Perceived food hypersensitivity relates to poor asthma control and quality of life in young non-atopic asthmatics. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiocchi A., Terracciano L., Bouygue G.R., Veglia F., Sarratud T., Martelli A., et al. Incremental prognostic factors associated with cow's milk allergy outcomes in infant and child referrals: the Milan Cow's Milk Allergy Cohort study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:166–173. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anagnostou A. Shared decision-making in food allergy: navigating an exciting era. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenhawt M. Shared decision-making in the care of a patient with food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anagnostou A., Hourihane J.O.B., Greenhawt M. The role of shared decision making in pediatric food allergy management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sampson H.A., Bird J.A., Fleischer D., Shreffler W.G., Spergel J.M. Who are the potential patients for omalizumab for food allergy? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:569–571. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2024.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casale T.B., Fiocchi A., Greenhawt M. A practical guide for implementing omalizumab therapy for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153:1510–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy K.R., Winders T., Smith B., Millette L., Chipps B.E. Identifying patients for self-administration of omalizumab. Adv Ther. 2023;40:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02308-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.