Abstract

Background

To identify the prognosis of Japanese patients with collecting duct carcinoma (CDC).

Methods

We used a hospital-based cancer registry data in Japan to extract CDC cases that were diagnosed in 2013, histologically confirmed, and determined the first course of treatment. We further investigated treatment modalities and estimated overall survival (OS) by the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

A total of 61 CDC patients were identified. The 5-year OS rate for all CDC patients who were diagnosed in Japan during 2013 was 23.6% (95% CI: 15.0–37.4), with a median OS of 14 months (95% CI: 12–24). The 5-year OS rate for CDC patients at stages I, III, and IV were 53.0% (95% CI: 29.9–94.0), 35.7% (95% CI: 19.8–64.4), and 3.4% (95% CI: 0.5–23.7), respectively. Noteworthy, the 1-year OS for stage IV patients was 27.6% (95% CI: 0.5–23.7) and the median OS was only 5 months (95% CI: 4–12). We further examined the OS for advanced disease according to treatment modalities. The median OS of patients who undertook chemotherapy alone was significantly shorter than patients who undertook surgery alone for advanced disease (4 months [95% CI: 4-NA] vs. 15 months [95% CI: 13–68]; p < 0.001) and surgery-only patients had a similar median OS as surgery-plus-chemotherapy patients (19 months [95% CI: 13-NA]; p < 0.001). Moreover, a multivariable analysis for the OS in advanced disease revealed that surgery-plus-chemotherapy patients had significantly more favorable prognoses (HR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.07–0.57).

Conclusions

Japanese CDC patients face poor prognoses similar to Western countries, especially in advanced cases that receive only chemotherapy. Surgery appears necessary for advanced disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-13572-8.

Keywords: Collecting duct carcinoma, Renal cell carcinoma, Hospital-based cancer registry, Overall survival

Background

Collecting duct carcinoma (CDC) is a rare and aggressive type of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) derived from a malignant epithelial tumor in the renal collecting ducts of Bellini [1]. Although the incidence is reported to be less than 2% of all RCC [2–4], CDC patients are frequently symptomatic with advanced staging and poor prognoses at the time of diagnosis [1]. This often late-stage diagnosis makes first treatment choice crucial.

Large cohort studies of CDC patients in America using the National Cancer Database (NCD) or the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database [3, 5] have been reported. However, for Japan, the low incidence renders similarly large-scale reports on CDC that can be used for treatment determination scarce. While Tokuda et al. previously reported clinical characteristics of 81 patients with CDC in Japan using multi-institutional survey data between 2001 and 2003, [6] to our best knowledge, this is the only CDC cohort report from Japan.

In the present study, we evaluated the prognostic of CDC patients in Japan using real-world, large-cohort Hospital-Based Cancer Registry (HBCR) data from 2013 to report characteristics of CDC patients and determine overall survival based on initial treatment methods.

Methods

Data sources

HBCR data consist of registered, newly diagnosed cancer patients in designated cancer care hospitals (DCCHs: assigned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as the primary representatives in their respective regions) and other core cancer care hospitals. Covering more than 70% of newly registered cancer patients in Japan, analyses of these data are published annually as the National Cancer Statistics Report [7–9]. Specialist cancer registrars at each hospital record data from diagnosed cancer patients based on standardized criteria, including demographics, tumor characteristics, and the first course of treatment. Staging information for this purpose is based on the 7th UICC TNM classification. In our study, we used the 2013 cohort data with patient survival information for 5 years after diagnosis and these data were obtained from hospitals that had a > 90% follow-up rate for all cancer patients.

Data extraction

We extracted eligible cases from the HBCR data using the following inclusion criteria: (i) newly diagnosed, primary malignant tumors of the kidney (C64.9) and renal pelvis (65.9) in 2013; (ii) determined the first course of treatment at a DCCH or other core cancer care hospital after the confirmation of diagnosis; and (iii) had histologically confirmed CDC (8319) with International Classification of Disease for Oncology 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) histology codes. We excluded any patients under 20 years of age because some pediatric DCCHs were not part of the database. We also excluded cases with unknown clinical (cStage) and pathological staging (pStage). For this study, pStage was applied when available while cStage was applied when pStage was unavailable; this was defined as “summary stage,” referred to as simply “stage” in the present study [8].

Statistical analyses

The overall survival (OS) rate was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between groups by the log-rank test. The significance of the three groups was assessed by the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. Multivariable analysis for the OS was performed by Cox regression analysis for age group, gender, stage, and treatment modalities as covariables. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. R (4.3.0 for Windows®, R Foundation [10]) was used for analysis.

Ethical considerations

The HBCR database contains only non-personally identifiable data in consideration of individual privacy protection; dates of birth are rounded to the nearest year and month and only prefecture of residence is available. The research protocol and data handling were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tsukuba Hospital (R03-228).

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 64 cases that were registered with both C.64.9/65.9 and 8329 ICD-O-3 codes, a total of 61 patients with CDC were identified from the HBCR data (according to eligibility criteria) (Fig. 1). Patient characteristics in the present cohort are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 69 years (range 31–85 years) and CDC patients from this cohort were more commonly male (male vs female; 68.8% vs 31.2%). Advanced tumor stage (T3-4), regional lymph node invasion, and distant metastases were present in 29 (47.5%), 31 (50.8%), and 24 (39.3%) patients, respectively. While localized CDC (stages I and II) was in the minority (18%), the proportions of stage III and IV disease were higher, at 34.4% and 47.5%.

Fig. 1.

Eligibility of patients with CDC

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with CDC

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 69 (31–85) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 42 (68.9%) |

| Female | 19 (31.1%) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| I | 11 (18.0%) |

| II | 0 (0.0%) |

| III | 21 (34.4%) |

| IV | 29 (47.5%) |

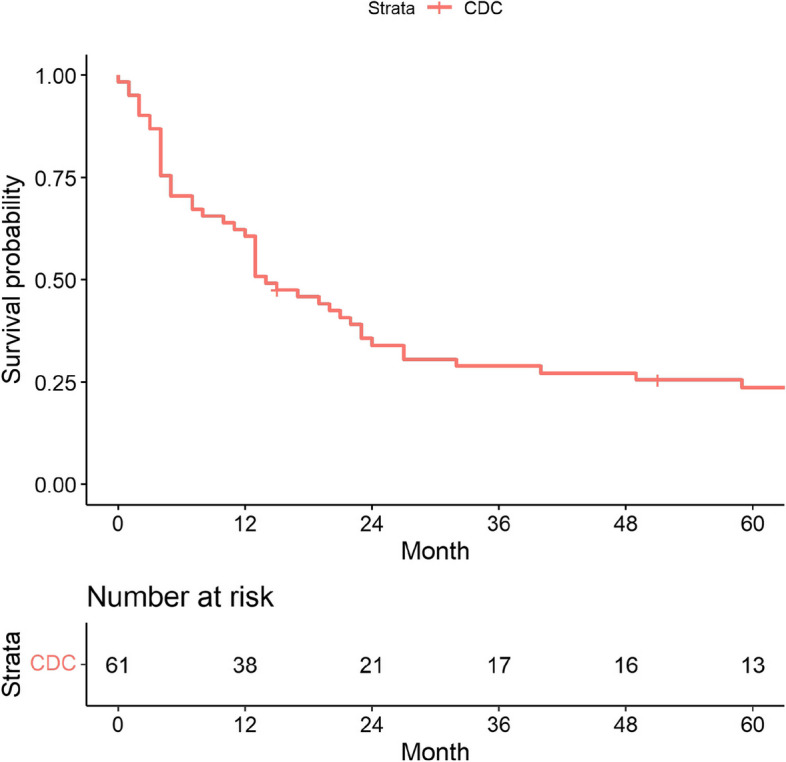

Survival analysis of CDC patients

The median follow-up was 14 months in the present study (range 0–86 months). As shown in Fig. 2, the 1-year, 2-year, and 5-year OS rates for all CDC patients in Japan at 2013 were 60.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 49.6–74.2), 34.0% (95% CI: 23.9–48.3), and 23.6% (95% CI: 15.0–37.4), respectively. The median OS was 14 months (95% CI: 12–24). Next, we performed survival analysis according to staging data (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The 5-year OS rates for CDC patients at stages I, III, and IV were 53.0% (95% CI: 29.9–94.0), 35.7% (95% CI: 19.8–64.4), and 3.4% (95% CI: 0.5–23.7), respectively. Of note, the 1-year OS for stage IV patients was 27.6% (95% CI: 0.5–23.7) and the median OS was only 5 months (95% CI: 4–12).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analyses of OS for all patients

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analyses of OS, stratified by stage

Table 2.

OS rates, stratified by stage

| 1-year OS | 2-year OS | 5-year OS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I (%) | 100 (100–100) | 72.7 (50.6–100) | 53.0 (29.9–94.0) |

| Stage II (%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Stage III (%) | 85.7 (72.0–100) | 56.1 (38.2–82.5) | 35.7 (19.8–64.4) |

| Stage IV (%) | 27.6 (15.3–49.7) | 3.4 (0.5–23.7) | 3.4 (0.5–23.7) |

OS overall survival, NA not available

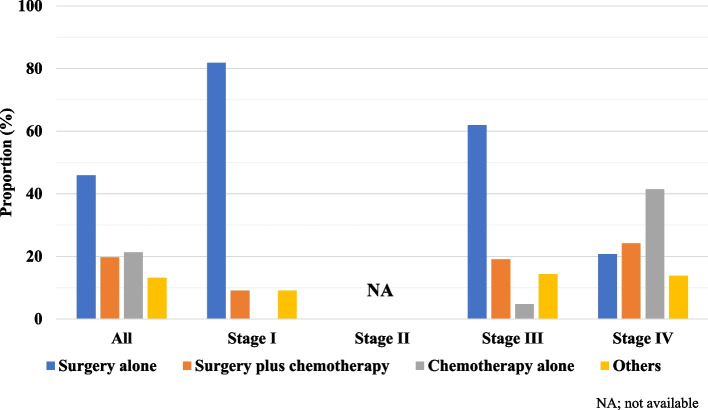

Treatment modalities for CDC patients

The treatment modalities for CDC patients according to staging are shown in Fig. 4. Of all patients, 45.9% underwent surgery, 21.3% received chemotherapy alone, and 19.7% received both. With regard to staging, 81.8% of stage I patients underwent surgery alone while 61.9% of stage III patients and only 20.7% of stage IV patients did the same. On the other hand, even if combination treatment with surgery plus chemotherapy was more frequently selected for patients with advanced disease (stage III: 19%, stage IV: 24.1%), 41.4% of patients at stage IV received only chemotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Patterns of first-course treatment received, stratified by stage

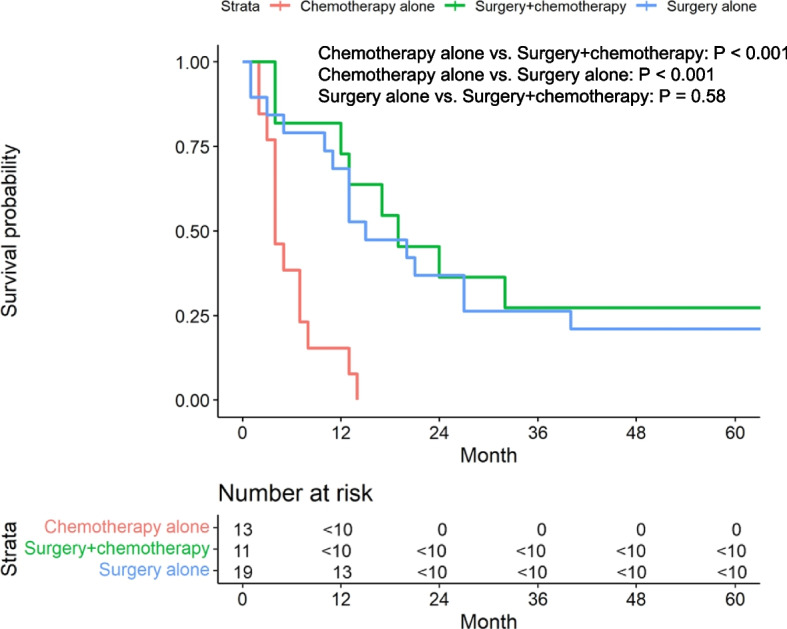

We next examined the OS rates of advanced disease according to treatment modalities (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the median OS of patients who received chemotherapy alone was significantly shorter than surgery alone (4 months [95% CI: 4-NA] vs 15 months [95% CI: 13–68]; p < 0.001) and surgery-only patients had a similar median OS to surgery-plus-chemotherapy patients (19 months [95% CI: 13-NA]; p < 0.001). The median age was not significantly different among the three groups (P = 0.524; Supplementary Table S1). However, there were the difference in the selected treatment modalities according to stages (Fig. 4). Therefore, we conducted a multivariable analysis for the OS in patients with advanced disease (Fig. 6), revealing that surgery-plus-chemotherapy patients had significantly more favorable prognoses (HR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.07–0.57). In addition, although not significant, the OS of surgery-only patients trended better than chemotherapy-only patients (HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.30–2.19).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier analyses of OS in advanced disease (stages III-IV), stratified by first-course treatment

Fig. 6.

Multivariable analysis of the OS in patients with advanced disease

Discussion

Clinically, CDC is a very aggressive subtype of RCC that is likely to present as an advanced-stage tumor with lymph node involvement and metastatic disease. Previous large-cohort studies showed that 28–42% of CDC patients already had nodal metastatic disease and 32–45% already had distant metastatic disease at diagnosis [3, 5, 6, 11]. In the present study, the rates of nodal and distant metastatic diseases were 50.8% and 39.3%, an aggressiveness consistent with previous reports.

In the present study, the 1-year and 5-year OS rates were 60.7% and 23.6%, somewhat similar to the rates reported by Tokuda et al., who observed 1-year and 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) rates of 69.0%, and 34.4% in Japanese CDC patients [6]. In a Western study, May et al. reported 1-year and 5-year DSS rates of 60.4% and 40.3% [11]. Similarly, Panunzio et al. reported that the 1-year and 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates of American CDC patients were 57.8% and 33.2% [11]. These results suggest minimal differences in CDC prognoses between Japan and Western countries.

The present study revealed the 5-year OS rates in 2013 CDC patients at stages I, III, and IV to be 53.0%, 35.7%, and 3.4%, respectively. In particular, the median OS was 5 months and the 1-year OS rate was 27.6% in stage IV CDC patients. Similarly, Panunzio et al. reported a median OS of 7 months and a 1-year OS rate of 30.9% in American stage IV CDC patients [11]. Due to the commonality of late diagnosis, these rates are certainly dependent on first-line therapy choice and, currently, platinum-based chemotherapies are considered to be standard for metastatic disease [1]. To this end, a previous phase II study reported on the efficacy of gemcitabine plus cisplatin or carboplatin [12], revealing a median OS of 10.5 months and a 1-year OS rate of 48% in metastatic CDC [12]. However, such low OS rates for metastatic disease remain unsatisfactory and our results support the need for surgery; novel and effective systemic therapies for CDC patients are strongly desired.

There are several Western studies that evaluated the efficacy of molecular targeted therapies and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for CDC [13–15]. Thibault et al. reported a prospective phase II trial of gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with bevacizumab [13], but survival benefits from addition of bevacizumab were minor (median OS: 11.1 months). The BONSAI trial, an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 clinical trial, also failed to demonstrate any remarkable efficacy of cabozantinib for metastatic CDC patients (median OS: 7 months) [14]. On the other hand, Buti et al. reported oncological outcomes of nivolumab after cabozantinib failure in the BONSAI trial cohort [15] and found that three of four patients obtained some degree of disease control (one partial response, two stable disease). The progression-free survival (PFS) in the Buti study ranged from 2.8 to 19.9 months and the OS ranged from 5.1 to 26.5 months. Similarly, diverse case reports and series showed complete or partial responses with ICIs, such as nivolumab monotherapy or nivolumab plus ipilimumab, for metastatic CDC [16–20]. These suggest a potential benefit of ICIs for patients with CDC, although there is no available prospective data from current clinical trials.

CDC patients who were treated with chemotherapy alone had extremely poor prognoses for advanced disease (stages III and IV) in the present study. Cytoreductive surgery, in select cases, could possibly be considered for tumor burden reduction and may contribute to prognostic improvements for advanced CDC patients. Sui et al. demonstrated such improved survival through the combination of cytoreductive surgery with chemotherapy or radiotherapy in metastatic CDC patients, compared to cytoreductive surgery alone or chemotherapy/radiation alone [3]. Moreover, Qian et al. investigated the significance of cytoreductive nephrectomy, using the SEER database [21], demonstrating that cytoreductive nephrectomy independently improved survival outcomes for metastatic CDC patients. The present study supports this theory by revealing that the OS times of CDC patients who were treated with surgery alone or surgery plus chemotherapy were significantly longer than chemotherapy alone. Taken together, our results add to the collective knowledge that recommends combining cytoreductive surgery, even for advanced cases.

The present study has several limitations. First, due to its low incidence in Japan, the overall recorded number of CDC cases was small despite the large number of patients in the HBCR database. Therefore, our observations require interpretations that account for marginal sample sizes and comparisons of small subgroups. Second, there was no detailed information about the clinical status of individual patients in this registry since HBCR data does not include patient characteristics and treatment details. Therefore, it is possible that some patients who were not good candidates for surgery were included in the present study and this might have affected or influenced our results. Moreover, since information on regimens and the number of courses was unavailable, treatment-based analyses of the prognoses could not be performed. Finally, a central pathology review was not available. It should be mentioned that heterogeneity in pathological assessments could have led to misdiagnoses. However, despite these limitations, the HBCR was repeatedly proven to be a reliable database administered by trained cancer registrars and the present study contributes to the scarce body of knowledge regarding rare CDC in Japan.

Conclusions

We presented the prognoses of CDC patients using a real-world, large-cohort dataset and found them as extremely poor in Japan as in Western countries. In particular, CDC patients who received chemotherapy alone for advanced disease had poor prognoses, compared with surgery alone or surgery plus chemotherapy. Thus, first-line treatment choices are more important than ethnicity with regard to CDC, especially in the advanced stages. Accumulation of specific data on international CDC cases will be instructive as to the details of optimal first-line therapies.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table S1. The median age of advanced CDC patients among the treatment modalities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all administrators at each institution who were involved in the creation of the database and to the National Cancer Center Japan for compiling the data.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Collecting duct carcinoma

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- DCCH

Designated cancer care hospital

- DSS

Disease-specific survival

- HBCR

Hospital-Based Cancer Registry

- ICD-O-3

International Classification of Disease for Oncology 3rd edition

- ICI

Immune check inhibitor

- NCD

National Cancer Database

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Authors’ contributions

SK built the concept and design of the study. SN and KK acquired the data. SN, SS, BI, TT, AI, AH and MS analyzed and interpreted the data. SK drafted the manuscript. SS, YN, TK, BJM, HNe, AO, TH and HNi revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol and data processing were approved by the University of Tsukuba Institutional Review Board (R03-228). All patients gave written, informed consent. All methods were performed under the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guideline of the University of Tsukuba.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cabanillas G, Montoya-Cerrillo D, Kryvenko ON, Pal SK, Arias-Stella JA 3rd. Collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney: diagnosis and implications for management. Urol Oncol. 2022;40(12):525–36. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karakiewicz PI, Trinh QD, Rioux-Leclercq N, de la Taille A, Novara G, Tostain J, Cindolo L, Ficarra V, Artibani W, Schips L, Zigeuner R, Mulders PF, Lechevallier E, Coulange C, Valeri A, Descotes JL, Rambeaud JJ, Abbou CC, Lang H, Jacqmin D, Mejean A, Patard JJ. Collecting duct renal cell carcinoma: a matched analysis of 41 cases. Eur Urol. 2007;52(4):1140–5. 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sui W, Matulay JT, Robins DJ, James MB, Onyeji IC, RoyChoudhury A, Wenske S, DeCastro GJ. Collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney: Disease characteristic and treatment outcomes from the National Cancer Database. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(9):540.e13-540.e18. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saad AM, Gad MM, Al-Husseini MJ, Ruhban IA, Sonbol MB, Ho TH. Trends in Renal-Cell Carcinoma Incidence and Mortality in the United States in the Last 2 Decades: A SEER-Based Study. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17(1):46-57. e5. 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panunzio A, Tappero S, Hohenhorst L, Cano Garcia C, Piccinelli M, Barletta F, Tian Z, Tafuri A, Briganti A, De Cobelli O, Chun FKH, Terrone C, Kapoor A, Saad F, Shariat SF, Cerruto MA, Antonelli A, Karakiewicz PI. Collecting duct carcinoma: Epidemiology, clinical characteristics and survival. Urol Oncol. 2023;41(2):119.e7-110.e14. 10.1016/j.euo.2023.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokuda N, Naito S, Matsuzaki O, Nagashima Y, Ozono S, Igarashi T. Japanese Society of Renal Cancer. Collecting duct (Bellini duct) renal cell carcinoma: a nationwide survey in Japan. J Urol. 2006;176(1):40–3. 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higashi T, Nakamura F, Shibata A, Emori Y, Nishimoto H. The National Database of Hospital-based Cancer Registries: A Nationwide Infrastructure to Support Evidence-based Cancer Care and Cancer Control Policy in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(1):2–8. 10.1093/jjco/hyt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuyama A, Higashi T. Patterns of cancer treatment in different age groups in Japan: an analysis of hospital-based cancer registry data, 2012–2015. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(5):417–25. 10.1093/jjco/hyy032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuyama A, Tsukada Y, Higashi T. Coverage of the hospital-based cancer registries and the designated cancer care hospitals in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51(6):992–8. 10.1093/jjco/hyab036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Core Team. R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.May M, Ficarra V, Shariat SF, Zigeuner R, Chromecki T, Cindolo L, Burger M, Gunia S, Feciche B, Wenzl V, Aziz A, Chun F, Becker A, Pahernik S, Simeone C, Longo N, Zucchi A, Antonelli A, Mirone V, Stief C, Novara G, Brookman-May S, CORONA and SATURN project; Young Academic Urologist Renal Cancer Group. Impact of clinical and histopathological parameters on disease specific survival in patients with collecting duct renal cell carcinoma: development of a disease specific risk model. J Urol. 2013;190(2):458–63. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oudard S, Banu E, Vieillefond A, Fournier L, Priou F, Medioni J, Banu A, Duclos B, Rolland F, Escudier B, Arakelyan N, Culine S, GETUG. Prospective multicenter phase II study of gemcitabine plus platinum salt for metastatic collecting duct carcinoma: result of a GETUG (Group d’Etudes des Tumeurs Uro-Génitales) study. J Urol. 2007;177(5):1698–702. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thibault C, Fléchon A, Albiges L, Joly C, Barthelemy P, Gross-Goupil M, Chevreau C, Coquan E, Rolland F, Laguerre B, Gravis G, Pécuchet N, Elaidi RT, Timsit MO, Birhoum M, Auclin E, de Reyniès A, Allory Y, Oudard S. Gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with bevacizumab for kidney metastatic collecting duct and medullary carcinomas: Results of a prospective phase II trial (BEVABEL-GETUG/AFU24). Eur J Cancer. 2023;186:83–90. 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Procopio G, Sepe P, Claps M, Buti S, Colecchia M, Giannatempo P, Guadalupi V, Mariani L, Lalli L, Fucà G, de Braud F, Verzoni E. Cabozantinib as First-line Treatment in Patients With Metastatic Collecting Duct Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results of the BONSAI Trial for the Italian Network for Research in Urologic-Oncology (Meet-URO 2 Study). JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(6):910–3. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buti S, Trentini F, Sepe P, Claps M, Isella L, Verzoni E, Procopio G. BONSAI-2 study: Nivolumab as therapeutic option after cabozantinib failure in metastatic collecting duct carcinoma patients. Tumori. 2023;109(4):418–23. 10.1177/03008916221141483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizutani K, Horie K, Nagai S, Tsuchiya T, Saigo C, Kobayashi K, Miyazaki T, Deguchi T. Response to nivolumab in metastatic collecting duct carcinoma expressing PD-L1: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7(6):988–90. 10.3892/mco.2017.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasuoka S, Hamasaki T, Kuribayashi E, Nagasawa M, Kawaguchi T, Nagashima Y, Kondo Y. Nivolumab therapy for metastatic collecting duct carcinoma after nephrectomy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(45): e13173. 10.1097/MD.0000000000013173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe K, Sugiyama T, Otsuka A, Miyake H. Complete response to combination therapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab for metastatic collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney. Int Cancer Conf J. 2019;9(1):32–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danno T, Iwata S, Niimi F, Honda S, Okada H, Azuma T. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab Combination Immunotherapy for Patients with Metastatic Collecting Duct Carcinoma. Case Rep Urol. 2021; 9936330. 10.1007/s13691-019-00389-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Fuu T, Iijima K, Kusama Y, Otsuki T, Kato H. Complete response to combination therapy using nivolumab and ipilimumab for metastatic, sarcomatoid collecting duct carcinoma presenting with high expression of programmed death-ligand 1: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16(1):193. 10.1186/s13256-022-03426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian X, Wan J, Tan Y, Liu Z, Zhang Y. Impact of treatment modalities on prognosis of patients with metastatic renal collecting duct carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12678. 10.1038/s41598-022-16814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table S1. The median age of advanced CDC patients among the treatment modalities.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.