Background

This observational prospective cross-sectional study was conducted during the last 4 months of the COVID-19 pandemic to determine whether parental hesitancy to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 had improved compared to earlier studies in other countries showing high levels of hesitancy. Methods: Parents were surveyed from January 4 until May 16, 2023, at two tertiary medical centers in Beirut, the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) and the Saint George Hospital University Medical Center (SGHUMC). Results: The study enrolled 950 participants, predominantly mothers (79.6%) aged 30–49 (79%), highly educated parents (69.8% of mothers and 62.2% of fathers were university graduates). Although routine childhood vaccinations received remarkable acceptance (98.3%), there was considerable hesitancy towards pediatric COVID-19 (56.4%). Only 9.4% had vaccinated all eligible children. The main parental concern was the vaccine’s safety and perceived lack of testing (p < 0.001). Other factors were parental gender, vaccination status, and children’s age. In the adjusted model, mothers had a higher rate of vaccine acceptance (AOR: 1.746 [1.059–2.878], p = 0.029). Similarly, parents vaccinated against COVID-19 vaccine (AOR: 2.703, p < 0.001) and parents of children aged 12–17 (AOR: 4.450, p < 0.001) had more vaccine acceptance. Conclusion: This study’s findings indicate a persistently high level of hesitancy for pediatric COVID-19 vaccination despite more than two years of positive global experience with the vaccine. Raising awareness about the safety and effectiveness of pediatric COVID-19 vaccination would address this hesitancy and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on children’s health and well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s44197-025-00364-3.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Parents, Children, Lebanon

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which was declared in March 2020 and ended in May 2023, was unprecedented in its spread and impact [1, 2]. In comparison to other coronaviruses, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of COVID-19, has a higher airborne transmission rate, with high morbidity and mortality [3].

Therefore, a major effort to control this pandemic was placed on the development of new effective vaccines, which was successfully accomplished in record time [4]. As the vaccines were rolled out, priority was given to frontline healthcare workers and the geriatric population, due to their increased risk of COVID-19 complications [3]. Initial trials studying the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines were done on subjects 16 years of age and older, as the disease in younger individuals was believed to be mild in comparison to older patients [4]. Subsequent trials examined the efficacy and safety of mRNA vaccines in adolescents 12–16 years of age, children 5–11 years of age, and children 6 months to 5 years of age [4, 5]. COVID-19 vaccines were found to be effective in generating neutralizing antibodies and generally well-tolerated; mostly caused mild to moderate side-effects, including pain, erythema and lymphadenopathy at the site of injection [6].

However, given that COVID-19 posed a relatively low risk to children, there was some debate on the need to vaccinate children against COVID-19 [5]. However, the vaccine was recommended for children as a form of defense against the consequences of the infection, such as several symptoms under the severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), or the “long-COVID” umbrella [7]. Still, several surveys among parents performed early in the pandemic showed high levels of hesitancy in vaccinating children and adolescents in both high-income and low- and middle-income countries (HIC, LMIC, respectively) [8–13].

To ensure control of the pandemic and equity in vaccine access, a global initiative, the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX), was launched by the WHO, Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance), and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) [4]. Through this initiative, the aim was to support low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) as well as to coordinate and advance global vaccine development [14]. In Lebanon, the national vaccination campaign commenced on the 14th of February 2021 [15]. Initially, vaccination targeted priority and high-risk groups, and subsequently vaccination for children 5 years of age and older was initiated. During that period, hesitancy to vaccinate children was observed among parents in Lebanon and the Eastern Mediterranean Region [16].

In the current study, we aimed to determine whether parental hesitancy to vaccinate their children had changed towards the end of the pandemic after pediatric vaccines had been rolled out for almost two years and to identify the factors affecting their decision.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

From January 4 until May 16, 2023, convenience sampling was utilized to conduct an observational prospective cross-sectional study at two medical centers in Beirut: The American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) and Saint George Hospital University Medical Center (SGHUMC). Both medical centers are tertiary care centers affiliated with academic institutions and located in Beirut, Lebanon. As such, both AUBMC and SGHUMC not only provide high-quality healthcare to the greater Beirut population but also simultaneously serve as referral centers for patients requiring specialized care across Lebanon.

Participants

Participants were recruited based on specific inclusion criteria: (1) parents with children under 18 years old visiting the private clinics, the Outpatient Department (OPD), or the pediatric inpatient services at AUBMC or SGHUMC, and (2) those providing informed oral consent to participate in this study. Within AUBMC, the OPD is a section of the medical center where patients receive primary care, specialist consultations and medical treatment for minimal fees designed to be accessible and affordable for underprivileged populations. Subsequently, it serves underprivileged communities, including those without health insurance or unable to afford private medical care. Concerning the study’s exclusion criterion, it excluded children who were not accompanied by their parents or legal caregivers.

Questionnaire

The research team designed the survey in two languages, English and Arabic, to accommodate the participants’ language of choice (Supplementary material). The survey for this study was carefully drafted after an extensive literature review, inspired by three similar studies to ensure the inclusion of questions most relevant to our area of interest [17–19]. Subsequently, the questionnaire underwent internal validation by experts specializing in pediatrics and infectious diseases. The survey had two major sections, the first related to parents/caregivers and the second to the child/children. The first section covered socio-demographic information about the parents/caregivers, including their age, number of children, nationality, residency, education level, employment, religion, the number of people (including elderly and individuals working in the healthcare sector) living in the same house and the number of rooms, and whether the parents had received the COVID-19 vaccine or not. The second section covered data relating to the child/children including their sex, age, insurance, previous vaccination history, chronic illness history, and whether their parents were willing to or had already vaccinated them with the COVID-19 vaccine. If the parents had accepted vaccinating their children, they were asked whether their children had experienced any side effects and about their source of recommendation. If they had refused to vaccinate them, parents were asked about reasons for refusal. Parents were asked whether they worried about pain, discomfort, or long-term side effects when giving their child previous immunization. Finally, parents were also asked general questions about COVID-19 and the resources they used for obtaining information about the disease.

Study Procedures

Upon both hospitals’ Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval of the study in December 2022, researchers began conducting interviews from Monday to Friday between 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. to acquire oral consent and start data collection. Trained doctors and medical students approached the parents in the hospital’s inpatient rooms as well as in the waiting rooms of the OPD and clinics. Afterwards, when an oral consent was given, a face-to-face 15-minute-interview was performed, and data was collected in a private room to secure privacy and confidentiality.

Data Processing and Analysis

Collected data were entered into Redcap and downloaded and coded in the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 (SPSSTM Inc., Chicago, IL United States). Descriptive statistics were performed to describe the baseline characteristics of the study population and to calculate the proportions of parental acceptance or refusal to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 infection, reasons for refusal, sources of recommendations and COVID-19 information, and perceptions regarding immunizations and COVID-19 vaccination. Moreover, univariate analyses were conducted. The explanatory variables were first tested 1 by 1 against the dependent variable (codes: 0 = Unvaccinated, parent reluctant to vaccinate their children; 1 = Unvaccinated, parent open to vaccinate their children OR Vaccinated children) for the presence of a significant association through binomial logistic regression. In the multivariable logistic regression model, we included variables that showed a significant association at p ≤ 0.05 in the univariate analysis. The goodness-of-fit statistic determined if the model provides a good fit for the data (p > 0.05). The strength of association was interpreted using the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence Interval (CI). A p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The IRB at AUBMC (IRB protocol number: SBS-2022-0271) and at SGHUMC (IRB protocol number: IRB-REC/O/015–23/2022) approved this study, in line with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association, the Declaration of Helsinki [20]. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose and features as well as informed of their voluntary participation, the confidentiality of their personal data and their right to withdraw at any time throughout the study. Furthermore, they were informed that there was no risk or benefit from their participation. An informed oral consent was required prior to data collection. In addition, to maintain confidentiality, the research team did not have access to participant names or contact details after data entry. No identifiers were collected on the case report form (CRF). Additionally, confidentiality was secured through the coding of the CRFs, which were placed in a locked office and uploaded into a password-protected database, only accessed by the IRB-approved research team, after which the data will be deleted and all CRFs will be discarded once the legal period of 5 years expires following publication.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants

In the present study, out of 1,217 approached subjects (782 at AUBMC and 435 at SGHUMC), 950 were enrolled (647 at AUBMC and 303 at SGHUMC) with a 78% response rate.

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of parents and their children. The respondents were predominantly mothers, accounting for 79.6%. The largest age group was 30–49 years of age, with a percentage of 79%. In terms of residence, the majority were living in Mount Lebanon or Beirut (25.7% and 24.5%, respectively). With regards to education, the participants were highly educated with 69.8% of mothers and 62.2% of fathers being university graduates.

Table 1.

Participants’ baseline characteristics (N = 948)

| Demographics | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The responder (n = 948) | ||

| Mother | 755 | 79.6 |

| Father | 193 | 20.4 |

| Mother’s Age (n = 946) | ||

| 17–29 | 146 | 15.4 |

| 30–49 | 747 | 79 |

| 50 and above | 53 | 5.6 |

| Father’s Age (n = 942) | ||

| 17–29 | 41 | 4.4 |

| 30–49 | 735 | 78 |

| 50 and above | 166 | 17.6 |

| Mother’s Nationality (n = 947) | ||

| Lebanese | 798 | 84.3 |

| Non-Lebanese | 149 | 15.7 |

| Father’s Nationality (n = 946) | ||

| Lebanese | 810 | 85.6 |

| Non-Lebanese | 136 | 14.4 |

| Residence (n = 948) | ||

| Mount Lebanon | 244 | 25.7 |

| Beirut | 232 | 24.5 |

| South | 41 | 4.3 |

| North | 27 | 2.8 |

| Keserwan- Jbeil | 24 | 2.5 |

| Other residence* | 44 | 4.6 |

| Not residing in Lebanon | 23 | 2.4 |

| Unspecified | 313 | 33 |

| Mother’s Educational Level (n = 947) | ||

| University | 661 | 69.8 |

| Secondary Education | 42 | 4.4 |

| Complementary Education | 111 | 11.7 |

| Primary Education | 58 | 6.1 |

| Technical Education | 53 | 5.6 |

| No formal Education | 22 | 2.3 |

| Father’s Educational Level (n = 945) | ||

| University | 588 | 62.2 |

| Secondary Education | 62 | 6.6 |

| Complementary Education | 119 | 12.6 |

| Primary Education | 71 | 7.5 |

| Technical Education | 84 | 8.9 |

| No formal Education | 21 | 2.2 |

| Mother’s job (n = 935) | ||

| Students, unemployed, or retired | 556 | 59.5 |

| Businesspersons, and service workers | 174 | 18.6 |

| Administrators, staff, cultural educators | 120 | 12.8 |

| Healthcare workers | 69 | 7.4 |

| Workers and farmers | 16 | 1.7 |

| Father’s job (n = 948) | ||

| Businesspersons, and service workers | 381 | 40.2 |

| Workers and farmers | 202 | 21.3 |

| Administrators and staff | 175 | 18.5 |

| Healthcare workers | 53 | 5.6 |

| Others (students, unemployed, retired, and others) | 137 | 14.5 |

| Parent working at a healthcare facility or setting (n = 943) | ||

| No | 804 | 85.3 |

| Yes | 139 | 14.7 |

| Religion (n = 948) | ||

| Muslim | 576 | 60.8 |

| Christian | 278 | 29.3 |

| Other, unspecified | 38 | 4 |

| Prefer not to answer | 56 | 5.9 |

| Elderly at home (n = 945) | ||

| No | 839 | 88.8 |

| Yes | 106 | 11.2 |

| Number of children (n = 948) | ||

| 1 | 254 | 26.8 |

| 2 to 3 | 557 | 58.8 |

| 4 and above | 137 | 14.5 |

| Gender of children (n = 947) | ||

| Both | 452 | 47.7 |

| Boys | 267 | 28.2 |

| Girls | 228 | 24.1 |

| Children age group (n = 1,376) ** | ||

| < 6 months | 85 | 8.9 |

| 6 months − 4 years | 477 | 50.2 |

| 5–11 years | 531 | 55.9 |

| 12–17 years | 283 | 29.8 |

| Child Insurance (n = 950) | ||

| National Social Security Fund | 153 | 16.1 |

| Civil Servant Cooperative | 6 | 0.6 |

| Ministry of Health | 16 | 1.7 |

| Security Forces | 27 | 2.8 |

| Army security | 31 | 3.3 |

| Private insurance | 533 | 56.1 |

| Other insurance*** | 71 | 7.5 |

| Daycare/school attendance (n = 949) | ||

| No | 183 | 19.3 |

| Yes | 764 | 80.5 |

| Online tutoring | 2 | 0.2 |

*Other residence: Akkar (n = 17), Bekaa (n = 14), Baalbeck-Hermel (n = 9), Nabatieh (n = 4)

** The total number is 1,376 > the total population (n = 950) because the respondents may have more than 1 child within the same age group

***Other insurance: UNHCR (n = 34), HIP (n = 12), UNRWA (n = 7), UN (n = 5), Engineers syndicate (n = 3), order of dentists (n = 1), The Islamic Health Authority (n = 1), Al Sanjoub Association (n = 1), SCID (n = 1), Sickle cell fund (n = 1), Al Hayat Project (n = 1), unspecified (n = 4)

When asked about employment, 55.2% of mothers reported being unemployed whereas 95% of fathers were working. Of the respondents 14.7% worked in a healthcare facility, and 11.1% stated that an elderly person lived in the same household. Of the households surveyed, 50.2% and 55.9% had children aged 6 months to 4 years, or 5 to 11 years of age, respectively, with 58.8% having 2–3 children and 47.7% having both boys and girls. Most children attended daycare or school (80.5%), and 56.1% had private insurance.

Parents’ Attitude Towards Vaccination

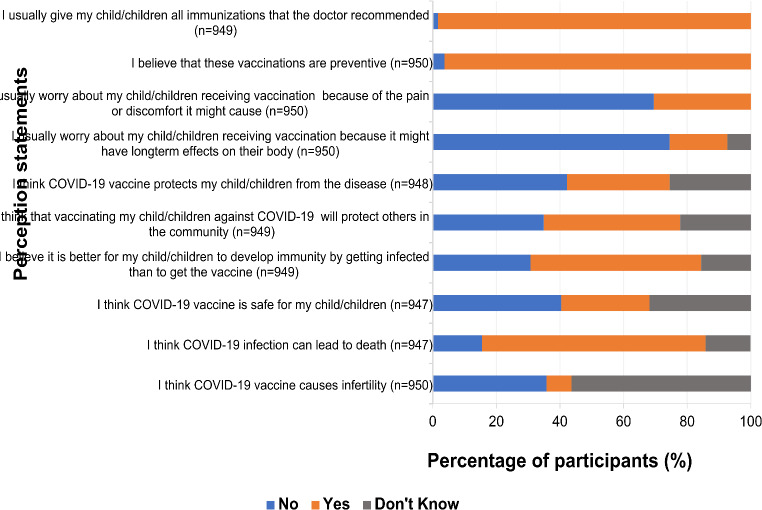

Approximately 98.3% of parents confirmed that they had given their children all the immunizations included on National Immunization Program schedule, which doesn’t include COVID-19 vaccine”. The majority, consisting of 96.3% of participants, believed in the preventative nature of these vaccinations. A notable 69.5% of parents expressed a lack of concern about any discomfort or pain the vaccinations may have inflicted on their children. Furthermore, 74.5% of the parents reported no apprehension about any potential long-term side effects upon their children receiving the vaccinations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Parents’ perceptions about vaccination in general, and COVID-19 vaccine in specific

Although 70.3% of parents acknowledged the severity of COVID-19 infection and its possible fatal nature, their perceptions differed when asked about the COVID-19 vaccine. When asked whether they believed COVID-19 vaccine protects their children from the disease, 42.2% reported they did not believe it would. In contrast, 42.9% believed in its capacity to protect others in the community. However, about half of the parents (53.7%) believed that it is better for their children to develop natural immunity through getting infected with COVID-19 than to get protected through immunization. In fact, 40.4% of participants reported concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine safety. Interestingly, when asked if they believed it could cause infertility as a side effect, 56.4% of the participants stated uncertainty (Fig. 1).

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease-2019.

Parents’ Acceptance to Vaccinate Their Children

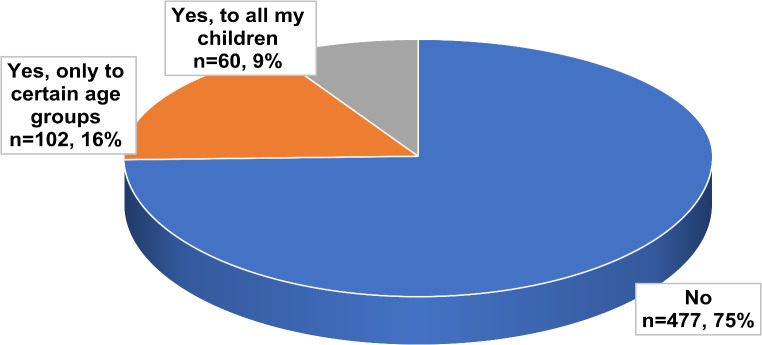

Upon asking parents with children and adolescents aged 5–17 years old, n = 639, whether they had given their children the COVID-19 vaccine, a majority (74.6%) reported they had not. A minority (9.4%) had given the vaccine to all their eligible children and another fraction of parents (16%) claimed they only did so to a select age group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Parents’ responses to whether they have vaccinated their children against COVID-19 infection (n = 639)

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease-2019.

Of those children who received the COVID-19 vaccine (n = 157), 55.4% of their parents reported that they did not experience any adverse side effects from the vaccine (Table 2). Almost 43% of parents described that their children had encountered mild effects such as pain, fever, and swelling of the site of injection, whereas a small portion reported moderate effects requiring medical consultation, but no hospital stay, and some serious symptoms requiring hospitalization after vaccination (1.3 and 0.6% respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

COVID-19-vaccinated children’s adverse events

| Child’s experience of any adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination (n = 157) | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No | 87 | 55.4 |

| Yes, mild (fever, pain or swelling at the injection site- not requiring medical consultation) | 67 | 42.7 |

| Yes, moderate (symptoms requiring medical consultation but not hospitalization) | 2 | 1.3 |

| Yes, serious (requiring admission to the hospital) | 1 | 0.6 |

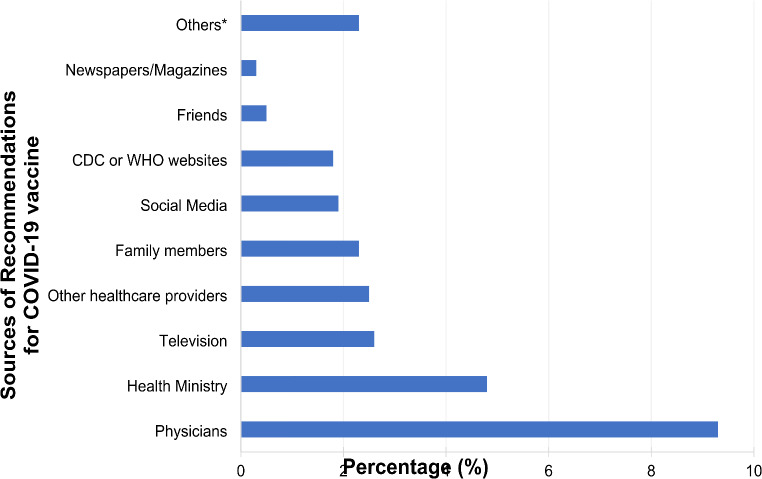

When parents were asked about the sources of recommendations for administering the COVID-19 vaccine to their children, the majority indicated that they had received guidance primarily from their physicians (9.3%) and the Ministry of Health (4.8%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sources of recommendations for COVID-19 vaccine

*Other sources of recommendations: School, Workplace, travel agency, personal choice.

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019.

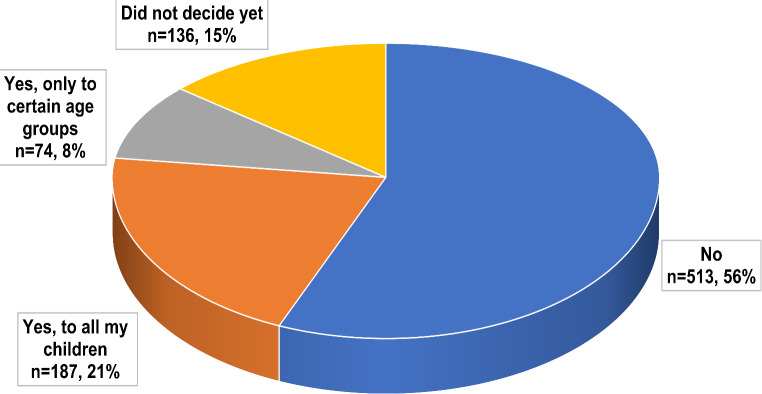

When all the parents that were approached, including the ones who had previously vaccinated their children, were asked if they were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine in the future, 56.4% reported refusal (Fig. 4). Of those parents who accepted future COVID-19 vaccines, 20.5% were willing to vaccinate all their children, whereas 8.1% would only vaccinate a certain age group (Fig. 4). The remaining 14.9% of parents were undecided (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Willingness of parents to vaccinate their children against COVID-19

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019.

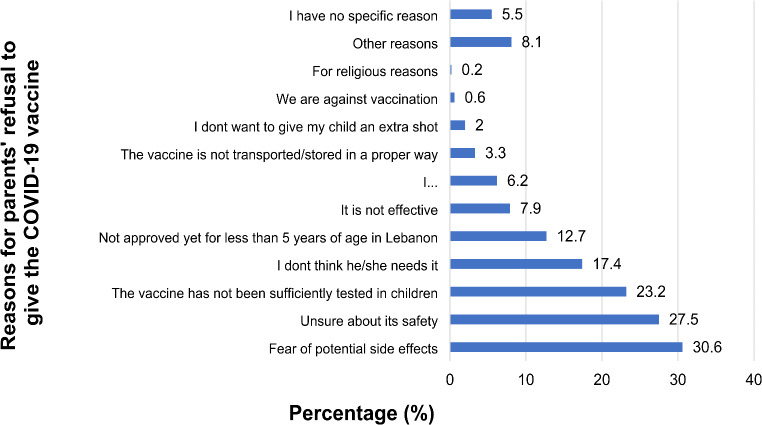

Questions were posed to understand the parents’ reasons for refusal. Fear of potential side effects of the vaccine accounted for 30.6% and being unsure about its safety accounted for 27.5% (Fig. 5). Another reason was the lack of sufficient testing of the vaccine in children (23.2%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Reasons for parents’ refusal to give the COVID-19 vaccine to their children

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019.

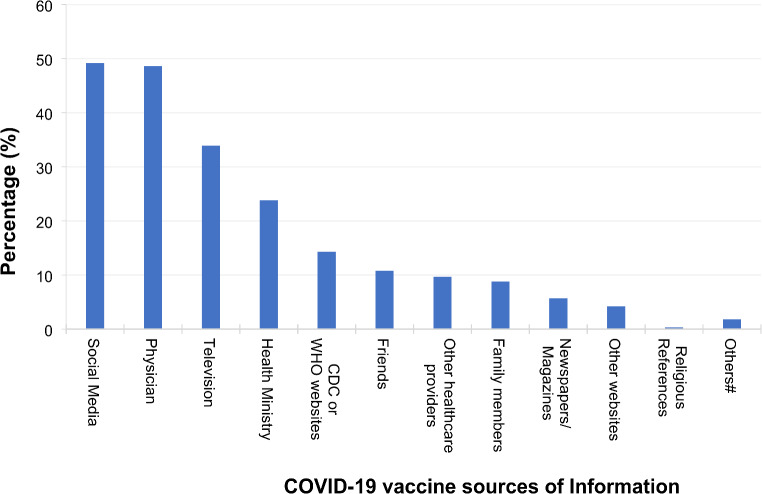

Sources of COVID-19 Information

Parents relied mainly on social media and physicians’ recommendations as the two most important sources of information about COVID-19 vaccine, with percentages consisting of 49.2% and 48.6%, respectively (Fig. 6). Other sources of information included television (33.9%), Ministry of Public Health (23.8%), CDC or WHO websites (14.3%), and friends (10.8%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Sources and the level of information of the parents about COVID-19 vaccine

#Other sources of COVID-19 information: Workshops at workplace, UNRWA, School, CIDR, awareness campaigns, organizations, CIDR, no source of information, unspecified other source of information.

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019; CDC, Center for Diseases and Prevention Control; WHO, World Health Organization.

Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Parents

Adjusted Model

When we performed multivariable regression using the adjusted model, several variables that had shown statistical significance in the unadjusted model (univariate analysis) were no longer significant. These variables that lost significance included the father’s and mother’s age, their educational level, parents’ healthcare work, child’s religion, children’s health conditions, previous family members being infected with COVID-19, and parents’ perceptions about the COVID-19 vaccine. Upon adjusting for other variables, mothers were found to showcase acceptance towards COVID-19 vaccination of their children (AOR: 1.746 [1.059–2.878], p-value = 0.029), after exhibiting refusal in the univariate model indicating the presence of Simpson’s paradox and suggesting a possible confounding effect. Parents who had previously received the vaccine and those whose children’s ages were 12 to 17 years had high acceptance towards their children’s vaccination (AOR: 2.703 [1.599–4.570], p-value < 0.001) and 12 to 17 years of age (AOR: 4.450 [2.759–7.180], p-value < 0.001), respectively. Furthermore, parents of children aged 6 months to 4 years had high hesitancy towards vaccination (AOR: 0.557 [0.363–0.855, p-value = 0.007). As for parents’ beliefs about the vaccine, those who thought the vaccine protected their children were significantly more likely to accept vaccination (AOR: 3.420 [1.974–5.924], p-value < 0.001). Parents who did not believe that immunity acquired through infection to be better than vaccination remained more willing to vaccinate their children (AOR: 2.406 [1.337–4.329], p-value = 0.003). Finally, parents who perceived the vaccine to be safe were more likely to accept vaccinating their children (AOR: 3.295 [1.973–5.502], p-value < 0.001) and the ones who believed it to be harmful remained hesitant (AOR: 0.310 [0.179–0.538], p-value < 0.001). Notably, Simpsons paradox that was observed for parents who believed the vaccine to be safe as they were hesitant to vaccinate their children in the unadjusted model was resolved in the adjusted model as they accepted the vaccine (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the willingness of parents to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. Associations resulted by the binomial univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Characteristics | Unvaccinated, parent reluctant to vaccinate their children (N = 621) | Unvaccinated, parent open to vaccinate their children OR Vaccinated children (N = 327) | UOR [95% CI] | p-value | AOR [95% CI] | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The responder (n = 948) | ||||||

| Mother | 482 (77.6) | 273 (83.5) | 0.686 [0.485–0.971] | 0.033 | 1.746 [1.059–2.878] | 0.029 |

| Father | 139 (22.4) | 54 (16.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Father’s age (n = 942) | ||||||

| [17y-29y] | 25 (4.0) | 16 (5.0) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| [30y-49y] | 536 (86.5) | 199 (61.8) | 0.580 [0.303–1.109] | 0.1 | NS | NS |

| ≥ 50y | 59 (9.5) | 107 (33.2) | 2.834 [1.402–5.726] | 0.004 | NS | NS |

| Mother’s age (n = 946) | ||||||

| [17y-29y] | 105 (16.9) | 41 (12.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| [30y-49y] | 503 (81.0) | 244 (75.1) | 1.242 [0.839–1.839] | 0.278 | NS | NS |

| ≥ 50y | 13 (2.1) | 40 (12.3) | 7.880 [3.827–16.227] | < 0.001 | NS | NS |

| Educational level of father (n = 945) | ||||||

| No formal education/Primary or Complementary education | 121 (19.5) | 90 (27.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Technical education | 54 (8.7) | 30 (9.2) | 0.747 [0.443–1.260] | 0.274 | NS | NS |

| Secondary or University education | 444 (71.7) | 206 (63.2) | 0.624 [0.453–0.858] | 0.004 | NS | NS |

| Educational level of mother (n = 947) | ||||||

| No formal education/Primary or Complementary education | 110 (17.7) | 81 (24.8) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Technical education | 33 (5.3) | 20 (6.1) | 0.823 [0.440–1.538] | 0.541 | NS | NS |

| Secondary or University education | 478 (77.0) | 225 (69.0) | 0.639 [0.461–0.887] | 0.007 | NS | NS |

| Parent working at a health care facility (n = 943) | ||||||

| Yes | 74 (12.0) | 65 (20.1) | 0.541 [0.376–0.779] | < 0.001 | NS | NS |

| No | 545 (88.0) | 259 (79.9) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Child’s religion | ||||||

| Muslim | 362 (58.4) | 214 (65.2) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Christian | 197 (31.8) | 81 (24.7) | 0.696 [0.511–0.947] | 0.021 | NS | NS |

| Prefer not to answer/Other | 61 (9.8) | 33 (10.1) | 0.915 [0.580–1.444] | 0.703 | NS | NS |

| As a Parent did you get the COVID-19 vaccine (n = 949) | ||||||

| Yes | 470 (75.7) | 290 (88.4) | 2.452 [1.669–3.602] | < 0.001 | 2.703 [1.599–4.570] | < 0.001 |

| No | 151 (24.3) | 38 (11.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Child’s age group: 6 m-4y (n = 950) | ||||||

| Yes | 363 (58.4) | 114 (34.8) | 0.380 [0.288–0.502] | < 0.001 | 0.557 [0.363–0.855] | 0.007 |

| No | 259 (41.6) | 214 (65.2) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Child’s age group: 12–17 years (n = 950) | ||||||

| Yes | 114 (18.3) | 169 (51.5) | 4.736 [3.520–6.374] | < 0.001 | 4.450 [2.759–7.180] | < 0.001 |

| No | 508 (81.7) | 159 (48.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Does your child attend daycare/school (n = 947) | ||||||

| Yes | 499 (80.4) | 265 (81.3) | 1.062 [0.755–1.495] | 0.729 | ||

| No | 122 (19.6) | 61 (18.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Does your child have a chronic disease (n = 950) | ||||||

| yes | 172 (27.7) | 116 (35.4) | 1.432 [1.075–1.907] | 0.014 | NS | NS |

| No | 450 (72.3) | 212 (64.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Immunodeficiency (n = 950) | ||||||

| yes | 6 (1) | 11 (3.4) | 3.563 [1.305–9.722] | 0.013 | NS | NS |

| No | 616 (99) | 317 (96.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Was anyone within your family infected with COVID-19 (n = 946) | ||||||

| Yes | 520 (83.9) | 252 (77.3) | 0.655 [0.468–0.916] | 0.014 | NS | NS |

| No | 100 (16.1) | 74 (22.7) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Has any of your children ever been infected with COVID-19 (n = 949) | ||||||

| yes | 305 (49.1) | 185 (56.4) | 2.093 [1.231–3.556] | 0.006 | NS | NS |

| No | 247 (39.8) | 123 (37.5) | 1.718 [0.998–2.956] | 0.051 | NS | NS |

| Don’t know | 69 (11.1) | 20 (6.1) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Are there any elderly people at home? (n = 945) | ||||||

| Yes | 70 (11.3) | 36 (11) | 0.974 [0.636–1.491] | 0.902 | ||

| No | 549 (88.7) | 290 (89) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Do you think COVID-19 Vaccine protects your child from the disease? (n = 948) | ||||||

| Yes | 92 (14.8) | 214 (65.2) | 8.098 [5.489–11.948] | < 0.001 | 3.420 [1.974–5.924] | < 0.001 |

| No | 340 (54.8) | 60 (18.3) | 0.614 [0.408–0.924] | 0.019 | 1.104 [0.630–1.935] | 0.729 |

| Don’t know | 188 (30.3) | 54 (16.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Do you think that vaccinating your children against COVID-19 will protect others in the community? (n = 949) | ||||||

| Yes | 167 (26.9) | 240 (73.2) | 6.758 [4.503–10.144] | < 0.001 | NS | NS |

| No | 280 (45.1) | 51 (15.5) | 0.857 [0.539–1.362] | 0.513 | NS | NS |

| Don’t know | 174 (28) | 37 (11.3) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| You believe it is better for your child to develop immunity by getting infected than to get the vaccine (n = 949) | ||||||

| Yes | 414 (66.7) | 96 (29.3) | 0.605 [ 0.396–0.924] | 0.02 | 0.700 [0.401–1.222] | 0.21 |

| No | 100 (16.1) | 191 (58.2) | 4.985 [3.230–7.691] | < 0.001 | 2.406 [1.337–4.329] | 0.003 |

| Don’t know | 107(17.2) | 41 (12.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Do you think COVID-19 vaccine is safe for your children? (n = 947) | ||||||

| Yes | 61 (9.9) | 201 (61.3) | 0.035 [0.023–0.055] | < 0.001 | 3.295 [1.973–5.502] | < 0.001 |

| No | 343 (55.4) | 40 (12.2) | 0.123 [0.084–0.180] | < 0.001 | 0.310 [0.179–0.538] | < 0.001 |

| Don’t know | 215 (34.7) | 87 (26.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Do you think COVID-19 vaccine cause infertility? | ||||||

| Yes | 59 (9.5) | 15 (4.6) | 0.673 [0.370–1.223] | 0.194 | NS | NS |

| No | 174 (28.0) | 166 (50.6) | 2.525 [1.899–3.357] | < 0.001 | NS | NS |

| Don’t know | 389 (62.5) | 147 (44.8) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

UOR, Unadjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; Ref, Reference; NS, Not Significant; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019

Discussion

Different COVID-19 vaccines are FDA-approved for children above the age of 6 months, while there are no FDA-approved vaccines for children younger than age 6 months [21]. The current CDC guidelines encourage vaccination for everyone above 6 months of age [22]. Although the WHO acknowledges the benefit of vaccinating children, it prioritizes immunocompromised and elderly patients, who are at a higher risk of severe complications from the virus [14].

Surveys among parents performed early in the pandemic or shortly after pediatric COVID-19 vaccines became available showed high levels of hesitancy [8–13]. A systematic review of peer-reviewed English literature on the topic published between January 2020 and August 2022 revealed parallel conclusions that, among those hesitant to vaccinate, safety concerns topped the list, followed by uncertainties about the vaccine’s novelty [23]. The major reasons for hesitancy that were common also include concern that it was not studied well and its general efficacy as well as a perceived low risk of the virus in children [23]. Our current survey was carried out during the last 4 months of the pandemic, at a time when pediatric vaccination for COVID-19 had been in place for almost two years [24]. The expectation was that two years into pediatric COVID-19 vaccination availability, some of the earlier concerns expressed by parents regarding its safety, novelty, and efficacy would have been alleviated. However, we found in our survey that whereas routine childhood vaccinations received remarkable acceptance (98.3%), there was a high rate of hesitance towards COVID-19 vaccine for children (56.4%). The parental concerns appeared to be essentially similar to those expressed earlier in the pandemic.

Uncertainty about vaccine safety stood out, with apprehension and anxiety regarding potential long-term consequences. Notably, a concerning 53.7% of parents in the current study believed that contracting the virus and acquiring natural immunity offer a preferable alternative to vaccination, highlighting a misconception that needs to be addressed through targeted education campaigns. Similarly, in a study conducted by Katatbeh M. et al. in 2022 in eight countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region, including Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), one-third of the study’s sample (32.5%) were concerned about the vaccine’s safety [16]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis on parents’ and guardians’ willingness worldwide to vaccinate their children against COVID-19, safety of the vaccines was the most frequently reported reason for hesitancy, amounting to approximately 60.99% (95% CI: 48.37–72.30%) of participants [25].

Parental attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination for their children were not uniform, revealing intriguing variations across demographic groups. Particularly, mothers (69.6%) exhibited more hesitancy compared to fathers (30.4%). This finding was similar to previous studies conducted in China, Hong Kong, and Saudi Arabia [26–28]. However, this contrasts with the study of Katatbeh M. et al., 2022, which concluded that fathers have a higher tendency to vaccinate [16]. Potential explanations include differing risk perceptions, mothers’ greater daily health involvement, and differing exposure to misinformation [25]. Generational divides also emerge, with parents above 50 significantly more willing to vaccinate their children (78%) compared to younger parents (22%). This could be attributed to varying levels of exposure to previous vaccination campaigns or evolving information landscapes. The study further revealed that higher education levels were associated with lower willingness to vaccinate. This finding is also found in two systematic reviews on COVID-19 parental vaccine hesitancy, which attributed the reasons for increased vaccine hesitancy among parents with higher education to increased access to information, including misinformation [23, 29]. Religion emerges as another factor influencing parental decisions. Christian parents, in the study, exhibited lower vaccination rates compared to Muslim parents. This may depict the effect of religious beliefs on vaccine acceptance, which can be influenced by religious leaders and endorsements, or could be just an association rather than causation. Similar findings of an association between religion and vaccine acceptance were found in Ghana and Thailand [30, 31]. In Ghana, it was concluded that vaccine acceptance can be enhanced by encouraging vaccination through religious leaders and understanding parents’ cultural beliefs [31]. In Thailand, attitudes towards mass vaccination varied depending on religious beliefs, with Muslim parents being more likely to vaccinate their children [30]. Notably, social media and physicians were identified as the primary information sources for parents regarding the COVID-19 vaccine (49.2% and 48.6%, respectively). Similarly, Rubin et al. demonstrated that media exposure differentially influenced preventive behaviors during the swine flu pandemic, increasing hygiene practices while discouraging social distancing and healthcare consultation [32].

The generally mild presentations of COVID-19 in the pediatric age group combined with the less- than-assertive WHO recommendations, when compared to the universal vaccination advocated by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC [33, 34], for pediatric COVID-19 vaccination are paralleled by high rates of hesitancy among parents. Recent systematic review and meta-analysis studies highlighted the challenges in LMICs that resemble those from our study, in regard to childhood COVID-19 vaccination [8, 9]. Additionally, studies done in China and Jordan also demonstrated such challenges [10, 11]. However, in studies done in higher-middle income countries, such as Brazil, parental hesitancy to vaccinate children was noted to be very low, and parents who were hesitant were still more likely to vaccinate their children highlighting the disparities within LMICs, though these studies were conducted during different stages of the pandemic [12].

The current study clearly shows that there remains a significant gap in parental education regarding the safety, efficacy, and need for pediatric COVID-19 vaccination. This gap has not been narrowed after three years of the pandemic and around two years of real-world vaccine experience and evidence for safety and efficacy [35]. Parents in LMICs need further education about the risks of COVID-19 in unvaccinated children, including increased disease severity or long-COVID syndrome as well as the safety of these vaccines that are being administered worldwide on millions of children.

This study from Lebanon provides a roadmap for public health efforts in LMICs to address parental hesitancy. Educational campaigns should emphasize the safety and efficacy of vaccines, discuss mild side effects, and educate parents about the risks of COVID-19 in children [36]. Through engagement with community leaders and healthcare professionals, LMICs can navigate the landscape of parental hesitancy and work towards achieving robust childhood vaccination coverage for a safer future.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are numerous. It grants insight into parental attitudes and concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccination of their children and whether they changed towards the end of the 3-year pandemic. We tried to avoid information bias by using the Arabic version of the CRF completed by highly qualified investigators through a face-to-face interview with the subjects so the degree of bias usually resulting from self-completed questionnaires due to misunderstanding of the questions was declined. In addition, although social desirability bias cannot be entirely avoided, our survey’s questions were kept neutral, and questions were worded in a way that participants did not feel there was either an acceptable or unacceptable response.

The limitations of our study are due to its convenience sampling. Although the capital of Lebanon, Beirut, claims only 7.1% of residents (341,700/4,842,500); however, it has the largest catchment area, around 2,000,000, due to the presence of major tertiary care centers. Despite this, our study could not be representative of the overall population of Lebanon. In addition, our survey included a question on who had encouraged parents to vaccinate their children. However, it did not ask what the main reasons for vaccine acceptance were, as a study in KSA did [37].

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite a two-year experience with pediatric COVID-19 vaccination, hesitancy remained high among parents in Lebanon. Parental hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination, whether early or late in the pandemic, was influenced by consistent factors such as socio-cultural beliefs, religious values, and the availability of accurate, evidence-based information. This study revealed that although some parents strongly accept the COVID-19 vaccination of their children to protect them from the virus, others are more hesitant. Importantly, it highlighted how essential it is for healthcare professionals to support parents in making informed vaccination decisions to increase vaccination rates. Through the increased understanding of the vaccination landscape granted by this study, public health authorities and policymakers are encouraged to implement measures to offset misinformation and work collaboratively to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on children’s health and well-being in Lebanon and beyond.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Arabic and English versions of the survey

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participating hospitals, all participants, and the physicians who agreed to approach their patients’ parents.

Author Contributions

G.S.D. and S.G. conceptualized the study. R.K., C.F.B., S.K., and M.EM. designed the initial survey questionnaire. S.S., L.A., S.EB., A.B., R.K., M.EM., J.A., M., Y.B., M.K., M.N., Y.Y., M.BG., and D.EH. collected the data. A.B. and M.BG. entered the data. C.F.B., L.A., and S.S. cleaned the data. C.F.B. and L.A. performed the analyses. S.S., L.A., C.R., and C.F.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Consent to Participate

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the parents prior to the interview.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sabine Shehab and Lina Anouti contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023 05 May 2023; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-%282005%29-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29-pandemic

- 3.Yesudhas D, Srivastava A, Gromiha MM. COVID-19 outbreak: history, mechanism, transmission, structural studies and therapeutics. Infection. 2021;49(2):199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharif N, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:714170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson EJ, et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 vaccine in children 6 months to 5 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(18):1673–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter EB, et al. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(1):35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piechotta V, et al. Safety and effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19 in children aged 5–11 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(6):379–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kheir-Mataria AE. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1078009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iqbal MS et al. Vaccine hesitancy of COVID-19 among parents for their children in Middle Eastern Countries-a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Abu-Farha RK et al. Navigating parental attitudes on childhood vaccination in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Health Res. 35(1); 2024:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Alosta MR, et al. Factors influencing Jordanian parents’ COVID-19 vaccination decision for children: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;77:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagateli LE et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and adolescents living in Brazil. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Temsah MH, et al. Parental attitudes and hesitancy about COVID-19 vs. routine childhood vaccinations: a national survey. Front Public Health. 2021;9:752323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Strategic preparedness, readiness and response plan to end the global COVID-19 emergency in 2022. 2022 30 March 2022; Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WHE-SPP-2022.1

- 15.Abou Hassan FF, et al. Response to COVID-19 in Lebanon: update, challenges and lessons learned. Epidemiol Infect. 2023;151:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khatatbeh M, et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: a multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aedh AI. Parents’attitudes, their acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccines for children and the contributing factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bourguiba A, et al. Assessing parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward vaccinating children (five to 15 years old) against COVID-19 in the United Arab Emirates. Cureus. 2022;14(12):e32625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postiglione M, et al. Analysis of the COVID-19 vaccine willingness and hesitancy among parents of healthy children aged 6 months-4 years: a cross-sectional survey in Italy. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1241514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama. 2013 [cited 310 20]; 2013/10/22:[2191-4]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration. COVID-19 Vaccines. 2024; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines

- 22.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines in the United States. 2024; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html

- 23.Khan YH, et al. Barriers and facilitators of childhood COVID-19 vaccination among parents: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:950406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for Children. 2024; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/communication/vaccines-children-teens.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/easy-to-read/vaccines-children-teens.html

- 25.Chen F, He Y, Shi Y. Parents’ and Guardians’ Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel), 2022. 10(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Huang LL, et al. Parental hesitancy towards vaccinating their children with a booster dose against COVID-19: real-world evidence from Taizhou, China. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(9):1006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang X, et al. Relationship between parental acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine and attitudes towards measles vaccination for children: a cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2024;42(24):126068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Qahtani AM et al. Parental willingness for COVID-19 vaccination among children aged 5 to 11 years in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Singh P, et al. Strategies to overcome vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jinarong T, et al. Muslim parents’ beliefs and factors influencing complete immunization of children aged 0–5 years in a Thai rural community: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saaka SA, et al. Child malaria vaccine uptake in Ghana: factors influencing parents’ willingness to allow vaccination of their children under five (5) years. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(1):e0296934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin GJ, Potts HW, Michie S. The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(34):183–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panagiotakopoulos L, et al. Use of COVID-19 vaccines for persons aged ≥ 6 months: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2024–2025. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(37):819–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. COVID-19 disease in children and adolescents: Scientific brief, 29 September 2021. 2021; Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Children_and_adolescents-2021.1

- 35.Olusanya OA, et al. Addressing parental vaccine hesitancy and other barriers to childhood/adolescent vaccination uptake during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Front Immunol. 2021;12:663074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee M, et al. Parental acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination for children and its association with information sufficiency and credibility in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2246624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alhuzaimi AN et al. Exploring determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, uptake, and hesitancy in the pediatric population: a study of parents and caregivers in Saudi Arabia during the initial vaccination phase. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Arabic and English versions of the survey

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.