Abstract

Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) is an indicator of imbalance in lipid metabolism and has been associated with a variety of metabolic diseases. Hand Grip Strength (HGS) is an important indicator for assessing muscle function and overall health. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between NHHR and HGS, with the aim of revealing how lipid metabolism affects muscle strength and may provide an early indication of metabolic health and muscle dysfunction. We collected demographic and clinical data from 6,573 adults aged 20–60 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database from 2011 to 2014.NHHR is defined as the ratio of total cholesterol minus high-density lipoprotein levels (HDL-C) divided by HDL-C. HGS is expressed as relative grip strength and is defined as the sum of the maximum readings for each hand/body mass index ratio. Among the data analysis techniques used in this study were multifactor linear regression, smoothed curve fitting, subgroups, and interactions. There was a negative correlation between NHHR and HGS in the 6573 participants included. After adjusting for all covariates, each unit increase in log2-NHHR was associated with a 0.28 [−0.28 (−0.31, −0.26)] decrease in HGS, and this negative correlation remained stable across subgroups (p < 0.01 for the test of trend). The analyses also identified a nonlinear association between NHHR and HGS with an inflection point of 1.74. Interaction tests showed that the negative correlation between NHHR and HGS differed significantly across age, gender, and stratification by diabetes status. Our study suggests that there may be a negative correlation between HGS and NHHR in adults aged 20–60 years in the U.S. Considering that a decline in HGS is an important manifestation of sarcopenia, it may be relevant to the prevention and control of sarcopenia through close detection and management of NHHR.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-90609-9.

Subject terms: Diseases, Endocrinology, Health care, Risk factors

Introduction

Muscle strength serves as a dependable measure of muscle function, a noticeable loss of muscular strength is, therefore, a key sign for the diagnosis of sarcopenia1, A measure of hand grip strength (HGS) is an indicator of overall muscle strength and represents the simplest and most economical way of assessing muscle mass and function2. HGS declines progressively with age after middle age3, and low HGS is associated with many adverse outcomes including disability, prolonged hospitalization, and mortality4,5. Furthermore, Different diseases have been linked to reduced grip strength, including hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, colorectal cancer, and cognitive impairments6–10. Therefore, there is a clinical need for reliable indicators to explore the underlying factors of HGS loss.

The Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) is an emerging comprehensive metric created to assess the lipid profile of atherosclerosis11, consisting of total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL-L). Prior research indicates that Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and chronic kidney disease are better predicted by the NHHR than they were by conventional lipid measurements12–14, Updated research also points to the correlation and unique predictive significance of the NHHR with several diseases, including breast cancer, abdominal aortic aneurysm, diabetes mellitus, depression, and periodontitis15–19.

Both NHHR and HGS provide valuable information in the development of many chronic diseases. A decrease in HGS, as an important indicator of muscle function, is an important manifestation of sarcopenia. The relationship between lipid metabolism and muscle function has been demonstrated in some studies, but the relationship between NHHR and HGS has not yet been reported. Therefore, this study was conducted to explore the correlation between NHHR and HGS by utilizing the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2011 to 2014. In order to provide some community and clinical recommendations for the preventive management of sarcopenia.

Methods

Participants in the NHANES study

This study is based on the official website of NHANES, a publicly available database reviewed and approved by the National Research Ethics Board of the U.S. NHANES is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It is a cross-sectional survey using multistage stratified probability sampling representative of the U.S. noninstitutionalized resident population, with oversampling of specific populations to improve the accuracy of estimates. Data were collected through structured interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests.

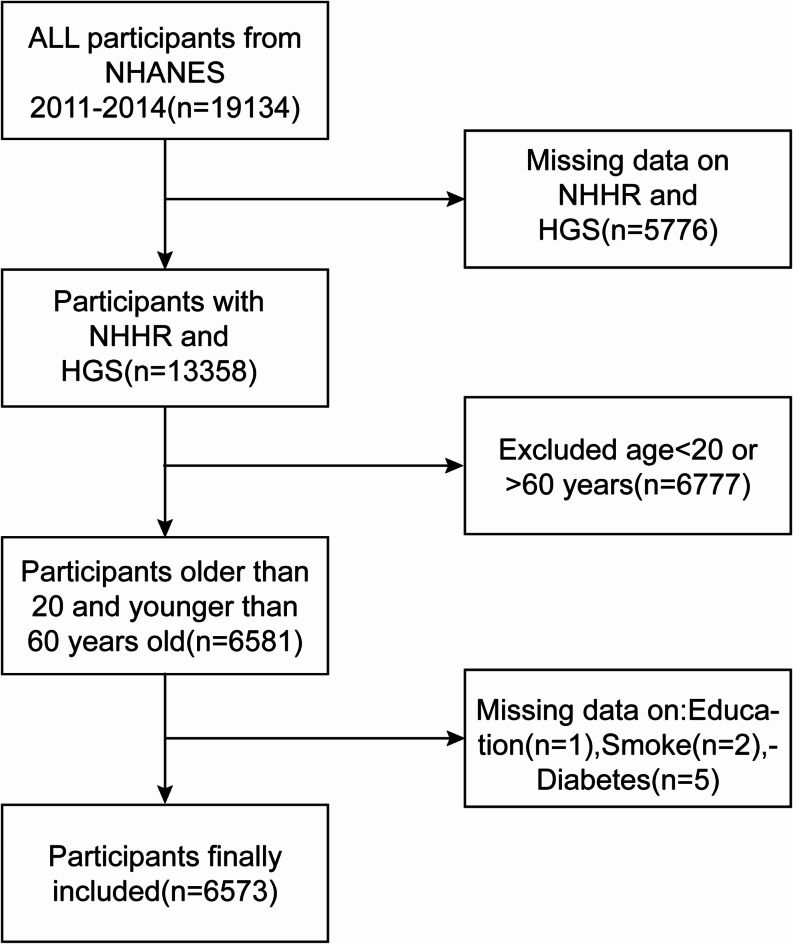

We selected 19,134 individuals from the 2011–2014 NHANES survey for the study. Following the screening process, 6573 participants took part in the study (Fig. 1). We excluded participants lacking complete HGS or NHHR data (5779 people). In addition, we excluded people with incomplete data related to education (1 person), people with incomplete data on smoking (2 people), people with incomplete data on diabetes (5 people), and people under 20 or over 60 years of age (6777 people).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participants selection.

Calculation of NHHR

Blood samples are obtained by venous blood collection and transported under refrigerated conditions to a central laboratory for analysis to ensure sample quality. TC was determined by esterase oxidation, and HDL-C concentration was determined after the separation of the non-HDL-C components by chemical precipitation. The NHANES laboratory strictly follows standardized operating procedures (CLIA) and conducts internal and external quality assessments on a regular basis to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the measurements. In this study, the TC level minus the HDL-C level divided by HDL-C was used to finalize the value of NHHR.

Measurement of the HGS

This study used relative grip strength to represent HGS. Relative grip strength is defined as the sum of the maximum reading of each hand and the body mass index (BMI) ratio20.

Covariates

In addition to NHHR and HGS, our survey also included several other covariates that may influence their relationship, including gender, age, ethnicity, education, marital status, and poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) in demographic data. Moderate activity participation, diabetes status, smoking history, antihyperglycemic treatment (both medication and insulin), and lipid-lowering treatment in the questionnaire data.

Statistical analysis

Data were weighted according to the recommendations of guidelines issued by the CDC. Due to the skewed distribution of the NHHR, a log2 logarithmic transformation was performed and analyzed. First, interquartile division of NHHR was performed and differences were assessed using t-test or chi-square test. Second, we used multiple linear regression to analyze the correlation between NHHR and HGS. Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 was adjusted for gender, age, and race in demographic data, and Model 3 was adjusted for all included covariates. Finally, effect values for different groups were estimated by subgroup analysis, and potential differences between groups were evaluated by interaction tests.EmpowerStats and R software (version 4.1.3) were used for each statistical assessment, with significance levels of P less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 A total of 6573 subjects were enrolled, of which 49.44% were males and 50.56% were females, with a mean age of 39.60 (11.86) years. The mean NHHR and HGS for all participants were 2.97 (1.44) and 2.73 (0.94). Comparing participants’ clinical characteristics by NHHR quartiles, there were significant differences in PIR, HGS, smoking status, diabetes status, participation in moderate activities, education, age, gender, race, marital status, and Antihyperglycemic treatment (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of participants by NHHR among U.S. adults.

| Variables | Total(n) | Q1(%) | Q2(%) | Q3(%) | Q4(%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 3250 | 17.05 | 21.60 | 27.29 | 34.06 | |

| Female | 3233 | 32.44 | 28.59 | 22.48 | 16.49 | |

| Race | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mexican American | 824 | 19.05 | 21.84 | 27.18 | 31.92 | |

| Other Hispanic | 597 | 21.94 | 22.28 | 26.30 | 29.48 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2543 | 23.08 | 23.99 | 25.68 | 27.25 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1485 | 31.45 | 28.08 | 22.15 | 18.32 | |

| Other race | 1124 | 25.80 | 27.76 | 24.11 | 22.33 | |

| Education level | < 0.001 | |||||

| Less than high school | 1207 | 21.46 | 22.37 | 24.03 | 32.15 | |

| High school | 1387 | 20.98 | 23.86 | 28.77 | 26.39 | |

| More than high school | 3979 | 27.19 | 26.41 | 23.75 | 22.64 | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 3207 | 21.08 | 23.73 | 26.85 | 28.34 | |

| No | 3366 | 28.40 | 26.47 | 22.96 | 22.16 | |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 490 | 17.55 | 21.02 | 27.76 | 33.67 | |

| No | 6083 | 25.42 | 25.46 | 24.63 | 24.49 | |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 2636 | 21.55 | 23.41 | 24.58 | 30.46 | |

| No | 3937 | 27.03 | 26.29 | 25.04 | 21.64 | |

| Moderate activity | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 2902 | 26.88 | 26.81 | 24.09 | 22.23 | |

| No | 3671 | 23.21 | 23.81 | 25.47 | 27.51 | |

| Lipid-lowering treatment | 0.068 | |||||

| Yes | 5937 | 21.07 | 24.69 | 25.94 | 28.30 | |

| No | 636 | 25.23 | 25.18 | 24.74 | 24.84 | |

| Antihyperglycemic treatment | 0.047 | |||||

| Yes | 6427 | 23.29 | 19.86 | 21.92 | 34.93 | |

| No | 146 | 24.86 | 25.25 | 24.93 | 24.96 | |

| Age(years) | 37.24 ± 12.15 | 38.96 ± 12.23 | 40.55 ± 11.62 | 41.62 ± 10.95 | < 0.001 | |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 25.78 ± 6.48 | 28.53 ± 7.36 | 30.47 ± 7.48 | 31.30 ± 6.52 | < 0.001 | |

| PIR | 2.58 ± 1.69 | 2.57 ± 1.64 | 2.48 ± 1.58 | 2.36 ± 1.59 | < 0.001 | |

| TC(mmol/L) | 4.32 ± 0.86 | 4.70 ± 0.87 | 5.03 ± 0.85 | 5.77 ± 1.16 | < 0.001 | |

| HDL-C(mmol/L) | 1.74 ± 0.40 | 1.42 ± 0.27 | 1.22 ± 0.21 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | < 0.001 | |

| NHHR | 1.52 ± 0.31 | 2.32 ± 0.21 | 3.13 ± 0.27 | 4.88 ± 1.36 | < 0.001 | |

| HGS(kg/BMI) | 2.83 ± 0.93 | 2.72 ± 0.97 | 2.66 ± 0.95 | 2.71 ± 0.88 | < 0.001 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SEM and p-values were calculated by survey-weighted linear regression analysis. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and p-values were calculated by survey-weighted chi-square tests. PIR poverty-to-income ratio, BMI body mass index, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, NHHR ratio of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HGS hand grip strength, Q quartiles.

Association between the NHHR and HGS

Table 2 We observe a negative correlation between NHHR and HGS. We find that this negative correlation remains stable [−0.28 (−0.31, −0.26)] in the fully corrected model (Model 3), indicating that for every unit increase in log2-NHHR, HGS decreases by 0.28 units. After dividing NHHR into quartiles, the above associations remained statistically significant (p less than 0.01 for all trends). Participants in the highest quartile of NHHR experienced a 0.47-unit decrease in HGS compared with participants in the lowest quartile of NHHR [−0.47 (−0.51, −0.42)].

Table 2.

Association between NHHR and HGS.

| Characteristic | Model 1 [β (95% CI)] | Model 2 [β (95% CI)] | Model 3 [β (95% CI)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log2-NHHR | −0.08 (−0.11, −0.05) < 0.0001 | −0.30 (−0.32, −0.27) < 0.0001 | −0.28 (−0.31, −0.26) < 0.0001 |

| NHHR (quartile) | |||

| Quartile 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Quartile 2 | −0.11 (−0.17, −0.05) 0.0007 | −0.20 (−0.25, −0.16) < 0.0001 | −0.19 (−0.24, −0.15) < 0.0001 |

| Quartile 3 | −0.17 (−0.23, −0.10) < 0.0001 | −0.39 (−0.43, −0.34) < 0.0001 | −0.37 (−0.42, −0.33) < 0.0001 |

| Quartile 4 | −0.11 (−0.18, −0.05) 0.0006 | −0.48 (−0.53, −0.44) < 0.0001 | -0.47 (−0.51, −0.42) < 0.0001 |

| P for trend | 0.0002 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

Model 1: not adjusted for covariates. Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, and race.c Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, PIR, education level, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, moderate activity, lipid-lowering treatment, and glucose-lowering treatment. NHHR the ratio of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Log2-NHHR Log-transformed values of NHHR, β regression coefficient, 95% CI 95% Confidence interval.

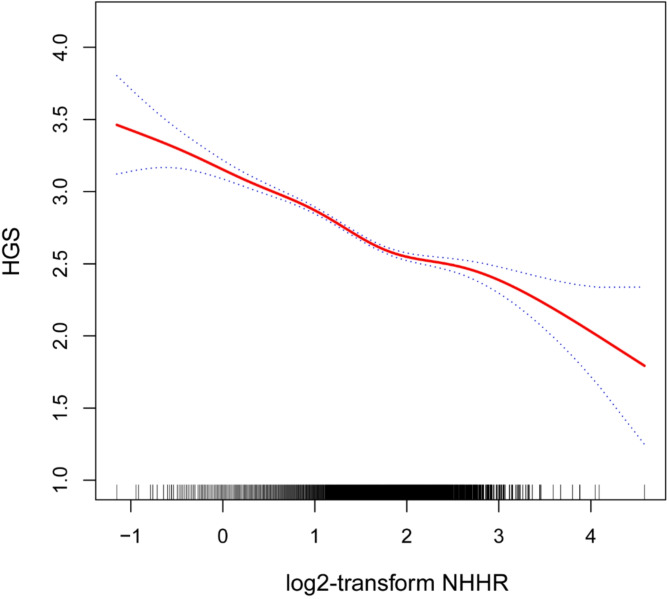

A nonlinear association between the NHHR and HGS

In this study, the nonlinear relationship between NHHR and HGS was verified using smooth curve fitting as in Fig. 2. We further calculated the inflection point to be 1.74. The negative correlation was stronger [-0.34 (-0.37, -0.30)] to the left of the inflection point and weaker [−0.16 (−0.23, −0.10)] to the right of the inflection point, with a log-likelihood ratio test of P < 0.001, as in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

The nonlinear associations between log2-NHHR and HGS.The solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% confidence interval from the fit.

Table 3.

Threshold effect analysis of Log2-NHHR on HGS.

| Model type | log2-NHHR range | Sample size (n) | Adjusted β (95% CI) | P-value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Linear regression | All log2-NHHR | 6101 | −0.28 (−0.31, −0.26) | < 0.0001 | 0.5543 |

| Model 2:Two-piecewise linear regression | log2-NHHR < 1.74 | 4169 | −0.34 (−0.37, −0.30) | < 0.0001 | 0.5815 |

| log2-NHHR > 1.74 | 1932 | −0.16 (−0.23, −0.10) | < 0.0001 | 0.5087 | |

| Log-likelihood ratio test | < 0.0001 |

NHHR the ratio of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, log2-NHHR log-transformed value of NHHR, β regression coefficient, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, R² coefficient of determination.

Subgroup analysis

The present study further analyzed the relationship between NHHR and HGS in different subgroups and showed that they were negatively correlated in all subgroups, but with differences in strength (Table 4). The strongest correlations were found in young people (< 40 years) and men (β = −0.36 and β = −0.32, respectively). Diabetes status showed a significant interaction, with a stronger correlation in non-diabetics (β = −0.30) and a weaker and not statistically significant correlation in diabetics (β = −0.08).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of the association between NHHR and HGS.

| Subgroup | Hand grip strength [β (95% CI)] | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 0.0001 | |

| < 40 | −0.36 (−0.39, −0.32) | |

| ≥ 40 | −0.22 (−0.26, −0.19) | |

| Gender | 0.0025 | |

| Male | −0.32 (−0.36, −0.29) | |

| Female | −0.24 (−0.28, −0.21) | |

| Moderate activity | 0.7210 | |

| Yes | −0.29 (−0.33, −0.25) | |

| No | −0.28 (−0.31, −0.25) | |

| Diabetes status | < 0.0001 | |

| Yes | −0.08 (−0.17, 0.01) | |

| No | −0.30 (−0.33, −0.27) | |

| Smoking | 0.6874 | |

| Yes | −0.29 (−0.33, −0.25) | |

| No | −0.28 (−0.31, −0.25) |

NHHR non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, HGS Hand grip strength, β regression coefficient, 95% CI 95% confidence interval.

Supplementary material 1 In participants aged > 60 years (n = 2620), we similarly analyzed the relationship between NHHR and handgrip strength. The results showed that the correlation remained significant.

Discussion

In this study, the relationship between NHHR and HGS was investigated and the results showed a significant negative correlation. In the fully corrected model, for each unit increase in log2-NHHR, HGS decreased by 0.28 units. Smoothed curve fitting showed a nonlinear relationship between NHHR and HGS with an inflection point of 1.74. Subgroup analyses showed the strongest correlation in young adults and males, while diabetic status significantly weakened the relationship. As grip strength is a sensitive indicator of sarcopenia, the negative correlation between NHHR and HGS may provide a new perspective for the early identification of sarcopenia, suggesting that NHHR may be associated with muscle health as a potential biomarker.

The body’s total lipid metabolism is indicated by the NHHR, which is also thought to be a risk factor for a number of different illnesses. Tan et al.17NHHR is considered a more accurate predictor of diabetes risk than traditional lipid parameters, with 1.50 identified as the optimal threshold for evaluating diabetes risk. Wang et al.21NHHR can be utilized as a straightforward and useful indicator to identify patients at risk of stroke for secondary prevention of the condition because there is a strong link between it and carotid plaque stability. Wang et al.22An ideal inflection point of 6.91 and a negative association are demonstrated by the NHHR, which clarifies the significance of the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Nonetheless, the connection between NHHR and grip strength has not yet been investigated. In a child study, higher amounts of the cardiometabolic marker HDL-C were linked to stronger grips23. It was found in another cross-sectional study involving 17,703 adults that lower HGS was linked to lower HDL-C and other metabolic syndrome components24. Kim et al. The study examined changes in serum lipid and glucose levels in postmenopausal women in relation to grip strength. It found that higher relative grip strength was linked to lower triglycerides (TG) levels and higher HDL-C levels25. Given these findings, it is important to consider the link between lipid levels and the chance of developing sarcopenia.

As we all know, muscle is the largest sugar storage warehouse in the human body, and glucose provides energy for muscle activity. Reduced insulin sensitivity, insulin resistance, and impaired beta cell function can all lead to the inability of muscles to utilize glucose properly to produce energy, which in turn can lead to a loss of muscle strength. Elevated TG leads to an increase in free fatty acids (FFA), and elevated FFA leads to an increase in intracellular diacylglycerol content in myocytes, the increased concentration of which increases the activity of protein kinase C, which in turn weakens intracellular signaling and affects insulin-stimulated glucose transport, and reduces insulin sensitivity26,27. Persistent high FFA status may lead to reduced AMP-activated kinase protein activity and increased TG accumulations28, leading to altered insulin signaling in pancreatic α-cells and excessive glucagon secretion, thus creating a vicious cycle between TG levels and insulin resistance29,30. Excess FFA may produce lipotoxicity, including endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation, with endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducing both reactive oxygen species and inflammation, and oxidative stress-inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress which interferes with the insulin signaling pathway, leading to insulin resistance31. In addition, a decrease in HDL-C concentrations is indicated by rising levels in NHHR, HDL-C enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reverses the inhibitory effect of oxidized LDL-C on insulin secretion, and HDL-C protects β-cells from cytokine- or glucose-induced apoptosis via ApoA1 and S1P, inhibits the activation of the transmembrane protein FAS and increases the expression of FAS-inhibitory proteins Expression of FLIP reduced basal apoptosis, and reduced HDL-C levels affected β-cell function or survival32,33. Elevated NHHR may therefore lead to impaired glucose metabolism, which in turn leads to reduced muscle strength34.

In the present study, we further performed subgroup analyses to show that the negative correlation between NHHR and HGS differed significantly across strata. The strongest correlations were found in young adults (< 40 years) and men, probably because of the more active metabolism in young adults and higher muscle mass in men, making them more susceptible to disorders of lipid metabolism. In the diabetes stratum, the correlation was stronger in non-diabetics and weaker and not statistically significant in diabetics. This phenomenon may be related to irreversible muscle damage caused by long-term metabolic disturbances in diabetics. In addition, the complex metabolic compensation mechanisms or other related complications in diabetic patients may further weaken the direct link between NHHR and HGS. These results suggest that NHHR may be more sensitive in non-diabetic populations and can more accurately reflect the potential effects of lipid metabolism disorders on muscle strength.

The samples in this study were obtained from a sufficiently large and representative official database, and the negative correlation between NHHR and HGS was revealed for the first time, filling the research gap on the association between lipid metabolism and muscle strength. By analyzing NHHR, an indicator of lipid metabolism, the study further suggests that disordered lipid metabolism may be one of the important factors influencing the decline of muscle strength, especially in non-diabetic populations. This finding not only highlights the potential role of lipid metabolism abnormalities in muscle strength loss but also emphasizes NHHR as a valuable clinical marker for early assessment and intervention of the risk of muscle function decline. Clinically, early identification and intervention of NHHR abnormalities may help to delay or prevent the onset of sarcopenia, improve the quality of life in high-risk populations, and reduce the burden of chronic disease associated with muscle function decline. However, because of the lack of time-series data in cross-sectional studies, we can only reveal associations but not determine causality. On the other hand, even though we included many covariates in performing the multivariate regression analyses, there may still be some residual confounding.

Conclusion

HGS decreased significantly with increasing NHHR ratios in people aged 20–60 years, and decreased HGS is an important manifestation of sarcopenia, so monitoring NHHR levels may be of clinical relevance in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants in this study.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- HGS

Hand grip strength

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PIR

Poverty-to-income ratio

- NHHR

The ratio of Non-HDL-C to HDL-C

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TC

TotalCholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- FFA

Free fatty acid

Author contributions

HW and QH designed the research. HW, XF, and XZ collected, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. XZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

The survey data are publicly available on the internet for data users and researchers throughout the world ( www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ ).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The portions of this study involving human participants, human materials, or human data were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing48 (1), 16–31 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens, P. J. et al. Is grip strength a good marker of physical performance among community-dwelling older people? J. Nutr. Health Aging16 (9), 769–774 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohannon, R. W. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther.31 (1), 3–10 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts, H. C. et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing40 (4), 423–429 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leong, D. P. et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet386 (9990), 266–273 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celis-Morales, C. A. et al. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer outcomes and all cause mortality: prospective cohort study of half a million UK biobank participants. Bmj361, k1651 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie, H. et al. Comparison of absolute and relative handgrip strength to predict cancer prognosis: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Clin. Nutr.41 (8), 1636–1643 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mey, R. et al. Handgrip strength and respiratory disease mortality: Longitudinal analyses from SHARE. Pulmonology (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Liu, W. et al. The association of grip strength with cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality in people with hypertension: findings from the prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology China Study. J. Sport Health Sci.10 (6), 629–636 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang, J. et al. Association between grip strength and cognitive function in US older adults of NHANES 2011–2014. J. Alzheimers Dis.89 (2), 427–436 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu, L. et al. Lipoprotein ratios are better than conventional lipid parameters in predicting coronary heart disease in Chinese Han people. Kardiol. Pol.73 (10), 931–938 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang, S. et al. Association between the non-HDL-cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese children and adolescents: a large single-center cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis.19 (1), 242 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, S. W. et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol is a better predictor of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance than apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1. Int. J. Cardiol.168 (3), 2678–2683 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuo, P. Y. et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio as an independent risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis.25 (6), 582–587 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo, X., Ye, J., Xiao, T. & Yi, T. Exploration of the association of a lipid-related biomarker, the non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR), and the risk of breast cancer in American women aged 20 years and older. Int. J. Surg. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lin, W. et al. Association between the non-HDL-cholesterol to HDL- cholesterol ratio and abdominal aortic aneurysm from a Chinese screening program. Lipids Health Dis.22 (1), 187 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan, M. Y. et al. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with type 2 diabetes mellitus: recent findings from NHANES 2007–2018. Lipids Health Dis.23 (1), 151 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou, K., Song, W., He, J. & Ma, Z. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and prevalence of periodontitis among US adults: a cross-sectional NHANES study. Sci. Rep.14 (1), 5558 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi, X. et al. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and risk of depression among US adults: a cross-sectional NHANES study. J. Affect. Disord.344, 451–457 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang, S., Moon, M. K., Kim, W. & Koo, B. K. Association between muscle strength and advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a Korean nationwide survey. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle11 (5), 1232–1241 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, A. et al. Non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio is associated with carotid plaque stability in general population: a cross-sectional study. Front. Neurol.13, 875134 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, J., Li, S., Pu, H. & He, J. The association between the non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and the risk of osteoporosis among U.S. adults: analysis of NHANES data. Lipids Health Dis.23 (1), 161 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blakeley, C. E., Van Rompay, M. I., Schultz, N. S. & Sacheck, J. M. Relationship between muscle strength and dyslipidemia, serum 25(OH)D, and weight status among diverse schoolchildren: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pediatr.18 (1), 23 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu, H. et al. Handgrip strength is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome and its separate components in middle aged and older adults: a large-scale population-based study. Metabolism93, 61–67 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, Y. N., Jung, J. H. & Park, S. B. Changes in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels and metabolic indices according to grip strength in Korean postmenopausal women. Climacteric25 (3), 306–310 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manell, H. et al. Hyperglucagonemia in youth is associated with high plasma free fatty acids, visceral adiposity, and impaired glucose tolerance. Pediatr. Diabetes20 (7), 880–891 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai, M. et al. Elevated midtrimester triglycerides as a biomarker for postpartum hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes. J. Diabetes Res.2020 3950652. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Benito-Vicente, A. et al. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol.359, 357–402 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasram, M. M. et al. Lipid metabolism disturbances contribute to insulin resistance and decrease insulin sensitivity by malathion exposure in Wistar rat. Drug Chem. Toxicol.38 (2), 227–234 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotronen, A. et al. Serum saturated fatty acids containing triacylglycerols are better markers of insulin resistance than total serum triacylglycerol concentrations. Diabetologia52 (4), 684–690 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sears, B. & Perry, M. The role of fatty acids in insulin resistance. Lipids Health Dis.14, 121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Bartolo, B. A. et al. HDL improves cholesterol and glucose homeostasis and reduces atherosclerosis in diabetes-associated atherosclerosis. J. Diabetes Res.2021 6668506. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Sposito, A. C. et al. Reciprocal multifaceted interaction between HDL (high-density lipoprotein) and myocardial infarction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol.39 (8), 1550–1564 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taha, M. et al. Impact of muscle mass on blood glucose level. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol.33 (6), 779–787 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The survey data are publicly available on the internet for data users and researchers throughout the world ( www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ ).