Abstract

Background

Nowadays, nurses face many situations in practice that make them suffer from moral distress and ethical dilemmas, which in turn may reduce their job satisfaction and increase the risk of burnout. This research studied the moral sensitivity of nurses working in teaching hospitals in Zanjan, Iran, and analyzed its relationship with their job satisfaction and burnout.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out in the year 2023 on 261 nurses who were chosen through systematic random sampling. Tools for data collection included Minnesota Satisfaction Scale, Maslach Burnout Inventory, and Lutzen's Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire. The obtained data were analyzed through SPSS-26 using descriptive and inferential statistics. Significance level was considered less than 0.05 for all variables.

Results

The moral sensitivity of subjects had a moderate degree in 71% of the respondents. Similarly, in 71.6%, the degree of job satisfaction was found to be moderate, but a high percentage showed burnout. No significant correlations were found between moral sensitivity and either job satisfaction or burnout. However, an interesting negative correlation was observed between job satisfaction and burnout. Among the demographic variables, age and working ward were observed to be related significantly with moral sensitivity (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

The findings showed that nurses had high levels of burnout besides having average moral sensitivity and job satisfaction. Moral sensitivity is highly correlated with age and work ward; therefore, young nurses and those working in high-stress and specialized departments need special attention.

Keywords: Moral Sensitivity, Job Satisfaction, Burnout, Moral Distress, Nurses, Nursing, Teaching Hospitals

Background

Among health systems, it has become impossible to do without nurses. The quality of care is dependent on the clinical competence of the nursing staff [1]. Moral sensitivity is considered one of the main components of professional competence in a nurse, and it is defined as the ability to identify and evaluate the moral dimension of care situations [2–4]. It is essential that nurses feel equipped to practice their profession in accordance with ethical principles [5]. However, nurses frequently face complex care situations that demand autonomous decision-making under strict time constraints. Given that holistic patient care encompasses physical, psychological, relational, social, moral, and spiritual dimensions, moral sensitivity is indispensable for navigating these ethical challenges effectively [6].

As a psychological concept, previous studies indicate that ethical sensitivity has a complex relationship with different occupational and demographic factors [7–11]. For instance, some research has found a significant link between ethical sensitivity and variables such as age [10], work experience [11], and hospital department [7]. However, considering the critical role of ethical sensitivity in delivering comprehensive and quality nursing care, further research is needed to explore its various dimensions.

Moral sensitivity is important, but nurses are also prone to burnout, which is characterized by low energy, cynicism, and decreased productivity [1]. Burnout is characterized by unfavorable attitudes toward work, feelings of tiredness, and greater mental distance from the job as a result of prolonged professional stress that has not been effectively controlled [12]. Apart from injuring the professional life of nurses, this malady increases absenteeism, turnover ratio, and sickness absences [13]. Moreover, burnout of nursing may have severe negative impacts on an individual's sleep, irritability, sadness, cardiovascular diseases, substance abuse, as well as productivity level [14]. Patient mortality, failure to rescue, and extended hospital stays are associated with higher risks in healthcare organizations where burnout among nursing staff is widespread [15].

Another factor influencing nurses' well-being and the quality of care is job satisfaction, which reflects employees' favorable views and positive attitudes toward their work [16, 17]. In nursing, job satisfaction and a positive attitude are especially crucial for achieving optimal patient outcomes; it is essential for nurses to be satisfied with their jobs and possess the necessary competencies to provide quality healthcare services [16]. Additionally, retention rates heavily depend on job satisfaction [7, 18]. Satisfied nurses are more likely to be enthusiastic, productive, and offer better care to patients [19]. Conversely, job dissatisfaction can lead to higher absenteeism and turnover rates, as well as lower-quality care [10]. Unfortunately, many nurses experience job dissatisfaction, which can result in burnout and moral distress, ultimately impairing patient outcomes [20].

Given the importance of ethical sensitivity, burnout, and job satisfaction in delivering comprehensive and quality patient care, some researchers and experts believe that understanding the interaction among these three variables is essential for developing strategies to enhance nurses' well-being and improve patient care outcomes [21].

Previous studies examining the relationship between moral sensitivity, burnout, and job satisfaction have measured the correlations among these variables in pairs, leading to contradictory findings. For instance, the study by Yilmaz et al. [22] found a significant positive relationship between moral sensitivity and burnout, while Palazoglu and Koc [21] identified a weak negative relationship. Additionally, Palazoglu and Koc [21], Saritas et al. [8], Kulakac and Uzun [23], and Jang and Oh [24] explored the link between moral sensitivity and job satisfaction, reporting an absence of a significant relationship, a negative correlation, and a positive relationship, respectively.

Considering the points mentioned above, the present study was conducted with three objectives: 1. To investigate the levels of moral sensitivity, burnout, and job satisfaction among the participating nurses; 2. To determine the relationships between moral sensitivity, burnout, and job satisfaction; and 3. To evaluate the predictability of moral sensitivity based on burnout, job satisfaction, and various demographic variables.

Methods

Design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in three large teaching hospitals from 14 May to 20 September 2023.

Participants

Selection of participants would include currently working nurses with at least 3 months of experience; having a diploma degree or higher in nursing was an inclusion criterion. To determine sample size, two formulas were used. Formula 1 was used for descriptive purposes only, while Formula 2 was used to estimate the minimum sample size for analytical purposes. Based on these calculations, the largest estimated sample size was set as the minimum required sample size: 208 out of 790 employed nurses.

The table of random numbers was used to select the sample using a systematic random sampling method. The researchers listed all the nurses in the targeted hospitals and designated a number for each nurse to create a sampling frame. To allow for incomplete questionnaires, 10% was added to the calculated sample size, and the total sample accounted for 280 nurses. In total, 280 questionnaires were distributed; after rejecting incomplete and unreturned ones, 261 questionnaires could be regarded as valid for analysis.

Measurements tools

Data were collected using four questionnaires.

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire gathered personal and occupational information including age, gender, education, marital status, employment type, work shift, position, hospital ward, secondary job, adequacy of monthly income, and professional experience.

Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire (MSQ)

Lützén et al. original version of MSQ developed in 1994, and had 30 items [25]. After cultural adaptation, 5 items have been deleted, and a 25-item version with a 5-point Likert scale has been used. Until now, the Persian version of MSQ has been in extensive use, and its validity has also been verified through Iranian researchers. The MSQ comprises six subscales: modifying autonomy, patient-oriented care, professional responsibility, moral conflict, moral meaning, and benevolence. The score range is 0–100, with 0–50 indicating low moral sensitivity, 51–75 moderate, and 76–100 high. The Cronbach’s alpha for the MSQ in this study was 0.84.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

This tool, designed by Maslach and Jackson in 1981, refers to a measure of job burnout across three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement. This is a 22-item test with statements scored on a scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 6 (Every day). Higher scores in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and lower scores in personal achievement mean higher states of burnout. The Cronbach's alpha in this study for the Persian version of MBI was 0.8.

Minnesota Satisfaction Scale (MSS)

The short form of the MSS contains 20 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied), with total scores ranging from 20 to 100. The Persian version of the MSS, validated in previous studies, was used. The Cronbach’s alpha for the MSS in this study was 0.86.

Procedure

The lists of nursing staff were obtained from hospital administrations after getting the permissions. A sampling frame was developed in which participants were randomly (systematic) selected. The selected nurses were informed about the purpose of the study, and then the questionnaires were handed over to them. A total of 261 completed questionnaires were included in the final analysis.

Data analyzes

Data analysis was performed with the help of SPSS, version 26. Descriptive statistics have been used to describe the data as mean (standard deviation) and frequency (percentage), whereas Pearson's correlation, independent t-tests, and ANOVA were applied for analyzing the relationship between moral sensitivity and both burnout and job satisfaction. Furthermore, linear regression was conducted for demographic variables and moral sensitivity. The p-value of less than 0.05 has been considered significant.

Results

Participants' demographic information

According to Table 1, of the 261 nurses who participated in the study, 77.7% were female, and the average age of the participants was 31.54 years. The majority of the participants (90.8%) held a bachelor’s degree, and 67.4% were married. In terms of work experience, 47.3% had between 1 and 5 years of experience, and 49.2% were employed as permanent nurses.

Table 1.

Description of participants' characteristics (n = 261)

| Variables | Status | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 202 (77.7) |

| Male | 59 (22.6) | |

| Education | Diploma | 10 (3.8) |

| Bachelor of science | 237 (90.8) | |

| Master of science | 14 (5.4) | |

| Marital status | Single | 82 (31.5) |

| Married | 176 (67.4) | |

| Divorced | 3(1.2) | |

| Types of employment | Permanent | 89 (34.2) |

| Temporary contract | 82 (31.5) | |

| Plan-baseda | 89 (34.2) | |

| Shift | Rotating | 238 (91.1) |

| Fixed | 23 (8.8) | |

| Position | Head nurse | 8 (3.0) |

| Staff nurse | 9 (3.4) | |

| Practical nurse | 243 (93.5) | |

| Hospital ward | Surgeries | 42 (16.0) |

| Internal | 62 (23.8) | |

| Intensive care | 59 (22.7) | |

| Emergency | 45 (17.3) | |

| Second job | Yes | 28 (10.0) |

| No | 232 (88.8) | |

| Income satisfaction | Low | 89 (34.0) |

| Average | 154 (59.2) | |

| Much | 17 (6.5) | |

| Age Mean ± SD | 31.75 ± 6.35 | |

| Work experience Mean ± SD | 8.68 ± 6.29 | |

Abbreviation: n Number of participants, SD Standard deviation

aPlan-based nurses are required to serve in the hospital for a two-year period as part of their employment contract

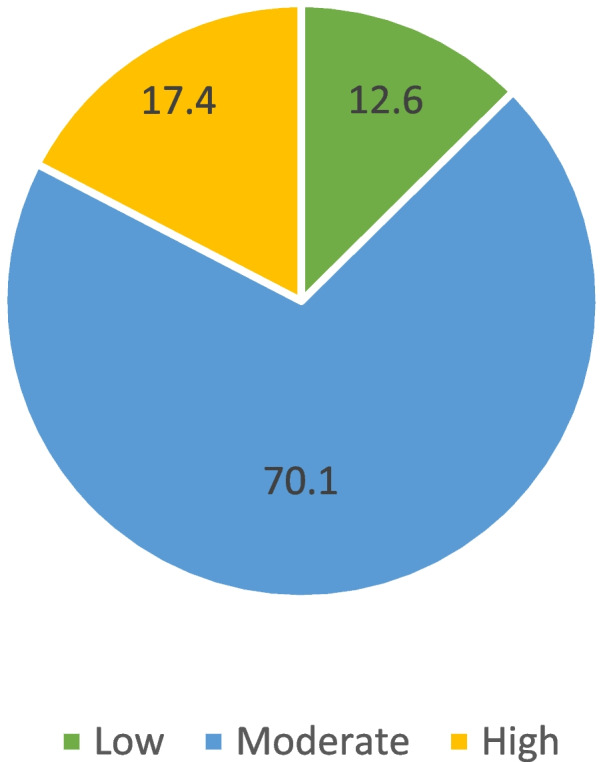

Participants were categorized based on their levels of moral sensitivity, job satisfaction, and different dimensions of job burnout (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Description of moral sensitivity, job satisfaction, and job burnout dimensions

| Variables | Level n (%) | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral sensitivity | Low (0–50) | 33 (12.6) | 11 | 100 | 62.67 ± 14.92 |

| Moderate (50–75) | 183 (70.1) | ||||

| High (75–100) | 45 (17.4) | ||||

| Job satisfaction | Low (20–45) | 49 (18.7) | 14 | 112 | 57.83 ± 13.57 |

| Moderate (45–75) | 187 (71.6) | ||||

| High (75–100) | 25 (9.5) | ||||

| Emotional exhaustion | Low (≤ 17) | 58 (22.2) | 1 | 54 | 25.75 ± 13.75 |

| Moderate (18–29) | 54 (20.6) | ||||

| High (≥ 30) | 149 (57.0) | ||||

| Depersonalization | Low (≤ 5) | 2 (0.76) | 1 | 27 | 12.16 ± 4.98 |

| Moderate (6–11) | 16 (6.1) | ||||

| High (≥ 12) | 243 (93.1) | ||||

| Personal achievement | Low (≥ 40) | 190 (73.1) | 3 | 48 | 29.89 ± 8.69 |

| Moderate (34–39) | 52 (20.0) | ||||

| High (≤ 33) | 18 (6.9) |

Abbreviation: n Number of participants, SD Standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Distribution of moral sensitivity among nurses

The relationship between moral sensitivity, job satisfaction and job burnout dimensions

Pearson correlation analysis showed no significant relationship between nurses' moral sensitivity and burnout or between moral sensitivity and job satisfaction. However, a significant negative relationship was found between burnout and job satisfaction (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between moral sensitivity, job satisfaction and burnout

| Variables | Emotional exhaustion | Personal achievement | Depersonalization | Moral sensitivity | Job satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | r = 1 |

r = 0.072 p = 0.246 |

r = 0.357** p = 0.000 |

r = −0.017 p = 0.784 |

r = −0.540** p = 0.000 |

| Personal achievement |

r = 0.072 p = 0.246 |

r = 1 |

r = 0.246** p = 0.000 |

r = 0.172** p = 0.005 |

r = 0.111 p = 0.074 |

| Depersonalization |

r = 0.35** p = 0.00 |

r = 0.24** p = 0.00 |

r = 1 |

r = 0.040 p = 0.519 |

r = −0.189** p = 0.002 |

| Moral sensitivity |

r = −0.017 p = 0.784 |

r = 0.172** p = 0.005 |

r = 0.040 p = 0.519 |

r = 1 |

r = 0.058 p = 0.354 |

| Job satisfaction |

r = −0.540** p = 0.000 |

r = 0.111 p = 0.07 |

r = −0.189** p = 0.002 |

r = 0.058 p = 0.354 |

r = 1 |

*Correlation was significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Relationship between moral sensitivity of nurses with demographic characteristics

Linear regression analysis indicated a significant relationship between moral sensitivity and both age and hospital ward. No significant relationships were found between moral sensitivity and other demographic variables (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of linear regression test for impact of demographic variables on moral sensitivity

| Predictor Variables | Non-standard coefficient | Standard coefficient | t | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ß | |||

| Age | 1.768 | 0.835 | 0.752 | 2.118 | 0.035 |

| Gender | 0.981 | 2.474 | 0.027 | 0.396 | 0.692 |

| Working experience | −1.564 | 0.807 | −0.660 | −1.937 | 0.054 |

| Marital status | 1.047 | 2.342 | 0.035 | 0.447 | 0.655 |

| Education | 0.363 | 3.142 | 0.007 | 0.115 | 0.908 |

| Type of employment | −0.978 | 0.682 | −0.113 | −1.434 | 0.153 |

| Position | −0.574 | 2.878 | −0.015 | −0.199 | 0.842 |

| Working shift | −0.838 | 3.704 | −0.016 | −0.226 | 0.821 |

| Second job | −3.933 | 2.966 | −0.084 | −1.326 | 0.186 |

| Hospital ward | 1.629 | 0.611 | 0.164 | 2.663 | 0.008 |

| Spouse’s job | −0.1142 | 0.756 | −0.013 | −0.188 | 0.851 |

| Income | −0.823 | 1.519 | −0.034 | −0.541 | 0.589 |

| Dependent variable: Moral sensitivity | |||||

Abbreviations: B Unstandardized beta coefficient, SE Standard error of B, ß Standardized regression coefficient, t Student t test, Sig Statistical significance/p-value

p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the level of moral sensitivity and its correlation with job burnout and job satisfaction among nurses employed in teaching hospitals. The findings indicated that the majority of nurses exhibited moderate moral sensitivity. Yilmaz et al. [22], Darzi-Ramandi et al. [26] and Kobrai et al. [27] found that the majority of nurses had average moral sensitivity, while Khodaveisi et al. [28] presented high levels of moral sensitivity. Such inconsistency may be explained by the difference in setting, sample size, working experience and current ward and place of employment, academic status, age, and personal crises gone through by the participants during the mentioned studies. Determining factors for moral sensitivity were found to be race, gender, sexual orientation, culture, religion, education, and age of the nurses by Ozturk et al. [29]. In our review, no study was found indicating low moral sensitivity in nurses. This could be attributed to the likelihood that individuals with strong adherence to moral principles are drawn to the nursing profession.

In our study, a majority of the participants were found to be experiencing burnout. Yilmaz et al. in Turkey [22] and Behilak and Abdelraof in Egypt [30] also reported high levels of burnout among nurses. Additionally, Quesada-Puga et al. [20], in a review of 18 articles from various countries (2018–2023), and Isfahani [31], in a systematic review of 32 articles from different cities in Iran (2000–2017), reported burnout prevalence rates of 50% and 25% respectively, which were lower than what was observed in our study. In contrast, however, Sadegi et al.'s results in Iran indicated a low level of job burnout [32]. Such differences in results imply the multidimensional feature of job burnout influenced by social, environmental, and cultural factors, as well as managerial ones, working conditions, and patients' condition. Yilmaz et al. have showed that nurses working in COVID epidemic clinics had significantly higher burnout levels than those nurses working in other wards [22]. Quesada-Puga et al. [20] also stated that nurses who perceive effective management as in place have lower prevalence of burnout. Conversely, it was noted that ICU nurses experience higher levels of burnout.

In our study, the levels of depersonalization burnout and personal accomplishment burnout in most nurses were similar to the findings of Behilak and Abdelraof [30] and Portero de la Cruz and Vaquero Abellan [33]. Besides, the level of emotional exhaustion was moderate in our study, and this was also confirmed in the results of Portero de la Cruz and Vaquero Abellan [33]. On the other hand, however, Behilak and Abdelraof [30] reported that higher emotional exhaustion was found for most nurses in their study.

Similar to the findings of Abella [34] in Ascension Arabia and Saritas et al. [8] and Tural Buyuk and Gudek [35] in Turkey, our study also indicated that the majority of participants experienced moderate job satisfaction. On the contrary, the studies in Italy by Sansoni et al. [36] and Egypt by Behilak and Abdelraof [30] reported job satisfaction, which was low, whereas Palazoglu and Koc in Turkey found high job satisfaction [21]. Such inconsistency in findings may emanate from the differences in study settings and the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses.

However, most studies revealed a high prevalence of dissatisfaction among nurses due to lack of independence, undervaluation by the medical staff and nursing management, few professional development opportunities, lack of recognition, minimal encouragement, and absence of teamwork [30].

It's interesting to note that Yilmaz et al.'s study [33] demonstrated a significant positive relationship between moral sensitivity and job burnout, whereas Palazoglu and Koc's study [21] revealed a weak and negative relationship between moral sensitivity and job burnout. In our study, however, we also found no significant correlations between these two variables. It appears that both of these variables may be heavily dependent on contextual factors.

In this study, we found no significant relationship between moral sensitivity and job satisfaction, which aligns with the findings of Palazoglu and Koc [21]. However, this contrasts with the results of Saritas et al. [31], which indicated a negative correlation between job satisfaction and moral sensitivity, as well as the studies of Kulakac and Uzun [23], and Jang and Oh [24], which showed a positive relationship between these two variables. These inconsistent findings suggest that even though moral sensitivity is important, it does not necessarily significantly influence job satisfaction. Job satisfaction seems to be more related to external factors such as organizational conditions and professional status than being solely influenced by internal moral criteria of the nurses themselves [37].

The strong negative relation between job burnout and job satisfaction in this and other similar studies conducted in Spain [20], Egypt [30] and Turkey [21] indicates the necessity of reduction in job burnout. For instance, this can be facilitated by reducing the stressful experiences among the nurses. This emphasizes an important strategy for enhancing job satisfaction and the well-being of nurses. Additionally, there is evidence of a bidirectional and longitudinal relationship between job burnout and job satisfaction. Of course, the longitudinal effects of job burnout on job satisfaction are stronger [38].

Among the demographic variables of our study, only the relationship of age and work ward to moral sensitivity was significant. This significance of age was in agreement with those from Borhani et al. [39] and Farasatkish [40]. With increasing age, nurses have more valuable personal and clinical experiences, and thus they can use sharper methods to overcome complex ethical dilemmas. Regarding the work ward, our findings correspond with those of Izadi et al. [41] and Kim et al. [42], but they are inconsistent with the study of Sadrollahi and Khalili [43]. The variation in moral sensitivity across different wards may be associated with differences in ward climate, the level of exposure to ethical challenges, the conditions of hospitalized patients, and the available technology within each ward.

Although our findings, as well as those of Baloochi et al. [44] and Sadrollahi and Khalili [43], did not demonstrate a significant relationship between moral sensitivity and work experience, some previous studies [45, 46] have reported conflicting results. Arslan and Calpbinici [45] concluded that low professional experience may diminish the ability to address ethical issues. Mohammadi et al. [47] further presented evidence that, with increasing experience, nurses develop more positive attitudes toward ethics, improve their knowledge, and acquire more skills probably due to the result of experience and taking training courses; all these aspects can make them feel more responsible in ethical issues.

It's interesting to note that in our study, other demographic variables such as gender, marital status, level of education, employment status, work position/type of responsibility, type of shift, having a second job and income were not significantly related to moral sensitivity. This is consistent with previous studies [40, 41, 43, 48]. It appears that moral sensitivity is not solely influenced by educational background, job position, or the conditions related to spouse.

Limitations

Considering the context-based nature of the variables examined in this study and their interrelationships, as well as the design of the current study, it may not be feasible to generalize the findings to other societies. Additionally, due to the study's design, it's not possible to infer a cause-and-effect relationship from the results. Furthermore, since moral sensitivity was assessed using a self-report questionnaire, there is a possibility of socially desirable responses.

Conclusion

Based on the study findings, most participants exhibited moderate moral sensitivity and job satisfaction, and experienced job burnout. The impact of moral sensitivity on job satisfaction and burnout appeared to be limited, while burnout played a significant role in diminishing job satisfaction. The only significant relationships among the demographic variables were between age and work ward with moral sensitivity.

These findings impress that the enabling environment in order to enhance moral sensitivity among nurses goes hand in hand with promoting professional competence and, consequently, improves patient care. On parallel lines, an enabling work environment could lower the level of job burnout and improve job satisfaction, adding to the overall well-being of the nurses. The findings suggest that interventions targeted at burnout improvement were relatively more effective in enhancing job satisfaction than focusing on moral sensitivity alone. More attention should also be given to young nurses working in highly demanding and specialized wards, so that moral sensitivity can be developed in this group.

Considering the context-based nature of the variables examined in this study and their interrelationships, as well as the study's design, it may be valuable to conduct additional studies involving nursing communities with diverse contexts and alternative research designs to establish more reliable knowledge in this field.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a research project approved by Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan Iran. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the all the nurses who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- MSQ

Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire

- MBI

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- MSS

Minnesota Satisfaction Scale

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

Authors’ contributions

Study design: KA. Data collection: LH. Data analysis: KA, FR. Study supervision: KA. Manuscript writing: KA, MJ. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: KA, MJ, FR.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Technology Deputy of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran (grant number: A-11–86-21).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research proposal was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (ethical code IR.ZUMS.REC.1399.368). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring their confidentiality and the preservation of their identities throughout the study. We adhered to strict principles of confidentiality, anonymity, and information security. Additionally, ethical standards regarding the use of references were meticulously maintained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Soroush F, Zargham-Boroujeni A, Namnabati M. The relationship between nurses’ clinical competence and burnout in neonatal intensive care units. Iran J Nurs. 2016;21(4):424–9. 10.4103/1735-9066.185596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdollah Zargar S, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E, Kazemnejad A. Moral sensitivity of nursing students: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):99. 10.1186/s12912-024-01713-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraaijeveld MI, Schilderman J, van Leeuwen E. Moral sensitivity revisited. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(2):179–89. 10.1177/0969733020930407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver K. Ethical sensitivity: state of knowledge and needs for further research. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(2):141–55. 10.1177/0969733007073694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biagioli V, Prandi C, Nyatanga B, Fida R. The role of professional competency in influencing job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior among palliative care nurses. Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2018;20(4):377–84. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gastmans C, Schotsmans P, Dierckx de Casterle B. Nursing considered as moral practice: a philosophical-ethical interpretation of nursing. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1998;8(1):43–69. 10.1353/ken.1998.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdullah MI, Huang D, Sarfraz M, Ivascu L, Riaz A. Effects of internal service quality on nurses’ job satisfaction, commitment and performance: Mediating role of employee well-being. Nurs Open. 2021;8(2):607–19. 10.1002/nop2.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saritas SC, Buyukbayram Z, Topdemir EA. Effect of job satisfaction level of nurses on their ethical sensitivity. Annals of Medical Research. 2020;27(2):568–75. 10.5455/annalsmedres.2019.12.882. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Specchia ML, Cozzolino MR, Carini E, Di Pilla A, Galletti C, Ricciardi W, et al. Leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction. Results of a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1552–66. 10.3390/ijerph18041552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stemmer R, Bassi E, Ezra S, Harvey C, Jojo N, Meyer G, et al. A systematic review: Unfinished nursing care and the impact on the nurse outcomes of job satisfaction, burnout, intention-to-leave and turnover. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(8):2290–303. 10.1111/jan.15286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang N, Li J, Xu Z, Gong Z. A latent profile analysis of nurses’ moral sensitivity. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(3):855–67. 10.1177/0969733019876298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization %J Geneva SA. International Classification of Diseases: World Health Organization. 2022.

- 13.Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: a systematic review of 25 years of research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(2):649–61. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyei E, Takyi SA. Burnout, Associated Determinants and Effects among Nurses and Midwives at Selected CHAG Facilities in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana. Research Square. 2024. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3847310/v1.

- 15.Schlak AE, Aiken LH, Chittams J, Poghosyan L, McHugh M. Leveraging the work environment to minimize the negative impact of nurse burnout on patient outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):610. 10.3390/ijerph18020610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alshammari MH, Alenezi A. Nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction: the role of technology integration, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):308. 10.1186/s12912-023-01474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jigjiddorj S, Zanabazar A, Jambal T, Semjid B, editors. Relationship between organizational culture, employee satisfaction and organizational commitment. SHS Web of Conferences; 2021: EDP Sciences. 10.1051/shsconf/20219002004.

- 18.Terera SR, Ngirande H. The impact of rewards on job satisfaction and employee retention. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2014;5(1):481–7. 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n1p481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niskala J, Kanste O, Tomietto M, Miettunen J, Tuomikoski AM, Kyngäs H, et al. Interventions to improve nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(7):1498–508. 10.1111/jan.14342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quesada-Puga C, Izquierdo-Espin FJ, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Aguayo-Estremera R,Cañadas-De La Fuente GA, Romero-Béjar JL, et al. Job satisfaction and burnout syndrome among intensive-care unit nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2024;2024(82):103660. 10.1016/j.iccn.2024.103660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palazoğlu CA, Koç Z. Ethical sensitivity, burnout, and job satisfaction in emergency nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(3):809–22. 10.1177/0969733017720846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yılmaz Ş, Güven GÖ, Demirci M, Karataş M. The relationship between Covid-19 burnout and the moral sensitivity of healthcare professionals. Acta Bioethica. 2023;29(2):229–36. 10.4067/S1726-569X2023000200229. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulakaç N, Uzun S. The effect of burnout and moral sensitivity levels of surgical unit nurses on job satisfaction. J Perianesth Nurs. 2023;38(5):768–72. 10.1016/j.jopan.2023.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang Y, Oh Y. Impact of ethical factors on job satisfaction among Korean nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(4):1186–98. 10.1177/0969733017742959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lützén K, Nordin C, Brolin G. Moral Sensitivity Test. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1994. 10.1037/t60329-000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darzi-Ramandi M, Sadeghi A, Tapak L, Purfarzad Z. Relationship between moral sensitivity of nurses and quality of nursing care for patients with COVID-19. Nurs Open. 2023;10(8):5252–60. 10.1002/nop2.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobrai AF, Mansour GR, Omidzahir S, Poureini M. Moral sensitivity in nurses of Guilan university of medical sciences hospitals: a descriptive study. J Med Ethics. 2021;15(46):1–5.

- 28.Khodaveisi M, Oshvandi K, Bashirian S, Khazaei S, Gillespie M, Masoumi SZ, et al. Moral courage, moral sensitivity and safe nursing care in nurses caring of patients with COVID-19. Nurs Open. 2021;8(6):3538–46. 10.1002/nop2.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Öztürk E, Şener A, Koç Z, Duran L. Factors influencing the ethical sensitivity of nurses working in a university hospital. Eastern Journal of Medicine. 2019;24(3):257–64. 10.5505/ejm.2019.05025. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behilak S, Abdelraof AS-e. The relationship between burnout and job satisfaction among psychiatric nurses. Nurs Educ Pract. 2020;10(10.5430):8–18. 10.5430/jnep.v10n3p8.

- 31.Isfahani PJJH. The prevalence of burnout among nurses in hospitals of Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2019;10(2):240–50. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadeghi A, Shadi M, Moghimbaeigi A. Relationship Between Nurses' Job Satisfaction and Burnout. Sci J Hamadan Nurs Midwifery. 2017;24(4):237–47. 10.21859/nmj-24044.

- 33.Portero de la Cruz S, Vaquero Abellán M. Professional burnout, stress and job satisfaction of nursing staff at a university hospital. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2015;23(3):543–52. 10.1590/0104-1169.0284.2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Abella JL. Determinants of Nurses Job Satisfaction and Quality of Nursing Care among Nurses in Private Hospital Setting. J Patient Saf. 2022;10(1):25–33. 10.22038/PSJ.2022.62942.1349.

- 35.Tural Buyuk E, Rizaral S. Güdek EJPiHS. Ethical sensitivity, job satisfaction and related factors of the nurses working in different areas. 2015;5(1):138–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansoni J, DE CARO W, Marucci A, Sorrentino M, Mayner L, Lancia L. Nurses' Job satisfaction: an Italian study. Ann Ig Medicine Preventivea E Di Comunita. 2016;28(1):58–69. 10.7416/ai.2016.2085. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Hellín Gil MF, Ruiz Hernández JA, Ibáñez-López FJ, Seva Llor AM, Roldán Valcárcel MD, Mikla M, et al. Relationship between job satisfaction and workload of nurses in adult inpatient units. Int J Environ Res Publish Health. 2022;19(18):11701–16. 10.3390/ijerph191811701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figueiredo Ferraz H, Grau Alberola E, Gil Monte PR, García Juesas JAJP. Síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo y satisfacción laboral en profesionales de enfermería. Psicothema. 2012;24(n2):271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Mohamadi E, Ghasemi E, Hoseinabad-Farahani M. Moral sensitivity and moral distress in Iranian critical care nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2017;24(4):474–82. 10.1177/0969733015604700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farasatkish R, Shokrollahi N, Zahednezhad H. Critical care nurses’ moral sensitivity in Shahid Rajaee heart center hospital. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;4(3):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izadi A, Imani E, Khademi Z, Asadi Noughabi F, Hajizadeh N, Naghizadeh F. The correlation of moral sensitivity of critical care nurses with their caring behavior. Iran J Med Eth. 2013;6(2):43–56. 10.1191/0969733005ne829oa. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y-S, Park J-W, You M-A, Seo Y-S. Han S-SJNe. Sensitivity to ethical issues confronted by Korean hospital staff nurses. 2005;12(6):595–605. 10.1191/0969733005ne829oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadrollahi A, Khalili Z. A survey of professional moral sensitivity and associated factors among the nurses in west Golestan province of Iran. Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine. 2015;8(3):50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baloochi Beydokhti T, Tolide-ie H, Fathi A, Hoseini M. Gohari Bahari SJIJoME, Medicine Ho. Relationship between religious orientation and moral sensitivity in the decision making process among nurses. 2014;7(3):48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arslan FT, Calpbinici P. Moral sensitivity, ethical experiences and related factors of pediatric nurses: a cross-sectional, correlational study. Acta Bioethica. 2018;24(1):9–18. 10.4067/S1726-569X2018000100009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goktas S, Aktug C, Gezginci E. Evaluation of moral sensitivity and moral courage in intensive care nurses in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(2):261–71. 10.1111/nicc.12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammadi S, Borhani F, Roshanzadeh M. Moral sensitivity and moral distress in critical care unit nurses. Medical Ethics Journal. 2017;10(38):19–28. 10.21859/mej-103819.

- 48.Shahvali EA, Mohammadzadeh H, Hazaryan M, Hemmatipour A. Investigating the Relationship between Nurses' Moral Sensitivity and Patients' Satisfaction with the Quality of Nursing Care. Eurasian Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 2018;13(3):1. 10.29333/ejac/85009.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.