Abstract

Under the Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic cycle, the cyclization of pent-4-en-1-amine derivatives typically yields either pyrrolidines or piperidines depending on the N-protecting group. We report herein an unprecedented Pd(II)-catalyzed oxidative domino process that converts readily accessible N-protected 2-(2-amidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutane derivatives to 1-fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes. This transformation constructs three chemical bonds under mild conditions [Pd(hfacac)2 (5.0 mol %), Selectfluor (2.0 equiv), MeCN, 60 °C, 10 min] through a domino sequence involving 5-exo-trig amidopalladation/Pd(II)–oxidation/chemoselective dyotropic rearrangement/C–F bond-forming reductive elimination. Notably, the cyclization mode remains independent of the N-protecting group under these conditions. Furthermore, diverse functional groups can be introduced at the bridgehead position of a bicyclic compound via an apparent anti-Bredt bridgehead iminium intermediate.

Introduction

Intramolecular amidopalladation-initiated difunctionalization of alkenes, involving Pd(0)/Pd(II) catalytic cycles, has emerged as a powerful strategy for the synthesis of functionalized azaheterocycles.1−3 This domino process is typically terminated by C–C bond-forming reductive elimination from the R-Pd(II)-Ar intermediate. However, the reluctance of the alkyl-Pd(II)-X complex to undergo Csp3–X bond-forming reductive elimination, coupled with the competitive β-hydride elimination of the same Pd(II) species, has made this approach challenging for the introduction of a second heteroatom across the double bond. Although diamination of 1,3-dienes4,5 and alkynes6 under Pd(0)/Pd(II) and Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalytic conditions, involving Pd(II)-allyl and vinyl-Pd(II) species, respectively, have been successfully achieved, the challenge of Csp3–X bond formation remains. To address this limitation, a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic cycle has been developed, capitalizing on the high-energy Pd(IV) species.7 This strategy exploits the facile C–X reductive elimination from the Pd(IV) intermediate and the strong nucleofugal property of Pd(IV). As a result, various transformations, including aminohalogenation,8 diamination9 and aminoacetoxylation,10,11 of alkenes have been successfully realized.

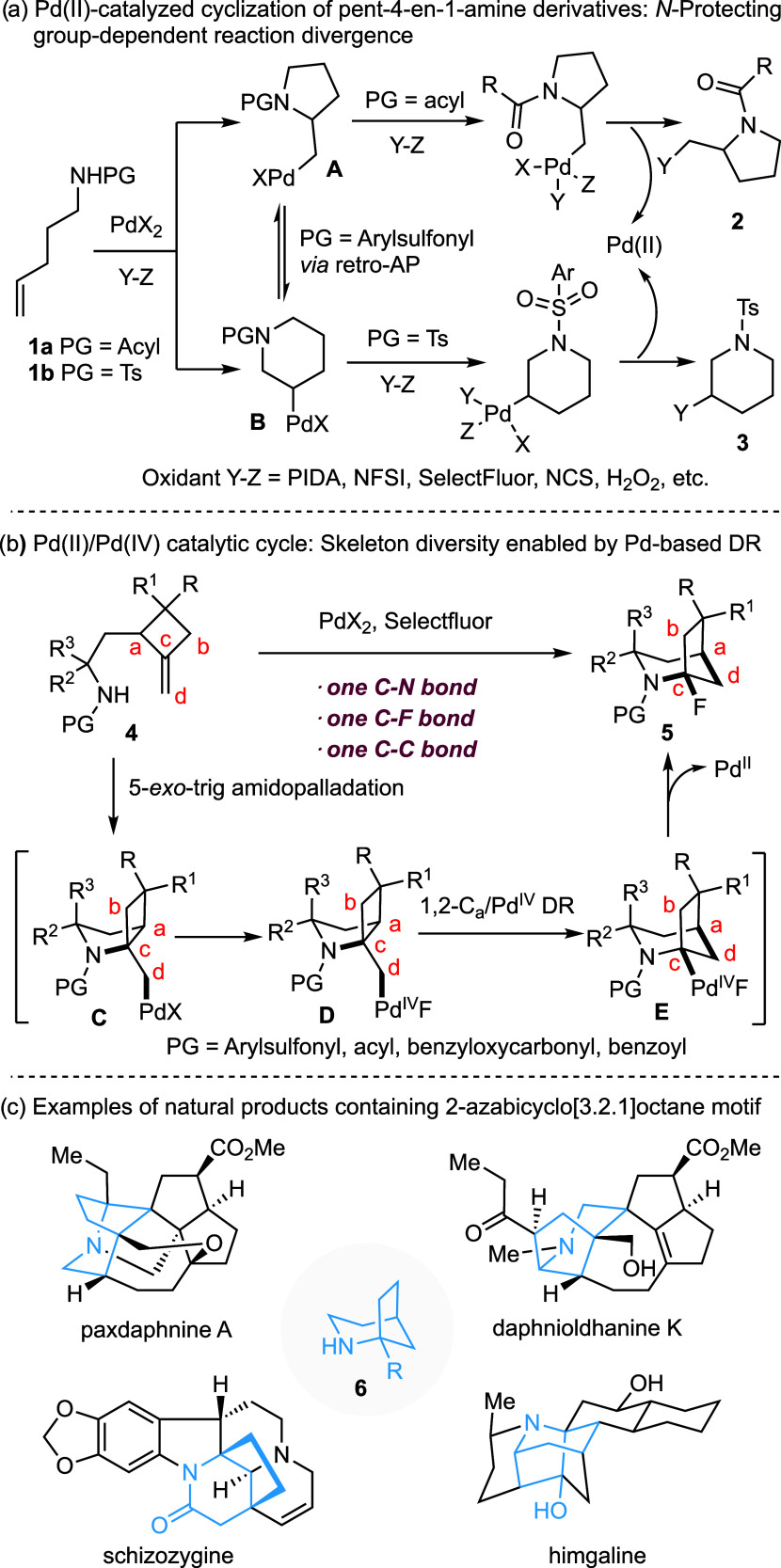

Under the Pd(0)/Pd(II) catalytic cycle, intramolecular amidopalladation (AP) of pent-4-en-1-amine derivatives 1 typically affords functionalized pyrrolidines through a 5-exo-trig cyclization.1−3 Interestingly, under Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic conditions, both 5-exo-trig and 6-endo-trig amidopalladations of 1 have been observed depending on the nature of the N-protecting group. As illustrated in Scheme 1a, the PdX2-catalyzed reaction of N-acylated derivatives 1a (PG = acyl, alkoxycarbonyl, aminocarbonyl) in the presence of an oxidant Y-Z (hypervalent iodine reagent, NFSI, Selectfluor, NCS, H2O2, etc.) afforded pyrrolidines 2.12 In contrast, the corresponding reaction of the N-Ts derivative (PG = Ts) yielded piperidine derivative 3.13 The formation of 2 from 1a is proposed to arise from the kinetically favored 5-exo-trig cyclization of 1a and the stabilizing effect of the aminocarbonyl group on the resulting Pd-complex A (PG = acyl), attributed to its strong chelating ability. Conversely, the reversible amidopalladation of tosylamide 1b(14) and faster oxidation of the more electron-rich secondary alkyl-Pd(II) species B compared to the primary alkyl-Pd(II) complex A are hypothesized to account for the formation of 3 from 1b, assuming that the Pd(II) oxidation was a rate-determining step.15 However, Michael and co-workers have demonstrated that amidopalladation of N-acylated pent-4-en-1-amine derivatives in an intramolecular hydroamination of unactivated alkenes can also be reversible.16

Scheme 1. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Cyclization of Pent-4-en-1-amine Derivatives: Reaction Divergence.

Abbreviations: protecting group (PG), amidopalladation (AP), dyotropic rearrangement (DR), phenyliodine(III) diacetate (PIDA), N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (NFSI), 1-chloromethyl-4-fluoro-1,4-diazoniabicyclo[2.2.2]octane bis(tetrafluoroborate) (Selectfluor), N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS).

We have recently discovered a Pd-based dyotropic rearrangement (DR), in which an in situ formed C–Pd(IV) bond undergoes the σ bond metathesis reaction with the vicinal C–C or C–X bond.17 Subsequently, our group18−20 and others21,22 have developed a series of Pd(II)-catalyzed domino processes incorporating this elementary step. Notably, we demonstrated that the conformational property of the Pd(IV) intermediate played a crucial role in determining the chemoselectivity of the migrating group. For instance, in 5-exo-trig oxypalladation-initiated domino processes, we successfully directed the reaction toward either 1,2-O/Pd(IV)19 or 1,2-C(sp3)/Pd(IV)20 DR, even though heteroatoms are generally known to exhibit higher migratory aptitude in DR reactions.23−26 Intrigued by the aforementioned N-protecting group-depending reaction divergence, we wondered whether dyotropic rearrangement of the Pd(IV) intermediate could be effectively integrated into an amidopalladation-initiated domino process. We report herein that the Pd(II)-catalyzed reaction of N-protected 2-(2-amidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutanes 4 with Selectfluor affords 1-fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes 5 through the concurrent formation of one C–N, one C–F and one C–C bonds. A plausible reaction pathway is outlined in Scheme 1b. A sequence of 5-exo-trig amidopalladation followed by oxidation of the resulting Pd(II) species C by Selectfluor would provide Pd(IV) intermediate D which, upon regioselective 1,2-Ca/Pd(IV) DR, would be converted to E. A C(sp3)-F bond-forming reductive elimination from complex E would generate product 5 with the concurrent regeneration of the Pd(II) catalyst. Notably, this reaction proceeds regardless of the nature of the N-protecting group (sulfonyl or acyl). Furthermore, the reaction of 5 with various nucleophiles affords products 6 via an apparent anti-Bredt bridgehead iminium intermediate.27,28 It is worth noting that the 2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane motif 6 is present in various natural products such as paxdaphnine A,29 daphnioldhanine K,30 schizozygine31 and himgaline32 etc (Scheme 1c).

Results and Discussion

Survey of Reaction Conditions

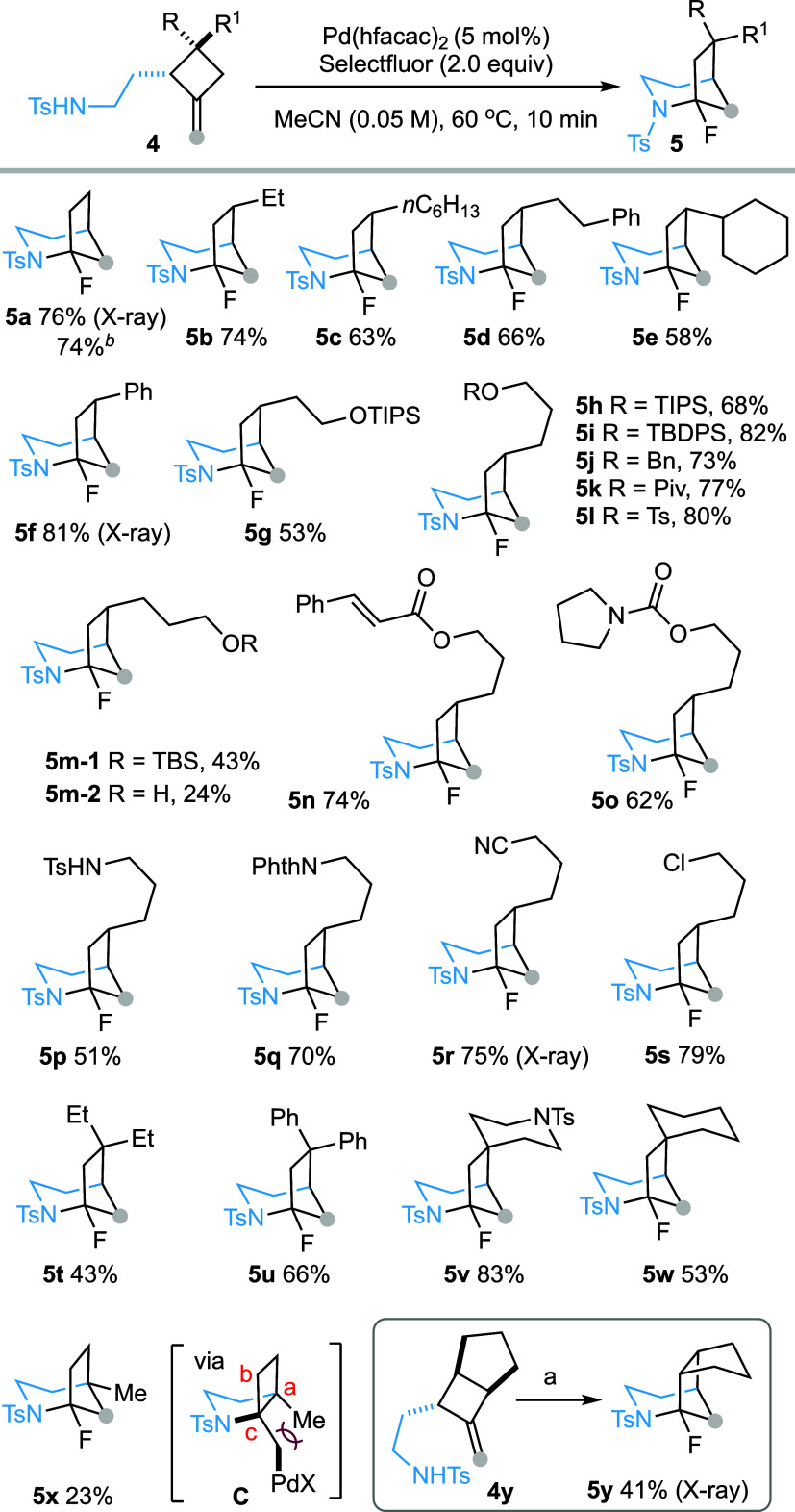

We selected 2-(2-tosylamidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutane (4a) as a test substrate to evaluate the reaction conditions (Scheme 2). Gratifyingly, initial experiments on the PdX2-catalyzed reaction of N-tosyl alkene 4a with Selectfluor revealed the formation of fluorinated 2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane 5a, albeit in a low yield. Encouraged by these preliminary results, the reaction parameters were systematically surveyed by varying the palladium source, solvent, temperature, and reaction time (See Supporting Information). Ultimately, heating an acetonitrile solution of 4a (c 0.05 M) and Selectfluor (2.0 equiv) in the presence of a catalytic amount of Pd(hfacac)2 (5 mol %) at 60 °C for 10 min afforded compound 5a in 76% yield (Scheme 2). The structure of 5a was confirmed by an X-ray crystallographic analysis (CCDC 2417047). Notably, scaling up the reaction to 1 mmol with only 1 mol % of Pd(hfacac)2 still produced 5a in 74% yield, highlighting the practicality of this transformation. It is worth emphasizing that conditions enabling a fast reaction rate are crucial, presumably due to the relative instability of 5a under slightly acidic conditions (vide infra). Control experiments confirmed that both the palladium catalyst and Selectfluor are essential for the conversion of 4a to 5a.

Scheme 2. From Methylenecyclobutanes to 2-Azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes: Scope of Cyclobutane Substitutions.

Reaction performed at 1.0 mmol scale with 1.0 mol % of Pd(hfacac)2, Pd(hfacac)2 = palladium hexafluoroacetylacetonate.

Reaction conditions: 4 (0.1 mmol), Pd(hfacac)2 (5 mol %), and Selectfluor (0.2 mmol) in MeCN (2 mL, c 0.05), 60 °C, 10 min.

Reaction Scope

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand [Pd(hfacac)2 (5 mol %), Selectfluor (2.0 equiv), CH3CN (c 0.05 M), 60 °C], the generality of this reaction was next examined (Scheme 2). The 2,3-trans-3-ethyl-2(2-tosylamidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutane (4b, R = H, R1 = Et) was converted regio- and stereoselectively to 6-ethyl-1-fluor-2-tosyl-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane (5b) in 74% yield. Other 2,3-trans-disubstituted methylenecyclobutanes 4c–4s were similarly transformed to the corresponding bridged bicyclic compounds 5c–5s in good to high yields. The reaction was tolerant of various functional groups, including silyl ethers (TIPS 5h; TBDPS 5i), benzyl ether (5j), pivalate (5k), tosylate (5l), α,β-unsaturated ester (5n), carbamoyl (5o), sulfonamide (5p), phthalimide (5q), nitrile (5r) and alkyl chloride (5s). However, partial deprotection of TBS ether was observed in the cyclization of 4m (R = H, R1 = CH2CH2CH2OTBS) leading to the formation of 5m-1 and 5m-2 in yields of 43 and 24%, respectively. The compatibility of these functional groups provides opportunities for further structural elaborations of the products. In the reaction of 2,3-trans-2-tosylamidoethyl-3-tosylamidopropyl-1-methylenecyclobutane (4p) leading to 5p, no product resulting from participation of the 3-tosylamidopropyl group was observed. The 7-exo-trig-amidopalladation of this sulfonamide group, which would lead to 2-tosyl-2-azabicyclo[4.1.1]octane, was apparently not competitive compared to the 5-exo-trig-amidopalladation of the 2-tosylamidoethyl group, which afforded the 2-tosyl-2-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane scaffold. The reaction is applicable to 3,3-disubstituted 2-(2-tosylamidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutanes, affording the bridged bicyclic products (5t–5w). In contrast, 2,2-disubstituted methylenecyclobutane 4x was converted to bridged bicyclic compound 5x in only 23% yield. We speculate that severe steric clash between Ca-Me and Cc-CH2PdX in the intermediate C may hamper the initial amidopalladation step or favor the equilibrium toward the starting material. Similarly, a diastereomeric mixture of 2-tosylamidoethyl-4-methyl–methylenecyclobutanes was converted into a mixture of two diastereomeric bicyclic compounds in only 28% yield, whereas 2-tosylamidoethyl-1-methylenespiro[3.5]nonane decomposed under the same conditions (cf, Supporting Information). Finally, 2,3,4-trisubstituted methylenecyclobutane 4y was converted to 5y, albeit in moderate yield.

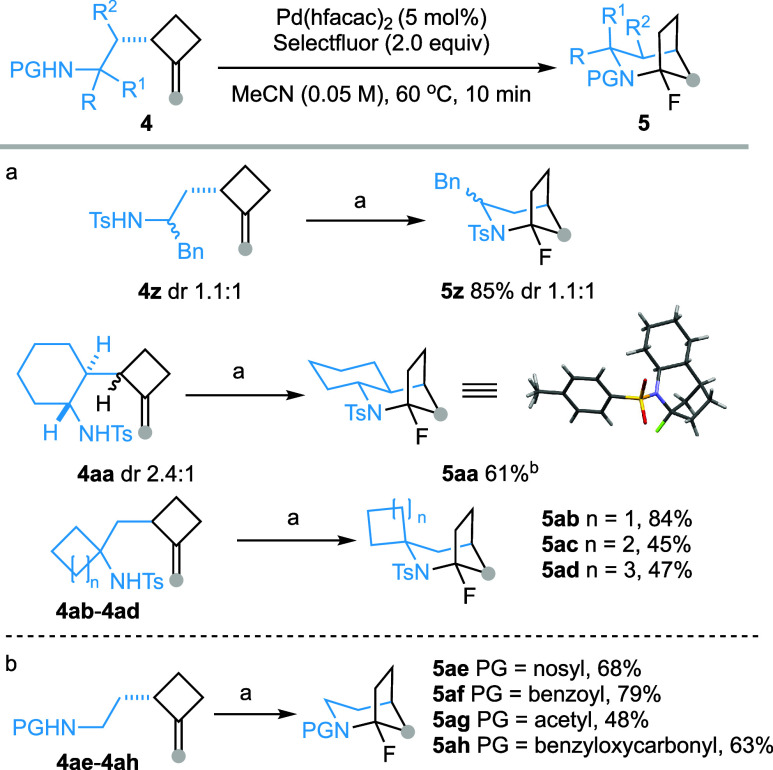

The impact of substitution patterns of the 2-tosylamidoethyl substituent on the reaction outcome was next evaluated. A mixture of two diastereomeric (dr = 1.1:1) α-secondary sulfonamide 4z (R = H, R1 = Bn) was converted into the corresponding aza-bicyclic compound 5z in 85% yield (Scheme 3a). The α,β-disubstituted tosylamide 4aa also underwent the reaction smoothly affording tricyclic compound 5aa. Notably, the α-tertiary sulfonamides proved to be reactive, participating in the reaction to afford 5ab–5ad, which features both bridged and spirocyclic structural motifs. The N-(4-nitrophenyl)sulfonamide (N-nosyl) effectively initiated the reaction, delivering product 5ae in 68% yield (Scheme 3b). Interestingly, benzamide (5af), acetamide (5ag) and carbamate (5ah) displayed reactivity comparable to sulfonamide under the current Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic conditions to furnish the 2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes in good to high yields.

Scheme 3. Scope of Substitutions on Amidoethyl Side Chain.

Only the product resulting from the cyclization of the major diastereoisomer was isolated.

Reagents and conditions: 4 (0.1 mmol), Pd(hfacac)2 (5 mol %), and Selectfluor (0.2 mmol) in MeCN (2 mL, c 0.05), 60 °C, 10 min.

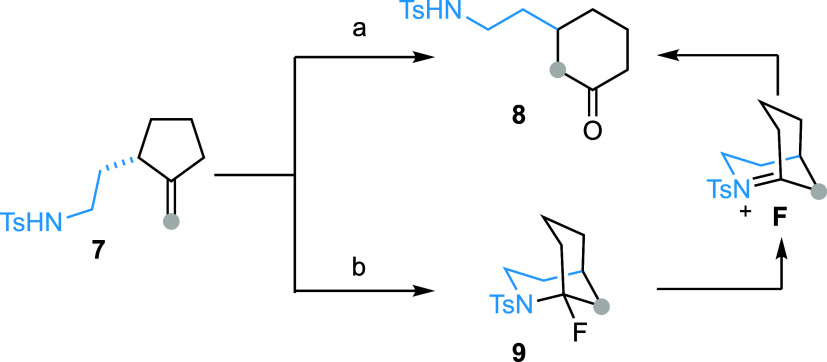

Finally, 2-(2-tosylamidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclopentane (7) was converted to 2-(2-tosylamidoethyl)-cyclohexan-1-one (8) in 70% yield after flash column chromatography on silica gel (Scheme 4). We hypothesized that the same domino process occurred, leading to the formation of 1-fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9). However, this bicyclic compound, bearing an N-sulfonylated α-fluoroamine function, was unstable under acidic conditions. It readily underwent hydrolysis during purification via N-sulfonyliminium ion intermediate F, to afford 8. The formation of bridgehead iminium ion species from 2-aza-bicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes is known to be much easier than that from 2-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octanes 5 (vide supra). On the basis of this assumption, we slightly modified the purification method. Gratifyingly, flash column chromatography of the crude reaction mixture on a basic alumina column allowed us to isolate bridged bicyclic product 9 in 78% yield.

Scheme 4. From Methylenecyclopentane to 2-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane.

Reagents and conditions: 7 (0.1 mmol), Pd(hfacac)2 (5 mol %) and Selectfluor (0.2 mmol) in MeCN (2 mL, c 0.05), 60 °C, 10 min, flash column chromatography on silica gel, 70%.

The same as conditions a, but purification was performed on a basic alumina column, 78%.

Mechanistic Studies

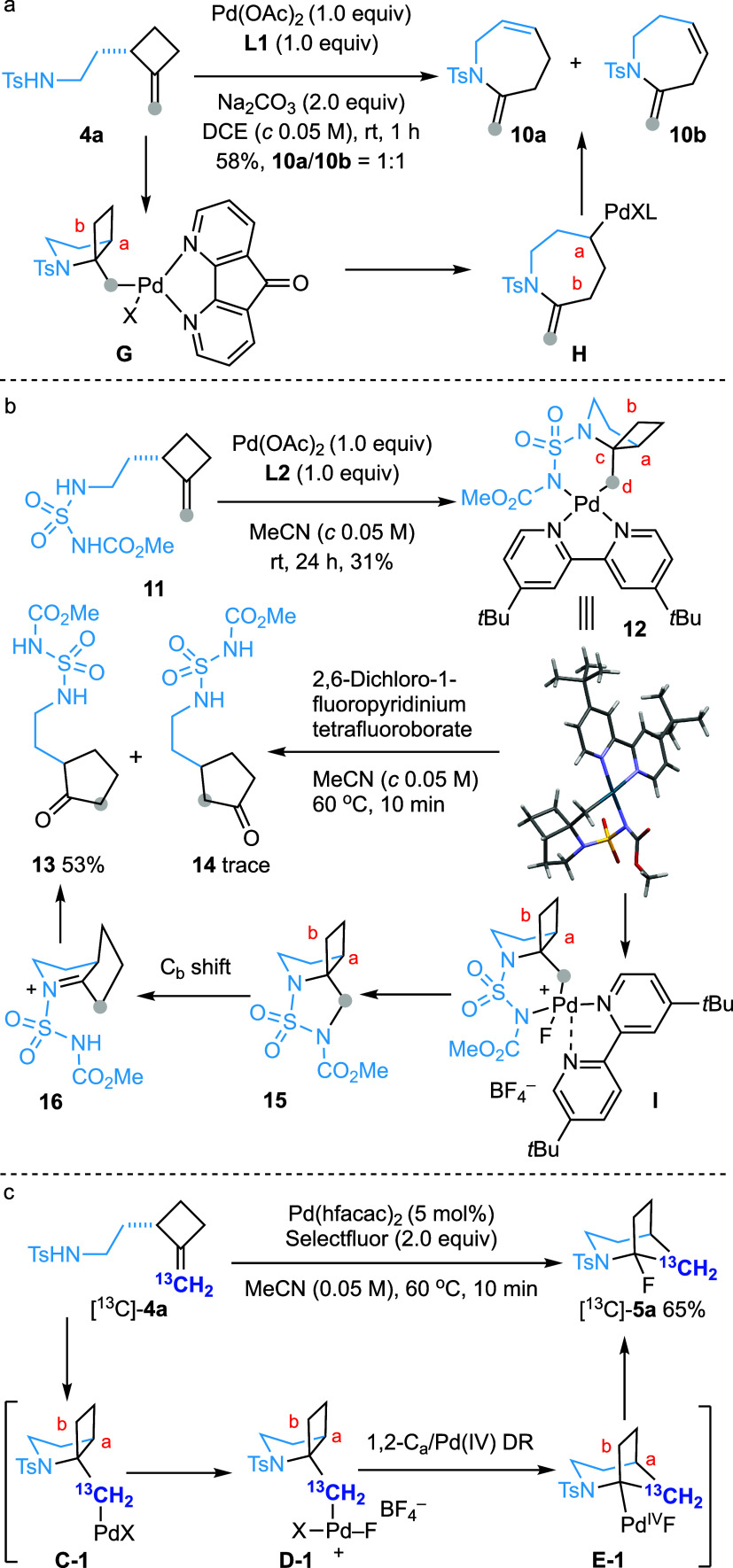

To gain insight into the reaction mechanism of this catalytic transformation, several experiments were carried out (Scheme 5). Preliminary attempts to prepare the Pd(II) complex by reacting 4a with diverse ligands in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of Pd(OAc)2 were unsuccessful. Interestingly, stirring a DCE solution of 4a with one equivalent each of Pd(OAc)2 and 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one (L1) furnished 2-methylene-1-tosyl-tetrahydro-1H-azepines 10a and 10b as a 1:1 mixture in 58% yield (Scheme 5a). This outcome could be rationalized by a 5-exo-trig amidopalladation followed by retro-carbopalladation of the resulting Pd(II) complex G(33) and nonregioselective β-hydride elimination of H, leading to the formation of 10a and 10b.

Scheme 5. Mechanistic Studies.

Pleasingly, the reaction of methyl N-(2-(2-methylenecyclobutyl)ethyl)sulfamoyl)carbamate (11) with Pd(OAc)2 and 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (L2) afforded Pd(II) complex 12, whose structure was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Scheme 5b). Heating a MeCN solution of 12 and Selectfluor provided cyclopentanone derivative 13 in 29% yield, along with a trace amount of 14. Using 2,6-dichloro-1-fluoropyridinium tetrafluoroborate as the oxidant increased the yield of 13 to 53%. In the solid structure of 12, the dihedral angle of Ca-Cc-Cd-Pd is approximately 170°, while that of Cb-Cc-Cd-Pd is 66°. Consequently, if the corresponding Pd(IV) species underwent a dyotropic rearrangement, Ca would be expected to migrate preferentially leading, after hydrolysis, to the formation of 14 as a major product instead of 13. Therefore, an alternative mechanism might be operating. We surmised that the formation of 13 would involve the C–N bond-forming reductive elimination from Pd(IV) intermediate I to generate 15,9 which could then undergo an aza-pinacol rearrangement. In this scenario, Cb migration would be favored over Ca since Ca migration would result in a bridgehead iminium species. Subsequent hydrolysis of 16 would then produce observed product 13.

Finally, submitting compound [13C]-4a, labeled at the terminal sp2 carbon, to the standard conditions afforded [13C]-5a in 65% yield (Scheme 5c). The formation of [13C]-5a is consistent with a reaction sequence involving 5-exo-trig amidopalladation followed by Pd oxidation, chemoselective 1,2-Ca/Pd(IV) dyotropic rearrangement, and C–F bond forming reductive elimination.

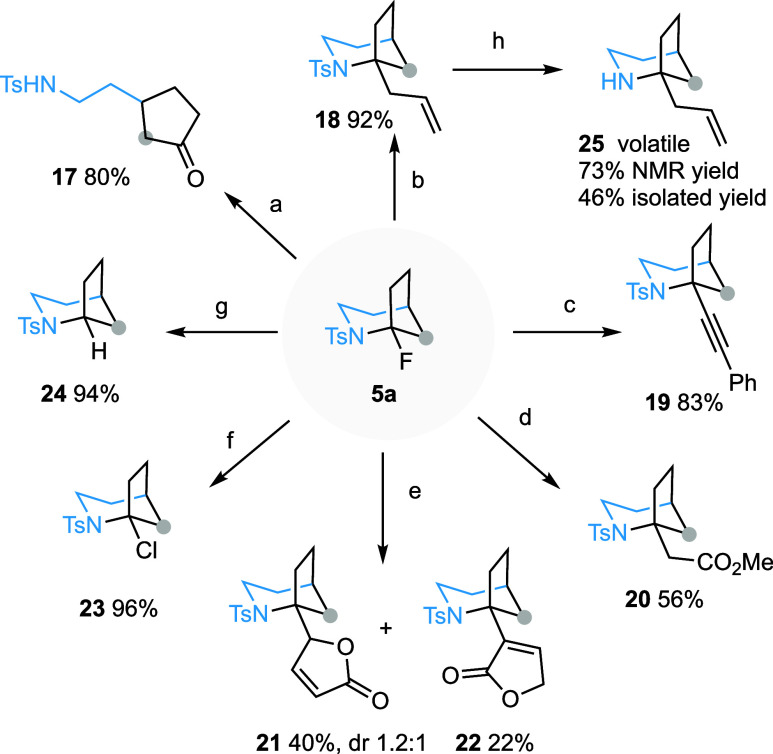

Post-Transformations

The presence of an N-sulfonylated α-fluoroamine function in 1-fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes offers a unique opportunity to introduce diverse functional groups at the C1 position. This is particularly compelling, as all of the natural products depicted in Scheme 1c feature an α-tertiary amine motif. Gratifyingly, stirring a DCM solution of 5a with TFA (5.0 equiv) at room temperature afforded cyclopentanone derivative 17 in 80% isolated yield. The apparent facile generation of the bridgehead iminium species from this bicyclic compound prompted us to exploit the reactivity of this latent electrophilic species.27 As shown in Scheme 6, the BF3·Et2O-promoted reaction of 5a with allylsilane generated the 1-allylated derivative 18 in 92% yield. Similarly, alkynyl group was introduced at the bridgehead position of 19 by employing alkynyltrifluoroborate34 as the nucleophile. When an enol ether was used as the nucleophile, an alkyl group can in turn be introduced at the C1 position of the bicyclic compounds (20–22). In the reaction with 2-(trimethylsilyloxy)furan, two products 21 and 22, resulting from the alkylation of the C-3 and C-5 positions of furan, were generated in the yield of 40% and 22%, respectively. Halogen exchange reactions were also possible. Treating 5a with TiCl4 (2.0 equiv, DCM, 0 °C) afforded 1-chloro derivative 23 in 96% yield. Additionally, reduction of 5a with triethylsilane in the presence of BF3·Et2O delivered 2-tosyl-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane (24) in an excellent yield. Finally, removal of N-tosyl protecting group from 18 was realized under single electron transfer reductive conditions yielding volatile 1-allyl-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane 25.35

Scheme 6. Chemical Transformation of 1-Fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes.

Reagents and conditions: (a) TFA (5 equiv), DCM, rt, 10 h, 80%. (b) BF3·Et2O (3.0 equiv), allyltrimethylsilane (5.0 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, 2.5 h, 92%. (c) BF3·Et2O (3.0 equiv), potassium trifluoro(phenylethynyl)borate (2.0 equiv), TBAB (0.1 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, 1 h, 83%. (d) BF3·Et2O (3.0 equiv), (1-methoxyvinyl)oxy](trimethyl)silane (25 equiv), DCM, rt, 1.5 h, 56%. (e) BF3·Et2O (3.0 equiv), 2-(trimethylsilyloxy)furan (2.0 equiv), DCM, −10 °C, 1.5 h, 40% (dr 1.2:1) for 21, 22% for 22. (f) TiCl4 (2.0 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, 1.5 h, 96%. (g) BF3·Et2O (5.0 equiv), Et3SiH (10.0 equiv), DCM, rt, 2 h, 94%. (h) SmI2 (10.0 equiv), pyrrolidine (20.0 equiv), H2O (30 equiv), THF, rt, 1 h, 46% isolated yield, 73% NMR yield. Abbreviations: TFA = trifluoroacetic acid, DCM = dichloromethane, TBAB = tetrabutylammonium bromide, THF = tetrahydrofuran.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a Pd(II)-catalyzed amidopalladation-initiated domino process that efficiently converts readily accessible N-protected 2-(2-amidoethyl)-1-methylenecyclobutane derivatives 4 to 1-fluoro-2-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes 5. This transformation relies on a ring-expanding, chemoselective 1,2-Csp3/Pd(IV) dyotropic rearrangement. Additionally, the facile generation of the bridgehead iminium intermediate from 5 in the presence of a Lewis acid enabled the successful introduction of diverse functional groups at the bridgehead position of the bicyclic scaffold.

Acknowledgments

We thank EPFL (Switzerland) for financial supports. We thank Dr. F. Fadaei-Tirani and Dr. R. Scopelliti for the X-ray structural analysis of compounds 5a, 5f, 5r, 5y, 5aa and 12.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c01108.

Experimental procedures and characterization data; additional experimental details; crystallographic data of 5a, 5f, 5r, 5y, 5aa and 12; copies of the 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wolfe J. P. Stereoselective Synthesis of Saturated Heterocycles via Palladium-Catalyzed Alkene Carboetherification and Carboamination Reactions. Synlett 2008, 2008, 2913–2937. 10.1055/s-0028-1087339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kočovský P.; Bäckvall J.-E. The syn/anti-Dichotomy in the Palladium-Catalyzed Addition of Nucleophiles to Alkenes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 36–56. 10.1002/chem.201404070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minatti A.; Muñiz K. Intramolecular Aminopalladation of Alkenes as a Key Step to Pyrrolidines and Related Heterocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1142–1152. 10.1039/B607474J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pd(0)-catalyzed diamination of 1,3-dienes, see:; a Du H.; Zhao B.; Shi Y. A Facile Pd(0)-Catalyzed Regio- and Stereoselective Diamination of Conjugated Dienes and Trienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 762–763. 10.1021/ja0680562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Du H.; Yuan W.; Zhao B.; Shi Y. Catalytic Asymmetric Diamination of Conjugated Dienes and Triene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11688–11689. 10.1021/ja074698t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhao B.; Du H.; Cui S.; Shi Y. Synthetic and Mechanistic Studies on Pd(0)-Catalyzed Diamination of Conjugated Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3523–3532. 10.1021/ja909459h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhu Y.; Cornwall R. G.; Du H.; Zhao B.; Shi Y. Catalytic Diamination of Olefins via N–N Bond Activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3665–3678. 10.1021/ar500344t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pd(II) catalyzed diamination of 1,3-dienes, see:; a Bar G. L. J.; Lloyd-Jones G. C.; Booker-Milburn K. I. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Intermolecular 1,2-Diamination of Conjugated Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7308–7309. 10.1021/ja051181d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wu Z.; Wen K.; Zhang J.; Zhang W. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Aerobic Intermolecular 1,2-Diamination of Conjugated Dienes: A Regio- and Chemoselective [4 + 2] Annulation for the Synthesis of Tetrahydroquinoxalines. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2813–2816. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pd-catalyzed diamination of alkynes, see:; a Okano A.; Tsukamoto K.; Kosaka S.; Maeda H.; Oishi S.; Tanaka T.; Fujii N.; Ohno H. Synthesis of Fused and Linked Bicyclic Nitrogen Heterocycles by Palladium-Catalyzed Domino Cyclization of Propargyl Bromides. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 8410–8418. 10.1002/chem.201000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yao B.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Diamination of Alkynes under Aerobic Oxidative Conditions: Catalytic Turnover of an Iodide Ion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 5170–5174. 10.1002/anie.201201640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. I.; Liu G.; Stahl S. S. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Alkene Functionalization via Nucleopalladation: Stereochemical Pathways and Enantioselective Catalytic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2981–3019. 10.1021/cr100371y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni M. R.; Zabawa T. P.; Kasi D.; Chemler S. R. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminobromination and Aminochlorination of Olefins. Organometallics 2004, 23, 5618–5621. 10.1021/om049432z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Streuff J.; Hövelmann C. H.; Nieger M.; Muñiz K. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Diamination of Unfunctionalized Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14586–14587. 10.1021/ja055190y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Muñiz K. Advancing Palladium-Catalyzed C-N Bond Formation: Bisindoline Construction from Successive Amide Transfer to Internal Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14542–14543. 10.1021/ja075655f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Iglesias Á.; Pérez E. G.; Muñiz K. An Intermolecular Palladium-Catalyzed Diamination of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8109–8111. 10.1002/anie.201003653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sibbald P. A.; Michael F. E. Palladium-Catalyzed Diamination of Unactivated Alkenes Using N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide as Source of Electrophilic Nitrogen. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1147–1149. 10.1021/ol9000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexanian E. J.; Lee C.; Sorensen E. J. Palladium-Catalyzed Ring-Forming Aminoacetoxylation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7690–7691. 10.1021/ja051406k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Stahl S. S. Highly Regioselective Pd-Catalyzed Intermolecular Aminoacetoxylation of Alkenes and Evidence for cis-Aminopalladation and SN2 C-O Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7179–7181. 10.1021/ja061706h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rosewall C. F.; Sibbald P. A.; Liskin D. V.; Michael F. E. Palladium-Catalyzed Carboamination of Alkenes Promoted by N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide via C-H Activation of Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9488–9489. 10.1021/ja9031659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sibbald P. A.; Rosewall C. F.; Swartz R. D.; Michael F. E. Mechanism of N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide Promoted Diamination and Carboamination Reactions: Divergent Reactivity of a Pd(IV) Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15945–15951. 10.1021/ja906915w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liskin D. V.; Sibbald P. A.; Rosewall C. F.; Michael F. E. Palladium-Catalyzed Alkoxyamination of Alkenes with Use of N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide as Oxidant. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 6294–6296. 10.1021/jo101171g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ingalls E. L.; Sibbald P. A.; Kaminsky W.; Michael F. E. Enantioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Diamination of Alkenes Using N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8854–8856. 10.1021/ja4043406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wu T.; Cheng J.; Chen P.; Liu G. Regioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Oxidative Aminofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 8707–8709. 10.1039/c3cc44711a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Zhu H.; Chen P.; Liu G. Pd-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminohydroxylation of Alkenes with Hydrogen Peroxide as Oxidant and Water as Nucleophile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1766–1769. 10.1021/ja412023b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Chen C.; Hou C.; Chen P.; Liu G. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Aminotrifluoromethoxylation of Alkenes: Mechanistic Insight into the Effect of N-Protecting Groups. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 346–350. 10.1002/cjoc.201900516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu T.; Yin G.; Liu G. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16354–16355. 10.1021/ja9076588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yin G.; Wu T.; Liu G. Highly Selective Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Chloroamination of Unactivated Alkenes by Using Hydrogen Peroxide as an Oxidant. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 451–455. 10.1002/chem.201102776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu X.; Hou C.; Peng Y.; Chen P.; Liu G. Ligand-Controlled Regioselective Pd-Catalyzed Diamination of Alkenes. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 9371–9375. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chen C.; Chen P.; Liu G. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminotrifluoromethoxylation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15648–15651. 10.1021/jacs.5b10971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Chen C.; Pflüger P. M.; Chen P.; Liu G. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Aminotrifluoromethoxylation of Unactivated Alkenes Using CsOCF3 as a Trifluoromethoxide Source. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2392–2396. 10.1002/anie.201813591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wang Z.; Hou C.; Chen P. Asymmetric Palladium-Catalyzed Aminochlorination of Unactivated Alkenes. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 2685–2690. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wu L.; Chen P.; Liu G. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Aminofluorination of Alkenes in Total Synthesis 6-(R) Fluoroswainsonine and 5-(R)-Fluorofebrifugine. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 960–963. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Hou C.; Chen P.; Liu G. Enantioselective Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Oxidative Aminofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes with Et4NF·3HF as a Fluoride Source. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2735–2739. 10.1002/anie.201913100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Qi X.; Chen C.; Hou C.; Fu L.; Chen P.; Liu G. Enantioselective Pd(II)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Oxidative 6-endo Aminoacetoxylation of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7415–7419. 10.1021/jacs.8b03767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Zhu H.; Chen P.; Liu G. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aminoacetoxylation of Unactivated Alkenes with Hydrogen Peroxide as Oxidant. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1485–1488. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Li X.; Qi X.; Hou C.; Chen P.; Liu G. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Azidation of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17239–17244. 10.1002/anie.202006757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. B.; Stahl S. S. Reversible Alkene Insertion into the Pd–N Bond of Pd(II)- Sulfonamidates and Implications for Catalytic Amidation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18594–18597. 10.1021/ja208560h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G.; Mu X.; Liu G. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Oxidative Difunctionalization of Alkenes: Bond Forming at a High-Valent Palladium Center. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2413–2423. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran B. M.; Michael F. E. Mechanistic Studies of a Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Hydroamination of Unactivated Alkenes: Protonolysis of a Stable Palladium Alkyl Complex Is the Turnover-Limiting Step. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2786–2792. 10.1021/ja0734997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J.; Wu H.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. C–C Bond Activation Enabled by Dyotropic Rearrangement of Pd(IV) Species. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 671–676. 10.1038/s41557-021-00698-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yang G.; Wu H.; Gallarati S.; Corminboeuf C.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Migrative Carbofluorination of Saturated Amides Enabled by Pd-based Dyotropic Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14047–14052. 10.1021/jacs.2c06578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gong J.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Apparent 6-endo-trig Carbofluorination of Alkenes Enabled by Palladium-based Dyotropic Rearrangement. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211470 10.1002/anie.202211470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Feng Q.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Oxidative Rearrangement of 1,1-Disubstituted Alkenes to Ketones. Science 2023, 379, 1363–1368. 10.1126/science.adg3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Feng Q.; Liu C.-X.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Palladium-based Dyotropic Rearrangement Enables A Triple Functionalization of Gem-disubstituted Alkenes: An Unusual Fluorolactonization Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202316393 10.1002/anie.202316393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Delcaillau T.; Yang B.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Editing Tetrasubstituted Carbon: Dual C–O Bond Functionalization of Tertiary Alcohols Enabled by Palladium-Based Dyotropic Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 11061–11066. 10.1021/jacs.4c02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wu H.; Fujii T.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Quaternary Carbon Editing Enabled by Sequential Palladium Migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 21239–21244. 10.1021/jacs.4c07706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Liu C.-X.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Chemoselective Pd-Based Dyotropic Rearrangement: Fluorocyclization and Regioselective Wacker Reaction of Homoallylic Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 30014–30019. 10.1021/jacs.4c13359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Diverting the 5-exo-trig Oxypalladation to Formally 6-endo-trig Fluorocycloetherification Product through 1,2-O/Pd(IV) Dyotropic Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15735–15741. 10.1021/jacs.3c06158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Chemoselectivity in Pd-Based Dyotropic Rearrangement: Development and Application in Total Synthesis of Pheromones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 2077–2085. 10.1021/jacs.4c15764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Wu J.; Tan X.; Zhang J.; Wu W.; Jiang H. Access to Amino Lactones through Palladium-catalyzed Oxyamination with Aromatic Amines as the Nitrogen Source. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 11339–11344. 10.1021/acscatal.3c02864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel-catalyzed, see:Ping Y.; Pan Q.; Guo Y.; Liu Y.; Li X.; Wang M.; Kong W. Switchable 1,2-Rearrangement Enables Expedient Synthesis of Structurally Diverse Fluorine-containing Scaffolds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11626–11637. 10.1021/jacs.2c02487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reetz M. T. Dyotropic Rearrangements, a New Class of Orbital-Symmetry Controlled Reactions. Type I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1972, 11, 129–130. 10.1002/anie.197201291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fernández I.; Cossío F. P.; Sierra M. A. Dyotropic Reactions: Mechanisms and Synthetic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6687–6711. 10.1021/cr900209c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Croisant M. F.; Van Hoveln R.; Schomaker J. M. Formal Dyotropic Rearrangements in Organometallic Transformations. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5897–5907. 10.1002/ejoc.201500561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hugelshofer C. L.; Magauer T. Dyotropic Rearrangements in Natural Product Total Synthesis and Biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 228–234. 10.1039/C7NP00005G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulzer J.; Hoyer K.; Müller-Fahrnow A. Relative Migratory Aptitude of Substituents and Stereochemistry of Dyotropic Ring Enlargements of β-Lactones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1997, 36, 1476–1478. 10.1002/anie.199714761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Ma Y.; Qiu K.; Li B.; Xue Z.; Tian B.; Tang Y. Elucidating the Selectivity of Dyotropic Rearrangements of β-Lactones: a Computational Survey. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 329–341. 10.1039/D1QO01591E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridged head iminium ions from 2-aza-[3.3.1]nonanes, see:Yamazaki N.; Suzuki H.; Kibayayhi C. Nucleophilic Alkylation on Anti-Bredt Iminium Ions. Facile Entry to the Synthesis of 1-Alkylated 2-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes (Morphans) and 5-Azatricyclo[6.3.1.0 1,5]dodecane. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 8280–8281. 10.1021/jo9715579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner P. M. Strained Bridgehead Double Bonds. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1067–1093. 10.1021/cr00095a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C.-Q.; Yin S.; Xue J.-J.; Yue J.-M. Novel alkaloids, Paxdaphnines A and B with Unprecedented Skeletons from the Seeds of Daphniphyllum paxianum. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 115–119. 10.1016/j.tet.2006.10.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mu S.-Z.; Wang J.-S.; Yang X.-S.; He H.-P.; Li C.-S.; Di Y.-T.; Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Fang X.; Huang L.-J.; Hao X.-J. Alkaloids from Daphniphyllum oldhami. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 564–569. 10.1021/np070512s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariba R. M.; Houghton P. J.; Yenesew A. Antimicrobial Activities of a New Schizozygane Indoline Alkaloid from Schizozygia coffaeoides and the Revised Structure of Isoschizogaline. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 566–569. 10.1021/np010298m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mander L. N.; Prager R. H.; Rasmussen M.; Ritchie E.; Taylor W. C. The Chemical Constituents of Galbulimima species. X. The Structure of Himgalin. Aust. J. Chem. 1967, 20, 1705–1718. 10.1071/CH9671705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Seiser T.; Saget T.; Tran D. N.; Cramer N. Cyclobutanes in Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7740–7752. 10.1002/anie.201101053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fumagalli G.; Stanton S.; Bower J. F. Recent Methodologies That Exploit C–C Single-Bond Cleavage of Strained Ring Systems by Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9404–9432. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Murakami M.; Ishida N. Cleavage of Carbon–Carbon σ-Bonds of Four-Membered Rings. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 264–299. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscales S.; Csákÿ A. G. Transition-metal-free C–C Bond Forming Reactions of Aryl, Alkenyl and Alkynylboronic Acids and Their Derivatives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 8215–8225. 10.1039/C4CS00195H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankner T.; Hilmersson G. Instantaneous Deprotection of Tosylamides and Esters with SmI2/ Amine/Water. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 503–506. 10.1021/ol802243d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.