Abstract

Objective

The issue of unplanned reoperations poses significant challenges within healthcare systems, with assessing their impact being particularly difficult. The current study aimed to assess the influence of unplanned reoperations on hospitalized patients by employing the diagnosis-related group (DRG) to comprehensively consider the intensity and complexity of different medical services.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of surgical patients was conducted at a large tertiary hospital with two hospital districts employing data sourced from a DRG database. Hospital length of stay (LOS) and hospitalization costs were measured as the primary outcomes. Discharge to home was measured as the secondary outcome. Frequency matching based on DRG, regression modeling, subgroup comparison and sensitivity analysis were applied to evaluate the influence of unplanned reoperations.

Results

We identified 20820 surgical patients distributed across 79 DRGs, including 188 individuals who underwent unplanned reoperations and 20632 normal surgical patients in the same DRGs. After DRG-based frequency matching, 564 patients (188 with unplanned reoperations, 376 normal surgical patients) were included. Unplanned reoperations led to prolonged LOS (before matching: adjusted difference, 12.05 days, 95% confidence interval [CI] 10.36–13.90 days; after matching: adjusted difference, 14.22 days, 95% CI 11.36–17.39 days), and excess hospitalization costs (before matching: adjusted difference, $4354.29, 95% CI: $3,817.70–$4928.67; after matching: adjusted difference, $5810.07, 95% CI $4481.10–$7333.09). Furthermore, patients who underwent unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home (before matching: hazard ratio [HR] 0.27, 95% CI 0.23–0.32; after matching: HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.25–0.39). Subgroup analyses indicated that the outcomes across the various subgroups were mostly uniform. In high-level surgery subgroups (levels 3–4) and in relation to complex diseases (relative weight ≥ 2), the increase in hospitalization costs and LOS was more pronounce after unplanned reoperations. Similar results were observed with sensitivity analysis by propensity score matching and excluding short LOS.

Conclusions

Incorporating the DRG allows for a more effective assessment of the influence of unplanned reoperations. In managing such reoperations, mitigating their influence, especially in the context of high-level surgeries and complex diseases, remains a significant challenge that requires special consideration.

Keywords: Unplanned reoperation, diagnosis-related group, hospital length of stay, hospitalization cost, discharge to home, retrospective cohort study

Introduction

An unplanned reoperation is an adverse event in which a patient returns to the operating room owing to complications or other adverse outcomes following an initial index operation [1]. Unplanned reoperations are a major burden on the healthcare system and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [2–5]. Starting from 2021, based on prominent issues and weak links in national medical quality and safety, the National Health Commission of China has issued annual national medical quality and safety improvement goals. As an important indicator for evaluating operation quality in medical institutions, reducing the incidence of unplanned reoperations has been included as a national medical quality and safety improvement goal for both 2022 and 2024 in China [6], as lowering the number of unplanned reoperations remains an urgent medical quality, economic, and social challenge.

In terms of unplanned reoperations, most studies to date have described the incidence of unplanned reoperations from a clinical perspective and analyzed the causes and influencing factors [2,4,5,7–13]. A small number of studies have discussed the effect of unplanned reoperations and reported that patients with unplanned reoperations had longer hospitalization days and higher hospitalization costs compared with patients undergoing surgery without unplanned reoperation [4,5,9,14]. Moreover, previous studies have mainly performed simple single factor comparisons and have not systematically controlled for confounding factors to indicate the degree of difference concerning expenses for inpatient care and hospital length of stay (LOS). The effect of unplanned reoperations remains unclear.

Furthermore, the results of previous studies are not consistent, with large differences. For example, previous studies have shown that the incidence of unplanned reoperations has ranged from 0.6% to 14.2% [10,11,15–17], and the length of stay of unplanned reoperation has ranged from 12.1 to 35.03 days [4,5,9,13,16,18]. The reasons for these differences are complex. One is that individuals receiving care across various healthcare institutions and departments have varying medical conditions, disease types, surgical risks, and surgical challenges. Therefore, it is imperative to employ more scientifically stringent approaches, including diagnostic categorization systems, for an exhaustive analysis. There are several validated diagnostic classification schemes in existence, but the investigators have opted to use the disease diagnosis-related group (DRG). Developed at Yale University in 1967, DRG aggregates cases with comparable clinical pathways and cost profiles into clusters, taking into account a range of individual attributes such as gender, age, coexisting conditions, and associated complications, as well as specific diagnoses and surgical procedures, so that there is a standardized and equitable basis for comparing the intensity and complexity of diverse medical services [19,20]. This management tool has been widely used in medical payments, performance evaluations, and medical quality management [21–24]. However, to our best knowledge, the application of DRG in evaluating the influence of unplanned reoperations has been rarely undertaken.

Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the influence of unplanned reoperations on hospitalized patients by employing the DRG, and provide guidance for the prevention and management of unplanned reoperations.

Material and methods

Sample collection

This study was a retrospective cohort study of surgical patients. There were 48032 surgical patients in the cohort, distributed among 399 DRGs at Ningbo Medical Center LiHuili Hospital, a large tertiary hospital with 2200 beds and two hospital districts in Ningbo, China, from January 2021 to December 2021. We included patients who had unplanned reoperations and those without for their entire hospital stay in the same DRGs. According to the exclusion and inclusion criteria, 20820 surgical patients were recruited, including 188 patients with unplanned reoperations and 20632 normal surgical patients (without reoperation) in the same DRGs. Moreover, to eliminate the effect of inconsistent DRG distribution between the two groups, we performed DRG-based frequency matching. Normal surgical patients were randomly selected from the normal surgical group and frequency-matched with patients with unplanned reoperations in a 2:1 ratio based on the distribution ratio of unplanned reoperations among DRGs. After matching, 564 patients (188 patients with unplanned reoperations; 376 normal surgical patients) were included in the study. All patients were followed up from admission to discharge. All clinical and surgical data were recorded prospectively.

Surgery was coded according to the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification, Operations and Procedures, Volume 3 (ICD-9-CM-3). An unplanned reoperation refers to an adverse event whereupon inpatients return to the operating room due to complications or other adverse results from the index operation during the same hospitalization. An unplanned reoperation met at least one of three main criteria [25]: (i) a secondary operation due to postoperative complications such as postoperative bleeding/hematoma, anastomotic fistula, postoperative infection, arteriovenous thrombosis, and incision dehiscence/poor healing; (ii) a secondary operation due to medical errors such as foreign body retention after surgery, injury or removal of healthy organs of non-operative targets, and catheter breakage after surgery; and (iii) a secondary operation due to inspection errors. For example, the frozen section pathological results during the first operation were benign, whereas the tissues examined postoperatively showed malignancy, leading to the secondary operation.

The unplanned reoperation monitoring was completed by a five-person team, including three doctors and two operating room nurses. All team members had received uniform training. The determination of an unplanned reoperation included two steps: information system screening and a manual review. First, two nurses in the operating room screened for patients undergoing reoperation through the operation management system every day. Two doctors then independently determined whether an unplanned reoperation had occurred according to the definition of an unplanned reoperation in relation to the electronic health record system and the medical safety (adverse) events reporting system. If the determination results were inconsistent, a third doctor reviewed the disagreements to decide.

Inclusion criteria comprised the following: surgical inpatients aged 18 years and older, who had a discharge date ranging from January 2021 to December 2021. For unplanned reoperations, that definition also needed to be met. Exclusion criteria comprised the following: emergency patients and outpatients. Individuals lacking key data, including date of discharge, surgery information, DRG information, hospitalization costs and length of hospital stay, were also excluded.

Data collection and definition

In the present study, we collected data from multiple systems including DRG system, medical safety (adverse) events reporting system, operation management system and electronic medical record system (Figure S1 in additional file 1). From the Shanghai-DRG system, a refined version based on the Australian DRG, we gathered information on age, sex, surgery category, surgery level, hospital district, relative weight (RW), type of hospital discharge, hospitalization costs and LOS. Furthermore, we retrieved data on adverse events from the medical safety (adverse) events reporting system, encompassing a total of 18 event types (surgical events, anesthesia events, medical care events, blood transfusion events, unexpected cardiac arrest events in the hospital, hospital infection events, drug events, inspection/inspection/pathological section events, falls, pipeline events, pressure injuries, adverse device events, injury behavior events, public accidents, information security events, public security events, occupational exposure events, and other events). Unplanned reoperation information was collected from the operation management system, electronic medical record system, and medical safety (adverse) events reporting system.

The studied hospital had two hospital districts, recorded as district 1 and district 2. Age was recorded as a binary variable (classified into two groups: ≤ 65 years and > 65 years) in analyses. Sex was recorded as either male or female. The index surgery category was divided into general surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery, urology, otorhinolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, and others according to discipline. The index surgery level was divided into levels 1–4, according to operation difficulty, based on the Classification Catalogue of Surgery in Zhejiang Province, China (Performance Edition). The higher the surgical level, the more challenging the operation. RW is a distinctive metric within the DRG system, serving as a proxy for the complexity of diagnosis and therapy, the acuity of the disease, and the consumption of medical resources. An RW is assigned to each DRG category, signifying a cluster of cases with similar diagnostic profiles, treatment modalities, disease severity, and resource utilization. The higher the RW, the more complex the disease. RW was dichotomized into two categories: <2 and ≥2. To exclude the effect of other adverse events, adverse events data from the hospital’s medical safety (adverse) events reporting system were included. If a patient had other adverse events during hospitalization other than for an unplanned reoperation, this was categorized as ‘yes’, and ‘no’ otherwise.

The primary exposure was unplanned reoperation. The primary outcomes were length of hospital stay (calculated from the time/date of admission to the time/date of discharge) and the total hospitalization expenses. The secondary outcome was discharge to home, which was defined as the patient’s return to their residence for ongoing recovery, as directed by the physician, in contrast to other discharge ways such as transfer to another healthcare facility, transfer to community health services or township health centers, non-home discharge, death and others.

According to data from the People’s Bank of China, the mean exchange rate between the Chinese Yuan (CNY, ¥) and the United States Dollar (USD, $) was 6.45:1 throughout the duration of this study.

Statistical analysis

In the descriptive statistical analysis, categorical variables were depicted by their frequency counts and proportions. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations were reported when the data followed a normal distribution, and medians along with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used for data that did not conform to a normal distribution. Comparative analyses between groups were conducted using the chi-square test for nominal variables, the Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables that were not normally distributed. The Hodges-Lehmann estimate, derived from the Mann-Whitney U test, was employed to calculate the pseudo-median difference, which represents the median of all possible pairwise differences between groups.

For continuous outcomes (LOS and hospitalization costs), we estimated differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using linear regression models through adjusting for confounding variables, which were log-transformed to ensure a normal distribution. For the categorical outcome of being discharged to home, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was generated, followed by log-rank testing to assess differences between groups. This approach allowed us to evaluate the impact of unplanned reoperations on patient outcomes over time. We estimated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs using a Cox regression model to assess the risk associated with unplanned reoperations. An HR greater than 1 indicated increased risk, while an HR less than 1 indicated reduced risk. The selection of confounders for adjustment in the multivariable regression analysis was informed by the existing literature [5,16,26–32] and included hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level and RW. Additionally, analyses for interactions and subgroups were performed based on the aforementioned confounding variables to examine whether the impact of unplanned reoperations on patient outcomes varied across different subgroups.

We performed two sensitivity analyses to test whether findings in the primary outcomes were robust. First, although theoretically the DRGs are designed to be homogenous within each group, there may still be some variability present. Thus, propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to match the potential confounding factors described above. For PSM, we used greedy matching with a caliper width of 0.2 times the standard deviation of the PS logit [33] and matched patients with unplanned reoperations with the other surgical patients 1:1. Second, the primary analyses were repeated, excluding patients whose LOS was <2 days, as short stay patients might not have the opportunity to benefit from cohorting (i.e. be harmed by unplanned reoperations).

Patients with missing data (n = 609, 2.63%) were excluded because of variables ≤ 5% overall missing data were considered missing completely at random and hence were not imputed.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1 (http://www.R-project.org) and PASW Statistics 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Somers, NY, USA) software. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Detailed explanations of statistical terms were provided in the Supplementary Statistical Terms section of Additional File 1.

Results

Baseline patient data

We identified 20820 patients undergoing surgery who had been divided into 79 DRGs in 2021 (Figure 1). According to postoperative assessment, 188 (0.90%) patients had undergone unplanned reoperations, with percentages ranging from 0.84% (103/12226) to 0.99% (85/8594) in districts 1 and 2, respectively, and 20632 patients had not undergone unplanned reoperations. The median age was 56 (IQR 45–66) years, 10129 (48.7%) patients were male, and 267 (1.3%) patients had adverse events other than unplanned reoperations. The index surgery of most patients was general surgery (32.8%), surgery level 3–4 (64.8%). The median RW was 1.61 (IQR 1.33–2.73), and 8717 (41.9%) patients were in the RW ≥2 group. In addition, we found that 186 (98.94%) patients with unplanned reoperations were caused by postoperative complications, 1 caused by medical errors, and 1 caused by inspection errors. Among the surgical complications, the main one was postoperative bleeding/hematoma (92 patients). After index surgery, 40 (21.28%) patients experienced unplanned reoperation ≤1 day, 69 (36.70%) patients experienced reoperation greater than 1 day but less than or equal to 7 days, 61 (32.45%) patients experienced reoperation greater than 7 days but less than or equal to 14 days, and 18 (9.57%) patients experienced reoperation >14 days. The median postoperative day of unplanned reoperations taking place was 6 (IQR 2–10) days. The characteristics of the cohorts before and after matching are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants before and after matching.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 20820) | Unmatched (n = 20820) |

DRG-based frequency-matched (n = 564) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unplanned reoperations (n = 188) | Normal (n = 20632) | p value | Unplanned reoperations (n = 188) | Normal (n = 376) | p value | ||

| Hospital district, no.(%) | 0.271 | 0.251 | |||||

| District 1 | 12226 (58.7) | 103 (54.8) | 12123 (58.8) | 103 (54.8) | 225 (59.8) | ||

| District 2 | 8594 (41.3) | 85 (45.2) | 8509 (41.2) | 85 (45.2) | 151 (40.2) | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 56 (45,66) | 58 (49,69) | 56 (45,66) | 0.005 | 58 (49,69) | 60 (49,70) | 0.485 |

| Categorical variable, no.(%) | 0.001 | 0.759 | |||||

| ≤65 years | 15448 (74.2) | 119 (63.3) | 15329 (74.3) | 119 (63.3) | 233 (62.0) | ||

| >65 years | 5372 (25.8) | 69 (36.7) | 5303 (25.7) | 69 (36.7) | 143 (38.0) | ||

| Sex, no.(%) | <0.001 | 0.161 | |||||

| Male | 10129 (48.7) | 122 (64.9) | 10007 (48.5) | 122 (64.9) | 221 (58.8) | ||

| Female | 10691 (51.3) | 66 (35.1) | 10625 (51.5) | 66 (35.1) | 155 (41.2) | ||

| Adverse event, no.(%) | <0.001 | 0.036 | |||||

| Yes | 267 (1.3) | 11 (5.9) | 256 (1.2) | 11 (5.9) | 9 (2.4) | ||

| No | 20553 (98.7) | 177 (94.1) | 20376 (98.8) | 177 (94.1) | 367 (97.6) | ||

| Index surgery category, no.(%) | <0.001 | 0.696 | |||||

| General surgery | 6825 (32.8) | 92 (48.9) | 6733 (32.6) | 92 (48.9) | 177 (47.1) | ||

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 3405 (16.4) | 26 (13.8) | 3379 (16.4) | 26 (13.8) | 52 (13.8) | ||

| Neurosurgery | 616 (3.0) | 19 (10.1) | 597 (2.9) | 19 (10.1) | 38 (10.1) | ||

| Urology | 2106 (10.1) | 18 (9.6) | 2088 (10.1) | 18 (9.6) | 30 (8.0) | ||

| Otorhinolaryngology | 4089 (19.6) | 14 (7.4) | 4075 (19.8) | 14 (7.4) | 28 (7.4) | ||

| Orthopedics | 1592 (7.6) | 14 (7.4) | 1578 (7.6) | 14 (7.4) | 27 (7.2) | ||

| Others | 2187 (10.5) | 5 (2.7) | 2182 (10.6) | 5 (2.7) | 24 (6.4) | ||

| Index surgery level, no.(%) | 0.003 | 0.355 | |||||

| 1–2 level | 7319 (35.2) | 47 (25.0) | 7272 (35.2) | 47 (25.0) | 81 (21.5) | ||

| 3–4 level | 13501 (64.8) | 141 (75.0) | 13360 (64.8) | 141 (75.0) | 295 (78.5) | ||

| RW, median (IQR) | 1.61 (1.33,2.73) | 2.71 (1.68,3.57) | 1.60 (1.33,2.73) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.68,3.57) | 2.71 (1.68,3.57) | 1.000 |

| As a categorical variable, no.(%) | <0.001 | 1.000 | |||||

| <2 | 12103 (58.1) | 53 (28.2) | 12050 (58.4) | 53 (28.2) | 106 (28.2) | ||

| ≥2 | 8717 (41.9) | 135 (71.8) | 8582 (41.6) | 135 (71.8) | 270 (71.8) | ||

DRG: diagnosis-related group; RW: relative weight; IQR: interquartile range.

Primary outcome

As shown in Table 2, before matching, univariate analysis suggested that unplanned reoperations resulted in an excess of 16 (14–18) days of LOS and $7357.07 ($6438.15–$8405.88) in hospitalization costs, as determined by the Hodges-Lehmann estimate from the Mann-Whitney U test. Subsequent multivariable linear regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level and RW, revealed that unplanned reoperations were associated with an increased LOS of 12.05 (10.36–13.90) days and an increased hospitalization costs of $4354.29 ($3817.70-$4928.67).

Table 2.

Associations between unplanned reoperations and hospitalized patient outcomes.

| Outcomes | Unplanned reoperations | Normal | Unadjusted estimated effect (95%CI) | p value | Adjusted estimated effect (95%CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched (n = 20820) | ||||||

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 25 (15,42) | 8 (5,13) | 16 (14,18)a | <0.001 | 12.05 (10.36,13.90)b | <0.001 |

| Hospital expenses ($), median (IQR) | 10660.50 (5698.04,20448.47) | 2542.13 (1508.82,5482.39) | 7357.07 (6438.15,8405.88)a | <0.001 | 4354.29 (3817.70,4928.67)b | <0.001 |

| Discharge to home (yes/no) | 159/29 | 19641/991 | 0.27 (0.23,0.31)c | <0.001 | 0.27 (0.23,0.32)d | <0.001 |

| DRG-based frequency-matched (n = 564) | ||||||

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 25 (15,42) | 13 (8,18) | 12 (10,14)a | <0.001 | 14.22 (11.36,17.39)b | <0.001 |

| Hospital expenses ($), median (IQR) | 10660.50 (5698.04,20448.47) | 5251.13 (2629.53,8786.03) | 5043.05 (3726.66,6400.51)a | <0.001 | 5810.07 (4481.10,7333.09)b | <0.001 |

| Discharge to home (yes/no) | 159/29 | 340/36 | 0.36 (0.30,0.45)c | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.25,0.39)d | <0.001 |

LOS: length of stay; CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range.

Estimated effects between groups were expressed as follows: as a pseudo-median difference calculated using the Hodges–Lehmann estimate based on the Mann–Whitney U test; as a coefficient calculated by linear regression models; as a hazard ratio calculated by Cox regression models. Because the Hodges–Lehmann estimator was used, the estimated difference was not the crude difference between the medians.

This estimated difference effect was calculated by Mann–Whitney U test.

This estimated difference effect was calculated by linear regression model that adjusted for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.

This estimated hazard ratio effect was calculated by univariable Cox regression model.

his estimated hazard ratio effect was calculated by Cox regression model that adjusted for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.

After DRG-based matching (Table 2), univariate analysis revealed that unplanned reoperations led to an excess of 12 (10–14) days of LOS and $5043.05 ($3726.66–$6400.51) in hospitalization costs, as determined by the Hodges-Lehmann estimate from the Mann-Whitney U test. Subsequent multivariable linear regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level and RW, revealed that unplanned reoperations were associated with an increased LOS of 14.22 (11.36–17.39) days and an increased hospitalization costs of $5810.07 ($4481.10–$7333.09).

Secondary outcome

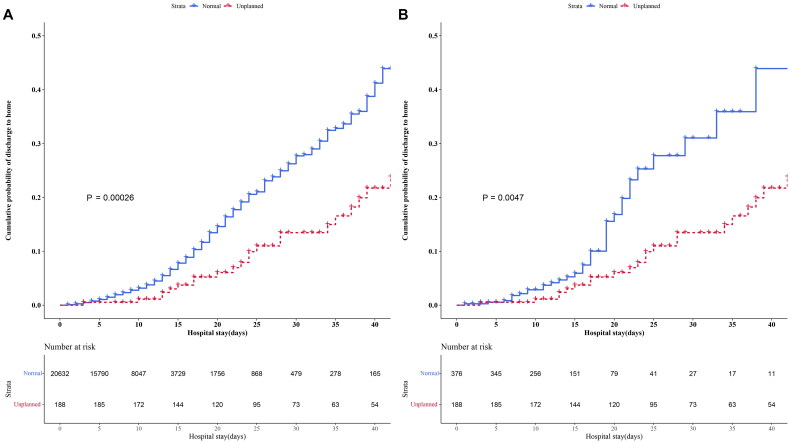

Before matching, Kaplan–Meier curve analysis showed a positive association between unplanned reoperations and a decreased rate of discharge to home (a greater risk of hospitalization) (p < 0.001; Figure 2). Univariable Cox regression analysis demonstrated that patients underwent unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home compared with normal surgical patients (HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.23–0.31; p < 0.001; Table 2). Subsequent multivariable Cox regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, revealed that the risk effect remained consistent (HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.23–0.32; p < 0.001; Table 2), indicating that unplanned reoperations were associated with a lower discharge-to-home rate.

Figure 2.

Probability of discharge to home of study participants. (A) Probability of discharge to home of study participants before matching. (B) Probability of discharge to home of study participants after DRG-based frequency matching.

After DRG-based matching, Kaplan–Meier curve analysis showed a positive association between unplanned reoperations and a decreased rate of discharge to home (a greater risk of hospitalization) (p = 0.0047; Figure 2). Univariable Cox regression analysis demonstrated that patients underwent unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home compared with normal surgical patients (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.30–0.45, p < 0.001; Table 2). Subsequent multivariable Cox regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, revealed that the risk effect remained consistent (HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.25–0.39, p < 0.001; Table 2), indicating that unplanned reoperations were associated with a lower discharge-to-home rate.

Additionally, the present study revealed that the mortality rate for patients who underwent unplanned reoperations (1.60%, 3/188) was higher than that for patients with normal surgical patients (0.073%, 15/20632). However, due to the small number of deaths, no further analysis was made.

Subgroup analyses

Subsequently, we conducted subgroup analyses to assess the influence of potential confounding variables on the primary outcomes. The subgroup analyses indicated a highly consistent pattern (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of subgroup analyses for LOS. (A) Forest plot of subgroup analyses for LOS before matching. (B) Forest plot of subgroup analyses for LOS after DRG-based frequency matching. Subgroup analyses with adjusted differences and 95% confidence intervals for LOS adjusted, if not be stratified, for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.

Figure 4.

Forest plots of subgroup analyses for hospitalization costs. (A) Forest plot of subgroup analyses for hospitalization costs before matching. (B) Forest plot of subgroup analyses for hospitalization costs after DRG-based frequency matching. Subgroup analyses with adjusted differences and 95% confidence intervals for hospitalization costs adjusted, if not be stratified, for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.).

In the subgroup analyses for LOS, significant interactions were observed between unplanned reoperations and index surgery category (Pinteraction = 0.005), index surgery level (Pinteraction < 0.001), and RW (Pinteraction = 0.016) before matching (Figure 3 and table S1 in additional file 1), indicating that the impact of unplanned reoperations on LOS varied across seven index surgery category subgroups,two index surgery level subgroups and two RW subgroups. There were statistically significant interactions between unplanned reoperations and index surgery level (Pinteraction = 0.006) after matching (Figure 3 and table S1 in additional file 1), indicating that the impact of unplanned reoperations on LOS varied across two index surgery level subgroups.

In the subgroup analyses for hospitalization costs, significant interactions were observed between unplanned reoperations and age both before and after matching (before matching: Pinteraction = 0.005; after matching: Pinteraction = 0.014), and index surgery level (before matching: Pinteraction < 0.001; after matching: Pinteraction = 0.003) (Figure 4 and table S2 in additional file 1), indicating that the impact of unplanned reoperations on hospitalization costs varied across two age subgroups and two index surgery level subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

PSM of 1:1 was used to match 188 patients who had undergone unplanned reoperations with 188 patients who had not, based on the following potential confounding variables: hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW. The clinical characteristics exhibited similarity and were comparable between the two groups (table S3 in additional file 1). After PSM (Table 3), univariate analysis indicated that unplanned reoperations led to an excess of 8 (5–10) LOS days and $4521.60 ($2977.44–$6069.84) in hospitalization costs, as determined by the Hodges-Lehmann estimate from the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariable linear regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, revealed that unplanned reoperations led to an excess of 6.98 (3.94–10.51) LOS days and $4240.09 ($2660.96–$6109.51) in hospital costs.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the associations between unplanned reoperations and hospitalized patient outcomes.

| Outcomes | Unplanned reoperations | Normal | Unadjusted estimated effect (95%CI) | p value | Adjusted estimated effect (95%CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM (n = 376) | ||||||

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 25 (15,42) | 16 (11,23.75) | 8 (5,10)a | <0.001 | 6.98 (3.94,10.51)b | <0.001 |

| Hospital expenses ($), median (IQR) | 10660.50 (5698.04, 20448.47) | 5596.08 (2938.80, 10877.81) | 4521.60 (2977.44, 6069.84)a | <0.001 | 4240.09 (2660.96, 6109.51)b | <0.001 |

| Discharge to home (yes/no) | 159/29 | 179/9 | 0.48 (0.38, 0.60)c | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.32, 0.55)d | <0.001 |

| Excluding short LOS (n = 18565) | ||||||

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 25 (15,42) | 9 (6,13) | 15 (13,17)a | <0.001 | 11.85 (10.46, 13.34)b | <0.001 |

| Hospital expenses ($), median (IQR) | 10660.50 (5698.04, 20448.47) | 3017.42 (1854.58, 5820.97) | 7007.58 (6085.22, 8043.62)a | <0.001 | 4886.84 (4337.74, 5468.45)b | <0.001 |

| Discharge to home (yes/no) | 159/29 | 17438/939 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.33)c | <0.001 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.33)d | <0.001 |

LOS: length of stay; CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range.

Estimated effects between groups were expressed as follows: as a pseudo-median difference calculated using the Hodges–Lehmann estimate based on the Mann–Whitney U test; as a coefficient calculated by linear regression models; as a hazard ratio calculated by Cox regression models. Because the Hodges–Lehmann estimator was used, the estimated difference was not the crude difference between the medians.

This estimated difference effect was calculated by Mann–Whitney U test.

This estimated difference effect was calculated by linear regression model that adjusted for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.

This estimated hazard ratio effect was calculated by univariable Cox regression model.

This estimated hazard ratio effect was calculated by Cox regression model that adjusted for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW.

Using univariable Cox regression analysis, patients underwent unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home compared with normal surgical patients (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.38–0.60, p < 0.001; Table 3). Subsequent multivariable Cox regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, revealed that the risk effect remained consistent (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.32–0.55, p < 0.001; Table 3)

When excluding patients with LOS < 2 days (the clinical characteristics were detailed in table S4 in additional file 1), the findings remained consistent with those of the primary analysis. Univariate analysis indicated that unplanned reoperations led to an excess of 15 (13–17) LOS days and $7007.58 ($6085.22–$8043.62) in hospitalization costs (Table 3), as determined by the Hodges-Lehmann estimate from the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariable linear regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, indicated that unplanned reoperations led to an excess of 11.85 (10.46–13.34) LOS days and $4886.84 ($4337.74–$5468.45) in hospitalization costs.

Using univariable Cox regression analysis after excluding patients with LOS < 2 days, the remaining patients with unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home compared with normal surgical patients (HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.24–0.33, p < 0.001; Table 3). Subsequent multivariable Cox regression analysis, which controlled for hospital district, age, sex, adverse event, surgery category, surgery level, and RW, revealed that the risk effect remained consistent (HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.24–0.33, p < 0.001; Table 3).

Discussion

By combining with multiple systems (including DRG system, operation management system, electronic medical record system, and medical safety (adverse) events reporting system), and multiple real-world study methods (including frequency matching based on DRG, regression modeling, subgroup comparison and sensitivity analysis), our study of unplanned reoperations showed a significantly prolonged hospital LOS, higher hospitalization costs, and lower discharge-to-home rate, suggesting poorer patient prognosis, increased patient and hospital burden, and lower medical efficiency of hospitals. Additionally, subgroup analysis indicated that for patients with high-level surgery (levels 3–4) and complex diseases (relative weight ≥2), there was a substantial rise in both LOS and hospitalization expenses after unplanned reoperations, indicating a more pronounced increase in both the duration and financial impact. To ensure patient safety, medical institutions should apply targeted management concerning unplanned reoperations in relation to DRGs and apply appropriate prevention and improvement measures. These steps are necessary to reduce more accurately and effectively the burden of unplanned reoperations and improve the overall medical efficiency of hospitals.

Unplanned reoperations pose important medical quality, economic, and social challenges. Previous studies have found that the LOS of unplanned reoperations has ranged from 12.1 days to 35.03 days [4,5,9,13,16,18], significantly higher than that of normal surgical patients. However, due to different baseline characteristics, disease types, surgery risk, and surgery difficulty among individuals in various healthcare institutions and departments, it is difficult to evaluate accurately the excess of LOS due to unplanned reoperations. The DRG system involves case-mix classification in which patients are divided into different diagnosis groups for management according to sex, age, coexisting conditions, and associated complications, as well as specific diagnoses and surgical procedures [19,20] for use in relation to cost control, performance evaluation, and medical quality management. Combined with DRG, a previous study showed a 1.4 – fold increase in LOS and a 1.0 – fold increase in hospitalization costs for unplanned reoperations, mainly through descriptive statistical analyses and univariate comparisons [34]. Zhang et al. controlled for the influence of confounding varioubles by DRG matching and found that medical injuries were related to $57727 in excess hospitalization costs and 10.89 extra LOS days [32]. Similarly, through DRG matching, the present study found that unplanned reoperations led an excess of 14.22 LOS days and an additional increase of $5810.07 in terms of average cost per case. Moreover, after subgroup analysis, PSM analysis, and sensitivity analysis excluding short hospital stay, the results were similar, indicating that unplanned reoperations resulted in a heavy burden for patients, hospitals, and the government.

Previous studies have indicated that unplanned reoperations are associated with increased mortality [4,5]. The present study also showed that the mortality rate for patients with unplanned reoperations (1.60%) was higher than that for patients with normal surgeries (0.073%). However, owing to the limited number of deaths, no additional analyses were conducted. In order to comprehensively evaluate the prognosis of hospitalized patients, some studies have incorporated novel indicators of discharge outcomes. Kohn et al. examined the relationship between bedspacing and the likelihood of being discharged to home, finding that increased bedspacing was linked to reduced probabilities of discharge to home [35]. Accordingly, we conducted analyses to compare the likelihood of being discharged to home between the groups, an outcome variable that had not been explored in prior studies within this context. Our findings indicated that patients with unplanned reoperations had a reduced likelihood of being discharged to home compared with normal surgical patients. The results remained consistent following sensitivity analyses conducted via PSM and after the exclusion of cases with short hospitalization days. These results further indicated that unplanned reoperations resulted in longer LOS and were less likely to discharge to home, indirectly reflecting a less favorable prognosis for these individuals, suggesting potential medium to long-term adverse effects associated with unplanned reoperations.

The analyses of the subgroups demonstrated a uniform finding that patients who underwent unplanned reoperations had an extended length of stay and higher hospitalization costs across the two hospital districts, further confirming the influence of unplanned reoperations. Additionally, our subgroup analysis of LOS and hospitalization costs within both matched and unmatched groups revealed significant interactions between the index surgery level and unplanned reoperations, which indicated that after unplanned reoperations in the high-level surgery group, LOS and hospitalization costs were notably greater compared with those in the low-level surgery group, suggesting that the perioperative management of high-level surgeries is particularly important. In the subgroup analysis of LOS, we found that, prior to matching and after correction for multiple factors, there were interactions between the LOS and RW groups, and between the LOS and surgery category groups, suggesting that the LOS for the RW ≥2 group and the orthopedic surgery group were the most prolonged. Although the interactions after matching were not statistically significant, they all showed the same trend. Moreover, in the subgroup analysis of hospitalization costs, interactions were observed between hospitalization costs and age groups in both the matched and unmatched groups, which indicated that after unplanned reoperations in the older adult group, hospitalization costs were significantly higher. These findings suggest that there is a need for focused consideration on patients with challenging and complex diseases, those undergoing orthopedic surgeries, as well as older adult patients. However, given the differences in interaction analysis results between different methods used in these studies, further studies are needed.

Unplanned reoperations are a major burden on the healthcare system and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality [2–5]. Avoiding the occurrence of unplanned reoperation and reducing their effect is essential. The National Health Commission has twice designated the reduction of the incidence of unplanned reoperations as a national target for improving medical quality and safety in China. In actual management, focus should be placed on core strategies, as follows: (i) medical institutions should establish working groups composed of members from medical, surgical, anesthetic, nursing, and other relevant departments; (ii) medical institutions should strengthen the management of surgery, and ensure the implementation of surgery related management systems such as hierarchical management of surgery, physician authorization management, and a surgical safety verification system; (iii) medical institutions should establish multi-department joint monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for unplanned reoperations, conduct data analysis and feedback; and (iv) medical institutions should apply quality management tools to identify and analyze key factors [6].

As far as we know, this is the first research systematically evaluating the impact of unplanned reoperations on hospitalized patients combined with multiple systems including DRG system, operation management system, electronic medical record system, and medical safety (adverse) events reporting system. By facilitating interconnectivity and interoperability among multiple systems, the impact of ‘information silos’ has been effectively mitigated, resulting in the acquisition of more comprehensive and authentic data. Furthermore, through the application of DRG matching, regression analysis, subgroup analysis, and sensitivity analysis, the research findings have been rendered more reliable and possess enhanced generalizability.

There were several limitations in the present study. First, this study was conducted at a large tertiary hospital with 2200 beds and two hospital districts, which was a single center study. In total 20820 patients were included; however, only 188 patients underwent unplanned reoperations following a rigorous selection process based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Consequently, the study population was relatively small. Second, patients were only followed up from hospitalization to hospital discharge, and the long-term outcomes of unplanned reoperations on patients post-discharge remain unclear. Third, multiple versions of DRG exist in China, among which the Shanghai version was chosen for the present study. The consistency of results across various DRG versions requires further exploration.

Our study provided critical insights into the impact of unplanned reoperations on patient outcomes. Although our findings were based on a specific dataset, the core mechanisms of unplanned reoperations were consistent and held broader implications for understanding their multifaceted effects across different healthcare settings. The use of DRG in our study, an international standard for healthcare resource allocation and quality assessment, further validated the potential generalizability of our results. DRG was used worldwide to classify hospital cases, thereby allowing for comparisons across different hospitals and regions. The analysis of unplanned reoperations within the DRG framework provided valuable insights for international healthcare policymakers and providers. Future research may focus on the following directions: First, conducting multi-center studies based on DRG and developing predictive models using machine learning techniques would identify high-risk patients early, facilitating timely interventions to enhance outcomes. Second, longitudinal studies to track the long-term outcomes of patients undergoing unplanned reoperations will provide insights into their persistent impact on health and healthcare resources. Third, a cost-effectiveness analysis of interventions aimed at reducing unplanned reoperations could offer valuable information for healthcare policymakers and administrators.

Conclusions

Unplanned reoperations significantly prolonged LOS and hospitalization costs and affected patient prognosis. Incorporating the DRG allows for a more effective assessment of the influence of unplanned reoperations. In managing such reoperations, mitigating their influence, especially in the context of high-level surgeries and complex diseases, remains a significant challenge that requires special consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Birong Xu and Shunqi Fan for their support, thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the grants from Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province [2022KY293, 2024KY279], Ningbo Natural Science Foundation [2024J393], Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program [2024020818], Huili Fund of Ningbo Medical Center Lihuili Hospital [2022YB007], Lihuili Hospital Research and Cultivation Project [2022KYPYXM-L2].

Author contributions

R.F. and Z.Y.Y. designed this study. R.F. and S.Q.M. were responsible for conducting statistical analysis, writing and revising the article. Q.F.C. and Z.Y.Y. were responsible for conception, interpretation and critically reviewing the article. S.G. and L.L.W. were responsible for collecting data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Ningbo Medical Center LiHuili Hospital (Approval number: KY2022PJ208). Informed consent was not required because of the retrospective nature of this study and all data provided by the DRG database were deidentified. Furthermore, the ethics committee of Ningbo Medical Center LiHuili Hospital granted approval to waive the requirement for informed consent.

Data availability statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Hirshberg A, Stein M, Adar R.. Reoperation. Planned and unplanned. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(4):897–907. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardakli N, Friedman DS, Boland MV.. Unplanned return to the operating room after tube shunt surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;229:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno Elola-Olaso A, Davenport DL, Hundley JC, et al. Predictors of surgical site infection after liver resection: a multicentre analysis using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. HPB. 2012;14(2):136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Zhu H, Ye P, et al. Unplanned reoperation after radical surgery for oral cancer: an analysis of risk factors and outcomes. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuo X, Cai J, Chen Z, et al. Unplanned reoperation after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: causes, risk factors, and long-term prognostic influence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:965–972. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s164929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notification of the National Health Commission Office on Printing and Distributing the National Medical Quality and Safety Improvement Goals for 2024.; 2024. [February 1st]. Available from http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7657/202402/6aea7c6510da48a6b50e84417b4f30a3.shtml.

- 7.Edwards JB, Wooster MD, Tran T, et al. Factors associated with unplanned reoperation after above-knee amputation. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(5):461–462. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerezoudis P, Glasgow AE, Alvi MA, et al. Returns to operating room after neurosurgical procedures in a tertiary care academic medical center: implications for health care policy and quality improvement. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(6):e392–e401. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li P, Huang CM, Tu RH, et al. Risk factors affecting unplanned reoperation after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: experience from a high-volume center. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(10):3922–3931. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangal NR, Nishimori K, Zhao E, et al. Understanding risk factors associated with unplanned reoperation in major head and neck surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(11):1044–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toboni MD, Smith HJ, Bae S, et al. Predictors of unplanned reoperation for ovarian cancer patients from the national surgical quality improvement program database. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(7):1427–1431. doi: 10.1097/igc.0000000000001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woon CYL, Christ AB, Goto R, et al. Return to the operating room after patellofemoral arthroplasty versus total knee arthroplasty for isolated patellofemoral arthritis-a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2019;43(7):1611–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-04280-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao H, Wang Y, Quan H, et al. Incidence, causes and risk factors for 30-day unplanned reoperation after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: experience of a high-volume center. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(3):213–220. doi: 10.14740/gr1032w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sah BK, Chen MM, Yan M, et al. Reoperation for early postoperative complications after gastric cancer surgery in a Chinese hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):98–103. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansari MZ, Collopy BT.. The risk of an unplanned return to the operating room in Australian hospitals. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(1):10–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guevara OA, Rubio-Romero JA, Ruiz-Parra AI.. Unplanned reoperations: Is emergency surgery a risk factor? A cohort study. J Surg Res. 2013;182(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(5):519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin N, Jin P, Martin NA.. Assessing early unplanned reoperations in neurosurgery: opportunities for quality improvement. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(1):198–205. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.jns14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fetter RB, Shin Y, Freeman JL, et al. Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Med Care. 1980;18(2 Suppl):1–53. iii, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noronha MF, Veras CT, Leite IC, et al. The development of diagnosis-related groups–DRG’s. Methodology for classifying hospital patients. Rev Saude Publica. 1991;25(3):198–208. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101991000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan R, Yan Z, Wang A, et al. The influence of adverse events on inpatient outcomes in a tertiary hospital using a diagnosis-related group database. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):18114. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-69283-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng L, Tian Y, He M, et al. Impact of DRGs-based inpatient service management on the performance of regional inpatient services in Shanghai, China: an interrupted time series study, 2013-2019. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):942. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05790-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kutz A, Gut L, Ebrahimi F, et al. Association of the swiss diagnosis-related group reimbursement system with length of stay, mortality, and readmission rates in hospitalized adult patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e188332. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.8332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puzniak L, Gupta V, Yu KC, et al. The impact of infections on reimbursement in 92 US hospitals, 2015-2018. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(10):1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, Wang H, Zheng X, et al. Practice and thoughts on unplanned secondary surgery monitoring. Chin Hospitals. 2013;17(8):26–27. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0592.2013.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buttigieg SC, Abela L, Pace A.. Variables affecting hospital length of stay: a scoping review. J Health Organ Manag. 2018;32(3):463–493. doi: 10.1108/jhom-10-2017-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claessen F, Schol I, Ring D.. Unplanned operations and adverse events after surgery for diaphyseal fracture of the clavicle. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2019;7(5):402–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jian W, Huang Y, Hu M, et al. Performance evaluation of inpatient service in Beijing: a horizontal comparison with risk adjustment based on Diagnosis Related Groups. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin HC, Tung YC, Chen CC, et al. Relationships between length of stay and hospital characteristics under the case-payment system in Taiwan: using data for vaginal delivery patients. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26(4):259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu SW, Pan Q, Chen T.. Research on diagnosis-related group grouping of inpatient medical expenditure in colorectal cancer patients based on a decision tree model. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(12):2484–2493. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu K, Xu ZG, Yang J, et al. Comprehensive analysis of unplanned reoperations in head and neck neoplasms. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2020;42(3):247–251. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20190604-00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhan C, Miller MR.. Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization. Jama. 2003;290(14):1868–1874. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150–161. doi: 10.1002/pst.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhuang Y, Hu WS, Dong S, et al. Analysis on incremental time cost and hospitalization expenditure due to unplanned reoperation. Chin Health Econ. 2022;41(7):28–36. doi: 10.7664/j.issn.1003-0743.2022.7.zgwsjj202207008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohn R, Harhay MO, Bayes B, et al. Influence of bedspacing on outcomes of hospitalised medicine service patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(2):116–122. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.