ABSTRACT

Background

Ileostomy and colostomy are two effective clinical methods for intestinal diversion, but both have disadvantages. It is necessary to adopt corresponding nursing interventions for stoma patients to improve their quality of life.

Aim

The study explored the recovery status and nursing differences of patients who underwent temporary ileostomy and temporary colostomy.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Methods

Patients who underwent temporary ostomy were divided into the ileostomy group and colostomy group according to the surgical method. Relevant clinical data of patients were collected, and differences in postoperative nursing were explored through a chi‐square test. Meanwhile, a Quality‐of‐Life (QOL) assessment was compiled to assess the impact of different ostomy types on patients' postoperative quality of life. The study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement. The research question of the study focuses on how to evaluate the patient's recovery status and provide a basis for targeted nursing care for post‐ostomy patients.

Results

The postoperative regular defecation rate of the ileostomy group was significantly lower than that of the colostomy group (p = 0.031), and the anastomotic healing rate of the ileostomy group was significantly higher than that of the colostomy group 1 week postoperatively (p = 0.037). According to the analysis of the QOL assessment, the ileostomy group showed significantly higher tolerance to ostomy faeces odour than the colostomy group (p = 0.002), and postoperative appetite in the ileostomy group was significantly better than that in the colostomy group (p = 0.002).

Conclusions

Compared with the colostomy group, the ileostomy group had a higher anastomotic healing rate 1 week postoperatively, a faster recovery of intestinal peristalsis, a better appetite after surgery, an easier tolerance to the odour of stoma faeces and a higher comprehensive postoperative quality of life.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Nurses and other healthcare professionals should be aware of the differences in surgical techniques for stoma patients. Nursing work should strengthen attention to postoperative diet and ostomy hygiene care for colostomy patients.

Patient or Public Contribution

Fifty patients consented and were enrolled. The stoma surgeries were carried out by the surgical team, while the nursing team was responsible for postoperative care, data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Keywords: enterostomy care, postoperative nursing, quality of life scale, temporary colostomy, temporary ileostomy

1. Background

An ileostomy or a colostomy is usually performed when it is necessary to remove or bypass a portion of the intestine. This procedure will be considered as a part of the treatment for diseases such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, bowel obstruction, diverticulitis, familial adenomatous polyposis or certain intestinal injuries (Semenova et al. 2023). Patients with stomas suffer from both physical and psychological distress due to changes in their body structure and complications related to the stoma (such as stoma leakage, stoma bag swelling, improper stoma bag placement and rashes) (Koc et al. 2023; Neuman et al. 2012), which affect all aspects of their lives (Bulkley et al. 2013; Bekkers et al. 1997; Bonill‐de‐las‐Nieves et al. 2014; Kenderian et al. 2014; Mathis et al. 2013; Williams 2012).

Currently, ileostomy and colostomy have been two effective clinical methods for intestinal diversion, but both still have many disadvantages. The faeces from an ileostomy, having no chance to undergo water absorption in the colon, are generally very thin and contain a lot of digestive enzymes which may cause severe irritation to the skin. Therefore, ileostomy faeces can be watery and voluminous, thus easily leading to infection if the stoma is not properly cared for (Tsujinaka et al. 2022, 2023). Colostomy faeces are generally semi‐solid. The further the colostomy is from the anus, the more normal the stool consistency becomes, but the bacterial density also increases. Due to changes in bowel habits and the impact of odour emission, colostomy patients are prone to negative emotions such as shame, anxiety and low self‐esteem (Robitaille et al. 2023; Gavriilidis et al. 2019). In a recent study, Lee et al. analysed cases where patients underwent sigmoidectomy for diverticulosis with end‐to‐end anastomosis without a stoma and subsequently developed bowel leaks, necessitating secondary ileostomy or colostomy. The study found no statistical differences between the two groups in terms of bowel obstruction incidence, hospital stay duration, discharge recovery, readmission or 30‐day mortality. However, the colostomy group was associated with a higher incidence of infectious shock, and the closure rate of colostomies was lower than that of ileostomies (Lee et al. 2023).

Therefore, in addition to routine care, it is clinically necessary to adopt corresponding nursing interventions for different stoma patients to improve their quality of life. The Quality‐of‐Life assessment, as an effective tool for analysing patients' quality of life, has been widely used in clinical practice (Zewude et al. 2021; Prieto et al. 2005). This study aims to evaluate the impact differences between ileostomy and colostomy on patients' quality of life by comparatively analysing patients' clinical data and QOL assessment. We hope that providing targeted nursing measures for different stoma patients will improve their quality of life.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study was conducted as a retrospective cohort study. Our research question is how to evaluate the post‐ostomy patient's recovery status and provide a basis for targeted nursing care for post‐ostomy patients. To enhance the quality and transparency of health research, the study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies (Skrivankova et al. 2021) (see Data S1). The study protocol was registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR). The use of all the clinical patients' data was approved by the Ethics Committee with informed consent from all patients and conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki consent principles.

2.2. Study Subjects

The Study used n = as the equation to estimate sample size (p1: estimated colostomy complication rate, 35%; p2: estimated ileostomy complication rate, 5%; significance: α = 0.05, Z α/2 = 1.96; statistical power: 1 − β = 0.80, Z β = 0.84). This study collected data from 67 patients, including 38 patients with ileostomies and 29 patients with colostomies, who underwent temporary stoma surgery in the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery at our hospital between January 2021 and December 2021. The Clinical baseline data of these patients, including age, gender, perioperative period and diagnosis were collected and statistically analysed. The inclusion criteria: (1) Patients who need surgical treatment and are planning to undergo temporary colostomy. (2) Patients with no history of mental illness or impaired consciousness. (3) Aged 18–80 years old. (4) Patients who signed the informed consent form and were able to complete the questionnaire survey in a clear‐headed state. The exclusion criteria: (1) Serious complications after surgery. (2) Poor mental state after surgery. (3) Confirmed consciousness disorder after surgery. (4) Patients with permanent stoma. Finally, 25 ileostomy patients and 25 colostomy patients were selected for the study.

2.3. Observation Indicators

Based on the literature review and clinical practice, 1 week post‐surgery was selected as the standard time for stoma healing. The anastomotic healing was defined as having no anastomotic strictures and no anastomotic leakage. Routine care and natural defecation methods were applied to stoma patients. The regularity and frequency of bowel movements were statistically analysed by observing indicators such as whether the defecation time was regular, whether there was a sensation of needing to defecate before defecation, the feeling during defecation and the condition of the stoma bags.

2.4. QOL Assessment

The structured Quality‐of‐Life (QOL) assessment, modified from the scale developed by Prieto et al. in 2005 (Williams 2012), includes 10 questions covering aspects of the economic ability of stoma appliances purchasing, tolerance of odour from stoma faeces, impact on appetite, freedom of movement, influence on clothing choices, effect on daily exercise, frequency of stoma accidents, impact on daily work, influence on personal hygiene and impact on sexual relationships. Each aspect is rated as good (10 points), fair (5 points) or poor (0 points). A total score of 71–100 is considered good, 31–70 satisfactory and 0–30 is unacceptable. Each patient completed the scale with the accompaniment and guidance of a specialist nurse, who was blinded to the members of the surgical team.

2.5. Stoma Surgeries

Ileostomy and colostomy surgeries followed the standard procedures of the hospital's Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery and were performed by a unified surgical team. Ileostomies were located near McBurney's point in the right lower abdomen, while colostomies were located near the left lower abdomen in the anti‐McBurney's point area. All stomas were single‐barrel, with the bowel segment pulled out through the abdominal wall and fixed to the abdominal wall in layers (peritoneum, external oblique aponeurosis and skin) using 3–0 absorbable sutures.

2.6. Stoma Nursing

Postoperatively, specialised nurses provided care for the stomas using two‐piece stoma bags for excretion storage. The two‐piece enterostomy bag is superior to the single‐piece system in terms of leak prevention, comfort, and flexibility due to its high sealing, good skin protection, and stable and reliable connection method. Patients and their families received instruction from the specialised nursing team on stoma nursing knowledge and procedures to ensure the patient or family members could independently replace the stoma bags and handle related issues, such as stoma bag leakage, skin damage and excessive stoma bag inflation.

2.7. Addressing Bias

To avoid potential biases, the study was implemented as a blind trial with blinded data collection and blinded data analysis. Without knowing the ostomy type, the nursing staff provided general care and guidance in accordance with clinical standards and guided the patients to complete the QOL scale to reduce information bias. In addition, the statistical analysts analysed the data without knowing the specific surgical grouping of the enrolled patients to reduce subjective bias.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 statistical software. The χ2 test and Student's t‐test were used to compare categorical variables between groups, with p < 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Enrolment

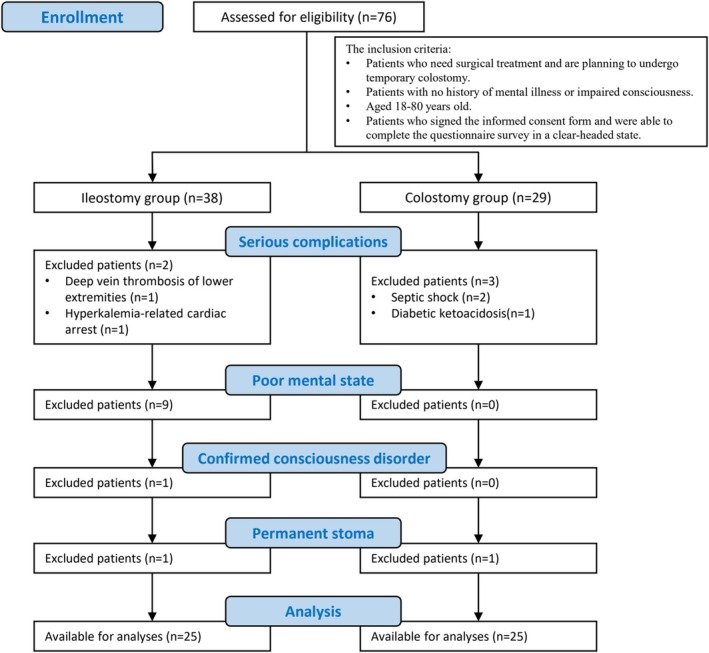

Based on the inclusion criteria, 67 patients were enrolled, including 38 patients with ileostomies and 29 patients with colostomies. With the exclusion criteria, 13 patients from the ileostomy group (2 for serious complications after surgery, 9 for poor mental state after surgery, 1 for confirmed consciousness disorder after surgery and 1 for permanent stoma) and 4 patients from the colostomy group (3 for serious complications after surgery and 1 for permanent stoma) were excluded. Finally, 25 ileostomy patients (median age 42 years, ranging from 22 to 76 years) and 25 colostomy patients (median age 44 years, ranging from 18 to 70 years) were selected for the study. See Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow chart for patients' enrolment according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study.

3.2. Comparison of Clinical Data Between Colostomy and Ileostomy Groups

Based on clinical data, there were no statistically significant differences in gender, age distribution and causes for stoma surgery between the two groups. According to odds ratio, the colostomy group had a higher ratio of males, while the ileostomy group had a higher ratio of patients below 50 years old and a higher ratio of stoma surgery for tumour‐related reasons. The anastomotic healing rate 1 week postoperatively in the ileostomy group (20/25, 80%) was significantly higher than that in the colostomy group (13/25, 52%) (p = 0.037). According to risk ratio, the incidence of delayed healing in the colostomy group was 2.4 times that in the ileostomy group. The regular defecation rate postoperatively in the ileostomy group (14/25, 56%) was significantly lower than that in the colostomy group (21/25, 84%) (p = 0.031). Risk ratio indicated that the incidence of abnormal intestinal motility in the colostomy group was 0.36 times that in the ileostomy group. There was no significant difference in the number of daily bowel movements, the difficulty of self‐care for the healing site postoperatively and the incidence of stoma‐related complications between the ileostomy and colostomy groups. See Table 1

TABLE 1.

Comparison of clinical data between colostomy and ileostomy groups.

| Clinical characteristic | Ileostomy group (25 cases) | Colostomy group (25 cases) | χ2 | p | OR | RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.368 | 0.544 | 1.45 | |||

| Male | 16 | 18 | ||||

| Female | 9 | 7 | ||||

| Age | 0.725 | 0.395 | 0.62 | |||

| < 50 | 15 | 12 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 10 | 13 | ||||

| Causes for stoma surgery | 0.764 | 0.382 | 0.60 | |||

| Tumour | 17 | 14 | ||||

| Non‐tumour | 8 | 11 | ||||

| Stoma anastomotic healing time (weeks) | 4.367 | 0.037 | 2.4 | |||

| < 1 | 20 | 13 | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 5 | 12 | ||||

| Bowel movement status | 4.667 | 0.031 | 0.36 | |||

| Regular | 14 | 21 | ||||

| Irregular | 11 | 4 | ||||

| Counts of bowel movements per day | 2.381 | 0.123 | 0.50 | |||

| < 4 | 15 | 20 | ||||

| ≥ 4 | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Nursing situation | 0.595 | 0.440 | 1.67 | |||

| Self‐care ability | 22 | 20 | ||||

| Unable to self‐care | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Stoma‐related complications | 0.085 | 0.771 | 1.07 | |||

| No | 10 | 9 | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 16 |

3.3. Quality of Life Scale

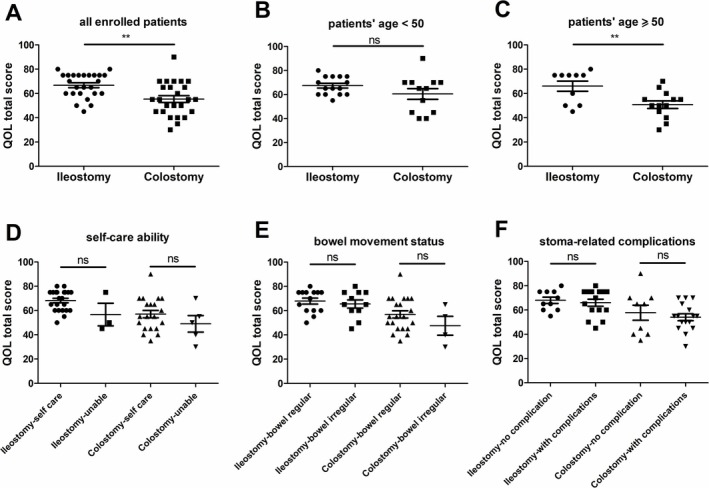

Based on the QOL assessment results: the rate of good tolerance to the odour of stoma faeces in the ileostomy group was 72% (18/25), while in the colostomy group, it was 28% (7/25). The ileostomy group had a significantly higher tolerance to the odour of stoma faeces compared to the colostomy group (p = 0.002). The rate of good postoperative appetite in the ileostomy group was 64% (16/25), with 36% (9/25) experiencing a slight impact on appetite. In the colostomy group, the rate of good postoperative appetite was 52% (13/25), with 48% (12/25) experiencing a slight impact on appetite. The postoperative appetite in the ileostomy group was significantly better than that in the colostomy group (p = 0.002). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of willingness to purchase stoma appliances, freedom of movement, clothing choices, daily exercise, stoma accidents, daily work, personal hygiene and sexual relationships (p > 0.05). The total score showed that the ileostomy group had a significantly better overall postoperative quality of life than the colostomy group (p = 0.002). When age was considered, the difference in postoperative quality of life was also significant in the subgroup of patients aged 50 years or older (p = 0.007). Although there was no statistical difference in patients under 50 years old, the trend of better postoperative life quality in the ileostomy group could be observed as well. We further analysed QOL for subgroups of different clinical characteristics, but no significant difference was observed referring to the self‐care ability, the bowel movement status, and the stoma‐related complications status. See Table 2 and Figure 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of quality of life (QOL) between colostomy and ileostomy groups.

| QOL options | Patient responses | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Neutral | Bad | ||

| Stoma appliances purchasing | No issues | Some difficulties | Unable to purchase | |

| Ileostomy group | 15 | 7 | 3 | 0.093 |

| Colostomy group | 13 | 3 | 9 | |

| Odour of stoma faeces | No issues | Tolerable | Intolerable | |

| Ileostomy group | 18 | 7 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Colostomy group | 7 | 12 | 6 | |

| Appetite | No issues | Slight impact | No appetite | |

| Ileostomy group | 16 | 9 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Colostomy group | 13 | 3 | 9 | |

| Freedom of movement | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 8 | 13 | 4 | 0.600 |

| Colostomy group | 7 | 11 | 7 | |

| Clothing choices | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 5 | 17 | 3 | 0.640 |

| Colostomy group | 6 | 14 | 5 | |

| Daily exercise | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 21 | 1 | 3 | 0.243 |

| Colostomy group | 18 | 0 | 7 | |

| Stoma accidents | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

| Ileostomy group | 13 | 11 | 1 | 0.320 |

| Colostomy group | 13 | 8 | 4 | |

| Daily work | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 7 | 11 | 7 | 0.820 |

| Colostomy group | 6 | 10 | 9 | |

| Personal hygiene | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 17 | 7 | 1 | 0.060 |

| Colostomy group | 10 | 9 | 6 | |

| Sexual relationships | No issues | Slight impact | Severe impact | |

| Ileostomy group | 6 | 1 | 18 | 0.300 |

| Colostomy group | 9 | 3 | 13 | |

| Total score | Good (71–100) | Satisfied (31–70) | Unacceptable (0–30) | |

| Ileostomy group | 11 | 14 | 0 | 0.003 |

| Colostomy group | 1 | 23 | 1 | |

FIGURE 2.

Total score of QOL questionnaire. (A) All enrolled patients; (B) patients under 50 years old; (C) patients aged 50 years or older; (D) patients with different self‐care ability; (E) patients with different bowel movement status; (F) patients of different stoma‐related complication status.

4. Discussion

In recent years, with advances in minimally invasive surgical techniques and precise diagnostic and treatment technologies, stoma surgeries, including ileostomy and colostomy, have provided essential intestinal diversion for patients with diseases such as bowel cancer, intestinal trauma, inflammatory bowel disease and anastomotic leaks. Although there is no significant difference in the overall complication rates between temporary colostomy and temporary ileostomy during the disease course, each group has unique complications. Choosing the appropriate type of stoma can further reduce the occurrence of stoma complications. For example, female patients should avoid colostomy, and patients with impaired renal function should avoid ileostomy (Yang et al. 2024). However, some stoma patients may experience psychological changes due to alterations in their body structure, leading to a sense of social isolation to some extent (Şengül et al. 2021). While preoperative psychological counselling, postoperative care and psychological support from specialised nursing teams can alleviate psychological issues to some degree, different stoma types still significantly affect the overall quality of life of patients.

Although there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of willingness to purchase stoma appliances, in clinical practice, we noticed that the difficulties in purchasing stoma bags may not be related to economic reasons. This might be due to the formed stools in colostomy leading to stoma bag‐related accidents, such as leakage and rupture, thus increasing the replacement frequency and the cost of purchasing bags (colostomy 7–8 year patients need to wear stoma bags long‐term post‐surgically, whereas ileostomy patients do not require stoma bags after reversal).

A study also used the Stoma‐QOL to assess the quality of life of patients at 1, 2, 4 and 8 weeks after discharge. Their results showed that the patient's quality of life scores gradually improved over time, but the main concerns were focused on clothing choices and stoma‐related accidents (Johnson et al. 2020). Compared to their results, we observed most patients chose slight impact in clothing choices in both the ileostomy group and the colostomy group, which did not seem to be too bothersome.

Additionally, ileostomy faeces were less bothersome than colostomy faeces, and their odour was easier to tolerate, causing less disturbance to patients' appetite. The similar result in patients' appetite difference after surgery was also reported in one study, showing that the ileostomy group had better appetite recovery and restoration (Silva et al. 2003). Compared to the colon, the blood supply to the terminal ileum was richer, making ileostomy less prone to postoperative bowel ischaemia, collapse and other issues, resulting in faster anastomotic healing and less collateral damage during reversal (Canova et al. 2013; Palumbo et al. 2020; Ayaz and Kubilay 2009). In colorectal cancer, temporary ileostomy is currently more common than colostomy, possibly due to the lower incidence of postoperative prolapse and the social barriers caused by the odour of colostomy faeces (Ge et al. 2023). These findings suggest the need to strengthen postoperative care for colostomy patients, such as focusing on cleaning the colostomy, reducing the odour of faeces, adjusting the taste of dishes to improve appetite, enhancing nutritional supply and helping colostomy patients recover sooner. It is also crucial to guide the families of colostomy patients to master proper stoma nursing methods and address the psychological issues caused by the aforementioned discomforts to improve their quality of life.

Most stoma patients experienced decreased libido postoperatively (Ayaz and Kubilay 2009). In our study, we observed similar results. Both groups reported issues with sexual relationships postoperatively due to factors such as the inconvenience of stoma appliances, poor hygiene habits and psychological changes. According to the QOL scale, 18 ileostomy patients (72%) and 13 colostomy patients (52%) completely abandoned sexual activity. Ileostomy patients avoided sexual activity more than colostomy patients, possibly because ileostomy faeces were more liquid and require more frequent stoma bag changes, causing greater inconvenience.

The total score of QOL indeed showed that the ileostomy group had a significantly better overall postoperative quality of life than the colostomy group, especially in the elderly subgroup. The reasons for this difference may be due to differences in stool properties, bacterial density and psychological acceptance and may also be related to differences in surgical stoma size, anatomical position, and physiological function of the ileum and colon. Relevant nursing staff should pay attention to these factors as well.

It should be emphasised that this study only compared the overall QOL of patients after surgery. The purpose was to guide nursing staff to carry out individualised and targeted nursing work. It has no guiding value for the choice of surgery. The specific surgical choice of patients should still strictly follow the corresponding indications and contraindications. The limitations of this study are that the data were collected from a single centre and the lack of long‐term postoperative follow‐up. Therefore, the conclusion that the QOL of the ileostomy group is better than that of the colostomy group has certain value, but the generally recognised conclusion still requires multi‐centre joint research to reduce bias. Future studies on postoperative QOL assessment should not only focus on the differences in postoperative care for patients with different surgical procedures, but also further explore the differences in nursing needs for patients at different stages after surgery.

5. Conclusions

In summary, compared to the colostomy group, the ileostomy group had shorter anastomotic healing times, faster recovery of bowel motility and appetite postoperatively, better tolerance to the odour of stoma faeces, and an overall higher postoperative quality of life. Therefore, in nursing care, it is necessary to strengthen the focus on the postoperative diet and stoma hygiene of colostomy patients to accelerate their recovery and improve their postoperative quality of life. Additionally, attention should be paid to the psychological counselling of colostomy patients to help them reintegrate into society as soon as possible.

6. Relevance to Clinical Practice

Different causes of the disease and different general conditions of the patients can lead to differences in the surgeon's choice of ostomy procedure. Nurses and other healthcare professionals should be aware of the differences in surgical techniques for patients with ostomy procedures, and provide more targeted and personalised care based on the patient's surgical condition. Nursing work should strengthen attention to postoperative diet and ostomy hygiene care in patients with colostomy, helping to accelerate their postoperative recovery and improve their postoperative quality of life.

Author Contributions

Mei Wang: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing, data curation, formal analysis. Lihong Dai: supervision, methodology, formal analysis, project administration. Xia Fang: validation, investigation. Yan Zheng: validation, investigation. Yuanhao Shen: writing, data curation, formal analysis. Yang Yu: resources, supervision, funding acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the funding from the Interdisciplinary Youth Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. YG2022QN069).

Funding: This work was supported by the Interdisciplinary Youth Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. YG2022QN069).

Contributor Information

Lihong Dai, Email: dailhshgh87@gmail.com.

Yang Yu, Email: shmuyuyang@163.com.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ayaz, S. , and Kubilay G.. 2009. “Effectiveness of the PLISSIT Model for Solving the Sexual Problems of Patients With Stoma.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 18: 89–98. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, M. J. , van Knippenberg F. C., Dulmen A. M., Borne H. W., and Berge Henegouwen G. P.. 1997. “Survival and Psychosocial Adjustment to Stoma Surgery and Nonstoma Bowel Resection: A 4‐Year Follow‐Up.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 42, no. 3: 235–244. 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonill‐de‐las‐Nieves, C. , Celdrán‐Mañas M., Hueso‐Montoro C., Morales‐Asencio J. M., Rivas‐Marín C., and Fernández‐Gallego M. C.. 2014. “Living With Digestive Stomas: Strategies to Cope With the New Bodily Reality.” Revista Latino‐Americana de Enfermagem 22: 394–400. 10.1590/0104-1169.3208.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley, J. , McMullen C. K., Hornbrook M. C., et al. 2013. “Spiritual Well‐Being in Long‐Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors With Ostomies.” Psycho‐Oncology 22: 2513–2521. 10.1002/pon.3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canova, C. , Giorato E., and Roveron G.. 2013. “Validation of a Stoma‐Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire in a Sample of Patients With Colostomy or Ileostomy.” Colorectal Disease 15: e692–e698. 10.1111/codi.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavriilidis, P. , Azoulay D., and Taflampas P.. 2019. “Loop Transverse Colostomy Versus Loop Ileostomy for Defunctioning of Colorectal Anastomosis: A Systematic Review, Updated Conventional Meta‐Analysis, and Cumulative Meta‐Analysis.” Surgery Today 49: 108–117. 10.1007/s00595-018-1708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z. , Zhao X., Liu Z., et al. 2023. “Complications of Preventive Loop Ileostomy Versus Colostomy: A Meta‐Analysis, Trial Sequential Analysis, and Systematic Review.” BMC Surgery 23: 235. 10.1186/s12893-023-02129-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. , Kelly J., Jones Heath K., et al. 2020. “Enhancing Recovery: Raising Awareness of Everyday Struggles of Patients With Ostomies.” WCET Journal 40: 27–30. 10.33235/wcet.40.1.27-31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenderian, S. , Stephens E. K., and Jatoi A.. 2014. “Ostomies in Rectal Cancer Patients: What Is Their Psychosocial Impact?” European Journal of Cancer Care 23: 328–332. 10.1111/ecc.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc, M. A. , Akyol C., Gokmen D., Aydin D., Erkek A. B., and Kuzu M. A.. 2023. “Effect of Prehabilitation on Stoma Self‐Care, Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Patients With Stomas: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 66: 138–147. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. C. , Kanters A. E., Gunter R. L., et al. 2023. “Operative Management of Anastomotic Leak After Sigmoid Colectomy for Left‐Sided Diverticular Disease: Ileostomy Creation May Be as Safe as Colostomy Creation.” Colorectal Disease 25: 1257–1266. 10.1111/codi.16550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, K. L. , Boostrom S. Y., and Pemberton J. H.. 2013. “New Developments in Colorectal Surgery.” Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 29: 72–78. 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, H. B. , Park J., Fuzesi S., and Temple L. K.. 2012. “Rectal Cancer Patients' Quality of Life With a Temporary Stoma: Shifting Perspectives.” Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 55, no. 11: 1117–1124. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182686213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, V. , Mannino M., Coco O., and di Carlo I.. 2020. “Ileostomy: Still a Problem With Hopeful Perspectives.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons 230: 170. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, L. , Thorsen H., and Juul K.. 2005. “Development and Validation of a Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients With Colostomy or Ileostomy.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3: 62. 10.1186/1477-7525-3-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille, S. , Maalouf M. F., Penta R., et al. 2023. “The Impact of Restorative Proctectomy Versus Permanent Colostomy on Health‐Related Quality of Life After Rectal Cancer Surgery Using the Patient‐Generated Index.” Surgery 174: 813–818. 10.1016/j.surg.2023.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova, K. , Lee W., Shah S., Shah S., and Chandan V. S.. 2023. “Cost Benefit Analysis and Pathology Review of Ileostomy and Colostomy Specimens Processed Over a 20‐Year Period.” Human Pathology 141: 1–5. 10.1016/j.humpath.2023.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şengül, T. , Oflaz F., Odulozkaya B., Sengul T., and Altunsoy M.. 2021. “Disgust and Its Effect on Quality of Life and Adjustment to Stoma in Individuals With Ileostomy and Colostomy.” Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing 29, no. 3: 303–311. 10.5152/FNJN.2021.20198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M. A. , Ratnayake G., and Deen K. I.. 2003. “Quality of Life of Stoma Patients: Temporary Ileostomy Versus Colostomy.” World Journal of Surgery 27, no. 4: 421–424. 10.1007/s00268-002-6699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrivankova, V. W. , Richmond R. C., and Woolf B. A. R.. 2021. “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE‐MR Statement.” Journal of the American Medical Association 326: 1614–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, S. , Suzuki H., and Miura T.. 2022. “Obstructive and Secretory Complications of Diverting Ileostomy.” World Journal of Gastroenterology 28: 6732–6742. 10.3748/wjg.v28.i47.6732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, S. , Suzuki H., Miura T., et al. 2023. “Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Ileostomy Complications: An Updated Review.” Cureus 15: e34289. 10.7759/cureus.34289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. 2012. “Patient Stoma Care: Educational Theory in Practice.” British Journal of Nursing 21: 786–794. 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.13.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. W. , Huang S. C., Cheng H. H., et al. 2024. “Protective Loop Ileostomy or Colostomy? A Risk Evaluation of all Common Complications.” Annals of Coloproctology 40, no. 6: 580–587. 10.3393/ac.2022.00710.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zewude, W. C. , Derese T., Suga Y., and Teklewold B.. 2021. “Quality of Life in Patients Living With Stoma.” Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences 31, no. 5: 993–1000. 10.4314/ejhs.v31i5.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.