Abstract

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominantly (AD)-inherited disease that results from pathogenic variants in the Fibrillin 1 (FBN1) gene, and is characterised by tall stature, elongated limbs and digits, lens abnormalities and aortic root dilatation, aneurysms and dissection, but milder forms also occur. Radiological imaging suggests that Marfan syndrome affects between one in 3000 and 5000 of the population. The aim of this study was to determine the population frequency of Marfan syndrome from the number of predicted pathogenic FBN1 changes found in a normal database. FBN1 variants were downloaded from gnomAD v2.1.1 and annotated with ANNOVAR. The population frequency was determined from the number of pathogenic null and structural variants, and the number of predicted pathogenic missense changes classified by rarity and computational scores. This population frequency was then compared with the frequencies in the control subset, and from gnomAD variants assessed as Pathogenic or Likely pathogenic in the ClinVar or LOVD databases. Our strategy identified predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants in one in 416 individuals, which was confirmed in the control subset (one in 356, p NS). Predicted pathogenic variants were most common in East Asian people (one in 243, p < 0.0001) and least common in Ashkenazim (one in 5185, p = 0.0082). The population frequencies based on pathogenic variants in the ClinVar or LOVD databases were one in 718 and one in 1014 respectively. Null variants which are associated with aortic aneurysms affected only one in 8624. Thus, Marfan syndrome is more common than previously recognised. Emergency departments and cardiac clinics in particular should be aware of undiagnosed Marfan syndrome and its cardiac risks, but many of those affected still have a milder phenotype.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-93832-6.

Introduction

Marfan syndrome (MIM154700) is a genetic disease that primarily affects connective tissue in the skeleton, cardiovascular system and eye1,2. It results from pathogenic variants in the gene for Fibrillin-1 (FBN1)3–6 which codes for the main component of the extracellular microfibrils that form elastic fibres7,8. Fewer than 6% of patients have disease from a pathogenic variant in the other affected genes, TGFBR1 and TGFBR29. Marfan syndrome demonstrates autosomal dominant (AD) inheritance that is highly penetrant but with variable expression even within individual families (Table 1)10. The disease occurs worldwide11.

Table 1.

Marfan syndrome and FBN1 variants.

| Disease | Gene and protein features | Gene function | Clinical features and risks | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marfan syndrome (MIM154700) Autosomal dominant | FBN1 (Fibrillin 1) 65 exons, encodes 350kDa fibrillin; caused by all types of variants distributed throughout the gene, by a loss of function mechanism | Production of glycoproteins in the extracellular matrix; structural components of microfibrils that bind calcium ions | Cardiac, skeletal, ocular manifestations: aortic aneurysms, arachnodactyly, and ectopic lens. Risk or aortic dissection and aneurysm rupture | Hypertension control, and surgical interventions for the aneurysms |

Marfan syndrome is characterised by tall stature, elongated limbs and digits, chest wall and spine abnormalities, cardiovascular anomalies with thoracic and aortic aneurysms, aneurysm dissection and rupture, as well as myopia and ectopic lens12. The diagnosis is usually made using the revised Ghent Nosology based on family history, clinical examination, aortic imaging and, in some cases, genetic testing13. Affected individuals are particularly susceptible to lethal complications from aortic dissection and ruptured aneurysms14,15. Treatment includes control of hypertension, and lifestyle factors1,16,17. Surgical interventions include prophylactic aortic and valvular repair.

However some individuals with Marfan syndrome have only isolated features such as an ectopic lens, ascending aortic aneurysm or skeletal abnormalities. Milder forms are recognised increasingly. Affected individuals are not necessarily taller than average. Mitral valve prolapse occurs in about half but mitral regurgitation is often mild18,19. A cardiomyopathy unrelated to valve disease may occur20. Some of those affected have pectus excavatum, scoliosis, arachnodactyly20, or emphysema with upper lobe bullae that predispose to spontaneous pneumothorax. Joint hypermobility and high arched palate also occur but are considered non-specific13.

Genetic testing represents the gold standard for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. Simple ClinVar (https://simple-clinvar.broadinstitute.org/) indicates that Pathogenic and Likely pathogenic variants in FBN1 occur throughout the gene and include both missense and nonsense changes. Variants are typically different in each family21. Null variants appear to be associated more often with aortic aneurysms and rupture22. Many missense changes occur within the 47 repeated epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains or from cysteine substitutions that interfere with disulfide bond formation and Fibrillin1 expression23,24.

Marfan syndrome is reported to affect between one in 3000 and 5000 of the population25–27, based on radiological phenotyping4,28 or clinical examination25,27. However these are probably underestimates because of the variable phenotype. Nevertheless it remains important to diagnose Marfan syndrome because of the cardiac risk. Genetic testing makes the diagnosis with certainty, and allows early treatment and monitoring, but the interpretation of FBN1 variants may be problematic.

This study determined the population frequency of Marfan syndrome from assessing genetic variants in the gnomAD database for pathogenicity using the principles underlying the ACMG/AMP guidelines29 but without having access to clinical data. Similar but slightly different and less rigorous strategies have been used previously to estimate the population frequencies of many other rare genetic diseases, including AD Polycystic Kidney Disease, XL and AD Alport syndrome, Fabry disease, Gitelman disease, mucopolysaccharidoses and Menke syndrome30–35. In at least some of these cases, this approach has been confirmed with an independent non-genetic method such as histology or biochemical testing30,35. In addition, variants were independently identified as Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic in the ClinVar or LOVD FBN1 databases where clinical data and, in the case of ClinVar, the ACMG criteria, were used in the assessments. However both ClinVar and LOVD underestimate the population frequencies because, unlike our strategy, they have not assessed all variants in gnomAD.

Methods

Population database

The population frequency of Marfan syndrome was estimated using genetic variants (GRCh37/hg19) from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v2.1.1, www.gnomAD.broadinstitute.org, n = 141,456) and its control subset (gnomAD v2.1.1. n = 52,806) (canonical transcript: ENST00000316623.5). gnomAD is an aggregated database with information from 125,748 Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and 15,708 Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) samples. Participants were unrelated individuals with adult-onset illnesses such as diabetes, or cardiac or neuropsychiatric diseases, but not with severe paediatric conditions. Sex, age and ancestry but not clinical data were available. Databases were initially examined between July 2023 and April 2024, and reviewed between April and June, and again in December 2024.

Written informed consent had been provided at recruitment by all participants in gnomAD for the use of their anonymised data in the original studies so that this project did not require additional IRB approval. All gnomAD data is freely available on line and no permissions or registrations are required for access.

Annotation

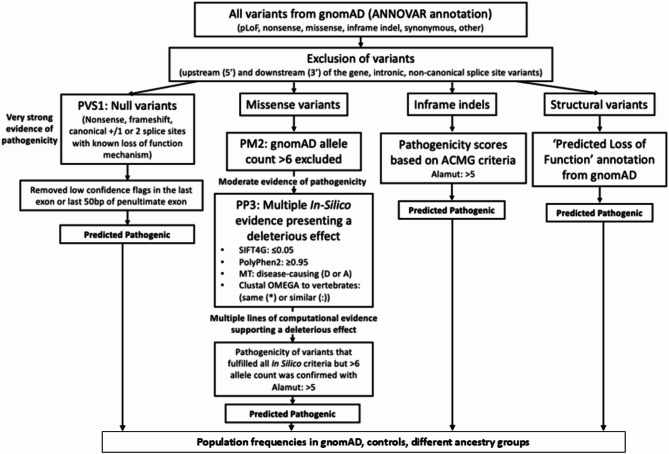

Variants in the FBN1 gene from gnomAD were downloaded, annotated in ANNOVAR (https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/), and assessed for pathogenicity based on whether they were structural or null, and in the case of missense changes, whether they were rare, pathogenic in three computational tools and affected an amino acid that was conserved in vertebrates (Fig. 1). This population frequency was then compared with that found in the Control subset, or from the number of variants found in gnomAD that were assessed Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic by the ClinVar or LOVD databases.

Fig. 1.

Strategy for identifying Predicted pathogenic variants in FBN.

Filtering processes

Variants that were located in the 5′ or 3′ UTR, in the intronic or non-canonical splice regions, or were synonymous were excluded.

Structural variants

Structural variants were only available for a subset of 10,847 individuals, and any considered pathogenic in gnomAD were classified here as predicted pathogenic.

Null variants

Null variants with any allele count including nonsense (stop gained), frameshift and canonical splice site variants were classified as predicted pathogenic. Null variants in the last exon or last 50 nucleotides of the penultimate exon (according to Alamut, Sophia Genetics, https://www.sophiagenetics.com/) were excluded since they were assumed to not result in nonsense-mediate decay36.

Missense variants

Missense variants were predicted pathogenic if they occurred in fewer than 6 individuals in gnomAD; and were pathogenic in all bioinformatic prediction tools: PolyPhen-2 (PP2, score ≥ 0.95, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT4G, score ≤ 0.05 from Varsome, https://varsome.com/), MutationTaster (MT, prediction: ‘Disease-causing, D or A https://www.mutationtaster.org/) and if they affected an amino acid that was conserved in vertebrates (humans, mice and chickens). Conservation was assessed with Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) based on reference sequences downloaded from Ensembl (http://asia.ensembl.org/index.html), where residues had the same or similar physicochemical properties (indicated with an asterisk (*) or colon (:).

Our assessment strategy for ‘predicted pathogenic missense variants’ was validated as follows. Twenty Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic and 20 Benign or Likely Benign missense variants were selected randomly from ClinVar and LOVD and assessed according to our strategy for predicted pathogenicity. The sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative predictive values were then calculated for both ClinVar and LOVD (Table 2). All values were at least 80%.

Table 2.

Validation of filtering strategy for pathogenic variants in FBN1.

| Database | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (PPV) (%) | Negative predictive value (NPV) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBN1 | ClinVar (B/LB n = 19/20, P/LP n = 16/20) | 80 | 95 | 94 | 82 |

| LOVD (B/LB n = 20/20, P/LP n = 20/20) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

B: Benign; LB: Likely Benign; P: Pathogenic; LP: Likely Pathogenic.

Missense variants were also assessed by REVEL (score > 0.932) which has the best performance for distinguishing pathogenic from rare neutral variants with allele frequencies less than 0.5%37,38.

The population frequencies were then calculated based on the assumption that each predicted pathogenic variant was found in only one individual.

Population frequencies of Predicted pathogenic variants in different ancestries

Population frequencies of predicted pathogenic variants were calculated in people from all 8 ancestries available in gnomAD (African/African American, Latino/Admixed American, Ashkenazi Jewish, East Asian, Finnish, European (Non-Finnish), South Asian, and Others).

Population frequencies of Marfan syndrome using different databases

The population frequencies of predicted pathogenic variants were also calculated based on how often variants assessed as Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic in ClinVar and LOVD databases were also found in gnomAD (ClinVar https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/; LOVD, https://www.lovd.nl/). Variants in ClinVar classified as Conflicting with both a VUS and Pathogenic or Likely pathogenic assessment were considered pathogenic for the calculation. Variants were included even if the allele were found more than 5 times because the initial assessments had often included clinical data that increased the likelihood of being correct.

Statistical analysis

Results were compared with Chi-square with Yates correction (Graph pad).

Results

Predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants in overall gnomAD cohort

The FBN1 gnomAD dataset comprised 1157 variants including 21 structural, 17 null and 1119 missense changes from a mean of 241,491 alleles or 120,745 individuals (Supplementary material Tables S1 and S2 includes Filtering FBN1 for predicted pathogenic variants; and Assessment of our Filtering strategy).

Predicted pathogenic variants comprised no structural changes, but 14 null and 170 predicted pathogenic missense variants. The 14 null variants corresponded to a population frequency of one in 8624. Altogether there were 182 predicted pathogenic variants in 290 people which corresponded to a population frequency of 290/120,745 or one in 416 (0.24%) (Table 3). When the missense variants identified by a highly stringent REVEL score (> 0.932) were included instead (42 in 76 individuals) this corresponded to a population frequency of 90/120,745 or one in 1588 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Predicted population frequency of pathogenic FBN1 variants in gnomAD.

| Pathogenic structural variants | Predicted pathogenic null variants | Predicted pathogenic missense variants | Population frequency of predicted pathogenic variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | No. of variants | No. of people | No. of variants | No. of people | No. of variants | No. of people | Frequency |

| 14 | 14 | 171 | 279 | 182 | 290 | 290/120,745 (0.24%) or one in 416 | |

Table 4.

FBN1 population frequencies using different strategies.

| REVEL | Predicted pathogenic variants | 42 variants in 76 people (plus 14 null variants) |

| Frequency |

90/120,745 (0.07%) = one in 1588 people |

|

| Control subset | Predicted pathogenic variants | 112 variants in 148 people |

| Frequency |

148/52,806 (0.28%) = one in 356 people |

|

| ClinVar | Predicted pathogenicvariants | 52 variants in 168 people |

| Frequency |

168/120,745 (0.14%) = one in 718 people |

|

| LOVD | Predicted pathogenic variants | 21 variants in 119 people |

| Frequency |

119/120,745 (0.10%) = one in 1014 people |

Population frequencies are in bold.

Predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants in gnomAD control subset

The Control subset included 112 predicted pathogenic variants in 148 people in a cohort of 52,806 individuals. This was equivalent to a population frequency of 148/52,806 (0.28%) or one in 356 which was not different from the results for the overall gnomAD cohort (Chi square = 1.399, p value = 0.24) (Table 4).

Predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants different ancestries in gnomAD

The population frequencies of predicted pathogenic variants varied in people of different ancestries. Predicted pathogenic variants were more common in people of East Asian (one in 243, p < 0.0001) and South Asian (one in 300, p = 0.0009) backgrounds than in Europeans (one in 525). Predicted pathogenic variants were least common in Ashkenazim (one in 5185, p = 0.0082) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Predicted pathogenic null and missense variants in people of different ancestries.

| FBN1 | Predicted pathogenic null variants | Predicted pathogenic missense variants | Total Predicted pathogenic variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestry gnomAD v.2.1.1. (n = 141,456) | |||

|

African/African American (n = 12,487) |

One variant in 1 person 1/12,487 = one in 12,487 |

19 variants in 24 people 24/12,487 = one in 520 |

20 variants in 25 people 25/12,487 = one in 499 (p = 0.014) |

|

Latino/Admixed American (n = 17,720) |

None |

21 variants in 36 people 36/17,720 = one in 492 |

21 variants in 36 people 36/17,720 = one in 492 (p = 0.06) |

|

Ashkenazi Jewish (n = 5185) |

None |

One variant in 1 person 1/5185 = one in 5185 |

One variant in 1 person 1/5185 = one in 5185 (p = 0.008) |

|

East Asian (n = 9977) |

None |

21 variants in 41 people 41/9977 = one in 243 |

21 variants in 41 people 41/9977 = one in 243 (p < 0.0001) |

|

Finnish (n = 12,562) |

One variant in 1 person 1/12,562 = one in 12,562 |

8 variants in 12 people 12/12,562 = one in 1,046 |

9 variants in 13 people 13/12,562 = one in 966 (p = 0.04) |

|

European (n = 64,603) |

6 variants in 6 people 6/64,603 = one in 10,767 |

89 variants in 117 people 117/64,603 = one in 552 |

95 variants in 123 people 123/64,603 = one in 525 |

|

South Asian (n = 15,308) |

5 variants in 5 people 5/15,308 = one in 3061 |

37 variants in 46 people 46/15,308 = one in 332 |

42 variants in 51 people 51/15,308 = one in 300 (p = 0.0009) |

|

Other (n = 3614) |

One variant in 1 person 1/3614 = one in 3614 |

2 variants in 2 people 2/3614 = one in 1807 |

3 variants in 3 people 3/3614 = one in 1204 (p = 0.21) |

Comparisons performed with Chi squared test with Yate’s correction.

Population frequencies are in bold.

Predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants according to different Pathogenic variant databases

ClinVar

Fifty-two Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variants in ClinVar were found in 168 individuals in gnomAD. This corresponded to a population frequency of 168/120,745 or one in 718.

LOVD

Twenty-one Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variants in LOVD were found in 119 individuals in gnomAD. This corresponded to a population frequency of 119/120,745 or one in 1014 (Table 4).

Discussion

This study used diverse approaches to demonstrate that predicted pathogenic variants in the FBN1 gene for Marfan syndrome are more common than the previous estimates of one in three to five thousand. Our strategy based on identifying predictive pathogenic or rare damaging variants in FBN1 found that Marfan syndrome potentially affected one in 416 of the gnomAD population and one in 356 of its control subset. An alternative approach using highly stringent REVEL scores for missense variants found a population frequency of one in 1588. Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic assessments in ClinVar or LOVD corresponded to population frequencies of one in 718 or 1014 respectively. These results suggest that the population frequency of predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants and Marfan syndrome affects a range of individuals from one in 416 to one in 1588. However not everyone with a predicted pathogenic variant develops the characteristic Marfan features because of incomplete penetrance and variable expression. Some may have the milder disease that is recognised increasingly. Expression varies even in individual members of the same family.

Each of the approaches used here for estimating the population frequency of Marfan syndrome had strengths and weaknesses, with some likely to result in an overestimation such as our strategy, and others an underestimation, such as ClinVar and LOVD. Missense variants are always more difficult to assess computationally for pathogenicity. Our approach for missense variants used a more rigorous threshold than other assessments (rarity, positive in three computational tools, and affecting a conserved residue)30–35. Our criteria performed well in the validation studies (Table 2), and demonstrated an excellent concordance with the ClinVar and LOVD classifications (S Table 2). However when a high REVEL score (> 0.932)37 was used instead for missense variants, the population frequency was one in 1588, which was even less than for ClinVar and LOVD.

Both the ClinVar and LOVD datasets are valuable because their assessments rely on multiple submissions from diagnostic laboratories to confirm pathogenicity in individuals where Marfan syndrome is suspected clinically. ClinVar was established after the publication of the ACMG guidelines36 and uses them in their assessments. The ClinVar assessments are considered accurate but fewer than half of all the gnomAD FBN1 variants have a ClinVar grading, and most of these are ‘one star’ from a single submitter. In contrast, the LOVD database includes submissions made prior to the ACMG publication and before large variant datasets were available that allowed rare variants to be identified. Again, LOVD does not include an assessment for each FBN1 variant in gnomAD and, like ClinVar, underestimates the number of pathogenic variants and therefore the population frequency. Our study did not formally evaluate the number of pathogenic variants from the HGMD and UMD-FBN1 databases for Marfan syndrome because they both include many variants classified as ‘pathogenic’ but also present in large numbers of individuals.

Although gnomADv.2.1.1 included samples from participants with known cardiac disease there was no difference in the number with a predicted pathogenic FBN1 variant (one in 416) and in the control cohort (one in 356, pNS) without known cardiac disease.

The finding with our strategy that Marfan syndrome appears to be more common than previously estimated does not mean that aortic disease and rupture are overlooked. Our study found that null variants affected one in 8624 individuals and it is these variants that are usually associated with a more severe phenotype and an increased likelihood of aortic dissection and rupture22. No structural variants were present, in part because so few gnomAD samples were examined with Whole Genomic Sequencing. However missense variants were found in our study nearly 20 times as often as null changes, and missense variants are typically associated with less severe clinical features which may explain the difference from the previous population frequencies39. Skeletal anomalies, aortic dilatation and lens abnormalities may be absent but mitral valve prolapse, mitral regurgitation or joint hyperflexibility occur.

Indeed the population frequency of Marfan syndrome calculated with our strategy may be an underestimate because up to 10% of cohorts with clinical features of Marfan syndrome have no pathogenic variant identified in FBN1 40. Instead they have disease caused by variants in other genes (TGFBR1, TGFBR2)41, or structural variants, deletions, or intronic regulatory sequences in FBN1 that are not detected with Whole Exome Sequencing.

Overall, predicted pathogenic FBN1 variants were found most often in people of East and South Asian ancestries, and least often in Ashkenazim which may be explained by their cultural and geographic isolation, by genetic drift or by the different numbers of patients from these populations who were sequenced. Null variants were absent from both the Ashkenazim and Latino/Admixed American ancestries. Previous studies have not found any racial predisposition for Marfan syndrome42.

The strengths of this study were the use of the large gnomAD database; the confirmation with different criteria; and the use of different variant datasets. The study’s limitations were the use of Whole Exome Sequencing in this version of gnomAD; the lack of clinical data; the difficulty with assessing missense variants; and the incompleteness of the ClinVar and LOVD databases.

Obtaining a more accurate population frequency of Marfan syndrome is important in order to improve clinician awareness of the disease, and its cardiac risks; for health systems, to assist with health service planning; and for pharmaceutical companies, to develop targeted treatments. This study suggests that the population frequency of Marfan syndrome is at least one in 718 people and possibly as common as one in 416. Many of those people with a predicted pathogenic missense variant in FBN1 may have a milder form of disease and indeed some may themselves have no manifestations but still pass the pathogenic variant on to their offspring with variable consequences.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank gnomAD, REVEL, ClinVar and LOVD for the use of their databases; the many patients who contributed to these databases; and the data contributors and developers of the in-silico tools used in this analysis (PP2, SIFT, Mutation Taster, Clustal Omega). KC undertook this project as part of her research towards an M Sc.

Author contributions

KC undertook the analysis, produced the tables and the first draft of the manuscript. MH helped KC with downloading the variants in ANNOVAR and with the analysis. JS devised the project, and produced the final manuscript. All authors had reviewed the final draft.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dietz, H. FBN1-Related Marfan Syndrome. In GeneReviews((R)) (eds Adam, M. P. et al.) (1993). [PubMed]

- 2.Mannucci, L. et al. Mutation analysis of the FBN1 gene in a cohort of patients with Marfan Syndrome: A 10-year single center experience. Clin. Chim. Acta501, 154–164 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucek, R. J., Noble, N. L., Gunja-Smith, Z. & Butler, W. T. The Marfan syndrome: A deficiency in chemically stable collagen cross-links. N. Engl. J. Med.305(17), 988–991 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byers, P. H. et al. Marfan syndrome: abnormal alpha 2 chain in type I collagen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA78(12), 7745–7749 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Kodolitsch, Y. & Robinson, P. N. Marfan syndrome: An update of genetics, medical and surgical management. Heart93(6), 755–760 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybczynski, M. et al. The spectrum of syndromes and manifestations in individuals screened for suspected Marfan syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A146A(24), 3157–3166 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinhardt, D. P. et al. Fibrillin-1: Organization in microfibrils and structural properties. J. Mol. Biol.258(1), 104–116 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, H., Hu, W. & Ramirez, F. Developmental expression of fibrillin genes suggests heterogeneity of extracellular microfibrils. J. Cell Biol.129(4), 1165–1176 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai, H. et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis of relevant four genes in 49 patients with Marfan syndrome or Marfan-related phenotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet A140(16), 1719–1725 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira, L. et al. A molecular approach to the stratification of cardiovascular risk in families with Marfan’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med.331(3), 148–153 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judge, D. P. & Dietz, H. C. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet366(9501), 1965–1976 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milewicz, D. M. et al. Marfan syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers7(1), 64 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeys, B. L. et al. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J. Med. Genet.47(7), 476–485 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aranda-Michel, E. et al. National trends in thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections in patients with Marfans and Ehlers Danlos syndrome. J. Card Surg.37(10), 3313–3321 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bitterman, A. D. & Sponseller, P. D. Marfan syndrome: A clinical update. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg.25(9), 603–609 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooke, B. S. et al. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med.358(26), 2787–2795 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milewicz, D. M., Dietz, H. C. & Miller, D. C. Treatment of aortic disease in patients with Marfan syndrome. Circulation111(11), e150-157 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rybczynski, M. et al. Frequency and age-related course of mitral valve dysfunction in the Marfan syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol.106(7), 1048–1053 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faivre, L. et al. Effect of mutation type and location on clinical outcome in 1,013 probands with Marfan syndrome or related phenotypes and FBN1 mutations: An international study. Am. J. Hum. Genet.81(3), 454–466 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alpendurada, F. et al. Evidence for Marfan cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail.12(10), 1085–1091 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du, Q. et al. The molecular genetics of Marfan syndrome. Int. J. Med. Sci.18(13), 2752–2766 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baudhuin, L. M., Kotzer, K. E. & Lagerstedt, S. A. Increased frequency of FBN1 truncating and splicing variants in Marfan syndrome patients with aortic events. Genet. Med.17(3), 177–187 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrijver, I., Liu, W., Brenn, T., Furthmayr, H. & Francke, U. Cysteine substitutions in epidermal growth factor-like domains of fibrillin-1: Distinct effects on biochemical and clinical phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet.65(4), 1007–1020 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, X. et al. Case report: Biochemical and clinical phenotypes caused by cysteine substitutions in the epidermal growth factor-like domains of fibrillin-1. Front. Genet.13, 928683 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groth, K. A. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and age at diagnosis in Marfan Syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.10, 153 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salik I, Rawla P. Marfan Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2023.

- 27.Ammash, N. M., Sundt, T. M. & Connolly, H. M. Marfan syndrome-diagnosis and management. Curr. Probl. Cardiol.33(1), 7–39 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha, H. I. et al. Imaging of Marfan syndrome: multisystemic manifestations. Radiographics27(4), 989–1004 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gudmundsson, S. et al. Variant interpretation using population databases: Lessons from gnomAD. Hum. Mutat.43(8), 1012–1030 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kondo, A. et al. Examination of the predicted prevalence of Gitelman syndrome by ethnicity based on genome databases. Sci. Rep.11(1), 16099 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kermond-Marino, A. et al. Population frequency of undiagnosed Fabry disease in the general population. Kidney Int. Rep.8(7), 1373–1379 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borges, P., Pasqualim, G., Giugliani, R., Vairo, F. & Matte, U. Estimated prevalence of mucopolysaccharidoses from population-based exomes and genomes. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis.15(1), 324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaler, S. G., Ferreira, C. R. & Yam, L. S. Estimated birth prevalence of Menkes disease and ATP7A-related disorders based on the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep.24, 100602 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanktree, M. B. et al. Prevalence estimates of polycystic kidney and liver disease by population sequencing. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.29(10), 2593–2600 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson, J. et al. Prevalence estimates of predicted pathogenic COL4A3-COL4A5 variants in a population sequencing database and their implications for Alport syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.32(9), 2273–2290 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med.17(5), 405–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pejaver, V. et al. Calibration of computational tools for missense variant pathogenicity classification and ClinGen recommendations for PP3/BP4 criteria. Am. J. Hum. Genet.109(12), 2163–2177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ioannidis, N. M. et al. REVEL: An ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet.99(4), 877–885 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baudhuin, L. M., Kotzer, K. E. & Lagerstedt, S. A. Decreased frequency of FBN1 missense variants in Ghent criteria-positive Marfan syndrome and characterization of novel FBN1 variants. J. Hum. Genet.60(5), 241–252 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loeys, B. et al. Comprehensive molecular screening of the FBN1 gene favors locus homogeneity of classical Marfan syndrome. Hum. Mutat.24(2), 140–146 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dietz, H. C. Marfan Syndrome GeneReviews (University of Washington, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keane, M. G. & Pyeritz, R. E. Medical management of Marfan syndrome. Circulation117(21), 2802–2813 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary files.