Abstract

Background

Take-out food consumption has adverse effects on public health, and previous studies have reported that frequent consumption of take-out food increases the risk of hypertension and heart disease. However, the status of take-out food consumption among pregnant women remains unclear. This study aimed to provide a comprehensive description of the present state of take-out food consumption among first-trimester pregnant women in Changsha and to investigate the factors influencing this behaviour.

Methods

We included 888 pregnant women in early pregnancy from a cross-sectional study (March–August 2022) conducted at Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care, Hunan Province, China. Electronic questionnaires were administered during early antenatal check-ups. The questionnaire included demographic information, health and lifestyle behaviours, pregnancy-related information, take-out food consumption, and anxiety and depression scales. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0, including nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis H tests and multivariate ordinal logistic regression, to explore the factors influencing take-out food consumption by first-trimester pregnant women.

Results

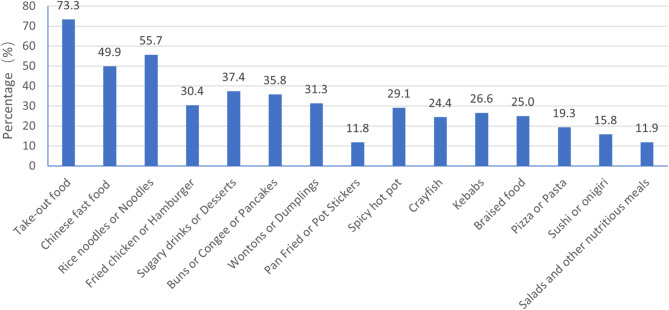

In Changsha, 73.3% of pregnant women consumed take-out food during early pregnancy. The top three types of take-out foods commonly consumed were rice noodles or noodles (55.7%), Chinese fast foods (49.9%), and sugary drinks or desserts (37.4%). The results of multivariate ordinal logistic regression analysis revealed that pregnant women with depression symptoms (odds ratio [OR] = 1.65, 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.18–2.32), higher education level (OR = 1.88, 95%CI:1.23–2.88), and higher online time (OR = 1.50, 95%CI:1.11–2.03) consumed take-out food more frequently in early pregnancy than those without depression symptoms, lower education level, and lower online time.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that take-out food consumption is common among first-trimester pregnant women in Changsha. Education level, depression symptoms, and online time are risk factors that may potentially influence the consumption of take-out food during early pregnancy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-22157-w.

Keywords: Pregnant women, Early pregnancy, Take-out food consumption, Influencing factors

Background

With the progress of society and the development of technology, under the influence of the “Internet+” model, take-out food consumption has gradually become integrated into people’s lives, changing their food consumption patterns. Take-out food refers to food items available from fast-food establishments that offer convenient delivery services and carryout options and require payment before a consumer receives food [1, 2]. A cross-sectional study in the United States revealed that more than 30% of adults and children consumed take-out food daily between 2015 and 2018 [3]. Some studies have reported that China has the highest number of consumers of online take-out foods worldwide [4, 5].

Issues related to food safety, particularly those associated with preparation procedures and hygiene conditions of take-out foods, have not been adequately addressed [6, 7]. Therefore, concerns regarding food hygiene and quality are increasing owing to issues such as substandard packaging, inadequate oversight of ingredient quality, insufficient control over delivery temperatures, and a lack of employee training. Additionally, some studies have indicated that in the process of eating take-out food, hundreds of microplastics may be inhaled, which can cause harm to the human body [8–10]. Take-out foods are energy-dense, nutrient-poor, and high in salt, sugar, and fat [11]. Moreover, a survey in the United States reported that all women had experienced and succumbed to at least one craving, with cravings for ‘sweet’ and ‘fast food’ being the most common. The frequency and consumption of cravings may increase the risk of excessive obesity [12]. Notably, take-out food consumption has adverse effects on public health, and most previous studies have reported that frequent consumption of take-out food increases the risk of hypertension [13] and heart disease [14].

Pregnancy represents a distinctive physiological period that demands heightened nutrition, as all nutrients necessary for foetal growth and development originate from the mother. Pregnant women must reserve nutrients for childbirth and subsequent secretion of breast milk. A study conducted in China revealed a close correlation between factors such as unhealthy eating and anxiety among pregnant women and the increased incidence of infant obesity [15]. However, some research indicates that pregnant women have limited awareness of healthy dietary guidelines during pregnancy [16], and dietary behaviours may shift toward unhealthy patterns during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [17], which may have potential impacts on the health of unborn infants [18]. Additionally, a large-scale birth cohort study in Japan demonstrated that the consumption of ready-made and frozen meals during pregnancy may increase the risk of stillbirth [19]. Another study conducted in the United States suggested that the consumption of meals not prepared at home may contribute to the risk of infertility in women [20].

Existing studies have primarily focused on the take-out food consumption patterns of college students and their influencing factors [21–24]. However, the status of take-out food consumption among pregnant women remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to outline the current status of take-out consumption and identify influencing factors among first-trimester pregnant women in Changsha.

Methods

Study design

This study is a cross-sectional study, which was conducted from March to August 2022 to investigate the current status of take-out food consumption and its influencing factors among pregnant women in early pregnancy at Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care, Hunan Province, China. We employed a self-designed, structured questionnaire to collect data through an on-site, self-administered survey. All participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, and signed informed consent was obtained.

Participants

Based on certain inclusion and exclusion criteria, pregnant women who underwent antenatal check-ups at the Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care between March and August 2022 were selected as study participants.

Inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) gestational week < 14 weeks; (3) planned regular obstetric check-ups and delivery at Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care; (4) agreed to participate in this study and signed an informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) severe neuropsychiatric or organic disease and (2) incomplete or indiscriminate completion of questionnaire entries. During the study period, 890 pregnant women participated in the research, with only 2 having incomplete information.

In total, 888 pregnant women were included in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (approval number: 2021 No. 278).

Survey tools

An on-site, self-administered electronic questionnaire was administered to the study participants by uniformly trained investigators. The self-administered questionnaire, named the ‘Maternal and Child Health Information Collection Form’. The questionnaire included demographic information, health and lifestyle behaviors, pregnancy-related information, take-out food consumption, and anxiety and depression scales. First, we summarized items based on a review of literature studies. Second, a panel discussion was organized with experts. Finally, we invited 20 pregnant women to pre-test using the initial questionnaire to validate all items. The Cronbach’s a of the final questionnaire was 0.84.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) consists of 10 questions. The EPDS can screen for postpartum depression in China and is now being used to screen for prenatal depression [25, 26]. Each question contains four options: “never”, “occasional”, “often”, and “always”, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. The total possible score was 30, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. A total score of 9 was used as the threshold for screening for depressive symptoms. A total score of ≥ 9 was used to determine the presence of depressive symptoms [27].

The Anxiety Self-Assessment Symptom Assessment Scale scores pregnant women on the frequency of their feelings during the last week [28]. The scale consisted of 20 questions. Level 1 indicates no or very little time, level 2 indicates little time, level 3 indicates more time, and level 4 indicates Most or all of the time. Levels 1, 2, 3, and 4 were derived from the study participants’ self-assessments. Note: Questions 5, 9, 13, 17, and 19 were reverse-scoring questions, scored 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. The calculated total score was then multiplied by 1.25 to obtain the standard total score. In this study, a standard score of 50 was used as the threshold for detecting anxiety during early pregnancy. A total score of ≥ 50 was determined as the presence of anxiety symptoms.

Take-out food consumption

The consumption of take-out food was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire that included questions regarding the frequency and types of take-out food consumed. The frequency was determined using three questions: “Have you ordered take-out foods in early pregnancy?“, “Have you eaten any of the following types of takeaways during early pregnancy?“, and “How often do you order take-out foods?” The response to the first and second questions was either “yes” or “no”. The third question had the following options: <1 time/week, 1–4 times/week, and > 4 times/week [23].

The type of take-out food was determined by the question, “What kind of take-out food do you like?” Based on the common categories of major take-out platforms, take-out options were classified into 14 categories: Chinese fast food, rice noodles or noodles, fried chicken or hamburger, sugary drinks and desserts, buns or congee or pancakes, wontons or dumplings, pan fried or pot stickers, spicy hot pot, crayfish, kebabs, braised food, pizza or pasta, sushi or onigiri, salads and other nutritious meals [24].

Data collection

The participants scanned a QR code to complete the electronic questionnaire and submitted it immediately upon completion. Each participant could only submit the questionnaire once. Each participant was given some daily necessities as a reward for submitting, such as napkins, towels, soap, and hand sanitizer.

Participants’ responses were anonymous and confidential and declared at the beginning of the electronic questionnaire. Respondents were also informed that the data would be used for research purposes only. Each submitted questionnaire was reviewed and questionnaires with incomplete/missing items, incorrect completion and obvious logical errors were considered invalid.

Research variables

The research variables were as follows: age (years) (< 35 or ≥ 35), nationality (minority nationality or han nationality), education level (≤ senior high school or ≥ college), and work condition (unemployed or employed) of pregnant women and their spouses; stress at work (yes or no), parity (primipara or multipara); number of family inhabitants (≤ 2 or > 2); monthly per capita household income (RMB) (≤ 10000 or > 10000); vaginal bleeding (the blood discharge occurring in the vaginal area of the female reproductive system) (yes or no); vomiting (the passage of stomach contents through the oral cavity) (yes or no); unplanned pregnancy (yes or no); depression symptom (yes or no); anxiety symptom (yes or no); smoking (active and passive smoking) (yes or no), alcohol consumption (consuming beverages containing alcohol) (yes or no); online time (surfing the internet) (h/day) (≤ 8 or > 8).

Statistical analysis

The data were directly downloaded in Excel format from the backend of the questionnaire. Following data transformation and error checking, statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided). Continuous variables are presented as means ± SDs, while categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (n) with corresponding percentages (%). The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for univariate analysis. Multivariate ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed for statistically significant influencing factors in the univariate analysis.

Results

Basic characteristics

The basic characteristic variables are presented in Table 1. A total of 888 pregnant women were enrolled in this study. Of these, the mean age of pregnant women and their spouses were 29.0 ± 4.1 years and 31.0 ± 5.0 years, respectively. Overall, Pregnant women and their spouses demonstrated a high level of education, with 82.7% (n = 734) of women and 77.2% (n = 686) of spouses holding a college degree or higher. When it comes to childbirth experience, the majority of pregnant women (71.0%, n = 630) were first-time mothers. Concerning mental health, symptoms of depression were reported by 21.2% (n = 188) of participants, and 15.8% (n = 140) reported symptoms of anxiety. Furthermore, more than 8 h of daily online activity were observed in 31.8% (n = 282) of pregnant women.

Table 1.

Comparison of take-out food consumption frequency of first-trimester pregnant women with different characteristics [n (%)]

| Variables | Total | < 1 time/week | 1–4 times/week | > 4 times/week | H | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | ||||||

| < 35 | 805(90.8) | 565(70.1) | 179(22.3) | 61(7.6) | 0.010 | 0.919 |

| ≥ 35 | 82(9.2) | 57(69.5) | 19(23.2) | 6(7.3) | ||

| Education level* | ||||||

| Senior high school and under | 154(17.3) | 122(79.2) | 23(14.9) | 9(5.8) | 7.004 | 0.008 |

| College and above | 733(82.7) | 500(68.1) | 176(24.0) | 57(7.9) | ||

| Work condition* | ||||||

| Unemployed | 139(15.8) | 92(66.2) | 30(21.6) | 17(12.2) | 1.926 | 0.165 |

| Employed | 741(84.2) | 525(70.9) | 166(22.4) | 50(6.7) | ||

| Nationality* | ||||||

| Minority nationality | 59(6.7) | 37(61.7) | 15(25.0) | 7(13.3) | 1.985 | 0.159 |

| Han nationality | 827(93.3) | 585(70.7) | 182(22.0) | 60(7.3) | ||

| Spouse’s age (years) * | ||||||

| < 35 | 718(81.5) | 499(69.5) | 166(23.1) | 53(7.4) | 0.187 | 0.665 |

| ≥ 35 | 163(18.5) | 117(71.8) | 32(19.6) | 14(8.6) | ||

| Spouse’s education level* | ||||||

| Senior high school and under | 204(23.1) | 149(73.0) | 46(22.5) | 9(4.5) | 1.723 | 0.189 |

| College and above | 683(76.9) | 472(69.1) | 153(22.4) | 58(8.5) | ||

| Spouse’s Work condition | ||||||

| Unemployed | 115(13.0) | 74(64.3) | 32(27.8) | 9(7.9) | 1.759 | 0.185 |

| Employed | 773(87.0) | 548(71.0) | 167(21.6) | 58(7.4) | ||

| Spouse’s Nationality* | ||||||

| minority nationality | 47(5.3) | 28(59.6) | 14(29.8) | 5(10.6) | 2.561 | 0.110 |

| Han nationality | 833(94.7) | 588(70.6) | 183(22.0) | 62(7.4) | ||

| Number of permanent residents of households* | ||||||

| ≤ 2 | 381(43.0) | 254(66.8) | 90(23.6) | 37(9.6) | 4.337 | 0.037 |

| > 2 | 506(57.0) | 367(72.5) | 109(21.5) | 30(6.0) | ||

| Monthly per capita household income (RMB) | ||||||

| ≤ 10,000 | 560(63.1) | 405(72.3) | 110(19.6) | 45(8.1) | 2.701 | 0.100 |

| > 10,000 | 328(50.2) | 217(66.2) | 59(27.1) | 22(6.7) | ||

| Anxiety | ||||||

| No | 748(84.2) | 528(70.6) | 170(22.7) | 50(6.7) | 1.274 | 0.259 |

| Yes | 140(15.8) | 94(67.2) | 29(20.7) | 17(12.1) | ||

| Depression | ||||||

| No | 700(78.8) | 502(71.7) | 154(22.0) | 44(6.3) | 5.669 | 0.017 |

| Yes | 188(21.2) | 120(63.9) | 45(23.9) | 23(12.2) | ||

| Stress at work | ||||||

| No | 432(48.7) | 305(70.6) | 98(22.7) | 29(6.7) | 0.228 | 0.633 |

| Yes | 456(51.3) | 317(69.6) | 101(22.1) | 38(8.3) | ||

| Vaginal bleeding | ||||||

| No | 723(81.4) | 512(70.8) | 151(20.9) | 60(8.3) | 0.429 | 0.512 |

| Yes | 165(18.6) | 110(66.7) | 48(29.1) | 7(4.2) | ||

| Vomiting | ||||||

| No | 292(32.9) | 194(66.5) | 78(26.7) | 20(6.8) | 1.976 | 0.160 |

| Yes | 596(67.1) | 428(71.8) | 121(20.3) | 47(7.9) | ||

| Unplanned Pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 533(60.0) | 373(70.0) | 120(22.5) | 40(7.5) | 0.001 | 0.971 |

| Yes | 355(40.0) | 249(70.1) | 79(22.4) | 27(7.5) | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primipara | 626(70.5) | 424 (67.7) | 151(24.1) | 51(8.2) | 5.305 | 0.021 |

| Multipara | 262(29.5) | 201(75.6) | 44(18.3) | 13(6.1) | ||

| Smoking* | ||||||

| No | 590(66.5) | 411(69.7) | 134(22.7) | 45(7.6) | 0.166 | 0.684 |

| Yes | 297(33.5) | 211(71.0) | 64(21.5) | 22(7.4) | ||

| Alcohol Consumption* | ||||||

| No | 850(95.8) | 600(70.6) | 186(21.9) | 64(7.5) | 1.807 | 0.179 |

| Yes | 37(4.2) | 22(59.5) | 12(32.4) | 3(8.1) | ||

| Online time(h/day) * | ||||||

| ≤ 8 | 605(68.2) | 444(73.4) | 116(19.2) | 45(7.4) | 8.255 | 0.004 |

| > 8 | 282(31.8) | 178(63.1) | 82(29.1) | 22(7.8) | ||

*Total is not equal to 888 because it contains missing values.

Univariate analysis revealed significant differences in the frequency of food consumption during early pregnancy among groups with different characteristics of education level (H = 7.004, P = 0.008), number of permanent residents of households (H = 4.337, P = 0.037), depression symptoms (H = 5.669, P = 0.017), parity (H = 5.305, P = 0.021), and online time (H = 8.255, P = 0.004). The other variables did not exhibit a significant association with the frequency of take-out food consumption during early pregnancy, with a P value > 0.05 in univariate analysis (Table 1).

Consumption frequency of various take-out food

In this study, 73.3% of the 888 pregnant women reported consuming take-out during early pregnancy. The top three types of take-out foods were rice noodles or noodles (55.7%), Chinese fast foods (49.9%), and sugary drinks or desserts (37.4%). The least consumed foods were sushi or onigiri (15.8%), salads and other nutritious meals (11.9%), and pan-fried or pot stickers (11.8%). Approximately 19% of the pregnant women ordered rice noodles or noodles more than once a week. Overall, 70.2% (n = 623) of pregnant women consumed take-out food less than once a week during early pregnancy, 22.3% (n = 198) consumed it 1–4 times a week, and 7.5% (n = 67) consumed it more than 4 times a week. The consumption frequencies of various take-out foods are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of pregnant women with experience in consuming a specific take-out food during early pregnancy

Table 2.

Consumption frequency of various take-out food of first-trimester pregnant women in Changsha[n (%)]

| < 1 time/week | 1–4 times/week | > 4 times/week | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Take-out food | 623(70.2) | 198(22.3) | 67(7.5) |

| Chinese fast food | 715(80.5) | 135(15.2) | 38(4.3) |

| Rice noodles or Noodles | 713(80.3) | 148(16.7) | 27(3.0) |

| Fried chicken or Hamburger | 843(94.9) | 42(4.8) | 3(0.3) |

| Sugary drinks or Desserts | 788(91.1) | 76(8.5) | 4(0.4) |

| Buns or Congee or Pancakes | 765(86.2) | 97(10.9) | 26(2.9) |

| Wontons or Dumplings | 814(91.7) | 68(7.6) | 6(0.6) |

| Pan Fried or Pot Stickers | 868(97.8) | 18(2.0) | 2(0.2) |

| Spicy hot pot | 842(94.8) | 43(4.9) | 3(0.3) |

| Crayfish | 870(98.0) | 18(2.0) | 0 |

| Kebabs | 864(97.3) | 24(2.7) | 0 |

| Braised food | 871(98.0) | 17(2.0) | 0 |

| Pizza or Pasta | 868(97.7) | 20(2.3) | 0 |

| Sushi or onigiri | 873(98.3) | 15(1.7) | 0 |

| Salads and other nutritious meals | 874(98.5) | 13(1.4) | 1(0.1) |

Analysis of factors influencing the frequency of take-out food consumption

The frequency of take-out food consumption was treated as the dependent variable. Subsequently, the influencing factors exhibiting statistically significant differences in the aforementioned univariate analysis (education level: 0 = senior high school and under, 1 = college and above; number of permanent residents of households: 0 = ≤ 4, 1 = > 4; depression symptoms: 0 = no, 1 = yes; parity: 0 = primipara, 1 = multipara; Online time: 0 = ≤ 8, 1 = > 8) were considered as independent variables. An ordinal logistic regression model was employed for the multivariate analysis to elucidate the specific impact of each variable on the dependent variable. The results of this analysis, including the coefficients and their significance, are presented in detail in Table 3, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the relationships among the variables.

Table 3.

Ordinal logistic regression analysis of factors influencing take-out food consumption frequency among first-trimester pregnant women

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P | OR(95%CI) | P | |

| Education level | ||||

| Senior high school and under | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00(Reference) | ||

| College and above | 1.75(1.16, 2.67) | 0.008 | 1.88(1.23, 2.88) | 0.003 |

| Depression | ||||

| No | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00(Reference) | ||

| Yes | 1.51(1.08, 2.10) | 0.016 | 1.65(1.18, 2.32) | 0.004 |

| Online time(h/day) | ||||

| < 8 | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00(Reference) | ||

| ≥ 8 | 1.54(1.14, 2.07) | 0.005 | 1.50(1.11, 2.03) | 0.008 |

| Number of permanent residents of households | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00(Reference) | ||

| > 2 | 0.74(0.56, 0.98) | 0.037 | 0.79(0.57, 1.09) | 0.145 |

| Parity | ||||

| Primipara | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00(Reference) | ||

| Multipara | 0.68(0.49, 0.95) | 0.021 | 0.81(0.56, 1.17) | 0.252 |

Examining the coefficients in the ordinal logistic regression model revealed a statistically significant result (χ² = 28.961, P < 0.001), confirming the overall significance of the model. The results of the multivariate ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that pregnant women with depression symptoms (odds ratio [OR] = 1.65, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18–2.32) and those with a higher education level (OR = 1.88, 95%CI: 1.23–2.88) had an increased frequency of take-out food consumption in early pregnancy, compared to those without depression symptoms and with a lower education level. Additionally, pregnant women (OR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.11–2.03) who spend more than 8 h daily online were more likely to engage in take-out food consumption behaviours than those who spend no more than 8 h daily online. The number of permanent residents of households and parity were statistically significant in the univariate analysis but not in the multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

This study is the first to describe the current status of take-out food consumption among first-trimester pregnant women and explore its influencing factors. Our findings indicate that take-out food is highly popular among pregnant women, with a predominant preference for rice noodles or noodles. Ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that three factors—educational level, depression symptoms, and time spent online—were correlated with the consumption of take-out food by pregnant women.

Our results showed that 73.3% of women in early pregnancy ordered take-out food. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey revealed that over 90% of women of childbearing age consumed take-out food during pregnancy [29]. Among the surveyed pregnant women, 29.8% consumed take-out food at least once a week, which is lower than the 61.5% reported in a cross-sectional study on university students in China [21]. Possible reasons for this variation include differences in the research participants, sample sizes, and nutritional disparities between university students and pregnant women.

Our study revealed that pregnant women with higher educational levels tended to consume take-out food more frequently than those with lower educational levels. This aligns with the findings of previous cross-sectional studies in Australia, which suggested that adults aged 25–64 years with lower educational levels were less likely to consume take-out food than those with higher educational levels [10]. In a cross-sectional study of a Korean-American population, a higher level of education was associated with more frequent use of take-out food [30]. Although other studies have indicated that women with higher educational levels prefer spending more time cooking at home [31], our findings contradict this trend among pregnant women. This may be associated with the fact that pregnant women with higher educational levels might be busier with work or other activities, making them more inclined to use take-out services to save time and energy.

Additionally, our study indicates that depression is linked to an increased frequency of take-out food consumption among pregnant women. Similarly, a cohort study suggested that women experiencing depression during pregnancy had a higher intake of unhealthy take-out foods throughout the perinatal period [32]. Another cross-sectional study found that women with depression were at a higher risk of poor dietary quality than those without depression [33]. This association may be attributed to depression-induced changes in appetite and preferences for specific foods, with take-out options often providing a broader range of choices to accommodate different tastes and appetites.

Notably, our study results revealed that pregnant women who spent more than 8 h daily online were more likely to engage in take-out food consumption behaviours than those who spent no more than 8 h daily online. Some studies have shown that pregnant women use the internet to retrieve health information and nutrition during pregnancy [34–36], contributing to an increased prevalence of take-out food consumption behaviour among pregnant women.

Our study results indicate that high-frequency consumption of takeaway foods during pregnancy is associated with depressive symptoms, educational level, and time spent online. Future interventions could focus on raising awareness of the potential risks of excessive consumption of takeaway foods and providing practical strategies for preparing healthy meals at home. Additionally, digital platforms could be leveraged to deliver tailored nutritional education and support, particularly for women who spend substantial amounts of time online.

The present study has two primary strengths. Firstly, it stands out for its novelty, as there are no existing studies on pregnant women’s take-out food consumption in early pregnancy. Secondly, the inclusion of numerous influential factors related to pregnant women enabled a comprehensive understanding of the current situation of take-out food consumption during this period. This approach allowed for the identification of influential factors affecting pregnant women’s take-out food consumption. Targeted initiatives can be developed to address the specific needs identified in this study.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, utilising one-on-one online questionnaires completed by pregnant women, particularly retrospective questionnaires that are prone to recall bias, may introduce information bias. Secondly, the study population was derived from a single hospital, resulting in selection bias and limited representation of the broader pregnant population. Further research with larger sample sizes from diverse hospitals and regions is warranted to provide more robust evidence on the impact of take-out food consumption during early pregnancy. Future investigations could incorporate more objective measures of dietary intake and consider additional factors influencing food choices, such as cultural preferences and socioeconomic factors.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that take-out food consumption is common among first-trimester pregnant women in Changsha. Furthermore, depression, educational level, and time spent online were associated with the consumption of food by pregnant women. Additionally, our findings emphasise the need for targeted interventions to promote the health of both pregnant women and their infants by reducing the behaviour of ordering take-outs during pregnancy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Science Foundation of Hunan Province, the National Science Foundation of Hunan Provincial Health Commission and the open project of Hunan Normal University School of Medicine. The authors also thank the participants in the study cohort and the staffs at the Changsha Hospital for Maternal & Child Health Care Affiliated to Hunan Normal University.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Author contributions

Sheng Teng, Yi Yang, Leshi Lin, Wenjuan Li, Li Li, Fang Peng, Xiao Gao, and Dongmei Peng participated in the study design. Sheng Teng and Yi Yangconducted the field study, collated the data, performed statistical analyses, and contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. Leshi Lin andWenjuan Li coordinated all research activities and edited the manuscript. Li Li, Fang Peng, Xiao Gao, and Dongmei Peng played key roles in the fieldsurvey. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ40367), the National Science Foundation of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (202212055647), the open project of Hunan Normal University School of Medicine (KF2021016).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (approval number: 2021 No. 278). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sheng Teng and Yi Yang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiao Gao, Email: 18670321975@163.com.

Dongmei Peng, Email: 444061246@qq.com.

References

- 1.Smith KJ, McNaughton SA, Gall SL, Blizzard L, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Takeaway food consumption and its associations with diet quality and abdominal obesity: a cross-sectional study of young adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgoine T, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, Brage S, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Does neighborhood fast-food outlet exposure amplify inequalities in diet and obesity? A cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1540–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ahluwalia N, Ogden CL. Fast food intake among children and adolescents in the united States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;375:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen HG, Davies IG, Richardson LD, Stevenson L. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: a narrative review. Nutr Res Rev. 2018;31:16–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Hou F, Yang S, Li J, Zha X, Shen G. Beyond emotion: online takeaway food consumption is associated with emotional overeating among Chinese college students. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27:781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du F, Cai H, Zhang Q, Chen Q, Shi H. Microplastics in take-out food containers. J Hazard Mater. 2020;399:122969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zha H, Lv J, Lou Y, Wo W, Xia J, Li S, et al. Alterations of gut and oral microbiota in the individuals consuming take-away food in disposable plastic containers. J Hazard Mater. 2023;441:129903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai CL, Liu LY, Guo JL, Zeng LX, Guo Y. Microplastics in take-out food: are we over taking it? Environ Res. 2022;215:114390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han Y, Cheng J, An D, He Y, Tang Z. Occurrence, potential release and health risks of heavy metals in popular take-out food containers from China. Environ Res. 2022;206:112265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu JL, Duan Y, Zhong HN, Lin QB, Zhang T, Zhao CC, et al. Analysis of microplastics released from plastic take-out food containers based on thermal properties and morphology study. Food Addit Contam Part Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2023;40:305–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miura K, Giskes K, Turrell G. Socioeconomic differences in takeaway food consumption and their contribution to inequalities in dietary intakes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:820–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orloff NC, Flammer A, Hartnett J, Liquorman S, Samelson R, Hormes JM. Food cravings in pregnancy: preliminary evidence for a role in excess gestational weight gain. Appetite. 2016;105:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Wang L, Xue H, Wang H, Wang Y. Fast food consumption and its associations with obesity and hypertension among children: results from the baseline data of the childhood obesity study in China Mega-cities. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KJ, Blizzard L, McNaughton SA, Gall SL, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Takeaway food consumption and cardio-metabolic risk factors in young adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Wang L, Xue H, Qu W. A review of the growth of the fast food industry in China and its potential impact on obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A, Belski R, Radcliffe J, Newton M. What do pregnant women know about the healthy eating guidelines for pregnancy? A web-based questionnaire. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:2179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaghef-Mehrabani E, Wang Y, Zinman J, Beharaj G, van de Wouw M, Lebel C, et al. Dietary changes among pregnant individuals compared to pre-pandemic: A cross-sectional analysis of the pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic (PdP) study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:997236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Huo Y, Zhang J, Xu D, Bai F, Gui Y. Association between high-fat diet during pregnancy and heart weight of the offspring: A multivariate and mediation analysis. Nutrients. 2022;14:4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamada H, Ebara T, Matsuki T, Kato S, Sato H, Ito Y, et al. Impact of ready-meal consumption during pregnancy on birth outcomes: the Japan environment and children’s study. Nutrients. 2022;14:895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Min JY, Kim HJ, Min KB. Association between the frequency of eating non-home-prepared meals and women infertility in the united States. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Q, Sun Q, Yang L, Cui Y, Du J, Liu H. High nutrition literacy linked with low frequency of take-out food consumption in Chinese college students. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, Wang J, Wu S, Li N, Wang Y, Liu J, et al. Association between take-out food consumption and obesity among Chinese university students: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su F, Lin Y, Chen Q, Xu J, Mao C, Wang Y, et al. Correlation analysis of takeaway food consumption and sleep disturbance among college students in Jiangxi Province. Chin J Sch Health. 2021;42:1530–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Xiong J, Wang J, Li W, Yang Y, Ren G. The current situation of college students’ take - out food consumption and its correlation with overweight and obesity in Changsha City. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2020;24:1027–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrozzi A, Gagliardi L. Anxious and depressive components of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in maternal postpartum psychological problems. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, Leung TY, Chan KP, Chau IO, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:433–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira TA, Luzetti GGCM, Rosalém MMA, Mariani Neto C. Screening of perinatal depression using the Edinburgh postpartum depression scale. Rastreamento Da depressão perinatal Através Da Escala de depressão pós-parto de Edinburgh. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2022;44:452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samakouri M, Bouhos G, Kadoglou M, Giantzelidou A, Tsolaki K, Livaditis M. [Standardization of the Greek version of Zung’s Self-Rating anxiety scale (SAS)]. Psychiatriki. 2012;23:212–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fasola O, Abosede O, Fasola FA. Knowledge, attitude and practice of good nutrition among women of childbearing age in Somolu local government, Lagos state. J Public Health Afr. 2018;9:793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SK. Acculturation, meal frequency, eating-out, and body weight in Korean Americans. Nutr Res Pract. 2008;2:269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams J, White M. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of time spent cooking by adults in the 2005 UK time use survey. Cross-sectional analysis. Appetite. 2015;92:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galbally M, Watson SJ, Boyce P, Anglin R, McKinnon E, Lewis AJ. Maternal diet, depression and antidepressant treatment in pregnancy and across the first 12 months postpartum in the MPEWS pregnancy cohort study: perinatal diet, depression and antidepressant use. J Affect Disord. 2021;288:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avalos LA, Caan B, Nance N, Zhu Y, Li DK, Quesenberry C, et al. Prenatal depression and diet quality during pregnancy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120:972–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs EJA, van Steijn ME, van Pampus MG. Internet usage of women attempting pregnancy and pregnant women in the Netherlands. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2019;21:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao LL, Larsson M, Luo SY. Internet use by Chinese women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery. 2013;29:730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmadian L, Khajouei R, Kamali S, Mirzaee M. Use of the internet by pregnant women to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth. Inf Health Soc Care. 2020;45:385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.