Abstract

Purpose

United States (US) immigrant populations face unique barriers to accessing health care, including reproductive health care. Abortion access and experiences among immigrant populations in the US are not well understood.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review to synthesize existing literature about US immigrant populations’ access to and use of abortion services. Eight studies met the eligibility criteria, which included being published in English and presenting at least one finding relevant to US immigrant populations’ access to or experience utilizing abortion; key findings were identified using content analysis.

Results

We present results organized within three main categories: (1) overall rates of abortion among immigrant versus US-born individuals, (2) characteristics of US immigrants who receive abortion services, and (3) barriers to abortion access for US immigrant populations, which included concepts pertaining to discrimination, challenges navigating the healthcare systems, and lack of knowledge about legal rights.

Conclusion

Study findings illustrate three categories of results relevant to immigrant experiences accessing abortion care in the US, including revealing barriers to abortion services rooted in lack of knowledge of US institutional systems and mistreatment in clinical and legal settings due to race or immigration status. Further research is needed to better understand nuances in experiences among immigrant subpopulations, experiences of US immigrants who speak a language other than English or Spanish, and use of self-managed abortions or abortions in informal settings among US immigrants.

Keywords: Immigrant, Abortion, Reproductive health, Health care access

1. Introduction

In 2021, the American Community Survey estimated that there were 45,270,103 immigrants, considered in this paper to include all foreign-born individuals living in the United States (US); this comprised 13.6 % of all residents. (U.S. Census Bureau 2021) Experiences in the US, including experiences related to health care services eligibility, access, and utilization, differ among immigrant populations. (Derose et al., 2007) However, immigrants share a generally universal experience of unmet needs for health services including reproductive health services, as well as reduced utilization compared with non‐immigrants. (Tapales et al., 2018) Furthermore, under‐enrollment in programs for which immigrant groups may be eligible has been shown to be related to fear of possible punitive actions both regarding use of reproductive health services (Hasstedt, 2013) as well as general health care. (Romero et al., 2018) The expansion of the definition of ‘public charge’ in 2019 as a reason to deny green card or other visa applications adds credence to these concerns. (Luthi, 2020)

In 2020, 11.2 abortions were performed and reported per 1000 women aged 15‐44. (Kortsmit et al., 2022) However, access to abortion services varies widely by geography and travel time because abortion care in the US is subject to national legal precedent and local policy, especially in comparison to other health care services. In 1973, the Supreme Court ruling in Roe v. Wade stipulated a constitutional right to abortion. In the nearly 50 years since that decision, state-level differences in abortion access prevailed and are likely due to a wide range of factors, including number of health care professionals providing abortion services, clinical appointment wait times, travel distance to providers, availability of telemedicine, cost, insurance coverage, state‐specific legislation, and abortion methods available according to gestational age. (O'Donnell et al., 2018; Gonzalez et al., 2020) The June 2022 Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization upended the prior national precedent and enabled more restrictive state-level laws that have widened geographic disparities in access. (Rader et al., 2022; Dobbs 2022; Harvey et al., 2023) Access to abortion care by state presents a rapidly changing landscape; in 2023 alone, seven states passed new legislation to secure the right to abortion. (Forouzan and Guarnieri, 2023) As of April 2024, abortion was entirely banned in 14 states, and gestational age limits restricting to under 22 weeks exist in an additional 11 states. (Kaiser Family Foundation 2024)

The geopolitical intersection between immigration and abortion policy makes this a particularly salient issue. Given comparatively more limited access to health care services in general, (Derose et al., 2007) immigrant populations may face unique barriers to accessing abortion care. Further, policy in the US has shifted to be more hostile towards both abortion and immigration in recent years. In the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, states with the most restrictive abortion access are likely to be politically conservative and thus may also present a hostile environment for immigrant women, compounding challenges in accessing care. An Immigration Policy Climate index measuring state-level xenophobia found some evidence for this, identifying states with the largest shift towards being more exclusive of immigrants from 2009 to 2019 (e.g., Alabama, Wisconsin); (Samari et al., 2021) these states currently have abortion bans or laws severely restricting access.

States with the largest percentage of immigrant populations, including California, New Jersey, and New York, are largely states with protected access to abortion care. (Hahn and Medina, 2024) A notable exception to this is Florida, where 21.1 % of the population is foreign-born and where legislation banning abortion care after six weeks gestation went into effect on May 1, 2024, and Texas, which is experiencing a large increase in foreign-born residents and has a strict abortion ban in place. (Kaiser Family Foundation 2024; Hahn and Medina, 2024)

To date, there are no systematic reviews that organize and synthesize the existing literature about US immigrant populations’ access to and usage of abortion care services. There is a scarcity of published work assessing the prevalence of abortion procedures among US immigrant populations, as well as those identifying experiences and barriers in seeking abortion care. This systematic review seeks to synthesize and integrate existing research findings to illustrate what is known and, importantly, what gaps in knowledge exist in understanding abortion access among immigrant populations. In this review, immigrant is defined as all foreign-born individuals living in the US, including documented and undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers. This review seeks to highlight salient experiences in seeking and obtaining abortion care that may be unique to immigrant populations, and to identify gaps in research or inconsistent findings that require further attention. Importantly, increasing our understanding of the compounding challenges of accessing abortion care as an immigrant in the US can help to guide policy and programmatic efforts to increase access to the full spectrum of reproductive care for this population.

2. Materials and methods

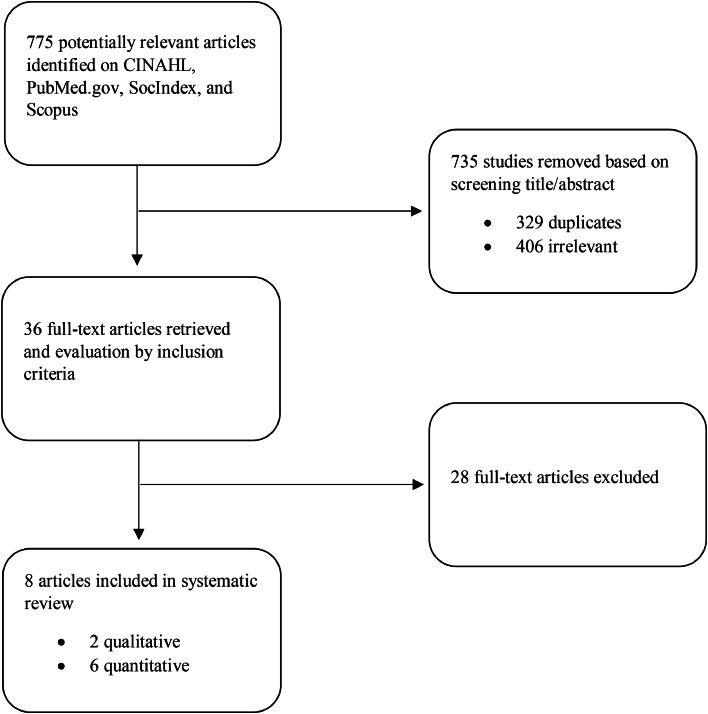

The review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance. (Moher et al., 2009) The following bibliographic databases were searched: CINAHL, PubMed.gov, SocIndex, and Scopus using combinations of the following terms: ((migrant* OR refugee* OR immigrant* OR immigration OR “asylum seeker*” OR asylee OR “undocumented person” OR “documented person” OR “unauthorized immigrant” OR “naturalized citizen” OR “illegal alien” OR “nonnative person” OR “foreigner” OR “foreign national” OR “nativity” OR “foreign born”) AND (abortion* OR termination* OR feticide* OR “medical abortion*” OR “self-managed abortion” OR “self-induced abortion” OR “medicalized abortion” OR “pill abortion” OR “misopristine” OR “misoprostol” OR “surgical abortion” OR abort* OR “end pregnancy” OR aborticide* OR misbirth*) AND (United States)). The search was not restricted to title, key word, abstract, or MESH term but inclusive for all fields containing any of the listed terms for all databases. The searches were conducted on December 3 and December 6, 2021, covering the period from January 1, 2010, to the search date. A subsequent literature scan was conducted on September 15, 2022, to ensure no new literature had been published relevant to this topic in the time since the initial search. As such, all included literature was published prior to the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization issued on June 24, 2022 and reflect the national landscape of abortion access before the ruling led to increased restrictions to legal abortion care in some states (Dobbs, 2022).

Findings from the searches were imported into Covidence software. After duplicates were removed, a masked, double title and/or abstract review was conducted to determine eligibility for inclusion; with discrepancies reconciled by a third reviewer. If eligibility could not be determined by abstract review, full articles were reviewed (with double masking). Papers were considered eligible if they were published in English, presented at least one finding relevant to US immigrant populations’ access to or experience utilizing abortion, and, for quantitative studies, included a comparison group by immigration status. Notably, papers including being foreign-born as a confounding variable that did not present any findings specifically relevant to place of birth were excluded. The reference lists of eligible articles were also reviewed for additional eligible articles. Search results and article inclusion are documented with a PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Systematic literature search for published articles on abortion and U.S. immigrant populations.

Among included papers, an Excel spreadsheet was populated to extract study type, study design and methods, research question(s), study population, exposure(s), outcome(s), confounding variables, relevant results, and limitations and biases. Relevant results were then analyzed using content analysis methodology to determine key categories of findings that emerged in and across the included articles. The categories were determined based on the results of the papers rather than a priori. Although theoretically one paper could address multiple categories of findings, no paper included relevant results that pertained to more than one identified category.

All included papers were critically appraised; cohort and cross-sectional studies were critically appraised using the appropriate Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, (Peterson et al., 2011; Modesti et al., 2016) and qualitative studies using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR). (O'Brien et al., 2014) All critical appraisals were independently conducted by two researchers and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data were extracted independently by two researchers and a content analysis was used to summarize existing research and identify gaps.

3. Results

3.1. Included studies

A total of eight papers were identified for inclusion: six quantitative and two qualitative studies (Table 1). The critical appraisal varied for papers included in the review (Table 2), but all eight papers were included due to the dearth of published articles relevant to abortion access among US immigrant populations.

Table 1.

Summary of included papers.

| Paper reference | Study aims | Study type | Data analysis | Sample population | Languages of data collection | Relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aztlan et al., (2018) | To explore demographic factors (including foreign- or native-born) associated with risk unintended subsequent pregnancy within 5 years among women who had a previous unintended pregnancy and wanted an abortion | Quantitative | Secondary analysis of 5-year prospective cohort study | 798 women who sought abortion at one of 30 abortion facilities across the United States between 2008 and 2010 | English and Spanish | Neither receiving nor being denied a wanted abortion is associated with risk of subsequent unintended pregnancy (rate of unintended pregnancy at 5 years was 42 per 100 women). Foreign-born women had a lower rate of subsequent unintended pregnancy compared to native-born women (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.54; 95 % CI: 0.25–0.77). |

| Deeb-Sossa and Billings (2014) | To document struggles faced by Mexican immigrant women and teens making decisions about abortion and seeking abortion services in North Carolina related to intersectional forms of oppression | Qualitative | Ethnographic data and interviews with key stakeholders | 12 key informants, observations of unspecified number of Mexican immigrant women and teens living in North Carolina during 6 month ethnographic study period | English and Spanish | Mexican immigrant women and teens face restrictions to abortion access by legal and medical institutions. As a result, these women may receive abortion services outside of the formal healthcare system, through curanderas/os (folk healers). |

| Dennis et al. (2015) | To document the experiences of low-income women receiving abortion care in Massachusetts | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 27 women who obtained abortions in Massachusetts after January 2009, lived in MA at that time, were uninsured or on a public insurance plan, and met the criteria for enrolling in a Massachusetts public insurance plan (<=300 % of Federal Poverty Level) | Not specified (presumed English) | Most of the low-income women in the study had access to abortion care that they felt was timely, conviently located, and affordable. However, the two immigrant women in the study were the only participants who reported challenges in setting up the abortion appointment due to challenges navigating the healthcare system. |

| Desai et al. (2019) | To describe differences in demographic and circumstantial characteristics between US-born and foreign-born women receiving abortion care in US | Quantitative | Pooled cross-sectional surveys | 17,873 individuals who obtained abortions from 2008 to 2009 and 2013–2014; national survey sample | English and Spanish | Immigrants who received an abortion in the U.S. were more likely than native born U.S. women to be older (40 % were age 30 and above compared to 23 % of nonimmigrants, p-value <0.001), to be unmarried (88 % compared to 70 %, p-value <0.001), to have had a prior birth (67 % compared to 59 %, p-value <0.001), to be living below the Federal Poverty Level (50 % compared to 45 %, p-value <0.01), to lack health insurance coverage (45 % compared to 32 %, p-value <0.001), to have experiences 2 or more disruptive life events (25 % compared to 15 %, p-value <0.001), and to have traveled a long distance to the facility, with 16 % traveling over 50 miles compared to 9 % of nonimmigrants (p-value <0.001), and less likely to have the abortion after 12 weeks gestation (8 % compared to 11 %, p-value <0.001). |

| Desai et al. (2021) | To calculate abortion rates among NYC residents’ race/ethnicity, and among Asian NYC residents by country of origin and nativity in 2014–2015, and to calculate percent change in these rates from 2011 to 2015 | Quantitative | Cross-sectional analysis of surveillance data | All recorded abortions among NYC residents in 2014–2015 (n = 3881,904); sub-analyses focused on Asian populations (n = 590,099) | N/A (surveillance data) | Abortion rates on average among Asian women in NYC in 2014–2015 was 12.6 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44 years, lower than the rates for other major racial/ethnic groups during the same time period. Differences in abortion rare exist among Asian subgroups by country of origin; Asian residents of Indian origin had the highest abortion rate (30.5 abortions per 1000 women), followed by Japanese women (17.0), Vietnamese women (13.0), Chinese women (8.8), and Korean women (5.1). The age-standardized abortion rate was higher among U.S.-born Asian New Yorkers (15.7 per 1000 women) compared to foreign-born Asian New Yorkers (10.6 per 1000 women), although the differential varied by country of origin. |

| Lara et al. (2015) | To explore demographic factors associated with knowledge about abortion laws and access | Quantitative | Cross-sectional survey | 1262 women attending primary care or full-scope Ob/Gyn clinics serving low-income populations in San Francisco, Boston, and New York who were 15–45 years old and spoke English or Spanish; convenience sample | English and Spanish | First-generation immigrant women and women who identified their primary language as Spanish speakers were significantly less likely than second-generation or higher and women whose primary language is English speakers to demonstrate correct knowledge of state abortion laws and access. |

| Ralph et al. (2020) | To estimate the prevalence of self-managed abortion experience among women of reproductive age in the U.S. and to identify demographic characteristics associated with self-managed abortion experience | Quantitative | Cross-sectional survey | 7022 members of the GfK web-based KnowledgePanel who self-identified as female, were age 18–49, and speak English or Spanish | English and Spanish | 1.4 % of respondents had ever attempted a self-managed abortion. In unadjusted models, women born outside of the U.S. were more likely to have ever attempted self-managed abortion compared to those born in the U.S. (PR: 2.12; 95 % CI: 1.07–4.20). |

| Toprani (2015) | To identify patient characteristics associated with repeat abortions | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study using surveillance data | 76,614 abortions performed in NYC on NYC residents reported to Vital Statistics in 2010 | N/A (surveillance data) | The majority of abortion patients are at risk of repeat unintended pregnancy and abortion (58 % of abortion patients in 2010 in NYC were having a repeat procedure). Patients born outside of the US were less likely to have had past abortions (56 %) than patients born in the US (61 %). In adjusted model, a lower mean number of previous abortion was found among foreign-born than US-born patients (adjusted ratio of mean = 0.78; 95 % CI 0.77, 0.80). |

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of included studies.

|

Study populations varied widely. One qualitative study focused specifically on the experiences of Mexican immigrant women and teens living in North Carolina, conducted in Spanish and English, (Deeb-Sossa and Billings, 2014) while the other detailed experiences of English-speaking low-income women who obtained abortions in Massachusetts, including two immigrant women. (Dennis et al., 2015) Among the six quantitative papers, two studies used New York City (NYC) surveillance data to conduct their analyses, including all abortions that occurred in NYC in 2014–2015 with sub-analyses of Asian populations, (Desai et al., 2021) and all abortions that occurred in NYC in 2010 considering the subpopulation of foreign-born patients. (Toprani, 2015) The four other quantitative studies conducted data collection in English and Spanish. One of these studies included 798 women who sought abortion care at one of 30 US abortion facilities between 2008 and 2010, (Aztlan et al., 2018) another included a national survey sample of 17,873 individuals who obtained abortions from 2008 to 2009 and 2013 to 2014, (Desai et al., 2019) another surveyed a convenience sample of 1262 low-income women who spoke English or Spanish and were attending primary care or obstetrics and gynecology clinics located in San Francisco, Boston, or New York, (Lara et al., 2015), and another included 7022 respondents of a web-based survey who self-identified as female, were age 18–49, and spoke English or Spanish. (Ralph et al., 2020)

3.2. Key categories of findings

The content analysis resulted in three categories: (1) overall rates of abortion among immigrant versus US born individuals, (2) characteristics of US immigrants who receive abortion services, and (3) barriers to abortion access for US immigrant populations, which included concepts about mistreatment, challenges navigating the healthcare systems, and lack of knowledge about legal rights (Table 3).

Table 3.

Categories of findings identified through narrative synthesis.

| Categories (Number of the eight included papers presenting relevant findings) |

|---|

| Rates of Abortion among Immigrant versus U.S. Born Individuals (4) |

| Characteristics of U.S. Immigrants Who Receive Abortion Services (1) |

| Barriers to Abortion Access for U.S. Immigrant Populations (3) |

| Mistreatment (1) |

| Challenges Navigating the Healthcare System (1) |

| Lack of Knowledge About Legal Rights (1) |

3.2.1. Rates of abortion among foreign-born versus US-born individuals

Four papers compared abortion rates among immigrant versus US-born populations. Immigrant persons consistently demonstrated lower rates of abortion services relative to persons born in the United States. Aztlan et al. (2018) found that among women who sought abortion services, foreign-born women had a lower rate of subsequent unintended pregnancy compared to US-born women (adjusted hazard ratio 0.54; 95 % CI: 0.25–0.77). Aztlan et al., (2018) and Toprani (2015) found that among patients who lived in and received an abortion in New York City in 2010, 58 % were experiencing a repeat abortion rather than a first-time abortion. (Toprani, 2015) However, only 56 % of foreign-born patients receiving an abortion were having a repeat procedure, compared to 61 % among US-born patients. In an analysis of 2014–2015 abortion rates in New York City by race/ethnicity with particular focus on rates among Asian New Yorkers, the age-standardized abortion rate was higher among US-born Asian New Yorkers (15.7 per 1000 women) compared to foreign-born Asian New Yorkers (10.6 per 1000 women). (Desai et al., 2021) The same trend held when considering age-standardized abortion rates among US-born versus foreign-born Asian New Yorkers by country of origin including India (US-born: 35.9 per 1000; foreign-born: 26.8 per 1000), China (US-born: 12.1 per 1000; foreign-born: 7.0 per 1000), Japan (US-born: 38.9 per 1000; foreign-born: 8.4 per 1000), Korea (US-born: 8.9 per 1000; foreign-born: 2.3 per 1000), and Vietnam (US-born: 14.9 per 1000; foreign-born: 8.9 per 1000).

In an exception to this trend, respondents born outside of the US were more likely to have ever attempted a self-managed abortion relative to US-born persons in a study conducted by Ralph et al. (2020) (prevalence ratio: 2.12; 95 % CI: 1.07–4.20). (Ralph et al., 2020) However, this study did not differentiate between those who had attempted a self-managed abortion prior to their arrival in the US from those who had attempted the self-managed abortion after immigrating.

3.2.2. Characteristics of US immigrants who receive abortion services

Only one study included in this review examined the characteristics of foreign-born women who receive abortions in the US compared to US-born women in a pooled and weighted sample of 17,873 persons who had abortions and participated in the 2008 and 2014 Abortion Patient Surveys. (Desai et al., 2019) Among immigrants who had received abortions in the study population, 44 % had been in the US for less than 10 years. Forty-nine percent identified as Hispanic, 20 % as Asian, 15 % as non-Hispanic Black, and 10 % as non-Hispanic White. Twenty-four percent completed the survey in Spanish, 76 % in English; the survey was not offered in languages besides English and Spanish so immigrants who could not participate in either language are likely excluded from the sample population.

Immigrants who received an abortion in the US were more likely than US-born women to be older (40 % were age 30 and above compared with 23 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.001), and to be unmarried (88 % of immigrants and 70 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.001). Immigrants receiving abortion services were more likely than nonimmigrants to have had a prior birth (67 % of immigrants and 59 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.001), and less likely to have the abortion after 12 weeks gestation (8 % of immigrants and 10 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.001). Immigrants who obtained abortions were more likely to be living below the Federal Poverty Level (50 % of immigrants compared to 45 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.01).

With respect to potential barriers or challenges in accessing care, immigrants were more likely than US-born women to lack health insurance coverage (45 % of immigrants and 32 % of nonimmigrants, p < 0.001), and to have experienced two or more disruptive life events (25 % compared to 15 %, p < 0.001). Immigrants were also more likely to have traveled a long distance to the facility, with 16 % traveling over 50 miles compared to 9 % of nonimmigrants (p < 0.001).

3.2.3. Barriers to abortion access for U.S. immigrant populations

Three papers included in this review identified barriers to abortion access among immigrant groups. However, each paper identified a different primary barrier. Each barrier is presented and described below.

Institutional mistreatment by healthcare and legal systems. Ethnographic and qualitative research by Deeb-Sossa and Billings (2014) described mistreatment by medical and legal staff as a barrier faced by Mexican immigrant women and teens in North Carolina in accessing abortion services. (Deeb-Sossa and Billings, 2014) This mistreatment was encountered during legal gateways (i.e., excessive personal questioning by a judge for a teen seeking a judicial bypass), and disrespectful treatment by healthcare providers. A midwife interviewed in this study highlighted that some providers will not perform abortions or provide patients with referrals for abortion services, in some cases referring patients seeking abortion services to a crisis pregnancy center whose aim is to spread misinformation and shame related to abortion. (Rosen, 2012) As a result of these experiences, some study participants expressed interest in obtaining care outside of traditional American medical systems including using curandero/as (folk healers).

Challenges navigating the healthcare system. In in-depth interviews (n = 27) conducted by Dennis et al. (2015) with low-income urban women, most study participants reporting having access to abortion services that were affordable, timely, and easy to travel to. (Dennis et al., 2015) However, the two immigrant women included in the study population were the only participants to report challenges in navigating the healthcare system, specifically related to challenges in setting up an appointment for abortion care.

Lack of knowledge about legal rights.Lara et al. (2015) considered a convenience sample of 1,262 women attending clinics serving low-income populations. They found that first-generation immigrant women and women who identified their primary language as Spanish were significantly less likely than second-generation or higher and women whose primary language is English to demonstrate correct knowledge of state abortion laws and access. (Lara et al., 2015)

3.3. Quality of research

The quality of research presented in the eight included studies varied (Table 2). Half of included studies met every criterion in their respective quality assessment tool. Among the quantitative research studies, only Toprani (2015) presented findings from an appropriate comparison group. Results presented in Aztlan et al., (2018), Lara et al. (2015), and Ralph et al. (2020) may suffer from selection bias due to non-representative study samples. Among qualitative research studies, Dennis et al. (2015) followed rigorous standards outlined in the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) tool, but Deeb-Sossa and Billings (2014) met only seven of the 19 outlined criteria.

4. Discussion

This systematic review considers eight published papers related to US immigrant populations and abortion services and identifies important information about rates of abortion among immigrant populations in the US, some demographic information about US immigrants who receive abortion services, and important institutional, systemic, and personal barriers to accessing abortion care among immigrant populations in the US. Research consistently finds that US-born women obtain abortions at higher rates than foreign-born women. Among those who do receive abortion care in the US, immigrants are more likely to be older, to be unmarried, to be living in poverty, and to have had a prior birth. Three studies identified barriers to obtaining abortion care, but each study highlighted a different primary barrier, underscoring a lack of consistency across studies addressing this research topic.

National and local political contexts likely play an important role in abortion access and experiences among immigrant populations, especially given the compounding consequences of hostile immigration policies in many of the same geographic areas that have the most restrictive abortion access. The papers considered in this review were published prior to the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization issued on June 24, 2022, which overturned the constitutional right to abortion and triggered a series of state-level total abortion bans, which are in effect in at least 14 states as of November 2022. (Dobbs 2022; The New York Times 2023) Simultaneously, in some urban areas of the US, the demographics of immigrant populations may be shifting in response to newly emerging violent conflicts and the increased frequency of natural disasters resulting from climate change. (Ebi and McLeman, 2022) Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and prominent politicians’ public statements may increase xenophobia experienced by immigrants in the US. (Piazza and Van Doren, 2022; Lantz et al., 2022) Rigorous and up-to-date research is needed to better understand how changing political contexts that influence abortion access, migration patterns, and xenophobia influence access to abortion services among immigrant populations.

Beyond ascertaining key categories of findings in existing published work about US immigrants’ experiences accessing abortion care, this systematic review identified gaps in the literature where further research is needed. First, more work is needed to understand who has access to abortion care and which, if any, sub-populations of immigrants have unmet needs with respect to these services. Several of the studies included in this synthesis did not primarily aim to study immigrant populations. As such, the sample size of immigrants included in the study is comparatively small and makes drawing conclusions challenging. For example, only 67 of 798 participants were foreign-born in the work of Aztlan et al., (2018); only 2 of 27 interviewees were foreign-born in Dennis et al. (2015). These studies were not designed to understand the characteristics of immigrant abortion seekers, nor to assess nuanced differences among unique immigrant communities.

Additionally, no studies considered the rates of immigrants who wished to utilize abortion services but were not able to because of language barriers, lack of understanding of the US. medical system, cost, or other factors. More research is needed to understand if immigrant women access abortion care at lower rates than US-born women because of comparatively lower need, cultural acceptability, and/or more limited access. Toprani (2015) concluded that patients born outside of the US were less likely to have had past abortions than patients born in the US but could not determine if immigrant patients had adequate access to needed abortion services prior to arrival in this country.

Further work is also needed to better understand if there are disparities to access in abortion services among immigrant women who seek abortion care in the US, such as by state of residence. Methods to circumvent limited access in states with abortion bans, such as interstate travel, are likely less accessible options for immigrants, especially those who are in the US without documentation.

Several important gaps in quality highlight potential challenges to interpreting data. Selection bias or a lack of an appropriate comparison group threaten validity and interpretability. Importantly, there is a dearth of rigorous qualitative research to document patient perceptions and to identify reasons why immigrant women may decide to seek abortion care or why they may not receive needed services. Of the two qualitative studies included in this review, Deeb-Sossa and Billings (2014) was deemed of poor quality (i.e., it included less than half of the recommended elements assessed in the quality appraisal) and Dennis et al. (2015) included only two foreign-born participants. (Deeb-Sossa and Billings, 2014; Dennis et al., 2015) The studies were also conducted in different populations. As such, the fact that their findings coalesced around different primary barriers to access highlights the need for more rigorous qualitative research designed specifically to determine if barriers to obtaining abortion care differ by subpopulations of immigrant groups.

The paucity of research to understand the intersection between abortion access and immigration status underscores the challenges of conducting such research in the context of an increasingly hostile national landscape for both immigrants and people seeking abortion care. Prior work presents best practices for conducting research with vulnerable populations, including building trust through ethnographic methods and by engaging trusted community partners; these strategies should be considered to facilitate the expansion of this body of research. (Hernández et al., 2013)

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Key strengths of this review were the breadth of search terms used to identify relevant articles, and the rigor of quality appraisal tools used to assess article quality. One limitation is the possibility of relevant articles that were not identified by the initial search terms or subsequent quality assurance check. In particular, including the term “United States” in search criteria may have excluded US-centric articles that failed to state the country name in their research. Further, searches could have included terms for specific immigrant populations. Relevant papers may have been missed that provide important insight into abortion services access and experiences among US immigrants. Another limitation is that US immigrant populations are an inherently heterogenous group. Due to a dearth of published literature on this topic, comparisons could not be made between subpopulations’ experiences, nor could findings be generalized beyond the populations included in the study.

5. Conclusion

These review findings illustrate what is known about immigrant experiences accessing abortion care in the US, including revealing barriers to abortion services routed in lack of knowledge of US institutional systems and mistreatment in clinical and legal settings due to race or immigration status. These findings merit further research to better understand nuances in experiences among immigrant subpopulations, or among immigrant populations not included in the original articles.

The review also highlights gaps in the literature, particularly with respect to better understanding the experiences of US immigrants who speak a language other than English or Spanish, and of US immigrants who have self-managed abortions or abortions in informal settings. Most importantly, the review identifies that relatively few articles have been published on this topic area. Further high-quality research is needed to identify barriers and concerns for pregnant immigrants in the US who desire abortion services to ensure that they can access timely, legal, and respectful care.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lauren J. Shiman: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sarah Pickering: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Diana Romero: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Heidi E. Jones: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Meghan Hampsey, Marcia Olivo, Sandra Paguay, and Farma Pene for developing the idea for this work and for conducting the initial literature search.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Aztlan E.A., Foster D.G., Upadhyay U. Subsequent unintended pregnancy among US women who receive or are denied a wanted abortion. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeb-Sossa N., Billings D.L. Barriers to abortion facing mexican immigrants in north carolina: choosing folk healers versus standard medical options. Lat. Stud. 2014;12(3):399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A., Manski R., Blanchard K. A qualitative exploration of low-income women's experiences accessing abortion in Massachusetts. Women's Health Issues. 2015;25(5):463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose K.P., Escarce J.J., Lurie N. Immigrants and health care: sources of vulnerability. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):1258–1268. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S., Leong E., Jones R.K. Characteristics of immigrants obtaining abortions and comparison with US-born individuals. J. Women's Health. 2019;28(11):1505–1512. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S., Huynh M., Jones H.E. Differences in abortion rates between asian populations by country of origin and nativity status in New York City, 2011–2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(12):6182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women's Health Organization et al., (2022).

- Ebi K.L., McLeman R. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2022. Climate Related Migration and Displacement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzan K., Guarnieri I. Guttmacher Institute; 2023. State Policy Trends 2023: In the First Full Year Since Roe Fell, a Tumultuous Year For Abortion and Other Reproductive Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F., Quast T., Venanzi A. Factors associated with the timing of abortions. Health Econ. 2020;29(2):223–233. doi: 10.1002/hec.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J., Medina L. US Census Bureau. [May 18, 2024]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2024/04/where-do-immigrants-live.html#:~:text=Highlights%20of%20the%20foreign%2Dborn,over%20the%2010%2Dyear%20span.

- Harvey S.M., Larson A.E., Warren J.T. The dobbs decision—exacerbating US health inequity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2216698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasstedt K. Toward equity and access: removing legal barriers to health insurance coverage for immigrants. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2013;16:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández M.G., Nguyen J., Casanova S., Suárez-Orozco C., Saetermoe C.L. Doing no harm and getting it right: guidelines for ethical research with immigrant communities. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2013;2013(141):43–60. doi: 10.1002/cad.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Abortion in the United States Dashboard 2024 [Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/dashboard/abortion-in-the-u-s-dashboard/.

- Kortsmit K., Nguyen A.T., Mandel M.G., Clark E., Hollier L.M., Rodenhizer J., et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2022;71(10):1–27. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7110a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz B., Wenger M.R., Mills J.M. Fear, political legitimization, and racism: examining anti-Asian xenophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Race Justice. 2022 21533687221125817. [Google Scholar]

- Lara D., Holt K., Peña M., Grossman D. Knowledge of abortion laws and services among low-income women in three United States cities. J. Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015;17(6):1811–1818. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0147-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi S. Supreme court allows trump to enforce ‘Public Charge'Immigration Rule. The justices lifted a nationwide injunction against a sweeping policy targeting poor immigrants. Politico. Politico. 2020 January 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Modesti P.A., Reboldi G., Cappuccio F.P., Agyemang C., Remuzzi G., Rapi S., et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien B.C., Harris I.B., Beckman T.J., Reed D.A., Cook D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell J., Goldberg A., Betancourt T., Lieberman E. Access to abortion in central appalachian states: examining county of residence and county-level attributes. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 2018;50(4):165–172. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Ottawa: 2011. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) For Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; pp. 1–12. 2(1) [Google Scholar]

- Piazza J., Van Doren N. It's about hate: approval of Donald Trump, racism, xenophobia and support for political violence. Am. Polit. Res. 2022 1532673X221131561. [Google Scholar]

- Rader B., Upadhyay U.D., Sehgal N.K., Reis B.Y., Brownstein J.S., Hswen Y. Estimated travel time and spatial access to abortion facilities in the US before and after the dobbs v jackson women's health decision. JAMA. 2022 doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.20424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph L., Foster D.G., Raifman S., Biggs M.A., Samari G., Upadhyay U., et al. Prevalence of self-managed abortion among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29245. -e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero D., Flandrick K., Kordosky J., Vossenas P. On-the-ground health and safety experiences of non-union casino hotel workers: a focus-group study stratified by four occupational groups. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018;61(11):919–928. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J.D. The public health risks of crisis pregnancy centers. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 2012:201–205. doi: 10.1363/4420112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samari G., Nagle A., Coleman-Minahan K. Measuring structural xenophobia: US state immigration policy climates over ten years. SSM-population health. 2021;16 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapales A., Douglas-Hall A., Whitehead H. The sexual and reproductive health of foreign-born women in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times. Tracking the States Where Abortion Is Now Banned 2023 [updated April 14, 2023. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html.

- Toprani A. Repeat abortions in new York City, 2010. J. Urban Health. 2015;92(3):593–603. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-year estimates. 2021.