ABSTRACT

Background

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) can cause hypertension, and severe hypertension can exacerbate the progression of IgAN. However, the long-term kidney outcome of malignant hypertension (mHTN)-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) with IgAN is not well defined.

Methods

A total of 292 individuals with mHTN-associated TMA confirmed by kidney biopsy were included. Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed to adjust for clinical characteristics in the comparison between cases with and without IgAN. Cox regression analysis was utilized to identify risk factors associated with long-term kidney outcome.

Results

A total of 86 mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN patients were compared with 206 mHTN-associated TMA with non-IgAN patients. After PSM, 61 pairs of patients with mHTN-associated TMA were matched. The mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN patients exhibited significantly lower serum albumin, higher 24-hour proteinuria, and a higher ratio of global sclerosis than those with non-IgAN. mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN was independently associated with impaired kidney function recovery [hazard ratio (HR), 0.48; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.24–0.96, P = .038] compared with non-IgAN. This association remained significant after PSM (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.99, P = .047). In addition, mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN was independently associated with kidney replacement therapy (KRT) compared with non-IgAN (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.38–3.88; P = .002). This difference remained significant after PSM comparison (HR, 2.38; 95%CI, 1.14–4.99; P = .021). In addition, mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN patients had a higher incidence of receiving KRT and a lower incidence of kidney function recovery with a 25% reduction in creatinine levels than in non-IgAN patients, regardless of intensive blood pressure control.

Conclusions

The long-term kidney outcomes for mHTN-associated TMA patients with concomitant IgAN are significantly poorer than that of patients with non-IgAN. Monitoring kidney pathological characteristics will aid management and risk assessment at an early stage.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, kidney biopsy, kidney replacement therapy, malignant hypertension, thrombotic microangiopathy

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) can lead to hypertension, which can worsen IgAN progression.

Malignant hypertension (mHTN)-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is linked to poor kidney outcomes.

The long-term kidney prognosis of mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN was previously undefined.

This study adds:

mHTN-associated TMA patients with IgAN have poorer kidney outcomes than those without IgAN.

IgAN is an independent risk factor for deteriorated kidney function and kidney replacement therapy in mHTN-associated TMA.

Kidney pathological characteristics are crucial for early management and risk assessment in mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN.

Potential impact:

Early identification of IgAN in mHTN-associated TMA can guide more aggressive treatment strategies.

Monitoring Kidney pathological features can improve patient prognosis in mHTN-associated TMA.

This study's findings may influence clinical guidelines for managing mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant hypertension (mHTN) is a severe hypertensive emergency characterized by rapid elevation of blood pressure and acute organ damage [1–3]. The incidence of mHTN is higher in males, smokers, and those with a history of kidney artery stenosis [4]. Without prompt treatment, mHTN can cause permanent damage to the central nervous system, cardiovascular system, and kidney [3]. Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a complication attributed to mHTN, which manifests as diffuse capillary loop wrinkling and capsule thickening, marked kidney artery intimal thickening, vessel wall thickening with an ‘onion-peel’ appearance, fibrinoid necrosis, intravascular thrombosis, and so on [5–7]. This may result in end-organ ischemia and infarction, mostly commonly affecting the brain and kidney [8, 9]. However, the risk factors for kidney prognosis in patients with mHTN-associated TMA are still unclear.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), a major cause of primary glomerulonephritis, is closely associated with mHTN. First, IgAN can precipitate the development of hypertension. The kidney plays a crucial role in the regulation of blood pressure. In patients with IgA nephropathy, the deposition of immune complexes in the mesangial areas of the glomeruli leads to local inflammation and kidney damage [10, 11]. Kidney damage leads to sodium retention and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, resulting in renal hypertension. Second, severe hypertension in the context of mHTN causes endothelial dysfunction, and activation of the coagulation cascade can lead to the formation of microthrombi. These can impede blood flow in the kidney microvasculature and exacerbate kidney injury, which can deteriorate kidney function [12, 13]. It is unclear whether mHTN-associated TMA patients with concomitant IgAN have a poor kidney prognosis.

Therefore, this study investigates the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with mHTN-associated TMA, and identifies risk factors that affect kidney prognosis. This study highlights the prognostic significance of concomitant IgAN in mHTN-associated TMA patients and guides the clinical management of mHTN patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and cohort

This prospective study enrolled patients who underwent clinical kidney biopsy at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University from January 2008 to June 2023 and were subsequently pathologically diagnosed with mHTN-associated TMA. Patients with <3 months of follow-up were excluded from the study. Patients were categorized according to the presence or absence of IgA nephropathy as a comorbidity, and the study cohort was divided into two distinct groups: an mHTN-associated TMA with IgAN group (IgAN, n = 86) and an mHTN-associated TMA without IgAN group (non-IgAN, n = 206). To ensure comparability and minimize selection bias, we applied propensity score matching (PSM) to adjust for baseline differences between the non-IgAN and IgAN groups. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University Institutional Review Boards, Guangzhou, China [No. IEC (2022) 710]. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. No financial compensation was provided.

Definitions

Malignant hypertension is defined as a clinical syndrome of accelerated hypertension with target organ damage, primarily characterized by a rapid rise in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >130 mmHg [14]. This condition is often accompanied by hypertensive retinopathy, which includes signs such as retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and optic disc edema [14]. The diagnosis of mHTN with TMA was confirmed based on kidney pathological features, including various pathological changes such as capillary loop wrinkling, capsule thickening, significant kidney artery intimal thickening, vessel wall “onion-peel” thickening, fibrinoid necrosis, intravascular thrombosis, ischemic glomerular alterations, and tubular necrosis [5, 6]. IgAN, diagnosed based on kidney biopsy pathology, refers to a condition in which immunoglobulin A (IgA) accumulates in the kidneys, causing inflammation and potentially progressive kidney damage [15]. In our study, an average systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤130 mmHg in the 3 days before hospital discharge was used as the criterion for intensive blood pressure management, based on consultation with both international and national clinical guidelines [16, 17].

Data collection and kidney histopathology

Blood and urine samples were collected within the first 24 hours on admission, and all patients underwent chest radiography, kidney ultrasound, and echocardiography. Baseline clinical and demographic data were collected, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure measurements, history of hypertension, daily urine protein excretion, hemoglobin, albumin, platelet count, cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein (LDL-c), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-c), urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, uric acid, and serum complement C3 and C4. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [18]. Mean arterial pressure was defined as one-third of SBP plus two-thirds of DBP. Prescription data included statins, beraprost sodium, sulodexide, sacubitril/valsartan, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and other antihypertensive drugs (including α-blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers).

Percutaneous kidney biopsy specimens were routinely processed according to standard protocols. Kidney biopsies were processed for routine light microscopy, electron microscopy, and direct immunofluorescence using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies specific for human IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3, and κ and λ light chains. All kidney biopsy results were assessed by two senior pathologists. In cases of disagreement, a nephrologist participated in further discussions until a resolution was reached. The number and ratio of glomeruli, global sclerosis and segmental sclerosis were collected from the pathology reports. Tubulointerstitial parameters were also recorded, including interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, and tubular epithelial cell sloughing. In addition, vascular parameters were recorded, including arteriolar hyalinosis, fibrinoid necrosis, onion skin lesions, intravascular thrombosis, and intravascular erythrocyte fragments. Electron microscopic evaluation identified subendothelial and mesangial deposits and assessed the degree of endothelial cell swelling.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was recovery of kidney function, which was defined as a >50% decrease in serum creatinine from baseline, a decrease in serum creatinine to normal levels (based on the normal reference range of <1.3 mg/dl established by the hospital), or kidney survival free from hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for at least 1 month for dialysis-dependent patients. The secondary outcome of this study was kidney replacement therapy (KRT), which was defined as the need for hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplantation during follow-up. All patients were followed up by nephrologists and trained nurses through office visits or telephone interviews, and the last follow-up date was 30 June 2023.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, and as the median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed variables and the Student's t-test for normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages), and analyzed with the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test to compare group differences between the non-IgAN and IgAN groups. Time to study outcome was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier model, with survival comparisons between the non-IgAN and IgAN groups based on the log-rank test. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to identify variables associated with kidney outcomes in patients with mHTN-associated TMA. To adjust for the baseline differences and to minimize potential selection bias, we applied PSM between the non-IgAN and IgAN groups. A 1:1 match was performed using the greedy-matching algorithm with a 0.02 caliper [19, 20]. Survival analysis was used to assess the prognosis before and after PSM. All analyses were considered statistically significant if the two-tailed P value was <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline demographics and characteristics

Our final cohort consisted of 292 patients [mean (SD) age, 35.74 (8.66) years] were available for evaluation and were pathologically diagnosed with mHTN-associated TMA, with males constituting 89.0%. A flowchart illustrating this process was presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. Baseline characteristics of patients before and after PSM were shown in Table 1. A total of 206 (70.5%) patients were initially assigned to the non-IgAN group, while 86 (29.5%) patients were assigned to the IgAN group. Compared to non-IgAN patients, IgAN patients were younger, had lower levels of BMI, blood platelet count, serum albumin, and serum complement C3 concentrations, but had higher levels of serum creatinine and 24-hour proteinuria. In addition, the non-IgAN patients were more likely to be treated with α-blockers and beraprost sodium treatment.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Entire cohort | Propensity score-matched cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (n = 292) | Non-IgAN (n = 206) | IgAN (n = 86) | P value | Non-IgAN (n = 61) | IgAN (n = 61) | P value |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 35.74 (8.66) | 37.36 (8.26) | 31.85 (8.390) | <.001 | 34.13 (6.19) | 34.48 (8.17) | .794 |

| Male, n (%) | 260 (89.0) | 187 (90.8) | 73 (84.9) | .142 | 54 (88.5) | 54 (88.5) | 1.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.78 (4.02) | 25.48 (4.13) | 23.08 (3.02) | <.001 | 24.53 (3.99) | 24.05 (3.11) | .455 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 129 (44.2) | 104 (50.5) | 25 (29.1) | .001 | 21 (34.4) | 24 (39.3) | .573 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 84 (28.8) | 66 (32.0) | 18 (20.9) | .056 | 15 (24.6) | 17 (27.9) | .681 |

| Baseline BP status, mean (SD), mmHg | |||||||

| SBP | 160.89 (29.29) | 161.04 (31.17) | 160.52 (24.34) | .880 | 166.02 (32.82) | 161.28 (26.31) | .381 |

| DBP | 101.43 (21.39) | 100.68 (22.28) | 103.24 (19.09) | .351 | 105.16 (23.46) | 102.80 (20.03) | .551 |

| MAP | 121.26 (22.93) | 120.81 (24.07) | 122.35 (20.03) | .601 | 125.43 (25.66) | 122.31 (21.32) | .467 |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 106.59 (22.89) | 107.98 (21.64) | 103.27 (25.46) | .135 | 106.59 (20.76) | 103.80 (26.57) | .520 |

| Blood platelets count, 109/l | 263.63 (87.24) | 271.08 (91.76) | 245.80 (72.75) | .013 | 251.33 (89.48) | 250.67 (79.660) | .966 |

| Serum albumin, g/l | 36.79 (4.87) | 37.57 (4.34) | 35.51 (5.71) | .003 | 38.20 (4.19) | 35.69 (5.97) | .008 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.91 (1.37) | 4.85 (1.34) | 5.04 (1.43) | .272 | 5.01 (1.48) | 4.98 (1.42) | .934 |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR), mmol/l | 1.77 (1.31, 2.32) | 1.81 (1.31, 2.32) | 1.69 (1.31, 2.31) | .686 | 1.91 (1.38, 2.24) | 1.77 (1.30, 2.42) | .539 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l | 3.05 (0.99) | 3.04 (0.96) | 3.07 (1.08) | .776 | 3.06 (0.92) | 3.06 (1.10) | .998 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l | 1.09 (0.54) | 1.06 (0.49) | 1.16 (0.64) | .141 | 1.06 (0.66) | 1.10 (0.50) | .693 |

| Urea nitrogen, median (IQR), mmol/l | 15.0 (10.8, 19.9) | 14.95 (10.50, 19.70) | 15.20 (11.60, 21.30) | .108 | 15.1 (11.10, 19.25) | 14.80 (11.45, 20.95) | .607 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 526.59 (326.20) | 492.93 (287.85) | 607.22 (393.85) | .016 | 531.72 (310.10) | 601.61 (417.22) | .296 |

| eGFR, median (IQR), ml/min/1.73 m2 | 10.32 (6.32, 19.59) | 10.73 (6.83, 20.33) | 9.76 (4.96, 18.84) | .150 | 10.97 (6.25, 20.32) | 10.15 (4.59, 21.41) | .216 |

| 24-h proteinuria, median (IQR), g/day | 1.41 (0.84, 2.55) | 1.26 (0.70, 2.08) | 2.09 (1.09, 3.49) | <.001 | 1.20 (0.62, 1.94) | 2.02 (1.10, 3.42) | <.001 |

| Complement C3, g/l | 1.00 (0.0.23) | 1.03 (0.24) | 0.93 (0.18) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.24) | 0.96 (0.19) | .688 |

| Complement C4, g/l | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.31 (0.12) | 0.31 (0.09) | .889 | 0.29 (0.13) | 0.32 (0.09) | .204 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 60.67 (9.59) | 60.52 (9.98) | 61.00 (8.74) | .718 | 59.07 (10.82) | 60.83 (8.82) | .370 |

| Kidney parenchyma thickness, median (IQR), cm | |||||||

| Left | 1.4 (1.23, 1.60) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.6) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | <.001 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 1.35 (1.1, 1.6) | .194 |

| Right | 1.4 (1.20, 1.60) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.5) | .026 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 1.40 (1.2, 1.6) | .824 |

| Base medications, n (%) | |||||||

| ACEI/ARB | 175 (59.9) | 126 (61.2) | 49 (57.0) | .506 | 36 (59.0) | 38 (62.3) | .711 |

| CCB | 282 (96.6) | 198 (96.1) | 84 (97.7) | .505 | 59 (96.7) | 61 (100.0) | .154 |

| β-blocker | 251 (86.0) | 176 (85.4) | 75 (87.2) | .691 | 49 (80.3) | 54 (88.5) | .212 |

| α-blocker | 181 (62.0) | 142 (68.9) | 39 (45.3) | <.001 | 43 (70.5) | 27 (44.3) | .003 |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 66 (22.6) | 45 (21.8) | 21 (24.4) | .632 | 5 (8.2) | 16 (26.2) | .008 |

| Beraprost sodium | 75 (25.8) | 60 (29.1) | 15 (17.6) | .042 | 17 (27.9) | 10 (16.7) | .139 |

| Sulodexide | 149 (51.0) | 112 (54.4) | 37 (43.0) | .077 | 29 (47.5) | 27 (44.3) | .716 |

| Febuxostat | 58 (19.9) | 44 (21.4) | 14 (16.3) | .321 | 6 (9.8) | 12 (19.7) | .126 |

| Statin | 133 (45.5) | 97 (47.1) | 36 (41.9) | .414 | 17 (27.9) | 26 (42.6) | .088 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

MAP, mean arterial pressure; ITS, interventricular septum thickness; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

After PSM, 61 IgAN patients were matched with 61 non-IgAN patients (Table 1). Baseline characteristics were reassessed after PSM and showed that a satisfactory balance had been achieved between the two groups. Patients with IgAN had significantly lower serum albumin levels [mean (SD), 35.69 (5.97) vs. 38.20 (4.19), P = .008] and higher levels of 24-hour proteinuria [median (IQR), 2.02 (1.10, 3.42) vs. 1.20 (0.62, 1.94), P < .001] compared to non-IgAN patients. Regarding medical treatment, IgAN patients were more likely to be treated with sacubitril/valsartan [16 (26.2%) vs. 5 (8.2%), P = .008], but less likely to be treated with α-blockers treatment [27 (44.3%) vs. 43 (70.5%), P = .003] compared to non-IgAN patients. No differences in other medications were observed between the two groups.

Kidney histopathological characteristics

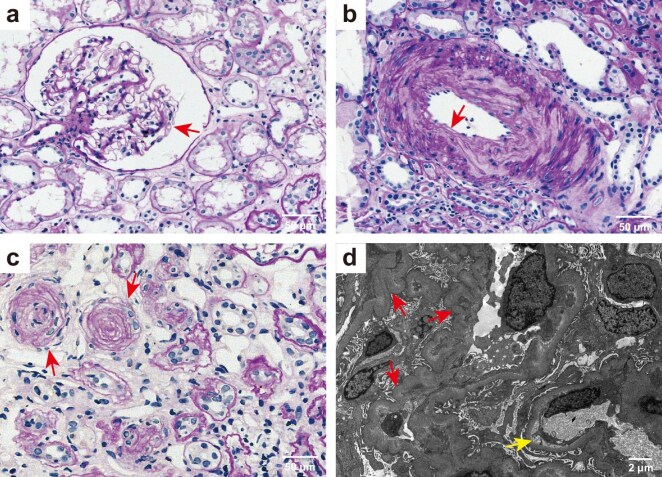

Percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed on all patients with mHTN-associated TMA (Fig. 1). Light microscopic analysis revealed the characteristic pathological alterations in mHTN-associated TMA, including diffuse capillary loop twisting and capsular thickening (Fig. 1a), typical intimal thickening and mucinous degeneration of the kidney artery (Fig. 1b), and the vessel wall thickening with an onion-peel appearance (Fig. 1c). Electron microscopy showed diffuse winkling of the capillary loop and prominent subendothelial widening with flocculent material underneath (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1:

Representative light and electron microscopic findings of malignant hypertension-associated TMA (a) Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining showing diffuse winkling of the capillary loop and capsular thickening (arrow), tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (original magnification ×400). (b) PAS staining showing marked thickening of the medial layer in kidney arterioles (arrow) (original magnification ×400). (c) PAS staining showing vessel walls thickening with an onion-peel appearance and luminal narrowing and occlusion (arrow). Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis are present (original magnification ×400). Scale bars 20 μm, in a–c. (d) Electronic micrograph showed diffuse winkling of the capillary loop (red arrow) and mild segmental subendothelial widening with flocculent material underneath (yellow arrow). Scale bar 2 μm.

Kidney histopathological findings of the patients were shown in Table 2. Compared to non-IgAN patients, IgAN patients had a significantly higher ratio of global sclerosis (P < .001) and tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (P < .001), but had lower ratio of tubular epithelial cell exfoliation (P < .001) and arteriolar hyalinosis (P = .002). After PSM, IgAN patients still had a higher ratio of global sclerosis (P < .001) and a lower ratio of tubular epithelial cell exfoliation (P = .008) compared to non-IgAN patients. There were no differences in the prevalence of tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis, and other vascular lesions, including fibrous necrosis, onion skin lesions, intravascular thrombosis, and intravascular erythrocyte fragments. Thus, there is a higher incidence of chronic pathological changes and a lower incidence of acute changes in mHTN-associated TMA patients with comorbid IgAN.

Table 2:

Histopathologic findings of patients.

| Entire cohort | Propensity score-matched cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy characteristics | Total (n = 292) | Non-IgAN (n = 206) | IgAN (n = 86) | P value | Non-IgAN (n = 61) | IgAN (n = 61) | P value |

| Global lesions, number | |||||||

| Number of glomeruli | 23 (18, 32) | 25 (18, 34) | 21 (16, 26.25) | .001 | 23 (16, 30) | 21 (16, 27) | .167 |

| Global sclerosis | 8 (4, 13) | 7 (4, 10.25) | 12 (7, 19) | <.001 | 6 (3, 9) | 11 (6, 17) | <.001 |

| Segmental sclerosis | 0.5 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 2) | .153 | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 2) | .344 |

| Tubular lesions, n (%) | |||||||

| Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy | <.001 | .246 | |||||

| <25% | 10 (3.5) | 9 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (4.9) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| 25% to <50% | 57 (19.8) | 48 (23.5) | 9 (10.7) | 10 (16.4) | 8 (13.6) | ||

| 50% to <75% | 173 (60.1) | 125 (61.3) | 48 (57.1) | 39 (63.9) | 33 (55.9) | ||

| 75% to 100% | 48 (16.7) | 22 (10.8) | 26 (31.0) | 9 (14.8) | 17 (28.8) | ||

| Tubular epithelial cell exfoliation | 99 (33.9) | 89 (43.2) | 10 (11.6) | <.001 | 23 (37.7) | 10 (16.4) | .008 |

| Vascular lesions, n (%) | |||||||

| Arteriolar hyalinosis | 153 (52.4) | 120 (58.3) | 33 (38.4) | .002 | 31 (50.8) | 25 (41.0) | .276 |

| Onion skin lesions | 175 (59.9) | 129 (62.6) | 46 (53.5) | .147 | 37 (60.7) | 35 (57.4) | .713 |

| fibrinoid necrosis | 97 (33.2) | 67 (32.5) | 30 (34.9) | .696 | 31 (50.8) | 24 (39.3) | .203 |

| Intravascular thrombosis | 52 (17.8) | 34 (16.5) | 18 (20.9) | .368 | 11 (18.0) | 9 (14.8) | .625 |

| Intravascular RBC fragments | 29 (9.9) | 19 (9.2) | 10 (11.6) | .531 | 11 (18.0) | 7 (11.5) | .307 |

RBC, red blood cell.

Risk of concomitant IgAN on the primary outcome of kidney function recovery in patients with mHTN-associated TMA

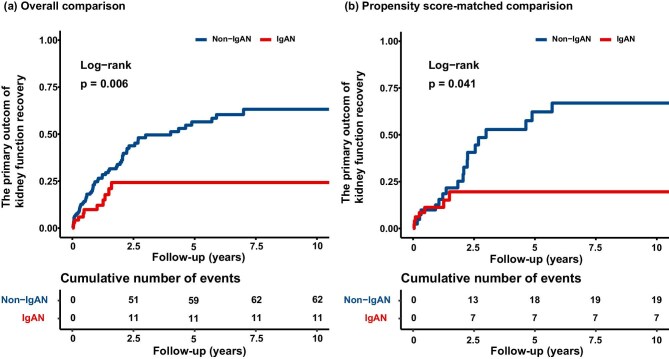

With a median follow-up period of 12.83 months (interquartile range 4.45–32.26), 73 (31.7%) of the primary outcomes occurred. The cumulative effect of patients with IgAN on the hazard of the occurrence of kidney function recovery was significantly lower compared to patients with non-IgAN (overall comparison, P = .006; propensity score-matched comparison, P = .041; Fig. 2). In the crude analysis, patients with concomitant IgAN were significantly associated with impaired kidney function recovery than those with non-IgAN (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22–0.79; P = .008). This difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for both the overall comparison (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24–0.96; P = .038) and the propensity score-matched comparison (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.99; P = .047) (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Cumulative incidence curve for a 50% decrease in creatinine, or a decrease in creatinine to normal, or kidney survival free from replacement therapy for 1 month, and free from dialysis for the patient. The log-rank test is used to compare the survival distributions between the groups, with the P value indicating the statistical significance of the observed differences in the rate of cumulative incidence: (a) overall comparison and (b) propensity score-matched comparison.

Table 3:

Association between non-IgAN and IgAN and study outcome within the crude analysis, multivariable analysis, and propensity score analysis.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) for study outcome | P value |

|---|---|---|

| The primary outcome of recovery of kidney function | ||

| No. of events/no. of patients at risk (%) | 73/230 (31.7) | <.001 |

| Non-IgAN | 62/159 (39.0) | |

| IgAN | 11/71 (15.5) | |

| Crude analysisa | 0.42 (0.22, 0.79) | .008 |

| Multivariable analysisb | 0.48 (0.24, 0.96) | .038 |

| PSMc | 0.41 (0.17, 0.99) | .047 |

| The secondary outcome of KRT | ||

| No. of events/no. of patients at risk (%) | 115/245 (46.9) | <.001 |

| Non-IgAN | 68/170 (40.0) | |

| IgAN | 47/75 (62.7) | |

| Crude analysisa | 2.64 (1.79, 3.88) | <.001 |

| Multivariable analysisb | 2.31 (1.38, 3.88) | .002 |

| PSMc | 2.38 (1.14, 4.99) | .021 |

The HRs from the bivariable model in all patients from the unmatched study.

The HRs from the multivariable stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model, with additional covariate adjustment.

The HR from propensity score-matched sample, constructed using a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching with a 0.02 caliper. The primary outcome was defined as a 50% decrease in creatinine, or a decrease in creatinine to normal, or kidney survival free from replacements therapy for 1 month. The secondary outcome was defined as starting KRT.

In addition, predictors for kidney function recovery in patients with mHTN-associated TMA were shown in Supplementary Table S1. In the multivariable Cox regression model adjusting for confounders with a P < .05 in the univariate regression analysis, IgAN was significantly associated with poorer kidney function recovery compared to patients with non-IgAN (adjusted HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22–0.79; P = .008). Additionally, the results also indicated that higher level of platelet count (adjusted HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01–1.01; P = .044) was related to an increased likelihood of kidney function recovery. The multivariable Cox regression analysis in the PSM cohort also indicated that patients with IgAN was an independent risk factor (adjusted HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07–0.96; P = .043). After PSM, concomitant IgAN (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.99; P = .047) was the only significant factor in the univariate Cox regression. Therefore, we included the factors with P < .05 in the overall comparison, commonly used drugs, and biopsy indicators in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. A comparable pattern was observed in the PSM cohort. After the multivariable Cox regression analysis, patients with IgAN (adjusted HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07–0.96; P = .043) was identified as the only risk factor for the kidney function recovery in patients with mHTN-associated TMA (Table 4).

Table 4:

Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analysis for the primary outcome of kidney function recovery in the PSM cohort.

| Variables | Univariate HR (95%CI) | P value | Multivariable HR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgAN, (yes/no) | 0.41 (0.17, 0.99) | .047 | 0.27 (0.07, 0.96) | .043 |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | .722 | ||

| Blood platelets count, 109/l | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | .347 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | .762 |

| Serum albumin, g/l | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | .709 | ||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | .540 | ||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | .755 | ||

| 24-hour proteinuria, g/day | 0.87 (0.60, 1.25) | .451 | 1.04 (0.69, 1.56) | .853 |

| Complement 3, g/l | 0.64 (0.07, 6.01) | .699 | ||

| Complement 4, g/l | 0.61 (0.01, 53.19) | .829 | ||

| ACEI/ARBs, (yes/no) | 1.11 (0.48, 2.56) | .812 | 1.49 (0.47, 4.69) | .498 |

| β-blocker (yes/no) | 1.08 (0.37, 3.13) | .892 | ||

| α-blocker (yes/no) | 1.43 (0.62, 3.30) | .407 | ||

| Sacubitril/valsartan (yes/no) | 1.00 (0.34, 2.96) | .995 | 1.95 (0.39, 9.69) | .414 |

| Kidney pathology characteristic | ||||

| Segmental sclerosis, number | 1.14 (0.90, 1.44) | .289 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.46) | .432 |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis, n (%) | ||||

| <25% | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 25% to <100% | 0.86 (0.11, 6.43) | .881 | 0.85 (0.08, 9.17) | .894 |

| Arteriolar hyalinosis, n (%) | 0.76 (0.35, 1.65) | .490 | 0.36 (0.12, 1.07) | .066 |

| Onion skin lesions, n (%) | 0.91 (0.41, 2.01) | .819 | 0.63 (0.22, 1.82) | .396 |

| fibrinoid necrosis, n (%) | 1.26 (0.58, 2.73) | .559 | 0.90 (0.31, 2.64) | .847 |

Risk of concomitant IgAN on the secondary outcome of kidney replacement therapy in patients with mHTN-associated TMA

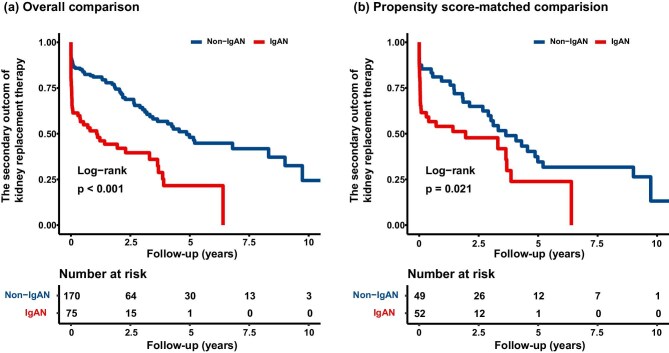

During the follow-up from 2008 to 2023, with a median follow-up period of 17.50 months (interquartile range: 2.17–37.83), 115 (46.9%) patients progressed to the secondary outcome of kidney replacement therapy. Patients with concomitant IgAN showed poorer outcomes of KRT than patients with non-IgAN (overall comparison, P < .001; propensity score-matched comparison, P = .021; Fig. 3). In the crude analysis, patients with IgAN exhibited a higher risk of KRT compared to non-IgAN patients (HR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.79–3.88; P < .001). This difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for both the overall comparison (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.38–3.88; P = .002) and the propensity score-matched comparison (HR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.14–4.99; P = .021) (Table 3).

Figure 3:

Survival curve for KRT in mHTN-associated TMA. The log-rank test is used to compare the survival distributions between the groups, with the P value indicating the statistical significance of the observed differences in the rate of progression to KRT: (a) overall comparison and (b) propensity score-matched comparison.

Risk factors for KRT in patients with mHTN-associated TMA are shown in Supplementary Table S2. In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, patients with IgAN were more likely to require KRT compared to non-IgAN patients (adjusted HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.38–3.88; P = .002). Furthermore, lower eGFR (adjusted HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87–0.98; P = .014), higher serum creatinine (adjusted HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01–1.01; P < .001), and higher 24-hour proteinuria (adjusted HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06–1.34; P = .003) were associated with an increased risk of KRT. Multivariable Cox regression analysis in the PSM cohort also indicated that concomitant IgAN (adjusted HR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.14–4.99; P = .021), higher serum creatinine (adjusted HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01–1.01; P = .004), and without ACEI/ARBs treatment (adjusted HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.87; P = .015) were risk factors for the KRT in mHTN patients with TMA (Table 5).

Table 5:

Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analysis for the secondary outcome of KRT in the PSM cohort.

| Characteristics | Univariate HR (95%CI) | P value | Multivariable HR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgAN (yes/no) | 1.87 (1.09, 3.22) | .023 | 2.38 (1.14, 4.99) | .021 |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | .464 |

| Blood platelets count, 109/l | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | .238 | ||

| Serum albumin, g/l | 0.90 (0.86, 0.95) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | .136 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | <.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | .004 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.95) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | .381 |

| 24-hour proteinuria, g/day | 1.24 (1.06, 1.46) | .007 | 1.10 (0.89, 1.35) | .366 |

| Complement 3, g/l | 0.71 (0.18, 2.76) | .622 | ||

| Complement 4, g/l | 2.28 (0.20, 26.20) | .509 | ||

| ACEI/ARBs, (yes/no) | 0.56 (0.33, 0.94) | .027 | 0.49 (0.28, 0.87) | .015 |

| β-blocker, (yes/no) | 0.99 (0.52, 1.88) | .978 | ||

| α-blocker, (yes/no) | 0.85 (0.51, 1.43) | .550 | ||

| Sacubitril/valsartan, (yes/no) | 1.92 (1.00, 3.69) | .050 | ||

| Kidney pathology characteristic | ||||

| Segmental sclerosis, number | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) | .730 | ||

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis, n (%) | ||||

| <25% | 1 (ref) | |||

| 25 to <100% | 3.17 (0.44, 22.90) | .253 | ||

| Arteriolar hyalinosis, n (%) | 0.63 (0.37, 1.05) | .078 | ||

| Onion skin lesions, n (%) | 1.10 (0.65, 1.86) | .710 | ||

| fibrinoid necrosis, n (%) | 1.08 (0.64, 1.82) | .773 |

Intensive blood pressure control management

The study divided patients into two groups based on their discharge SBP into two groups, including those with SBP ≤130 mmHg and those with SBP >130 mmHg, to assess the impact of intensive blood pressure control. We assessed how the presence of IgAN affects the long-term outlook for kidney health under intensive antihypertensive therapy (Table 6). IgAN patients had a higher incidence of receiving KRT compared to the non-IgAN patients, regardless of the degree of blood pressure (P = .032). In addition, the non-IgAN patients were more conducive to the kidney function recovery of a 25% reduction in serum creatinine levels, regardless of the degree of blood pressure (P < .001). Importantly, non-IgAN patients were more likely to achieve the kidney function recovery of a 50% reduction in serum creatinine levels (P = .002) despite the absence of intensive blood pressure control.

Table 6:

Estimated event rates among intensified antihypertensive therapy with and without IgAN.

| SBP ≤130 mmHg | SBP >130 mmHg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Non-IgAN | IgAN | P value | Non-IgAN | IgAN | P value |

| KD | 36 (54.5) | 23 (62.6) | .453 | 88 (62.9) | 35 (71.4) | .279 |

| KRT | 18 (31.6) | 18 (54.5) | .032 | 50 (44.2) | 29 (69.0) | .006 |

| Recovery 1 * | 40 (71.4) | 15 (45.5) | .015 | 67 (63.2) | 11 (28.9) | <.001 |

| Recovery 2 * | 20 (35.7) | 6 (18.2) | .079 | 42 (40.8) | 5 (13.2) | .002 |

| Recovery 3 * | 5 (23.8) | 2 (11.1) | .303 | 19 (32.8) | 4 (13.3) | .049 |

| Recovery 4 * | 22 (47.8) | 8 (38.1) | .457 | 42 (50.6) | 5 (31.3) | .156 |

Recovery 1 *: A 25% decrease in creatinine, or a decrease in creatinine to normal, or kidney survival free from replacement therapy for 1 month.

Recovery 2 *: A 50% decrease in creatinine, or a decrease in creatinine to normal, or kidney survival free from replacement therapy for 1 month.

Recovery 3 *: Free from dialysis for patients dependent on dialysis at baseline.

Recovery 4 *: 15% increase in the eGFR.

KD, kidney failure.

DISCUSSION

This observational cohort study found that mHTN-associated TMA patients with concomitant IgAN had significantly lower serum albumin, higher 24-hour proteinuria, lower tubular epithelial cell exfoliation, and higher prevalence of global sclerosis and segmental sclerosis in kidney biopsy specimens compared to patients with non-IgAN. The IgAN group also exhibited a lower usage of α-blockers and a higher usage of sacubitril/valsartan. Furthermore, IgAN patients were more likely to experience poorer kidney function recovery (overall comparison, HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24–0.96; P = .038; propensity score-matched comparison, HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.99; P = .047) and progress to KRT outcomes (overall comparison, HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.38–3.88; P = .002; propensity score-matched comparison, HR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.14–4.99; P = .021). Moreover, our study confirmed that concomitant IgAN is a significant risk factor for higher rates of KRT and poorer kidney function recovery, regardless of intensive blood pressure control in mHTN-associated TMA patients.

mHTN often leads to significant kidney complications, and the presence of coexisting IgAN may further worsen kidney outcomes. Patients with mHTN often experience kidney involvement, typically presenting with elevated serum creatinine levels, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, and kidney failure, which are key markers of TMA [21]. In our cohort, we observed that some patients with mHTN-associated TMA also had concurrent IgAN, and this group was more likely to present with higher 24-hour proteinuria levels and lower serum albumin levels. The mechanism of this association may be attributed to IgAN promoting inflammatory responses and vascular damage [10, 22].

Understanding the pathology changes of mHTN-associated TMA is crucial [23, 24]. The primary lesions of TMA are usually concentrated in the kidney arterioles, with pathological features such as fragmented red blood cells in the lumen, onion skin changes in the kidney arterioles, arteriolar fibrinoid necrosis, and intraluminal thrombosis being the main pathological features in mHTN-associated TMA patients [7]. Throughout our study, it was consistently noted that most mHTN-associated TMA patients displayed heightened indicators of kidney vascular damage, such as global glomerulosclerosis, arteriolar hyalinosis, and onion skin lesions. We also found that the IgAN group exhibited a higher proportion of sclerotic glomeruli and more severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Similarly, a France study based on 128 patients with kidney biopsies found that the group with TMA had a significantly greater percentage of sclerotic glomeruli and worse tubulointerstitial fibrosis than those of the group without TMA in IgAN patients [25]. This suggests a mutual exacerbation of glomerular and interstitial damage between IgAN and TMA. In addition, we surprisingly found that mHTN-associated TMA patients coexisting IgAN showed less tubular epithelial cell exfoliation. Tubular epithelial cell exfoliation is often indicative of acute kidney injury [26], serving as a marker of the acute course of mHTN. Therefore, the lower level of tubular epithelial cell exfoliation in the IgAN group may be explained by the chronic nature of IgAN, where gradual immune-mediated damage dominates, in contrast to the acute endothelial injury typically observed in mHTN-related TMA, likely resulting in less severe tubular cell detachment.

While Sevillano et al. [27] confirmed hypertension, as a complication of IgAN, is a risk factor for progressive kidney function decline, the long-term kidney outcomes in mHTN patients with coexisting IgAN remain unclear. Therefore, we investigated the clinical features and kidney prognosis based on whether patients had concurrent IgAN or not. Our cohort study suggests that the presence of IgAN is associated with poor kidney prognosis in patients with mHTN-associated TMA. The IgAN group exhibited a lower incidence of kidney function recovery and a higher requirement for KRT. A potential explanation for the impaired kidney function recovery in the IgAN group could be the combined effects of chronic immune-mediated damage in IgAN and acute endothelial injury in mHTN, creating a ‘double-hit’ to kidney function. Furthermore, we observed more severe glomerulosclerosis and greater interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in patients with coexisting IgAN. A multicenter study [28] from Egypt identified a higher number of sclerotic glomeruli and a larger interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy area as risk factors for end stage kidney disease, partially explaining the increased KRT demand in the IgAN group within our cohort of mHTN-related TMA patients. Similarly, a large UK IgAN cohort [29] reported that 50% of patients progressed to kidney failure or death within a median follow-up of 5.9 years. Our study further substantiates that, even in patients already suffering from mHTN kidney injury, the coexistence of IgAN continues to have a pronounced negative impact on kidney outcomes. Our cohort provides robust evidence that the presence of IgAN is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis, with the likelihood of kidney function recovery being only 0.27 times that of the non-IgAN group and a 2.38-fold increased risk of requiring KRT. Therefore, the coexistence of IgAN can be considered a key and readily identifiable predictor of poor outcomes in patients with mHTN-associated TMA.

The role of platelets in kidney diseases has been a focal point of research [30, 31]. Drolma Gomchok et al. [31] discovered that elevated platelet counts are associated with increased inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, both of which are critical factors in the progression of kidney diseases. Furthermore, a retrospective study by Jiaxing Tan et al. [32] has demonstrated that the platelet-to-albumin ratio is an independent risk factor for poor kidney prognosis in IgAN. Interestingly, our study's findings suggest that elevated platelet levels are a protective factor for kidney function recovery in patients with mHTN-associated TMA. This might be related to the anti-inflammatory effects of platelets by regulating macrophage functions, regulatory T cells, and secretion of proresolving mediators [30].

The choice of antihypertensive medication in mHTN-associated TMA is crucial for disease progression and kidney recovery [33, 34]. ACEI/ARBs, as classic antihypertensive agents, have been demonstrated to confer significant cardio-kidney benefits, particularly in patients with CKD [35]. In a long-term cohort study of IgAN by Kensuke A [34], the ACEI/ARB treatment group had the highest 20-year kidney survival rate. In addition, ACE/ARB treatment has been shown to reduce proteinuria and slow the progression of kidney disease and should be considered in conjunction with intensified antihypertensive strategies [36]. In our cohort, >60% of patients with mHTN-associated TMA were prescribed ACEI/ARBs. Patients receiving ACEI/ARBs had a 0.49-fold reduced risk of requiring KRT compared to those not on these medications, also reflecting the kidney protective effects of ACEI/ARBs.

Effective blood pressure control is essential for disease management and significantly influences quality of life [37, 38]. Intensive blood pressure control strategies, aimed at significantly reducing cardiovascular risks by targeting SBP levels below conventional thresholds, have emerged as a pivotal approach in hypertension management [39–41]. However, there have been no studies reported on how effective blood pressure control correlates with kidney prognosis in patients with mHTN-associated TMA. Our results show that even in patients with SBP ≤130 mmHg at discharge, those with IgAN are still more likely to start KRT and more challenging to achieve improvement in kidney function. Although this conclusion seems to be contrary to previous studies [36, 42], it emphasizes the importance of combined IgAN in kidney prognosis. Further research is necessary to increase the sample size and conduct more detailed blood pressure classifications to determine the optimal discharge blood pressure range for patients with mHTN-associated TMA.

Limitations

Although our study yielded positive outcomes, it is important to recognize that there are several possible constraints that must be considered. First, this study was limited to Chinese patients with mHTN-associated TMA, so caution should be exercised before applying the conclusions of this study to patients with other ethnic backgrounds. Second, a comprehensive classification system for diverse TMA etiologies was not available in all patients with TMA confirmed by kidney biopsy in this study. A diagnosis of mHTN- associated TMA was made only after ruling out other secondary TMA causes. Third, the omission of the Oxford classification variable in the study for patients with IgAN may have introduced bias into the prognostic analysis. Finally, although we used PSM to reduce selection bias, some unmeasured confounding factors may still exist.

CONCLUSIONS

In this cohort study, our study added to the accumulating evidence supporting that the comorbidity of IgAN contributed to a poorer long-term kidney outcome compared to non-IgAN patients with mHTN-associated TMA. The findings suggested that in terms of kidney recovery, monitoring pathological characteristics can facilitate early management and risk assessment.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Wenchuan Li, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

Rong Lian, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

Yuejiao Li, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

Xingji Lian, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China; Department of Geriatrics, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

Zefang Dai, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, NHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology (Sun Yat-sen University) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China.

Zhong Zhong, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, NHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology (Sun Yat-sen University) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China.

Wanxin Shi, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

Yiqin Wang, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, NHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology (Sun Yat-sen University) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China.

Wei Chen, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, NHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology (Sun Yat-sen University) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China.

Jianbo Li, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, NHC Key Laboratory of Clinical Nephrology (Sun Yat-sen University) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangzhou, China.

Feng He, Department of Nephrology, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital, school of medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China.

FUNDING

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82470748, 82070752, 82170737, 82370707), National Key Research and Development Project of China (No. 2021YFC2501302), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant nos. 2022B1515020106, 2023A1515012477), Key Laboratory of National Health Commission, and Key Laboratory of Nephrology, Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China (Nos. 2002B60118 and 2020B1212060028), the Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant no. 202201020273), and Guangzhou Municipal Program of Science and Technology (2024B03J1337 and 202201010166).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to each of the following aspects of the study: J.L. and F.H. designed the research study and revised the manuscript. W.L. and R.L. collected the data and wrote the paper. W.S., Y.W., Z.Z., and Z.D. were responsible for data acquisition. Y.L., X.L., and W.C. were responsible for data analysis and statistical analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the study participants’ privacy. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Saito T, Hasebe N. Malignant hypertension and multiorgan damage: mechanisms to be elucidated and countermeasures. Hypertens Res 2021;44:122–3. 10.1038/s41440-020-00555-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boulestreau R, van den Born B-JH, Lip GYH et al. Malignant hypertension: current perspectives and challenges. JAHA 2022;11:e023397. 10.1161/JAHA.121.023397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubin S, Cremer A, Boulestreau R et al. Malignant hypertension: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis with experience from the Bordeaux cohort. J. Hypertens 2019;37:316. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sevillano ÁM, Cabrera J, Gutiérrez E et al. Malignant hypertension: a type of IgA nephropathy manifestation with poor prognosis. Nefrol Publ Soc Espanola Nefrol 2015;35:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cavero T, Auñón P, Caravaca-Fontán F et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with malignant hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38:1217–26. 10.1093/ndt/gfac248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Timmermans SAMEG, Abdul-Hamid MA, Vanderlocht J et al. Patients with hypertension-associated thrombotic microangiopathy may present with complement abnormalities. Kidney Int 2017;91:1420–5. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim Y-J. A new pathological perspective on thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2022;41:524–32. 10.23876/j.krcp.22.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Castro JT, de S, Appenzeller S et al. Neurological manifestations in thrombotic microangiopathy: imaging features, risk factors and clinical course. PLoS ONE 2022;17:e0272290. 10.1371/journal.pone.0272290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bayer G, von Tokarski F, Thoreau B et al. Etiology and outcomes of thrombotic microangiopathies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:557–66. 10.2215/CJN.11470918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stamellou E, Seikrit C, Tang SCW et al. IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9:1–21. 10.1038/s41572-023-00476-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Binet Q, Aydin S, Lengele J-P et al. Lessons for the clinical nephrologist: an uncommon cause of pulmonary-renal syndrome. J Nephrol 2021;34:935–8. 10.1007/s40620-020-00846-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma J, Li Y, Yang X et al. Signaling pathways in vascular function and hypertension: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023;8:1–30. 10.1038/s41392-023-01430-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathew RO, Nayer A, Asif A. The endothelium as the common denominator in malignant hypertension and thrombotic microangiopathy. J Am Soc Hypertens 2016;10:352–9. 10.1016/j.jash.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boulestreau R, Śpiewak M, Januszewicz A et al. Malignant hypertension:a systemic cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:1688–701. 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El Karoui K, Fervenza FC, De Vriese AS. Treatment of IgA nephropathy: a rapidly evolving field. J Am Soc Nephrol 2024;35:103–16. 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group . KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2024;105:S117–S314. 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chinese Society of Nephrology . [Guidelines for hypertension management in patients with chronic kidney disease in China (2023)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi Chin J Hepatol 2023;39:48–80. 10.3760/cma.j.cn441217-20220630-00650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1737–49. 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai X, Fang Z, Dong Z et al. A propensity score matched comparison of blood pressure lowering in essential hypertension patients treated with antihypertensive Chinese herbal medicine: comparing the real-world registry data vs. randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Hypertens 2023;45:452249269. 10.1080/10641963.2023.2249269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang J, Hu Z, Zhan C et al. Using propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:e45–e6. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halimi J-M, Al-Dakkak I, Anokhina K et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of a patient population with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and malignant hypertension: analysis from the Global aHUS Registry. J Nephrol 2023;36:817–28. 10.1007/s40620-022-01465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wen Y-K, Chen M-L. The spectrum of acute renal failure in IgA nephropathy. Ren Fail 2010;32:428–33. 10.3109/08860221003646345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tong X, Yu Q, Ankawi G et al. Insights into the role of renal biopsy in patients with T2DM: a literature review of global renal biopsy results. Diabetes Ther 2020;11:1983–99. 10.1007/s13300-020-00888-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schnuelle P. Renal biopsy for diagnosis in kidney disease: indication, technique, and safety. J Clin Med 2023;12:6424. 10.3390/jcm12196424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Karoui K, Hill GS, Karras A et al. A clinicopathologic study of thrombotic microangiopathy in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:137–48. 10.1681/ASN.2010111130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaut JP, Liapis H. Acute kidney injury pathology and pathophysiology: a retrospective review. Clin Kidney J 2021;14:526–36. 10.1093/ckj/sfaa142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sevillano AM, Diaz M, Caravaca-Fontán F et al. IgA nephropathy in elderly patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:1183–92. 10.2215/CJN.13251118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohamed ON, Ibrahim SA, Saleh RK et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and predictors of outcome of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: a retrospective study. BMC Nephrol 2024;25:103. 10.1186/s12882-024-03532-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pitcher D, Braddon F, Hendry B et al. Long-term outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2023;18:727–38. 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Margraf A, Zarbock A. Platelets in inflammation and resolution. J. Immunol 2019;203:2357–67. 10.4049/jimmunol.1900899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gomchok D, Ge R-L, Wuren T. Platelets in renal disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:14724. 10.3390/ijms241914724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan J, Song G, Wang S et al. Platelet-to-albumin ratio: a novel IgA nephropathy prognosis predictor. Front Immunol 2022;13:13. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.842362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gosse P, Boulestreau R, Brockers C et al. The Pharmacological management of malignant hypertension. J Hypertens 2020;38:2325. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asaba K, Tojo A, Onozato ML et al. Long-term renal prognosis of IgA nephropathy with therapeutic trend shifts. Intern Med 2009;48:883–90. 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y, He D, Zhang W et al. ACE inhibitor benefit to kidney and cardiovascular outcomes for patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease stages 3–5: a network meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Drugs 2020;80:797–811. 10.1007/s40265-020-01290-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G et al. REIN-2 Study group. Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:939–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71082-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–e646. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W et al. ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–104. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Appel LJ, Wright JT, Greene T et al. Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:918–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa0910975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang W, Zhang S, Deng Y et al. Trial of intensive blood-pressure control in older patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1268–79. 10.1056/NEJMoa2111437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li C, Chen K, Cornelius V et al. Applicability and cost-effectiveness of the systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT) in the Chinese population: a cost-effectiveness modeling study. PLOS Med 2021;18:e1003515. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;387:435–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the study participants’ privacy. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.