ABSTRACT

Objective

Although image‐guided system (IGS) is considered useful in endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), its impact on clinical outcomes needs further evaluation. This study aimed to compare clinical outcomes in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) undergoing ESS with or without IGS.

Data Sources

Two independent reviewers searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, CNKI, WanFang, and VIP to identify comparative clinical studies on clinical outcomes of ESS with or without IGS.

Methods

The primary outcome were total complications. Secondary outcomes were recurrence, revision surgery, blood loss, surgical time, and patient‐reported outcomes. A meta‐analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios (OR) and weighted mean difference (WMD).

Results

A total of 16 studies were included with a total sample size of 3014 patients. Compared with non‐IGS, total complications were less common in IGS group (OR = 0.52, 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.74, p < 0.01), and recurrence rate and revision surgery rate in IGS group was also lower (recurrence rate: OR = 0.31, 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.52, p < 0.001; revision surgery rate: OR = 0.59, 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.98, p = 0.04). What is more, IGS could reduce intraoperative blood loss (WMD = −10.74 mL; 95% CI, −20.92 to −0.57; p = 0.04) and surgical time (WMD = −6.25 min; 95% CI, −9.59 to −2.90, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Compared with non‐IGS, IGS‐assisted ESS was associated with a lower risk of total complications, recurrence, and revision surgery, and with a reduction of intraoperative blood loss and surgical time. These findings support the clinical use of IGS as an adjunct in ESS for CRS patients.

Level of Evidence

3

Keywords: blood loss, chronic rhinosinusitis, complications, endoscopic sinus surgery, image‐guided system, meta‐analysis, recurrence, revision, surgery time, systematic review

This study compared the clinical outcome of the image‐guided system (IGS) in endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) with conventional surgery based on a meta‐analysis of 16 studies. The study demonstrated that, compared with non‐IGS, IGS‐assisted ESS was associated with a lower risk of total complications, recurrence, and revision surgery, and with a reduction of intraoperative blood loss and surgical time.

1. Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a persistent inflammatory disease commonly affecting the sinuses and nasal cavity, with a prevalence of 10% in China [1]. Characterized by symptoms such as nasal blockage, nasal discharge, facial pain or pressure, reduction or loss of olfaction, and sleep disturbance [2], CRS significantly impacts patients' quality of life (QoL) and imposes a substantial burden on healthcare system.

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) is reserved for CRS patients refractory to medical therapies [2, 3]. The pathological sites of CRS involving the frontal, ethmoid, sphenoid, and maxillary sinus are of particular concern due to their proximity to critical anatomical structures such as orbits and skull bases. These regions are traversed by significant blood vessels and nerves, making them high‐risk areas at surgery. ESS has a total complication rate of approximately 3.1% [4], with major complications accounting for 0.36% to 1% of cases [5, 6]. The risk of severe complications, such as orbital and skull base injuries, is notably higher during revision surgery due to dissection challenges posed by heavy scarring and the loss of key anatomical landmarks [7].

Image‐guided system (IGS) has been increasingly applied in ESS, particularly in revision cases with distorted nasal anatomy and the absence of crucial nasal landmarks [8]. With preoperative imaging data to create a three‐dimensional reference map and special signals to track surgical instruments, this technology not only assists surgeons in navigating beyond the limited endoscopic views, but also in identifying anatomical structures during the operation. Despite being considered a valuable tool, the improvement of clinical outcomes with IGS remains uncertain. Previous meta‐analyses have demonstrated the benefits of IGS over non‐IGS in reducing complications during ESS [9, 10, 11, 12]. However, these meta‐analyses need to be further updated due to several limitations, including the undefined patient disease types, fewer endpoints included, and lack of studies involving Chinese patients. Therefore, our meta‐analysis aims to synthesize data from updated studies to compare the benefits of IGS versus non‐IGS in CRS patients undergoing ESS, in terms of safety, efficacy, surgical efficiency, and patient‐reported outcomes (PROs).

2. Methods

The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42024557038). This study did not require ethical committee approval as it did not involve any human or animal subjects, nor did it involve the use of sensitive or identifiable data.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the meta‐analysis, an article had to meet the following criteria:

population/participants: CRS patients;

intervention: ESS with IGS;

comparator/control: ESS without IGS;

outcomes: total complications, recurrence, revision surgery, blood loss, surgical time, and PROs;

study design: RCTs and observational studies.

No restrictions were placed on the geographic regions of the intervention. No language restrictions were applied on the search. Articles in English and Chinese were coded directly; articles in other languages were translated before coding.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles that meet any of the following criteria were excluded:

studies where data cannot be extracted or data formats were incompatible for comparative analysis;

non‐clinical studies or review articles;

duplicated publications.

2.2. Search Strategy

An electronic search of PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, CNKI, WanFang, and VIP databases were executed from the inception up to May 28, 2024 using a search strategy for comparative clinical studies on clinical outcomes of ESS with or without IGS. List of search terms is detailed in Supporting Information: eTable 1. Secondary reference searching was also conducted on all studies included in the published review.

2.3. Literature Screening and Data Extraction

Two researchers (K. Lyu and B. Tan) independently screened literature based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted data according to data extraction form. In case of discrepancies during the screening process, the two researchers resolved them through discussion. The following data extraction content was gathered from each included study:

study identification: author(s), type of citation, and year of publication;

study description: study objectives, location, population characteristics (including age, gender, population, pathology, pre‐surgery Lund–Mackay score, revision cases), study design, sample size, and follow‐up periods;

outcomes: outcome measures, conclusions, and limitations.

2.4. Quality Assessment

For RCTs, Version 2 of the Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) was used to evaluate the randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result with corresponding rating of “low risk,” “some concerns,” or “high risk” [13]. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) tool was used to measure bias. The NOS assigns up to a maximum of nine points for the least risk of bias in three domains: (1) selection of study groups (four points); (2) comparability of groups (two points); and (3) ascertainment of exposure and outcomes (three points) for observational studies [14]. The total score ranged from 0 to 9 points, with higher scores indicating higher quality. Studies were categorized into low, medium, and high‐quality groups using the numbers 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9, respectively. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) guideline was used to ensure standardized reporting of studies. The PRISMA statement adopted for this study comprised a checklist and a flow chart, facilitating consistent and transparent documentation of the meta‐analysis process [15].

2.5. Statistical Methods

Stata 16.1 was used for statistical analysis. For count data, the odds ratio (OR) was used as the effect analysis indicator, while for continuous data, the mean difference (MD) was used as the effect analysis indicator. Heterogeneity among study results was assessed using the χ 2 test (with a significance level set at α = 0.1) and evaluated based on I 2, categorizing I 2 < 25% as low heterogeneity, 25%–50% as moderate heterogeneity, and > 50% as high heterogeneity. Meta‐analysis was conducted using a fixed‐effects model for studies with low and moderate heterogeneity; a random‐effects model was used for studies with high heterogeneity. A funnel plot was generated to assess potential publication bias, and Egger's regression was applied to test the symmetry. The significance level for meta‐analysis was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 772 studies were initially identified from the search strategies, of which 16 were included upon further detailed review with a total sample size of 3014 patients. Among the included studies, three were RCTs and 13 were observational studies. The literature screening process and results are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarized characteristics of 16 included studies. The more specified characteristics of each study are presented in Supporting Information: eTable 2. The studies were conducted in China (n = 6), USA (n = 3), Germany (n = 2), Switzerland (n = 1), Canada (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), and Saudi Arabia (n = 1). The mean follow‐up time of those studies ranged from 3 months to 7.43 years. There was a significant disparity in the proportion of CRSwNP patients and the incidence of revision across studies. With the exception of the study by Sunkaraneni et al. [9], which reported a statistically significant difference in age (IGS: 48.98 ± 14.47 years vs. non‐IGS: 42.64 ± 11.46 years, p = 0.03), and the study by Mueller and Caversaccio [16], where significant disparities were noted in age (IGS: 48.4 years vs. non‐IGS: 42.3 years, p = 0.0007) and preoperative Lund–MacKay score (IGS: 14.3 vs. non‐IGS: 10.0, p < 0.0001), most of the studies (14/16, 87.5%) indicated that the baseline characteristics for patients in the IGS group and the non‐IGS group are comparable, including age, gender, preoperative Lund–MacKay score, and the incidence of revision (if disclosed).

TABLE 1.

Summary of characteristics of studies included in meta‐analysis.

| No. | Author | Year | Study design | Patients, n | Population | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang | 2023 | Retrospective chart review | 200 | CRS | China |

| 2 | Zhang | 2020 | Retrospective chart review | 63 | CRS | China |

| 3 | Galletti | 2019 | Retrospective chart review | 96 | CRS | Italy |

| 4 | Zhao | 2017 | Retrospective chart review | 537 | CRS | China |

| 5 | Diao | 2017 | Retrospective chart review | 236 | CRS | China |

| 6 | Gao | 2015 | Retrospective chart review | 30 | CRS | China |

| 7 | Li | 2013 | RCT | 192 | CRS | China |

| 8 | Sunkaraneni | 2013 | Retrospective chart review | 355 | CRS | Canada |

| 9 | Stelter | 2011 | RCT | 32 | CRS | Germany |

| 10 | Al‐Swiahb | 2010 | Retrospective chart review | 60 | CRS | Saudi Arabia |

| 11 | Mueller | 2010 | Retrospective chart review | 276 | CRS | Switzerland |

| 12 | Strauss | 2009 | RCT | 300 | CRS | Germany |

| 13 | Javer | 2006 | Prospective chart review | 95 | CRS | Canada |

| 14 | Tabaee | 2006 | Retrospective chart review | 239 | CRS | USA |

| 15 | Samaha | 2003 | Retrospective chart review | 100 | CRS | USA |

| 16 | Gibbons | 2001 | Retrospective chart review | 203 | CRS | USA |

3.3. Risk of Bias

The assessment results of bias risk for the included RCTs and observational studies are displayed in Supporting Information: eFigure 1 and eTable 3, respectively. One RCT was deemed to have some concerns, and two studies had high risks of bias. All RCTs had risk in study design due to the lack of blinding. In terms of the randomization process, Strauss et al. [17] selected IGS and non‐IGS group from different periods and did not state the allocation methods. In the study by Li et al. [18], whether to use IGS was decided by the patients themselves. Only Stelter et al. [19] explicitly described their randomization and allocation methods. In the assessment of observational studies, four studies were classified as high quality and nine as medium quality. The average Newcastle–Ottawa score was 6.33 for all the included observational studies.

3.4. Outcomes of Meta‐Analysis

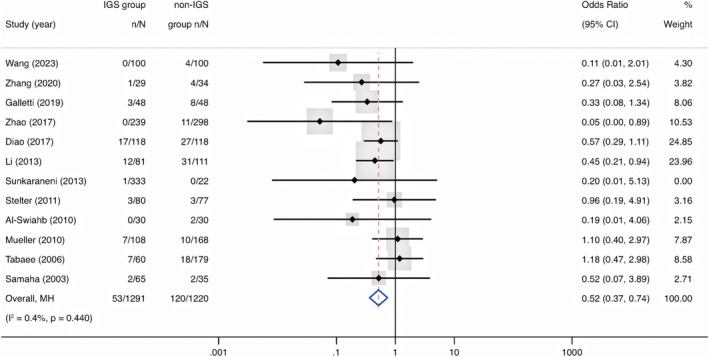

3.4.1. Total Complications

Twelve studies (n = 2511) reported total complications of surgery [15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. The results showed that the total complication rate in the IGS group was lower than that in the control group, with a statistically significant difference (OR = 0.52, 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.74, p < 0.01) (Figure 2). The funnel plot suggested potential asymmetry, but the Egger test did not indicate significant publication bias (t = −2.02, p = 0.071) (Supporting Information: eFigure 2). Furthermore, subgroup analyses were conducted by study design and study site. For study design, both showed similar findings (RCTs: OR = 0.51, 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.99, p = 0.047; observational studies: OR = 0.52, 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.79, p = 0.002). For study site, a significant reduction of total complication rate was observed in China (OR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.61, p < 0.001), with minimal heterogeneity in those studies (I 2 = 5.0%) (Supporting Information: eTable 4).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot showing the odds ratio of complications in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group. Cl = confidence interval; IGS = image‐guided system; MH = Mantel–Haenszel.

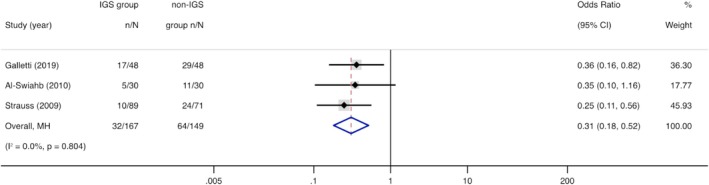

3.4.2. Recurrence

Three studies (n = 316) informed the recurrence of CRS [17, 21, 23]. Compared with non‐IGS, recurrence in IGS group was significantly lower (OR = 0.31, 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.52, p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot showing the odds ratio of recurrence in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group. Cl = confidence interval; IGS = image‐guided system; MH = Mantel–Haenszel.

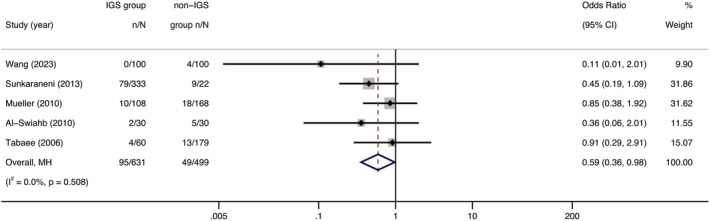

3.4.3. Revision Surgery

Five studies (n = 1130) informed revision surgery of CRS [9, 16, 20, 21, 24]. Compared with non‐IGS, the revision surgery rate was numerically lower in the IGS group (OR = 0.59, 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.98, p = 0.04) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot showing the odds ratio of revision surgery in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group. Cl = confidence interval; IGS = image‐guided system; MH = Mantel–Haenszel.

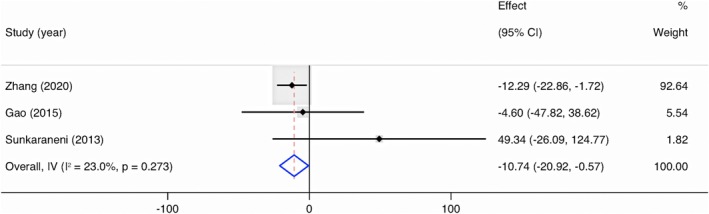

3.4.4. Blood Loss

Across three studies (n = 447) reporting blood loss [9, 26, 28], there was a significant overall pooled mean difference; those in the IGS group experienced a 10.74 mL (95% CI, −20.92 to −0.57, p = 0.04) reduction in blood loss than those in the non‐IGS group (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot showing the mean difference of blood loss in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group. Cl = confidence interval; IGS = image‐guided system; IV = inverse variance.

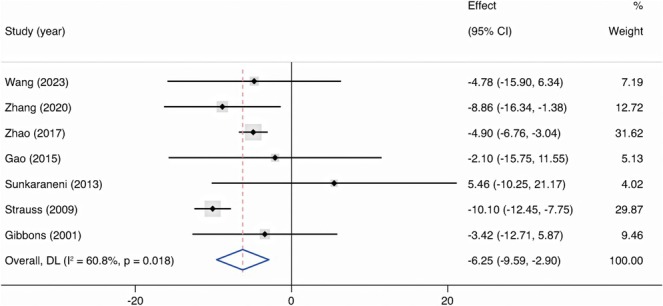

3.4.5. Surgical Time

Across seven studies (n = 1687) reporting surgical time [9, 17, 20, 25, 26, 28, 29], compared with non‐IGS group, the pooled mean reduction in the IGS group was 6.25 min (95% CI, −9.59 to −2.90, p < 0.001). The I 2 index was 60.8%, suggesting wider variability among studies (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot showing the mean difference of surgical time in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group. Cl = confidence interval; DL = DerSimonian‐Laird; IGS = image‐guided system.

3.4.6. Patient‐Reported Outcome

Three comparative cohort studies reported on PROs using disease‐specific quality‐of‐life questionnaires, including 20‐item Sino‐nasal Outcome Test (SNOT‐20) [24], 22‐item Sino‐nasal Outcome Test (SNOT‐22) [23], Rhinosinusitis Quality of Life survey (Rhino‐QoL) [23], and 31‐item Rhinosinusitis Outcome Measures Form (RSOM‐31) [30]. The data could not be combined into a meta‐analysis due to the different patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) used. Tabaee et al. [24] reported no difference in SNOT‐20 score (p = 0.98), while Galletti et al. [23] reported a significant improvement in IGS group compared with non‐IGS group after 1 year from surgery using both SNOT‐22 (p = 0.008) and Rhino‐QoL (symptom impact score: p = 0.002; symptom bothersomeness: p = 0.004 and symptom frequency: p = 0.002), and Javer and Genoway [30] demonstrated a significantly greater overall improvement in RSOM‐31 score following IGS compared with non‐IGS group (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The IGS can be integrated with surgical microscopes or endoscopes, effectively expanding the surgical field. This technology permits surgeons to operate while considering vital adjacent structures such as the skull base, orbit, nerves, and blood vessels. The image navigation system provides real‐time tracking of surgical instruments, ensuring procedural safety and effectiveness [31].

4.1. Total Complications

This meta‐analysis shows a lower likelihood of total complications with IGS than non‐IGS in ESS. This finding aligns with the meta results from Dalgorf et al. [11] and Vreugdenburg et al. [12], which offer high‐level evidence [32]. The consistency across these studies suggests that IGS may be associated with a reduction in total complications. What is more, the subgroup analysis by study design indicates that the results are robust. However, it should be noted that Nobre et al. [10] found no statistically significant difference in total complication rates, possibly due to the limited number of studies included in their analysis [33].

4.2. Recurrence

The recurrence of chronic rhinosinusitis is defined as the reappearance of the disease after a period of remission or improvement, which is manifested by obvious purulence, nasal/sinus symptoms, a decline in quality‐of‐life measures, and radiographic alterations [2, 34]. Recurrence of ESS is thought attributable to several factors, including incomplete removal of diseased tissue, anatomical variations that make the sinuses more prone to blockage, asthma, and the development of nasal polyps [35]. The IGS helps remove cells and bone more completely, preventing the persistence of disease and delaying the onset of recurrent symptoms [36]. The present study provides evidence that IGS may reduce the rate of recurrence in patients undergoing ESS. It is well noticed that in the three included studies, there was a significant difference in the recurrence rates. This may be due to the non‐uniform diagnosis of recurrence and the varied follow‐up duration. Only Galletti et al. [23] specifically defined recurrence as the reappearance of CRS with or without nasal polyps after 1 year. They performed a 12 months follow‐up after the intervention with massive facial CT and Lund—Mackay score. Other studies did not mention how they assess symptoms of recurrence, and the follow‐up period of recurrence was one to 2 years and 22–26 weeks, respectively [17, 21].

4.3. Revision Surgery

Revision surgery is considered when medical management fails to control the recurrent symptoms [2]. The present study found a higher rate of revision surgery in patients undergoing non‐IGS compared with IGS‐assisted ESS, while the meta‐analysis conducted by Sunkaraneni et al. [9] found no statistically significant difference in revision surgery rate. This inconsistency may be due to the difference in the patient's baseline characteristics that affect revision rate, including previous sinus surgery, diagnosis of nasal polyps, and comorbid asthma [35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. What is more, as mentioned in Sunkaraneni et al. [9], the hospital's tier level and surgeon's proficiency are also important factors when considering patients' revision surgery rates.

4.4. Blood Loss

To our knowledge, this is the first review of intraoperative blood loss in ESS using IGS. The mean blood loss was slightly higher in the non‐IGS group, which could potentially be attributed to the fact that navigation can help the surgeon identify important blood vessels during surgery [26]. It should be noted that in the included studies, Sunkaraneni et al. [9] reported a much higher mean blood loss volume in both IGS and non‐IGS groups (IGS: 305.7 mL; non‐IGS: 256.36 mL; p = 0.02), this may be due to the included patients with high proportion of previous revision surgery patients (IGS: 178 revision cases [53.5%]; non‐IGS: 8 revision cases [36.4%]) and a significant difference in age between two groups (IGS: 48.4 years vs. non‐IGS: 42.3 years, p = 0.0007).

4.5. Surgical Time

The present study indicates that IGS may reduce the surgical time. The ability of navigation in IGS helps surgeons swiftly identify anatomical landmarks and plan the surgical approach, which brings real‐world time savings during the actual procedure [43]. The relatively high heterogeneity of the included studies could stem from multiple factors. The overall surgical time includes the preparatory time, for example, device setup and registration time, which ranges from 1 to 20 min [17, 25, 29], and actual surgical time. The surgical time in four studies included preparatory time [9, 17, 25, 26], while the other three studies did not specify whether the surgical time included the preoperative preparation [20, 28, 29]. What is more, Al‐Swiahb and Dousary [21] reported that when surgeons become familiar with the equipment, the preparatory time is typically reduced, from 15 to 5 min, hence the surgeons' proficiency level across studies may also explain the heterogeneity of surgical time.

4.6. Patient‐Reported Outcome

PROs are important in rhinology due to the subjective nature of sinusitis symptoms and the potential impact of sinusitis on the physical, emotional, and social health of a patient [24, 44]. According to Galletti et al. [23] and Javer and Genoway [30], the improvement in overall postoperative quality of life appeared to be further enhanced when IGS assistance was added to ESS. Different from these two studies, Tabaee et al. [24] reported no statistically significant difference in PRO between IGS and non‐IGS. It is well noted that Tabaee et al. [24] did not report the preoperative SNOT‐20 score and compared the postoperative SNOT‐20 score directly, which may introduce baseline bias. The meta‐analysis conducted by Dalgorf et al. [11] reported no statistically significant benefit in RPO of IGS over non‐IGS sinus surgery. However, in their meta‐analysis, they also only used postoperative scores in the included studies and directly synthesized different PROMs, which precludes making meaningful comparisons among various studies [45].

4.7. Limitations

Potential limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings of this study. First, Smith et al. [33] noted that the limitations of sample size and study design prevent the conduct of conclusive randomized trials involving IGS. Given the rarity of total complications in ESS, designing a study to identify a difference in total complication rates between IGS group and non‐IGS group would necessitate enrolling a large number of patients in each group. Furthermore, it is unethical to randomly assign patients away from IGS when it is indicated. Thus, this meta‐analysis is limited by the inclusion of two RCTs with a high risk of bias and small sample size, potentially impacting the reliability of the findings. Secondly, this study mainly included observational studies, which may have biases caused by confounding factors. Although the baseline characteristics were comparable in most studies, not all studies provided a quantification of disease severity and pre‐operative revision rate, which are critical factors of clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the potential preference of patients and surgeons for choosing IGS in complex cases could also introduce a bias. Despite the potential bias towards managing more intricate cases with IGS in sinus surgery, this meta‐analysis demonstrated that IGS has potential clinical benefits in terms of total complication reduction and surgical outcome. In future research, large scale real‐world studies could be explored to evaluate the clinical outcomes of IGS, with a focus on balancing the confounding factors of the two patient groups. Finally, it is important to note that the findings of this meta‐study may not be extrapolated to all patient populations and settings. The heterogeneity of patient populations, surgical techniques, and the varied application of IGS across different healthcare settings suggest that the findings of this study should be applied with caution.

5. Conclusion

There is evidence from published studies that, compared with non‐IGS, IGS‐assisted ESS for CRS was associated with a lower risk of total complications, recurrence and revision surgery, and with a reduction of intraoperative blood loss and surgical time. These findings support the clinical use of IGS as an adjunct in ESS for CRS patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

eFigure 1. Risk of bias assessment for RCTs included in the meta‐analysis (Version 2 of the Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool).

eFigure 2. Funnel plot of total complication rate.

eTable 1. List of search terms.

eTable 2. Specified summary of characteristics of studies included in meta‐analysis.

eTable 3. Risk of bias assessment for observational studies included in the meta‐analysis (Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale tool).

eTable 4. Subgroup analysis of total complication rate.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Xiaohan Hu for polishing the manuscript.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Kangchen Lyu and Baoying Tan had equal participation as the first author and are considered as co‐first authors.

Contributor Information

Kangchen Lyu, Email: lvkch@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Baoying Tan, Email: tanby6@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Ziling Su, Email: suzling@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Jianwei Xuan, Email: xuanjw3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Zhang L., Zhang R., Pang K., Liao J., Liao C., and Tian L., “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Chronic Rhinosinusitis Among Chinese: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Frontiers in Public Health 10 (2022): 986026, 10.3389/fpubh.2022.986026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fokkens W. J., Lund V. J., Hopkins C., et al., “European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020,” Rhinology 58, no. Suppl S29 (2020): 1–464, 10.4193/Rhin20.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Subspecialty Group of Rhinology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Subspecialty Group of Rhinology, Society of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Chinese Medical Association , “Chinese Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Rhinosinusitis (2018),” Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 54, no. 2 (2019): 81–100, 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-0860.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stankiewicz J. A., Lal D., Connor M., and Welch K., “Complications in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A 25‐Year Experience,” Laryngoscope 121, no. 12 (2011): 2684–2701, 10.1002/lary.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramakrishnan V. R., Kingdom T. T., Nayak J. V., Hwang P. H., and Orlandi R. R., “Nationwide Incidence of Major Complications in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology 2, no. 1 (2012): 34–39, 10.1002/alr.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krings J. G., Kallogjeri D., Wineland A., Nepple K. G., Piccirillo J. F., and Getz A. E., “Complications of Primary and Revision Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Laryngoscope 124, no. 4 (2014): 838–845, 10.1002/lary.24401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alanin M. C. and Hopkins C., “Effect of Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery on Outcomes in Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 20, no. 7 (2020): 27, 10.1007/s11882-020-00932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qazi S. M., Bhat A. A., and Patigaroo S. A., “Image Guided Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: First Experience From Kashmir Valley,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery 74, no. Suppl 2 (2022): 800–809, 10.1007/s12070-020-01846-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sunkaraneni V. S., Yeh D., Qian H., and Javer A. R., “Computer or Not? Use of Image Guidance During Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis at St Paul's Hospital, Vancouver, and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Laryngology and Otology 127, no. 4 (2013): 368–377, 10.1017/S0022215113000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nobre M. L., Sarmento A. C. A., Bedaque H. D. P., et al., “Image Guidance for Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 69, no. 10 (2023): e20230633, 10.1590/1806-9282.20230633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dalgorf D. M., Sacks R., Wormald P. J., et al., “Image‐Guided Surgery Influences Perioperative Morbidity From Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery 149, no. 1 (2013): 17–29, 10.1177/0194599813488519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vreugdenburg T. D., Lambert R. S., Atukorale Y. N., and Cameron A. L., “Stereotactic Anatomical Localization in Complex Sinus Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Laryngoscope 126, no. 1 (2016): 51–59, 10.1002/lary.25323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sterne J. A. C., Savović J., Page M. J., et al., “RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials,” BMJ 366 (2019): l4898, 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wells G., Shea B., O'Connell D., et al., “The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non‐Randomized Studies in Meta‐Analysis,” 2000.

- 15. Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., et al., “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews,” BMJ 372 (2021): n71, 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mueller S. A. and Caversaccio M., “Outcome of Computer‐Assisted Surgery in Patients With Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Journal of Laryngology and Otology 124, no. 5 (2010): 500–504, 10.1017/S0022215109992325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strauss G., Limpert E., Strauss M., et al., “Evaluation of a Daily Used Navigation System for FESS,” Laryngo‐ Rhino‐ Otologie 88, no. 12 (2009): 776–781, 10.1055/s-0029-1237352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Z. W., Fang H. Y., Gao M. H., He D., and Li J. S., “Application of Image‐Guided Endoscopic System in Different Chronic Sinusitis,” Chongqing Medical 42, no. 27 (2013): 3236–3238, 10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2013.27.01220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stelter K., Ertl‐Wagner B., Luz M., et al., “Evaluation of an Image‐Guided Navigation System in the Training of Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgeons. A Prospective, Randomised Clinical Study,” Rhinology 49, no. 4 (2011): 429–437, 10.4193/Rhino11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Z., Liu C., Tan B., et al., “Clinical and Economic Benefits of Image‐Guided System in Functional Endoscopicsinus Surgery: A Retrospective Chart Review Study in China,” Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 21, no. 1 (2023): 1, 10.1186/s12962-023-00414-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al‐Swiahb J. N. and Al Dousary S. H., “Computer‐Aided Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Retrospective Comparative Study,” Annals of Saudi Medicine 30, no. 2 (2010): 149–152, 10.4103/0256-4947.60522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Samaha M., Cosenza M. J., and Metson R., “Endoscopic Frontal Sinus Drillout in 100 Patients,” Archives of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery 129, no. 8 (2003): 854–858, 10.1001/archotol.129.8.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galletti B., Gazia F., Freni F., Sireci F., and Galletti F., “Endoscopic Sinus Surgery With and Without Computer Assisted Navigation: A Retrospective Study,” Auris, Nasus, Larynx 46, no. 4 (2019): 520–525, 10.1016/j.anl.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tabaee A., Hsu A. K., Shrime M. G., Rickert S., and Close L. G., “Quality of Life and Complications Following Image‐Guided Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery 135, no. 1 (2006): 76–80, 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao R. W., Huang Y., Zhou L. L., et al., “Clinical Application of Magnetic Navigation Technology in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 23, no. 1 (2017): 24–27, 10.11798/j.issn.1007-1520.201701006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang J. J., “Clinical Analysis of Electromagnetic Navigation‐Assisted Complex Sinus Surgery” (master's thesis of Bengbu Medical College, 2020), 10.26925/d.cnki.gbbyc.2020.000116. [DOI]

- 27. Diao L., “Clinical Analysis of 118 Cases of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Assisted by Image Navigation,” Electronic Journal of General Stomatology 4, no. 12 (2017): 69–70, 10.16269/j.cnki.cn11-9337/r.2017.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gao J. H., “Evaluation of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Assisted by Image Navigation in Chronic Sinusitis,” World Latest Medicine Information 15, no. 43 (2015): 143, 10.3969/j.issn.1671-3141.2015.43.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gibbons M. D., Gunn C. G., Niwas S., and Sillers M. J., “Cost Analysis of Computer‐Aided Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” American Journal of Rhinology 15, no. 2 (2001): 71–75, 10.2500/105065801781543709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Javer A. and Genoway K., “Patient Quality of Life Improvements With and Without Computer Assistance in Sinus Surgery: Outcomes Study,” Journal of Otolaryngology 35, no. 6 (2006): 373–379, 10.2310/7070.2006.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marino M., Citardi M., Yao W., and Luong A., “Image Guidance in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: Where Are We Heading?,” Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports 5, no. 1 (2017): 8–15, 10.1007/s40136-017-0140-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beswick D. M. and Ramakrishnan V. R., “The Utility of Image Guidance in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Narrative Review,” JAMA Otolaryngology. Head & Neck Surgery 146, no. 3 (2020): 286–290, 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith T. L., Stewart M. G., Orlandi R. R., Setzen M., and Lanza D. C., “Indications for Image‐Guided Sinus Surgery: The Current Evidence,” American Journal of Rhinology 21, no. 1 (2007): 80–83, 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benninger M. S., Ferguson B. J., Hadley J. A., et al., “Adult Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Definitions, Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Pathophysiology,” Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery 129, no. 3 Suppl (2003): S1–S32, 10.1016/s0194-5998(03)01397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mendelsohn D., Jeremic G., Wright E. D., and Rotenberg B. W., “Revision Rates After Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Recurrence Analysis,” Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 120, no. 3 (2011): 162–166, 10.1177/000348941112000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thong J. F., Lee J., Yeak S., and Siow J. K., “Use of Image Guidance in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” Clinical Otolaryngology 32, no. 6 (2007): 500, 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2007.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stein N. R., Jafari A., and DeConde A. S., “Revision Rates and Time to Revision Following Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Large Database Analysis,” Laryngoscope 128, no. 1 (2018): 31–36, 10.1002/lary.26741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loftus C. A., Soler Z. M., Koochakzadeh S., et al., “Revision Surgery Rates in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps: Meta‐Analysis of Risk Factors,” International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology 10, no. 2 (2020): 199–207, 10.1002/alr.22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith K. A., Orlandi R. R., Oakley G., Meeks H., Curtin K., and Alt J. A., “Long‐Term Revision Rates for Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology 9, no. 4 (2019): 402–408, 10.1002/alr.22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hentati F., Kim J., Hoying D., D'Anza B., and Rodriguez K., “Revision Rates and Symptom Trends Following Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: Impact of Race on Outcomes,” Laryngoscope 133, no. 11 (2023): 2878–2884, 10.1002/lary.30647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gill A. S., Smith K. A., Meeks H., et al., “Asthma Increases Long‐Term Revision Rates of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With and Without Nasal Polyposis,” International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology 11, no. 8 (2021): 1197–1206, 10.1002/alr.22779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koskinen A., Salo R., Huhtala H., et al., “Factors Affecting Revision Rate of Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 1, no. 4 (2016): 96–105, 10.1002/lio2.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmale I. L., Vandelaar L. J., Luong A. U., Citardi M. J., and Yao W. C., “Image‐Guided Surgery and Intraoperative Imaging in Rhinology: Clinical Update and Current State of the Art,” Ear, Nose, and Throat Journal 100, no. 10 (2021): NP475–NP486, 10.1177/0145561320928202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hopkins C., “Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Rhinology,” Rhinology 47, no. 1 (2009): 10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prasad S., Fong E., and Ooi E. H., “Systematic Review of Patient‐Reported Outcomes After Revision Endoscopic Sinus Surgery,” American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy 31, no. 4 (2017): 248–255, 10.2500/ajra.2017.31.4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Risk of bias assessment for RCTs included in the meta‐analysis (Version 2 of the Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool).

eFigure 2. Funnel plot of total complication rate.

eTable 1. List of search terms.

eTable 2. Specified summary of characteristics of studies included in meta‐analysis.

eTable 3. Risk of bias assessment for observational studies included in the meta‐analysis (Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale tool).

eTable 4. Subgroup analysis of total complication rate.