Abstract

Inflammation damages the epithelial cell barrier, allowing oxygen to leak into the lumen of the gut. Respiring E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae produce proinflammatory lipopolysaccharide, exacerbating inflammatory bowel disease. Here we show that respiring membrane vesicles (MV) from E. coli ameliorate symptoms in a mouse model of gut inflammation. Membrane vesicle treatment diminished weight loss and limited shortening of the colon. Notably, oxygenation of the colonic epithelium was significantly decreased in animals receiving wild type MVs, but not MVs from an E. coli mutant lacking cytochromes. Metatranscriptomic analysis of the microbiome shows an increase in anaerobic Lactobacillaceae and a decrease in Enterobacteriaceae, as well as a general shift towards fermentation in MV-treated mice. This is accompanied by a decrease in proinflammatory TNF-α. We report that MVs may lead to the development of a novel type of a therapeutic for dysbiosis, and for treating IBD.

Subject terms: Microbiome, Applied microbiology, Metagenomics

Introduction

Gut inflammation is a prevalent health concern that manifests in a host of conditions, including IBS1, IBD2,3, Alzheimer’s4,5, and inflammaging6,7. While the etiology of gut inflammation is multifaceted, with risk factors including stress, genetics, infections, diet, and xenobiotics, mounting evidence has implicated the gut microbiome as having an often-pivotal role in the development, progression, and chronic persistence of gut inflammation8–10. Loss of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing obligate anaerobes and an increase in inflammatory, facultatively anaerobic Enterobacteriaceae is a common hallmark of an inflamed gut, where oxidants are thought to drive this gut dysbiosis11–15. In a healthy gut, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) metabolize SCFAs through β-oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation, a process, which converts O2 to H2O and limits the oxygen supplied by blood vessels from diffusing into the gut. Low oxygen levels also limit the production of NO3 from NO caused by the inflammatory response. Nitrate serves as an alternative electron acceptor for the respiratory chain and supports the growth of Enterobacteriaceae16. Diminishing SCFAs or damaging IECs can shift the IECs’ metabolism towards glycolysis that does not consume oxygen, allowing it to diffuse into the gut. Oxygen in the intestinal lumen kills obligately anaerobic bacteria and, together with NO3, causes blooms of facultative anaerobes. The facultative anaerobes that take advantage of these environments are members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, a clade comprised of many pathogens and pathobionts that express a multitude of virulence factors and immunogens, such as inflammatory lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin. The cascade of events arising from oxygenation of the gut can cause or exacerbate gut inflammation, which further disrupts IEC function and helps maintain the chronic presence of facultative microbes13,15. Oxygen-driven dysbiosis of the gut has been confirmed in mouse models for colitis17, colorectal cancer18,19, cancer cachexia20, and graft-versus-host disease21. Oxygen-induced dysbiosis and gut inflammation links an otherwise disparate set of animal models, and the similarities between these signatures and those found in diseases like Alzheimer’s and inflammaging highlights the deleterious role gut oxygenation may play across a host of conditions.

We reasoned that oxygen can be depleted in the gut by bacterial membrane vesicles containing the respiratory chain. We employed membrane vesicles (MVs) from E. coli to remove oxygen from the gut in a mouse model of inflammation. This treatment improved mouse health, reduced inflammation and produced a functional shift in the microbiome, favoring symbionts producing SCFAs.

Results

Membrane vesicles inhibit pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae growth through the reduction of oxygen

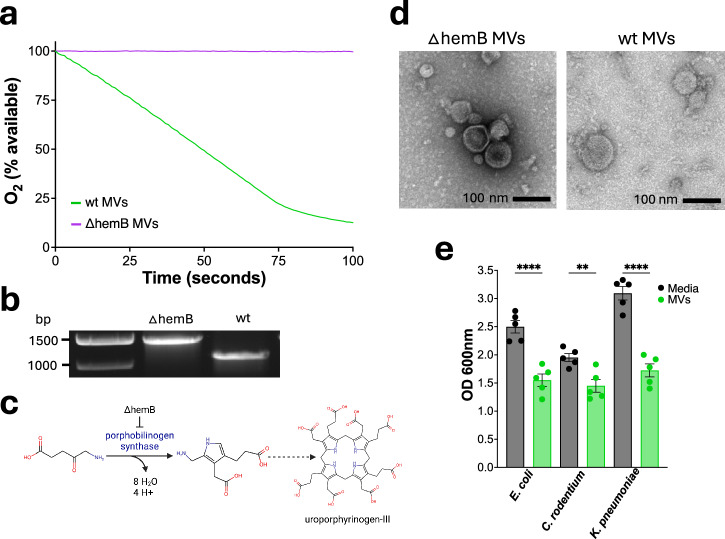

Our approach was to use membrane vesicles from E. coli to deplete oxygen and diminish the growth of facultatively anaerobic bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae in the gut. In order to eliminate contaminating LPS, we used ClearColi, which have a modified LPS containing only the non-inflammatory lipid IVA22. Succinate is commonly present in the gut, is enriched during inflammation23 and is the substrate of membrane-bound succinate dehydrogenase, an enzyme of the respiratory chain. We took advantage of this, and prepared membrane vesicles from E. coli grown aerobically in a medium with succinate. E. coli were disrupted at high pressure, which produces inverted vesicles of the inner membrane, with succinate dehydrogenase facing outward. The vesicles (wt MVs) were first characterized in vitro, where they rapidly depleted oxygen in the presence of succinate (Fig. 1a). A hemB knockout of ClearColi (Fig. 1b) was made to produce control vesicles (∆hemB MVs) which cannot biosynthesize heme b an essential cofactor for oxidases (Fig. 1c). As expected, ∆hemB vesicles do not respire (Fig. 1a) but have similar morphology to wild type vesicles (Fig. 1d). Next, we examined the ability of MVs to suppress the growth of three different species of Enterobacteriaceae - Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Citrobacter rodentium—under aerobic conditions (Fig. 1e). After 7 hours, the wt MVs inhibited the growth of all three strains indicating they may be effective at reducing the burden of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae in vivo.

Fig. 1. Membrane vesicles inhibit the growth of pro-inflammatory Enterobacteriaceae by consuming oxygen.

a Respiration of membrane vesicles. The medium contained 20 mM potassium phosphate, 650 mM succinate at a pH of 7 with 325 µg/mL of either wt or ∆hemB MVs. b Electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel for 1 h, hemB was amplified with P3 and P4 primers. Expected amplicon sizes for ∆hemB (hemB::kanR) were 1466 bp and wt hemB was 1114 bp. c Pathway of heme b biosynthesis from 5-aminolevulinate. d Transmission electron microscopy images of ∆hemB and wt MVs. e Cell density of Escherichia coli AR350, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 43816, and Citrobacter rodentium ATCC 51459 after 7 hours of growth in LB aerobically and shaking at 37 °C n = 5 for all cultures. Cultures were inoculated with 1/400 dilution of overnight cultures, 13 mM succinate and 1.6 mg/mL of MVs. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test, bars represent mean ± SEM. Adjusted p values were as follows, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Membrane vesicles protect against colitis-induced weight loss and colon shortening

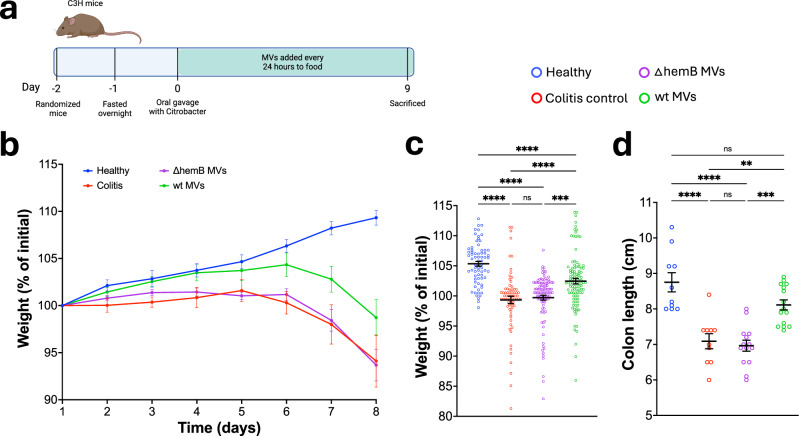

Having designed membrane vesicles that inhibited the growth of C. rodentium through reducing oxygen, we next tested if these vesicles could be used as a therapeutic to reduce inflammation. To accomplish this, we added membrane vesicles to food in a C. rodentium-induced colitis model in C3H/HeNCrl mice (C3H) (Fig. 2a). Mice were weighed every 24 hours to assess progression of the disease24. Mice treated with wt MVs had a significantly higher body weight than the colitis and ∆hemB MVs groups, indicating that the treatment reduced the severity of the disease (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, weight loss between the colitis control and ∆hemB MVs groups was nearly identical, suggesting that the improvement in health by treatment with wt MVs is due to the vesicles’ ability to reduce oxygen. C3H mice are unable to clear C. rodentium which means that unless the pathogen is fully eradicated, as with antibiotic treatment, the infection will be fatal. This is why although we see an improvement in the health of wt MV treated mice, they still lose weight. Colon length also decreases in colitis and serves as an important marker of disease. We observed a significant increase in the colon length of mice treated with the wt MVs, while there was no change in the ∆hemB MVs group (Fig. 2d). Taken together, these results show that treating mice with respiring MVs reduces disease severity.

Fig. 2. Membrane vesicles ameliorate colitis.

a Schematic of the mouse experiment. b Body weight of mice as a percent of the initial weight recorded at day 1. Points represent the mean ± SEM. Healthy group n = 10, colitis control n = 10, ∆hemB MVs n = 15, and wt MVs n = 15. c Compiled percent of initial weight for each mouse from days 2 to 8. Healthy n = 70, colitis control n = 70, ∆hemB MVs n = 105, wt MVs n = 105. Line and error bars represent the mean ± SEM. Significance determined using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Adjusted p values were as follows, ***p = 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001. d Length of colon distal of the cecum. Healthy n = 10, colitis control n = 10, ∆hemB MVs n = 14, wt MVs n = 15. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. Significance determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Adjusted p values were as follows, **p = 0.0021, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Membrane vesicles reduce the colonic epithelium and modulate the cytokine response

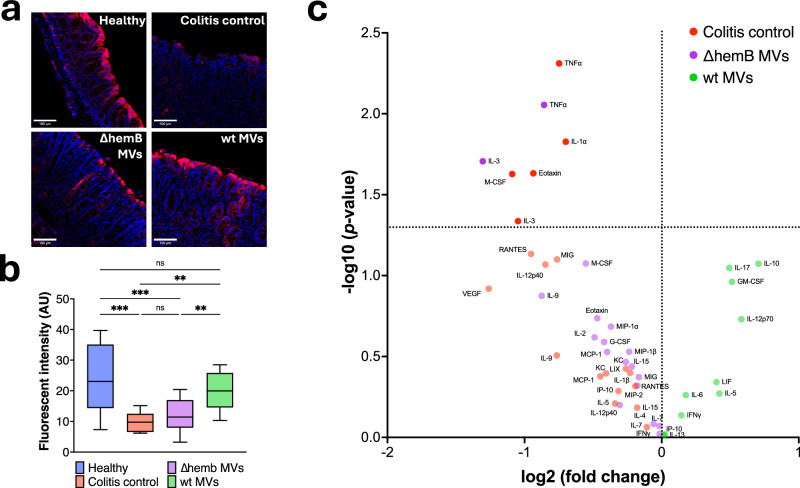

In a healthy gut, the level of oxygen is low in the epithelial layer, but increases with inflammation18. We therefore compared oxidation of the epithelial layer of mice with colitis to that of animals treated with MVs using pimonidazole labeling. Pimonidazole is a 2-nitroimidazole that forms covalent bonds with thiols of amino acids upon reduction. The pimonidazole-protein adducts can then be probed with fluorescently-labeled antibodies allowing for visualization of oxygen levels in the tissue25. Mice treated with wt MVs had less oxygen in their intestinal epithelial surfaces than mice in the colitis control or those treated with ∆hemB MV (Fig. 3a, b). We specifically quantified the pimonidazole adducts along the epithelium of the distal colon, as this is where C. rodentium establishes before moving into the proximal colon and therefore where we would expect to see the most cell damage and oxygenation26. Analyzing the histopathology of the colonic tissue, we did not observe differences between the colitis groups (Fig. S1). This is potentially due to the severe progression of the disease coupled with the semiquantitative nature of the analysis.

Fig. 3. Membrane vesicles reduce the colonic epithelium and modulate the cytokine response.

a Representative images of the distal colonic epithelium. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with pimonidazole 1 hour before euthanasia. Pimonidazole adducts were detected using Hypoxyprobe-1 RED ATTO 594 dye-conjugated IgG1 mouse monoclonal antipimonidazole antibody (red fluorescence). Hoechst 33342 was used as a nuclear counter stain (blue fluorescence). No adjustments were made to the images. b Quantification of the RED ATTO 594 dye. 3 sections of the distal epithelium were quantified and averaged per mouse, healthy n = 10, colitis control n = 10, ∆hemB MVs n = 14, and wt MVs n = 15. Box displays the range from the first to the third quartile, with a line at the median value, and Tukey whiskers. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Adjusted p values were as follows, *p = 0.0147, **p = 0.0024, ***p < 0.001. c Volcano plot displaying serum cytokines that were increased in, colitis control vs. wt membrane vesicles in red, ∆hemB MVs vs. wt MVs in purple, and wt MVs vs. colitis control and ∆hemB MVs in green.

Having observed that wt MVs reduced oxygen in the gut we next wanted to determine if the treatment changed the cytokine response. Inflammation is modulated through cytokines, and we suspected that because MVs improved colitis symptoms they may be modulating the cytokine response27. The differences in cytokine concentration were visualized in a volcano plot where each point and color represent a cytokine enriched in that corresponding group (Fig. 3c). The comparisons made were between the ∆hemB MVs to wt MVs group in purple, colitis control to wt MVs group in red and wt MVs to both combined ∆hemB and colitis control groups in green. Notably, treatment with MVs decreased cytokines associated with inflammation in the C. rodentium-infected mice. The pro-inflammatory TNF-α was the most significantly decreased cytokine in wt MVs treated group. In contrast, the anti-inflammatory IL-10 was the most enriched (p-value 0.08) cytokine in the wt MVs group. TNF-α and IL-10 have been strongly associated with worsening or ameliorating colitis respectively28. Moreover, the expression of these cytokines in colitis has been linked to the microbiome. In IL-10 knockout mice the development of colitis is contingent on a gut microbiota, as germ-free IL-10 knockout mice do not develop inflammation29. TNF-α was first identified through studying bacterial infections and the success of anti-TNF-α in treating IBD has been linked to patients’ microbiomes, highlighting the relationship between TNF-α and the microbiome28,29. IL-3 is the most suppressed in the wt MV group and is elevated in IBD patients30. Taken together, these data suggest that MV treatment reduces the inflammatory cytokine response, likely through interactions with the microbiome.

Membrane vesicle treatment modifies the microbiome

To determine if the MV treatment altered the active colitis microbiome, we analyzed the stool microbiome through metatranscriptomics. RNA from mouse stool was extracted and sequenced with Illumina sequencing, then taxonomy was annotated using Kaiju31. A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was generated using bacterial genera as features to visualize the similarities and differences between the microbiomes of the groups (Fig. 4a). This analysis showed that the wt MV treated group was distinct from the colitis control and ∆hemB MV groups which clustered closely together. To better understand these changes, we compared the taxonomy of individual samples and the phylogeny of the groups (Fig. 4b, c). In the phylogenetic tree we see that the microbiome is primarily made up of a small set of highly abundant families belonging to the clades Verrucomicrobiota, Bacteroidia, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacilli and Clostridia with an overall drop in diversity in all the C. rodentium-infected groups relative to the healthy group. This loss of diversity as well as the PCoA separation show that in this model the wt MV treatment did not protect from colitis by reestablishing the initial diversity. To better understand the microbiome differences that may have contributed to the therapeutic effects of removing oxygen from the gut we used linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). LEfSe is a method that uses both significance and effect size to rank features that are most likely to explain the differences between the groups32. Using LEfSe we saw that the top five distinguishing features between the wt MV and ∆hemB MV/colitis control groups at a family level were an increase in Lactobacillaceae and a decrease in Bacteroidaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, and Akkermansiaceae (Fig. 4e). The LEfSe comparisons were made between colitis control or ∆hemB MV groups to wt MV and wt MV to ∆hemB and colitis control combined. The differences between the colitis control and the wt MV group were less significant than the ∆hemB MVs and as such these comparisons were not in the top five. However, though not significant, all the families shown as enriched in the ∆hemB MV group were also enriched in the colitis control relative to the wt MV group (Fig. S2). We also visualized the differences between taxa identified through LEfSe to quantify relative abundance and significance changes between the groups (Fig. 4f). Based on previous studies, the relative decrease in Enterobacteriaceae and increase in Lactobacillaceae likely plays a significant role in the improvement in mouse health we observed33–35. Lactobacillaceaea have been previously shown to be inhibitory to Enterobacteriaceae and it is possible that the decrease in relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae is due to inhibition from the increase in Lactobacillaceaea36. We therefore ran a Spearman correlation and found a weak and non-significant negative correlation between the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillaceae, indicating that the decrease of Enterobacteriaceae in the wt MV treated mice is unlikely to be primarily driven by the increase of Lactobacillaceae (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4. Membrane vesicle treatment modifies the microbiome.

a PCoA of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity using bacterial genera as features. Each point represents a single sample, points are colored by groups. Healthy n = 10, colitis control n = 10, ∆hemB MVs n = 9, wt MVs n = 12. b Phylogenetic tree of all bacterial families identified in the samples. Heatmap depicts average z-score of each bacterial family within a group. Bars represent the average relative abundance of bacterial families within a group. c Bar graph showing the relative abundance of all bacterial genera identified in each sample, as well as the average for each group. d Linear regression for the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae to Lactobacillaceae within the colitis control, ∆hemb MVs and wt MVs groups. Each point represents a single sample (n = 31), best-fit line in red. e Top 5 LEfSe results represented by LDA-score of wt MVs group to ∆hemB MVs group. f Relative abundance of the top 5 LEfSe results between wt MVs group and colitis control or ∆hemB MVs group, only significant differences shown. All boxes display the range from the first to the third quartile, with a line at the median value, and Tukey whiskers. For Lactobacillaceae comparison significance was determined using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons with adjusted p value, *p < 0.05. For all other comparisons significance was determined using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, p values were as follows, *p < 0.05, **p = 0.0073.

MV treatment alters the metatranscriptome and metabolome

Having established that MV treatment altered the microbiome, we wanted to understand the mechanism behind these changes by investigating the metatranscriptome and metabolome of the stool microbiome. To accomplish this cDNA reads were annotated to proteins using the program DIAMOND37 and then assigned to SEED subsystems using MEGAN38. A PCoA of the SEED annotated subsystems was used to understand how the conditions within different groups changed the expression of pathways within the microbiome (Fig. 5a). This analysis showed a similar result to that seen in the PCoA using taxonomic data; mainly that the pathways in healthy mice clustered closely together, the colitis control and ∆hemB MV treated mice clustered together, and the wt MVs clustered largely together. This indicates that both inducing colitis and treating with wt MVs caused an observable change in the microbial metatranscriptome. To better understand what transcriptional changes are driving the separation between these groups, biplot vectors were used to display the top two subsystems with the highest loadings and depict how they influenced the separation of the samples. Through this we found that the 50S ribosomal subunit and mixed acid fermentation best separated the samples. Mixed acid fermentation is a metabolic pathway, while changes in expression of the 50S ribosomal subunit suggest differences in translation and likely energy expenditure between the groups39. Collectively these results suggest that the main influence of the MV treatment is on pathways associated with energy. In light of this, we generated a heatmap of all the energy subsystems in the SEED database, which showed three distinct clusters associated with one of either healthy, colitis control and ∆hemB MV, or wt MVs groups (Fig. 5b). The clustering of pathway abundance within groups reinforced the observation that MV treatment induces transcriptomic changes within energy associated subsystems. We then compared the abundance of reads across all energy subsystems and reported relevant systems that were significantly different between the wt MVs treatment and the colitis control or ∆hemB MV groups to highlight the changes caused by wt MVs in a colitis environment (Fig. 5c). These results were then grouped into central metabolism, fermentation, and respiration to observe trends in the context of these larger systems. Three subsystems within the fermentation group were identified as significantly different: acetoin and butanediol fermentation, lactate fermentation, and mixed acid fermentation all of which were higher in the wt MV treated group than in any of the other groups. Conversely, three subsystems within respiration: cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase, Na-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (Na+ NQR), and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and fumarate reductase (FRD) complexes, were all lower in the wt MV group relative to the other colitis groups. These results suggest that by reducing oxygen in the gut, the wt MVs are steering the microbial metabolism away from respiration and towards fermentation.

Fig. 5. MV treatment alters the metatranscriptome and metabolome.

a PCoA of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity using SEED subsystems as features annotated using MEGAN. Each point represents a single sample, points are colored by groups, dashed arrows represent biplot vectors of the top two loadings. Healthy n = 10, colitis control n = 10, ∆hemB MVs n = 9, wt MVs n = 12. b Heatmap of all SEED energy subsystems annotated by MEGAN, clustered by subsystems (rows). c Selected energy subsystems that showed significant differences in number of assigned transcripts between wt MVs and either ∆hemB MVs or colitis control groups, organized into subcategories. All boxes display the range from the first to the third quartile, with a line at the median value, and Tukey whiskers. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. d Principal component analysis from untargeted LCMS analysis with analytes as features. Each point represents a sample, and points are colored by group. Healthy n = 7, ∆hemB MVs n = 4, and wt MVs n = 4. e Comparison of peak area for glyceric acid between wt MVs and ∆hemB MVs, identified with LCMS and compound discoverer. Significance was determined using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, *p = 0.0286.

Fermentation and respiration are endpoints of metabolism, so to understand the changes upstream of these systems, we looked at the significantly differential pathways within central metabolism between the groups. We observed that enzymes associated with glycolysis and gluconeogenesis were more highly transcribed in the microbiomes of mice treated with wt MVs. While these pathways share a majority of the same reversable enzymes, they accomplish opposing goals either the catabolism or anabolism of glucose. To separate the reactions, we looked at the transcription of two irreversible enzymes, 6-phosphofructokinase (EC 2.7.1.11) and pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40), which are found in the glycolytic pathway40–42. Both enzymes were transcribed at higher relative abundance in the wt MV treated samples than in samples from the other groups (Fig. S4). 6-phosphofructokinase can be bypassed during gluconeogenesis via the irreversible fructose-bisphosphatase (EC 3.1.3.11), which is unchanged in the colitis samples, or the reversable diphosphate-fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase (PFP) (EC 2.7.1.90) that is transcribed at a lower relative abundance in the wt MV treated samples. Pyruvate kinase converts phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate and can be bypassed during gluconeogenesis via the reversable enzymes pyruvate water dikinase (EC 2.7.9.2) or pyruvate phosphate dikinase (EC 2.7.9.1). Alternatively, phosphoenolpyruvate can be catabolized through the irreversible enzymes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase using GTP (EC 4.1.1.32) or phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase using ATP (EC 4.1.1.49). Notably, all four of these enzymes involved in catabolizing phosphoenolpyruvate remain relatively unchanged in the colitis treatments. Although we cannot make a conclusion from the increased abundance of PFP because it is reversable, the transcriptional abundance of the other observed enzymes suggest that glycolysis is more relatively abundant in the wt MV treated microbiomes than in the colitis control or ∆hemB MV groups. During anaerobic glycolysis bacteria use pyruvate formate lyase (PFL) to catalyze the conversion of coenzyme A (CoA) and pyruvate into acetyl-CoA and formate43,44. PFL is strongly linked to anaerobic glycolysis due to its oxygen sensitivity, and its expression in E. coli increases by a magnitude when grown in anaerobic versus aerobic conditions. Viewed holistically, these data indicate that treatment with wt MVs increases anaerobic glycolysis and the generation of ATP through substrate level phosphorylation. The pyruvate from this process is then metabolized into lactate or acetyl-CoA via PFL and converted into acetate and ethanol through mixed acid fermentation45. This increase in acetate can be inhibitory and is likely compensated for by utilizing the NADH from butanediol metabolism to further catabolize acetate into ethanol46. In agreement with this we observed an increase in the transcription of acetate kinase (E.C. 2.7.2.1) in the wt MV treatment relative to the other colitis groups (Fig. S4), which in conjunction with a decrease in TCA enzymes suggests an increase in acetate production. Contrary to the increased anaerobic glycolysis and fermentation we observe with the wt MV treatment, the microbiomes of mice in the colitis and ∆hemB MV controls have higher relative levels of transcripts associated with the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). It appears that relative to the other groups, the microbiomes within the ∆hemB MV and colitis control mice are using the TCA to power the ETC to generate ATP through respiration.

After discovering that wt MV treatment alters the metatranscriptome relative to the colitis control groups, we sought to determine if this change was reflected in the metabolome. To accomplish this, we analyzed the stool using untargeted Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS). We compared healthy, and colitis treated with ∆hemB MV or with wt MV groups. A principal component analysis of these untargeted metabolomics results shows a separation between all three groups indicating changes in the metabolome between the healthy and colitis groups and between ∆hemB and wt MV treatments (Fig. 5d). Sparse partial least squares-discrimination analysis was then used to identify the metabolites that best described the difference between the ∆hemB and wt MV treatments. While most of the metabolites were unidentified, the annotated metabolite that best described the difference between these groups was glyceric acid. Glyceric acid has been found to be enriched in the stool of colitis and IBS patients and was hypothesized to be a consequence of liberated triacylglycerols (TAGs) associated with the colon mucosa47,48. TAGs are energy stores for the host cells and can be metabolized into glyceric acid, therefore this glyceric acid in the large intestine can be attributed to the liberation of TAGs during host cell death49 The lower levels of glyceric acid in the wt MV treated stool (Fig. 5e) suggests that by reducing oxygen in the gut, the vesicles may help protect against mucosal degradation which is prevalent in gut inflammation.

Discussion

Emerging research is associating gut inflammation with an increasing range of otherwise disparate health conditions. While studies have found multiple factors can cause or predispose a person for gut inflammation, mounting evidence suggests that the microbiome can have a causal role. Gut inflammation is often correlated with an increase in proinflammatory facultative bacteria which studies have shown is driven by the formation of nitrate, and from oxygen leaking into the gut. We therefore tested how oxygen-reducing membrane vesicles would affect colitis, an inflammatory gut disease.

Under most conditions facultatively anaerobic bacteria within the family Enterobacteriaceae grow better aerobically or in the presence of alternative electron acceptors such as nitrate than anaerobically50,51. This is due to the more efficient production of ATP generated by oxidative phosphorylation in respiration versus the substrate-level phosphorylation carried out in fermentation. It has been shown that the growth of Enterobacteriaceae members such as C. rodentium during colitis is strongly supported by the ability to use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor52. The reduction of oxygen can be achieved with reducing agents; however, these compounds are limited in their therapeutic efficacy as they can be toxic and are consumed by their reaction with oxygen. By contrast, bacterial respiration is enzymatic and produces carbon dioxide and water. We reasoned that Enterobacteriaceae can be outcompeted by their respiring membrane vesicles. Membrane vesicles from E. coli rapidly consumed oxygen in the presence of succinate commonly present in the gut.

We found that these MVs inhibit the growth of gut pathogens in vitro, including murine C. rodentium as well as E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolated from humans. C. rodentium displays an attaching and effacing pathotype causing gut inflammation in mice which mirrors the pathology of colitis in humans26,53. C. rodentium respiration leads to a bloom during gut inflammation, and we therefore chose a C. rodentium-induced colitis model to test the effect of MVs.

Adding MVs to the food of mice with induced colitis mitigated weight loss and colon shortening. Notably, oxygen levels at the epithelial layer were significantly diminished, as measured by pimonidazole. In agreement with this, proinflammatory TNF-α was decreased in MV treated animals, while anti-inflammatory IL-10 was elevated by comparison to mice with colitis. By contrast, MVs made from an E. coli hemB mutant lacking cytochromes had no effect.

Metatranscriptomics report both the taxonomy and the expression of functional pathways of the microbiome54, and we used it to evaluate changes in response to treatment with MVs. One of the main findings of the taxonomic analysis was that the MV treatment caused an increase in Lactobacillaceae which have been shown to be anti-inflammatory, and a decrease in pro-inflammatory Enterobacteriaceae. Lactobacillaceae do not respire and are at a disadvantage in aerobic conditions55. These changes are consistent with MVs decreasing oxygen in the gut.

Analysis of the expression data shows an increase in pathways for lactate and mixed acid fermentation as well as acetoin and butanediol fermentation in MV-treated mice. Lactate fermentation is consistent with a significant increase in the relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in mice treated with MVs. While it is possible that fermenting bacteria such as Lactobacillaceae are contributing to the increase in mixed acid fermentation, this metabolism is predominantly associated with the Enterobacteriaceae family indicating that by removing oxygen from the gut the MV treatment shifts the Enterobacteriaceae population towards fermentation56. In agreement with this observation, we saw a decrease in the relative number of reads associated with cytochrome d oxidase with MV treatment. Cytochrome d oxidase is part of the bd family of oxidases preferentially expressed by Enterobacteriaceae during colitis52. This high affinity oxidase provides an energetic advantage allowing the cells to bloom during gut inflammation. A decrease in the transcription of cytochrome d suggests a reduction in Enterobacteriaceae respiration in MV-treated mice. Another notable observation is the decrease in the expression of succinate dehydrogenase in MV-treated mice. SDH is the enzyme the MVs rely upon to respire in the gut, and it is telling that the expression of this enzyme is suppressed in gut Enterobacteriaceae, apparently as a result of the anaerobiosis brought about by MVs.

We also performed a metabolome analysis, and the most notable change was in glyceric acid, whose levels were lower in the MV-treated group. Increases in glyceric acid has been reported in IBD studies and are thought to be a consequence of the release of TAGs associated with the colonic mucosa47,48. TAGs, the main source of energy for humans, are comprised of a glycerol conjugated to three fatty acyl chains and are synthesized ubiquitously by human cells57. TAGs can be metabolized into fatty acids and glycerol, which can be oxidized into glyceric acid58. Glycerols in the gut originate from either diet or the degradation of epithelial cells. Since diets are consistent between groups of mice, the increase in glyceric acid is likely a consequence of cell death and degradation of the colonic epithelium49. Indicating damage to the mucosal layer which provides a critical barrier between the microbiome and the host. An increase in mixed acid fermentation and butanediol fermentation, which cells use to compensate for acetate overflow46, indicate higher levels of acetate production by the microbiome with MV treatment. Acetate and other SCFAs have been shown to reduce inflammation and help restore gut integrity59,60. Taken together, these observations suggest that the MV treatment may help reduce both oxygen levels and mucosal degradation during gut inflammation.

This study provides proof-of-principle for bacterial membrane vesicles to deplete oxygen, restoring the environment of a healthy gut. One limitation of this study is that the membrane vesicles were not protected from degradation on their way to the colon. MVs were mixed in with food, which provides some protection. Formulating drugs in capsules for delivery to the colon, taking advantage of the higher pH of the human gut that dissolves the protective layer, is common practice. However, the pH of the mouse gut is acidic. In the future, a tailored formulation will be established for MV delivery. This will enable one to perform a dose-dependent study. It is reasonable to expect that an optimal dose of MVs will have a stronger effect on depleting oxygen and ameliorating symptoms of disease. Another limitation is the inflammation model used in this study. While the mouse Citrobacter infection model we used produces symptoms that are similar to human colitis, the infection does not resolve, and the animal ultimately succumbs to the disease. Examining MVs in additional models of inflammation such as DSS or in mice with a knockout in IL-10 will be necessary to better assess the promise of using MVs as a therapeutic particularly for chronic inflammation. Additionally observing the effects of the MVs on a healthy gut and ultimately in a human microbiome will better inform the prospects of MVs as a therapeutic to treat inflammation.

Naturally occurring membrane vesicles are commonly produced by Gram-negative bacteria. These vesicles which are heterogeneous in size (20-300 nm), are comprised of the outer membrane, and can encapsulate soluble periplasmic contents21,61. Outer-membrane vesicles (OMVs) are thought to benefit the bacteria by breaking down extracellular compounds into nutrients, recruiting iron and by sequestering antibiotics and bacteriophages. More recently Gram-positive bacteria have been shown to produce their own form of MVs called extracellular vesicles (EVs)62. Both OMVs and EVs have been found to promote or reduce inflammation largely based on the inflammatory profile of the producing bacteria61,63. The mechanisms behind the immunomodulatory effects of these MVs is still being researched, however, it seems likely that based on their size it is easier for MVs to access the intestinal epithelial layer where they encounter immune cells. If the MVs are from commensal bacteria, this would then lead to a reduced immune response, while the opposite would happen if the vesicles originated from immunogenic bacteria. Because of this, decorating MVs with immunomodulatory compounds may have an oversized effect on host health and the microbiome compared to whole cells.

Unlike our artificially produced MVs, the immunomodulatory effects of OMVs and EVs are not due to the respiration of oxygen. OMVs are comprised of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and they therefore do not contain the ETC, which is imbedded in the inner membrane. EVs shown to ameliorate inflammation have been from the Bifidobacterium genus, an anaerobic bacteria, which would not have an active ETC in its EVs. Therefore, we believe our experiments are the first example of the utilization of oxygen-reducing MVs to ameliorate colitis.

MVs represent a promising and novel approach to mitigate gut inflammation. MVs may benefit from being administered in combination with other treatments, such as anti-inflammatory 5-aminosalicylic acid, next-generation probiotics or fecal microbiota transplants, used to treat gut inflammation.

Methods

Membrane vesicle preparation

For wt MVs, ClearColiTM was grown in TSB without Glucose with 200 mM succinate and 1% NaCl at pH 7.5. Cells were harvested and concentrated by centrifugation at 10,000xg for 15 min and pellets were resuspended in 20 mM phosphate buffer with 650 mM succinate and 650 mM lactate at pH 8. Cells were then lysed by passing through a microfluidizer (Microfluidics LM10) at 15,000 PSI two times. Lysate was purified with tangential flow filtration through a 500 K Da PES hollow fiber. ΔhemB MVs were made by growing ΔhemB ClearColi in TSB + 1% NaCl + 0.4% glucose at pH 7.5 in anoxic conditions with constant N2 sparging and with an acid and base feed maintaining a neutral pH, all other steps were identical to wt MV preparation.

hemB Mutant

Deletion of hemB was first accomplished using lambda red recombineering64. In brief, a kanamycin resistance cassette (kanR) was amplified from plasmid pKD13 using primers P1 and P2, adding 50 bp of homology to each side of kanR. This construct was electroporated into E. coli MG1655 containing the lambda recombineering plasmid pKD46. Cells were recovered at 37 °C for 3 hours in SOC media and then plated on Luria Broth Miller (LB) + kanamycin (50 µg/ml) + 0.4% glucose. Small colony transformants were visible after ~48 hours of incubation at 37 °C. PCR with primers P3 and P4 was used to verify the swap of hemB with the KanR cassette. Deletion of hemB was further confirmed by Sanger Sequencing of the PCR product. The hemB::kanR was moved from E. coli MG1655 to E. coli ClearColi by P1 phage transduction and selection on LB + 25 mM citrate and 50 µg/ml kanamycin,1%NaCl,0.4%glucose. Successful transduction was confirmed with PCR and catalase test. Primers in supplemental (Table. S1).

Measuring O2 in vitro

Oxygen concentration was monitored using Oxygraph, a Clark type polarographic sensor (Hansatech Instruments). Oxygraph uses a platinum cathode and a silver anode connected through an electrolytic solution to quantitate O2 concentration of a solution in real-time. The Oxygraph was calibrated with aerated and fully reduced 20 mM potassium phosphate 650 mM succinate pH 7. MVs were thawed and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature, they were then diluted into 20 mM potassium phosphate 650 mM succinate pH 7 and oxygen concentration was measured under constant stirring.

Transmission electron microscopy

Wt and ∆hemB MVs were made as previously described. MVs were washed and resuspended in PBS. A carbon-coated grid was applied (carbon film-coated 200-mesh copper grid – Electron Microscopy Sciences) to a 10 μl drop of sample for a minute then excess sample was wicked off by touching it at a roughly 45° to a piece of filter paper. The grid is then rinsed 3 times by touching it to the surface of a drop of deionized water (wicking off the excess water after each rinse). This is followed by touching the grid to 2% uranyl acetate stain 4 times and wicking off the excess stain after each. After allowing the grid to dry completely it is viewed in a JEOL JEM 1010 TEM operated at 60 kV by William Fowle at the Boston Electron Microscopy Center.

Measuring Enterobacteriaceae growth with MVs in vitro

Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 43816, Citrobacter rodentium ATCC 51459, and Escherichia coli AR350, were grown overnight at 37 °C with aeration at 200 r.p.m. as a starter culture. This was then diluted 1/400 into LB with 13 mM succinate with and without wt MVs in aerated culture tubes aerated at 200 r.p.m. at 37 °C. MVs were added at a concentration of 1.623 mg/mL of protein. OD600 readings were taken after 7 hours with an Ultrospec 10 spectrometer. Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 43816, and Citrobacter rodentium ATCC 51459 were obtained from ATCC while Escherichia coli AR350 was obtained through the CDC.

Ulcerative colitis model

Animal studies were approved by the Northeastern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed at Northeastern University in accordance with institutional animal care and use policies. Five-week-old female C3H/HeNCrl mice were purchased from Charles River and cohoused under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with a 12-hour day/night cycle with temperature and humidity controls at ~21 °C and ~30%, respectively, and fed PicoLab IsoPro RMH 3000 irradiated mouse food. Mice were mixed, and weight-matched into new cages. Weight matching was done to avoid experimental differences between groups due to initial weight variance. After 48 hours of acclimation mice were fasted (to avoid the delivery of the inoculum into a full stomach, which could increase variability between animals and make it less likely that the inoculum is aspirated into the lungs) overnight then orally gavaged with 1.71×108 CFU/100 µl of Citrobacter rodentium ATCC 51459 resuspended in PBS. C. rodentium was grown overnight in aerated baffled flasks in LB shaking at 200 r.p.m. at 37 °C. MVs treatments were normalized to 10.151 mg/ml of protein, washed, and then resuspended in PBS and added to food at a 1:12 volume to weight. For MV treatments old food was removed and new treated food added every 24 hours.

Cytokine analysis

After euthanasia blood was collected from heart punctures and allowed to coagulate for 30 minutes at room temperature. It was then centrifuged at 2000x g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Serum was then collected and diluted 1:2 into PBS, immediately frozen and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Cytokines were quantitated at Eve Technologies using the Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine 32-Plex Discovery Assay® Array. ROUT outlier test, Q = 0.1% was applied to the data.

Colon hypoxia and histopathological analysis

To assess colonic hypoxia, mice were administered 60 mg/kg of pimonidazole HCl through intraperitoneal injection 1 hour before euthanasia. Colons were flushed with sterile PBS then sectioned longitudinally and rolled into Swiss rolls which were then stored in 10% formalin. Samples were imbedded, stained, and imaged at Applied Pathology systems as follows; tissue was imbedded in paraffin with a Leica ASP-300 Tissue Processor then sectioned to a thickness of 5 µm. Tissue was blocked with BloxALL and Animal Free Blocker/Diluent then then stained with the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 and Hypoxyprobe™-1 RED ATTO 594 a RED ATTO 594 dye-conjugated IgG1 mouse monoclonal antipimonidazoleantibody (clone 4.3.11.3). Slides were imaged with an Akoya PhenoImager Fusion and exposure times were optimized for 2 fluorescence filters (DAPI, Opal 620) and remained consistent across all images. For quantification 3 representative images of the distal colon were analyzed and the fluorescence of the colonic epithelium was quantified and averaged. Quantification was done using ImageJ with background subtraction, no adjusting for brightness was done. Histopathology was scored by Applied Pathology based on criteria from Erben et al. 65.

Metatranscriptomics

Stool was collected immediately after euthanasia and submerged in 500 µl of RNAprotect® then stored at -80 °C until processing. To extract and purify RNA, samples were spun down at 2,130 x g for 4 minutes at 4 °C and supernatant was removed. 600 µl of Qiagen RLT was added to the stool with 1% 2-Mercaptoethanol. This was transferred to MP lysing matrix E bead tubes and shaken at 6meters/second for 40 seconds twice using an MP FastPrep-24TM5G. Tubes were then centrifuged for 1 minute at 400xg and the supernatant was processed with the Qiagen RNeasy® Mini Kit following manufacture’s recommended protocol. Sequencing was done at Seqcenter, samples were DNAse treated with Invitrogen DNAse (RNAse free). Library preparation was performed using Illumina’s Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus kit and 10 bp unique dual indices (UDI). Sequencing was done on a NovaSeq X Plus, producing paired end 150 bp reads. Demultiplexing, quality control, and adapter trimming was performed with bclconvert (v4.1.5). Taxonomy was assigned with Kaiju and normalized to 5,958,789 features per sample. Phylogenetic tree was created with iTOL66. For functional analysis reads were normalized to 9,539,011 reads per sample. DIAMOND 2.1.8 was used to assign reads to proteins and MEGAN Community Edition (version 6.24.20, built 5 Feb 2023) was used to assign proteins to subcategories using the SEED database.

Metabolomics

After sacrifice, mouse stool was immediately weighed and frozen at −80 °C until needed. Methanol was added at a ratio of 40 µL/mg of stool in MP lysing matrix E bead tubes and shaken at 6 m/second for 40 seconds twice using an MP FastPrep-24TM5G. Tubes were then centrifuged for 1 minute at 400xg and 500 µL of supernatant was added to 1.5 mL of methanol in a glass vial. 4 mL of cold chloroform was added and the sample was vortexed for 1 minute before adding 2 mL of miliQ water and again vortexing for 1 minute. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3,000 r.c.f. The aqueous phase was then collected and analyzed by Harvard Center for Mass Spectrometry. All samples were dried under N2, resuspended in 0.9 μL/mg of 50% acetonitrile in water. Samples were run on a Thermo ID-X tribid mass spectrometer on a ThermoFisher ID-X mass spectrometer (Zic pHILIC column 150×2.1 mm 5 micron). LC method in supplemental (Table. S2). Data was median centered. Peak extraction, retention time alignment, gap filling, background subtraction, normalization, and compound identity determination were all performed by compound discoverer version 3.3.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tom Curtis for intellectual contributions to this project. Figure 4b was created using iTol and Figure 2a, was created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

N.P., K.L., and M.M. designed the experiments. N.P. and K.L. drafted the manuscript. N.P., R.B., M.G., and M.M. performed mouse experiments. M.G. and N.P. generated the ∆hemB ClearColi. N.P. performed in vitro experiments. N.P., M.K., and B.H. analyzed and interpreted data. All authors approved the final version.

Data Availability

European Nucleotide Archive with the primary accession code PRJEB80775.

Competing interests

K.L. and N.P. are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by Northeastern University: Provisional Patent Application No. 63/697942. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41522-025-00676-z.

References

- 1.Enck, P. et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.2, 16014 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roda, G. et al. Crohn’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers6. 10.1038/s41572-020-0156-2 (2020).

- 3.Kobayashi, T. et al. Ulcerative colitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers6. 10.1038/s41572-020-0205-x (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Heston, M. B. et al. Gut inflammation associated with age and Alzheimer’s disease pathology: a human cohort study. Sci. Rep. 13. 10.1038/s41598-023-45929-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sochocka, M. et al. The Gut Microbiome Alterations and Inflammation-Driven Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease-a Critical Review. Mol. Neurobiol.56, 1841–1851 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C. & Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.14, 576–590 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosco, N. & Noti, M. The aging gut microbiome and its impact on host immunity. Genes Immun.22, 289–303 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med.25, 1822–1832 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.12, 12 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsou, A. M. et al. Utilizing a reductionist model to study host-microbe interactions in intestinal inflammation. Microbiome. 9. 10.1186/s40168-021-01161-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Byndloss, M. X. et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma; signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science357, 570–575 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiga, L. et al. An Oxidative Central Metabolism Enables Salmonella to Utilize Microbiota-Derived Succinate. Cell Host Microbe22, 291–301.e296 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvak, Y., Byndloss, M. X. & Bäumler, A. J. Colonocyte metabolism shapes the gut microbiota. Science362, eaat9076 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd-Price, J. et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature569, 655–662 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rath, E. & Haller, D. Intestinal epithelial cell metabolism at the interface of microbial dysbiosis and tissue injury. Mucosal Immunol.15, 595–604 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winter, S. E. et al. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science339, 708–711 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes, E. R. et al. Microbial Respiration and Formate Oxidation as Metabolic Signatures of Inflammation-Associated Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe21, 208–219 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cevallos, S. A. et al. Increased Epithelial Oxygenation Links Colitis to an Expansion of Tumorigenic Bacteria. mBio10, e02244–02219 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, W. et al. Precision editing of the gut microbiota ameliorates colitis. Nature553, 208–211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pötgens, S. A. et al. Klebsiella oxytoca expands in cancer cachexia and acts as a gut pathobiont contributing to intestinal dysfunction. Sci. Rep.8. 10.1038/s41598-018-30569-5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Seike, K. et al. Ambient oxygen levels regulate intestinal dysbiosis and GVHD severity after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Immunity56, 353–368.e356 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mamat, U. et al. Detoxifying Escherichia coli for endotoxin-free production of recombinant proteins. Micro. Cell Fact.14, 57 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connors, J., Dawe, N. & Van Limbergen, J. The Role of Succinate in the Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation. Nutrients11, 25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouladoux, N., Harrison, O. J. & Belkaid, Y. The Mouse Model of Infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Curr. Protoc. Immunol.119, 19 15 11–19 15 25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng, L., Kelly, C. J. & Colgan, S. P. Physiologic hypoxia and oxygen homeostasis in the healthy intestine. A Review in the Theme: Cellular Responses to Hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol.309, C350–C360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullineaux-Sanders, C. et al. Citrobacter rodentium–host–microbiota interactions: immunity, bioenergetics and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.17, 701–715 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kany, S., Vollrath, J. T. & Relja, B. Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20. 10.3390/ijms20236008 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Friedrich, M., Pohin, M. & Powrie, F. Cytokine Networks in the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immunity50, 992–1006 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park, Y. E. et al. Microbial changes in stool, saliva, serum, and urine before and after anti-TNF-alpha therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Sci. Rep.12, 6359 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ullrich, K. A.-M. et al. IL-3 receptor signalling suppresses chronic intestinal inflammation by controlling mechanobiology and tissue egress of regulatory T cells. Gut72, 2081–2094 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzel, P., Ng, K. L. & Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun.7, 11257 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol.12, R60 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishihara, Y. et al. Mucosa-associated gut microbiota reflects clinical course of ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep.11, 13743 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monteros, M. J. M. et al. Probiotic lactobacilli as a promising strategy to ameliorate disorders associated with intestinal inflammation induced by a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Sci. Rep.11, 571 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macho Fernandez, E. et al. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut60, 1050–1059 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colautti, A., Orecchia, E., Comi, G. & Iacumin, L. Lactobacilli, a Weapon to Counteract Pathogens through the Inhibition of Their Virulence Factors. J. Bacteriol.204, e0027222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods12, 59–60 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huson, D. H., Auch, A. F., Qi, J. & Schuster, S. C. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 17, 377–386 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatsuya Akiyama, M. K. Bet-hedging: Bacterial ribosome dynamics during growth transitions. Curr. Biol.33, R1186–R1188 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa, M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.51, D587–D592 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Prot. Sci.28, 1947–1951 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knappe, J. & Sawers, G. A radical-chemical route to acetyl-CoA: the anaerobically induced pyruvate formate-lyase system of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev.6, 383–398 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crain, A. V. & Broderick, J. B. Pyruvate Formate-lyase and Its Activation by Pyruvate Formate-lyase Activating Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem.289, 5723–5729 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DP, S. R. C. Fermentative Pyruvate and Acetyl-Coenzyme A Metabolism. ecosalplus1. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.5.3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Meng, W. et al. 2,3-Butanediol synthesis from glucose supplies NADH for elimination of toxic acetate produced during overflow metabolism. Cell Disc.7. 10.1038/s41421-021-00273-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Santoru, M. L. et al. Cross sectional evaluation of the gut-microbiome metabolome axis in an Italian cohort of IBD patients. Scientific Reports7. 10.1038/s41598-017-10034-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Ponnusamy, K., Choi, J. N., Kim, J., Lee, S.-Y. & Lee, C. H. Microbial community and metabolomic comparison of irritable bowel syndrome faeces. J. Med. Microbiol.60, 817–827 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Weirdt, R. et al. Human faecal microbiota display variable patterns of glycerol metabolism. FEMS Microbiol Ecol.74, 601–611 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDaniel, L. E., Bailey, E. G. & Zimmerli, A. Effect of Oxygen Supply Rates on Growth of Escherichia Coli. Appl Microbiol13, 109–114 (1965). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma, A. K. et al. Effect of restricted dissolved oxygen on expression of Clostridium difficile toxin A subunit from E. coli. Sci. Rep.10, 3059 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez, C. A. et al. Virulence factors enhance Citrobacter rodentium expansion through aerobic respiration. Science353, 1249–1253 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crepin, V. F., Collins, J. W., Habibzay, M. & Frankel, G. Citrobacter rodentium mouse model of bacterial infection. Nat. Protoc.11, 1851–1876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abu-Ali, G. S. et al. Metatranscriptome of human faecal microbial communities in a cohort of adult men. Nat. Microbiol3, 356–366 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zotta, T., Parente, E. & Ricciardi, A. Aerobic metabolism in the genus Lactobacillus: impact on stress response and potential applications in the food industry. J. Appl Microbiol122, 857–869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolfe, A. J. Glycolysis for Microbiome Generation. Microbiol. Spectr.3. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0014-2014 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.McLelland, G. L. et al. Identification of an alternative triglyceride biosynthesis pathway. Nature621, 171–178 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grabner, G. F., Xie, H., Schweiger, M. & Zechner, R. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat. Metab.3, 1445–1465 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu, M. et al. Acetate attenuates inflammasome activation through GPR43-mediated Ca(2 + )-dependent NLRP3 ubiquitination. Exp. Mol. Med. 51, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deleu, S. et al. High Acetate Concentration Protects Intestinal Barrier and Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Organoid-Derived Epithelial Monolayer Cultures from Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24. 10.3390/ijms24010768 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Schwechheimer, C. & Kuehn, M. J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol13, 605–619 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dorward, D. W. & Garon, C. F. DNA Is Packaged within Membrane-Derived Vesicles of Gram-Negative but Not Gram-Positive Bacteria. Appl Environ. Microbiol56, 1960–1962 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mandelbaum, N. et al. Extracellular vesicles of the Gram-positive gut symbiont Bifidobacterium longum induce immune-modulatory, anti-inflammatory effects. NPJ Biofilms Microb.9, 30 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erben, U. et al. A guide to histomorphological evaluation of intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Int J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.7, 4557–4576 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 10.1093/nar/gkae268 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

European Nucleotide Archive with the primary accession code PRJEB80775.