Abstract

The continuous outbreak of various viruses reminds us to prepare broad-spectrum antiviral drugs. Human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (hDHODH) inhibitor exhibits broad-spectrum antiviral effects. In order to explore the novel type of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor (hDHODHi), we have optimized, designed, and synthesized 17 compounds and conducted biological activity evaluation, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics studies. The results of biological activity evaluation showed that compounds 10 and 16 exhibited submicromolar inhibitory activity, with IC50 values of 0.188 ± 0.004 and 0.593 ± 0.012 μM, respectively. Molecular docking studies showed that compounds 10 and 16 were in good agreement with the hDHODH activity pocket and interacted well with amino acid residues. Compared to the cocrystallized structure of the brequinar analogue complex, inhibitors 10 and 16 increased their direct interaction with Ala55. In addition, molecular dynamics studies showed that inhibitors 10 and 16 have strong affinity for proteins, and their complexes are stable, which confirms the significant inhibitory effect of inhibitors 10 and 16 on hDHODH in vitro. Through analysis, it was found that the carboxyl group and para introduced fluorine atoms in R1, as well as the naphthalene in R2, are key factors in improving activity. This conclusion provides help for further research into hDHODH inhibitors in the future. This study has promoted the significance of the development of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rampant outbreak of viruses has become increasingly frequent, seriously threatening global public health security and causing huge economic losses.1 At present, the World Health Organization has announced six international public health emergencies, namely, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic,2 the 2014 polio epidemic,3 the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa,4 the 2015–2016 Zika epidemic,5 the 2018 Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,6,7 and the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pneumonia pandemic at the end of 2019.8 In addition, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV), chikungunya virus (CHIKV), dengue virus (DENV), and other viruses have caused epidemic infections worldwide.9−12 The epidemics caused by these viruses remind us of the need to develop broad-spectrum antiviral drugs to cope with the sustained outbreaks of various viruses.

Antiviral drugs can be divided into two broad categories: direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) that directly act on the virus itself and host-targeting antiviral (HTA) drugs.13 Due to the virus specificity of DAA drugs, existing DAA drugs have limited or no therapeutic effects on emerging viruses, and it takes a long time to develop new DAA drugs. Therefore, antiviral drugs of targeting host factors have significant advantages in controlling the outbreak of new viruses.13 Viruses are parasitic organisms and rely on host replication. HTA drugs can not only effectively inhibit the rapid replication of viral nucleic acids but also combat viral resistance mutations. Therefore, the development of HTA drugs with broad-spectrum antiviral effects has always been a goal pursued in the field of new anti-infective drug development.13 Due to the unique structure of viruses, in order to replicate within host cells, it is necessary to utilize the raw materials and machinery of host cells for nucleic acid and protein production and processing.14 HTA drugs achieve antiviral effects by altering or eliminating the host materials necessary for virus replication. Research has found that human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (hDHODH) is one of the universal host factors necessary for the replication of many acutely infectious viruses.14,15 Inhibiting hDHODH can inhibit viral replication and thus play an antiviral role. Therefore, the research for hDHODH inhibitors has great clinical significance and application value.

HDHODH is a flavin-dependent mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the dehydrogenation of dihydroorotate (DHO) acid to orotate (ORO) and is a key enzyme in the fourth step of pyrimidine nucleotide de novo synthesis. HDHODH inhibitors block the de novo synthesis pathway of pyrimidine nucleotides, leading to the depletion of intracellular pyrimidine, which is an essential material for viral RNA/DNA replication. Therefore, hDHODH inhibitors exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral effects. Research has shown that hDHODH inhibitor leflunomide/A771726 has broad-spectrum antiviral activity, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), BK polyomavirus (BKV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Zika virus (ZIKV), Ebola virus (EBOV), dengue virus (DENV), etc.16−22

At present, the inhibitors targeting hDHODH mainly include brequinar, leflunomide, and A771726. A771726 is an active metabolite of leflunomide.23−32 When brequinar is administered in combination with cisplatin or cyclosporine A, it can cause adverse reactions such as leukopenia and thrombocytopenia as well as mucosal inflammation. Leflunomide is the only hDHODH inhibitor already on the market. However, long-term use of leflunomide can cause significant adverse reactions, such as diarrhea, hypertension, rash, and severe liver function damage. Therefore, the search for hDHODH inhibitors with novel structures, high activity, and low toxicity remains a hot research topic in the field of antiviral HTA drugs.

In the preliminary research, we used high-throughput screening to obtain a structurally novel thiazolidin-4-one hDHODH inhibitor 1. In this study, we optimized the structure of inhibitor 1 based on the amino acid characteristics around the binding pocket of hDHODH protein and synthesized a series of novel thiazolidin-4-one hDHODH inhibitors. Then, we evaluated the in vitro biological activity of the novel inhibitors, studied the structure–activity relationship of the inhibitors, and performed molecular docking on the inhibitors with better activity to investigate the mode of action between the inhibitors and proteins. Finally, we studied the binding ability between the inhibitors with better activity and proteins through molecular dynamics (MD) and finally obtained a novel thiazolidin-4-one hDHODH inhibitor with novel structure, better activity, and higher binding energy. The discovery of this type of inhibitor may be of great significance for newly emerging viruses or viruses that may appear in the future and also lays the foundation for the development of broad-spectrum antiviral HTA drugs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure–Activity Relationship

Through preliminary screening, we obtained hDHODH inhibitor 1, which is shown in Table 1. In this study, inhibitor 1 was used as a lead compound for structural optimization, mainly to optimize R1 and R2 parts. The optimized compounds and analytical spectra are shown in Table S1. The optimized inhibitor was tested for in vitro activity, and the results are shown in Table 1. The raw test data are provided in Table S2.

Table 1. Chemical Structures and In Vitro Activity Evaluation of hDHODH Inhibitors.

The optimization of R1 mainly involves the introduction of different functional groups on the benzene ring. First, we introduced a fluorine atom and a chlorine atom in the para-position. When the structure of R2 was the same, we found that the activity of introducing the fluorine atom was higher than that of introducing the chlorine atom. Inhibitors 2–11 can basically explain this viewpoint, with inhibitor 10 having the best activity and IC50 value of 0.188 ± 0.004 μM. When the position of the fluorine atom was changed from the para to meta position, compound 12 was obtained, which has lower activity. Simultaneous introduction of fluorine atoms in both para and ortho positions gave compound 13, which has lower activity. This indicated that the position of introduction of the fluorine atom was optimal in the para-position, and introduction of one fluorine atom was better than introduction of two fluorine atoms. When methoxy groups were introduced in the para and meta positions respectively, compounds 14 and 15 were obtained. From the activity test results, it can be seen that the para-position was better than the meta position, but the activity was lower than when the fluorine atom was introduced. When methyl groups were introduced in the para and meta positions, respectively, compounds 16 and 17 were obtained. Compound 16 exhibited high activity with an IC50 value of 0.593 ± 0.012 μM, while the activity of compound 17 sharply decreased. This also indicated that introducing functional groups in the para-position was superior to the introduction of functional groups in the meta position.

On the basis of compound 1, methoxy groups were first introduced at the para-position of R2 to obtain compounds 4 and 5, whose activity was similar to that of compounds 2 and 3. When methoxy groups were introduced simultaneously in the para and meta positions, compounds 8 and 9 were obtained. The activity of compounds 8 and 9 was significantly lower than that of compounds 4 and 5, indicating that introducing groups only in the para-position was better than introducing groups simultaneously in the para and meta positions. When trifluoromethyl was introduced in the para-position, compounds 6 and 7 were obtained and their activity was similar to that of compounds 2 and 3. Compounds 8–17 all directly replaced the R2 portion with naphthalene, with compounds 10 and 16 showing significant activity enhancement, both reaching submicromolar levels, especially compound 10, which was similar to the positive control A771726, indicating that the R2 portion was more suitable for larger hydrophobic groups.

In summary, the introduction of a fluorine atom on the benzene ring of R1 was superior to the introduction of other functional groups, and the fluorine atom was in the optimal position in para-position. This indicated that the benzene ring of R1 was more suitable for the introduction of hydrophobic groups with smaller structures, which may be related to the spatial position of the binding pocket. After the R2 part was replaced with naphthalene, the activity was significantly improved, indicating that the introduction of hydrophobic groups with larger structures in the R2 part was superior to the introduction of other groups. Simultaneous optimization of R1 and R2 to the optimal level can significantly enhance the inhibitor activity. The structure–activity relationship diagrams of the inhibitors are shown in Figure S1.

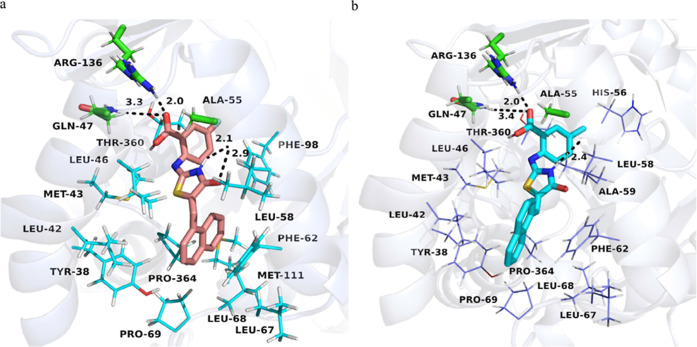

2.2. Molecular Docking

To better understand the mode of action between inhibitors and proteins, molecular docking was performed on all compounds. Figure 1 shows the binding patterns of inhibitors 10 and 16 to proteins. In Figure 1A, the carboxyl group of R1 directly forms hydrogen bonds with Arg136 and Gln47, while the oxygen and nitrogen atoms on the connecting arm directly form hydrogen bonds with Ala55, allowing the inhibitor to bind to the protein. Meanwhile, the naphthalene of R2 forms strong hydrophobic interactions with Tyr38, Leu42, Phe62, Leu67, Leu68, Pro69, Met111, and Pro364, further enhancing the activity of inhibitor 10. In Figure 1B, there is a slight change in the spatial position of inhibitor 16. The carboxyl group of R1 forms hydrogen bonds with Arg136 and Gln47, while only the nitrogen atom on the connecting arm forms hydrogen bonds with Ala55. Due to the change in the spatial position, the hydrophobic interaction formed by the naphthalene of R2 is also slightly weaker. This may be the reason why inhibitor 16 has slightly lower activity than inhibitor 10. However, compared to the cocrystallized structure of the brequinar analogue complex (Figure S2), inhibitors 10 and 16 increased their direct interaction with Ala55.

Figure 1.

Picture “a” shows the binding modes of compound 10 with hDHODH. HDHODH (PDB ID: 1D3G) is shown as a transparent blue-white cartoon. The critical residues are presented as cyan lines. Arg136, Gln47, and Ala55 are displayed as green sticks. Compound 10 is colored salmon. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. Picture “b” shows the binding modes of compound 16 with hDHODH. HDHODH (PDB ID: 1D3G) is shown as a transparent blue-white cartoon. The critical residues are presented as slate lines. Arg136, Gln47, and Ala55 are displayed as green sticks. Compound 2 is colored cyan. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. We used PyMOL to analyze protein–ligand interactions and visualize the binding modes.

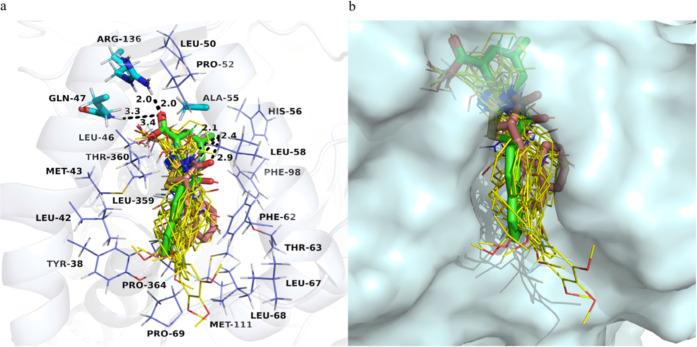

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the binding modes of inhibitors 10 and 16 with those of other inhibitors. From the figure, it can be seen that inhibitors 10 and 16 have a higher degree of coincidence with the protein binding pocket, especially the naphthalene ring in the R2 part, which can better fill the spatial position of the binding pocket while generating stronger hydrophobic interactions. Due to the pushing effect of the naphthalene ring in the R2 part, the binding position of the inhibitor moves deeper into the binding pocket. This movement allows the R1 group to interact better with the surrounding amino acids, and the connecting arm also interacts directly with the surrounding amino acids. This may be an important factor in enhancing the activity of inhibitors 10 and 16.

Figure 2.

Picture “a” shows the binding modes of all compounds with hDHODH. HDHODH (PDB ID: 1D3G) is shown as a transparent blue-white cartoon. The critical residues are presented as slate lines. Arg136, Gln47, and Ala55 are displayed as cyan sticks. Compound 10 is colored salmon. Compound 16 is colored green. Other compounds are colored yellow. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. Picture “b” shows the binding modes of all compounds with hDHODH. HDHODH (PDB ID: 1D3G) is shown as a transparent pale cyan surface. Compound 10 is colored salmon. Compound 16 is colored green. Other compounds are colored yellow. We used PyMOL to analyze protein–ligand interactions and visualize the binding modes.

In summary, the hydrophilic end of the inhibitor was located deep in the binding pocket, and the hydrophobic end was located at the entrance of the binding pocket. The carboxyl group of R1 was the focus of the interaction between the inhibitors and proteins. The introduction of the fluorine atom of R1 enabled better interaction between inhibitors and proteins, and the introduction of the fluorine atom was the key to enhancing the activity of inhibitors. The design of R2 naphthalene enabled inhibitors to have stronger hydrophobic interactions with surrounding amino acids while pushing the inhibitor inward, allowing the entire inhibitor to better interact with binding sites. R2 naphthalene was also the key to enhancing the inhibitor activity.

2.3. Molecular Dynamics

In order to further investigate the binding ability of inhibitors to proteins, we selected compounds 10 and 16 with the highest experimental activities for MD studies.

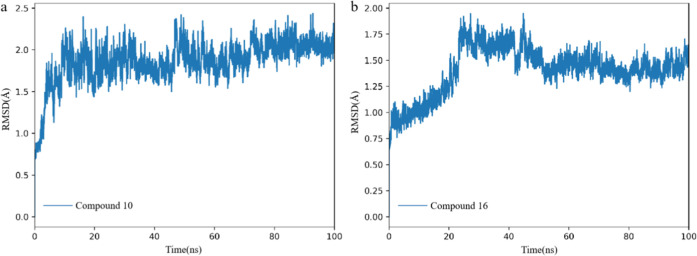

2.3.1. Root Mean Square Deviation

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis is a commonly used metric in MD simulations to measure the structural stability of a protein over time. By calculating the RMSD, we can assess how much the protein structure deviates from its initial conformation, which gives insights into the protein’s stability, flexibility, and conformational changes throughout the simulation. From Figure 3, we can see that after approximately 30 ns, the RMSD curve reaches a plateau, indicating that the protein structure has reached a stable state during the simulation process. The averages of RMSD for hDHODH bound to compound 10 and compound 16 are 1.87 and 1.40 Å (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Time evolution RMSD of the protein C-α atom over 100 ns for hDHODH bound to compound 10 (a) and compound 16 (b).

Table 2. RMSD, RMSF, and SASA Profile of hDHODH Bound to Compound 10 and Compound 16a.

| compound | RMSD | RMSF | SASA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1.87 | 0.72 | 16106.75 |

| 16 | 1.40 | 0.73 | 16031.35 |

Values are represented as estimated averages and expressed by Å.

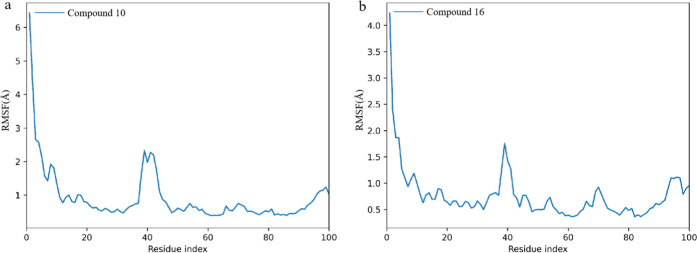

2.3.2. Root Mean Square Fluctuations

Root mean square fluctuations (RMSFs) provide valuable insight into the flexibility of different regions within a protein by measuring the average deviation of each residue or atom from its mean position over the course of an MD simulation. RMSF analysis is particularly useful for identifying flexible or mobile regions, such as loops or binding sites, as well as stabilizing elements, such as helices and sheets. From Figure 4, we can see that the two compounds form complexes with the protein, and that the overall movement trend of the protein is similar. A small area on the protein undergoes more intense movement changes, such as the movement of residues 180–190 on the 16 complex protein being more intense than that on the 10 complex. The averages of RMSF for hDHODH bound to compound 10 and compound 16 are 0.72 Å and 0.73 Å (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Time evolution RMSF of each residue of the protein C-α atom over 100 ns for hDHODH bound to compound 10 (a) and compound 16 (b).

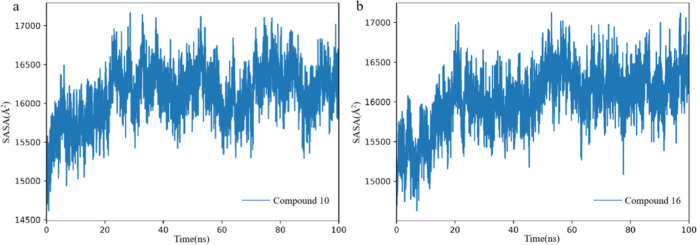

2.3.3. Solvent Accessible Surface Area

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) is a metric used in MD and structural biology to quantify the surface area of a protein that is accessible to solvent molecules, usually water. SASA analysis provides insight into protein folding, stability, binding interactions, and conformational changes over time. From Figure 5, it can be seen that after approximately 30 ns, the SASA curve reaches a plateau and remains stable. The protein structure remained stable thereafter, which is consistent with the results of RMSD. The averages of SASA for hDHODH bound to compound 10 and compound 16 are 16106.75 Å and 16031.35 Å (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Structural representation of alterations occurring during the binding of compound 10 (a) and compound 16 (b), solvent accessible surface area of hDHODH.

2.3.4. Binding Free Energy

The MM/GBSA method is a popular approach to estimate the binding free energy between a protein and ligand. It combines molecular mechanics energy calculations with solvation models to approximate binding affinities, making it both computationally efficient and reasonably accurate for various protein–ligand systems. A negative binding free energy (ΔG) indicates favorable binding; the more negative, the stronger the binding affinity. From the calculation of binding free energy (Table 3), it can be seen that compound 10 has a lower binding energy than compound 16, indicating that compound 10 has a stronger binding affinity with proteins, which also demonstrates that compound 10 has better inhibitory activity. Compared with the binding free energy of brequinar (ΔG = −49.18), compound 16 has a slightly higher ΔG, while compound 10 has a lower ΔG, which further confirms the strong binding affinity of compounds 10 and 16 with the hDHODH protein.

Table 3. Binding Free Energies (kcal/mol) of hDHODH with Compounds 10 and 16ab.

| compound | ΔEELE | ΔEVDW | ΔEGBSUR | ΔEGB | ΔG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | –244.52 | –55.82 | –4.31 | 248.25 | –56.39 |

| 16 | –221.21 | –53.82 | –4.73 | 231.58 | –48.18 |

All energy components are expressed as kcal/mol.

ΔEELE = electrostatic energy; ΔEVDW = van der Waals; ΔEGBSUR = nonpolar solvation free energy; ΔEGB = polar solvation free energy; ΔG = binding free energy.

3. Conclusions

HDHODH inhibitors were initially developed to treat autoimmune diseases and are now increasingly being explored for their potential in antiviral therapy. Their antiviral mechanisms primarily include effectively reducing the pyrimidine sources necessary for viral replication, stimulating the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), and inhibiting virus-induced cytokine storms. While the use of hDHODH inhibitors alone has shown certain limitations in clinical applications, combining them with other DAA drugs has demonstrated enhanced antiviral efficacy. Examples of such combinations include teriflunomide with ribavirin,33 brequinar with molnupiravir,34 and S312 with oseltamivir.14 This improved efficacy is attributed to the different mechanisms of action between HTA and DAA drugs. Synergistic therapy with these drugs can target multiple steps and factors in the viral life cycle, thereby enhancing the overall antiviral activity. HDHODH inhibitors have shown effectiveness against a wide range of viruses and their variants regardless of whether mutations occur. When used in combination with DAA drugs, they can expand the spectrum of targeted viruses, ultimately achieving broad-spectrum antiviral effects. However, existing hDHODH inhibitors have shown varying degrees of adverse reactions in clinical applications. Therefore, the development of new hDHODH inhibitors is of great significance for advancing the field of broad-spectrum HTA drugs.

In the preliminary research, we used high-throughput screening to obtain a structurally novel thiazolidin-4-one hDHODH inhibitor 1. In this study, we optimized the structure of inhibitor 1 and synthesized a series of novel thiazolidin-4-one hDHODH inhibitors. We then conducted in vitro activity testing, molecular docking, and MD simulations of the novel inhibitors. It was found that compounds 10 and 16 exhibited good activity, with IC50 values of 0.188 ± 0.004 and 0.593 ± 0.012 μM, respectively. In the optimization process, we first maintained the carboxyl structure of R1 unchanged and then introduced fluorine, chlorine, methyl, and methoxy groups on the benzene ring for comparison. We found that the introduction of fluorine was the most suitable. We compared the position of the introduction between the meta- and para-positions and found that the para-position was better. We also compared the number of introduced groups and found that introducing one group was the best. The above results indicated that it was most suitable for R1 to introduce a smaller functional group in the para-position while maintaining the carboxyl group, which may be related to the spatial position of the binding pocket and the structural properties of the surrounding amino acids. The structural optimization of R2 first involved the introduction of methoxy and trifluoromethyl groups on the benzene ring. It was found that there was no significant improvement in activity; especially when three methoxy groups were introduced simultaneously, the activity decreased significantly. This indicated that the optimization strategy of directly introducing functional groups onto the benzene ring was not appropriate. Based on the spatial position of the pocket, R2 was more suitable for introducing larger functional groups. Therefore, we directly replaced the benzene ring with naphthalene. After the replacement, we were surprised to find that the activity increased sharply. This indicated that our optimization strategy was reasonable, and we have obtained the optimal compound 10, which has activity similar to that of positive control A771726. According to the analysis of binding patterns, we found that naphthalene could better occupy spatial positions while also generating stronger interactions with surrounding amino acids. It also promoted the inhibitor to move deeper into the binding pocket, promoted the interaction between the connecting arm and surrounding amino acids, and further enhanced the interaction between R1 and surrounding amino acids. Compared to the cocrystallized structure of the brequinar analogue complex, inhibitors 10 and 16 increased their direct interaction with Ala55. In order to better explore the interaction between inhibitors and proteins, we selected the most active compounds, 10 and 16, for MD simulation. Through dynamics simulation analysis, we found that inhibitors 10 and 16 have strong affinity for proteins, and their complexes are stable. This also confirms the significant inhibitory effect of inhibitors 10 and 16 on hDHODH in vitro. Through optimization, we have concluded that the carboxyl group of R1 and the fluorine atom introduced in the para-position, as well as the naphthalene of R2, were key factors in enhancing activity. This conclusion may provide important support for the continued development of hDHODH inhibitors in the future. In further research, it may be possible to consider further optimizing the connecting arms to enhance the activity and interaction. We hope to find hDHODH inhibitors with high activity, good targeting, low side effects, and good medicinal properties to provide assistance for the development of HTA drugs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The hDHODH plasmid was obtained from prelaboratory preservation. pET-19b vector, E. coli BL21 (DE3), and E. coli DH5α were purchased from Novagen company. T4 DNA ligase (M1801), Taq enzyme (M7122), restriction endonuclease BamHI (R6021), restriction endonuclease NdeI (R6801), protein marker (V5235S), and DNA marker (G1741) were purchased from Promega company. Plasmid extraction kit (A1330) was purchased from the Axygen company. The microplate reader, protein electrophoresis analyzer, high-pressure cell breaker, gel imaging system, nucleic acid electrophoresis analyzer, etc. were purchased from Bio-Rad, and Ni-NTA was purchased from Bioengineering Co., Ltd.

4.2. Chemistry

All compounds were synthesized by Chongqing, (Changshou) Green Chemical and New Materials Industry Technology Research Institute. The structures of the synthesized compounds were determined by methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance, and their purity was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography.

4.3. Construction of the pET-19b-hDHODH Plasmid

Primer design and synthesis were based on the hDHODH gene sequence. The synthesized DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification, followed by amplification with nucleic acid electrophoresis and gel recovery. The pET-19b vector was digested using NdeI and BamHI, and the PCR product was also digested using the same restriction endonucleases. After digestion, the product was recovered. The recovered product was coupled with T4 DNA ligase, transferred to the competent cell E. coli DH5α, and finally identified and sequenced. The sequencing was correct, indicating that the pET-19b-hDHODH plasmid had been constructed.

4.4. Protein Expression

The constructed pET-19b-hDHODH plasmid was transferred into the expression strain E. coli BL21(DE3) and cultured on solid medium at 37 °C. After the monoclonal colony was produced, it was transferred to liquid medium for cultivation at 37 °C and 220 r/min. When the OD600 was about 0.6, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to reach a final concentration of 0.5 mmol/L, and cultivation was continued overnight. The cultured bacterial solution was identified by protein gel electrophoresis, and mass production was carried out after confirmation of the expression.

4.5. Protein Purification

We dissolved the cultured bacteria in a buffer solution consisting of 400 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L HEPES, 10 mmol/L imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and pH 7.0 and then crushed the dissolved bacteria using a high-pressure cell crusher to dissolve the protein in the buffer solution. After crushing, we performed high-speed centrifugation and collected the supernatant after centrifugation. The supernatant was slowly passed through the processed Ni-NTA column to allow the protein to fully bind to the column. After the completion of binding, the impurities were washed off with wash buffer. Depending on the situation of the impurities, multiple washings can be carried out. The washing solution increased the concentration of imidazole on the basis of the buffer. After the washing of the impurities was completed, the liquid should be changed, mainly by changing 0.1% Triton X-100 to 10 mmol/L UDAO, while leaving the other components unchanged. Finally, the target protein was eluted, and the elution buffer consisted of 400 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol HEPES, 500 mmol/L imidazole, 10 mmol/L UDAO, 10% glycerol, and pH 7.0. After elution, the target protein was packaged and stored for subsequent experiments. The entire purification process was completed in a low-temperature environment.

4.6. Biological Activity Evaluation

We diluted the hDHODH protein to a final concentration of 10 nM using an activity test solution. The components of the activity test solution were 150 mM KCl, 50 mM HEPES, 0.1% Triton X-100, and pH 8.0. After dilution, a final concentration of 100 μM CoQ and a final concentration of 120 μM DCIP were added and mixed well. The hDHODH inhibitor was dissolved in DMSO. The 199 μL mixture was transferred into the 96-well plate, and different concentrations of inhibitors were added. We waited for the reaction for 5 min at room temperature and then added the substrate DHO to achieve a final concentration of 500 μM. The 96-well plate was placed in the microplate reader and a wavelength of 600 nm was selected for reading. The inhibition rate of the compound was calculated using the formula (1-Vi/V0)*100%. The IC50 value of the compound was calculated using Origin 8.0 based on the inhibition rates of different concentrations. During the testing process, A771726 and brequinar were used as positive controls, and parallel measurements were conducted three times.

4.7. Molecular Docking

We downloaded the crystal structure 1D3G24 of the hDHODH complex from the PDB database, removed water molecules and other ligand molecules, and used it as a docking template. We drew the three-dimensional structure of the inhibitor using Chem3D and then converted it to mol2 format using Open Babel for backup. The AutoDock was used for molecular docking, which opened macromolecular proteins to perform hydrogenation and charge calculations, and finally, it was saved in PDBQT format. The small molecules were imported and then processed using ligand and were saved in PDBQT format. The large molecule proteins and small molecule ligand were opened in the Grid and we set the parameters for an AutoGrid run, with all Grid parameters set by default. The macromolecular proteins and small molecule ligands were opened in docking, and the genetic algorithm was selected to run AutoDock; all docking parameters were set by default. After the docking was completed, the docking results were opened for analysis, and the conformation with the lowest binding energy was selected for binding mode analysis. Simultaneously verify through redocking.

4.8. Molecular Dynamics

MD simulation of the modeled protein complex was performed by AMBER22 software.25 Protein and compound were parameterized with the AMBER ff14SB force field26 and the general AMBER force field (gaff),27 respectively. The complex system was solvated with the TIP3P28 water model with a distance of 10 Å between the solute and box. Counter-ions (Na+ or Cl–) were added to neutralize the solvated system. The solvated system was minimized by the gradient descent algorithm. After minimizations, the system was gradually heated from 0 to 300 K in the NVT (T = 300 K) ensemble over a period of 500 ps and then relaxed in the NPT ensemble (T = 300 K and P = 1 atm). SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain the bonds involving hydrogen atoms. The cutoff value of 10 Å was set to calculate the short-range interactions. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm was used to calculate the long-range electrostatic interactions. The time step was set to 2 fs, and the snapshots were recorded every 20 ps. A 100 ns production simulation was performed. RMSD, RMSF, and SASA analyses were conducted by the CPPTRAJ module implemented in AMBER software. 50 structural snapshots extracted from the equilibrated trajectory were used for binding free energy calculation by the MM/GBSA method29 implemented in AMBER software.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who contributed directly or indirectly to the work.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c11459.

Structure–activity relationship of all inhibitors; co-crystallized structure of the brequinar analogue complex; chemical structures and its analytical spectra of the hDHODH inhibitor; and raw data for in vitro activity testing of all hDHODH inhibitors (PDF)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), and X.L. (Xiangbi Li); methodology: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoping Ren), and M.H.; validation: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), and C.S.; formal analysis, X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), J.Z., S.R., and Z.L.; investigation: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), F.L., S.R., and X.L. (Xiangbi Li); resources: L.C. and J.Y.; data curation: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), and X.L. (Xiangbi Li); writing—original draft preparation: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), and X.R. (Xiaoping Ren); writing—review and editing: X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu), X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), J.Z., and M.H.; supervision: X.R. (Xiaoli Ren), X.L. (Xiangbi Li), and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Youth Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (Nos. KJQN202304510, KJQN202304506, KJQN202204506, and KJQN202304504) and Key Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Chemical Industry Vocational College of China (No. HZY2024-KJZD03).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gao G. F. From “A” IV to “Z” IKV: Attacks from Emerging and Re-emerging Pathogens. Cell 2018, 172 (6), 1157–1159. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO , H1N1 IHR Emergency Committee, 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/h1n1-ihr-emergency-committee.

- WHO , Poliovirus IHR Emergency Committee, 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/poliovirus-ihr-emergencycommittee.

- WHO , Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa (2014–2015) IHR Emergency Committee, 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/ebola-virus-disease-in-west-africa-(2014-2015)-ihr-emergency-committee.

- WHO , Zika Virus IHR Emergency Committee, 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/zika-virus-ihr-emergencycommittee.

- WHO , Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Equateur) IHR Emergency Committee, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/ebola-virus-disease-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-equateur-ihr-emergencycommittee.

- WHO , Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kivu and Ituri) IHR Emergency Committee, 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/ebola-virus-disease-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-kivu-and-ituri-ihremergency-committee.

- WHO , COVID-19 IHR Emergency Committee, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/covid-19-ihr-emergencycommittee.

- WHO , Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003, 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/summary-of-probable-sars-cases-with-onset-of-illness-from-1-november-2002-to-31-july-2003.

- WHO , MERS-CoV IHR Emergency Committee, 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/mers-cov-ihr-emergencycommittee.

- Guzma M. G.; Harris E. Dengue. Lancet 2015, 385 (9966), 453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt F. J.; Chen W.; Miner J. J.; Lenschow D. J.; Merits A.; Schnettler E.; Kohl A.; Rudd P. A.; Taylor A.; Herrero L. J.; Zaid A.; Ng L. F. P.; Mahalingam S. Chikungunya virus: An update on the biology and pathogenesis of this emerging pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17 (4), e107–e117. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dalja A.; Inglesby T. Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agents: A Crucial Pandemic Tool. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019, 17 (7), 467–470. 10.1080/14787210.2019.1635009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong R.; Zhang L. K.; Li S. L.; Sun Y.; Ding M. Y.; Wang Y.; Zhao Y. L.; Wu Y.; Shang W. J.; Jiang X. M.; Shan J. W.; Shen Z. H.; Tong Y.; Xu L. X.; Chen Y.; Liu Y. L.; Zou G.; Lavillete D.; Zhao Z. J.; Wang R.; Zhu L. L.; Xiao G. F.; Lan K.; Li H. L.; Xu K. Novel and potent inhibitors targeting DHODH are broad-spectrum antivirals against RNA viruses including newly-emerged coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Protein Cell 2020, 11 (10), 723–739. 10.1007/s13238-020-00768-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luganini A.; Boschi D.; Lolli M. L.; Gribaudo G. DHODH inhibitors: What will it take to get them into the clinic as antivirals?. Antiviral Res. 2025, 236, 106099–106119. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2025.106099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luganini A.; Sibille G.; Mognetti B.; Sainas S.; Pippione A. C.; Giorgis M.; Boschi D.; Lolli M. L.; Gribaudo G. Effective deploying of a novel DHODH inhibitor against herpes simplex type 1 and type 2 replication. Antiviral Res. 2021, 189, 105057–67. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordsmeier A.; Herrmann A.; Gege C.; Kohlhof H.; Korn K.; Ensser A. Molecular analysis of the 2022 mpox outbreak and antiviral activity of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors against orthopoxviruses. Antiviral Res. 2025, 233, 106043–106053. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.106043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. S.; Chen K. L.; Chu S. W. Human/SARS-CoV-2 genome-scale metabolic modeling to discover potential antiviral targets for COVID-19. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2022, 133, 104273–104284. 10.1016/j.jtice.2022.104273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. M.; Zhao Y.; Hu W. H.; Zhao D.; Zhang Y. T.; Wang T.; Zheng Z. S.; Li X. C.; Zeng S. L.; Liu Z. L.; Lu L.; Wan Z. H.; Hu K. Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients With Prolonged Postsymptomatic Viral Shedding With Leflunomide: A Single-center Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73 (11), e4012–e4019. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann K. M.; Dickmanns A.; Heinen N.; Blaurock C.; Karrasch T.; Breithaupt A.; Klopfleisch R.; Uhlig N.; Eberlein V.; Issmail L.; Herrmann S. T.; Schreieck A.; Peelen E.; Kohlhof H.; Sadeghi B.; Riek A.; Speakman J. R.; Groß U.; Görlich D.; Vitt D.; Müller T.; Grunwald T.; Pfaender S.; Balkema-Buschmann A.; Dobbelstein M. Inhibitors of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase cooperate with molnupiravir and N4-hydroxycytidine to suppress SARS-CoV-2 replication. Science 2022, 25 (5), 104293–104318. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M. L.; Yang Y. Q.; Huang Y.; Gan T. Y.; Wu Y.; Gao H. Y.; Li Q. Q.; Nie J. H.; Huang W. J.; Wang Y. C.; Zhang R.; Zhong J.; Deng F.; Rao Y.; Ding Q. Novel quinolone derivatives targeting human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase suppress Ebola virus infection in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2021, 194, 105161–105171. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrell L.; Fuchs H. l.; Dickmanns A.; Scheibner D.; Olejnik J.; Hume A. J.; Reineking W.; Störk T.; Müller M.; Graaf-Rau A.; Diederich S.; Finke S.; Baumgärtner W.; Mühlberger E.; Balkema-Buschmann A.; Dobbelstein M. Inhibitors of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase synergize with the broad antiviral activity of 4’-fluorouridine. Antiviral Res. 2025, 233, 106046–106068. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.106046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins W. T.; Vibhute S.; Bennett C.; Lindert S. Discovery of Nanomolar Inhibitors for Human Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Using Structure-Based Drug Discovery Methods. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64 (2), 435–448. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Takeda M.; Imahatakenaka M.; Ikeda M. Identification of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor, vidofludimus, as a potent and novel inhibitor for influenza virus. J Med Virol 2024, 96 (1), e29372–e29382. 10.1002/jmv.29372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S.; Ma H.; Xu Z.; Fang W.; Huang J.; Huang Y. Tiratricol, a thyroid hormone metabolite, has potent inhibitory activity against human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 102 (1), 1–13. 10.1111/cbdd.14256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexauer A. N.; Alexe G.; Gustafsson K.; Zanetakos E.; Milosevic J.; Ayres M.; Gandhi V.; Pikman Y.; Stegmaier K.; Sykes D. B. DHODH: a promising target in the treatment of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv 2023, 7 (21), 6685–6701. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Neidhardt E. A.; Grossman T. H.; Ocain T.; Clardy J. Structures of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in complex with antiproliferative agents. Structure 2000, 8 (1), 25–33. 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case D. A.; Cheatham T. E.; Darden T.; Gohlke H.; Luo R.; Merz K. M.; Onufriev A.; Simmerling C.; Wang B.; Woods R. J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26 (16), 1668–1688. 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier J. A.; Martinez C.; Kasavajhala K.; Wickstrom L.; Hauser K. E.; Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11 (8), 3696–3713. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wolf R. M.; Caldwell J. W.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25 (9), 1157–1174. 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D. J.; Brooks C. L. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121 (20), 10096–10103. 10.1063/1.1808117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E.; Sun H.; Wang J.; Wang Z.; Liu H.; Zhang J. Z. H.; Hou T. End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and Applications in Drug Design. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (16), 9478–9508. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda C. S.; García C. C.; Damonte E. B. Antiviral activity of A771726, the active metabolite of leflunomide, against Junín virus. J Med Virol 2018, 90 (5), 819–827. 10.1002/jmv.25024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D. C.; Johnson R. M.; Ayyanathan K.; Miller J.; Whig K.; Kamalia B.; Dittmar M.; Weston S.; Hammond H. L.; Dillen C.; Ardanuy J.; Taylor L.; Lee J. S.; Li M.; Lee E.; Shoffler C.; Petucci C.; Constant S.; Ferrer M.; Thaiss C. A.; Frieman M. B.; Cherry S. Pyrimidine inhibitors synergize with nucleoside analogues to block SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2022, 604 (7904), 134–140. 10.1038/s41586-022-04482-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.