Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to elucidate the reliability of clinical impressions based on ocular manifestations in patients suspected of heritable connective tissue disorders (HCTDs) compared to the final genetic diagnosis. Furthermore, it sought to determine the optimal diagnostic strategy for patients with HCTDs through pathogenicity analysis.

Methods

Clinical characteristics of 58 patients suspected of HCTDs were analyzed to establish provisional clinical diagnoses. Subsequently, next-generation sequence and Sanger sequence was performed to obtain genetic diagnoses. Pathogenicity of identified variants was assessed through conservation analysis and the functional impact, which was predicted using three-dimensional protein structure modeling.

Results

The provisional clinical diagnosis was concordant with the molecular diagnostic result in only 21 patients. Independent of the initial clinical impression, a probable genetic diagnosis was achieved for all 58 patients following comprehensive re-analysis of next-generation sequence data, combined with pathogenicity assessment using three-dimensional protein structure and conservation analysis of suspicious positive variants.

Conclusion

This study broadens the mutational spectrum of HCTDs with 31 novel variants. By employing innovative methodologies to delineate phenotype–genotype relationships, including the detection of potentially pathogenic variants, this work may inform future diagnostic strategies and guide comprehensive disease and organ system monitoring. Ongoing refinement and vigilant clinical oversight remain essential for patients and their families.

Keywords: Heritable connective tissue disorders, Genetic diagnosis, Stickler syndrome, Knobloch syndrome, Wagner syndrome, Severe myopia

Introduction

Heritable connective tissue diseases (HCTDs) represent a heterogeneous group of multisystem disorders primarily characterized by defects in the synthesis of proteins that constitute the structural framework of connective tissues [1]. Consequently, their accurate diagnosis and effective management often necessitate an interdisciplinary approach [2]. Furthermore, specific heritable conditions affecting the production of extracellular matrix (ECM) components [3, 4], resulting in collagen, elastin, fibrillin, fibulin, and mucopolysaccharides abnormalities, impacting multiple organ systems such as the musculoskeletal, ocular, vascular, dermatological, and renal systems [5, 6]. Ocular involvement such as Marfan syndrome, Wagner syndrome, Stickler syndrome and Knobloch syndrome can manifest through abnormalities of the zonular fibers, lens, vitreous fibers, and retina [7–10]. While some individuals may initially present with ocular symptoms, the possibility of underlying systemic involvement is frequently present [11, 12]. Despite ongoing efforts using clinical multimodal imaging to establish genotype-phenotype correlations [13], their utility as a standalone diagnostic tool is constrained. Therefore, without genetic confirmation, the relevance of multi-organ system symptomatology in establishing a HCTD diagnosis remains ambiguous.

The clinical utility of exome sequencing continues to grow, driven by technological advancements and increasingly cost-effective next-generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies [14, 15]. Given that many HCTDs follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, with first-degree relatives facing a 50% risk of inheritance, the identification of pathogenic variants is crucial for clinical management. This genetic information enables healthcare providers to better anticipate and address potential complications, particularly life-threatening conditions such as aortic aneurysms [16]. Furthermore, it facilitates targeted genetic testing and counseling for at-risk family members.

While genetic testing is becoming increasingly prevalent and accessible, it is crucial that physicians maintain expertise in the common clinical manifestations of hereditary HCTDs to facilitate the expeditious identification of individuals warranting a referral to a clinical geneticist for disease-specific genetic testing [17]. In the context of patient counseling for HCTDs, it is essential to acknowledge the potential pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance and the need for further investigation to elucidate their clinical relevance [18].

The objective of this study was to delineate the clinical and genetic features of HCTDs, specifically focusing on the discrepancies between the initial diagnosis based on initial ocular manifestations and the final molecular diagnosis. In addition, we sought to characterize genotype-phenotype correlations and the complex relationship between clinical features and underlying molecular genetics. This included the identification of potentially significant genetic variants not yet classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic (LP), highlighting candidates for future pathogenicity studies.

Methods

Ethnic declaration

The Institutional Review Board at the Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat (EENT) Hospital of Fudan University approved this research (ethical approval number: [2020]2020119). All study procedures adhered to pertinent Chinese regulations and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, all subjects provided informed consent, and blood samples were subsequently collected.

Participants

Fifty-eight Han Chinese patients with HCTD were recruited from the Ophthalmology Department at EENT Hospital. Detailed family histories were obtained from the patients (probands) and/or their relatives, when available.

Patients were included in this study only if they were referred with congenital high myopia, with or without retinal atrophy, and exhibited one or more extraocular features. For the purposes of this study, the criteria for ‘syndromic HCTD’ were defined as: ocular signs and eye exam findings that raise suspicion of retinal disease, encompassing inherited retinal dystrophies and retinal dysplasia, coupled with at least one additional feature identified as a potential manifestation of a multisystem disorder. These additional features could include, for instance, structural malformations, hearing impairment, or growth and developmental disorders of clinical significance. Patients with suspected specific conditions, such as Marfan syndrome, undergo clinical assessment and scoring based on established criteria [19].Patients underwent a thorough eye exam that included several tests: best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), slit-lamp biomicroscopy, dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus photography, fluorescein angiography (FFA), optical coherence tomography (OCT), and electroretinography (ERG). Visual field testing was done when possible. Two or more retinal specialists confirmed the diagnosis of HCTD, and a full medical evaluation was completed before any genetic testing.

Genetic analysis

Next-generation sequencing (NGS), specifically whole-exome sequencing (WES) targeting approximately 20,000 genes, was performed in partnership with We-Health Biology Corp. (Shanghai, China). A commercially available, high-throughput microarray, designed to interrogate 2,406 genes relevant to inherited ocular diseases, was used to further validate potentially pathogenic copy number variations (CNVs). Genomic DNA was extracted and used for genomic library construction. Hybridization probes were employed to capture and enrich target sequences, including exons of the gene of interest, ~ 20 bp flanking splice regions, and the full mitochondrial genome. The enriched library was subjected to quality control prior to sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2000/2500 system, following standard Illumina protocols. Raw reads were initially filtered for quality, and the remaining high-quality reads were aligned to the hg38 human reference genome (UCSC) using BWA software. Variant calling for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (InDels) was performed using GATK Haplotype Caller. Further annotation and filtering were then carried out using specialized databases and bioinformatics prediction tools: Population variant frequency databases: gnomAD, etc… Locus and disease databases: dbSNP, OMIM, HGMD, ClinVar, Decipher, DGV, ClinGen, etc. Bioinformatics prediction tools: SIFT, Polyphen2, LRT, MutationTaster, FATHMM, M-CAP, CADD, REVEL, dbscSNV, SpliceAI, etc… Analysis of copy number variation (CNV) is performed on regions targeted by probes, utilizing the xhmm and clamms algorithms.

All identified SNVs were validated using the Sanger sequencing, while CNVs were validated using quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Bioinformatics analysis

Interpretation rules for sequence variation data are based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Standards and Guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants [20], and a series of general recommendations and specific guidelines successively released by the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group (e.g., PVS1, PS2/PM6, PS3, BA1, PM3, PP5, and BP6, etc.). Further refinement of the interpretation was conducted using gene-specific interpretation guidelines developed by the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Variant Curation Expert Panel (VCEP), specifically for genes like FBN1 et al. [21]. Interpretation rules for CNVs refer to the 2019 ACMG guidelines for CNV interpretation and reporting [22]. Analysis is performed based on the proband’s clinical phenotype and family history, focusing on known genes definitively associated with genetic diseases. Genes with unclear function and pathogenicity are not within the scope of this analysis. Unless there is relevant literature reporting pathogenicity or database inclusion, sequence variant analysis will not include common benign polymorphisms, and synonymous variants and intronic variants that do not affect mRNA splicing. CNVs unrelated to the proband’s clinical phenotype will not be reported if not found.

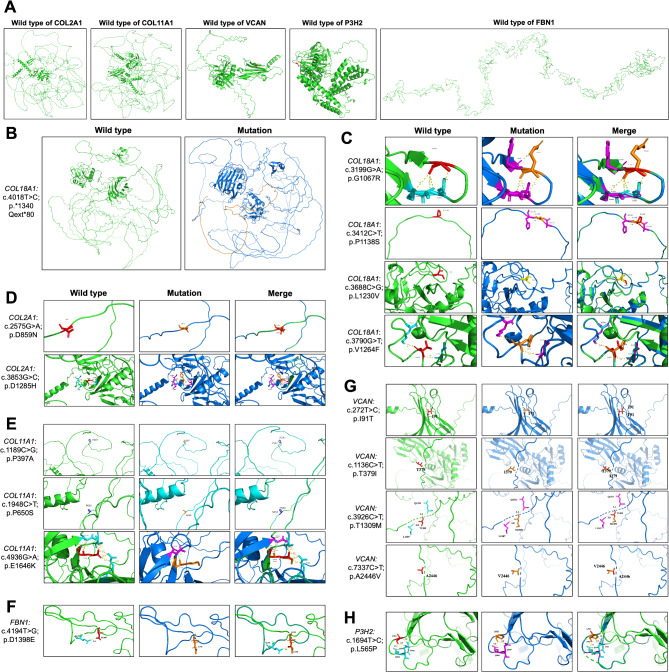

Application of 3D protein structure prediction in the evaluation of variant of uncertain significance (VUS)

Three-dimensional structural models for the proteins COL2A1, COL11A1, COL18A1, VCAN, FBN1, and P3H2 were predicted using Swiss-Pdb Viewer 4.1 (Basel, Switzerland). Analysis of these models suggested that the identified variants may have a deleterious effect on protein function. Potential mechanisms for this functional impairment include disruption of hydrogen bonding networks, alterations in amino acid polarity, and aberrant protein elongation caused by the loss of canonical stop codon mutations.

Conservation analysis

Variant conservation was investigated by retrieving amino acid sequences from diverse species from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Multiple sequence alignment of these sequences was subsequently performed using DNAMAN 6.0 software (https://www.lynnon.com/download/) to analyze conservation patterns at variant positions.

Results

Discrepancy in diagnostic yield between clinical assessment and genetic testing

Our investigation comprised a total of 58 patients from 47 unrelated pedigrees, including 23 females and 35 males. Patients from the same pedigree have been labelled by lowercase superscript in Table 1. The age at referral varied from 4 years to 65 years, with a median age of 19.8 years. Clinical assessment, considering eye and body findings and family history, led to a tentative diagnosis of a syndromic disorder (e.g., Stickler or Marfan syndrome) in 67% (39 of 58) of patients at the point of referral for genetic testing, whereas 33% (19/58) were referred as likely syndromic inherited retinal disease, without a clinically established diagnosis (Table 1). In patients with clear extraocular manifestations or those with detailed family history provided, the molecular diagnostic results matched the clinical suspicion in 21 out of 29 cases, whereas 29 patients lacked a family history or clear extraocular manifestations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of the provisional diagnosis of the 58 patients included in this study and corresponding genetic variants identified as probably causal of their clinical presentation by WES

| Pt. no. | Gender | Age at referral for testing | Provisional diagnosis | Phenotype (HPO terms) | Variants probably or possibly accounting for clinical presentation |

Genetic diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 40 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0008527 Congenital sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0002194 Delayed gross motor development; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL11A1 NM_080629.2: c.1948 C > T p.P650S; c.1189 C > G p.P397A; |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 2 | M | 65 | Retinal detachment with cataract | HP:0000545 Myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.3926 C > T p.T1309M |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 3 | F | 16 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0008527 Congenital sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000083 Renal insufficiency |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.2808 + 5G > A |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 4 | M | 18 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001634 Mitral valve prolaps; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000768 Pectus carinatum; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.2419 + 1G > T |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 5 | M | 11 | FEVR | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000238 Hydrocephalus HP:0001250 Seizures |

COL18A1 NM_001379500.1: c.3790G > T p.V1264F; c.3523_3524del p.L1175Vfs*72 |

Knobloch type I |

| 6 | M | 12 |

Myopia; Congenital Hip Dysplasia |

HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL11A1 NM_001844.5: c.3853G > C p.D1285H |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 7 | M | 12 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape |

COL11A1 NM_001844.5: c.2977G > T p.G993* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 8 | M | 15 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract |

COL11A1 NM_001844.5: c.3003 + 2dup |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 9 | M | 13 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1962 C > T p.G654= |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 10a | M | 11 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.4087–2 A > G |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 11a | M | 37 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.4087–2 A > G |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 12 | M | 15 | FEVR | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL18A1 Deletion: chr21:45455525–46,445,332 (the whole COL18A1 deletion) NM_001379500.1: c.3688 C > G p.L1230V |

Knobloch type I |

| 13 | F | 5 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001634 Mitral valve prolaps; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000768 Pectus carinatum |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.1727G > A p.C576Y |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 14 | M | 29 | Marfan Syndrome |

HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers; HP:0000268 Dolichocephaly; HP:0002650 Scoliosis |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.4194T > G p.D1398E |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 15 | M | 13 | FEVR | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.184del p.V62Sfs*6 |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 16 | M | 15 | FEVR | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.3926 C > Tp.T1309M |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 17 | F | 16 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001634 Mitral valve prolaps; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.4973G > C p.C1658S |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 18 | F | 10 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers; HP:0002650 Scoliosis |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.2920 C > T p.R974C |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 19 | F | 6 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.394G > T p.G132* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 20 | F | 20 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0100807 Long fingers; HP:0000268 Dolichocephaly; HP:0012019 Lens luxation |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.3545G > A p.C1182Y |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 21 | M | 44 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.7337 C > T p.A2446V |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 22 | F | 4 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1221 + 5G > A |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 23 | F | 22 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.272T > C p.I91T |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 24b | F | 46 | Retinitis Pigmentosa | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1693 C > T p.R565C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 25b | F | 17 | FEVR | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1693 C > T p.R565C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 26b | F | 11 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1693 C > T p.R565C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 27 | M | 10 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0011003 Severe myopia |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.4936G > A p.E1646K |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 28 | M | 5 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1030 C > T p.R344* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 29 | F | 8 | Retinitis Pigmentosa | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000518 Cataract |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2678dup p.A895Sfs*49 |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 30 | M | 10 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1658_1675dup p.E553_G558dup |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 31 | M | 11 | Marfan Syndrome |

HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers; HP:0000268 Dolichocephaly; HP:0002650 Scoliosis |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.2201G > T p.C734F |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 32c | M | 25 | Stickler/Wagner Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1221 + 1G > A |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 33c | F | 5 | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1221 + 1G > A |

Stickler Syndrome | |

| 34d | M | 7 | Retinal detachment | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.817-9G > A |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 35d | M | 44 | High myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.817-9G > A |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 36 | M | 8 | FEVR | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.3106 C > T p.R1036* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 37 | F | 16 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers; HP:0002650 Scoliosis |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.1633 C > T p.R545C |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 38e | M | 38 | Wagner/Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1693 C > T p.R565C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 39e | M | 8 | Wagner/Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1693 C > T p.R565C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 40f | M | 11 | Retinitis Pigmentosa | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1435del p.Q479Rfs*150 |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 41f | F | 31 | Retinitis Pigmentosa | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1030 C > T;p.R344* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 42f | F | 4 | Retinitis Pigmentosa | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.1030 C > T;p.R344* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 43g | M | 8 | FEVR | HP:0011446 Abnormality of higher mental function; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000545 Myopia |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2623 C > T p.Q875* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 44g | M | 31 | FEVR | HP:0000545 Myopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2623 C > T p.Q875* |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 45 | F | 34 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.4771G > A p.E1591K |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 46h | F | 49 | Wagner/Stickler/Marfan Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.10101del p.F3367Lfs*12 |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 47h | F | 47 | Wagner/Stickler Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.10101del p.F3367Lfs*12 |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 48 | F | 8 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001382 Joint hypermobility |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2575G > A p.D859N |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 49 | M | 6 | Wagner/Stickler/Marfan Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.3725dup p.D1242Efs*11 |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 50 | M | 15 | High myopia with cataract | HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

COL18A1 NM_001379500.1:c.4018T > C p.*1340Qext*80; c.3523_3524del, p.L1175Vfs*72 |

Knobloch type I |

| 51 | M | 9 | Stickler Syndrome | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001385 Hip dysplasia; HP:0008504 Moderate sensorineural hearing impairment; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2370del p.I791Lfs*90 |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 52 | M | 54 | High myopia with cataract | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000518 Cataract |

COL18A1 NM_001379500.1: c.3199G > A p.G1067R; c.3412 C > T p.P1138S |

Knobloch type I |

| 53 | M | 13 | Marfan Syndrome | HP:0012019 Lens luxation; HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001634 Mitral valve prolaps; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0100807 Long fingers |

FBN1 NM_000138.5: c.6388G > A p.E2130K |

Marfan Syndrome |

| 54 | M | 20 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL11A1 NM_001854.4: c.1630-2del |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 55 | M | 21 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000518 Cataract; HP:0001999 Abnormal facial shape; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

COL2A1 NM_001844.5: c.2710 C > T p.R904C |

Stickler Syndrome |

| 56 | F | 14 | Wagner/Stickler/Marfan Syndrome | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment; HP:0000662 Nyctalopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

VCAN NM_004385.5: c.1136 C > T p.T379I |

Wagner Syndrome |

| 57i | M | 14 | High myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy |

P3H2 NM_018192.4: c.1694T > C p.L565P; c.1684 C > T p.R562* |

P3H2-related myopia with cataract and vitreoretinal degeneration |

| 58i | M | 18 | Retinal detachment with high myopia | HP:0011003 Severe myopia; HP:0001105 Retinal atrophy; HP:0100019 Cortical cataract; HP:0000541 Retinal detachment |

P3H2 NM_018192.4: c.1694T > C p.L565P; c.1684 C > T p.R562* |

P3H2-related myopia with cataract and vitreoretinal degeneration |

Annotation: a−i represents family pedigree

Referrals with potential molecular diagnosis

Whole-exome sequencing was performed on all 58 patients. Analysis of initial genetic testing data based on clinical diagnosis failed to clarify the genetic diagnosis in a subset of patients. We subsequently supplemented the 3D protein conformation and conservational analysis of variants classified as VUS as additional evidence of pathogenicity. Meanwhile, we reviewed the association of clinical manifestations with potential pathogenic variants in each patient, considered information including family co-segregation and previous reports. Finally, we confirmed the genetic diagnosis of all patients and identified 50 potentially pathogenic variants, including 19 previously reported variants and 31 novel variants (Table 2). Among them: (1) Thirty-six cases were Stickler syndrome; (2) Four cases were Knobloch syndrome; (3) Seven cases were Wagner syndrome; (4) Nine cases were Marfan syndrome; (5) Additionally, two cases were P3H2-related myopia with cataract and vitreoretinal degeneration (Table 1).

Table 2.

Summary of identified genes with potentially pathogenic variants in 58 consecutive patients referred for connective tissue disorder for diagnosis

| Patient No. | Sex/Age | Gene | Mode | Reference | Type | Exon/ intron |

Nucleotide | Protein | Effect | Reference | ACMG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | M/13 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon2 | c.184del | p.V62Sfs*6 | Frameshift | Reported [25] | P |

| 19 | F/6 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon6 | c.394G > T | p.G132* | Nonsense | Novel | P |

| 34–35 | M/7, M/47 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | intron13 | c.817-9G > A | - | Splice | Reported [24] | LP |

|

28, 41–42 |

M/5, F/31, F/4 |

COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon17 | c.1030 C > T | p.R344* | Nonsense | Reported [26] | P |

| 32–33 | M/28, F/5 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | intron19 | c.1221 + 1G > A | - | Splice | Reported [37] | P |

| 22 | F/4 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | inrton19 | c.1221 + 5G > A | - | Splice | Novel | LP |

| 40 | M/11 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon23 | c.1435del | p.Q479Rfs*150 | Frameshift | Novel | P |

| 30 | M/10 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon25 | c.1658_1675dup | p.E553_G558dup | Indel | Reported [27] | P |

|

38–39, 24–26 |

M/38, F/8 F/46, F/17, F/11 |

COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon26 | c.1693 C > T | p.R565C | Missense | Reported [39] | P |

| 9 | M/13 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon30 | c.1962 C > T | p.G654= | Synonymous | Reported [28] | LP |

| 51 | M/9 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon36 | c.2370del | p.I791Lfs*90 | Frameshift | Novel | LP |

| 48 | F/8 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon39 | c.2575G > A | p.D859N | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 43–44 | M/8, M/31 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon39 | c.2623 C > T | p.Q875* | Nonsense | Novel | P |

| 29 | F/8 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon40 | c.2678dup | p.A895Sfs*49 | Frameshift | Reported [37] | P |

| 55 | M/21 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon41 | c.2710 C > T | p.R904C | Missense | Reported [43] | P |

| 7 | M/12 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon43 | c.2977G > T | p.G993* | Nonsense | Novel | LP |

| 8 | M/15 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | intron43 | c.3003 + 2dup | - | Splice | Novel | LP |

| 36 | M/8 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon44 | c.3106 C > T | p.R1036* | Nonsense | Reported [29] | P |

| 49 | M/6 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon51 | c.3725dup | p.D1242Efs*11 | Frameshift | Novel | P |

| 6 | M/12 | COL2A1 | AD | NM_001844.5 | het | exon51 | c.3853G > C | p.D1285H | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 1 | F/40 | COL11A1 | AR | NM_001854.4 | het | exon8 | c.1189 C > G | p.P397A | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| COL11A1 | AR | NM_001854.4 | het | exon21 | c.1948 C > T | p.P650S | Missense | Novel | VUS | ||

| 54 | M/20 | COL11A1 | AD | NM_001854.4 | het | intron14 | c.1630-2del | - | Splice | Reported [30] | P |

| 3 | F/16 | COL11A1 | AD | NM_001854.4 | het | intron36 | c.2808 + 5G > A | - | Splice | Novel | LP |

| 10–11 | M/11, M/37 | COL11A1 | AD | NM_001854.4 | het | intron55 | c.4087–2 A > G | - | Splice | Novel | LP |

| 45 | F/34 | COL11A1 | AD | NM_001854.4 | het | exon63 | c.4771G > A | p.E1591K | Missense | Reported [31] | LP |

| 27 | M/10 | COL11A1 | AR | NM_001854.4 | homo | exon64 | c.4936G > A | p.E1646K | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 12 | M/15 | COL18A1 | AR | Deletion length: 989.81Kbp (chr21:45455525–46445332, the whole COL18A1 deletion) | CNV | Novel | LP | ||||

| COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | hemi | exon40 | c.3688 C > G | p.L1230V | Missense | Novel | VUS | ||

| 5, 50 | M/11, M/15 | COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | het | exon40 | c.3523_3524del | p.L1175Vfs*72 | Frameshift | Reported [32] | P |

| 5 | M/11 | COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | het | exon41 | c.3790G > T | p.V1264F | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 50 | M/15 | COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | het | exon42 | c.4018T > C | p.*1340Qext*80 | Extention | Novel | VUS |

| 52 | M/54 | COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | het | exon36 | c.3199G > A | p.G1067R | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| COL18A1 | AR | NM_001379500.1 | het | exon38 | c.3412 C > T | p.P1138S | Missense | Novel | VUS | ||

| 23 | F/22 | VCAN | AD | NM_004385.5 | het | exon3 | c.272T > C | p.I91T | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 56 | F/14 | VCAN | AD | NM_004385.5 | het | exon7 | c.1136 C > T | p.T379I | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 2, 16 | M/65, M/15 | VCAN | AD | NM_004385.5 | het | exon7 | c.3926 C > T | p.T1309M | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 21 | M/44 | VCAN | AD | NM_004385.5 | het | exon8 | c.7337 C > T | p.A2446V | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 46–47 | F/49, F/47 | VCAN | AD | NM_004385.5 | het | exon15 | c.10101del | p.F3367Lfs*12 | Frameshift | Novel | LP |

| 57–58 | M/14, M/18 | P3H2 | AR | NM_018192.4 | het | exon11 | c.1694T > C | p.L565P | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| P3H2 | AR | NM_018192.4 | het | exon11 | c.1684 C > T | p.R562* | Nonsense | Novel | LP | ||

| 37 | F/16 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon14 | c.1633 C > T | p.R545C | Missense | Reported [36] | P |

| 13 | F/5 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon15 | c.1727G > A | p.C576Y | Missense | Reported [34] | P |

| 31 | M/11 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon19 | c.2201G > T | p.C734F | Missense | Reported [38] | P |

| 4 | M/18 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | intron20 | c.2419 + 1G > T | - | Splice | Novel | LP |

| 18 | M/10 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon25 | c.2920 C > T | p.R974C | Missense | Reported [29] | P |

| 20 | F/20 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon29 | c.3545G > A | p.C1182Y | Missense | Reported [35] | P |

| 14 | M/29 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon34 | c.4194T > G | p.D1398E | Missense | Novel | VUS |

| 17 | F/16 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon41 | c.4973G > C | p.C1658S | Missense | Novel | LP |

| 53 | M/13 | FBN1 | AD | NM_000138.5 | het | exon53 | c.6388G > A | p.E2130K | Missense | Reported [33] | P |

Stickler syndrome

Thirty-six patients received a molecular diagnosis of Stickler syndrome. Notably, 29 of these patients presented with heterozygous mutations in COL2A1, the most frequently implicated gene in type 1 Stickler syndrome among Chinese patients. The analysis of this Stickler syndrome cohort revealed 27 disease-causing variants. Twelve of these variants were previously documented, while 15 were novel (Table 2).Among these patients, four patients were initially diagnosed with FEVR, five patients were initially diagnosed with vitreoretinal degeneration with pathological myopia, five patients were initially diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and only 11 patients were initially diagnosed with Stickler syndrome (Table 1). The most common ocular symptom was observed as vitreoretinal degeneration with myopia at 89%, Variations in diagnostic pick-up rate were observed based on midfacial abnormality and age of hearing loss onset. Midfacial abnormality and hearing loss was associated with higher yield of provisional diagnosis (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Bioinformatic analysis results of the novel variants

| Gene | Reference | Type | Nucleotide | Protein | gnomAD_ exome_ALL |

REVEL | SIFT | MutationTaster | GERP | Polyphen2 | ClinPred | FATHMM | Splice AI |

SPI DEX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL18A1 | NM_001379500.1 | het | c.3199G > A | p.G1067R | - | U(0.393) |

Deleterious (0) |

Disease_causing (0.99) |

Conserved (3.69) |

Probably_damaging (0.997) |

Neutral (0.25112) |

Tolerated (0.46) |

0 | 0.00408 |

| COL18A1 | NM_001379500.1 | het | c.3403 C > T | p.P1135S | . | U(0.365) |

Tolerated (0.051) |

Disease_causing (1) |

- |

Probably_damaging (0.999) |

Deleterious (0.93355) |

Damaging (-3.04) |

0 | - |

| COL18A1 | NM_001379500.1 | hemi | c.3688 C > G | p.L1230V | . | LB(0.238) | 0 |

Disease_causing (1) |

- |

Probably_damaging (0.999) |

Deleterious (0.97923) |

Tolerated (0.77) |

DG (0.02) |

- |

| COL18A1 | NM_001379500.1 | het | c.3790G > T | p.V1264F | - | U(0.361) |

Deleterious (0) |

Disease_causing (0.99) |

Conserved (4.28) |

Probably_damaging (0.923) |

Deleterious (0.97233) |

Tolerated (0.66) |

AG (0.31) |

0.0678 |

| COL18A1 | NM_001379500.1 | het | c.4018T > C | p.*1340Qext*80 | - | - | - |

Disease_causing (1) |

- | - | - | - | - | - |

| COL2A1 | NM_001844.5 | het | c.2575G > A | p.D859N | 0.00001616 | U(0.463) |

Tolerated (0.06) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (5.46) |

Possibly_damaging (0.497) |

Deleterious (0.79225) |

Damaging (-3.37) |

DG (0.01) |

-3.786 |

| COL2A1 | NM_001844.5 | het | c.3853G > C | p.D1285H | - | D(0.877) |

Deleterious (0.01) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (4.62) |

Probably_damaging (0.998) |

Deleterious (0.99379) |

Tolerated (-1.33) |

0 | -0.0376 |

| COL11A1 | NM_001854.4 | het | c.1189 C > G | p.P397A | - | LB(0.156) |

Tolerated (0.75) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (5.41) |

Benign(0.003) | N/A |

Damaging (-2.21) |

0 | 0.0268 |

| COL11A1 | NM_001854.4 | het | c.1948 C > T | p.P650S | - | U(0.575) |

Tolerated (0.05) |

Disease_causing (0.99) |

Conserved (5.81) |

Benign(0.197) |

Deleterious (0.98349) |

Damaging (-5.05) |

AL (0.02) |

0.0223 |

| COL11A1 | NM_001854.4 | homo | c.4936G > A | p.E1646K | - | D(0.887) |

Deleterious (0.002) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (5.52) |

Probably_damaging (0.995) |

Deleterious (0.99863) |

Damaging (-4.15) |

0 | -1.2328 |

| VCAN | NM_004385.5 | het | c.272T > C | p.I91T | 0.00001991 | U(0.393) |

Deleterious (0) |

Disease_causing (0.995) |

Conserved (5.78) |

Possibly_damaging (0.756) |

Deleterious (0.60976) |

Tolerated (-0.09) |

0 | -0.4387 |

| VCAN | NM_004385.5 | het | c.1136 C > T | p.T379I | 0.00000398 | U(0.38) |

Deleterious (0.001) |

Disease_causing (0.834) |

Conserved (4.27) |

Possibly_damaging (0.728) |

Deleterious (0.76759) |

Damaging (-2.17) |

AG (0.01) |

-0.0533 |

| VCAN | NM_004385.5 | het | c.3926 C > T | p.T1309M | - | U(0.385) |

Deleterious (0) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (5.61) |

Probably_damaging (0.999) |

Neutral (0.19621) |

Damaging (-2.28) |

0 | -0.0973 |

| VCAN | NM_004385.5 | het | c.7337 C > T | p.A2446V | - | LB(0.049) |

Deleterious (0.009) |

Polymorphism(1) |

Nonconserved (0.865) |

Benign(0.003) |

Neutral (0.07256) |

Damaging (-1.51) |

0 | -0.0084 |

| FBN1 | NM_000138.5 | het | c.4194T > G | p.D1398E | - | U(0.579) |

Deleterious (0) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Nonconserved (-0.819) |

Possibly_damaging (0.474) |

Deleterious (0.97798) |

Damaging (-2.37) |

DG (0.85) |

-1.2496 |

| P3H2 | NM_018192.4 | het | c.1694T > C | p.L565P | - | LB(0.265) |

Deleterious (0.02) |

Disease_causing (1) |

Conserved (5.71) |

Benign (0.106) |

Deleterious (0.97473) |

Tolerated (0.84) |

0 | 0.0582 |

Five individuals with clinically evident midfacial hypoplasia (three familial and two sporadic cases) were identified as carrying the c.1693 C > T (p.R565C) missense variant in the COL2A1 gene. This specific variant is recognized as pathogenic in Stickler syndrome. Three additional patients presented with high myopia accompanied by vitreoretinal degeneration, along with hearing impairment. Among them, two had a similar family history. Genetic testing revealed a nonsense variant, c.1030 C > T (p.R344*), in COL2A1.

Knobloch syndrome type 1

Molecular diagnosis ultimately led to the confirmation of Knobloch syndrome type 1 in 4 patients. Significantly, one patient displayed a novel copy number variation causing a deletion in the COL18A1, which was categorized as a LP variant according to ACMG classification. In addition, a novel missense variant of COL18A1: c.3688 C > G (p.L1230V) was also identified in the same patient. Notably, two patients were found to carry a novel heterozygous pathogenic variant, c.3523_3524del (p.L1175Vfs*72). In this cohort of patients with a molecularly confirmed diagnosis of Knobloch syndrome, two were clinically suspected of having familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR), two were diagnosed with high myopia accompanied by lattice degeneration of the retina.

Wagner syndrome

Genetic testing ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of Wagner syndrome in seven patients, all of whom harbored previously unreported variants of VCAN. Specifically, five patients exhibited a newly identified missense variant of VUS. Two patients harbored a novel heterozygous pathogenic variant, c.10101del (p.F3367Lfs*12). Of the five patients, two initially received a provisional clinical diagnosis of high myopia with vitreoretinal degeneration, with one experiencing rapid progression to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD). One patient was suspected of having Marfan syndrome, and two patients were provisionally diagnosed with FEVR.

Marfan syndrome

Nine patients were diagnosed with Marfan syndrome via clinical assessment and genetic testing. All 9 patients presented with lens subluxation, underwent cataract surgery with simultaneous intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, and subsequently developed RRD after cataract surgery, requiring vitrectomy. Except for one adult patient with RRD whose fundus findings raised suspicion for FEVR, all patients were clinically suspected of having Marfan syndrome and were ultimately genetically confirmed.

P3H2 -related myopia with cataract and vitreoretinal degeneration

Two biological brothers presented with high myopia and retinal lattice degeneration, along with early-onset cataracts. Their initial clinical presentation suggested Stickler syndrome, but subsequent genetic testing confirmed variants of P3H2. Notably, both brothers carried the identical two compound heterozygous variants: c.1694T > C (p.L565P) and c.1684 C > T (p.R562*), both situated within exon 11.

Three-Dimension protein structure prediction of gene pathogenicity

To determine the pathogenicity of certain gene variants, we used an in silico approach involving 3D protein models to predict their pathogenic potential (Fig. 1). Figure 1 A and Fig. 1B present the 3D structures of six wild-type proteins: COL2A1, COL11A1, COL18A1, VCAN, FBN1, and P3H2. Figure 1B further illustrates an abnormal extension in the COL18A1 protein, resulting from the extension mutation c.4018T > C (p.1340*Qext80). This extension is visualized in orange and represents an 80 amino acid insertion in the mutant COL18A1 protein model. From Fig. 1C and H, “Merge” illustrates the superposition of the protein structure before and after mutation. The wild-type conformation is depicted in green, and the mutant conformation in blue. Figure 1C illustrates that COL18A1: c.3199G > A (p.G1067R) variant results in a change from a non-polar hydrophobic amino acid to a basic amino acid. Wild-type G1067 forms hydrogen bonds with R1063 at spacings of 3.9 Å, 3.1 Å, and 3.3 Å; and with V1064 at a spacing of 2.9 Å. The mutant R1067 forms a hydrogen bond with V1064 at a spacing of 2.9 Å, with R1063 at 3.1 Å and 3.2 Å; and with F1068 at 3.3 Å spacing. COL18A1: c.3412 C > T (p.P1138S) variant results in non-polar hydrophobic amino acids becoming basic amino acids. The wild-type P1138 amino acid does not form hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acids, and the mutant S1138 amino acid forms hydrogen bonds with H1139 at a spacing of 2.8Å. COL18A1: c.3688 C > G (p.L1230V) variant results in a change from leucine to valine at amino acid position 1230, locating in the random coil region. COL18A1: c.3790G > T (p.V1264F), the wild-type V1264 forms hydrogen bonds with K1273 and I1256 at spacings of 2.7 Å and 3.0 Å, respectively; mutant F1264 forms hydrogen bonds with K1273 and I1256 at spacings of 2.7 Å and 2.9 Å, respectively. Figure 1D shows that COL2A1: c.2575G > A (p.D859N) variant causes an acidic amino acid changing to a neutral amino acid in the random coil region. COL2A1: c.3853G > C (p.D1285H) variant causes an acidic amino acid changing to basic amino acid. The wild-type D1285 forms three hydrogen bonds with T1282 at spacings of 2.9 Å, 2.7 Å, and 3.2 Å, respectively; with L1288 at spacing of 3.2 Å; and with L1289 at spacing of 3.0 Å. Mutant H1285 amino acid forms two hydrogen bonds with T1282 with spacings of 3.4 Å and 3.1 Å, respectively; with L1288 with spacing of 3.2 Å; and with L1289 with spacing of 3.0 Å. Figure 1E shows that COL11A1: c.1189 C > G (p.P397A) variant results in a change in amino acids from sub amino acids to aliphatic amino acids locating in the random coil region. COL11A1: c.1948 C > T (p.P650S) variant causes a change from non-polar amino acid to polar amino acid locating in the random coil region. COL11A1: c.4936G > A (p.E1646K) variant causes a change from a negatively charged polar amino acid change to a positively charged polar amino acid. Wild-type E1646 forms hydrogen bonds with N1640 at spacings of 2.9 Å, 3.1 Å, 4.6 Å, 3.1 Å, and 2.7 Å; and with S1643 at spacings of 3.1 Å, 2.9 Å, and 2.8 Å. Mutant K1646 only forms hydrogen bonds of 2.9 Å and 3.21 Å with N1640. Figure 1F illustrates FBN1: c.4194T > G (p.D1398E) variant: the wild-type D1398 amino acid forms a hydrogen bond with Q1376 at a spacing of 2.5Å. The mutant E1398 amino acid does not form hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acids. Figure 1G shows that VCAN: 272T > C (p.I91T) variant causes a change of a non-polar hydrophobic amino acid to a polar neutral amino acid. VCAN: c.1136 C > T (p.T379I) variant causes a change of a polar neutral amino acid to a non-polar hydrophobic amino acid. VCAN: c.3926 C > T (p.T1309M) variant results in a change of a hydrophilic neutral amino acid to a hydrophobic amino acid. VCAN: c.7337 C > T (p.A2446V) variant causes amino acid to change from alanine to valine. Figure 1H shows that P3H2: c.1694 C > T (p.L565P) variant: the wild-type L565 forms a hydrogen bond with Q568 at a spacing of 3.5 Å, with Q569 at a spacing of 2.9 Å, and with N503 at a spacing of 3.0 Å. The mutant P565 forms a hydrogen bond with Q568 at a spacing of 3.5 Å, and with Q569 at a spacing of 2.9 Å.

Fig. 1.

The predicted effect of variants rated as VUS in 3D protein structures. A and B present the 3D structures of six wild-type proteins: COL2A1, COL11A1, COL18A1, VCAN, FBN1 and P3H2. From C to H, “Merge” represents the superposition before and after mutation, with green representing the wild type and blue representing the mutant type

Conservation analysis

Conservation analysis demonstrated the highly conserved amino acid residues among these 15 missense variants for VUS (Fig. 2). Multiple sequence alignment of the 15 missense variants rated as VUS from different species. Species name cross-reference: Homo sapiens, human; Mus musculus, house mouse; Rattus norvegicus, Norway rat; Bos taurus, domestic cattle; Pan troglodytes, chimpanzee; Canis lupus familiaris, dog. “*” indicates high conservatism in the species.

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of the 15 missense variants rated as VUS from different species. Species name cross-reference: Homo sapiens, human; Mus musculus, house mouse; Rattus norvegicus, Norway rat; Bos taurus, domestic cattle; Pan troglodytes, chimpanzee; Canis lupus familiaris, dog; Macaca mulatta, Rhesus monkey; Macaca nemestrina, pig-tailed macaque; Mandrillus leucophaeus, drill; Cercocebus atys, sooty mangabey; Theropithecus gelada, gelada. “*” indicates high conservatism in the species

Revision and refinement of initial clinical diagnosis

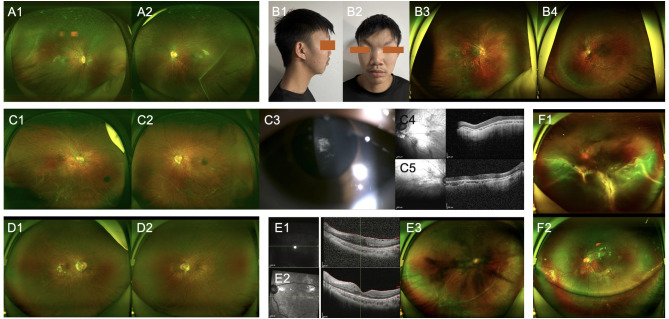

Timely genetic testing in select cases refined the clinical phenotype, enhancing counseling precision. For example, in patients No. 28 and No.42, ocular examination performed at 4–5 years of age did not provide sufficient diagnostic specificity to differentiate between FEVR and Stickler syndrome, although both eyes exhibit high myopia accompanied by peripheral retinal degeneration distributed along the retinal vasculature, and there are no apparent extraocular features, the family history remains unclear. Patient No.29 received a diagnosis of RP at 8 years of age. Her initial funduscopic examination demonstrated abnormal peripheral retinal regions and membrane-like vitreous fibers (Fig. 3A1-A2). Genetic analysis initially directed towards genes implicated in RP returned negative findings. A subsequent decline in auditory function was noted several months later. A detailed family history elicited a similar clinical phenotype in her father, exhibiting clinical manifestations suggestive of Stickler syndrome, our investigative approach was redirected towards the analysis of genes associated with this condition, revealing a heterozygous variant in COL2A1: c.1221 + 1G > A [10]. This splice variant, already associated with Stickler Syndrome in previous reports, is predicted to negatively impact the gene’s ability to be translated into a functional protein [23]. Patient No.5, a 11-year-old male patient presented with high myopia and peripheral retinal degeneration in both eyes, (Fig. 3B1-B4). Family history was denied at the initial presentation, and no definitive clinical diagnosis was initially established. Genetic testing revealed compound heterozygous variants of COL18A1: c.3523_3524del (p.L1175Vfs*72), c.3790G > T (p.V1264F). This patient was eventually diagnosed with Knobloch syndrome.

Fig. 3.

Clinical manifestations in heritable connective tissue diseases.

Patient No.3 exhibited macular dysplasia both and is complicated by significant cataracts (Fig. 3C1-C5). Genetic sequencing was expedited, which ultimately identified COL11A1: c.2808 + 5G > A, leading to a diagnosis of Stickler syndrome, confirming the misleading nature of the condition.

Two patients presented with high myopia and peripheral retinal degeneration, accompanied by vitreous opacities (Fig.D1-D2; Fig E1-E3). Prior to genetic testing, a provisional clinical diagnosis was not possible. Subsequently, pathogenic variants were identified in exon 8 and exon 15 of the VCAN gene, confirming a diagnosis of Wagner syndrome.

A previously undiagnosed individual with P3H2 gene variants manifested high myopia and peripheral retinal degeneration (Fig.F1-F2) and, regrettably, presented with RRD which was promptly addressed with surgical intervention.

Refining family risk estimates

Among the 58 study participants, 38 (65.5%) were simplex cases with no known family history of ocular disorders, while 20 (34.5%) had at least one affected family member. The inheritance pattern was predominantly autosomal dominant, observed in 51 patients (87.9%), with the remaining 8 patients (12.1%) showing autosomal recessive inheritance. Genetic testing proved valuable in assessing recurrence risks for future pregnancies and family members of simplex disease patients No. 15, 36, and 50. These male probands, initially given a provisional clinical diagnosis of FEVR, were found to have diverse genetic etiologies upon further investigation. This resulted in differing recurrence risk profiles: Patient No. 15 exhibited a de novo heterozygous variant in COL2A1, associated with a low recurrence risk for parental pregnancies (comparable to the general population) but a 50% risk for his progeny. Patient No. 50 presented with compound heterozygous COL18A1 variants, including a novel extension variant due to a loss of canonical stop codon, indicating a 25% recurrence risk of Knobloch syndrome type 1 and a 50% risk of being a carrier of heterozygous variant in COL18A1 in future parental pregnancies. As for the patient himself, his offspring will be mostly a carrier of heterozygous variant in COL18A1. However, it is also recommended that the patient’s spouse undergo prenatal genetic screening, with particular attention to the COL18A1 gene. Patient No.36 is included in this cohort, although specific genetic findings are not elaborated upon in this excerpt. The confirmed pathogenic variant in Patient No. 54 involves an intronic nucleotide deletion in the COL11A1. Given the established paternal inheritance of this variant, future reproductive counseling can be effectively tailored.

Discussion

Ocular manifestations in hereditary connective tissue disorders can overlap [13], leading to inaccurate initial clinical diagnoses and potentially misleading clinicians to focus on variant screening related to the initial diagnosis, thereby missing the true causative genes. Through reanalysis of next-generation sequencing data, novel variants previously unreported were identified and further supported by various pathogenicity analyses, ultimately correlating with the patients’ clinical phenotypes. The relevant studies of 19 reported variants were listed in Table 2 to facilitate the use of evidence of pathogenicity [2, 24–40].

A provisional clinical diagnosis was established in a subset of patients based on a comprehensive evaluation. Nevertheless, a considerable discrepancy was observed between the initial provisional diagnosis and the final molecular diagnosis in a significant subset of patients, most notably in individuals ultimately diagnosed with Stickler syndrome [25].

Possible explanations for the discrepancy in diagnostic rates before and after genetic testing include: the significant phenotypic overlap in ocular manifestations among certain distinct genetic etiologies; the possibility that some ocular phenotypes were in their early stages at the time of testing, leading to diagnostic ambiguity; the absence of certain extraocular manifestations due to the underlying genetic architecture; in pediatric patients, distinguishing whether high myopia is caused by a genetic disease or is multifactorial early-onset high myopia presents significant challenges.

Among those with agreement between the provisional clinical diagnosis and the molecular diagnosis, approximately half exhibited extraocular manifestations. This indicates that significant factors contributing to the high diagnostic rate are relatively confirming extraocular symptoms (e.g., hearing impairment and learning disabilities) or signs (e.g., facial and joint features) and a clear positive family history [5, 25]. These relatively distinct phenotypic clues can help infer the likely category of underlying genetic disorder in these patients, but the proportion of patients exhibiting clear manifestations is quite limited.

For individuals with Stickler syndrome, genetic testing enabled the differentiation of high myopia with retinal degeneration from syndromic conditions. For example, participant No.43, an 8-year-old male patient presented with high myopia accompanied by extensive peripheral retinal degeneration. The initial diagnosis was FEVR. Subsequently, the accompanying family member was changed to his father, revealing that the father exhibited similar but milder manifestations. Following genetic testing, a pathogenic nonsense variant COL2A1: c.2623 C > T (p.Q875*) was identified, leading to the final diagnosis of Stickler syndrome.

Notably, four patients ultimately diagnosed with Knobloch syndrome via genetic testing had no prior accurate clinical presumptive diagnosis. Two were clinically suspected of having FEVR, and two were considered to have high myopia with early-onset cataract. These 4 patients exhibited similar ocular manifestations, including bilateral high myopia with vitreoretinal degeneration. Two of them developed rapidly progressive RRD in one eye during follow-up, both of whom underwent timely vitrectomy to preserve vision. The overall ocular phenotype in young individuals raises the possibility of underlying genetic factors. Genetic testing performed on all 4 patients, however, no positive findings related to FEVR were identified. Extending the genetic analysis to encompass other inherited vitreoretinal diseases demonstrated the presence of a previously reported frameshift variant of COL18A1: c.3523_3524del (p.L1175Vfs*72) in two patients, while the remaining 2 patients harbored novel variants. Given the frequent association of Knobloch syndrome with intracranial abnormalities, such as occipital bone defects [41], patients were subsequently referred to neurosurgery for follow-up. Considering the potential for these variants to involve other critical organ systems, prompt genetic evaluation is crucial for ensuring optimal overall patient health.

Determining the optimal timing and sequence of interventions for genetically heterogeneous disorders, exemplified by HCTD, is a subject of substantial debate [41, 42]. The findings of this study propose a diagnostic pathway for HCTD. Early genetic testing is advisable when initial ophthalmic assessment suggests HCTD, as evidenced by relevant ocular symptoms in conjunction with suggestive family history, fundus appearance, imaging findings, or electrophysiology results. This approach is likely to facilitate an accurate diagnosis.

In this study, whole exome sequencing was implemented as the initial diagnostic modality due to its efficacy, rapid results, and association with a low frequency of incidental or non-specific findings [43]. Furthermore, it is anticipated that this approach will result in the omission of only a limited number of detectable disease-associated variants. While the broad coverage of WES allowed for the detection of thousands of variant sites, it correspondingly increased the complexity of analysis. Our initial strategy involved focusing on the analysis of relevant pathogenic genes based on clinical suspicion. However, due to the non-specific nature of the ocular manifestations, the initial diagnoses were often inaccurate, resulting in the failure to identify pathogenic variants in the suspected genes for many patients. Thus, we adjusted our approach to investigate mutation sites within highly suggestive genes based on clinical presentations, and further, to explore the pathogenic gene spectrum of other disorders that may exhibit these ocular phenotypes. Iterative bioinformatic re-analysis of the WES data of these patients revealed a cohort of novel variants. Pathogenicity assessment of these variants, performed using techniques such as three-dimensional protein structure modeling and conservation analysis, ultimately provided evidence in support of molecular diagnoses.

Employing this strategy, we have diagnosed several patients with Knobloch syndrome, previously not considered in the differential diagnosis, as well as Stickler syndrome, which initially presented with subtle manifestations. Accurate diagnosis not only facilitates proactive management of ocular complications but also enables appropriate referrals for comprehensive health protection, as these disorders can lead to severe, even life-threatening, damage to other organ systems.

In conclusion, given that these diseases exhibit both commonalities and differences in their clinical presentations while stemming from distinct gene variants, and that initial clinical diagnoses can bias the direction of genetic analysis, we are conducting and reporting a cohort study on patients with fundus manifestations of hereditary connective tissue diseases. Besides, our study also expands the mutational spectrum of HCTDs by 31 novel variants. The aim of this study is to deepen clinicians’ awareness and understanding of this spectrum of disorders, enhance their diagnostic capabilities, and improve the interpretation of genetic reports. This study also aims to provide future researchers with a traceable research strategy and analyzable data.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the members of this project as well as all.

the volunteers who participated in this project. The authors also would like to thank We-Health biology Corp for the technical support.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Project administration, Q.C., F.G. and X.H. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Q.S., Y.J., F.G., X.H. and Q.C. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Q.S. and Y.J. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shanghai “Rising Stars of Medical Talents” Youth Development Program, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant NSFC 82101149, 82201204, 82171078) and the Shanghai Hospital Development Center Foundation (SHDC12023116).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for data collection and analysis was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Eye and ENT Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China on November 26, 2020. The ethical approval number was [2020]2020119. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their parents or legal guardian in the case of children under 16 included in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qin-Meng Shu and Yu-Qiao Ju contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xin Huang, Email: fd2017huangxin@163.com.

Feng-juan Gao, Email: gaofengjuan0815@sina.com.

Qing Chang, Email: dr_changqing@126.com.

References

- 1.Bascom R, Schubart JR, Mills S, Smith T, Zukley LM, Francomano CA, McDonnell N. Heritable disorders of connective tissue: description of a data repository and initial cohort characterization. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179:552–60. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veatch OJ, Steinle J, Hossain WA, Butler MG. Clinical genetics evaluation and testing of connective tissue disorders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Genomics. 2022;15:169. 10.1186/s12920-022-01321-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson SP, Twigg SRF, Sutherland-Smith AJ, Biancalana V, Gorlin RJ, Horn D, et al. Localized mutations in the gene encoding the cytoskeletal protein filamin A cause diverse malformations in humans. Nat Genet. 2003;33:487–91. 10.1038/ng1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colombi M, Dordoni C, Chiarelli N, Ritelli M. Differential diagnosis and diagnostic flow chart of joint hypermobility syndrome/ehlers-danlos syndrome hypermobility type compared to other heritable connective tissue disorders. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2015;169 C:6–22. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asif MI, Kalra N, Sharma N, Jain N, Sharma M, Sinha R. Connective tissue disorders and eye: A review and recent updates. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:2385–98. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_286_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinle J, Hossain WA, Veatch OJ, Strom SP, Butler MG. Next-generation sequencing and analysis of consecutive patients referred for connective tissue disorders. Am J Med Genet A. 2022;188:3016–23. 10.1002/ajmg.a.62905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acón D, Hussain RM, Yannuzzi NA, Berrocal AM. Complex combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in a Twenty-Three-Year-Old male with Wagner syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020;51:467–71. 10.3928/23258160-20200804-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borella Y, Dhaenens C-M, Grunewald O, Caputo G. Wagner syndrome: novel VCAN variant and prophylactic management with encircling band and retinopexy. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2024;34:102061. 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng JY, Zarook E, Nicholson L, Khanji MY, Chahal CAA. Eyes and the heart: what a clinician should know. Heart. 2023;109:1670–6. 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-322081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Lin Y, Chen C, Zhu Y, Gao H, Li T, et al. Targeted next–generation sequencing identifies two novel COL2A1 gene mutations in stickler syndrome with bilateral retinal detachment. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:1819–26. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su R, Yan H, Li N, Ding T, Li B, Xie Y, et al. Application value of blood metagenomic next-generation sequencing in patients with connective tissue diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:939057. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.939057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pope MK, Ratajska A, Johnsen H, Rypdal KB, Sejersted Y, Paus B. Diagnostics of hereditary connective tissue disorders by genetic Next-Generation sequencing. Genetic Test Mol Biomarkers. 2019;23:783–90. 10.1089/gtmb.2019.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujinami-Yokokawa Y, Ninomiya H, Liu X, Yang L, Pontikos N, Yoshitake K, et al. Prediction of causative genes in inherited retinal disorder from fundus photography and autofluorescence imaging using deep learning techniques. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:1272–9. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-318544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Shanks M, Packham E, Williams J, Haysmoore J, MacLaren RE, et al. Next generation sequencing using phenotype-based panels for genetic testing in inherited retinal diseases. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020;41:331–7. 10.1080/13816810.2020.1778736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheck LHN, Esposti SD, Mahroo OA, Arno G, Pontikos N, Wright G, et al. Panel-based genetic testing for inherited retinal disease screening 176 genes. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2021;9:e1663. 10.1002/mgg3.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milewicz DM, Braverman AC, de Backer J, Morris SA, Boileau C, Maumenee IH, et al. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:64. 10.1038/s41572-021-00298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiman OA, Taylor RL, Lenassi E, Smith JC, Douzgou S, Ellingford JM, et al. Diagnostic yield of panel-based genetic testing in syndromic inherited retinal disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:576–86. 10.1038/s41431-019-0548-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellingford JM, Barton S, Bhaskar S, Williams SG, Sergouniotis PI, O’Sullivan J, et al. Whole genome sequencing increases molecular diagnostic yield compared with current diagnostic testing for inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1143–50. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, Callewaert BL, de Backer J, Devereux RB, et al. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:476–85. 10.1136/jmg.2009.072785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drackley A, Somerville C, Arnaud P, Baudhuin LM, Hanna N, Kluge ML, et al. Interpretation and classification of FBN1 variants associated with Marfan syndrome: consensus recommendations from the clinical genome resource’s FBN1 variant curation expert panel. Genome Med. 2024;16:154. 10.1186/s13073-024-01423-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, Kantarci S, Kearney H, Patel A, et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics (ACMG) and the clinical genome resource (ClinGen). Genet Med. 2020;22:245–57. 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian R, Tong P, He Y, Zang L, Zhou S, Tian Q. Exome sequencing-aided precise diagnosis of four families with type I stickler syndrome. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2024;12:e2331. 10.1002/mgg3.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards AJ, McNinch A, Whittaker J, Treacy B, Oakhill K, Poulson A, Snead MP. Splicing analysis of unclassified variants in COL2A1 and COL11A1 identifies deep intronic pathogenic mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:552–8. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D-D, Gao F-J, Hu F-Y, Li J-K, Zhang S-H, Xu P, et al. Next-generation sequencing-aided precise diagnosis of stickler syndrome type I. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:e440–6. 10.1111/aos.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruth M, Liberfarb MD, PhD1 HP, Levy MD, PhD2 PS, Rose MD, Wilkin DJ. Ph. The stickler syndrome: genotype/phenotype correlation in 10 families with stickler syndrome resulting from seven mutations in the type II collagen gene locus COL2A1. Genet Sci. 2003;5:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Terhal PA, Nievelstein RJAJ, Verver EJJ, Topsakal V, van Dommelen P, Hoornaert K, et al. A study of the clinical and radiological features in a cohort of 93 patients with a COL2A1 mutation causing spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita or a related phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A:461–75. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards AJ, Laidlaw M, Meredith SP, Shankar P, Poulson AV, Scott JD, Snead MP. Missense and silent mutations in COL2A1 result in stickler syndrome but via different molecular mechanisms. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:639. 10.1002/humu.9497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards AJ, Laidlaw M, Whittaker J, Treacy B, Rai H, Bearcroft P, et al. High efficiency of mutation detection in type 1 stickler syndrome using a two-stage approach: vitreoretinal assessment coupled with exon sequencing for screening COL2A1. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:696–704. 10.1002/humu.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin S et al. Stickler syndrome: further mutations in COL11A1 and evidence for additional locus heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999 Oct-Nov; 7(7):807-14. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang H, Xiao F, Dong X, Lu Y, Cheng G, Wang L, et al. Diagnostic and clinical utility of next-generation sequencing in children born with multiple congenital anomalies in the China neonatal genomes project. Hum Mutat. 2021;42:434–44. 10.1002/humu.24170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki OT, Sertié AL, Der Kaloustian VM, Kok F, Carpenter M, Murray J, et al. Molecular analysis of collagen XVIII reveals novel mutations, presence of a third isoform, and possible genetic heterogeneity in knobloch syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1320–9. 10.1086/344695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnaud P, Hanna N, Aubart M, Leheup B, Dupuis-Girod S, Naudion S, et al. Homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations in the FBN1 gene: unexpected findings in molecular diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2017;54:100–3. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attanasio M, Lapini I, Evangelisti L, Lucarini L, Giusti B, Porciani M, et al. FBN1 mutation screening of patients with Marfan syndrome and related disorders: detection of 46 novel FBN1 mutations. Clin Genet. 2008;74:39–46. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baudhuin LM, Kotzer KE, Lagerstedt SA. Decreased frequency of FBN1 missense variants in Ghent criteria-positive Marfan syndrome and characterization of novel FBN1 variants. J Hum Genet. 2015;60:241–52. 10.1038/jhg.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper J. Mutation screening of all 65 exons of the fibrillin-1 gene in 60 patients with Marfan syndrome: report of 12 novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 1997;10(4):280–9. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:4%3C280::AID-HUMU3%3E3.0.CO;2-L [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Hoornaert KP, Vereecke I, Dewinter C, Rosenberg T, Beemer FA, Leroy JG, et al. Stickler syndrome caused by COL2A1 mutations: genotype-phenotype correlation in a series of 100 patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:872–80. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzke S, Booms P, Tiecke F, Palz M, Pletschacher A, Türkmen S, et al. TGGE screening of the entire FBN1 coding sequence in 126 individuals with Marfan syndrome and related fibrillinopathies. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:197–208. 10.1002/humu.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wenmin S, Huang L, Xu Y, Xiao X, Li S, Jia X, Gao B, Wang P. Xiangming Guo, and Qingjiong Zhang. Exome sequencing on 298 probands with Early-Onset high myopia: approximately One-Fourth show potential pathogenic mutations in RetNet genes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:8365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ballo R, Beighton PH, Ramesar* RS. Stickler-like syndrome due to a dominant negative mutation in the COL2A1 gene. Am J Med Genet. 1998 Oct 30;80(1):6-11. 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981102)80:1%3C6::aid-ajmg2%3E3.0.co;2-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Li S, Wang Y, Sun L, Yan W, Huang L, Zhang Z, et al. Knobloch syndrome associated with novel COL18A1 variants in Chinese population. Genes (Basel). 2021. 10.3390/genes12101512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor RL, Parry NRA, Barton SJ, Campbell C, Delaney CM, Ellingford JM, et al. Panel-Based clinical genetic testing in 85 children with inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:985–91. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, Zhang J, Chen N, Wang L, Zhang F, Ma Z, et al. Application of whole exome and targeted panel sequencing in the clinical molecular diagnosis of 319 Chinese families with inherited retinal dystrophy and comparison study. Genes (Basel). 2018. 10.3390/genes9070360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.