Abstract

Bioactivity of the hormone and growth factor activin A is central to fertility and health. Dysregulated circulating activin levels occur with medication usage and multiple pathological conditions. The inhibin-alpha knockout mouse (InhaKO) models chronic activin elevation and unopposed activin A bioactivity. In InhaKO fetal testes, lipid droplet, steroid profiles, and seminiferous cords are abnormal; adults develop gonadal and adrenal tumors due to chronic activin A excess exposure. Here we address how this exposure affects lipid, metabolite, and steroid composition in whole testes, ovaries, and adrenals of adult InhaKO mice using histological, transcriptomic, and mass spectrometry (MS) methods, including MS imaging (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-MS imaging). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-MS imaging delineated spatial lipid profiles within interstitial, inner cord, and outer cord regions containing normal spermatogenesis; these differed between wild-type and KO samples. In proximity to tumors, lipids showed distinctive distribution patterns both within and adjacent to the tumor. Significantly altered lipids and metabolic profiles in whole InhaKO testes homogenates were linked to energy-related pathways. In gonads and adrenal glands of both sexes, steroidogenic enzyme transcription, and steroids are different, as expected. Lipid profiles and steroidogenic enzyme proteins, HSD3B1 and CYP11A1, are affected within and near gonadal tumors. This documents organ-specific effects of chronic activin A elevation on lipid composition and cellular metabolism, in both histologically normal and tumor-affected areas. The potential for activin A to influence numerous steroidogenic processes should be considered in context and with spatial precision, particularly in relationship to pathologies.

Keywords: activin A, lipid metabolism, steroids, ovary, testis, adrenal gland, testosterone, mass spectrometry

Activin A is a widely distributed and functionally pleiotropic member of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily that orchestrates numerous aspects of organogenesis, including reproductive and endocrine system maintenance through both hormonal and local actions (1). The mature protein is 100% conserved between mouse and human, indicative of its central importance to mammalian physiology (2). Humans may be exposed to excess activin A bioactivity in myriad scenarios. Activin A can be abnormally elevated in utero, by preeclampsia, intra-amniotic infection, and by maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (3-6). Postnatally, activin A levels can be determined by conditions including hyperthyroidism, cancer and associated cachexia, renal infections, metabolic syndrome, and viral infections (eg, COVID-19) (7-9). The ongoing development of therapeutics inhibiting activin A bioactivity to treat conditions, including cachexia and pulmonary arterial hyperplasia, have been successful and demonstrate the involvement of elevated activin A in such pathologies (10-12). Developing knowledge of the impact of this state and the body-wide outcomes of therapeutic interventions is important for delivering appropriate medical care.

Significant evidence from mouse studies demonstrate that dysregulated activin A bioactivity impairs fetal development (13, 14). In fetal testes, activin A levels determine the specific composition and levels of steroids produced during a window critical for fetal masculinization (13, 14): both the absence (in the InhbaKO mouse (15)) or elevation (the InhaKO mouse (16), in which more activin is produced and can act unopposed by inhibins) of bioactivity impart dose-dependent effects on steroidogenic genes. Such observations underpin the present investigation of 3 different organs central to reproductive health in adult InhaKO mice: the testis, ovary, and adrenal glands. Here we investigate how both steroids and lipids, the foundations of cellular structure, signaling, and hormone formation, are affected in this model of chronically elevated activin A levels.

The activin A signaling protein homodimer comprises of 2 inhibin-βA subunits (encoded by Inhba). Its potent inhibitor, inhibin-α (INHA; encoded by Inha), is a heterodimer of inhibin-α and inhibin-βA subunits. Activin A is central to fetal testis development and function: intratesticular levels of Inhba transcripts surge during the window of masculinization (in mice, embryonic (E) 12-E15; in humans, weeks 8-14 of gestation (17)), regulating the proliferation and steroidogenic capacity of cell types involved in androgen production (13, 18, 19). This includes promoting proliferation of the Sertoli cells which form the germline niche and ultimately determine the potential sperm output in adult life. Thus, perturbations to activin A levels during this sensitive time of gestation may have lasting consequences on reproductive health and fertility. For instance, in both Inhba and Inha fetal testes, there is an inverse and dose-dependent impact of activin A on the ratio of germ cells to Sertoli cells (13). In addition, the measurement of elevated follicle-stimulating hormone and reduced inhibin B as a hallmark of male infertility (20) suggests that men with this condition may be chronically exposed to the effects of elevated activin A.

In addition to influencing normal development and function, chronic exposure to elevated activin A bioactivity has the well-documented effect of driving somatic cell tumors in mice lacking the mature Inha subunit coding sequence (InhaKO (16, 21)). Adult InhaKO males exhibit an approximately 40-fold increase in intratesticular activin A by 8 weeks of age, and 13.5-fold increase in serum activin A at 7-12 weeks of age. InhaKO females have a 19-fold increase in serum activin A at 10-20 weeks of age (21, 22). Formation of testicular tumors is accompanied by an approximately 40-fold increase in circulating activin A compared with wild type (WT) (22). The formation of gonadal stromal cell tumors and ovarian granulosa cell hyperplasia in adults, evident by 8 weeks of age, is followed by muscle wasting and cachexia. Gonadectomized InhaKO mice develop tumors within the adrenal cortex approximately 4 weeks later, followed by hyperplasia of the spleen and stomach lining (21). A new mouse strain, Inha R332A, synthesizes a mutant inhibin-α subunit that can dimerize with an inhibin-beta subunit to form activin proteins, so that activin dimers are not overproduced; however, the inhibin subunit is not cleaved to form a mature, functional protein that blocks activin signaling. Because these mice lack gonadal tumors and do not develop cachexia, it is now evident that outcomes documented in the original Inha mouse strain are due to elevated activin A (23). In addition to driving somatic cell tumor formation, the impact of activin A on immune cells is well-documented and its altered bioactivity changes the adult testis immune profile (24-27). As so many physiological parameters are influenced by activin A, the mechanisms underlying these outcomes are of high interest. A recent analysis of the testes tubules in InhaKO mice testes with tumors revealed that spermatogonial stem cell numbers are increased immediately proximal to the tumors, and provided evidence of an abnormal steroidogenic transcriptional landscape (28). Thus, the impact of excess activin A on steroid hormone levels is likely to be a key mechanism by which reproductive organs are affected.

There is limited information about how elevated activin A affects steroid concentrations and lipid composition within most tissues. In fetal testes of the InhbaKO mice which lack activin A, lipid droplets (LDs) accumulate, and steroidogenesis is dysregulated such that androstenedione (A4) conversion to testosterone (T) is blunted, and T levels are significantly reduced at E17.5 (14); activin A is selectively required to stimulate production in Sertoli cells of the enzymes that convert A4 to T. In InhaKO mice, with unopposed activin A, emergence of the steroidogenic precursor Leydig cells is impaired, and this also suppresses production of A4, T, and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by altering a different cohort of transcripts encoding steroidogenic enzymes (13).

Current data indicate that activin A levels modulate cellular signaling and the production of endocrine factors selectively within a niche, thereby determining cellular differentiation and function. We hypothesized that modulation of lipid composition is another important, associated outcome of excess activin A and that tissues other than the testis may be similarly affected in this condition. To elucidate the functional effects of chronic activin A elevation on adult reproductive organs (Fig. S1 (29)), this study capitalizes on the established mouse model (InhaKO) in which activin A is produced and acts unopposed by its potent inhibitor, inhibin α. Employing a broad suite of experimental approaches to assess features relating to lipid deposition, cellular metabolism, and steroidogenesis, we interrogated the testis, ovary, and adrenal glands of InhaKO mice to evaluate what lipid, steroid, and metabolic pathways are perturbed by excess activin A. These outcomes have implications for the intertwining reproductive axes, but must be considered as highly relevant for other organs in which the highly conserved activin A protein and members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily govern health and disease.

Materials and Methods

Animal Experimentation

All mouse experimentation was approved by the Monash Ethics Committee (MMCB/2020/06) and performed in accordance with the current Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. Transgenic mice containing a knockout allele for Inha (16) were maintained through heterozygote breeding. Mice were housed in a 12 hours light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. Reproductively mature WT and knockout mice (termed InhaKO) littermates were humanely sacrificed between 45 and 56 days of age by cervical dislocation, prior to the age at which gonadal tumors cause overt illness. Testes were excised and cleared of the epididymis. Adrenal glands and ovaries were collected; excess fat and Fallopian material were removed prior to processing for downstream analyses.

Tissue Homogenization

Isolated testes, ovaries, and adrenal glands were weighed, snap frozen on dry ice, and homogenized in homogenization buffer (ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline [pH 7.4] containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin [wt/v; Sigma-Aldrich] and 5 mM EDTA [Merk Millipore, Germany]). Testes were homogenized in 800 µL of buffer using a Bio-Gen PRO200 homogenizer (ProScientific), and ovaries and adrenals manually homogenized in 150 µL using a mortar and pestle. Samples were clarified by centrifugation at 1000g at 4 °C for 10 minutes, and the supernatant snap frozen on dry ice.

Oil Red O Staining and Quantification

Tissues (testis: WT, n = 3 and InhaKO, n = 5; ovary: WT, n = 4 and InhaKO, n = 3; adrenal glands: WT, n = 3 and InhaKO, n = 6) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (Alfa Aesar, USA) overnight at 4 °C, then cryopreserved in 30% sucrose (wt/vol; Merck Millipore, Germany) at 4 °C for 5 days, embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium (Tissuetek), and 7-µm sections thaw-mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific) for histological examination. Oil Red O staining was performed by the Monash Histology Platform Facility (MHPF) to identify LDs (14). Images were obtained using an Aperio Imagescope (MHPF), and analysis conducted using QuPath V 3.0 (30) and Fiji (31). In an area containing approximately 2 seminiferous tubules, the level of red signal (Oil Red O) was identified in sections from WT and InhaKO testes. In InhaKO testes, tumorigenic (TM) regions were identified, and representative images taken in the TM regions, tumor-associated tubules (TATs), and morphologically normal (N) regions. Images were taken radially from the tumor, and where possible at least 2 sets of images taken from each tumor extending in opposing directions so that the same LDs were not measured twice. Data were averaged per testis. Blue signal was used as a normalization control to represent the nuclear area.

Mass-Spectrometric Methods

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry lipid profiling

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to determine the lipid content of WT (n = 7) and InhaKO (n = 6) testis homogenates using standard protocols (32). Acetonitrile, propan-2-ol and water were purchased from ChemSupply, Australia. Formic acid, ammonium formate, EquiSPLASH, and UltimateSPLASH ONE stable isotope–labeled lipid standards were from Sigma-Aldrich, Australia. All reagents used were LC-MS grade.

Homogenate containing 1 mg of tissue was made up to 30 µL in homogenization buffer. A 150-µL aliquot of extraction solution (99:99:2 v/v/v acetonitrile/propan-2-ol/EquiSPLASH) was combined with each sample, then sonicated for 10 minutes and incubated at −20 °C for 1 hour. Following centrifugation in a biofuge Pico for 15 minutes at 13 000 RPM, supernatant was retrieved for LC-MS analysis. A pooled biological quality control (PBQC) was generated from 20 µL of each sample. Homogenization buffer (30 µL) treated in the same manner as the samples served as an extraction blank. Standards for retention time calibration were generated by addition of 1 µL of UltimateSPLASH ONE to 200 µL of PBQC.

LC separation of samples was performed with an Acquity iClass UPLC (Waters corporation, USA), using a 100 mm length and 2.1 mm inner diameter Waters Acquity CSH Premier C18 column at 55 °C. The autosampler chamber was maintained at 8 °C. LC solvents were 60% acetonitrile (mobile phase A) and 90% isopropyl alcohol with 10% acetonitrile (mobile phase B) both containing 10 mM ammonium formate and 1% formic acid. The gradient used for separation is provided in Table S1 (29).

Mass spectrometric analyses on the separated lipids was performed using an Xevo G2-XS Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, UK). Centroid data were acquired in both positive and negative ion modes with a scan time of 0.15 seconds. PBQC was utilized to equilibrate the system, and additionally run every 6 samples. Testis homogenates were analyzed in a random order to reduce potential bias.

For analysis, retention times of EquiSplash and UltimeSPLASH ONE lipid standards were used for retention time calibration of an in-house lipid database containing over 1100 lipids (32). Analytical lipids were filtered such that lipids with a signal to noise ratio less than 10, and a percentage of covariance more than 100 were excluded from further analysis in MetaboAnalyst Version 6.0 (33). Ion areas were uploaded into MetaboAnalyst, subjected to normalization by median and log transformed (base 10) for analysis. Lipid nomenclature is based on the 2009 update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids (34). SM, PC, PS, or PI refer to sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositols respectively. Numbers given in brackets indicate fatty acid composition. and “O-” before fatty acid represents a lipid with an ether linkage.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging

Unfixed testes were embedded in 8% gelatin (wt/vol in Milli-Q water; Sigma) and snap frozen in hexane (Sigma) cooled by dry ice. Tissues were prepared for mass spectrometry imaging as detailed previously (35). In brief, 10-µm sections were thaw-mounted onto indium tin oxide coated IntelliSlides (Bruker, Germany), with 2 biologically independent WT and 2 independent InhaKO testes mounted on 1 slide. Each slide was then washed in 4 °C 150 mM ammonium formate (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia), dried in a vacuum desiccator, sublimated with 7.5 mg of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB; Sigma-Aldrich, Australia), and recrystalized at 60 °C. Tissues were imaged in positive (m/z 300-1200) and negative ion mode (m/z 250-1200) using a timsTOF fleX mass spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) at 20-µm step size, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for coregistration.

LC-MS metabolomic analysis

A testis homogenate containing 5 mg of tissue was used for metabolomic analysis (testis, n = 6 WT, n = 6 InhaKO; adrenal n = 3 per genotype). Samples were extracted in solvent (1:1 acetonitrile:methanol) containing internal standards. Mixtures were briefly vortexed, centrifuged, and supernatant processed for LC-MS analysis on a HILIC-LC-Orbitrap-MS platform, utilizing a semi-untargeted profiling approach. A pooled biological quality control was generated from a combination of sample extracts and run every 5 samples. Masses were matched to an in-house polar metabolite library (Metabolomics Australia), and analyzed using Metaboanalyst Version 6.0. Data were subjected to normalization by median and log transformation (base 10). Joint pathway analysis in Metaboanalyst was performed using all integrated pathways, hypergeometric testing, and unweighted analysis.

LC-MS quantification of intragonadal steroids

Using testis (n = 7 WT, n = 6 InhaKO) and ovary homogenates (n = 5 WT, n = 6 InhaKO), steroid hormones, progesterone (P4), A4, T, 11-keto testosterone, 3α-androstanediol, 3β-androstanediol, estradiol, estrone (E1), and DHT, were quantified using LC-MS as previously detailed (14, 36) and normalized to tissue weight (mg). Limit of quantitation is indicated as a dotted line on graphs, and samples below the limit of detection given a value equal to limit of detection/√2 for statistical analysis (37).

Steroidogenic Transcript Analysis

RNA extraction

Snap frozen gonads and adrenals were homogenized in Trizol (500 µL [testis] or 250 µL [ovary or adrenal]; Invitrogen) using a mortar and pestle, and RNA extracted using standard protocols. Contaminating DNA was removed using a Qiagen DNA-free kit (Invitrogen) per manufacturer's instructions. RNA was resuspended in RNase free ultrapure water and quantified using a nanophotometer (Thermofisher).

Tumor microdissection

As previously described (28), tissue was collected from adult InhaWT and KO testes (53-55 days old). Briefly, InhaKO testes featuring focally invasive tumors were decapsulated and the tubules gently teased apart to reveal tumor regions that were readily identifiable by the presence of vascularization. Three discrete regions were microdissected under a light microscope. First InhaKO N seminiferous tubules were collected from areas distant from tumor regions, then TATs bordering the tumors (within ∼1-3 tubule diameters) were collected, finally revealing the tumor (TM). Samples were snap frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C prior to bulk RNAseq analyses, results previously described (28). In the present manuscript, this pre-existing dataset was interrogated to examine genes specifically related to steroidogenesis.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

cDNA was generated from 500 ng (testis) or 100 ng (ovary and adrenal gland) of RNA using the Superscript III system (Invitrogen), per standard protocols with both random and oligo-dT primers (Promega). cDNA was diluted 1:20 in Ultrapure water and amplified in a reaction volume of 10 µL containing 0.5 µM forward and reverse primers (Table 1) with Power SYBR green Mastermix (Applied Biosystems), using a QuantStudio 6 thermal cycler with an annealing temperature of 62 °C. RNA incubated without Superscript enzyme served as a reverse transcription negative control. Data analysis used the ΔCT method, with Rplp0 as the housekeeper. Data are presented as transcript quantity relative to housekeeper (2−ΔCT). A minimum of n = 5 biologically independent WT and n = 5 InhaKO adrenal glands were used for overall comparison, and a minimum of n = 3 biologically independent adrenal glands from each genotype were used for sex-specific analysis, and for ovary and testis gene expression studies.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Gene | Accession number | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star | NM_011485.5 | TGCCCATCATTTCATTCATCCT | AAAAGCGGTTTCTCACTCTCC |

| Cyp11a1 | NM_001346787.1 | ACATGGCCAAGATGGTACAGT | ACGAAGCACCAGGTCATTCAC |

| Cyp17a1 | NM_007809.3 | GCCCAAGTCAAAGACACCTAA | GTACCCAGGCGAAGAGAATA |

| Srd5a1 | NM_175283.3 | TGGTGTTTGCTCTGTTCACCCT | GCATGGACAGCACACTAAAGCA |

| Cyp19a1 | NM_007810.4 | CGGAAGAATGCACAGGCTCG | GCCCAAAGCCAAAAGGCTGA |

| Cyp11b1 | NM_001033229.3 | TATCGAGAGCTGGCAGAGGGT | TGCTGAACATCTGGGTTCCG |

| Hsd3b1 | NM_001304800.1 | TGGACAAAGTATTCCGACCAG | GGCACACTTGCTTGAACACAG |

| Hsd17b1 | NM_010475.2 | TCCTGGCTCCTTGGAGATACT | TCTAGCGGCCCAAACAAGC |

| Hsd17b3 | NM_008291.3 | TGTTGTACTTATTAGCCGGACAC | AGATTCTGGCTCTCACCGGA |

| Rplp0 | NM_007475 | GGACCCGAGAAGACCTCCTT | GCACATCACTCAGAATTTCAATGG |

Gene names, accession number, and primers utilized in this study.

Immunohistochemistry

Organs (n ≥ 3 for each genotype and each organ) were immersed in Bouins' fixation solution (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight, and rinsed thrice in 80% ethanol (vol:vol; Chem-Supply) before dehydration and embedding in paraffin wax. Sections of 5 µm were placed on Superfrost Plus slides, then baked at 60 °C for 20 minutes before dewaxing in 2 changes of histolene (Muraban Laboratories, NSW Australia), rehydration in a decreasing ethanol gradient (100%, 100%, 95%, 70%), and 1 wash in milli-Q water. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed in 100 mM citric acid (pH 6.0; Merk Millipore Australia) by microwaving at 800 W for 4 minutes, 450 W for 6 minutes, and then allowed to cool at room temperature for a further 20 minutes. Following 3 washes in Tris buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4), an endogenous peroxidase block was performed with 3% H2O2 (Merk Millipore Germany), sections rinsed 3 times in TBS, and further blocked for 1 hour in TBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5% serum of the secondary antibody host (Sigma; rabbit or goat as applicable); for activin A immunolocalization, 4% Mouse-on-Mouse block (Vector Laboratories) was included. Primary antibody was applied overnight at 4 °C in a humidified environment (0.2 µg/mL HSD3B1, [Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, sc30820, RRID:AB_2279878]; 1:400 rabbit anti-CYP11A1 [kind gift of Prof Dagmar Wilhelm, University of Melbourne (38), RRID:AB_3676670]; 6.5 µg/mL mouse antiactivin A, [E4 clone, Oxford-Brookes University, RRID:AB_2801574]). Following 3 washes in TBS, secondary antibody was applied for 1 hour at room temperature (1:500, either biotinylated goat anti-rabbit [Invitrogen, RRID:AB_2533969] or rabbit antigoat [DAKO, RRID:AB_3676677]). Signal was amplified using Vectastain Elite ABC (Vector Laboratories), and visualized by application of 3-3′-diaminobenzidine (DAKO). Nuclei were visualized with Harris' haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich), tissue sections dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol, followed by 2 changes in histolene, and mounted in DPX medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were obtained as previously described.

Statistical Analysis and Data Representation

Data analysis and graphical representation performed using GraphPad Prism V 9.3.0 (La Jolla, San Diego, USA) unless otherwise indicated. All data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilks test before statistical analysis. Data containing 2 groups were assessed using a t-test (parametric) or Mann–Whitney U test (nonparametric), and data containing 3 or more groups assessed using a 1-way analysis of variance (parametric) or Kruskal–Wallis (nonparametric) test followed by Tukey's or Dunn's post hoc testing respectively. Lipidomic and metabolomic analyses and data representation were performed using MetaboAnalyst V6.0 (33). Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as mean ± SD; individual data points represent biologically independent samples. A minimum of n = 3 biologically independent replicates per group were used unless stated otherwise.

Results

Testicular Lipid Droplets Accumulated in Morphologically Abnormal Regions

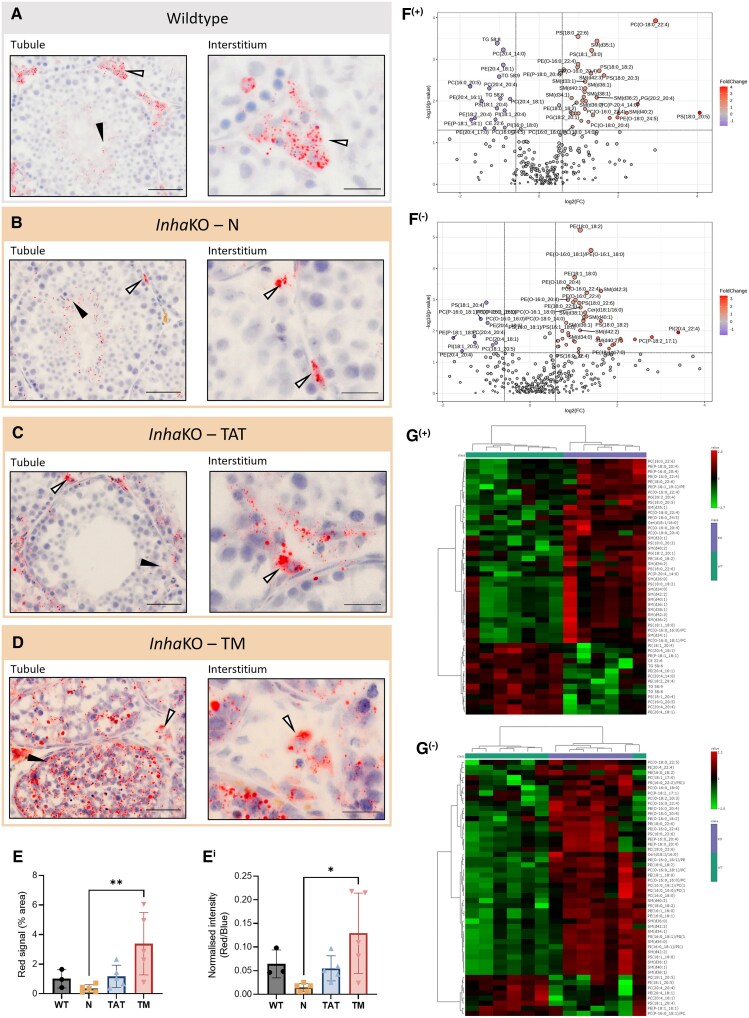

Oil Red O staining identified lipid deposition in adult mouse testes (Fig. 1A-1D), with distinct results for testes of each genotype. In WT adult testes (Fig. 1A), LDs are observed in the cytoplasm of cells in interstitial areas. The prominence of LDs within Leydig cells is consistent with their role as the site of de novo steroid production, while peritubular cells did not display this stain. LDs were much less abundant inside the seminiferous tubules. The spread of LDs appears altered in morphologically N regions of InhaKO testes, particularly in the interstitial regions (Fig. 1B). TATs (adjacent to established tumors) appear to have a higher number of LDs (Fig. 1C), in cells present both in the interstitium and inside tubules. However, no statistical differences were observed between N and TAT regions in the percentage area of red signal (P = .7184) and the normalized area of the red signal (P = .5825). Within focal lesions (TM, evidenced by focal hemorrhagia), LDs were highly abundant (Fig. 1D). While the tumor burden is heterogenous across samples, LDs were consistently abundant within morphologically abnormal regions (Fig. S2 (29)). Results were similar for testes of the same genotype. The percentage area of red signal was significantly higher in the TM regions vs N (Fig. 1E; P = .0077), and the area of red signal remained significantly elevated when normalized to the area occupied by cell nuclei (Fig. 1Ei; P = .0115). This indicates the testis tumors to be significantly more lipid rich than the surrounding morphologically N testis tissue.

Figure 1.

Testicular lipid profile is affected by chronic activin A excess. (A) In WT testes (n = 3), lipid droplet (LDs) are prominent in in spermatids (tubule) and Leydig cells (interstitium). In InhaKO testes (n = 5), LDs are present in spermatids in “normal” tubules (N) and in the interstitium (B). Tubules adjacent to tumors (TATs) exhibit lipid droplets in the interstitium and tubule perimeter (C). Lipid droplets are abundant through tumorigenic regions (TM, D). Scale bars represent 50 µm (tubule) and 20 µm (interstitium). Black arrowheads indicate intratubular lipid droplet accumulations, and white arrowheads indicate interstitial lipid droplets. (E) Red signal (lipid droplets) is significantly elevated in the TM regions of InhaKO mice compared with N (P = .0077), including when normalized to nuclear area (Ei; P = .0115). (F) LC-MS lipidomic analysis identified differentially abundant lipids between WT (n = 7) and InhaKO (n = 6) whole testes (fold-change [FC] 1.5, P < .05). (G) The top 50 differentially abundant lipids distinguish WT and InhaKO testes (green and purple, respectively). In F and G, (+) and (−) indicate data acquired in positive and negative ion mode, respectively.

Whole Testis Lipid Profile Is Modulated by Excess Activin A

Testis lipids altered by excess activin A bioactivity were identified using LC-MS identified in whole testis homogenates. In InhaKO testes, 35 and 42 lipids were significantly higher using positive and negative ion modes, respectively, and 17 and 9 lipids were significantly lower (Fig. 1F). The top 50 lipids from each of positive and negative ion detection modes were subjected to hierarchical clustering (Fig. 1G). WT and InhaKO samples clustered separately, displaying distinct lipid profiles. All significantly altered lipids are listed in Table S2 (29).

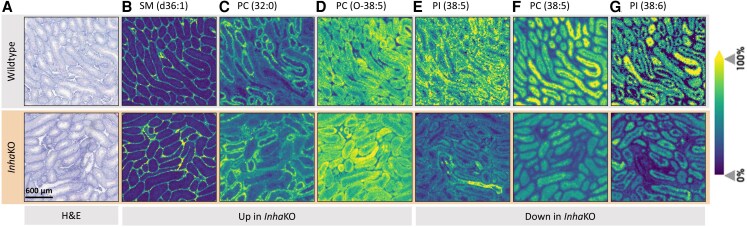

Differentially Abundant Lipids Display Varied Spatial Distributions

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) was employed to clarify the spatial distribution of the lipids determined to be differentially abundant in WT vs InhaKO testes, providing an indication of the cell types most likely to be impacted. Selected examples of ions of biological relevance (determined by signal intensity, localization, and consistency across biological replicates) are presented in Fig. 2. Within morphologically N tissue sections, differentially abundant lipids are localized to the interstitium (Fig. 2B; comprising Leydig, peritubular myoid, endothelial, and immune cells), within the seminiferous tubule perimeter (Fig. 2C-2E; Sertoli cells, spermatogonial stem cells, and spermatogonia), and seminiferous tubule interior (Fig. 2F and 2G; spermatocytes and spermatids). Some lipids display a profile indicative of changing abundance relative to stage of the seminiferous cycle (Fig. 2C, 2F, and 2G).

Figure 2.

MALDI-MSI reveals intratesticular localization of differentially abundant lipids in morphologically normal regions of InhaKO testes. Lipids altered in the InhaKO (n = 2) testes compared with WT (n = 2) are visualized in the interstitial space (B), tubule perimeter (C, D, E), and intratubular space (F, G). A stage-specific distribution of certain tubular lipids is apparent (C, F, G). Section images showing (A) hematoxylin and eosin staining and (B-G) each identified lipid, m/z ± 15 mDa: (B) SM (d36:1), m/z = 731.6062, fold change InhaKO vs WT (FC) = 2.336 (P = .0048); (C) PC (32:0), m/z = 734.5694 FC = 1.779 (P = .0277); (D) PC (O-38:5), m/z = 794.6058, FC = 4.212 (P = .0180); (E) PI (38:5), m/z = 883.5342, FC = 0.546 (P = .0169); (F) PC (38:5), m/z = 808.5851, FC = 0.584 (P = .0242); (G) PI (38:6), m/z = 881.5186, FC = 0.418 (P = .0237). Scale bar represents 600 µm.

Abnormal Lipid Distributions Occur Within and Surrounding Activin A Lesions

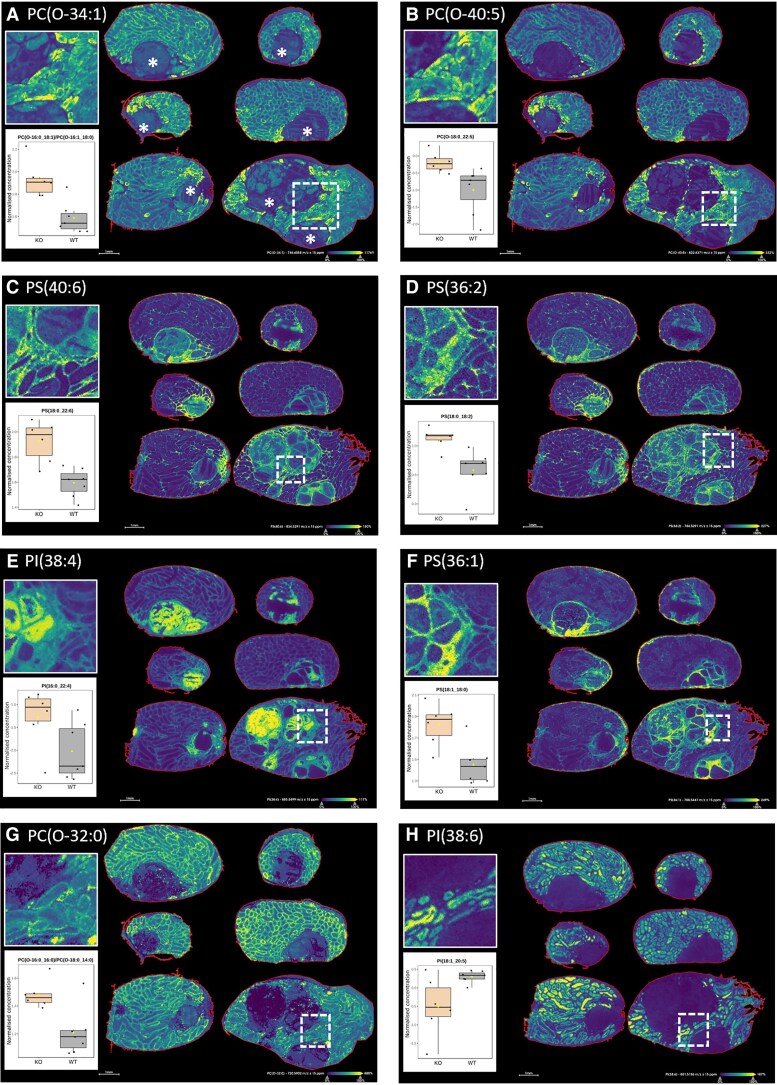

MALDI-MSI confirms an altered distribution of lipids identified as significantly different by LC-MS within established focal lesions and the surrounding tissue of InhaKO testes (P < .05; for Fig. 3E: PI(16:0_22:4), P = .056). Figure 3 shows the MALDI-MSI and tentative lipid identification for the visualized m/z alongside the normalized peak areas of individual lipids identified in whole testis homogenates through LC-MS (Figs. 1F and 1G) which correspond to the sum notation. We have presented these 2 separate but complementary techniques within each panel of Fig. 3 to highlight their individual strengths. For instance, panels F-H show robust concordance between the techniques; however, for panels A-E, MALDI-MSI reveals localized differences not immediately evident in LC-MS whole testis homogenate results.

Figure 3.

MALDI-MSI and whole testis homogenates identify differentially abundant lipids in InhaKO vs WT testes, shown in relationship to tumor proximity. Testis section images show individual lipids, m/z ± 15 ppm, and tentative lipid identification. Inset box and whisker plots show MetaboAnalyst-normalized LC-MS peak areas from whole testis homogenates. White dotted box indicates enlarged area shown above plots. Tumor regions for each of the 6 testis sections are indicated in A by white asterisks. (A) PC(O-34:1), m/z = 746.6058, inset PC(O-16:0_18:1)/PC(O-16:1_18:0); (B) PC(O-40:5), m/z = 822.6371, inset PC(O-18:0_22:5); (C) PS(40:6), m/z = 834.5291, inset PS(18:0_22:6); (D) PS(36:2), m/z = 786.5291, inset PS(18:0_18:2); (E) PI(38:4), m/z = 885.5499, inset PI(16:0_22:4); (F) PS(36:1), m/z = 788.5447, inset PS(18:1_18:0); (G) PC(O-32:0), m/z = 720.5902, inset PC(O-16:0_16:0)/PC(O-18:0_14:0); (H) PI(38:6), m/z = 881.5186, inset PI(18:1_20:5). Scale bars = 1 mm. N = 6 testes from n = 3 biologically independent mice. Each row contains 1 section from each of a pair of testes.

Discrete lipid species have differing patterns of localization in relation to the tumor. Some lipids are present within seminiferous tubules, and are increased in abundance within TATs (Fig. 3A and 3B), but are noticeably absent or reduced within the tumor proper. Other lipid species, present either in the interstitial space, or the seminiferous tubules of morphologically N tissue, are elevated within the TATs and the tumor (Fig. 3C and 3D), and some lipids appear almost exclusive to the tumor (Fig. 3E and 3F). In contrast, several lipids are highly abundant in surrounding tissue and are markedly reduced within the tumor (Fig. 3G and 3H). Notably, MALDI-MSI highlights the heterogeneity of these tumors, and reveals discrete lipid rich regions within the tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin of these sections is provided in Fig. S3 (29).

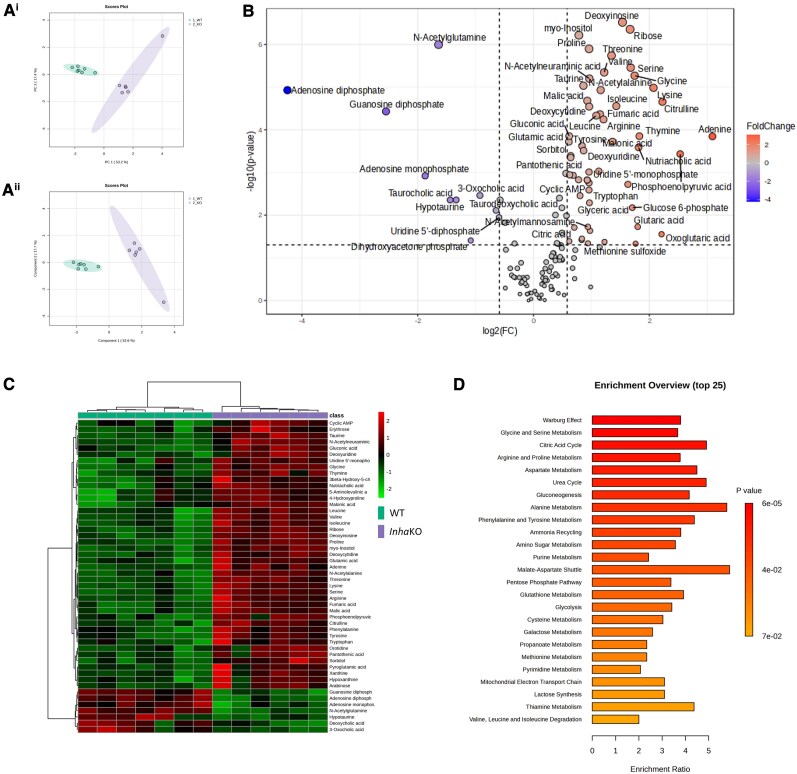

Excess Activin A perturbs Cellular Metabolism

LC-MS metabolomic analysis of whole testes revealed discrete profiles for InhaKO (purple) and WT (green) testes through data clustering (Fig. 4Ai, Aii). Fifty-four metabolites were significantly enriched in InhaKO testes, and 10 metabolites were reduced (Fig. 4B and 4C, Table S3 (29)). These changes are calculated to impact pathways including alanine metabolism and amino sugar metabolism, the urea cycle, phenylalanine and tyrosine metabolism, Warburg effect, the citric acid cycle, gluconeogenesis, and the malate–aspartate shuttle (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Excess activin A changes testicular metabolism. (A) PCA (Ai) and PLSDA (Aii) show discrete profiles of metabolites detected in WT (green, n = 7) and InhaKO (purple, n = 6) testes. (B) Fifty-four metabolites were significantly higher in InhaKO testes, and 10 were lower. (C) Heat map analysis shows hierarchical clustering and different profiles between the 2 genotypes. (D) Enrichment analysis showing the top 25 significantly enriched pathways represented by differentially abundant metabolites elevated in InhaKO testes.

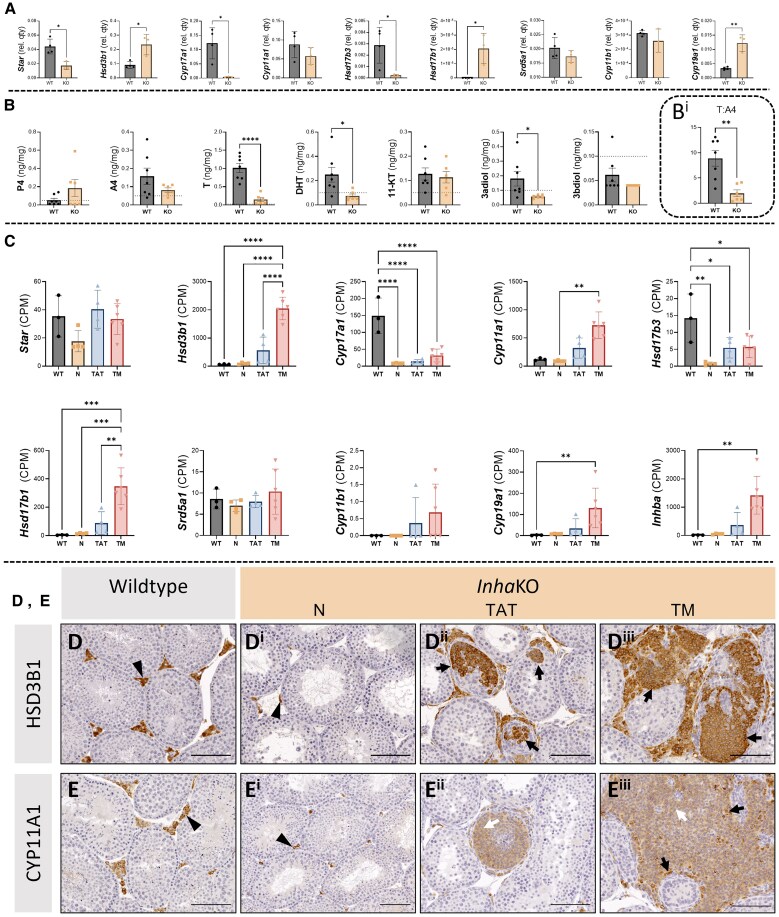

Steroidogenic Enzyme Transcripts and Hormonal Profiles Are Altered in InhaKO Testes

A selection of transcripts encoding proteins of central relevance to steroid production in Leydig cells were measured in whole WT and InhaKO testes (Fig. 5A) including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Star), hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenases 3β-1, 17β-3, 17β-1, (Hsd3b1, Hsd17b1, Hsd17b3), cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp17a1), cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp11a1), cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily b member 1 (Cyp11b1), and cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp19a1), and steroid-5-α-reductase (Srd5a1). In InhaKO testes, Star (P = .0103), Cyp17a1 (P = .0144), and Hsd17b3 (P = .0368), were significantly reduced relative to WT, while Hsd3b1 (P = .0121) and Cyp19a1 (P = .0017) were significantly increased. Cyp11a1 (P = .2361), and Srd5a1 (P = .2678) were not significantly altered.

Figure 5.

Chronic activin A elevation results in regionally altered testis steroid production. (A) Transcripts encoding steroidogenic enzymes measured by qRT-PCR. Graphs show mean ± SD transcript quantity normalized to Rplp0 in the whole WT (n = 4; grey) and InhaKO testis (n = 3; orange). (B) Intratesticular steroid levels. Mean ± SEM steroid hormone concentrations in WT (n = 6; grey) and InhaKO samples (n = 7; orange). Dashed line represents limit of quantitation. (Bi) T:A4 ratio is significantly lower in InhaKO compared to WT testes. (C) RNAseq of microdissected InhaKO and WT testes (data adapted from Whiley et al, 2023 (28)). Mean ± SD counts per million (CPM) of RNA-seq quantified transcripts. Morphologically normal (N), tumor associated tubules (TAT), and tumorigenic (TM), regions of the InhaKO testis demonstrate dysregulation of steroidogenic transcripts in comparison to wild-type (WT). Inhba, Hsd17b3, and Cyp11a1 from Whiley et al (2023) (28). (D) Immunoreactive HSD3B1 was identified in WT testis interstitial cells (black arrowhead). InhaKO testes exhibit fewer immunoreactive cells in the interstitium of morphologically normal regions (Di, black arrowhead). HSD3B1+ cells were identified in discrete patches inside seminiferous tubules, and within established focal lesions (Dii, Diii; black arrows). (E) Interstitial CYP11A1+ cells in the WT testis (black arrowhead). Fewer immunoreactive cells were visible in morphologically normal regions of InhaKO testes (Ei; black arrowhead), and signals of varying intensities could be seen within abnormal testis cords and focal lesions (Eii, Eiii, black and white arrows indicate greater and lower signal intensities, respectively). Scale bars represent 100 µm. Negative controls provided in Fig. S4 (29). Individual data points represent biologically independent replicates. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

Extending and confirming transcript data, LC-MS quantification of 7 steroid hormones in the homogenized WT and InhaKO testes (Fig. 5B) revealed 3 were significantly reduced in InhaKO testes: T (P < .0001), DHT (P = .0255), and 3α-androstanediol (P = .0122). Four other measured hormones were not different: P4 (P = .5425), A4 (P = .1602), 3β-androstanediol (P = .1923), and 11-keto testosterone (P = .6972). The T:A4 ratio (Fig. 5Bi) was significantly reduced in the InhaKO testes (1.983 vs 8.877; P = .0026), consistent with a block in the conversion of A4 to T due to the reduction Hsd17b3.

Proximity to the Gonadal Tumor Determines Local Steroidogenic Transcript and Protein Abundance

Previously reported RNA-seq analyses (28) revealed distinct transcriptional landscapes of tissue from morphologically N, TATs, and TM regions in InhaKO testes. Figure 5C shows transcripts relating to steroid production, including several previously reported (Inhba, Cyp11a1, Hsd17b3 (28)) that are presented here again because of their relevance to this analysis. Inhba was more highly expressed in TM vs WT (P = .0039), reflecting a local microenvironment of high activin A in tumor regions (16, 28). Transcripts encoding several steroidogenic enzymes were present at higher levels in TM and TAT than in N and WT. Hsd3b1 was significantly elevated in TM vs WT, N, and TAT (P < .0001 for all). Cyp11a1 was only increased in TM vs N (P = .0023). Hsd17b1 was increased in TM vs WT (P = .0006), N (P = .0003), and TAT (P = .0028). Cyp19a1 was only higher in comparison to WT (P = .0047). Cyp17a1 transcripts were significantly lower in N, TAT, and TM vs WT (P < .0001 for all). Compared to WT, HSD17b3 was also reduced in N (P = .0020), TAT (P = .0393), and TM (P = .0301). Transcripts which were not significantly affected were Star (P = .0562), Srd5a1 (P = .5228), and Cyp11b1 (P = .2513).

HSD3B1 (Fig. 5D) and CYP11A1 (Fig. 5E) were identified using immunohistochemistry in Leydig cells of the WT (n ≥ 3) testis, but very different distributions of these proteins were observed in InhaKO testes (n ≥ 3). These proteins accumulated within the testicular cords in proximity to regions of histological abnormality near tumors (Fig. 5Di-iii and 5Ei-iii, consistent with previous reports (28)), and CYP11A1 displayed a notably heterogenous signal intensity within these morphologically abnormal regions (identified by black and white arrows).

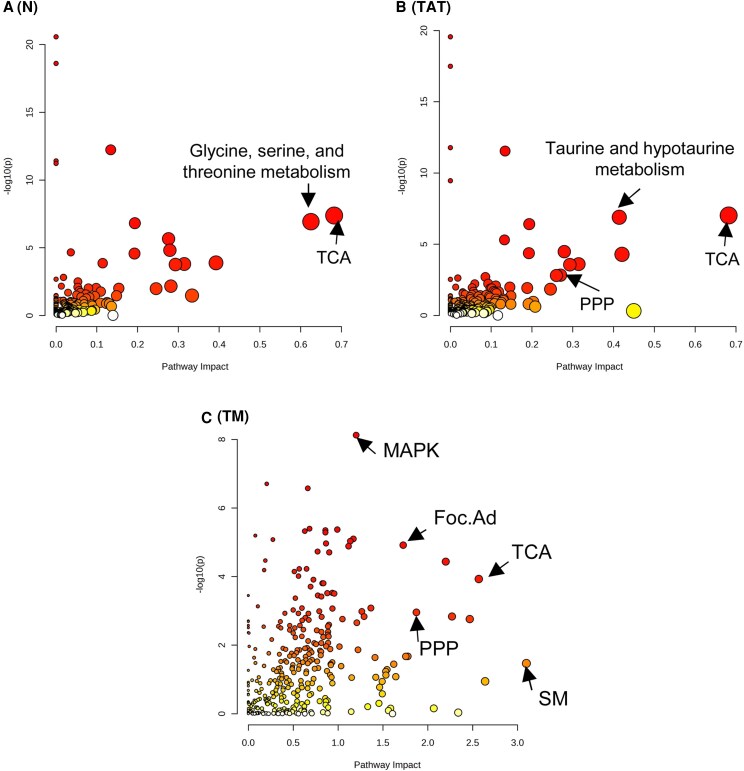

Lipid Metabolism Pathways Are Significantly Enriched in Proximity to Tumors

Joint-pathway analysis was conducted with MetaboAnalyst using the differentially expressed genes unique to each region: N, TATs, and TM regions, in conjunction with all differentially abundant metabolites in InhaKO testes. The significantly enriched pathways are listed in Table S4 (29). The “impact” score indicates the degree to which the pathway is affected by the significantly altered genes and metabolites; the greater the number, the greater the effect on that pathway. Here we discuss pathways affected with an impact of ≥0.4.

In morphologically N regions of the InhaKO testis, 39 pathways were significantly enriched, with 2 having an impact score ≥0.4 (Fig. 6A). The most impacted and significantly enriched pathways were citrate cycle (TCA; P < .0001, impact = 0.68), and glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (P < .001, impact = 0.63). In TATs, 47 pathways were enriched, with 3 having an impact score ≥0.4 (Figure 6B). The most impacted, significantly enriched pathways were TCA (P < .0001, impact = 0.68), glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (P < .0001, impact = 0.42), and taurine and hypotaurine metabolism (P < .0001, impact = 0.41). In the TM region, 143 pathways were significantly enriched, with 114 having an impact score ≥0.4 (Fig. 6C). The 5 most impacted, significantly enriched pathways were sphingolipid metabolism (P = .0340, impact = 3.1), TCA (P < .0001, impact = 2.64), phosphatidylinositol signaling system (P < .01, impact = 2.47), purine metabolism (P = .0015, impact = 2.27), and glycolysis or gluconeogenesis (P < .001, impact = 2.20).

Figure 6.

Proximity to the InhaKO tumors influences the pathways enriched in gene expression and cell metabolism relative to WT testes. Visual representation of joint pathway analysis utilizing the differentially abundant whole testis metabolites in conjunction with unique DEGs of the morphologically normal regions (A; 104 DEGs), tumor associated tubules (B; 109 DEGs), and the tumorigenic regions (C; 6070 DEGs) of InhaKO testes. TCA, the citric acid cycle; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; MAPK, MAP kinase signaling pathway; Foc.Ad, focal adhesions; SM, sphingolipid metabolism.

Pathway analysis of the TM region sheds further light on their lipid metabolism and steroid production (Table S4 (29)). In general, lipid-related pathways were predominantly enriched in the TM regions, and not N or TATs. Fig. 6C). Sphingolipid metabolism is only enriched with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) unique to the TM region, and not in morphologically N regions (P = .3818), or TAT (P = .4184), as is the sphingolipid signaling pathway (TM, P = .0008, impact 0.6; N, P = .6008; TAT, P = .6448). Glycerolipid metabolism is also significantly enriched only in the TM regions (P = .03584, impact 1.62; N, P = .1371; TAT; 0.1656) Similarly, the phospholipase D signaling pathway is enriched in the TM region (P = .0130, impact = 0.91), but not in N (P = .6505) and TAT (P = .1128).

Enrichment of hormonal terms predominantly in the TM regions (Table S4 (29)) is in accord with the strikingly different local steroidogenic environment of tumors arising due to elevated activin A. This is evidenced by enrichment of cortisol synthesis and secretion (N, P = .0925; TAT = P .0219, impact = 0.12; TM, P < .0001, impact = 0.56), aldosterone synthesis and secretion (N, P = .17415; TAT, P = .0129; impact = 0.10; TM, P = .0298, impact = 0.36), and the estrogen signaling pathway (N, P = .6087; TAT, P = .0874; TM P = .0465, impact = 0.78).

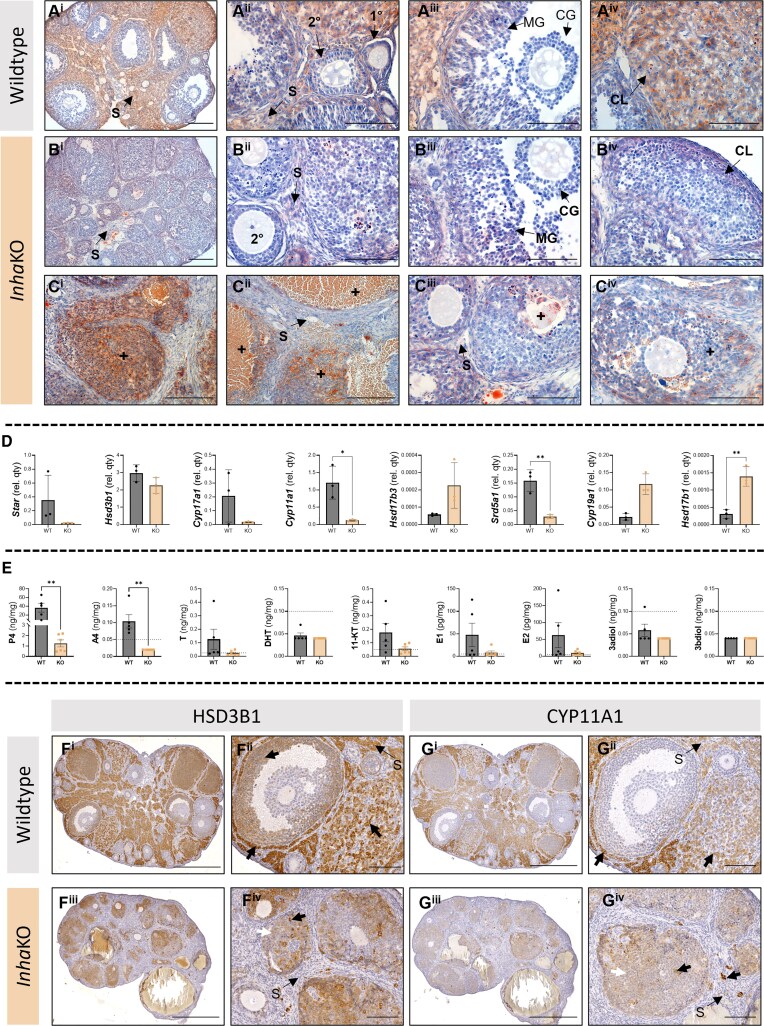

Ovarian Lipids and Steroids Are Also Impacted by Excess Activin A

Extending our study to the female gonad, we also examined LDs and steroids in ovaries (Fig. 7). In WT ovaries, LDs detected using Oil Red O are abundant throughout the highly steroidogenic WT stroma (Fig. 7Ai). They were observed in granulosa cells of primary and secondary follicles, in antral follicles, and were readily observed in mural, but not cumulus, granulosa cells (Fig. 7Aii and 7Aiii). Oocytes rarely had LDs, while corpora lutea display robust levels of LD accumulation (Fig. 7Aiv). In InhaKO ovaries, ORO staining intensity was reduced in stromal regions compared to in WT (Fig. 7Bi). In morphologically N regions, granulosa cells of developing follicles contained LDs (Fig. 7Bii). In antral follicles (Fig. 7Biii), the Oil Red O signal appears reduced in the mural granulosa cells, and presumptive corpora lutea (Fig. 7Biii and 7Biv). Like the InhaKO testis, LDs were abundant near regions of hemorrhage and in abnormal follicles (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Abnormal lipid deposition and steroid production phenotype in InhaKO ovaries. (A) In WT ovaries (n = 4), Oil Red O staining identifies lipid deposition in the stroma (S; Ai), granulosa cells of primary and secondary follicles (1°, 2°, respectively; Aii), and in the mural, but not cumulus, granulosa cells of the antral follicle (MG, CG, respectively; Aiii). The corpus luteum (CL) is rich in lipid droplets (Aiv). (B) The InhaKO ovarian stroma (n = 3) appears to have lower density of Oil Red O accumulation (Bi, Cii, Ciii). Secondary follicles (Bii) contain Oil Red O–identified lipid droplets. The mural granulosa cells appear to have fewer lipid droplets in antral follicles than WT (Biii). The corpus luteum also has reduced Oil Red accumulation (Biv). (C) Morphologically abnormal regions (+) of InhaKO ovaries accumulate lipid droplets (Ci-Ciii are biologically independent samples). (D) Steroidogenic transcripts measured by qRT-PCR. Mean ± SD transcript level normalized to Rplp0 in WT (grey) and InhaKO ovary (orange). (E) Intraovarian hormone concentrations. Mean ± SEM in WT (grey) and InhaKO ovary (orange). (F) HSD3B1 is observed in the stroma (S), corpora lutea, thecal, and mural granulosa cells (black arrows) of the WT ovary (Fi, Fii). In the InhaKO (Fiii, Fiv), HSD3B1 signal is observed in morphologically abnormal follicles at varying signal intensity (black and white arrows) and appears much reduced in the stroma comparted to WT. (G) CYP11a1 signal is observed in the stroma, thecal cells, and corpora lutea of the WT ovary (Gi, Gii). Variable CYP11a1 signal intensity is seen in morphologically abnormal follicles of the InhaKO ovary, and in some stromal cells (Giii, Giv; black and white arrowheads indicate differing signal intensity). Negative controls are provided in Fig. S4 (29). Scale bars represent 500 µm (Fi, Fiii, Gi, Giii), 200 µm (Ai, Bi, Ci, Cii, Ciii); 100 µm (Aii, Aiii, Aiv, Biii, Biv, Ci-iv, Fii, Fiv, Gii, Giv). *P < .05, **P < .01. Individual data points represent biologically independent replicates.

The impact of excess activin A on transcripts relating to steroid production in InhaKO ovaries compared with WT was documented (Fig. 7D). Cyp11a1 (P = .0165) and Srd5a1 (P = .0052) were significantly lower, while Hsd17b1 was significantly higher (P = .0037). Other transcripts that did not reach statistical significance included Star (P = .1931), Hsd3b1 (P = .1387), Cyp17a1 (P = .1577), Hsd17b3 (P = .0917), and Cyp19a1 (P = .1000). As these mice were not sacrificed at a specific stage of the estrous cycle, cyclical variation may mask some transcriptional effects in the InhaKO mouse ovary (39).

Levels of 2 steroid hormones, P4 (P = .0037) and A4 (P = .0022), were significantly reduced in the InhaKO ovaries compared with WT (Fig. 7E). No other steroid hormones reached statistical significance (T [P = .1407], 11-keto testosterone [P = .0922], estrone [P = .3052; E1], and estradiol [P = .1472; E2], DHT [P = .4545], 3α-androstanediol [P = .1818], and 3β-androstanediol [P > .9999]).

Immunodetection of HSD3B1 and CYP11A1 supports a regionalized effect of activin A on ovarian steroidogenesis. In WT ovaries, the HSD3B1 signal is intense in stroma, thecal cells, corpora lutea, and mural, but not cumulus, granulosa cells (Fig. 7Fi and 7Fii). HSD3B1 immunolocalization was drastically altered in the InhaKO ovary (Fig. 7Fiii and 7Fiv) compared with WT. The stroma was almost entirely devoid of HSD3B1 immunoreactive cells, with only a few discrete immunopositive cells detected. In these InhaKO sections, there were no antral follicles evident, and thus mural and granulosa cells could not be distinguished. Immunoreactive HSD3B1 was detected within these follicular regions at varying intensities. Immunoreactive CYP11A1 was detected in WT ovarian stroma, corpora lutea, thecal cells, but not in developing follicles (n = 4; Fig. 7Gi and 7Gii). In the InhaKO ovary, CYP11A1 was only detected in the stroma within discrete cell populations), and was generally low in follicular areas, though some discrete populations had a higher intensity of immunodetection (Fig. 7Giii and 7Giv).

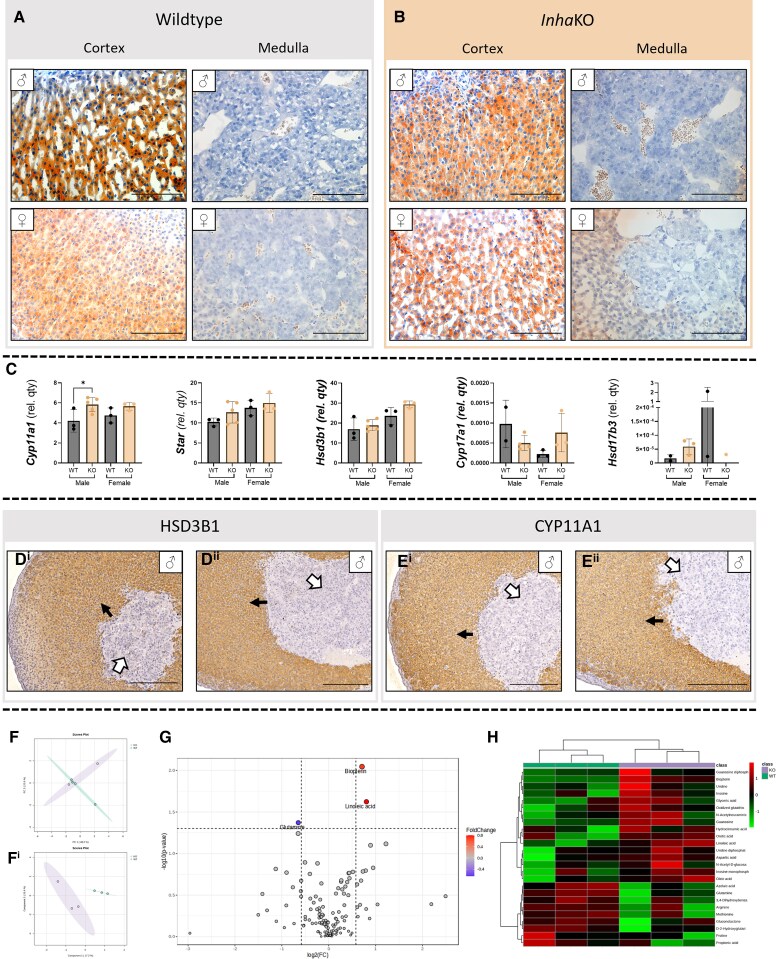

Subtle Effects of Excess Activin A on Adrenal Lipids, Steroids, and Metabolism

To consider how excess activin A bioactivity affects the associated HPA axis, adrenal glands were examined. The adrenal gland Oil Red O signal was predominantly confined to the steroidogenic cortex, with minimal accumulation in the central adrenal medulla (Fig. 8A). No appreciable difference in signal distribution was observed in InhaKO adrenal glands (n = 6; Fig. 8B). Droplets were not as distinct as in the testis.

Figure 8.

Excess activin A affects adrenal gland reveals subtle effects of excess activin A on cell metabolism. (A) In the wild type adrenal gland, lipid droplets accumulate in the cortex, but are sparse in the adrenal medulla, and the InhaKO adrenal (B) was not obviously different. (C) Transcripts encoding steroidogenic enzymes measured by qRT-PCR. Mean ± SD transcript level normalized to Rplp0 in InhaKO and WT adrenals glands, individual data points represent biologically independent samples, n ≥ 3 used for statistical analyses. Cyp11a1 was significantly higher in the male but not female InhaKO adrenal glands (P = .0437, P = .0200 respectively). (D) HSD3B1 immunoreactivity in the adrenal cortex of the WT (Di) and KO (Dii) was similar (black arrows, n = 4 WT, n = 3 InhaKO). (E) Cyp11A1 was also present in the adrenal cortex of WT (Ei) and KO (Eii) adrenals with no overt difference (black arrow, n = 3 each). HSD3B1 and CYP11A1 were absent from the medulla (white arrow). Negative controls are provided in Fig. S4 (29). PCA (F) and PLSDA (Fi) analyses demonstrate clustering of WT (green) and InhaKO (red) adrenal gland metabolic profiles. (G) Volcano plot demonstrates 2 metabolites were significantly higher in the InhaKO adrenal glands, and 1 was significantly lower compared to WT. (H) Heatmap analysis shows discrete metabolomic profiles of the InhaKO (purple) and WT (green) adrenal glands. All metabolomic analyses performed on male adrenal glands. Scale bars represent 100 µm (A, B) or 200 µm (D, E). ♂ and ♀: male and female respectively.

Steroidogenic transcript levels were assessed within the adrenal glands. In the InhaKO, only Cyp11a1 was significantly different compared to WT male adrenal glands (Fig. 8C; P = .0437). No significant difference was detected in female adrenal glands between genotypes (InhaKO; P = .2000). No significant difference was detected in any other transcript between genotypes (Star [male P = .3929, female P > .9999], Hsd3b1 [male P = .5106, female P = .0933], and Cyp17a1 [female P = .1000]). Cyp17a1 was not detected in enough male samples, and Hsd17b3 was not detected in enough male or female samples to perform statistical analyses.

Both HSD3B1 and CYP11A1 immunoreactivity were strong in the adrenal cortex and present at similar levels in both WT (Fig. 8Di and 8Ei) and InhaKO (Fig. 8Dii and 8Eii) adrenal glands. Immunolocalization and metabolomic analysis was only performed on male adrenal glands, as transcriptional differences were only significant in glands of this sex. Additional preliminary data indicate metabolism is also perturbed within adult male adrenal glands in the condition of excess activin A bioactivity (Fig. 8F). Of 137 detected metabolites, 3 were differentially abundant between WT and InhaKO adrenal glands (Fig. 8G): linoleic acid (FC = 1.75, P = .0238), biopterin (FC = 1.6, P = .0090), and glutamine (FC = 0.64, P = .0424). When examining the top 25 differentially detected metabolites, hierarchical clustering distinguished the 2 genotypes (Fig. 8H).

Discussion

By integrating unbiased multiomics and targeted histological approaches, this work demonstrates the significant impact of unopposed/excess activin bioactivity on lipid, metabolite, and steroid profiles in the testis, ovary, and adrenal gland of adult mice. These findings reinforce the expectation that the physiology of both young and adult individuals will be affected by exposure to chronically high activin A bioactivity levels, whether this occurs through exposure to medication, infection, or other conditions. We identify processes and cell types that are potentially vulnerable to excess activin A and contribute to sustained endocrine and reproductive health consequences.

Activin signaling affects both germline and somatic cells (19, 28), and its impact on steroid production changes through the lifespan. In fetal mouse testes, high activin A bioactivity (in InhaKO E13.5 testes) selectively acts on Leydig cells, while low levels (in E15.5 InhbaKO testes) particularly affect Sertoli cells (13, 14). Importantly, in both cases the deviance from normal levels present in WT littermates reduces the amount of intratesticular T during the fetal masculinization window and results in additional changes to the local steroid milieu. In adult life, testicular steroid production relies solely on Leydig cell function. Because steroid production is organ- and sex-specific, understanding the complexities of how elevated activin bioavailability affects this fundamental process will require evaluation across development at the level of both tissue and cell.

To identify the cell types most impacted by chronic excess of activin A, MALDI-MSI was utilized to resolve the spatial context of differentially abundant lipids. This approach additionally clarified intratesticular effects of activin A as vascular infiltration may cause blood lipids to overwhelm whole testis homogenate analyses. While some lipids we measured appeared uniquely associated with the tumors, differentially abundant lipids were also observed in morphologically N areas of InhaKO testes. There was also a discrete lipid signature in the regions directly adjacent to the tumors (TATs) and within subregions of the tumors. This indicates that the tumor is not the sole source of measured changes in lipid content, rather the lipid content may reflect the changes in cellular identity and function invoked by elevated activin A, as evident from transcriptomic analyses (13). It will be important to directly examine the cell-specific actions of activin A on intracellular lipid composition.

The abundance of LDs close to and within tumors in InhaKO samples is similar to observations of intratubular LD deposition in adult human testes bearing germ cell neoplasia in situ cells, the precursors to testicular germ cell tumors (40), a phenomenon also evident within tubules of the fetal InhbaKO testes with perturbed activin A (13, 14). Further, distinct sphingolipid and ceramide levels (altered in InhaKO testes) are also related to the development of testicular germ cell tumors, with sphingolipid biosynthesis comparatively higher in embryonal carcinoma (NT2 cells) than seminoma (Tcam-2 cells) (41), indicating sphingolipid components of the tumor-associated LDs may be related to tumorigenesis in this model (42).

Alongside the differential abundance of sphingolipids in InhaKO testes compared with WT, sphingolipid metabolism terms were enriched in joint pathway analyses of metabolomic and transcriptomic data, further highlighting this as a pathway of interest. Sphingolipid metabolism is linked to steroid hormone production (43-45), and thus represents a potential causal mechanism of the downstream impacts of chronically elevated activin A. Pertinent to reproductive health, sphingolipid elevation and metabolism has been linked to reduced male fertility (46, 47), and improper trophoblast and uterine function (48, 49). Furthermore, activin A directly impacts the sphingosine-1 phosphate signaling pathway in uterine leiomyomas (50). Thus, many of the dysregulated lipid species identified here, including sphingolipids, may prove to be novel markers of activin A bioactivity of relevance to reproductive health.

The reduced T and DHT levels in adult InhaKO testes reported here (Fig. 4) are similar to the altered steroid composition in fetal testes (13, 14), which has significant implications for male reproductive and general health (51). We speculate that the dysregulated synthesis of sphingolipids and their derivative ceramides in InhaKO testes contributes to this suppression of DHT production (52). An intriguing feature of activin control of steroid production is its conservation across the animal kingdom, with activin and its downstream target 20-hydroxyecdysone responsible for production of the steroid ecdysone in the ladybird, with implications for larval development (53, 54).

The testis tumors in InhaKO mice are considered to originate from Sertoli cells (16, 21, 55). These highly steroidogenic tumors appear to develop from cells located within the seminiferous tubule, prior to tubule membrane breakdown and encroachment into the interstitial space (28). HSD3B1-positive and CYP11A1-positive cells appear within seminiferous tubules that are near these morphologically abnormal regions; however, not all cells within the tubule are immunoreactive, and the CYP11A1 signal intensity differs between cells within the tumors (Fig. 5D and 5E). It will be important to determine whether abnormal steroidogenesis is an early hallmark of developing activin A–driven lesions or is a consequence of tumor expansion.

Cells within the InhaKO testis tumors were identified here as a lipid-rich microenvironment of abnormal steroid synthesis, rich in metabolic processes related to cancerous tumors. This implies excess activin A may induce a cancerous metabolic cascade, promoting the formation of gonadal tumors, and eventually adrenal gland tumors (Fig. 8H). The altered lipid metabolism pathways identified in this study relate to drug resistance development in cancers (56), and we speculate that targeting activin A bioactivity may be appropriate for management of sphingolipid-dysregulated tumors.

In our preliminary studies, unopposed activin A bioactivity in InhaKO ovaries results in lipid-rich focal regions and grossly altered distribution profiles of steroidogenic cells. Disruption to granulosa cell lipids, and the potential over-proliferation of activin-affected granulosa cells (evidenced in prepubertal mice (57)), may impact the provision of appropriate sugars and amino acids to the oocytes which they nourish (58). Diminished P4 bioactivity, either through reduced pregnenolone conversion by CYP11A1, reduces A4 production, likely culminating in diminished ovarian function.

Our pilot investigations detected a slight but significant increase in Cyp11a1 in the InhaKO male adrenal gland. A subtle impact on the InhaKO adrenal gland at 45 to 56 days (used here) is not unexpected, given that gonadectomy is required to prolong their lifespan sufficient to observe adrenal tumorigenesis (onset at 21 weeks of age). While serum cortisol levels were unchanged in InhaKO mice compared with WT, even following adrenal gland tumor formation (21), our preliminary metabolomic profiling of the adrenal gland indicates excess activin A affects cellular metabolism prior to tumorigenesis and may have functional consequences independent of cortisol synthesis. However, as T is a potent regulator of adrenal cortex sexual dimorphism (59), and is significantly reduced in InhaKO male mice, the observed impacts on the adrenal gland may be indirect; gonadectomized studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Measuring changes in the metabolomic and steroidogenic profiles of testes, ovaries, and adrenal glands exposed to excess activin A over the lifespan will aid in discriminating direct and indirect effects.

This work has uncovered novel tissue responses to a chronic excess of activin A bioactivity, providing significant evidence of its impact on lipids, steroids, and metabolites in 3 organs. The significance of these outcomes relate to the goal of developing therapeutic agents that restrict activin A bioactivity, currently being explored for conditions such as cachexia, osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and infections (eg, COVID-19) (7-12, 60). Because such compounds may not be suitable for administration during pregnancy, the hypothesis that elevated activin A during a preeclamptic pregnancy leads to changes in serum concentrations of steroid hormones and aldosterone (61, 62) may open new avenues of postnatal treatment. The myriad scenarios in which humans may be exposed to the effects of excess activin A will continue to be of clinical interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous financial contribution of John McBain to the Hudson Institute which enabled this research project. Services and equipment provided by the Monash Histology Platform, and technical support by Ms. Reena Desai (ANZAC Research Institute, Sydney Local Health District, University of Sydney) underpinned these outcomes. NCRIS-enabled Metabolomics Australia infrastructure at the University of Melbourne and funded through BioPlatforms Australia was critical for this research, with special acknowledgement to Drs. Brunda Nijigal and Amanda Peterson. The timsTOF fleX is located at and funded by the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Centre for Integrated Cancer Systems Biology at SAHMRI. We thank Oxford Brookes University for supplying the antibody used in the activin A immunolocalization studies. We acknowledge this work was primarily conducted on the lands of the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation, and we pay our respects to their elders: past, present, and emerging.

Abbreviations

- A4

androstenedione

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- FC

fold-change

- InhaKO

inhibin-α knockout

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- LD

lipid droplet

- MALDI-MSI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry imaging

- N

normal

- P4

progesterone

- PBQC

pooled biological quality control

- T

testosterone

- TAT

tumor-associated tubule

- TBS

Tris buffered saline

- TCA

citrate cycle

- TM

tumorigenic

- WT

wild type

Contributor Information

Jennifer C Hutchison, Centre for Reproductive Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia; Department of Molecular and Translational Science, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia; TIGRR Laboratory, School of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia.

Paul J Trim, Proteomics, Metabolomics and MS Imaging Facility, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia.

Penny A F Whiley, Centre for Reproductive Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia; Department of Molecular and Translational Science, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia.

David J Handelsman, ANZAC Research Institute, University of Sydney, Concord, NSW 2138, Australia.

Marten F Snel, Proteomics, Metabolomics and MS Imaging Facility, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia.

Nigel P Groome, Oxford-Brookes University, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK.

Mark P Hedger, Centre for Reproductive Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia; Department of Molecular and Translational Science, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia.

Kate L Loveland, Centre for Reproductive Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia; Department of Molecular and Translational Science, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia.

Funding

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) GNT1181516 to K.L.L., the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Scheme to the Hudson Institute of Medical Research, and a gift by John McBain to the Centre for Reproductive Health in the Hudson Institute of Medical Research.

Author Contributions

J.C.H. designed and performed experiments, led the data reporting and statistical analyses, and composed the manuscript. P.J.T. and M.F.S. performed experiments, conducted statistical analyses, and facilitated data interpretation. P.A.F.W. performed RNA-seq analyses and data reporting. D.J.H. facilitated steroid analysis. M.P.H. and N.P.G. supplied critical reagents. K.L.L. conceived the experimental design and contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided editorial comments to J.C.H. and K.L.L.

Disclosures

D. Handelsman is an Editorial Board Member for Endocrinology and played no role in the Journal's evaluation of the manuscript. There are no other disclosures to make.

Data Availability

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the Figshare data repository listed in the references (doi: https://doi.org/10.26188/c.7703852).

References

- 1. Wijayarathna R, de Kretser DM. Activins in reproductive biology and beyond. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(3):342‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reis F. Activin A in mammalian physiology. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):739‐780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellissima V, Visser GHA, Ververs TF, et al. Antenatal maternal antidepressants drugs affect activin A concentrations in maternal blood, in amniotic fluid and in fetal cord blood. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(sup2):31‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spencer K, Cowans NJ, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum inhibin-A and activin-A levels in the first trimester of pregnancies developing pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):622‐626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hardy JT, Buhimschi IA, McCarthy ME, et al. Imbalance of amniotic fluid activin-A and follistatin in intraamniotic infection, inflammation, and preterm birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(7):2785‐2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barber C V, Yo JH, Rahman RA, Wallace EM, Palmer KR, Marshall SS. Activin A and pathologies of pregnancy: a review. Placenta. 2023;136:35‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harada K, Shintani Y, Sakamoto Y, Wakatsuki M, Shitsukawa K, Saito S. Serum immunoreactive activin A levels in normal subjects and patients with various diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(6):2125‐2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loumaye A, De Barsy M, Nachit M, et al. Role of activin A and myostatin in human cancer cachexia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(5):2030‐2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAleavy M, Zhang Q, Ehmann PJ, et al. The activin/FLRG pathway associates with poor COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients. Mol Cell Biol. 2022;42(1):e0046721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grigoriev V, Korzun T, Moses AS, et al. Targeting metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma using follistatin mRNA lipid nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2024;18(49):33330‐33347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hagg A, O'Shea E, Harrison CA, Walton KL. Targeting activins and inhibins to treat reproductive disorders and cancer cachexia. J Endocrinol. 2023;258(1):e220290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wits M, Becher C, De Man F, Sanchez-Duffhues G, Goumans MJ. Sex-biased TGFβ signalling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119(13):2262‐2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whiley PAF, Luu MCM, O’Donnell L, Handelsman DJ, Loveland KL. Testis exposure to unopposed/elevated activin A in utero affects somatic and germ cells and alters steroid levels mimicking phthalate exposure. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1234712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whiley PAF, O’Donnell L, Moody SC, et al. Activin A determines steroid levels and composition in the fetal testis. Endocrinology. 2020;161(7):1‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Vassalli A, et al. Functional analysis of activins during mammalian development. Nature. 1995;374(6520):354‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su J-G, Hsueh AJW, Bradley A. a-Inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature. 1992;360(6402):313‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Welsh M, Suzuki H, Yamada G. The masculinization programming window. Endocr Dev. 2014;27:17‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mendis SHS, Meachem SJ, Sarraj MA, Loveland KL. Activin A balances sertoli and germ cell proliferation in the fetal mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(2):379‐391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Itman C, Bielanowicz A, Goh H, et al. Murine inhibin α-subunit haploinsufficiency causes transient abnormalities in prepubertal testis development followed by adult testicular decline. Endocrinology. 2015;156(6):2254‐2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drechsel KCE, Pilon MCF, Stoutjesdijk F, et al. Reproductive ability in survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult Hodgkin lymphoma: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(4):486‐517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Mather JP, Krummen L, Lu H, Bradley A. Development of cancer cachexia-like syndrome and adrenal tumors in inhibin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(19):8817‐8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wijayarathna R, de Kretser DM, Meinhardt A, et al. Activin over-expression in the testis of mice lacking the inhibin α-subunit gene is associated with androgen deficiency and regression of the male reproductive tract. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;470:188‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walton KL, Goney MP, Peppas Z, et al. Inhibin inactivation in female mice leads to elevated FSH levels, ovarian overstimulation, and pregnancy loss. Endocrinology. 2022;163(4):bqac025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Indumathy S, Pueschl D, Klein B, et al. Testicular immune cell populations and macrophage polarisation in adult male mice and the influence of altered activin A levels. J Reprod Immunol. 2020;142:103204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Biniwale S, Wijayarathna R, Pleuger C, et al. Regulation of macrophage number and gene transcript levels by activin A and its binding protein, follistatin, in the testes of adult mice. J Reprod Immunol. 2022;151:103618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morianos I, Papadopoulou G, Semitekolou M, Xanthou G. Activin-A in the regulation of immunity in health and disease. J Autoimmun. 2019;104:102314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wijayarathna R, Hedger MP. New aspects of activin biology in epididymal function and immunopathology. Andrology. 2024;12(5):964‐972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whiley PAF, Nathaniel B, Stanton PG, Hobbs RM, Loveland KL. Spermatogonial fate in mice with increased activin A bioactivity and testicular somatic cell tumours. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1237273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hutchison JC, Trim PJ, Whiley PAF, et al. Supplementary data for: impact of excess activin A on the lipids, metabolites, and steroids of adult mouse reproductive organs. figshare. 2025. 10.26188/c.7703852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, et al. Qupath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676‐682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. White JB, Trim PJ, Salagaras T, et al. Equivalent carbon number and interclass retention time conversion enhance lipid identification in untargeted clinical lipidomics. Anal Chem. 2022;94(8):3476‐3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pang Z, Chong J, Zhou G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W388‐W396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Murphy RC, et al. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S9‐S14. Doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800095-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Truong JXM, Spotbeen X, White J, et al. Removal of optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound from embedded tissue for MALDI imaging of lipids. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021;413(10):2695‐2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skiba MA, Bell RJ, Islam RM, Handelsman DJ, Desai R, Davis SR. Androgens during the reproductive years: what is normal for women? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(11):5382‐5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Handelsman DJ, Ly LP. An accurate substitution method to minimize left censoring bias in Serum steroid measurements. Endocrinology. 2019;160(10):2395‐2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Svingen T, François M, Wilhelm D, Koopman P. Three-dimensional imaging of Prox1-EGFP transgenic mouse gonads reveals divergent modes of lymphangiogenesis in the testis and ovary. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morris ME, Meinsohn MC, Chauvin M, et al. A single-cell atlas of the cycling murine ovary. Elife. 2022;11:e77239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nielsen JE, Lindegaard ML, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase in human testis and in germ cell neoplasms. Int J Androl. 2010;33(1):e207‐e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Batool A, Chen SR, Liu YX. Distinct metabolic features of seminoma and embryonal carcinoma revealed by combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(4):1819‐1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jia W, Yuan J, Zhang J, Li S, Lin W, Cheng B. Bioactive sphingolipids as emerging targets for signal transduction in cancer development. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2024;1879(5):189176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang D, Tang Y, Wang Z. Role of sphingolipid metabolites in the homeostasis of steroid hormones and the maintenance of testicular functions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1170023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Urs AN, Dammer E, Sewer MB. Sphingosine regulates the transcription of CYP17 by binding to steroidogenic factor-1. Endocrinology. 2006;147(11):5249‐5258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pörn MI, Tenhunen J, Slotte JP. Increased steroid hormone secretion in mouse Leydig tumor cells after induction of cholesterol translocation by sphingomyelin degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1093(1):7‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Otala M, Pentikäinen MO, Matikainen T, et al. Effects of acid sphingomyelinase deficiency on male germ cell development and programmed cell death. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(1):86‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Correnti S, Preianò M, Fregola A, et al. Seminal plasma untargeted metabolomic and lipidomic profiling for the identification of a novel panel of biomarkers and therapeutic targets related to male infertility. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1275832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Johnstone ED, Chan G, Sibley CP, Davidge ST, Lowen B, Guilbert LJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibition of placental trophoblast differentiation through a Gi-coupled receptor response. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(9):1833‐1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mizugishi K, Li C, Olivera A, et al. Maternal disturbance in activated sphingolipid metabolism causes pregnancy loss in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(10):2993‐3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bernacchioni C, Ciarmela P, Vannuzzi V, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling in uterine fibroids: implication in activin A pro-fibrotic effect. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(6):1576‐1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O’Donnell L, McLachlan R, Wreford NG, De Kretser DM, Robertson DM. Testosterone withdrawal promotes stage-specific detachment of round spermatids from the rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1996;55(4):895‐901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lucki NC, Sewer MB. Multiple roles for sphingolipids in steroid hormone biosynthesis. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:387‐412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Du JL, Chen F, Wu JJ, Jin L, Li GQ. Smad on X is vital for larval-pupal transition in a herbivorous ladybird beetle. J Insect Physiol. 2022;139:104387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Masuoka Y, Yaguchi H, Toga K, Shigenobu S, Maekawa K. TGFβ signaling related genes are involved in hormonal mediation during termite soldier differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(4):e1007338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haverfield JT, Stanton PG, Loveland KL, et al. Suppression of Sertoli cell tumour development during the first wave of spermatogenesis in inhibin α-deficient mice. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2017;29(3):609‐620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bataller M, Sánchez-García A, Garcia-Mayea Y, Mir C, Rodriguez I, LLeonart ME. The role of sphingolipids metabolism in cancer drug resistance. Front Oncol. 2021;11:807636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Myers M, Middlebrook BS, Matzuk MM, Pangas SA. Loss of inhibin alpha uncouples oocyte-granulosa cell dynamics and disrupts postnatal folliculogenesis. Dev Biol. 2009;334(2):458‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gilchrist RB, Lane M, Thompson JG. Oocyte-secreted factors: regulators of cumulus cell function and oocyte quality. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(2):159‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lyraki R, Schedl A. The sexually dimorphic adrenal cortex: implications for adrenal disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jeon J, Lee H, Jeon MS, et al. Blockade of activin receptor IIB protects arthritis pathogenesis by non-amplification of activin A-ACVR2B-NOX4 axis pathway. Adv Sci. 2023;10(14):e2205161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alsnes I V, Janszky I, Åsvold BO, Økland I, Forman MR, Vatten LJ. Maternal preeclampsia and androgens in the offspring around puberty: a follow-up study. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Washburn LK, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC, et al. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in adolescent offspring born prematurely to mothers with preeclampsia. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015;16(3):529‐538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Hutchison JC, Trim PJ, Whiley PAF, et al. Supplementary data for: impact of excess activin A on the lipids, metabolites, and steroids of adult mouse reproductive organs. figshare. 2025. 10.26188/c.7703852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the Figshare data repository listed in the references (doi: https://doi.org/10.26188/c.7703852).