Abstract

Cervical cancer is a preventable disease and ranks as the fourth most common cancer, as well as a major cause of cancer deaths among women globally. Despite initiatives by the World Health Organization to reduce cervical cancer incidence through vaccination, screening, and treatment, significant inequalities in healthcare access persist, particularly in low-income regions where economic and infrastructural barriers hinder access to screening services. Therefore, this study aimed to examine wealth-related inequalities in cervical cancer screening among women in Sub-Saharan African countries. The study analyzed 138,605 weighted samples of reproductive-aged women from DHS data spanning 2015 to 2023 across SSA countries. To assess socioeconomic-related inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake, the Erreygers normalized concentration index and its concentration curve were utilized. Additionally, a decomposition analysis was conducted to identify factors contributing to this inequality. The weighted Erreygers normalized concentration index was 0.25 with a standard error of 0.0078 (P value < 0.0001), indicating a statistically significant pro-rich distribution of wealth-related inequalities in cervical cancer screening uptake among reproductive-aged women. The decomposition analysis identified media exposure (20%), wealth index (15.58%), educational status (6.23%), and place of residence (2.18%) significantly contribute to screening inequalities. To address cervical cancer screening disparities in SSA, targeted strategies such as awareness campaigns for low-income groups, free screening services, mobile units in rural areas, and health literacy programs are recommended. Training community health workers and policy advocacy are also crucial. Comprehensive interventions should enhance media outreach, health education, and healthcare accessibility in both urban and rural areas to ensure equitable screening rates.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Concentration index, Decomposition analysis, Socioeconomic-related inequality, Sub-Saharan Africa

Subject terms: Cancer, Health care

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the only cancer where the cause is fully known, making it more manageable and preventable than most cancers1,2. Globally, it is the fourth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death among women3,4. Every two minutes, a woman dies from cervical cancer somewhere in the world5. In 2022, roughly 660,000 women were newly diagnosed, and about 349,000 died from the disease3. Nearly 94% of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries, with the highest incidence and death rates in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia3,6.

The burden of cervical cancer could be reduced through robust prevention programs that emphasize early prevention, timely diagnosis, effective screening, appropriate referrals, and advanced treatment options7,8. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a global plan aiming for three main targets by 2030: vaccinating 90% of girls by age 15, screening 70% of women between ages 35 and 45, and treating 90% of women diagnosed with cervical cancer5. The WHO’s elimination strategy emphasizes the need for ongoing, improved monitoring to help program managers identify gaps and take targeted actions9. Cervical cancer screening is a vital component of this strategy and is widely regarded as the most effective prevention approach, as it detects early changes before, they progress to invasive cancer10,11. However, two out of three women aged 30 to 49 globally have never been screened, and screening coverage is very low in low- and middle-income countries, where the disease burden is highest12. In 2020, less than half of women in low-income countries (35%) and lower-middle-income countries (55%) received cervical cancer screening, compared to 80% in high-income countries9. This highlights significant unmet healthcare needs and a lack of attention to screening programs.

Cervical cancer highlights inequalities in society, especially those tied to socioeconomic status. Health inequality refers to the uneven access to healthcare resources, services, and health outcomes among different income groups or wealth levels13,14. These economic gaps are limiting women’s access to early screenings. The use of screening services is often low in areas with low socioeconomic status, limited economic growth, and poor healthcare infrastructure. Factors such as few health facilities, high costs, low-quality screening, and a lack of culturally suitable screening options all contribute to this low uptake15–17.

Research on socioeconomic inequalities in cervical cancer screening is limited in low-income regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Studies from Malawi18 and 16 other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)19 have highlighted age, educational status, marital status, place of residence, and wealth index as significant factors contributing to these inequalities. Despite these findings, there are no existing studies specifically addressing socioeconomic inequalities in cervical cancer screening uptake within SSA. Therefore, this study aims to provide comprehensive evidence on the factors contributing to socioeconomic inequalities in cervical cancer screening uptake.

Methods

Data source, study period, and population

The study utilized the appended woman file (IR) from the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 11 SSA countries between 2015 and 2023. Data was obtained from the DHS office upon reasonable request via the DHS Program. The analysis included 138,605 women aged 15 to 49 years, all of whom had complete information on the variables of interest.

Study variables

Dependent variable

Cervical cancer screening was defined as women reporting ‘yes’ to any of the following questions prior to the survey: ‘Have you ever been screened for cervical cancer?’ ‘Have you ever been tested for cervical cancer?’ or ‘Have you had a cervical examination before?’ Further details on the cervical cancer screening questionnaires can be found in20. The responses were dichotomized as yes = 1 or no = 0 and used as the outcome variable.

Independent variables

Women’s age, marital status, educational level, employment status, wealth index, sex of household head, place of residence, and perceived distance to health facility, were considered as important explanatory variables.

Socio-economic status

To capture household socioeconomic status, the current study utilized the household wealth index. This index is the standard measure employed when household expenditure and income data are unavailable21. In the DHS data, the wealth index was constructed using principal component analysis and then categorized into five quintiles: poorest (quintile 1), poorer (quintile 2), middle (quintile 3), richer (quintile 4), and richest (quintile 5)22.

Data management and statistical analysis

The latest datasets from 11 Sub-Saharan African countries were appended, recoded, cleaned, and analyzed with STATA version 17. Weighting was performed using a weighting factor ‘wgt’, calculated by dividing the variable v005 (women’s individual sample weight with six decimal points) by 1,000,000. All descriptive statistics were conducted using the STATA command tab varlist [iw = wgt], where varlist represents the variable of interest and wgt is the weighting factor. This approach ensures that the data accurately represents the studied population, thus enabling more reliable and meaningful conclusions from the analysis.

Equiplot graphical tools were used to visualize and compare absolute inequalities between different groups or categories. Equiplot is particularly useful for presenting data on health disparities, such as screening coverage, across various subpopulations like wealth quintiles, education levels, age categories, and place of residence. Furthermore, it allows to see both the level of coverage in each group and the distance between groups, which represents absolute inequality.

Concentration curve and concentration index

The study employed a concentration curve to determine the presence of socioeconomic inequality in certain health variables and to assess its variation at different points. Additionally, a concentration index was used to quantify and compare the extent of socioeconomic-related inequality in the health variable23.

Concentration curve and concentration indexes are essential tools for analyzing socioeconomic inequality, particularly in health. The concentration curve visually represents inequality by plotting the cumulative percentage of a health variable against the cumulative percentage of the population ranked by socioeconomic status, with deviations from the 45-degree line indicating the degree of inequality24. The concentration index quantifies this inequality, ranging from − 1 (pro-poor) to 1 (pro-rich), with 0 indicating perfect equality25. A negative concentration index (pro-poor) means the variable, such as cervical cancer screening uptake, is more concentrated among poorer groups. Conversely, a positive concentration index (pro-rich) indicates the variable is more concentrated among wealthier groups. This helps to understand and visualize the distribution of resources or services across different socioeconomic strata. You.

Since the outcome variable in this study is binary (screened or not screened for cervical cancer), the bounds of the concentration index (C) depend on the mean (µ) of the outcome variable, and they do not vary between − 1 and 1. Therefore, the bounds of C range from µ–1 (lower bound) to 1–µ (upper bound). To address this, the present study utilized Erreygers’ normalized concentration index (ECI), a modified version of the concentration index26. It adjusts the concentration index to have a range between − 1 and 1, making it easier to interpret and compare across different studies27.

ECI can be mathematically defined to adjust for the bounded nature of binary variables. Here’s how it works:

|

where µ is the mean of the binary outcome variable (e.g., the proportion of women screened for cervical cancer). C is the unadjusted concentration index.

This formula corrects for the fact that the concentration index’s bounds depend on the mean of the binary variable, providing a more accurate measure of inequality.

Wagstaff-type decomposition analysis

Wagstaff decomposition analysis was utilized to explain socioeconomic-related inequalities in cervical cancer screening uptake28. This method decomposes the concentration index, which measures inequality, into contributions from various factors such as wealth, education, and other determinants28. By identifying the factors that contribute most to the observed inequality, the analysis can inform targeted interventions.

This analysis is based on the concentration curve (CC) and the concentration index (C)28. The comprehensive analysis involves running regression analyses, computing elasticity’s (weighted coefficients), calculating concentration indexes for covariates, and determining each factor’s contribution to overall inequality. This process aids in identifying the primary contributors to disparities and informing targeted interventions to mitigate inequality.

Ethical consideration

Permission to get access to the data was obtained from the measure DHS program online request from http://www.dhsprogram.com.website and the data used were publicly available with no personal identifier.

Result

Socio-demographic distribution of the study participants

Total weighted samples of 138,605 women of reproductive age were included in the current analysis. The median age of the respondents was 28 years (IQR = 17 years). More than one-third (36.32%) of women had a secondary educational level while 56.32% of them had formal employment. Regarding the wealth index distribution, 16.91%, 18.06%, 19.38%, 21.60%, and 24.06% of them resided in poorer, poor, middle, rich, and richer, respectively. Two-thirds (70.33%) of the respondents resided in male-headed households (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of respondent characteristics and cervical cancer screening status in Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 138,605).

| Variable | Category | Weighted frequency (%) | Prevalence of cervical cancer screening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Yes (%) | |||

| Age | 15–19 | 28,890 (21.01) | 28,487 (98.61) | 403 (1.39) |

| 20–24 | 25,347 (18.44) | 24,168 (95.35) | 1179 (4.65) | |

| 25–29 | 22,828 (16.61) | 20,978 (91.89) | 1851 (8.11) | |

| 30–34 | 19,427 (14.13) | 17,359 (89.36) | 2068 (10.64) | |

| 35–39 | 17,092 (12.43) | 15,059 (88.11) | 2033 (11.89) | |

| 40–44 | 13,385 (9.74) | 11,593 (86.61) | 1792 (13.39) | |

| 45–49 | 10,504 (7.64) | 9118 (86.81) | 1386 (13.19) | |

| Educational level | No formal education | 38,438 (27.73) | 36,356 (94.58) | 2082 (5.42) |

| Primary | 40,486 (29.21) | 37,662 (93.03) | 2824 (6.97) | |

| Secondary | 50,347 (36.32) | 46,272 (91.91) | 4075 (8.09) | |

| Higher | 9,334 (6.73) | 7345 (78.68) | 1989 (21.32) | |

| Wealth quintile | Poorer | 23,435 (16.91) | 22,609 (96.47) | 826 (3.53) |

| Poor | 25,029 (18.06) | 23,733 (94.82) | 1296 (5.18) | |

| Middle | 26,855 (19.38) | 25,147 (93.64) | 1708 (6.36) | |

| Rich | 29,933 (21.60) | 27,337 (91.33) | 2596 (8.67) | |

| Richer | 33,351 (24.06) | 28,807 (86.38) | 4544 (13.62) | |

| Employment status | Not employed | 60,045 (43.68) | 56,728 (94.48) | 3316 (5.52) |

| Employed | 77,428 (56.32) | 70,033 (90.45) | 7394 (9.55) | |

| Marital status | Never in union | 40,421 (29.16) | 38,946 (96.35) | 1475 (3.65) |

| Currently in union | 84,751 (61.15) | 76,811 (90.63) | 7940 (9.37) | |

| Formerly in union | 13,433 (9.69) | 11,877 (88.42) | 1555 (11.58) | |

| Sex of household head | Male | 97,475 (70.33) | 90,090 (92.42) | 7385 (7.58) |

| Female | 41,130 (29.67) | 37,545 (91.28) | 3585 (8.72) | |

| Media exposure | No | 38,396 (27.70) | 37,077 (96.56) | 1319 (3.44) |

| Yes | 100,209 (72.30) | 90,558 (90.37) | 9651 (9.63) | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 64,535 (46.56) | 57,854 (89.65) | 6681 (10.35) |

| Rural | 74,070 (53.44) | 69,782 (94.21) | 4288 (5.79) | |

| Perceived distance to health facility | Big problem | 47,725 (34.43) | 44,742 (93.75) | 2983 (6.25) |

| Not a big problem | 90,880 (65.57) | 82,893 (91.21) | 7987 (8.79) | |

Cervical cancer screening uptake

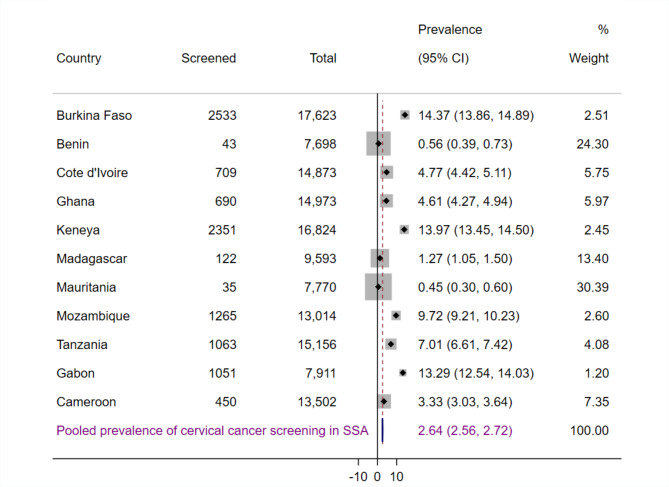

The proportion of women who screened for cervical cancer varied significantly across countries, ranging from 0.56% (95% CI: 0.39%, 0.73%) in Benin to 14.37% (95% CI: 13.86%, 14.89%) in Burkina Faso (Fig. 1). The Equiplot highlights that, despite higher rates of cervical cancer screening among older women (Fig. 2), wealthiest women (Fig. 3), urban residents (Fig. 4), and those with higher education levels (Fig. 5) who do not perceive distance to health facilities as a big problem (Fig. 6) across most SSA countries, countries like Benin, Mauritania, and Madagascar show uniformly low screening rates across all these characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Pooled prevalence of cervical cancer screening among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Fig. 2.

Coverage of cervical cancer screening by age group among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Fig. 3.

Coverage of cervical cancer screening by wealth quintiles among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Fig. 4.

Coverage of cervical cancer screening by place of residence among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Fig. 5.

Coverage of cervical cancer screening by educational level among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Fig. 6.

Coverage of cervical cancer screening by perceived distance to health facility among women of reproductive age in SSA.

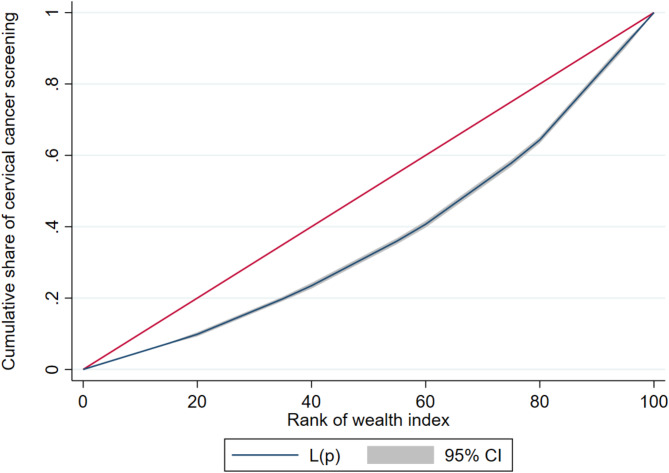

Wealth-related inequalities in cervical cancer screening

Cervical cancer screening rates are higher among wealthier individuals (pro-rich pattern), as indicated by the concentration curve lying below the line of equality (Fig. 7). The concentration index value of 0.25 indicates a positive concentration, suggesting that cervical cancer screening is more prevalent among women with higher wealth quintile. The statistically significant p-value (0.0000) confirms these results are not due to random chance. Furthermore, the smaller standard error value (0.007786) indicates a high level of precision in this finding (Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Concentration curve for cervical cancer screening in SSA.

Table 2.

Concentration index for cervical cancer screening in Sub-Saharan Africa.

| Index | Number of observations | Index value | Robust std. error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | 138,605 | 0. 24,988,076 | 0.00778604 | 0.0000 |

CI concentration index.

Decomposition analysis of the socio-economic inequalities in cervical cancer screening

A decomposition analysis, based on Erreygers normalized concentration index, was conducted to determine the extent to which measured socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening is attributed to wealth quintiles and other variables. The analysis reveals the contributions of individual variables to the overall socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake. To understand the factors contributing to this inequality, we calculated the coefficient and its significance level, elasticity, concentration index, and percent contribution.

Media exposure accounts for one-fifth (20%) of the pro-rich inequalities in cervical cancer screening uptake among women of reproductive age. Wealth index and educational status contributed 15.58% and 6.23% to this inequality, respectively. While place of residence explains 2.18% of the pro-rich disparities in cervical cancer screening uptake (Table 3).

Table 3.

Decomposition of concentration index for cervical cancer screening of women of reproductive age group in SSA.

| Variable | Category | Coefficient | Elasticity | Concentration index | Absolute contribution | % Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–19 | |||||

| 20–24 | 0.0207*** | 0.0151 | 0.0106 | 0.0002 | 0.06 | |

| 25–29 | 0.0459*** | 0.0303 | 0.0095 | 0.0003 | 0.11 | |

| 30–34 | 0.0652*** | 0.0365 | 0.0100 | 0.0004 | 0.15 | |

| 35–39 | 0.0760*** | 0.0375 | 0.0046 | 0.0002 | 0.07 | |

| 40–44 | 0.0885*** | 0.0342 | − 0.0078 | − 0.0003 | − 0.11 | |

| 45–49 | 0.0895*** | 0.0271 | − 0.0149 | − 0.0004 | − 0.16 | |

| Sub-total | 0.12 | |||||

| Educational level | No formal education | |||||

| Primary | 0.0131*** | 0.0153 | − 0.1261 | − 0.0019 | − 0.77 | |

| Secondary | 0.0320*** | 0.0464 | 0.2999 | 0.0139 | 5.57 | |

| Higher | 0.0879*** | 0.0237 | 0.1515 | 0.0036 | 1.43 | |

| Sub-total | 6.23 | |||||

| Wealth quintile | Quintile 1 | |||||

| Quintile 2 | 0.0148*** | 0.0107 | − 0.3476 | − 0.0037 | − 1.48 | |

| Quintile 3 | 0.0204*** | 0.0158 | − 0.0829 | − 0.0013 | − 0.52 | |

| Quintile 4 | 0.0322*** | 0.0278 | 0.2616 | 0.0073 | 2.91 | |

| Quintile 5 | 0.0521*** | 0.0502 | 0.7309 | 0.0367 | 14.67 | |

| Sub-total | 15.58 | |||||

| Employment status | Not employed | |||||

| Employed | 0.0046*** | 0.0103 | 0.0040 | 0.0000 | 0.02 | |

| Sub-total | ||||||

| Marital status | Never in union | |||||

| Currently in union | 0.0542*** | 0.1324 | − 0.1382 | − 0.0183 | − 7.32 | |

| Formerly in union | 0.0579*** | 0.0224 | − 0.0124 | − 0.0003 | − 0.11 | |

| Sub-total | −7.43 | |||||

| Sex of household head | Female | |||||

| Male | − 0.0078*** | − 0.0220 | − 0.0415 | 0.0009 | 0.37 | |

| Media exposure | No | |||||

| Yes | 0.0394*** | 0.1140 | 0.4370 | 0.0498 | 19.94 | |

| Place of residence | Rural | |||||

| Urban | 0.0044** | 0.0082 | 0.6624 | 0.0055 | 2.18 | |

| Perceived distance to health facility | Big problem | |||||

| Not a big problem | − 0.0004 | − 0.0009 | 0.3157 | − 0.0003 | − 0.12 |

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05.

The significant values are in bold.

Discussion

The current study aimed to assess the socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake and identify the contributing factors among women of reproductive age in SSA. Consistent with previous research18,19,29,30, cervical cancer screening uptake was found to be disproportionately higher among women from wealthier households.

The observed socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake among women in Sub-Saharan Africa can be attributed to several factors. Women in wealthier households often have better access to healthcare facilities and services, including cervical cancer screening, due to proximity and means of transportation31. Higher levels of education among these women contribute to greater awareness of the importance of early detection and preventive care. Additionally, wealthier households are more likely to have health insurance, making healthcare services more accessible32. Cultural and social factors also play a role, as certain communities may have misconceptions or stigma surrounding cervical cancer screening, deterring women from seeking these services. Financial constraints, lack of transportation, and competing responsibilities further prevent women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds from accessing screening services33. Lastly, inadequate healthcare infrastructure in rural or underserved areas limits the availability of these services, disproportionately affecting poorer women. Addressing these factors requires comprehensive strategies, including improving healthcare infrastructure, increasing education and awareness, and implementing policies to reduce financial barriers to screening services.

The decomposition analysis revealed that media exposure, educational status, wealth index, and place of residence significantly contribute to the pro-rich socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening among women in SSA.

Media exposure was identified as the most significant contributor to the overall socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake, accounting for 19.94% of the disparity. This finding is supported by previously done studies in 18 resource-constrained countries10. The possible explanation can be, that wealthier households tend to have better access to various media platforms, such as television, radio, and the internet, where health information is frequently disseminated34. Health awareness campaigns, educational programs, and public health messages broadcasted through media channels influence health-seeking behaviors, benefiting those with greater media access35. Additionally, individuals from wealthier backgrounds often possess higher literacy levels, enhancing their ability to comprehend and act upon health information received through media36. Regular exposure to health messages can reinforce positive health behaviors, and wealthier individuals are more likely to be receptive to and act on these messages. Moreover, media exposure can strengthen social networks and community norms regarding health behaviors, leading to higher screening rates in wealthier communities. Addressing this disparity requires targeted health campaigns that reach lower socioeconomic groups through accessible channels and clear, relatable messaging, thereby improving awareness and access across all socioeconomic strata.

Following media exposure, the wealth index was identified as another significant contributor to the overall socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening utilization (15.58%). This can be attributed to the fact that wealthier individuals typically have better access to healthcare services, including screening facilities, and can afford transportation to these locations37. They are more likely to have health insurance, which covers the costs of screening38. Additionally, higher levels of education and health literacy among wealthier individuals enable them to understand the importance of preventive health measures and act upon health information received through media and other sources39.

In line with previous studies19,40–42, the highest rates of screening were among women with formal education. Lower levels of education are often linked to reduced health literacy, making it difficult for individuals to grasp health education messages and instructions43,44. In the context of cervical cancer screening, this means they might not fully understand the importance of screening, their eligibility, or where to access screening services. It’s crucial to develop cervical cancer education materials that cater to individuals with diverse educational backgrounds. Tailoring these materials ensures that everyone, regardless of their education level, can understand the importance of screening, recognize their eligibility, and know where to access services. This approach promotes inclusivity and helps bridge the gap in health literacy.

Urban residence significantly contributes to the pro-rich socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening among women in SSA due to several factors. Urban areas typically offer more healthcare facilities and better infrastructure, making screening services more accessible45. Higher levels of health literacy and exposure to health education campaigns in urban settings increase awareness of screening importance. Additionally, urban residents generally have higher incomes, which enable them to afford the costs associated with screening46–48. Social networks in urban areas also play a role, as they often emphasize preventive health measures49. These disparities highlight the need for targeted efforts to improve healthcare access and education in rural areas to ensure equitable screening opportunities for all women.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this study lies in its use of data from nationally representative surveys, providing a population-level estimate of cervical cancer screening in these countries at the time of the surveys. However, the reported inequalities may not fully capture the regional disparities within individual countries.

Conclusion

To bridge the gap in cervical cancer screening rates in SSA, it is recommended to implement targeted awareness campaigns for low-income groups, subsidize or provide free screening services, deploy mobile units to rural areas, and enhance health literacy through educational programs. Training community health workers and advocating for policy changes to include cervical cancer screening in national health agendas are also crucial. These strategies aim to ensure equitable healthcare access across all socioeconomic groups. Additionally, socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in the disparities observed in cervical cancer screening uptake among women of reproductive age in SSA. Media exposure is the most substantial contributor, accounting for 20% of the pro-rich inequalities. Wealth index and educational status also play crucial roles, contributing 15.58% and 6.23% to these disparities, respectively. Moreover, place of residence adds another 2.18% to the inequalities. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions that address these socioeconomic determinants to promote equitable access to cervical cancer screening across different population groups. The data calls for comprehensive strategies to increase media outreach, improve education on health services, and ensure accessible healthcare facilities in both urban and rural areas.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the measure DHS program for providing the data set.

Author contributions

Conception of the work, design of the work, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data was done by; BLS. Data curation, drafting the article, revising it critically for intellectual content, validation, and final approval of the version to be published was done by; BLS, BMF, ZAA, AAA, MMB, HAA, MM, AKG, SST, and YMN. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data is available online and it can be accessed from https://www.measuredhs.com/.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study doesn’t involve the collection of information from subjects. Consent to participate is not applicable. Since the study is a secondary data analysis based on DHS data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhang, M. et al. Analysis of the global burden of cervical cancer in young women aged 15–44 years old. Eur. J. Public Health34 (4), 839–846 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dochez, C., Bogers, J. J., Verhelst, R. & Rees, H. HPV vaccines to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts: an update. Vaccine32 (14), 1595–1601 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervical Cancer [Internet]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwg-24BhB_EiwA1ZOx8kEk2fUG8p3BN6YZ_x6P1O5NFQwJPA-YWLDJzt1wp6EXDakzQSIOjhoCjZ0QAvD_BwE (2024).

- 4.Almonte, M. et al. From commitments to action: the first global cervical cancer elimination forum. Lancet Reg. Health Americas36, 812. 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100812 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Forum Strengthens Commitments Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination—NCI [Internet]. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/cgh/blog/2024/global-cervical-cancer-forum#r2 (2024).

- 6.Singh, D. et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO global cervical cancer elimination initiative. Lancet Glob. Health11 (2), e197–e206 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basoya, S. & Anjankar, A. Cervical cancer: early detection and prevention in reproductive age group. Cureus14 (11), e31312 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrossi, S. et al. Primary prevention of cervical cancer: American society of clinical oncology Resource-Stratified guideline. J. Glob. Oncol.3 (5), 611–634 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem (World Health Organization, 2020).

- 10.Mahumud, R. A. et al. Wealth-related inequalities of women’s knowledge of cervical cancer screening and service utilisation in 18 resource-constrained countries: evidence from a pooled decomposition analysis. Int. J. Equity Health. 19 (1), 42 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cervical Cancer Screening—NCI [Internet]. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/screening (2022).

- 12.Bruni, L. et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health10 (8), e1115–e1127 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emadi, M., Delavari, S. & Bayati, M. Global socioeconomic inequality in the burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases and injuries: an analysis on global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health. 21 (1), 1771 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chipanta, D. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cervical precancer screening among women in Ethiopia, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe: analysis of population-based HIV impact assessment surveys. BMJ Open13 (6), e067948 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantula, F., Toefy, Y. & Sewram, V. Barriers to cervical cancer screening in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 24 (1), 525 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abila, D. B. et al. Coverage and socioeconomic inequalities in cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries between 2010 and 2019. JCO Glob. Oncol.10, e2300385 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen, Z. et al. Barriers to uptake of cervical cancer screening services in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Women’s Health22 (1), 486 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chirwa, G. C. Explaining socioeconomic inequality in cervical cancer screening uptake in Malawi. BMC Public Health22 (1), 1376 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abila, D. B. et al. Coverage and socioeconomic inequalities in cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries between 2010 and 2019. JCO Glob. Oncol.10, e2300385 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viens, L., Perin, D., Senkomago, V., Neri, A. & Saraiya, M. Questions about cervical and breast cancer screening knowledge, practice, and outcomes: A review of demographic and health surveys. J. Women’s Health. 26 (5), 403–412 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu, K. Analysing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Bull. World Health Organ.86, 816 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Croft, T. N. et al. Guide To DHS Statistics (ICFCroft, 2023).

- 23.Kakwani, N., Wagstaff, A. & Van Doorslaer, E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J. Econ.77 (1), 87–103 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yitzhaki, S. & Schechtman, E. The Lorenz Curve and the Concentration Curve 75–98 (Springer, 2013).

- 25.O’Donnell, O., O’Neill, S., Van Ourti, T., Walsh, B. & Conindex Estimation of concentration indices. Stata J.16 (1), 112–138 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagstaff, A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ.14 (4), 429–432 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ataguba, J. E. A short note revisiting the concentration index: does the normalization of the concentration index matter? Health Econ.31 (7), 1506–1512 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell, O. et al. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data (2007).

- 29.Keetile, M. et al. Factors associated with and socioeconomic inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening among women aged 15–64 years in Botswana. PLoS ONE16 (8), e0255581 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, Y., Guo, J., Zhu, G., Zhang, B. & Feng, X. L. Changes in rate and socioeconomic inequality of cervical cancer screening in Northeastern China from 2013 to 2018. Front. Med.9, 1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickson, K. S., Boateng, E. N. K., Acquah, E., Ayebeng, C. & Addo, I. Y. Screening for cervical cancer among women in five countries in sub-saharan Africa: analysis of the role played by distance to health facility and socio-demographic factors. BMC Health Serv. Res.23 (1), 61 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saaka, S. A. & Hambali, M. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening among women of reproductive age in Ghana. BMC Women’s Health24 (1), 519 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lott, B. E. et al. Interventions to increase uptake of cervical screening in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review using the integrated behavioral model. BMC Public Health20 (1), 654 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, D. et al. Access to digital media and devices among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A multicountry, school-based survey. Maternal Child. Nutr.1, e13462 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson, J. O., Mullins, R. M., Siahpush, M., Spittal, M. J. & Wakefield, M. Mass media campaign improves cervical screening across all socio-economic groups. Health Educ. Res.24 (5), 867–875 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Health information: are you getting your message across? Health Soc. Care Serv. Res.1, 1–11 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collegenp Money and Health: The Impact of Wealth on Well-Being (2023).

- 38.Levy, H. & Meltzer, D. The impact of health insurance on health. Annu. Rev. Public Health29, 399–409 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Der Heide, I. et al. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch adult literacy and life skills survey. J. Health Commun.18, 172–184 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, W. et al. Associated factors and global adherence of cervical cancer screening in 2019: a systematic analysis and modelling study. Glob. Health18 (1), 101 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akoto, E. J. & Allsop, M. J. Factors influencing the experience of breast and cervical cancer screening among women in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. JCO Glob. Oncol.9 (9), e2200359 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yimer, N. B. et al. Cervical cancer screening uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health195, 105–111 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratzan, S. C. Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promot. Int.16 (2), 207–214 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Codina, O. et al. Determinants of health literacy in the general population: results of the Catalan health survey. BMC Public Health19 (1), 1122 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassa, R. N., Shifti, D. M., Alemu, K. & Omigbodun, A. O. Integration of cervical cancer screening into healthcare facilities in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLoS Glob. Public Health4, e0003183 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chepkorir, J. et al. The role of health information sources on cervical cancer literacy, knowledge, attitudes and screening practices in Sub-Saharan African women: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health21, 1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebu, N. I., Amissah-Essel, S., Asiedu, C., Akaba, S. & Pereko, K. A. Impact of health education intervention on knowledge and perception of cervical cancer and screening for women in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 19 (1), 1505 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim, K. & Han, H. R. Potential links between health literacy and cervical cancer screening behaviors: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology25 (2), 122–130 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Direito, B. A. Social Networks as Influencers of Health Behavior Change 1–6 (2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available online and it can be accessed from https://www.measuredhs.com/.