Abstract

Purpose

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKHS), characterized by congenital uterine and vaginal aplasia, lacks definitive etiology. Discordant monozygotic (MZ) twins provide a unique model to dissect postzygotic drivers of phenotypic divergence. This study aimed to identify postzygotic mutations (SNVs, Indels, CNVs, SVs) underlying MRKHS discordance and redefine its molecular etiology.

Methods

Whole-genome and exome sequencing (WGS/WES) were performed on blood-derived DNA from MRKHS discordant MZ twins. Variant detection utilized VarScan2, GATK, BreakDancer, and CNVnator, with stringent filtering for somatic mutations. Putative discordant variants were validated via Sanger sequencing.

Results

High-coverage sequencing (mean WGS: 66.2x–68.2x; WES: 94.5x–126.6x) revealed four low-quality discordant SNVs, none of which were validated by Sanger sequencing. No pathogenic CNVs/SVs were detected, including in genes critical to Müllerian development (e.g., WNT4, LHX1). Blood-derived DNA analysis failed to identify high-penetrance coding mutations or tissue-specific mosaicism.

Conclusions

The absence of validated postzygotic mutations challenges coding variants as primary MRKHS drivers. Findings implicate Müllerian-restricted somatic mosaicism or epigenetic dysregulation (e.g., WNT4/LHX1 methylation) during embryogenesis, undetectable in peripheral blood. This underscores limitations of blood-based genomics and highlights the need for non-invasive biomarkers (e.g., cfDNA methylation) and prenatal environmental risk mitigation (e.g., endocrine disruptor avoidance). The study advocates integrating tissue-specific multi-omics and patient derived organoids to resolve MRKHS mechanisms, guiding fertility preservation and personalized reproductive interventions.

Keywords: MRKH syndrome, Monozygotic discordant twins, Postzygotic mutation, Somatic mosaicism, Epigenetic dysregulation, Non-invasive biomarkers

Introduction

The Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKHS) (OMIM 277000) is a congenital malformation of the female reproductive tracts. It influences 1 in every 4500 female live births and is one of the most common causes of primary amenorrhea. The MRKHS is characterized by congenital absence of the uterus and the upper two-thirds of the vagina in females with normal secondary sexual characteristics and a 46, XX karyotype [1]. In addition to its impact on physical performance, MRKHS imposes a substantial social and psychological burden, encompassing issues related to infertility, challenges in gender identity, and sexual health concerns. Despite its clinical significance, the underlying cause of MRKHS remains a critical enigma in reproductive medicine, which impedes progress in prevention, diagnosis, and personalized therapies.

The etiology of MRKHS stays obscure [2]. Emerging evidence continues to delineate a complex etiological landscape for MRKHS, where genetic predisposition, epigenetic dysregulation, and environmental exposures interact through poorly understood mechanisms. While genome-wide association studies have identified sporadic variations in developmental regulators such as WNT4 and HOX gene clusters [3, 4], the absence of replicable high-penetrance germline mutations challenges conventional Mendelian inheritance models. The epigenetic hypothesis, particularly the proposed methylation aberrations in LHX1 and PAX2 observed in murine models, remains clinically unsubstantiated due to the inherent inaccessibility of human embryonic Müllerian tissue for molecular analysis. Experimental teratology provides mechanistic plausibility for environmental contributors, notably prenatal exposure to endocrine disruptors (e.g., bisphenol A) and retinoid pathway dysregulation [5], yet these findings await validation through large-scale longitudinal human studies with precise exposure quantification [6]. A critical knowledge gap persists in reconciling these etiological fragments, primarily constrained by the tissue-specific pathogenesis of Müllerian agenesis. The developmental window of Müllerian duct formation (embryonic weeks 6–10) presents unique challenges for human developmental biology research. Current diagnostic paradigms relying on peripheral blood DNA analysis fundamentally limit the detection of somatic mosaicism (tissue-specific mutations arising during embryonic cell divisions) and tissue-specific epigenetic signatures, while the surgical procurement of residual Müllerian tissues poses substantial ethical and technical constraints in postnatal investigations. This methodological impasse necessitates innovative approaches to study early embryonic development indirectly.

Discordant monozygotic (MZ) twins, sharing > 99% of their germline genome yet exhibiting divergent phenotypes, challenge a purely genetic basis for this syndrome [7–10] and offer a transformative model to dissect MRKHS’ origins [11]. MZ twin discordance isolates postzygotic drivers—such as somatic mutations, epigenetic drift (stochastic changes in DNA methylation patterns), or transient environmental exposures—as key mediators of phenotypic divergence [12]. The underlying genetic differences may arise during embryonic development, for example, single-nucleotide mutations, deletions, conversion, CNVs, and postzygotic mitotic recombination. These variations have been suggested as possible genetic mechanisms that cause discordant monozygotic twins. This paradigm has elucidated congenital heart disease and neural tube defects [13], where twin studies revealed placental epigenetic anomalies and mosaicism as critical mechanisms [14–18]. In MRKHS, however, this powerful approach remains underexplored, despite its unique capacity to disentangle genetic homogeneity from developmental noise.

Driven by the hypothesis that there were genetic differences of postzygotic mutations resulting in the discordant phenotypes of MRKHS, we reported a pair of MRKHS-discordant monozygotic twins and used whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing (WGS/WES) to scan such genetic differences. While no pathogenic germline variants were identified, this negative finding holds pivotal clinical implications. First, it challenges the presumption of high-penetrance coding mutations as a primary etiology, redirecting focus toward tissue-specific somatic mosaicism or dynamic epigenetic-environmental interplay during embryogenesis. Second, it underscores the limitations of blood-based analyses and advocates for innovations such as patient-derived Müllerian organoids and placental methylome profiling to resolve mechanisms like HOXA dysregulation or retinoid signaling defects. Third, it highlights the urgency of integrating non-genetic counseling into clinical practice, emphasizing prenatal environmental risk mitigation (e.g., endocrine disruptor avoidance) and psychosocial support tailored to MRKHS’ unique challenges.

For assisted reproduction, these insights are transformative. Current interventions, such as uterine transplantation, face high failure rates due to incomplete understanding of MRKHS’ molecular drivers. Our findings advocate for non-invasive prenatal biomarkers (e.g., cell-free fetal DNA methylation signatures) to identify at-risk pregnancies and patient-specific regenerative therapies leveraging induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). By bridging genetics, developmental biology, and clinical care, this study pioneers a roadmap to decode multifactorial congenital anomalies and personalize reproductive health strategies.

In conclusion, leveraging discordant MZ twins not only advances MRKHS research but also establishes a replicable framework for investigating enigmatic congenital disorders. This work underscores the imperative of multidisciplinary collaboration, prioritizing innovations in non-invasive diagnostics, epigenetics, and patient-centered care to transform outcomes in reproductive medicine.

Materials and methods

Participants

The pair of monozygotic twins were enrolled in September 2011 during a multi-centric study of MRKH syndrome. All participants were informed about the study and signed the consent form approved by the Ethical Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. And this study was carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Description of the monozygotic twins

This patient was sent to us with primary amenorrhea and abnormal genitalia when she was 17 years old. She weighed 41 kg and was 151 cm tall, showing normal female secondary sex characteristics: the enlargement of breasts and erection of nipples, the distribution of body hair, and the widening of hips. Physical examination revealed normal external genitalia, but the vagina was a 2-cm-deep dimple. In the combined rectal examination, the pelvis was noted to be free. A pelvic ultrasonography suggested a rudimentary uterus without a hyperechogenic line, no imaging of the vagina, but normal ovaries. The ultrasound examinations did not show any anomalies with abdominal organs or heart. The X-rays of the whole skeleton resulted negative. Endocrine tests revealed a normal level of FSH at 8.44 mIU/mL, LH at 5.57 mIU/mL, E2 at 5.9 pg/mL, and TESTO at 0.13 ng/mL. Karyotyping, on cultured peripheral blood lymphocytes according to standard procedure, was tested to be 46,XX. A laparoscopic vaginoplasty of the peritoneum was performed on July 21, 2011. Laparoscopic observation showed complete uterus aplasia in the presence of two rudimentary horns linked by a peritoneal fold and normal Fallopian tubes. The position and shape of the ovaries seemed normal.

In contrast, the monozygotic twin sister unaffected with MRKH syndrome was in good health. She had given a natural birth to a healthy baby boy. Physical examination, endocrine tests, and imaging tests showed no abnormal changes.

The mother was aged 24 years, and the father was 25 years old at the time of the spontaneous pregnancy. There were no special events throughout the pregnancy, such as hyperemesis gravidarum, pregnancy hypertension, drug use, radiative rays, or other deleterious substance contact. The mother lived healthily, and her menstruation cycled regularly. The living habits of the parents were uneventful for risk factors, such as alcohol and tobacco use and drug or hormone intake. Family history was negative regarding genetic disease, especially abnormalities of the reproductive system.

Genome sequencing and targeted capture exome sequencing

The total genomic DNA (gDNA) of the monozygotic twins was extracted from 200 µL peripheral blood using the FujiFilm Quick Gene DNA whole blood kit S according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and purity of the gDNA were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis and the optical density (OD) ratio.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed using the SureSelect Human All Exon 50 M kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), and the captured DNA molecules were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000 (Illumina), generating 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads. The whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was directly performed on an Illumina HiSeqX10 (Illumina), generating 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads.

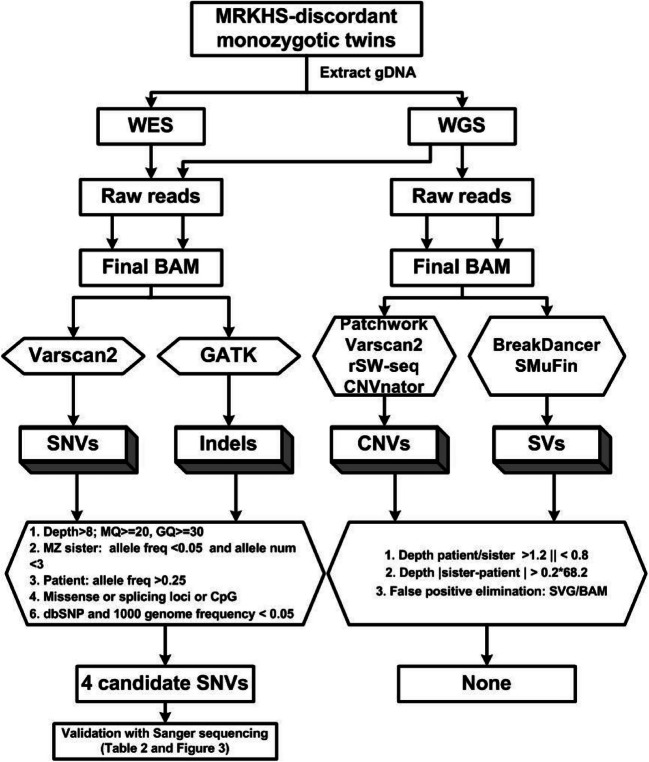

Firstly, raw reads were mapped to the latest reference human genome (GRCh37/hg19) by BWA software [19]. Secondly, Picard was performed to mark duplicates, and GATK was used to do the insertion or deletion (Indels) realignment and base quality recalibration. After that, we acquired the final BAM files which could be utilized to call different somatic variations with different programs, as shown in Fig. 1. Variant calling was done simultaneously on both alignment data from the MRKHS patient and her monozygotic sister. VarScan2 [20] was used for somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) calling and GATK for somatic indels. In order to detect somatic copy number variation (CNV) as much as possible, four CNV calling software programs (Patchwork [21], Varscan2, rSW-seq [22], and CNVnator [23]) were utilized. Every candidate CNV was verified by hand inspection with sequencing depth and GC content. Both BreakDancer [24] and SMuFin [25] were used to detect the somatic structure variation (SV), and split-read and depth were considered to conform to the somatic SV.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the process of combining the whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data. SNVs, single-nucleotide variations; Indels, small insertion or deletions; CNVs, copy number variations; SVs, structure variations; MZ sister, monozygotic twin sister

The basic quality controls for SNVs and indels were the sequencing depth greater than 8 × , MQ ≥ 20, and GQ ≥ 30, and they were not located at the start or end position of reads. Discordant SNVs and indels between the monozygotic twins were appointed as candidate SNVs and indels when the variant frequency was greater than 0.25 in the patient but less than 0.05 in her monozygotic sister and allele depth smaller than 3. These resulting discordant candidate variants were filtered again by excluding common SNPs (allele frequencies in dbSNP or 1000 Genomes Project < 0.05) and non-functional ones, such as synonymous variants, variants locating outside regions like exon, splicing, or CpG. After that, variants with a depth of more than 20 in both of the monozygotic twins were taken as the high-quality candidates, while others were regarded as low-quality candidates.

We applied BreakDancer and SMuFin (using default parameters) to detect SVs and Patchwork, VarScan2, rSW-seq, and CNVnator for CNVs. Filtering metrics were as follows: the depth ratio of patient/MZ sister > 1.2 or < 0.8 and the difference of depth in patient and MZ sister > 0.2 × 68.2 (mean read depth of whole genome in MZ sister). These were manually rechecked using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software.

Putative discordant SNVs/Indels validation

To avoid false positive variants, each of the resulting variants from both whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing was visualized along with its alignment data from both twins using IGV software. The putative discordant mutations were validated via Sanger sequencing of the monozygotic twins and their mother. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified the genomic DNA using primers specific for the detected discordant variants. Sanger sequencing was performed in the PCR products. The required sequences were analyzed on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), aligned to the human genome (GRCh37/hg19) by BLAST, and compared among the monozygotic twins and their mother to verify the discordant variation.

Results

The exome sequencing obtained 8.3 Gb and 10.8 Gb of raw data for the patient and the monozygotic sister, showing a mean target region coverage of 94.54-fold and 126.57-fold. The whole-genome sequencing of both twins resulted in 66.2 × and 68.2 × of mean coverage of the whole genome (Table 1). Besides, we assessed the base content distribution, depth distribution of sequencing, quality of sequencing, and sequencing error distribution of the whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing. Both showed good performance (Fig. 2). After the stringent quality control and filtering criteria, only four putative discordant low-quality variants (four SNVs) were obtained from the SNVs/Indels data (Table 2). All the four SNVs were not detected in any reads of the MZ sister. But, in the gDNA of the MRKHS patient, the frequencies of the putative SNVs were greater than 25%. A nonsynonymous SNV c.3755 T > C in exon 3 of HRNR, namely, the rs201047229, resulting in a substitution of leucine to serine at residue 1252 was found in 50% reads (5 of 10 reads). The rs371473316 and rs62350341, located in ncRNA regions, were found mutant in 66.67% and 25% reads in the patient. Besides, in the region of CpG:827 (Chr9: 138,150,966 ~ 138,150,966), we detected the SNVs rs202082918 in 39.13% reads.

Table 1.

Summary of sequencing results from whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing data

| Hiseq 2500 whole-genome sequencing | MRKHS patient | Zygotic sister |

|---|---|---|

| 220 Gb | 226 Gb | |

| Genomic bases covereda | 98.65 | 98.66 |

| Haploid coverageb | 66.2 | 68.2 |

| Exon coveragec | 62.4 | 64.1 |

| Coding bases coveredd | 95.7 | 95.7 |

| Mean read depth of whole genome | 66.2 | 68.2 |

| % Coverage of target regions (> 10 ×) | 98.65 | 98.21 |

| Hiseq 2000 whole-exome sequencing | MRKHS patient | Zygotic sister |

| Size of genome | ||

| Total yield (base pair) | 8.3 Gb | 10.8 Gb |

| On-target base pair (mapped to target regions) | 4.7 Gb | 6.4 Gb |

| Mean read depth of target regions | 94.54 | 126.57 |

| % Coverage of target regions (> 10 ×) | 94.5 | 95.2 |

a%Genomice bases covered: the % of all non-ambiguous bases covered at least 10 ×

bHaploid coverage: the average coverage of all non-ambiguous bases in hg18 or hg19, respectively

cExon coverage: the average of all exonic bases (also including all non-coding RNAs annotated in RefSeq)

d%Coding bases covered: the % of all RefSeq protein-coding bases, which are covered to at least 10 ×

Fig. 2.

Data quality of whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing. A Base content distribution; B depth distribution of sequencing; C quality of sequencing; D sequencing error distribution

Table 2.

Putative discordant variation

| SNP | Gene | Type | Position | Genotype | Depth of patient | Freq. patient | Depth of MZ sister | Freq. MZ sister | Sanger sequencing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | Var | Ref | Var | Ref | Var | Patient | MZ sister | Mother | ||||||

| rs201047229 | HRNR | Nonsyn | Chr1: 152,190,350 | A | G | 5 | 5 | 50.00% | 14 | 0 | 0 | G/G | G/G | G/G |

| rs371473316 | LOC100132287 | ncRNA | Chr1: 327,125 | G | A | 4 | 8 | 66.67% | 11 | 0 | 0 | G/G | G/G | G/G |

| rs62350341 | F11-AS1 | ncRNA | Chr4: 187,293,176 | A | G | 15 | 5 | 25.00% | 20 | 0 | 0 | A/G | A/G | G/G |

| rs202082918 | LOC401557 | CpG | Chr9: 138,150,966 | T | C | 14 | 9 | 39.13% | 20 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

Using conventional Sanger sequencing, no variant was discordant between the monozygotic twins. As shown in Table 2, rs201047229 was sequenced to be homozygous G/G in both the twins and their mother (Fig. 3). Neither variant was detected at the locus of rs371473316 in the MRKHS patient, her sister, or her mother (Fig. 3). Heterozygous A/G was validated in the MRKHS patient, but also in her monozygotic sister (Fig. 3). However, their mother possessed the homozygous G/G of the SNP rs62350341. The SNP rs202082918 is located in simple tandem repeats with a period of 28 bases cycling 32 times, which were identified by the Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF). We have experimented with several ways to amplify the special region, but no one worked. As a result, we failed to verify any discordant SNVs/Indels in the patient with MRKH syndrome.

Fig. 3.

Validation of candidate variants. Electropherograms of Sanger sequencing of the 3 putative discordant variants between the patient with MRKH syndrome and her monozygotic twin sister (MZ sister) identified by either whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing experiments. The third line represented their biological mother, respectively. The putative loci were indicated by the black arrows

No differences in CNV patterns were found between the monozygotic twins. The reported recurrent CNVs in patients with Müllerian aplasia were not detected in our patient. Moreover, no relevant CNVs were found in the chromosomal regions containing genes relevant to the embryonic development of the female genital tract, such as the WNT genes. Regions containing candidate genes, such as PBX1, LHX1, and AMH, were also screened without detecting any relevant CNVs. Furthermore, no relevant genomic rearrangements were identified specifically existing in the twin with MRKH syndrome.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized NGS to sequence the whole genome and exome of the MRKHS-discordant monozygotic twins. Four low-quality SNVs were discordant between the monozygotic twins potentially causing the congenital defects. However, validation of these 4 variants via Sanger sequencing showed no differences between the monozygotic twins. This negative result holds pivotal implications for both reproductive genetics and clinical practice. By leveraging the unique natural experiment of MZ twins—who share nearly identical inherited genomes but diverge phenotypically—this study challenges the long-standing hypothesis that high-penetrance coding mutations dominate MRKHS etiology. Instead, our findings underscore the likely contribution of postzygotic mechanisms, such as somatic mosaicism in Müllerian precursors or epigenetic dysregulation, which evade detection in blood-derived DNA. Critically, the inability to directly analyze Müllerian tissue—a fundamental limitation in MRKHS research—precludes definitive validation of such mechanisms. Surgical retrieval of residual Müllerian remnants (e.g., fibrous uterine bands) is rarely feasible due to their atrophic nature and high-risk anatomical location near pelvic vasculature and organs, while ethical constraints prohibit invasive procedures lacking therapeutic benefit. Furthermore, embryonic Müllerian tissues, which undergo developmental arrest by birth, are irrecoverable postnatally. These barriers necessitate reliance on indirect approaches, as employed here, but also highlight the imperative for innovative alternatives.

A key limitation of this study lies in the reliance on peripheral blood DNA, which inherently restricts the detection of tissue-specific somatic variants or epigenetic alterations. Blood-derived DNA primarily reflects hematopoietic lineages and cannot capture mutations or methylation anomalies specific to Müllerian duct-derived tissues (e.g., uterine stroma or vaginal epithelium). For instance, low-frequency mosaicism (< 5% variant allele frequency) in Müllerian precursors—a plausible mechanism for twin discordance—would remain undetected at standard sequencing depths (< 100 ×). Prior studies in congenital disorders (e.g., focal cortical dysplasia) demonstrate that pathogenic somatic variants confined to non-hematopoietic tissues are systematically missed in blood-based analyses, potentially explaining our negative findings [26, 27]. Secondly, blood methylomes diverge markedly from reproductive tissues; thus, epigenetic perturbations critical to Müllerian development (e.g., HOXA cluster hypermethylation) cannot be inferred from peripheral blood.

Notably, 70% of MZ twins exhibit monochorionic placentation with shared blood circulation, leading to hematopoietic chimerism. This biological phenomenon may mask twin-specific somatic mutations in blood DNA, as hematopoietic stem cells carrying postzygotic variants could transfer between twins. Consequently, pathogenic mutations restricted to Müllerian tissues in the affected twin may remain undetectable in both twins’ blood, necessitating alternative biospecimen strategies. This will mask the underlying mutations causing the disease in the affected twin.

Notably, the phenotypic discordance observed in MZ twins strongly implicates environmental and epigenetic modifiers as pivotal contributors to MRKHS pathogenesis [28]. Animal models and epidemiological studies suggest that in utero exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (e.g., bisphenol A, diethylstilbestrol) may interfere with Müllerian duct elongation via altered estrogen receptor signaling or retinoid acid metabolism. Similarly, maternal hyperandrogenism or vitamin A deficiency during the critical developmental window (weeks 6–12) could disrupt epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk essential for ductal patterning. Epigenetically, dynamic DNA methylation at loci such as WNT4 or LHX1—genes governing Müllerian duct specification—may mediate stochastic developmental plasticity. For example, murine studies demonstrate that transient hypermethylation of Wnt4 enhancers in mesenchymal cells suppresses Müllerian duct growth, a mechanism potentially conserved in humans but undetectable in blood DNA. These findings align with the “developmental origins of health and disease” (DOHaD) paradigm, wherein transient environmental or epigenetic perturbations during embryogenesis yield permanent structural anomalies.

For assisted reproduction, these results emphasize the need to expand diagnostic paradigms beyond traditional genetic screening. While WGS/WES of blood remains a cornerstone of preconception counseling, its limitations in MRKHS highlight the urgency of integrating tissue-specific multi-omics—for example, epigenetic profiling of residual Müllerian remnants or placental-fetal interface analyses—to unravel mechanisms influencing uterine development. Notably, recent advances in Müllerian organoid models derived from patient-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) may circumvent tissue accessibility challenges, enabling in vitro interrogation of developmental pathways. Such approaches could inform risk stratification for interventions like uterine transplantation or stem cell–based regenerative therapies, where understanding molecular heterogeneity is critical to success. Furthermore, the absence of germline variants in discordant twins reinforces the importance of non-genetic counseling components, including discussions on environmental modulators (e.g., prenatal endocrine disruptors) and psychosocial support for fertility-related distress.

Future research should prioritize single-cell spatial omics (which can resolve the spatiotemporal dynamics of gene expression in cell subsets) of Müllerian organoids to map spatiotemporal gene regulatory networks disrupted in MRKH, alongside longitudinal studies of discordant twins to capture dynamic epigenetic or environmental exposures. Collaborative efforts to establish biobanks of surgical specimens (e.g., fibrous uterine remnants) and harmonized phenomic data (e.g., 3D pelvic imaging, endocrine profiles) will be essential to power hypothesis-driven discovery. Importantly, the ethical and technical hurdles of procuring Müllerian tissue underscore the value of non-invasive strategies, such as circulating cell-free DNA methylation analysis (cfDNA, fragmented DNA released into the bloodstream through apoptosis or active secretion, carries tissue-specific methylation patterns that may reflect developmental perturbations in inaccessible organs like the uterus) or exosome-based biomarkers (extracellular vesicles carrying tissue-specific nucleic acids), to infer tissue-specific changes. Our study illustrates how negative genetic findings in rare disorders can catalyze paradigm shifts—redirecting focus from gene-centric frameworks to integrated developmental models that reconcile genetic homogeneity with phenotypic discordance.

Clinically, these insights advocate for a dual strategy: advancing non-invasive biomarkers (e.g. cell-free DNA methylation signatures) for early detection, while refining patient-centered care pathways that address MRKHS’ multifactorial origins. By bridging gaps between reproductive genetics and developmental biology, this work aligns with the mission of the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics to translate mechanistic insights into tangible advances for fertility preservation and family building.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients and volunteers who participated in the study and to all of their colleagues for their contributions to the physical examinations of patients and the collection of samples.

Author contribution

Wenqing Ma and Fangfang Fu contributed to study concept and design and interpretation of the data, composed the statistical dataset, performed the analyses, and wrote and revised the manuscript. Fangfang Fu, Wenwen Wang, and Xiangyi Ma were responsible for the follow-up of subcenters and collection of clinical data. Man Wang contributed to interpreting the data and critical revision of the manuscript. Shixuan Wang and Yan Li contributed to interpreting the data and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version, and no other person made a substantial contribution to the paper.

Funding

The study is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC2009100).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China (reference no. 2011-S463).

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent, and all methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Man Wang, Email: grace_wangman@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Yan Li, Email: liyan@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Herlin MK. Genetics of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome: advancements and implications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1368990. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1368990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dube R, Kar SS, Jhancy M, George BT. Molecular basis of Mullerian agenesis causing congenital uterine factor infertility-a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25. 10.3390/ijms25010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Pizzo A, Lagana AS, Sturlese E, Retto G, Retto A, De Dominici R, Puzzolo D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: embryology, genetics and clinical and surgical treatment. ISRN obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;2013:628717. 10.1155/2013/628717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morcel K, Camborieux L. Programme de Recherches sur les Aplasies M, Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:13. 10.1186/1750-1172-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Simpson JL. Genetics of the female reproductive ducts. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:224–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Frias ML, Bermejo E, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Prieto L, Frias JL. Epidemiological analysis of outcomes of pregnancy in gestational diabetic mothers. Am J Med Genet. 1998;78:140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinkampf MP, Dharia SP, Dickerson RD. Monozygotic twins discordant for vaginal agenesis and bilateral tibial longitudinal deficiency. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:643–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidenreich W, Pfeiffer A, Kumbnani HK, Scholz W, Zeuner W. Disordant monozygotic twins with Mayer Rokitansky Kutser syndrome (author’s transl). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1977;37:221–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lischke JH, Curtis CH, Lamb EJ. Discordance of vaginal agenesis in monozygotic twins. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;41:920–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duru UA, Laufer MR. Discordance in Mayer-von Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome noted in monozygotic twins. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:e73-75. 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickell KL, Leverenz JB, Steinbart EJ, Rumbaugh M, Schellenberg GD, Nochlin D, Lampe TH, Holm IE, Van Deerlin V, Yuan W, Bird TD. Clinicopathological concordance and discordance in three monozygotic twin pairs with familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1050–5. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.113803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ketelaar ME, Hofstra EM, Hayden MR. What monozygotic twins discordant for phenotype illustrate about mechanisms influencing genetic forms of neurodegeneration. Clin Genet. 2012;81:325–33. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiti S, Kumar KH, Castellani CA, O’Reilly R, Singh SM. Ontogenetic de novo copy number variations (CNVs) as a source of genetic individuality: studies on two families with MZD twins for schizophrenia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czyz W, Morahan JM, Ebers GC, Ramagopalan SV. Genetic, environmental and stochastic factors in monozygotic twin discordance with a focus on epigenetic differences. BMC Med. 2012;10:93. 10.1186/1741-7015-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris AW, Wang C, Yao J, Walsh SA, Sawatzke AB, Hu S, Sunderland JJ, Segar JL, Ponto LL. Effect of insulin and dexamethasone on fetal assimilation of maternal glucose. Endocrinology. 2011;152:255–62. 10.1210/en.2010-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mastroeni D, McKee A, Grover A, Rogers J, Coleman PD. Epigenetic differences in cortical neurons from a pair of monozygotic twins discordant for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6617. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruder CE, Piotrowski A, Gijsbers AA, Andersson R, Erickson S, Diaz de Stahl T, Menzel U, Sandgren J, von Tell D, Poplawski A, Crowley M, Crasto C, Partridge EC, Tiwari H, Allison DB, Komorowski J, van Ommen GJ, Boomsma DI, Pedersen NL, den Dunnen JT, Wirdefeldt K, Dumanski JP. Phenotypically concordant and discordant monozygotic twins display different DNA copy-number-variation profiles. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:763–771. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Notini AJ, Craig JM, White SJ. Copy number variation and mosaicism. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;123:270–7. 10.1159/000184717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–76. 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayrhofer M, DiLorenzo S, Isaksson A. Patchwork: allele-specific copy number analysis of whole-genome sequenced tumor tissue. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R24. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-3-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TM, Luquette LJ, Xi R, Park PJ. rSW-seq: algorithm for detection of copy number alterations in deep sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:432. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abyzov A, Urban AE, Snyder M, Gerstein M. CNVnator: an approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21:974–84. 10.1101/gr.114876.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, Larson DE, Kalicki JM, Pohl CS, McGrath SD, Wendl MC, Zhang Q, Locke DP, Shi X, Fulton RS, Ley TJ, Wilson RK, Ding L, Mardis ER. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods. 2009;6:677–81. 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moncunill V, Gonzalez S, Bea S, Andrieux LO, Salaverria I, Royo C, Martinez L, Puiggros M, Segura-Wang M, Stutz AM, Navarro A, Royo R, Gelpi JL, Gut IG, Lopez-Otin C, Orozco M, Korbel JO, Campo E, Puente XS, Torrents D. Comprehensive characterization of complex structural variations in cancer by directly comparing genome sequence reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1106–12. 10.1038/nbt.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rall K, Eisenbeis S, Barresi G, Ruckner D, Walter M, Poths S, Wallwiener D, Riess O, Bonin M, Brucker S. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome discordance in monozygotic twins: matrix metalloproteinase 14, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 10, extracellular matrix, and neoangiogenesis genes identified as candidate genes in a tissue-specific mosaicism. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:494–502e493. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brakta S, Hawkins ZA, Sahajpal N, Seman N, Kira D, Chorich LP, Kim HG, Xu H, Phillips JA 3rd, Kolhe R, Layman LC. Rare structural variants, aneuploidies, and mosaicism in individuals with Mullerian aplasia detected by optical genome mapping. Hum Genet. 2023;142:483–94. 10.1007/s00439-023-02522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biesecker LG, Spinner NB. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:307–20. 10.1038/nrg3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.