Abstract

Abstract

Ergothioneine (EGT) is a derivative of the amino acid L-histidine that is well known for its strong antioxidant properties. Recent studies on the functional characterization of EGT in both in vivo and in vitro systems have demonstrated its potential applications in pharmaceuticals, food, and cosmetics. The growing demand for EGT in novel applications necessitates the development of safe and cost-effective mass production technologies. Consequently, microbial fermentation for EGT biosynthesis has attracted significant attention. This review focuses on the biosynthesis of EGT via microbial fermentation, explores its biosynthetic mechanisms, and summarizes the latest advancements for industrial EGT production using engineered microbial strains.

Key points

• Ergothioneine (EGT) is an L-histidine derivative with strong antioxidant property.

• Recent studies have revealed certain groups of microbes produce EGT naturally.

• Superior EGT producers by genetic modification have been created.

Keywords: Ergothioneine, Antioxidant, Basidiomycetes, Biosynthesis

Introduction

Sulfur-containing biomolecules such as biotin, thiamine, and coenzyme A are essential to living organisms due to their critical roles in energy metabolism as cofactors in enzymatic reactions. Another sulfur-containing biomolecule, the tripeptide glutathione, is an antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage. In human cells, some sulfur-containing biomolecules are synthesized from sulfur-containing amino acids such as cysteine or methionine. However, others cannot be synthesized by the human body despite their essentiality, necessitating dietary intake. Deficiencies in these compounds often result in various diseases and symptoms (Smith et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2023). Consequently, medicines and dietary supplements comprising sulfur-containing biomolecules are widely distributed to aid in disease management and improve quality of life.

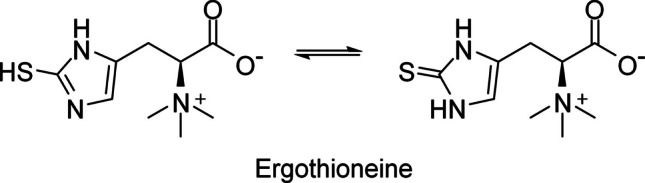

Ergothioneine (EGT) is a sulfur-containing biomolecule derived from L-histidine that was first identified in the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea (Tanret 1909). Its chemical structure involves a betaine configuration with a sulfur atom attached to the imidazole ring, and thiol and thione forms exist as a tautomer (Fig. 1). The thione form dominates at physiological pH (Servillo et al. 2015), making EGT stable in spite of the presence of the thiol group. EGT has since been detected in various human and animal cells and organs, including the liver, kidney, semen, and red blood cells (Cheah and Halliwell 2012; Borodina et al. 2020). Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of EGT (Colognato et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2012; Servillo et al. 2015; D'Onofrio et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2020), positioning it as a vitamin-like compound for humans (Paul and Snyder 2010). However, as plants and animals, including humans, cannot synthesize EGT, its presence in these organisms is believed to originate from microorganisms in natural or symbiotic environments. Mushrooms are recognized as the richest natural source of EGT (Kalaras et al. 2017), and mushroom extracts containing EGT are commercially available (Fu and Shen 2022).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of EGT. The tautomer forms of thiol (left) and thione (right) are shown

Recent studies have proposed novel applications for EGT in various industries such as foods, cosmetics, and agriculture. Encarnacion et al. (2011) demonstrated prevention of postharvest melanosis of shrimp by treating it with mushroom extracts containing EGT. Hseu et al. (2020) reported the protective effect of EGT on ultraviolet-induced damaged human dermal fibroblasts via controlling expression of genes concerning extracellular matrix-degradation and antioxidant. Hanayama et al. (2024) found skin moisturizing functions being improved by oral intake of EGT-containing mushroom products. Zhang et al. (2023b) reported preventing effect of EGT treatment on Brassica rapa clubroot development via elevating transcription levels of biosynthetic genes for phenolic compounds. Koshiyama et al. (2024) revealed that seed productivity of Arabidopsis thaliana increased by EGT via elevating transcript levels of FLOWERING LOCUS T. Sivakumar and Bozzo (2024) demonstrated preservative effect on postharvest arugula by EGT treatment. More recent studies suggested lifespan extending effect of EGT on Drosphila melanogaster (Pan et al. 2022, 2024). These advancements have significantly increased the demand for EGT. However, conventional manufacturing processes involving mushroom cultivation, fruiting body harvesting, and extraction are time-consuming and inefficient. Meeting the growing demand for EGT requires a safe, cost-effective process for its mass production.

This review focuses on the biosynthesis of EGT through microbial fermentation and its underlying biosynthetic mechanisms. Additionally, it summarizes recent technological advancements for the industrial production of EGT using engineered microbial strains.

EGT in microbial cells

The first identification of EGT in microbial cells was reported in the ergot fungus C. purpurea, a member of phylum Ascomycota (Tanret 1909). Subsequent studies have confirmed the presence of EGT in various bacteria and fungi, including mushrooms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microorganisms identified as native EGT producers

| Phylum | Class | Genus | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | ||||

| Ascomycota | Dothideomycetes | Alternaria | zinniae | Melville et al. (1956) |

| Eurotiomycetes | Aspergillus | carbonarius, fumigatus, nidulans, niger, oryzae, tenuis | Melville et al. (1956); Genghof (1970); Gallagher et al. (2012); Takusagawa et al. (2019) | |

| Penicillium | notatum, roqueforti | Genghof (1970) | ||

| Dipodascomycetes | Geotrichum | rugosum | Genghof (1970) | |

| Dothideomycetes | Aureobasidium | pullulans | Melville et al. (1956); Fujitani et al. (2018) | |

| Pezizomycetes | Morchella | esculenta a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | |

| Schizosaccharomycetes | Schizosaccharomyces | pombe | Pluskal et al. (2010) | |

| Sordariomycetes | Claviceps | purprea | Tanret (1909) | |

| Cordyceps | militaris a) | Chan et al. (2015) | ||

| Neurospora | crassa, tetrasperma | Genghof (1970) | ||

| Basidiomycota | Agaricomycetes | Agaricus | bisporus a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) |

| Agrocybe | aegerita a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Boletus | edulis a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Cantharellus | cibarius a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Flmmulina | velutipes a) | Bao et al. (2008) | ||

| Ganoderma | lucidum a), resinaceum a) | Kalaras et al. (2017); Yu et al. (2025) | ||

| Grifola | frondose a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Hericium | erinaceus a) | Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Lentinula | edodes a) | Tepwong et al. (2012); Kalaras et al. (2017) | ||

| Lyophyllum | connatum a) | Kimura et al. (2005) | ||

| Pleurotus | citrinpileatus a), cornucopiae a), eryngii a), ostreatus a) | Liang et al. (2013); Lin et al. (2015); Kalaras et al. (2017); Fujitani et al. (2018) | ||

| Panus | conchatus a) | Zhu et al. (2022) | ||

| Microbotryomycetes | Rhodotorula | glutinis, mucilaginosa | Fujitani et al. (2018) | |

| Sporobolomyces | salmonicolor | Genghof (1970) | ||

| Ustilaginomycetes | Anthracocystis | flocculosa | Sato et al. (2024) | |

| Dirkmeia | churashimaensis | Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Kalmanozyma | fusiformata | Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Moesziomyces | antarcticus, parantarcticus, rugulosus | Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Pseudozyma | alboarmeniaca, graminicola, hubeiensis, prolifica, tsukubaensis | Fujitani et al. (2018); Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Triodiomyces | crassus | Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Ustilago | maydis, shanxiensis, siamensis | Sato et al. (2024) | ||

| Mucoromycota | Mucoromycetes | Mucor | mucedo | Melville et al. (1956) |

| Rhizopus | stolonifer | Genghof (1970) | ||

| Bacteria | ||||

| Actinomycetota | Actinomycetes | Actinoplanes | philippinensis | Genghof (1970) |

| Mycobacterium | avium, bovis, fortuitum, intracellularis, kansasii, leprae, marinum, microti, neoaurum, paratubeculosis, phlei, piscium, rhodochrous, smegmatis, thamnopheos, tubeculosis, ulcerans | Genghof and van Damme (1964); Xiong et al. (2022) | ||

| Nocardia | asteroides | Genghof (1970) | ||

| Streptomyces | albus, coelicolor, fradiae, griseus | Genghof (1970); Nakajima et al. (2015) | ||

| Cyanobacteriota | Cyanophyceae | Oscillatoria | sp. | Pfeiffer et al. (2011) |

| Scytonema | sp. | Pfeiffer et al. (2011) | ||

| Pseudomonadota | α-Proteobacteria | Methylobacterium | aquaticum | Alamgir et al. (2015) |

| Rhodothermota | Rhodothermia | Salinibacter | ruber | Burn et al. (2017) |

a)Mushrooms

Currently, mushrooms are the most well-known natural producers of EGT. Phylum Ascomycota includes non-edible fungi, such as Cordyceps militaris (class Sordariomycetes), a medicinal fungus known for producing cordycepin, which also contains EGT in its fruiting bodies (Chan et al. 2015). The yellow morel Morchella esculenta (class Pezizomycetes) has also been identified as an EGT producer (Kalaras et al. 2017). Phylum Basidiomycota includes widely consumed edible mushrooms capable of producing EGT, such as Agaricus bisporus (white mushroom), Boletus edulis (porcini), and Pleurotus citrinopileatus (golden oyster mushroom), all belonging to class Agaricomycetes. Additionally, medicinal mushrooms, including Ganoderma lucidum and Panus conchatus, are known as EGT producers (Kalaras et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2022). However, large-scale production of EGT through mushroom cultivation is inefficient due to the extended time required for fruiting body maturation (several weeks or months depending on the species) and the relatively low EGT content (0.15–7.27 mg/g dry mushrooms) in these organisms (Dubost et al. 2007; Pfeiffer et al. 2011; Kalaras et al. 2017). Therefore, extensive research has been conducted to identify microbial sources that can facilitate fermentative EGT production.

Among fungi other than mushrooms, several members of Ascomycota have been reported to produce EGT, including Neurospora crassa (class Sordariomycetes), Aspergillus fumigatus and Penicillium notatum (class Eurotiomycetes), and Aureobasidium pullulans (class Dothideomycetes) (Melville et al. 1956; Genghof 1970; Fujitani et al. 2018). In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (class Schizosaccharomycetes), the genetic and biochemical pathways for EGT biosynthesis have been extensively investigated (Pluskal et al. 2010, 2014). Many EGT-producing fungi belong to phylum Basidiomycota, and yeast species within this phylum have also been identified as EGT producers, such as strains of Rhodotorula and Sporobolomyces (class Microbotryomycetes) (Genghof 1970; Fujitani et al. 2018). Recent studies have identified diverse EGT-producing yeast strains within class Ustilaginomycetes (Sato et al. 2024), a group also known for glycolipid production (Morita et al. 2015). Phylum Mucoromycota includes EGT-producing genera such as Mucor and Rhizopus (Melville et al. 1956; Genghof 1970). However, some yeast strains within Ascomycota, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia membranifaciens, Candida albicans, and Torulopsis utilis, have been reported to lack EGT production (Genghof 1970; Fujitani et al. 2018).

In bacteria, multiple strains of Mycobacterium (phylum Actinomycetota) have been identified as EGT producers. Other actinomycetes capable of EGT synthesis include Actinoplanes philippinensis and Nocardia asteroides (Genghof 1970). Certain Streptomyces strains, including Streptomyces albus and Streptomyces griseus, which are known for antibiotic production, also synthesize EGT (Genghof 1970). Other bacterial taxa, including cyanobacteria and Methylobacterium, have been identified as EGT producers (Pfeiffer et al. 2011; Alamgir et al. 2015). More recently, Salinibacter ruber, an extremely halophilic bacterium within phylum Rhodothermota, was demonstrated to produce EGT (Burn et al. 2017). The gene involving EGT biosynthesis under anaerobic conditions was found in this bacterium. Despite these findings, few EGT-producing bacterial species have been identified compared to fungi. Furthermore, several bacterial species have been reported to lack EGT production, including Corynebacterium xerosis and Micrococcus pyogenes var. aureus (phylum Actinomycetota); Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium perfringens, and Lactobacillus casei (phylum Bacillota); and Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Vibrio metchnikovii (phylum Pseudomonadota) (Melville et al. 1956).

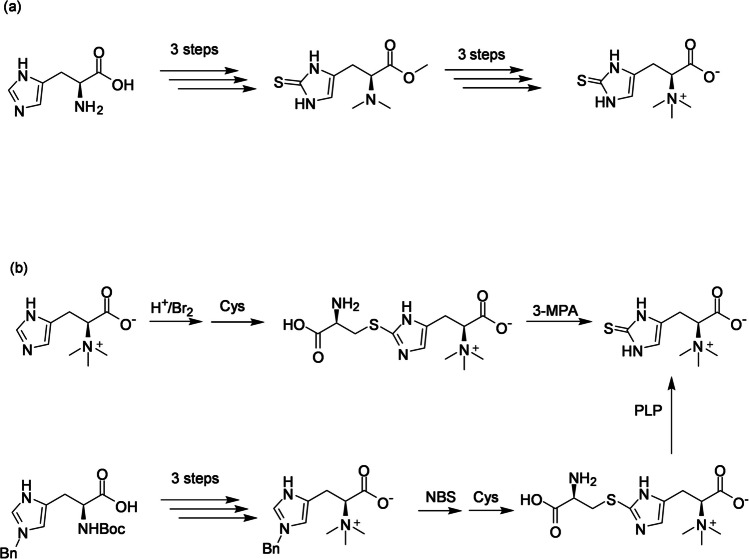

EGT synthetic reactions

EGT can be synthesized from L-histidine and its derivatives through enzymatic reactions both in vivo and in vitro, as well as through chemical reactions. Although the chemical structure of EGT is relatively simple (Fig. 1), its chemical synthesis is complicated by the need for protection and deprotection of carboxyl and amino groups when introducing a sulfur atom at the C- 2 position of the imidazole ring. These reactions require harsh conditions, involve harmful chemicals, and result in low yields. Xu and Yadan (1995) reported the synthesis of EGT from L-histidine via an Nα,Nα-dimethyl imidazole- 2-thione derivative in six steps, with an overall yield of 34% (Scheme 1a). The key sulfur introduction reaction was achieved using phenyl chlorothionoformate as the sulfur donor. Recent studies have developed sulfur-introducing reactions that mimic biological processes in microbial cells for EGT synthesis under milder conditions with fewer reaction steps. Using hercynine as a starting material, EGT can be synthesized in a single-pot reaction via hercynylcysteine sulfide as an intermediate (Erdelmeier et al. 2012; Scheme 1b). Hercynylcysteine sulfide can also be synthesized from an L-histidine derivative with an N-benzyl-protected imidazole in good yield, followed by a non-enzymatic reaction with pyridoxal phosphate to yield EGT (Khonde and Jardine 2015; Scheme 1b).

Scheme 1.

Cys, L-cysteine; 3-MPA, 3-mercaptopropionic acid; NBS, N-bromosuccinimide; PLP, pyridoxal phosphate

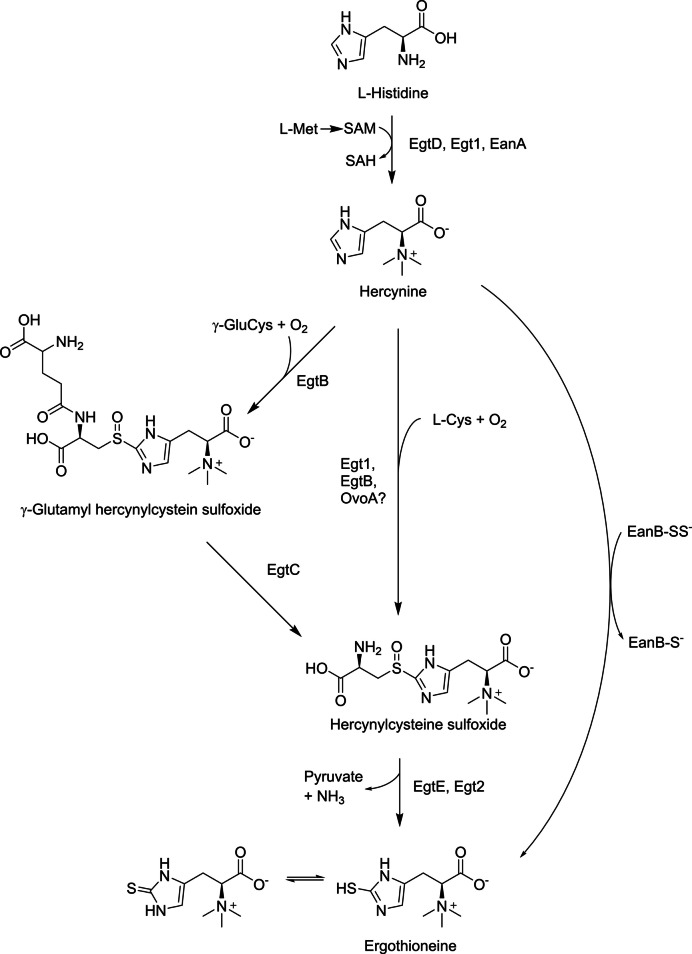

The synthesis of EGT in microbial cells is relatively simple and efficient. The synthetic routes in microbial cells have been investigated, and the catalytic enzymes involved have been identified. In EGT-producing bacteria such as Mycobacterium smegmatis, EGT is synthesized from L-histidine via four enzymatic reactions (Fig. 2, left). Nα-trimethylation of L-histidine with three molecules of S-adenosylmethionine is catalyzed by EgtD, followed by sulfur introduction into the imidazole ring, catalyzed by EgtB, using γ-glutamylcysteine as a sulfur donor. EgtC catalyzes the cleavage of glutamic acid, followed by C-S cleavage to produce ergothioneine with EgtE. In addition to these four enzymes, EgtA, which catalyzes the formation of γ-glutamylcysteine from glutamic acid and cysteine, has been identified. These five enzyme-encoding genes form a cluster for EGT biosynthesis.

Fig. 2.

Biosynthetic pathways for EGT production in Mycobacterium smegmatis (left), Neurospora crassa (center), and Chlorobium limicola (right). Met, L-methionine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; Cys, L-cysteine; γ-GluCys, γ-glutamylcysteine

In EGT-producing fungi, including N. crassa, EGT is synthesized via three enzymatic reactions, which is more efficient than the bacterial pathway (Fig. 2, center). First, L-histidine is converted to hercynine by Egt1 using SAM. The same protein, with an additional enzymatic activity, then catalyzes the introduction of cysteine at the C- 2 position of the imidazole ring in hercynine, forming cysteinyl hercynylsulfoxide. This step differs from the bacterial pathway, which uses γ-glutamylcysteine. The subsequent reaction forming EGT is catalyzed by Egt2. As for Flammulina velutipes, an edible mushroom known as the EGT producer (see Table 1), three genes encoding enzymes for EGT biosynthesis were identified and in vitro formation of EGT using the three enzymes (FvEgt1, 2, and 3) was demonstrated (Yang et al. 2020). In the reaction, formation of cysteine hercynylsulfoxide from L-histidine is catalyzed by FvEgt1, as the same as that in other fungi, while liberation of EGT from cysteinyl hercynylsulfoxide is catalyzed by FvEgt2 and FvEgt3 simultaneously. Another mushroom Grifola frondosa was found to possess EGT biosynthetic genes egt1 and egt2, both of which only required EGT biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae (Yu et al. 2020).

EgtB, the key enzyme in EGT biosynthetic reactions, has been categorized into five types based on structural perspectives (Stampfli et al. 2019). Type II EgtB from Chloracidbacterium thermophilum exhibited catalytic activity toward cysteine rather than γ-glutamylcysteine in in vitro enzymatic characterization. Some EgtBs from Methylobacterium strains, classified as type II, have also been demonstrated to produce EGT by heterologous expression of egtB genes in E. coli without EgtC activity (Kamide et al. 2020).

Recently, additional biosynthetic routes have been discovered. The strictly anaerobic photosynthetic green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium limicola possesses EanA and EanB enzymes, which catalyze the anaerobic biosynthesis of EGT from histidine (Burn et al. 2017). In the EanB-catalyzing reaction, sulfur is introduced into the imidazole ring of hercynine without sulfur donor molecules such as cysteine, occurring in an oxygen-independent manner that differs from other EGT biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 2, right). The sulfur donor in this reaction is EanB itself with the catalytic cysteine persulfide anion (EanB-SS− in Fig. 2), which attacks the imidazole ring of hercynine directly (Leisinger et al. 2019). Genes with high sequence identity to eanA and eanB have been discovered in other bacteria and archaea, including S. ruber and Methanohalophilus mahii (Burn et al. 2017). In cyanobacteria, sulfoxide synthase activity involved in EGT biosynthesis may be provided by OvoA, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of ovothiol A, another thiol-containing L-histidine derivative (Liao and Seebeck 2017). These discoveries provided insight into the biological functions of EGT in EGT-producing microbes, as well as alternative tools for synthetic biology to create superior EGT producers.

Fermentative production of EGT by native EGT producers

Identified native EGT producers have been investigated for their fermentative production of EGT, as summarized in Table 2. In fungi, early studies reported EGT production at levels below 1 mg/g dry cells, including species such as Aspergillus niger, N. crassa, and P. notatum (Melville et al. 1956). More recent studies on novel EGT producers have demonstrated fermentative production with productivity exceeding 1 mg/g dry cells or 10 mg/L culture medium. Fujitani et al. (2018) investigated A. pullulans and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa for EGT production and, after optimizing culture conditions, achieved fermentative production levels of 14 and 24 mg/L, respectively.

Table 2.

Biosynthesis of EGT by native EGT-producing microbes

| Organisms | Culture media | Scales | Titer | Specific yield | Productivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/L culture) | (mg/g dry cell) | (mg/L/day) | ||||

| Fungi | ||||||

| Aspergillus niger ATCC1027 | Czapek’s solution | Flask | - | 0.22 | - | Melville et al. (1956) |

| Aspergillus oryzae NSAR1 | Steeped rice solid medium | 11.5 (mg/kg-media) | - | 2.3 | Takusagawa et al. (2019) | |

| Alternaria zinniae ATCC11786 | Czapek’s solution | Flask | - | 0.02 | - | Melville et al. (1956) |

| Aureobasidium pullulans kz25 | SD medium, 2% glycerol + 2% yeast extract | Test tube | 14 | 1 | 2 | Fujitani et al. (2018) |

| Mucor mucedo ATCCC9836 | Czapek’s solution | Flask | - | 0.29 | - | Melville et al. (1956) |

| Neurospora crassa ATCC10337 | Ryan | Flask | - | 0.86 | - | Melville et al. (1956) |

|

Panus conchatus (mycelia) |

Optimized fermentation medium, 5% molasses, 3% soypeptone | Flask | 81.44 | 8.4 | 20.4 | Zhu et al. (2022) |

| Optimized fermentation medium, 5% molasses, 3% soypeptone, 0.04% cysteine | Flask | 148.79 | 9.1 | 24.8 | Zhu et al. (2022) | |

| Penicillium notatum ATCC8537 | Wickerham medium | Flask | - | 0.13 | - | Melville et al. (1956) |

|

Pleurotus citrinopileatus (mycelia) |

Basal medium, 2% glucose | 18.2 | 2.9 | 0.83 | Lin et al. (2015) | |

| Basal medium, 2% glucose + amino acids | 98 | 12.3 | 6.1 | Lin et al. (2015) | ||

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa z41c | SD medium, 2% glycerol + 2% yeast extract | Test tube | 24 | 3.2 | 3.4 | Fujitani et al. (2018) |

| Shizossacharomyces pombe WT 972 | EMM2 medium, nitrogen starvation | - | 157.4 (μM, intracellular) | - | Pluskal et al. (2014) | |

| Tridiomyces crassus CBS9959 | YM medium (flask) | Flask | 30.9 ± 1.8 | 5.7 | 6.2 | Sato et al. (2024) |

| Ustilago shanxiensis CBS10075 | YM medium, 0.1% methionine (flask) | Flask | 34.7 ± 3.9 | 8.4 | 6.9 | Sato et al. (2024) |

| Ustilago siamensis CBS9960 | YM medium (flask) | Flask | 49.5 ± 7.0 | 9.3 | 9.9 | Sato et al. (2024) |

| YM medium (jar) | 5L-Jar | 54.0 ± 15.0 | 11.7 | 10.8 | Sato et al. (2024) | |

| YM medium, 0.1% histidine (flask) | Flask | 74.9 ± 5.5 | 13.9 | 15 | Sato et al. (2024) | |

| Bacteria | ||||||

| Methylobacterium aquaticum 22 A | MM medium, 2% methanol | Flask | 12.2 | 2 | 1.7 | Fujitani et al. (2018) |

| Mycolicibacterium neoaurum ATCC25795 | Chemically defined medium containing 1.6% glycerol, 0.4% glucose, 0.2% citric acid | Flask | 13.3 | - | 2.66 | Xiong et al. (2022) |

| Nocardia asteroids | Wickerham medium, 1% mannitol + 0.4% asparagine | - | 0.52 | - | Genghof (1970) | |

| Oscillatoria sp. CCAC M1944 | Waris-H medium | Flask | - | 0.8–0.9 | - | Pfeiffer et al. (2011) |

| Streptomyces griseus ATCC10317 | Romano and Nickerson medium | - | 0.5 | - | Genghof (1970) |

Among the Basidiomycota, diverse yeast strains belonging to basidiomycetes have been identified as EGT producers (Sato et al. 2024). Ustilago siamensis produces EGT at 49.5 mg/L in yeast malt medium and 74.9 mg/L in yeast malt medium supplemented with histidine. The intracellular EGT content in U. siamensis reached 13.9 mg/g dry cells, representing the highest productivity among native EGT producers. This strain was also capable of EGT production in a jar fermenter, indicating its potential for large-scale production.

Additionally, submerged mycelial cultivation of mushrooms has been demonstrated to efficiently produce EGT. After optimizing culture conditions, EGT production in the golden oyster mushroom P. citrinopileatus improved to 98 mg/L under mycelium cultivation (Lin et al. 2015). Another mushroom, P. conchatus, was also cultivated for EGT production, achieving 149 mg/L within 6 days (Zhu et al. 2022), corresponding to a high productivity rate of 24.8 mg/L/day. These findings suggest the potential for large-scale EGT production through mycelial culture of EGT-producing mushrooms.

In addition to fungal sources, bacterial strains of native EGT producers have been studied for their EGT production. Strains of cyanobacterial genera including Scytonema and Oscillatoria produced intracellular EGT at levels of up to 0.8 mg/g dry cells, which was higher than the levels found in king oyster mushrooms (Pfeiffer et al. 2011). An investigation of EGT production in Methylobacterium aquaticum 22 A revealed EGT accumulation of 12.2 mg/L (Fujitani et al. 2018). Mycolicibacterium neoaurum produced EGT at 13.3 mg/L in a chemically defined medium containing glycerol, glucose, and citric acid as carbon sources (Xiong et al. 2022).

Genetically modified microorganisms for EGT production

Following the identification of EGT biosynthetic genes in M. smegmatis (Seebeck 2010), N. crassa (Bello et al. 2012), S. pombe (Pluskal et al. 2014), and F. velutipes (Yang et al. 2020), EGT-producing microbes have been created using genetic engineering technology, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Biosynthesis of EGT in genetically modified microbes

| Organisms | Strain | Parental strain | Genes modified a) | Conditions | Titer | Specific yield | Productivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/L culture) | (mg/g dry cell) | (mg/L/day) | ||||||

| Fungi | ||||||||

| Aspergilus oryzae | NS-Nc12 | NSAR1 | egt1 and egt2 from Neurospora crassa | Solid media, 120 h | 231.0 ± 1.1 mg/kg of media | - | 46.2 mg/kg/day | Takusagawa et al. (2019) |

| Cordyceps militaris | 15-E1bD2 | CM15 | egtD from Mycobacterium smegmatis, truncated egt1 and egt2 | Flask, 240 h | - | 2.49 ± 0.05 | - | Chen et al. (2022) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ST8927 | CEN.PK113 - 7D | egt1 from Neurospora crassa and egt2 from Claviceps purpurea; 2 copies | 1-L jar, fed-batch, 84 h | 598 ± 18 | - | 171 | van der Hoek et al. (2019) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ST10165 | ST8927 (egt1 and egt2 inserted strain of CEN.PK113 - 7D) | His-overproducing mutant, met14, Δspe2 | 1-L jar, fed-batch, 160 h | 2390 ± 80 | - | 359 | van der Hoek et al. (2022a) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | BY4741egtA | BY4741 | egtA from Aspergillus fumigastus | Flask, 96 h | 7.93 | - | - | Doyle et al. (2022) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | IMX582-Egt1&2-STL1 | IMX581 | egt1 from Ganoderma resinaceum and egt2 from Neurospora crassa, STL1-overproducing | 5-L jar, fed-batch, 240 h | 1140 | - | 114 | Yu et al. (2024) |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 972 | P3nmt-egt1+ | egt1 from S. pombe | Synthetic minimal medium (EMM2) | - | 1.6 mM | - | Pluskal et al. (2014) |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | ST10264 | ST6512 | egt1 from Neurospora crassa and egt2 from Claviceps purpurea; 2 copies | 1-L jar, fed-batch, 220 h | 1637 ± 41 | - | 178 | van der Hoek et al. (2022b) |

| Bacteria | ||||||||

| Crynebacterium glutamicum | ET11 | ATCC13032 | egt1 and egt2 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, cysEKR from C. glutamicum, promoter replacement by H36 synthetic promoter for enhancing sulfur assimilation, pentose phosphate pathway and cysteine synthesis, ΔsdaA | Jar, fed-batch, 36 h | 264.4 | - | 176 | Kim et al. (2022) |

| Crynebacterium glutamicum | CYS- 2/pECt-Mb_egtB-Ms_egtDE | CYS- 2 (cystein-overproducing strain) | egtB from Methylobacterium brachiatum, egtDE from Mycolicibacterium smegmatis | Flask, fed-batch, 120 h | 100 | - | 20 | Hirasawa et al. (2023) |

| Escherichia coli | ET3 | BW25113 (high L-cysteine producing strain) | egtBCDE from Mycobacterium smegmatis | Flask, 72 h | 24 ± 4 | - | 8 | Osawa et al. (2018) |

| Escherichia coli | CHΔmetJ pQE1a-egtABCDE | JW3909 (metJ-deleted strain of BW25113) | egtABCDE from Mycobacterium smegmatis, ΔmetJ | 3-L jar, fed-batch, 216 h | 1310 | - | 146 | Tanaka et al. (2019) |

| Escherichia coli | BW-tregt1-tregt2 | BW25113 | egt1 and egt2 from Trichoderma reesei | 2-L jar, fed-batch, precursors supplemented, 143 h | 4340 | - | 728 | Chen et al. (2022) |

| Escherichia coli | MD4 | BL21(DE3) | truncated, mutated egt1 from Neurospora crassa, mutated egtD from Mycrobacterium smegmatis | Jar, fed-batch, precursors supplemented, 96 h | 5400 | - | 1351 | Zhang et al. (2023a) |

| Escherichia coli | ECE14 | BL21(DE3) | egtBDE from Methylobacterium aquaticum, serAmut, thrAmut, ΔmetJ,ΔsdaA, | 10-L jar, fed-batch, 72 h | 595 | - | 197 | Zhang et al. (2024) |

| Methylobacterium aquaticum | 22 AΔhutH(EGT) | 22 A | egtBD, ΔhutH | Test tube, 168 h | 20 | 7 | 2.9 | Fujitani et al. (2018) |

| Mycolicibacterium neoaurum | EGT24E | ATCC25795 | egtABCDE, hisG, hisC, allB1, deletion of putative EGTase gene (MnΔ3042) | 5-L jar, fed-batch, precursorus supplemented, 216 h | 1560 ± 270 | - | 173 | Xiong et al. (2022) |

a)Abbreviations: egtA, glutamine-cysteine ligase gene; egtB, hercynine oxygenase gene; egtC, glutamine amidotransamidase gene; egtD, S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase gene; egtE, pyridoxal 5-phosphate-dependent b-lyase gene; egt1, bifunctional enzyme gene of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase and hercynine-cysteine sulfoxidase; egt2, pyridoxal 5-phosphate-dependent b-lyase gene; metJ, transcriptional repressor gene for methionine biosynthetic genes; met14, ATP: adenylylsulfate- 3′-phosphotransferase gene; spe2, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene; hutH, histidine-ammonia lyase gene; hisG, ATP-phosphoribosyltransferase gene; hisC, histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase gene; allB1, allantoinase 1 gene; sdaA, serine deaminase gene; cysE, serine acetyltransferase gene; cysK, O-acetyl L-serine sulfhydrylase; cysR, transcriptional regulator gene for sulfur assimilation

In fungi, non-EGT producers, such as S. cerevisiae and Yarrowia lipolytica, have been engineered to enable EGT production by heterologous expression of EGT biosynthetic genes from N. crassa and C. purpurea. By tuning the metabolic balance in precursor supply through gene manipulation and cultivation conditions, S. cerevisiae ST10165 and Y. lipolytica ST10264, both of which harbor two copies of egt1 from N. crassa and two copies of egt2 from C. purpurea, produced EGT at 2390 ± 80 and 1637 ± 41 mg/L from glucose after 160 and 220 h of fed-batch cultivation, respectively, using synthetic media without supplementation of precursor amino acids (van der Hoek et al. 2022a, 2022b). The strain S. cerevisiae ST10165 was genetically modified in L-histidine biosynthesis by mutagenesis with β-(1,2,4-triazol- 3-yl)-DL-alanine, SAM metabolism by spe2 deletion, and L-cysteine fluxes by overexpression of met14, suggesting that enhancement of Egt1-catalyzing reaction (Fig. 2, center) could improve EGT productivity. In contrast, the strain Y. lipolytica ST10264 had no genetic modification for amino acid metabolisms and the cells were cultivated under phosphate-limited conditions, suggesting sufficient pools of precursor amino acids available for EGT biosynthesis in Y. lipolytica. Another strain of S. cerevisiae, harboring egt1 from Ganoderma resinaceum and egt2 from N. crassa for EGT synthesis and overexpressing SLT1 for enhanced glycerol assimilation, produced EGT at 1.14 g/L from glycerol after 240 h of fed-batch cultivation using semisynthetic medium containing 10 g/L yeast extract and 20 g/L peptone as the starting medium (Yu et al. 2024). Interestingly, recombinant S. cerevisiae with egtA, which encodes methyltransferase and sulfoxide synthase from A. fumigatus, produced a small amount of EGT at 7.93 mg/L in flask cultivation (Doyle et al. 2022). Because no EGT biosynthetic genes are found in S. cerevisiae, the reaction catalyzed by Egt2 or EgtE, which involves C-S bond cleavage to form EGT, may have occurred due to inherent activity in S. cerevisiae or as an abiotic reaction.

Among bacterial hosts, Escherichia coli, a non-EGT producer, has been primarily used to confer EGT-producing ability through genetic engineering. Using egtA, egtB, egtC, egtD, and egtE from M. smegmatis, an E. coli cysteine-hyperproducing mutant acquired the ability to produce EGT. By modifying precursor supplies, E. coli strain CHΔmetJ pQE1a-egtABCDE produced EGT at 1.3 g/L in 216 h of fed-batch cultivation with supplementation of L-histidine, L-methionine, and sodium thiosulfate after induction of expression of introduced genes (Tanaka et al. 2019). Deletion of metJ, the transcriptional repressor for L-methionine and SAM biosynthesis, in this strain could enhance SAM supply to EGT biosynthesis by elevating transcriptional level of metK that encodes methionine adenosyltransferase. Additionally, E. coli strains harboring egt1 and egt2 from the fungus Trichoderma reesei achieved EGT production of 4.34 g/L in 143 h of fed-batch cultivation with constant supplementation of the mixture of precursor amino acids L-histidine, L-methionine, and L-cysteine (40 g/L each) after induction of expression of egt1 and egt2 (Chen et al. 2022). Another E. coli strain harboring truncated and mutated egt1 from N. crassa, mutated egtD, and wild-type egtE from M. smegmatis produced EGT at 5.4 g/L in 96 h of fed-batch culture (Zhang et al. 2023a). Constant feeding at 11 mL/h of precursor amino acids L-histidine, L-methionine, and L-cysteine (24 g/L each) was conducted after induction of introduced genes. A reconstructed pathway using EGT biosynthetic genes from M. aquaticum, omitting the EgtA- and EgtC-catalyzing reactions, enabled E. coli to produce EGT (Zhang et al. 2024). By deleting metJ and sdaA and overexpressing mutant genes of serA and thrA, which could enhance SAM and L-cysteine fluxes, the strain ECE14 produced EGT at 595 mg/L in 72 h of fed-batch cultivation. Superior EGT-producing E. coli with heterologous egtB, egtD, and egtE from N. crassa as well as manipulation of inherent biosynthetic genes for precursor amino acids was demonstrated to improve metabolic fluxes toward EGT biosynthesis in the Patent CN116121161, achieving EGT production of 7.1 g/L in 60 h of fed-batch cultivation (Wu et al. 2022). These studies suggest that not only enhancing EGT biosynthetic reactions (Fig. 2) but also modulating precursor amino acids supplies could elevate EGT production. Thus, E. coli strains carrying heterologous EGT biosynthetic genes are promising candidates for industrial EGT bioproduction.

Corynebacterium glutamicum, an actinomycete with superior amino acid bioproduction ability, has also been modified to produce EGT. By enhancing cysteine biosynthesis and introducing egtB from Methylobacterium brachiatum and egtD and egtE from M. smegmatis, C. glutamicum strains CYS- 2/pECt-Mb_egtB-Ms_egtDE produced EGT at 100 mg/L in 120 h of fed-batch cultivation in flasks using a semisynthetic medium containing 10 g/L yeast extract as a starting medium (Hirasawa et al. 2023). Another study employing egt1 and egt2 from S. pombe and balancing cysteine assimilation showed that C. glutamicum ET11 improved EGT yields to 264.4 mg/L in 36 h of fed-batch cultivation with starting and feeding media containing yeast extract (Kim et al. 2022).

Native EGT-producing microorganisms such as S. pombe (Pluskal et al. 2014), Aspergillus oryzae (Takusagawa et al. 2019), M. aquaticum (Fujitani et al. 2018), M. neoaurum (Xiong et al. 2022), and C. militaris (Chen et al. 2022) have demonstrated enhanced EGT biosynthetic ability through EGT biosynthetic gene upregulation and the improvement of precursor amino acid metabolic fluxes. Among them, Mycolicibacterium neoaurum strain EGT24E with overexpression of inherent EGT biosynthetic genes (egtABCDE) and L-histidine biosynthetic genes (hisG and hisC) as well as deletion of putative EGT-degrading enzyme (EGTase) gene produced EGT at 1.56 ± 0.27 g/L in 216 h of fed-batch cultivation with constant supplementation of the mixture of L-histidine (15 g/L), L-methionine (30 g/L), ammonium sulfate (8 g/L), and sodium thiosulfate (8 g/L) between 48 and 120 h of cultivation. Deletion of the gene encoding putative EGTase in the strain EGT24E repressed a decrease of EGT titer during fed-batch fermentation, implying the necessity of the regulation in degradation as well as synthesis for further enhancement of EGT bioproduction. A recent patent document (CN116445302) described multiple-round mutagenesis by ultraviolet irradiation and/or lithium chloride treatment with a native EGT producer S. pombe to improve EGT productivity (> 10 g/L of EGT production), although genomic mutations in the strain were not analyzed and no mechanistic evidence to account for such EGT productivity was presented in the document (Zhou et al. 2022). These suggest superior potential of native EGT producers for the production of EGT by genetic modification. Also, some EGT-producing strains, such as Aspergillus and Pseudozyma strains, are already utilized in industrial processes in the food and chemical industries. Although fundamental improvement in EGT biosynthesis by genetic and bioprocess engineering should be necessary, the native EGT producers reviewed here could have a great potential as host strains for industrial EGT production due to the presence of inherent biosynthetic enzymes and related metabolic processes.

Unlike model microorganisms such as E. coli and S. cerevisiae, natural EGT-producing strains lack well-established genetic engineering tools. However, among the Basidiomycetes, genetic tools have been developed for strain engineering in Ustilago (Olicón-Hernández et al. 2019) and Pseudozyma (Saika et al. 2017), leading to the creation of superior strains for enhanced glycolipid-type biosurfactant production. With these technologies, recombinant Ustilago and related strains may provide powerful tools for enhanced EGT production. Some Pseudozyma strains have already been utilized in industrial processes for production of biosurfactants (Saika et al. 2019), and process technologies for large-scale fermentation of these strains have been developed. Further improvements in productivity, as well as the development of fermentation and downstream processes, will be essential for the mass production of EGT through microbial fermentation.

Conclusion and future perspectives

This review highlights recent progress in the microbial synthesis of EGT, along with biosynthetic pathways that may be leveraged to create novel EGT producers through synthetic biology. A wide variety of bacteria and fungi produce EGT, and significant advances have been made in elucidating its biosynthetic mechanisms. By employing these findings, useful recombinant strains for EGT production were created and multiple examples of fermentative EGT production at gram scale using the strains have been presented. Further investigation of EGT-producing microorganisms will require elucidation of the unknown physiological roles of EGT in native producers to gain a deeper understanding of its synthesis and catabolism. Additionally, the exploration of novel EGT producers may expand the available genetic tools and host strains for synthetic biology applications. By integrating these mechanistic insights into EGT biosynthesis with process engineering strategies, microbial production processes can advance to the next stage, enabling the large-scale production of EGT to meet increasing industrial demand.

Author contribution

SS and TM conceived and designed research and edited this manuscript. SS performed literature search and data analysis and wrote the original draft. SS, AS, TK, YH, TF, and TM critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alamgir KM, Masuda S, Fujitani Y, Fukuda F, Tani A (2015) Production of ergothioneine by Methylobacterium species. Front Microbiol 6:4025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao HND, Ushio H, Ohshima T (2008) Antioxidative activity and antidiscoloration efficacy of ergothioneine in mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) extract added to beef and fish meats. J Agric Food Chem 56:10032–10040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello MH, Barrera-Perez V, Morin D, Epstein L (2012) The Neurospora crassa mutant NcDEgt-1 identifies an ergothioneine biosynthetic gene and demonstrates that ergothioneine enhances conidial survival and protects against peroxide toxicity during conidial germination. Fungal Genet Biol 49:160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodina I, Kenny LC, McCarthy CM, Paramasivan K, Pretorius E, Roberts TJ, van der Hoek SA, Kell DB (2020) The biology of ergothioneine, an antioxidant nutraceutical. Nutr Res Rev 33:190–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burn R, Misson L, Meury M, Seebeck FP (2017) Anaerobic origin of ergothioneine. Angew Chem Int Ed 56:12508–12511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LSL, Barseghyan GS, Asatiani MD, Wasser SP (2015) Chemical composition and medicinal value of fruiting bodies and submerged cultured mycelia of caterpillar medicinal fungus Cordyceps militaris CBS-132098 (Ascomycetes). Int J Med Mushrooms 17:649–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah IK, Halliwell B (2012) Ergothioneine; antioxidant potential, physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822:784–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B-X, Xue L-N, Wei T, Ye Z-W, Li X-H, Guo L-Q, Lin J-F (2022) Enhancement of ergothioneine production by discovering and regulating its metabolic pathway in Cordyceps militaris. Microb Cell Fact 21:169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato R, Laurenza I, Fontana I, Coppede F, Siciliano G, Coecke S, Aruoma OI, Benzi L, Migliore L (2006) Modulation of hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage, MAPLs activation and cell death in PC12 by ergothioneine. Clinic Nut 25:135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio N, Servillo L, Giovane A, Casale R, Vitiello M, Marfella R, Paolisso G, Balestrieri ML (2016) Ergothioneine oxidation in the protection against high-glucose induced endothelial senescence: involvement of SIRT1 and SIRT6. Free Rad Biol Med 96:211–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S, Cuskelly DD, Conlon N, Fitzpatrick DA, Gilmartin CB, Dix SH, Jones GW (2022) A single Aspergillus fumigatus gene enables ergothioneine biosynthesis and secretion by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int J Mol Sci 23:10832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubost NJ, Ou B, Beelman RB (2007) Quantification of polyphenols and ergothioneine in cultivated mushrooms and correlation to total antioxidant capacity. Food Chem 105:727–735 [Google Scholar]

- Encarnacion AB, Fagutao F, Hirayama J, Terayama M, Hirono I, Ohshima T (2011) Edible mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) extract inhibits melanosis in Kuruma Shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). J Food Sci 76:C52–C58 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Erdelmeier I, Daunay S, Lebel R, Farescour L, Yadan JC (2012) Cysteine as a sustainable sulfur reagent for the protecting-group-free synthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids: biomimetic synthesis of l-ergothioneine in water. Green Chem 14:2256–2265 [Google Scholar]

- Fu TT, Shen L (2022) Ergothioneine as a natural antioxidant against oxidative stress-related diseases. Front Pharmacol 13:850813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitani Y, Almagir KM, Tani A (2018) Ergothioneine production using Methylobacterium species, yeast, and fungi. J Biosci Bioeng 126:715–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher L, Owens RA, Dolan SK, O’Keeffe G, Schrettl M, Kavanagh K, Jones GW, Doyle S (2012) The Aspergillus fumigatus protein GliK protects against oxidative stress and is essential for gliotoxin biosynthesis. Eukaryot Cell 11:1226–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genghof DS (1970) Biosynthesis of ergothioneine and hercynine by fungi and Actinomycetales. J Bacteriol 103:475–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genghof DS, van Damme O (1964) Biosynthesis of ergothioneine and hercynine by mycobacteria. J Bacteriol 87:852–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hanayama M, Mori K, IshimotoT Kato Y, Kawai J (2024) Effects of an ergothioneine-rich Pleurotus sp. on skin moisturizing functions and facial conditions: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Front Med 11:1396783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Shimoyamada Y, Tachikawa Y, Satoh Y, Kawano Y, Dairi T, Ohtsu I (2023) Ergothioneine production by Corynebacterium glutamicum harboring heterologous biosynthesis pathways. J Biosci Bioeng 135:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hseu Y-C, Gowrisankar YV, Chen X-Z, Yang Y-C, Yang H-L (2020) The antiaging activity of ergothioneine in UVA-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts via the inhibition of the AP-1 pathway and the activation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant genes. Ocid Med Cell Longev 2020:2576823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaras MD, Richie JP, Calcagnotto A, Beelman R (2017) Mushrooms: a rich source of the antioxidants ergothioneine and glutathione. Food Chem 233:429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamide T, Takusagawa S, Tanaka N, Ogasawara Y, Kawano Y, Ohtsu I, Satoh Y, Dairi T (2020) High production of ergothioneine in E. coli using the sulfoxide synthase from Methylobacterium strains. J Agric Food Chem 68:6390–6394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khonde PL, Jardine A (2015) Improved synthesis of the super antioxidant, ergothioneine, and its biosynthetic pathway intermediates. Org Biomol Chem 13:1415–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Jeong DW, Oh JW, Jeong HJ, Ko YJ, Park SE, Han SO (2022) Efficient synthesis of food-derived antioxidant l-ergothioneine by engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Agric Food Chem 70:1516–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura C, Nukina M, Igarashi K, Sugawara Y (2005) β-Hydroxyergothioneine, a new ergothioneine derivative from the mushroom Lyophyllum connatum, and its protective activity against carbon tetrachloride-induced injury in primary culture hepatocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 69:357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiyama T, Higashiyama Y, Mochizuki I, Yamada T, Kanekatsu M (2024) Ergothioneine improves seed yield and flower number through FLOWERING LOCUS T gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants (Basel) 13:2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisinger F, Burn R, Meury M, Lukat P, Seebeck FP (2019) Structural and mechanistic basis for anaerobic ergothioneine biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 141:6906–6914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C-H, Huang L-Y, Ho K-J, Lin S-Y, Mau J-L (2013) Submerged cultivation of mycelium with high ergothioneine content from the culinary-medicinal king oyster mushroom Pleurotus eryngii (higher basidiomycetes) and its composition. Int J Med Mushr 15:153–164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liao C, Seebeck FP (2017) Convergent evolution of ergothioneine biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. ChemBioChem 18:2115–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S-Y, Chien S-C, Wang S-Y, Mau J-L (2015) Submerged cultivation of mycelium with high ergothioneine content from the culinary-medicinal golden oyster mushroom, Pleurotus citrinopileatus (higher basidiomycetes). Int J Medic Mushr 17:749–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville DB, Genghof DS, Inamine E, Kovalenko V (1956) Ergothioneine in microorganisms. J Biol Chem 223:9–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita T, Fukuoka T, Imura T, Kitamoto D (2015) Mannosylerythritol lipids: production and applications. J Oleo Sci 64:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S, Satoh Y, Yanashima K, Matsui T, Dairi T (2015) Ergothioneine protects Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) from oxidative stresses. J Biosci Bioeng 120:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olicón-Hernández D, Araiza-Villanueva M, Pardo JP, Aranda E, Guerra-Sánchez G (2019) New insights of Ustilago maydis as yeast model for genetic and biotechnological research: a review. Curr Microbiol 76:917–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa R, Kamide T, Satoh Y, Kawano Y, Ohtsu I, Dairi T (2018) Heterologous and high production of ergothioneine in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem 66:1191–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H-Y, Ye Z-W, Zheng Q-W, Yun F, Tu M-Z, Hong W-G, Chen B-X, Guo L-Q, Lin J-F (2022) Ergothioneine exhibits longevity-extension effect in Drosophila melanogaster via regulation of cholinergic neurotransmission, tyrosine metabolism, and fatty acid oxidation. Food Funct 13:227–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Zheng Q, Zou Y, Luo G, Tu M, Wang N, Zhong J, Guo L, Lin J (2024) Geroprotection from ergothioneine treatment in Drosophila melanogaster by improving intestinal barrier and activation of intestinal autophagy. Food Sci Human Well 13:3434–3446 [Google Scholar]

- Paul B, Snyder S (2010) The unusual amino acid l-ergothioneine is a physiologic cytoprotectant. Cell Death Differ 17:1134–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer C, Bauer T, Surek B, Schomig E, Grundemann D (2011) Cyanobacteria produce high levels of ergothioneine. Food Chem 129:1766–1769 [Google Scholar]

- Pluskal T, Nakamura T, Villar-Briones A, Yanagida M (2010) Metabolic profiling of the fission yeast S. pombe: quantification of compounds under different temperatures and genetic perturbation. Mol Biosyst 6:182–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluskal T, Ueno M, Yanagida M (2014) Genetic and metabolomic dissection of the ergothioneine and selenoneine biosynthetic pathway in the fission yeast, S. pombe, and construction of an overproduction system. PLOS One 9:e97774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika A, Koike H, Yamamoto S, Kishimoto T, Morita T (2017) Enhanced production of a diastereomer type of mannosylerythritol lipid-B by the basidiomycetous yeast Pseudozyma tsukubaensis expressing lipase genes from Pseudozyma antarctica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:8345–8352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika A, Koike H, Fukuoka T, Morita T (2019) Tailor-made mannosylerythritol lipids: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:6877–6884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Saika A, Ushimaru K, Koshiyama T, Higashiyama Y, Fukuoka T, Morita T (2024) Biosynthetic ability of diverse basidiomycetous yeast strains to produce the natural antioxidant ergothioneine. AMB Express 14:20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebeck FP (2010) In vitro reconstitution of mycobacterial ergothioneine biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 132:6632–6633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servillo L, Castaldo D, Casale R, D’Onofrio N, Giovane A, Cautela D, Balestrieri ML (2015) An uncommon redox behavior shed light on the cellular antioxidant properties of ergothioneine. Free Rad Biol Med 79:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar D, Bozzo G (2024) Exogenous ergothioneine and glutathione limit postharvest senescence of arugula. Antioxidants 13:1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Ottosson F, Hellstrand S, Ericson U, Orho-Melander M, Fernandez C, Melander O (2020) Ergothioneine is associated with reduced mortality and decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart 106:691–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Johnson CR, Koshy R, Hess SY, Qureshi UA, Mynak ML, Fischer PR (2021) Thiamine deficiency disorders: a clinical perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1498:9–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfli AR, Goncharenko KV, Meury M, Dubey BN, Schirmer T, Seebeck FP (2019) An alternative active site architecture for O2 activation in the ergothioneine biosynthetic EgtB from Chloracidobacterium thermophilum. J Am Chem Soc 141:5275–5285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takusagawa S, Satoh Y, Ohtsu I, Dairi T (2019) Ergothioneine production with Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 83:181–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Kawano Y, Satoh Y, Dairi T, Ohtsu I (2019) Gram-scale fermentative production of ergothioneine drive by overproduction of cysteine in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 9:1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanret C (1909) A new base taken from rye ergot, ergothioneine. Ann Chim Phys 18:114–124 [Google Scholar]

- Tepwong P, Giri A, Ohshima T (2012) Effect of mycelial morphology on ergothioneine production during liquid fermentation of Lentinula edodes. Mycoscience 53:102–112

- van der Hoek SA, Darbani B, Zugaj KE, Prabhala BK, Biron MB, Randelovic M, Medina JB, Kell DB, Borodina I (2019) Engineering the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of l-(+)-ergothioneine. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 7:262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek SA, Rusnak M, Wang G, Stanchev LD, Alves LF, Jessop-Fabre MM, Paramasivan K, Jacobsen IH, Sonnenschein N, Martinez JL, Darbani B, Kell DB, Borodina I (2022a) Engineering precursor supply for the high-level production of ergothioneine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng 70:129–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek SA, Rusnak M, Jacobsen IH, Martinez JL, Kell DB, Borodina I (2022b) Engineering ergothioneine production in Yarrowia lipolytica. FEBS Lett 596:1356–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Liu W, Xie X, Jiang S, Ma Q, Shuai Z (2022) Genetically engineered bacterium for producing ergothioneine, and construction method and application thereof. Chinese patent CN116121161

- Xiong L-B, Xie Z-Y, Ke J, Li, Wang L, Gao B, Tao X-Y, Zhao M, Shen Y-L, Wei D-Z, Wang F-Q (2022) Engineering Mycolicibacterium neoaurum for the production of antioxidant ergothioneine. Food Bioeng 1:26–36

- Xu J, Yadan JC (1995) Synthesis of l-(+)-ergothioneine. J Org Chem 60:6296–6301 [Google Scholar]

- Yang N-C, Lin H-C, Wu J-H, Ou H-C, Chai Y-C, Tseng C-Y, Liao J-W, Song T-Y (2012) Ergothioneine protects against neuronal injury induced by β-amyloid in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 50:3902–3911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Lin S, Lin J, Wang Y, Lin J-F, Guo L-Q (2020) Biosynthetic pathway of ergothioneine in culinary–medicinal winter mushroom, Flammulina velutipes (Agaricomycetes). Int J Med Mushrooms 22:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JC, Jacobs JP, Hwang M, Sabui S, Liang F, Said HM, Skupsky J (2023) Biotin deficiency induces intestinal dysbiosis associated with an inflammatory bowel disease-like phenotype. Nutrients 15:264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y-H, Pan H-Y, Guo L-Q, Lin J-F, Liao H-L, Li H-Y (2020) Successful biosynthesis of natural antioxidant ergothioneine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae required only two genes from Grifola frondosa. Microb Cell Fact 19:164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y-H, Liu H-Q, Zhang S, Su Z-R, Guo L, Lin J-F (2024) Highly efficient production of ergothioneine from glycerol through gene mining and CRISPR-Cas9 synthetic biology technology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 12:15901–15912 [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y-H, Ye Z-W, Huang Y-M, Wang N, Zheng Q-W, Zhong J-R, Chen B-X, Lin J-F, Guo L-Q (2025) Optimization of fermentation conditions in ergothioneine biosynthesis from Ganoderma resinaceum (Agaricomycetes) and an evaluation of their inhibitory activity on xanthine oxidase. Int J Med Mushrooms 27:71–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Tang J, Feng M, Chen S (2023a) Engineering methyltransferase and sulfoxide synthase for high-yield production of ergothioneine. J Agric Food Chem 71:671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cao G, Li X, Piao Z (2023b) Effects of exogenous ergothioneine on Brassica rapa clubroot development revealed by transcriptomic analysis. Int J Mol Sci 24:6380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhang Y, Zhao M, Zabed HM, Qi X (2024) Fermentative production of ergothioneine by exploring novel biosynthetic pathway and remodulating precursor synthesis pathways. J Agric Food Chem 72:14264–14273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Xiang T, Yang M, Peng W, Xing C, Liu G (2022) Yeast and application thereof in preparation of ergothioneine. Chinese patent CN116445302

- Zhu M, Han Y, Hu X, Gong C, Ren L (2022) Ergothioneine production by submerged fermentation of a medicinal mushroom Panus conchatus. Fermentation 8:431 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.