Summary

Background

Minor head trauma is a frequent cause of emergency department visits, early identification and prediction of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) patients with abnormal brain lesions are vital for minimizing unnecessary computed tomography (CT) scans, reducing radiation exposure, and ensuring timely effective treatment and care. This study aims to develop and validate an interpretable machine learning (ML) prediction model using routine laboratory data for guiding clinical decisions on CT scan use in mTBI patients.

Methods

We conducted a multicentre study in China including data from January 2019 to July 2024. Our study included three patient cohorts: a retrospective training cohort (654 patients for training and 163 for internal testing) and two prospective validation cohorts (86 internal and 290 external patients). Fifty-one routine clinical laboratory characteristics, readily available from the electronic medical record (EMR) system within the first 24 h of admission, were collected. Seven ML algorithms were trained to develop predictive models, with the random forest (RF) algorithm used to optimize key feature combinations. Model predictive performance was evaluated using metrics such as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), positive predictive value (PPV), and F1 scores. The SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) was applied to interpret the final model, while decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess the clinical net benefit.

Findings

In the derivation cohort, 599 (73.3%) patients had normal CT scans and 218 (26.7%) had abnormal CT scans. The Gradient boosting classifier (GBC) model performed best among the seven ML models, with an AUC of 0.932 (95% CI: 0.900–0.963). After reducing features to 21 (8 biochemical test indicators, 3 coagulation markers, and 10 complete blood cell count indicators) according to feature importance rank, an explainable GBC-final model was established. The final model accurately predicted mTBI patients with abnormal CT in both internal (AUC 0.926, 95% CI: 0.893–0.958) and external (AUC 0.904, 95% CI: 0.835–0.973) validation cohorts. In the prospective cohort, final GBC model achieved AUC of 0.885 (95% CI: 0.753–1.000) and was significantly superior to traditional TBI biomarkers GFAP (AUC: 0.745) and PGP9.5 (AUC: 0.794). DCA revealed that the final model offered greater net benefits than “full intervention” or “no intervention” strategies within a probability threshold range of 0.16–0.93. SHAP analysis identified D-dimer levels, absolute lymphocyte and neutrophil counts, and hematocrit as key high-risk features.

Interpretation

Our optimal feature selection-based ML model accurately and reliably predicts CT abnormalities in mTBI patients using routine test data. By addressing clinicians' concerns regarding transparency and decision-making through SHAP and DCA analyses, we strengthen the potential clinical applicability of our ML model.

Funding

The Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, high-level Talent Research Startup Funding of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan Health and Family Planning Scientific Research Fund Project of Hubei Province, and Machine Learning-based Intelligent Diagnosis System for AFP-negative Liver Cancer Project.

Keywords: Mild traumatic brain injury, CT abnormal, Machine learning, Prediction model, SHAP, DCA

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Head computed tomography (CT) scans are a common diagnostic tool for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). While several clinical decision rules and biomarkers exist to identify mild TBI (mTBI) patients who require CT examinations, the overutilization of head CT for low-risk mTBI individuals remains a significant clinical issue, offering limited benefit while exposing patients to unnecessary radiation risks and economic burdens. We searched PubMed for articles published up to November 18, 2024, using the search terms “(mTBI or mild traumatic brain injury) and (prediction model) and (CT or computed tomography)” without language restrictions. Although several machine learning (ML) prediction models for predicting CT abnormalities in mTBI patients have been reported, these studies often suffer from limitations such as overly subjective variable selection and a lack of interpretability due to the opaque “black box” nature of the models.

Added value of this study

In this study, we developed an interpretable prediction model for CT abnormalities in a multicenter cohort of patients with mTBI using a 21-feature based gradient boosting classifier (GBC) algorithm. The final model demonstrated strong performance in both internal and external validation, provided greater net benefits compared to “full intervention” or “no intervention” strategies, and outperformed traditional TBI serum biomarkers and statistical prediction models constructed with the same test feature parameters in prospective application. SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) analysis identified key features driving the model's predictions, including D-dimer levels, absolute lymphocyte and neutrophil counts, and hematocrit values at or above the threshold.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study is the first prospective, multicenter investigation to compare seven ML models for predicting radiological abnormalities in a TBI cohort. Our final interpretable GBC model, developed using automated Random Forest (RF)-based feature selection, demonstrated strong sensitivity, accuracy, and generalizability in identifying CT abnormalities in mTBI patients. The model utilized 21 routine laboratory variables, readily available within the first 24 h of hospital admission via the laboratory information system (LIS). It was interpreted using the SHAP method, offering both global insights into the model's overall functionality and local explanations of individual predictions based on personalized input data. These findings highlight the clinical potential and value of our final model.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects over 50 million people annually and is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide,1,2 with an estimated global economic burden of $400 billion.3 Based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), TBI is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, with mild TBI (mTBI) accounting for nearly 90% of cases.3 However, the delayed onset and latent symptoms of mTBI patients often result in underdiagnosis and underreporting, earning it the designation of a “silent epidemic”. Computed tomography (CT) scan is the standard imaging tool for detecting life-threatening intracranial injuries in TBI, such as hemorrhages or skull fractures. However, only 5.2–9.4% of mTBI patients have intracranial lesions, and just 0.2–3.5% require surgical intervention.4 Therefore, accurately identifying mTBI patients who need CT scans is essential for improving triage and resource allocation.

Currently, various diagnostic tools have been developed to assist clinicians in determining which mTBI patients require a head CT scan, including the Canadian Computed Tomography Head Rule (CCHR), the New Orleans Criteria (NOC), the CHIP Prediction Rule, and the NEXUS II criteria.5 While these methods are highly sensitive in detecting intracranial lesions, their specificity remains limited, and clinicians have inconsistent assessments of their clinical outcomes.5,6 Emerging research suggests that neurogenic biomarkers such as S100B, neurofilament light chain (NFL), and Tau in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid can aid in identifying CT abnormalities, with the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) recently approving glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) as auxiliary tools for intracranial injury evaluation.7 However, biomarker tests often require expensive, large-scale equipment, suffer from variability in diverse methods. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more advanced, convenient, and cost-effective strategies to accurately identify TBI patients who genuinely require CT imaging.

The rapid progress of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in machine learning (ML), has notably advanced the use of vast electronic medical records (EMR) for early disease detection, differential diagnosis, and prognosis prediction. These ML models, exceling in analyzing multi-label, multi-modal clinical data, automatically extracting key features, and performing complex correlation analyses, improve the efficiency and accuracy of diagnostic processes, attracting significant interest from the medical community.8 Specifically, in the field of TBI, ML has been effective in predicting CT scan abnormalities across different demographics, including children,9, 10, 11, 12 elderly patients13 and those on anticoagulants.14 However, the inherent opacity of these algorithmic models has limited their widespread adoption in clinical settings, as clinicians struggle to trust them without clear, medically validated decision rules.

To enhance the interpretability of ML models, the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) method, introduced in 2017 and based on game theory, clarifies how each feature influences model predictions.15 By addressing the “black-box” nature of end-to-end algorithms, SHAP increases trust in ML-driven predictions. However, integrating ML into routine clinical practice remains challenging due to uncertainties about its impact on patient outcomes, often referred to as the “AI Chasm”.16 To bridge this gap, decision curve analysis (DCA) provides data-driven support for ML models. Commonly used to assess clinical utility, DCA balances the benefits and risks of interventions at varying risk thresholds, aiding clinical decision-making and optimizing patient care.17

Routine laboratory indicators, a key component of EMR system, are increasingly valuable for training ML models in various diseases. For example, the ML model using only laboratory data can be used to diagnose and evaluate the prognosis of COVID-19 patients.18 Pan et al. used conventional laboratory data to construct a ML model for the differential diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy.19 However, ML models specifically leveraging routine test data for intracranial lesions after TBI remain limited. Previous research20, 21, 22 has linked increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) progression in TBI patients to abnormal coagulation tests, while elevated white blood cell counts and the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII)—which integrates neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets—have been strongly associated with poor TBI outcomes. Yet, these studies primarily rely on statistical analyses, often overlooking complex interrelationships between features, thereby limiting their clinical applicability. We hypothesize that, with advanced ML methods, an optimized combination of routine laboratory parameters can provide sufficient information to identify patients with CT abnormalities.

This study aims to develop and validate an interpretable ML model using routine clinical laboratory data to predict CT abnormalities in emergency department mTBI patients. We constructed and evaluated various ML algorithm models on a retrospective TBI dataset, optimized feature combinations, and assessed the stability and diagnostic performance of these models in external and prospective cohorts, from which the best performer was selected as our final prediction model. Subsequently, the accuracy of the final model in identifying TBI-CT abnormalities was compared with traditional TBI serum biomarkers and binary regression statistical models for a comprehensive methodological evaluation. Feature importance was analyzed visually using SHAP values for model interpretation, and the clinical utility of the model was assessed through DCA based on the principle of net benefit.

Methods

Study population

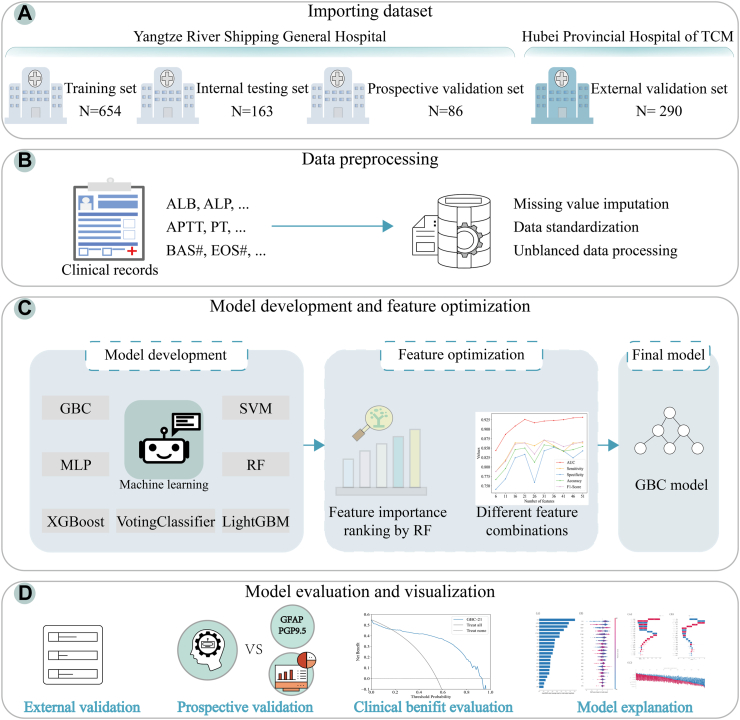

Our study included three patient cohorts: a retrospective training cohort and two prospective validation cohorts (internal and external). Retrospective data from Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital, collected between January 2019 and March 2023, were used to train and test the model. The trained model was then prospectively validated at Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital (March 2023–January 2024) and externally validated at Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) (July 2023–July 2024). Diagnostic and treatment procedures for mTBI were consistent across both hospitals. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of our Hospital (Approval No. YL2003033). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. The overall framework of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The overall framework of the study. (A) Importing dataset. (B) Data preprocessing. (C) Model development and feature optimization. (D) Model evaluation and visualization. TCM: traditional chinese medicine; ALB: albumin; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; PT: prothrombin time; BAS#: basophil count; EOS#: eosinophil count; GBC: gradient boosting classifier; LightGBM: light gradient boosting machine; MLP: multi-layer perceptron; SVM: support vector machine; XGBoost: extreme gradient boosting; RF: random forest; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; PGP9.5: protein gene product 9.5.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with mTBI who were admitted to the emergency department within 24 h after head trauma; (2) patients received head CT scans within 24 h of admission. (3) age >18 years old. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous history of neurological and psychiatric diseases (epilepsy, meningitis, hemorrhage, stroke); (2) pregnant women; (3) patients with acute infectious diseases; (4) patients with acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease; (5) patients with malignant tumors; (6) spinal fracture; (7) data loss due to consultation, transfer, or any other medical reason. mTBI patients are identified according to International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code 850 or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code S06.0.

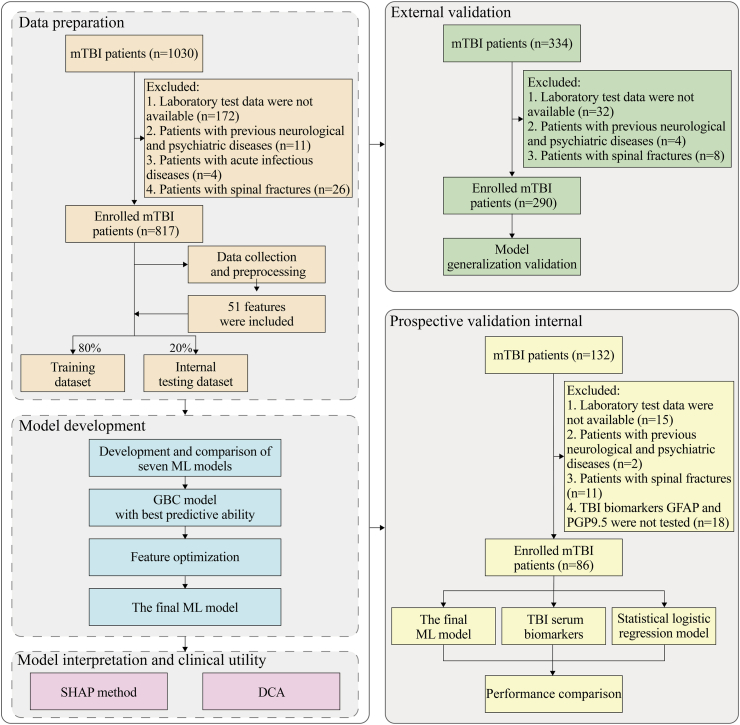

All patients' CT head scan findings were reviewed and classified as either normal or abnormal by experienced imaging experts. All head CT scans were independently reviewed by two imaging experts with 10 years of experience, and disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a senior expert. Specifically, we assessed for subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, subdural hematoma, intraventricular hemorrhage, and/or punctate hemorrhage, as these abnormalities have been associated with worsening neurological status and poor prognosis in the literature.23,24 The study design is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the study design. mTBI: mild traumatic brain injury; ML: machine learning; GBC: gradient boosting classifier; SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanation; DCA: decision curve analysis; TBI: traumatic brain injury; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; PGP9.5: protein gene product 9.5.

Data collection

We collected laboratory test data and demographic characteristics of mTBI patients from the hospital's medical record information. During the collection process, features with over 70% missing values were excluded in the following analyses to minimize the bias caused by missing data.

Finally, 51 features were utilized to develop the prediction models, including 28 biochemical test indicators: albumin (ALB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), calcium (Ca), cholinesterase (CHE), cholesterol (CHOL), chlorine (Cl), carbon dioxide (CO2), creatinine (CRE), cystatin C (Cys-C), direct bilirubin (DBIL), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), globulin (GLB), glucose (GLU), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), indirect bilirubin (IBIL), potassium (K), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), phosphorus (P), total bile acids (TBA), total bilirubin (TBIL), triglyceride (TG), total protein (TP), uric acid (UA); 6 coagulation indicators: activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), D-Dimer (D-D), fibrinogen (FIB), prothrombin time (PT), prothrombin time international normalized ratio (PT-INR), thrombin time (TT); 17 complete blood cell count indicators: basophil count (BAS#), eosinophil count (EOS#), hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin (HGB), lymphocyte count (LYM#), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), monocytes count (MON#), mean platelet volume (MPV), neutrophil count (NEU#), plateletcrit (PCT), platelet distribution width (PDW), platelet-large cell rate (P-LCR), platelet (PLT), red blood cell (RBC), red cell distribution width coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), red cell distribution width-standard deviation (RDW-SD), white blood cell (WBC). The proportions of missing data per variable are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Data processing

Missing value imputation

Missing data in medical datasets can lead to biased or inaccurate results in data analysis and ML models. We conducted a comparison of model performance using various imputation methods such as K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) imputation, median imputation and multiple imputation for missing values (Supplementary Table S2). The principle of KNN imputation is to identify K data points that are spatially similar or close in the data set through distance measurement, and then use the average of their values to fill in the missing values until generating a complete data set to ensure the integrity of the data. Median imputation replaces missing values by using the median of a feature. Multiple imputation establishes the interpolation function through the known values, estimates the values to be interpolated, and then adds different deviations to the values to form multiple sets of optional interpolation values, and generates multiple complete data sets to be evaluated. The results of the best performance after applying KNN imputation, therefore KNN filling method was used to fill in the missing data in the dataset. Among them, the Grid search method is used to determine that the KNN filling result is optimal when K = 5.

Data standardization

StandardScaler which scales the data to a standard normal distribution with the mean value of 0 and the standard deviation of 1 was used to normalize the filled data to ensure the consistency of scale between different features, so as to avoid the bias caused by dimensional differences between features and improve the stability of the data and the accuracy of model training.

Unbalanced data processing

To address the challenge of unbalanced data between the abnormal CT group and the normal CT group in the training set, we applied Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE)25 using KNN to synthesize new data from a minority class until the desired minority sample size is generated. This approach improves the generalization ability and accuracy of the model and reduces the overfitting of the model.

Model development and comparison

The retrospectively collected TBI cohort data were randomly split into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%). The training set was used for model development, while the test set was reserved for internal validation. Seven ML algorithms—gradient boosting classifier (GBC), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), multilayer perceptron (MLP), support vector machine (SVM), voting classifier, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and random forest (RF)—were used to build predictive models using the training data, and these models were internally validated on the test data. Five-fold and ten-fold cross-validation were conducted on the internal validation cohort to prevent model overfitting. The accuracy and generalization ability of the final prediction model were further validated using an independent external dataset. Additionally, the final ML model was tested in a prospective cohort and compared with conventional TBI biomarkers and logistic regression models.

In this work, we are particularly interested in the GBC algorithm as it achieves the best discriminative performances. GBC, which acts as an integrated classifier, reduces errors by resampling and changing the weight of a single weak learners to improve classification accuracy. GBC predicts the probability that sample is 1 is and trains the model by exploiting the log-likelihood loss as the loss function, where is the true label.

The details are as follows:

Optimal feature selection

Feature importance was ranked using RF algorithm, which calculates feature importance based on the Gini index. The Gini index measures the concentration and dependence of the features, helping to determine their significance in model predictions. The Gini index for node i in tree t is calculated as follows:

Where , it is expressed as the number of categories contained in the dataset, and is the proportion of samples belonging to the class in the node of the tree. For each feature , its importance of node in the decision tree is the amount of Gini index change before and after the branch of node , where and are the Gini index of the two new index nodes and split from node , respectively.

If nodes with feature have in the decision tree, then the importance of feature in the decision tree is:

If RF has decision tree, then the importance score of feature is calculated as follows:

Finally, the normalized importance scores are obtained for feature importance ranking.

To optimize feature selection, the number of features was iteratively reduced in increments of 5 (from 51 to 6), based on their importance. The predictive performance of different feature combinations was evaluated during this process.

Model evaluation indexes

To assess the diagnostic performance of the models, we used several metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and F1 score. The F1 score represents the harmonic mean of recall and precision. The formula for each evaluation metric is provided below.

TP: True Positive; TN: True Negative; FP: False Positive; FN: False Negative.

The clinical utility of the final ML model was quantitatively assessed using DCA.26 The net benefit of the model was compared against two default strategies: full-intervention and none-intervention. A model demonstrating a consistently higher net benefit across a broad range of threshold probabilities indicates superior clinical applicability.

TPR: True positive rate; FPR: False positive rate; Pt: the probability at the decision threshold, meaning the predicted probability of a certain outcome at which a clinician would decide to take appropriate action (administer a treatment, perform an invasive diagnostic test, etc.).

Model explanation

SHAP is an interpretable analysis method for ML models, grounded in cooperative game theory. Its core idea is to decompose the model's output into the contribution value of each feature.15 In this study, for each input sample, all possible feature combinations were considered to form a comprehensive feature space. The marginal contribution of each feature was then calculated across different combinations, representing the change in model output when a feature was added. The average marginal contribution, weighted by the number of possible feature combinations and their corresponding probabilities, was used to calculate each feature's Shapley value. This value explains whether the feature acts as a protective or risk factor in the model's prediction.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were used IBM SPSS (version 26.0), R (version 4.2.3), and Python (version 3.10.0). Categorical data were represented as frequencies and percentages [n (%)], and comparisons between groups were made using Chi-square test and Fisher test. The normality of continuous data was analyzed by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk normality tests. Quantitative data with a normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation (x ± s) and independent samples t-test was used for comparison between the two groups. Non-normally distributed continuous data were presented using median with interquartile range (IQR), and rank sum tests were used to compare groups. The bilateral test value of p < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Patient characteristics

The retrospective dataset used for model training and internal validation included data from 817 patients with mTBI, of which 599 (73.3%) had normal CT scans and 218 (26.7%) had abnormal CT scans. For the external validation cohort, 198 patients (68.3%) had normal CT scans and 92 (31.7%) had abnormal CT scans. For the prospective validation cohort, 69 patients (80.2%) had normal scans and 17 (19.8%) had abnormal scans. The baseline characteristics of the retrospective cohort, prospective validation cohorts (internal and external), including age, gender, and data on CT scan outcomes and 51 laboratory test items, are listed in Supplementary Tables S3–S5, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

KNN sensitivity experiment: In KNN, the choice of K values is crucial for the final prediction results, so we performed a hyperparametric sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Figure S1A). It can be clearly that K = 5 produced the best performance metrics (AUC = 0.932, Sensitivity = 0.864, Specificity = 0.843, PPV = 0.870, NPV = 0.835, Accuracy = 0.854, and F1 score = 0.867).

Oversampling sensitivity experiment: To assess the model sensitivity to the imbalanced training dataset input, different k_neighbors value were considered using SMOTE oversampling (Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Figure S1B). The value of k_neighbors = 5 was considered more superior, produced promising results (AUC = 0.932, Sensitivity = 0.864, Specificity = 0.843, PPV = 0.870, NPV = 0.835, Accuracy = 0.854, and F1 score = 0.867).

Model development

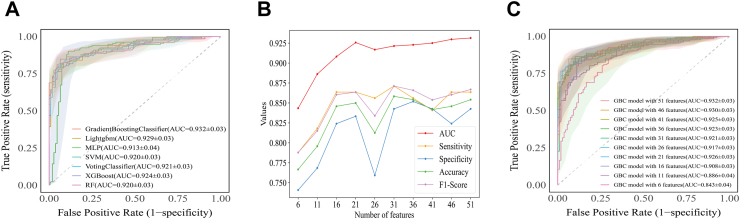

Based on the 51 routine test features, we conducted sensitivity test on KNN imputation and SMOTE oversampling respectively. We found that K = 5 and k_neighbors = 5 was optimal for the model. Then, we used all 51 routine test features to train the seven ML algorithms and compared their diagnostic performance, as shown in Table 1. Among the models, GBC achieved the highest AUC (0.932, 95% CI: 0.900–0.963), along with optimal sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy, and F1 score. The MLP model had the lowest AUC values (Fig. 3A).

Table 1.

Performance of the seven ML models.

| Models | AUC | SE | SP | PPV | NPV | AC | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBC | 0.932 ± 0.03 | 0.864 | 0.843 | 0.870 | 0.835 | 0.854 | 0.867 |

| LightGBM | 0.929 ± 0.03 | 0.864 | 0.806 | 0.844 | 0.829 | 0.838 | 0.854 |

| MLP | 0.913 ± 0.04 | 0.924 | 0.796 | 0.847 | 0.896 | 0.867 | 0.884 |

| SVM | 0.920 ± 0.03 | 0.864 | 0.815 | 0.851 | 0.830 | 0.842 | 0.857 |

| Votingclassifier | 0.921 ± 0.03 | 0.856 | 0.852 | 0.876 | 0.829 | 0.854 | 0.866 |

| XGBoost | 0.924 ± 0.03 | 0.864 | 0.843 | 0.870 | 0.835 | 0.854 | 0.867 |

| RF | 0.920 ± 0.03 | 0.849 | 0.852 | 0.875 | 0.821 | 0.850 | 0.862 |

ML: machine learning; AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; SE: sensitivity; SP: specificity; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; AC: accuracy; F1: F1 score; GBC: gradient boosting classifier; LightGBM: light gradient boosting machine; MLP: Multi-Layer Perceptron; SVM: support vector machine; XGBoost: eXtreme gradient boosting; RF: random forest.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of the seven ML algorithms based on the ROC curve. (A) ROC curves of the diagnostic models generated by seven ML algorithms. (B) AUC, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1 score of GBC model with different feature combinations. (C) ROC curves of GBC model with different feature combinations. ML: machine learning; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; AUC: the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; GBC: gradient boosting classifier; Lightgbm: light gradient boosting machine; MLP: Multi-Layer Perceptron; SVM: support vector machine; XGBoost: eXtreme gradient boosting; RF: random forest.

Feature optimization

We then optimized the GBC model (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S8). As shown in Fig. 3C and Supplementary Figure S2, when using 21 features, the GBC model's AUC (0.926, 95% CI: 0.893–0.958) and average precision (AP = 0.95) remained comparable to the original full-feature model. These 21 features included 8 biochemical test indicators, 3 coagulation markers, and 10 complete blood cell count indicators (Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, this GBC model with 21 features was selected as the final model. The model implements specific parameters set in Supplementary Table S9.

To prevent overfitting, five-fold and ten-fold cross-validation were performed on the final GBC model, with the results visualized in Supplementary Figure S4.

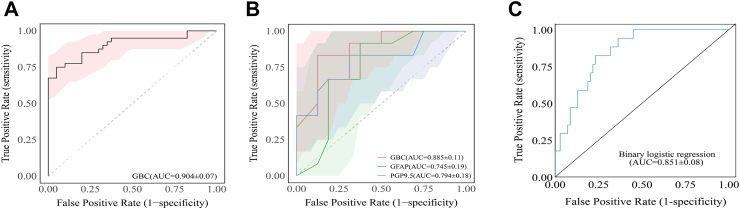

Comparison and validation of the final ML model

We evaluated the final model's performance in the prospective cohorts. As shown in Fig. 4A, the GBC model achieved an AUC of 0.904 (95% CI: 0.835–0.973) in the external cohort of Hubei Province Hospital of TCM demonstrating strong generalization and robustness across diverse sample distributions and data attributes.

Fig. 4.

Comparison and validation of the final ML model based on the ROC curve in prospective cohorts. (A) Performance of the final ML model based on the ROC curve in the prospective validation cohort at Hubei Provincial Hospital of TCM. (B) Comparison of the final GBC model and two TBI serum biomarkers based on the ROC curve in the prospective validation cohort at Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital. (C) Performance of the binary logistic regression model based on 21 features in the prospective validation cohort at Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital. ML: machine learning; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; TCM: Traditional Chinese Medicine; GBC: gradient boosting classifier; TBI: traumatic brain injury; AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; PGP9.5: protein gene product 9.5.

Moreover, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of the GBC model against classic TBI markers and statistical models in the prospective cohort at Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital, as shown in Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S10. The GBC model (AUC = 0.885) significantly outperformed the serum GFAP (AUC = 0.745, 95% CI: 0.552–0.937) and PGP9.5 (AUC = 0.794, 95% CI: 0.618–0.971). Notably, a binary logistic regression model developed using the same 21 optimized feature parameters as the GBC model achieved an AUC of 0.851 (95% CI: 0.767–0.935), which remained lower than that of the final model (Fig. 4C).

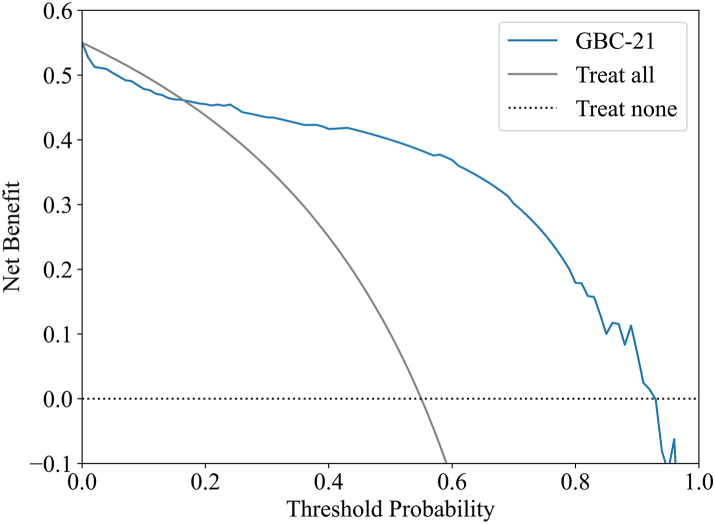

Clinical utility of the final ML model

As shown in Fig. 5, the DCA demonstrates that the net benefit of the final GBC model is consistently higher than both the full-intervention and none-intervention strategies across a threshold probability range of 0.16–0.93. The model's performance over this broad range suggests substantial clinical utility, reinforcing its potential to aid in clinical decision-making.

Fig. 5.

DCA of the final GBC model. The solid black line displays the net benefit of the strategy of treating all patients, and the black dotted line illustrates the net benefit of the strategy of treating no patients. DCA: decision curve analysis; GBC: gradient boosting classifier.

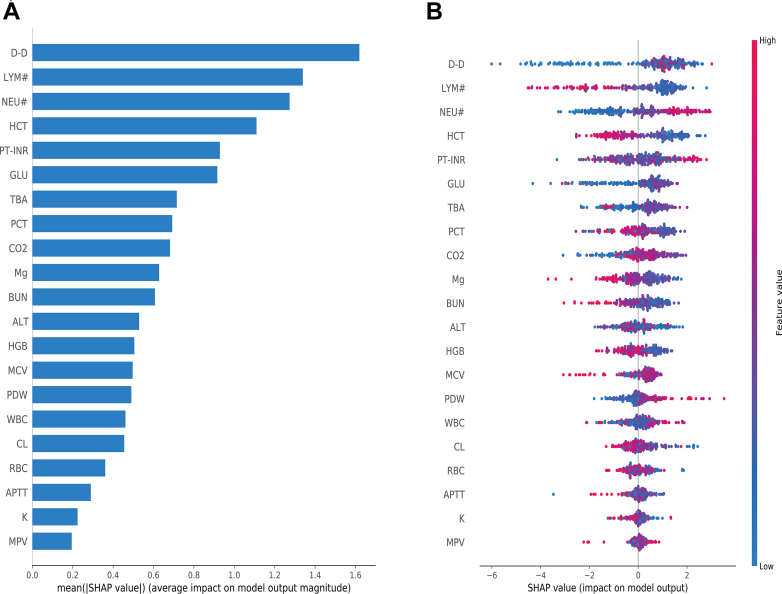

Model interpretation

To interpret the performance of our final model, we used SHAP to gain insights into feature contributions. The importance matrix graph (Fig. 6A) identified the importance of features, highlighting D-dimer, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count and hematocrit as the top four features with the most significant impact on model predictions. Fig. 6B visualizes the positive (red) or negative (blue) influence of each feature on the predicted probability, showing that higher levels of D-dimer and neutrophil count increase the risk of abnormal CT, while higher lymphocyte count and hematocrit levels have the opposite effect. Additionally, SHAP dependence plots for each feature are shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

Fig. 6.

Global explanation of the model by SHAP method. (A) Feature importance matrix plot. (B) SHAP summary plot. Each line represents a feature, and each data point represents a sample. High feature values are depicted in a red, low feature values in a blue. SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanation; D-D: D-dimer; LYM#: lymphocyte count; NEU#: neutrophils count; HCT: hematocrit; PT-INR: prothrombin time international normalized ratio; GLU: glucose; TBA: total bile acids; PCT: plateletcrit; CO2: carbon dioxide; Mg: magnesium; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; ALT: alanine transaminase; HGB: hemoglobin; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; PDW: platelet distribution width; WBC: white blood cell; CL: chlorine; RBC: red blood cell; APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; K: potassium; MPV: mean platelet volume.

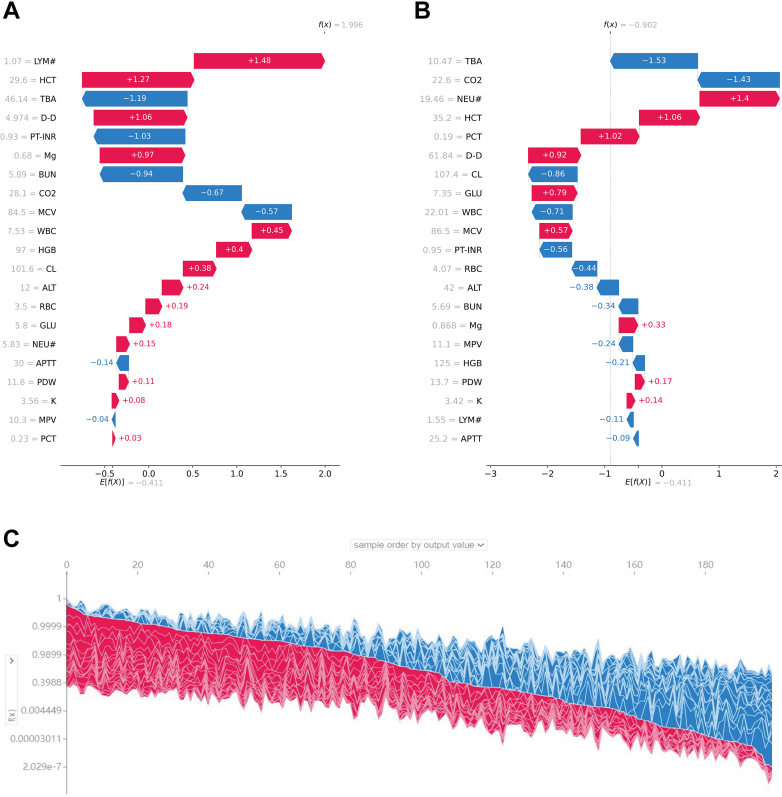

SHAP local explanation further illustrate how individual features influenced the likelihood of abnormal CT diagnosis (CT+ or CT−) for each patient. Fig. 7A and B highlight the SHAP values of key variables for a representative patient from the CT+ group and another from the CT− group. The SHAP values for all 817 patients in the training set are displayed in Fig. 7C.

Fig. 7.

Local explanation of the model by SHAP method. (A, B) SHAP values of two typical patients from the positive group (A) and the negative group (B) are illustrated with their most important variables. (C) SHAP values for all 817 patients in the training set. SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanation; D-D: D-dimer; LYM#: lymphocyte count; NEU#: neutrophils count; HCT: hematocrit; PT-INR: prothrombin time international normalized ratio; GLU: glucose; TBA: total bile acids; PCT: plateletcrit; CO2: carbon dioxide; Mg: magnesium; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; ALT: alanine transaminase; HGB: hemoglobin; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; PDW: platelet distribution width; WBC: white blood cell; CL: chlorine; RBC: red blood cell; APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; K: potassium; MPV: mean platelet volume.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an abnormal CT warning model for mTBI using seven ML algorithms and routine clinical test variables. All models achieved high performance, with AUCs ranging from 0.913 to 0.932. Among them, the GBC model performed the best, with the highest diagnostic performance, achieving an AUC of 0.932 (95% CI: 0.900–0.963), along with superior sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy, and F1 score. Feature selection further improved the GBC model's performance, addressing the limitations of using raw data, such as long training times, overfitting, and instability. SHAP and DCA results indicated that increased levels of D-dimer and neutrophil count emerged as the most important features for predicting abnormal CT findings, and our final GBC model could have a positive clinical benefit. Overall, our findings demonstrate that ML algorithms can serve as a feasible and effective approach for rapid triage of patients with varying risk levels in emergency departments dealing with TBI.

mTBI is the most common form of TBI and a key focus for early diagnosis and prognosis prediction using ML. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published study to use routine clinical laboratory data to differentiate between normal and abnormal CT scan findings in mTBI patients. Previous ML models, such as those based on EMR, natural language processing, and risk scoring, have shown diagnostic accuracy ranging from [0.80 to 0.99] in different TBI populations. In our study, the final GBC model achieved an AUC of 0.904 in the independent validation cohort and 0.885 in the prospective cohort, consistent with previous findings. These findings suggest that the GBC demonstrates strong repeatability and generalization capabilities. This may be attributed to the structure of GBC algorithm, which incrementally builds upon weak models (e.g., decision trees) to minimize prediction errors and improve overall performance.27 GBC has become widely adopted in medical applications for its robustness in handling classification tasks.28,29

In the early diagnosis and severity assessment of TBI, traditional methods like the GCS and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) rely heavily on physician judgment and the patient's verbal responses. These approaches are subject to variability, especially in cases of altered consciousness, impaired pain perception, or communication difficulties. This underscores the need for objective, reliable, and repeatable diagnostic tools that minimize individual assessor bias. In this study, we addressed this need by developing the final ML model to assist in identifying CT abnormalities in mTBI subgroups. The use of data sources like CT images, trauma markers, inflammatory indicators, and electric medical records for training TBI prediction models has grown rapidly. ML, with its ability to extract meaningful insights from large datasets, has become a preferred approach in medical research. However, the inclusion of too many clinical parameters can introduce complex interconnections between features, increasing the risk of noise and redundancy, thereby reducing the model's accuracy and generalizability.30 To overcome this, we used the RF algorithm for feature selection, ultimately narrowing down to a GBC model with 21 key features, creating a more streamlined and efficient prediction tool. In our double-blind prediction experiment involving mTBI patients with abnormal CT scans, the final model outperformed both traditional TBI biomarkers (GFAP and PGP9.5), as well as a binary logistic regression model built using the same selected 21 features. This highlights the superior diagnostic capability and generalization of our ML approach compared to conventional methods. Under the current influence of diagnosis related groups (DRG) payment rules and clinical pathways on laboratory medicine, ML technology can be utilized to screen key laboratory features that drive different TBI classifications, optimize the management of laboratory tests, control medical costs, and simultaneously improve the efficiency and quality of medical services.

Moreover, since the AUC method assumes a uniform distribution of threshold probabilities—which is not always reflective of real-world scenarios—we employed DCA to better estimate threshold probabilities. This allowed us to assess the clinical trade-offs between treating true positives and the potential harms of false positives.17 Our analysis revealed that the net benefit of the final ML model exceeded both the “full intervention” and “no intervention” strategies when threshold probabilities ranged from 0.16 to 0.93, underscoring the model's strong clinical utility.

As the use of ML in medicine has grown significantly, offering a viable strategy for distinguishing people at risk for TBI, another problem has arisen: Many frontline clinicians face challenges understanding the complex inner workings of these algorithms, leading to a lack of trust in the results—known as the “black box” problem.31 To address the interpretability of medical ML models, SHAP has emerged as a prominent tool for elucidating the significance of variables in medical contexts. We employed the SHAP method to clarify the decision-making mechanisms of the final GBC model, identifying D-dimer, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and hematocrit as the four most influential features for diagnosing mTBI patients with abnormal CT scans. Prior research corroborates that compromised coagulation function is pivotal in post-traumatic complications and is an established risk factor for mortality.32 Additionally, diminished levels of peripheral neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes are reliable markers of trauma severity and indicators of a poor prognosis.33,34 These findings align with the prioritization of features in our model. Furthermore, SHAP visualizations comparing mTBI patients (CT positive and CT negative) revealed notable differences in feature importance between groups, offering clinicians enhanced diagnostic clarity and underscoring critical laboratory parameters identified by our model.

Although developing a TBI prediction model based purely on routine clinical test data has achieved promising results in our study as a novel attempt, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the model was constructed using data from a single specialized brain hospital, and external validation was limited to one institution, which may affect its generalizability given variations in laboratory methods and reference ranges across centers. Second, while routine laboratory tests such as complete blood count, biochemistry, and electrolytes are often part of standard trauma evaluations, their necessity in all patients with mTBI is debatable and may limit the model's clinical applicability. Third, although laboratory tests offer objective biomarkers, they may not provide a clear time or cost advantage over head CT scans in emergency settings where rapid imaging and interpretation are available. Additionally, key clinical indicators such as GCS, injury severity score (ISS), and CT classification scores were not included, as all participants had mild injuries. Finally, patient labels were based on clinician-reported CT interpretations rather than direct image analysis, and features with substantial missing data were excluded, potentially omitting valuable predictors. Future studies should focus on multi-center validation, integration with imaging features, and prospective evaluation of clinical utility and cost-effectiveness.

In conclusion, the interpretable ML model developed based on routine clinical laboratory data serves as an auxiliary diagnostic tool for resource-limited medical institutions that may lack CT scanners and trained radiologists. By identifying high-risk mTBI patients who require CT evaluation, the model helps optimize resource allocation, reduce diagnostic delays, and support early medical intervention. Designed for seamless integration with hospital informatics systems using structured laboratory data as input, our model has the potential to enhance clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes, particularly in community outpatient settings where advanced imaging technology is unavailable. However, further evaluation is needed to validate its effectiveness across a broader range of clinical scenarios.

Contributors

MW, MJ, and YP was responsible for the conceptualization of the paper. MW, YP, TY, YL, and SW participated in data collection and management. YP and CL contributed expertise in clinical study design. MJ and FH was responsible for data analysis, models development and data visualization. MW provided statistical analysis. MW and YP drafted the original manuscript. CL, FH, and JT reviewed and performed revision of the manuscript. MW, MJ, and YP have access to and verify the underlying study data. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The dataset, protocol and statistical analysis methods used in the study can be requested directly from the corresponding author after approval. And the code for the seven models we used to GitHub (https://github.com/naomifang/GBC-CT).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (100504160736), high-level Talent Research Startup Funding of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine (100501070302), Wuhan Health and Family Planning Scientific Research Fund Project of Hubei Province (WX21C02), and Machine Learning-based Intelligent Diagnosis System for AFP-negative Liver Cancer Project (HX-KYXM2024019). The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, report writing, or the decision to submit the report for publication. All authors thank Huanming Wang (director of the Second Neurosurgery Ward at Wuhan Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital, email: 1808381741@qq.com) and Gang Li (chief physician of Critical Care Medicine at Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, email: marty007@163.com) for their hard work in the review and classification of CT scans for the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103192.

Contributor Information

Shimin Wu, Email: mintyrain@126.com.

Fang Hu, Email: naomifang@hbucm.edu.cn.

Chunzi Liang, Email: liangcz2021@hbucm.edu.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):56–87. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang J.Y., Gao G.Y., Feng J.F., et al. Traumatic brain injury in China. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):286–295. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas A., Menon D.K., Manley G.T., et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:1004–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00309-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terabe M.L., Massago M., Iora P.H., et al. Applicability of machine learning technique in the screening of patients with mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papa L., Ladde J.G., O'Brien J.F., et al. Evaluation of glial and neuronal blood biomarkers compared with clinical decision rules in assessing the need for computed tomography in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher-Sandersjoo A., Tatter C., Yang L., et al. Stockholm score of lesion detection on computed tomography following mild traumatic brain injury (SELECT-TBI): study protocol for a multicentre, retrospective, observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huibregtse M.E., Bazarian J.J., Shultz S.R., Kawata K. The biological significance and clinical utility of emerging blood biomarkers for traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;130:433–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swinckels L., Bennis F.C., Ziesemer K.A., et al. The use of deep learning and machine learning on longitudinal electronic health records for the early detection and prevention of diseases: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26 doi: 10.2196/48320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyagawa T., Saga M., Sasaki M., Shimizu M., Yamaura A. Statistical and machine learning approaches to predict the necessity for computed tomography in children with mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klement W., Wilk S., Michalowski W., Farion K.J., Osmond M.H., Verter V. Predicting the need for CT imaging in children with minor head injury using an ensemble of Naive Bayes classifiers. Artif Intell Med. 2012;54:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellethy H., Chandra S.S., Nasrallah F.A. Deep neural networks predict the need for CT in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury: a corroboration of the PECARN rule. J Am Coll Radiol. 2022;19:769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2022.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tunthanathip T., Duangsuwan J., Wattanakitrungroj N., Tongman S., Phuenpathom N. Comparison of intracranial injury predictability between machine learning algorithms and the nomogram in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2021;51:E7. doi: 10.3171/2021.8.FOCUS2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dusenberry M.W., Brown C.K., Brewer K.L. Artificial neural networks: predicting head CT findings in elderly patients presenting with minor head injury after a fall. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turcato G., Cipriano A., Park N., et al. “Decision tree analysis for assessing the risk of post-traumatic haemorrhage after mild traumatic brain injury in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy”. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22:47. doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00610-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundberg S., Lee S. 2017. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly C.J., Karthikesalingam A., Suleyman M., Corrado G., King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019;17:195. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadatsafavi M., Adibi A., Puhan M., Gershon A., Aaron S.D., Sin D.D. Moving beyond AUC: decision curve analysis for quantifying net benefit of risk prediction models. Eur Respir J. 2021;58 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01186-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carobene A., Milella F., Famiglini L., Cabitza F. How is test laboratory data used and characterised by machine learning models? A systematic review of diagnostic and prognostic models developed for COVID-19 patients using only laboratory data. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2022;60(12):1887–1901. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2022-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan Y., Fan Q., Liang Y., Liu Y., You H., Liang C. A machine learning prediction model for Cardiac Amyloidosis using routine blood tests in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-77466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allard C.B., Scarpelini S., Rhind S.G., et al. Abnormal coagulation tests are associated with progression of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2009;67(5):959–967. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ad5d37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijian K., Teo E.G., Kanesen D., Wong A.S.H. Initial leucocytosis and other significant indicators of poor outcome in severe traumatic brain injury: an observational study. Chin Neurosurg J. 2020;6:5. doi: 10.1186/s41016-020-0185-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L., Xia S., Zuo Y., et al. Systemic immune inflammation index and peripheral blood carbon dioxide concentration at admission predict poor prognosis in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Front Immunol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1034916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuh E.L., Jain S., Sun X., et al. Pathological computed tomography features associated with adverse outcomes after mild traumatic brain injury: a TRACK-TBI study with external validation in CENTER-TBI. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(9):1137–1148. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riemann L., Mikolic A., Maas A., Unterberg A., Younsi A., Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) Investigators and Participants Computed tomography lesions and their association with global outcome in young people with mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2023;40(11–12):1243–1254. doi: 10.1089/neu.2022.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chawla N.V., Bowyer K.W., Hall L.O., Kegelmeyer W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–357. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piovani D., Sokou R., Tsantes A.G., Vitello A.S., Bonovas S. Optimizing clinical decision making with decision curve analysis: insights for clinical investigators. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/healthcare11162244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowd C., Belghith A., Proudfoot J.A., et al. Gradient-boosting classifiers combining vessel density and tissue thickness measurements for classifying early to moderate glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;217:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rui F., Yeo Y.H., Xu L., et al. Development of a machine learning-based model to predict hepatic inflammation in chronic hepatitis B patients with concurrent hepatic steatosis: a cohort study. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;68 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reis E.P., Blankemeier L., Zambrano C.J., et al. Automated abdominal CT contrast phase detection using an interpretable and open-source artificial intelligence algorithm. Eur Radiol. 2024;34:6680–6687. doi: 10.1007/s00330-024-10769-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Sperrin M., Ashcroft D.M., van Staa T.P. Consistency of variety of machine learning and statistical models in predicting clinical risks of individual patients: longitudinal cohort study using cardiovascular disease as exemplar. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling K.R., Freethy A., Smith J., et al. Stakeholder perspectives towards diagnostic artificial intelligence: a co-produced qualitative evidence synthesis. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;71 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan Q., Yu J., Chen J., et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of coagulation disorders in the acute phase of traumatic brain injury (version 2024) Chin J Traumatol. 2024;40:310–322. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Wen D., Zhong H., et al. Dynamic changes of cellular immune function in trauma patients and its relationship with prognosis. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2021;33:223–228. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20200902-00604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo F., Zhao X., Deng J., et al. Early changes within the lymphocyte population are associated with the long term prognosis in severely injured patients. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;54:552–556. doi: 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2022.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.