This cohort study examines whether COVID-19 pandemic–related exposures are associated with changes in cognitive function among women aged 51 to 76 years.

Key Points

Question

Are the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related events associated with worse cognitive function in women?

Findings

In this cohort study of 5191 middle-aged women who completed 2 to 8 objective cognitive assessments both before and during the pandemic, there was no difference in cognitive function during the pandemic compared with the prepandemic period. History of SARS-CoV-2 infection or self-reported post–COVID-19 conditions showed no associations with cognitive scores, although these estimates had wide CIs.

Meaning

The findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related exposures were not associated with worse cognitive function in this nonclinical sample.

Abstract

Importance

The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with risk factors for cognitive decline, such as bereavement and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Objective

To examine whether the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related exposures are associated with cognitive function among middle-aged women.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study analyzed data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, an ongoing study of registered nurses in the US. The present study focused on women aged 51 to 76 years who completed 2 to 8 objective cognitive assessments both prior to (October 1, 2014, to February 29, 2020) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2020, to September 30, 2022). Statistical analyses were performed from January 2023 to January 2025.

Exposure

COVID-19 pandemic.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Two standardized (ie, z-scored) composite cognitive scores (psychomotor speed and attention, learning and working memory) and a global score constituted the primary outcomes. Higher scores indicated better cognitive function. Cognitive function was assessed using the Cogstate Brief Battery, a computer-administered cognitive test battery. Participants completed cognitive assessments every 6 to 12 months.

Results

A total of 5191 women (mean [SD] age at first cognitive assessment, 63.0 [4.8] years) completed both prepandemic and during-pandemic measures, contributing 23 678 cognitive assessments. After adjustment for age at cognitive assessment, educational level for both participants and their parents, cognitive test practice effects, and comorbidities (eg, diabetes, hypertension), no difference in cognitive function was observed between assessments taken during vs before the pandemic (psychomotor speed and attention: β = −0.01 SD [95% CI, −0.05 to 0.02 SD]; learning and working memory: β = 0.00 SD [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.03 SD]; global score: β = 0.00 SD [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.02 SD]). Among 4456 participants who responded to the COVID-19 substudy (ie, surveys about pandemic-related events), those with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (164 [3.7%]) or post–COVID-19 conditions (PCC; 62 [1.4%]), at a median (IQR) 20.0 (18.5-22.1) months after initial infection, had reduced cognitive function compared with women without infection or PCC; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance, and the wide CIs suggested considerable uncertainty.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study of middle-aged women found that the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related events were not associated with cognitive decline up to 2.5 years after the onset of the pandemic. Future studies are needed to examine the long-term implications of SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCC for cognitive function.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with increased prevalence of risk factors for cognitive decline, including social isolation1 and bereavement.2,3 COVID-19 illness has been linked to cognitive difficulties; brain fog lasting beyond the acute phase is commonly reported among individuals with post–COVID-19 condition (PCC).4,5,6

Many studies found that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with worse cognitive function in older adults,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 with only a few studies indicating no association or an association with improved function.15,16,17 Media coverage of these studies emphasized possible population-wide, long-lasting decreases in cognitive function as an outcome.18,19 However, most studies with objective cognitive assessments before and after the pandemic were small (<400 participants)7,8,9,11,12,13 and ended follow-up in the first year of the pandemic, an early and severe phase that may not be comparable to later years.14,16 The only large, longitudinal study with prepandemic and during-pandemic cognitive assessments of the same individuals was conducted in the UK and ended follow-up in February 2022. This UK study of 3000 older adults included 1 prepandemic and 1 to 2 during-pandemic cognitive assessments per person and found the pandemic was associated with worsened executive function and working memory, although decline in executive function was observed only in the first year of the pandemic.10

Studies have generally reported an association of a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection with lower cognitive function.7,8,9,10,20,21,22,23,24,25 Few of these studies had preinfection and postinfection cognitive measurements in individuals,9,10 and most had fewer than 100 participants or were conducted in hospital settings7,8,20,21,23; thus, their relevance to the general population is unknown. It is critical to know whether the pandemic accelerated cognitive decline in nonclinical populations so that efforts can be made to understand and mitigate, where possible, the sources of this decline. It is also important to know whether the pandemic did not accelerate cognitive decline to ensure that individuals do not incorrectly attribute their cognitive decline to the pandemic and seek appropriate care.

Women aged 65 years or older bear a higher burden of cognitive disorders than do men of the same age range.26,27,28,29 Evidence also suggests that women have a 1.5- to 2-fold greater risk than men of developing PCC and its associated cognitive concern.30,31 Thus, identifying the implications of the pandemic for cognitive function in older women has high public health salience. In the present study, we leveraged data from a large population-based longitudinal cohort of women with objective cognitive assessments obtained before (October 1, 2014, to February 29, 2020) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2020, to September 30, 2022) to examine the associations of the pandemic and pandemic-related exposures with cognitive function. We hypothesized that (1) population-level cognitive function would be worse during vs before the pandemic; (2) individuals with prepandemic risk factors for cognitive decline (eg, diabetes, depression) would have worse cognitive function during vs before the pandemic compared with persons without these risk factors; and (3) specific pandemic-related exposures (eg, SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCC) would be associated with worse cognitive function.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The cohort study protocol was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Boards. Return of questionnaires from participants implied their informed consent. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We used data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, an ongoing cohort study established in 1989, when 116 429 registered nurses aged 25 to 42 years living in the US were enrolled. Questionnaires are sent to participants biennially to collect lifestyle and health information. The response rate for each follow-up cycle exceeds 85%.

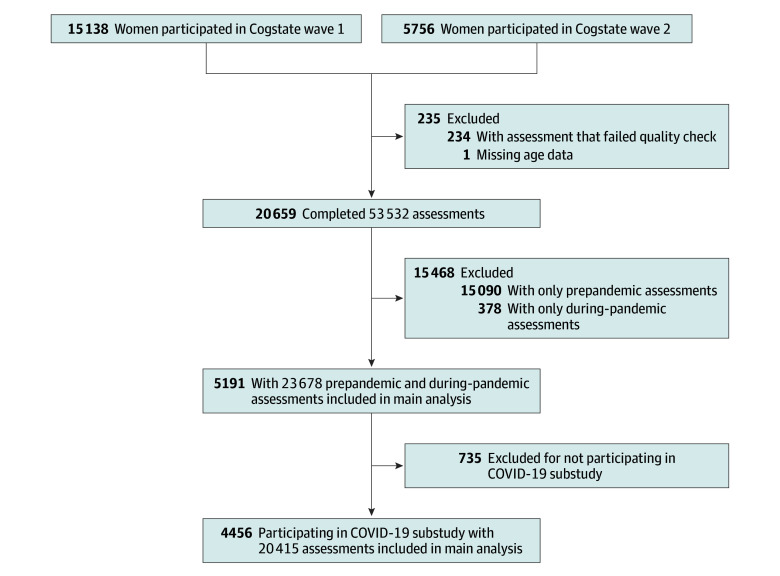

In 2014, 15 138 participants of the Nurses’ Health Study II joined a cognitive health substudy (eMethods in Supplement 1), with cognitive assessments at 6- or 12-month intervals for up to 24 months (hereafter wave 1).32 In 2018, 11 920 participants enrolled in wave 2, with follow-up every 12 months for up to 24 months (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). After exclusion of cognitive assessments that failed integrity checks,33 20 659 participants completed 53 532 cognitive assessments between October 1, 2014, and September 30, 2022 (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). At cohort enrollment, participants in the cognitive substudy were more likely to be White individuals, had slightly higher neighborhood socioeconomic status, and were less likely to have chronic conditions (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

The main analyses were restricted to 5191 women aged 51 to 76 years with both prepandemic and during-pandemic cognitive assessments (Figure 1; eTable 2 in Supplement 1). In April 2020, a COVID-19 substudy was launched to collect information on experiences during the pandemic,34 with the final questionnaire returned in November 2021. Participants in the COVID-19 substudy were included in the main analyses.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Study Design.

Exposure Assessment

The primary exposure was the COVID-19 pandemic. We considered October 1, 2014, to February 29, 2020, as the prepandemic period and March 1, 2020, to September 30, 2022, as the during-pandemic period.

Risk Factors for Cognitive Decline

We considered hypertension, diabetes, stroke, depression, and cancer as possible cognitive risk factors. History of physician-diagnosed hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cancer were self-reported biennially through 2017. Self-reported health outcomes have had high validity in cohorts of health professionals.35,36 Depression was derived from multiple indicators queried from 2010 to 2017, including self-reported physician-diagnosed depression, use of antidepressants, and depressive symptoms (assessed by the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale).37 Participants were considered to have a history of chronic depression if they reported any indicator of depression on both of the 2 most recent biennial questionnaires.38

Pandemic-Related Exposures

Secondary exposures included SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed by polymerase chain reaction, antigen, or antibody tests), PCC (defined as having >8 weeks of symptoms after initial infection, including fatigue; shortness of breath or difficulty breathing; persistent cough; muscle, joint, or chest pain; smell or taste problems; confusion, disorientation, or brain fog; memory issues; depression, anxiety, or changes in mood; headache; intermittent fever; heart palpitations; rash, blisters, or welts; mouth or tongue ulcers; and other symptoms),34 and death of loved ones during the pandemic (yes or no). These exposures were prospectively collected on each of the monthly or quarterly COVID-19 substudy follow-up surveys.

Outcome Assessment

Cognitive function was assessed with the Cogstate Brief Battery, a computer-administered cognitive test consisting of 4 tasks: detection task (measuring psychomotor function and information processing speed), identification task (measuring visual attention and vigilance), one-back task (measuring working memory), and one card learning task (measuring visual learning and short-term memory).33,39 Results for each task were log transformed or arcsine transformed to improve normality.40 For each task, scores were standardized (ie, z scored) using means and SDs at the wave 1 baseline, with a higher score indicating better cognitive function. We calculated 3 composites from the 4 individual z-scored tasks: (1) psychomotor speed and attention, consisting of the mean of the detection and identification tasks; (2) learning and working memory, consisting of the mean of the one card learning and one-back tasks; and (3) a global score, consisting of the mean of all 4 tasks.40 Cogstate composite scores have shown high test-retest reliability and correlate well with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment.41

Covariates

Covariates were selected a priori based on established association with SARS-CoV-2 infection, PCC, or cognitive function. On the initial cohort questionnaire, participants self-reported birth date, height, and racial identity (Which categories best describe your race? Response options provided by investigators included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, or other [including only participants who selected other as their racial identity]). We included race in the analysis because of its known associations with pandemic-related exposures and cognitive outcomes.42,43,44 The highest educational level of participants and their parents were collected in 2018 and 2005, respectively. Weight and smoking history were self-reported biennially, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.2 Frontline health care worker status (defined as physically working at a site providing health care) was self-reported at the COVID-19 substudy baseline.

Statistical Analysis

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and cognitive scores of participants with vs without both prepandemic and during-pandemic cognitive assessments. We also compared participant characteristics by wave of enrollment, total number of cognitive assessments, and participation in the COVID-19 substudy (eMethods in Supplement 1). Percentages of missing covariate data were 3% for BMI, 6% for parental educational level, and 19% for participant educational level. A missing indicator was used for categorical covariates; continuous covariates were imputed with the median value in the analytical sample.

Cognitive scores typically improve with practice45,46,47; therefore, we considered several methods to account for practice effects (eMethods in Supplement 1).47 The best-fitting model included an interaction between the number of prior cognitive assessments (0-7) and time since the previous assessment (6-9, 10-18, or >18 months). More previous cognitive assessments and a shorter interval between consecutive assessments were associated with greater improvement in all 4 tasks, particularly the one card learning task (eTable 3 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

To examine the association of the pandemic with cognitive function within individuals, we fit linear mixed-effects models (with an unstructured correlation matrix) with a random intercept for each participant. The pandemic was the independent variable and was coded as 1 if the cognitive assessment was conducted on or after March 1, 2020, or 0 if it was conducted before March 1, 2020, with each composite score being the dependent variable in separate models. The base model adjusted for age at cognitive assessment (years, linear and squared), number of previous cognitive assessments × time since most recent assessment, wave, and Cogstate platform version (eMethods in Supplement 1). A second model was further adjusted for racial identity (White vs other race [categories combined because of small sample sizes for racial minority groups]), parental and participant educational level, and time-varying BMI and history of disease (diabetes, hypertension, stroke, depression, and cancer, each of which was coded separately). To capture changes in cognitive function more proximate to the pandemic, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to wave 2 cognitive assessments (1-3 assessments per person). These assessments were administered in the 2 years before and 2 years after the onset of the pandemic (October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2022).

To evaluate whether the association between the pandemic and cognitive function was modified by risk factors (eg, hypertension and frontline health care worker status), we included a pandemic × risk-factor interaction term in the model, with mutual adjustment for the other risk factors. Statistical significance for additive interaction was estimated using the Wald test. A small number of people in the sample had a stroke (53 of 5191 [1.0%]); therefore, we examined cognitive function in association with only hypertension, diabetes, depression, cancer, and frontline health care worker status. Additionally, we estimated the association of pandemic-related exposures (namely, SARS-CoV-2 infection, PCC, and death of loved ones) with cognitive function by fitting each of the exposures as the independent variable in separate models among participants in the COVID-19 substudy (eMethods in Supplement 1).

We conducted several additional sensitivity analyses. First, we compared population-averaged cognitive function before and during the pandemic among all participants with cognitive assessments (1-8 assessments per person). We used linear regression models with generalized estimating equations (unstructured correlation matrix) with a stabilized inverse probability weight to account for differential loss to follow-up (eMethods in Supplement 1).48 Second, we performed multiple imputations with fully conditional specification using 50 imputed datasets to impute covariates.49 Third, we adjusted for additional potential confounders: socioeconomic indicators (Census tract percentage with bachelor’s degree and median household income) and lifestyle factors (smoking history, alcohol intake, and physical activity) assessed before the pandemic.

Statistical analyses were performed from January 2023 to January 2025 using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 20 659 women completed 53 532 Cogstate Brief Battery assessments (median [IQR] 2.0 [1.0-3.0] assessments per person), with 9249 assessments conducted after March 1, 2020. Participants had a mean (SD) age of 62.8 (4.9) years at the first cognitive assessment and 66.4 (4.6) years at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; 102 identified as American Indian or Alaska Native (0.5%), 223 as Asian (1.1%), 132 as Black or African American (0.6%), 19 as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (0.1%), and 20 183 as White (97.7%) (Table 1). Wave 2 new enrollees were, in general, 4 years older than wave 1 enrollees at first assessment, had poorer cognitive function, and had fewer assessments (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Women who completed both prepandemic and during-pandemic measures (n = 5191; mean [SD] age at first cognitive assessment, 63.0 [4.8] years) contributed 23 678 cognitive assessments (2-8 assessments per person) (Figure 1). Compared with those without both assessments (n = 15 468), these women had a higher educational level, fewer comorbidities, higher learning and working memory scores at first assessment, and 3 more assessments in general (Table 1). Participants with more assessments were younger at first assessment, less likely to have comorbidities, and had better cognitive function (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Of these 5191 participants, 4456 (85.8%) responded to the COVID-19 substudy, providing 20 415 cognitive assessments (Figure 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants With vs Without Cogstate Cognitive Assessments Both Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic .

| Characteristic | Participants, by prepandemic and during-pandemic Cogstate cognitive assessments, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Without (n = 15 468)a | With (n = 5191) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.7 (4.9) | 63.0 (4.8) |

| Racial identity, self-reported | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 87 (0.6) | 15 (0.3) |

| Asian | 165 (1.1) | 58 (1.1) |

| Black or African American | 113 (0.7) | 19 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 16 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| White | 15 087 (97.5) | 5096 (98.2) |

| Parental educational levelb | ||

| ≤High school diploma | 7114 (46.0) | 2399 (46.2) |

| Some college | 3670 (23.7) | 1159 (22.3) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 3709 (24.0) | 1349 (26.0) |

| Participant educational levelb | ||

| Associate’s degree | 2819 (18.2) | 1082 (20.8) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4778 (30.9) | 2105 (40.6) |

| ≥Graduate school | 4162 (26.9) | 1839 (35.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.6 (6.3) | 27.2 (6.2) |

| Chronic diseases | ||

| Hypertension | 6359 (41.1) | 2004 (38.6) |

| Diabetes | 1380 (8.9) | 401 (7.7) |

| Cancer | 3205 (20.7) | 998 (19.2) |

| Stroke | 229 (1.5) | 53 (1.0) |

| Asthma | 3220 (20.8) | 1056 (20.3) |

| Depression | 3093 (20.0) | 1006 (19.4) |

| z Score for psychomotor speed and attention, mean (SD)c | −0.05 (0.9) | −0.04 (0.9) |

| z Score for learning and working memory, mean (SD)c | −0.07 (0.7) | 0.04 (0.7) |

| No. of tests taken, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.8) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Overall, 15 090 participants had only prepandemic tests; 378 participants had only during-pandemic tests.

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to missing data.

Standardized to wave 1 tests at first cognitive assessment.

Cognitive scores decreased 0.1 to 0.2 SD across 8 years of follow-up except for the one card learning scores, which increased by approximately 0.8 SD, indicating practice effects (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). After adjusting for practice effects, each 5 years of aging was associated with 0.2 SD lower cognitive scores (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

We did not observe a change in cognitive function comparing within-individual prepandemic vs during-pandemic assessments after adjusting for age at cognitive assessment, educational level for both participants and their parents, cognitive test practice effects, comorbidities, wave, and test platform (psychomotor speed and attention: β = −0.01 SD [95% CI, −0.05 to 0.02 SD]; learning and working memory: β = 0.00 SD [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.03 SD]; global score: β = 0.00 SD [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.02 SD]) (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Results were similar in models further adjusting for racial identity, parental and participant educational level, BMI, and risk factors for cognitive decline (Figure 2). Results were also comparable in analyses restricted to wave 2 assessments (Figure 2; eTable 6 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Cogstate Cognitive Composite Scores During vs Before the COVID-19 Pandemic.

The association of the pandemic with cognitive function was examined using linear mixed-effects models with normal distribution and identity link, unstructured covariance structure, and random intercept for each participant (number of assessments per person: 2-8 for prepandemic and during-pandemic assessments; 1-3 for wave 2 assessments). Pandemic as the independent variable was coded 1 if assessment was on or after or 0 if assessment was before March 1, 2020. The model was adjusted for various factors, including age at baseline; age-squared; time since first test; practice effects (number of tests taken × time since last test); wave; test platform; racial identity; parental educational level; participant educational level; time-varying body mass index; smoking status; and history of diabetes, hypertension, stroke, depression, and cancer. Wave 2 assessments were administered 2 years before and 2 years after the pandemic.

As expected, individuals with cognitive risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, and depression) compared with those without had lower cognitive function both before and during the pandemic (eg, with diabetes vs without diabetes, before the pandemic: β = −0.09 SD [95% CI, −0.15 to −0.03 SD]; during the pandemic: β = −0.08 SD [95% CI, −0.17 to 0.00 SD]). However, we did not observe an interaction (all P for interaction >.10) of these risk factors with the pandemic (Table 2). Cognitive function of frontline health care workers was also not differentially affected by the pandemic (1169 of 4456 study participants [26.2%]) vs nonfrontline health care workers.

Table 2. Cogstate Cognitive Composite Scores Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Participants With vs Without Risk Factors for Cognitive Decline.

| Variable | Participants, No. | Cognitive assessments, No. | Global z scorea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI), SD | P value | |||

| History of hypertension | ||||

| Without hypertension, prepandemic | 3187 | 9145 | 0.00 [Reference] | NA |

| With hypertension, prepandemic | 2080 | 5834 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.00) | .05 |

| Without hypertension, during pandemic | 3103 | 5250 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | .73 |

| With hypertension, during pandemic | 2088 | 3449 | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.01) | .01 |

| Hypertension × pandemic interaction | NA | NA | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.01) | .22 |

| History of diabetes | ||||

| Without diabetes, prepandemic | 4790 | 13 852 | 0.00 [Reference] | NA |

| With diabetes, prepandemic | 430 | 1127 | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.03) | .004 |

| Without diabetes, during pandemic | 4758 | 7980 | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.01) | .23 |

| With diabetes, during pandemic | 433 | 719 | −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.00) | .06 |

| Diabetes × pandemic interaction | NA | NA | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.08) | .47 |

| History of depression | ||||

| Without depression, prepandemic | 4248 | 12 187 | 0.00 [Reference] | NA |

| With depression, prepandemic | 1061 | 2792 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | .13 |

| Without depression, during pandemic | 4197 | 7075 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | .56 |

| With depression, during pandemic | 994 | 1624 | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.01) | .02 |

| Depression × pandemic interaction | NA | NA | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | .16 |

| History of cancer | ||||

| Without cancer, prepandemic | 4193 | 12 086 | 0.00 [Reference] | |

| With cancer, prepandemic | 1086 | 2893 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.03) | .76 |

| Without cancer, during pandemic | 4098 | 6860 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | .40 |

| With cancer, during pandemic | 1093 | 1839 | −0.03 (−0.09 to 0.03) | .29 |

| Cancer × pandemic interaction | NA | NA | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | .54 |

| Frontline health care workerb | ||||

| Nonfrontline health care worker, prepandemic | 3287 | 9583 | 0.00 [Reference] | NA |

| Frontline health care worker, prepandemic | 1169 | 3331 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) | .29 |

| Nonfrontline health care worker, during pandemic | 3287 | 5550 | 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.03) | .94 |

| Frontline health care worker, during pandemic | 1169 | 1951 | −0.05 (−0.11 to 0.01) | .10 |

| Frontline health care worker × pandemic interaction | NA | NA | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) | .24 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Calculated with a multivariable-adjusted linear mixed-effects model with normal distribution and identity link, unstructured covariance structure, and random intercept for each participant (number of assessments per person: 2-8). Models included terms for time-varying risk factors (depression, diabetes, depression, cancer), time since first test, time-varying risk factors (depression, diabetes, depression, cancer) × time since first test, age at baseline, age-squared, practice effects (number of tests taken × time since last test), wave, test platform, racial identity, parental educational level, participant educational level, time-varying body mass index, and history of stroke.

Among participants of COVID-19 substudy who reported on health care working status during the pandemic. The model additionally included health care worker status × time since first test.

Participants in the COVID-19 substudy were similar to nonparticipants (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Cognitive assessments after SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred a median (IQR) of 20.0 (18.5-22.1) months after initial infection. Participants with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (164 of 4456 [3.7%]) did not have, groupwise, significantly worse cognitive function than those without infection (global score: β = −0.11 SD; 95% CI, −0.25 to 0.03 SD; P = .14) (eFigure 5 in Supplement 1). Participants reporting a history of PCC (62 of 4456 [1.4%]) compared with those without PCC did not have, groupwise, significantly worse cognitive function (global score: β = −0.11 SD; 95% CI, −0.37 to 0.14 SD; P = .38). Although the wide CIs indicated considerable uncertainty, point estimates for cognitive decline associated with both SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCC (eg, −0.11 SD) were equivalent to approximately 3 years of cognitive aging in this sample. Death of loved ones was not associated with cognition (global score: β = −0.02 SD; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.00 SD; P = .09). Results were comparable in analyses including all women with a cognitive assessment using multiple imputation and further adjusting for socioeconomic and lifestyle factors (eTable 6, eTable 8, and eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this large, prospective, nonclinical cohort study of women with both prepandemic and during-pandemic cognitive assessments, we found no evidence of population-wide cognitive decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, a finding that is contrary to our hypothesis and to anecdotal reports. As expected, the cognitive function of individuals with hypertension, diabetes, and depression was lower than the cognitive function of individuals without these risk factors. However, cognitive function in individuals with these risk factors was not differentially affected by the pandemic, and neither was the cognitive function of frontline health care workers.

Pandemic-related events, including SARS-CoV-2 infection, PCC, and death of loved ones, were not, in a groupwise manner, associated with statistically significant lower cognitive function. Although differences did not reach statistical significance and the low infection rate limited our ability to obtain a precise estimate of the associations, the level of cognitive function in participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection or PCC measured approximately 20 months after initial infection was equivalent to 3 years of aging compared with participants without infection or PCC. This substantively meaningful difference merits further investigation.

Studies have examined the association of cognitive impairment with the pandemic and SARS-CoV-2 infection. A large population-based study (>120 000 participants) conducted among older adults in long-term care facilities observed a lower incidence of cognitive impairment in the first year of the pandemic compared with the prepandemic period,16 although these findings may have been affected by survival bias. In contrast, another longitudinal study (>3000 participants) with prepandemic and during-pandemic cognitive assessments found that the pandemic was associated with cognitive decline.10 Two large prospective studies found a higher incidence of cognitive impairment or neurocognitive disorders in individuals 6 to 12 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection (compared with those who had never been infected); impairment was more pronounced in those with severe acute-phase symptoms.20,21 Several studies have also observed brain structure changes believed to be related to cognitive decline among persons with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.9,50,51 More recently, a large community study (>141 000 participants) conducted entirely after the pandemic found lower cognitive function in participants with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or PCC, with larger deficits observed among participants with ongoing PCC symptoms.25

In the present study, we observed no association between lower cognitive function and SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCC. There are several points to consider in the interpretation of the results. First, the sample was population based and included predominantly mild COVID-19 cases (<3.0% required hospitalization38), unlike studies involving severe cases. Second, the median time elapsed between infection and cognitive assessment was 20 months; therefore, symptoms may have abated before the assessments. Third, the Cogstate Brief Battery comprises objective measures of cognitive function, which may not capture subjective cognitive experiences, such as brain fog.52 It is possible that participants did experience such subjective cognitive symptoms, but it is still reassuring that they did not exhibit decrements on objective assessments. Fourth, the analyses focused on groupwise comparisons among individuals with pandemic-related exposures, and we cannot rule out the possibility of within-group heterogeneity in cognitive function.6,30

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study included a population-based longitudinal design, a large sample size, the ability to contrast prepandemic vs during-pandemic cognitive assessments using a well-validated instrument, and a follow-up duration of up to 2.5 years after the start of the pandemic (which enabled us to characterize cognitive function over a long period). We were able to examine subgroups of participants who may have been at greater risk for pandemic-related cognitive changes. A median of 20 months elapsed between infection and cognitive assessments; therefore, we may have captured longer-lasting outcomes of infection than prior studies.53,54

This study has several limitations. First, the data indicate both practice and dropout effects, which may have led to bias. However, results were robust to a variety of statistical adjustments. Second, previous studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 infection, PCC, and bereavement affect cognitive function in a dose-dependent manner according to severity or duration3,20,25; however, we lacked the data to examine severity or duration of these exposures. Third, due to the limited number of cognitive assessments during follow-up and the lack of a suitable comparison group unexposed to the pandemic, we were unable to use quasiexperimental study designs, such as interrupted time series or difference-in-differences. Fourth, the prepandemic measure of cognitive scores started from 2014, which might not reflect the most recent cognitive function patterns prior to the onset of the pandemic. However, results were similar in analyses using wave 2 cognitive assessments only (October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2022). Fifth, participants were homogenous in race (97.7% identified as White individuals), and all participants were registered nurses at cohort enrollment in 1989, limiting generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of middle-aged women, the COVID-19 pandemic and related events were not associated with cognitive function 2.5 years after the onset of the pandemic, even among those with risk factors for cognitive decline. Larger sample sizes and detailed subgroup symptom characterization are needed to better understand the long-term implications of SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCC for cognitive function.

eMethods

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Cognitive Health Sub-Study and COVID-19 Sub-Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II, October 1, 2014 – September 30, 2022

eFigure 2. Number of Cogstate Tests Obtained in Each Month of the Follow-up Period

eTable 1. Characteristics at Enrollment (1989) of Participants Included Versus Excluded in the Cognitive Sub-Study

eTable 2. Distribution of Total Number of Cognitive Tests During Follow-up

eTable 3. Estimated Practice Effects by Total Number of Tests Taken and Time Since Last Test

eFigure 3. Associations Between Age and Cogstate Composite Scores, Without (Panel A-B) and With (Panel C-D) Adjustment for Practice Effects

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics (at First Cognitive Assessment) of Eligible Participants by Wave of Enrollment

eTable 5. Comparing Baseline (First Test) Characteristics of Participants by Total Number of Cognitive Assessments Taken

eFigure 4. Unadjusted Mean Cognitive Test Scores (Z-Score) by Time Since First Test (Months)

eTable 6. Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With Cogstate Composite Scores, Comparing Cognitive Tests Taken During the Pandemic With Those Taken Before the Pandemic

eTable 7. Comparing Baseline (First Test) Characteristics of Participants Who Did vs Did Not Participate in the COVID-19 Sub-Study, Among the 5,191 Participants With Both Pre- and During- Pandemic Cognitive Assessments

eFigure 5. Associations of Pandemic-Related Exposures With Cogstate Composite Scores, Among Participants in the COVID-19 Sub-Study and With Both Pre- and During- Pandemic Cognitive Assessments

eTable 8. Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With Cogstate Composite Scores, Comparing Cognitive Tests Taken During the Pandemic With Those Taken Before the Pandemic, Using Multiple Imputation

eTable 9. Associations of Pandemic-Related Exposures With Cogstate Composite Scores, Among Participants in the COVID-19 Sub-Study, With Additional Adjustment for Socioeconomic and Lifestyle Factors

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cardona M, Andrés P. Are social isolation and loneliness associated with cognitive decline in ageing? Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1075563. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1075563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singham T, Bell G, Saunders R, Stott J. Widowhood and cognitive decline in adults aged 50 and over: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101461. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pérez HCS, Ikram MA, Direk N, Tiemeier H. Prolonged grief and cognitive decline: a prospective population-based study in middle-aged and older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(4):451-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng N, Zhao YM, Yan W, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: call for research priority and action. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(1):423-433. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01614-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93-135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wulf Hanson S, Abbafati C, Aerts JG, et al. ; Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators . Estimated global proportions of individuals with persistent fatigue, cognitive, and respiratory symptom clusters following symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA. 2022;328(16):1604-1615. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.18931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Brutto OH, Wu S, Mera RM, Costa AF, Recalde BY, Issa NP. Cognitive decline among individuals with history of mild symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a longitudinal prospective study nested to a population cohort. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3245-3253. doi: 10.1111/ene.14775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Brutto OH, Rumbea DA, Recalde BY, Mera RM. Cognitive sequelae of long COVID may not be permanent: a prospective study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(4):1218-1221. doi: 10.1111/ene.15215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;604(7907):697-707. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbett A, Williams G, Creese B, et al. Cognitive decline in older adults in the UK during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of PROTECT study data. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4(11):e591-e599. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00187-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Araújo N, Costa A, Lopes-Conceição L, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy and cognitive decline in the NEON-PC prospective study during the COVID-19 pandemic. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100448. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hausman HK, Dai Y, O’Shea A, et al. The longitudinal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors, psychosocial factors, and cognitive functioning in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:999107. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.999107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noguchi T, Kubo Y, Hayashi T, Tomiyama N, Ochi A, Hayashi H. Social isolation and self-reported cognitive decline among older adults in Japan: a longitudinal study in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(7):1352-1356.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung J, Kim S, Kim B, et al. Accelerated cognitive function decline in community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19 pandemic: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gollop C, Zingel R, Jacob L, Smith L, Koyanagi A, Kostev K. Incidence of newly-diagnosed dementia after COVID-19 infection versus acute upper respiratory infection: a retrospective cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;93(3):1033-1040. doi: 10.3233/JAD-221271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webber C, Myran DT, Milani C, et al. Cognitive decline in long-term care residents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1456-1458. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.17214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogueira J, Gerardo B, Silva AR, et al. Effects of restraining measures due to COVID-19: pre- and post-lockdown cognitive status and mental health. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(10):7383-7392. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01747-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paris F. Can’t think, can’t remember: more Americans say they’re in a cognitive fog. The New York Times. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/13/upshot/long-covid-disability.html

- 19.Gregory A. Covid pandemic ‘had lasting impact’ on brain health of people aged 50 or over. The Guardian. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/nov/01/pandemic-had-lasting-impact-on-brain-health-of-people-aged-50-or-over

- 20.Liu YH, Chen Y, Wang QH, et al. One-year trajectory of cognitive changes in older survivors of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(5):509-517. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampshire A, Trender W, Chamberlain SR, et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101044. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poletti S, Palladini M, Mazza MG, et al. ; COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study Group . Long-term consequences of COVID-19 on cognitive functioning up to 6 months after discharge: role of depression and impact on quality of life. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;272(5):773-782. doi: 10.1007/s00406-021-01346-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheetham NJ, Penfold R, Giunchiglia V, et al. The effects of COVID-19 on cognitive performance in a community-based cohort: a COVID symptom study biobank prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;62:102086. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hampshire A, Azor A, Atchison C, et al. Cognition and memory after COVID-19 in a large community sample. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(9):806-818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2311330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niu H, Álvarez-Álvarez I, Guillén-Grima F, Aguinaga-Ontoso I. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in Europe: a meta-analysis. Neurologia. 2017;32(8):523-532. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CC, Li CY, Sun Y, Hu SC. Gender and age differences and the trend in the incidence and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: a 7-year national population-based study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5378540. doi: 10.1155/2019/5378540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beam CR, Kaneshiro C, Jang JY, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL, Gatz M. Differences between women and men in incidence rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(4):1077-1083. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine DA, Gross AL, Briceño EM, et al. Sex differences in cognitive decline among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210169. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1706-1714. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perlis RH, Santillana M, Ognyanova K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of long COVID symptoms among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238804. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts AL, Liu J, Lawn RB, et al. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with accelerated cognitive decline in middle-aged women. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2217698. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.17698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredrickson J, Maruff P, Woodward M, et al. Evaluation of the usability of a brief computerized cognitive screening test in older people for epidemiological studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(2):65-75. doi: 10.1159/000264823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Quan L, Chavarro JE, et al. Associations of depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, and loneliness prior to infection with risk of post-COVID-19 conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(11):1081-1091. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forman JP, Curhan GC, Taylor EN. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension among young women. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):828-832. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.117630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet. 1991;338(8770):774-778. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90664-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77-84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, Quan L, Ding M, et al. Depression, worry, and loneliness are associated with subsequent risk of hospitalization for COVID-19: a prospective study. Psychol Med. 2023;53(9):4022-4031. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722000691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim YY, Ellis KA, Harrington K, et al. ; The Aibl Research Group . Use of the CogState Brief Battery in the assessment of Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive impairment in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34(4):345-358. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.643227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koyama AK, Hagan KA, Okereke OI, Weisskopf MG, Rosner B, Grodstein F. Evaluation of a self-administered computerized cognitive battery in an older population. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(4):264-272. doi: 10.1159/000439592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maruff P, Lim YY, Darby D, et al. ; AIBL Research Group . Clinical utility of the cogstate brief battery in identifying cognitive impairment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Psychol. 2013;1(1):30. doi: 10.1186/2050-7283-1-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):362-373. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weuve J, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Cognitive aging in Black and White Americans: cognition, cognitive decline, and incidence of Alzheimer disease dementia. Epidemiology. 2018;29(1):151-159. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zahodne LB, Manly JJ, Azar M, Brickman AM, Glymour MM. Racial disparities in cognitive performance in mid- and late adulthood: analyses of two cohort studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):959-964. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hausknecht JP, Halpert JA, Di Paolo NT, Moriarty Gerrard MO. Retesting in selection: a meta-analysis of coaching and practice effects for tests of cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):373-385. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartels C, Wegrzyn M, Wiedl A, Ackermann V, Ehrenreich H. Practice effects in healthy adults: a longitudinal study on frequent repetitive cognitive testing. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vivot A, Power MC, Glymour MM, et al. Jump, hop, or skip: modeling practice effects in studies of determinants of cognitive change in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(4):302-314. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119-128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Y, Li X, Geng D, et al. Cerebral micro-structural changes in COVID-19 patients: an MRI-based 3-month follow-up study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100484. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heine J, Schwichtenberg K, Hartung TJ, et al. Structural brain changes in patients with post-COVID fatigue: a prospective observational study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101874. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serrano Del Pueblo VM, Serrano-Heras G, Romero Sánchez CM, et al. Brain and cognitive changes in patients with long COVID compared with infection-recovered control subjects. Brain. 2024;147(10):3611-3623. doi: 10.1093/brain/awae101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang AC, Kern F, Losada PM, et al. Dysregulation of brain and choroid plexus cell types in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2021;595(7868):565-571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03710-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernández-Castañeda A, Lu P, Geraghty AC, et al. Mild respiratory COVID can cause multi-lineage neural cell and myelin dysregulation. Cell. 2022;185(14):2452-2468.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Cognitive Health Sub-Study and COVID-19 Sub-Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II, October 1, 2014 – September 30, 2022

eFigure 2. Number of Cogstate Tests Obtained in Each Month of the Follow-up Period

eTable 1. Characteristics at Enrollment (1989) of Participants Included Versus Excluded in the Cognitive Sub-Study

eTable 2. Distribution of Total Number of Cognitive Tests During Follow-up

eTable 3. Estimated Practice Effects by Total Number of Tests Taken and Time Since Last Test

eFigure 3. Associations Between Age and Cogstate Composite Scores, Without (Panel A-B) and With (Panel C-D) Adjustment for Practice Effects

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics (at First Cognitive Assessment) of Eligible Participants by Wave of Enrollment

eTable 5. Comparing Baseline (First Test) Characteristics of Participants by Total Number of Cognitive Assessments Taken

eFigure 4. Unadjusted Mean Cognitive Test Scores (Z-Score) by Time Since First Test (Months)

eTable 6. Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With Cogstate Composite Scores, Comparing Cognitive Tests Taken During the Pandemic With Those Taken Before the Pandemic

eTable 7. Comparing Baseline (First Test) Characteristics of Participants Who Did vs Did Not Participate in the COVID-19 Sub-Study, Among the 5,191 Participants With Both Pre- and During- Pandemic Cognitive Assessments

eFigure 5. Associations of Pandemic-Related Exposures With Cogstate Composite Scores, Among Participants in the COVID-19 Sub-Study and With Both Pre- and During- Pandemic Cognitive Assessments

eTable 8. Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With Cogstate Composite Scores, Comparing Cognitive Tests Taken During the Pandemic With Those Taken Before the Pandemic, Using Multiple Imputation

eTable 9. Associations of Pandemic-Related Exposures With Cogstate Composite Scores, Among Participants in the COVID-19 Sub-Study, With Additional Adjustment for Socioeconomic and Lifestyle Factors

Data Sharing Statement