To the Editor,

The congenital solitary functioning kidney (cSFK) is a condition within the spectrum of Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract (CAKUT), which collectively represent the primary cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the pediatric population [1]. Although CAKUT are highly prevalent, the long-term prognosis of cSFK remains incompletely understood [2]. Emerging data suggest that CKD outcomes in cSFK may be less favorable than previously assumed, with a reported prevalence up to 60% [3, 4]. A critical challenge for patients with cSFK lies in the transition from pediatric to adult care. The compensatory hyperfiltration capacity in children often obscures early signs of renal impairment, leading to under-recognition of CKD risk as these patients age. This gap may result in patients being lost at follow-up during transition, with no standardized monitoring protocols to ensure continuity of care [5]. Moreover, the cause of CKD may be frequently misassigned to other comorbidities rather than to CAKUT in adults [6]. Given that many CAKUT patients present as late referrals CKD in early adulthood, recognition of subclinical renal damage could significantly facilitate management in this population. In this context, longitudinal kidney diameter serves as a marker of compensatory hypertrophy and hyperfiltration in cSFK, though the durability of this compensation is uncertain [3, 4, 7, 8]. While recent guidelines prioritize ultrasound (US) for renal assessment and have limited renal scintigraphy (RS) use due to advancements in US diagnostics, specific settings allow accurate renal function assessment [9–11]. However, standard clinical evaluation—including creatinine, proteinuria and blood pressure—may inadequately capture early kidney dysfunction in these patients [12].

This study aimed to evaluate outcomes in cSFK patients using multiple methodologies to assess renal function, focusing initially on standard markers and subsequently incorporating RS to enhance function measurement, exploring whether these approaches may improve CKD detection and support a smoother transition of care from pediatric to adult nephrology settings.

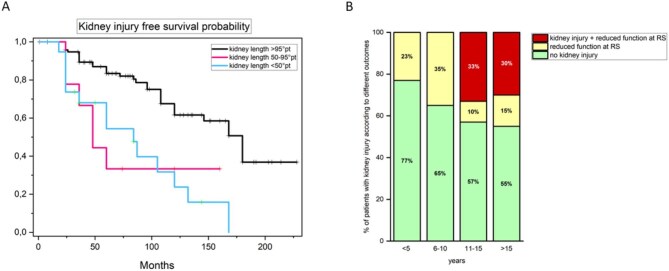

We enrolled 163 patients with cSFK, who were referred to our tertiary care hospital from the regional medical centers from 1997 to 2021 (Supplementary data, Table S1). We used a composite outcome to define kidney injury [i.e. presence of one among proteinuria, hypertension or impaired estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by CKiD-U25 formula] (for definitions see Supplementary data) [3, 4, 7, 8]. The mean follow-up duration was 84 months [interquartile range (IQR) 60–132 months]. The overall prevalence of the kidney injury at the last follow-up was 18% (29/162), occurring at a median age of 105 months (IQR 42–139 months) (Supplementary data, Table S2). In detail, we observed proteinuria, hypertension, decreased eGFR in 14/161 (8.7%), 22/143 (15.4%) and 19/106 (17.9%) patients with cSFK, respectively. The median age of development of proteinuria, hypertension and decreased eGFR was 168 months (IQR 120–206 months), 115 months (IQR 82–162 months) and 146 months (IQR 104–180 months), respectively. At univariate analysis, the only clinical and instrumental feature associated with the risk of developing kidney injury in our cohort was extrarenal signs [hazard ratio (HR) 2.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.27–5.78; P = .010], while height-adjusted kidney length >50th and >95th percentile at referral was protective (Table 1). Adjusted multivariate analysis confirmed only kidney length >95th percentile as significantly associated with a lower risk of kidney injury (HR 0.17, CI 0.07–0.43; P < .001). Of note, 8/17 (47%) patients with kidney length <50th percentile showed early kidney injury at a median age of 66 months (IQR 28–124.75 months; Fig. 1A). Conversely, 18/108 patients (16.6%) with kidney length at referral >50th percentile (16/18 with a kidney length ≥95th percentile) showed kidney injury at last follow-up (Fig. 1A), accounting for 62% (18/29) of patients showing kidney injury in the whole study population. They developed the outcome at a later median age compared with patients with kidney length <50th percentile at referral (144 months, IQR 108–180 months, P = .004). Since multivariate analysis did not identify any variable significantly associated with the risk of developing kidney injury in this group (Supplementary data, Table S3), we explored the potential role of RS to identify patients with subtle kidney injury among those with kidney length >50th percentile. We considered only RS performed after 24 months of age, since kidney function stabilizes after this time point, as previously reported [13]. Among 101 patients with available data, 64 (63.4%) showed normal kidney function at RS at a median age of 120 months (IQR 102–168 months), while 37 (36.6%) showed reduced kidney function at a median age of 132 months (IQR 77–180 months; P = .143) (Fig. 1A) during follow-up. Clinical features at referral were indistinguishable in these two groups (Supplementary data, Table S4). Among 37 patients with reduced kidney function at RS, the diagnosis of kidney injury was anticipated by about 42 months by RS in 14 patients (37.8%) who showed one out of proteinuria, hypertension or reduced eGFR at a median age of 150 months (IQR 117–180 months). Of note, in this subgroup all the patients had kidney length ≥95th percentile. Moreover, RS showed decreased kidney function in the absence of other features of kidney injury at last follow-up in 23 additional patients (23/101, 22.7%), especially in the first decade of life (Fig. 1B). In this group RS was performed at a median age of 48 months (IQR 2–72 months). Although this group was younger than those with CKD at last follow-up (91 vs 174 months, P < .001), RS allowed us to increase the overall CKD diagnostic rate early during follow-up (Fig. 1B).

Table 1:

Univariate and multivariate analysis for CKD composite outcome.

| Crude HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (ref. male), female | 0.79 (0.35–1.80) | .581 | ||

| Ethnicity (ref. Caucasian), Asian | 1.20 (0.29–5.06) | .803 | ||

| Complications during gestationa | 0.69 (0.20–2.46) | .570 | ||

| Gestational age at birth | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | .748 | ||

| Birth weight | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .622 | ||

| Perinatal complicationsb | 2.09 (0.73–6.00) | .167 | ||

| Postnatal diagnosis (ref. prenatal) | 0.65 (0.30–1.40) | .271 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (if postnatal) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | .153 | ||

| Diagnosis (ref. unilateral renale agenesis) | 1.44 (0.66–3.12) | .359 | ||

| Family history | ||||

| Renal | 0.82 (0.30–2.27) | .708 | ||

| Extrarenalc | 1.34 (0.36–4.92) | .661 | ||

| Extra-renal signsc | 2.71 (1.27–5.78) | .010 | 1.80 (0.74–4.38) | .196 |

| Associated CAKUTd | 1.62 (0.78–3.38) | .194 | ||

| Growth retardation | 2.50 (0.85–7.16) | .099 | ||

| BMI | 2.01 (0.93–4.32) | .073 | ||

| Kidney length percentile at referral | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | <.001 | ||

| Kidney length percentile at referral (ref. group <50th percentile): | ||||

| Group 50th–95th percentile | 0.13 (0.03–0.61) | .010 | 0.20 (0.04–1.06) | .059 |

| Group >95th percentile | 0.15 (0.06–0.36) | <.001 | 0.17 (0.07–0.43) | <.001 |

Eclampsia, preeclampsia, hypertension, proteinuria, hemorrhages during gestation, iron and vitamin deficiencies.

Respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, hypothermia, hypoglycemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, septicemia.

Cardiac morphological abnormalities, cerebral morphological abnormalities, bone abnormalities, gastrointestinal morphological abnormalities, morphological abnormalities of the visual and hearing system, endocrinopathy.

Ureter dilatation, ureter dilatation, hypodysplasia, ectopia, ureterocele, Hutch's diverticulum, bladder abnormality PU duplication, pelvic dilatation, calyceal dilatation, vesicoureteral reflux.

BMI, body mass index.

Figure 1:

(A) Kaplan–Meier curves showing kidney injury-free survival in cSFK patients, grouped by renal length percentiles at referral: <50th, 50th–94th and >95th. Kidney injury includes proteinuria, hypertension, reduced eGFR or decreased function by RS. Time to injury was measured from start of follow-up to injury onset or last follow-up. Log-Rank test P = .6. (B) Rate of kidney injury diagnosis stratified by age group in patients with kidney length >50th percentile, highlighting the additional diagnostic yield of RS in patients with cSFK. The bars represent the proportion of patients diagnosed with kidney injury through RS alone (yellow), without other clinical signs of renal damage (e.g. reduced eGFR, hypertension or proteinuria) (red) and without kidney injury (green), demonstrating the incremental value of RS in uncovering subclinical kidney injury before other signs appear.

Animal models suggest that patients with cSFK have approximately 70% of the nephron endowment of individuals with two kidneys, predisposing them to an increased risk of kidney injury over time. Clinical observations support this data, though results vary due to differences in study design, inclusion criteria and CKD definitions. Our findings confirm CKD as a common and early complication in pediatric cSFK, observed in 18% of patients (median age 105 months) during follow-up. This aligns with previous reports, reinforcing the need for early identification of at-risk patients. Kidney US remains a primary tool for diagnosing and prognosticating cSFK. Our analysis is in line with previous studies reporting height-adjusted kidney length above the 95th percentile as the strongest protective factors against CKD [4, 8]. Notably, the initial increase in kidney length is mirrored by a function increase in cSFK patients, suggesting a correlation in early years. However, as size and function plateau, US may become a less reliable indicator of function over time. Our analysis highlights that RS increased kidney injury detection by over 20%, identifying function decline even in patients with kidney length >95th percentile, traditionally considered low risk. This finding underscores the value of RS or other precise GFR measurements in detecting subclinical renal decline, a critical insight as many CAKUT patients are lost at follow-up and present to adult nephrology as late referrals. While recent studies and guidelines have aimed to identify patients at increased risk of kidney injury using parameters similar to ours [3, 4], they have concurrently recommended reducing the use of invasive imaging for renal function assessment [9, 10]. More accurate methods of function assessment such as cystatin C or US kidney volume measure could further improve stratification [9]. Early recognition of these at-risk patients could allow nephrologists to implement targeted follow-up and management strategies, even in patients who may appear clinically stable. Study limitations include its retrospective, single-center design, small sample size, and lack of newer markers (e.g. cystatin C) or US methods (e.g. volume assessment) potentially improving detection of kidney injury. Nonetheless, this work supports the need for standardized, long-term follow-up protocols in cSFK patients, bridging the gap between pediatric and adult nephrology care. Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and to refine follow-up schedules for optimal management of CKD risk in this population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

L.C. and F.B. are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases (ERKNet).

Contributor Information

Luigi Cirillo, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy.

Tommaso Mazzierli, Residency School of Nephrology, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Alessandra Bettiol, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Andrea La Tessa, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy; Department of Biomedical, Experimental and Clinical Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Marco Moscato, Residency School of Nephrology, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Samantha Innocenti, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy; Department of Biomedical, Experimental and Clinical Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Elisa Buti, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy.

Carmela Errichiello, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy.

Marco Materassi, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy.

Catia Olianti, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy; Nuclear Medicine Unit, Careggi Hospital, Florence, Italy.

Lorenzo Masieri, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy; Urology Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy.

Francesca Becherucci, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Meyer Children's Hospital IRCCS, Florence, Italy; Department of Biomedical, Experimental and Clinical Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

FUNDING

This study was supported in part by funds from the “Current Research Annual Funding” of the Italian Ministry of Health.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

L.C., T.M. and F.B. designed the study and interpreted the data. T.M., A.L.T., M.M., S.I., E.B. and C.E. collected data. A.B. performed statistical analysis. L.C., T.M. and F.B. wrote the manuscript and organized the figures. M.M., L.M., C.O. and F.B. critically revised the manuscript and advised on data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cirillo L, De Chiara L, Innocenti S et al. Chronic kidney disease in children: an update. Clin Kidney J 2023;16:1600–11. 10.1093/ckj/sfad097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marzuillo P, Di Sessa A, Guarino S et al. Kidney injury and congenital solitary functioning kidney: more research efforts are needed. Kidney Int 2023;103:427–8. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Groen In ’t Woud S, Roeleveld N, Westland R et al. Uncovering risk factors for kidney injury in children with a solitary functioning kidney. Kidney Int 2023;103:156–65. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsell DG, Bao C, White TP et al. Kidney length standardized to body length predicts outcome in infants with a solitary functioning kidney. Pediatr Nephrol 2023;38:173–180. 10.1007/s00467-022-05544-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jawa NA, Rosenblum ND, Radhakrishnan S et al. Reducing unnecessary imaging in children with multicystic dysplastic kidney or solitary kidney. Pediatrics 2021;148:e2020035550. 10.1542/peds.2020-035550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ortiz A, Kramer A, Ariceta G et al. Inherited kidney disease and CAKUT are common causes of kidney failure requiring kidney replacement therapy: an ERA Registry study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2025;40:1020–31. 10.1093/ndt/gfae240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guarino S, Di Sessa A, Riccio S et al. Early renal ultrasound in patients with congenital solitary kidney can guide follow-up strategy reducing costs while keeping long-term prognostic information. J Clin Med Res 2022;11:1052. 10.3390/jcm11041052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marzuillo P, Guarino S, Grandone A et al. Congenital solitary kidney size at birth could predict reduced eGFR levels later in life. J Perinatol 2019;39:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groen In ’t Woud S, Westland R, Feitz WFJ et al. Clinical management of children with a congenital solitary functioning kidney: overview and recommendations. Eur Urol Open Sci 2021;25:11–20. 10.1016/j.euros.2021.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. La Scola C, Ammenti A, Bertulli C et al. Management of the congenital solitary kidney: consensus recommendations of the Italian Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Pediatr Nephrol 2022;37:2185–207. 10.1007/s00467-022-05528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taylor AT. Radionuclides in nephrourology, part 1: radiopharmaceuticals, quality control, and quantitative indices. J Nucl Med 2014;55:608–15. 10.2967/jnumed.113.133447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Westland R, Abraham Y, Bökenkamp A et al. Precision of estimating equations for GFR in children with a solitary functioning kidney: the KIMONO study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:764–72. 10.2215/CJN.07870812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Filler G, Sharma AP, Exantus J. GFR and eGFR in term-born neonates. J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;33:1229–31. 10.1681/ASN.2022040470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.