Abstract

Background: Foreign body airway obstruction is a sudden emergency that can occur unexpectedly in healthy people, leading to severe consequences if immediate first aid is not provided. Unlike the Heimlich maneuver for adults, the first aid for infant choking is less widely known and more complex, making it difficult to explain verbally. This study aimed to assess the efficiency of using an animated graphics interchange format (GIF) to teach first aid for infant choking due to foreign bodies. Methods: Eighty adults who had not received recent training in choking first aid within the last two years were randomly assigned to either the auditory (n = 40) or audiovisual (n = 40) groups. The participants were asked to perform first aid on an infant manikin under the guidance of a researcher using a smartphone in a separate room. The auditory group received verbal instructions only, while the audiovisual group received animated GIFs on their smartphones along with verbal instructions simultaneously. The entire process was recorded with two cameras, and two emergency physicians reviewed the videos to assess the adequacy of the first aid administered. Results: The “infant position”, “supporting arm posture”, and “head tilt” were more adequate in the audiovisual group. The Instruction Performance scores were higher in the audiovisual group. There was no significant difference in the time required to administer first aid between the two groups. Conclusions: Audiovisual guidance using animated GIFs has been shown to effectively enhance the adequacy of first-aid performance for infant airway obstruction caused by foreign bodies.

Keywords: airway obstruction, animated GIFs, emergency medical system, first aid, pediatric emergency medicine

1. Introduction

Foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO) is a sudden emergency that can occur unexpectedly, especially during eating, even in healthy individuals. Delaying immediate emergency treatment for FBAO can lead to severe consequences, such as a vegetative state or death [1]. According to the most recent guidelines of the American Heart Association from 2020, in cases of severe airway obstruction in adults or children over 1 year of age, whether conscious or not, it is crucial to call “Emergency Medical Services (EMS)” immediately and perform abdominal thrusts repeatedly until the obstruction is cleared or the patient loses consciousness. For infants under 1 year old, alternating between five back blows and five chest thrusts is recommended [2].

Explaining the appropriate first aid for FBAO to an untrained individual over the phone can be challenging, and inappropriate first-aid measures may waste precious time in treating the patient [3,4]. While the Heimlich maneuver for adult FBAO is relatively well known, first aid for infant FBAO is less familiar to those without prior training.

In the United States, FBAO is a leading cause of accidental death among infants and the fourth leading cause of death among preschoolers aged 5 years or younger [5]. A study on airway obstruction time and prognosis in patients with FBAO reported that only 42% of bystanders provided accurate first aid for adult FBAO [1]. Igarashi et al. estimated that the rate of accurate first-aid provision for infants under 1 year old with FBAO may be even lower [3].

It is crucial to accurately replicate airway obstruction emergency treatment methods for effective first aid in cases of infant FBAO [6] and to explore how laypersons can better replicate complex infant FBAO first-aid methods. However, relevant studies in this field remain scarce.

Improving the accuracy and immediacy of first aid will help prevent serious complications, such as hypoxia and brain damage, in infants due to airway obstruction and improve overall survival.

To enhance both accuracy and immediacy, it is important to deliver first-aid information more quickly and precisely, which may be effectively achieved through visual-based interventions [7].

With advancements in communication technologies, numerous recent studies in the field of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest have explored the use of video recordings and real-time video calls to enhance the delivery of first aid. These studies have reported positive outcomes, demonstrating that the accurate implementation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in accordance with established guidelines contributes to improved survival rates. However, several limitations requiring further improvement have also been identified [8,9].

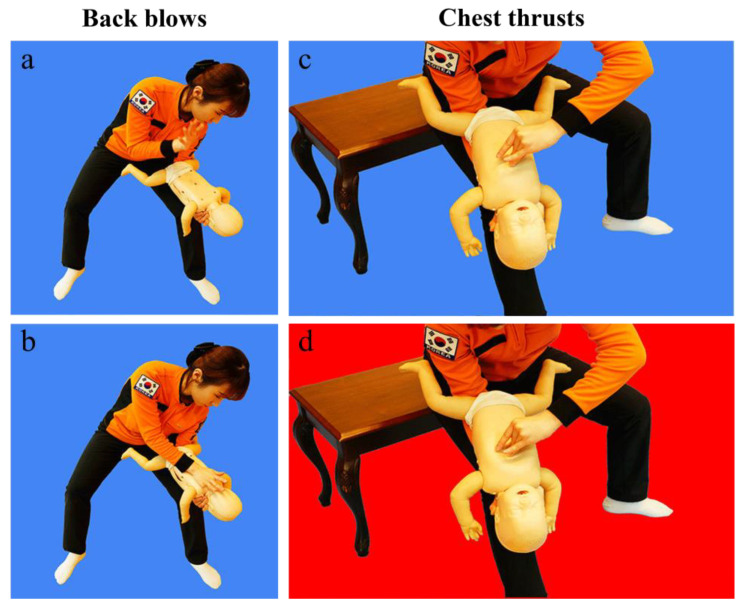

This study aimed to assess the impact of adding a visual aid (Figure 1) to standard auditory instructions provided by dispatchers over the phone for infant FBAO first aid on laypersons’ ability to replicate the standard infant FBAO first-aid position and follow instructions.

Figure 1.

Small-packet animated graphics interchange formats (GIFs). The figure illustrates the sequential phases of the back blow (a,b) and chest thrust (c,d) maneuvers, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a prospective, single-blind, randomized, and simulated study. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline was also followed [10]. The sample sizes were determined using G.power 3.1.9.7. The sample size was determined using a two-tailed test with an effect size (d) of 1.17, alpha of 0.05, and power of 0.95. This required 20 participants per group, totaling 40. The achieved power was 0.95. Eighty participants were randomly assigned to either the auditory group or the audiovisual group, with 40 participants in each group. The participants were blinded to the experiment, with only the instructions to “perform first aid as directed”. The participants were instructed to perform first aid for airway obstruction on an infant manikin (Baby Anne, Laerdal) in a given FBAO situation. Using their smartphones, the participants reported to a researcher acting as a dispatcher and followed the instructions provided by a research facilitator based on the 2020 American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Guidelines. The research environment simulated an infant FBAO situation outside a hospital with activated EMS. The researcher guided the participants remotely using only a smartphone following the infant FBAO protocol from the Gangwon-do Fire Headquarters situation room (Appendix A).

2.2. Selection of Participants

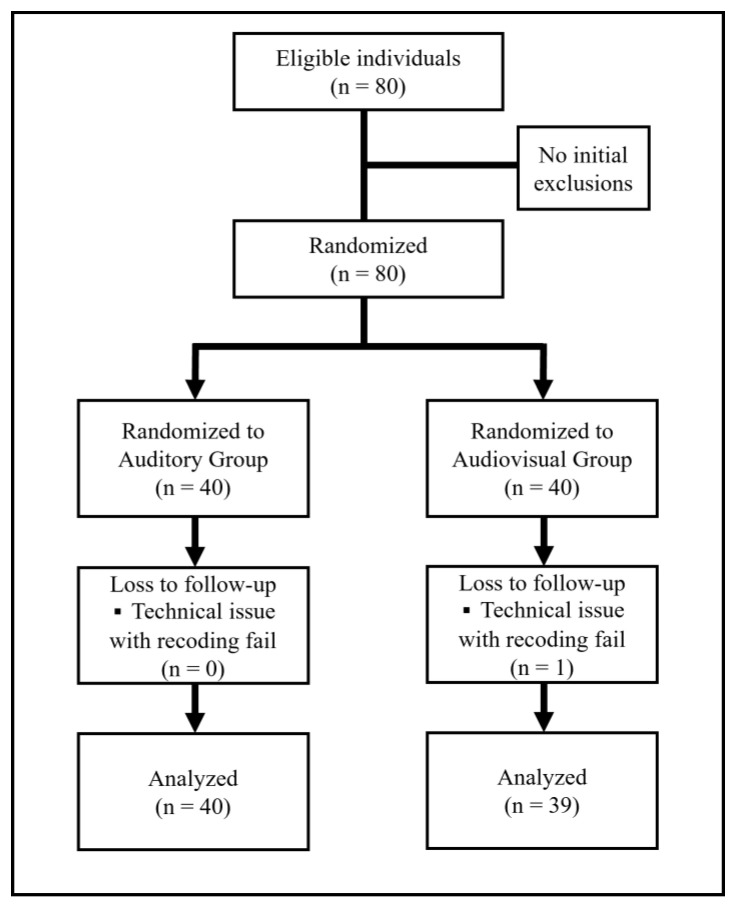

The study included 80 adult participants aged 19 to 65 who had not received cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and airway obstruction first-aid training in the past two years and voluntarily participated in this study. Children and elderly people inexperienced in using smartphones and those with disabilities that prevented them from performing infant FBAO first aid were excluded (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Participants were recruited through a public announcement. Before participation, the researcher explained the study in detail for approximately 30 min, and written informed consent was obtained.

2.3. Interventions

The two groups participated in the study under identical conditions, including the use of the same place and the same infant manikin. For the auditory group, the researcher delivered first-aid instructions solely through audio. In contrast, for the audiovisual group, the researcher sent a “visualized simple converted image” to the participants’ smartphones along with audio instructions on administering first aid. The “visualized simple converted image” was created in collaboration with the Gangwon-do Fire Department, Republic of Korea, in consultation with the authors. It consists of a series of two standardized infant FBAO first-aid images that create a dynamic, moving effect (Figure 1).

2.4. Randomization

The participants were unaware of the group they belonged until they entered the room, where they were randomly assigned to a group via a paper lottery. Paper slips representing each allocation group (auditory and audiovisual) were prepared in the same size and shape and thoroughly mixed to ensure equal opportunity. To ensure confidentiality, the lottery was conducted using a sealed, opaque container. Neither the researchers nor the participants knew the allocations until assignment. Randomization was performed by an independent research assistant. After the lottery, the participants opened the sealed envelope to check their assigned group.

2.5. Outcomes

The main study outcome was the scores for Instruction Performance (IP). The entire process was recorded using two video cameras, one positioned in front and one from the side. After the simulation experiment was completed, two emergency physicians reviewed the videos to assess the adequacy of first aid and IP. First-aid appropriateness was assessed based on 10 items, while IP was quantified as the “IP score” by summing up the scores of all items, with 1 point given for each appropriateness item. The time from when the dispatcher started instructing the participant on performing first aid to the participant executing the first back blow was defined as “time to the first back blow”. Additionally, the time from the start of instruction on performing first aid to the completion of five back blows and five chest thrusts was defined as “time to finish the first cycle” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of first-aid performance for infant choking.

| Assessment items | Definitions | |

|---|---|---|

| Adequacy of | ① Infant position | Prone for back blow and supine for chest thrust |

| ② Supporting arm posture | Alignment of the supporting arm and infant body axis | |

| ③ Hand posture of the supporting arm | Adequacy of infant chin support | |

| ④ Head tilt | The head is located lower than the body | |

| ⑤ Location of back blows | Upper back above the axillary line | |

| ⑥ Number of back blows | Back blow five times | |

| ⑦ Hand part for back blows | Use the heel of hand | |

| ⑧ Location of chest thrusts | The lower half of the sternum | |

| ⑨ Number of chest thrusts | Chest thrust five times | |

| ⑩ Repeating two maneuvers | Repeat the back blow and chest thrust maneuvers | |

| Instruction Performance score | Sum of ①–⑩ | |

| Time to first back blow | Time from dispatcher instruction to the first back blow | |

| Time to finish the first cycle (five back blows and five chest thrusts) | Time from dispatcher instruction to the fifth chest thrust | |

| Time from the second to the third cycle | Time from the first back blow of the second cycle to when the participant finished the fifth chest thrust of the third cycle | |

| Time to finish the third cycle | Time from dispatcher instruction to the fifth chest thrust of the third cycle | |

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistics version 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using the t-test and chi-squared test.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

One participant in the audiovisual group was unable to be evaluated due to problems with the recorded video and was excluded from the study. Finally, the study included 40 and 39 participants in the auditory and audiovisual groups, respectively (Figure 2). In the auditory group, the mean age was 30.43 ± 3.11 years, there were 19 males, 15 participants had relevant training before, and the mean time since training was 4.88 ± 2.30 years. In the audiovisual group, the mean age was 30.46 ± 2.49 years, there were 13 males, 20 participants had relevant training before, and the mean time since training was 5.37 ± 2.41 years. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of sex, age, or prior training experience (Table 2).

Table 2.

General characteristics of the study participants compared.

| Auditory Group (n = 40) |

Audiovisual Group (n = 39) |

Total (n = 79) |

p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 19 (47.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | 32 (40.5%) | 0.171 |

| Female | 21 (52.5%) | 26 (66.7%) | 47 (59.5%) | ||

| Age | 30.43 ± 3.11 | 30.50 ± 2.47 | 30.46 ± 2.79 | 0.787 | |

| Prior training | No | 25 (62.5%) | 19 (48.7%) | 44 (55.7%) | 0.178 |

| Yes | 15 (37.5%) | 21 (53.8%) | 36 (45.6%) | ||

| Prior training timing (year) | 4.88 ± 2.30 | 5.67 ± 2.46 | 5.32 ± 2.39 | 0.310 | |

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Auditory and Audiovisual Groups

Regarding the adequacy of first aid, the “infant position”, “supporting arm posture”, “head tilt”, and “hand part for back blows” were more adequate in the audiovisual group than in the auditory group. The “number of chest thrusts” was more adequate in the auditory group than in the audiovisual group. The audiovisual group had higher IP scores than the auditory group [8.15 ± 1.31 vs. 6.13 ± 2.27, p < 0.001]. Regarding the time required for first aid, no significant differences were observed in all items between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of auditory and audiovisual groups of first-aid performance for infant choking.

| Assessment Items | Auditory (n = 40) |

Audiovisual (n = 39) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequacy of | ① Infant position | 31 (77.5%) | 39 (100.0%) | 0.002 |

| ② Supporting arm posture | 12 (30.0%) | 27 (69.2%) | <0.001 | |

| ③ Hand posture of the supporting arm | 10 (25.0%) | 15 (38.5%) | 0.233 | |

| ④ Head tilt | 12 (30.0%) | 39 (100.0%) | <0.001 | |

| ⑤ Location of back blows | 22 (55.0%) | 31 (79.5%) | 0.138 | |

| ⑥ Number of back blows | 29 (72.5%) | 34 (87.2%) | 0.105 | |

| ⑦ Hand part for back blows | 19 (47.5%) | 31 (79.5%) | 0.009 | |

| ⑧ Location of chest thrusts | 32 (80.0%) | 30 (76.9%) | 0.136 | |

| ⑨ Number of chest thrusts | 40 (100.0%) | 34 (87.2%) | 0.026 | |

| ⑩ Repeating two maneuvers | 36 (90.0%) | 38 (97.4%) | 0.175 | |

| Instruction Performance score | 6.13 ± 2.27 | 8.15 ± 1.31 | <0.001 | |

| Time to first back blow | 52.88 ± 12.56 | 53.05 ± 10.95 | 0.498 | |

| Time to finish the first cycle | 77.38 ± 14.03 | 112.58 ± 144.38 | 0.118 | |

| Time from the second to the third cycle * | 19.31 ± 4.40 | 22.29 ± 4.64 | 0.332 | |

| Time to finish the third cycle * | 112.53 ± 17.99 | 128.76 ± 17.64 | 0.332 | |

* The analysis was conducted on the auditory (n = 36) and audiovisual (n = 38) groups, excluding cases in which the two maneuvers were not performed repeatedly.

3.3. Analysis According to Prior Relevant Training Experience

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of the Auditory and Audiovisual Groups with Prior Relevant Training

Regarding the adequacy of first aid, the “head tilt” and “number of back blows” were more adequate in the audiovisual group than in the auditory group. However, IP scores did not differ significantly between the auditory and audiovisual groups. Regarding the time required for first aid, no significant differences were observed in all items between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of auditory and audiovisual groups of first-aid performance for infant choking by prior training experience.

| Prior Training Group | No Prior Training Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory (n = 15) |

Audiovisual (n = 20) |

p-Value | Auditory (n = 25) |

Audiovisual (n = 19) |

p-Value | ||

| Adequacy of | ① Infant position | 13 (86.7%) | 20 (100.0%) | 0.093 | 18 (72.0%) | 19 (100.0%) | 0.012 |

| ② Supporting arm posture | 8 (53.3%) | 12 (60.0%) | 0.693 | 4 (16.0%) | 15 (78.9%) | <0.001 | |

| ③ Hand posture of the supporting arm | 6 (40.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 0.668 | 4 (16.0%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.054 | |

| ④ Head tilt | 5 (33.3%) | 20 (100.0%) | <0.001 | 7 (28.0%) | 19 (100.0%) | <0.001 | |

| ⑤ Location of back blows | 11 (73.3%) | 16 (80.0%) | 0.621 | 11 (44.0%) | 15 (78.9%) | 0.079 | |

| ⑥ Number of back blows | 9 (60.0%) | 18 (90.0%) | 0.036 | 20 (80.0%) | 16 (84.2%) | 0.720 | |

| ⑦ Hand part for back blows | 10 (66.7%) | 18 (90.0%) | 0.088 | 9 (36.0%) | 13 (68.4%) | 0.059 | |

| ⑧ Location of chest thrusts | 14 (93.3%) | 17 (85.0%) | 0.129 | 18 (72.0%) | 13 (68.4%) | 0.298 | |

| ⑨ Number of chest thrusts | 15 (100.0%) | 18 (90.0%) | 0.207 | 25 (100.0%) | 16 (84.2%) | 0.040 | |

| ⑩ Repeating two maneuvers | 13 (86.7%) | 19 (95.0%) | 0.383 | 23 (92.0%) | 19 (100.0%) | 0.207 | |

| Instruction Performance score | 6.93 ± 2.15 | 8.25 ± 1.33 | 0.263 | 5.63 ± 2.24 | 8.05 ± 1.31 | 0.014 | |

| Time to the first back blow | 50.13 ± 9.50 | 52.85 ± 12.10 | 0.559 | 54.52 ± 14.01 | 53.26 ± 9.95 | 0.256 | |

| Time to finish the first cycle | 74.73 ± 11.48 | 132.29 ± 199.14 | 0.128 | 78.96 ± 15.36 | 9.079 ± 12.32 | 0.670 | |

| Time from the second to the third cycle * | 19.38 ± 3.89 | 22.53 ± 4.95 | 0.490 | 19.26 ± 4.75 | 22.05 ± 4.43 | 0.492 | |

| Time to finish the third cycle * | 111.00 ± 17.45 | 128.58 ± 20.86 | 0.285 | 113.96 ± 18.52 | 128.95 ± 14.30 | 0.755 | |

* The analysis was conducted on only those participants who properly performed “Repeating two maneuvers (⑩)”.

3.3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Auditory and Audiovisual Groups Without Prior Relevant Training

Regarding the adequacy of first aid, the “infant position”, “supporting arm posture”, and “head tilt” were more adequate in the audiovisual group than in the auditory group. The “number of chest thrusts” was more adequate in the auditory group than in the audiovisual group. The audiovisual group had higher IP scores than the auditory group [8.05 ± 1.31 vs. 5.63 ± 2.24, p = 0.014]. Regarding the time required for first aid, no significant differences were observed in all items between the two groups (Table 4).

3.4. Analysis According to Sex

3.4.1. Comparative Analysis of the Auditory and Audiovisual Groups Among Male Participants

Regarding the adequacy of first aid, the “head tilt” and “number of back blows” were more appropriate in the audiovisual group than in the auditory group. The audiovisual group had higher IP scores than the auditory group [8.23 ± 1.48 vs. 6.63 ± 2.36, p = 0.039]. Regarding the time required for first aid, no significant differences were observed in any items between the two groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of auditory and audiovisual groups of first-aid performance for infant choking by sex.

| Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory (n = 19) |

Audiovisual (n = 13) |

p-Value | Auditory (n = 21) |

Audiovisual (n = 26) |

p-Value | ||

| Adequacy of | ① Infant position | 15 (78.9%) | 13 (100.0%) | 0.081 | 16 (76.2%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.008 |

| ② Supporting arm posture | 8 (42.1%) | 7 (53.8%) | 0.529 | 4 (19.0%) | 20 (76.9%) | <0.001 | |

| ③ Hand posture of the supporting arm | 6 (31.6%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0.419 | 4 (19.0%) | 9 (34.6%) | 0.294 | |

| ④ Head tilt | 10 (52.6%) | 13 (100.0%) | 0.002 | 2 (9.5%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.001 | |

| ⑤ Location of back blows | 11 (61.1%) | 11 (84.6%) | 0.165 | 11 (61.1%) | 20 (74.1%) | 0.374 | |

| ⑥ Number of back blows | 14 (73.7%) | 12 (92.3%) | 0 .005 | 15 (71.4%) | 22 (84.6%) | 0.282 | |

| ⑦ Hand part for back blows | 11 (61.1%) | 11 (84.6%) | 0.165 | 8 (40.0%) | 20 (76.9%) | 0. 029 | |

| ⑧ Location of chest thrusts | 15 (93.8%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0.840 | 17 (89.5%) | 19 (73.1%) | 0.264 | |

| ⑨ Number of chest thrusts | 19 (100.0%) | 11 (84.6%) | 0.082 | 21 (100.0%) | 23 (88.5%) | 0.112 | |

| ⑩ Repeating two maneuvers | 17 (89.5%) | 12 (92.3%) | 0.840 | 19 (90.5%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.112 | |

| Instruction Performance score | 6.63 ± 2.36 | 8.23 ± 1.48 | 0.039 | 5.65 ± 2.13 | 8.12 ± 1.24 | 0.009 | |

| Time to the first back blow | 53.68 ± 15.11 | 53.31 ± 9.54 | 0.294 | 52.14 ± 10.06 | 52.92 ± 11.77 | 0.830 | |

| Time to finish the first cycle | 78.79 ± 17.10 | 93.38 ± 10.68 | 0.304 | 76.10 ± 10.82 | 121.81 ± 17.91 | 0.124 | |

| Time from the second to the third cycle * | 19.58 ± 3.63 | 24.00 ± 4.64 | 0.163 | 18.05 ± 5.36 | 21.35 ± 4.39 | 0.926 | |

| Time to finish the third cycle * | 115.24 ± 21.60 | 134.75 ± 15.91 | 0.311 | 110.11 ± 14.19 | 126.00 ± 18.0 | 0.301 | |

* The analysis was conducted on only those participants who properly performed “Repeating two maneuvers (⑩)”.

3.4.2. Comparative Analysis of the Auditory and Audiovisual Groups Among Female Participants

Regarding the adequacy of first aid, the “infant position”, “supporting arm posture”, “head tilt”, and “hand part for back blows” were more adequate in the audiovisual group than in the auditory group. The audiovisual group had higher IP scores than the auditory group [8.12 ± 1.24 vs. 5.65 ± 2.13, p = 0.009]. Regarding the time required for first aid, no significant differences were observed in any items between the two groups (Table 5).

4. Discussion

FBAO is a leading cause of infant mortality, requiring prompt and appropriate first aid within 4 to 6 min to prevent serious consequences and potential mortality [11]. Effective interventions for FBAO are crucial in this time-sensitive emergency. Visual aids, such as images and illustrations, can help convey complex medical information and enhance communication [12]. And the adoption of video formats significantly augments comprehension compared to more traditional methods [7]. Our previous study demonstrated that using simple visual images, along with auditory guidance during dispatcher-assisted CPR, enhances bystander CPR performance [13]. This study investigated the application of these visual aids in infant FBAO first aid and found a significant improvement in performance (p < 0.001).

The treatment for infant FBAO entails the rescuer placing their forearm on their thigh, positioning the infant face-down on the forearm with the head lower than the chest, ensuring a straight neck, holding the chin, and administering five back blows between the shoulder blades. Then, the rescuer turns the baby’s face upward and applies pressure to the lower half of the sternum with two fingers five times, repeating these steps until the foreign body is expelled. In the event that the infant loses consciousness, infant CPR should be initiated as recommended [2,5].

The study revealed that the audiovisual group outperformed the auditory group in assessing the appropriateness of 10 infant FBAO first-aid items, particularly infant positioning, rescuer arm support posture, infant head tilting, and hand position for back blows. In the audiovisual guidance, participants successfully positioned the infant manikin to prevent it from slipping off their forearm. However, the proportion of correct hand positioning (chin support) was the lowest among participants in the audiovisual group, with no significant difference compared to the auditory group. This may be due to the difficulty of interpreting proper chin support from a small smartphone image.

Positioning the infant’s head lower than the body is emphasized in airway obstruction treatment guidelines because gravity aids in removing foreign objects. Research indicates that prone or head-down postures can help clear foreign bodies from the airway in both children and adults due to the effect of gravity [14,15]. In the audiovisual group, all participants correctly performed the infant head tilt maneuver, while only 30% of participants in the auditory-only group did so. Interestingly, the chest compression frequency was significantly lower in the audiovisual group compared to the auditory-only group (p = 0.03) because the participants in the audiovisual group performed more chest compressions than recommended. The process involved the transmission of two animated GIF images: one for back blows and another for chest compressions. After completing one cycle of audiovisual guidance, the participants were instructed to repeat the cycle until the foreign body was expelled. However, because the chest compression GIF remained visible on their smartphones, some participants continued to perform chest compressions instead of switching to back blows. This behavior was more pronounced in the group with no prior training. While a meta-analysis reported that videos could enhance CPR quality, concerns were raised regarding delays in initiating the first chest compression [16]. However, in this study, the use of animated GIFs for airway obstruction emergency treatment did not cause a significant delay in starting the first back blow between the audiovisual and auditory-only groups. The total execution time for three cycles was not significantly different between the two groups, suggesting that the images used in this study, consisting of only two images and transmitted quickly due to their small file size, allowed the users to understand the procedures intuitively without causing delays.

According to the most recent systematic review on this topic, while first aid is crucial for removing foreign objects, it can also pose a risk of injuries such as gastric rupture, splenic laceration, and pulmonary contusion in adults and children [17]. Infant first aid for FBAO is a complex procedure that involves constant manipulation of the infant’s position, making it challenging for dispatchers to convey verbally and for laypeople to understand and perform correctly [3,4]. Communication errors may contribute to these complications. Despite the simulation study being conducted in a controlled and quiet setting, video analysis revealed discrepancies in the auditory-only group. Three participants incorrectly used two fingers to press on the nipples instead of the center of the chest during chest compressions. Additionally, one participant applied pressure on the back with two fingers, while another used their elbow, all of which deviated from the prescribed instructions and constituted improper first aid practices. A Danish study that combined audio recordings of dispatcher-assisted CPR with closed-circuit television footage during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest scenarios revealed that verbal instructions given to bystanders are often misunderstood and can be unclear [18]. The challenge is compounded by physical, emotional, and knowledge barriers faced by lay responders in real-world emergencies [19,20]. A multicenter observational study in Japan found that proper first aid for airway obstruction was performed by bystanders only half of the time [21]. A literature review study has shown that biological and psychological stress experienced during CPR can lead to decreased performance ability [22]. Similar dynamics can apply in situations of infant airway obstruction, where parents or guardians, who are often the first responders, may experience significant mental and physical stress, hindering their ability to perform emergency procedures effectively. Numerous studies have reported that parents or guardians often lack the necessary emergency first-aid knowledge to handle crisis situations [23,24]. This study did not consider variables such as the participants’ occupations, education levels, or cultural backgrounds; however, in the comparison of sex differences, the audiovisual group significantly outperformed the auditory group in terms of IP scores. The female group demonstrated a higher number of significant performance scores than the male group (4 of 10 items vs. 2 of 10). Considering that in cases of infant FBAO, the primary witnesses are often parents, particularly young mothers, audiovisual aids could prove invaluable in facilitating effective first aid. Our findings suggest that individuals with no prior training achieved significantly higher compliance scores in the audiovisual group compared to other groups, indicating that simple animated images (GIFs) can effectively convey emergency first-aid knowledge to the general public.

With the global rise in smartphone penetration and advances in communication technology, there has been a surge in research utilizing video technology for CPR emergency interventions [8,25] However, research on applying such technology for airway obstruction first aid has been notably limited. Recent simulation studies in Japan that explored the use of video calls for infant airway obstruction first aid reported a 24% failure rate in video calls, highlighting various challenges in effectively employing real-time video during emergencies [3]. The transition from audio to video assistance requires the cooperation of the reporter, and issues related to the communication environment, communication costs, and exposure of personal information can pose significant barriers [9,26,27]. To address these challenges, researchers have developed text-transmitted animated GIF images with small file sizes, aiming to minimize delays in transmission and enhance usability. Therefore, using these GIFs during the EMS phase could offer cost-effective guidance for airway obstruction emergencies, regardless of the diverse communication environments worldwide.

As the proverb goes, “A picture paints a thousand words”, and visual communication is often more readily understood, particularly in emergencies. The authors developed small-packet animated GIFs to address communication barriers in the EMS phase, aiming to enhance the quality of emergency care for time-sensitive conditions and offer practical assistance in real-life situations. The issues highlighted in this study, such as visual readability and screen transitions, will be addressed systematically. Future research should focus on incorporating animated GIF images into real infant FBAO first-aid scenarios to assess their effectiveness.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the nature of simulation experiments, replicating real-world conditions outside of a hospital setting is challenging. Second, as this was a manikin-based simulation study, the actual effectiveness of using animated GIF images on real airway obstruction patients could not be assessed. Therefore, evaluating real-life outcomes, such as long-term follow-up, survival rates to discharge, or neurological outcomes, to assess the quality of the intervention was not possible. Third, the study participants were predominantly young and familiar with smartphones, which may limit the generalizability of the results to older age groups less accustomed to smartphones. Lastly, although it was a randomized controlled trial, blinding the evaluators was not feasible due to the nature of the study.

5. Conclusions

Simple animated GIFs have been developed and implemented to improve the quality of infant FBAO first aid in this study. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that combining simple animated images with auditory instructions can improve first-aid performance in groups without prior training experience.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FBAO | Foreign body airway obstruction |

| IP | Instruction Performance |

| GIFs | Graphics interchange formats |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Protocol for auditory and audiovisual groups in first aid of airway obstruction for infants.

| Auditory group |

|

| Audiovisual group |

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; methodology, T.O.; software, J.C.; validation, H.C. and J.C.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, G.Y.; resources, T.O.; data curation, G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O.; writing—review and editing, T.L.; visualization, T.L.; supervision, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangwon National University Hospital (KNUH-A-2021-01-002-003) on 22 July 2022 and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the experiment began.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Igarashi Y., Norii T., Sung-Ho K., Nagata S., Yoshino Y., Hamaguchi T., Nagaosa R., Nakao S., Tagami T., Yokobori S. Airway obstruction time and outcomes in patients with foreign body airway obstruction: Multicenter observational choking investigation. Acute Med. Surg. 2022;9:e741. doi: 10.1002/ams2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topjian A.A., Raymond T.T., Atkins D., Chan M., Duff J.P., Joyner B.L., Jr., Lasa J.J., Lavonas E.J., Levy A., Mahgoub M., et al. Part 4: Pediatric basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S469–S523. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igarashi Y., Suzuki K., Norii T., Motomura T., Yoshino Y., Kitagoya Y., Ogawa S., Yokobori S., Yokota H. Do video calls improve dispatcher-assisted first aid for infants with foreign body airway obstruction? A randomized controlled trial/simulation study. J. Nippon. Med. Sch. 2022;89:526–532. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldridge E.S., Perera N., Ball S., Birnie T., Morgan A., Whiteside A., Bray J., Finn J. Barriers to CPR initiation and continuation during the emergency call relating to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A descriptive cohort study. Resuscitation. 2024;195:110104. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.110104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duckett S.A., Bartman M., Roten R.A. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2025. [(accessed on 15 April 2025)]. Choking. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499941/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieliński J.R., Huntley R., Dunne C.L., Timler D., Nadolny K., Jaskiewicz F. Do We Actually Help Choking Children? The Quality of Evidence on the Effectiveness and Safety of First Aid Rescue Manoeuvres: A Narrative Review. Medicina. 2024;60:1827. doi: 10.3390/medicina60111827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galmarini E., Marciano L., Schulz P.J. The effectiveness of visual-based interventions on health literacy in health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024;24:718. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11138-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielski K., Böttiger B.W., Pruc M., Gasecka A., Sieminski M., Jaguszewski M.J., Smereka J., Gilis-Malinowska N., Peacock F.W., Szarpak L. Outcomes of audio-instructed and video-instructed dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022;54:464–471. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2032314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H.S., You K., Jeon J.P., Kim C., Kim S. The effect of video-instructed versus audio-instructed dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation on patient outcomes following out of hospital cardiac arrest in Seoul. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:15555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butcher N.J., Monsour A., Mew E.J., Chan A.-W., Moher D., Mayo-Wilson E., Terwee C.B., Chee-A-Tow A., Baba A., Gavin F., et al. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA. 2022;328:2252–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekim A., Altun A. Foreign body aspirations in childhood: A retrospective review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023;72:e174–e178. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2023.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woloshin S., Yang Y., Fischhoff B. Communicating health information with visual displays. Nat. Med. 2023;29:1085–1091. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohk T., Cho J., Yang G., Ahn M., Lee S., Kim W., Lee T. Effectiveness of a dispatcher-assisted CPR using an animated image: Simulation study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024;78:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2024.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luczak A. Effect of body position on relieve of foreign body from the airway. AIMS Public Health. 2019;6:154–159. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2019.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resuscitation Council UK Paediatric Basic Life Support Guidelines. [(accessed on 12 April 2025)]. Available online: https://www.resus.org.uk/library/2021-resuscitation-guidelines/paediatric-basic-life-support-guidelines.

- 16.Pan D.F., Li Z.J., Ji X.Z., Yang L.T., Liang P.F. Video-assisted bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation improves the quality of chest compressions during simulated cardiac arrests: A systemic review and meta-analysis. World J. Clin. Cases. 2022;10:11442–11453. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couper K., Abu Hassan A., Ohri V., Patterson E., Tang H.T., Bingham R., Olasveengen T., Perkins G.D. Removal of foreign body airway obstruction: A systematic review of interventions. Resuscitation. 2020;156:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohnstedt-Pedersen N.H., Linderoth G., Helios B., Christensen H.C., Thomsen B.K., Bekker L., Gram J.K.B., Vaeggemose U., Gehrt T.B. Medical dispatchers’ experience with live video during emergency calls: A national questionnaire study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024;24:1442. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11939-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama T., Scapigliati A., Pellis T., Greif R., Iwami T. Willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A scoping review. Resusc. Plus. 2020;4:100043. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2020.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldridge E.S., Perera N., Ball S., Finn J., Bray J. A scoping review to determine the barriers and facilitators to initiation and performance of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation during emergency calls. Resusc. Plus. 2022;11:100290. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2022.100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norii T., Igarashi Y., Yoshino Y., Nakao S., Yang M., Albright D., Sklar D.P., Crandall C. The effects of bystander interventions for foreign body airway obstruction on survival and neurological outcomes: Findings of the MOCHI registry. Resuscitation. 2024;199:110198. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2024.110198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincent A., Semmer N.K., Becker C., Beck K., Tschan F., Bobst C., Schuetz P., Marsch S., Hunziker S. Does stress influence the performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A narrative review of the literature. J. Crit. Care. 2021;63:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X., Miao L., Zhu J., Liang J., Dai L., Li X., Li Q., Rao R., Yuan C., Wang Y., et al. Social and environmental risk factors for unintentional suffocation among infants in China: A descriptive analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:465. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02925-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begović I., Štefanović I.M., Vrsalović R., Geber G., Kereković E., Lučev T., Baudoin T. Parental awareness of the dangers of foreign body inhalation in children. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022;61((Suppl. 4)):26–33. doi: 10.20471/acc.2022.61.s4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen K.Y., Ko Y.C., Hsieh M.J., Chiang W.C., Ma M.H.M. Interventions to improve the quality of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park D.H., Park G.J., Kim Y.M., Chai H.S., Kim S.C., Kim H., Lee S.W. Barriers to successful dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Korea. Resusc. Plus. 2024;19:100725. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnusson C., Ollis L., Munro S., Maben J., Coe A., Fitzgerald O., Taylor C. Video livestreaming from medical emergency callers’ smartphones to emergency medical dispatch centres: A scoping review of current uses, opportunities, and challenges. BMC Emerg. Med. 2024;24:99. doi: 10.1186/s12873-024-01015-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.