Abstract

Introduction

Omaveloxolone, the only approved medication for Friedreich ataxia (FRDA), is an NRF2 activator available since July 2023. We examined safety monitoring of omaveloxolone administration over the first 12 months of administration.

Methods

We recorded baseline and follow-up serum transaminase, albumin, total bilirubin, cholesterol, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) values as well as adverse events over 1 year in patients initiating commercial omaveloxolone therapy.

Results

Access to omaveloxolone was obtained in 236 of individuals for whom it was prescribed. Side effects were noted in 23.8% of patient with the most common being gastrointestinal upset, headache, and fatigue baseline. Twenty-one patients (8.9%) permanently discontinued the drug during the first year. Over the first year, 56.6% of patients had at least one transaminase value above the upper limit of normal at some point. Elevations largely occurred over the first 3 months of therapy, and after 6 months of dosing, only 8.6% of patients had elevations in transaminases. Elevations were generally < 3 × the upper limit of normal and decreased with temporary pausing of the drug or dose reduction. Few changes were noted in albumin or bilirubin, and such changes did not parallel changes in transaminases, suggesting they are independent events. BNP values were generally unchanged throughout the year, and no systematic changes in blood counts were noted. Cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) elevations were mild.

Conclusions

Most patients with FRDA eventually had access to omaveloxolone, and it was generally well tolerated. Side effects were modest, and, overall, most patients remained on the drug. Abnormalities in serum liver function tests were limited to transaminases, resolved with dose pausing or reduction, and diminished markedly over time. Thus, the safety features of omaveloxolone after administration largely resemble the favorable features noted during clinical trials.

Keywords: Brain natriuretic peptide, Mitochondria transaminase, Movement disorder, Omaveloxolone

Key Summary Points

| Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) is characterized by progressive gait and limb ataxia, scoliosis, dysarthria, visual loss, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| The only FDA-approved medication for patients ≥ 16 years old with FRDA is omaveloxolone |

| Omaveloxolone is an NRF2 stabilizer shown to improve mFARS (modified Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale) scores in clinical trials and has been commercially available since July 2023 |

| We followed patients over the first year of commercial availability, tracking laboratory values and reported adverse events |

| The clinical findings after the first year of treatment are similar to the findings in the MOXIe clinical trials |

Introduction

Friedreich ataxia (FRDA), the most common hereditary ataxia, is characterized by progressive gait and limb ataxia, scoliosis, dysarthria, visual loss, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [1–3]. The age of onset is usually within the first 2 decades of life, and individuals are wheelchair-bound within 10–15 years of disease onset [4]; cardiomyopathy-associated heart failure is the main cause of mortality [5]. FRDA is usually (96%) caused by biallelic expanded guanine-adenine-adenine (GAA) trinucleotide repeats in intron 1 of the FXN gene. Such expanded GAA repeats repress FXN expression leading to reduced frataxin protein levels. Frataxin is targeted to mitochondria, where it facilitates biosynthesis of iron–sulfur clusters (ISCs) [6–8] and energy production in the cell [9, 10].

While definitive therapy probably requires restoration of frataxin levels, a variety of approaches targeted to reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction have reached clinical trials, with omaveloxolone being approved by the FDA in 2023 [11–16]. Omaveloxolone stabilizes NRF2, a transcription factor controlling the endogenous response to oxidative stress; NRF2 is paradoxically downregulated in FRDA [17–20]. In the MOXIe clinical trials of patients with FRDA 16 to 40 years of age, omaveloxolone demonstrated a biphasic concentration response curve, with maximal benefit occurring at 160 mg per day, leading to a dosing in pivotal studies of 150 mg per day. At this dose, omaveloxolone improved mFARS scores, the most commonly used measure for assessment of neurologic function in FRDA, at 1 year with benefit persisting during an open label extension for at least 3 years [11–15, 21]. The drug was also safe and well tolerated in the MOXIe study, but its dosing is complicated by interactions with strong CYP4A3 inhibitors. CYP4A3 inhibitors increase the metabolism of omaveloxolone, requiring a reduction of dosage to prevent overmedicating.

Based on these data, omaveloxolone was approved for treatment of patients with FRDA ≥ 16 years old with no other restrictions. Recommended monitoring of omaveloxolone treatment includes yearly BNP and cholesterol levels as well as hepatic function testing at baseline and months 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 after starting therapy. Here, we report on the safety and tolerability of omaveloxolone given clinically for 1 year.

Methods

Patients

Procedures were approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Institutional review board as a component of the long-running FRDA natural history study FACOMS and its successor (UNIFAI) (CHOP IRB #2609). Subjects provided informed consent through this study and were initially identified as those followed at CHOP in the natural history study. Data were extracted from their study visits to evaluate medical history, laboratory testing, and adverse events.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved through the CHOP IRB as study 2609 and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Data Collection

We extracted the start date, baseline laboratory values, and medication interactions for each patient. Laboratory values included lipid panels (total cholesterol and LDL) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), at baseline visits and hepatic function testing at months 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after starting omaveloxolone, focusing on alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, and total bilirubin levels. For patients previously enrolled in the clinical trial of omaveloxolone, only baseline and 12-month laboratory values were extracted.

Dosing

All patients were initially dosed based on the clinical recommendation of 150 mg/ day (three 50 mg pills), except those on chronic CYP3A4 inhibitors (most commonly diltiazem and verapamil). Patients on these inhibitors were dosed at 100 mg/ day (two pills) to achieve the presumptively similar blood levels [22].

For those subjects followed clinically at CHOP, omaveloxolone dose was reduced in response to elevated transaminase values as follows: Patients continued dosing at the same dose if ALT values were < 2 × the ULN. If the value for ALT was > 3 × the upper limit normal (ULN), the patient was instructed to discontinue omaveloxolone for 2 weeks and repeat laboratory testing. If the repeat testing showed ALT levels < 3 × normal, the patient was restarted at 50 mg less than their previous dose. Once a patient was had stable ALT levels under 2 × ULN based on serial testing (typically each month), patients could increase back to their full dosage. If ALT was 2–2.9 × ULN, patients continued the same dosing, but hepatic function values were reevaluated in 2 weeks to confirm stable ALT levels. The average ALT upper limit of normal (ULN) was 41.3 U/l but varied depending on patient demographics and site of assessment. The mean value for each test is provided for reference.

For patients who experienced dose reduction due to ALT values or other side effects, dosing was slowly returned to their original dosing regimen if transaminase values remained < 3 × normal.

Data Analysis

Data were calculated using Stata version 18 (College Station, TX) or Graphpad (www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs). For analysis of proportions of elevated values, ULN was presumed to be Gaussian in distribution and thus represent two standard deviations greater than mean and analyzed by chi-square tests. For analysis of means, samples were compared to the ULN by one-sample t-tests.

Results

Demographics

Two hundred ninety-two patients were identified for the study; 236 were prescribed omaveloxolone by a member of the CHOP neurology division (and participated in FACOMS/UNIFAI at CHOP), with 56 further patients utilizing outside prescribers (obtaining other care or participating in FACOMS at CHOP). At CHOP, the average age for starting treatment was 31.8 and for non-CHOP was 28.8 years. The average disease duration was 17.8 (CHOP) and 18.9 (non-CHOP). The average age of onset was 13.9 (CHOP) and 10.3 (non-CHOP). The average GAA1 repeat length was 631.7 (CHOP) and 720 (non-CHOP). At CHOP, 44.4% of patients were male and 55.5% were female. Patients prescribed outside of CHOP were 50% male and 50% female (Table 1). Forty individuals had participated in the MOXIe trials, 33 of whom transitioned directly from the study to commercial drug. The remaining seven patients participated in MOXIe but had terminated participation before starting commercial medication. Further analysis concentrated on the individuals for whom omaveloxolone was prescribed at CHOP as more detailed information was available.

Table 1.

Demographics of the cohort

| Parameter | CHOP | Non-CHOP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean + SD | n | n | ||

| Age at start of treatment (years) | 31.8 ± 13.0 | 207 | 28.8 ± 11.2 | 25 |

| Disease duration (years) | 17.8 ± 9.6 | 201 | 18.9 ± 10.5 | 24 |

| Age of onset (AOO) (years) | 13.9 ± 8.8 | 201 | 10.3 ± 5.8 | 51 |

| GAA1 | 632 ± 235 | 195 | 720 ± 150 | 51 |

| Sex | 44.4% male 55.5% female | 207 |

50% male 50% female |

56 |

Demographics for 207 patients currently taking omaveloxolone at CHOP and 56 patients outside of CHOP. Six CHOP patients had an unknown age of onset and disease duration. Twelve CHOP patients had unknown GAA1 repeats. Five non-CHOP patients had unknown AOO and GAA1 repeats. Thirty-one had unknown age at start of omaveloxolone due to unknown start dates and 32 had unknown disease duration values. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP)

Of the 236 patients prescribed omaveloxolone at CHOP, 207 remained on the drug with most patients (88.4%) having taken omaveloxolone for > 1 year (Table 2). Five patients never obtained approval, and 21 patients discontinued omaveloxolone (Table 2). Patients mainly discontinued omaveloxolone because of reported side effects or were lost to follow-up. Of those treated at CHOP, 22 obtained medication through a patient assistance program, while the patient’s insurance covered omaveloxolone in 214 people.

Table 2.

Duration on omaveloxolone

| Group | n |

|---|---|

| > 12 months | 183 |

| < 12 months | 24 |

| Not started | 3 |

| Denied | 5 |

| Discontinued | 21 |

| Reason for discontinuation: | |

| Adverse effects | 5 |

| Lost to follow-up from centralized pharmacy | 4 |

| Lack of benefit | 3 |

| Deceased (unrelated to omaveloxolone) | 5 |

| High copay | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 |

Two hundred seven patients remained on the drug, and most patients at CHOP stayed on medication after 1 year. Twenty-one patients permanently discontinued for various reasons. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP)

Dosing

The majority of patients prescribed at CHOP reached the maximum dose of 150 mg a day (three 50 mg pills a day); 87.9% of patients have an ideal maximum dose of 150 mg/day, and 12.1% have a maximum dose of 100 mg (2 pills) a day based on interactions with other drugs. Eighty-five percent (176 patients) at CHOP reached 150 mg a day, 14.0% (29 patients) take 100 mg a day, and 1.0% (2 patients) take 50 mg (one pill) a day. Seven patients are currently (at least 12 months after initiation of therapy) taking less than their ideal dose but are actively working towards the maximum ideal dose.

Adverse Events

In the cohort, 63 subjects reported significant adverse events, most commonly matching those noted in the clinical trial (GI disturbances, headache), but a few individuals discontinued drugs because of such events. Some patients had multiple adverse events, almost all of which subsided over the first 3 months (Table 3). Three individuals reported rash, which correlated highly with omaveloxolone administration in one individual. In two of these patients, a dermatologic consultant felt the rash was unrelated after skin biopsy. Of those with rash, two tolerated the drug with minimal skin reaction on rechallenge, while the third had a recurrence and discontinued omaveloxolone permanently. No ongoing side effects were noted in those individuals who had transitioned from the MOXIe study.

Table 3.

Reported adverse events

| Reported adverse events | n |

|---|---|

| GI upset | 35 |

| Fatigue | 7 |

| Headache | 6 |

| Spasms | 5 |

| Stiffness | 3 |

| Rash | 3 |

| Sleep disturbance | 2 |

| Increased progression rate | 2 |

| Drugged feeling | 2 |

| Tremor | 1 |

| Total | 63 |

Sixty-three patients followed reported one or multiple adverse events (AEs) directly or during clinical visits. Most AEs involved GI (gastrointestinal) upset, which subsided within the first 3 months. Other common AEs reported included fatigue and headache

Monitoring of Hepatic Function

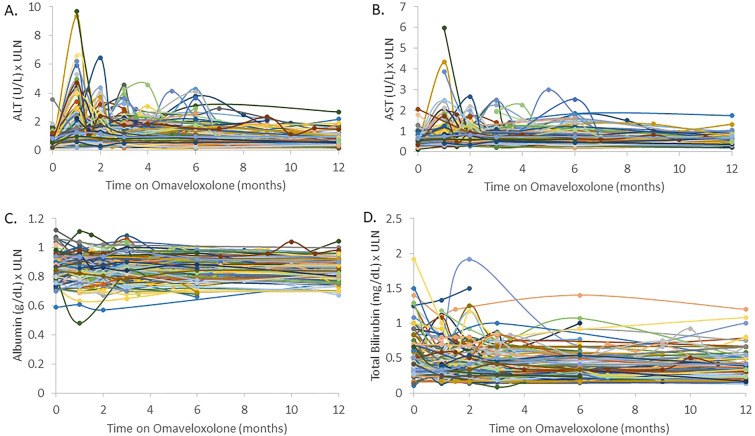

As expected, transaminase elevations (any value greater than the upper limit of normal) occurred in many subjects, with 56.6% of patients having an elevation in transaminases at some point over the 12-month period (p < 0.0001). By 12 months, 16.6% of patients had elevations (p < 0.0001) but none were > 3 × the ULN (Fig. 1A, B). Omaveloxolone did not change albumin levels or total bilirubin levels in a substantial number of patients at any time point. One patient had a significant drop in albumin levels due to pneumonia unrelated to omaveloxolone. Two other significant elevations in bilirubin were explained by unrelated comorbidities (Gilbert’s syndrome and biliary atresia). In those situations, in which albumin or bilirubin changed, it was felt related to comorbidities rather than FRDA or omaveloxolone and did not correlate with changes in transaminases. (Fig. 1C, D). No abnormalities of hepatic function testing were identified in those who had transferred directly from the MOXIe trial.

Fig. 1.

Change in hepatic function testing over time. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (A) compared to the upper limit of normal (ULN) over time on omaveloxolone. ALT levels typically increased after starting omaveloxolone and leveled out after continuation or dose modification. Transaminase elevations (any value greater than the upper limit of normal) occurred in many subjects, with 56.6% of patients having an elevation in transaminases at some point over the 12-month period (p < 0.0001). At 1 month, 55.0% of patients had elevated ALT values with 12.1% above 3 × ULN (both p < 0.0001). At 2 months, 48.9% (p < 0.0001) of patients had elevations with 4.4% (p < 0.003) above 3 × ULN. At 3 months, 39.2% (p < 0.0001) had elevations with 4.4% (p < 0.003) above 3 × ULN. At 6 months, 35.2% (p < 0.0001) had elevations with 3.6% (p < 0.003) above 3 × ULN. At 12 months, 16.6% of patients had elevations (p < 0.0001), but none were > 3 × the ULN. B Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were compared to the upper limit of normal (ULN) over time on omaveloxolone. Increases in AST levels correlated with increases in ALT levels but at lower magnitude. C Albumin levels over time on omaveloxolone. The low outlier (green line) is attributed to a comorbidity (pneumonia) while other outliers appear unrelated as they did not correlate to increases in transaminases. D Total bilirubin levels over time while on omaveloxolone. Two notable outliers had comorbidities that caused increases in bilirubin unrelated to omaveloxolone. One patient with biliary atresia (dark blue line) had increased bilirubin at baseline and discontinued the drug because of GI side effects. The other notable patient had Gilbert's syndrome (orange line) associated with increased indirect bilirubin. Gastrointestinal (GI)

Twenty-six patients paused dosing because of elevated transaminases, and one patient temporarily paused dosing because of side effects. Of the 27 patients that paused dosing, 23 returned to their targeted dose. The remaining four patients remained in the process of increasing their dose toward their target. Four patients decided to permanently stop medication, and only one patient (with rash) could not resume modified or full dosing.

Within the cohort were three individuals who had been removed from active treatment in the MOXIe study for persistent transaminase elevations > 5 × normal. These individuals were started on omaveloxolone clinically with close monitoring of hepatic function. All individuals again had a dramatic increase in transaminases requiring dose reduction. However, they were able to return to omaveloxolone treatment and after 1 year, and two of three have reached their target dose (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Change in a single subject excluded during MOXIe. Separate ALT graph of a single patient excluded from MOXIe because of persistent increased ALT. Multiple dose reductions with slowly increasing doses of commercial omaveloxolone allowed achieving the full dose. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Other Laboratory Values

Total cholesterol and LDL levels were slightly elevated on average after 12 months of OMAV treatment. The average ULN for total cholesterol was 197.0 mg/dl and the average ULN for LDL was 108.9 mg/dl. On average, there was a 0.07 (± 0.16) point increase in total cholesterol levels above the ULN and a 0.24 (± 0.16) increase in LDL levels above ULN (Fig. 3). Similarly, BNP had no meaningful change over the course of 1 year. The ULN for BNP was 100 pg/ml. Three patients with a history of cardiac dysfunction (low ejection fraction) had a slight increase in BNP, and one patient had a fall in BNP levels, suggesting no consistent effect of omaveloxolone on BNP (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Change in cholesterol, LDL, and BNP. A Total cholesterol (× ULN) at baseline and 12 months after 12 months of treatment. Patients had an average 0.07 (± 0.16) point increase relative to the ULN after 12 months of omaveloxolone. B LDL cholesterol (× ULN) at baseline and 12 months after 12 months of treatment. Patients had an average 0.24 (± 0.16) point increase relative to the ULN after 12 months of omaveloxolone. C BNP at baseline and at 12 months of treatment. BNP remained relatively unchanged. Outliers generally had pre-existing cardiac disease, potentially explaining fluctuations in BNP measurements. Upper limit of normal (ULN), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

Discussion

The clinical use of omaveloxolone over its first 19 months since release recapitulates most of the safety findings of the MOXIe trial. To this point, few major adverse events occurred with omaveloxolone treatment in either the MOXIe study or the clinical use described here. Omaveloxolone has been generally tolerated. These findings justify its ongoing use and suggest that the MOXIe study, as a representative clinical trial, reflects the effects in larger populations with FRDA.

Still, various issues can appear with omaveloxolone. While access to omaveloxolone was difficult for some subjects, the vast majority eventually had access to the agent. Surprisingly, while all patients were instructed to obtain laboratory values before starting omaveloxolone, only 57% had baseline transaminases. This low rate could reflect the unfamiliarity of the patient population with drug monitoring but also likely results from the delay between approval (Fevruary 28, 2023) and commercial availability (July 7, 2023) of the agent. Once started, laboratory abnormalities were modest; abnormalities in liver function were limited to transaminases and resolved with time in association with dose pausing or dose reduction. This is most consistent with a metabolic effect on the liver rather than a typical toxicity. Despite the effects of the related compound bardoxolone, no effects were noted on BNP values, and cholesterol changes, though present, were modest [23]. Side effects were also modest and transient; overall, most patients remained on the drug. In addition, apart from one individual with a significant rash, no new adverse events appeared.

Conclusion

Overall, patients have responded well to commercial treatment with omaveloxolone. Elevations in transaminases were expected and leveled out over time or after dose modification. Adverse events have been modest and were similar to those reported in the MOXIe trials. Further investigation should study the reported benefit and change in mFARS score after 1 year of treatment. Further investigations should also examine changes in cardiac disease.

Acknowledgments

Patients

The authors thank the patients for their participation.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing or editorial assistance was not received during the writing of this article.

Author Contributions

Katherine Gunther, Victoria Profeta, Medina Keita, Courtney Park, McKenzie Wells, Sonal Sharma, Kimberly Schadt, and David R. Lynch contributed to the study conception and design as well as assisted in material preparation. Data collection was performed by Katherine Gunther and Victoria Profeta. Data analyses were performed by Katherine Gunther and David R. Lynch. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Katherine Gunther and David R. Lynch. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study (both performance and the rapid service fee) was funded through a grant covering FACOMS/UNIFAI by FARA.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data were calculated using Stata version 18 (College Station, TX) or Graphpad (www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs). For analysis of proportions of elevated values, ULN was presumed to be Gaussian in distribution and thus represent two standard deviations greater than mean and analyzed by chi-square tests. For analysis of means, samples were compared to the ULN by one sample t-tests.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

David Lynch receives grants from Reata/Biogen pharmaceuticals for performance of the MOXIE and planned studies of omaveloxolone. He also receives grants from Larimar, PTC, Neurocrine, Solid Biosciences, the NIH, FDA, FARA and MDA. Katherine Gunther, Victoria Profeta, Medina Keita, Courtney Park, McKenzie Wells, Sonal Sharma, and Kimberly Schadt have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved through the CHOP IRB as study 2609 and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: This work was presented as an Abstract at the International Congress for Ataxia Research, November 2024.

References

- 1.Harding AE. Friedreich’s ataxia: a clinical and genetic study of 90 families with an analysis of early diagnostic criteria and intrafamilial clustering of clinical features. Brain. 1981;104:589–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandolfo M. Friedreich ataxia. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, Mandel JL, et al. Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rummey C, Farmer JM. Lynch DR Predictors of loss of ambulation in Friedreich’s ataxia. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;18: 100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsou AY, Paulsen EK, Lagedrost SJ, Perlman SL, Mathews KD, Wilmot GR, et al. Mortality in Friedreich ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307:46–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson DR, Lane DJ, Becker EM, Huang ML, Whitnall M, SuryoRahmanto Y, et al. Mitochondrial iron trafficking and the integration of iron metabolism between the mitochondrion and cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rötig A, de Lonlay P, Chretien D, Foury F, Koenig M, Sidi D, et al. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat Genet. 1997;17:215–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martelli A, Schmucker S, Reutenauer L, Mathieu JRR, Peyssonnaux C, Karim Z, et al. Iron regulatory protein 1 sustains mitochondrial iron loading and function in frataxin deficiency. Cell Metab. 2015;21:311–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abeti R, Parkinson MH, Hargreaves IP, Angelova PR, Sandi C, Pook MA, et al. Mitochondrial energy imbalance and lipid peroxidation cause cell death in Friedreich’s ataxia. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7: e2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lodi R, Cooper JM, Bradley JL, Manners D, Styles P, Taylor DJ, Schapira AH. Deficit of in vivo mitochondrial ATP production in patients with Friedreich ataxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11492–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strawser C, Schadt K, Hauser L, McCormick A, Wells M, Larkindale J, Lin H, Lynch DR. Pharmacological therapeutics in Friedreich ataxia: the present state. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17:895–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch DR, Perlman S, Schadt K. Omaveloxolone for the treatment of Friedreich ataxia: clinical trial results and practical considerations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2024;24:251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch DR, Goldsberry A, Rummey C, Farmer J, Boesch S, Delatycki MB, Giunti P, Hoyle JC, Mariotti C, Mathews KD, Nachbauer W, Perlman S, Subramony SH, Wilmot G, Zesiewicz T, Weissfeld L, Meyer C. Propensity matched comparison of omaveloxolone treatment to Friedreich ataxia natural history data. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024;111:4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch DR, Chin MP, Boesch S, Delatycki MB, Giunti P, Goldsberry A, Hoyle JC, Mariotti C, Mathews KD, Nachbauer W, O’Grady M, Perlman S, Subramony SH, Wilmot G, Zesiewicz T, Meyer CJ. Efficacy of omaveloxolone in Friedreich’s ataxia: delayed-start analysis of the MOXIe extension. Mov Disord. 2023;38:313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch DR, Chin MP, Delatycki MB, Subramony SH, Corti M, Hoyle JC, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Mariotti C, Mathews KD, Giunti P, Wilmot G, Zesiewicz T, Perlman S, Goldsberry A, O’Grady M, Meyer CJ. Safety and efficacy of omaveloxolone in Friedreich ataxia (MOXIe study). Ann Neurol. 2021;89:212–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch DR, Farmer J, Hauser L, Blair IA, Wang QQ, Mesaros C, Snyder N, Boesch S, Chin M, Delatycki MB, Giunti P, Goldsberry A, Hoyle C, McBride MG, Nachbauer W, O’Grady M, Perlman S, Subramony SH, Wilmot GR, Zesiewicz T, Meyer C. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and potential benefit of omaveloxolone in Friedreich ataxia. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;6:15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Oria V, Petrini S, Travaglini L, Priori C, Piermarini E, Petrillo S, Carletti B, Bertini E, Piemonte F. Frataxin deficiency leads to reduced expression and impaired translocation of NF-E2-related factor (Nrf2) in cultured motor neurons .Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:7853–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Shan Y, Schoenfeld RA, Hayashi G, Napoli E, Akiyama T, IodiCarstens M, Carstens EE, Pook MA, Cortopassi GA. Frataxin deficiency leads to defects in expression of antioxidants and Nrf2 expression in dorsal root ganglia of the Friedreich’s ataxia YG8R mouse model. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1481–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paupe V, Dassa EP, Goncalves S, Auchère F, Lönn M, Holmgren A, Rustin P. Impaired nuclear Nrf2 translocation undermines the oxidative stress response in Friedreich ataxia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4: e4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abeti R, Baccaro A, Esteras N, Giunti P. Novel Nrf2-Inducer Prevents Mitochondrial Defects and Oxidative Stress in Friedreich’s Ataxia Models. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rummey C, Corben LA, Delatycki M, Wilmot G, Subramony SH, Corti M, et al. Natural history of Friedreich ataxia: heterogeneity of neurologic progression and consequences for clinical trial design. Neurology. 2022;99:e1499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahir H, Murai M, Wu L, Valentine M, Hynes S. Clinical assessment of the drug-drug interaction potential of omaveloxolone in healthy adult participants. J Clin Pharmacol. Published online February 7, 2025. 10.1002/jcph.6189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chin MP, Wrolstad D, Bakris GL, Chertow GM, de Zeeuw D, Goldsberry A, Linde PG, McCullough PA, McMurray JJ, Wittes J, Meyer CJ. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J Card Fail. 2014;20:953–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data were calculated using Stata version 18 (College Station, TX) or Graphpad (www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs). For analysis of proportions of elevated values, ULN was presumed to be Gaussian in distribution and thus represent two standard deviations greater than mean and analyzed by chi-square tests. For analysis of means, samples were compared to the ULN by one sample t-tests.