Abstract

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is a rare type of autoimmune neuropathy, characterized by signs of distal and proximal weakness of the upper and lower limbs, sensory dysfunction, absent or diminished tendon reflexes, and symptoms of numbness, tingling, pain, and fatigue. These signs/symptoms can lead to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and reduced manual dexterity. Detailed qualitative exploration of the patient experience of CIDP, notably signs/symptoms, its impacts on health-related quality of life, and treatment experience is limited. Qualitative patient experience data is recommended by regulatory bodies to inform patient-focused drug development. This study aimed to qualitatively explore the experience of CIDP from the patient and clinician perspectives.

Methods

Qualitative concept elicitation telephone interviews were conducted with adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CIDP and with neurologists experienced in diagnosing and treating patients with CIDP from the USA. Interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis methods, and findings informed development of a conceptual model.

Results

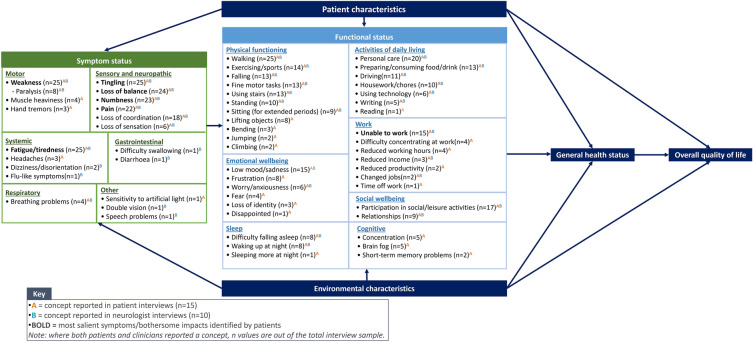

Overall, 15 patients with CIDP and 10 neurologists were interviewed. A total of 19 signs/symptoms were identified as important and relevant, of which weakness, fatigue, loss of balance, tingling, numbness, pain, and loss of coordination were most frequently reported by patients and neurologists. Except for loss of coordination, these signs/symptoms were also considered most salient to patients. Patients identified fatigue as the most bothersome symptom and weakness and fatigue as the most important to treat. CIDP impacted health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL), including physical functioning (e.g., walking difficulties), activities of daily living (e.g., difficulty with personal care), work (e.g., being unable to work), emotional wellbeing (e.g., depression), social wellbeing (e.g., participation in social/leisure activities), sleep (e.g., difficulty falling asleep), and cognition (e.g., brain fog). Patients reported that current CIDP treatments lacked effectiveness in treating specific symptoms, caused unwanted side effects, and impacted their independence.

Conclusions

Findings contribute novel and detailed qualitative insights into the key signs/symptoms of CIDP and the profound impact of these on patients’ HRQoL from both the patient and clinician perspectives. Findings can be used to identify treatment targets and support selection of appropriate clinical outcome assessments for the evaluation of CIDP symptoms and HRQoL impacts in future CIDP clinical trials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00732-y.

Keywords: Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), Patient experience, Qualitative research, Conceptual model, Symptoms, Health-related quality of life, Impacts

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| There are no published studies that provide a detailed, in-depth analysis of the patient experience of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and associated treatments using qualitative methodology. |

| These data are needed to ensure that clinical trials evaluating the effect of new treatments are assessing concepts that are relevant and meaningful concepts to patients with CIDP to ensure patient-focused drug development. |

| In this study, patients were asked to describe the symptoms they experience due to CIDP, the impact of CIDP on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL), and their experience of treatment for CIDP. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Weakness, fatigue, loss of balance, tingling, numbness, and pain were the most frequently reported and most salient symptoms to patients. HRQoL impacts associated with physical functioning, activities of daily living, work, emotional wellbeing, social wellbeing, sleep, and cognition were all reported. Existing CIDP treatments were reported as lacking effectiveness, causing side effects, and impacting independence. |

| These findings can be used to identify the specific and measurable aspects of patient functioning in which change is desired and select appropriate clinical outcome assessments to evaluate these concepts in future CIDP clinical trials. |

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is a rare type of autoimmune neuropathy, with an estimated overall prevalence ranging from 0.67 to 10.3 cases per 100,000 [1]. It is more common in males than females and in those between the ages of 40 and 60 years, although all age groups can be affected [2, 3]. While the exact etiology remains largely unknown, it is believed that CIDP involves both cell-mediated and humoral mechanisms that target myelin components of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) [4]. Clinical presentation is diverse, with typical CIDP characterized by progressive or relapsing symmetric distal and proximal weakness of the upper and lower limbs, sensory dysfunction, and absent or diminished tendon reflexes, developing over a period of at least 8 weeks [5]. Patients may also report symptoms of numbness, tingling, pain, and fatigue [6, 7]. These symptoms can lead to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and arising from a chair, as well as reduced manual dexterity [3]. Due to heterogeneity in PNS involvement and response to treatment, the clinical spectrum varies widely, ranging from patients who are mostly asymptomatic to those who are wheelchair bound [8].

First-line therapy options are corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg), followed by plasma exchange (PE) if first-line therapies are ineffective [5]. Subcutaneous immunoglobulins (SCIg) may also be used as a maintenance therapy [5, 9]. While most patients respond well to these treatments, approximately 15% remain refractory to all treatment modalities [10]. Even when these therapies are effective, patients with CIDP may experience treatment burden due to the high risk of adverse events associated with long-term steroid use [11], and the mode of administration required for parenteral therapies (e.g., IVIg, PE) can impact patient independence [12, 13]. Despite treatment, many patients also continue to experience symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, and weakness [14]. Thus, there is an unmet need for CIDP treatments that are not only effective, but that also align with the needs and priorities of patients [15].

Patient-focused drug development ensures the experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities of patients are considered and meaningfully incorporated throughout medical product development and evaluation [16]. However, at present there is little understanding of the patient experience of CIDP [15, 17–19]. Review of the published literature identified only two studies exploring the burden of CIDP from the patient perspective [17, 19]. While these studies provide initial insight into the CIDP patient experience of signs/symptoms, impacts, and treatment burden, data were obtained from quantitative surveys of patients with a self-reported diagnosis of CIDP. Qualitative methods are typically better suited for obtaining a deep understanding of human experience, particularly when little is known about a phenomenon. Consequently, regulatory bodies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), recommend the use of qualitative methods with the target population in order to obtain comprehensive and rich insights into the patient experience of a disease to inform patient-focused drug development [20].

The objective of this study was to conduct qualitative research with patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CIDP and with neurologists involved in the care and treatment of patients with CIDP, to obtain detailed insights into the patient experience, including relevant signs/symptoms, functional impairment, and wider health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) impacts, and experience with treatments. The findings were used to develop a conceptual model to illustrate the patient experience of CIDP.

Methods

Study Design

This was a non-interventional, cross-sectional, qualitative study involving semi-structured concept elicitation (CE) interviews with CIDP patients and neurologists experienced in treating CIDP. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study design

Sample

A sample of 15 patients with CIDP from the USA was targeted for the interviews. The European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society 2010 guidelines were used for the definition of CIDP [21]. To be eligible to participate, patients had to be at least 18 years of age and have either a clinician-confirmed clinical diagnosis of typical CIDP, pure motor, or Lewis Sumner atypical CIDP (supported by electrophysical and other diagnostic criteria) or a self-reported clinical diagnosis of typical CIDP, pure motor, or Lewis Sumner atypical CIDP (supported by additional official documentation of CIDP diagnosis/treatment). To be eligible, patients were also required to be currently experiencing symptoms of CIPD (as determined via self-report) that affect functioning (e.g., walking, holding utensils, dressing, personal care, etc.). A target of 15 patient interviews was expected to be sufficient for achieving ‘saturation’: the point at which no new concept-relevant information is likely to emerge with the conduct of additional interviews [22, 23]. Target sampling quotas were used to promote representation of patients with a range of demographic and clinical characteristics within the sample (e.g., age, race, CIDP subtype). To capture a diversity of patient perspectives regarding treatment experience, quotas were also set with the view to recruit patients who were currently or had previously received a treatment normally provided to people with CIDP (referred to standard of care [SOC]). SOC treatments included corticosteroids, IVIg, SCIg, and PE. Three treatment groups were targeted: SOC-treated patients (i.e., those currently receiving CIDP treatment that was effective), SOC-refractory patients (i.e., those receiving CIDP treatment that was not effective enough or who had stopped previous CIDP treatment due to side effects), and SOC-naïve patients (i.e., those who had not received previous treatment for CIDP). Ten neurologists from the USA with experience in diagnosing and treating patients with CIDP were also targeted to provide a clinical perspective. All neurologists were required to have at least 5 years of experience treating patients with CIDP and had treated or been responsible for the management of at least five patients with CIDP in the past 12 months. Neurologists were not the treating clinicians of the patients recruited for the interviews. A full description of eligibility criteria for the patients and neurologists are available in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table S1 and ESM Table S2, respectively.

Recruitment

A purposive sampling method was used to recruit participants for the interviews, which involved selecting participants based on the eligibility criteria and target sampling quotas [24]. Patients were identified by specialist recruitment agencies (Pinpoint, Liberating Research, and MedQuest) via referring clinicians, patient advocacy groups, and patient panels. For patients identified via referring clinicians, eligibility was confirmed in a case report form (CRF) completed by the referring clinician and in a patient screener completed by the patient/recruitment agency. Where confirmation of CIDP diagnosis could not be confirmed by a practicing clinician, patients were required to provide official documentation (e.g., hospital/clinic letters, prescriptions, copies of health/medical records) as evidence of CIDP diagnosis and/or treatment. Self-reported demographic and health information was also collected for all eligible patients who consented to participate in the study.

Neurologists were similarly identified by a specialist recruitment agency (MedQuest) as well as by the Guillain-Barré Syndrome/CIDP Foundation International Centers of Excellence. Interested neurologists completed a clinician screener to confirm their eligibility, and eligible neurologists completed a clinical/professional experience form to characterize the clinician sample.

All participants received compensation for their participation in line with fair market value and general ethics principles for research with human participants [25, 26].

Interview Procedure

All interviews were conducted via telephone by trained qualitative interviewers, using a semi-structured interview guide.

Patient interviews were approximately 60 min in length, exploratory in nature, and focused on eliciting information regarding the patient experience of signs/symptoms and impacts of CIDP. Patient interviews began with open-ended questioning (e.g., “please can you describe what it’s like to live with CIDP?”) to facilitate spontaneous elicitation of sign/symptom and impact concepts. Open-ended questioning was followed by more focused probes, designed to probe participants on topics of interest that they may not have mentioned during the interviews (e.g., “do you experience [symptom] as part of your CIDP? Please tell me about that.”) or that required further exploration or clarification. For each sign/symptom concept mentioned, patients were also asked to describe and rate the relative bothersomeness of the sign/symptom using a numerical response scale (NRS) from 0 (‘least bothersome’) to 10 (‘most bothersome). Patients were also asked to select which symptom they considered most bothersome and which they considered most important to treat. To explore unmet treatment needs, patients were also asked to describe their perceptions regarding current CIDP treatments and desired characteristics for future CIDP treatments.

Neurologist interviews were approximately 30 min in length and focused on obtaining clinical insights into the patient experience of CIDP. Initial discussions consisted of broad, open-ended questioning designed to elicit information regarding neurologists’ experience in treating CIDP patients and how patients typically present with CIDP, with a specific focus on the signs/symptoms and impacts associated with the condition. This was followed by more specific probes to elicit information that may not have been mentioned spontaneously.

Qualitative Analysis

All patient and neurologist interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifiable information redacted. Interview transcripts were subject to thematic analysis using Atlas.Ti Scientific Software (version 22) [27]. Participant quotes pertaining to the signs/symptoms, impacts, and aspects related to unmet treatment need were assigned corresponding concept codes in accordance with an agreed coding scheme. Codes were applied both deductively (based on prior knowledge) and inductively (as identified within the data). Based on the interview findings, a conceptual model was developed to display the key concepts associated with CIDP, including signs/symptoms and impacts on functioning and HRQOL.

Salience graphs were also produced to provide a visual illustration of the most salient signs/symptoms from the patient perspective. Salience was determined by calculating the mean bothersome score for each sign/symptom (based on patient ratings on the 0–10 NRS). Signs/symptoms reported by > 80% of patients and with an average bothersome score > 5 were considered to be the most salient [28]. The salience graphs were used to identify key concepts for defining treatment benefit from the patient perspective and were highlighted in the resulting conceptual model.

Saturation analysis was conducted to determine the appropriateness of the patient sample size to elicit important and relevant concepts. Transcripts were chronologically grouped into three equal sets (n = 5 each), and spontaneously reported sign/symptom and impact concepts identified within each set were iteratively compared. Saturation was deemed achieved if no new important or relevant symptom/impact concepts were spontaneously reported in the final set of interviews [22].

Ethical Approval

All participants provided written and oral informed consent prior to the conduct of any study activities. Ethical approval and oversight were obtained from WCGIRB, an independent review board in the USA (IRB tracking number: 20220058). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments and in line with guidelines related to Good Clinical Practice. All data resulting from the study were handled in accordance with US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) legislation and the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for the security and privacy of health data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Patient Sample Characteristics

A total of 15 adults with CIDP from the USA were interviewed as part of this study. Patients ranged in age from 38 to 82 (mean 57) years, and most were female (60.0%), of white-European heritage (73.0%), and had a diagnosis of typical CIDP (93.0%). Nearly equal proportions of patients were classed as SOC-treated (53.0%) and SOC-refractory (47.0%). At the time of the interview, the majority of patients (87.0%) reported being treated with IVIg. Some patients also reported being treated with a corticosteroid (e.g., methylprednisolone) (40.0%) and receiving PE (20.0%). Table 1 provides an overview of the sample characteristics together with the corresponding target quotas.

Table 1.

Patient sample characteristics and achievement of target sampling quotas (N = 15)

| Criteria | Quota sampling target | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | n ≥ 8 | 6 (40) |

| Female | n ≥ 5 | 9 (60) |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 50 | n ≥ 5 | 4 (27) |

| ≥ 50 | n ≥ 5 | 11 (73) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | n ≥ 5 | 0 (0) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | n ≥ 5 | 15 (100) |

| Race | ||

| White–European heritage | n ≥ 5 | 11 (73) |

| Other racial groups | n ≥ 5 | 4 (27) |

| Working status | ||

| In employment | n ≥ 3 | 7 (47) |

| Not working | n ≥ 3 | 8 (53) |

| Clinical subtype | ||

| Typical | n ≥ 12 | 14 (93) |

| Atypical | n ≥ 2 | 1 (7) |

| Standard of care (SOC) treatment responsea | ||

| SOC-refractory | n = 8 | 7 (47) |

| SOC-treated | n = 5 | 8 (53) |

| SOC-naïve | n = 2 | 0 (0) |

| Treatments currently receiving, n (%) | ||

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | N/A | 13 (87) |

| Subcutaneous immunoglobulin | N/A | 1 (7) |

| Plasma exchange | N/A | 3 (20) |

| Corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) | N/A | 6 (40) |

| Other (e.g., rituximab, CellCept) | N/A | 6 (40) |

| Not reported | N/A | 1 (7) |

aClinician reported where possible, otherwise self-reported

NA not applicable

Target sampling quotas were achieved for sex (female), age (50 years or older), ethnicity (not Hispanic/Latino), race (white-European Heritage), and clinical subtype (typical CIDP), but missed for sex (male), age (under 50 years), and clinical subtype (atypical and SOC-naïve) due to recruitment challenges.

Neurologist Sample Characteristics

Ten neurologists from the USA were also interviewed as part of the study. Most worked in private practice (60.0%) and had between 20 and 34 years of experience treating patients with CIDP (60%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neurologist sample characteristics (N = 10)

| Description | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Employment settinga | |

| Clinics | 3 (30) |

| Hospital-based care | 4 (40) |

| Private practice | 6 (60) |

| University or college affiliated | 2 (20) |

| Years of experience | |

| 5–9 | 2 (20) |

| 10–14 | 1 (10) |

| 15–19 | 1 (10) |

| 20–24 | 3 (30) |

| 25–29 | 2 (20) |

| 30–34 | 1 (10) |

aClinicians could select multiple options

Concept Elicitation Findings

The findings from the patient and neurologist interviews were summarized in a conceptual model, displaying the key sign/symptom and impact concepts associated with CIDP (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP)

Signs and Symptoms

A total of 19 signs/symptoms were reported during the patient and neurologist interviews. Weakness, fatigue, loss of balance, tingling, numbness, pain, and loss of coordination were most frequently mentioned across the patient and neurologist interviews (see Table 3 for example quotes). Except for loss of coordination, these symptoms were also identified as the most salient to patients. Average bothersomeness ratings for these concepts were moderate to high (range: 5.6–7.5; Fig. 3). Most patients suggested fatigue was the most bothersome symptom (n = 7) and that fatigue and weakness (both: n = 5) were the most important symptoms to treat. Nearly all neurologists’ suggested weakness was the most important to treat (n = 9) and the most important to measure in the context of a clinical trial (n = 8). Generally, similar proportions of SOC-treated and SOC-refractory patients reported experiencing each symptom during the interviews, and no notable differences in symptom experience were observed by sex.

Table 3.

Overview of the most frequently reported symptoms of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in the patient and neurologist interviews

| Sign/symptom | Patient interviews (N = 15) | Neurologist interviews (N = 10) | Example supportive quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weakness | n = 15/15 | n = 10/10 | “…muscles below the knee, um, are almost all affected. Um, feet either I’ve got muscles that have atrophied to nothing. Um, I’ve got—some I’ve got toe weakness. I’ve got foot weakness. Um, I’ve got weakness around the ankles that push down the step, which is the calf muscles and the muscles in the shin.” (46-year-old female, SOC-treated) |

| “So mostly it’s weakness, um, fine finger movement problems, ah, upper limbs, lower extremity weakness is the major thing that people are having issues with.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Fatigue | n = 15/15 | n = 10/10 | “So I'm just constantly tired like exhausted. Um, energy level is much worse than how I was before for sure.” (38-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| “I don’t think I've seen a patient in years that has not said that they are not tired or fatigued.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Loss of balance | n = 15/15 | n = 10/10 | “I could just be walking and then I'm losing my balance going to the right. I have to hug the wall or something.” (64-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| “…when you have your nerves getting damaged, obviously when you stand up, uh, number one, you don’t have good what we call proprioception…And that can certainly affect your balance.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Tingling | n = 15/15 | n = 10/10 | “The numbness and tingling on my toes and feet. And I get that with my mouth and tongue also.” (51-year-old female, SOC-treated) |

| “It's often not a pure numbness, but it's more of a tingling sensation and a sharp pain at times. So sharp pain, pins and needles, tingling, um, not so much pure numbness.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Numbness | n = 13/15 | n = 10/10 | “I feel like my feet are very heavy with numbness. Like, uh, sometimes they don’t feel like it's there. That's how numb it gets. Like I wouldn’t feel if I stepped on anything, you know.” (64-year old female, SOC-refractory) |

| “It's primarily numbness and weakness.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Pain | n = 13/15 | n = 9/10 | “It can sometimes feel like burning or, um, like, um, shooting pain, sharp pain.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| “Any, uh, burning sensation or, um, achiness or different kinds of pain because of the loss of myelin sheath in the nerves, the nerves become painful and when they walk or even sometimes sitting or standing.” (Expert neurologist) | |||

| Loss of coordination | n = 12/15 | n = 7/10 | “…loss of coordination is me not being able to like walk a straight line or I bump in—might end up walking sideways or something.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| “Um, so I feel like the motor component is the big deal because the motor component is what’s causing the balance problems, and the motor component is causing the, the coordination problem, do you know what I’m saying. Everything is all due to the motor problem.” (Expert neurologist) |

SOC Standard of care

Fig. 3.

Most salient chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) symptoms identified by patients based on average bothersomeness score (N = 15)

Most patients reported experiencing signs/symptoms in specific areas of the body. Weakness, tingling, and numbness were most commonly experienced in the distal and proximal upper and lower limbs (e.g., arms, hands, legs, feet), whereas pain was reported across several areas of the body, including the legs, feet, trunk, arms, hands, muscles, and nerves. Patients reported considerable variation in the frequency and duration of symptoms (ranging from constantly to situation dependent); however, more than 45.0% of patients reported experiencing weakness, tingling, and numbness all the time.

Several other symptoms were reported less frequently by patients (n = ≤ 4), including loss of sensation, heaviness, hand tremors, headaches, eye problems, and breathing problems.

Impacts of CIDP

The impacts of CIDP on patients’ functioning and HRQoL are grouped into seven domains: physical functioning, activities of daily living (ADL), emotional wellbeing, social wellbeing, work, sleep, and cognitive functioning (see Table 4 for example quotes). Patients mostly discussed impacts spontaneously, and the proportion of SOC-treated and SOC-refractory patients reporting on the various domains was relatively consistent. With the exception of cognitive functioning, all impact domains were also reported by the neurologists.

Table 4.

Overview of impact domains reported by patients and clinicians during the interviews

| Domain/concept | Patient interviews (N = 15) | Clinician interviews (n = 10) | Supportive example quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | |||

| Walking | n = 15/15 | n = 10/10 | “I now walk with a cane because my balance is off. The strength in my left leg is not there anymore because of the demyelination.” (59-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Falling | n = 11/15 | n = 2/10 | “…when a patient is trying to get off, uh, a chair or walker and trying to sit on a, on a toilet and they're trying to get off the toilet, a lot of times they fall down.” (Neurologist) |

| Exercising | n = 11/15 | n = 3/10 | “…would love to get back to being able to play golf, which I can't now. The balance issues are too bad. (76-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Using stairs | n = 11/15 | n = 2/10 | “…usually it begins with the distal paresthesia that extends to the proximal muscles associated with pain and associated with weakness, especially difficulty climbing stairs.” (Neurologist) |

| Fine motor skills | n = 11/15 | n = 2/10 | "…sometimes I'm just holding my water bottle, I feel like I'm gripping it tightly and my hands begin to shake. But I have to hold on to it as tight as I can in order to drink.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Standing | n = 9/15 | n = 1/10 | “…it's difficult because like I said, I can literally only stand and sit usually five, ten minutes.” (51-year-old female, SOC-treated) |

| Lifting objects | n = 8/15 | Not reported | “…it shows itself in terms of, um, not being able to lift heavy things that someone my age and build would normally be able to lift.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Sitting | n = 6/15 | n = 3/10 | “The tingling again is going to be distal, um, but it can include the entire extremity at times. Um, they feel it more when they're sitting than when they're ambulating.” (Neurologist) |

| Bending | n = 3/15 | Not reported | “Before that, I could play golf. A lot of times my son would put the ball on the tee for me, but bending down was an issue.” (76-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Jumping | n = 2/15 | Not reported | “No running, um, no jumping. Um, I can't tiptoe. I can't walk on my heels. (38-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Climbing | n = 2/15 | Not reported | “I'm constantly reminded of the limitations of it. Like I said, like trying to lift stuff or climb stuff.” (52-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Activities of daily living | |||

| Personal care (e.g., dressing, showering) | n = 14/15 | n = 6/10 | “…dressing yourself, it all requires coordination and it requires strength, um, two of which are things that are the major components of CIDP that people don't have. They can’t button their own clothes, they can’t tie their own shoelaces.” (Neurologist) |

| Driving | n = 9/15 | n = 2/10 | “So on occasion, um, I'll ask my husband or parents to drive me somewhere. If I know that whatever I'm doing is going to be physically taxing, then I might be too tired to drive home.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Preparing/consuming food and drink | n = 9/15 | n = 4/10 | “…for example…that would be eating, drinking, and taking a shower, or doing everyday things, the upper extremities could also be affected, you know, weakness and upper extremities.” (Neurologist) |

| Housework/chores | n = 8/15 | n = 2/10 | “I feel like it’s like a lot more strained to do regular activities, ah, like washing myself, like, you know, washing dishes or something like that. Usually washing myself is not as much of a problem as physically picking up heavy pots.” (53-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Work | |||

| Unable to work | n = 9/15 | n = 6/10 | “I mean if their degree of weakness is severe enough, they're not, they're not able to work.” (Neurologist) |

| Reduced working hours | n = 4/15 | Not reported | “I only work, you know, like four hours a day, um, and I pretty much take it easy during the day.” (53-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Difficulty concentrating at work | n = 4/15 | Not reported | “…sometimes when I’m at work, um, I can tell like my, my concentration isn’t as it should be, like as it was, um, even you know like after, like after my infusions or whatever, and that does not necessarily just happen as I get closer to my infusion.” (53-year-old female, SOC-refractory) |

| Emotional wellbeing | |||

| Frustration | n = 8/15 | Not reported | “…it's just sort of a frustrating thing. Yeah. Usually when you have something wrong with you, you get it fixed and, and it stops. And, and this is more like an ongoing thing that you have to live with.” (82-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Low mood/sadness/depression | n = 8/15 | n = 7/10 | “I mean if their degree of weakness is severe enough, they're not, they're not able to work. Um, the, the degree of pain could also be significant. Um, and they, they often get depressed from just the, the disability.” (Neurologist) |

| Social wellbeing | |||

| Participation in social/leisure activities | n = 14/15 | n = 3/10 | “…just the fatigue…I may not be able to do the same things as my friends want to do. Like, um, until the last couple years, I wasn’t able to really go to sporting events just 'cause it's, it's such a long, all-day type thing and it was hard for me…so people stopped calling me to, to do that stuff because I always said no.” (52-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Relationships | n = 7/15 | n = 4/10 | “…they feel like, you know, they’re a burden to others or a burden to their loved ones or their caregivers.” (Neurologist) |

| Sleep | |||

| Difficulty falling asleep | n = 5/15 | n = 3/10 | “…sometimes it's [burning pain] so bothersome it—I mean I just—I can't sleep with it, so I have to roll around and try to figure—reposition myself and do whatever I can to make it as cooled, cooled off as much as I can.” (76-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

| Waking up at night | n = 5/15 | n = 3/10 | “…the neuropathic pain will disrupt their sleep.” (Neurologist) |

| Cognitive | |||

| Brain fog | n = 5/15 | Not reported | “If you're just exhausted, you feel—it can feel like brain fog that can be there with it and that for me is exacerbated, um, when I'm feeling fatigued.” (46-year-old female, SOC-treated) |

| Reduced concentration | n = 5/15 | Not reported | “It can make it a little bit harder for me to concentrate on what I’m doing, you know, focus on my motor activities, so I might make mistakes or overshoot or undershoot certain things that I’m trying to do because of the tingling, because it affects a little bit my ability to sense where my body is in space, because the tingling is kind of taking over my senses.” (53-year-old male, SOC-treated) |

SOC Standard of care

CIDP impacted physical functioning, with difficulty walking (including risk of falling, difficulty walking long distances, and being unable to walk without a walking aid, such as a cane or walker) being the most commonly mentioned impact by both patients and neurologists. Difficulty using stairs (e.g., needing to take more care, using a handrail), standing (e.g., difficulty standing from a seated position or for long periods of time), and impacts on their ability to engage in sports and exercise activities (e.g., ability to run, hike, workout, and cycle) were also reported. Several patients described difficulty performing fine motor tasks, including holding and picking up objects, as well as difficulty lifting objects, particularly those that were heavy. Other physical functioning impacts reported less frequently included difficulty sitting, bending, jumping, and climbing. Generally, impacts on physical functioning were associated with weakness, loss of coordination, and loss of balance.

CIDP was also reported to impact ADL. All patients reported needing support to perform ADL, including the use of specialized or adaptive equipment (e.g., walking aids, handrails, seat lifts, wheelchairs) and assistance from others (i.e., family, friends, and formal carers/support workers). Difficulty performing personal care, such as showering and dressing, was most frequently mentioned across the patient and neurologist interviews. This was often associated with loss of balance, loss of coordination, and weakness. Several patients also reported difficulty driving (including no longer being able to drive, difficulty driving, driving shorter distances, and driving less overall), which was most commonly associated with weakness. Difficulty preparing/consuming food and drink was also frequently mentioned. Patients primarily described difficulty gripping objects when preparing meals or eating and either finding it too tiring or feeling too tired to cook. This impact was mostly reported by SOC-refractory patients (SOC-refractory: n = 7/7; SOC-treated: n = 2/8) and was often associated with weakness and fatigue. Many patients also reported difficulty with household chores (e.g., cleaning and laundry), describing these activities as challenging or tiring to perform. Other ADL impacts mentioned less frequently included difficulties using technology, writing, and reading.

Work impacts were mentioned throughout the interviews and were most frequently identified by patients as the most bothersome impact (n = 5). Most patients reported that they were no longer able to work either due to their symptoms/cognitive impacts of CIDP or because they had been medically classed as disabled. This was further reflected in the neurologist interviews, with most reporting that patients with CIPD are often unable to work due to their signs/symptoms or side effects of treatment. For those who were still employed, most patients reported having to reduce their working hours, and some patients also reported difficulty concentrating at work and reduced work productivity.

CIDP impacted emotional wellbeing, with patients most frequently reporting feeling frustrated or sad due to their condition and being unable to perform ADL and work. Feelings of sadness were similarly reflected in the neurologist interviews, with most suggesting that patients’ inability to work and perform daily tasks often resulted in depression. Patients most commonly attributed these feelings to pain, fatigue, and weakness. Some patients also discussed feeling worried or afraid. Reasons for this were varied, but included concern about disease progression/the recurrence of symptoms, the ability to care for themselves, and the fear of falling. Additionally, the inability to work was reported by some patients to negatively affect their sense of identity.

In terms of social wellbeing, patients reported significant impact on their ability to take part in social and leisure activities. This included (but was not limited to) attending sporting events, traveling, and playing sports (e.g., golf and basketball). Patients most commonly attributed this to weakness, fatigue, and loss of balance. Related to this, patients also described impacts on their relationships, most notably with intimate partners and family.

Sleep impacts were also reported, with patients describing difficulty falling asleep and waking up during the night, primarily due to pain. Over half the patients also reported experiencing cognitive impacts, including ‘brain fog’ and difficulty concentrating, which they most commonly attributed to fatigue.

CIDP Treatment Experience and Unmet Treatment Needs

Of the 15 patients interviewed, 13 (86.7%) discussed their experience with current CIDP treatments and desired characteristics for future treatments, providing insight into the unmet treatment needs of patients with CIPD. Three themes were identified, relating to: (1) treatment effectiveness, (2) treatment side effects, and (3) treatment delivery modes. No clear differences were observed between SOC-treated and SOC-refractory patients, suggesting that unmet treatment needs may be similar between these two patient groups.

Treatment Effectiveness

Several patients reported that their current CIDP treatments were ineffective in targeting specific signs/symptoms (e.g., pain, weakness, numbness) and that their ideal treatment would provide greater relief from signs/symptoms:

“And, um, the weakness seems to be getting worse. So I don’t—I'm, I'm really having trouble finding out if the IVIG is, uh, helping the weakness…they suggest I keep, keep taking the IVIG. But I don’t see how that's helping the numbness. And I can't correlate the, the medication to that. So I don’t know what can be done for the weakness.” (82-year-old male, SOC-treated)

“… if it were terribly uncomfortable and inconvenient, then I, I wouldn’t love it, but it, it's really much more important that it be effective than anything else for me.” (48-year-old female, SOC-refractory)

Even when treatments were effective, patients frequently reported that they typically only experience short-term relief, with signs/symptoms often returning in between treatment cycles:

“So it's very, um, debilitating at times. I think right after I have my treatment, it's good for two days and then it starts going downhill 'til the next treatment.” (64-year-old female, SOC-refractory)

“And it's challenging because I get the treatment, which does improve my, um, symptoms and situation…And then the last two weeks—so I'm on a six-week cycle. Um, the last two weeks, I start slowing down, dragging my feet, um, becoming more fatigued and tired.” (59-year-old female, SOC-treated)

Some patients also reported that their current CIDP treatments only seemed to stop their signs/symptoms from worsening, rather than improving signs/symptoms and restoring previous levels of functioning:

“… when I started treatment up again, it kind of stopped everything where it was. So I feel like it doesn’t—the treatment doesn’t cure you. It kind of stops the CIDP from getting worse…” (51-year-old female, SOC-treated)

“I want to say, you know, the ability to actually medicate in a way that restores some of the, the capabilities that I don’t have any longer… I mean obviously preventing it from getting any worse is important. But, um, making sure that I'm able to, to see some degree of improvement would be a big, big thing for me.” (76-year-old male, SOC-treated)

Treatment Side Effects

In addition to greater treatment effectiveness, many patients discussed a desire for CIDP treatments with fewer or minimized physiological side effects, including headaches/migraines, fatigue, nausea, and brain fog:

“… I also want side effects to be minimized. So for instance, one of the side effects that I do get from IVIG is headaches. Um, you know, I've had them where it's just a little headache for a little while and that's not so bad. But when it's a headache that's lasting four days or five days, then, then that is, is a little scary.” (59-year-old female, SOC-treated)

“…the lesser side effects the better and the, um, most importantly, it's manageable. So it's, it's, you know, something that I can take at home, still go about my day, and not feel nauseous or feel fatigued.” (38-year-old female, SOC-refractory)

One participant also specifically mentioned having to temporarily stop their CIDP treatment due to experiencing a pulmonary embolism, which doctors suspected was caused by IVIg:

“I developed a pulmonary embolism, and they believe it was from the IVIg treatment. So we stopped treatment for six months to get my…blood levels under control.” (51-year-old female, SOC-treated)

Treatment Delivery Modes

The mode of delivery required for CIDP treatments was frequently reported by patients to impact their independence. Specifically, patients commented that their medication schedule and the need for medical staff to administer their treatment impacted their daily life, social functioning, and ability to participate in activities, such as travel:

“…I need to be in the hospital here, um, at where I live, um, every other week for that treatment …Um, that ties me to here, um, in terms of being able to be mobile…Um, a vacation needs to be very carefully planned around, you know, how long. And I've never been gone for more than three weeks, um, which is a sizeable amount of time, but still tied back.” (46-year-old female, SOC-treated)

“Or if [my friends] were going on a vacation, like if they wanted me to tag along, I would say no just because I had to worry about my prescriptions...so people just stop calling eventually.” (52-year-old male, SOC-treated)

Consequently, patients reported a desire for CIDP treatments they could administer themselves (e.g., a pill), without the assistance of a medical professional:

“Um, ideally for me would be either a pill that I could take or a shot I could give myself, um, and that would be it. It wouldn’t require, you know, a nurse...It would be something I could do myself, um, at home.” (55-year-old female, SOC-refractory)

“So I would say something where I could, I could do the treatments on my own without having to coordinate with a pharmacy to deliver medicine, nurses to show up and, and have to be with me, um, over two or four days to do this treatment. If it was something I could just do for myself and only have to deal with the pharmacy, that would be great.” (59-year-old female, SOC-treated)

Similarly, patients expressed a desire for treatments that could be administered less frequently and that took less time to receive:

“Um, I mean the more space between the, between the treatments would be great. If I had to do it like every day that would be, you know, a pain. But—so if, if it could—whatever the treatment is, as much time between doses would be the better, the more, the better.” (52-year-old male, SOC-treated)

“Well I mean I think the, the ease of, um, you know, medicating and the, uh, volume or the time involved are certainly the major factors as far as I'm concerned. I mean to minimize the amount of time involved is—would be really significant for me.” (76-year-old male, SOC-treated)

Apart from increased independence, some patients also reported a preference for treatments that did not require the use of needles, with one patient specifically referencing the pain they experience from IV treatments as their reason:

“I guess how it's administered somewhat because if they could avoid doing IVs, that would be perfect because I don’t have to go through that pain of being poked so many times.” (64-year-old female, SOC-refractory)

Saturation Analysis

Only one new symptom concept was spontaneously reported in the final set of interviews: sensitivity to artificial light. As there is no apparent evidence in the literature that CIDP causes sensitivity to light, it was determined that this was not a core (i.e., important and relevant) symptom of CIDP. No new impact concepts were spontaneously reported in the final set of interviews. Together, results of the saturation analysis suggest the sample size was sufficient to elicit the core symptoms and impacts of CIDP and that saturation was achieved.

Discussion

Patient-focused drug development ensures that the experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities of patients are considered throughout the drug development and evaluation process [16, 20]. However, there is limited evidence specific to the patient experience of CIDP in the published literature [15, 17–19]. This study sought to address this gap by exploring the experience of CIDP, including relevant signs/symptoms, functional impairment and HRQoL impacts, and unmet treatment needs, through the conduct of in-depth qualitative interviews with patients and neurologists in the USA.

Findings from the qualitative interviews provide detailed evidence of the signs and symptoms that patients experience and the significant impact of these on patients’ functioning and HRQoL. There were little to no apparent differences in the experience of signs/symptoms and associated impacts between SOC-treated and SOC-refractory patients, suggesting that the patient experience between these two groups could be similar.

The signs and symptoms identified in this study were broadly consistent with those identified in the previous literature [5–7, 12, 17], particularly those of weakness, tingling, fatigue, loss of balance, numbness, pain, and loss of coordination. However, the present study provides a more in-depth understanding of the patient experience of CIDP signs and symptoms than was previously available. Notably, the findings provide evidence that, apart from loss of coordination, the most frequently reported signs and symptoms are also those that are the most salient to patients. Among these, fatigue and weakness were identified by patients as the most important signs/symptoms to treat and fatigue was most commonly reported to be the most bothersome sign/symptom. This contrasts with the previous literature, which identified loss of balance/coordination as the most bothersome sign/symptom that patients most wanted relief from [17]. Additionally, the research presented here identified several other signs/symptoms that have not been previously described in the literature, including loss of sensation, heaviness, hand tremors, headaches, eye problems, and breathing problems. Although these signs/symptoms were only reported by a small number of patients, their identification provides further insight into the patient experience that has not been previously explored in such depth.

Patients and neurologists reported a range of impacts associated with CIDP, most notably limitations to physical functioning (e.g., walking, risk of falling, using stairs) and ADL (e.g., showering, dressing, food preparation/consumption). Given that CIDP is associated with distal and proximal weakness of the upper and lower limbs [3], it is expected that patients experience functional limitations, and most randomized clinical trials (RCTs) over the past decade have used improvement in disability as the primary endpoint [29]. In the present study, however, other signs/symptoms were reported to contribute to these impacts, including loss of balance, loss of coordination, and fatigue. Impacts on work were also frequently mentioned across the interviews and were most commonly identified by patients as the most bothersome impact. In line with previous research [17], patients reported either being unable to work or having to work reduced hours due to their CIDP signs/symptoms. Difficulty concentrating at work and reduced work productivity were also identified. Such information regarding work absence and productivity loss is valuable for understanding treatment benefit and is increasingly being incorporated into health economic evaluations to inform decision makers, particularly in markets adopting a societal perspective to resource allocation [30]. However, in most CIDP RCTs, impacts on work only tend to be assessed as part of general HRQoL measures or in relation to fatigue [29]. CIDP was also reported to have a significant impact on patients’ psychosocial wellbeing. This included (but was not limited to) feelings of frustration and sadness at being unable to perform daily activities and work, concern about disease progression/the recurrence of symptoms, and limitations on patients’ ability to participate in social and leisure activities with others. Some patients also reported that their sense of identity had been affected by their inability to work. These findings suggest that improvements in patients’ physical functioning and in their ability to perform ADL and work may lead to better overall psychosocial wellbeing in CIDP patients. The present study also supports preliminary clinical findings that CIDP may cause mild to moderate cognitive deficits [31], with over half of patients reporting experience of brain fog and/or difficulty concentrating. Impaired sleep, including difficulty falling asleep and waking up during the night, was also reported, reflective of the previous literature [32].

This research also specifically focused on aspects of treatment experience and treatment attributes deemed important to patients in future CIDP treatments, in order to identify unmet treatment needs of patients with CIPD. Consistent with the previous literature [11–14], patients reported that their current CIDP treatments lacked effectiveness, caused unwanted side effects, and impacted their independence. With respect to treatment effectiveness, patients consistently reported that their ideal treatment would not only be effective in treating their signs/symptoms but would also provide long-term sign/symptom relief, including sustained effectiveness between doses. Some patients also noted a desire for treatments that worked to restore previous levels of functioning, rather than limiting disease progression. Related to this, patients noted a desire for treatments with minimal or reduced side effects. In this study, patients most commonly reported experience of several unwanted physiological effects (e.g., migraines/headaches, fatigue, nausea, brain fog), which they attributed to their CIDP treatments. The delivery mode required for CIDP treatments was also reported by patients to impact their independence. While this finding has been previously reported in the clinical literature [12, 13], the current study provides a more in-depth understanding of the ways that patients’ independence is affected and how delivery modes could be improved to minimize patient burden. In particular, patients noted that their medication schedule (both in terms of frequency and duration) and the need for medical staff to administer their treatment (often in a clinic setting) impacted their daily life, social functioning, and ability to participate in leisure activities, including travel. Consequently, patients described that their ideal treatment would be self-administered/administered at home, less frequent, and less time-consuming to receive.

The strengths of the research reported here include the conduct of in-depth, semi-structured, qualitative CE interviews with patients with a diagnosis of CIDP and with neurologists with experience treating patients with CIPD. CE methods used in such qualitative studies remain the gold standard for eliciting detailed patient experience data regarding the disease signs/symptoms, HRQoL impacts, and treatment burdens that matter most to patients [33]. These data have value for informing drug development and evaluation that is patient-focused, including the identification of the specific and measurable aspects of patient functioning in which change is desired, the selection of relevant outcome measures to capture important concepts, and information regarding aspects of patient preference for product design features. The conduct of telephone interviews also enabled recruitment of patients across a wide geographic area of the USA. For a rare condition like CIDP that impacts patients’ mobility, telephone interviews afforded a more accessible means of participation and may have increased response rates. In contrast to the work conducted by Allen et al. [17], in the present study we required verified documentation of CIDP diagnosis to ensure that patients included in the study had a confirmed diagnosis of CIDP, rather than a condition that exhibits similar characteristics. Saturation was also achieved, suggesting the sample size was sufficient for this qualitative study.

The findings, however, should be interpreted in the context of a number of study limitations. Despite CIDP being more common in males and prevalence increasing with age [2, 3], fewer male patients and patients older than 50 years were recruited than planned. Further, no SOC-naïve patients were recruited and only one patient with atypical CIDP (i.e., Lewis Sumner) was identified. However, this limitation likely reflects the rarity of non-typical CIDP variants. Patients and neurologists were also exclusively based in the USA, which could impact the generalizability of the findings to other countries or cultures. Additional interviews with patients and neurologists from non-US populations could therefore be of value. Finally, while no apparent differences were observed between SOC-treated and SOC-naïve patients, the results should be considered exploratory and interpreted with caution due to the small sample sizes.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to comprehensively explore the experience of CIDP from the patient and neurologist perspectives in the USA. Findings from this qualitative study supported the identification of patient-relevant signs/symptoms, functional impairment and HRQoL impacts, and unmet treatment needs, which can be used to inform CIDP drug development and evaluation. This includes identification of therapeutic targets for new therapies, selection of relevant outcome measures to assess the concepts most relevant and important to patients, and aspects regarding patient preferences for product design features.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their time and involvement in this study.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Jennifer Fine (employee of Sanofi, Paris, France) and Kate Burrows (employee of Sanofi, London, UK at the time of this research) contributed to the study conception and design. Adelphi Values was commissioned by Sanofi to conduct this research, and the sponsor funded this assistance.

Author Contributions

Anna Roberts, Natasha Griffiths, Kieran Thiara, Sophie Wallace, Nicola Williamson, and Adam Gater were involved throughout the design, data collection, and analysis of the qualitative interviews. Alyson Young contributed to the analysis of the qualitative interview data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the study results described in the manuscript and provided input into the manuscript and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Adelphi Values was commissioned by Sanofi to conduct this research, and the sponsor contributed to the study design and preparation of the manuscript for publication. The sponsor is funding the journal’s Rapid Service fee.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Anna Roberts, Natasha Griffiths, Kieran Thiara, Sophie Wallace, Alyson Young, and Adam Gater are employees of Adelphi Values, a health outcomes agency contracted by Sanofi to conduct the research. Nicola Williamson was an employee of Adelphi Values at the time the work was conducted and is now an employee of UCB Pharma GmbH. Omar Saeed is an employee of Sanofi, Reading, UK. Charles Minor is an employee of Sanofi, Cambridge, UK. Natalia Hawkin is an employee of Sanofi, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Ethical Approval

All participants provided written and oral informed consent prior to the conduct of any study activities. Ethical approval and oversight were obtained from WCGIRB, an Independent Review Board in the US (IRB tracking number: 20220058). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments and in line with guidelines related to Good Clinical Practice. All data resulting from the study were handled in accordance with US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) legislation and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for the security and privacy of health data.

Footnotes

Prior Publication: This manuscript is based on work that has previously been presented as a poster at ISPOR EU 2023, 12–15 November 2023, in Copenhagen.

References

- 1.Broers MC, Bunschoten C, Nieboer D, Lingsma HF, Jacobs BC. Incidence and prevalence of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2019;52(3–4):161–72. 10.1159/000494291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallat JM, Sommer C, Magy L. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for a treatable condition. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):402–12. 10.1016/s1474-4422(10)70041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorson KC. An update on the management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(6):359–73. 10.1177/1756285612457215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emily KM, Susanna BP, Richard ACH, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(9):973. 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Bergh PYK, van Doorn PA, Hadden RDM, et al. European academy of neurology/peripheral nerve society guideline on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: report of a joint task force—second revision. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2021;26(3):242–68. 10.1111/jns.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mork H, Motte J, Fisse AL, et al. Prevalence and determinants of pain in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: results from the German INHIBIT registry. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(7):2109–20. 10.1111/ene.15341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogia B, Rocha Cabrero F, Khan Suheb M, Rai R. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563249/. [PubMed]

- 8.Spina E, Topa A, Iodice R, Tozza S, Ruggiero L, Dubbioso R, et al. Early predictive factors of disability in CIDP. J Neurol. 2017;264(9):1939–44. 10.1007/s00415-017-8578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beydoun SR, Sharma KR, Bassam BA, Pulley MT, Shije JZ, Kafal A. Individualizing therapy in CIDP: a mini-review comparing the pharmacokinetics of Ig with SCIg and IVIg. Front Neurol. 2021;12:638816. 10.3389/fneur.2021.638816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godil J, Barrett MJ, Ensrud E, Chahin N, Karam C. Refractory CIDP: clinical characteristics, antibodies and response to alternative treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117098. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oaklander AL, Lunn MP, Hughes RA, van Schaik IN, Frost C, Chalk CH. Treatments for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP): an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1(1):cd010369. 10.1002/14651858.CD010369.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Querol L, Crabtree M, Herepath M, et al. Systematic literature review of burden of illness in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). J Neurol. 2021;268(10):3706–16. 10.1007/s00415-020-09998-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen JA, Gelinas DF, Freimer M, Runken MC, Wolfe GI. Immunoglobulin administration for the treatment of CIDP: IVIG or SCIG? J Neurol Sci. 2020;408:116497. 10.1016/j.jns.2019.116497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunschoten C, Blomkwist-Markens PH, Horemans A, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Clinical factors, diagnostic delay, and residual deficits in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2019;24(3):253–9. 10.1111/jns.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez MM, Copley-Merriman C, Arvin-Berod C, et al. Evidence gap analysis of the burden of illness and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. In: ISPOR Europe, 6–9 November 2022, Vienna.

- 16.US FDA (Food and Drug Administration). CDER patient-focused drug development. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/cder-patient-focused-drug-development. Accessed Jan 2024

- 17.Allen JA, Butler L, Levine T, Haudrich A. A global survey of disease burden in patients who carry a diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Adv Ther. 2021;38(1):316–28. 10.1007/s12325-020-01540-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez MM, Mordin M, Neighbors M, Tzivelekis S. A targeted literature review on the burden of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP). In: Virtual German Neurological Society (DGN) Congress, 4–7 November 2020; Berlin

- 19.Mendoza M, Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett-Tapia C. Symptom and treatment satisfaction in members of the US and Canadian GBS/CIDP foundations with a diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Adv Ther. 2023;40(12):5188–203. 10.1007/s12325-023-02661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Patient-focused drug development: collecting comprehensive and representative input. Guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. 2020. Accessed Jan 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/139088/download

- 21.Van den Bergh PYK, Hadden RDM, Bouche P, et al. European federation of neurological societies/peripheral nerve society guideline on management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society—first revision. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(3):356–63. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. 10.1177/1525822x05279903. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner-Bowker DM, Lamoureux RE, Stokes J, et al. Informing a priori sample size estimation in qualitative concept elicitation interview studies for clinical outcome assessment instrument development. Value Health. 2018;21(7):839–42. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks:Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelinas L, Largent EA, Cohen IG, Kornetsky S, Bierer BE, Lynch HF. A framework for ethical payment to research participants. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):766–71. 10.1056/NEJMsb1710591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Payment and reimbursement to research subjects: guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/payment-and-reimbursement-research-subjects. Accessed Jan 2024

- 27.ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. ATLAS.ti 22 [Qualitative data analysis software]. 2022. https://atlasti.com

- 28.Ogdie A, Michaud K, Nowak M, et al. Patient’s experience of psoriatic arthritis: a conceptual model based on qualitative interviews. RMD Open. 2020. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen JA, Eftimov F, Querol L. Outcome measures and biomarkers in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from research to clinical practice. Expert Rev Neurother. 2021;21(7):805–16. 10.1080/14737175.2021.1944104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Contente M, Singh P, van Dijk BCP, Dardouri M, Bey E, Francois C. Inclusion of productivity losses in HTA evaluations in function of who bears productivity losses in the real world—a qualitative assessment. In: ISPOR Europe, 2–6 November 2019, Copenhagen.

- 31.Yalachkov Y, Uhlmann V, Bergmann J, et al. Patients with chronic autoimmune demyelinating polyneuropathies exhibit cognitive deficits which might be associated with CSF evidence of blood-brain barrier disturbance. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0228679. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos PL, de Almeida-Ribeiro GAN, Silva DMD, Marques Junior W, Barreira AA. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: quality of life, sociodemographic profile and physical complaints. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients: guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-methods-identify-what-important-patients. Accessed Janu 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.