Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to analyze the clinical characteristics of oral lichenoid disease and investigate its potential association with systemic diseases.

Methods

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. The study comprised 116 patients who had been diagnosed with oral lichenoid disease, including 70 with oral lichen planus and 46 with lichenoid lesions. The study meticulously documented the distribution and types of lesions in oral lichenoid disease patients.

Results

The average age was 46 years, with females representing 69.8% and males 30.2%. The prevalence of major systemic diseases among these patients was notable: thyroid disorders were observed in 64.7%, dyslipidemia in 44.0%, hyperuricemia in 36.2%, hypertension in 28.5%, and diabetes in 21.6%. Significant associations were found between specific lesion sites and systemic diseases. Network-like lesions in the gingival-buccal groove were highly correlated with thyroid disorders (P < 0.000). Lichenoid lesions on the lips were significantly associated with dyslipidemia (P < 0.002). Furthermore, lesions on both the dorsal (P < 0.000) and ventral (P < 0.038) surfaces of the tongue, particularly patchy lesions on the dorsal surface, showed a strong association with hyperuricemia.

Conclusion

These findings indicated a significant correlation between the clinical manifestations of oral lichenoid disease and systemic conditions such as thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia.

Keywords: Oral lichenoid disease, Oral lichen planus, Lichenoid lesions, Thyroid disorders, Dyslipidemia, Hyperuricemia, Hypertension, Diabetes

Introduction

Oral lichenoid disease (OLD) encompasses a group of disorders characterized by lichen-like white changes on the oral mucosa, with or without accompanying papules, atrophy, erythema, or erosive lesions [1]. Its primary subtypes include oral lichen planus (OLP) and oral lichenoid lesions (OLL) [2]. The hallmark pathological features of these conditions are band-like lymphocytic infiltration in the lamina propria and basal cell liquefaction degeneration [3]. In this study, we used this term to describe both OLP and OLL.

OLP is a chronic immune-mediated disease of the oral mucosa mediated by T cells [4–7], with a global prevalence of approximately 1.0% [8–11]. The classic lesion of OLP is characterized by symmetrical white or grayish-white reticular patterns on the buccal mucosa [4]. Additionally, lesions may also appear on other oral sites, such as the tongue, lips, and gingiva [12]. OLP presents in six distinct clinical forms: reticular, erosive, plaque-like, atrophic, bullous, and papular, with the reticular type being the most prevalent [13]. The histopathological features of OLP include liquefaction degeneration of basal cells and a band-like infiltration of inflammatory cells at the basement membrane and superficial lamina propria [14–17]. The precise etiology of OLP remains unclear. Besides the widely recognized factors such as immune, genetic, infectious, psychological, endocrine factors, and microcirculatory disturbances [18, 19], clinical research suggests that OLP may also be associated with thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and hypertension. These conditions may potentially influence the clinical manifestations of OLP [20–25].

OLL encompass a range of conditions that exhibit clinical and pathological features very similar to those of OLP [16]. OLL can occur in various parts of the oral cavity. Unlike OLP, OLL are typically characterized by solitary or unilaterally distributed white or grayish-white patterns [16]. Histopathologically, OLL exhibit extensive inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria, often involving both superficial and deep perivascular regions. In addition to lymphocytes, the infiltrate includes eosinophils and plasma cells. Liquefaction degeneration and edema of prickle cells are observed, accompanied by apoptosis and the formation of colloid bodies. The prickle cell layer remains relatively intact, with no significant disruptions in the basal cell layer [16]. Some cases of OLL are associated with dental materials, drug reactions, graft-versus-host disease, lupus erythematosus, or paraneoplastic autoimmune multi-organ syndrome [26, 27]. However, in many cases, the etiology of OLL remains unknown. In addition, current studies have indicated a potential association between thyroid disorders and OLL [28].

Given the similar clinical presentations and histopathological features of OLP and OLL, some scholars have proposed classifying them together under the umbrella term"OLD"[1]. Current research suggests a correlation between OLD and certain systemic diseases [1], potentially affecting the clinical manifestations in OLD patients [29]. However, existing studies lack comprehensive data on critical clinical variables such as specific symptomatology and disease progression. Therefore, this study aimed to enhance the understanding of the clinical relationship between OLD and systemic diseases by analyzing the association between the clinical manifestations of OLD and various systemic conditions. Additionally, it sought to explore the potential underlying connections between OLD and these systemic diseases.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis conducted on newly diagnosed patients with OLD, based on clinical and histopathological findings, at the Department of Oral Mucosal Diseases, Tianjin Stomatological Hospital, from January 2023 to June 2023. Demographic data and clinical information, including the distribution and types of lichenoid lesions, medication usage within the past 3 months, and the presence of intraoral dental materials, were extracted from the patient's medical records. The collected demographic information included age, sex, and systemic diseases. The locations of the oral mucosal lichenoid lesions were categorized as follows: buccal mucosa, hard-palate mucosa, soft-palate mucosa, gingivobuccal mucosa, dorsum of the tongue, ventral tongue, floor of the mouth, labial mucosa, and gingiva. The types of lichenoid lesions observed were classified into reticular, erosive, plaque-like, papular, atrophic, and bullous types. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Stomatological Hospital (PH2024-Y- 015).

Diagnostic criteria for OLD

Diagnostic criteria of OLD

According to relevant literature, the clinical manifestations of OLD are characterized by lichen-like white changes on the oral mucosa, with or without accompanying papules, atrophy, erythema, or erosive lesions [1]. The primary pathological features include band-like infiltration of chronic lymphocytes in the lamina propria and liquefaction degeneration of basal cells, encompassing two major subtypes: OLP and OLL [3]. The diagnostic criteria for OLD in this study were based on the established diagnostic standards for OLP and OLL.

The final diagnosis of OLP in this study was determined according to the 2022 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus issued by the Chinese Stomatological Association [14]. Cases meeting both clinical and histopathological criteria were diagnosed as OLP, while those with atypical presentations in either aspect were classified as OLL [16]. Furthermore, all histopathological diagnoses of OLD required the exclusion of epithelial dysplasia.

Clinical diagnostic criteria for OLP

The clinical diagnostic criteria for OLP included multiple or bilaterally distributed white or grayish-white striations or reticulations on the oral mucosa that were slightly raised above the mucosal surface. It might also present as erosive, plaque-like, atrophic, vesicular, or papular lesions; however, these latter five lesion types must coexist with reticular lesions in other areas of the oral cavity to confirm the diagnosis [14].

Clinical diagnostic criteria for OLL

The clinical diagnostic criteria for OLL included solitary or unilaterally distributed white or grayish-white striations or reticulations on the oral mucosa, slightly raised above the mucosal surface. OLL might also present as single or multiple lesions, irrespective of bilateral distribution, but were associated with recognized etiological factors such as suspected dental materials, medications, graft-versus-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, or paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome [14–16, 22].

Histopathological diagnostic criteria for OLP

The histopathological diagnostic criteria for OLP included hyperkeratosis of the epithelium with acanthosis or atrophy, irregular elongation of epithelial rete ridges forming a saw-tooth pattern, and lymphocytic infiltration in the deeper layers of the squamous epithelium. Additional features involved liquefaction degeneration of basal cells and a band-like or focal infiltration of lymphocytes in the superficial lamina propria, with a clear demarcation. Notably, the criteria also required the absence of epithelial dysplasia and verrucous epithelial hyperplasia [14].

Histopathological diagnostic criteria for OLL

The histopathological diagnostic criteria for OLL included mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria, comprising lymphocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells, often extending to both superficial and deep perivascular regions. Additional features included liquefaction degeneration and edema of prickle cells, accompanied by apoptosis and colloid body formation, while the prickle cell layer remained relatively intact, with no significant disruption of the basal cell layer [16].

Classification criteria for OLD lesions

The classification of OLD lesions in this study was based on the subtypes OLP and OLL. The classification criteria for OLP lesions followed the Andreasen classification system and the 2022 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus issued by the Chinese Stomatological Association [12–14]. Given the clinical similarities between OLL and OLP lesions, the classification of OLL in this study referenced the OLP classification system. The clinical presentations of each lesion type were as follows:

Reticular type: Reticular lesions present as grayish-white patterns slightly raised above the mucosal surface, forming a net-like appearance. In this study, reticular lesions were described as white, net-like patterns confined to the affected area.

Erosive type: Erosive lesions appear as irregular erosions covered with a yellow pseudomembrane, with congested and reddened margins often accompanied by erythematous patches and reticular white lesions. In this study, erosive lesions were described as areas of erosion covered with a yellow pseudomembrane, with reddened and congested margins. Surrounding areas may or may not exhibit reticular or atrophic lesions.

Plaque-like type: Plaque-like lesions vary in size, typically occurring on the dorsal tongue, appearing as irregularly shaped white plaques with a slightly concave and smooth surface. In this study, plaque-like lesions were described as irregularly shaped white plaques of varying sizes, slightly concave with a smooth surface. Surrounding areas may or may not feature reticular lesions.

Atrophic type: Atrophic lesions are characterized by epithelial thinning and atrophy, often accompanied by congested red patches and erosions, typically surrounding reticular patterns. In this study, atrophic lesions were described as areas of epithelial thinning and atrophy with congested red patches. Surrounding areas may or may not include reticular lesions.

Bullous type: Bullous lesions arise from the separation of the epithelium and underlying connective tissue, forming transparent or translucent bullae often associated with reticular or plaque-like lesions. After rupturing, these bullae leave erosive surfaces. In this study, bullous lesions were described as transparent or translucent bullae surrounded by reticular or plaque-like lesions.

Papular type: Papular lesions present as grayish-white papular spots, slightly elevated, and are often surrounded by white striations. In this study, papular lesions were described as slightly elevated white papular spots. Surrounding areas may or may not exhibit reticular lesions.

Diagnostic criteria for systemic diseases

The diagnostic information for thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperuricemia in patients was obtained from thyroid ultrasound, thyroid function tests (TSH, FT3, FT4), thyroid antibodies (TPOAb, TGAb), fasting liver and renal function tests, fasting blood glucose levels, blood pressure measurements, and other relevant reports. These were combined with specialized examination results provided by the patients.

Diagnostic Criteria for Thyroid Disorders (based on the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Thyroid Diseases [30]): Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: Positive for thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) and thyroglobulin antibody (TGAb), with or without localized or systemic manifestations. Hypothyroidism: Elevated TSH levels with reduced total thyroxine (TT4) and free thyroxine (FT4) levels. Hyperthyroidism: Reduced TSH levels with elevated TT4, FT4, total triiodothyronine (TT3), and free triiodothyronine (FT3) levels, with or without clinical signs and symptoms of hypermetabolism. Thyroid nodules: One or more nodules detected on thyroid ultrasound.

Diagnostic Criteria for Dyslipidemia [31]: total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 6.2 mmol/L; triglycerides (TG) ≥ 2.3 mmol/L; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 4.1 mmol/L; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 1.0 mmol/L in men or < 1.3 mmol/L in women.

Diagnostic Criteria for Diabetes [32]: fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/L. Diagnostic Criteria for Hypertension [33]: average systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg.

Diagnostic Criteria for Hyperuricemia [34]: serum uric acid (UA) ≥ 420 μmol/L in men or ≥ 360 μmol/L in women.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients must be 18 years of age or older and have a confirmed diagnosis of OLP or OLL based on histopathological examination.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) a clinical or histopathological diagnosis inconsistent with OLD (OLP/OLL); (2) incomplete records of intraoral lesion sites, lesion types, recent medication history (within the past 3 months), or intraoral dental materials; (3) missing reports on thyroid ultrasound, thyroid function tests (TSH, FT3, FT4), thyroid antibodies (TPOAb, TGAb), fasting liver and renal function, fasting blood glucose levels, or blood pressure measurements; (4) were pregnant or lactating; or (5) had complex systemic diseases. To be included in the study, patients must meet all the inclusion criteria. Any patient who met even one of the exclusion criteria was excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

Data collected for this study were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software and Graph Pad Prism8.0. The relationship between clinical manifestations of OLD and systemic diseases was examined through independent samples t-tests, chi-square tests, and univariate logistic regression analyses. Statistical significance was determined at a threshold of P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic information of patients with OLD

A total of 116 patients with OLD were included in the study. Among them, 70 patients were diagnosed with OLP based on histopathological examination (60.3%), while the remaining 46 patients were diagnosed with OLL (39.7%). The patients'ages ranged from 23 to 72 years, with an average age of 46 years. Independent samples t-tests indicated a significant difference in the age of onset between OLP and OLL, with OLP having an earlier onset (P < 0.001). Among the OLD patients, 81 (69.8%) were female and 35 (30.2%) were male. There was no significant difference in gender distribution between OLP and OLL, with both groups predominantly female (P = 0.427).

Medical history surveys revealed that 98.3% of the OLD patients in the study had at least one of the following systemic diseases: thyroid disorders (64.7%), dyslipidemia (44.0%), hyperuricemia (36.2%), hypertension (28.5%), or diabetes (21.6%). Additionally, some patients had other conditions such as rhinitis (n = 2), arteriosclerosis (n = 2), fatty liver (n = 2), breast nodules (n = 2), or gallstones (n = 1), but these were less common and thus excluded from the main analysis. Chi-square tests indicated no significant difference in the prevalence of systemic diseases between patients with OLP and those with OLL (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of OLD patients

| Data | OLD | OLP | OLL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 116 | 70 (60.3%) | 46 (39.7%) | - |

| Age | 46.8 | 43.4 | 51.98 | < 0.001 |

| Gender (Female/Male) | 81/35 (69.8%/30.2%) | 47/23 (67.1%/32.9%) | 34/12 (73.9%/26.1%) | 0.427 |

| Medication Usage within the Past 3 Months | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Intraoral Dental Materials | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Thyroid Disease | 75 (64.7%) | 41 (58.6%) | 34 (73.9%) | 0.091 |

| Dyslipidemia | 51 (44.0%) | 28 (40.0%) | 23 (50.0%) | 0.288 |

| Diabetes | 25 (21.6%) | 11 (15.7%) | 14 (30.4%) | 0.059 |

| Hypertension | 33 (28.5%) | 20 (28.6%) | 13 (28.3%) | 0.971 |

| Hyperuricemia | 42 (36.2%) | 30 (42.9%) | 12 (26.1%) | 0.066 |

| Rhinitis | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 | - |

| Atherosclerosis | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | - |

| Fatty Liver | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 | - |

| Breast Nodules | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 | - |

| Gallstones | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | - |

Clinical characteristics of patients with OLD

Distribution of clinical lesions in patients with OLD

The most commonly affected areas of oral mucosa in patients with OLD were the buccal mucosa (68.1%), gingival-buccal groove (59.5%), dorsal surface of the tongue (36.2%), and ventral surface of the tongue (25.9%). Less frequently affected areas included the labial mucosa (14.7%) and gingiva (6.9%). Additionally, the lichenoid lesions in the oral mucosa of the OLD patients in this study did not involve the hard palate, soft palate, or floor of the mouth. Chi-square tests indicated no significant difference in lesion distribution between OLP and OLL (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of oral mucosal lesions in OLD patients

| Data | OLD | OLP | OLL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal Mucosa | 79 (68.1%) | 52 (74.3%) | 27 (58.7%) | 0.078 |

| Gingival Buccal Sulcus | 69 (59.5%) | 41 (58.6%) | 28 (60.9%) | 0.424 |

| Dorsal Tongue | 42 (36.2%) | 27 (38.6%) | 15 (32.6%) | 0.513 |

| Ventral Tongue | 30 (25.9%) | 18 (25.7%) | 12 (26.1%) | 0.964 |

| Lip Mucosa | 17 (14.7%) | 11 (15.7%) | 6 (13.0%) | 0.691 |

| Gingiva | 8 (6.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.32 |

| Hard-palate Mucosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Soft-palate Mucosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Floor of Mouth Mucosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

Types of oral mucosal lesions in various locations for patients with OLD

We analyzed the types of lesions in various oral locations. The predominant lesion morphology in OLD was the reticular type, followed by the erosive and plaque-like types, with atrophic and papular types being less common. No bullous-type lesions were observed among the OLD patients in this study. Different types of lesions tended to occur in specific areas. For example, reticular lesions were most common in the buccal area and gingival-buccal groove; erosive lesions were primarily found in the buccal area; plaque-like type lesions predominantly occurred on the dorsal surface of the tongue; atrophic lesions were seen in the gingival-buccal groove and dorsal surface of the tongue; and papular lesions were observed in the buccal area. Additionally, we found that different locations had varying predominant lesion types, with reticular lesions being the most common overall, while lesions on the dorsal surface of the tongue were primarily plaque-like types (71.4%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Types of oral mucosal lesions in OLD patients

| Reticular Type | Erosive Type | Plaque-like Type | Atrophic Type | Papular Type | Bullous Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal Mucosa | 55 (47.4%) | 19 (16.4%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 4 (3.5%) | 0 |

| Gingival Buccal Sulcus | 59 (50.9%) | 6 (5.2%) | 0 | 4 (3.5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Dorsal Tongue | 7 (6.0%) | 4 (3.5%) | 30 (71.4%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| Ventral Tongue | 22 (19.0%) | 7 (6.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lip Mucosa | 15 (12.9%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gingiva | 7 (6.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Clinical manifestations of OLD and systemic diseases

Distribution of oral lesions in OLD patients and systemic diseases

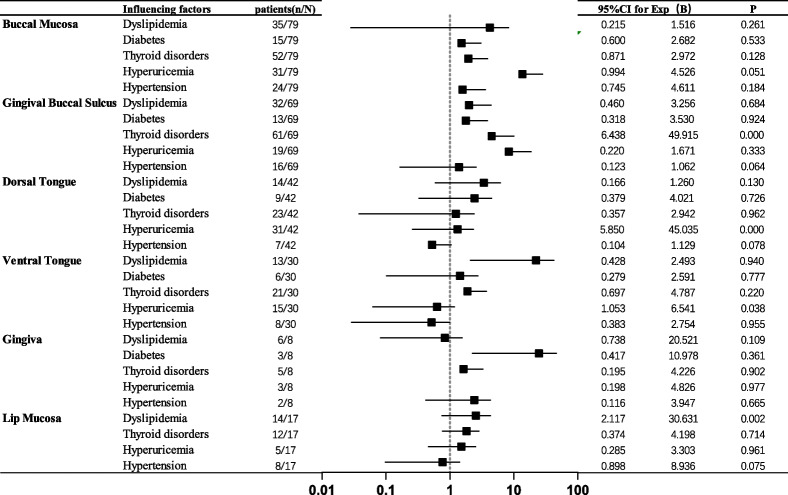

Regarding the relationship between the locations of OLD and systemic diseases in OLD patients, univariate logistic regression analysis revealed the following associations: lesions in the gingival-buccal groove were significantly associated with thyroid disorders (P < 0.000); lesions on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue were significantly related to hyperuricemia (P < 0.000); and lesions on the labial mucosa were associated with dyslipidemia (P = 0.017). However, no significant associations were found between lesions in the buccal area, gingiva, and systemic conditions such as dyslipidemia, diabetes, thyroid disorders, or hyperuricemia (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of systemic diseases and oral lesion distribution in OLD patients

Morphology of oral lesions at specific sites in OLD patients and systemic diseases

Chi-square tests revealed that OLD patients with thyroid disorders were significantly associated with reticular lesions in the gingival-buccal groove (P = 0.007). Additionally, OLD patients with hyperuricemia were highly associated with plaque-like type lesions on the dorsal surface of the tongue (P < 0.000). The relationship between hyperuricemia in OLD patients and the lesion morphology on the ventral surface of the tongue is not significant; similarly, there is no significant difference in the various lesion morphologies on the labial mucosa in OLD patients with dyslipidemia (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Chi-square test of systemic diseases and specific oral lesion sites in OLD patients

| Disease | Reticular Type | Erosive Type | Patch Type | Atrophic Type | Papular-like Type | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gingival Buccal Sulcus | Thyroid Disease | 55/69 | 4/69 | 0 | 2/69 | 0.007 |

| Non-Thyroid Disease | 4/69 | 2/69 | 0 | 2/69 | ||

| Dorsal Tongue | Hyperuricemia | 1/42 | 4/42 | 14/42 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Non-Hyperuricemia | 6/42 | 0 | 4/42 | 1/42 | ||

| Ventral Tongue | Hyperuricemia | 13/30 | 2/30 | 0 | 0 | 0.179 |

| Non-Hyperuricemia | 10/30 | 5/30 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lip Mucosa | Dyslipidemia | 13/17 | 1/17 | 0 | 0 | 0.331 |

| Non-Dyslipidemia | 2/17 | 1/17 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Current research indicates that OLD is associated with various systemic diseases, which may potentially influence its clinical manifestations [12, 29]. In this study, we summarized the potential statistical associations between the clinical features of OLD and systemic conditions such as thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia. These findings might facilitate further investigation into the relationship between OLD and systemic diseases.

OLD predominantly affects middle-aged and elderly women [11], and compared to OLP, OLL generally impacts older patients [35, 36]. Our results aligned with current research. The prevalence of thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, hypertension, and diabetes among OLD patients in this study was significantly higher than the rates reported in the general population [20–25, 37–40]. No significant difference was found in the prevalence of systemic diseases between OLP and OLL patients. The statistical associations between OLP and systemic diseases such as thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes have been widely reported [37, 39, 40], with thyroid disorders being the most common. The evidence for the connection between OLP and these conditions is largely indirect, involving shared pathogenic factors and chronic inflammatory processes, with the exact mechanisms remaining unclear.

To date, the relationship between OLP and hyperuricemia remains poorly understood [41]. In our present study, we found that approximately 42.9% of OLP patients presented with hyperuricemia, a prevalence notably higher than that observed in the general population [42]. This observation suggested that hyperuricemia might serve as a potential risk factor for OLP. Furthermore, research on the associations between OLL and systemic diseases such as thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, hypertension, and diabetes is still limited, necessitating further case–control studies to evaluate these associations.

OLD is an inflammatory disease of the oral mucosa characterized primarily by white striae on the mucosal surface [1]. In this study, we found that lesions in certain areas of the oral mucosa in OLD patients might be associated with systemic diseases. Specifically, lesions in the gingival-buccal groove might be related to thyroid disorders, typically presenting as reticular lesions in this area. OLD patients with hyperuricemia frequently exhibited lichenoid lesions on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue, particularly plaque-like lesions on the dorsal tongue. Additionally, lichenoid lesions on the labial mucosa in OLD patients might be associated with dyslipidemia.

In current research on thyroid disorders related to OLP, scholars widely recognize the association between OLP and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, suggesting a possible shared genetic background [43–45], common pathogenic factors, and autoimmune pathways [46–48]. It is hypothesized that Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may increase susceptibility to OLP, potentially due to thyroid autoantibodies that may trigger local immune responses in the oral mucosa, inducing apoptosis of keratinocytes [49, 50]. However, existing studies do not fully explain the relationship between OLP and thyroid disorders. In this clinical study, we discussed, for the first time, the association between the clinical features of OLD and the prevalence of thyroid disorders. Further research is needed to explain why OLD patients with thyroid disorders are prone to reticular lesions in the gingival-buccal groove.

UA is the end product of purine metabolism, and hyperuricemia is a chronic metabolic disorder resulting from disturbances in purine metabolism [51]. The prevalence of hyperuricemia is relatively high among patients with lichen planus (LP) [46]. Some researchers speculate that this phenomenon may be due to the stimulation of keratinocytes by urate crystals, which produce inflammatory cytokines [52]. Urate crystals in the serum can induce the production of TH17 cells, IL- 17, and other related inflammatory cells and cytokines [53]. Additionally, purinergic receptors are present on keratinocytes, and urate crystals can increase the expression of these receptors, further stimulating the production of inflammatory cells [54–57]. Therefore, we hypothesized that OLD patients with hyperuricemia might share a similar pathogenic mechanism with LP. However, this hypothesis requires further research and experimental validation to confirm.

In response to the observation of specific lesions in certain oral sites in OLD patients with thyroid disorders or hyperuricemia, we initiated research on the relationship between OLD and these conditions. Preliminary results would be reported in due course.

Dyslipidemia is characterized by elevated levels of TC, TG, and LDL-C, alongside reduced HDL-C levels, and is associated with chronic inflammation [58, 59]. OLD, a chronic inflammatory disease, manifests as white striae on the oral mucosa. Previous case–control studies have shown that dyslipidemia is common among patients with OLP [60]. Consequently, some researchers suggest that chronic inflammation may link dyslipidemia to the pathogenesis of OLP [61]. Although the association between OLD and dyslipidemia has not been thoroughly investigated, our observation that some OLD patients with dyslipidemia tended to develop lesions on the labial mucosa further supported the potential role of dyslipidemia in OLD. Research in this area may provide deeper insights into the relationship between these two conditions.

In summary, our study reaffirmed that OLD might be associated with systemic diseases such as thyroid disorders, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, diabetes, and hypertension. The lesions observed in the gingival-buccal groove, dorsal tongue, ventral tongue, and labial mucosa of OLD patients might hold significant clinical implications, often suggesting the presence of concurrent systemic conditions. This finding could prompt clinicians to pay closer attention to the systemic diseases associated with OLD patients. Given the limitations of our study, including a relatively small sample size and certain methodological constraints, further research with larger cohorts and longitudinal study designs is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of systemic diseases on OLD. Furthermore, it is not yet known whether treatment of systemic diseases affects lesions in OLD. We warmly welcome scholars from diverse regions to collaborate and contribute to this field of research. Additionally, our study suggested that differentiating subtypes based on lesion characteristics in OLD patients might aid in identifying associations with systemic diseases. This approach could potentially standardize subtype research and further explore the etiology and pathogenesis of OLD.

The patients included in this study were predominantly from North China, including Tianjin and the three northeastern provinces, reflecting the specific research context of the Tianjin Stomatological Hospital. We sincerely invite researchers worldwide to join us in expanding the study's sample size and collaboratively exploring the etiology and mechanisms of OLD in greater depth.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- OLD

Oral lichenoid disease

- OLP

Oral lichen planus

- OLL

Oral lichenoid lesions

- TPOAb

Thyroid peroxidase antibody

- TGAb

Thyroglobulin antibody

- TT4

Total thyroxine

- FT4

Free thyroxine

- TT3

Total triiodothyronine

- FT3

Free triiodothyronine

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglycerides

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- UA

Uric acid

- LP

Lichen planus

Authors’ contributions

WP: Data collection,data categorization, data analysis, manuscript writing. YP: Data collection, data categorization, data analysis, manuscript writing. ZY: Data categorization. LY: Data collection. DF: Data collection. ZM: Data collection. WR: Data collection. YY: Critical review of the manuscript's intellectual content and research guidance. ZH: Critical review of the manuscript's intellectual content and research guidance. CR: Critical review of the manuscript's intellectual content, research guidance, and writing support. LCL: Critical review of the manuscript's intellectual content, research guidance, and writing support.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Key Laboratory of Oral Function Reconstruction Fund of Tianjin (Grant No. 2023KLQN07 and Grant No. 2023KLMS03), the Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology (Grant No. 2018056), the Medical Talent Project of Tianjin City (TJSJMYXYC-D2-032), and the Tianjin Stomatological Hospital Ph.D. and Master's Key Project (Grant No. 2019BSZD05).

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request. Email:wangpeilin1001@163.com.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Stomatological Hospital (PH2024-Y- 015). For this type of study, the need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Stomatological Hospital.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peilin Wang and Peipei Yan contributed equally to this work and shared the first authorship.

References

- 1.Aguirre-Urizar JM, Alberdi-Navarro J, de Mendoza ILI, Marichalar-Mendia X, Martínez-Revilla B, Parra-Pérez C, Echebarria-Goicouria MÁ. Clinicopathological and prognostic characterization of oral lichenoid disease and its main subtypes: a series of 384 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:e554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin I, Laronde DM, Zhang L, Rosin MP, Yim I, Rock LD. Basement membrane degeneration is common in lichenoid mucositis with dysplasia. Can J Dent Hyg. 2021;55:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberdi-Navarro J, Marichalar-Mendia X, Lartitegui-Sebastián MJ, Gainza-Cirauqui ML, Echebarria-Goikouria MA, Aguirre-Urizar JM. Histopathological characterization of the oral lichenoid disease subtypes and the relation with the clinical data. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22:e307–13. 10.4317/medoral.21730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.陈谦明, 曾昕. 案析口腔黏膜病学[M]. 2 版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2019: 87–90 CHEN Qianming, ZENG Xin. Case-based oral medicine[M]. 2nd ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2019: 87–90. (in Chinese).

- 5.Wang Y, Du G, Shi L, Shen X, Shen Z, Liu W. Altered expression of CCN1 in oral lichen planus associated with keratinocyte activation and IL-1β, ICAM1, and CCL5 up-regulation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020;49(9):920–5. 10.1111/jop.13087. (Epub 2020 Aug 14). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Jiang Y, Wang H, Luo Z, Wang Y, Guan X. IL-25 promotes Th2-type reactions and correlates with disease severity in the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;98:115–21. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.11.015. (Epub 2018 Nov 17). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Guan X, Luo Z, Liu Y, Ren Q, Zhao X. The association and potentially destructive role of Th9/IL-9 is synergistic with Th17 cells by elevating MMP9 production in local lesions of oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(4):425–33. 10.1111/jop.12690. (Epub 2018 Mar 6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng J, Zhou Z, Shen X, Wang Y, Shi L, Wang Y, Hu Y, Sun H, Liu W. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai. China J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(7):490–4. 10.1111/jop.12264. (Epub 2014 Sep 22). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Lenouvel D, Ruiz-Ávila I, Ramos-García P. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021;27(4):813–28. 10.1111/odi.13323. (Epub 2020 Apr 2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick SG, Honda KS, Sattar A, Hirsch SA. Histologic Lichenoid Features in Oral Dysplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:511–20. 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.12.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlosser BJ. Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:251–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldmeyer L, Suter VG, Oeschger C, Cazzaniga S, Bornstein MM, Simon D, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions - an analysis of clinical and histopathological features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rock L, Laronde D, Lin I, Rosin M, Chan B, Shariati B, Zhang L. dysplasia should not be ignored in lichenoid mucositis. J Dent Res. 2018;97:767–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Society of Oral Medicine; Chinese Stomatological Association. [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of oral lichen planus (revision)]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;57(2):115–121. Chinese. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20211115-00505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.van der Meij EH, Schepman KP, van der Waal I. The possible premalignant character of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96(2):164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Meij EH, van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507–12. 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng YS, Gould A, Kurago Z, Fantasia J, Muller S. Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: a position paper of the American academy of oral and maxillofacial pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(3):332–54. 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng X, Wang Y, Jiang L, Li J, Chen Q. Updates on immunological mechanistic insights and targeting of the oral lichen planus microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;9(13):1023213. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1023213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alrashdan MS, Cirillo N, McCullough M. Oral lichen planus: a literature review and update. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:539–51. 10.1007/s00403-016-1667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dave A, Shariff J, Philipone E. Association between oral lichen planus and systemic conditions and medications: case-control study. Oral Dis. 2021;27(3):515–24. 10.1111/odi.13572. (Epub 2020 Aug 20). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piloni S, Ferragina F, Barca I, Kallaverja E, Cristofaro MG. The correlation between oral lichen planus and thyroid pathologies: a retrospective study in a sample of italian population. Eur J Dent. 2024;18(2):510–6. 10.1055/s-0043-1772247. (Epub 2023 Sep 20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wongpakorn P, Chantarangsu S, Prapinjumrune C. Factors involved in the remission of oral lichen planus treated with topical corticosteroids. BDJ Open. 2024;10(1):34. 10.1038/s41405-024-00217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Han X, Zhu L, Shen Z, Liu W. Possible interplay of diabetes mellitus and thyroid diseases in oral lichen planus: a pooled prevalence analysis. J Dent Sci. 2024;19(1):626–30. 10.1016/j.jds.2023.11.004. (Epub 2023 Nov 20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Chen D, Deng X, Xu Y, Wang Y, Qiu X, Yuan P, Zhang Z, Xu H, Jiang L. Prevalence of oral lichen planus in patients with diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2024;30(2):528–36. 10.1111/odi.14323. (Epub 2022 Aug 16). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Porras-Carrique T, Ramos-García P, González-Moles MÁ. Hypertension in oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2023. 10.1111/odi.14727. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lu R, Zhou G. Oral lichenoid lesions: Is it a single disease or a group of diseases? Oral Oncol. 2021;117:105188. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105188. (Epub 2021 Feb 6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller S. Oral lichenoid lesions: distinguishing the benign from the deadly. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:S54–67. 10.1038/modpathol.2016.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Zhou R, Tan P, Cheng B, Ma L, Wu T. Oral lichenoid lesion simultaneously associated with Castleman’s disease and papillary thyroid carcinoma: a rare case report. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):572. 10.1186/s12903-022-02623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alsoghier A, AlMadan N, Alali M, Alshagroud R. Clinicohistological characteristics of patients with oral lichenoid mucositis: a retrospective study for dental hospital records. J Clin Med. 2023;12(19):6383. 10.3390/jcm12196383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinese Society of Endocrinology A guide to the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid diseases in China-laboratory and auxiliary examinations for thyroid diseases (in chinese). Chin J Intern Med. 2007;46:697–702. 10.3760/j.issn:0578-1426.2007.08.038.

- 31.Wu L, Parhofer KG. Diabetic dyslipidemia. Metabolism. 2014;63:1469–79. 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and Classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33((Suppl. S1)):S62–S69. 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lewington S, Clarke R, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Peto R, Collins R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borghi C, Domienik-Karłowicz J, Tykarski A, Widecka K, Filipiak KJ, Jaguszewski MJ, Narkiewicz K, Mancia G. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patient with hyperuricemia and high cardiovascular risk: 2021 update. Cardiol J. 2021;28:1–14. 10.5603/CJ.a2021.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mravak-Stipetic M, Loncar-Brzak B, Bakale-Hodak I, Sabol I, Seiwerth S, Majstorovic M, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a preliminary study. Sci World J. 2014;2014:746874–746874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Netto JNS, Pires FR, Costa KHA, Fischer RG. Clinical features of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: an oral pathologist’s perspective. Braz Dent J. 2022;33(3):67–73. 10.1590/0103-6440202204426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou T, Li D, Chen Q, Hua H, Li C. Correlation between oral lichen planus and thyroid disease in China: a case-control study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;18(9):330. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M, Zhu X, Wu J, Huang Z, Zhao Z, Zhang X, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia among Chinese adults: findings from two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in 2015–16 and 2018–19. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 791983. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.791983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ilves L, Ottas A, Raam L, Zilmer M, Traks T, Jaks V, Kingo K. Changes in lipoprotein particles in the blood serum of patients with lichen planus. Metabolites. 2023;13(1):91. 10.3390/metabo13010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selaru CA, Parlatescu I, Milanesi E, Dobre M, Tovaru S. Impact of altered lipid profile in oral lichen planus. Maedica (Bucur). 2023;18(1):12–8. 10.26574/maedica.2023.18.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakhtiari S, Toosi P, Samadi S, Bakhshi M. Assessment of uric acid level in the saliva of patients with oral lichen planus. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(1):57–60. 10.1159/000452133. (Epub 2016 Sep 29). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, Mohan RP, Gupta S, Malik SS, Goel S, Kamarthi N. Roles of serum uric acid, prolactin levels, and psychosocial factors in oral lichen planus. J Oral Sci. 2017;59(1):139–46. 10.2334/josnusd.16-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geng L, Zhang X, Tang Y, Gu W. Identification of potential key biomarkers and immune infiltration in oral lichen planus. Dis Markers. 2022;26(2022):7386895. 10.1155/2022/7386895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawkins BR, Lam KS, Ma JT, Wang C, Yeung RT. Strong association between HLA DRw9 and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in southern Chinese. Acta Endocrinol. 1987;114:543–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin SC, Sun A. HLA-DR and DQ antigens in Chinese patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:298–300. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomer Y, Davies TF. Searching for the autoimmune thyroid disease susceptibility genes: from gene mapping to gene function. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(5):694–717. 10.1210/er.2002-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jontell M, Ståhlblad PÅ, Rosdahl I, Lindblom B. HLA-DR3 antigens in erosive oral lichen planus, cutaneous lichen planus, and lichenoid reactions. Acta Odontol Scand. 1987;45(5):309–12. 10.3109/00016358709096352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu P, Luo S, Zhou T, Wang R, Qiu X, Yuan P, Yang Y, Han Q, Jiang L. Possible mechanisms involved in the cooccurrence of oral lichen planus and hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;4(2020):6309238. 10.1155/2020/6309238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Kohn L, et al. Expression of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis related genes in the human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119(6):1449–55. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muzio LL, Santarelli A, Campisi G, Lacaita M, Favia G. Possible link between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and orallichen planus: a novel association found. Clin Oral Invest. 2013;17(1):333–6. 10.1007/s00784-012-0767-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El Ridi R, Tallima H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: a review. J Adv Res. 2017;8(5):487–93. 10.1016/j.jare.2017.03.003. (Epub 2017 Mar 14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oguz U, Takci Z, Oguz ID, Resorlu B, Balta I, Unsal A. Are patients with lichen planus really prone to urolithiasis? Lichen planus and urolithiasis. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42(3):571–7. 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klück V, Liu R, Joosten LAB. The role of interleukin-1 family members in hyperuricemia and gout. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88: 105092. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.105092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raucci F, Iqbal AJ, Saviano A, Minosi P, Piccolo M, Irace C, et al. IL-17A neutralizing antibody regulates monosodium urate crystal-induced gouty inflammation. Pharmacol Res. 2019;147: 104351. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ondet T, Muscatelli-Groux B, Coulouarn C, Robert S, Gicquel T, Bodin A, et al. The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines is mediated via mitogen-activated protein kinases rather than by the inflammasome signalling pathway in keratinocytes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:827–38. 10.1111/1440-1681.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uratsuji H, Tada Y, Hau CS, Shibata S, Kamata M, Kawashima T, et al. Monosodium urate crystals induce functional expression of P2Y14 receptor in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1293–6. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uratsuji H, Tada Y, Kawashima T, Kamata M, Hau CS, Asano Y, et al. P2Y6 receptor signaling pathway mediates inflammatory responses induced by monosodium urate crystals. J Immunol. 2012;188:436–44. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kopin L, Lowenstein C. Dyslipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):ITC81–96. 10.7326/AITC201712050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Esteve E, Ricart W, Fernández-Real JM. Dyslipidemia and inflammation: an evolutionary conserved mechanism. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(1):16–31. 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozbagcivan O, Akarsu S, Semiz F, Fetil E. Comparison of serum lipid parameters between patients with classic cutaneous lichen planus and oral lichen planus. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(2):719–25. 10.1007/s00784-019-02961-6. (Epub 2019 May 25). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao X, Song Z, Liu S. Potential implication of serum lipid levels as predictive indicators for monitoring oral lichen planus. J Dent Sci. 2024;19(2):1307–11. 10.1016/j.jds.2023.12.026. (Epub 2024 Jan 24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request. Email:wangpeilin1001@163.com.